Abstract

This paper explores the concept of ephemeral cultural landscapes through the lens of public election advertising during the 2025 Australian Federal election in the regional city of Albury, New South Wales. Framing election signage as a transient cultural landscape, the study assesses the distribution of election signage (corflutes) disseminated by political candidates against demographic and socio-economic criteria of the electorate. The paper examines how corflutes and symbolic signage reflect personal agency, spatial contestation, and community engagement within urban and suburban environments. A detailed windscreen survey was conducted across Albury over three days immediately prior to and on election day, recording 193 instances of campaign signage and mapping their spatial distribution in relation to polling booth catchments, population density, generational cohorts, and socio-economic status. The data reveal stark differences between traditional party (Greens, Labor, Liberal) strategies and that of the independent candidate whose campaign was marked by grassroots support and creative symbolism, notably the use of orange corflutes shaped like emus. The independent’s campaign relied on personal property displays, signaling civic engagement and a bottom-up assertion of political identity. While signage for major parties largely disappeared within days of the election, many of the independent’s symbolic emus persisted, blurring the temporal boundaries of the ephemeral landscape and extending its visual presence well beyond the formal campaign period. The study argues that these ephemeral landscapes, though transitory, are powerful cultural expressions of political identity, visibility, and territoriality shaping public and private spaces both materially and symbolically. Ultimately, the election signage in Albury serves as a case study for understanding how ephemeral landscapes can materially and symbolically shape public space during moments of civic expression.

1. Introduction

Cultural landscapes represent past and present human interactions with their environment, thereby commonly leaving observable and tangible traces of events and activities on a larger micro- or macro-landscape scale [1]. Commonly, such cultural landscapes are ascribed a value by the community and are regarded as cultural heritage. On other occasions, cultural landscapes are more ephemeral or transient and do not persist long enough for heritage values to emerge.

Broadly speaking, cultural heritage emerges from the interactions between people and their environment, as well as the interactions between people themselves. Intangible cultural heritage is derived from human relationships and is primarily reflected in elements such as language, technical skills, folklore, customs, and traditions [2]. Intangible heritage also exists in the sensorial space, primarily visual and auditory [3] but also olfactory [4]. In contrast, the interaction between people and their environment generates aspects of tangible heritage as manifested in the form of built structures (e.g., buildings, roads) or modifications to the natural environment (e.g., mining, agriculture). Tangible heritage also encompasses a variety of movable objects and artifacts of different forms and materials (e.g., tools, objects of art). In addition, we need to consider an emergent third domain, that of virtual heritage, which considers an intangible digital dimension of human–machine interaction [5]. What defines these interactions as “heritage” is the cultural significance that a community assigns to them [6,7]. In addition to cultural heritage, we need to consider natural heritage, an environmental space that is valued by the current generations for its seemingly unspoiled and unmodified characteristics [1]. These assigned values, which are mutable qualities [8], motivate community efforts to preserve and manage this natural, tangible and intangible heritage for the benefit of the current population [9,10,11] and, purportedly, also for future generations [12]. While most heritage assets are managed or curated as single units, some may be aggregated in the form of heritage conservation areas [13]. A different kind of spatially circumscribed heritage asset is cultural landscapes.

In its traditional/orthodox framing, an interpretation and analysis of cultural landscapes is focused on the tangible manifestations, such as landscape modification change, archeological evidence, structural evidence, or cultural plantings. Even though exceptions exist [14], cultural landscapes do not tend to represent an unadulterated ensemble of past land use. Rather, cultural landscapes are a palimpsest of one or more phases of past cultural interactions that are overlain by modern contemporary land use [15,16]. Viewed from a First Nations, as well as an Indigenist, standpoint [17], this landscape space extends, and always has extended, to the cultural attachment and the valuing of seemingly ‘natural’, unmodified landscape features that have cultural and spiritual meaning and significance to First Nations communities [18,19,20]. An intangible manifestation of cultural landscapes are toponymic landscapes, where settler colonialist societies supplanted the First Nations appellations of localities, natural and spiritual features with colonial imports or phonetic bastardizations of First Nations names [21,22,23]. In addition to these permanent cultural landscapes, we need to consider the phenomenon of ephemeral landscapes and place these into the cultural heritage context.

1.1. Ephemeral Landscapes

By definition, ephemeral landscapes are impermanent transient manifestations of natural or cultural phenomena within a spatially circumscribed dimension. The attributes of these landscapes, in common parlance, are that they are tangible and visually interpretable. Excluded from this paper are additional intangible, sensory dimensions that may add to or enhance the perceived value and significance of these ephemeral landscapes, such as soundscapes [24,25,26] and smellscapes [4,27,28].

Ephemeral landscapes are commonly seen through a geomorphological lens [29], associated with natural phenomena. Examples are the flooding of Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre, an endorheic lake in the far north of South Australia [30], the annual inundation of river floodplains [31] or ephemeral wetlands [32]. Beyond this, ephemeral landscapes can be regularly reoccurring, such as seasonal landscapes; transitory, such as peri-urban zones; or as temporary transformations of persistent landscapes.

Seen through another environmental lens, seasonal landscapes not only reflect the visual appearance of seasonally variable vegetation (natural or planted as crops), its flowering and coloring [33,34,35,36], but also find manifestation in harvesting features (large haybales) [36], as well as in economic and communications systems [37]. Transhumance, for example, has been a long established way of life in the alpine areas of Europe [38,39,40], South America [41,42], and Asia [43,44] but also North America [45,46], and Australia [47,48]. Likewise, some tracks and roads may be closed due to snow and ice in winter (e.g., some mountain passes) or due to thawed and boggy ground in summer, while frozen lakes and estuaries may allow for direct communication across the ice that is impossible in summer and requires longer, circum-estuary trips or ferry rides [49].

In the urban planning space, the concept of ephemeral landscapes has been applied to peri-urban areas within the urban growth corridor. Traditionally, an expanding urban space saw the peri-urban belt of orchards being replaced by dwellings, while new orchards were developed on former pastures and arable land. More recently, these orchard belts are no longer replanted, with the urban fringe dominated by pastures and arable land that see a lower level of care, especially when already purchased by developers waiting for the right economic conditions to commence construction [50]. Here, the ephemerality is represented by transitory existence between two stable states.

A third ‘class’ of ephemeral landscapes are temporarily circumscribed cultural landscapes. Commonly, these are transformations planned by authorities, such as garden festivals that transform a peri-urban space into a complex, primarily flower-based tourist landscape replete with structures (e.g., the German Bundesgartenschau) [51,52], or International Exhibitions (Expos) that create temporary communities with usually ephemeral architecture [53]. Likewise, theme parks are imagined ephemeral landscapes [54,55,56] that will persist as long as they remain commercially viable. Other examples, on a smaller scale, are transformations of roads into urban parklets [57,58], roads along river fronts into temporary beaches [51], town squares converted into Christmas market villages [59] and streets illuminated with Christmas decorations [60,61]. While intended as ephemeral in their ‘original’ presentations, some elements of these ephemeral transformations may not revert back to the prior status quo once the festival ends, but may be retained, thereby generating a new permanent cultural landscape layer [62,63]. Examples are Balboa Park in San Diego as a remnant of the 1915 Panama–California Exposition [64] or elaborate film sets that have been retained as tourist attractions, such as ‘‘Hobbiton’ (Lord of the Rings) in New Zealand [65] or ‘Tatooine’ (Star Wars) in Tunesia [66].

Finally, there are event-based ephemeral landscapes that are reactive to the event and manifest themselves for its duration. An example are the ad hoc testing stations that were established during the COVID-19 pandemic [67,68].

1.2. Personal Agency in Ephemeral Landscapes

While the majority of ephemeral landscapes are generated by natural phenomena or through communal or governmental control, some ephemeral landscapes can be created by individual or personal agency. These landscapes can be created by individual or collective expressions of custom, tradition or political opinion. These can range from sanctioned [69] and unsanctioned (‘guerilla’) privately created gardens in public spaces [70] to ritualized expressions of nationalism, such as homeowners flying the US flag each year on Independence Day (4 July) [71] or the yellow ribbon campaign during the first Iraq war (1990) [72,73]. Collective, socially acceptable personal agency can generate public landscapes by decorating the exterior of private residences for Halloween [74,75] or Christmas [76]. Communal art projects reclaiming urban spaces, such as yarn bombing [77,78], create ephemeral landscapes that are welcomed or tolerated by the wider community. Similar personal ephemeral art projects, reclaiming urban spaces in the form of graffiti [79,80,81,82], are widely perceived as anti-social behavior. While yarn bombing and graffiti are expressions of territoriality in an ephemeral landscape, Halloween and Christmas decorations are individual, yet collective expressions of community-wide customs. The display of national flags as well as political stickers and posters are expressions of political opinion that create a visually recognizable ephemeral landscape.

The temporality of these ephemeral landscapes differs. While some are defined by cyclical events at fixed (Halloween, Christmas) or semi-regular intervals (elections) with a well-defined duration, others can be event-based and manifest themselves for the duration of that event (yellow ribbon campaign).

Another type of ephemeral landscapes are political landscapes created in the run-up to elections, which find their visual expression on election posters on power poles, fences and houses. Election posters are not merely visual artifacts of political messaging but reflect deep-seated power dynamics related to political dominance, socioeconomic stratification, and territorial ‘control’ as manifested where posters appear, how densely they are distributed, and on whose property they are placed.

1.3. Political Landscapes

Political landscapes are commonly considered in their intangible form, conceptualizing the relationships of political parties with their voters in the social and geographical [83,84] or the digital space [85]. In these contexts, the term ‘landscape’ is used metaphorically rather than referring to a physical entity [86]. Yet political landscapes can also have a permanent, or at least semi-permanent, tangible form where political power manifests itself in structures of dominance such as the now largely demolished socialist architecture of the former German Democratic Republic [87], or structures of exclusion and inclusion, such as the Berlin Wall, and the border wall between Mexico and the USA [88]. Political landscapes can also be tangible, yet transitory, such as temporary urban destruction following civic riots [89,90], or they can be fully ephemeral, such as election signage of protest signage. There is a limited body of work that considers election signage in the form of yard signs as expressions of political cultural landscapes in the USA [91,92,93,94] and papers that contextualize the nature and spatial distribution of protest signage, responding to a natural disaster event in Florida (USA) [95] and responding proposed development in an Australian setting [96]. Some studies have suggested that the socio-economic makeup of a suburb or neighborhood will find expression in the nature and messaging on formal election signage as well as individualized yard signage [91,92,94,97]. A very small number of studies looked at the spatial distribution and density of campaign signage in suburban spaces correlating them with socio-economic and ethnic data [91,92].

In this paper we will consider the ephemeral cultural landscape of an Australian Federal election as it is represented by public election advertising, using a regional community as an example. We will demonstrate that Australian ephemeral landscapes are culturally influential, if not significant, and that they can shape public and private spaces both materially and symbolically. To do so, we will first provide a contextual background on the Australian electoral system as well as the study community. Following an explanation of the methodology espoused, we will discuss the spatial distribution of electoral signage in relation to demographic and socio-economic parameters.

2. Background

2.1. Background to Federal Elections in Australia

The House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Australia is re-elected every three years as is half of the Senate, unless a double dissolution has been called (when the entire Senate is reelected). The House of Representatives is made up of directly elected representatives chosen by popular vote from all citizens residing and being registered in the 150 electoral divisions (henceforth ‘electorates’) which are single member constituencies [98]. The electorates are broadly of the same population size (~120,000 people) but because of the uneven spatial distribution of Australia’s population, these electorates differ widely in geographical size [98]. Thus they can be spatially very small, such as the electorate of Wentworth which comprises parts of northern Sydney (NSW) with an area of 31.2 km2 (127,588 voters), or very large, such as the electorate of Durack in Western Australia with an area of 1.41 million km2 (118,845 voters) [99]. The boundaries of the electorates are defined by an independent, apolitical body, the Australian Electoral Commission. Gerrymandering, a common feature of U.S. politics [100,101], does not exist in Australia. The candidate with the highest number of votes in each electorate after the distribution of preferences (see below) takes the seat in parliament. The Senate is made up of party-nominated candidates based on the proportion of votes that party receives in a given state, with the number of seats per state defined in the constitution of 1901 [98]. Voting in an Australian Federal or State election is compulsory for every citizen over the age of 18 residing in Australia and registered to vote [64].

Voting occurs via in-person voting at any of the voting centers (‘polling booths’) within the electorate, in-person voting at polling booths outside the electorate (absentee voting), in person voting prior to election day at specific pre-poll voting centers within the electorate (pre-poll voting), or mailed-in ballot papers (postal ballot) and phone votes for people with severe physical disabilities [64]. The distribution and location of polling booths is driven entirely by spatial and access considerations. School halls tend to be the preferred venue as they are held in public hand (land?), are vacant on election days (which are always held on a Saturday) and, being in primary and high schools, tend to be spatially well distributed.

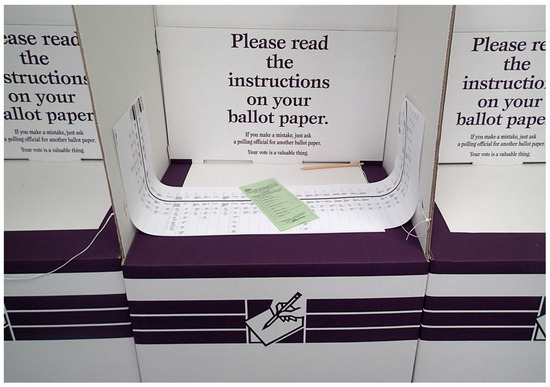

Voting is based on the preferential system, where voters are given printed ballot papers (green for the House of Representatives and white for the Senate), enter a cardboard booth and are required to indicate their preferences by entering a number in delineated boxes next to the candidates’ names. For ballots for the House of Representatives, voters are required to number all boxes 1 (for their first preference), 2 (for their second preference), 3 and so on until all boxes are numbered. Failing to number boxes, omitting or doubling up numbers, or annotating the ballot paper in any way results in the ballot paper being declared invalid (‘informal’) and excluded from the count of the valid (‘formal’) votes [64]. In the case of the 2025 election, the ballot paper for the electorate of Federal (Farrah?), which contains Albury, carried nine names. The order in which these names are listed are drawn at random [102]. Being on top of the list provides a small vote windfall as some people, simply in order to fulfill their voting obligations, number the candidates sequentially from top to bottom (‘donkey vote’) [64]. The ballot paper for the Senate comprises the parties arranged (again by random allocation) from left to right. Voters are given the opportunity to vote for a party above a horizontal line on the ballot paper and which case they are obliged to allocate their preference to at least six parties, or they may choose to allocate their preferences to individual candidates, arranged by party, below that line. In that case, 25 candidates need to be allocated sequential preference numbers (Figure 1) [64].

Figure 1.

Example of a cardboard voting booth with pencil and the ballot papers for the House of Representatives (green) and the Senate (white). Note how the long Senate ballot paper curls up on both sides. Federal election 2013. (Photograph DHRS 2013).

After close of voting, usually 6 p.m. on voting day, all ballots are counted by sorting them according to the first preferences (i.e., boxes with the number 1). The candidate with the lowest number of primary votes is excluded and the ballot papers with first preferences for that candidate redistributed to the other candidates based on the second preference marked on the paper. That exclusion and redistribution process continues until only two candidates remain, with the candidate obtaining the highest number of votes being declared the winner of the parliamentary seat [64].

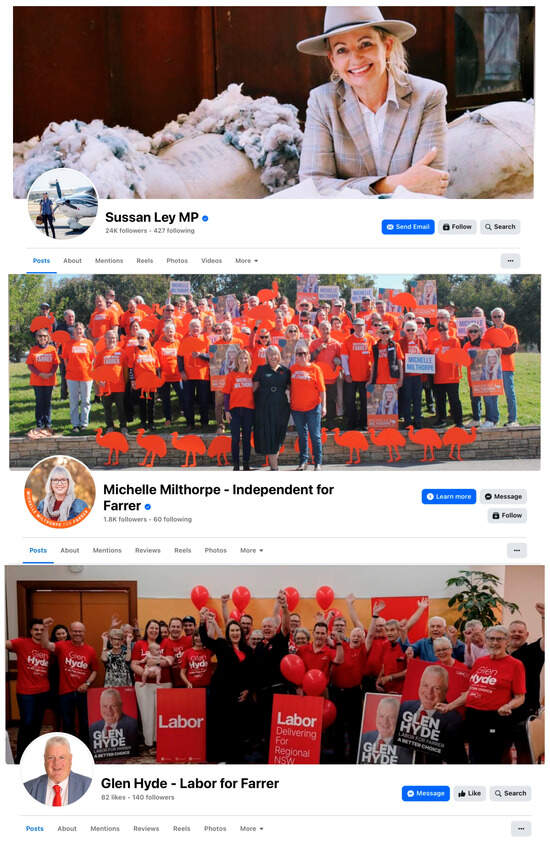

2.2. Background to Election Advertising

Campaigning in the 2025 Federal election involved a variety of media ranging from ‘traditional’ physical mailouts, letter box drops and advertising posters, ‘corflutes’ (weather-resistant 3–5 mm thick sheets of corrugated polypropylene plastic), as well as television advertisements, and social media campaigns via Instagram, and Facebook (Figure 2). One party made ‘a name for itself’ by sending out unsolicited text messages to people’s phones [103]. On election day, party volunteers positioned near the entrances to the polling booths were handing out how to vote cards (Figure 3) that are aimed at undecided voters and that indicate a party’s preferred sequence of preferences (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Screen shots of Facebook banners of three candidates polling the most votes in the electorate of Farrer in the 2025 Federal election.

Figure 3.

Volunteers handing out how-to-vote cards for the 2025 Federal election at the Thurgoona East polling booth, Albury. Note the corflutes. (Photo DHRS 2025).

Figure 4.

A selection of how-to-vote cards produced for the Farrer electorate for the 2025 Federal election (Photo DHRS 2025).

While the public display of election material is permitted from the time an election is called until the end of election day, and while there are rules related to the nature and conduct of election campaigning and advertising [104,105], there are no restrictions from the perspective of electoral law other than a requirement they not be placed within 6 m of a polling place [105,106]. The public posting of election posters and corflutes is governed by laws and regulations relating to political signage as promulgated by state government (for example with regard to placing placards on electricity poles) and local council (in regard to placing placards on private fences and properties that can be seen from the street). In consequence, there is considerable variation across Australia [106,107,108].

Commonly permitted are advertising posters mounted on private properties as long as they do not exceed the standard ISO A1 size (841 × 594 mm). Advertising material larger than this may require council approval, which may not be granted, requiring candidates to take down the offending posters (Figure S6) [109].

While this is not the venue to discuss in detail the relative merits of advertising and campaign approaches and the target audiences that these are reaching, or the amount of waste that they are generating [110,111], some comments are warranted to contextualize the data set of corflutes that will be drawn on for this paper. Broadly, social media advertising has become a major plank of political messaging prior to and during the election period, largely displacing static media such as election posters, as well as reducing the relevance of TV advertising (Figure 2) [112,113,114]. Yet, because of the low cost and relative permanence, election posters persist in the tool kit of campaign managers.

Corflutes, which because of their durability have long since replaced paper and car-board posters, are a well-established means of political communication [115] that provides visual exposure and recognition for candidates, in particular those that lack established recognition (such as incumbency) or exposure in other media [107,115,116,117]. The placement of corflutes has also been theorized as a means of projecting strength [117,118] and visually claim territory by deliberate and strategic placement in prominent positions, thereby generating free news media coverage [107] through repeated recognition of a familiar face in order to generate a personal vote [119].

2.3. Background to Albury

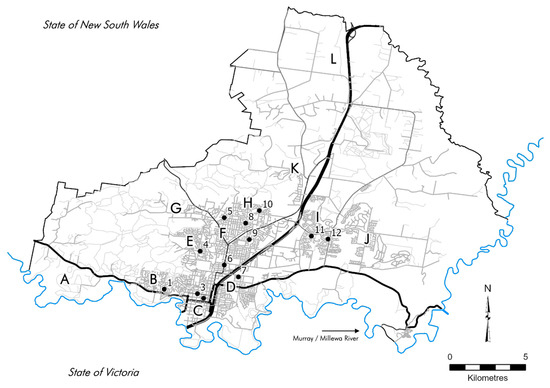

Albury is a regional service center in the southern Riverina area of New South Wales (Australia) located at the northern banks the Millewa/Murray River [120]. Based on the 2021 census, Albury’s population in 2025 was 56,084 people, approximately 77.5% of which were of election age [121]. The local government area (LGA) of Albury comprises the town’s historic nineteenth century core in the south (Central and South Albury), early twentieth century subdivisions surrounding that core, mid-twentieth century subdivisions in the north (merging the village of Lavington), late twentieth century subdivisions in the west and north together with the emerging satellite community of Thurgoona in the north east, as well as twenty-first century subdivisions in the north and in the Thurgoona area (Figure 5) [120,122].

Figure 5.

Map showing the Albury local government area with suburb terms used as well as the locations of the polling booths. Suburbs: A—Splitters Creek; B—West Albury; C—South Albury; D—East Albury; E—Glenroy; F—Lavington; G—Hamilton Valley; H—Springdale Heights; I—Thurgoona; J—Wirlinga; K—Ettamogah; L—Table Top. Polling Booths: 1—Albury West Public School; 2—Albury Public School (Hall); 3—Albury High School; 4—Glenroy Public School; 5—Lavington Public School; 6—Albury North Public School; 7—Albury East; 8—Lavington East Public School; 9—Hume Public School; 10—Springdale Heights Public School; 11—Thurgoona Public School; 12—Thurgoona Community Centre.

2.4. Background to the Federal Electorate of Farrer

Albury is the largest community in the predominantly rural electorate of Farrer, which, with an area of 126,563 km2, forms the geographically largest electorate in NSW, extending from the South Australian border in the west to Jingellic in the east. The boundaries of the electorate for the 2025 election were circumscribed by the boundaries of local government areas, encompassing the cities of Albury and Griffith (population 27,086) as well as the rural shires of Albury City, Balranald, Berrigan, Carrathool, Edward River, Federation Council, Greater Hume, Hay, Leeton, Murray River, Murrumbidgee, Narrandera, and Wentworth (Figure S1) [123].

Given the largely rural population, the electorate of Farrer is traditionally a politically conservative area that has been held by conservative politicians since its creation in 1949 [124]. In the past seven elections it has been held by the Liberal Party by a considerable margin, ranging from 61.2% in 2007 to 70.5% in 2016 (two-party preferred vote) [125,126]. When considering the two-party preferred votes over time, it should be noted that the boundaries of the electorate had been readjusted to the current boundaries in 2016 [123,127]. This entailed excluding the City of Broken Hill that had been included in the electorate since 2007 [128,129] and that had a more left leaning population.

2.5. Election Results 2025

At the 2025 election, nine candidates nominated for the electorate of Farrer, the positions on the ballot paper were determined on 11 April 2025 [130] (Table S2). The total eligible (enrolled) voting population in the electorate of Farrer for the 2025 election was 123,827 persons [131] with 112,522 votes cast [132]. Of these, 8.4% were informal [133]. The election was called on 28 March 2025 [134]. Pre-polling opened on 21 April, two working weeks before the election on 3 May 2025. Albury was serviced by two pre-polling centers; one located in the Albury CBD and one in Lavington. Pre-poll votes made up 58.5% of the total of 32,133 votes cast in combined Albury polling booths (Table 1).

Table 1.

First preferences (in % of formal votes) received at the Albury booths [133]. Abbreviations: G’roy—Glenroy; HS—High School; Lav—Lavington; PS—Public school; SHts—Springdale Heights; Tb Top—Table Top.

After full distribution of preferences, Sussan Ley won the election with 56.19% of all eligible votes cast [132]. The previously referred to conservative character of the rural spaces in Farrer becomes clear when one considers the percentages of the top five vote winners (Table 2).

Table 2.

First preferences (in % of formal votes) cast in Albury compared with votes cast in the rest of the Farrer electorate.

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey

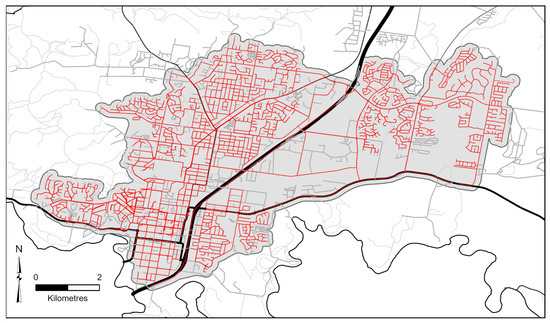

The survey area focused on the key populated areas of Albury as well the arterial roads in and out of the Albury CBD (Figure 6). The spatial distribution of the public advertising material, comprised on posters or corflutes, cut out party symbols (emus, see below) as well as other election messaging, was mapped via a windscreen survey. The windscreen survey, which was carried out on 1 and 2 May 2025 (both DHRS and DD) as well as the morning of 3 May (election day) (DHRS only), entailed systematically driving all streets in the survey area and recording the presence of public advertising material via a field map data collection form hosted on ArcGIS pro 3.5 [135,136]. The survey area was defined as the core of the Albury LGA, omitting the low-density areas of Splitters Creek in the west and Ettamogah/Table Top in the north (see Figure 5 for locations). Figure 6 shows the streets traversed on each of the three days. Not recorded were the corflutes outside the polling stations on election day, as well as the corflutes outside the two pre polling stations in Albury and Lavington [137]. The data recorded were the location of the election advertising, the party it represented, its type (corflute, emu) and whether it was placed on a public or a private space.

Figure 6.

Map showing the area of Albury Local government area surveyed for this study (shaded in grey) with the roads covered in the windscreen survey.

3.2. Analysis

It was posited that most people who had not cast their vote at a pre-poll station would attend the polling booth closest to them. The study area was segmented into twelve polling booth ‘catchments’ based on a detailed road network including footpaths and consisting of an attribute of length in meters [138]. A Closest Facility analysis established routes from the centroid of each property to the closest polling booth, followed by an aggregation into booth ‘catchments’ via a Service Area analysis (Figure S2).

The distribution of election posters is plotted against Australian Bureau of Statistics census data (census 2021) at the census mesh block level where specific data sets are available (e.g., population density) [139] or otherwise against Statistical Area Level 1 (cell) data (e.g., Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage score) [140].

While census data are presented in 5-year age brackets starting with 0–4, it made more sense to aggregate the ages into generational cohorts (e.g., Generation Y, Baby Boomers) as they share common socio-cultural characteristics (for correlation of cohorts, see Table S4).

3.3. Limitations

The election signage comprises co standard ISO A1 sized (841 × 594 mm) corflutes as well as signs in the shape of emus (large emus ~440 × 550 mm, small emus ~220 × 250 mm) (Figure S3d,e). While corflutes were usually mounted at the property fence or boundary facing the street, some emus were mounted on walls or Colorbond fences that were aligned perpendicular to the street. As these emus could be missed depending on their size and on the direction of vehicle movement, it is likely that the number of orange emus has been undercounted. At least on two occasions such emu signage was noted when the survey sequence required the authors to backtrack on a street that had already been surveyed.

3.4. Statistics

Summary data and frequencies as well as t-test probabilities were calculated using MS Excel, while the statistical comparisons of proportions were established with an on-line comparison of proportions calculator [141].

3.5. Auxillary Data

To improve the readability of the paper, a number of additional tables and figures have been related to a supportive data document. These can be identified by the prefix ‘S’ (e.g., Table S1) and can be accessed from the journal’s web page.

4. Results

The survey identified locations with 193 corflutes and other stationary election signage. Signage for Michelle Mithorpe dominated with 77.2% of all locations, followed by the Liberals (10.0%) and the Greens (7.3%) (Table 3). Setting aside the displays that were displayed at the polling booths on election day, all election signage by the Labor Party, the Greens, the Independent and the Shooters, Fishers & Farmers party was mounted on private properties. On the other hand, one third of the Liberal party’s election signage and the sole National party corflute were placed on public spaces.

Unlike the traditional parties, which all relied on standard A1-sized corflutes, the campaign of the independent also used orange corflutes in the shape of an emu of varied sizes) either blank or with the stenciled text ‘Milthorpe for Farrer’) (Figure S3d,e). These orange emus as a symbol of the independent ‘Voices of Farrer’ campaign, started to appear in some areas well before the candidate had been decided. The symbolism of the orange emu is three-fold: orange as a color for an independent political voice [142] which was successfully used in the success of Independent candidates in the adjacent electorate of Indi [143,144]; the choice of an emu as a typical bird in the Riverina; and the choice of an emu as a bird that symbolizes progress as it cannot easily moved backwards, and that for that reason (like the Kangaroo) is used in the Commonwealth Coat of Arms [145].

Considering only the corflutes promoting the independent candidate, 40.9% of locations displayed just an emu and 35.6% of locations displayed a corflute. Just under a quarter of locations (23.5%) displayed both a corflutes and one or more emus.

Spatially, the majority of corflutes are concentrated in the election booth catchments of central, north central and west Albury, while the lowest numbers were noted in East Albury, Springdale Heights, Lavington and Thurgoona (Table 3). A correlation of the number of a party’s corflutes in a polling booth catchment with the percentage of votes received for that party show no statistical significance for any of the four key parties: Liberals (r = 0.262530807), Milthorpe (r = 0.360746872), Labor (r = −0.374007451) or the Greens (r = 0.454955675).

Broadly speaking, it is not surprising that the presence of corflutes appears, at first sight, to be correlated with the density of population (Figure 7). Yet, at a booth catchment level, the number of corflutes is not correlated with the average population density, nor is it correlated at that level with specific generations (baby boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, Gen Z).

Figure 7.

Distribution of election advertising mapped against population density (based on census mesh blocks [139]) in the area surveyed for this study (see Figure 6 for details). Map faces north.

Table 3.

Absolute number of corflutes per booth catchment observed during the survey. For map codes see Figure 8.

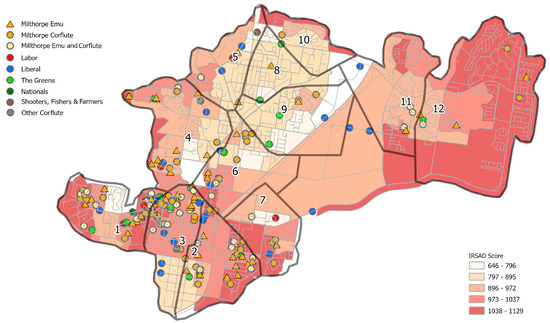

Figure 8.

Distribution of election advertising mapped against the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (ISRAD) score by Statistical Area Level 1 [140], overlain with the boundaries of the booth catchments.

Table 3.

Absolute number of corflutes per booth catchment observed during the survey. For map codes see Figure 8.

| Albury | Lavington | Thurgoona | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booth Name | PS | HS | East | North | West | G’roy | SHts | Hume | PS | East | PS | East | n | % |

| Map Code | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 11 | ||

| Milthorpe (emu) | 14 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 61 | 31.6 | |

| Milthorpe (Corflute) | 10 | 13 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 53 | 27.5 | |||

| Millthorpe (emu & CF) | 6 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 35 | 18.1 | |||

| Liberal | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 10.9 | |||

| Greens | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 7.3 | ||||

| Labor | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2.6 | ||||||||

| Nationals | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | |||||||||||

| Farmers, Fishers & Shooters | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | |||||||||||

| Other (non-party) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| total | 34 | 41 | 7 | 18 | 41 | 22 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 193 | |

A finer-grained analysis at the census mesh block level (Figure 7) showed that the proportion of corflutes per population density quintile is significantly correlated with the frequency of mesh block quintile (r = 0.9864) (Table S5), indicating that the corflute placement follows the general distribution of Albury’s population. When aggregating the corflute data into left-leaning (Labor, Greens) and right leaning (Liberals, National, Farmers, Fishers & Shooters) ‘traditional’ parties, as well the independent (Milthorpe) (Table S6), differences emerge. The corflutes associated with right leaning parties are concentrated in the lower two quintiles of population density. There are significantly more corflutes associated with right leaning parties in the lowest quintile than the frequency of mesh blocks in the quintiles (p = 0.0061), while corflutes associated with the independent are significantly fewer in that quintile (p = 0.0334).

The average age of the entire population in the SA1 cells is 40.17 ± 24.41 years (n = 29,584) with the average age of the population eligible to vote 51.36 ± 18.33 years (n = 21,676). The overall population of voting age in the surveyed area (n = 22,283, Statistical Area Level 1 data) comprises 7.8% Generation Z, 32.0% Generation Y, 33.4% Generation X and 26.8% Baby Boomers (and older). A finer-grained analysis of generational data (only possible at Statistical Area Level 1) (Figures S16–S22) showed that the generations are not evenly distributed in the surveyed area with both Generation Z (Figure S19) and Baby Boomers (Figure S17) showing some clustering. The distribution of population density quintiles of the generation of Baby Boomers and older is skewed as they are clustered in those SA1 cells that contain retirement homes.

Looking at the frequency distribution of quintiles of total the population in the 69 SA1 cells, the majority of the cells belong to the fourth (44.8%) and third quintile (31.3%) (Table S7). Not surprisingly, using this frequency distribution as a base, the overall distribution of corflutes mirrors the distribution of the population. When looking at the generational breakdown, however, differences emerge (Table S7). Corflutes tend to be concentrated in areas with a low density of Baby Boomers r = −0.6018), Generation Y (r = −0.0220) and Generation Z (r = −0.2763), which suggests it is not these generations that reflect the posting of the corflutes. The frequency distribution of Generation X (SA1 ages 46–64) (Table S7), however, correlates very well with the distribution total the population (r = 0.9601)

With six exceptions (of a total of 21), the Liberal Party corflutes were all displayed tied to the poles of traffic signs along the arterial roads of Albury (Figure S20) reflecting party-organizational placement of these with little personal engagement. In contrast, the corflutes of all other candidates were displayed on private property.

Albury has seen period expansion of its urban envelope from the core in the south to the north (Lavington, Springdale Heights, Hamilton Valley), west (West Albury), east (East Albury), and north-east (Thurgoona, Wirlinga) (Figure 5). Correlating the distribution of corflutes with the growth periods of Albury showed that greatest number of corflutes was placed in the oldest (pre-1930s, 13.3%) and older suburbs (1930s, 35.7%), with a further peak in the 1970s (14.8%). There is no significant correlation with the distribution of the overall mesh blocks per period with the actual distribution of the corflutes (Tables S9 and S10).

Figure 8 shows the distribution of corflutes against the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage score (ISRAD) expressed in quintiles. There is no significant correlation between the number of corflutes and the average ISRAD when assessed at the booth catchment at the overall level (r = 0.2346) nor at candidate levels (Ley r = −0.3097; Milthorpe r = 0.3003) (Table 4). A finer-grained analysis at Statistical Area Level 1, however, shows that Statistical Areas with a higher ISRAD score also show a higher number of corflutes. When considering the distribution of corflutes displayed by supporters of the independent candidate, then residents in areas with the highest ISRAD score displayed very significantly more corflutes than residents in areas with the second highest ISRAD score (p = 0.0051), which in turn displayed very significantly more corflutes than residents in areas with the third highest ISRAD score (p = 0.0056). The distribution of corflutes by the other parties showed no significant differences which may be due to the small sample size for each of these. Worth noting is that there are no differences in corflute distribution between the ‘traditional’ parties when the data are concatenated into left-leaning (Labor, Greens) and right leaning (Liberals, National, Farmers, Fishers & Shooters) and the ISRAD score categories are aggregated into ‘low’ (two bottom quintiles) and high (two upper quintiles).

Table 4.

Frequency of corflutes (in %) per Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (ISRAD) quintile based on Statistical Area Level 1 boundaries. FFS—Farmers, Fishers & Shooters.

5. Discussion

While election posters are commonly interpreted as spatial visual communications [115,146,147,148], they exist within the context of the urban space in which they are placed. This space is not neutral, but shaped by power, practice, and ideology [149]. The spatial distribution of election and protest posters mirrors power relations, access to visibility, and contested territories that can be interpreted as a cultural landscape of political power [97,150], race relations [91,92] and community identity [95,96]. From a cultural landscape perspective, the deliberate and strategic placement of election corflutes in prominent positions represents, in visual form, the claiming of territory by the candidate [107]. In a theoretical framing, prime poster locations at busy intersections, commuter corridors, or public squares, are more than neutral display surfaces. Given that visibility is a form of power, such locations represent high-value political real estate, establishing a perception of territoriality [96].

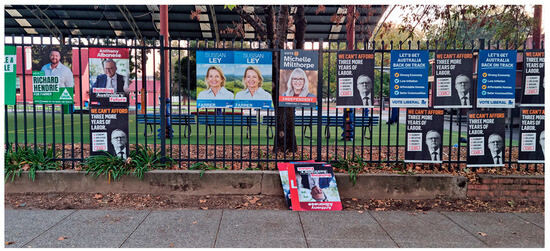

In marginal and thus hotly contested electorates, this territoriality manifests itself in ‘poster wars,’ where mundane surfaces are turned into arenas of contestation and control. These ‘wars’ are characterized by a monopolization and saturation of prime spaces, as well as unauthorized removal (Figure 9 and Figure S13), vandalism and defacement [150,151]. The practice of layering, that is pasting posters on top of those by opposing parties, which had been common in earlier campaigns, has largely ceased with the introduction of the stiff corflutes.

Figure 9.

Election posters at the Albury Public School polling booth. Election day, 3 May 2025, 7 a.m. Note the vandalized poster of the Australian Labor party on the ground.

These traditional poster or corflute wars were absent in Albury during the 2025 Federal election, with the exception of the fences at some polling booths (Figure 9) where proximity to the entrance gate was ‘premium real estate’ (Figure S12). While Sussan Ley as the long-term incumbent could rely on established recognition and a personal vote, [119] the Independent candidate Michelle Milthorpe, without a personal electoral track record and without the backing of the brand recognition afforded by a political party, had established public recognition. Thus, the corflutes of the Liberal party were primarily placed, at random intervals and locations, on the poles of traffic signs on Albury’s arterial roads, signaling a top-down placement approach with limited citizen involvement.

As corflutes provide considerable visual exposure and recognition for candidates that lack established recognition or longer-term exposure in other media [107,115,116,117,146], the Milthorpe campaign relied on sympathizers to display the corflutes on their properties. This strongly signaled grassroots support through individual endorsement and personal engagement, suggesting that residents actively participated in shaping the visual political landscape. The creative and symbolic use of orange corflutes shaped like emus, used even before candidacy was confirmed, illustrates a grassroots and identity-driven strategy distinct from traditional campaign methods. The resonance of the orange emus as both a campaign emblem and a protest symbol suggests a deeper connection of political messaging with local values and dissatisfaction with traditional representation. Much like yarn bombing or Christmas lights, they represent and reflect personal and collective agency, and, collectively, demonstrate community-driven expressions of identity [96]. They not only map a transient landscape of political expression and social affiliation but are also situated within a lineage of bottom-up production of ephemeral cultural landscapes [94].

While the visual ephemeral landscape of an election is legally circumscribed as the time period between the day the election was called (in this case, 28 March 2025) and election day itself (in this case, 3 May 2025) [134], this was not necessarily true in the case discussed here. Under ‘normal’ circumstances, it takes a few days after an election is called to ramp up the production, distribution and placement of corflutes. In consequence, the density and spatial patterning of electoral signs will increase in the first two weeks and plateau towards election day. Normally, election posters that had been placed in public spaces are taken down on election day as soon as the polls have closed or on the day after, because leaving posters hanging for a longer time tends to generate public backlash. Election posters placed on private property are also usually removed on the day of, or the day after the election. Thus, the visual urban landscape undergoes a temporally constrained transformation.

While the established parties (Liberal, Labor, Greens, etc.) followed that pattern, the independent campaign differed in that regard. Established in June 2023 as a grass roots campaign to emulate the success of an Independent candidate in an adjacent electorate [152], the groups selected their candidate in September 2024 [153]. Well before the candidate was selected, the orange emu had been adopted as campaign logo and had begun to appear on people’s fences and walls from April 2024 onwards, as a sign of protest and need for political change. Once the election was called, these were augmented by standard A1 corflutes. This multi-phase approach reflects staged messaging tactics and movement-building prior to electioneering. While all standard A1-sized corflutes promoting the independent candidate have long since been removed, several of the orange emus still persist at the time of writing, 60 days after the polls closed (Figure 10B). The fact that several of these emus still persist well past the election period attests to their dual function as protest symbols as well as election posters. This echoes observations in Queensland where individually designed and executed protect signage persisted for a prolonged period [96]. It is unclear how long these residual emus will persist. Ultimately it depends on the will of their owners continuing to display them and the physical preservation of the emu signage. Given that they are made from corflute material (polypropylene plastic) covered with orange paint, they are prone to an, albeit slow, decay due to exposure to UV radiation once the orange paint starts to break down.

Figure 10.

A corflute and multiple emus promoting the independent candidate, Michelle Milthorpe. Seen in Central Albury. (A) prior to election day, 2 May 2025; (B) persistent presence of the emus, nine weeks after the election, 5 July 2025.

While everybody has their own cultural positioning in terms of spirituality/religion and political leanings, it is a commonly accepted notion for most, but not all members of society, that such polarizing topics best be avoided in ‘polite conversation’ as well as at the workplace [154]. Setting aside issues based protest movements, such as the anti-nuclear debate of the 1970s and 1980s [155,156], only a minority will carry their values ‘on their sleeve’ and express them through buttons, car stickers or postcards [157,158,159,160,161]. On occasion, controversial development proposals can result in protest signage that crosses standard political boundaries [96]. With the exception of a usually uncontestable public expression of national pride in the form of the national flag being flown on private flag poles, people’s political positioning, however, is rarely expressed in the urban landscape. This changes during election times.

Depending on what is (perceived to be) at stake at the election, supporters of political parties will engage in a public display of political protest and allegiance, which shapes public and private spaces materially and symbolically [91,94]. Personal observations in the author’s neighborhood suggest that this public display is not instant/overnight, but grows incrementally during the declared election campaign period, culminating in the last days before election day itself. Gradually the visual appearance of a streetscape is reshaped from politically neutral to engaged by property owners taking a stance and signaling this to all passers-by. While it can be surmised that personal agency and engagement in the political process are the motivating factors, it appears that people are initially hesitant to project their own political opinions in such a public fashion but follow once others have taken the step. Future research into the motivations and timing could prove a rich filed of enquiry at the next state or Federal election.

The interpretation of contemporary urban landscapes is commonly limited to an understanding of broad power relationships that position places of authority (government buildings, religious structures) against places of commerce (shops) and private residences. Visual elements of streetscapes, such as established leafy suburbs and heritage precincts/conservation areas, or modern ostentatious housing contrasted with social housing complexes, signal socio-economic strata within a community. But they do not illuminate the cultural and political positioning of the community let alone in its spatial patterns.

While ephemeral, these temporally constrained political landscapes project individual cultural and political positioning beyond the confines of family and personal acquaintances. At a time when general disengagement with established political parties is on the rise [162] in particular among the youth [163], Independent candidates have gained traction [143,164]. The cultural landscape of election signage reflects this well. The cultural landscape elements generated by established parties are both top-down in nature and overall limited—which may well be a tangible expression of a sentiment that takes the electorate of Farrer for granted. The cultural landscape of independent campaigns is generally characterized by bottom-up active construction and engagement across the community. The abundance of election signage for the Independent candidate, all of which was displayed on private property, reflects this well. When seen in juxtaposition to the election signage displayed by, and for, the established parties, the public expression of support for the Independent candidate visually acts a sign of the public’s political voice, of protest and community power [94,96]. Although ephemeral and transient, election signage generates a culturally influential landscape.

Finally, a major unknown is the future of such ephemeral, political cultural landscapes. Whereas in the past media advertising was limited to free-to-air and commercial television as well as print media, the advent of social media has reshaped the communications landscape [165]. This entails passive media (such as campaign Facebook pages) but also active media in the form of advertisements inserted into people’s personal social media feeds. Facebook advertising has been commonplace since the late 2010s [166,167,168], followed by Instagram [169,170] and most recently TikTok [171,172]. Social media campaigning allows candidates to project both a more detailed, a more nuanced and, significantly, also a more immediate response to election issues as they emerge, providing greater exposure to lesser-known candidates. Location and demographic data of Facebook users allows political parties to target specific demographics in geographically circumscribed locations (state, region) with focused messaging [165,173]. Anecdotally, based on personal observations of the authors, the overall number of election signage posted during Federal elections at arterial roads and public spaces has continually declined over the past decade. Similar decreases have been observed elsewhere [93]. While the overall trend may point downwards, with ongoing supplantation by digital media, the case study discussed in this paper has shown that grassroots mobilization still can generate a tangible, albeit ephemeral, political cultural landscape.

While these digital political cultural landscapes are likewise ephemeral, the individual elements (posts), lack the ontic dimensions of materiality and thus will be difficult to accurately document and collect [5]. Future research should explore the dissonance between traditional tangible cultural political landscapes that can be witnessed by every person in the community and the emerging digital political landscapes that can be witnessed only by the viewer and that may well be highly personalized.

6. Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated that ephemeral cultural landscapes, such as election signage, are not merely passive backdrops to political events but actively shape and reflect political engagement, territorial expression, and community identity. The 2025 Federal election in Albury provided a valuable case study in which the distribution, form, and persistence of campaign materials reflected divergent political strategies, levels of community involvement, and socio-spatial dynamics. The marked contrast between the top-down placement of Liberal Party corflutes on public infrastructure and the grassroots, individually endorsed deployment of independent candidate Michelle Milthorpe’s signage, particularly the symbolic orange emus, highlights differing models of political engagement and visibility.

Significantly, the study reveals that ephemeral landscapes can transcend their designed temporality. The continued presence of the orange emus beyond the legislated campaign period illustrates how visual elements of political communication can acquire extended symbolic lives, becoming enduring features in the socio-political landscape. This challenges conventional understandings of election advertising as temporally bounded and instead frames it as part of a broader continuum of community expression, resistance, and identity formation.

This study expands the concept of cultural landscapes by highlighting the significance of ephemeral political signage as a transient yet meaningful layer of spatial expression. It demonstrates that cultural landscapes are not solely shaped by enduring structures or historic use, but also by short-lived, community-driven interventions that reflect identity, agency, and political sentiment. The research reveals how such ephemeral elements, especially when grassroots in origin, can challenge dominant spatial narratives and contribute to evolving cultural memory. By foregrounding temporality and personal engagement, the study offers a nuanced perspective on how cultural landscapes are continuously produced, negotiated, and contested.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14081610/s1. References [109,133,139,140,174] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.H.R.S.; Methodology: D.H.R.S.; Data collection: D.H.R.S. and D.D.: Formal analysis: D.H.R.S. and D.D.; Writing—original draft preparation: D.H.R.S. and D.D.; Writing—review and editing: D.H.R.S. and D.D.; Visualization: D.H.R.S. and D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data file can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.26189/767de167-7457-4e53-829a-0d59dff4cf9f.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Papayannis, T.; Howard, P. Nature as heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2007, 13, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Akagawa, N. Intangible Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Classifying sound: A tool to enrich intangible heritage management. Acoust. Aust. 2021, 50, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R.; Bond, J. Sensory perception in cultural studies—A review of sensorial and multisensorial heritage. Senses Soc. 2024, 19, 231–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Spennemann, R.J. The New Frontier of Heritage Management: Conceptualizing, Defining and Managing the Heritage of the Digital Age. Heritage, 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre, M. Values and heritage conservation. Herit. Soc. 2013, 6, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredheim, L.H.; Khalaf, M. The significance of values: Heritage value typologies re-examined. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Shifting Baseline Syndrome and Generational Amnesia in Heritage Studies. Heritage 2022, 5, 2007–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Nexus between Cultural Heritage Management and the Mental Health of Urban Communities. Land 2022, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.S.; Messenger, P.M.; Soderland, H.A. Heritage Values in Contemporary Society; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mydland, L.; Grahn, W. Identifying heritage values in local communities. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Futurist rhetoric in U.S. historic preservation: A review of current practice. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2007, 4, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. What actually is a Heritage Conservation Area? A Management Critique based on a Systematic Review of NSW Planning Documents. Heritage 2023, 6, 5270–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Cultural Landscape of the World War II Battlefield of Kiska, Aleutian Islands. Findings of a Cultural Heritage Survey, Carried Out in June 2009; Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 2011; p. 552. [Google Scholar]

- Mitin, I. Constructing urban cultural landscapes & living in the palimpsests: A case of Moscow city (Russia) distant residential areas. Belgeo Rev. Belg. Géogr. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vâlceanu, D.-G.; Kosa, R.-A.; Tamîrjan, D.-G. Urban landscape as palimpsest. Urban. Arhit. Constr. 2014, 5, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J. Indigenous Australian Studies, indigenist standpoint pedagogy, and student resistance. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Global Perspectives on Teacher Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; Volume 257. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, M.F. ‘The breath of the mountain is my heart’: Indigenous cultural landscapes and the politics of heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J. Displacing indigenous cultural landscapes: The naturalistic gaze at Fraser Island World Heritage Area. Geogr. Res. 2010, 48, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolo, D.; Bombino, G.; Meduri, T. Cultural landscape and cultural routes: Infrastructure role and indigenous knowledge for a sustainable development of inland areas. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, P. Naminng No Man’s Land: Postcolonial Toponymies; Palgrave Macmillan Cham: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, P. Proper Names: Differences Between Aboriginal and Colonial Toponymy. In Naming No Man’s Land: Postcolonial Toponymies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tentand, J.; Blair, D. Motivations for naming: The development of a toponymic typology for Australian placenames. Names 2011, 59, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R.; Bond, J. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Heritage Festival Soundscapes—A Critical Review of Literature. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2024, 10, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. To ring or not to ring: What COVID-19 taught us about religious soundscapes in the community. Heritage 2022, 5, 1676–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Conceptualising sound making and sound loss in the urban heritage environment. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2022, 14, 264–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, V. Urban Smellscapes: Understanding and Designing City Smell Environments; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R.; Bond, J. Using destination reviews to explore tourists’ sensory experiences at Christmas markets in Germany and Austria. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 19, 172–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya, J.L.; Mikkan, R.A.; Díaz, M.V. Ephemeral geomorphodiversity: Conceptual debate, valuation, and heritage management. Geomorphology 2025, 471, 109569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford, R. Lake Eyre Basin Rivers: Environmental, Social and Economic Importance; CSIRO Publishing: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Syvitski, J.P.; Gao, S.; Overeem, I.; Kettner, A.J. Socio-economic impacts on flooding: A 4000-year history of the Yellow River, China. Ambio 2012, 41, 682–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Watts, R.J.; Allan, C. Local ecological knowledge and wise use of ephemeral wetlands: The case of the Cowal system, Australia. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 31, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atha, M. Ephemeral landscapes. In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, K. Armidale’s Imported Autumn. Transform. J. Media Cult. 2012, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- McClellan, A. The Cherry Blossom Festival: Sakura Celebration; Bunker Hill Publishing, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brassley, P. On the unrecognized significance of the ephemeral landscape. Landsc. Res. 1998, 23, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palang, H.; Fry, G.; Jauhiainen, J.S.; Jones, M.; Sooväli, H. Landscape and seasonality—Seasonal landscapes. Landsc. Res. 2005, 30, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luick, R. Transhumance in Germany. In Proceedings of the European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism, Bunschoten, The Netherlands, 22–24 October 2008; pp. 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, E. The patterns of transhumance in Europe. Geography 1941, 26, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Jurt, C.; Häberli, I.; Rossier, R. Transhumance farming in Swiss mountains: Adaptation to a changing environment. Mt. Res. Dev. 2015, 35, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, N.R.; Belote, J.; Belote, L. Transhumance in the central Andes. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1976, 66, 377–397. [Google Scholar]

- Baied, C.A. Transhumance and land use in the Northern Patagonian Andes. Mt. Res. Dev. 1989, 9, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, A.J.; Rahman, A.; Miller, D.; Frutos, P.; Gordon, I.J.; Rehman, A.-U.; Baig, A.; Ali, F.; Wright, I.A. Transhumance livestock production in the Northern Areas of Pakistan: Nutritional inputs and productive outputs. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 117, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasaka, S.; Watanabe, T.; Song, F.; Liu, J.; Miyahara, I. Transhumance in the Kyrgyz Pamir, Central Asia. Geogr. Stud. 2014, 88, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntsinger, L.; Forero, L.C.; Sulak, A. Transhumance and pastoralist resilience in the western United States. Pastoralism 2010, 1, 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- White, L. Transhumance in the sheep industry of the Salt Lake Region. Econ. Geogr. 1926, 2, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, P. Transhumance in Tasmania. N. Z. Geogr. 1955, 11, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M. Mapping Australia’s transhumance: Snow lease and stock route maps of NSW. Globe 2004, 56, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Palang, H.; Sooväli, H.; Printsmann, A. Seasonality and landscapes. In Seasonal Landscapes; Palang, H., Printsmann, A., Sooväli, H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Qviström, M.; Saltzman, K. Exploring landscape dynamics at the edge of the city: Spatial plans and everyday places at the inner urban fringe of Malmö, Sweden. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanipour, A. Ephemeral landscape and urban shrinkage. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berressem, H.; Berressem, K.-G. Das Niddatal: Der Umbau einer Landschaft für die Bundesgartenschau; Die Grünen Frankfurt: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2007; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Monclús, J. International exhibitions and urban design paradigms. In Exhibitions and the Development of Modern Planning Culture; Freestone, R., Amati, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, C. The prevalence of storyworlds and thematic landscapes in global theme parks. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2023, 4, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.G.; Riley, R.B. Theme Park Landscapes: Antecedents and Variations; Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Borrie, W.T. Disneyland and Disney World: Constructing the environment, designing the visitor experience. Loisir Soc. 1999, 22, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarman, N.; Stratford, E. Whose rights to the city? Parklets, parking, and university engagement in urban placemaking. Aust. Geogr. 2024, 55, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Q.; Morley, M. The contested value of parklets. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Parker, M. “Endlich wieder Strietzeln”: The restart of German Christmas Markets after the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T.; Millington, S. Illuminations, class identities and the contested landscapes of Christmas. Sociology 2009, 43, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, A.; Pappalepore, I. Festive space and dream worlds: Christmas in London. In Destination London: The Expansion of the Visitor Economy; University of Westminster Press London: London, UK, 2019; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Loschwitz, G. Neue Landschaften-Garten nach dem Uranerzabbau Bundesgartenschau 2007 in Gera und Ronneburg. Gart. Landsch. 2007, 117, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Minner, J.; Abbott, M. How urban spaces remember: Memory and transformation at two Expo sites. Int. Plan. Hist. Soc. Proc. 2018, 18, 1063–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Amero, R.W. The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909–1915. J. San. Diego Hist. 1990, 36, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Best, G. Film-induced tourism: Motivations of visitors to the Hobbiton movie set as featured in the Lord of the Rings. In Proceedings of the International Tourism and Media Conference Proceedings, Melbourne, Australia, 24–26 November 2004; pp. 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Escher, A.; Riempp, E.; Wust, M. Auf den Spuren von Sternenkriegern und Seepiraten. Auswirkungenv on Hollywoodfilmenin Tunesien. Geogr. Rundsch. 2008, 60, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. COVID-19 on the ground: Heritage sites of a pandemic. Heritage 2021, 3, 2140–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Ephemeral COVID-19 Testing Sites in Central Manhattan, New York City (USA); School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences; Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.; Maher, J.; Swapan, M.S.H.; Zaman, A. Street Verge in Transition: A Study of Community Drivers and Local Policy Setting for Urban Greening in Perth, Western Australia. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikadze, V. Ephemeral urban landscapes of guerrilla gardeners: A phenomenological approach. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.G.; Ryan, M.P. Public ceremony in a private culture: Orange county celebrates the fourth of July. In Postsuburban California. The Transformation of Orange County since World War II; Kling, R., Olin, S.C., Poster, M., Eds.; University of California Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Santino, J. Yellow ribbons and seasonal flags: The folk assemblage of war. J. Am. Folk. 1992, 105, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershing, L.; Yocom, M.R. The yellow ribboning of the USA: Contested meanings in the construction of a political symbol. West. Folk. 1996, 55, 41–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santino, J. Halloween in America: Contemporary customs and performances. West. Folk. 1983, 42, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, N. Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, C.M.; Peterson-Lewis, S.; Brown, B.B. Inferences about homeowners’ sociability: Impact of Christmas decorations and other cues. J. Environ. Psychol. 1989, 9, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J. Towards a politics of whimsy: Yarn bombing the city. Area 2015, 47, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahner, L.A.; Varda, S.J. Yarn bombing and the aesthetics of exceptionalism. Commun. Crit./Cult. Stud. 2014, 11, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.D.; O’Driscoll, S. The art/history of resistance: Visual ephemera in public space. Space Cult. 2015, 18, 328–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercleux, A.-L. Graffiti and street art between ephemerality and making visible the culture and heritage in cities: Insight at international level and in Bucharest. Societies 2022, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Vandenhoek, S. You aren’t here: Reimagining the place of graffiti production in heritage studies. Convergence 2015, 21, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K.; Wollan, S.; Woodcock, I. Placing graffiti: Creating and contesting character in inner-city Melbourne. J. Urban Des. 2012, 17, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, G.; Attewell, D.; Rovny, J.; Hooghe, L. The changing political landscape in Europe. In The EU Through Multiple Crises; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 20–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadóttir, J.Ý. How parties respond to protests in a changing political landscape. J. Eur. Public Policy 2025, 32, 2068–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazraee, E. Mapping the political landscape of Persian Twitter: The case of 2013 presidential election. Big Data Soc. 2019, 6, 2053951719835232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, F.; Grossmann, R.; Iwe, K.; Kinkel, H.; Larsen, A.; Lungershausen, U.; Matarese, C.; Meurer, P.; Nelle, O.; Robin, V.; et al. What is Landscape? Towards a Common Concept within an Interdisciplinary Research Environment. eTOPOI 2012, 3, 169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Dellenbaugh-Losse, M. The Cultural Landscape of the Berliner Republic: Undoing the Socialist Past. In Inventing Berlin: Architecture, Politics and Cultural Memory in the New/Old German Capital Post-1989; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 87–133. [Google Scholar]

- Till, K.E. Political landscapes. In A Companion to Cultural Geography; Duncan, J., Johnson, N.C., Schein, R.H., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 347–364. [Google Scholar]

- Zilberg, E. A Troubled Corner: The ruined and rebuilt environment of a Central American barrio In post-Rodney-King-riot Los Angeles. City Soc. 2002, 14, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.B. Restoring Los Angeles’s Landscapes of Resistance. J. Archit. Educ. 2018, 72, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, J.J. Posted: The campaign sign landscape, race, and political participation in Mississippi. J. Cult. Geogr. 2009, 26, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, J.J. Posted redux: Campaign signs, race, and political participation in Mississippi, 2008. Southeast. Geogr. 2011, 51, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makse, T.; Sokhey, A.E. Yard Sign Displays and the Enthusiasm Gap in the 2008 and 2010Elections. PS Political Sci. Politics 2012, 45, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makse, T.; Sokhey, A.E. The displaying of yard signs as a form of political participation. Political Behav. 2014, 36, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, D.H.; Ward, H. Writing on the plywood: Toward an analysis of hurricane graffiti. Coast. Manag. 2007, 36, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerlinck, J.D.; McKinlay, A.; Baldwin, C. Signs in the landscape: Material culture, protest, and place identity in coastal South East Queensland. J. Cult. Geogr. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makse, T.; Minkoff, S.; Sokhey, A. Politics on Display: Yard Signs and the Politicization of Social Spaces; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Australia. Electoral Divisions. Determination of Divisions. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/House_of_Representatives/Powers_practice_and_procedure/Practice7/HTML/Chapter3/Electoral_divisions (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Commonwealth of Australia. Digital Atlas Australia. Federal Electoral Divisions (March 2025). 2025. Available online: https://digital.atlas.gov.au/maps/digitalatlas::federal-electoral-divisions-march-2025 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Bickerstaff, S. Election Systems and Gerrymandering Worldwide; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Durst, N.J. Racial gerrymandering of municipal borders: Direct democracy, participatory democracy, and voting rights in the United States. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 938–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, S. AEC Draws Order of Candidates on Federal Election Ballot Papers Using Blindfolds, Bingo-Like System. 11 April 2025. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-04-11/aec-draws-ballots-federal-election-2025/105165884 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Bahr, J. Trumpet of Patriots Spam Texts: Why Are You Receiving Them, and Are They Legal? 2025. Available online: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/trumpet-of-patriots-texts/vsqj4l75x (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Australian Electoral Commission. Authorising Electoral Communications. 15 April 2025. Available online: https://aec.gov.au/about_aec/Publications/Backgrounders/authorisation.htm (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Australian Electoral Commission. Voter’s Guide: Communication Channels Catalogue. 31 January 2025. Available online: https://www.aec.gov.au/About_AEC/voters-guide-campaign-channels.htm (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Hughes, A. Democracy on Display or a Public Eyesore? The Case for Cracking Down on Election Corflutes. The Conversation. 29 April 2025. Available online: https://theconversation.com/democracy-on-display-or-a-public-eyesore-the-case-for-cracking-down-on-election-corflutes-255219 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Smith, R. Australian Election Posters. In Election Posters Around the Globe: Political Campaigning in the Public Space; Holtz-Bacha, C., Johansson, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsall, T. No Corflutes, No Election? Some Voters Left in the Dark by SA Poster Ban. ABCNews. 26 May 2025. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-05-26/some-voters-left-in-dark-by-sa-poster-ban/105329218 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Greenway, B. Size Matters: Border Election Candidate Asked to Remove Signs After Complaint. The Border Mail. 11 April 2025. Available online: https://www.bordermail.com.au/story/8939846/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Jakimow, T. Discarded Candidates: Waste as Metaphor in Local Government Elections in Australia (and Elsewhere). Cult. Anthropol. 2025, 40, 276–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J. Once the Election Campaign Is Over, can You Recycle Corflutes? ABC News. 23 May 2022. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-05-23/corflute-election-placards-recycle-reuse/101077148 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- McSwiney, J. Social networks and digital organisation: Far right parties at the 2019 Australian federal election. In Understanding Movement Parties Through Their Communication; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, H.; Angus, D.; Bruns, A.; Dehghan, E.; Matich, P.; Tan, J.; Vodden, L. Topic diversity in social media campaigning: A study of the 2022 Australian federal election. Politics Gov. 2024, 12, 8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham, S. The rise of TikTok elections: The Australian Labor Party’s use of TikTok in the 2022 federal election campaigning. Commun. Res. Pract. 2024, 10, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geise, S. Theoretical perspectives on visual political communication through election posters. In Election Posters Around the Globe: Political Campaigning in the Public Space; Holtz-Bacha, C., Johansson, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Breux, S.; Couture, J.; Koop, R. Influences on the Number and Gender of Candidates in Canadian Local Elections. Can. J. Political Sci. 2019, 52, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, D. The importance of being present: Election posters as signals of electoral strength, evidence from France and Belgium. Party Politics 2011, 18, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, E.M. Visual Rhetoric in Election Posters: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis Approach. Koya Univ. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 6, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, C. The Personal Vote in Australian Federal Elections. Political Stud. 2006, 38, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. “No Entry into New South Wales”: COVID-19 and the Historic and Contemporary Trajectories of the Effects of Border Closures on an Australian Cross-Border Community. Land 2021, 10, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Id Profile. Albury City. Service Age Groups. 2025. Available online: https://profile.id.com.au/albury/service-age-groups (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Albury Heritage Review 2022; Historic Themes for Albury (NSW); Albury as a Regional Service Centre and the Principal Heritage Sites associated with this theme; Report to Albury City; School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences; Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]