Exploring Pedestrian Satisfaction and Environmental Consciousness in a Railway-Regenerated Linear Park

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Walking as a Human Condition

2.2. Homo Faber

2.3. Walking in Urban Nature

2.4. Gyeongui Line Forest Park: A Repurposed Railway

3. Methodology

3.1. Walking as a Method

3.2. YouTube Videos

3.3. Generalized Additive Models (GAMs)

4. Results

4.1. Themes of Walking Videos

4.2. GAMs for Statistical Triangulation

4.2.1. Description of GAM Models

4.2.2. Comparison of GAMs

4.3. Summary of Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Parameters | Items (5-Point Likert Scale) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Pedestrian provision | Accessibility | Park has good accessibility. |

| Connectivity | Park has good connectivity of walking paths. | ||

| Path variety | The walking paths are composed of various materials and forms. | ||

| Rest facility | The walking paths are equipped with rest facilities such as benches and shade canopies. | ||

| Surrounding environment | Green nature | Park exposes visitors to green natural elements such as trees, grass, and lawns. | |

| Water element | Park exposes visitors to natural water elements such as streams and ponds. | ||

| Habitat conservation | Park functions as a habitat for small animals and insects. | ||

| History display | Park preserves and exhibits the history of the Gyeongui Line. | ||

| Art element | Park provides exposure to artistic elements such as sculptures. | ||

| F&B access | Park offers access to various cafés and restaurants. | ||

| Age inclusiveness | Park allows people of various age groups to enjoy it together. | ||

| Mediation | Pedestrian satisfaction | Park provides a pedestrian-friendly environment. | |

| Response | Environmental sensitivity | Walking experiences in Gyeongui Line Forest Park help restore environmental sensitivity. | |

| Model 1 | Description | Predicting PE from PP and PE |

| Structure | PSi = β0 + f1(PPi) + f2(SEi) + εi (1) | |

| Model 2 | Description | Predicting total effect of PP and SE on ES |

| Structure | ESi = β0 + f3(PPi) + f4(SEi) + εi (2) | |

| Model 3 | Description | Mediation role of PS by including it as an additional smooth term |

| Structure | ESi = β0 + f5(PPi) + f6(SEi) + f7(PSi) + εi (3) | |

| PPi: Pedestrian provision score SEi: Surrounding environment score PSi: Pedestrian satisfaction ESi: Environmental sensitivity fk (·): Smooth function (thin-plate spline) εi (k): Residual variance not captured by the model’s smooth terms | ||

References

- Azevedo, A.; Freire, F.; Silva, L.; Carapinha, A.; Matos, R. Tourists’ assessment of economic value, benefits and negative impacts of pedestrian walkways: Case-studies of the Paiva River (Arouca) and the Mondego River (Guarda) in Portugal. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 46, 100769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Chung, W.J.; Jeong, C. Exploring sentiment analysis and visitor satisfaction along urban liner trails: A case of the Seoul Trail, South Korea. Land 2024, 13, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Sustainability. In Routledge Handbook of Global Ethics; Moellendorf, D., Widdows, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 387–399. [Google Scholar]

- Modesto, A.; Kamenečki, M.; Tomić Reljić, D. Application of suitability modeling in establishing a new bicycle–pedestrian path: The case of the abandoned Kanfanar–Rovinj railway in Istria. Land 2021, 10, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, H. The Human Condition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Gros, F. A Philosophy of Walking, 2nd ed.; Howe, J., Translator; Verso Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Poteko, K.; Doupona, M. In praise of urban walking: Towards understanding of walking as a subversive bodily practice in neoliberal space. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2022, 57, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnit, R. Wanderlust: A History of Walking; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Canovan, M. Introduction. In The Human Condition; Arendt, H., Ed.; Original Work Published 1958; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; pp. xix–xxxii. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Jackson, T. Post Growth: Life After Capitalism; Polity Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Harrison, R.P. Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Final Report on the Cultural Impact Assessment of the Gyeongui Line Forest Park Development and Operation Project. 2019. Available online: https://lib.seoul.go.kr/search/detail/CATTOT000001383598 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Hutniczak, A.; Urbisz, A.; Watoła, A. The socio-economic importance of abandoned railway areas in the landscape of the Silesian Province (southern Poland). Environ. Socio Econ. Stud. 2023, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurković, Ž.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Lovoković, D. Railway corridors in Croatian cities as factors of sustainable spatial and cultural development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić, D.; Vukoičić, D.; Ivanović, M.; Nikolić, M.; Milentijević, N.; Mihajlović, L.; Petrović, D. Transformation of abandoned railways into tourist itineraries/routes: Model of revitalization of marginal rural areas. Land 2024, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsall, H.; Pierce, J.; Campbell, L.K. Walking as a method for epistemic justice in sustainability. Ambio 2024, 53, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springgay, S.; Truman, S.E. Walking Methodologies in a More-than-Human World: WalkingLab; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijnen, I.; Stewart, E.; Espiner, S. On the move: The theory and practice of the walking interview method in outdoor education research. Ann. Leis. Res. 2022, 25, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, H. Walking: New forms and spaces for studies of pedestrianism. In Geographies of Mobilities: Practices, Spaces, Subjects; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.; Lawhon, M. Walking as method: Toward methodological forthrightness and comparability in urban geographical research. Prof. Geogr. 2015, 67, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.J.; Waggener, L.; Kiely, S.C.; Hedge, A. Postoccupancy evaluation of a neighborhood concept redesign of an acute care nursing unit in a planetree hospital. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2022, 15, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modell, S. Triangulation between case study and survey methods in management accounting research: An assessment of validity implications. Manag. Acc. Res. 2005, 16, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lättman, K.; Welsch, J.; Otsuka, N.; van der Vlugt, A.L.; De Vos, J.; Prichard, E. Walking travel satisfaction—A comparison of three European cities. J. Urban. Mob. 2025, 7, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-I.; Jeong, C. Influence of perceived restorativeness on recovery experience and satisfaction with walking tourism: A multiple-group analysis of daily hassles and the types of walking tourist attractions. Land 2025, 14, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanshahi, G.; Soltani, A.; Roosta, M.; Askari, S. Walking as soft mobility: A multi-criteria GIS-based approach for prioritizing tourist routes. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1080–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayode, I.O.; Chau, H.-W.; Jamei, E. Barriers affecting promotion of active transportation: A study on pedestrian and bicycle network connectivity in Melbourne’s west. Land 2024, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radics, M.; Christidis, P.; Alonso, B.; dell’Olio, L. The X-minute city: Analysing accessibility to essential daily destinations by active mobility in Seville. Land 2024, 13, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Yin, Y.; Ma, D. Evaluating the Equity of Urban Streetscapes in Promoting Human Health—Taking Shanghai Inner City as an Example. Land 2024, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Li, C. Attraction and retention green place images of Taipei City. Forests 2024, 15, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.H. New materialism: An ontology for the Anthropocene. Nat. Resour. J. 2019, 59, 251–280. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26800037 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Bunting, B.S. Nature as ecology: Toward a more constructive ecocriticism. J. Ecocriticism 2015, 7, 1–16. Available online: https://ojs.unbc.ca/index.php/joe/article/view/469 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Duffy, M.; Gallagher, M.; Waitt, G. Emotional and affective geographies of sustainable community leadership: A visceral approach. Geoforum 2019, 106, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, Q.; Zhu, Y. Urban park system on public health: Underlying driving mechanism and planning thinking. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1193604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Baran, P.K. Urban park pathway design characteristics and senior walking behavior. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 21, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Y.G. An Urban Typological Approach of Gyeongui-Line Forest Park Constructionproject in Seoul. J. Korean Urban Manag. Assoc. 2022, 35, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.-H. Study on Autogenous Urban Regeneration by Park: A Case of Gyeongui Line Forest Park. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. Available online: https://www.riss.kr/link?id=T14738677 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Park, J.Y. A Study on the Urban Space Transition by the Effect of Urban Regeneration Using Old Infrastructure Facility. Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10371/124363 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Kim, J.-E. Importance-Performance Analysis of Design Elements of Gyeongui-Line Forest Park. Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. Available online: https://repository.hanyang.ac.kr/handle/20.500.11754/76027 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Pan, H.-S.; Lee, S.-H. A study on the influence of spatial design in urban regeneration parks on user activation—Focused on Gyeongui line Forest Park and Seoullo 7017. Urban Des. J. 2024, 6, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquijo, M. Walking ethnography: The polyphonies of space in an urban landscape. J. Cult. Geogr. 2023, 40, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, A.; Legewie, N. Video Data Analysis: How to Use 21st-Century Video in the Social Sciences; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chenail, R.J. YouTube as a qualitative research asset: Reviewing user generated videos as learning resources. Qual. Rep. 2016, 13, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, S.; Sabetti, J.; Ferrari, M. Performing qualitative content analysis of video data in social sciences and medicine: The visual-verbal video analysis method. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781498728331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Leung, S.O. Can Likert scales be treated as interval scales?—A simulation study. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2017, 43, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H. Effects of particulate matter (PM 10) on tourism sales revenue: A generalized additive modeling approach. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, G.; Wood, S.N. Practical variable selection for generalized additive models. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2011, 55, 2372–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.A. The power of slowness: Governmentalities of Olle walking in South Korea. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2022, 47, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremia, M.; Toma, L.; Sanduleac, M. The smart city concept in the 21st century. Procedia Eng. 2017, 181, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Certeau, M. Walking in the city. In The Practice of Everyday Life; Rendall, S., Translator; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1984; pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Loland, S. The poetics of everyday movement: Human movement ecology and urban walking. J. Philos. Sport 2021, 48, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, S. Differences in park walking, comparing the physically inactive and active groups: Data from mHealth monitoring system in Seoul. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isham, A.; Gatersleben, B.; Jackson, T. Flow activities as a route to living well with less. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 431–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodev, Y.; Zhiyanski, M.; Glushkova, M.; Shin, W.S. Forest welfare services—The missing link between forest policy and management in the EU. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.Y. Comparison of Development Process of Forest Recreation Policy in Korea, China and Japan. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. Available online: http://dcollection.snu.ac.kr/common/orgView/000000158131 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Gardens Everywhere You Go! 1000 Places to Be Created by 2026. 2023. Available online: https://mediahub.seoul.go.kr/archives/2010493 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

| Description | Visual and Verbal Content | Coded Themes | Researcher’s Interpretation | |

| Video 1 | Duration: 9:51 Date: May/11/2022 Verbal data source: Conversation Language: Korean | Visual content: -Walking: cement concrete pavement -Surrounding: greenery, 4-5 story houses, cafés, and restaurants Verbal content: I like this place because of the abundance of cafés and restaurants nearby (2:00). Transforming this area into a linear park has been the most effective approach for urban regeneration (3:00). The park continues to improve naturally over time without direct intervention as the trees mature and the landscape evolves (3:50). There are two major advantages of a linear park: First, unlike square parks, linear parks maximize interface with adjacent residential catchment. Second, they enhance social cohesion by dissolving physical and symbolic boundaries between neighborhoods (4:50). Architectural diversity is observed in relation to the varying tree heights and the spatial width of the greenspace (8:40). | F&B amenities. Architectural diversity. Accessibility. Social cohesion. | The linear park is described as an optimal model for urban regeneration, as it maximizes accessibility and fosters a sense of community. However, the emphasis of the linear park’s beneficial effects is predominantly on human beings. |

| Video 2 | Duration: 39:52 Date: August/28/2022 Verbal data source: Text narration Language: English | Visual content: -Walking: cement concrete pavement, crushed stone pavement, Sogang Sky Bridge made of wooden planks, bicycle parking facilities, sunshades and benches, disruption of greenspace continuity due to vehicular roads and intersection -Surrounding: greenery, streams and ponds, blue sky, sculptures referencing railroad history and book alley, railroad tracks, high-rise buildings and underdeveloped housing, cafes and restaurants, international tourists, passers-by of all ages—seniors, youth, infants in strollers, elderly women conversing in the pavilion, individuals resting near the pond, and children playing in the area Verbal content: I think this section of the railroad is the most popular among both children and adults (20:49). It’s heartwarming to see birds drinking water here (20:12). It’s wonderful that people can not only view but also touch the water nearby (37:11). | Historic features from the former railway. Abundant natural assets, especially water and small animals. Generational integration from infants to the elderly. | The linear park offers varied walking experiences through changing pavement types, such as crushed stone and plaza areas. Walking videos capture the integration of natural and built environments, reflecting a harmonious respect for ecological elements and vibrant urban experiences. |

| Video 3 | Duration: 9:51 Date: November/06/2022 Verbal data source: Audio narration Language: Korean | Visual content: -Walking: cement concrete pavement, crushed stone pavement, plaza, benches and pavilion, disruption of greenspace continuity due to vehicular roads, intersections, and apartment complex parking lots -Surrounding: dense tree canopy, red maple trees (Quercus rubra), water channels, railroad tracks and historical sculpture Verbal content: Walking one or two subway stops along this path allows for both light exercise and enjoyment of nature (1:28). As a linear park, it is ideal for strolling (2:56). A linear park can serve as an ecological corridor, providing habitats for flora and fauna and offering ecosystem services for other species (2:45). Since this area repurposed an abandoned railway, its development did not cause displacement of residents (3:26). The forest offers immeasurable psychological and environmental benefits to humans (3:42). It is hoped that the fragmented green corridor will be improved in the future through the installation of a green highway (3:53). With the integration of railway tracks, water channels, sculptures, and red maple trees, the landscape evokes a sense of exotic scenery (5:09). The inclusion of plaza-like open spaces creates spatial variety (5:35). Further improvement in the connectivity of green spaces is desired (6:35). | Ecosystem services. Equitable urban regeneration. Exotic walking ambiance. Physical engagement and health improvement. Cultural significance rooted in the site’s historical legacy. | A linear park provides valuable ecosystem services by supporting biodiversity and facilitating natural processes within the urban context. Through its diverse spatial experiences and scenic elements, the park offers a unique and exotic walking environment. The video emphasizes the importance of ecosystem services and advocates for improved continuity of greenspace. |

| Video 4 | Duration: 10:29 Date: January/04/2021 Verbal data source: Text narration Language: Korean | Visual content: -Walking: cement concrete pavement -Surrounding: non-green vegetated areas such as reed fields, a mix of built environments, including apartment complexes, multi-unit dwellings, undeveloped single-story houses, and clusters of high-rise buildings, railroad-themed sculptures, small independent bookstores, Hangeul-inspired public art installation Verbal content: This is a park well-suited for a two-hour walk. When trains were still running, the sound of bells signaled their approach, which led to the nickname “Ttaeng-Ttaeng Street” (6:30). | Suitable environment for hours of walking. Cultural significance rooted in the site’s historical legacy. | In winter, the park appears visually barren, with natural elements significantly diminished. |

| Models | Parametric Terms | Smooth Terms (Applying Thin-Plate Splines) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAM Coefficient | Terms | edf | F | p-Value | |

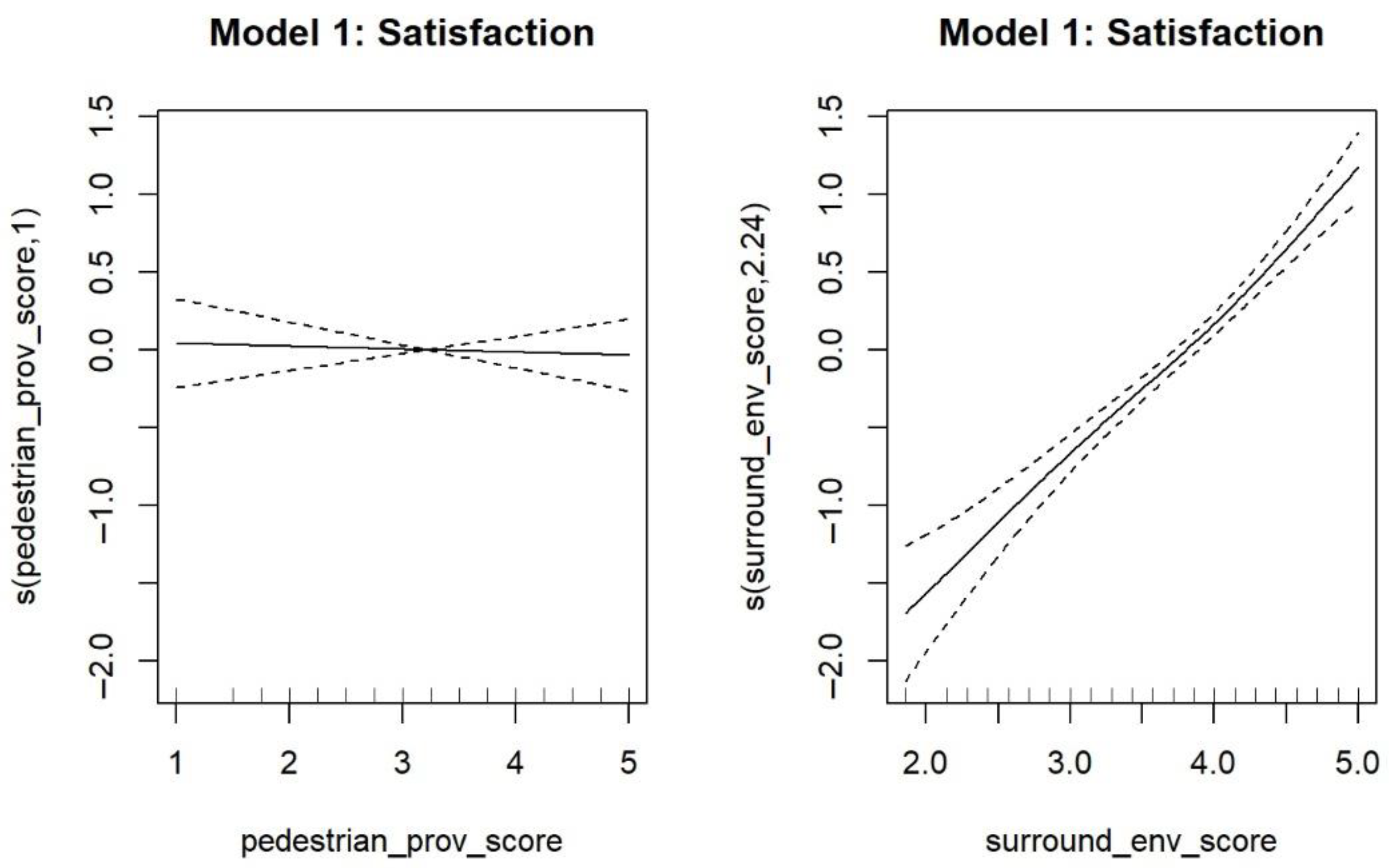

| Model 1: Predictors to mediator | Intercept: 3.26 Deviation explained: 66.1% | Pedestrian provision | 1.00 | 0.09 | 0.77 |

| Surrounding environment | 2.23 | 52.13 | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2: Predictors to total effect | Intercept: 3.77 Deviation explained: 64% | Pedestrian provision | 1 | 0.19 | 0.89 |

| Surrounding environment | 1 | 127.99 | <0.001 | ||

| Model 3: Predictors to total effect with mediation | Intercept: 3.77 Deviation explained: 70.2% | Pedestrian provision | 1 | 0.07 | 0.80 |

| Surrounding environment | 1 | 26.76 | <0.001 | ||

| Pedestrian satisfaction | 1 | 32.24 | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, L.; Jeong, C. Exploring Pedestrian Satisfaction and Environmental Consciousness in a Railway-Regenerated Linear Park. Land 2025, 14, 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071475

Kim L, Jeong C. Exploring Pedestrian Satisfaction and Environmental Consciousness in a Railway-Regenerated Linear Park. Land. 2025; 14(7):1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071475

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Lankyung, and Chul Jeong. 2025. "Exploring Pedestrian Satisfaction and Environmental Consciousness in a Railway-Regenerated Linear Park" Land 14, no. 7: 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071475

APA StyleKim, L., & Jeong, C. (2025). Exploring Pedestrian Satisfaction and Environmental Consciousness in a Railway-Regenerated Linear Park. Land, 14(7), 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071475