Abstract

To enhance the utilization efficiency of existing construction land and promote integrated urban–rural development, China’s government has implemented the “Linkage” Policy, which has commodified land development rights and reallocated urban–rural development potential. In recent years, a growing number of studies have examined the diversified governance structures of “Linkage” projects, which has deepened our understanding of China’s project-based rural land governance. However, most studies have focused primarily on governance performance while neglecting the comparative advantages of different governance structures in improving process efficiency, particularly within the same local institutional environment. To fill this gap, this study first conceptualizes the transactions and sub-transactions in the Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) and then systematically assesses the associated organizational risks. Drawing on Transaction Cost Theory, this paper analyzes how governance diversity mitigates risks and optimizes efficiency. Empirically, this research employs a comparative case study approach, examining three representative governance modes using data triangulation to ensure robust findings. Finally, the theoretical and empirical analyses yield three key findings regarding China’s TDR system: First, given the inherent complexity and substantial financial investment required, the efficient implementation of China’s rural land development projects necessitates leveraging complementary stakeholder strengths. Second, transaction risks constitute the primary source of transaction costs and the central concern of all governance structures. Third, beyond governance structure selection, local institutional innovations and collective action mechanisms significantly enhance governance efficiency.

1. Introduction

In recent years, many developing countries have experienced accelerated urban sprawl, which has resulted in some negative externalities, such as a reduction in cultivated land [1,2,3], the unbalanced and disordered development of urban–rural space [4,5], eco-environmental problems [6,7], and income segregation [8]. To address these issues, China introduced a series of policies to promote more inclusive urbanization and more integrated urban–rural development, which have made remarkable achievements and attracted international attention. Among them, the Linkage (Zengjian Guagou) Policy has played an indispensable role in improving the utilization efficiency of existing construction land to “produce” urban space, as well as reallocating land wealth to promote rural vitalization [9].

According to the “Linkage” Policy, cultivated land is allowed to be occupied by urban construction only if rural construction land can be consolidated to generate the same amount of cultivated land to offset it. Thus, some scholars point out that this policy has de facto separated and commodified the development rights of China’s rural land and built another bridge to connect urban–rural land markets besides land acquisition [9,10]. However, due to China’s centralized land governance and top-down land quota system, the market mechanism of this Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) is not as straightforward as that in other countries. Some researchers contend that these projects essentially replicate conventional land expropriation models and that the villagers remain excluded from meaningful participation in land rights commodification [9,11]. Meanwhile, some other scholars believe that market-invested mode [12] and self-organized mode [13] have emerged in China’s TDR practice, which marks a crucial milestone in its rural land reform. To respond to this controversy, two important questions arise as to why the three TDR models (i.e., the conventional government-dominated model, market-invested model, and self-organized model) emerge under China’s centralized land governance system and how they fit to various conditions to improve process efficiency.

To answer these two questions, this research reviews relevant empirical and theoretical studies in Section 2 from the theoretical perspective of Transaction Cost Theory; analyzes the transaction risks in China’s TDR projects and the advantages of the three TDR models in risk control in Section 3; delineates and compares the governance mechanisms of the three TDR models based on Chengdu’s TDR practice in Section 4; and finally discusses the significance of institutional diversity in dealing with complex transactions (just as in China’s TDR projects) and provides policy references to balance urban–rural development in Section 5.

2. Literature Review

How to solve the negative externalities of urban sprawl and promote balanced urban and rural development have become tough issues for most developing countries. On the one hand, rapid urban construction inevitably occupies a lot of cultivated land [5]; on the other hand, formal land markets are less developed in rural areas, resulting in lower land values, insecure property rights, and heightened inequality [14,15]. Given these conditions, some developed countries have promoted urban–rural collaboration through resource flow mechanisms [6]. In this context, China’s institutional “Linkage” Policy offers a potentially valuable reference.

2.1. A Theoretical Review: What Transactions Have Been Conducted Under the Linkage Policy?

As a quota-based mechanism for reallocating land development potential, China’s “Linkage” Policy is frequently compared with the TDR program in the United States (USA). This comparison raises a fundamental question: what specific property rights are being transferred through these programs? In addressing externality issues, Coasean bargaining typically involves compensating either affected parties for negative externalities or owners for constrained property rights realization, thereby internalizing externalities [16]. When conceptualized as a transaction, the limited ownership rights being transferred constitute the nature of the development rights.

The conceptual foundation for modern TDR systems traces back to the United Kingdom’s 1947 Urban-Rural Planning Act, which nationalized development rights under the Town and Country Planning system. This pioneering legislation established development rights as legally recognized claims to modify land use patterns or intensify existing development [17,18]. The United States implemented its market-based TDR approach in the late 1960s, creating a formal framework with four essential components: clearly designated sending and receiving areas, quantitatively defined development rights, established transfer procedures, and robust compliance mechanisms [19]. These international models demonstrate how development rights can be operationalized as market instruments while serving planning objectives.

China’s “Linkage” Policy shares fundamental characteristics with international TDR programs as a constrained tradable quota system, yet it exhibits distinct institutional features. Both systems aim to internalize development externalities through market mechanisms [16], but they differ significantly in their governance structures, legal definitions of rights, market liquidity, and stakeholder participation patterns (Table 1) [20,21]. The Chinese model reflects Demsetz’s hypothesis about the emergence of new property rights when social benefits outweigh institutional costs [22], which evolved as de facto property rights separated from collective land ownership through national policy interventions. This institutional innovation parallels other Chinese land rights innovations, including contractual management rights for cultivated land [23] and rural homestead use rights [24].

Table 1.

Comparison between TDR in the USA and Linkage in China.

This paper argues that, while international TDR programs typically emerge within established market systems with strong property rights protections, China’s “Linkage” Policy represents an innovative adaptation to its unique land governance framework. Moreover, China’s TDR program demonstrates how de facto property rights can become commodified through policy interventions, creating new market mechanisms within a predominantly state-led governance system.

2.2. An Empirical Review: What Has the “Linkage” Policy Brought to the Rural Sector?

Essentially, the “Linkage” Policy is designed to preserve cultivated land and promote balanced urban–rural development by encouraging land consolidation in rural areas. Amidst the global phenomenon of rural decline, land consolidation has emerged as a critical policy instrument imbued with multidimensional significance, particularly for fostering urban–rural integration and advancing regional sustainability [25,26]. While conceptualizations of "land consolidation" may vary cross-nationally, its core function persists: the systematic reorganization and optimization of land resources to simultaneously elevate land productivity, rehabilitate ecological systems, and augment rural livelihoods [27]. During this process, community intervention and collective actions become major concerns in institutional design and governance choice [28].

Generally speaking, China’s TDR program is a land use mechanism designed to balance urban expansion, rural revitalization, and ecological conservation. On the one hand, it addresses the mismatch between construction land density and population density across urban and rural areas. On the other hand, population density serves as a critical factor in implementation, influencing the demand for development rights, land value, and overall policy effectiveness.

However, its actual impact on rural development in China remains contentious. On the one hand, this policy has distributed more land revenues to the rural sector to improve living conditions and upgrade infrastructure, especially in deep rural areas [29]. On the other hand, what is occupied for urban construction is usually fertile agricultural land in the suburbs, while “Linkage” projects can only “produce” arid land in remote rural areas, which may not be suitable for grain cultivation [23]. Moreover, the encroachment on villagers’ interests has become another Gordian node in the implementation of “Linkage” projects [30]. In the past two decades, China’s central government is believed to have adopted a project-based system to govern land resources, which leaves some authority of project implementation to local governments and triggers institutional diversity in TDR practice [31], such as the Zhejiang Model [11], Chengdu Model [12], and Chongqing Model [32]. According to the existing literature, the governance structures of “Linkage” projects can be classified into the government-dominated structure, market-invested structure, and self-organized structure according to various dominant players [33,34]. Furthermore, governance arrangements have been regarded as the determining factor of the performance and efficiency of TDR projects [19].

Among the existing literature, only a few scholars have discussed the necessity and applicability conditions of various TDR models [35,36]. However, extant literature has predominantly examined the specific operational approach in a province/municipality without providing (1) a micro-level comparative analysis within homogeneous institutional environments or (2) a systematic explanation of how institutional diversity enhances governance process efficiency.

2.3. A Theoretical Perspective: How to Govern the Transfer of Development Rights?

New Institutional Economics offers both micro-analytic and macro-analytic frameworks for institutional examination, which encompasses not only institutional arrangements (concerning governance structures and transaction costs) but also the institutional environment (incorporating property rights and institutional change) [37]. Coase [16] posits that, with well-defined property rights and zero transaction costs, market mechanisms should be the best choice to resolve externality problems. However, given that these assumptions rarely hold in reality, all viable governance structures—including markets, hybrids, and hierarchies (firms and bureaucracies)—are inherently imperfect. Each structure may be well-adapted to specific transactions while performing poorly in others, which necessitates a comparative assessment of their respective strengths and weaknesses [38].

According to Transaction Cost Economics (TCE), the choice among alternative organizational arrangements is based on a comparison of the transaction costs under each institutional arrangement [39]. Owing to information asymmetry and opportunism, transaction costs will merge in the process of owning and using resources under a specific governance structure, including searching and information costs, negotiation and decision costs, and policing and enforcement costs [40,41]. However, the original theory does not give a clear description about the alignment mechanism between transactions and governance structures.

The distinction between private and public sector governance structures arises from their differing property rights regimes and objectives. Traditional discussions framed governance choices as a binary selection between market mechanisms and government regulation. However, recent scholarship has moved beyond this dichotomy, emphasizing more complex, hybrid governance arrangements. Ostrom’s (1990, 2005) work on common-pool resources, for instance, demonstrates the viability of self-governing systems and advocates for nested, polycentric governance in large-scale resource management [42,43,44]. Similarly, public–private–civil partnerships [45,46] and the role of social capital have gained recognition as critical factors in institutional effectiveness [47,48].

The intricate relationship between individual behaviors and collective interests presents significant challenges for public sector governance. Olson’s (1965) foundational analysis of collective action identifies the persistent “free rider problem,” where rational, self-interested individuals may not voluntarily contribute to group interests without appropriate incentives or coercive mechanisms [49]. This theoretical insight explains the inherent difficulties in organizing collective action, particularly in maintaining balanced benefit–cost distributions among participants and accurately measuring individual contributions. Specific to the context of land resource management, these challenges become particularly salient. The growing emphasis on participatory approaches in global land consolidation efforts reflects the increasing recognition of stakeholder engagement as a critical success factor [50]. Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that local involvement significantly influences the outcomes of rural land development projects [51], with numerous case studies further examining the dynamics of collective action in land adjustment processes [52,53,54].

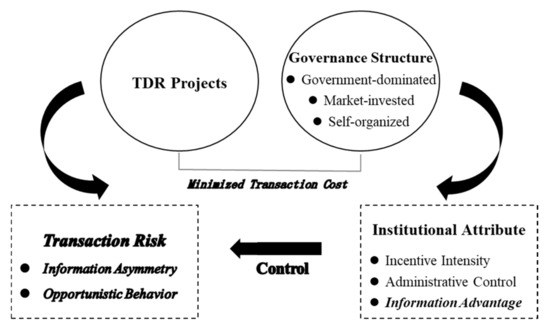

To address these theoretical and empirical gaps, this study develops an analytical framework that reconceptualizes China’s TDR program as a complex transaction spanning both public and private property rights domains. Building on the foundational TCE hypothesis, we propose three substantive modifications to the original framework. First, this paper establishes “transaction risks” as a core analytical dimension, conceptualizing it as serving dual theoretical functions: (1) as a primary generator of transaction costs and (2) as a critical bridge mediating the relationship between transaction attributes and institutional arrangements. This innovation directly responds to Williamson’s [38] call for a more nuanced examination of the differential factors that distinguish optimal governance structures in complex institutional environments. Second, this paper evaluates governance structures through their relative capacities to manage transaction risks, focusing on three key institutional attributes: (1) incentive intensity, which motivates participation and ensures compliance; (2) administrative control, which facilitates rule enforcement and coordination; and (3) information advantages, which reduce asymmetries and improve decision-making quality. Third, we shift the unit of analysis to the collective level, enabling an examination of internal dynamics, including individual participation patterns and information asymmetries, both within collectives and in their external interactions. This approach builds on Ostrom’s [38] insights while addressing the specific challenges identified in China’s rural land governance context.

The resulting framework (illustrated in Figure 1) provides a robust analytical tool for examining the complex and diversified institutional arrangements in China’s TDR program, offering both theoretical insights for institutional scholarship and practical guidance for policy design.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of comparative institutional analysis.

3. Comparative Institutional Analysis of China’s TDR Program

3.1. Transaction Process of TDR Projects

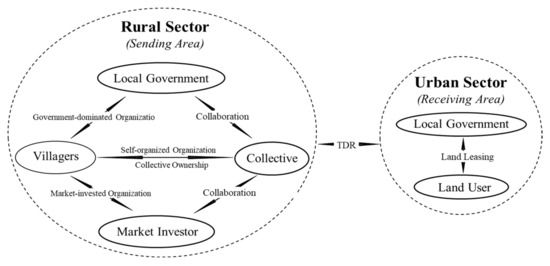

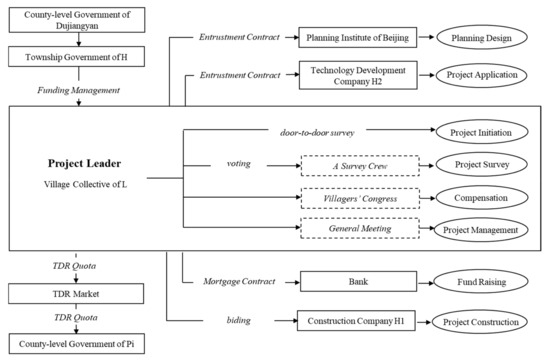

From the perspective of Transaction Cost Economics, the centrality and basic unit of an institutional analysis is market transactions. In this study, the “Linkage” project is analyzed as a special type of TDR program under China’s institutional environment, and the three TDR models result from competition among the local government, market investor, and village collective for the project profits (Figure 2). However, TDR is an extremely complex transaction, especially under China’s dual land system.

Figure 2.

The operational mechanism of China’s TDR projects.

On the one hand, China’s TDR program represents a multifaceted institutional mechanism that integrates three fundamental processes simultaneously. First, it involves the physical transformation of land resources through reclamation and development activities. Second, it requires complex property rights transfers across different ownership regimes. Third, it facilitates substantial resource redistribution between rural and urban sectors. This tripartite nature makes the program particularly complex in the Chinese context, where it must additionally reconcile the central government’s policy objectives with the local governments’ entrepreneurial implementation approaches and the bounded rational behaviors of various stakeholders.

On the other hand, the implementation of TDR programs in China faces distinctive institutional barriers. First, ambiguous collective land ownership creates fundamental uncertainties in property rights delineation. Second, the government’s dominant role in urban land leasing establishes an asymmetric market structure. These conditions necessitate property rights transfers across four distinct entities: private owners, collective owners, state entities, and market users. These institutional factors result in the complexity of the TDR transaction in the Chinese context, significantly influencing the organization and implementation of TDR projects [10]. Thus, a key question can be answered first: why do China’s TDR projects face high transaction costs?

A transaction occurs when goods or services are transferred across technologically separable interfaces [39]. TDR programs integrate physical transformations, property rights transfers, resource reallocations, policy-guided interventions, and market operational mechanisms. Specifically, these programs facilitate the transfer of several land property rights, including homestead use rights from households to village collectives, land development rights from collectives to project investors, and development rights from investors to urban land users.

In this regard, the transaction objective is not only the transfer of the “Linkage” quota but also the aggregation of a series of secondary transactions. Different from most other land transactions, TDR projects can be classified into two stages: the “production” of land development rights first and then the quota transfer from the rural sector (sending area) to the urban area (receiving area). More specifically, there are five steps in the “production” stage: the designation of a “sending area,” project initiation, planning design and preparation, reclamation and new construction, and development rights acquisition and assembly. In each stage, there are several sub-transactions to be conducted between various stakeholders, either to transfer property rights or to achieve agreements. Table 2 shows the sub-transactions that should be conducted in each step, as well as the major activities.

Table 2.

Transaction process and sub-transactions in TDR projects.

3.2. Transaction Risks in TDR Projects

The institutional design of the self-organized model reflects an alternative to both hierarchical government control and market-based approaches. To examine its unique advantages and limitations in specific implementation contexts, this study adds “transaction risks” as a new dimension in the original comparative institutional analysis framework. First of all, this paper examines the critical distinctions between risk, uncertainty, and transaction costs within China’s TDR program, aiming to contribute to broader theoretical debates in TCE. The analysis demonstrates how these concepts manifest differently across various governance structures and project phases while maintaining clear conceptual boundaries between measurable risks and true uncertainties. This research builds upon three fundamental theoretical pillars. First, it adopts Cheung’s (1969) and O’Brien et al.’s (2020) conceptualization of risks as primary drivers of transaction costs, which emerge through information gathering, contractual negotiations, and enforcement activities [40,55]. Second, the analysis incorporates Knight’s (1921) classic distinction between measurable risks that can be quantified and mitigated versus true uncertainties that resist probabilistic modeling [56]. Third, following Williamson’s (1996) adaptive efficiency framework, this study positions transaction costs as emergent outcomes of governance structure alignment that serve as diagnostic indicators of institutional fit [57]. Considering their differential manifestation, this paper argues that optimal governance choice requires the simultaneous consideration of measurable risk profiles, residual uncertainty environments, and comparative transaction cost structures across available institutional arrangements.

Among all the transaction risks faced by the project, organizer information asymmetry and opportunism activities are generally believed to be significant in the existence of and variation in transaction costs [39,58], so addressing such problems is always a non-negligible consideration in governance choice [59]. Moreover, considering the complexity of China’s collective land ownership, this research further categorizes information asymmetry into internal information asymmetry and external information asymmetry; correspondingly, opportunistic behaviors are also classified into internal opportunistic behaviors and external opportunistic behaviors.

(1) Internal Information Asymmetry

Due to the collective ownership of rural land, collecting information on the attitude and requirement of each household is inevitable in the designation, reclamation, and new construction of the “sending area”. Moreover, the confirmation and registration system of rural property has not been completed in rural China, so the investigation and dispute resolution usually cost a lot of time and human resources, which becomes the first obstacle for general investors [60].

(2) External Information Asymmetry

On the one hand, since the value of rural LDR can only be realized in the urban sector, the urban land manager (the local government) and urban land users inevitably evolve into key actors in China’s TDR operation (Figure 2). On the other hand, just like other land development projects, planning design and construction are usually contracted out to third parties. Therefore, the transaction also involves professional service companies and construction companies. Correspondingly, collecting information on the professional service market, TDR market, and financial market, as well as the detailed requirements for project application and acceptance, is also costly for project leaders.

(3) Internal Opportunistic Behavior

Whether in the private sector or the public sector, opportunistic behavior is a major source of supervision costs and enforcement costs [61]. Considering the collective ownership of China’s rural land, internal opportunistic behaviors focus on the stakeholders within the collective, such as the demotivation and holdout problems of villagers. To avoid these possible opportunistic behaviors, additional ex-ante costs on drafting and negotiating and ex-post costs on safeguarding the agreement become inevitable [62].

(4) External Opportunistic Behavior

In contrast, external opportunistic behaviors mainly focus on the stakeholders out of the village collective. Specific to China’s TDR projects, professional service companies, construction companies, and urban land users tend to adopt self-interested strategies to maximize their own profits, which may lead to skimping on labor and materials or delays in payment. Similarly, all of these behaviors require more experience or costs for contract supervision, control, and enforcement.

3.3. Alternative Governance Structures for China’s TDR Projects

Different from other land transactions, whoever would like to invest in the “production” of LDR can obtain a TDR quota, enabling them to capture the price differential between market quota values and production costs. This competition for de facto property rights has catalyzed bottom-up institutional innovation in China’s rural land governance, manifested through three distinct governance structures: (1) government-dominated, (2) market-invested, and (3) collective self-organized models (Table 3).

Table 3.

Three governance structures available for China’s TDR projects.

As the predominant approach in practice, the government-dominated model positions local authorities as both urban land managers and TDR project implementers. Under this governance structure, municipal governments take charge in all project stages, including initiation, planning, financing, supervision, and risk management. While construction activities (including demolition, reclamation, and resettlement housing) are typically outsourced to specialized firms, the government retains control over TDR quota utilization. “Produced” quotas are either traded through TDR markets (county/township level) or bundled with incomplete land use rights in primary urban land markets (county/municipal level) for investment recovery.

Under the market-invested structure, developers usually raise funds from diverse channels, especially attracting private capital with expected project returns. The government is no longer the direct implementers of TDR projects but rather the regulatory facilitators providing guidance and coordination, while market mechanisms replace administrative directives in stakeholder interest alignment. In return, investors gain the ownership of the “produced” TDR quota, which may either serve as discounted urban land acquisition permits or be sold to urban land managers or urban land users.

Under the self-organized structure, the village collective should first propose a feasible plan according to the Land Use Master Plan. Following village assembly approval and county-level land department endorsement, projects demonstrating alignment with TDR policies and local development strategies will receive approval and governmental support. Collectives employ blended financing (collective funds, villager equity, land mortgages, and subsidies) and contract professional firms for planning, implementation, and oversight. Correspondingly, the “produced” TDR quota remains collectively owned, and the project profits should be distributed among the villagers according to the contract.

3.4. Strengths of Three Governance Structures on Controlling Transaction Risks

3.4.1. Government-Dominated Structure

China’s government-dominated TDR system demonstrates distinct institutional advantages that account for its widespread adoption and effectiveness in practice. Three core strengths characterize this governance model and explain its predominance in most TDR implementations.

First, the government-led model possesses superior access to complete administrative information regarding evolving policy requirements, enabling them to navigate the shifting regulatory landscapes more effectively than market actors or local collectives. Moreover, administrative agencies have direct access to both formal regulatory requirements and informal approval processes across all implementation stages, especially the application and acceptance phases. Drawing on the privileged information position, this vertical integration of China’s land administration system can be effectively embedded to address uncertainties arising from incomplete markets and transitional institutional voids.

Second, the system possesses an enhanced governance intelligence capacity derived from its comprehensive administrative data systems and technical expertise. Government agencies maintain integrated databases spanning land use records, planning documents, and development histories, enabling evidence-based decision-making. This institutional knowledge base allows for the sophisticated identification of the spatial patterns and development constraints of ambiguous rural land, helping control both internal and external information asymmetries.

Third, the system exercises robust administrative control through multiple regulatory mechanisms. These include authority over land use conversions, compliance monitoring, and enforcement actions. The hierarchical governance structure enables coordinated implementation across departments and administrative levels (even including the village cadres), which is particularly valuable for complex, multi-jurisdictional projects. Through such an approach, this control capacity proves especially effective for controlling the opportunistic behaviors of multiple stakeholders and maintaining implementation consistency in complex TDR programs.

These institutional advantages make the government-dominated model particularly suitable for projects requiring strategic spatial planning, complex stakeholder coordination, or compliance with evolving policy frameworks. Specifically, for strategically located sending areas or projects requiring specialized technical expertise, government leadership provides credible commitments that significantly reduce negotiation costs. Moreover, this hierarchical governance structure proves especially effective for large-scale TDR projects spanning multiple villages, where standardized compensation mechanisms and centralized land registration systems facilitate repetitive transactions between project leaders and individual households. Additionally, this structure also proves particularly advantageous for TDR projects implemented under special policy frameworks, where institutional uncertainties and implementation risks are typically heightened. These projects are often designed to address unique developmental priorities or experimental reforms.

3.4.2. Market-Invested Structure

The market-invested governance model demonstrates distinct institutional strengths that render it particularly effective for specific organizations of China’s TDR projects. This approach offers three key advantages that address fundamental challenges in development rights transactions.

First, the model establishes superior incentive structures that drive efficient project implementation. By directly linking financial returns to performance outcomes, the system creates powerful motivations for all stakeholders to actively participate and optimize their contributions. This market-driven incentive mechanism generates a self-reinforcing cycle of performance improvement while simultaneously controlling opportunistic behaviors through aligned interests.

Second, the formal contractual framework governing market participants delivers measurable efficiency gains. By establishing clear performance expectations and enforceable accountability mechanisms, the system significantly reduces external opportunistic behaviors to informal arrangements. Additionally, this contractual standardization ensures consistent service delivery across multiple project components and stakeholders, which can also help control internal opportunistic behaviors.

Third, the model maintains advanced market intelligence capabilities that enhance decision-making. Through professional analysis systems, specialized expertise, and comprehensive data networks, it achieves a superior information processing capacity. These capabilities prove particularly valuable for multi-village projects, enabling effective information aggregation across geographical areas while maintaining uniform operational standards.

The combination of these attributes positions the market-invested model as the optimal governance choice for normal Linkage projects with less specificity and institutional uncertainties, where market forces play a decisive role. It demonstrates particular effectiveness in growth corridor projects involving multiple villages and requiring substantial capital mobilization. In conclusion, when properly implemented, this governance approach can create a synergistic relationship between market efficiencies and policy objectives.

3.4.3. Self-Organized Structure

The self-organized governance structure represents a distinctive approach within China’s Linkage Policy framework, deriving its operational logic from village collective ownership systems. This model embodies a cooperative organizational form that leverages rural communities’ social capital and communal relationships to encourage collective action in rural development projects.

Two fundamental characteristics define the self-organized model’s operational advantages. First, the structure benefits from superior internal information completeness due to its embeddedness within village social networks. The dense web of interpersonal relationships and shared community identity enables comprehensive information sharing about land use patterns, household circumstances, and local development needs. Second, the model demonstrates enhanced administrative control and a collective adaptation capacity through its access to multiple dispute resolution and supervision channels. These include formal village committee procedures and informal mediation mechanisms utilizing kinship networks and community elders’ authority.

Therefore, the self-organized approach proves particularly effective in two specific project scenarios. First, regarding projects involving heterogeneous community interests, when Linkage implementations encounter significant variation in villager participation willingness or competing claims among community members, the model’s endogenous conflict resolution mechanisms outperform external governance approaches. Its social embeddedness facilitates a nuanced understanding of local concerns and enables culturally appropriate negotiation processes that account for village power dynamics and kinship relationships. Second, regarding suburban sending area developments, for projects located at the urban–rural fringe, the self-organized structure benefits from a unique hybrid position. While maintaining rural institutional characteristics, suburban villages can leverage proximity to urban administrative systems and infrastructure networks. This geographical advantage enhances their capacity to coordinate competing claims while controlling complex internal opportunistic behaviors.

The self-organized governance model shares with market-invested structures a fundamental constraint in organizing TDR projects characterized by high institutional uncertainties. However, two principal operational constraints significantly restrict the model’s applicability across different project contexts. First, the structure demonstrates inherent limitations in handling projects of substantial scale or frequency. Its dependence on collective decision-making through informal institutions generates exponentially increasing transaction costs when applied to high-frequency implementations. Each repetitive negotiation cycle requires renewed consensus-building among village stakeholders, a process that becomes economically unsustainable compared to the standardized procedures of government models or the contractual efficiencies of market-based approaches. Second, the model exhibits critical deficiencies in coordinating multi-village projects. These operational shortcomings stem from two interrelated structural weaknesses: the parochial nature of village-level information systems that cannot effectively aggregate data across jurisdictional boundaries and the absence of formal governance mechanisms operating at supra-village scales. These limitations manifest most acutely in controlling the information asymmetries that emerge between villages and mitigating the opportunistic behaviors that may arise in inter-village negotiations.

3.4.4. Theoretical Hypothesis

Finally, based on the institutional analysis above, this research proposes hypotheses for the research questions stated in Section 1, refining Williamson’s classical alignment hypothesis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Transaction attributes–risks–governance structures alignment hypothesis.

Q1: Why do the three TDR models (i.e., the conventional government-dominated model, market-invested model, and self-organized model) emerge under China’s centralized land governance system?

H1.

Due to the complexity of transactions and diversity in the transaction context, the three governance structures can improve process efficiency by controlling the transaction risks with various transaction attributes.

Q2: How do they fit to various conditions to improve process efficiency?

H2.

As three key transaction attributes, specificity, uncertainty, and frequency influence governance choice because different governance models exhibit varying capacities to manage the transaction costs associated with each attribute.

H2-1.

The government-dominated governance structure demonstrates superior effectiveness in managing TDR projects characterized by the following four distinct attributes: (1) a higher location specificity, (2) obvious institutional uncertainty, (3) a higher transaction frequency, and (4) multi-village participation.

H2-2.

The market-invested governance structure demonstrates superior effectiveness in managing TDR projects characterized by the following four distinct attributes: (1) less location specificity, (2) lower institutional uncertainties, (3) a relatively higher transaction frequency, and (4) multi-village participation.

H2-3.

The self-organized governance structure demonstrates superior effectiveness in managing TDR projects characterized by the following four distinct attributes: (1) superior location specificity, (2) lowest institutional uncertainties, (3) a low transaction frequency, and (4) single-village participation.

4. Materials and Methods

As China’s paramount institutional instrument in addressing urban sprawl externalities and fostering urban–rural integration, the TDR program employs a hierarchical quota allocation system. The central government maintains ultimate authority over pilot project approval and quota distribution to ensure national policy objectives while delegating implementation autonomy to local governments. This decentralization has spawned heterogeneous local institutional environments and operational models across provinces. However, this research finds significant governance structure variation, even in uniform local institutional contexts. To understand this institutional diversity at a more micro-level and analyze its strengths in improving process efficiency, this paper introduces collective action theory into Transaction Cost Economics and explains the alignment mechanism between transactions and governance attributes.

4.1. Study Area

According to the existing literature, the Chengdu Model has been widely recognized as a successful TDR framework [58]. Therefore, to elucidate the organizational mechanisms and application conditions of China’ TDR governance, this study selects three representative cases from Chengdu Municipality. However, the existing literature predominantly focuses on implementation techniques while neglecting the unique institutional context, which is a critical oversight that limits replicability and generalizability. Addressing this gap, this paper systematically examines policy innovations first and then comparatively analyzes diverse governance structures within Chengdu’s distinctive institutional environment.

Generally speaking, Chengdu’s market-enabling strategies demonstrate five key institutional innovations: (1) Property rights clarification: the municipal government completed comprehensive rural land titling in 2010, issuing 1.5 million rural homestead use certificates and 1.8 million cultivated land management rights certificates, significantly reducing tenure insecurity. (2) Market intermediation: the establishment of the Agricultural Equity Exchange (AEE) has created an institutional platform connecting land property rights holders with land users. (3) Price stabilization: the municipal land bureau’s unified TDR quota pricing mechanism can efficiently reduce market volatility and enhance investor confidence. (4) Dispute resolution: since 2009, elder-mediated village committees have effectively resolved land conflicts and empowered collectives in land asset management. (5) Demand stimulation: local policy requires all urban land users to acquire the “Linkage” quota first either by direct “production” or an AEE purchase, which has created sustainable market demand.

4.2. Methodology

The governance structures of TDR projects in China can be categorized into three distinct models based on their primary actors: government-dominated, market-invested, and self-organized structures. For a comparative case study, this research employs a triangulated methodology, examining three representative cases that correspond to the three distinct governance structures under investigation. Specifically, this paper utilizes multiple data sources to ensure analytical robustness: official government documents, project proposals from implementing entities, land administration approval records, and systematic field observations. Specifically, to validate data credibility, semi-structured interviews are conducted with three stakeholder groups: rural residents (focus groups of 5–8 individuals in each village), local government officials (from natural resources and agricultural departments, as well as township officers), and village committee members.

4.2.1. Policy Text Analysis

This research employs a rigorous analytical approach to examine the institutional environment shaping China’s TDR program. The methodology systematically investigates policy documents across multiple governance levels and temporal phases to capture the evolving regulatory landscape (Table 4). A comprehensive classification system structures the analysis along two critical dimensions: temporal development phases and hierarchical authority levels.

Table 4.

A list of policy documents examined in this research.

The temporal analysis distinguishes between two key historical periods in policy evolution. The initial policy design stage (2004–2007) encompasses foundational documents that established the conceptual framework and regulatory parameters of the TDR program. The subsequent implementation stage (2008–present) includes operational guidelines, policy amendments, and local adaptations that reflect the program’s practical application and iterative refinement. Simultaneously, the documents are categorized according to their originating authority within China’s governance structure. At the national level, this study examines policies issued by the Central Committee and State Council, ministerial regulations, and formal legislation codifying development rights and land use governance. At the local level, the analysis incorporates regional implementation plans, pilot program guidelines, and municipal-level operational rules.

The analytical approach integrates qualitative and quantitative techniques, including a systematic content analysis of policy documents, a comparative examination of central versus local provisions, the temporal tracking of policy evolution, and the identification of intertextual relationships between documents. This multidimensional methodology enables a nuanced understanding of how China’s TDR program has developed through the interaction of top-down policy design and bottom-up implementation experiences.

4.2.2. Comparative Case Study to Examine Governance Structures

This study adopts a mixed-methods research design to systematically examine the diversified governance structures of TDR projects in Chengdu Municipality. The methodology combines quantitative sampling techniques with a qualitative case study analysis to provide both comprehensive coverage and an in-depth understanding of project implementation dynamics.

This research employs a stratified random sampling approach, selecting 98 TDR projects that represent 25% of all projects approved by the Chengdu Municipal Cadastral Centre. This sample ensures broad geographical representation across 78 distinct towns and 15 counties within the municipality. Primary data collection focuses on four key document types: official application documents, project acceptance records, villager compensation contracts, and implementation reports. Through a systematic analysis of these materials, this study identifies three predominant implementation modes: the government-dominated model, market-invested model, and self-organized model.

To complement the quantitative analysis, this research conducts detailed comparative case studies of three representative projects, each exemplifying a distinct governance structure. The first case, located in Longquanyi District, illustrates the government-dominated model with its hierarchical control mechanisms and centralized decision-making processes. The second case, from Pujiang County, demonstrates the market-invested model, highlighting private sector investment and market-based coordination. The third case, which is in Dujiangyan, showcases the self-organized model, emphasizing community-led implementation and collective action. These cases are selected based on rigorous criteria, including the geographic diversity, variation in project scale and complexity, and availability of comprehensive documentation.

4.2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews with Stakeholders

This study employs a multifaceted research approach to systematically analyze the governance mechanisms and stakeholder dynamics in Chengdu’s TDR implementation. To capture the complex interplay of governance structures and actor interactions, the investigation combines two primary data collection methods that enable both depth and breadth of analysis.

The research methodology centers on semi-structured interviews conducted with key participants across all governance levels. These in-depth interviews, ranging from 20 to 60 min in duration, engage three distinct groups of stakeholders: (1) project-level actors involved in the TDR implementation of each case, (2) county-level township government officials responsible for TDR administration, and (3) municipal department officers designing local institutional environments and overseeing program coordination (Table 5). Complementing the interview data, this study conducts systematic comparative field research across all case sites. This ethnographic component involves a direct observation of project implementation and an analysis of the spatial arrangements resulting from different governance approaches.

Table 5.

Semi-structured interviews with stakeholders.

5. Results

5.1. Government-Dominated TDR Project

(1) Transaction Context

The inaugural government-dominated TDR project was implemented in Longquanyi District, Chengdu, with the sending area encompassing two adjacent administrative villages (Village S and Village Z) in Town C. Village S, located 37 km from Chengdu’s urban core, exhibited a predominantly agricultural demographic (65.45% of population) with 34.8% cultivated land area. Its per capita income exceeded the Sichuan provincial average by 28.55%, partially attributable to proximity (4 km) to a scenic tourism zone. Contrastingly, Village Z featured higher forest coverage (cultivated land: 23.26%) with an economy centered on fruit cultivation and labor export, yielding average incomes commensurate with provincial rural standards.

Conversely, Longquanyi District presents a unique geospatial paradox: while over 40% of its territory comprises mountainous terrain that was affected by the Wenchuan Earthquake, it simultaneously functions as Chengdu’s secondary urban development zone. To reconcile these contrasting characteristics, the district government strategically synchronized rural land adjustments with eco-migration initiatives. Specifically, it leveraged national policy frameworks to bundle projects: first, by establishing cross-subsidization mechanisms to use urban land revenues to fund rural development and, second, by transferring land development rights from ecologically fragile zones to urbanizing plains.

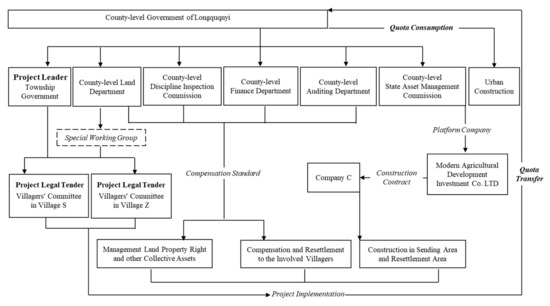

(2) Implementation Framework and Stakeholder Roles

At the beginning, a working group was established by the land bureau of Longquanyi District in December 2009, and the members visited several villages to collect basic information regarding the land use structure and villagers’ attitude toward the resettlement. After selecting the two villages to be the sending area, the working group executed a bidding agency contract in September 2008 and entrusted several professional companies with the detailed planning design, construction supervision, and land consolidation from September 2009 to March 2011. Then, the working group and villagers’ committees (of the two administrative villages) advertised this TDR project to the collective members and registered villagers who were interested in participating. In March 2012, this project obtained final approval from the Provincial Department of Land and Resources of Sichuan Province.

The implementation of Chengdu’s TDR project progressed through two distinct operational phases: (1) the initial quota production phase, conducted between December 2014 and April 2015, and (2) the resettlement construction phase, completed in 2017. In the implementation process, the project implementation framework involved four core institutional actors, each performing distinct yet complementary functions (Figure 4). The first one was the township government of the sending area, which acted as the designated project owner and assumed primary implementation responsibilities, including overall coordination and compliance oversight. The second one was Longquan Modern Agricultural Development Investment Co., Ltd., which is a state-owned company established by the State Asset Management Commission of Longquanyi District. As the financial and procurement platform, its dual role encompassed project financing and competitive bidding for construction contracts. The third one was Company C, which participated in the TDR project through Build–Operate–Transfer (BOT) agreements with the state-owned platform company. By participating in this TDR project, this private entity was secured to establish public–private partnership for urban development, such as preferential access to high-value agricultural projects and integrated tourism complexes. The fourth key entity was the two villagers’ committees. Functioning as legal tenderers, these grassroots governance bodies executed five critical functions: project administration and fund supervision, resettlement coordination and dispute mediation, collective land rights management, public order maintenance, and contract execution.

Figure 4.

Governance structure of the government-dominated TDR project.

Moreover, the county government established a cross-departmental supervision system involving the Land Resources Bureau (project review and audit), Finance Bureau (compensation disbursement), Discipline Inspection Commission (compliance monitoring), and Audit Bureau (financial oversight). All compensation procedures adhered to Longquanyi’s Land Acquisition Compensation Standards to ensure policy consistency.

(3) Transaction Risks and Transaction Costs

In total, this TDR project “produced” 311.75 mu of the TDR quota for the urban sector, contributed 1.6 mu of cultivated land to the total amount, reserved 30.2 mu of the quota for rural development, and resettled all villagers in another town in Longquanyi District (only 4 km away from the city expressway). The produced TDR quota was formally transferred to the county-level land department in May 2015. The land use structure in the sending area changed, with an increase of 11% in cultivated land and a decrease of 49.47% in rural homestead.

First of all, this TDR project exhibited substantially higher implementation costs than typical cases due to two primary factors. First, the sending area’s location in earthquake-damaged hilly terrain significantly increased the technical difficulties and costs for building demolition and land reclamation. Second, the resettlement of participating villagers in modern residential districts near urban centers resulted in elevated construction expenses. Due to the lack of professional and rigorous budget management, this project experienced severe cost overruns, with final expenditures totaling CNY 2.339 billion, nearly triple the initial budget of CNY 805.66 million.

Additionally, this TDR project represents an exceptionally large-scale intervention, encompassing 539 rural land parcels (553.0276 mu), 995 households, and 3149 villagers. The project size introduced significant implementation challenges during the initiation phase. Specifically, the fragmented rural homesteads required extensive cadastral surveys and land use assessments, and diverse villager attitudes necessitated large-scale social surveys and participatory negotiations. Thus, collecting information on the fragmented homestead and the attitudes of various villages was extremely costly in the project initiation stage. Moreover, due to the evolving resettlement requirements from participating villagers, the whole process encountered significant delays, which necessitated repeated applications for provincial-level regulatory approvals, with each approval cycle requiring several months. Thus, these procedural delays substantially impacted the project timeline and budgetary outcomes.

However, this large-scale TDR project still achieved remarkable administrative cost savings through its comparative institutional advantages in controlling transaction risks: digital cadastral mapping cut the survey time; the structured village consultations organized by the township government minimized disputes; the standardized compensation templates reduced negotiation times; and the streamlined administrative processes eliminated bureaucratic redundancies. Finally, this governance reduced the expenses from CNY 231.36 million (28.72% of the budget) to CNY 25.11 million (5.94% of the actual costs), which demonstrates how the government-dominated structure can overcome the scale–cost paradox in rural land development projects.

5.2. Market-Invested TDR Project

(1) Transaction Context

This second case examined a market-invested TDR project implemented in Pujiang County, situated within Chengdu’s third development zone. As a significant agricultural producer in Sichuan Province, Pujiang County maintains its distinctive land use patterns, with cultivated land accounting for 30.87% and forested land comprising 34.4% of its total territory. This agricultural modernization strategy stimulated an innovative balancing of agricultural preservation (particularly for high-value crops, including citrus, gooseberry, and tea) with urban expansion needs.

In Pujiang County, most territory is situated in gently sloping hilly terrain, which significantly facilitated the building demolition and land reclamation processes. Additionally, the resettlement strategies allowed villagers to remain within their original community through flexible in situ relocation, which effectively contained the new construction expenses. Thus, these TDR projects yielded substantial cost efficiencies, with demolition expenses being 30.8% lower than provincial averages and infrastructure costs being reduced by 44.5%. Finally, the unified purchasing price for the TDR quota in Chengdu Municipality (established at CNY 300,000/mu) significantly exceeded its average “production” cost (CNY 250,000/mu) in Pujiang County, and this pricing differential served as a powerful market stimulus for private investors. In Pujiang County, more than 70% of TDR projects have been invested in by private capital and driven by market mechanisms.

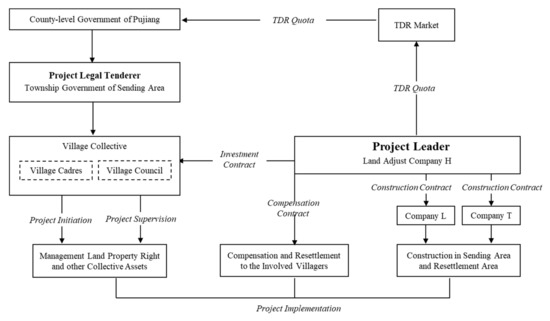

(2) Implementation Framework and Stakeholder Roles

Overall, these multiple potential investors and the corresponding governance arrangements provided more options for the villagers, which played a pivotal role in protecting their interests. Specific to this case, the sending area exclusively involved Village J, where tea plantations cover 41% of its total area and the conventional cropland covers 41.72%. Motivated by other successful TDR projects in neighboring villages, the local cadres in Village J identified and evaluated potential investors through the Agricultural Equity Exchange (AEE). After initially engaging a developer, the villagers’ congress exercised its oversight authority to terminate the partnership due to the inadequate resettlement designs, and it subsequently selected private investor Company H through competitive processes.

After the county land department completed the project plan in October 2015, Company H assumed primary responsibility for project financing and project execution and commissioned professional planning institutes for resettlement planning. Learning from the lessons of the previous company, Company H implemented a comprehensive community engagement strategy during the resettlement planning phase. Through structured consultations and surveys, this company systematically collected and analyzed the villagers’ attitudes toward the TDR project, ensuring that their needs and preferences informed the final resettlement design. Following this participatory planning process, Company H identified the willing participants, documented the existing homestead conditions, and then completed the project application and obtained formal approval from the provincial land department in April 2016.

After receiving the formal TDR project approval, the implementation process progressed through three key stages (Figure 5). At the contract finalization stage, Company H negotiated detailed compensation contracts with participating households, establishing clear timelines and comprehensive compensation packages. At the reclamation and new construction stage, the concrete operational responsibilities were allocated through professional service contracts: the land reclamation to Company L and the resettlement construction to Company T. At the quota transaction stage, the “produced” TDR quota (361.46 mu) was formally transferred to Company H and subsequently sold to Pujiang County government at the market rate of CNY 300,000/mu through the AEE. Since this project adopted the simultaneous implementation of sending area consolidation and resettlement area construction from 2015 to 2017, operational efficiency was significantly enhanced.

Figure 5.

Governance structure of the market-invested TDR project.

(3) Transaction Risks and Transaction Costs

This TDR project encompassed 101 rural land parcels totaling 394.7475 mu in hilly terrain and involved 225 households (828 villagers, accounting for 49.3% of the population in Village J). After the TDR projects, the villagers continued to live within their original administrative boundaries, but the resettlement communities became closer to transportation infrastructure, specifically only 4 km from the city expressway. Thus, this TDR project increased the population density from 2.09 to 13.33 persons per mu, reclaimed 394.7475 mu rural homestead into cultivable land, and “produced” 361.46 mu of the TDR quota to support the municipal development strategy.

To effectively reduce the transaction costs, the multiple stakeholders made full use of their advantages in controlling the transaction risks and made coordinated efforts. Firstly, the village council expanded to 37 members (6.5% of households) for enhanced participation. On the one hand, it established a robust oversight mechanism to ensure project quality and accountability, including construction quality inspection teams, a public infrastructure monitoring team, and a financial transparency committee. On the other hand, the expanded village council served as both a representative body and an enforcement mechanism. Specifically, through the systematic documentation and aggregation of villager requirements, the council created a robust bottom-up information channel for Company C and maintained oversight of agreement compliance through a flexible social network. Finally, this governance structure demonstrated remarkable process efficiency, as evidenced by its administrative cost performance. With administrative expenses constituting only 5.82% of the total project costs, it substantially outperformed comparable TDR projects in Sichuan Province, which typically reported 6.5–7.2% administrative cost ratios.

5.3. Self-Organized TDR Project

(1) Transaction Context

The third case examined a self-organized TDR project implemented in Dujiangyan County, which was severely affected by the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. This area is characterized by a challenging topography, with 65.79% of the land located in mountainous and hilly terrain. The sending area focused on Village L in Town H, one of the most remote administrative villages in Dujiangyan County, where the landscape features 66.23% forest coverage, and agricultural production specializes in kiwi berries and medicinal plants. Additionally, the local economy also relies heavily on eco-tourism, and the National Nature Reserves, as well as scenic spots, have generated more than CNY 50 million in annual revenue since 2007, accounting for 81.65% of the total income of Town H. Since this village is just 10 km away from the earthquake epicenter, over 90% of rural residential houses were completely destroyed, which created urgent reconstruction needs.

To facilitate the investment of private capital in post-disaster reconstruction, the municipal government implemented a comprehensive package of preferential policies around TDR projects, including flexible land use regulations in the rural sector, tax incentives, streamlined credit and loan mechanisms, and expedited approval processes. Additionally, several local governments in other provinces were also required to participate in the reconstruction, significantly improving the living conditions of the victims. After the Wenchuan Earthquake in 2008, these measures enabled Town H to complete more than 40 TDR projects and attract approximately CNY 4 billion in reconstruction and ecological preservation, which not only solved the residential problems for the villagers but also provided them with a long-term income. However, these market-invested, government-dominated TDR projects failed to encompass all affected villages, as exemplified by Village L.

(2) Implementation Framework and Stakeholder Roles

To accelerate post-disaster reconstruction, the local governments in Sichuan Province established a comprehensive institutional framework for TDR projects, incorporating four primary approaches: government-dominated resettlement, market-driven resettlement, collective villager cooperative resettlement (i.e., the self-organized structure in this research), and one-time buyout programs. Specifically, villagers selecting cooperative resettlement could receive financial assistance and institutional support from county-level governments. Village J is an administrative village consisting of four residential groups, with a total population of 480. Due to its remote location, it was overlooked by both the local government and market investors. Recognizing the urgent need for housing reconstruction, the village cadres independently initiated a TDR project.

Undoubtedly, the village collective played a vital role in this project organization (Figure 6). During the initiation stage, the collective conducted door-to-door surveys to assess land use conditions and villagers’ willingness to participate in the TDR program. Subsequently, a democratically elected survey team was formed, and they publicly disclosed the measurement results to all villagers. After obtaining formal approval from the provincial land department in December 2010, the collective secured financing based on the approved Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) quota and commissioned the Beijing Planning Institute to design the resettlement area. Through village assemblies, participants collectively determined compensation standards, land tenure adjustment methods, and the selection of resettlement sites. Through competitive bidding, the collective subsequently contracted the technology firm H2 to handle formal project applications and selected Company H1 for land adjustment, as well as new construction. During the quota “production” stage, the village collective played the role of project owner. To ensure effective project oversight and address community needs comprehensively, the collective instituted weekly Thursday meetings to gather villagers’ feedback, report on project progress, and coordinate subsequent development plans. Generally speaking, this TDR project achieved remarkable participation, with over 97% of involved villagers joining the initiative. Land consolidation was completed in May 2012, and construction in the resettlement areas was completed in 2014.

Figure 6.

Governance structure of the self-organized TDR project.

(3) Transaction Risks and Transaction Costs

According to the administrative regulations in Sichuan Province, a financial commitment certificate constituted a mandatory requirement for TDR project application. For most self-organized rural land development initiatives, fundraising becomes the primary challenge during project initiation. In this particular case, to mitigate information asymmetry in the TDR market, the county government facilitated coordination between the TDR quota “producer” (the collective of Village L) and the quota purchaser (Pi County, located in Chengdu Municipality’s secondary development zone). Based on the resulting quota purchase agreement, the collective of Village L became eligible to apply for mortgage loans, valued at the prevailing market rate of the TDR quota (CNY 150,000 per mu).

Another institutional mechanism for risk management in this case was the mature self-organization capabilities of the collective. With a well-established tradition of democratic governance since 1984, village affairs are routinely determined through villager council or congress. This institutional framework enabled most implementation conflicts to be resolved through autonomous mediation. A notable example occurred when a village cadre, despite owning a property in good condition, still voluntarily relinquished his house to facilitate the resettlement program. This action effectively addressed participation concerns among other villagers. As a result, despite the initial resistance from some collective members, the project still successfully achieved its planned targets and encountered minimal obstacles during official review processes.

Based on the comparative case studies above, the major differences among the three Linkage models are summarized in Table 6. Notably, while the completion report incorporates TDR costs—including investments in receiving areas that fall beyond this study’s scope—the management costs are calculated by allocating a proportion of total costs to both sending and resettlement areas and then applying this ratio to the total management costs.

Table 6.

Major differences among governance structures.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

To address the negative externalities of rapid urban sprawl, China’s central government implemented the “Linkage” Policy in 2004, which has become a key institutional mechanism for managing urbanization and fostering urban–rural integration. To explain the emergence of governance diversity within China’s centralized land system and evaluate different approaches to enhancing TDR project process efficiency, this study first conceptualizes TDR transactions and sub-transactions and then systematically evaluates the associated organizational risks in TDR organization. Based on five critical dimensions—dominant actors, institutional tools, contract types, financing mechanisms, and quota ownership—this paper identifies three distinct governance modes: government-dominated, market-invested, and self-organized modes. To locate these available governance structures in the institutional map, this paper takes the perspective of Transaction Cost Theory and discusses the advantages of each structure in risk mitigation and efficiency optimization. To provide empirical evidence, this research employs a comparative case study methodology, analyzing three representative cases corresponding to each governance mode through data triangulation to ensure robust findings.

This study’s theoretical and empirical analyses yield three key findings regarding China’s TDR system. First, due to the program’s inherent complexity and substantial financial requirements for quota “production”, effective implementation requires leveraging complementary strengths from multiple stakeholders. Second, our examination of efficiency optimization reveals that transaction risks are the primary source of transaction costs, as well as the central concern of all governance structures. These distinct governance modes have consequently emerged in different transactional contexts based on their comparative advantages in risk mitigation. While de facto land development rights have encouraged bottom-up participation in TDR projects, the persistent dual land system still poses some institutional barriers for potential project leaders—including both internal and external information asymmetries and opportunistic behaviors. Third, beyond governance structure selection, we find that local institutional innovations and collective action mechanisms can substantially enhance governance efficiency.

In summary, China’s TDR program offers valuable lessons for developing countries seeking to enhance urban–rural coordination. Considering its interactive effects with population density, this program can also serve as a mechanism to accommodate intensive development needs within strict land use constraints, necessitating a national trading platform to respond to various regional population densities. This program demonstrates the advantages of governance diversity in aligning multiple stakeholder interests and adapting to varied transaction contexts at the project level, as well as the adaptive responses to local conditions and constraints within central policy frameworks. Moreover, this paper also establishes precise governance–transaction alignment mechanisms and draws some preliminary conclusions. However, due to the limitations of the case study methodology, these conclusions still need more data for support in the next stage. Moreover, the actual impacts of TDR projects on rural development also need long-term observation.

Funding

This research was funded by the Humanities and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 20YJC630119).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Bosin Tang, as well as all the anonymous referees, for their helpful comments and suggestions, which greatly improved this article. Any errors are the author’s responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Ajagun, E.O.; Ashiagbor, G.; Asante, W.A.; Gyampoh, B.A.; Obirikorang, K.A.; Acheampong, E. Cocoa eats the food: Expansion of cocoa into food croplands in the Juabeso District, Ghana. Food Secur. 2021, 14, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Liu, Y.; Webster, C.; Wu, F. Property rights redistribution, entitlement failure and the impoverishment of landless farmers in China. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1925–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, A.; De Olde, E.; Candel, J.; de Boer, I.; Ripoll-Bosch, R. The promised land: Contrasting frames of marginal land in the European Union. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Wu, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, C.; Ye, Y.; Zheng, G. Developing an urban sprawl index for China’s mega-cities. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 2730–2743. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Burli, P.; Lal, P.; Wolde, B.; Jose, S.; Bardhan, S. Perceptions about switchrass and land allocation decisions: Evidence from a farmer survey in Missouri. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffyn, A.; Dahlstrom, M. Urban-rural Interdependencies: Joining up Policy in Practice. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocheci, R.M.; Petrisor, A.I. Assessing the negative effects of suburbanization: The urban sprawl restrictiveness index in Romania’s metropolitan areas. Land 2023, 12, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Buchmann, C.M.; Schwarz, N. Linking urban sprawl and income segregation—Findings from a stylized agent-based model. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Guo, X.; Yin, W. From urban sprawl to land consolidation in suburban Shanghai under the backdrop of increasing versus decreasing balance policy: A perspective of property rights transfer. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 878–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Tang, B. Institutional Change and Diversity in the Transfer of Land Development Right in China: The Case of Chengdu. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tao, R.; Wang, L.; Su, F. Farmland Preservation and Land Development Rights Trading in Zhejiang, China. Habitat Int. 2009, 34, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q. Property Rights Delineation: The Case of Chengdu’s Land Reform. Int. Econ. Rev. 2010, 2, 54–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, Z. Institutional Diversity of Transferring Land Development Rights in China—Cases from Zhejiang, Hubei, and Sichuan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibriya, S.; Bessler, D.; Price, E. Linkages between Poverty and Income Inequality of Urban–rural Sector: A Time Series Analysis of India’s Urban-based Aspirations from 1951 to 1994. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2019, 26, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salet, W. Instruments of land policy: Dealing with scarcity of land. Town Plan. Rev. 2018, 89, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The Problem of Social Cost. J. Law Econ. 1960, 3, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, P. Nationalising development rights: The feudal origins of the British planning system. Environ. Plan. B-Plan. Des. 2002, 29, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Chen, S. Analysis of the Price of Development Right of Agricultural Land in China. Asian Agric. Res. 2011, 3, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Machemer, P.; Kaplowitz, M. A Framework for Evaluating Transferable Development Rights Programmes. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2002, 45, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Beckmann, V. Diversity of Practical Quota Systems for Farmland Preservation: A Multi-country Comparison and Analysis. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.L.; Feng, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.L.; Qu, F.T. A comparative study between the hook of urban construction land increase and rural residential land decrease policy in China and transferable development rights policy in US. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 35, 143–148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Demsetz, H. Towards a Theory of Property Rights. Am. Econ. Rev. 1967, 57, 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Fang, Y.W. Study on institutional construction of cultivated land development right. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 23–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kan, K.; Chen, X. Land speculation by villagers: Territorialities of accumulation and exclusion in peri-urban China. Cities 2021, 119, 103394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiama, K.O.; Bennett, R.M.; Zevenbergen, J.A. Land consolidation on Ghana’s rural customary lands: Drawing from the Dutch, Lithuanian and Rwandan experiences. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 56, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, A.; Azadi, H.; Scheffran, J. Agricultural land fragmentation in Iran: Application of game theory. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 105049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.L.; Long, T.Y. Does Market-Orientated Land Consolidation Promote Rural Revitalization: Based on the Investigation of 1187 Farmers in Chengdu. China Land Sci. 2017, 34, 70–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Uriel, J.M.; Camerin, F.; Hernández, R.C. Urban Horizons in China: Challenges and Opportunities for Community Intervention in a Country Marked by the Heihe-Tengchong Line. In Diversity as Catalyst: Economic Growth and Urban Resilience in Global Cityscapes; Siew, G., Allam, Z., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Urban Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J. Comprehensive land consolidation as a development policy for rural vitalisation: Rural In Situ Urbanisation through semi socio-economic restructuring in Huai Town. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]