Intervention and Co-Creation: Art-Led Transformation of Spatial Practices and Cultural Values in Rural Public Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

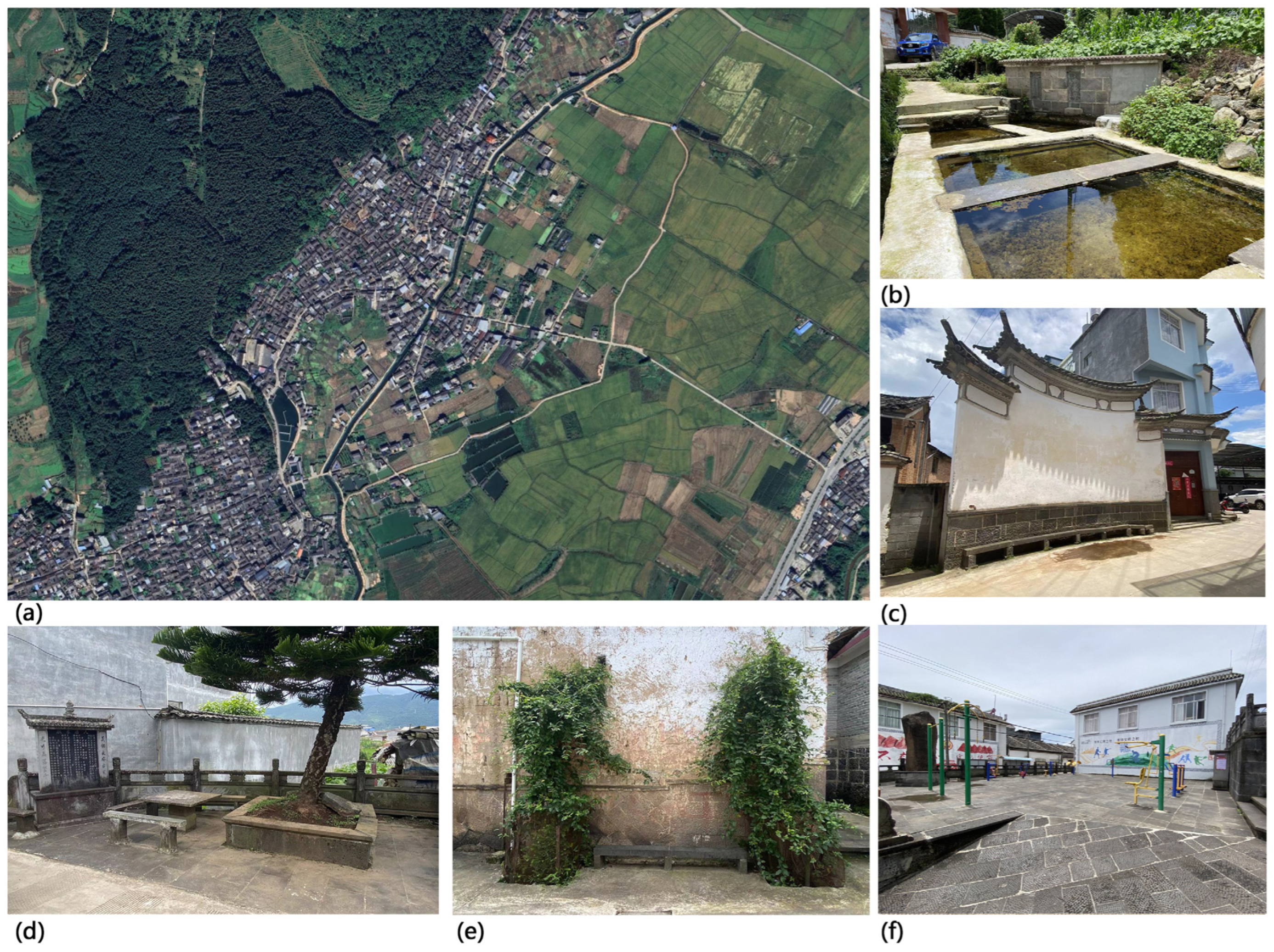

3.2. Research Area

- (1)

- Artistic Intervention in Residential Public Spaces

- (2)

- Artistic Intervention in Religious Public Spaces

3.3. Construction of Resident Satisfaction Model

3.3.1. Selection of Latent Variables

3.3.2. Selection of Observed Variables

3.4. Path Hypotheses and Model Assumptions

- (1)

- Positive Correlations Between Latent Variables: It is hypothesized that there are positive correlations between Artistic Innovation, Artistic Aesthetics, Spatial Features, Convenience of Use, Functional Safety, Cultural Integration, Element Extension, and Cultural Emotions. That is, when Artistic Innovation, Artistic Aesthetics, Spatial Features, Convenience of Use, Functional Safety, Cultural Integration, and Element Extension perform better, residents’ emotional cognition level will be higher.

- (2)

- Positive Correlation Between Cultural Emotion and Resident Satisfaction: It is hypothesized that residents’ emotional cognition of public spaces directly influences their overall satisfaction with the living environment. When emotional cognition is more positive, residents’ satisfaction levels will increase.

- (1)

- Latent Variables: Latent variables are abstract concepts that cannot be directly observed. They are reflected through multiple observed variables and are represented by ellipses.

- (2)

- Observed Variables: Observed variables are concrete indicators of latent variables, used for specific measurement, and are represented by rectangles.

- (3)

- Relationships Between Variables: In the model, arrows indicate the causal relationships between variables, and the “+” sign indicates a positive correlation.

- (1)

- Artistic Innovation, Artistic Aesthetics, and Spatial Features: As the core dimensions of spatial aesthetics, these variables indirectly influence emotional cognition through the reflection of infrastructure and service levels, thereby affecting residents’ satisfaction.

- (2)

- Convenience of Use and Functional Safety: As essential core elements of public space, these two variables significantly enhance residents’ emotional cognition and provide important support for the formation of satisfaction.

- (3)

- Cultural Integration and Element Extension: Cultural Integration and Element Extension enrich the cultural layers and diverse expressions of the space, strengthening residents’ sense of belonging and cultural identity, thus significantly improving their satisfaction.

- (4)

- Emotional Cognition: Emotional cognition, as a mediating variable, serves as a bridge linking physical space, cultural characteristics, and satisfaction. It is a key factor influencing residents’ satisfaction.

3.5. Survey Design and Data Collection

3.6. Data Analysis and Model Validation

3.6.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

3.6.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.7. Satisfaction Index Calculation

4. Results

4.1. Model Testing

4.2. Satisfaction Results and Discussion

5. Discussion

5.1. The Dual-Pathways of Satisfaction: Integrating the Symbolic and the Pragmatic

5.2. Implications for Rural Revitalization and Spatial Planning in China

5.3. Applicability and Limitations of the Model

5.4. Practical Recommendations for Structural Changes in Public Spaces

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. (2012). Notice on the First Batch of Chinese Traditional Villages List. |

| 2 | The “2023 Socio-Economic Development Statistical Report for Machang Village,” provided by the Tengyue Town People’s Government. |

| 3 | Interview records with the Machang Village Committee conducted by the research team in 3 month, 2024. |

References

- Wang, J.; Wen, F.; Fang, D. Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism and the Improvement of Rural Environment in China: Value Cocreation Perspective. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 237, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, N.Z.; Jaffar, N.; Mansor, M. The contributions of public space to the social sustainability of traditional settlements. Plan. Malays. 2021, 19, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Qiu, H.; Wang, X. The influence of spatial functions on the public space system of traditional settlements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, J. Research on public art intervention in rural public space transformation. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2018), Zhengzhou, China, 6–8 May 2018; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlee, M.; Omar, D.; Yunus, R.M.; Samadi, Z. Revitalization of urban public spaces: An overview. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 201, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, D.R. Public space and culture: A critical response to conventional and postmodern visions of city life. In Culture and Difference: Critical Perspectives on the Bicultural Experience in the United States; Penn State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 1995; pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V. Evaluating public space. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanipour, A. Whose public space? In Whose Public Space; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, T. The future of public space: Beyond invented streets and reinvented places. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2001, 67, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, N.; Harun, N.Z.; Abdullah, A. Enlivening the mosque as a public space for social sustainability of traditional Malay settlements. Plan. Malays. 2020, 18, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha, R. The limits of the beyond: Contemporary art practice, intervention and collaboration in public spaces. Third Text 2007, 21, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wu, M.; Gyergyak, J. Intervention and renewal− Interpretation of installation art in urban public space. Pollack Period. 2021, 16, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratas-Cruzeiro, C.; Elias, H.; Valente, C.; Cortez, T. Addressing SITU_ACCÃO: Case Study of an Artistic Intervention and Research into Public Spaces. Arte Individuo Y Soc. 2021, 33, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y. The impact and transformation evaluation of art intervention in public space on ancient villages: A case study of Tengchong, Yunnan Province. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Lopes, R. Artistic urban interventions, informality and public sphere: Research insights from three ephemeral urban appropriations on a cultural district. Port. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 16, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, G. Art as an Intervention in Public Space: How Art Can Act as a Medium to Cross Social Divides; Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change (EUC): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A. The Artists Village: Openly Intervening in the Public Spaces of the City of Singapore. Open Philos. 2019, 2, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Ruggeri, K.; Steemers, K.; Huppert, F. Lively social space, well-being activity, and urban design: Findings from a low-cost community-led public space intervention. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 685–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, J.; Pollock, V.; Paddison, R. Just art for a just city: Public art and social inclusion in urban regeneration. In Culture-Led Urban Regeneration; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 156–178. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, C. Art and democracy: Art as an agonistic intervention in public space. Open 2008, 14, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. Research on art intervention in rural design based on the cultural ecology: A case study of the Xun Jiansi village in Jiangxi province, China. Asian Soc. Sci. 2021, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X. Alternative micro-regeneration strategies for urban villages in China? Social entrepreneurship-based artistic intervention in Aohu Village in Shenzhen. Trans. Plan. Urban Res. 2024, 3, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Ji, X.; Su, Z.; Chen, A. Public sector design efficacy in rural development: A case study of the Future Village project in Changdai village, China. Int. J. Des. 2024, 18, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N.; Campbell, H. Developing and revitalizing rural communities through arts and culture. Small Cities Impr. 2011, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, F.; Ramele Ramli, R.; Nasrudin, N.A. Protection of traditional villages in China: A review on the development process and policy evolution. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zuo, H.; Ding, Z. Research on the Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics and Accessibility of Traditional Villages Based on Geographic Information Systems—A Case Study of Shandong Province, China. Land 2024, 13, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.Z.; Jamaludin, O.; Ing, D.S. A review on traditional villages protection and development in China. Construction 2024, 4, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, M. Characteristics and influencing factors on the hollowing of traditional villages—Taking 2645 villages from the Chinese traditional village catalogue (Batch 5) as an example. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Ding, Y.Q.; Tang, M.J.; Cao, Q.; Fu, M.; Yang, X.; Shen, J. Spatial Distribution Dataset of 1598 More Chinese Traditional Villages. J. Glob. Change Data Discov. 2019, 3, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Türkoğlu, S.; Terzi, F. Reflections of user satisfaction in public spaces: A structural equation modeling approach at Hasanpaşa Gazhane, Istanbul. Spatium 2024, 52, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. Interactive design and community participation: The case of Mullae Art Village. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2015, 18, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.R. A Case Study on the Public Space for Traditional Market Revitalization. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2020, 11, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Dilixiati, D.; Bell, S. The Use of Public Spaces in Traditional Residential Areas After Tourism-Oriented Renovation: A Case Study of Liu Xing Street in Yining, China. Land 2025, 14, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ju, S.; Wang, W.; Su, H.; Wang, L. Intergenerational and gender differences in satisfaction of farmers with rural public space: Insights from traditional village in Northwest China. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 146, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, S.B. Diversity in the public space of a traditional city-Zaria, Nigeria. Open House Int. 2012, 37, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuni, J.; Dehove, M.; Dörrzapf, L.; Moser, M.K.; Resch, B.; Böhm, P.; Leder, H. Art in the City Reduces the Feeling of Anxiety, Stress, and Negative Mood: A field study examining the impact of artistic intervention in urban public space on well-being. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2024, 7, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H. Analysis on the Three-Dimensional Intervention Mode of Public Art in Rural Culture from the Perspective of 3D Video. Sci. Program. 2022, 2022, 5090023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán Uriel, J.; Camerin, F.; Córdoba Hernández, R. Urban Horizons in China: Challenges and Opportunities for Community Intervention in a Country Marked by the Heihe-Tengchong Line. In Diversity as Catalyst: Economic Growth and Urban Resilience in Global Cityscapes; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altrock, U.; Huning, S. Cultural interventions in urban public spaces and performative planning: Insights from shrinking cities in Eastern Germany. In Public Space and Relational Perspectives; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 148–166. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Vetro, A.; Concha, P. Building safer public spaces: Exploring gender difference in the perception of safety in public space through urban design interventions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J.C.; March, T.L. An urban community-based intervention to advance social interactions. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-García, M.A.; Wilde, E. Sound installation art and the intervention of urban public space in Latin America. SoundEffects-Interdiscip. J. Sound Sound Exp. 2021, 10, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, B. Cultural Hijack: Critical Perspectives on Urban Art Intervention; University of the West of Scotland: Glasgow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hotakainen, T.; Oikarinen, E. Balloons to talk about: Exploring conversational potential of an art intervention. Planext–Next Gener. Plan. 2019, 9, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, A.; Petrescu, D.; Nawratek, K. Performative interventions to re-claim, re-define and produce public space in different cultural and political contexts. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.; He, Z. Research on form construction of art intervention in old renovation space. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Urban Engineering and Management Science (ICUEMS), Zhuhai, China, 24–26 April 2020; pp. 505–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, D. Urban interventions: Art, politics and pedagogy. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2008, 32, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, T. Street art as a form of socio-educational intervention. In KISMIF Conference—Book of Abstracts; Universidade do Porto, Faculdade de Letras: Porto, Portugal, 2022; p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- Matyczyk, E. Intervention, Memory, and Community: Public Art and Architecture in Warsaw Since 1970. Ph.D. Thesis, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, T. Interventions in the rust belt: The art and ecology of post-industrial public space. Ecumene 2000, 7, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.M.; Payerhofer, U.; Wals, A.; Gratzer, G. The art of arts-based interventions in transdisciplinary sustainability research. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudai, R.; Gready, P. From human rights documentation towards arts-based interventions: NGO collaborations with artists and the reimagining of human rights. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, C.; Steyaert, C. By accident and by design: Composing affective atmospheres in an urban art intervention. Organization 2017, 24, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsetti, E.; Tollin, N.; Lehmann, M.; Valderrama, V.A.; Morató, J. Building resilient cities: Climate change and health interlinkages in the planning of public spaces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukmirovic, M.; Gavrilovic, S.; Stojanovic, D. The improvement of the comfort of public spaces as a local initiative in coping with climate change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, C.D.; Even, T.L.; Frame, S.M. Merging the arts and sciences for collaborative sustainability action: A methodological framework. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1067–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flämig, K.; Decroo, T.; van den Borne, B.; van de Pas, R. ART adherence clubs in the Western Cape of South Africa: What does the sustainability framework tell us? A scoping literature review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, T. Integrating sustainability into contemporary art and design: An interdisciplinary approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.C.; Farinha, J.; Amado, M. Sustainability through art. Energy Procedia 2017, 119, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, S. Culture and the arts in sustainable development: Rethinking sustainability research. In Cultural Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Crealey, G.; McQuade, L.; O’Sullivan, R.; O’Neill, C. Arts and creativity interventions for improving health and wellbeing in older adults: A systematic literature review of economic evaluation studies. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, E.Y.; Von Eye, A.; White, H.R. An SEM approach for the evaluation of intervention effects using pre-post-post designs. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2009, 16, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ling, G.H.T.; Misnan, S.H.b.; Fang, M. A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing the Vitality of Public Open Spaces: A Novel Perspective Using Social–Ecological Model (SEM). Sustainability 2023, 15, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Kassem, M.A.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Lin, M. Safety risk assessment in urban public space using structural equation modelling. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Peng, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhong, C.; Wang, W. Assessing comfort in urban public spaces: A structural equation model involving environmental attitude and perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elewa, A.K.A. Flexible public spaces through spatial urban interventions, towards resilient cities. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobadilla, N.; Goransson, M.; Pichault, F. Urban entrepreneurship through art-based interventions: Unveiling a translation process. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 378–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, P. Public art: Radical, functional or democratic methodologies? J. Vis. Art Pract. 2008, 7, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, M. Artistic interventions and pockets of memory on the former wall strip in Berlin. In The Impact of Artists on Contemporary Urban Development in Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski, C.S.; Winge, L.; Carroll, S.; Schmidt, T.; Wagner, A.M.; Nørtoft, K.P.J.; Troelsen, J. Move the Neighbourhood: Study design of a community-based participatory public open space intervention in a Danish deprived neighbourhood to promote active living. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Huangfu, G. Crustal structure in Tengchong volcano-geothermal area, western Yunnan, China. Tectonophysics 2004, 380, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, N.K.; Guo, S. Structural Equation Modeling; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.Q.; Bentler, P.M. Enhancing model fit evaluation in SEM: Practical tips for optimizing chi-square tests. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2025, 32, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati Nasab, M.R.; Sattari Sarbangholi, H.; Pakdelfard, M.R.; Jamali, S. Structural equation modeling (SEM) the relationship between environmental quality and social cohesion components by explaining the mediating role of social resilience in urban cultural spaces. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2023, 14, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Lin, X.; Han, X.; Lu, X.; Zhao, H. Landscape Efficiency Assessment of Urban Subway Station Entrance Based on Structural Equation Model: Case Study of Main Urban Area of Nanjing. Buildings 2022, 12, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamidurai, S. Evaluation of people’s willingness to use underground space using structural equation modeling–Case of Phoenix market city mall in Chennai city, India. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 91, 103012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, D. Multiple linear regression-structural equation modeling based development of the integrated model of perceived neighborhood environment and quality of life of community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study in Nanjing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartko, J.J.; Carpenter, W.T. On the methods and theory of reliability. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1976, 163, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D.; Mellenbergh, G.J.; Van Heerden, J. The concept of validity. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 111, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, A.; Abu-Rubieh, Z.; Coll, L.; Matti, M.; Allaf, C.; Seff, I.; Stark, L. “Living their best life”: PhotoVoice insights on well-being, inclusion, and access to public spaces among adolescent refugee girls in urban resettlement. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2024, 20, 2431183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Suwaidi, M.; Furlan, R. The Role of Public Art and Culture in New Urban Environments: The Case of Katara Cultural Village. Archit. Res. 2017, 7, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Territory spatial planning and national governance system in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Ge, D.; Yuan, Z.; Lu, Y. Rural revitalization mechanism based on spatial governance in China: A perspective on development rights. Habitat Int. 2024, 147, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Rural vitalization in China: A perspective of land consolidation. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, L. Rural revitalization of China: A new framework, measurement and forecast. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 89, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, S.A.; Grace-Martin, K. Data Analysis with SPSS; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

| Impact Variable Dimension | Latent Variable | Abbreviation | Observed Variable | Description of Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Aesthetics | Art Innovation | AI | Application of Cutting-edge Concepts | Does the work reflect the latest art concepts or technologies? |

| Originality | Is it entirely based on original ideas, not adaptations or imitations? | |||

| Non-traditional Expression | Does it use unconventional methods, such as experimental installations or interactive technology? | |||

| Art Aesthetics | AA | Visual Appeal | Does the artwork attract the viewer’s attention at first glance? | |

| Balance of Proportions and Composition | Are the proportions of elements in the space or image harmonious? | |||

| Color Layering | Does the color scheme have rich layers, not just simple or flat tones? | |||

| Spatial Appearance Details | SDs | Distinct Regional Characteristics | Does the space have prominent local cultural features? | |

| Landscape and Architecture Coordination | Do the natural landscape and architectural design complement each other? | |||

| Corner Detailing | Are the corners and edges of the space finely crafted? | |||

| Tactile and Material Experience | Are the materials in the space carefully selected to offer a rich sensory experience? | |||

| Functional Suitability | Usability and Flexibility | UF | Clear Function Zone Distinction | Are different functional zones easy to identify and access? |

| User Intuition | Can users easily navigate the space without additional guidance? | |||

| Adaptability to Change | Can the space adjust to seasonal changes, such as temperature or ventilation? | |||

| Multi-scene Conversion Convenience | Can the space quickly transition for different uses (e.g., meetings to exhibitions)? | |||

| Functional Safety and Completeness | FC | Disaster Resistance | Does the space or building have disaster-resistant features (e.g., earthquake or fire resistance)? | |

| Protection for Children and Elderly | Does the space take into account the safety needs of vulnerable groups? | |||

| Long-term Safety Assurance | Does the space maintain safety over prolonged use? | |||

| Emergency Facility Accessibility | Are emergency facilities like first-aid kits or fire extinguishers easy to access? | |||

| Environmental Comfort Facilities | Do lighting or other facilities contribute to a comfortable environment? | |||

| Historical and Cultural | Cultural Integration Expression | CI | Coexistence of Multicultural Symbols | Do different cultural symbols coexist naturally within the space? |

| Cross-cultural Interaction Experiences | Does the space offer opportunities for cross-cultural exchange, such as interactive exhibits? | |||

| Symbolic Use of Signs | Are specific symbols used to convey deep cultural meanings? | |||

| Cultural Value Transmission | Does the artwork effectively communicate particular cultural values or concepts? | |||

| Element Extension | EE | Sustainable Design Concept | Does the design consider long-term use and sustainable development? | |

| Expansion of Design Language | Can the design language be continued in other projects? | |||

| Future Development Compatibility | Does the design leave room for future expansion or upgrades? | |||

| Emotional Cognition | Cultural Emotions | CEs | Individual Emotional Experience | Does the artwork or space evoke deep emotional responses in individuals? |

| Collective Memory Resonance | Does it resonate with the collective memory of a shared history or culture? | |||

| Emotional Persistence | Does the cultural emotion last long after the experience? | |||

| Emotional Depth Variety | Does the space or artwork evoke a variety of emotional responses, such as awe, nostalgia, or joy? | |||

| Satisfaction | Resident Satisfaction | RS | Overall Satisfaction | Residents’ overall evaluation of the public space. |

| Comparative Satisfaction | Residents’ satisfaction compared to similar public spaces. | |||

| Expected Satisfaction | Residents’ satisfaction compared to their expectations. |

| Category | Items | No. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 137 | 61% |

| Female | 87 | 39% | |

| Educational Background | Higher school or above | 175 | 78% |

| College degree | 45 | 20% | |

| Bachelor’s or above | 4 | 2% | |

| Age | 20 years and below | 69 | 31% |

| 20–50 years | 25 | 11% | |

| 50–60 years | 49 | 22% | |

| 60 years and above | 81 | 36% | |

| Occupation | Student | 72 | 32% |

| Farmer | 74 | 33% | |

| Worker | 47 | 21% | |

| Civil servant | 20 | 9% | |

| Self-employed | 7 | 3% | |

| Retired or other | 4 | 2% | |

| Monthly Average Income | 1000 or below | 119 | 53% |

| 1000–3000 | 56 | 25% | |

| 3000–5000 | 34 | 15% | |

| 5000 and above | 15 | 7% |

| Influencing Variable Dimension | Latent Variable | Number of Items | Alpha Coefficient | Overall Scale Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Aesthetics | Art Innovation (AI1–AI3) | 3 | 0.832 | 0.863 |

| Art Aesthetics (AA1–AA3) | 3 | 0.887 | ||

| Spatial Appearance Details (SD1–SD4) | 4 | 0.912 | ||

| Functional Suitability | Usability and Flexibility (UF1–UF4) | 4 | 0.807 | |

| Functional Safety and Completeness (FC1–FC5) | 5 | 0.867 | ||

| Historical and Cultural | Cultural Integration Expression (CI1–CI4) | 4 | 0.848 | |

| Element Extension (EE1–EE3) | 3 | 0.917 | ||

| Emotional Cognition | Cultural Emotions (CE1–CE4) | 4 | 0.831 | |

| Satisfaction | Resident Satisfaction (RS1–RS3) | 3 | 0.877 |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.931 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approximate Chi-Square | 9075.135 |

| Df | 403 | |

| sig | 0.000 | |

| NO. | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sum of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sum of Squared Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Variance % | Cumulative % | Total | Variance % | Cumulative % | Total | Variance % | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 8.698 | 29.990 | 29.990 | 8.698 | 29.990 | 29.990 | 4.212 | 14.357 | 14.357 |

| 2 | 3.423 | 11.802 | 41.792 | 3.423 | 11.802 | 41.792 | 3.421 | 11.795 | 26.152 |

| 3 | 2.032 | 7.006 | 48.798 | 2.032 | 7.006 | 48.798 | 3.049 | 10.512 | 36.664 |

| 4 | 1.829 | 6.306 | 55.104 | 1.829 | 6.306 | 55.104 | 2.881 | 9.933 | 46.597 |

| 5 | 1.784 | 6.151 | 61.255 | 1.784 | 6.151 | 61.255 | 2.655 | 9.514 | 56.111 |

| 6 | 1.502 | 5.178 | 66.433 | 1.502 | 5.178 | 66.433 | 2.351 | 8.366 | 64.477 |

| 7 | 1.450 | 2.965 | 69.398 | 1.450 | 2.965 | 69.398 | 1.893 | 4.218 | 68.695 |

| 8 | 1.292 | 2.423 | 71.821 | 1.292 | 2.423 | 71.821 | 1.325 | 2.767 | 71.462 |

| 9 | 1.181 | 1.982 | 73.803 | 1.181 | 1.982 | 73.803 | 1.062 | 2.341 | 73.803 |

| 10 | 0.975 | 1.762 | 75.565 | ||||||

| ... | |||||||||

| 33 | 0.210 | 0.064 | 100 | ||||||

| Path | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-RS | 0.232 | 0.113 | 0.345 |

| AA-RS | 0.183 | 0.090 | 0.273 |

| SD-RS | 0.259 | 0.126 | 0.385 |

| UF-RS | 0.287 | 0.136 | 0.431 |

| FC-RS | 0.275 | 0.081 | 0.356 |

| CI-RS | 0.182 | 0.101 | 0.283 |

| EE-RS | 0.264 | 0.871 | 1.135 |

| CE-RS | 0.490 | - | 0.490 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Standardized Parameter Estimate (Std.) | Critical Ratio (T-Value) | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | AI-RS | 0.232 | 5.156 | *** | Valid |

| H2 | AA-RS | 0.183 | 4.067 | *** | Valid |

| H3 | SD-RS | 0.259 | 5.756 | *** | Valid |

| H4 | UF-RS | 0.287 | 6.378 | *** | Valid |

| H5 | FC-RS | 0.275 | 6.111 | *** | Valid |

| H6 | CI-RS | 0.182 | 4.044 | *** | Valid |

| H7 | EE-RS | 0.264 | 5.867 | *** | Valid |

| H8 | CE-RS | 0.490 | 10.889 | *** | Valid |

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Standardized Factor Loadings | Observed Variable Weight | Observed Variable Satisfaction | Latent Variable Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Art Innovation (AI) | AI1 | 0.749 | 0.317 | 3.752 | 3.609 |

| AI2 | 0.808 | 0.342 | 3.517 | ||

| AI3 | 0.805 | 0.341 | 3.569 | ||

| Art Aesthetics (AA) | AA1 | 0.740 | 0.337 | 3.365 | 3.450 |

| AA2 | 0.734 | 0.334 | 3.522 | ||

| AA3 | 0.725 | 0.329 | 3.463 | ||

| Spatial Appearance Details (SDs) | SD1 | 0.800 | 0.252 | 3.799 | 3.519 |

| SD2 | 0.818 | 0.257 | 3.324 | ||

| SD3 | 0.772 | 0.243 | 3.598 | ||

| SD4 | 0.789 | 0.248 | 3.358 | ||

| Usability and Flexibility (UF) | UF1 | 0.795 | 0.254 | 3.920 | 3.491 |

| UF2 | 0.814 | 0.260 | 3.967 | ||

| UF3 | 0.711 | 0.227 | 2.965 | ||

| UF4 | 0.812 | 0.259 | 3.054 | ||

| Functional Safety and Completeness (FC) | FC1 | 0.816 | 0.208 | 4.000 | 3.907 |

| FC2 | 0.769 | 0.196 | 3.811 | ||

| FC3 | 0.699 | 0.179 | 3.802 | ||

| FC4 | 0.815 | 0.208 | 3.902 | ||

| FC5 | 0.816 | 0.208 | 4.000 | ||

| Cultural Integration Expression (CI) | CI1 | 0.698 | 0.226 | 3.687 | 3.734 |

| CI2 | 0.832 | 0.269 | 3.421 | ||

| CI3 | 0.799 | 0.258 | 3.987 | ||

| CI4 | 0.765 | 0.247 | 3.852 | ||

| Element Extension (EE) | EE1 | 0.836 | 0.365 | 3.654 | 3.671 |

| EE2 | 0.874 | 0.382 | 3.461 | ||

| EE3 | 0.702 | 0.253 | 4.011 | ||

| Cultural Emotions (CEs) | CE1 | 0.829 | 0.301 | 3.942 | 3.970 |

| CE2 | 0.763 | 0.278 | 4.105 | ||

| CE3 | 0.712 | 0.242 | 3.902 | ||

| CE4 | 0.690 | 0.179 | 3.910 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, P.; Zhang, W. Intervention and Co-Creation: Art-Led Transformation of Spatial Practices and Cultural Values in Rural Public Spaces. Land 2025, 14, 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071353

Li P, Zhang W. Intervention and Co-Creation: Art-Led Transformation of Spatial Practices and Cultural Values in Rural Public Spaces. Land. 2025; 14(7):1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071353

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Peiyuan, and Wencui Zhang. 2025. "Intervention and Co-Creation: Art-Led Transformation of Spatial Practices and Cultural Values in Rural Public Spaces" Land 14, no. 7: 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071353

APA StyleLi, P., & Zhang, W. (2025). Intervention and Co-Creation: Art-Led Transformation of Spatial Practices and Cultural Values in Rural Public Spaces. Land, 14(7), 1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071353