1. Introduction

Land tenure security represents a significant challenge in developing nations, where numerous individuals, communities, and enterprises do not possess clear and secure access to the land, resources, and property essential for their livelihoods [

1]. Lack of land tenure security in various regions exacerbates poverty and contributes to social instability and conflict. Land tenure reform is a multifaceted and protracted process, yet it is crucial for the actualization of human rights, poverty reduction, economic advancement, and sustainable development. The community possesses houses and land as economic resources, like houses and land, but they often lack the necessary titles or legal documentation to rent or mortgage their property or to substantiate ownership. This leads to insecure property rights [

2]. The lack of legal and practical security of tenure substantially impedes protection against involuntary removal or eviction [

3], thereby exposing vulnerable populations, including residents of informal settlements, to potential human rights violations [

4].

Informal settlements are prevalent globally, particularly in developing nations experiencing rapid urbanization [

5,

6,

7], resulting in vertical growth in some cities [

8] and exceeding the carrying capacity in specific urban regions. Informal settlements are residential areas defined by a lack of tenure security on land or housing, including illegal occupancy and informal rental housing [

9,

10]. Their presence is usually on land not designated for residential use in the city’s master plan [

11]. Urban informal settlements are characterized by a lack of willingness to invest in housing, high population density, low-quality housing, and illegal tenure; however, the most significant characteristic is the absence of tenure security [

12]. Prior research [

13,

14] indicates that inadequate informal settlement practices, insufficient supportive policies for the urban poor, and rising land prices constitute the primary challenges associated with these settlements. Consequently, addressing problems in and with informal urban settlements is often considered separate from addressing conventional urban challenges [

15]. In many countries, the urban impoverished frequently have little other alternative but to inhabit informal settlements, as the private developers primarily develop property and houses for affluent and middle-class populations [

16]. Tenure informality is a significant characteristic of informal settlements where land tenure is held informally, providing insufficient protection for occupants [

17]. The absence of precise information necessary for planning and designing policies and programs aimed at upgrading and regularizing informal settlements is attributed to exclusion from the formal land management system [

18,

19].

Informal settlements tend to develop into dense mixed residential and small business areas over time. Often, land is held as a mix of various forms of urban tenure practices, including ‘Waqf’ lands. ‘Waqf land tenure’ originates from Islamic law and refers to land that is usually donated to a community for religious, social, or philanthropic use. Once qualified as Waqf land, it can no longer be sold, inherited, or transferred by the original owner or any land user. The community has to decide on its use. Waqf land is governed by a social institution for collective benefit, and the principles are comparable to common land law.

If informal settlements are constructed on

Waqf land, the community affiliated with the religious, social, or philanthropic purpose can resolve disputes using non-litigation methods such as negotiation and alternative settlement channels [

20]. Informal settlements typically lack formal authority, resulting in uncontrolled development of improvised homes [

21], a similar situation also observed in informal settlements on

Waqf land. Furthermore,

Waqf lands often suffer from mismanagement because they are excluded from the commercial land market [

22], which may lead to illegal occupancy for settlement purposes. Informal settlements have emerged on

Waqf property due to underutilization or neglect, making it appealing to informal settlers seeking housing alternatives. The complexities surrounding

Waqf land ownership and the challenges in formal development contribute to the proliferation of informal communities on this property, leading to “land donation” for the community’s benefit with a rent system [

23].

Research on

Waqf land encompasses various domains, such as the development of idle

Waqf land [

24], the establishment of

Waqf-based financial institutions [

25,

26], the utilization of cash

Waqf for financing construction projects [

27], and the development of

Waqf land via a joint venture model [

28]. Earlier studies have primarily focused on how and why

Waqf land developed as a financial resource, yet have not considered how a

Waqf land tenure arrangement could influence or affect public housing or settlement needs. Nonetheless, several relevant studies on

Waqf land in Indonesia and other countries exist. These analyze, amongst other factors, which types of housing and urban informal settlements have emerged in urban ‘kampungs’ (traditional urban settlements) in Surabaya, Indonesia [

29]; how

Waqf cooperatives in Karachi, Pakistan, finance housing [

30]; which sharing options exist for public and social housing on

Waqf land in Bangkok, Thailand [

23]; where and why illegal settlements emerge on

Waqf land in Egypt [

10]; how disputes are addressed on

Waqf property in settlement areas in Indonesia [

20]; and how

Waqf land created “

Waqf space” in urban settlements in Semarang, Indonesia [

31].

Waqf space denotes a spatial-cultural entity, generated and developed by religious practices. Still, these studies do not address the transformation of

Waqf land with regard to urban tenures or its potential as an alternative for settlement provision for the urban poor, as this article does.

In Indonesia,

Waqf is primarily practiced in a religious context or founded on mutual trust. This requirement ultimately results in the land being devoid of a legal foundation. Consequently, if issues arise regarding the ownership of

Waqf land in the future, challenges will emerge, especially concerning proof [

20]. Given the challenges associated with the urban poor’s possession of

Waqf land, this research proposes the following research question: ‘How has the management of

Waqf land been transformed from informal to formal settlement, and to what extent has responsible management of

Waqf land been achieved?” Our study examines the history and transformation of

Waqf land management and the agreements established by the managing party, representing the Kauman Grand Mosque as the owner, with the community. Further, this study evaluates the effectiveness of responsible

Waqf land management by applying the 8R framework, adapted from [

32,

33]. The reason for using the 8R framework is its comprehensive structure of R components, which contain all the necessary characteristics for this study. By utilizing the 8R framework, a comprehensive analysis of each R component is provided, along with the challenges and issues faced by the community regarding the utilization and management of

Waqf land in the study area. This study employs a critical lens to examine the social and economic roles of the community, adding to an emerging field of urban studies that emphasizes the unique function of

Waqf land in fostering sustainable urban informal settlements.

2. Levelling Tenure Security on Waqf Land

Urbanization in developing nations is marked by the proliferation of informal settlements and the underutilization of property, especially

Waqf properties, an Islamic endowment.

Waqf land, historically allocated for religious or charity purposes [

34], frequently stays undeveloped due to legal intricacies and governance issues. Simultaneous rapid urban growth and the inadequacy of formal systems to provide housing needs have resulted in the emergence of informal settlements, including on

Waqf land. Occupants may reside on

Waqf land through informal or unauthorized means, creating conflicts between preservation of endowment principles and community needs. These informal areas occasionally lack legal acknowledgment and are characterized by insecure tenure and insufficient services.

Currently, however, most

Waqf lands are poorly managed or legally encumbered, resulting in inefficient land use. Poorly managed

Waqf land attracts people with limited or no access to land for housing, leading to the emergence of informal settlements on such lands. Informal settlements emerge from the disparity between swift urban expansion and the ability of formal housing systems to serve low-income groups. Historically regarded as unlawful and spontaneous, these settlements are now recognized as alternative urban configurations developed through grassroots initiatives [

15]. Informal settlements typically consist of self-constructed housing, inadequate infrastructure, and unclear land tenure. They also demonstrate community resilience and innovation. Yiftachel [

35] describes informality as existing in a “gray space,” which is characterized by its status as neither fully legal nor entirely illegal, emphasizing the state’s role in either legitimizing or marginalizing these areas.

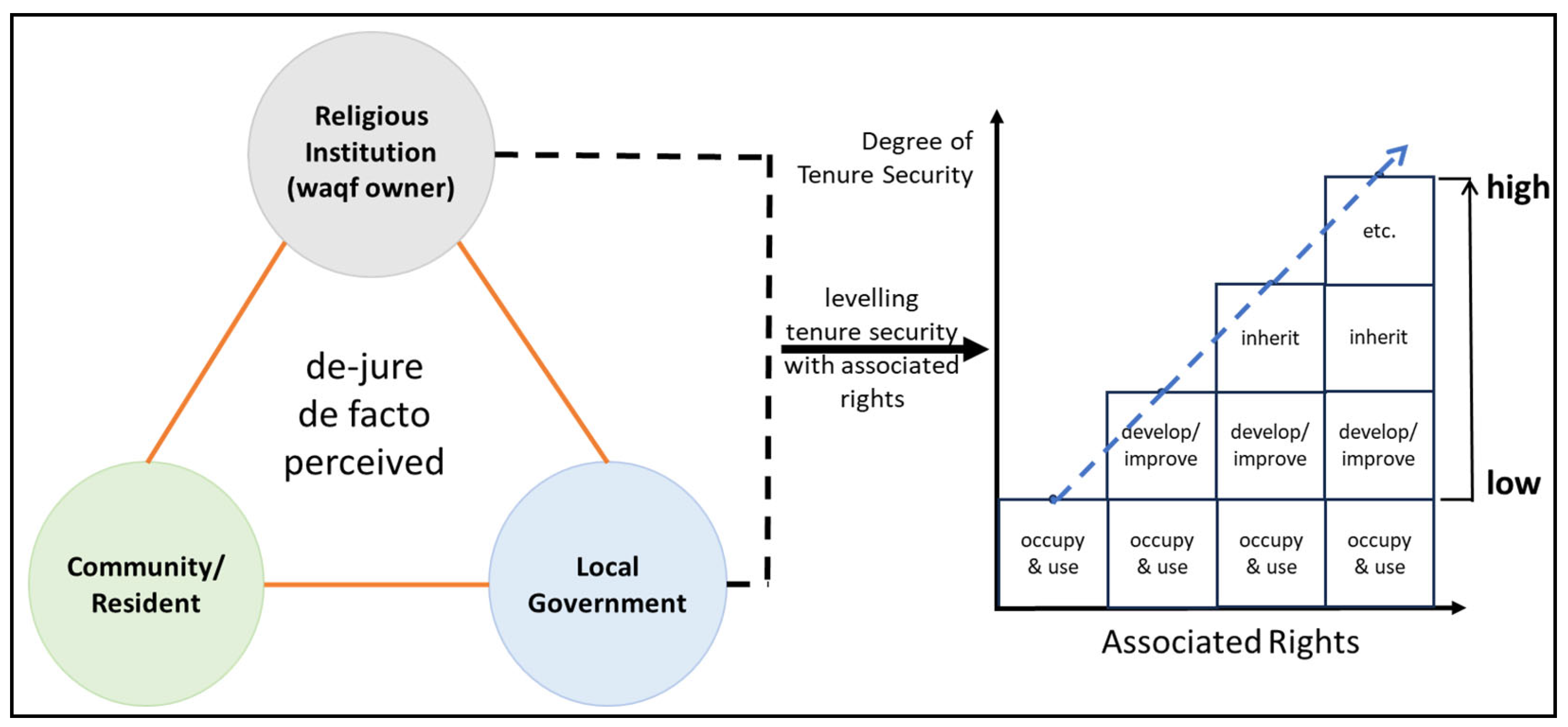

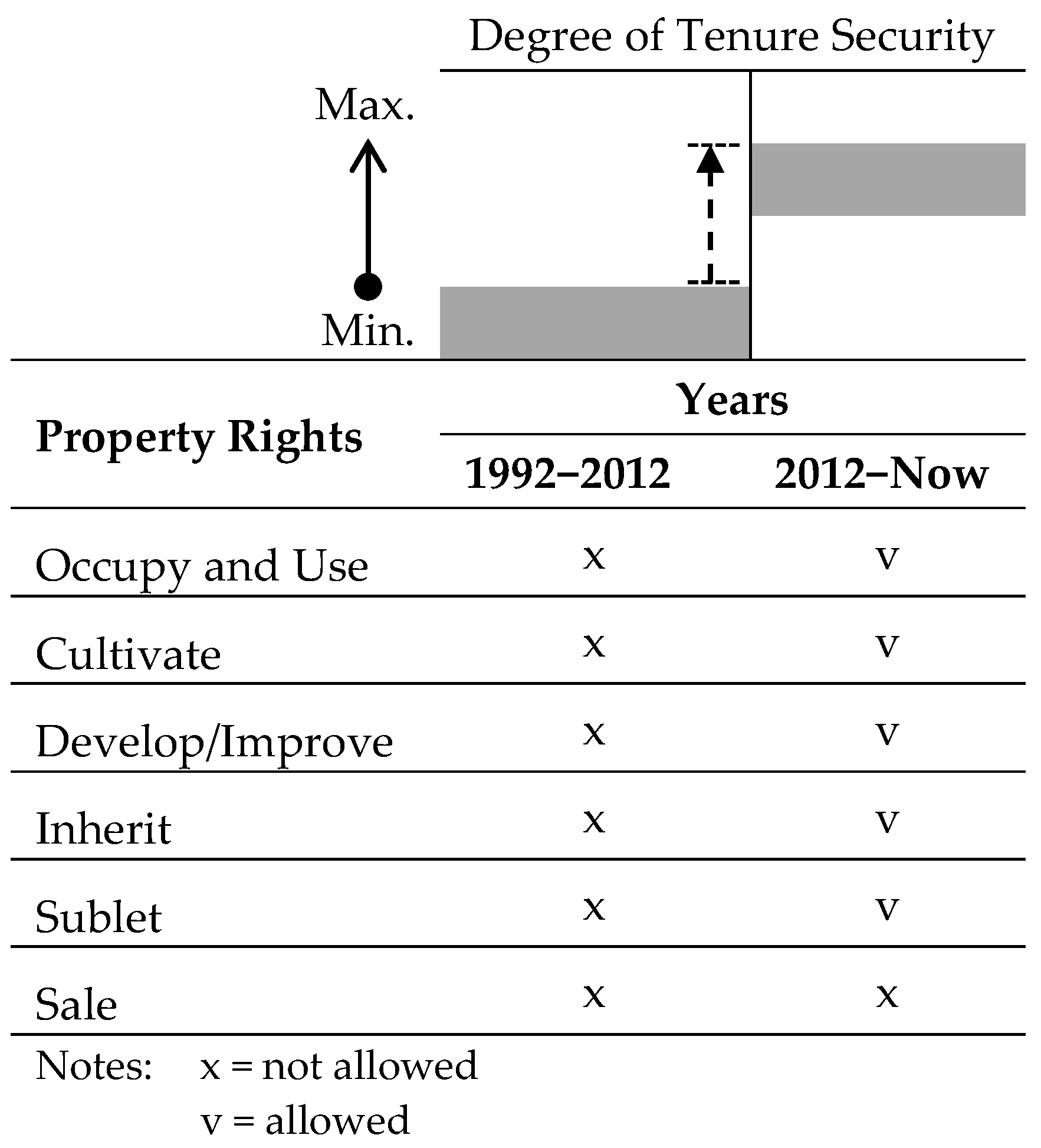

The existence of informal settlements on

Waqf land, as on the state’s land, is closely related to tenure security issues. Tenure security refers to the degree of confidence land users have that their land rights will be recognized and protected. The tenure continuum model works on extralegal property systems, arguing that secure tenure can exist even without formal titles. It may be documented, socially recognized, or perceived. The model provides an opportunity to enhance tenure security through associated rights across various tenure categories (see

Figure 1), which may lead to increased investments in housing, improved access to services, and reduced vulnerability to eviction [

36,

37].

The intersection of

Waqf land, informal settlements, and tenure security presents a compelling lens through which to examine contemporary urban challenges, particularly in Muslim-majority countries. While these elements are often studied independently, integrating them reveals deeper structural issues and opportunities in land governance, particularly for marginalized urban populations.

Waqf land, by its nature, is designed to serve public welfare. Yet, the institutional and legal rigidity surrounding its inalienability often leads to underutilization in contexts where urban poverty and housing shortages are most acute [

38,

39]. Informal settlements, emerging as grassroots responses to exclusion from formal housing markets, ironically occupy lands that were historically intended for social benefit, including

Waqf lands. This phenomenon demonstrates both the spatial and ethical contradictions of urban development in contexts where religious institutions control significant land resources but operate in parallel to urban planning systems.

The acknowledgment of informal settlements on

Waqf land is a protracted process, frequently characterized by conflict and disputes, particularly in cases where historical administration and documentation were insufficient. Conversely, informal settlements typically evolve over extended periods, often across generations. In certain instances, such as in Indonesia, these settlements have been integrated into land-use plans as designated residential areas. Collaboration among local governments, religious institutions that manage

Waqf land, and the communities residing on such land is crucial for developing viable options for the persistence of informal settlements [

40]. Models such as community-managed leases (community

Waqf) or co-governance arrangements could be applied without breaching the Islamic legal principle of inalienability. These mechanisms may simultaneously enhance residents’ sense of security and allow for planned urban integration.

4. Results

4.1. Socioeconomic Characteristics

Understanding the community’s characteristics is critical for investigating the role of informal settlements and practices on

Waqf property since these characteristics influence whether culturally embedded actions and policies are appropriate or not. Recognizing the historical settings unique to

Waqf land reduces disputes and upholds religious frameworks, understanding social dynamics promotes resource allocation and collaboration. Finally, identifying these qualities can establish a baseline for assessing the effectiveness of the solutions and generate insight into the kind of community a project is affecting. The socio-economic characteristics of the study area reveal a community facing significant challenges related to household structure, education, occupation, and income level. The settlement distribution in a specific location reflects the socioeconomic conditions of the population living in the respective area [

45].

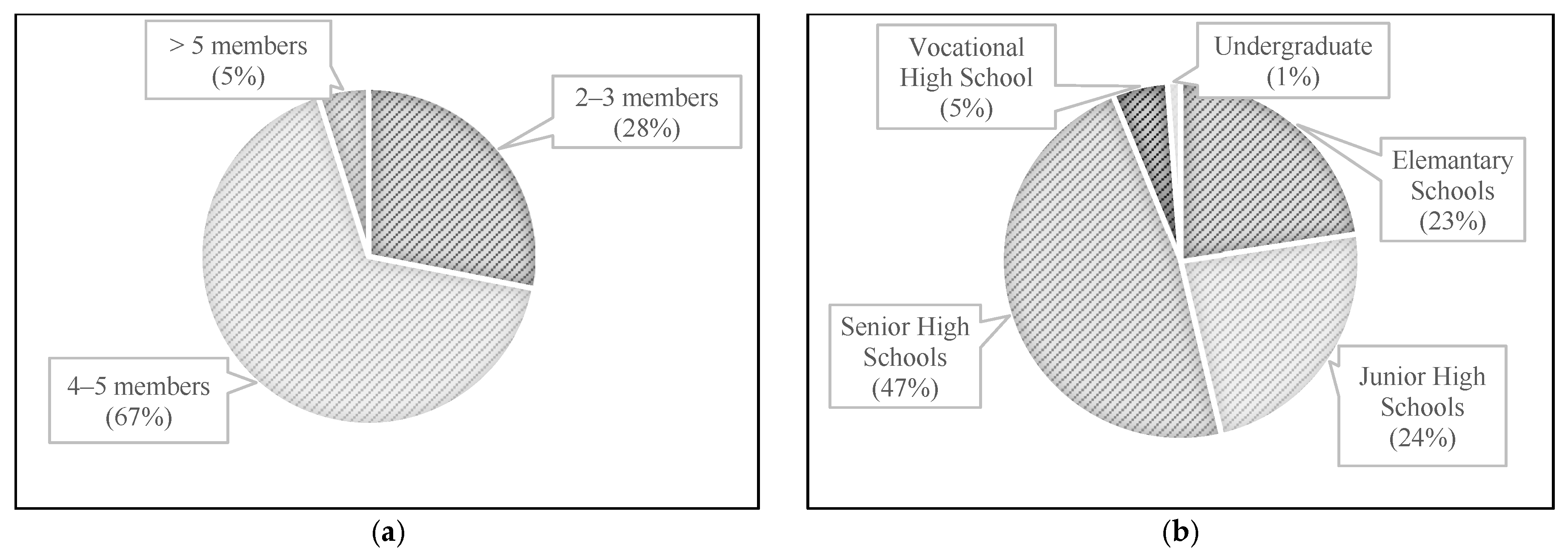

The data from the selected study area demonstrate that 67% of the total sample households have an average of four to five family members (see

Figure 3a). In these households, usually only one individual works and provides the income for the entire household. A larger household size can lead to difficulties in land tenure (or even more in obtaining formal land rights), which severely influences the quality of life as well as the quality of the construction of the houses [

21]. According to the survey, the greater demand for space and resources in larger households increases their tenure insecurity, making it more difficult for these families to maintain a sustainable living space. This, in turn, enlarges the economic challenges these households face.

Educational attainment (

Figure 3b) was primarily at the high school level, but also encompassed senior and vocational education, and constituted approximately 52% of the total sample. Junior high school represented 24%, and elementary education 23% of the total sample. There is a low number of university graduates. Statistically, higher education levels correlate with and yield improved employment opportunities and increased earning potential, and thus impact economic mobility and quality of life through the intangible variable of knowledge and skills [

45]. The survey shows a significant gap in higher education attainment, which may affect employment opportunities, economic mobility, and overall quality of life in the study area.

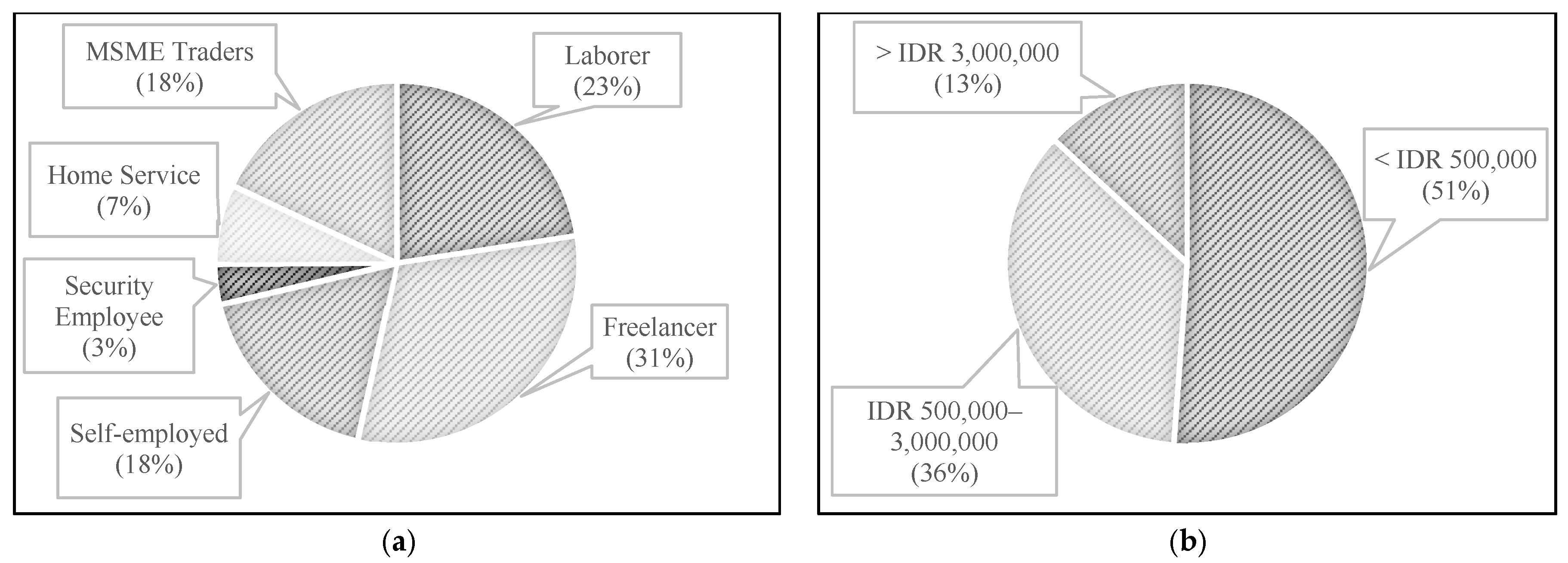

Regarding occupation (see

Figure 4a), 26 or 31% of respondents in the study area are freelancers, followed by (manual) laborers at 23% in various capacities. Self-employed individuals, including booth managers and street vendors, represent 18%, comparable to Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) engaged in trading. Simultaneously, security personnel and home service constituted 10% of the total respondents. These figures illustrate that a significant portion of the community is engaged in informal occupations, predominantly in self-employment within the neighborhood. The interconnection between informal settlements and informal occupations highlights that informal settlements represent a significant and dynamic sector influencing urban growth [

46].

Monthly income per household is an indicator of a community’s socioeconomic status and reflects the overall financial conditions and lifestyles. This indicator is thus a proxy to assess and locate poverty levels, and can highlight spatial income inequality through the analysis of income distribution among households. Additionally, it can help prioritize where and to whom social welfare and economic assistance should be provided [

45].

Figure 4b shows that the average monthly income per household is below IDR 500,000, representing 51% of the total respondents. This is followed by 36% of respondents earning between IDR 500,000 and IDR 3,000,000, and 13% earning more than IDR 3,000,000. This indicates that over fifty percent of the community lacks sufficient financial resources, potentially impacting their ability to meet basic needs and exacerbating economic challenges within the settlement, especially concerning the sustainability of monthly dues established as the standard payment for residing on

Waqf property. In order to obtain extra income, the majority of households are exploring job alternatives in diverse informal sectors, including local vendors and more in-home services.

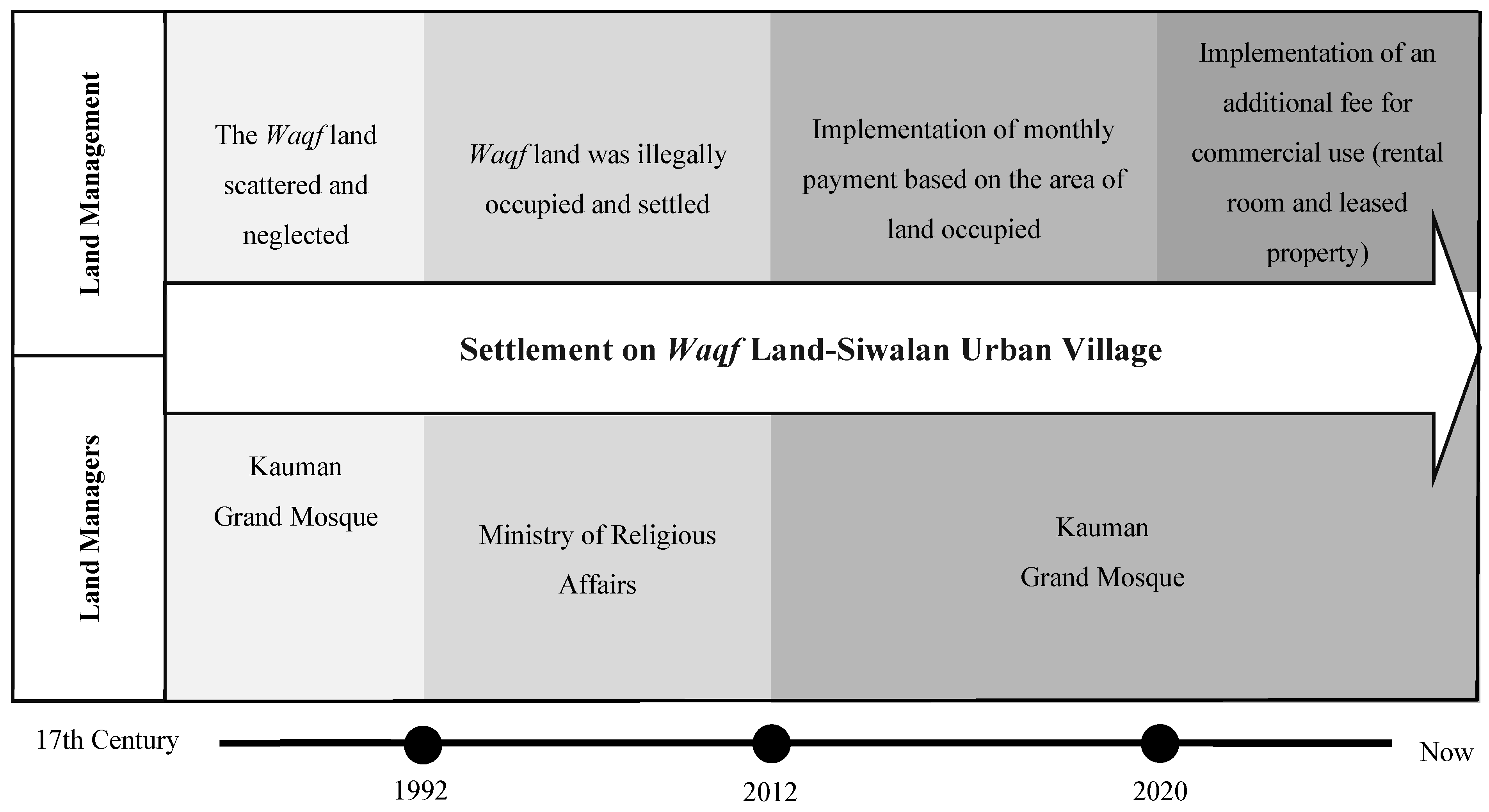

4.2. History and Transformation

The

Waqf land associated with the Kauman Grand Mosque has existed since the 17th century, and this Mosque’s land is distributed in various locations in the area from Semarang City to the Demak Regency. Previously,

Waqf land was dispersed to various locations and received insufficient attention from scholars and practitioners. This has led to improper management [

47]. In certain instances,

Waqf land was even occupied by unauthorized parties. The management of

Waqf land was previously conducted by the Ministry of Religious Affairs through the

Nazir, as representatives, following Regulation of the Minister of Religious Affairs No. 4 of 2009. The

Nazir is the entity that receives

Waqf property from the

Waqif, the individual who donated the

Waqf land, for management and development according to its designated purpose at that time.

The community started occupying

Waqf land in 1992 by commencing the construction of semi-permanent houses without obtaining the necessary permissions. Earlier studies show that individuals invest in specific housing levels due to the absence of formal tenure, aiming to secure themselves against involuntary displacement [

48,

49]. Without any evident regulatory direction, the study area has gradually become occupied by second-generation families. This proves that while the original settlers of

Waqf land established their families there, their descendants have remained in the region, and thus followed practices of adverse possession. In 2012, the administration of the

Waqf land was reverted to the Kauman Grand Mosque as a result of an agreement between the Mayor of Semarang City, the Ministry of Religious Affairs, and the Kauman Grand Mosque.

Figure 5 indicates the history and transformation of

Waqf land management in the study area.

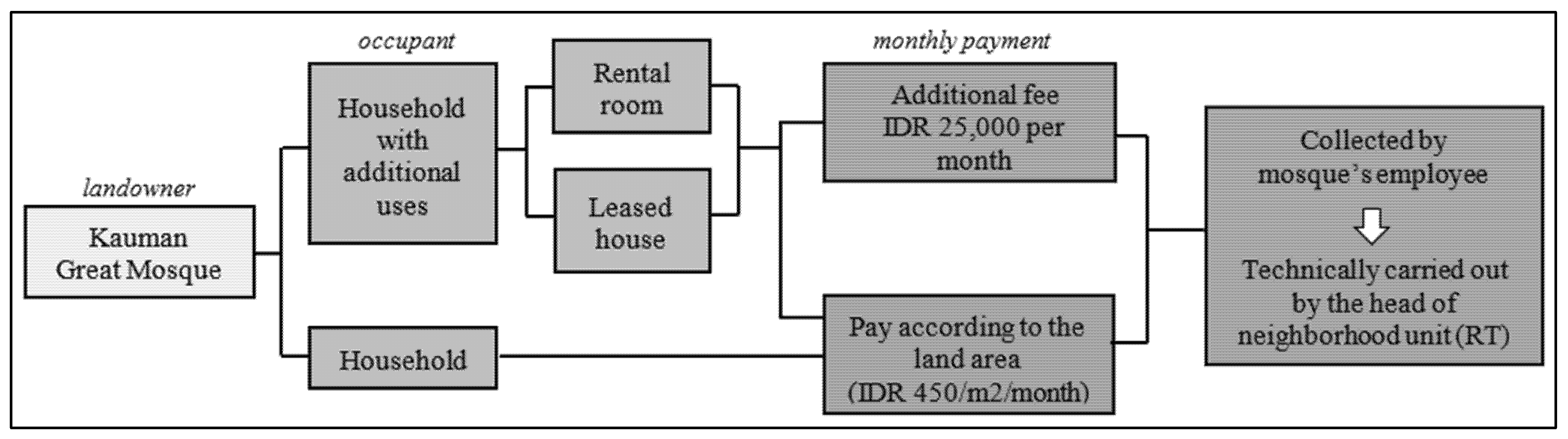

The Kauman Grand Mosque significantly contributes to addressing the land occupation issues faced by the community. Over time, this land occupation has resulted in the formation of 10 neighborhood units (RTs) on Waqf land, leading to disputes between the Kauman Grand Mosque, the owner, and the community occupying the land. To prevent conflicts and disputes, the Kauman Grand Mosque ultimately provided long-term leases to the community following numerous discussions and negotiations. A decision was reached to establish a monthly payment system for the community residing on the Waqf land. In this context, the Kauman Grand Mosque’s role can be divided into three parts to ensure the sustainability of the established system. Firstly, collecting monthly payments via mosque personnel who collaborate with the RT chairman regarding the Waqf land. Secondly, conveying the types of policies enacted due to changes taking place on the Waqf land. Thirdly, documenting the data of residents occupying the Waqf land and issuing signboards as markers and recognition.

A monthly payment system was established with the transfer of Waqf land management from the Ministry of Religion to the Kauman Grand Mosque in 2012. The payment depended on the size of the area of land occupied by each family. The systematic management of Waqf land tenancy agreements addresses significant challenges for both the mosque and the community. From the mosque’s perspective, these measures are essential for preventing neglect of the Waqf land, ensuring its preservation and effective utilization through documented contracts, regular rent payments, and rigorous arrears management. This technique guarantees stable revenue to support the mosque’s operations and secure the long-term value of the land. The agreements give the community a fundamental sense of security and stability, enabling residents to occupy the land without fear of eviction or relocation. Adhering to contract requirements enables community members to maintain their homes confidently, fostering a collaborative partnership that benefits both the religious institution and the community. However, this approach is significantly reliant on the dedication of both parties [

50], the Waqf land manager and the community, particularly the Kauman Grand Mosque.

4.3. Form of Handling and Agreement

The agreements established between land managers and occupiers in Siwalan Urban Village are regulated by a systematic and structured process, especially regarding

Waqf property. The agreements are based on a written contract that is valid for two years and includes provisions for renewal. The agreement is uniformly extended in all instances, irrespective of the household’s capacity to fulfil the monthly payment requirements. The calculation will be classified as debt, due at the end of the year, reflecting a level of partiality and flexibility. As shown in

Figure 6, the rental fees are contingent upon land area, set at IDR 450 per square meter per month (USD 1 = IDR 16000). The mosque employees oversee and collect rent from the community, ensuring transparency and compliance with lease conditions. The mosque appoints a representative from the residents, usually the Head of the Neighborhood Units (RTs), to act on behalf of the residents and to oversee the collection of monthly contributions from the community. This strategy guarantees a consistent revenue stream for the mosque’s operations and maintenance, while also offering alternatives for its residents.

As noted earlier, before the Kauman Grand Mosque assumed full responsibility for the

Waqf land, the occupants made no payments and resided without authorization, rendering them vulnerable to eviction. Formal agreements were established following the transfer of authority for managing the

Waqf land to the Kauman Grand Mosque. The main objective of the agreement is to preserve and secure the

Waqf land. The agreements help protect the land’s value and usefulness to the community by setting clear terms, ensuring consistent management, and providing effective oversight. This management model assists land managers and occupants by promoting sustainability, accountability, and spatial justice, ensuring equitable access to land resources for meeting basic needs [

51,

52]. The agreements outlined the occupants’ identities and the legal stipulations regarding permissible actions. Further, additional changes were made as certain residents modified their homes for commercial use, including rental rooms and leased properties, with an extra monthly fee of IDR 25,000 imposed. Amidst all the changes, the mosque and the community consistently emphasized the importance of thoughtful discussion to achieve a consensus.

4.4. The 8R Framework Assessment of Waqf Land Management

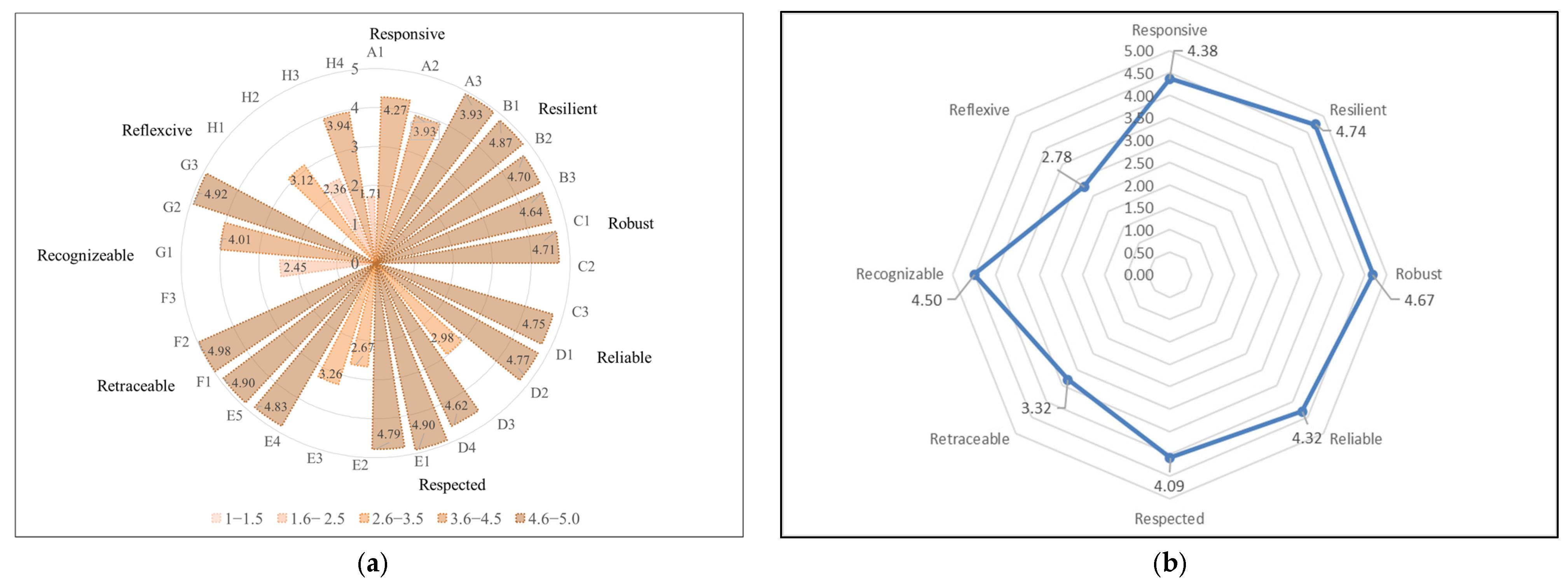

A radar graph is utilized to enhance understanding of appropriate

Waqf land management based on the previously mentioned 8R Framework. The radar graph facilitates the visualization of data distribution. This radar graph analysis clarifies the average outcomes of the completed data processing. The highest and lowest average outcomes are presented, and the underlying factors are elucidated.

Table 3 and

Figure 7 show the results of the 8R assessment.

The resilient position is the highest, recorded at 4.74. This suggests that the resilient aspect possesses the highest total average and demonstrates significant influence and effective application in the context of the Waqf land in Siwalan Village. The highest average score of resilience was derived from the three component scores of B1 (4.87), B2 (4.70), and B3 (4.64). The formal legal protection is the primary contributing factor, as the community is embraced and recognized by the Kauman Grand Mosque as the owner of Waqf land. A formal agreement between the mosque, the land manager, and the community delineates the rights and responsibilities of each party, thereby fostering a continuous and secure environment for the community. The mosque’s robust support in recognizing and formalizing the agreement and active engagement with the community to address issues through structured agreements significantly enhanced the resilience score.

The robust aspect received the second-highest average score of 4.67. The average scores of robustness were derived from the scores of C1 (4.71), C3 (4.75), and C2 (4.56). The result indicates the Waqf holder’s capacity to sustain the stability and effectiveness of their policies under diverse conditions, including the unauthorized construction of settlements on Waqf land. The Waqf holder needed to establish new policies and collaborate with the residents of the Waqf settlements to safeguard their mutual interests. The ability of Waqf managers to sustain policy stability and effectiveness amidst various pressures and changes indicates the presence of a robust and adaptive management system.

The third highest score among various R frameworks is the recognizable aspect, with an average score of 4.5, calculated from the average scores of G1 (4.01), G2 (4.92), and G3 (4.58). This demonstrates the

Waqf owner’s unique ability to recognize and understand the priorities and needs of the residents living on the

Waqf land. The

Waqf owner has enacted significant measures to ensure that each resident feels valued and recognized, as indicated by the high score. Implementing the signboard on each residence constitutes a fundamental action (see

Figure 8). The board includes essential information, such as the name of the head of the family, the address, and the house serial number on the

Waqf land. This initiative enhances the sense of security and belonging.

The average score for responsiveness is 4.38, reflecting the effectiveness of Waqf owners in addressing the issues and needs of residents on Waqf land. The highest contributing score is A3 (4.93), followed by A1 (4.27) and A2 (3.93). Responsiveness in this context denotes the capacity of Waqf landowners to promptly address residents’ complaints, suggestions, or needs. The findings indicate that the policy of paying dues is effective in the management system of Waqf land, as the community acknowledges this policy as a recognition of their existence. Effective and adaptable policies demonstrate the Waqf land manager’s Responsiveness to community needs and perspectives.

The reliability aspect has an overall average score of 4.32, with the highest contribution from component D4 (4.90), followed by D1 (4.7), D3 (4.62), and D2 (2.98), which has the lowest score. The high scores of D4 and D9 indicate the significant public trust in the residence permit policy concerning Waqf land, which additionally ensures security of tenure. Conversely, trust has been established within the community, as Waqf land managers granted authority to appointed community representatives who serve as contact persons and collectors of monthly dues. Further, this may enhance public confidence in the actions of the Waqf owner concerning policy changes. Trustworthiness is essential for improving the effectiveness of the management of Waqf land in the study area. The significant reliability suggests that the Waqf landowner has successfully cultivated strong connections with the community. Waqf owners can implement policies and address future challenges more effectively when they possess high public trust. Continuous efforts are necessary to maintain and improve this trust.

Regarding the respect aspect, the assessment shows a moderately high level, with a total average score of 4.09. From the five components, the highest average score is E5 (4.90), followed by E4 (4.83), E1 (4.79), E3 (3.26), and E2 (2.67). The Waqf owner has taken significant steps to guarantee that each resident feels appreciated and acknowledged. This is shown by the higher score of good responsibility of Waqf land managers in registering and administering the Waqf land, followed by the effectiveness of regulating the land development in the study area. However, the community perceives that communication between the Kuaman Grand Mosque as the Waqf landowner and residents is inadequate, as it occurs solely through the appointed Waqf land manager.

Retraceability denotes the capacity to track and authenticate Waqf land’s historical ownership and licensing modifications. The results indicate that the retraceability total average score is 3.32, reflecting a moderately low score from three components, namely F1 (4.98), F2 (2.54), and F3 (2.45). The high score of F1 indicated that the community is aware of the importance of physical evidence as recognition to settle on Waqf land. However, in general, the survey results indicate low effectiveness in this aspect, suggesting that residents encounter challenges in accessing information about the history of land ownership and policy changes. The community acknowledges the significance of physical evidence of residence on Waqf land as an assurance for ongoing possession. On the other hand, the community’s access to records for people residing on Waqf land owned by the Kauman Grand Mosque is limited, as only community representatives are permitted to view these records. Therefore, the delivery of trust to Waqf managers as representatives of the community is important in order to ensure that all records pertaining to holders and licensing are properly maintained.

The last R component is reflexive, which recorded the lowest total average score of 2.78. The final average score was calculated from components H3 (3.94), H2 (3.12), H1 (2.36), and H4 (1.71). The community believes that the monitoring of Waqf land conducted by landowners is successful in tracking developments in the study area, as indicated by the H3 score. The introduction of monthly dues is included in the policy assessment, with most of the community expressing opposition to any increases. Anticipated policy changes will engage the community residing on the Waqf land more actively. In practice, the role and contributions of the community are mainly reflected through appointed community representatives. This suggests challenges related to transparency and reflectiveness in Waqf land management within the study area.

5. Discussion

The primary contributors to responsible

Waqf land management are resilience (4.74), robustness (4.67), and recognizability (4.5). This demonstrates that the management system has significantly enhanced the settlement’s resilience and capacity to recover from challenges and disruptions, as noted by [

53]. The enhanced resilient score signifies strong protection for individuals living on

Waqf land, providing clarity and security for residents, especially against evictions frequently occurring in such settlements [

3]. Robustness is associated with the sustainability of ‘policy strength’ and the capacity of a society and its institutions to withstand transformation [

54]. Maintaining trust and effective cooperation between

Waqf landowners and residents is crucial for the sustainability of

Waqf land management. These two aspects indicate that the

Waqf owner possesses a robust and flexible management system, effectively sustaining trust and fostering positive community collaboration, while in recognizability, implementing personalized measures allows the

Waqf owner to foster a more resilient and trustworthy community. Residents feel acknowledged and valued, as they understand that the

Waqf management recognizes their presence and identity, and hence increases their tenure security level [

49] (see

Figure 9). This method exemplifies the

Waqf owner’s commitment to creating an inclusive and supportive community by prioritizing individual needs and addressing them thoughtfully.

Meanwhile, the aspects responsive, reliable, and respected also received relatively high scores with average scores of 4.38, 4.32, and 4.09. High responsiveness fosters effective communication between parties and enables rapid response to emerging issues. This emphasizes the necessity for

Waqf managers to respond promptly and efficiently to raise awareness effectively, which requires flexible legal interpretations and participatory decision-making [

55]. Implementing transparent and open policies will facilitate the establishment of trust between the

Waqf owner and residents. In the reliability aspect, measurement on effective communication, transparency in decision-making, and prompt responses to emerging issues can be implemented.

Waqf owners must adjust policies to align with society’s evolving needs and aspirations while remaining vigilant to potential conflicts or dissatisfaction arising from these changes. The respected aspect must be enhanced to ensure that residents feel at ease and valued, as they know that the

Waqf management acknowledges their existence and identity. This subsequently improves their overall sense of security and stability within their living environment. The survey indicated that direct communication concerning

Waqf land between

Waqf owners and holders was limited, leading to uncertainty regarding the residents’ status at certain times. Thus, establishing a direct and clear communication channel and conducting regular meetings to address existing issues and requirements is essential in order to avoid disputes [

20]. This intensive interaction fosters stronger relationships and ensures that the voices and needs of the community are considered in all decision-making processes.

The least significant scores are for the aspects retraceability (3.32) and reflexiveness (2.78). The attributes of retraceability and reflexivity receive the lowest average ratings owing to limited access to relevant documents and infrequent alterations. No reassessment was conducted to identify areas for potential improvement. This issue is essential for maintaining land management responsibilities to avoid disputes and mismanagement of the enhancement. Enhancing inclusive and participatory development may improve tenure security for urban poor and low-income residents [

51]. The limited effectiveness in the reflexive aspect suggests that the policy evaluation and adjustment process remain suboptimal. Residents perceive a lack of representation in the decision-making process, and the policies enacted are frequently not subjected to a comprehensive evaluation regarding their impact. Consequently, current policies may lack relevance or effectiveness over time, potentially hindering the development and welfare of communities on

Waqf lands. Ramadhani et al. [

56] emphasize the significance of physical evidence, particularly written agreements, as a crucial means of proof in instances of agreement failure by one party.

Waqf managers must ensure that all records pertaining to holders and licensing are properly maintained and readily accessible to the public. Transparency in information dissemination enhances public trust in

Waqf management and guarantees all stakeholders equal access to essential information. Therefore, enhancing the retraceability aspect will bolster the community’s sense of security and trust in

Waqf land management.

The inability to review and adapt policies in response to evolving conditions and needs is attributed to policies that do not influence the dynamics between the Waqf owner and the community. Furthermore, the lack of traceable and verifiable documentation diminishes transparency and accountability, thereby undermining trust and a sense of security among residents. Consequently, it is imperative to facilitate access to Waqf land documents. By enabling the public to easily access and verify pertinent documents, such as land certificates and agreement documents, residents of Waqf land can gain a clearer understanding of their rights and obligations. This measure will also alleviate the uncertainty and anxiety residents may experience regarding the legal status of the land they occupy.

Concerning the policy of increasing monthly payments for those expanding their property functions, it is crucial to assess the impact and implications of this policy by considering variations in business scale and financial capacity among boarding house and contract owners. The disparity in the new policy, which is exclusively applied to boarding house owners and renters, requiring them to pay an additional fixed monthly fee, suggests an inequity in the treatment of small business owners compared to those with larger enterprises. In this context, boarding house owners or small renters with a limited number of rooms will be more adversely affected than owners with numerous rooms. Efforts to adjust policies to ensure greater fairness and sustainability for all stakeholders will contribute to the establishment of an inclusive and sustainable environment, ultimately enhancing social welfare in the study area.

6. Conclusions

The findings indicate that the study area has experienced a transformation of informal settlements into more formal ones. These findings are recognized by the Waqf landowners, the Kauman Grand Mosque. The transformation involves multiple processes, beginning with land placement and culminating in an agreement between the owner and the user. This agreement is formally recognized through the installation of placement signboards and an inventory list of users maintained by the landowner. This process involves extensive negotiation and communication, given that the residents residing on Waqf land do not own the land. The recognition granted is significantly influenced by the willingness and flexibility of the Waqf landowner to accommodate informal settlements on the Waqf land, as well as the community’s commitment and acceptance of the proposed conditions aimed at preserving and benefiting the Waqf land.

The community’s commitment and acceptance are manifested through an agreement between the owner and the users. It is crucial for enhancing community resilience regarding the allocation of Waqf land. The implemented agreement can potentially increase the status of Waqf residents from squatters to holders of a higher tenure category. The contractual policy mandating the payment of dues as outlined in the agreement provides residents of the Waqf land with enhanced security regarding land protection, as they have been granted permission to remain. From the mosque’s perspective, the agreement represents an effort by the land managers to protect Waqf assets and maintain the integrity of the property. From the community’s perspective, these agreements offer a practical solution that addresses their immediate needs by ensuring security and stability in their living environment. Formalizing their occupation and property usage enhances the community’s confidence and legitimacy, alleviating fears of displacement. The agreement effectively preserves Waqf assets while providing a secure living environment for the community, highlighting the importance of careful stewardship of Waqf property.

In planning contexts, it is essential to prioritize land tenure security when addressing similar occurrences in other regions. The interconnection between land tenure security and responsible land management is evident; however, the emphasis should be placed on the degree of land tenure itself. Stable land tenure is essential as it provides inhabitants with rights and protections against eviction, fosters economic stability, and incentivizes investment in property improvements. Consistency is essential for sustainable community development and effective land management. Upon establishing tenure security, attention can be focused on responsible land management to ensure the property serves its intended purpose and benefits the community.

This study addressed the significance of the practice of formalizing informal urban settlements. However, it did not explore the socio-economic development opportunities. This is suggested as certain communities have established businesses on Waqf land, thereby expanding the potential uses of Waqf land beyond simple occupation. Future research should examine the advantages of Waqf land in enhancing community living standards and well-being. Future research may also investigate the extent to which the findings of this study can be replicated in other areas as well. We acknowledge that communities are different, but their circumstances may be similar, especially in the same Indonesian regulatory context. Such studies can confirm our findings. Additionally, one could compare the practices in other regulatory and territorial contexts where—similar to Indonesia—Waqf land exists alongside statutory land tenure. These include Turkey, Egypt, Pakistan, Jordan, and Malaysia. Such studies could evaluate the role of formal institutions and formal agreements in executing Waqf land management principles and practices.

This study identifies the predominant components of R in evaluating responsible land management; nevertheless, the transformation process involved has not been thoroughly detailed. This study only highlights the present circumstances in which Waqf land occupied by the community has attained explicit acknowledgement, alleviating any concerns over their status. We posit that the recognition of existing Waqf land likely entailed rigorous negotiation and discourse among multiple stakeholders, warranting more exploration in further studies.