1. Introduction

Under the rapid development of globalization, urbanization, industrialization, and agricultural modernization [

1], the interaction and entanglement between society and nature, human and non-human, rural and non-rural, and local and global are constantly reshaping rural areas [

2]. China has consistently placed rural development at the strategic forefront of national priorities. The Chinese central government’s annual “Document No. 1” for 20 consecutive years has focused on “three rural issues”: farmers or peasants (nongmin), rural society or villages (nongcun), and rural production or agriculture (nongye) [

3,

4], unswervingly implementing key strategies to retain priority of rural development in terms of personnel allocation, resource integration, capital investment, and public service provision. Meanwhile, the openness of rural space in China has caused the boundary between rural and urban areas to blur, which has promoted an increasingly close relationship. In essence, it has facilitated the flow of population, information, technology, capital, ideas, and other factors [

5], thereby fundamentally transforming the dualistic urban–rural structure [

6]. In the context of the new development paradigm, the central government intends to coordinate national modernization and rapid urbanization by directly optimizing the rural institutional environment, reconfiguring rural territory development elements, improving infrastructure, providing enough public services, and more. These efforts aim to promote economic development, eradicate poverty, and ultimately revitalize rural areas.

Since the turn of the new millennium, vast rural areas in China, as an important part of the countryside worldwide, have experienced drastic change and multidimensional restructuring in economic modes and spatial layouts [

7,

8]. They are no longer considered areas doomed to decline but rather demonstrate sustainability, vitality, and resilience. Distinctively, the transition from productivism to post-productivism in rural areas is a global trend, and China is no exception [

9]. Under the policy background of coordinated regional development, the Chinese government has implemented a series of policy measures such as the “Rural Revitalization Strategy,” the “Common Prosperity Strategy,” and the “Western Development Strategy,” guiding rural areas in the western region to gradually transform from primary development relying solely on local resources to characteristic industries with regional competitiveness [

10]. This has effectively advanced economic growth, social progress, and ecological sustainable development in these regions. It has promoted the transformation of rural space from a single-function focus on agricultural production to multifaceted, integrative functions such as residence, leisure, entertainment, education, environmental protection, and other consumption-oriented functions [

11,

12]. Rural space has gradually been rediscovered and repackaged as consumer destinations, and the creation of economic value has tilted from agricultural production to non-agricultural industries, transforming into a multifunctional space that integrates production, consumption, and protection [

13,

14]. China’s rural spaces are experiencing continuous and multifaceted restructuring processes. Among these transformations, the most profound structural shift involves the transition from agricultural production-dominated economies to market-oriented spatial economies—a phenomenon conceptualized as rural spatial commodification [

15,

16].

Some studies have been conducted on rural spatial commodification both domestically and internationally, and the existing body of results provides a good research approach and empirical foundation for this article [

12,

15,

16]. However, the existing domestic research predominantly focuses on the plain rural areas around the developed regions in the eastern part of China or the plain rural areas surrounding the suburbs of large cities, while research on rural spatial commodification in the mountainous region of southwest China remains relatively scarce. With the steady improvement of the regional economic development and the penetration of the post-productivism concept in the mountainous region of southwest China, the increasingly close interaction between rural space and multiple actors has gradually highlighted the commercial value, creating favorable conditions for rural spatial commodification. In contrast to the developed plain rural areas in the eastern region, the mountainous region of southwestern China is constrained by large-scale labor force outflow, weak and inadequate infrastructure construction, and a backward and sluggish marketization level. As a result, the development of rural spatial commodification in these areas is more arduous and complex.

Furthermore, the existing literature on rural spatial commodification demonstrates considerable strengths in theoretical synthesis, analytical dimensionality, and practical application. Nevertheless, they suffer from persistent limitations, including case selection bias, insufficient mechanistic analysis, and deficient interdisciplinary synergy. On the one hand, by leveraging Western academic frameworks such as Lefebvre’s space production theory for in-depth analysis, and fully considering the policy and institutional context in which the case sites are located, unique advantages are formed especially in terms of theoretical integration and analysis depth, advancing the alignment between theory and indigenous policy contexts. On the other hand, due to the limitations of case sampling, the coverage of mountainous villages and underdeveloped villages is insufficient. Furthermore, the lack of systematic, multidimensional analysis makes it difficult to comprehensively reveal the practical logic underlying rural spatial commodification. Integrating multidisciplinary perspectives, this study employed longitudinal observation of a village in the mountainous region of southwest China to examine the micro-dynamics of policy implementation, elite exploration, villager participation, and market penetration. It precisely captured the phased evolution patterns and dynamic response mechanisms in the process of rural spatial commodification, and constructed a more interpretive analytical framework for systematically revealing its complex internal mechanisms.

Conducting a systematic study on typical cases of rural spatial commodification in the mountainous region of southwest China is one of the challenging issues faced in promoting the comprehensive revitalization of rural areas and achieving common prosperity. This study focuses on Zhongxin Village, located in the mountainous region of Guizhou Province, China—a typical village where the development of the agate red cherry characteristic industry drives rural spatial commodification. Rural spatial commodification has gradually expanded from the individual spatial resources to the rural space itself, transforming the rural space into a “commodity” with economic value.

Thus, in such a typical rural village in the mountainous region of southwest China, what stage of evolution has rural spatial commodification undergone? How do multiple actors drive rural spatial commodification? What are the structural dilemmas and viable strategies in the process of rural spatial commodification? These questions constitute the core concerns of this study.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 constructs an analytical framework suitable for rural spatial commodification in the mountainous region of southwest China based on the cross-integration of spatial production theory and rural space commodification.

Section 3 elaborates on the study area and research methods.

Section 4 focuses on characterizing the three evolutionary stages of rural spatial commodification and their driving factors.

Section 5 examines the key driving factors and structural dilemmas of rural space commodification, while putting forward viable strategies. The final section briefly discusses the study’s academic implications, practical implications, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Spatial Production Theory and Rural Spatial Commodification

The theoretical foundation for rural spatial commodification can be traced back to the 1970s. The “theory of spatial production” was groundbreakingly proposed by French scholar Henri Lefebvre in his book ‘The Production of Space’. Lefebvre proposed the core concept that “(social) space is a (social) product” [

17]. Space, in essence, serves as a container, a product of material and social practices, which can be continuously manufactured and remanufactured through the processes of production and consumption [

12,

18]. Cloke further proposed that people utilize the rural environment to meet the needs of contemporary consumption. Throughout this ongoing dynamic process, the primary function of rural space based on agricultural production is relatively weakened, while its role in consuming non-material products is becoming increasingly prominent. Various products, along with the rural space itself, are opening up to the market, trending toward “commodity” consumption. This transformation of rural space from a single production function to a multifunctional space constitutes the commodification of rural spaces [

19,

20,

21]. Woods emphasized that rural spatial commercialization entails the opening of various rural commodities to the market. These commodities are sold or purchased via various consumption practices, such as tourism, real estate investment by non-agricultural personnel, the sale of rural products, and the utilization of rural imagery to promote agricultural products and other commodities, thereby achieving the goal of “selling” rural resources [

22,

23]. Perkins believed that the commodification of rural space is a dynamic process in which local villagers, producers, tourists, and other actors are involved in various ways to address specific situations and circumstances. The actors focus on the dynamic interplay of rural protection and transformation centered on the consumption-oriented economy. Additionally, its forms and contents vary from place to place [

24]. Rural spatial commodification, as a cutting-edge concept that has emerged both domestically and internationally in recent years [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], is regarded as an important strategy for solving the dilemma of rural development and is deeply integrated into the practical process of rural revitalization.

In China, rural areas serve as the fundamental unit of the rural economy, society, and culture [

25,

26], with a unique geographical endowment and development environment [

27]. The stability and development of rural areas are crucial for the development of the country and society [

28]. The interaction between villagers and the land gives birth to intricate social relations, while also fostering deep integration of space. Rural space serves as a vital venue for villagers’ habitation, and it is also a crucial platform for villagers to carry out extensive productive practices and daily living activities [

25]. Rural spatial commodification is widely recognized as a crucial approach to addressing the challenges of rural development and a path to achieving rural revitalization. Although the research on rural spatial commodification in China started relatively late, it has already yielded abundant academic findings and practical experience, and it is becoming increasingly widespread and diversified. Some domestic scholars have focused on the main forms of non-agricultural consumption activities in rural areas around metropolises, mainly in the forms of Nong Jia Le [

29,

30], agricultural sightseeing [

31], and leisure experiences and homestays [

32,

33], emphasizing that rural spatial commodification is the result of rural areas’ adaptation to the changes in urban consumption concepts and habits. Existing research indicates that, influenced by a series of political, economic, and social forces, rural areas in China are transforming from spaces specialized in primary agricultural production into spaces that market an increasing array of non-traditional agricultural products (such as lifestyles, leisure experiences, and environmental services). The commodification of rural space is, in essence, the commodification of rural elements. The intangible, virtual, and comprehensive “products” created by relying on the physical entities in rural areas possess higher exchange value, exerting a more profound impact on local socioeconomic conditions.

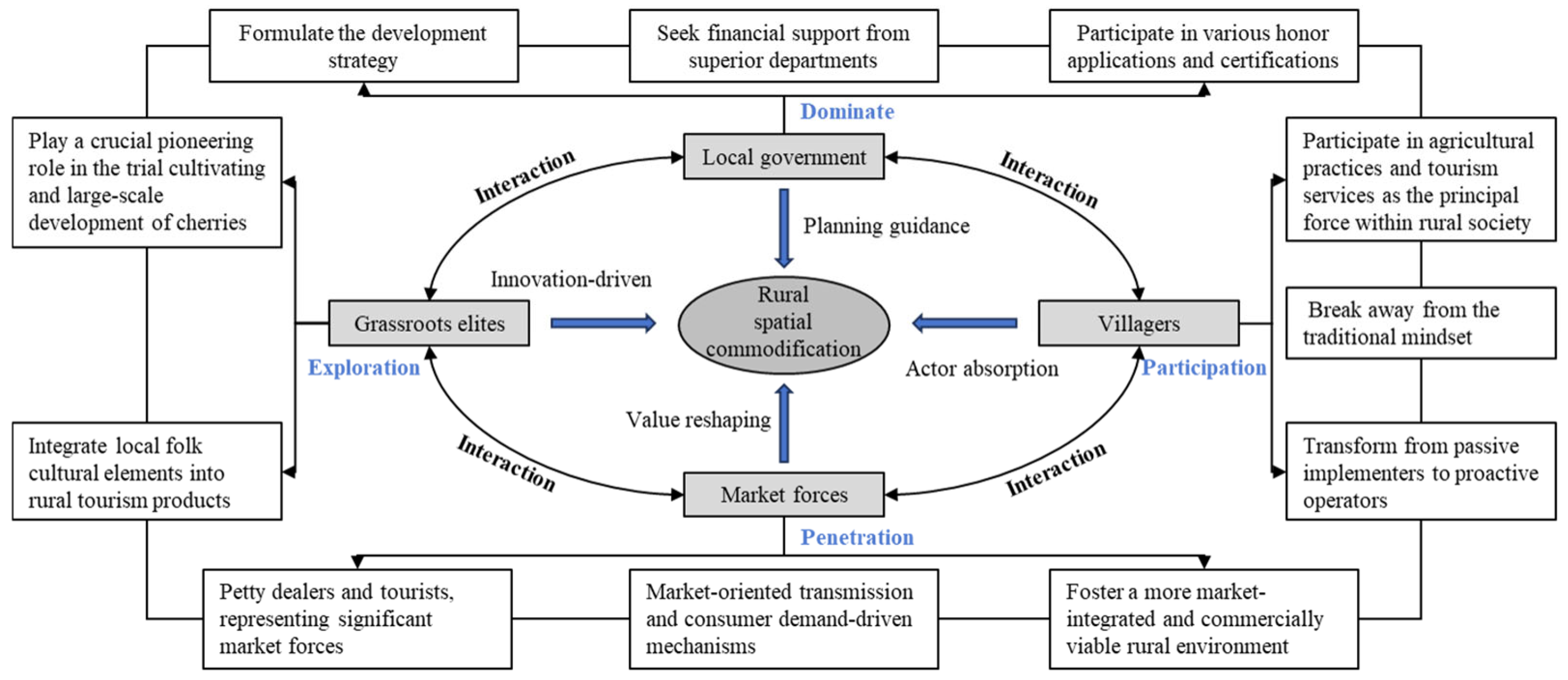

Lefebvre’s triadic dialectical framework for spatial production, centered on the three core dimensions of spatial practices, representations of space, and representational spaces, offers both theoretical applicability and practical feasibility for deconstructing the intrinsic logic of spatial commodification in the mountainous region of southwest China through its triadic narrative framework [

34]. Specifically, spatial practices refer to the perceived space of rural areas, constituting a material–practical realm that encompasses activities and outcomes of spatial production and reproduction by rural communities and individuals. Representations of space refer to the spatial conception of rural areas. As a conceived space, it means the strategic conception and symbolic shaping of rural spaces by dominant rulers through power, knowledge, and capital apparatuses, such as policy systems, planning designs, and marketing advertisements. Representational spaces encompass the lived space of rural areas, constituting a meaning–experiential realm where rural inhabitants produce social relationships through their interaction with the environment, grounded in local knowledge, emotional memory, and daily experience. Against this backdrop, the authors constructed a “tripartite integrated” narrative framework for rural spatial commodification (as shown in

Figure 1), which serves to elucidate the underlying logic of rural space commodification in the southwestern mountainous region.

Halfacree’s three-fold architecture of rural space innovatively deconstructs rural spatiality into three interwoven dimensions: rural locality, representations of the rural, and everyday lives of the rural [

35]. Rural Locality foregrounds spatially embedded practices that construct place-specific identities through production and interaction (e.g., productive landscapes, infrastructure systems). Representations of the Rural examine the symbolic mediation of rural space under capitalist production and exchange logics (e.g., spatial configurations, industrial zoning patterns). everyday lives of the rural highlights how rural residents interpret space by integrating personal experiences and social relations into daily practices [

36,

37].

As depicted in the narrative framework in

Figure 1, Lefebvre’s triadic dialectical framework for spatial production, which comprises perceived space (spatial practices), conceived space (representations of space), and lived space (representational spaces), provides a pivotal analytical framework for interpreting rural spatial commodification. Within the context of coupled development between rural characteristic cultivation and tourism, rural spatial commodification manifests through a synergistic functioning mechanism across three dimensions: The perceived space constitutes the material basis and practical starting point for rural spatial commodification. In specific practice, through the commercial transfer of perceivable material elements such as the rural spatial pattern, natural landscape, agricultural landscape, lifestyle of living carriers, and infrastructure, the fundamental position of agricultural production is consolidated while meeting tourists’ demands for rural space that carries the symbol of “rurality.” The conceived space constructs the institutional framework and discourse system for rural spatial commodification. It provides policy support for rural spatial commodification through the formulation of development plans and supportive documents. Simultaneously, it forges a distinctive rural space with local identity by creating culturally symbolic and event-based activities that reflect local characteristics. The lived space constitutes the practical identification and interactive carrier for rural spatial commodification. Through the daily productive practices, social interaction rituals, and local emotional connections of villagers, it not only provides social cohesion for the process of spatial commodification but also prevents the erosion of authenticity caused by excessive expansion beyond the boundary of local identification. The coupled development of rural characteristic cultivation and tourism constructs a support system for rural spatial commodification through the synergistic interplay of three dimensions: material practices, institutional discourses, and social identification.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

Based on the existing literature review above, this study synthesizes the theoretical frameworks of rural space commodification with China’s rural development practices, contending that the essence of rural spatial commodification fundamentally lies in the following: Within the framework of Chinese socialist market economy, multiple actors creatively leverage local resources—encompassing material elements such as land, housing, agricultural products, and landscapes (natural/cultural), alongside intangible elements, including rural experiences, cultural heritage, service provision, and spatial imaginaries—transforming various rural spatial components into repeat-tradable “commodities,” so as to achieve the goal of “selling” rural continuously and dynamically. Given the distinctive constraints of complex topography, ecological fragility, and underdeveloped infrastructure in the mountainous villages of southwest China, the unfolding rural spatial commodification process is critically contingent on effective collaborative synergy among multiple actors. The unfolding rural spatial commodification process is critically contingent on effective collaborative synergy among multiple actors.

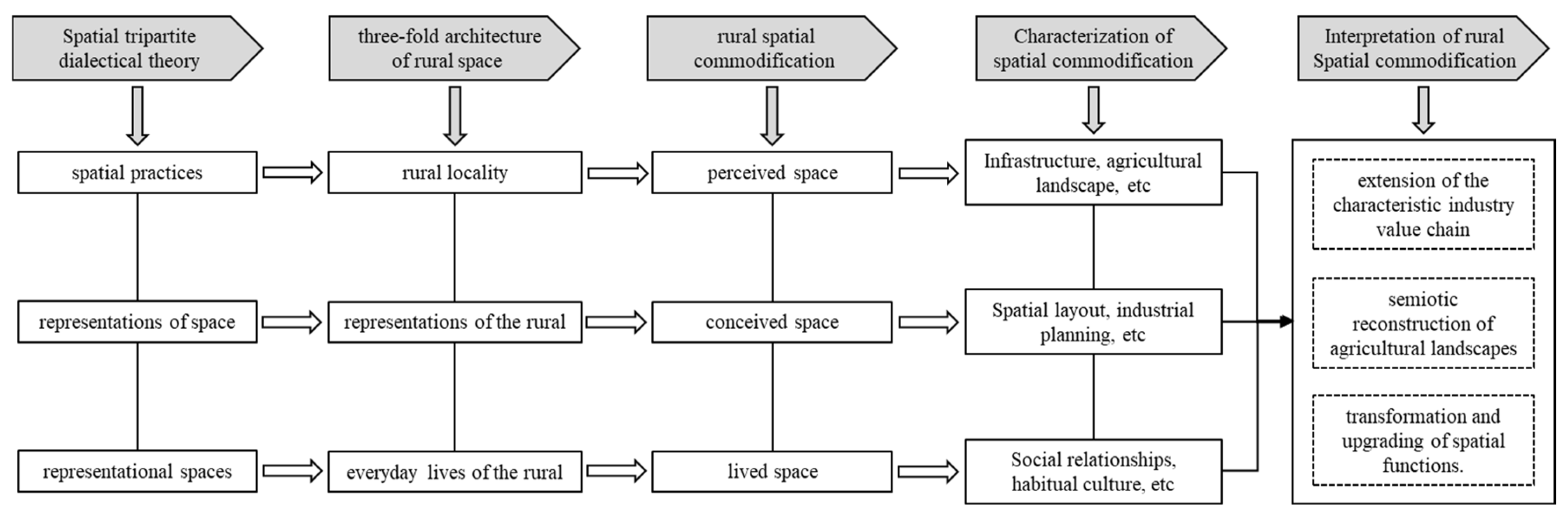

Multi-actor collaboration refers to the coordination among the government, enterprises, market entities, non-profit organizations, grass elites, and villagers. By transcending the limitations of individual actors’ resource endowments and capabilities, this approach establishes a collaborative network that facilitates resource sharing, knowledge exchange, risk diversification, and value co-creation. They collaboratively work to break through the development bottlenecks in rural areas. Currently, in the mountainous region of southwest China, multi-actor collaboration is facilitating the deep integration of rural tourism with complementary commodification practices. This approach strikes an optimal balance between development and conservation, significantly enhancing the exchange value of rural spaces. It has emerged as the most effective approach to rural spatial commodification in the region.

Moreover, this study, taking Zhongxin Village of Guizhou Province as a case study, and based on the data collected by methods such as participatory observations and semi-structured interviews, analyzes the evolution and characteristics of rural spatial commodification over the past three decades. Grounded in an empirical case study, this research demonstrates that spatial commodification constitutes not an abstract phenomenon but a co-produced outcome forged by multiple actors through place-embedded practices. Consequently, the authors delineate four core cohorts driving rural spatial commodification: local governments, grassroots elites, villagers, and market forces. Specifically, local government mainly refers to administrative apparatuses at the county and township levels, which fulfill roles such as policy facilitation, spatial planning, and resource orchestration throughout rural spatial commodification. Grassroots elites encompass groups such as local gentry, large-scale planters, returned intellectuals, and entrepreneurs. Relying on place-based knowledge, social capital networks, and embedded influence, they orchestrate and propel spatial commodification through organizational mediation and demonstrative agency. Villagers, as the most direct practical subject of rural space, configure the endogenous sustainability of spatial commodification through adaptive recalibration of livelihood strategies and depth of participation. Market forces, primarily seasonally embedded exogenous actors, including cherry buyers/distributors and tourist groups, activate the potential value of rural spaces through demand stimulus and consumption-driven mechanisms. By analyzing the positioning and interactive dynamics of these four core actors within the spatial commodification process of the case study area, this research aims to reveal the complex mechanisms through which multiple actors collectively drive rural spatial commodification.

Building upon this foundation, this study constructed an analytical framework suitable for rural spatial commodification in the mountainous region of southwest China, as shown in

Figure 2. The analytical framework is anchored in the unique geographical environment and socioeconomic context of the southwestern mountainous region, while being embedded in national strategic contexts such as Rural Revitalization, Common Prosperity, and Western Development Strategy. Against the contextual foundation above, multiple actors—including local governments, grassroots elites, ordinary villagers, and market forces—engage in collaborative interaction. By systematically integrating and intensively developing both endogenous and exogenous resources in rural spaces, they propel the extension of the characteristic industry value chain, the semiotic reconstruction of agricultural landscapes, and the transformation and upgrading of spatial functions. This spatial transformation, facilitated through pathways such as spatial structure optimization, spatial value enhancement, and spatial functional upgrading, transmutes rural spatial resources from inherent endowments into market-oriented commodities. Thereby, an analytical perspective was established for interpreting rural spatial commodification in the southwestern mountainous region.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Study Area

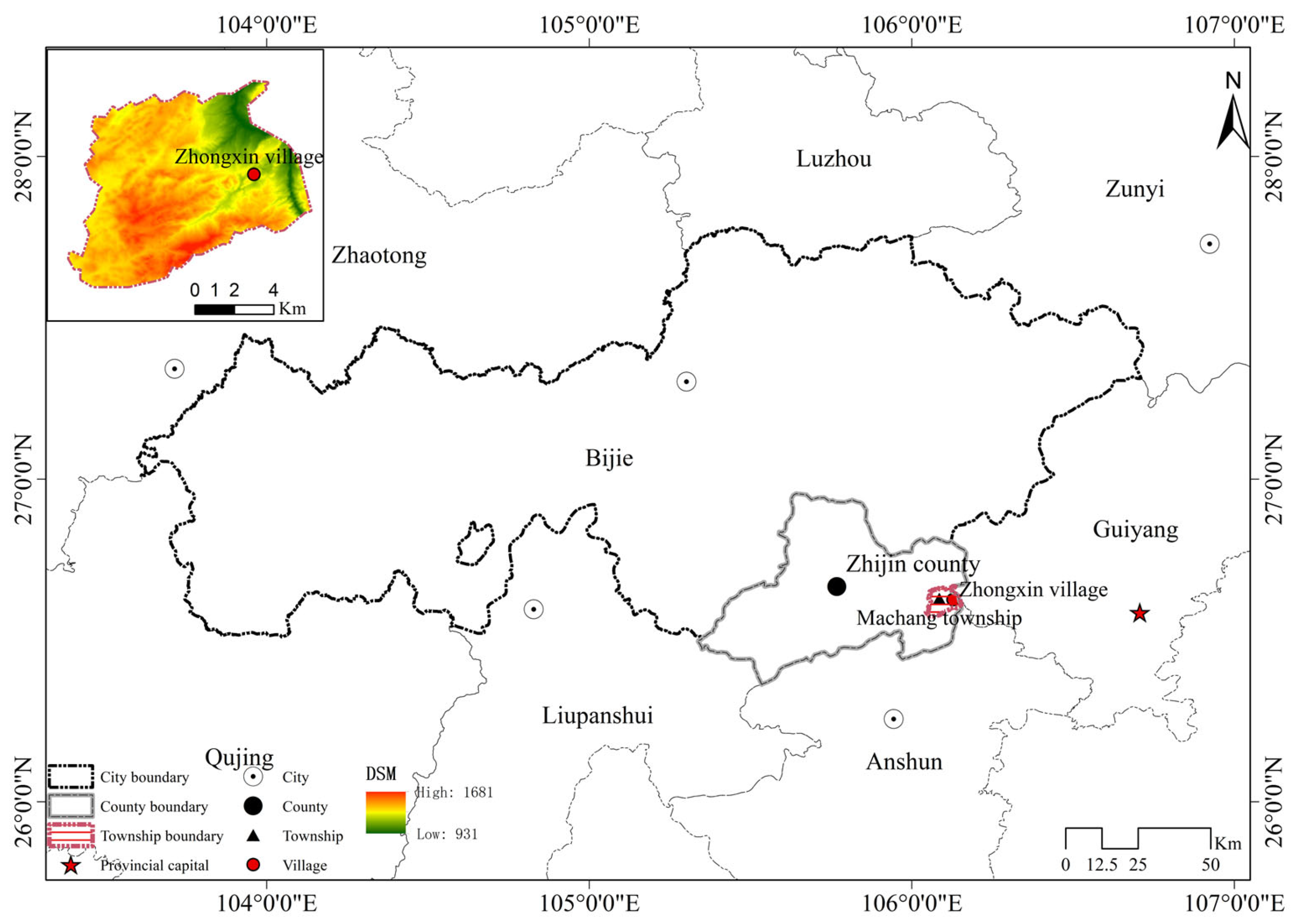

Zhongxin Village is located in Machang Township, Zhijin County, Bijie City, Guizhou Province (as shown in

Figure 3). The total land area of the village is 7.3 square kilometers, where the area of woodland and cultivated land is 1973.9 and 2279 mu, respectively. There are 8 village groups under its jurisdiction, with a registered population of 2237, and the per capita disposable income reaches CNY 9000 per year. Zhongxin Village is located on the banks of the canyon in the Wahe River Basin, upstream of the Wujiang River. With an average altitude of 1395 m, the temperature, vegetation, and other aspects within the village area show a certain three-dimensional vertical pattern.

Zhongxin Village is situated in a typical karst-landform-developing area in the mountainous region of southwest China. Despite being endowed with superior natural resources, local industrial development faces numerous challenges due to factors such as fragmented and infertile land, weak industrial foundation, isolated geographical conditions, lagging infrastructure, and fragile ecological environment. Before the cherry industry achieved large-scale development, relying solely on traditional farmland cultivation made it difficult to maintain a stable level of basic subsistence. The base of the poverty-stricken population was relatively large, and the task of poverty alleviation was arduous and complex. The underdeveloped socioeconomic conditions have compelled a significant outflow of rural youth, and the continuous loss of labor resources has accelerated the process of rural hollowing. This, in turn, has triggered the intertwining and compounding of multiple issues, including farmland abandonment, economic contraction, infrastructure abandonment, and psychological distress among the left-behind population. To reverse its declining trend, Zhongxin Village, through continuous exploration and practice, has completed the transformation from traditional farming to characteristic industry and spatial commodification. Over the past three decades, the cherry industry has demonstrated remarkable characteristics of large-scale operation and market orientation, attracting substantial support from agricultural-friendly policies and project resources and injecting new vitality into the village economy. The practice of spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village has provided significant theoretical insights and practical references for the transformation and evolution of traditional agricultural villages, demonstrating certain exemplary significance and research value.

Considering the significance of its natural resource endowments, socioeconomic characteristics, and other factors, Zhongxin Village, as a representative of rural spatial commodification driven by industrial transformation and development in a mountainous region, fits well with the research topic of this study. The village was selected as a typical case study for the following reasons: (1) Zhongxin Village stands as one of the quintessential examples of characteristic industrial development in the mountainous region of southwest China, bearing significant research value. For a considerable period, Zhongxin Village was predominantly engaged in traditional agricultural cultivation, with low agricultural added value, and the development of its characteristic industries exhibited traits of sluggishness, tortuousness, and lag. In recent years, relying on policy and the institutional environment, as well as the operation of project resources, Zhongxin Village has vigorously developed the cherry characteristic industry and integrated agriculture with tourism, emerging as a typical demonstration village for rural revitalization in Guizhou Province. (2) The majority of its villagers have long inhabited Zhongxin Village, possessing a comprehensive understanding of the village’s basic situation, which is convenient for researchers to carry out investigations. In terms of the convenience of investigation, Zhongxin Village has significant advantages: First, village cadres have extensive rural work experience and are well-versed in the village’s circumstances, which provides comprehensive and accurate information guidance for the investigative work. Second, the relatively concentrated residences of the villagers make it convenient for researchers to carry out interviews, participatory observations, and other activities, enhancing the efficiency and comprehensiveness of the investigation.

Between 2022 and 2024, researchers conducted extensive field investigations in Zhongxin Village to deeply analyze the important issue of rural spatial commodification in the mountainous region of southwest China. With the full assistance of village cadres and the active cooperation of villagers, a systematic analysis of the typical case of Zhongxin Village was carried out to gain an in-depth insight into the underlying logic behind the process of rural spatial commodification in the mountainous region of southwest China.

3.2. Material Collection and Analysis

Based on field research conducted in Zhongxin Village from June to September 2022, and partially in 2023 and 2024, primary and secondary information were collected through on-the-spot investigations. This included data on farmers’ basic demographics, industrial layout, living and production styles, and rural tourism development status. The following primary information was mainly collected through participatory observations and semi-structured interviews: (1) Through field inspections of the village’s appearance, lifestyle, local customs, industrial base, and landscape change, the observed information was recorded and organized into a text document totaling 15,000 words, alongside a large number of photographs documenting the study area and paper-based textual materials; (2) a semi-structured interview outline was formulated, focusing on industrial changes, cherry industry development, rural tourism promotion, and other issues. Based on the principle of maximum differentiation, interviewees were selected by comprehensively considering various factors such as age, gender, identity, education level, and degree of industrial participation. In this study, a total of 35 people were interviewed (as detailed in

Table 1). The interview time for each interviewee varied from 30 min to 1.5 h. After the interviews, 58,000 words of interview text were obtained according to the recorded notes. Secondary information was mainly collected and organized from historical documents, official government websites, news reports, WeChat official account posts, Douyin videos, etc., with a focus on industrial transformation and rural tourism development in Zhongxin Village.

Through systematic sorting of the primary information obtained from the field investigation, the in-depth exploration of interview content, and the meticulous screening of secondary information, the authors strived to accurately and comprehensively grasp the evolution of Zhongxin Village across various historical periods, as well as the changes in production mode, industrial structure, social structure, spatial commodification, and other aspects at different stages, providing a solid and reliable information foundation for this study.

This study adhered to the logical progression of “data collection—method adaptation—dimension construction—theoretical articulation,” integrating multi-source qualitative materials to establish an analytical framework that facilitated dynamic dialogue between field experience and abstract theory. First, in-depth interview records, participant observation logs, policy documents, and visual materials obtained through fieldwork were systematically transcribed to establish a textual database. Subsequently, a discourse analysis matrix was utilized to cross-validate the narrative accounts provided by different interviewees concerning the same critical event. During the data processing phase, the textual materials underwent progressive conceptualization and categorization. Guided by the theoretical framework, structured thematic extraction was performed to establish three anchoring analytical dimensions covering policy context, actor interactions, and spatial practices. The original materials were also systematically classified into the corresponding dimensions. Ultimately, by thoroughly exploring the logical connections between different dimensions, this study identified key events and transition points in the process of rural spatial commodification and generalized the three-stage evolution characteristics of rural spatial commodification.

4. Results

Through the systematic summarization and analysis of the research materials, the researchers clearly discerned that the process of rural spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village was not accomplished in a single action; rather, it exhibited a trend of gradual advancement, dynamic development, and continuous evolution. This study categorized the evolution process of rural spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village into three key stages from four dimensions: dominant industries, dominant forces, landmark events, and result presentation. The landmark events for dividing stages are as follows: (1) In 1993, a small number of grassroots elites in Zhongxin Village first attempted to plant Baihua peaches, an economically valuable fruit tree. After several years of promotion and development, the planting area rapidly expanded to approximately 300 mu, laying a solid foundation for the cultivation of economically valuable fruit trees in the region. (2) In 2008, the Ziqiang Hydropower Station construction project commenced. As part of the compensation and resettlement plan for villagers affected by land acquisition and demolition, the local government provided cherry saplings to rural households, which initiated the preliminary exploration of characteristic agricultural planting and laid the foundation for the subsequent large-scale development of the industrial structure. (3) In 2014, with the in-depth implementation and comprehensive implementation of the Grain for Green Program, and driven by the effective incentives of related subsidy policies, an increasing number of farmers in Zhongxin Village joined the field of cherry cultivation. Gradually, a large-scale production pattern and market-oriented sales channels were formed. (4) In 2019, after years of exploration and promotion, the cultivation of agate red cherries achieved full coverage in Zhongxin Village. With the upward trajectory of the planting scale, the persistent refinement of planting technology, and the progressive broadening of sales channels, the cherry industry has become increasingly prominent in the economic landscape of Zhongxin Village and even the entire Wahe area. It has firmly established itself as a cornerstone industry that propels local economic growth, empowers villagers to boost their income, and paves the way for prosperity. (5) In 2020, an aerial video showcasing the spectacular landscape of the terraced flower sea in Zhongxin Village attracted extensive attention on the Douyin platform, and a great number of tourists flocked to Zhongxin Village for sightseeing and leisure. Zhongxin Village accurately captured the opportunities for rural tourism development, actively implementing projects such as infrastructure construction, the village’s aesthetic appeal enhancement, and tourism reception facilities improvement, thus officially embarking on the characteristic development path of “agriculture–tourism integration”.

Over the past three decades and more, Zhongxin Village has promoted the transformation and development of its industries in line with local conditions. It has successfully transformed from a single traditional agricultural production area to a composite sightseeing destination, continuously deepening the process of rural spatial commodification. Based on the research materials, the evolution of spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village can be divided into three development stages in chronological order, namely, the initial stage (1993–2007): the supply of agricultural products; the development stage (2008–2019): the construction of the terraced flower sea landscape; and the deepening stage (2020–present): the development of agriculture–tourism integration (as shown in

Figure 4).

4.1. The Supply of Agricultural Products: Initial Stage of Spatial Commodification (1993–2007)

The villagers, who have deep ancestral roots in this area, formed a “self-sufficient” small-scale peasant economy based on the cultivation of food crops such as rice and corn, supplemented by raising livestock and poultry such as pigs, cows, sheep, chickens, ducks, and geese.

In 1993, some grassroots elites in Zhongxin Village—driven by innovative thinking and forward-looking vision—had keen insight into the clear limitations of traditional food crop cultivation in terms of increasing family economic income, and they promptly embarked on exploring new approaches for cash crop cultivation. They discovered through practical exploration that grafting Baihua peaches could yield considerable economic benefits. Under the influence of this demonstration effect, the surrounding villagers followed suit one after another, spontaneously carrying out pruning and grafting of peach trees. In just a few years, the planting area of peach trees rapidly expanded to over 300 acres. At the same time, to highlight the unique landscape of the peach blossoms along the Wahe River, a song titled “Peace Blossoms in Wahe in Bloom” was released, which gradually evolved into an important medium for promoting Wahe’s characteristic industries and has continued to this day. During the later stage of Baihua peach cultivation development, the absence of stable and widespread sales channels made it challenging to turn the produce into a sustainable household income. Faced with an input–output imbalance, the villagers ultimately had no choice but to give up this cultivation model.

At this stage, the primary manifestation of spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village was that, under the demonstration, leadership, follow-up, and collaborative response of ordinary villagers, the combined efforts drove the transformation of agricultural product supply. Although traditional grain crop cultivation still maintained a dominant position at the time, the villagers had already begun to develop a subjective awareness of transitioning to cash crop cultivation and spontaneously initiated a series of exploratory attempts focused on cash crops in practice. From the perspectives of cognitive concepts and practical experience, this laid crucial groundwork for the in-depth advancement of rural spatial commodification in the future.

4.2. The Construction of a Terraced Flower Sea Landscape: Development Stage of Spatial Commodification (2008–2019)

In 2008, construction of the Ziqiang Hydropower Station began. Prior to this, the peasants in Zhongxin mostly earned their livelihoods through growing corn and rice, as well as working outside the village. During construction, the local government purchased agate red cherry saplings for peasants to plant in order to provide subsidies for land compensation and resettlement.

Particularly crucial is that since 2014, leveraging the long-term financial subsidy mechanism of the Grain for Green Program, the local government, through meticulous scientific planning and strategic layout, has efficiently and systematically promoted the development of cherry cultivation toward a trajectory of scale and industrialization in Zhongxin Village. As shown in

Figure 4, the income level of the villagers in Zhongxin Village exhibited a notable downward trend over the consecutive years following 2014. This can be attributed to the village’s robust implementation of the Grain for Green Program; in response, the villagers actively engaged in large-scale cherry cultivation. Given that cherry cultivation follows a distinct growth cycle, it takes three years to first bear fruit and produce economic benefits after planting. During this interval, as the scale of traditional agricultural planting diminished and the emerging cherry industry had not yet started generating income, the transition gap between the old and new industries resulted in a decline in the villagers’ income. In the initial phase of cherry cultivation, when the villagers’ incomes witnessed a phased decline, the long-term financial subsidy mechanism of the Grain for Green Program played a crucial buffering role. Such strategic financial injections effectively alleviated the income shortfall resulting from the shift in agricultural practices, eased the economic pressure on the villagers, and also provided financial support for the cherry industry’s transition and flourishing in Zhongxin Village.

As of 2019, agate red cherries have covered the entire area of Zhongxin Village and become the dominant industry. Over the past decade, under the combined influence of multiple factors such as leadership by local government, infiltration of petty dealers, and participation of villagers, agate red cherry, as an emerging cash crop, has expanded from the initial small-scale trial with just dozens of plants to full coverage within the village area steadily and systematically, thus successfully realizing localized cultivation in Zhongxin Village. As a result, this collective effort created a distinctive and breathtaking terraced flower sea landscape, successfully and significantly promoting the degree of rural spatial commodification.

4.3. The Development of Agriculture–Tourism Integration: Deepening Stage of Spatial Commodification (2020–Present)

In 2020, an aerial video showcasing the terraced flower sea landscape in Zhongxin Village swiftly went viral on the emerging media platform Douyin, captivating widespread public attention. Driven by the dissemination effect of the video, a large number of tourists flocked to Zhongxin Village within a brief span, significantly enhancing the village’s visibility and influence. Capitalizing on this unique opportunity and leveraging the collective strength of multiple actors, through continuous exploration and innovation in practical endeavors, Zhongxin Village deeply implemented the development path of agricultural–tourism integration. Consequently, Zhongxin Village rose to be a significant example in the mountainous region of southwest China.

During the annual cherry blossom period and fruit ripening period since 2020, hordes of tourists from Guiyang, Anshun, Bijie, and various other regions both within and outside the province have flocked here. Tourists come either to admire the cherry blossom landscape or participate in picking activities, thus giving rise to a rural tourism destination that highlights the unique regional characteristics. According to the relevant official statistics, it receives upward of 100,000 tourists annually, with tourism-related revenues surpassing CNY 6 million. Additionally, the revenue from cherry sales further augments the villagers’ income, thus laying a solid groundwork for the sustainable development of the rural economy. Grassroots elites were the first to recognize the potential driving force of the abrupt increase in tourist numbers on rural economic growth, with acute market acumen. They selected the distinctive ethnic minority folk performance with strong regional characteristics—the Tiaohua performance of the Miao people—as a breakthrough point, and gradually shaped it into an important annual event known as the “Cherry Blossom Festival” in the Wahe area. In recent years, Zhongxin Village has given full play to its location and transportation advantages as “an important node of the Guiyang–Zhijin one-hour economic circle,” systematically and meticulously carrying out industrial transformation and layout work centered around the two core industries of cherry cultivation and rural tourism. Amidst the concerted efforts of diverse actors, Zhongxin Village has effectively integrated its natural resource endowments and profound cultural heritage, skillfully creating a tourism activity system represented by cherry picking, Tiaohua performances, ethnic customs display, and local specialty food experiences. Additionally, it has transformed local characteristic agricultural products and handicrafts into market-competitive commodities, continuously deepening the development of local specialty products. This has not only promoted the optimal allocation of rural spatial resources and the comprehensive improvement of their economic value but has also provided strong support for the development of rural spatial commodification.

4.4. Triadic Dialectics: The Characteristic of Rural Spatial Commodification in Zhongxin Villages

The phased evolution of spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village is fundamentally a consequence of the synergistic impetus provided by both endogenous and exogenous resources. Based on Lefebvre’s triadic dialectical framework for spatial production onto specific rural spatial scenarios, rural spatial commodification triggers profound changes in subject behaviors, social relations, and spatial practices, thereby generating significant shifts across the tripartite dimensions of perceived, conceived, and lived space. Within the coupled development of cherry cultivation and rural tourism, multiple actors, including local governments, grassroots elites, villagers, petty vendors, and tourists, endeavor to strike a balance between the “authenticity” and “commodification” of rural space through a series of differentiated action strategies [

38]. This collective effort aims to achieve sustainable rural spatial commodification.

First, within the perceived space dimension, efforts are made to advance productive preservation and functional superposition. Multiple actors proactively implement a strategy of “conservation-oriented development coupled with moderate adaptation.” On the one hand, they carry out the authentic protection of rural spatial patterns, residential styles, agricultural landscapes, and transportation systems that carry local characteristics. On the other hand, they undertake moderate standardization of cherry plantations to create a rural complex that can be visited and experienced, enhancing the accessibility of tourism activities and promoting the functional superposition of rural natural pastoral scenery and urban leisure experiences. Second, within the conceived space dimension, emphasis is placed on cultural symbol creation and institutional planning. By deeply excavating intangible cultural heritage, such as local festivals and folk crafts, annual events like the Cherry Blossom Festival and the Cherry Picking Festival have been created. These initiatives effectively transform local cultural characteristics into cultural symbols that can be readily consumed and appreciated. Meanwhile, the area’s characteristic landscapes have been comprehensively planned and developed, ensuring that agricultural activities and tourism facilities meet the demands of rural tourism. Third, within the lived space dimension, actor interaction and local identity are strengthened. Through continuous interactions such as daily farming work, participation in tourism services, and consultation on rural affairs, villagers have further strengthened their emotional identification with the local area. During this process, the coordinated evolution of tripartite spaces has not only avoided the authenticity erosion caused by single commodification but has also realized the dialectical unity between the protection of original rural landscapes and the production of modern consumption spaces through the creative transformation of spatial functions, thus constructing a rural commodification promotion path that integrates local characteristics and market adaptability.

5. Discussion

Amidst the intertwined contexts of the Rural Revitalization Strategy, New-Type Urbanization, and Western Development Strategy, rural spatial commodification in the mountainous villages of southwest China has emerged as a critical propellant of rural transformation. This study selected Zhongxin Village as a case study and innovatively constructed an analytical framework integrating the space production theory and multi-actor collaboration. Based on an in-depth description of the coupling process between cherry cultivation industrialization and rural tourism development, combined with multidimensional qualitative interviews involving local governments, villagers, petty dealers, and tourists, this study systematically elucidated the phased evolution characteristics of rural space commodification in the southwestern mountainous region. The main findings of this study are summarized as follows: (1) Rural spatial commodification constitutes a continuously evolving complex process. Through a series of interactive practices, multiple actors collectively drive the transformation of rural space from a traditional production-oriented model toward a modern, multifunctional rural landscape integrating production, livelihood, and ecological functions. (2) Constrained by historical, geographical, social, and economic factors, rural spatial commodification in southwestern mountainous villages faces structural dilemmas: Singular development pathways hinder diversification, fragmented coordination among stakeholders reflects a lack of integrated collaborative mechanisms, and multidimensional support remains critically deficient. (3) To address the structural dilemma of rural spatial commodification, Zhongxin Village strategically identified and developed distinctive rural industries aligned with its localized resources. Concurrently, it leveraged information and communication technologies (ICTs) to significantly enhance market accessibility for locally characteristic products and strengthen the spatial competitiveness of the rural economy. (4) To counteract the erosion of rural authenticity caused by the influx of urban tourists bringing advanced development concepts and consumption demands, Zhongxin Village has implemented practical measures across three dimensions: perceived space, conceived space, and lived space. This approach offers feasible solutions for mountainous villages in southwest China to resist the permeation of urban consumerism.

5.1. Key Driving Factors of Rural Spatial Commodification

The process of spatial commodification in Zhongxin Villages constitutes a systematic project characterized by complexity, dynamism, and continuous evolution. During the transformation process, Zhongxin Village has undergone a shift from an impoverished and underdeveloped mountainous village to an attractive rural tourism destination. This process not only involved synergistic interactions and collaborative mechanisms among heterogeneous actors in rural spatial commodification but also encompassed optimized integration and efficient utilization of rural spatial resources, thereby constituting a critical foundation for the comprehensive revitalization of mountainous villages.

Its development model is constituted through the multidimensional composite characteristics featuring “local government leadership, grassroots elite innovation, villagers’ deep participation, market force penetration, and market force infiltration,” as shown in

Figure 5. (I) Planning guidance: dominated by local government. Relying on local natural scenery, agricultural landscapes, rustic charm, ethnic cultures, and other resource advantages, they have vigorously promoted the construction of landscapes and the layout of recreational tourism projects by driving progress in pivotal domains such as industrial structure optimization, infrastructure improvement [

39], public service level enhancement [

40], and ecological environment protection, which have furnished substantial impetus for rural spatial commodification. (II) Innovation-driven: exploration by grassroots elites. Grassroots elites have demonstrated a significant mobilization and exemplary effect within the rural acquaintance society [

26]. They possess keen market acumen and accurately pinpoint the strategic orientation of local governments in promoting development [

41]. Through a series of innovative explorations and practices that align with the existing practical circumstances, such as cognitive embedding, value chain enhancement, and collective mobilization [

42], they have effectively propelled the process of rural spatial commodification. (III) Actor absorption: deep participation of villagers. As the principal force within rural society [

43], ordinary villagers are deeply embedded in the transformation and development process of rural characteristic industries through the social relationship network constructed by blood-related kinship and geo-neighborhood relations [

44]. Propelled by the combined forces of local government policy guidance, the demonstrative mobilization of grassroots elites, and the tourist consumption demands, villagers reshape the value of rural spaces and simultaneously inject endogenous impetus into rural spatial commodification. (IV) Value reshaping: penetration of market forces. Petty dealers and tourists, representing significant market forces, have comprehensively reshaped the economic order within rural space through market-oriented transmission and consumer demand-driven mechanisms, fostering a more market-integrated and commercially viable rural environment, thereby steadily propelling rural spatial commodification

The practice of spatial commodification in Zhongxin village demonstrates a distinct pattern characterized by “multi-actor collaboration—resource integration.” The transformation and development of characteristic industries drive the convergence of elements such as petty dealers, tourists, capital, information, and technology within the rural space. Multiple actors strategically coalesce around place-based industrial transitions, deploying comparative advantages through trans-local collaboration networks [

45]. They systematically mobilize endogenous and exogenous resources, generating synergistic value chains that fuse localized knowledge systems with strategic foresight frameworks [

42], providing robust intellectual support and a clear visionary roadmap for rural spatial commodification [

41]. In essence, this process represents the productive reconfiguration of rural space in the interaction between multiple actors and local practices [

46]. This, in turn, continually reinforces the exchange value attributes of rural space and facilitates its commodification from traditional production-oriented space to modern consumer-oriented space.

5.2. Structural Dilemmas of Rural Spatial Commodification

Based on diachronic field investigations, the authors observed that, compared to rural areas in developed regions, the process of spatial commodification in the mountainous region of southwest China exhibits a remarkable phenomenon of “development gradient lag,” which is specifically manifested as structural dilemmas derived from the following dimensions.

First, rural spatial commodification relies heavily on the development of characteristic industries. Driven by the rural revitalization strategy and the urban–rural integration development policy, suburban villages in developed regions have fostered diverse industrial models, such as integrated theme-based tourism [

47,

48], smart agriculture, landscape agriculture, health and wellness resorts, boutique homestays [

32,

33], platform economy [

49], and folk cultural heritage preservation [

16,

50]. These developments have effectively facilitated the transformation of rural spatial value from production-oriented carriers to consumer commodities. As a representative case, Zhongxin Village exemplifies the developmental challenges confronting mountainous villagers in southwestern China, constrained by topographical fragmentation, poor transportation accessibility, workforce deficits, inadequate infrastructure, and weak marketization capabilities. Consequently, replicating the multifarious development trajectories of developed regions proves to be an arduous task for them.

Second, fragmented collaboration among multiple rural actors has engendered systemic development delays. The process of rural spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village was initiated in 1993; after years of development, the overall progress has been relatively slow, with each development stage enduring for a relatively long period of time. A systematic analysis identified the primary causation of the fragmented collaboration patterns among multiple actors across all stages. The absence of robust collaborative mechanisms and synergistic integration has substantially extended the spatial commodification timeline, consequently constraining the transformation efficiency of rural spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village.

Third, significant shortcomings across multidimensional rural elements constrain radiation and driving effects. In the mountainous region of southwest China, distinctly characterized by complex geomorphology and acute remoteness, the rural spatial commodification patterns reveal a consistent dependence on the development of characteristic industries. During the development process, the region’s multidimensional resource collection, including its geographical location, natural conditions, ecological environment, and human resources, is comprehensively considered [

51].

These structural dilemmas generate sequential implementation bottlenecks and impede the trajectory of rural spatial commodification. Embarking on a new journey of comprehensively building a modern socialist country, the country has incorporated the deepening of the Western Development Strategy into the national major strategic framework and the regional coordinated development layout. This strategy deems the development of characteristic industries as the core approach to targeted poverty alleviation and rural revitalization in the mountainous region of southwest China [

52]. Within this framework, Zhongxin Village is positioned as a model of agricultural specialization-driven spatial commodification, utilizing its signature cherry cultivation as the principal medium for spatial value conversion.

5.3. Viable Strategies of Rural Spatial Commodification

In contrast to the accelerated rural spatial commodification observed in developed regions, the villages in the mountainous region of southwest China encounter multifaceted development challenges characterized by “accumulative weakness” [

53]. This condition encompasses critical deficits in human capital, socioeconomic shrinkage, ecological vulnerability, infrastructure deficiencies, underdeveloped industrial bases, and constrained market integration. These interconnected challenges generate a self-reinforcing cycle that results in a single industrial path, temporal development lag, and weak demonstration effects. On the one hand, through systematic assessment of regional assets and contextual realities, the villagers implement step-by-step strategies to cultivate mutually reinforcing interest-alignment frameworks among actors [

54], thereby providing sustained intellectual support and innovative impetus for rural spatial commodification. Capitalizing on the village’s inherent geographical advantages and landscape assets, the integration of agriculture and tourism with a relatively low development threshold is prudentially selected as its development entry point [

47]. Through optimized resource distribution, this approach has systematically coordinated the growth of signature cherry cultivation with tourism development, thereby establishing a sustainable framework for progressive rural spatial commodification.

On the other hand, to effectively overcome the spatial isolation and market barriers caused by geographical environment in the mountainous region of southwest China [

55], vigorously developing information and communication technologies (ICTs) and e-commerce activities has emerged as a critical pathway to enhance the resilience of rural characteristic industry cooperation [

56]. Recent years have witnessed a profound digital integration in the mountainous region of southwest China, driven by two concurrent developments: the steady maturation of digital infrastructure and the exponential growth of platform-based economies [

57]. This digital transformation has unlocked new pathways for these rural villages to showcase their unique offerings and engage with broader markets. Through field studies and longitudinal case tracking of Zhongxin Village, the authors’ research revealed that as rural spatial commodification intensifies, villagers in central and surrounding villages exhibited increasingly open and inclusive attitudes. This shift from passive acceptance to active participation motivated their participation in spatial commodification practices. Leveraging digital tools such as new media dissemination and live-streaming platforms, they actively reconstructed local product value through symbolic branding, thus diversifying avenues for place-based economic opportunity generation. This digital technology-based improvement in market accessibility serves as strategic infrastructure for promoting the development of rural characteristic industries, playing an irreplaceable role in bridging the spatial commodification gap with developed regions.

Overall, the process of rural space commodification in the southwestern mountainous region confronts a multitude of challenges, requiring a series of targeted measures. First, within the perceived space, prioritize infrastructure amelioration. Focus on optimizing rural infrastructure, such as water supply, power grids, roads, and sewage treatment, to enhance their livability and attractiveness. Develop tourism-supporting facilities, including sightseeing paths, parking lots, and agricultural experience zones, providing tourists with convenient and comfortable experiences. Enhance the signal strength and stability of communication networks; leverage emerging forms such as e-commerce, live streaming, and VR rural tourism; break through geographical barriers; and significantly improve the market competitiveness of rural agricultural products and spatial landscapes. Second, within the conceived space, establish an institutional framework. Formulate scientific and rational supportive policies and development plans to guide the prioritization of funds and resources toward key sectors, including infrastructure construction, ecological protection, industrial development, and information and communication technology. Additionally, implement a branding strategy to create agricultural and tourism brands with strong recognizability and influence. Third, within the lived space, strengthen social identification. Establish a collaborative platform that extensively engages multiple actors, including the government, villagers, social organizations, and enterprises, clarifies the responsibilities and rights of each party, and forms a collaborative and progressive working mechanism. Attract university graduates, returning entrepreneurs, and technical professionals to contribute to rural spatial commodification, providing technical expertise and intellectual capital for rural development. By implementing the triadic spatial collaborative governance strategy outlined above, the bottlenecks that have constrained the process of rural spatial commodification in the southwestern mountainous region can be effectively mitigated. It establishes a distinctive and sustainable paradigm for rural spatial commodification, thereby providing a robust foundation for the steady advancement of rural revitalization strategies in the southwest mountainous region.

5.4. Avoiding Infiltration of Urban Concepts and Sustaining Rural Authenticity

Since the coupling development paradigm of cherry industrialization and rural tourism, the influx of tourists carrying advanced concepts and consumer culture has led to the risk of gradual erosion of rural authenticity. Building on this context, Zhongxin Village had pioneered the three-dimensional collaborative intervention of rural perceived space, conceived space, and lived space, offering a systematic framework to reconcile external influences with indigenous cultural preservation. This approach aimed to facilitate the creative transformation of rural authenticity. Within the perceived space, Zhongxin Village preserved the traditional terraced landscape and shaped a rural visual symbol with a unified cherry landscape based on it. Simultaneously, it promoted the unified planning and construction of infrastructure such as picking trails and trading centers to enhance the overall image of the village [

58]. Within the conceived space, the village actively delved into the unique cultural heritage of local ethnic minorities and leveraged cultural empowerment to elevate rural tourism. They successfully created the featured “Cherry Blossom Festival” with local brand characteristics, thereby significantly enhancing the village’s reputation and influence [

59]. Within the lived space, the village implemented training programs and exchange activities to cultivate villagers’ local knowledge systems, strengthening their emotional bonds and social cohesion. Throughout exploratory practice, along with the refinement of industrial structure, the upgrading of industrial value chains, and the promotion of in-depth industrial integration, the demand for funds has shown a dynamic growth trend. Digital inclusive finance provides financial support for the construction of rural authenticity [

60].

The three-dimensional practice construction maintained the continuity of the rural spatial physical form, the creative transfer of cultural symbols, and the activation of social relationship networks. These shaped a diverse range of pathways for maintaining authenticity within the process of spatial commodification. To avoid the hindrance of rural spatial commodification caused by the shortage of funds, digital inclusive finance, with its technological empowerment advantages, has become a key catalyst, providing flexible, convenient, and precise financial services for the high-quality development of rural characteristic industries, thereby facilitating comprehensive rural revitalization [

61,

62]. Throughout the historical practice of Zhongxin Village, digital inclusive finance has served as a critical nexus bridging the spatial triad structure and the preservation of authenticity. It propels the synergistic regeneration of cultural value and economic efficiency amid rural spatial commodification, forging a new development paradigm that integrates historical continuity with modern adaptability.

Based on the above empirical research on rural spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village, it can be concluded that the spatial commodification of mountainous villages in southwest China follows an evolutionary principle of “gradual accumulation.” Fundamentally, this process is centered on the collective actions of local actors, systematically integrating and optimizing both endogenous and exogenous resources of the village. It seamlessly embeds rural tourism within the development framework that capitalizes on the rural unique characteristic industry, fostering an organic synthesis between place-based characteristic industrial development and tourism infrastructure enhancement. Looking across China and even the world, numerous villages situated in mountainous environments, owing to similar resource endowments, geographical locations, economic foundations, ecological conditions, and landscape cultures, may face homogenized opportunities and challenges amid rural spatial commodification. Through an in-depth analysis of the spatial commodification in Zhongxin Village, this study demonstrates how multiple actors leverage landscape reconfiguration, cultural valorization, and resource integration to sustain rural agrarian foundations while augmenting spatial value via tourism [

63]. This has forged a differentiated pathway for the coupled development of agricultural production and rural tourism, providing substantive support for rural revitalization under diverse socioeconomic contexts. The theoretical significance lies in transcending the geographical limitations of traditional rural development research and constructing an analytical framework with universal explanatory power. The practical significance lies in providing innovative and actionable solutions for mountain villages, advancing spatial commodification, and exploring sustainable development pathways. Capitalizing on its strategic location, resource-sharing advantages, and transport accessibility, Zhongxin Village has effectively seized development opportunities to prioritize agriculture–tourism integration. This pathway successfully reconciles the structural tension between economic growth and rural conservation, providing a replicable framework of theoretical paradigms and practical references for similar villages worldwide to explore differentiated and sustainable endogenous development trajectories [

64].

indicates a decreasing trend in cultivation scale;

indicates a decreasing trend in cultivation scale;  indicates an increasing trend in cultivation scale;

indicates an increasing trend in cultivation scale;  indicates a stable, unchanging trend in cultivation scale.

indicates a stable, unchanging trend in cultivation scale.

indicates a decreasing trend in cultivation scale;

indicates a decreasing trend in cultivation scale;  indicates an increasing trend in cultivation scale;

indicates an increasing trend in cultivation scale;  indicates a stable, unchanging trend in cultivation scale.

indicates a stable, unchanging trend in cultivation scale.