Land Use Change and Biocultural Heritage in Valle Nacional, Oaxaca: Women’s Contributions and Community Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Feminist Political Ecology and Territorial Governance

2.2. Indigenous Epistemologies and Biocultural Memory

2.3. Biocultural Resilience and Adaptive Socio-Ecological Systems

2.4. Biocultural Heritage as a Tool for Territorial Continuity and Cultural Resistance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Site Location

3.2. Methodological Approach and Data Collection

4. Results

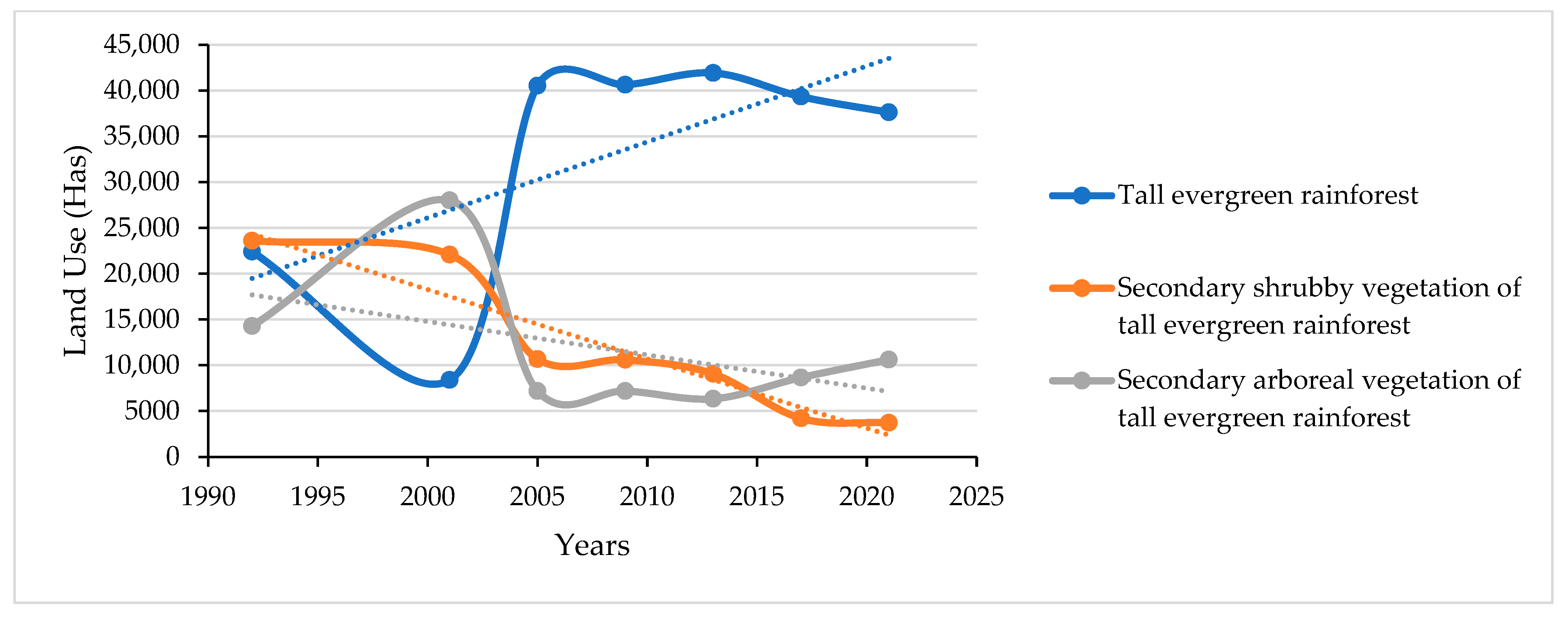

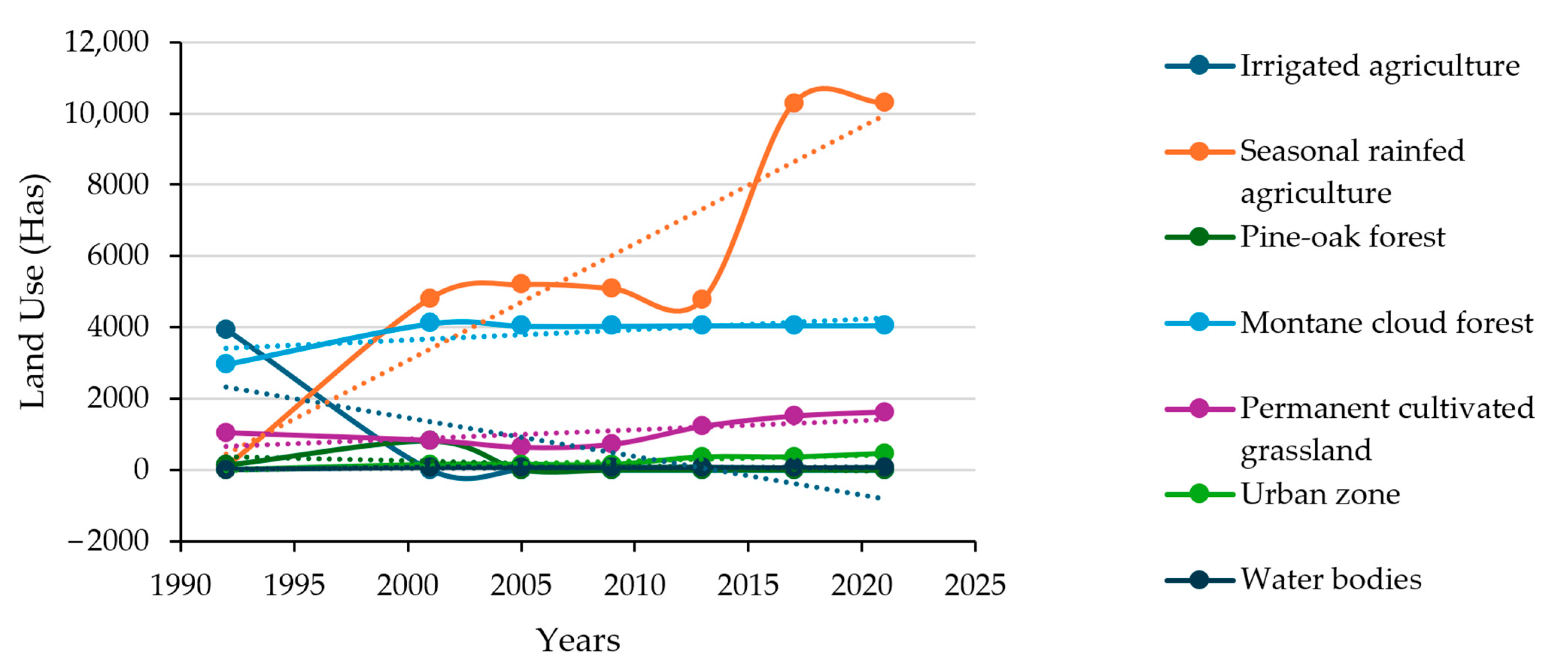

4.1. Land Use Transitions and Vegetation Cover Change (1992–2021)

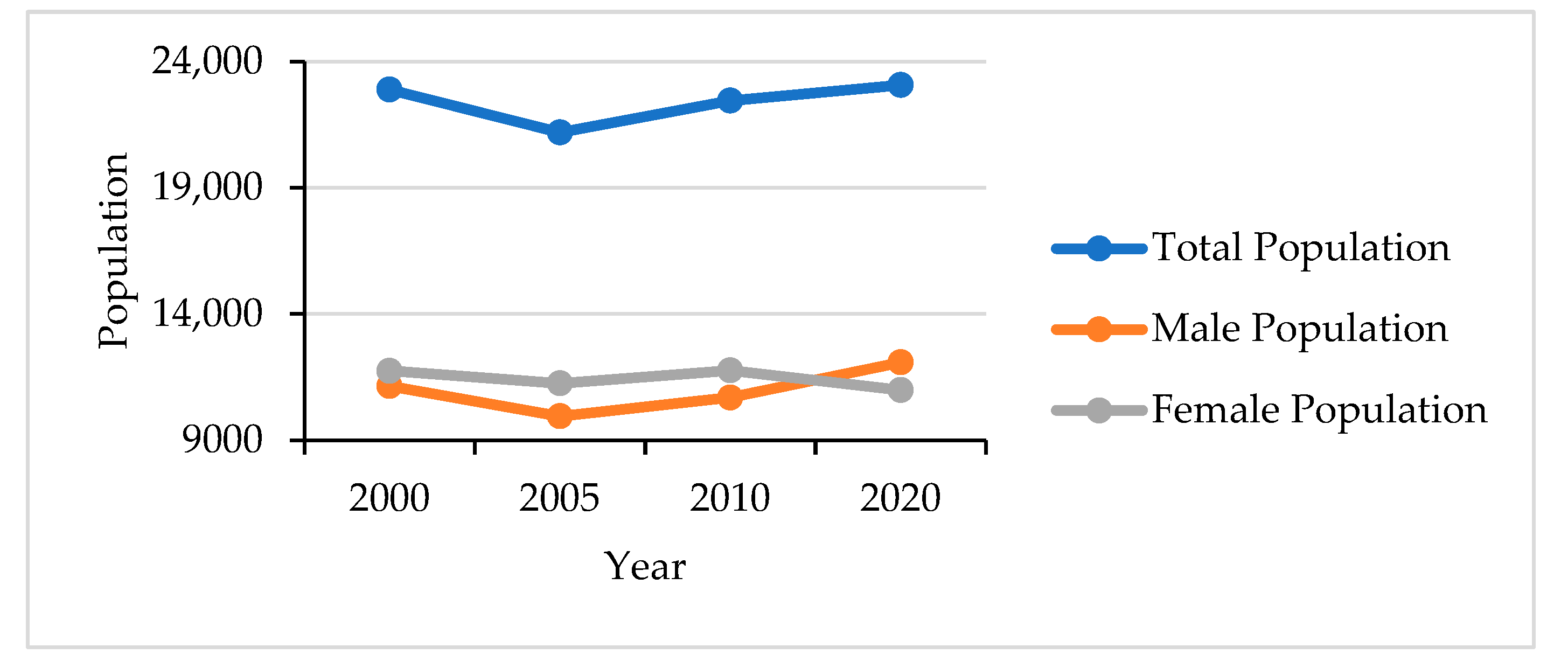

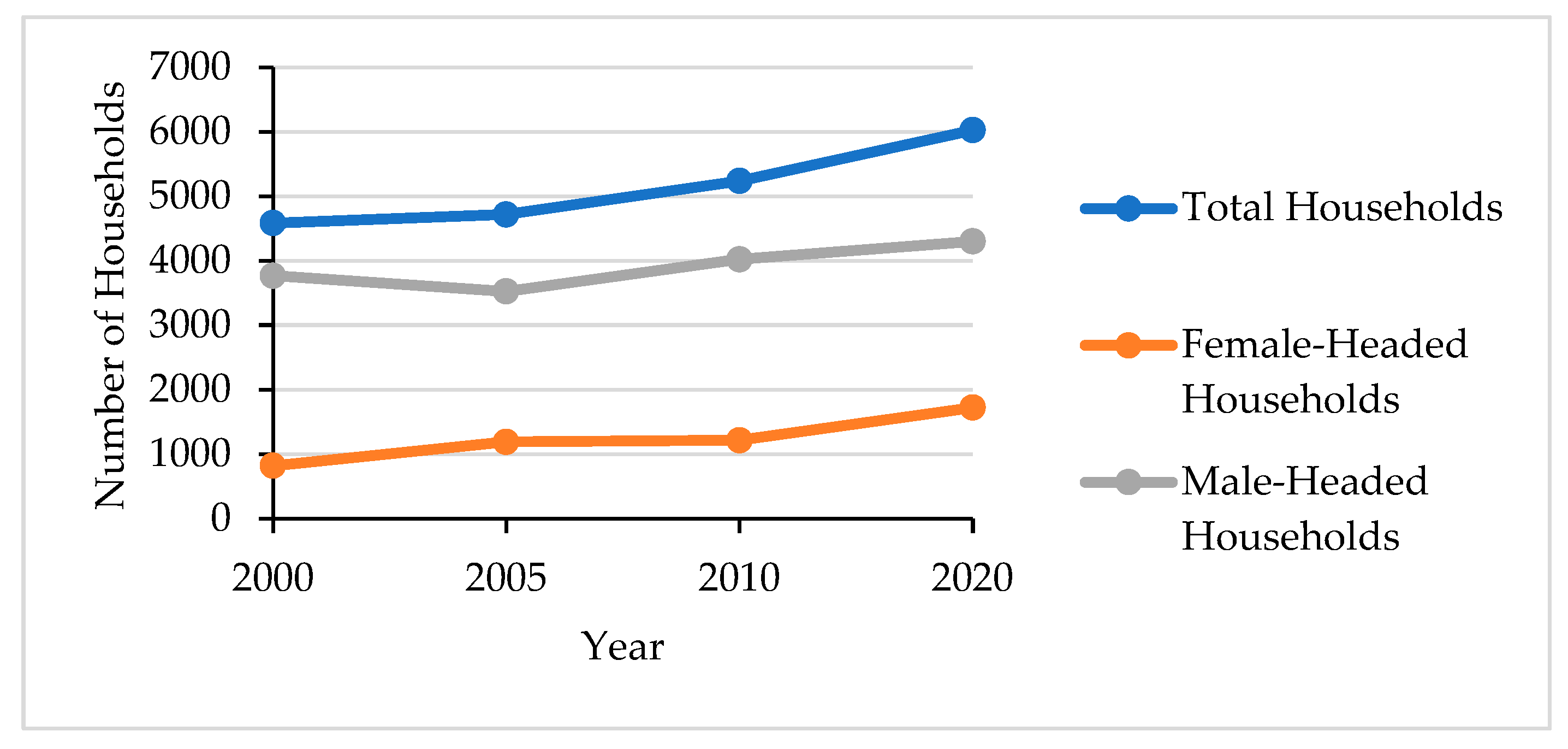

4.2. Socioeconomic Dynamics and Gender Roles

4.3. Gendered Territorial Practices Across Socio-Ecological Zones

4.4. Adaptive Land Management in Response to Territorial Change

4.5. Spatial Agency and Biocultural Resilience

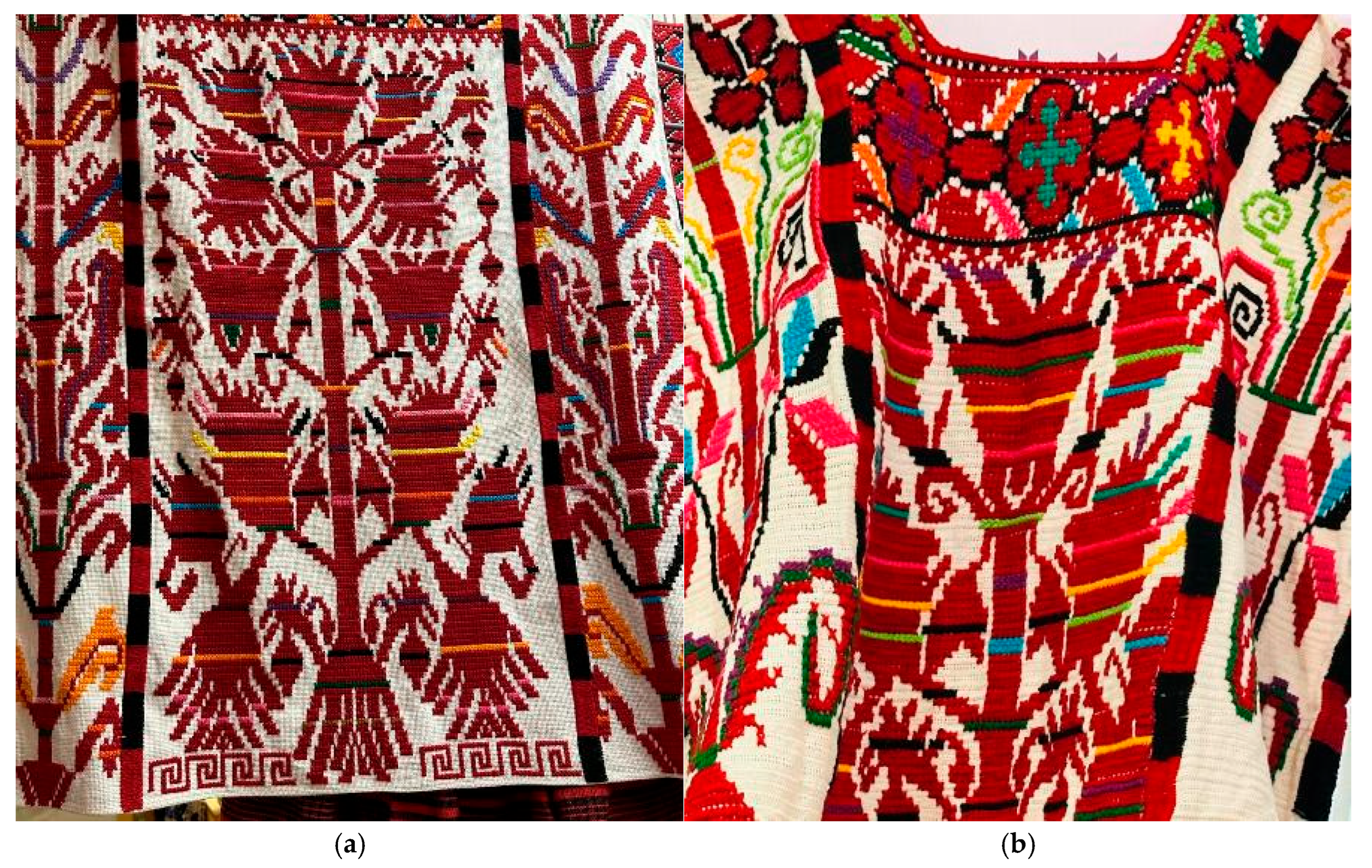

4.6. Weaving Practices and Cultural Continuity

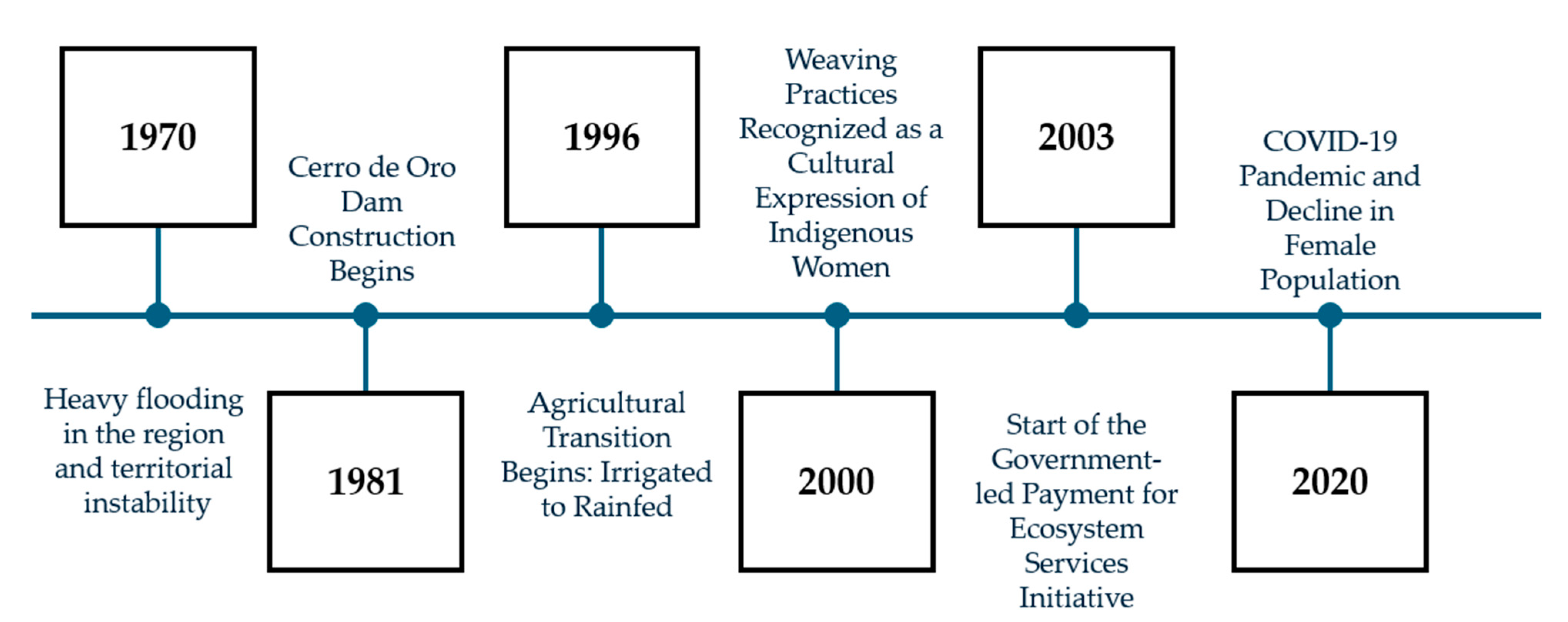

4.7. Historical Drivers of Territorial Transformation

5. Discussion

5.1. Territorial Change as a Historical and Socioecological Process

5.2. Migration, Depopulation, and the Reconfiguration of Rural Life

5.3. Repopulation, Institutional Support, and the Return to Territory

5.4. Women’s Agency, Community Governance, and Biocultural Resilience

5.5. Cultural Heritage, Symbolism, and the Paradox of Recognition

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDI | National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples |

| CONAFOR | National Forestry Commission |

| INEGI | National Institute of Statistics and Geography |

| PTAZI | Alternative Tourism Program in Indigenous Zones |

References

- Marino, D.; Barone, A.; Marucci, A.; Pili, S.; Palmieri, M. The Integrated Analysis of Territorial Transformations in Inland Areas of Italy: The Link between Natural, Social, and Economic Capitals Using the Ecosystem Service Approach. Land 2024, 13, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, S.F.; Carter, D.B.; Ying, L. Historical Border Changes, State Building, and Contemporary Trust in Europe. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2022, 116, 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damayanti, R.W.; Hartono, B.; Wijaya, A.R. Clarifying megaproject complexity in developing countries: A literature review and conceptual study. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2021, 13, 18479790211027414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nito, E.; Caccialanza, A.; Canonico, P.; Favari, E. Analyzing the role of social value in megaprojects: Toward a new performance framework. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2024, 28, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Velasco Pavón, J.C. Economic behavior of indigenous peoples: The Mexican case. Lat. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Padilla, E.; DeSantis, D.L.; Rocha, A.; Fucsko, L.A.; Johnson, J.D.; Lazcano-Villarreal, D. Biological and Cultural Diversity in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico: Strategies for Conservation among Indigenous Communities. Biol. Soc. 2022, 5, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Aquino-Bolaños, T.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; López-Cruz, J.Y. Cultural Heritage, Migration, and Land Use Transformation in San José Chiltepec, Oaxaca. Land 2024, 13, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A. Contribution to the theory of territorial development: A territorial innovations approach. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2193218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živojinović, I.; Elomina, J.; Pülzl, H.; Calanasan, K.; Dabić, I.; Ólafsdóttir, R.; Siikavuopio, S.; Iversen, A.; Robertsen, R.; Bjerke, J.; et al. Exploring land use conflicts arising from economic activities and their impacts on local communities in the European Arctic. J. Land Use Sci. 2024, 19, 186–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepie, A.J. More than Stories, More than Myths: Animal/Human/Nature(s) in Traditional Ecological Worldviews. Humanities 2017, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktürk, G.; Dastgerdi, A.S. Cultural Landscapes under the Threat of Climate Change: A Systematic Study of Barriers to Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dei, G.J.S.; Karanja, W.; Erger, G. The Role of Elders and Their Cultural Knowledges in Schools. In Elders’ Cultural Knowledges and the Question of Black/ African Indigeneity in Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- García, H.D.; García, W.A.; Curcio, C.L. Aging in Indigenous Communities: Perspective from Two Ancestral Communities in the Colombian Andean-Amazon Region. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2024, 39, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.D.; King, N.; Galappaththi, E.K.; Pearce, T.; McDowell, G.; Harper, S.L. The Resilience of Indigenous Peoples to Environmental Change. One Earth 2020, 2, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Fransen, S.; Safra de Campos, R.; Clark, W.C. Migration and sustainable development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2206193121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; Granados-Echegoyen, C.A. Women’s Leadership in Sustainable Agriculture: Preserving Traditional Knowledge Through Home Gardens in Santa Maria Jacatepec, Oaxaca. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Casas, R. Todo sea para el Desarollo: El reacomodo de comunidades indígenas por la construcción de represas en el Alto Papaloapan. Público Priv. 2022, 20, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, J. The Construction of Dams in Mexico: Evolution, Current Situation and New Approaches for the Viability to Water Infrastructure. Gest. Politica Publica 2019, 28, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A.; Garber, P.A.; Gouveia, S.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Ascensão, F.; Fuentes, A.; Garnett, S.T.; Shaffer, C.; Bicca-Marques, J.; Fa, J.E.; et al. Global importance of Indigenous Peoples, their lands, and knowledge systems for saving the world’s primates from extinction. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.d.L.Q. Territory, Memory and Gender: The meanings of women’s political participation in Atenco, México. Ambiente Soc. 2019, 22, e01161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maybom, C.; Funder, M.K. Women’s agency in environmental interventions: Navigating “resilient livelihoods” in Kenya. Geoforum 2025, 164, 104343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Díaz, P.; Armenta-Ramírez, A.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Schumacher, M. Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico. Land 2020, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, M. Women’s changing productive practices, gender relations and identities in fishing through a critical feminisation perspective. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 78, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, J.; Wangu, J. Women’s dual centrality in food security solutions: The need for a stronger gender lens in food systems’ transformation. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 3, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujko, A.; Karabašević, D.; Cvijanović, D.; Vukotić, S.; Mirčetić, V.; Brzaković, P. Women’s Empowerment in Rural Tourism as Key to Sustainable Communities’ Transformation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogan, G.; Dooley, K. Weaving together social capital to empower women artisan entrepreneurs. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2023, 16, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K. El Hilo Continuo: La Conservación de las Tradiciones Textiles de Oaxaca; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E. Comunidades en la Chinantla Oaxaca conservando bosques y selvas: Impulso de iniciativas locales. Cienc. Agronómicas Apl. Biotecnol. 2023, 3, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Peluso, N.; Lund, C. New frontiers of land control: Introduction. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, C. El Huipil de Valle Nacional, en Peligro de Extinción; Solo Ocho Personas Luchan por su Rescate. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4V3S2WclA_4&t=1s (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- BBVA México. BBVA en las Actividades de la Guelaguetza 2024. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AZ7wD7k0yhI (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- FAHHO. Huipil Chinanteco de Valle Nacional. Available online: https://repositorio.fahho.mx/handle/123456789/36336 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Jerónimo Santiago, M. Huipiles de Valle Nacional: Arte y Mitología; Secretaría de Cultura del Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca: Oaxaca, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, L. Valle Nacional a Través de ss Huipiles. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=10155499828726954 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Secretaría de las Culturas y Artes de Oaxaca (SECULTA). Bordado y Huipil Chinanteco. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FM2-sWBcsJg (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Secretaría de las Culturas y Artes de Oaxaca (SECULTA). Explicación del Significado de las Partes del Huipil Capsula 14. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j_qmkHdtAbw (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- SiCmexico. Textilería de San Juan Bautista Valle Nacional. Available online: https://sic.gob.mx/ficha.php?table=frpintangible&table_id=368 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Nance, D.; Lopez, O. The Emotional Meaning of Dress for Older Oaxacan Women: Identity, Pride, Racism and Nostalgia in Twenty-First Century Mexico. J. Dress Hist. 2022, 6, 24–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M.; McRuer, J.; Liu, X.; Theron, L.C.; Blais, D.; Schnurr, M.A. Social-ecological resilience through a biocultural lens: A participatory methodology to support global targets and local priorities. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Reyes, J.E. Biocultural Diversity Conservation: A Global Sourcebook; Francis, T., Ed.; Earthscan: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Swiderska, K.; Argumedo, A.; Wekesa, C.; Ndalilo, L.; Song, Y.; Rastogi, A.; Ryan, P. Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems and Biocultural Heritage: Addressing Indigenous Priorities Using Decolonial and Interdisciplinary Research Approaches. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, A.; Gligor, V.; Nicula, E.-A.; Domnița, M.; Alexe, M. The Biocultural Resilience Index (BRI): A New Tool for Assessing the Sustainability of Multifunctional Landscapes. Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Panorama Sociodemográfico de México. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Gobierno de México, D.M. San Juan Bautista Valle Nacional. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/san-juan-bautista-valle-nacional (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Gobierno de México. Informe Anual Sobre la Situación de la Pobreza y Rezago Social 2024. San Juan Bautista Valle Nacional. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/889133/20559SanJuanBautistaValleNacional2024.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Mora-Díaz, I.N. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo San Juan Bautista Valle Nacional 2011–2013. Available online: https://sisplade.oaxaca.gob.mx/bm_sim_services/PlanesMunicipales/2011_2013/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Secretaría de Turismo de Oaxaca. Ruta de la Chinantla. Available online: https://tuxtepecturismo.com/que-ver-y-hacer/ruta-chinantla/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- ESRI. ArcGIS. Available online: www.esri.com (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie I. Continuo Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007020 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie II. Continuo Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007021 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie III. Continuo Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007022 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie IV. Conjunto Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007023 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie V. Conjunto Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007024 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Conjunto de datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie VI. Conjunto Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463598459 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie VII. Conjunto Nacional. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463842781 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Datos Abiertos. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/datosabiertos/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Lima, P.T.; Valdiviezo, A.C. La Chinantla oaxaqueña: La historia de un patrimonio perdido. Diseño Soc. 2016, 1, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Romero, A. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo San Juan Bautista Valle Nacional 2008–2010. Available online: https://sisplade.oaxaca.gob.mx/bm_sim_services/PlanesMunicipales/2008_2010/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Benrey, B.; Bustos-Segura, C.; Grof-Tisza, P. The mesoamerican milpa system: Traditional practices, sustainability, biodiversity, and pest control. Biol. Control 2024, 198, 105637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez-Nolasco, S.G. Impacto Territorial del Cultivo del Algodón en el Estado de Oaxaca, México; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- de Teresa, A.P. Del porfiriato a la Revolución: La propiedad de la tierra en la parroquia de Valle Nacional, Oaxaca, 1884-1915. Cuad. Sur 2020, 1, 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, G. The Forgotten Jaramillo: Building a Social Base of Support for Authoritarianism in Rural Mexico. In Dictablanda: Politics, Work, and Culture in Mexico, 1938–1968; Gillingham, P., Smith, B., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez Núñez, M. El agua en la región de la Chinantla, México. Estudio comparativo de una cosmovisión chinanteca a partir de su tradición oral. Boletín Lit. Oral 2019, 9, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Teresa, A.P. Población y recursos en la región chinanteca de Oaxaca. Desacatos 1999, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional Forestal. Conservación—Programa de Pago por Servicios Ambientales. Available online: https://snif.cnf.gob.mx/conservacion/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Stephen, L. Women’s Weaving Cooperatives in Oaxaca. Crit. Anthropol. 2005, 25, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Rosales, R.; de Jesús-Almonte, L.; Carbajal-Suárez, Y. Empleo, producción y salario manufacturero en México ante la pandemia por la COVID-19. Un análisis de VAR espacial. Cienc. Administrativas. Teoría Prax. 2022, 17, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillon, S.; Cullman, G.; Verschuuren, B.; Sterling, E.J. Moving beyond the human–nature dichotomy through biocultural approaches: Including ecological well-being in resilience indicators. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobernación, S.d. Movilidad Humana Oaxaca. Available online: https://portales.segob.gob.mx/work/models/PoliticaMigratoria/CPM/foros_regionales/estados/centro/info_diag_F_centro/info_Oaxaca.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Lugo Espinosa, G.; Acevedo Ortiz, M.A.; Ortiz Hernández, Y.D. Conservación de semilla criolla y control biológico, resguardo del patrimonio biocultural de la Chinantla Oaxaca. In Nuevas Territorialidades-Gestión de los Territorios y Recursos Naturales con Sustentabilidad Ambiental; Sarmiento-Franco, J.F., Ed.; UNAM-AMECIDER: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Aquino-Bolaños, T. Huertos familiares y participación comunitaria para la generación de medios de vida sostenibles. In Los Objetivos del Desarrollo Sostenible versus la Pandemia de la COVID-19, 1st ed.; Tavera-Cortés, M.E., Ed.; ASMIIA: Texcoco, Mexico, 2023; pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. Programa Turismo Alternativo en Zonas Indígenas (PTAZI). Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Informes/Evaluacion/Consistencia/2007_2008/CDI/Programa%20Turismo%20Alternativo%20en%20Zonas%20Ind%C3%ADgenas%20(PTAZI).pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Githapradana, W.; Raharja, G.; Ratna, T.; Pebryani, N. Gender and Culture Inclusivity in the Story of Hope Fashion Collection. ARCHive-SR 2024, 8, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, S.; Zepeda, L. Vestir la Resistencia: Mujeres Indígenas Frente a la Violencia Patriarcal. Available online: https://www.zonadocs.mx/2022/03/22/vestir-la-resistencia-mujeres-indigenas-frente-a-la-violencia-patriarcal/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Gracia, M.A.; Horbath, J.E. Condiciones de vida y discriminación a indígenas en Mérida, Yucatán, México. Estud. Sociológicos 2019, 37, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land Use | 1992 | 2001 | 2005 | 2009 | 2013 | 2017 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irrigated agriculture | 3934 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Seasonal rainfed agriculture | 78 | 4811 | 5191 | 5082 | 4781 | 10,283 | 10,290 |

| Pine-oak Forest | 131 | 819 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Montane cloud forest | 2961 | 4100 | 4034 | 4034 | 4047 | 4047 | 4047 |

| Permanent cultivated grassland | 1043 | 819 | 622 | 706 | 1221 | 1515 | 1631 |

| Tall evergreen rainforest | 22,398 | 8406 | 40,526 | 40,622 | 41,924 | 39,339 | 37,627 |

| Secondary shrubby vegetation of tall evergreen rainforest | 23,606 | 22,088 | 10,669 | 10,598 | 9067 | 4198 | 3713 |

| Secondary arboreal vegetation of tall evergreen rainforest | 14,289 | 28,005 | 7188 | 7188 | 6344 | 8656 | 10,616 |

| Urban zone | 0 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 356 | 356 | 456 |

| Water bodies | 0 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 49 | 63 |

| Ecosystem Type | Management Practices by Women | Spatial Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Rainfed agricultural plots | Seasonal cropping, maize–bean intercropping, soil conservation | Hillsides, former irrigation zones, marginal terrain |

| Home gardens | Seed saving, vegetable cultivation, medicinal plants, poultry raising | Adjacent to homes, fenced patios or backyards |

| Milpa–agroforestry systems | Integration of fruit trees, coffee, native timber, shade crops, and small-scale cotton cultivation for artisanal use | Edges of secondary forests, partially shaded areas, interspersed crops |

| Permanent cultivated grasslands | Fodder cultivation, rotational grazing, water access planning | Lowland pastures, individual or communal plots, near rivers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; Tavera-Cortés, M.E. Land Use Change and Biocultural Heritage in Valle Nacional, Oaxaca: Women’s Contributions and Community Resilience. Land 2025, 14, 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091735

Lugo-Espinosa G, Acevedo-Ortiz MA, Ortiz-Hernández YD, Ortiz-Hernández FE, Tavera-Cortés ME. Land Use Change and Biocultural Heritage in Valle Nacional, Oaxaca: Women’s Contributions and Community Resilience. Land. 2025; 14(9):1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091735

Chicago/Turabian StyleLugo-Espinosa, Gema, Marco Aurelio Acevedo-Ortiz, Yolanda Donají Ortiz-Hernández, Fernando Elí Ortiz-Hernández, and María Elena Tavera-Cortés. 2025. "Land Use Change and Biocultural Heritage in Valle Nacional, Oaxaca: Women’s Contributions and Community Resilience" Land 14, no. 9: 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091735

APA StyleLugo-Espinosa, G., Acevedo-Ortiz, M. A., Ortiz-Hernández, Y. D., Ortiz-Hernández, F. E., & Tavera-Cortés, M. E. (2025). Land Use Change and Biocultural Heritage in Valle Nacional, Oaxaca: Women’s Contributions and Community Resilience. Land, 14(9), 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091735