Recognition of Commons and ICCAs—Territories of Life in Europe: Assessing Twelve Years of Initiatives in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

- There is a close connection between a territory and its community.

- The community has its own functioning governance institution.

- The governance decisions and rules overall positively contribute to the conservation of nature as well as to community livelihoods and wellbeing.

2. Context and Implementation Framework of the Three Initiatives

2.1. The Valdeavellano de Tera (VdT) Declaration

2.1.1. Context

2.1.2. Implementation Framework

2.1.3. The Drafting of the VdT Declaration

2.2. The Creation of the Association “Iniciativa Comunales”

2.2.1. Context

2.2.2. Implementation Framework

2.3. The Peer Review and Support (PRS) Process for Spanish Applications to ICCA Registry

2.3.1. Context

2.3.2. Implementation Framework

2.3.3. The Spanish Peer Review and Support Initiative

3. Methods

4. Results

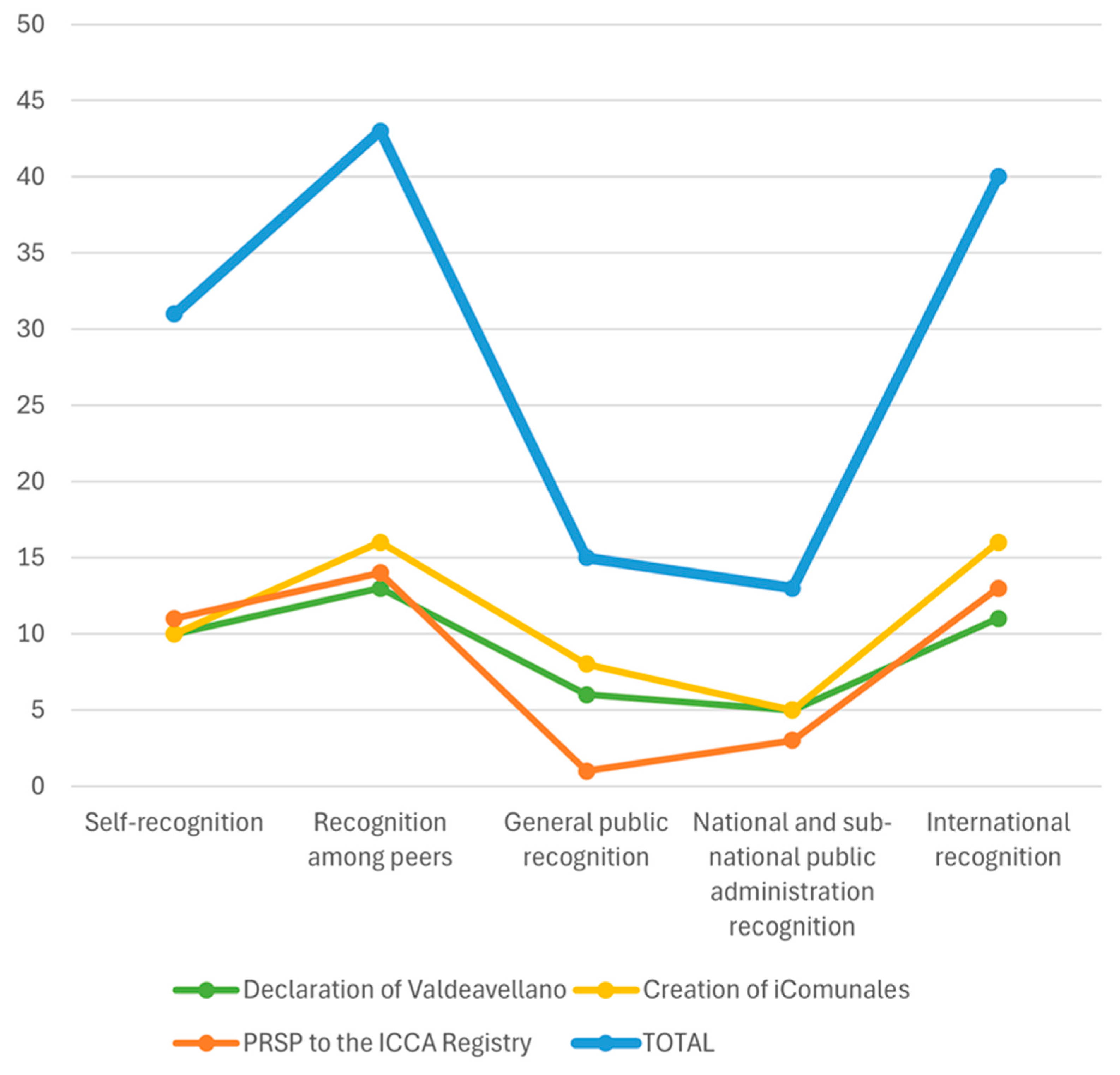

4.1. Overall Initiative Effectiveness

| Recognition Source | Self-Recognition | Recognition Among Peers | General Public Recognition | National and Sub-National Governmental Recognition | International Recognition | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition Initiative | |||||||

| Valdeavellano de Tera Declaration | 10 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 45 | |

| Creation of iComunales | 10 | 16 | 8 | 5 | 16 | 55 | |

| Peer Review and Support process to the ICCA Registry | 11 | 14 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 42 | |

| Total | 31 | 43 | 15 | 13 | 40 | 142 | |

4.2. Source of Recognition Effectiveness

4.3. Type of Community Goals Achieved

| TYPE OF GOAL ACHIEVED | Community Participation | Social Value Recognition | Economic Value Recognition | Environmental Value Recognition | Exchanges and Networking | Added Value Products and Services | Capacity to Defend Against External Threats | External Institutional Support and Resource Mobilization | Influence External Policies | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECOGNITION INITIATIVE | |||||||||||

| Valdeavellano de Tera Declaration | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 45 | |

| Creation of iComunales | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 55 | |

| Peer Review and Support process to the ICCA Registry | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 42 | |

| TOTAL | 17 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 20 | 11 | 14 | 19 | 4 | 142 | |

4.3.1. Enhance Internal Communication and Boost Participation Processes in the Community

4.3.2. Specific Recognition of Community Social/Economic/Environmental Contributions

4.3.3. Exchanges, Networking, Replicability, and Other Sources of Collective Innovation

4.3.4. Provide Added Value to Community Products and Services

4.3.5. Strengthen Capacity to Defend Against External Threats

4.3.6. Increase in External Institutional Support and Resource Mobilization

4.3.7. Influence of External Policies Linked to Commons/Territories of Life

4.4. Lack of Recognition

5. Discussion

5.1. Sources of Recognition

5.2. Types of Goals Achieved

5.3. Key Factors Contributing to the Success of the Three Initiatives

- Bottom-up approach

- Inclusive participatory strategy

- Community empowerment goals

- Self-recognition basis (no “labelling” by outsiders)

- Self-governance guarantees

- Intersectoral approach

- Not alone

5.4. Recommendations for ICCAs—Territories of Life and Commons in Europe

- Conceptualization is key

- 2.

- Recognition is most effective when actively used

- 3.

- What commons have in common

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCs | Local Communities |

| IPs | Indigenous Peoples |

| UNEP-WCMC | UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre |

| WWF | World Wildlife Fund |

| EU | European Union |

| iComunales | Iniciativa Comunales |

| MITECO | Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico |

| DGDR | Dirección General de Desarrollo Rural |

| VdT | Valdeavellano de Tera |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| CSO | Civil Society Organizations |

| ILC | International Land Coalition |

| CENEAM | Centro Nacional de Educación Ambiental |

| PRS | Peer Review and Support |

| FPIC | Free, Prior and Informed Consent |

| EIP-AGRI | European Innovation Partnership for Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability |

| ERDF | European Regional Development Fund |

Appendix A

| SOURCE OF RECOGNITION INVOLVED | Self-Recognition | Recognition Among Peers | General Public Recognition | National and Sub-National Governmental Recognition | International/Global Recognition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TYPE OF GOAL ACHIEVED | ||||||

| Enhance internal communication and boost collective participation processes in the community | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): 96% of the communities went through a self-recognition process with the Declaration. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the involved communities signed | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): 96% of the communities feel identified with other signatories of the Declaration. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the involved communities signed | LOW General public recognition of the value of the internal participation and self-recognition that the Declaration brought has not been relevant | LOW National or sub-national governmental recognition had not a relevant impact on achieving the internal participation and self-recognition that the Declaration brought | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Institutional, conceptual and financial international support for recognition processes of the signatories of the Declaration. Indicator(s): -Valdeavellano meeting -Sense of being part of a global movement for common/ICCA rights -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Support and foundation of iComunales | |

| Specific recognition of the community social contributions | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The community goes (or not) through an internal process of self-recognition on their own social impact. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the involved communities signed | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The communities as signatories self-recognize themselves on their own social impact. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the communities involved signed -Strong support on conceptualization (e.g., social values of commons) | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Declaration contributed to general public recognition on the social values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -Press and blog news at national and regional level -Attendance to public events on the Declaration | LOW We do not have relevant evidence that the specific social value of commons has been recognized by national or sub-national governmental thanks to the Declaration | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the commons’ social values. Indicator(s): -Support with conceptualization (e.g., ICCA concept) -Setting the foundation of iComunales | |

| Specific recognition of the community economic contributions | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The community goes (or not) through an internal process of self-recognition on their own economic impact. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the involved communities signed | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The communities as signatories self-recognize themselves on their own economic impact. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the communities involved signed -Strong support on conceptualization (e.g., economic values of commons) | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Declaration contributed to general public recognition on the economic values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -Press and blog news at national and regional level -Attendance to public events on the Declaration | LOW We do not have relevant evidence that the specific economic value of commons has been recognized by national or sub-national governmental thanks to the Declaration | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the commons’ economic values. Indicator(s): -Support with conceptualization (e.g., ICCA concept) -Setting the foundation of iComunales | |

| Specific recognition of the environmental contributions | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The community goes (or not) through an internal process of self-recognition on their own economic impact. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the involved communities signed | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The communities as signatories self-recognize themselves on their own environmental impact. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the communities involved signed -Strong support on conceptualization (e.g., environmental values of commons) | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Declaration contributed to general public recognition on the environmental values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -Press and blog news at national and regional level -Attendance to public events on the Declaration | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Declaration contributed to national administration recognition on the environmental values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) -Regional support (Navarra) to some events | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the commons’ environmental values. Indicator(s): -Support with conceptualization (e.g., ICCA concept) -Setting the foundation of iComunales | |

| Exchanges, networking, replicability and other sources of collective innovation | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): self-recognition is a prerequisite for equal and effective exchanges and networking at any level. Indicator(s): -High participation rate -96% of the involved communities signed | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The process leading to the Declaration was a major driver of networking and exchanges. Indicator(s): -Creation of iComunales -Nr of members associated (30) | MEDIUM Public recognition brought some degree of exchange and networking from external institutions Indicator(s): -Nr of networking collaborations (5–10) | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The national and sub-national administration recognition and support brought by iComunales contributed to networking and exchanges among commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) -Regional support (Navarra) to some events -MEMOLab Prado (Madrid) -Real Jardín Botánico (Madrid) -Assembly of Pontevedra | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition for the commons networking, exchanges, etc. Indicator(s): -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) | |

| Provide added value to community products and services | MEDIUM The Declaration has been a part of the self-recognition process leading to add value to products and services for some communities. Indicator(s): -Forest products -Information boards and other land signalling | MEDIUM The Declaration has been a part of the association peer-recognition process leading to add value to products and services for some communities. Indicator(s): -iComunales have managed this recognition -Products and services recognized | LOW We do not have evidence that the Declaration has added value to the products and services of the communities involved through the general public recognition | LOW We do not have evidence that the Declaration has brought added value to the products and services of the communities involved trough national or sub-national administrations | MEDIUM the Declaration has been an intermediate step for bringing added value to the products and services of the communities involved trough international support Indicator(s): -Creation of iComunales with international support -ICCA process as final step of early international support | |

| Strengthen capacity to defend against external threats | LOW The Declaration has not been used directly (yet) to defend communities from external threats through self-recognition | MEDIUM The Declaration started the support and solidarity net among peers for helping communities to face each other external threats Indicator(s): -Nr of peer supporting initiatives for facing threats to individual communities | MEDIUM The Declaration started the support and solidarity net among the general public for helping communities to face external threats among the general public Indicator(s): -Nr of external supporting initiatives for facing threats to individual communities | LOW We do not have evidence that the Declaration has strengthen the capacity of the communities involved to defend against external threats | MEDIUM The Declaration started the international support and solidarity net for helping communities to face external threats Indicator(s): -Nr of external supporting initiatives for facing threats to individual communities | |

| Increase in external institutional support and resources mobilization | LOW The Declaration has not been used directly (yet) to achieve external support or for resources mobilization through self-recognition | MEDIUM The Declaration started the institutional support among peers of other institutions Indicator(s): -Nr of institutions supporting the Declaration related initiatives | MEDIUM The Declaration started the institutional support among other general public institutions Indicator(s): -Nr of institutions supporting the Declaration related initiatives | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Declaration contributed to the national and sub-national administration recognition and support on institutional support and resources mobilization. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) -Regional events support (Navarra) -MEMOLab Prado (Madrid) -Real Jardín Botánico (Madrid) -Assembly of Pontevedra | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Declaration contributed to the international resources support and recognition. Indicator(s): -ILC funding Common Lands Network -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | |

| Influence external policies linked to commons/Territories of Life | LOW The Declaration has not been used directly (yet) to influence policies through self-recognition | LOW The Declaration has not been used directly (yet) to influence policies through recognition among peers | LOW The Declaration has not been used directly (yet) to influence policies through recognition among the general public | LOW The Declaration has not been used directly (yet) to influence policies through recognition at national or sub-national level | LOW ACHIEVED GOAL(S): the Declaration itself brought little international recognition to propose changes in international policies | |

| RECOGNITION IMPACT SCORE: | 10 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 11 | |

| OVERALL RECOGNITION IMPACT 0–6: LOW 7–12: MEDIUM 13–18: HIGH | MEDIUM | HIGH | LOW | LOW | MEDIUM | |

| TYPE OF RECOGNITION INVOLVED | Self-Recognition | Recognition Among Peers | General Public Recognition | National and Sub-National Governmental Recognition | International/Global Recognition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TYPE OF GOAL ACHIEVED | ||||||

| Enhance internal communication and boost collective participation processes in the community | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The creation of iComunales brought some degree of self-recognition to the communities. Indicator(s): -Membership process -Mandatory signature of the Declaration (self-recognition) | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Communities feel identified with other members of iComunales and started self-recognition processes leading to join iComunales. Indicator(s): -Events and assembly high participation rate -Numbers and geographical and sectorial representativity of the membership | LOW The value of internal participation and self-recognition related to iComunales has not been relevantly recognized by the general public | LOW National or sub-national governmental recognition had not a relevant impact on achieving the internal participation and self-recognition that the iComunales brought | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Institutional, conceptual and financial international support for recognition processes of the members of iComunales. Indicator(s): -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) | |

| Specific recognition of the community social contributions | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The community as member goes (or not) through an internal process of self-recognition on their own social impact. Indicator(s): -Membership process -Mandatory signature of the Declaration (self-recognition) | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The communities as iComunales members self-recognize through peers their own social impact. Indicator(s): -Events and assembly high participation rate -Numbers and geographical and sectorial representativity of the membership | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales contributed to general public recognition on the social values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -Press and blog news at national and regional level -Attendance to public events organized by iComunales | LOW National or sub-national governmental recognition of iComunales had not a relevant impact on achieving specific recognition of the social contribution of commons | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the commons’ social values. Indicator(s): -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | |

| Specific recognition of the community economic contributions | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The community as member goes (or not) through an internal process of self-recognition on their own economic impact. Indicator(s): -Membership process -Mandatory signature of the Declaration (self-recognition) | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The communities as iComunales members self-recognize through peers their own economic impact. Indicator(s): -Events and assembly high participation rate -Numbers and geographical and sectorial representativity of the membership | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales contributed to general public recognition on the economic values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -Press and blog news at national and regional level -Attendance to public events organized by iComunales | LOW National or sub-national governmental recognition of iComunales had not a relevant impact on achieving specific recognition of the economic contribution of commons | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the commons’ economic values. Indicator(s): -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | |

| Specific recognition of the environmental contributions | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The community as member goes (or not) through an internal process of self-recognition on their own environmental impact. Indicator(s): -Membership process -Mandatory signature of the Declaration (self-recognition) | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The communities as iComunales members self-recognize through peers their own social impact. Indicator(s): -Events and assembly high participation rate -Numbers and geographical and sectorial representativity of the membership | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales contributed to general public recognition on the environmental values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -Press and blog news at national and regional level -Attendance to public events organized by iComunales | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales contributed to national administration recognition on the environmental values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) -Regional support (Navarra) to some events | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the commons’ environmental values. Indicator(s): -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | |

| Exchanges, networking, replicability and other sources of collective innovation | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): self-recognition is a prerequisite for equal and effective exchanges and networking at any level. Indicator(s): -Assembly participation -Events participation | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The membership activity is a major driver of networking and exchanges. Indicator(s): -High participation in events, assemblies -Numbers and geographical and sectorial representativity of the membership | HIGH Public recognition through iComunales brought many exchanges and networking from external institutions Indicator(s): -Nr. of networking collaborations (10–15) | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales achieved support on networking and exchanges among commons in Spain through the national and sub-national administration recognition. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) -Regional support (Navarra) to some events -MEMOLab Prado (Madrid) -Real Jardín Botánico (Madrid) -Assembly of Pontevedra | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition for the commons networking, exchanges, etc. Indicator(s): -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | |

| Provide added value to community products and services | MEDIUM The creation of iComunales has been a part of the self-recognition process leading to add value to products and services for some communities. Indicator(s): -Forest products -Information boards and other land signalling | MEDIUM The creation of iComunales has been a part of the peer-recognition process leading to add value to products and services for some communities. Indicator(s): -Forest products -Information boards and other land signalling | LOW We do not have evidence that iComunales has added value through general public recognition to the products and services of the communities involved | LOW We do not have evidence that national or sub-national administrations have brought added value to the products and services of the communities involved in iComunales | MEDIUM iComunales brought added value to the products and services of some of the communities involved through international support Indicator(s): -Creation of iComunales with international support -ICCA process as final step of early international support | |

| Strengthen capacity to defend against external threats | MEDIUM iComunales has been used directly (yet) to defend communities from external threats through self-recognition Indicator(s): -iComunales supporting campaigns (5-10) | HIGH IComunales, through peer-recognition has been key to defending communities from external threats Indicator(s): -iComunales supporting campaigns (5-10) | HIGH iComunales has been key to the support and solidarity net among the general public for helping communities to face external threats Indicator(s): -Nr of external supporting initiatives for facing threats to individual communities | LOW We do not have evidence that national or sub-national administrations recognition has strengthen the capacity of the communities involved in iComunales to defend against external threats | HIGH iComunales the international support and solidarity net for helping communities to face external threats Indicator(s): -Nr of external supporting initiatives for facing threats to individual communities | |

| Increase in external institutional support and resources mobilization | HIGH The self-recognition of communities through iComunales has been key to achieving external support or for resources mobilization Indicator(s): -ILC funding Common Lands Network -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | HIGH Peer-recognition through iComunales has been key to achieving external support or for resources mobilization Indicator(s): -ILC funding Common Lands Network -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | HIGH iComunales has been key to materializing the institutional support among other general public institutions Indicator(s): -Nr. of institutions supporting iComunales related initiatives | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales contributed to the national and sub-national administration recognition and support to resources mobilization. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) -Regional support (Navarra) to some events -MEMOLab Prado (Madrid) -Real Jardín Botánico (Madrid) -Assembly of Pontevedra | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales contributed to the international resources support and recognition. Indicator(s): -ILC funding Common Lands Network -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | |

| Influence external policies linked to commons/Territories of Life | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales contributed to the international support and recognition bringing changes in international policies, but not in national or subnational policies, through self-recognition. Indicator(s): -EU Common Agricultural Policy -ICCA policy campaigns | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): iComunales contributed to the international support and recognition bringing changes in international policies, but not in national or subnational policies, through peer recognition. Indicator(s): -EU Common Agricultural Policy -ICCA policy campaigns | LOW iComunales has not been used directly (yet) to influence policies through general public recognition | LOW iComunales have not been used directly (yet) to influence policies through national or sub-national recognition | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International recognition through iComunales has served to propose changes in international policies, but not in national or subnational policies. Indicator(s): -EU Common Agricultural Policy -ICCA policy campaigns | |

| RECOGNITION IMPACT SCORE: | 10 | 16 | 8 | 5 | 16 | |

| OVERALL RECOGNITION IMPACT 0–6: LOW 7–12: MEDIUM 13–18: HIGH | MEDIUM | HIGH | LOW | LOW | HIGH | |

| TYPE OF RECOGNITION INVOLVED | Self-Recognition | Recognition Among Peers | General Public Recognition | National and Sub-National Governmental Recognition | International/Global Recognition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TYPE OF GOAL ACHIEVED | ||||||

| Enhance internal communication and boost collective participation processes in the community | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Strong community self-recognition internal and participatory process inherent to the candidacy prerequisite. Indicator(s): -FPIC -Self-evaluation -Documentation-process involving self-recognition by the community | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Strong community peer recognition and internal participatory process inherent to the ICCA Registry candidacy. Indicator(s): -Peer evaluation -Final peer proposal on the candidacy | LOW General public recognition of the value of the internal participation and self-recognition brought by the Registry has not been relevant | LOW National or sub-national governmental recognition had not a relevant impact on achieving the internal participation and self-recognition that the Registry brought | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support was achieved for enhancing participation and self-recognition through the Registry. Indicator(s): -Valdeavellano meeting -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Limited support of UNEP-WCMC | |

| Specific recognition of the community social contributions | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Strong community social self-recognition process inherent to the candidacy. Indicator(s): -FPIC -Self-evaluation -Documentation-process involving social self-recognition by the community | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Strong community peer recognition of social values inherent to the candidacy process (if final peer opinion positive). Indicator(s): -Peer evaluation -Final peer proposal on the candidacy -Registry entry | LOW ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The ICCA Registry did not contribute relevantly to general public recognition on the social values of commons in Spain. | LOW We do not have relevant evidence that the specific social value of commons has been recognized by national or sub-national governmental through the registry | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the ICCAs social values through the ICCA Registry. Indicator(s): -Peer evaluation -Final peer proposal on the candidacy -Registry entry | |

| Specific recognition of the community economic contributions | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Strong community economic self-recognition process inherent to the candidacy. Indicator(s): -FPIC -Self-evaluation -Documentation-process involving economic self-recognition by the community | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Strong community peer recognition of economic values inherent to the candidacy process (if final peer opinion positive). Indicator(s): -Peer evaluation -Final peer proposal on the candidacy -Registry entry | LOW ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The ICCA Registry did not contribute relevantly to general public recognition on the economic values of commons in Spain. | LOW We do not have relevant evidence that the specific economic value of commons has been recognized by national or sub-national governmental through the registry | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the ICCAs economic values through the ICCA Registry. Indicator(s): -Peer evaluation -Final peer proposal on the candidacy -Registry entry | |

| Specific recognition of the environmental contributions | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Strong community environmental self-recognition process inherent to the candidacy. Indicator(s): -FPIC -Self-evaluation -Documentation-process involving environmental self-recognition by the community | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): Strong community peer recognition of environmental values inherent to the candidacy process (if final peer opinion positive). Indicator(s): -Peer evaluation -Final peer proposal on the candidacy -Registry entry | LOW ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Registry has not relevantly helped to general public recognition on the environmental values of commons in Spain. | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Registry contributed to national administration recognition on the environmental values of commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) | HIGH ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International support and recognition of the ICCAs environmental values through the ICCA Registry. Indicator(s): -Peer evaluation -Final peer proposal on the candidacy -Registry entry | |

| Exchanges, networking, replicability and other sources of collective innovation | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): self-recognition has been achieved as prerequisite of the candidacy and involves as result some networking and exchanges as part of the process as well as result of being registered. Indicator(s): -Acceptation of peer evaluation -Networking among registered ICCAs | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The process leading to the registration was a relevant driver of networking and exchanges, but not as much as expected (especially after the registration) Indicator(s): -Registered communities networking -Registered communities exchanges | LOW ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The Registry has not relevantly helped to general public recognition on the environmental values of commons in Spain. | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The national and sub-national administration recognition and support brought by the ICCA Registry contributed to on networking and exchanges among commons in Spain. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) -Regional support (Navarra) to some events -MEMOLab Prado (Madrid) | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International recognition and support brought by the ICCA Registry contributed limitedly to on networking and exchanges among ICCAs in Spain. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) | |

| Provide added value to community products and services | MEDIUM The Registry provides support for self-recognition leading to add value to products and services for some communities. Indicator(s): -Forest products -Information boards and other land signalling | HIGH Peer-recognition is the main key of the ICCA Registry, leading to adding value to products and services for some communities. Indicator(s): -Forest products -Information boards and other land signalling -iComunales label for ICCAs | LOW We do not have evidence that the registration has added value to the products and services of the communities involved through the general public recognition | LOW We do not have evidence that the Registry has brought added value to the products and services offered by the communities through national or sub-national administrations | HIGH International recognition is an important key of the ICCA Registry, leading to adding value to products and services for some communities. Indicator(s): -Forest products -Information boards and other land signaling -Registry entry (e.g., webpage) | |

| Strengthen capacity to defend against external threats | MEDIUM Communities have identified the ICCA Registry and self-recognition as a source of power to defend against external threats Indicator(s): -Community alert calls -Community support calls | MEDIUM The Registry is moderately helping to build a support and solidarity net among peers for helping communities to face each other external threats Indicator(s): -No. of peer supporting initiatives for facing threats to registered communities | MEDIUM The Registry brought some support and solidarity net among the general public for helping communities to face external threats among the general public Indicator(s): -Nr of external supporting initiatives for facing threats to individual communities | LOW We do not have evidence that the Registry has strengthened the capacity of the communities involved to defend against external threats through national or sub-national recognition | MEDIUM The Registry achieved through international recognition some support and solidarity net for helping communities to face external threats Indicator(s): -Nr of external supporting initiatives for facing threats to registered communities | |

| Increase in external institutional support and resources mobilization | LOW Although being part of the Registry have been useful to increase external institutional support and resources mobilization, it was mainly caused by peer and international recognition, not so much because self-recognition | MEDIUM Being part of the Registry trough peer recognition have been useful to increase quite limited external institutional support and resources mobilization | LOW The limited general public recognition on the Registry has helped quite little to achieve institutional support from other institutions | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The national and sub-national administration recognition and support brought by the ICCA Registry contributed moderately to increase institutional support and resources mobilization. Indicator(s): -National permanent seminar (CENEAM) -Regional events support (Navarra) -MEMOLab Prado (Madrid) | MEDIUM ACHIEVED GOAL(S): The international recognition and support brought by the ICCA Registry contributed moderately to increase institutional support and resources mobilization. Indicator(s): -ILC funding Common Lands Network -Coordinator funding support (ICCA Consortium) -Participation in international events (Sidney, etc.) | |

| Influence external policies linked to commons/Territories of Life | LOW The Registry has not been used directly (yet) to influence policies through self-recognition, although it is intended in the medium and long term | MEDIUM The peer support achieved through the Registry has been used directly to influence policies Indicator(s): -No. of policy briefs of the ICCA Consortium and UNEP-WCMC reports addressing policy issues | LOW The limited general public recognition on the Registry has helped quite little to influence external policies | LOW The Registry has not been used directly (yet) to influence policies through recognition at national or sub-national level | LOW ACHIEVED GOAL(S): International recognition through the Registry has served little to propose changes in international policies | |

| RECOGNITION IMPACT SCORE: | 11 | 14 | 1 | 3 | 13 | |

| OVERALL RECOGNITION IMPACT 0–6: LOW 7–12: MEDIUM 13–18: HIGH | MEDIUM | HIGH | LOW | LOW | HIGH | |

References

- Sajeva, G.; Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Niederberger, T. Meanings and More. In Policy Brief of the ICCA Consortium; ICCA Consortium: Grenolier, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ICCA-Briefing-Note-7-Final-for-websites.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- UNEP-WCMC and ICCA Consortium. A Global Spatial Analysis of the Estimated Extent of Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities; Territories of Life: 2021 Report; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Available online: https://report.territoriesoflife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/ICCA-Territories-of-Life-2021-Report-FULL-150dpi-ENG.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- WWF and UNEP-WCMC. The State of Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities’ Lands and Territories: A Technical Review of the State of Indigenous Peoples’ and Local Communities’ Lands, Their Contributions to Global Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Services, the Pressures They Face, and Recommendations for Actions; WWF and UNEP-WCMC: Gland, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://wwflac.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/report_the_state_of_the_indigenous_peoples_and_local_communities_lands_and_territories_1.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Kothari, A.; Corrigan, C.; Jonas, H.; Neumann, A.; Shrumm, H. Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies; CBD Technical Series; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-64-en.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Common Lands Network. Establishing a Common Strategy for the Support and Recognition of Common Governance of Natural Resources. In Proceedings of the Europe and Middle East Workshop on the Commons, Granada, Spain, 23–25 October 2017; Available online: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Europe-and-Middle-East-Workshop-on-the-Commons.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Common Lands Network. Strategy, Governance and Multi-Annual Action Plan; Common Lands Network: Granada, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://www.commonlandsnet.org/media/9 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Iniciativa Comunales. The ICCA Registry and the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA). Permanent Seminars Programme of the National Centre for Environmental Education (CENEAM). In Proceedings of the Capacity Building on Areas and Territories Conserved by Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples (ICCA), Valsaín, Spain, 15–16 March 2018; Available online: https://www.icomunales.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Programme-15-16th-March-Capacity-building-on-ICCAs-and-the-ICCA-Registry.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Couto, S.; Gutiérrez, J.E. Recognition and support of ICCAs in Spain. In Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies; CBD Technical Series; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, ICCA Consortium, Kalpavriksh, and Natural Justice: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/pa/doc/ts64-case-studies/spain-en.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Iniciativa Comunales. The Valdeavellano de Tera Declaration on the Recognition and Defence of the Commons and ICCAs in Spain; Iniciativa Comunales: Valdeavellano de Tera, Spain, 2013; Available online: https://www.icomunales.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/ENG-The-Valdeavellano-de-Tera-Declaration.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Iniciativa Comunales. Agenda de Prioridades de Investigación Sobre Comunales en España; Iniciativa Comunales, Proyecto Comet-LA y Fundación Entretantos: Córdoba, Spain, 2014; Available online: https://www.commonlandsnet.org/media/63 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Bassi, M. Recognition and Support of ICCAs in Italy. In Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies; CBD Technical Series; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, ICCA Consortium, Kalpavriksh, and Natural Justice: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/pa/doc/ts64-case-studies/italy-en.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Beneš, I. Recognition and Support of ICCAs in Croatia. In Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies; CBD Technical Series; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, ICCA Consortium, Kalpavriksh, and Natural Justice: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/pa/doc/ts64-case-studies/croatia-en.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Newing, H. Recognition and Support of ICCAs in England. In Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies; CBD Technical Series; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, ICCA Consortium, Kalpavriksh, and Natural Justice: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/pa/doc/ts64-case-studies/england-en.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Mustonen, T.; Feodoroff, P. Indigenous and Traditional Rewilding in Finland and Sápmi: Enacting the Rights and Governance of North Karelian ICCAs and Skolt Sámi. In Allotment Stories: Indigenous Land Relations under Settler Siege; Justice, D.H., O’Brien, J.M., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen, T.; Scherer, A.; Kelleher, J. We Belong to the Land: Review of Two Northern Rewilding Sites as a Vehicle for Equity in Conservation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, R.; Gama, J. Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (ICCA) in Portugal; MAVA Foundation, the ICCA Consortium, International Land Coalition and Trashumancia y Naturaleza: Coimbra, Portugal, 2021; Available online: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/2021-serra-gama-en-iccas-in-portugal.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Vasile, M. Forest and Pasture Commons in Romania; Territories of Life, Potential ICCAs: Country Report; ICCA Consortium and Romanian Mountain Commons; ICCA Consortium: Grenolier, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/CommonsRomaniaPotentialICCAS2019.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Joye, J.-F. Les “Communaux” au XXIe Siècle: Une Propriété Collective Entre Histoire et Modernité; Centre de recherche en droit Antoine Favre; Presses Universitaires Savoie Mont Blanc: Chambéry, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, T.; Liechti, K.; Stuber, M.; Viallon, F.X.; Wunderli, R. Balancing the Commons in Switzerland: Institutional Transformations and Sustainable Innovations; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meretz, S. Grundrisse einer freien Gesellschaft. In Aufbruch ins Ungewisse (Telepolis): Auf der Suche Nach Alternativen Zur Kapitalistischen Dauerkrise; Konicz, T., Rötzer, F., Eds.; Heise Zeitschriften Verlag: Hannover, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Euler, J. Conceptualizing the commons: Moving beyond the goods-based definition by introducing the social practices of commoning as vital determinant. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G. Territories of Life. Exploring Vitality of Governance for Conserved and Protected Areas; ICCA-GSI with ICCA Consortium, IUCN and UNDP GEF SGP: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://volume.territoriesoflife.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zanjani, L.V.; Govan, H.; Jonas, H.C.; Karfakis, T.; Mwamidi, D.M.; Stewart, J.; Walters, G.; Dominguez, P. Territories of life as key to global environmental sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 63, 101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordăchescu, G. Convivial conservation prospects in Europe—From wilderness protection to reclaiming the commons. Conserv. Soc. 2022, 20, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.M.; Coolsaet, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Loveridge, R.; Gross-Camp, N.D.; Wongbusarakum, S.; Sangha, K.K.; Scherl, L.M.; Phan, H.P.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; et al. The role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomo, P.; Mateja, Š.H.; Francesca, R.L.; Gretchen, W.; Olivier, H.; Karina, L.; Tobias, H.; Mimi, U.; Cristina, D.T.; Jean-François, J.; et al. Territories of commons: A review of common land organizations and institutions in the European Alps. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention 1989. (No.169). International Labour Organisation, 1989. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C169 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerstein, D.; Bloemen, S. How the commons can revitalise Europe. Green Eur. J. 2016, 14, 62–69. Available online: https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/GEJ_Vol14_EN_web.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Bravo, G.; De Moor, T. The commons in Europe: From past to future. Int. J. Commons 2008, 2, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, F.J.B. En Torno al Comunal en España: Una Agenda de Investigación Llena de Retos y Promesas; Sociedad Española de Historia Agraria: Girona, Spain, 2018; No. 1804. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat: Statistics on Common Land. Farm Structure Survey—Common Land. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Farm_structure_survey_%E2%80%93_common_land&oldid=470546#Statistics_on_common_land (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- European Commission. The 2018 Annual Economic Report on the EU Fishing Fleet (STECF 18-07); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, A.; Gatto, P.; Bogataj, N.; Lidestav, G. Forests in common: Learning from diversity of community forest arrangements in Europe. Ambio 2021, 50, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pita, C.; Pascual-Fernández, J.J.; Bavinck, M. Small-scale fisheries in Europe: Challenges and opportunities. In Small-Scale Fisheries in Europe: Status, Resilience and Governance; Pascual-Fernández, J., Pita, C., Bavinck, M., Eds.; MARE Publication Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 23, pp. 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A.; Shrestha Sangat, S.; Golden Kroner, R.E.; Mustonen, T. Extent and diversity of recognized Indigenous and community lands: Cases from Northern and Western Europe. Ambio 2025, 54, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Encuesta sobre Métodos de Producción en las Explotaciones Agrícolas. Año 2009. 30 January 2012. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/np698.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- MITECO. Anuario de Estadística Forestal 2021; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- de España, S. Proposición de Ley de montes de socios. Senado, XV Legislatura, registro general, entrada 1.974, 26 September 2023, 11:24, Preámbulo I, pp. 1. Available online: https://www.senado.es/web/expedientdocblobservlet?legis=15&id=185441 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Grupo dos Comúns. Os Montes Veciñais en Man Común: O Patrimonio Silente. Natureza, Economía, Identidade e Democracia na Galicia Rural; Xerais: Vigo, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Montes Veciñais en Man Común, Oficina Virtual do Medio Natural, Xunta de Galicia. Available online: https://ovmediorural.xunta.gal/gl/consultas-publicas/montes-vecinais-en-man-comun (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- MITECO (Spanish Government, Madrid, Spain). Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge. Personal communication, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- MITECO. Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge, Spanish Government. In Inventario Español del Patrimonio Natural y de la Biodiversidad; MITECO: Madrid, Spain, 2025; Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/temas/inventarios-nacionales/inventario-espanol-patrimonio-natural-biodiv.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Vallejo, R. Tercer Inventario Forestal Nacional. Occurrence dataset. Version 1.7. [CrossRef]

- Polanco, J.; Ramos, J.; García, J.; Julián, J.M.; Martín, F.J. LIFE+ COMFOREST. Rev. For. 2019, 73, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Franquesa, R. Fishermen guilds in Spain (Cofradias): Economic role and structural changes. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Biennial Conference of the International Institute of Fisheries Economics & Trade, Tokyo, Japan, 20–30 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- DGDR. Plan Nacional de Regadíos: Horizonte 2008; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (MAPA): Madrid, Spain, 2001; Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/desarrollo-rural/temas/gestion-sostenible-regadios/plan-nacional-regadios/texto-completo/#prettyPhoto (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Martín-Civantos, J.M.; Toscano, M.; García, M.T.B.; Jiménez, E.C. Un mapa colaborativo para documentar y difundir los sistemas de regadíos históricos de Granada y Almería. In PH: Boletín del Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico; Junta De Andalucia: Sevilla, Spain, 2022; Volume 30, pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Una Comunidad de Montes Vence al Celta de Vigo y frena la Construcción de un Centro Comercial y un Estadio. Available online: https://www.elsaltodiario.com/galicia/una-comunidad-montes-vence-al-celta-vigo-paraliza-construccion-un-centro-comercial (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Comuneiros de Covelo Rexeitan a Construción do Parque Eólico da Telleira. Available online: https://www.nosdiario.gal/articulo/social/sabado-comuneiros-covelo-rexeitan-construcion-do-parque-eolico-da-telleira/20211231160754134952.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Honneth, A. The I in We: Studies in the Theory of Recognition; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guibrunet, L.; Gerritsen, P.R.W.; Sierra-Huelsz, J.A.; Flores-Díaz, A.C.; García-Frapolli, E.; García-Serrano, E.; García-Serrano, E.; Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P. Beyond participation: How to achieve the recognition of local communities’ value-systems in conservation? Some insights from Mexico. People Nat. 2021, 3, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition, and participation. In Geographic Thought; Henderson, G., Waterstone, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, G.M.; Ece, M. Getting ready for REDD+: Recognition and donor-country project development dynamics in Central Africa. Conserv. Soc. 2017, 15, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emcke, C. Between Choice and Coercion: Identities, Injuries, and Different Forms of Recognition. Constellations 2002, 7, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farvar, M.T.; Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Campese, J.; Jaeger, T.; Jonas, H.; Stevens, S. Whose ‘Inclusive Conservation’? Policy Brief of the ICCA Consortium No. 5; The ICCA Consortium and Cenesta: Tehran, Iran, 2018; Available online: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Consortium-Policy-Brief-no-5-Whose-inclusive-conservation.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Thomassen, L. (Not) Just a piece of cloth: Begum, recognition and the politics of representation. Political Theory 2011, 39, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreckenberg, K.; Franks, P.; Martin, A.; Lang, B. Unpacking equity for protected area conservation. Parks 2016, 22, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Coolsaet, B.; Corbera, E.; Dawson, N.M.; Fraser, J.A.; Lehmann, I.; Rodriguez, I. Justice and conservation: The need to incorporate recognition. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 197, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolsaet, B.; Néron, P.Y. Recognition and environmental justice. In Environmental Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Declaration of Valdeavellano de Tera. Available online: https://www.icomunales.org/que_queremos/#valdeavellano (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Public presentation of the Declaration of VdT. Available online: https://rjb.csic.es/manana-se-presenta-en-el-real-jardin-botanico-csic-la-declaracion-de-valdeavellano-de-tera/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Public Events of the Association iComunales. Available online: https://www.icomunales.org/que_hacemos/eventos/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Public Events of the Association iComunales in collaboration with the ICCA Consortium. Available online: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/category/world-en/europe-russia-en/spain-en/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Permanent Seminar on Communal Conservation. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/ceneam/grupos-de-trabajo-y-seminarios/conservacion-comunal-en-espana-icca.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Common Lands Network Digital Platform. Available online: https://www.commonlandsnet.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Corrigan, C.; Granziera, A. A Handbook for the Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas Registry; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/handbook-indigenous-and-community-conserved-areas-registry-0 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Dudley, N.; Jaeger, T.; Lassen, B.; Neema Pathak, N.P.; Phillips, A.; Sandwith, T. Governance of protected areas: From understanding to action. In IUCN Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/29138 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Turner, L.A. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, C.; Gibbes, C. 4. Mixed Methods in Tension: Lessons for and from the Research Process. In Critical Physical Geography: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Nature, Power and Politics, 1st ed.; Lave, R., Lane, S., Eds.; Open Book Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2025; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, C. Conceptualizing from the Inside: Advantages, Complications, and Demands on Insider Positionality. Qual. Rep. 2015, 13, 474–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newing, H.; Eagle, C.; Puri, R.K.; Watson, C.W. Conducting Research in Conservation; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; Volume 775. [Google Scholar]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A Hands-on Guide to Doing Content Analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakis, A.; Hilliam, R.; Stoneley, H.; Townend, M. Quantitative analysis of qualitative information from interviews: A systematic literature review. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2014, 8, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couso, o Monte Que Pasou de Escombreira a Referente Ecolóxico. Available online: https://www.campogalego.gal/couso-o-monte-que-pasou-de-escombreira-referente-ecoloxico/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Use of the ICCA Logo by Their Custodian Communities. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/DGKx0z_s3cg/?utm_source=ig_web_button_share_sheet&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA== (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Plataforma Pola Defensa dos Montes Veciñais en Mano Común. Available online: https://cdmvdc.wixsite.com/plataformaccmm (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Jornadas Digitales Sobre la Recuperación y la Gobernanza de los Montes en Mano Común. Available online: https://elcampodeasturias.es/2021/06/22/jornadas-digitales-sobre-la-recuperacion-y-la-gobernanza-de-los-montes-en-mano-comun/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Las Entidades Locales Reclaman el Reconocimiento de Los Montes Vecinales en Mano Común a Través de Mujeres. Available online: https://elcampodeasturias.es/2022/03/22/las-entidades-locales-reclaman-el-reconocimiento-de-los-montes-vecinales-en-mano-comun-a-traves-de-mujeres/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Miniguía Para Personas o Colectivos Afectados por Instalaciones Fotovoltaicas. Available online: https://www.commonlandsnet.org/media/52 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Salguero, C. Commons and the European Union Common Agricultural Policy (CAP); Trashumancia y Naturaleza: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.icomunales.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/TyN-2019-Commons-and-the-CAP.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- LIFE COMFOREST. Identification, Monitoring and Sustainable Management of Communal Forests in EXTREMADURA. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/project/LIFE12-ENV-ES-000148/identification-monitoring-and-sustainable-management-of-communal-forests-in-extremadura (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Faulkner, A.; Basset, T. A helping hand: Taking peer support into the 21st century. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2012, 16, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, R.A.H.; Agyapong, V.I. Peer support in mental health: Literature review. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e15572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, N.; Bradfield, M.; Cross, D. Communities of Evaluation. In Cultures of Resilience; Hato Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 44–47. Available online: https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/8201/2/CoR-Booklet-forHomePrinting.pdf#page=46 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- CBD. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, CBD/COP/15/4. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-final-text-kunming-montreal-gbf-221222 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- White, B.; Standaert, L. The Commons, a quiet revolution. Green Eur. J. 2016, 14, 1–3. Available online: https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/GEJ_Vol14_EN_web.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Agrawal, A.; Erbaugh, J.; Pradhan, N. The commons. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2023, 48, 531–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamayor-Tomas, S.; García-López, G.A. Commons movements: Old and new trends in rural and urban contexts. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymas, O.; Walters, G. Les communs Fonciers Peuvent Servir de Modèle Pour Relever les Défis Ecologiques. Le Monde, 28 August 2021. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2021/08/28/les-communs-fonciers-peuvent-servir-de-modele-pour-relever-les-defis-ecologiques_6092597_3232.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Louvin, R.; Alessi, N.P. Un nouveau souffle pour les consorteries de la Vallée d’Aoste. J. Alp. Res. Rev. De Géographie Alp. 2021, 109-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, M. Territories of Life in Europe. Towards a Classification of the Rural Commons for Biodiversity Conservation. Antropol. Pubblica 2022, 8, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C. Rethinking communities, land and governance: Land reform in Scotland and the community ownership model. Plan. Theory Pract. 2023, 24, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Hollingdale, J.; Walters, G.; Metzger, M.J.; Ghazoul, J. In Danger of Co-Option: Examining How Austerity and Central Control Shape Community Woodlands in Scotland. Geoforum 2023, 142, 103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J.D.; Lieberherr, E.; Knoepfel, P. Governing contemporary commons: The Institutional Resource Regime in dialogue with other policy frameworks. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M. (ICCA of Teis, Vigo, Spain). Personal communication, 2025.

- Godoy-Sepúlveda, F.; Sanosa-Cols, P.; Andonegui, I.; Chica, L.y.P.; Domínguez. Problemáticas y vías de apoyo a los comunales en España. Informe del Grupo de Trabajo en ICCAs y de Investigación de iComunales. Iniciativa Comunales: Pontevedra, Spain, 2022; Unpublished report, to be submitted. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP-WCMC. ICCA Peer-review Networks: A Guide on How to Set Up an ICCA Peer-Support and Peer-Review Process. UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, manuscript in preparation. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cerra, M. El Registro Global de los territorios y áreas conservadas por Pueblos Indígenas y comunidades locales (TICCA) y el proceso de articulación Nacional de reconocimiento y revisión mutuo adaptado al contexto: Los casos de España y Filipinas. Máster En Espacios Naturales Protegidos Fundación Interuniversitaria Fernando González Bernáldez para el estudio y la conservación de los Espacios Naturales. Trabajo Final De Máster, Alcalá de Henares: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Unpublished work, to be submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Campese, J.; Niederberger, T. Strengthening Your Territory of Life: Guidance from Communities for Communities; The ICCA Consortium: Grenolier, Swizerland, 2021; Available online: https://ssprocess.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/ICCA_Territories-of-Life_2023-ENG.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Couto, S.; Walters, G.; Martín Civantos, J.M. Recognition of Commons and ICCAs—Territories of Life in Europe: Assessing Twelve Years of Initiatives in Spain. Land 2025, 14, 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081623

Couto S, Walters G, Martín Civantos JM. Recognition of Commons and ICCAs—Territories of Life in Europe: Assessing Twelve Years of Initiatives in Spain. Land. 2025; 14(8):1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081623

Chicago/Turabian StyleCouto, Sergio, Gretchen Walters, and José María Martín Civantos. 2025. "Recognition of Commons and ICCAs—Territories of Life in Europe: Assessing Twelve Years of Initiatives in Spain" Land 14, no. 8: 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081623

APA StyleCouto, S., Walters, G., & Martín Civantos, J. M. (2025). Recognition of Commons and ICCAs—Territories of Life in Europe: Assessing Twelve Years of Initiatives in Spain. Land, 14(8), 1623. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081623