A Hybrid Model for Land Value Capture in Sustainable Urban Land Management: The Case of Türkiye

Abstract

1. Introduction

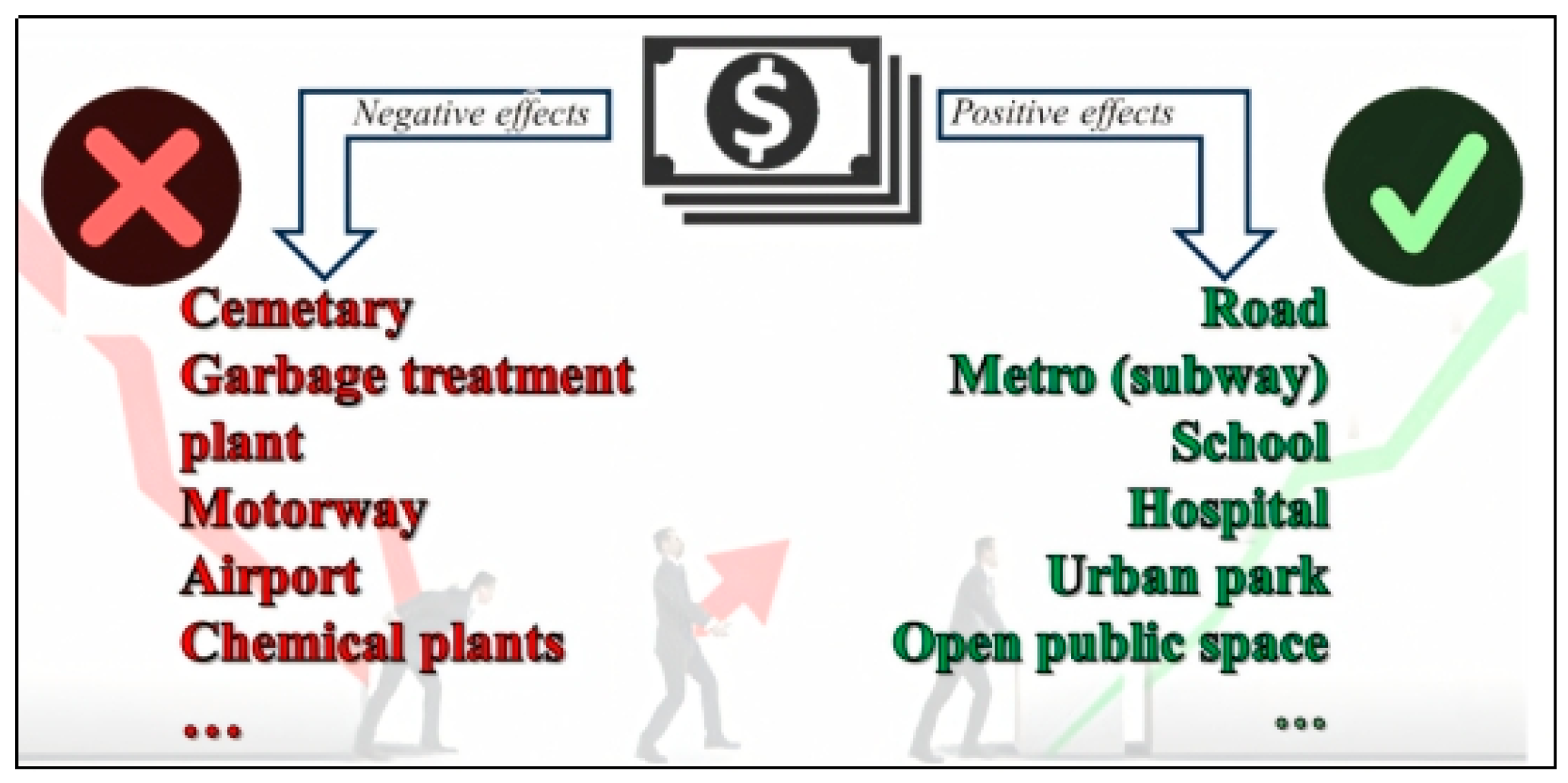

1.1. Theoretical Background of LVC

1.1.1. Funding Arrangements for Public Services

1.1.2. LVC Instruments

- Tax- and fee-based methods, including property taxes and betterment charges, which levy contributions proportionate to value gains.

- Development-based methods, which realize value increases through mechanisms such as the sale or lease of land, transfer of development or air rights, land readjustment, and urban redevelopment.

1.1.3. Why Capturing Value Matters?

1.2. Current LVC Mechanisms in Türkiye

1.2.1. The Value Increase Share

1.2.2. Contribution Fees for Municipal Expenditures

1.2.3. Land Readjustment

2. Materials and Methods

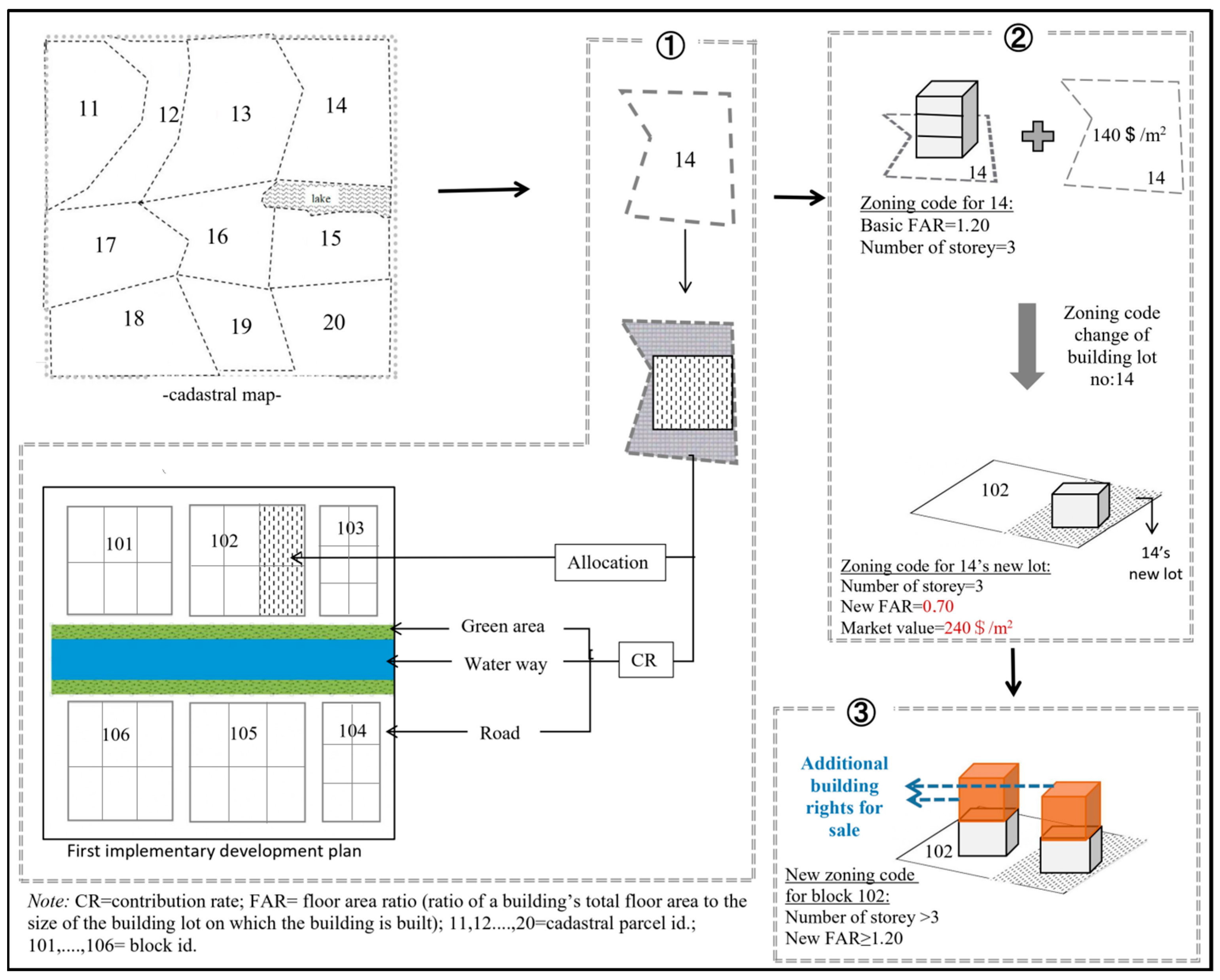

2.1. Proposed Mechanism: A Hybrid Model Based on the Change in Development Rights

2.2. Proposed LVC Scheme: Hybrid LR (hLR)

- (i)

- Preparation phase;

- (ii)

- Implementation phase;

- (iii)

- Distribution phase;

- (iv)

- Secondary zoning plan—making phase.

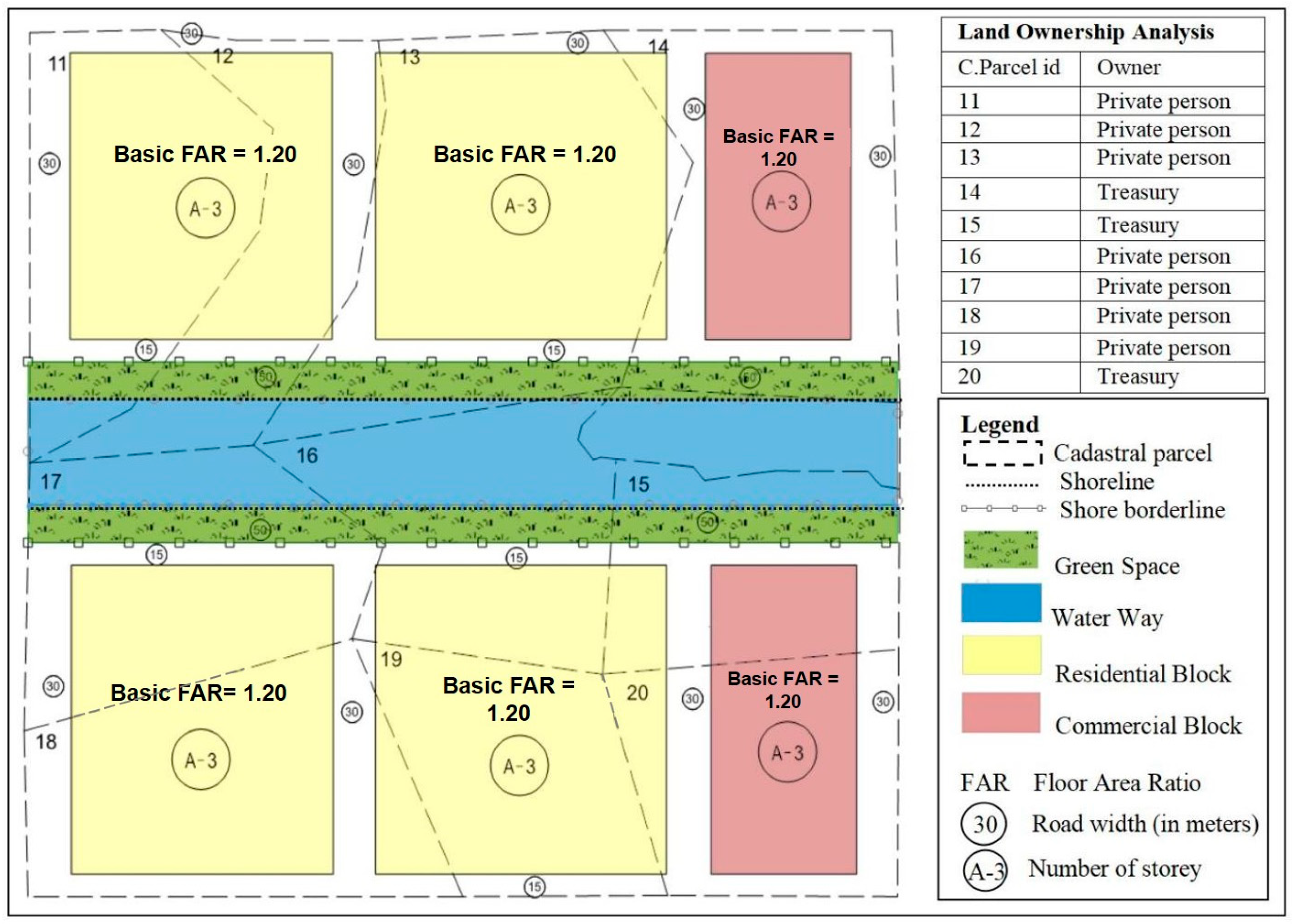

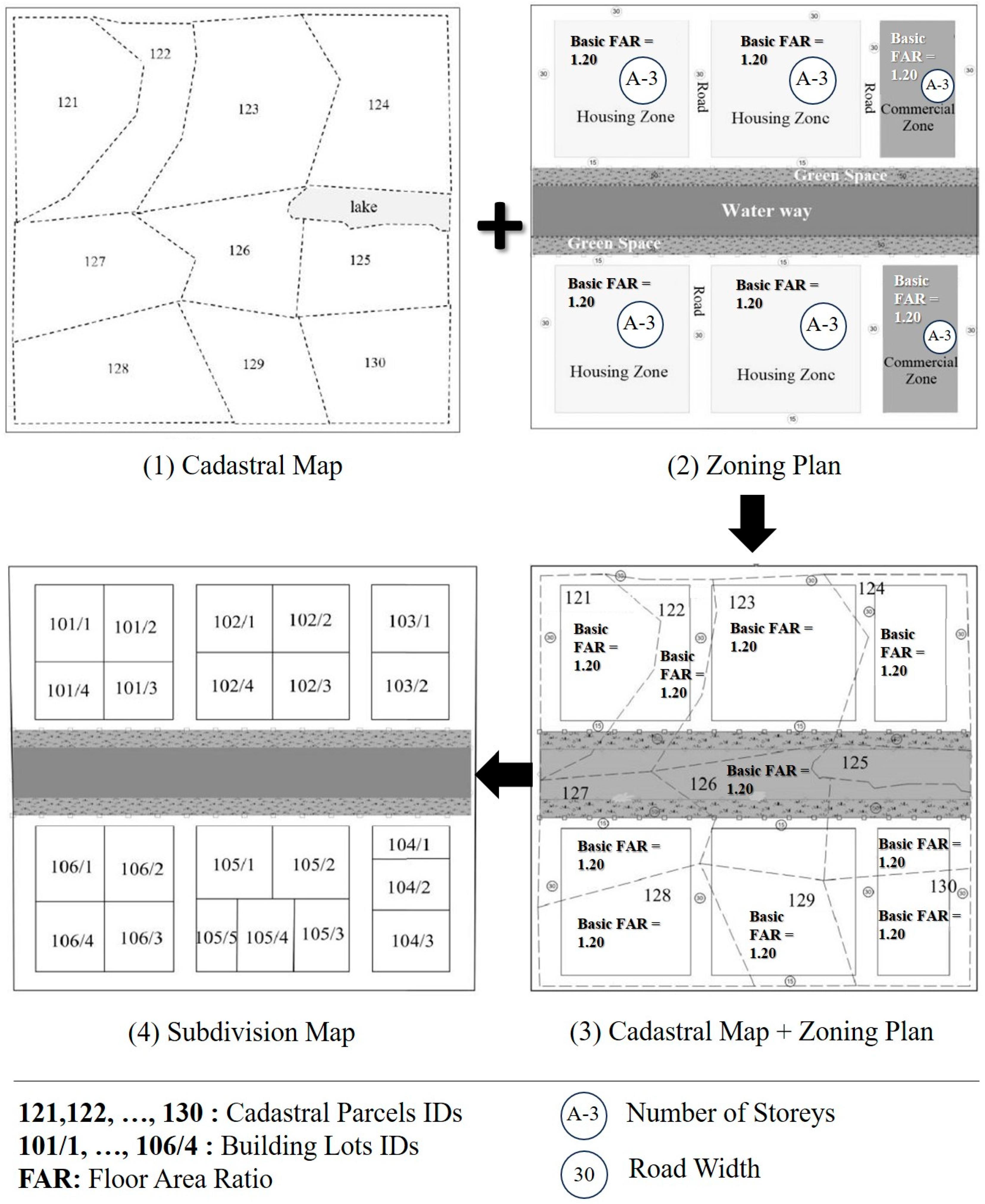

2.2.1. The Preparation Phase of the hLR

- i.

- Ownership analysis: Treasury land is designated for commercial uses (e.g., hotels, shopping centers) so that sales proceeds after LR can generate revenue for local governments and help fund infrastructure costs.

- ii.

- Zoning allocations: Land uses must address projected population needs—residential, commercial, green space, infrastructure and transport—in line with current legislation. Accurate population estimates are essential, as they determine requirements for roads, parking and commercial areas [65]. The primary zoning plan is therefore designed with high-density targets but low initial floor-area ratios (FAR), enabling increased density in the secondary plan to achieve cost recovery. Flexibility in FAR adjustments during the secondary zoning stage is fundamental, since cost recovery depends on the ability to increase development rights.

- iii.

- Definition of basic development rights: Unlike models such as São Paulo’s CEPAC or Porto Maravilha certificates, Türkiye’s Zoning Law No. 3194 does not explicitly define a “basic development right.” Internationally, a basic FAR is often set (e.g., 1–2 in São Paulo), with payments required for development above that threshold [36,66,67]. In Türkiye, maximum FAR values within zoning plans—typically ranging from 0.20 to 3, though reaching up to 11 in Istanbul—are established by law [68,69].

2.2.2. The hLR Implementation Phase

2.2.3. The hLR Distribution Phase

- (i)

- Cadastral Status Value Map (Pre-LR Parcels)

- (a)

- Parcel type: Parcels containing buildings are valued as if undeveloped, with no consideration of anticipated zoning changes.

- (b)

- Valuation date: The date of the municipality’s formal LR implementation decision is used, and all market data observed prior to this date are included.

- (c)

- Valuation method: Market values are determined using the sales comparison approach.

- (d)

- Comparable selection: Comparables are selected from parcels within the same zoning plan that have not undergone LR.

- (ii)

- Building Block Value Map (Post-LR Lots)

- (a)

- Block type: Each newly created building block is valued as though undeveloped, with the provisions of the new zoning plan taken into account.

- (b)

- Valuation date: The date on which subdivision plans are approved serves as the cutoff for all valuation data.

- (c)

- Valuation method: Market values are established using the sales-comparison approach.

- (d)

- Comparable selection: Comparables are drawn from the set of building blocks formed under the approved LR subdivision, excluding any lots subject to further LR proposals.

- (iii)

- Payment Terms

- (iv)

- Benefits for Landowners

- Fair share of uplift: Compensation is calculated transparently by comparing pre- and post-LR values.

- Flexible payment terms: Payment may be deferred until property sale or made in instalments via escrow, thereby removing immediate liquidity pressures.

- Tradable rights: Additional development rights are issued as a distinct asset that can be sold on secondary markets, enhancing owner liquidity.

- Predictable development potential: Bonus FAR allocations are legally codified and recorded, providing planning certainty for future development.

- Value enhancement: Public investments financed through hLR, such as infrastructure upgrades, further increase property values.

- (v)

- Contribution Rate Ratio (CRR) and Distribution

- NDRi: new development right of building lot i (new FAR);

- MVCPi: market value of cadastral parcel i;

- BDR: basic development right (basic FAR);

- MVBLi: market value of building lot i.

2.2.4. The hLR Secondary Zoning Plan Phase

3. Results

Application of the Model Through a Sample Scenario

4. Discussion

- The Swiss regulation requiring the public sharing of 20–50 percent of value increments is adaptable as a fixed-rate redistribution mechanism within the hLR framework [19].

- The revolving fund mechanism implemented in the Aarhus Ø project in Denmark is compatible with the hLR model by addressing municipal liquidity and pre-financing needs [18].

- The transplantation of developer obligations from Munich to the Czech Republic has shown that the tradable development rights (TDR) dimension can be adapted to different regulatory systems, thereby providing flexibility to the hLR approach [19].

- The “net land take” metrics developed by [17] demonstrate the potential alignment of the hLR model with international sustainability targets.

4.1. Integration into the Valuation Legislation and the Planning System

4.2. Stakeholder Reactions and Participation

4.3. Changes in the Property Structure and Restrictions on Property Rights

4.4. Cost Recovery

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRR | Contribution Rate Ratio |

| FAR | Floor Area Ratio |

| hLR | Hybrid Land Readjustment |

| LVC | Land Value Capture |

References

- Uzun, B.; Celik Simsek, N. Upgrading of illegal settlements in Türkiye; the case of North Ankara Entrance Urban Regeneration Project. Habitat. Int. 2015, 49, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jones, C.A.; Dunse, N.A.; Li, E.; Liu, Y. Housing Prices and the Characteristics of Nearby Green Space: Does Landscape Pattern Index Matter? Evidence from Metropolitan Area. Land 2023, 12, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Murakami, J.; Hong, Y.H.; Tamayose, B. Financing Transit-Oriented Development with Land Values: Adapting Land Value Capture in Developing Countries; Urban Development Series; Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, E.; Alptekin, E. Increment Value Share as a Kind of Zoning Rent Tax: Determinations and Suggestions in the Light of Current Data. Maliye Derg. 2022, 183, 142–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, F. Gayrimenkul Rantlarının Vergilendirilmesi. Vergi Dünyası 2011, 361, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hacıköylü, C. Taxation of Income from Selling Property: Changes of New Income Tax Law Draft. Int. J. Public Finance 2016, 1, 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk, S.S. Value capture capacity of area-based land readjustment (lr) in Türkiye. In Proceedings of the XXCI FIG Congress, Istanbul, Turkey, 6–11 May 2018; pp. 6–11. Available online: https://fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2018/ppt/ts11g/TS11G_turk_9306_ppt.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Uzun, B.; Yıldırım, V.; Çoruhlu, Y.E.; Yıldız, O.; Terzi, F.; Atasoy, B.A. Enhancing Turkish land readjustment via a combination of IPA-based on SWOT and workshops. Land Use Policy 2024, 144, 107245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, H.C.; Lenard, D. Can private finance be applied in the provision of housing. In Proceedings of the FIG XXII, International Congress, Washington, DC, USA, 19–22 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, G.E. Land Leasing and Land Sale as an Infrastructure-Financing Option (English); Policy, Research working paper; no. WPS 4043; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/133061468142165168/Land-leasing-and-land-sale-as-an-infrastructure-financing-option (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Suzuki, H.; Cervero, R.; Luchi, K. Transforming Cities with Transit: Transitnd Land-Use Integration for Sustainable Urban Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanization Council. Comission Reports. 2009. Available online: https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/kentges/editordosya/komisyon_raporlari.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Alıcı, A.; Battal, Ü. Airport project financing in Türkiye, research on problems and solutions. In Bilimsel Araştırmalar Kitabı-İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler II; Yalçın, A., Ed.; Akademisyen Publishing House: Ankara, Turkey, 2018; Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Global Compendium of Land Value Capture Policies; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G.E.; Kaganova, O. Integrating Land Financing into Subnational Fiscal Management; Policy Research working paper; no. WPS 5409; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/173371468149668444/Integrating-land-financing-into-subnational-fiscal-management (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Gracia, N.L.; Young, C.; Lall, S.V.; Vishwanath, T. Leveraging Land to Enable Urban Transformation Lessons from Global Experience; Policy Research Working Paper; no. WPS6312. 2013. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/249541468330350173/pdf/wps6312.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Botticini, F.; Auzins, A.; Lacoere, P.; Lewis, O.; Tiboni, M. Land take and value capture: Towards more efficient land use. Sustainability 2022, 14, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canelas, P.; Noring, L. Governmentalities of land value capture in urban redevelopment. Land Use Policy 2022, 122, 106396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengstermann, A.; Götze, V. Planning-related land value changes for explaining instruments of compensation and value capture in Switzerland. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Upzoning and value capture: How US local governments use land use regulation power to create and capture value from real estate developments. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cal, S. Türkiye’de Kamu Hizmeti ve İmtiyazın Dönüşüm Öyküsü; TOBB: Ankara, Turkey; Afşaroğlu Press: Ankara, Turkey, 2008. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Akar, H. Analysıs of Highways Expenditures As Public Infrastructure Investments in the Process of Transition to the Green Economy. Ph.D. Thesis, Public Finance Program, Bursa Uludağ University, Bursa, Turkey, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Irmak, E. An evaluation of using infrastructure investment trusts for financing public investments and infrastructure investments. Master’s Thesis, Business Administration Program, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- SaBD (Strategy and Budget Directorates). PPP Project Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://www.sbb.gov.tr/koi-gostergeleri/ (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Yankaya, U.; Çelik, H.M. İzmir Metrosunun Konut Fiyatları Üzerindeki Etkilerinin Hedonik Fiyat Yöntemi İle Modellenmesi. Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi İktisadi İdari Bilim. Fakültesi Derg. 2005, 20, 61–79. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Tanrıvermiş, Y.; Keskin, E.; Güneş, P. Analysis About the Effects of Plan Changes In Transportation Systems on Value Increase. Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sos. Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2022, 49, 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuzdurmaz, A.; Karadağ, M. The Main Determinants of The Regional Public Investment Policies in Türkiye. Ege Acad. Rev. 2014, 14, 649–660. [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette. Municipal Revenues Law (in Turkish: Belediye Gelirleri Kanunu). 1981. Available online: https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=2464&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Polat, S. The Taxation of Public Sourced Real Property Value Increments: A Proposal for Türkiye. Ph.D. Thesis, Karadeniz Teknik Üniversitesi, Trabzon, Turkey, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Smolka, M.O. Implementing Value Capture in Latin America: Policies and Tools for Urban Development; Policy Focus Report; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.lincolninst.edu/app/uploads/legacy-files/pubfiles/implementing-value-capture-in-latin-america-full_1.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Ingram, G.K.; Hong, Y.H. (Eds.) Land Value Capture: Types and Outcomes. In Value Capture and Land Policies; English Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.lincolninst.edu/app/uploads/legacy-files/pubfiles/value-capture-and-land-policies-chp.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Chen, Y.; Chau, K.W.; Yang, L. How the combined use of non-negotiable and negotiable developer obligations affects land value capture: Evidence from market-oriented urban redevelopment in China. Habitat. Int. 2022, 119, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçeşme, H. The Instruments Used in Implementation of Ground Plans and Transfer of the Urban Annuity Cost to the Public-Application of Article 18. Master’s Thesis, Instute of Science and Technology, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal, B.; Deuskar, C. A Better Way to Grow? In Value Capture and Land Policies; Town Planning Schemes, Ed.; English Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/conference-papers/town-planning-schemes-hybrid-land-readjustment-process-ahmedabad (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Cervero, R. Rail transit and joint development: Land market impacts in Washington, DC and Atlanta. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1994, 60, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, E.A.C. Implementing Land Value Capture in a Global South City: Evaluation of the Experience in the City of São Paulo, Brazil. Rev. Bras. De Estud. Urbanos E Reg 2023, 25, e202327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. Land readjustment and metropolitan growth: An examination of suburban land development and urban sprawl in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Prog. Plan. 2000, 53, 217–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Okata, J.; Sorensen, A. Inner-city redevelopment in Tokyo: Conflicts over urban places, planning governance, and neighborhoods. In Living Cities in Japan; Sorensen, A., Funck, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; Chapter 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mouton, M.; Deraëve, S.; Guelton, S.; Poinsot, P. Negotiated windfalls: Mapping how public actors pursue and share land-value capture in Nanterre-la-Folie, France. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, A.G.; Moreno, N.; Vetter, D.M.; Vetter, M.F. The Potential of Land Value Capture for Financing Urban Projects: Methodological Considerations and Case Studies; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başer, V. Effects of Public Transportation Investments on real property: Ordu-Giresun Airport Example. Karadeniz Fen. Bilim. Derg. 2019, 9, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryılmaz, Y. Effects of Transportation Infrastructures on Land Value Increase–Tem Highway Istanbul Anatolian Section Example. Ph.D. Thesis, İstanbul Technical University, İstanbul, Turkey, Unpublished work. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Türkoğlu, K. Possibilities that the Planning Implementation Process, which adopts Urban Land Ownership in three dimensions, can bring to the solution of problems. In Kentsel Toprak Mülkiyetini Üç Boyutlu Olarak Benimseyen Planlama Uygulama Sürecinin, Sorunların Çözümüne Getirebileceği Olanaklar; Bayındırlık ve İskan Bakanlığı Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 1988. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements. United Nations Conference on Human Settlement, Vancouver, Canada. 1976. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/documents/7252The_Vancouver_Declaration_1976.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- OECD. OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-regions-and-cities-at-a-glance-2022_14108660-en.html (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Constitutional Court. Cancellation of the Rule Prescribing the Entire Receipt of the Increased Value as a Result of the Zoning Plan Change. 2023. Available online: https://www.anayasa.gov.tr/tr/haberler/norm-denetimi-basin-duyurulari/imar-plani-degisikligi-sonucunda-artan-degerin-tamaminin-alinacagini-ongoren-kuralin-iptali/ (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Ipek, S.; Engin, R. Place and Significance of Spending Participation Rates in Municipality Incomes: The Case of Çanakkale Province. J. Adm. Sci. 2016, 14, 467–481. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Uzun, B.; Atasoy, B.A.; Celik Simsek, N. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) support for subdivision phase of land readjustment: A case study from Türkiye. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doebele, W.A. Conceptual Models of Land Readjustment. In Land Readjustment: The Japanese System; Minerbi, L., Nakamura, P., Nitz, K., Yanai, J., Eds.; A Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Book: Boston, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Yomralıoğlu, T. Arsa ve Arazi Düzenlemesi için Yeni bir Uygulama Şekli; Harita ve Kadastro Mühendisleri Odası Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 1992; pp. 30–43. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, B.; Celik Simsek, N. Land readjustment for minimizing public expenditures on school lands: A case study of Türkiye. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, J. Self-financing land and urban development via land readjustment and value capture. Habitat. Int. 2014, 44, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, B. Using land readjustment method as an effective urban land development tool in Türkiye. Surv. Rev. 2009, 41, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. Land Readjustment, Urban Planning and Urban Sprawl in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Urban. Stud. 1999, 36, 2333–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, B.; Yıldırım, V.; Çoruhlu, Y.E.; Yıldız, O.; Terzi, F.; Atasoy, B.A. The process of transition to a value-based distribution model in the Turkish land readjustment system. Land Use Policy 2024, 147, 107360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yomralıoğlu, T.; Tüdeş, T.; Uzun, B.; Eren, E. Land Readjustment Implementations in Türkiy. In Proceedings of the XXIVth International Housing Congress, Ankara, Turkey, 27–31 May 1996; pp. 150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Doebele, W.A. Land Readjustment: A Different Approach to Financing Urbanization; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kitay, M.G. Land Acquisition in Developing Countries; Lincoln Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, B. To Investigate highway-property relations in respect of zoning rights and to propose a mode using land readjustment approach. Ph. D. Thesis, Natural and Applied Sciences Geomatic Graduate Program, Karadeniz Technical University, Trabzon, Turkey, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, A.; Çağdaş, V.; Demir, H. An evaluation framework for land readjustment practices. Land Use Policy 2015, 44, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köktürk, E.; Köktürk, E. Yeni Bir İmar Tüzesinin ve En Önemli Öğesi Olarak Arsa Düzenlemelerinde Eşdeğerlik İlkesinin Oluşturulması. 2005. Available online: https://obs.hkmo.org.tr/show-media/resimler/ekler/SY62_105_ek.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Köktürk, E.; Köktürk, E. Arsa Düzenlemesinde Eşdeğerlik İlkesinin Modellenmesi. 2007. Available online: https://www.hkmo.org.tr/resimler/ekler/9ZMU_dbb3fb9a5cd1d5f_ek.doc (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Köktürk, E.; Köktürk, E. Real property Valuation in Land Subdivision Based on Equivalency Principle. Jeodezi Jeoinformasyon Ve Arazi Yönetimi Derg. 2009, 2, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Çağdaş, V. A Development Right-Based Land Readjustment Model. Harit. Derg. 2019, 161, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Selçuk, İ.A. Population Subject in Urban Planning and Mathematical Methods Using for The Forecast of Them. Artium 2014, 2, 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sandroni, P.H. Recent Experience with Land Value Capture in São Paulo, Brazil. Linc. Inst. Land Policy Land Lines 2011, 23, 14–19. Available online: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/recent-experience-land-value-capture-sao-paulo-brazil/ (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Sánchez, F.; Broudehoux, A.M. Mega-events and urban regeneration in Rio de Janeiro: Planning in a state of emergency. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2013, 5, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocalar, A.C.; Eryoldaş, A. Koruma Amaçlı İmar Planı Uygulanan Taşınmazlarda Sınırlandırılan Mülkiyet ve İmar Haklarının Değerlendirilerek Aktarımı. Tasarım Ve Kuram 2010, 9, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Şengezer, B.; Evren, Y.; Ökten, A.N.; Kozaman Som, S. Who Gets ‘What’ in Cities? Questioning İstanbul’s Skyscrapers. Megaron 2009, 4, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A.C.; Pruetz, R.; Woodruff, D. The Tdr Handbook: Designing and Implementing Transfer of Development Rights Programs; Island Press: Washington, WA, USA, 2012; p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Alterman, R. Land use regulations and property values: The "Windfalls Capture” Idea Revisited. In The Oxford Handbook on Urban Economics and Planning; Brooks, N., Donanghy, K., Knapp, G.J., Eds.; Oxford Uni. Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; Chapter 33. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, F.; Meshur, M.C. Problems of land readjustment process in Türkiye. Sci. Res. Essay 2009, 4, 720–727. [Google Scholar]

- Aliefendioglu, Y.; Bazame, R.; Uisso, A.; Tanrivermis, H. Current Practices and Issues of Land Readjustment in Türkiye and the Requirements for Value-based Approach Adoption. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual European Real Property Society Conference, Cergy-Pontoise, France, 3–6 July 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, B.; Yomralıoglu, T. An Alternative Approach to Land Compensation Process to Open Urban Arteries. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2005 and GSDI-8, Cairo, Egypt, 16–21 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanization Council, 2017. (9 November 2017, Ankara). Available online: https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/sehirciliksurasi/icerikler/n-ha--sonuc-b-ld-rges--20180226120835.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Yıldız, N. Arsa ve Arazi Düzenlemesinde Es degerlilik ve Esitlik Ilkelerinin Karsılastırılması. In Proceedings of the Türkiye 1. Bilimsel ve Teknik Kurultayı, Ankara, Turkey, 23–27 February 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ulger, E.; Yıldız, N.; Baz, I.; Ülger, B.C.; Yürekdurmaz, F. Alan Düzenleme Ana Uygulama Esaslarını Belirleme Projesi; Bayındırlık ve Iskan Bakanlıgı, Teknik Arastırma ve Uygulama Genel Müdürlügü: Ankara, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, F.; Ozkan, G.; Yalpır, S. Alan düzenleme ana uygulama esaslarının belirlenmesinde deger esitligini esas alan modellerin uygulaması üzerine bir arastırma. HKMO Jeodezi Jeoinformasyon Ve Arazi Yonet. Derg. 2008, 99, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yomralıoglu, T.; Nisancı, R.; Yıldırım, V. An Implementation of Nominal Asset Based Land Readjustment. In Proceedings of the Strategic Integration of Surveying Services, FIG Working Week 2007, Hong Kong SAR, China, 13–17 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, A. Imar Uygulaması Degerleme çatkısının Olusturulması ve Deger Esaslı Uygulama Modelinin Ülkemize Uyarlanması. Ph.D. Thesis, Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi, Istanbul, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yalpır, S.; Ekiz, M. Esdegerlik esaslı arazi ve arsa düzenlemesinde analitik hiyerarsi prosesin kullanımı. OHÜ Müh. Bilim. Derg. 2017, 6, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağdaş, V.; Linke, H.-J. An institutional analysis of land readjustment in Türkiye. Surv. Rev. 2021, 53, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, N. Investigation of the Effectiveness of Türkiye real property Valuation System. J. Geomat. 2019, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, Y. The Establishment of the real property Regulation and Supervision Agency of Türkiye (RERSAT). Hous. Financ. Int. 2011, 25, 42–51. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1874648 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Tarakci, S.; Turk, S.S. Flexibility in Urban Renewal Practices: The Case of Türkiye. In Proceedings of the Book of Proceedings: Annual AESOP Congress, Spaces of Dialog for Places of Dignity, Lisbon, Portugal, 11–14 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen, D.M.; Tasan-Kok, T. Flexibility in Planning and the Consequences for Public-value Capturing in UK, Spain and the Netherlands. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1097–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.H. Assembling Land for Urban Development: Issues and Opportunities. In Analyzing Land Readjustment Economics, Law, and Collective Action; Hong, Y.H., Needham, B., Eds.; Lincoln Inst of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- Akdeniz, H. Land Readjustment as an Implementation Tool for Urban Plans. J. Urban. Stud. 2022, 37, 1753–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleş, R.; Geray, C.; Emre, C.; Mengi, A. Bringing urban land rent into public use. In Kentsel Toprak Rantının Kamuya Kazandirilmasi; Türkiye Kent Kooperatifleri Merkez Birliği Publishing House: Ankara, Turkey, 1999. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

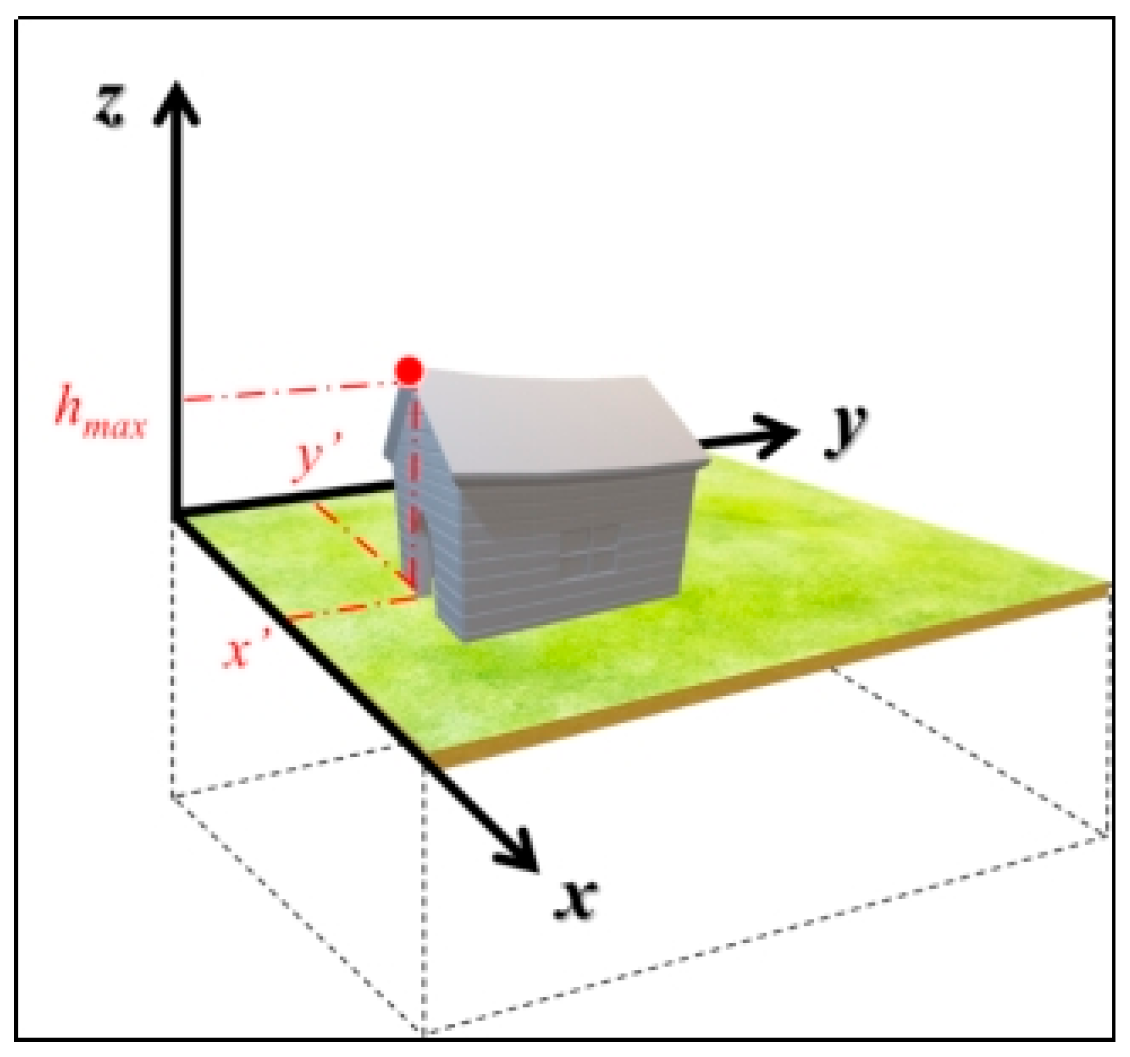

- Celik Simsek, N. Three-Dimensional Model Based Approach in The Management of Real Properties Subjected to Condominium Ownership. Ph.D. Thesis, Natural and Applied Sciences Geomatic Graduate Program, Karadeniz Technical University, Trabzon, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aynural, M.S. Legal Regime of Transfer of Development Rights. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Social Sciences, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hansu, E. Kamu Özel İşbirliği Kapsamında Üst Hakkı; Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- BRS (Brownfields Redevelopment Solutions). A Framework for Land Readjustment and Equitable Redevelopment at the Canal Crossing Redevelopment Area and Case Study; Brownfields Redevelopment Solutions: Medford, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre, G. Replicated or homegrown planning model? The mutual constitution of ideas, interests and institutions in the delivery of a megaproject in Rio de Janeiro. Int. Plan. Stud. 2022, 27, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biderman, C.; Sandroni, P.; Smolka, M. The Case of Faria Lima in São Paulo. Land Lines 2006, 18, 8–13. Available online: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/articles/large-scale-urban-interventions (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Souza, F.F.D.; Ochi, T.; Hosono, A. Land Readjustment: Solving Urban Problems Through Innovative Approach, 1st ed.; Japan International Cooperation Agency Research Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Country (City) | LVC Instruments | Purpose of Use | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | Land leasing | Financing of urban infrastructure | [10] |

| India | Land leasing | Construction of bridge and metro rail systems | [10,15] |

| Transfer of land to the state | Infrastructure and social housing construction | [34] | |

| Betterment levy | Half of infrastructure cost paid by property owners | [34] | |

| USA (Washington) | Joint development | Covering part of the annual income of the transport authority | [35] |

| Brazil (São Paulo) | Certificates of Additional Construction Potential (CEPAC) | Urban infrastructure investments | [36] |

| Japan (Tokyo) | Land readjustment | Using some reserve areas for public use and selling others to fund public infrastructure | [37] |

| Urban redevelopment scheme | Covering consolidation and public facility costs by selling additional development rights | [38] |

| Attribute | Current Status | Post-Plan Status |

|---|---|---|

| Management Unit | Within the boundaries of the municipality | Within the boundaries of the municipality |

| Zoning Plan | None | 1/1000-scale zoning plan |

| Current Legislation | Unplanned Areas Zoning Regulation | Zoning Law No. 3194 with new hLR-related articles |

| Area Size | 330 ha | 330 ha |

| Ownership Status | Private and public ownership | Private and public ownership |

| Land Use | Cultivated/Planted area; Vacant land; Natural area | Residential; Commercial and mixed use; Green space and recreation; Roads and transportation; Waterway (Canal) |

| Planning Principles | None | Canal-oriented urban design; Mixed-use principle (residential, commercial, open spaces); Areas reserved for public service |

| Population Density (gross) | Very low | Medium (approximately 250 persons/ha) |

| Development Rights | Up to 3 storeys; FAR ≤ 1.2 | Flexible according to plan decisions; Minimum FAR = 1.2 |

| Owner of Development Rights | Property owners | Property owners and competent authority (municipality) |

| Cadastral Parcel ID | Parcel Area (m2)— [a] | Contribution Area (m2)—[b] [b] = [a] × CRR | Allocated Area (m2) [c] [c] = [a] − [b] | Building Lot IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 121 | 34,100.00 | 14,599.59 | 19,500.41 | 101/1, 101/2 |

| 122 | 26,181.00 | 11,209.15 | 14,971.85 | 101/3, 101/4, 102/4 |

| 123 | 51,730.00 | 22,147.71 | 29,582.29 | 102/1, 102/2, 102/3 |

| 124 | 40,412.00 | 17,302.01 | 23,109.99 | 103/1, 103/2, 104/1 |

| 125 | 33,731.00 | 14,441.61 | 19,289.39 | 104/1, 106/1, 106/2 |

| 126 | 29,620.00 | 12,681.52 | 16,938.48 | 102/4, 105/1 |

| 127 | 25,255.00 | 10,812.69 | 14,442.31 | 105/2 |

| 128 | 28,346.00 | 12,136.07 | 16,209.93 | 104/2, 104/3 |

| 129 | 24,130.00 | 10,331.03 | 13,798.97 | 105/3, 105/4 |

| 130 | 38,045.00 | 16,288.61 | 21,756.39 | 105/5, 106/3, 106/4 |

| Total | 331,550.00 | 141,950.00 | 189,600.00 |

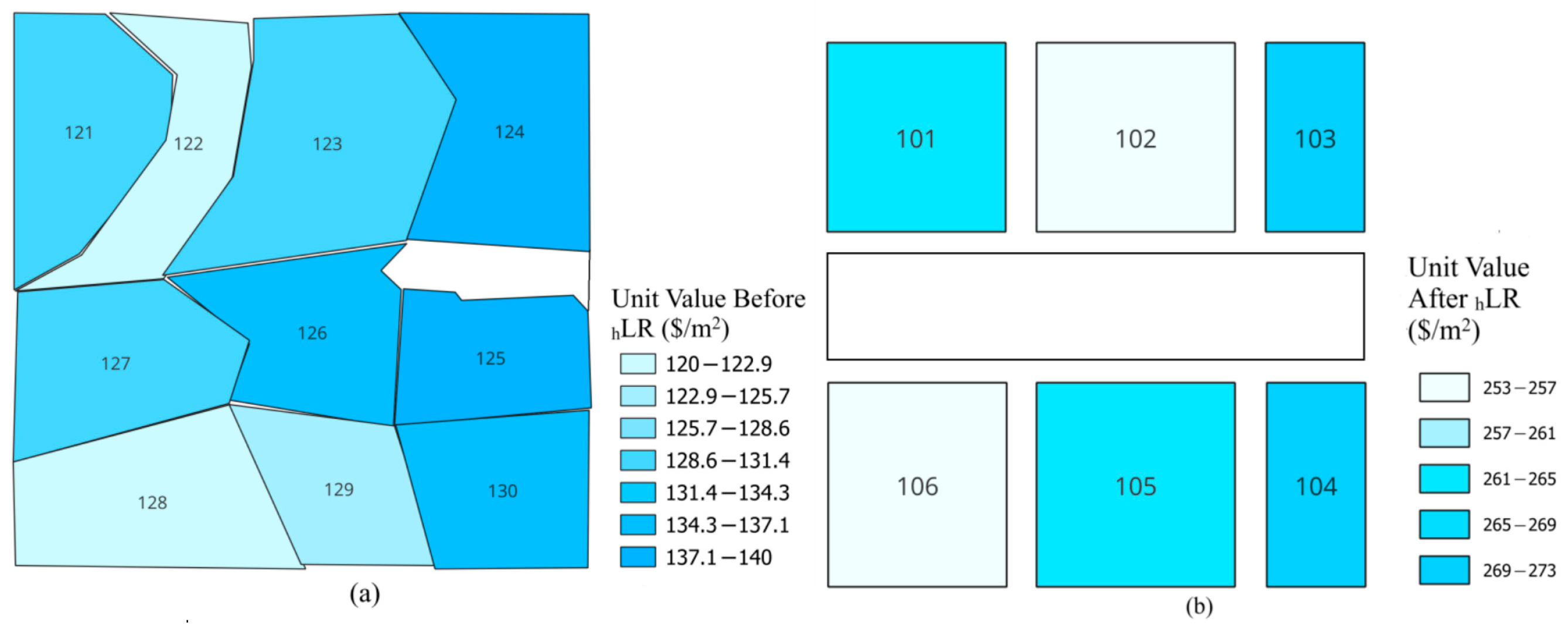

| Parcel ID | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 125 | 126 | 127 | 128 | 129 | 130 |

| Unit Value (USD/m2) | 130 | 120 | 130 | 140 | 140 | 135 | 130 | 120 | 125 | 135 |

| Block ID | 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | 105 | 106 | Total |

| Function | Housing | Housing | Commercial | Commercial | Housing | Housing | — |

| Area (m2) | 34,200 | 38,000 | 19,000 | 20,500 | 41,000 | 36,900 | 189,600 |

| Unit Value (USD/m2) | 263 | 253 | 273 | 273 | 263 | 253 |

| Before the hLR | After the hLR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parcel ID | Parcel Area (m2) | Parcel Market Value (USD) (Area × Unit Value) —[g] | Building Lot ID | Lot Area (m2) —[h] | Unit Value (USD/m2) —[i] | Lot Market Value (USD) (Area × Unit Value) —[j] | New FAR—[k] [k] = ([g] × BDR])/[j] | Total Build Area (m2)—[l] [l] = [k] × [h] |

| 121 | 34,100.00 | 2,216,500 | 101/1 | 9750.00 | 263 | 2,564,358 | 1.04 | 10,140.00 |

| 2,216,500 | 101/2 | 9750.00 | 263 | 2,564,250 | 1.04 | 10,140.00 | ||

| Total (121) | 4,433,000 | - | 19,500.00 | - | 5,128,608 | - | 20,280.00 | |

| 122 | 26,181.00 | 1,542,425 | 101/3 | 7350.00 | 263 | 1,933,274 | 0.96 | 7,056.00 |

| 1,542,425 | 101/4 | 7350.00 | 263 | 1,933,050 | 0.96 | 7,056.00 | ||

| 56,870 | 102/4 | 271.00 | 253 | 68,563 | 1.00 | 271.00 | ||

| Total (122) | 3,141,720 | - | 14,971.00 | - | 3,934,887 | - | 14 383.00 | |

| 123 | 51,730.00 | 2,159,643 | 102/1 | 9500.00 | 253 | 2,403,573 | 1.08 | 10,260.00 |

| 2,159,643 | 102/2 | 9500.00 | 253 | 2,403,500 | 1.08 | 10,260.00 | ||

| 2,405,615 | 102/3 | 10,582.00 | 253 | 2,677,246 | 1.08 | 11,428.56 | ||

| Total (123) | 6,724,900 | - | 29,582.00 | - | 7,484,319 | - | 31,948.56 | |

| 124 | 40,412.00 | 2,325,745 | 103/1 | 9500.00 | 273 | 2,593,770 | 1.08 | 10,260.00 |

| 2,325,745 | 103/2 | 9500.00 | 273 | 2,593,500 | 1.08 | 10,260.00 | ||

| 1,006,191 | 104/1 | 4110.00 | 273 | 1,122,030 | 1.08 | 4438.80 | ||

| Total (124) | 5,657,680 | - | 23,110.00 | - | 6,309,300 | - | 24,958.80 | |

| 125 | 33,731.00 | 44,070 | 104/1 | 180.00 | 273 | 49,246 | 1.07 | 192.60 |

| 2,339,135 | 106/1 | 9554.00 | 253 | 2,417,162 | 1.16 | 11,082.64 | ||

| 2,339,135 | 106/2 | 9554.00 | 253 | 2,417,162 | 1.16 | 11,082.64 | ||

| Total (125) | 4,722,340 | - | 19,288.00 | - | 4,883,570 | - | 22,357.88 | |

| 126 | 29,620.00 | 1,923,333 | 102/4 | 8147.00 | 253 | 2,061,312 | 1.12 | 9124.64 |

| 2,075,367 | 105/1 | 8791.00 | 263 | 2,312,033 | 1.08 | 9494.28 | ||

| Total (126) | 3,998,700 | - | 16,938.00 | - | 4,373,345 | - | 18,618.92 | |

| 127 | 25,255.00 | 3,283,150 | 105/2 | 14,442.00 | 263 | 3,798,328 | 1.04 | 15,019.68 |

| 128 | 28,346.00 | 1,700,760 | 104/2 | 8105.00 | 273 | 2,212,919 | 0.92 | 7456.6 |

| 1,700,760 | 104/3 | 8105.00 | 273 | 2,212,665 | 0.92 | 7456.6 | ||

| Total (128) | 3,401,520 | - | 16,210.00 | - | 4,425,584 | - | 14,913.2 | |

| 129 | 24,130.00 | 1,508,125 | 105/3 | 6899.00 | 263 | 1,814,692 | 1.00 | 6899.00 |

| 1,508,125 | 105/4 | 6899.00 | 263 | 1,814,437 | 1.00 | 6899.00 | ||

| Total (129) | 3,016,250 | - | 13,798.00 | - | 3,629,129 | - | 13,798.00 | |

| 130 | 38,045.00 | 937,030 | 105/5 | 3969.00 | 263 | 1,043,950 | 1.08 | 4286.52 |

| 2,099,523 | 106/3 | 8893.00 | 253 | 2,249,929 | 1.12 | 9960.16 | ||

| 2,099,523 | 106/4 | 8893.00 | 253 | 2,249,929 | 1.12 | 9960.16 | ||

| Total (130) | 5,136,075 | - | 21,755.00 | - | 5,543,808 | - | 24,206.84 | |

| TOTAL | 43,515,335 | - | 189,600.00 | - | 49,510,878 | - | 200,484.88 | |

| Block ID | Block Area (m2)—(m) | Total Build Area (FAR = 1.6)—(n) (n) = FAR × (m) | Area Allocated to Lots (m2)—(o) | Area Retained by Authority (m2)—(p) (p) = (n) − (o) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | 34,200.00 | 54,720.00 | 34,392.00 | 20,328.00 |

| 102 | 38,000.00 | 60,800.00 | 41,344.20 | 19,455.80 |

| 103 | 19,000.00 | 30,400.00 | 20,520.00 | 9880.00 |

| 104 | 20,500.00 | 32,800.00 | 19,544.60 | 13,255.40 |

| 105 | 41,000.00 | 65,600.00 | 42,598.48 | 23,001.52 |

| 106 | 36,900.00 | 59,040.00 | 42,085.60 | 16,954.40 |

| Total | 189,600.00 | 303,360.00 | 200,484.88 | 102,875.12 |

| Before hLR | After hLR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

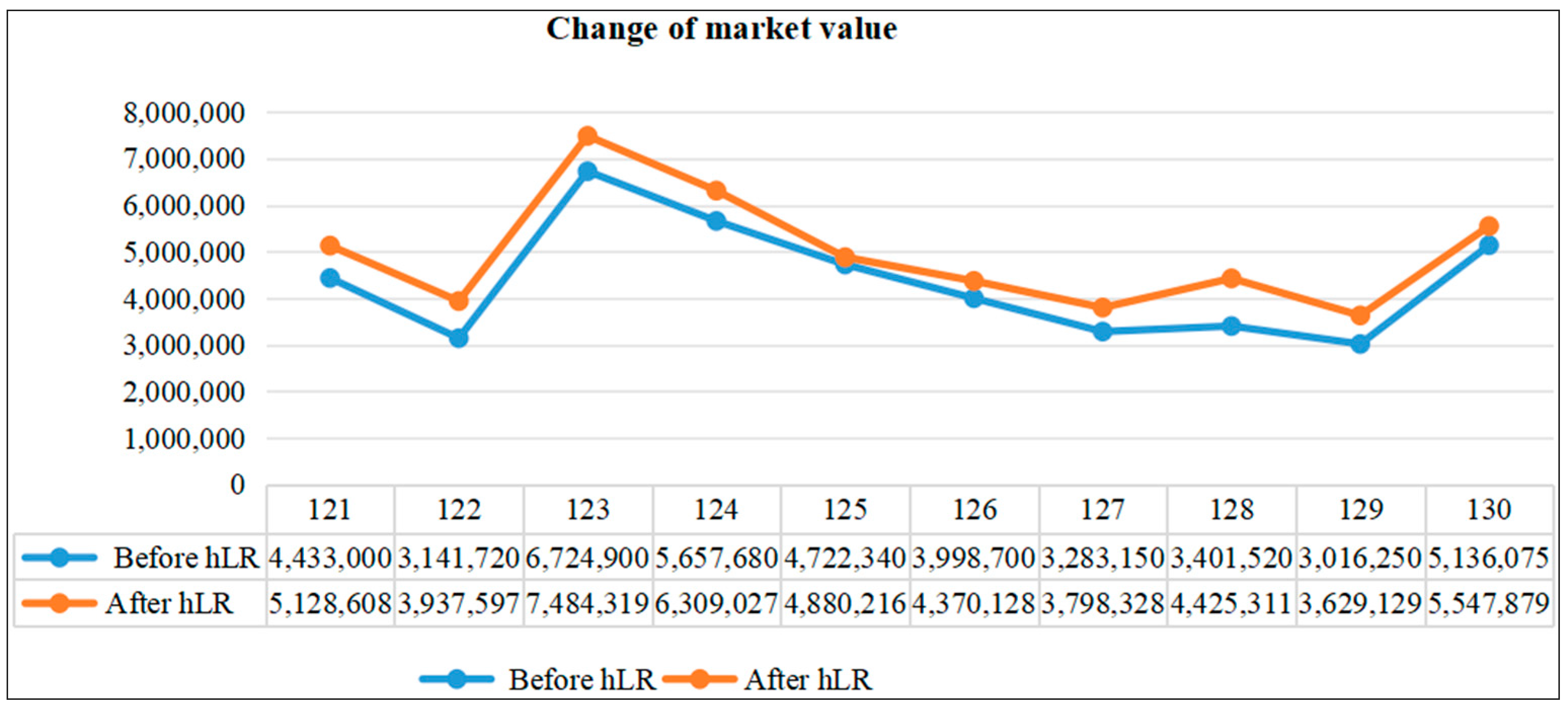

| Cadastral Parcel ID | Pre-hLR Area (m2)—(t) | Pre-hLR Unit Value (USD/m2)—(q) | Pre-hLR Market Value (USD) (u) = (t) × (q) | Post-hLR Lot Area (m2)—(v) | Post-hLR Unit Value (USD/m2)—(r) | Post-hLR Market Value (USD) (w) = (v) × (r) |

| 121 | 34,100.00 | 130 | 4,433,000 | 19,500.00 | 263 | 5,128,608 |

| 122 | 26,181.00 | 120 | 3,141,720 | 14,972.00 | 263 | 3,937,597 |

| 123 | 51,730.00 | 130 | 6,724,900 | 29,582.00 | 253 | 7,484,319 |

| 124 | 40,412.00 | 140 | 5,657,680 | 23,110.00 | 273 | 6,309,027 |

| 125 | 33,731.00 | 140 | 4,722,340 | 19,289.00 | 253 | 4,880,216 |

| 126 | 29,620.00 | 135 | 3,998,700 | 16,938.00 | 258 | 4,370,128 |

| 127 | 25,255.00 | 130 | 3,283,150 | 14,442.00 | 263 | 3,798,328 |

| 128 | 28,346.00 | 120 | 3,401,520 | 16,210.00 | 273 | 4,425311 |

| 129 | 24,130.00 | 125 | 3,016,250 | 13,799.00 | 263 | 3,629,129 |

| 130 | 38,045.00 | 135 | 5,136,075 | 21,756.00 | 255 | 5,547,879 |

| Total | 331,550.00 | 43,515,335 | 189,600.00 | 49,510,542 | ||

| Cadastral Parcel ID | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 125 | 126 | 127 | 128 | 129 | 130 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit value | Coefficient (s) = (r)/(q) | 2.02 | 2.19 | 1.94 | 1.95 | 1.80 | 1.91 | 2.02 | 2.28 | 2.10 | 1.88 |

| Increase (%) (t) = [[(r) − (q)]/(q)] × 100 | 102.3 | 119.0 | 94.62 | 95.00 | 80.71 | 91.25 | 102.3 | 127.50 | 110.40 | 88.76 | |

| Market value | Coefficient (x) = (w)/(u) | 1.16 | 1.25 | 1.11 | 1.12 | 1.03 | 1.09 | 1.16 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 1.08 |

| Increase (%) (y) = [[(w) − (u)]/(u)] × 100 | 15.69 | 25.33 | 11.29 | 11.51 | 3.34 | 9.29 | 15.69 | 30.10 | 20.32 | 8.02 |

| Parcel ID | 121 | 122 | 123 | 124 | 125 | 126 | 127 | 128 | 129 | 130 |

| Pre-hLR FAR | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 |

| Post-hLR FAR | 1.04 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.16 | 1.1 | 1.04 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.11 |

| FAR Coefficient (Post/Pre) | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.92 |

| FAR Decrease (%) | 13.3 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 3.3 | 8.3 | 13.3 | 23.3 | 16.7 | 7.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simsek, N.C.; Atasoy, B.A.; Uzun, S. A Hybrid Model for Land Value Capture in Sustainable Urban Land Management: The Case of Türkiye. Land 2025, 14, 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081570

Simsek NC, Atasoy BA, Uzun S. A Hybrid Model for Land Value Capture in Sustainable Urban Land Management: The Case of Türkiye. Land. 2025; 14(8):1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081570

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimsek, Nida Celik, Bura Adem Atasoy, and Semih Uzun. 2025. "A Hybrid Model for Land Value Capture in Sustainable Urban Land Management: The Case of Türkiye" Land 14, no. 8: 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081570

APA StyleSimsek, N. C., Atasoy, B. A., & Uzun, S. (2025). A Hybrid Model for Land Value Capture in Sustainable Urban Land Management: The Case of Türkiye. Land, 14(8), 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081570