Plant Community Restoration Efforts in Degraded Blufftop Parkland in Southeastern Minnesota, USA

Abstract

1. Introduction

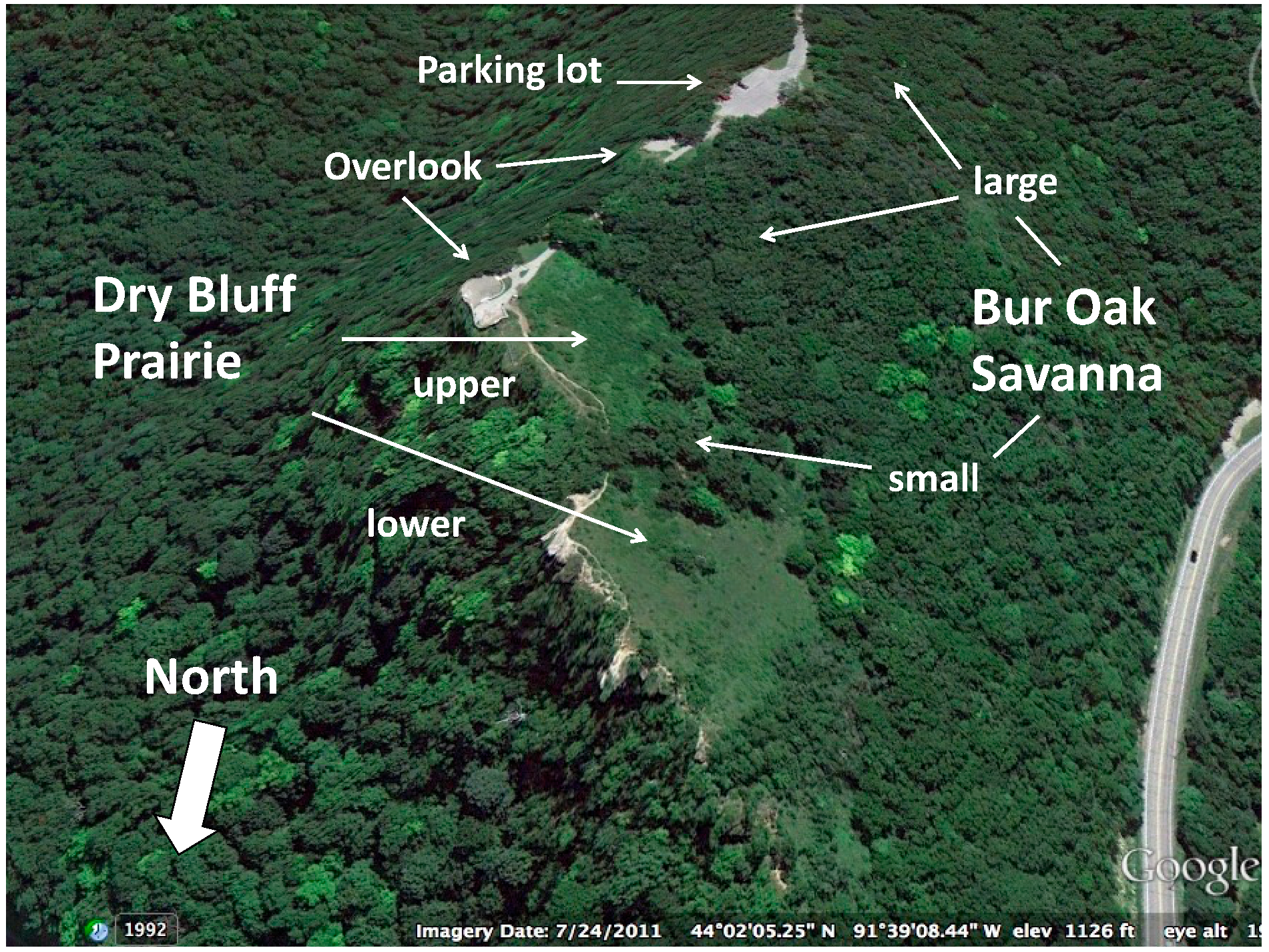

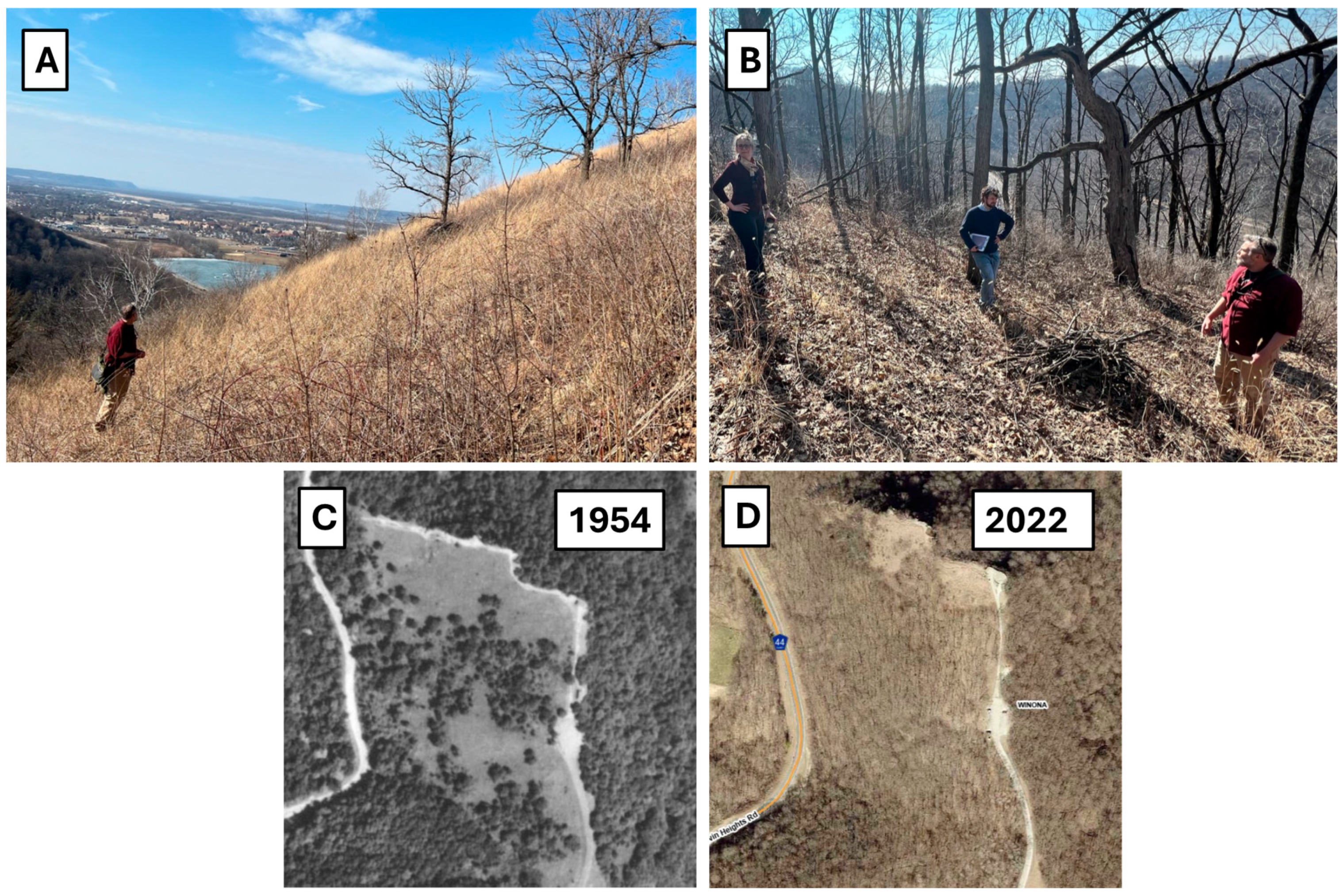

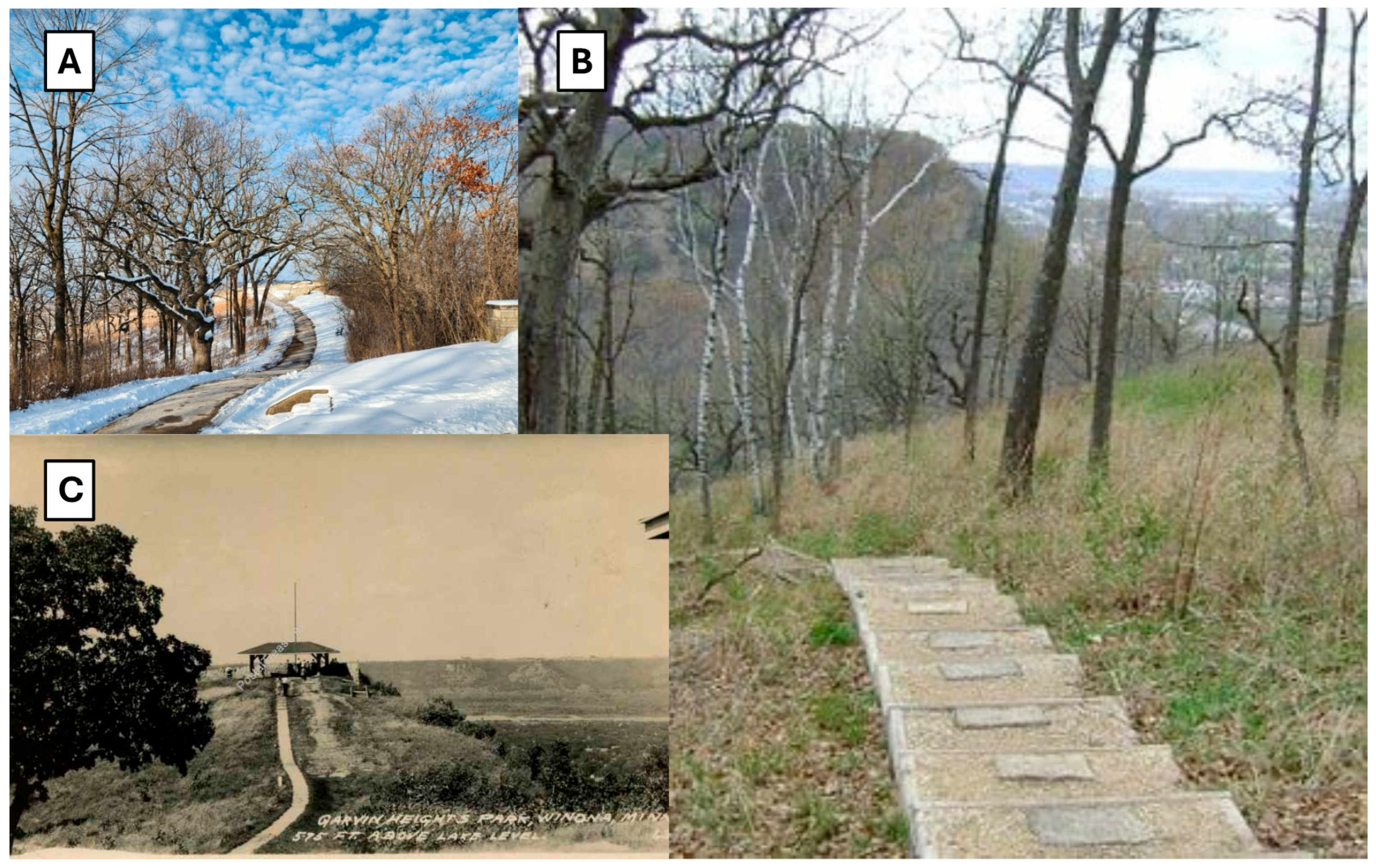

2. Study Area

3. Methods

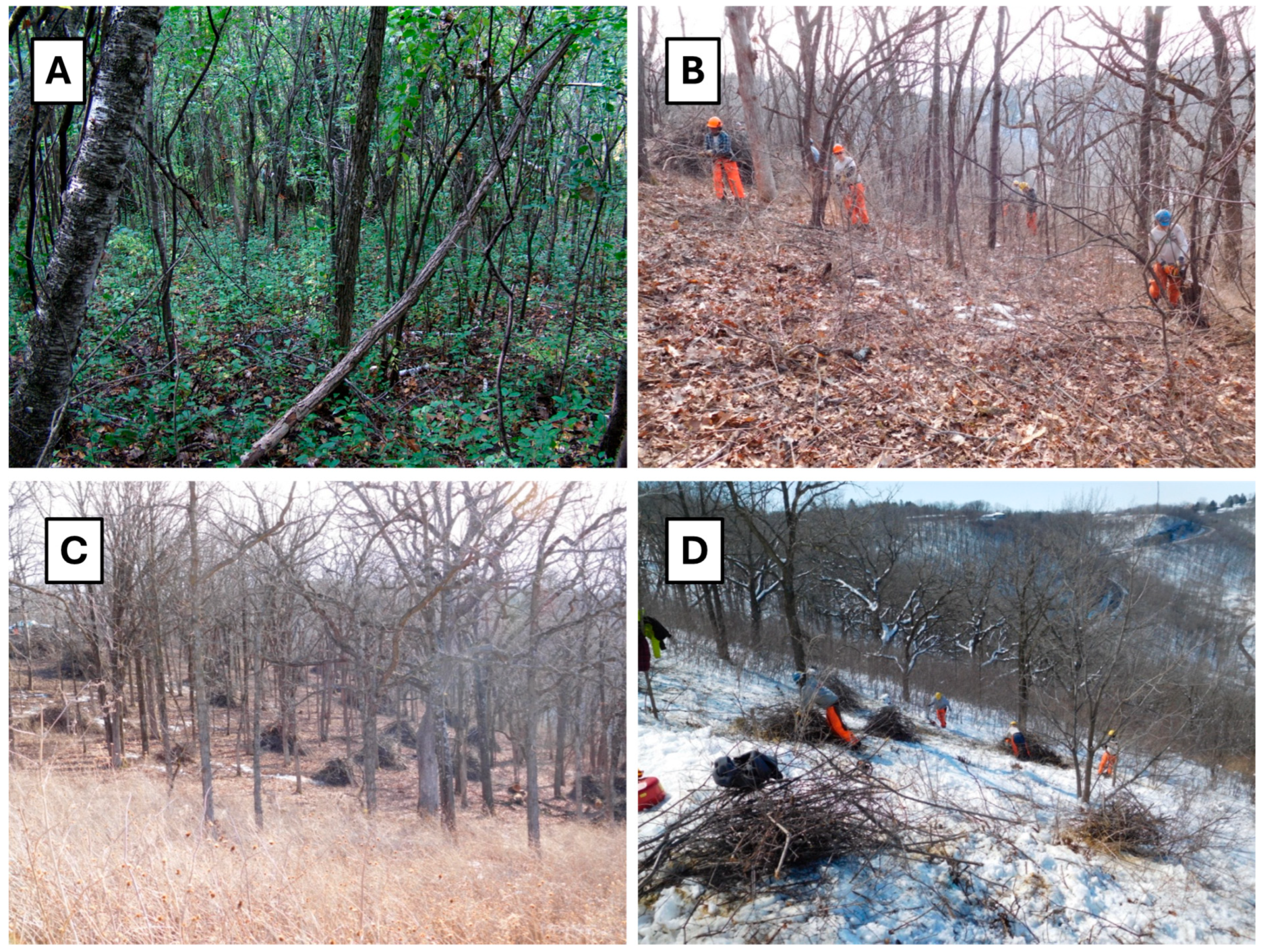

3.1. Woody Invasive Clearing

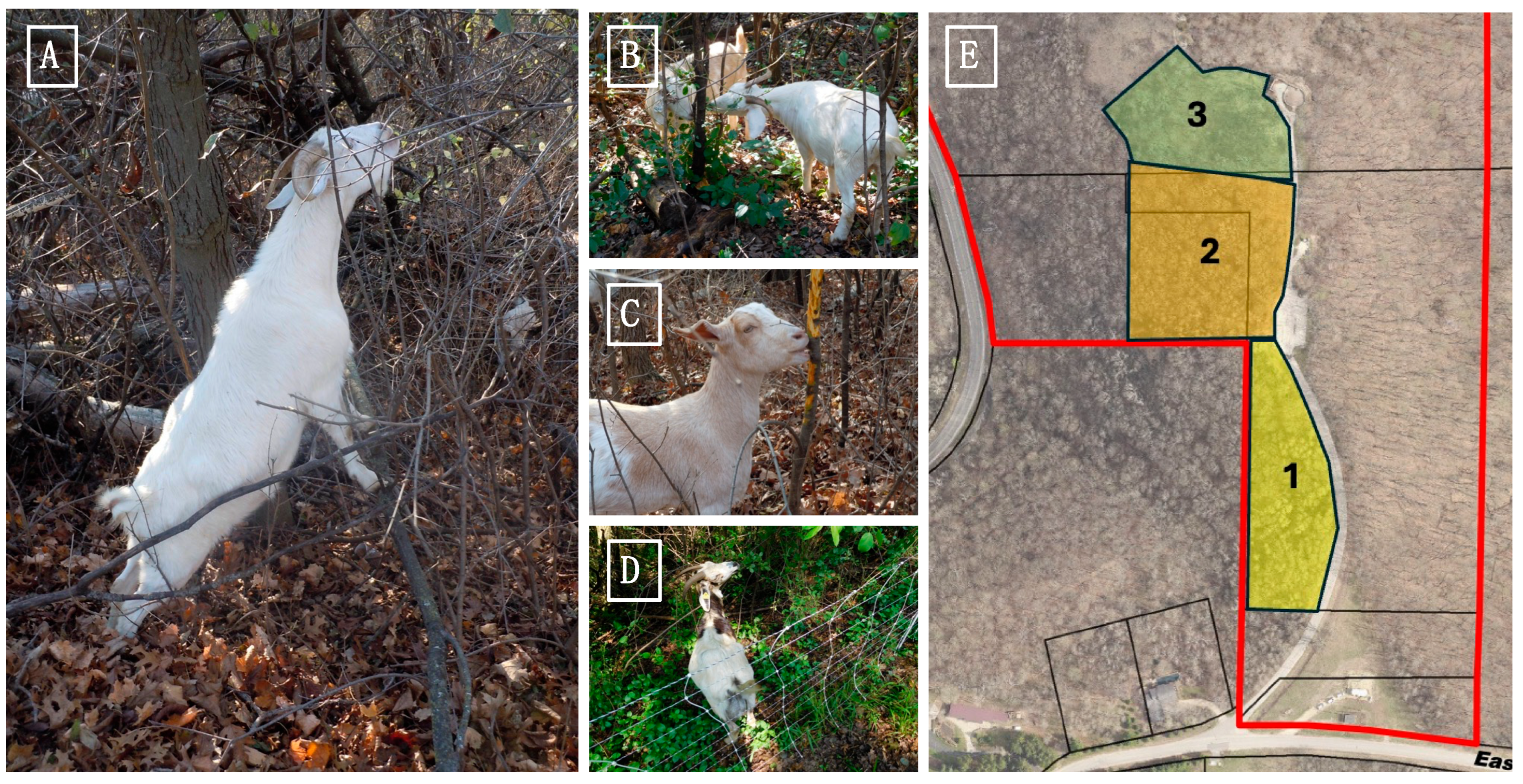

3.2. Goat Browsing

3.3. Native Species Reseeding and Planting

3.4. Prescribed Burns

3.5. Treatment Summary

4. Results

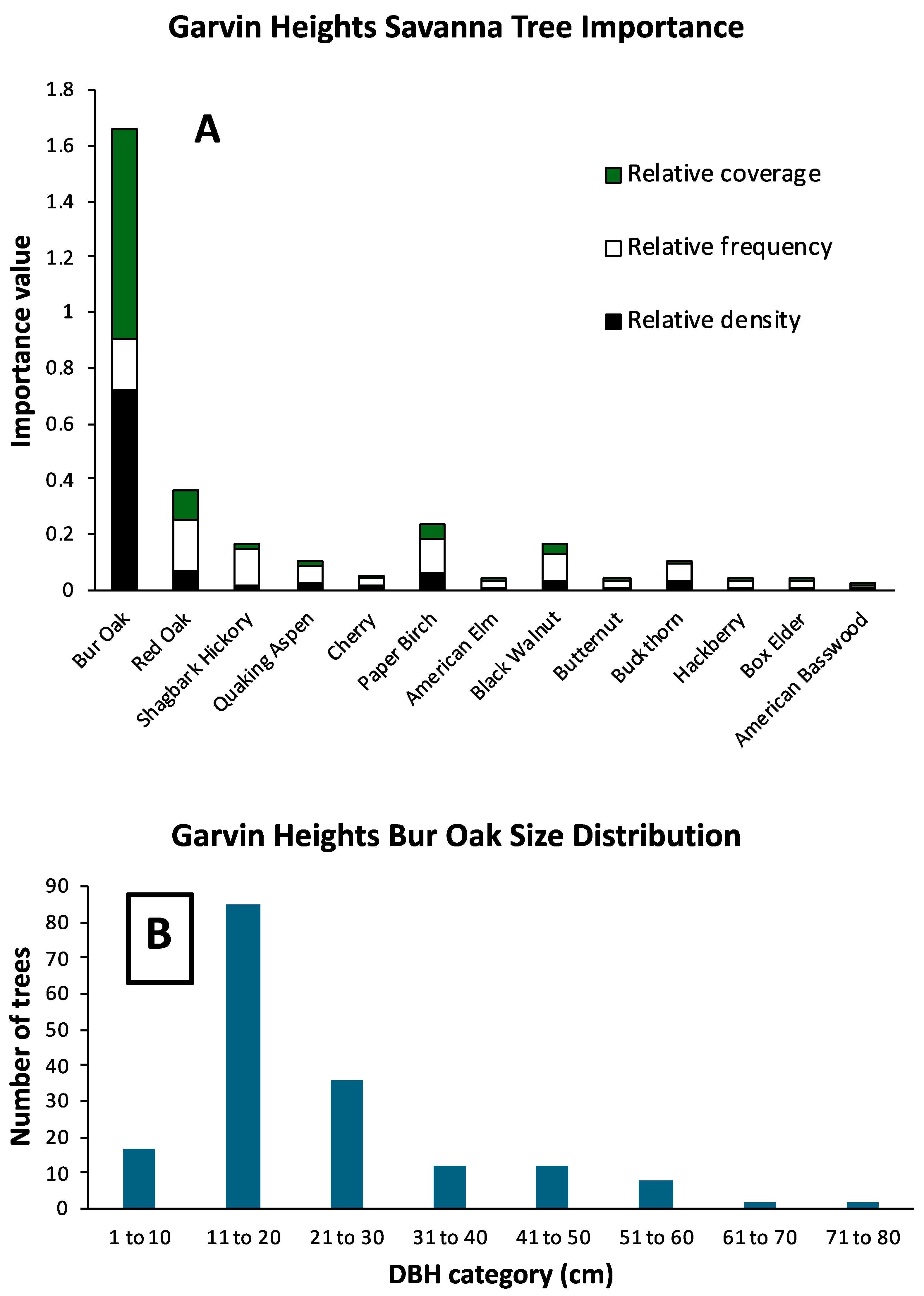

4.1. Woody Invasive Clearing

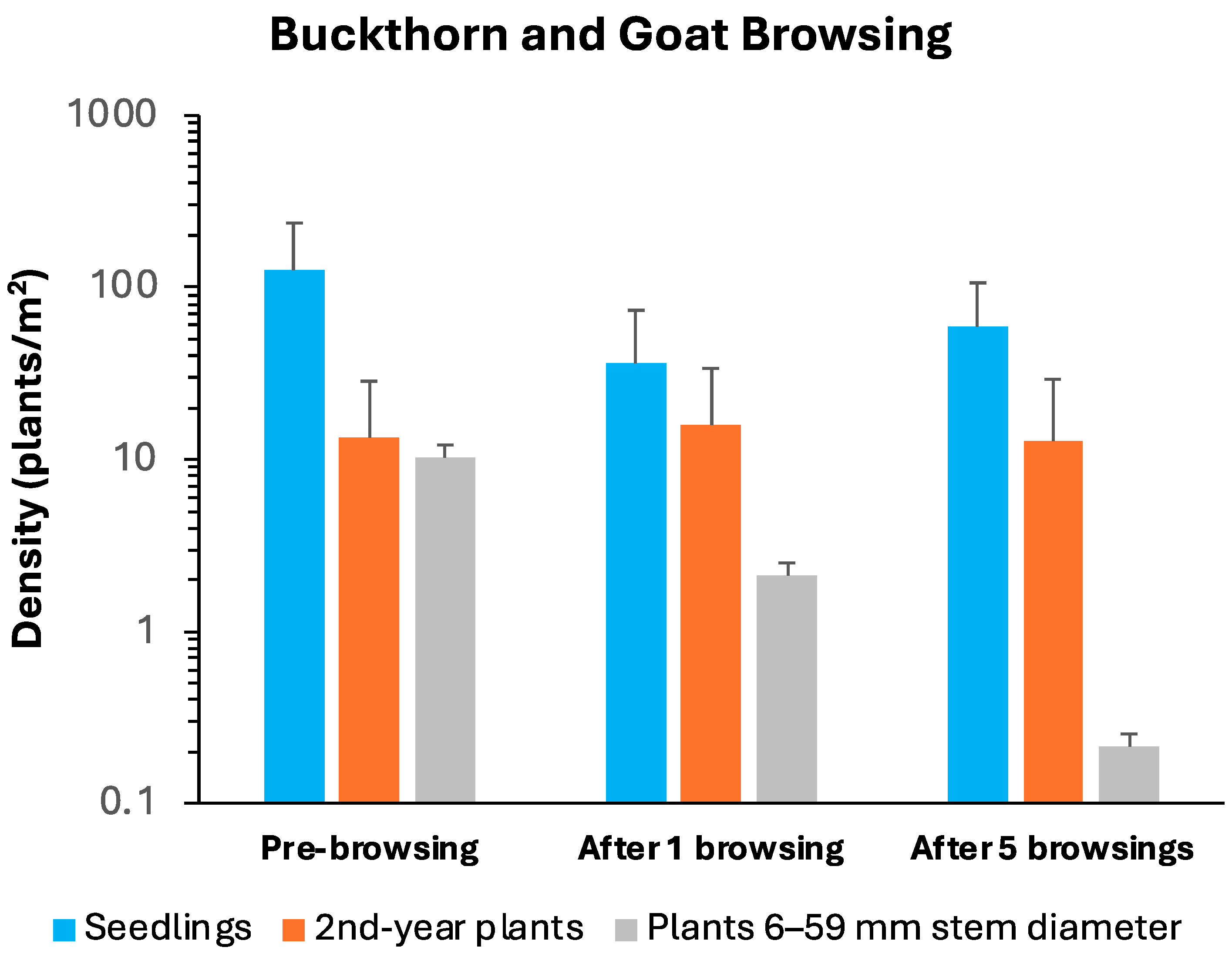

4.2. Goat Browsing

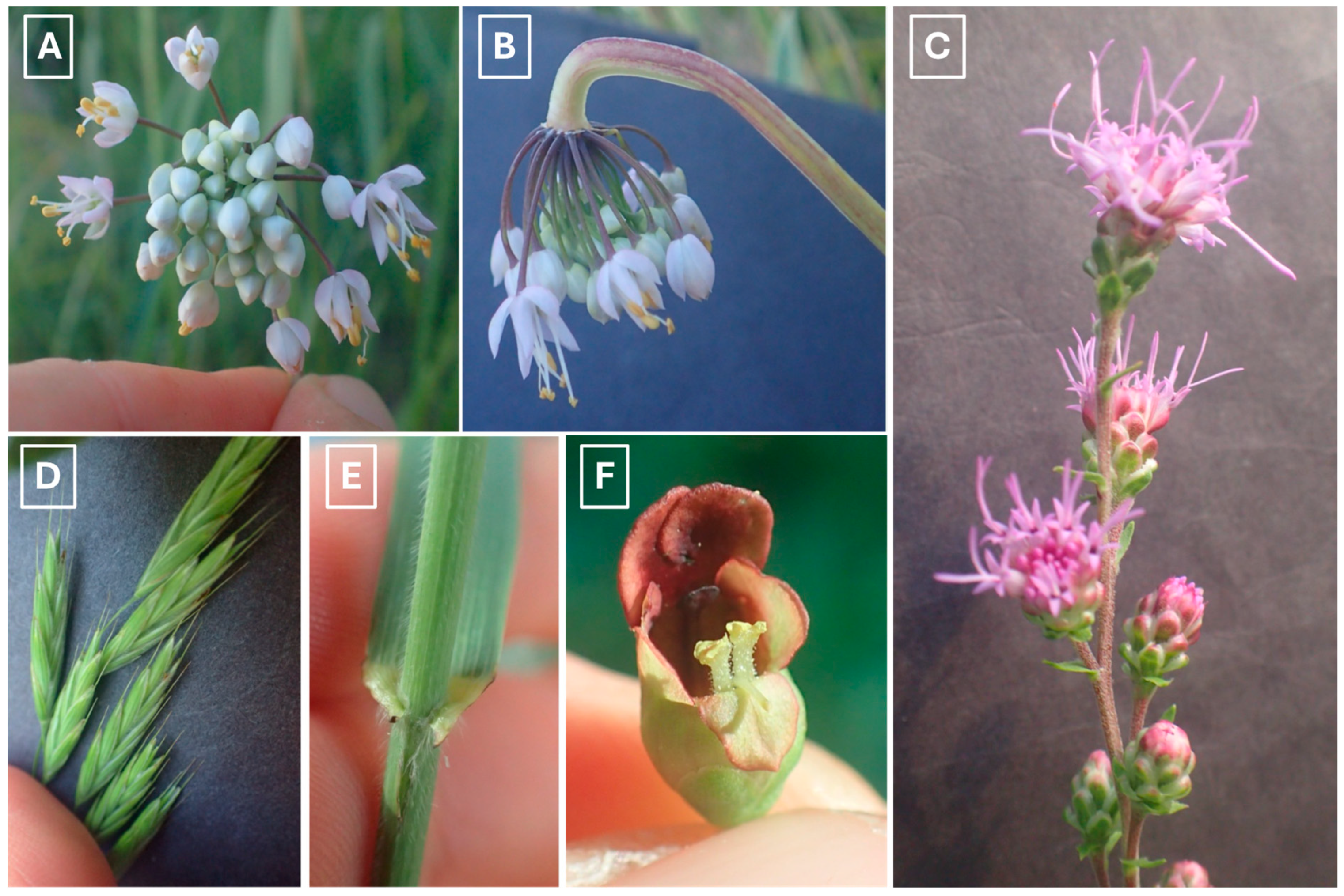

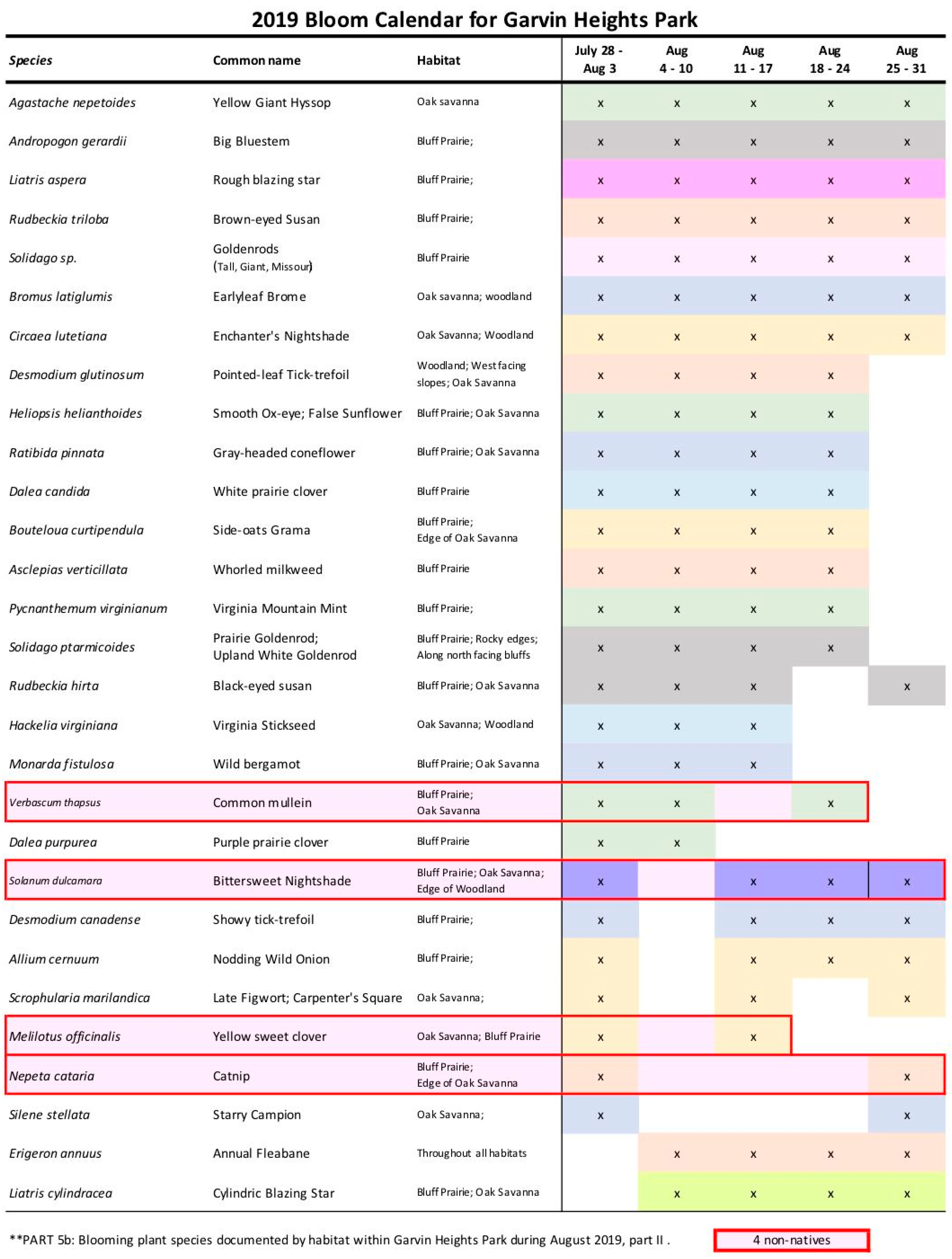

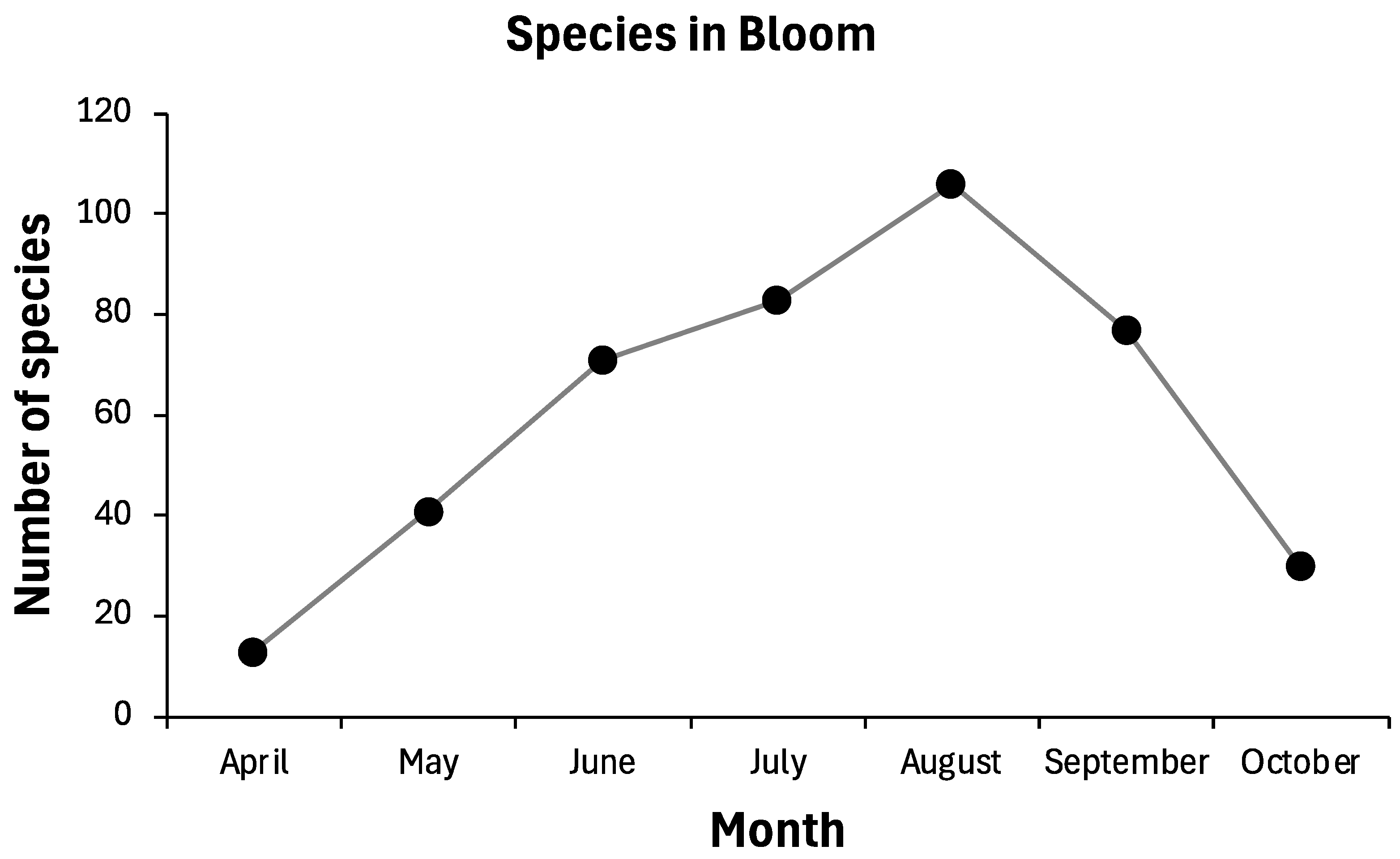

4.3. Herbarium Collection, Re-Seeding, Plug Planting, and Plant Inventories

4.4. Prescribed Burn Versus Weed-Torching

5. Discussion

6. Current and Future Management

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zalba, S.M.; Villamil, C.B. Woody plant invasion in relictual grasslands. Biol. Invasions 2002, 4, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clewell, A.F.; Aronson, J. Ecological Restoration: Principles, Values, and Structure of an Emerging Profession; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wagle, P.; Gowda, P.H. Tallgrass prairie responses to management practices and disturbances: A review. Agronomy 2018, 8, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, N.; Havens, K.; Holloway, J.; Steffen, J.F.; Zeldin, J.; Kramer, A.T. Low passive restoration potential following invasive woody species removal in oak woodlands. Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.R.; Jenkins, M.A.; Jose, S. Invasion biology and control of invasive woody plants in eastern forests. Native Plants J. 2007, 8, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yantes, A.M.; Solberg, K.L.; Montgomery, R.A. Targeted cattle grazing for shrub control in woody-encroached oak savannas. Restor. Ecol. 2025, 33, e14368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, L.K.; Coffey, K.L.; Mitchell, R.J.; Moser, E.B. Ground cover recovery patterns and life-history traits: Implications for restoration obstacles and opportunities in a species-rich savanna. J. Ecol. 2004, 92, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandle, L.; Bufford, J.L.; Schmidt, I.B.; Daehler, C.C. Woody exotic plant invasions and fire: Reciprocal impacts and consequences for native ecosystems. Biol. Invasions 2011, 13, 1815–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.R.; Shaff, S.E. Forest colonization of Puget lowland grasslands at Fort Lewis, Washington. Northwest Sci. 2003, 77, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie, P.W.; Bakker, J.D. The future of restoration and management of prairie-oak ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest. Northwest Sci. 2011, 85, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, E.; Le Stradic, S.; Silveira, F.A.O.; Durigan, G.; Overbeck, G.E.; Fidelis, A.; Fernandes, G.W.; Bond, W.J.; Hermann, J.-M.; Mahy, G.; et al. Resilience and restoration of tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and grassy woodlands. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, R.J.; Castellano, M.J. Strategies for savanna restoration in the southern Great Plains: Effects of fire and herbicides. Restor. Ecol. 2006, 14, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N.; Eufemia, L.; Fleckenstein, M.; Periago, M.E.; Petersen, I.; Timmers, J.F. Grasslands and savannahs in the UN decade on ecosystem restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, A.K.; Briggs, J.M.; Collins, S.L.; Archer, S.R.; Bret-Harte, M.S.; Ewers, B.E.; Peters, D.P.; Young, D.R.; Shaver, G.R.; Pendall, E.; et al. Shrub encroachment in North American grasslands: Shifts in growth from dominance rapidly alters control of ecosystem carbon inputs. Glob. Change Biol. 2008, 14, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, Z.; Nippert, J.B.; Collins, S.L. Woody encroachment decreases diversity across North American grasslands and savannas. Ecology 2012, 93, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, N.; Lehmann, C.E.R.; Murphy, B.P.; Durigan, G. Savanna woody encroachment is widespread across three continents. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abella, S.R.; Menard, K.S.; Schetter, T.A.; Sprow, L.A.; Jaeger, J.F. Rapid and transient changes during 20 years of restoration management in savanna-woodland-prairie habitats threatened by woody plant encroachment. Plant Ecol. 2020, 221, 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Yacht, A.L.; Keyser, P.D.; Barrioz, S.A.; Kwit, C.; Stambaugh, M.C.; Clatterbuck, W.K.; Simon, D.M. Reversing mesophication effects on understory woody vegetation in mid-southern oak forests. Forest Sci. 2019, 65, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, Z.; Nippert, J.B.; Hartman, J.C.; Ocheltree, T.W. Positive feedbacks amplify rates of woody encroachment in mesic tallgrass prairie. Ecosphere 2011, 2, art121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, Z.; Nippert, J.B.; Ocheltree, T.W. Abrupt transition of mesic grassland to shrubland: Evidence for thresholds, alternative attractors, and regime shifts. Ecology 2014, 95, 2633–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetto, S.; Wolf, T.M.; Larkin, D.J. The effectiveness of using targeted grazing for vegetation management: A meta-analysis. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzo, V.A. Extent and status of Midwest oak savanna: Presettlement and 1985. Nat. Areas J. 1986, 6, 6–36. [Google Scholar]

- Abella, S.R.; Jaeger, J.F.; Brewer, L.G. Fifteen years of plant community dynamics during a northwest Ohio oak savanna restoration. Mich. Bot. 2004, 43, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Odanaka, K.; Gibbs, J.; Turley, N.E.; Isaacs, R.; Brudvig, L.A. Canopy thinning, not agricultural history, determines early responses of wild bees to longleaf pine savanna restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, S.C.; Brawn, J.D. Effects of savanna restoration on the foraging ecology of insectivorous songbirds. Condor 2005, 107, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrioz, S.; Keyser, P.; Buckley, D.; Buehler, D.; Harper, C. Vegetation and avian response to oak savanna restoration in the mid-south USA. Am. Midl. Nat. 2013, 169, 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawn, J.D. Effects of restoring oak savannas on bird communities and populations. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johanson, C.J.; Schmid, S.A.; Mundahl, N.D. Fire history and woody encroachment influence saxicolous macrolichen community composition on dolomite outcrops in dry bluff prairies of the Minnesota Driftless Area. Prairie Nat. 2024, 56, 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Panzer, R.; Gnaedinger, K.; Derkovitz, G. The prevalence and status of conservative prairie and sand savanna insects in the Chicago Wilderness Region. Nat. Areas J. 2010, 30, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greipsson, S. Restoration Ecology; Jones and Bartlett Learning: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fill, J.M.; Platt, W.J.; Welch, S.M.; Waldron, J.L.; Mousseau, T.A. Updating models for restoration and management of fiery ecosystems. Forest. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 356, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, D.M.; Jordan, N.R.; Svenson, E.L. Weed control as a rationale for restoration: The example of tallgrass prairie. Conserv. Ecol. 2003, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, D.M.; Jordan, N.R.; Svenson, E.L. Effects of prairie restoration on weed invasions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 107, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, C.C.; Stanley, A.; Kaye, T.N.; Dunwiddie, P.W.; Williams, J.L. Long-term effects of prairie restoration on plant community structure and native population dynamics. Restor. Ecol. 2017, 25, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.D.; Pärtel, M. Extirpation or coexistence? Management of a persistent introduced grass in a prairie restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2003, 11, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundel, R.; Pavlovic, N.B. Using conservation value to assess land restoration and management alternatives across a degraded oak savanna landscape. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008, 45, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Yacht, A.L.; Barrioz, S.A.; Keyser, P.D.; Harper, C.A.; Buckley, D.S.; Buehler, D.A.; Applegate, R.D. Vegetation response to canopy disturbance and season of burn during oak woodland and savanna restoration in Tennessee. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2017, 390, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, A.G.; Alves, M.; Sampaio, A.B.; Schmidt, I.B.; Vieira, D.L.M. Effects of initial functional-group composition on assembly trajectory in savanna restoration. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2019, 22, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhecker, A.; Ferreira, M.C.; Rodrigues, S.B.; Sampaio, A.B.; Schmidt, I.B.; Ribero, J.F.; Ogata, R.S.; Rodrigues, M.I.; Solva-Coelho, A.C.; Abreu, I.S.; et al. Ten years of direct seeding restoration in the Brazilian savanna: Lessons learned and the way forward. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syktus, J.I.; McAlpine, C.A. More than carbon sequestration: Biophysical climate benefits of restored savanna woodlands. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudvig, L.A.; Asbjornsen, H. Patterns of oak regeneration in a Midwestern savanna restoration experiment. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 3019–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, P.; Miao, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Gao, Q.; Wang, K.; Wang, K. The key to temperate savanna restoration is to increase plant species richness reasonably. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1112779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L. Disturbance frequency and community stability in native tallgrass prairie. Am. Nat. 2000, 155, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, G.R. Ecology and Management of North American Savannas; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch, F.; Weber, G.E.; Grimm, V. Ecological buffering mechanisms in savannas: A unifying theory of long-term tree-grass coexistence. Plant Ecol. 2000, 161, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.K.; Givnish, T.J. Gradients in the composition, structure, and diversity of remnant oak savannas in southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1999, 69, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggen, K. Remnant Prairie: A Closer Look at Iowa’s Rarest Landscape; Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation: Des Moines, IA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.inhf.org/blog/blog/remnant-prairie-a-closer-look-at-iowas-rarest-landscape/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- United States National Park Service. Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve Kansas; United States National Park Service: Strong City, KS, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/tapr/index.htm (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- United States Forest Service. Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie; United States Forest Service: Wilmington, IL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/midewin (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Johnsgard, P.A. A Guide to the Tallgrass Prairies of Eastern Nebraska and Adjacent States; University of Nebraska: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2007.

- Sarwacinski, M.I.; Berg-Binder, M.C. Relationships between plant community species richness, remnant area, and invasive leafy spurge cover in southeastern Minnesota bluff prairie habitats. Bios 2017, 88, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, T.D.; Brock, K.M. Oak savanna restoration: A case study. In Proceedings of the 19th North American Prairie Conference, Madison, WI, USA, 8–12 August 2004; Egan, D., Harrington, J.A., Eds.; University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2006; pp. 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, A.M.; Reich, P.B. The effects of eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) invasion and removal on a dry bluff prairie ecosystem. Biol. Invasions 2010, 12, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Field Guide to the Native Plant Communities of Minnesota: The Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province; Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Ecological Land Classification Program, Minnesota County Biological Survey, and Natural Heritage and Nongame Research Program: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mundahl, N.D.; Walsh, R. Bark-stripping of common buckthorn by goats during managed browsing on bur oak savannas. Biol. Invasions 2022, 24, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsari, B.; Mundahl, N.; Vidrine, M.F.; Pastorek, M. The significance of micro-prairie reconstruction in urban environments. Prairie Nat. 2014, 46, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mundahl, N.; Eaton, E.; Brutt, S.; Peterson, K. Experimental management of common buckthorn on a dry bluff savanna restoration site. In Proceedings of the 22nd North American Prairie Conferences (NAPC 2010), Cedar Falls, IA, USA, 1–5 August 2010; Volume 21, pp. 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, D.W.; Reich, P.B.; Wrage, K.J. Plant functional group responses to fire frequency and tree canopy cover gradients in oak savannas and woodlands. J. Veg. Sci. 2007, 18, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.W.; Reich, P.B. Prescribed fire in oak savanna: Fire frequency effects on stand structure and dynamics. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yantes, A.M.; Reed, S.P.; Yang, A.M.; Montgomery, R.A. Oak savanna vegetation response to layered restoration approaches: Thinning, burning, and grazing. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 537, 120931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, T.J.; Landis, D.A.; Brudvig, L.A. Effects of experimental prescribed fire and tree thinning on oak savanna understory plant communities and ecosystem structure. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 464, 118047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.A.; Kathol, E. Responses of shrub midstory and herbaceous layers to managed grazing and fire in a North American savanna (oak woodland) and prairie landscape. Restor. Ecol. 2009, 17, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service. Web Soil Survey: National Cooperative Soil Survey; USDA-NRCS: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- United States National Weather Service. U.S. Climate Data: Winona, Minnesota; US National Weather Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://usclimatedata.com/climate/winona/minnesota/united-states/usmn0807#google_vignette (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Minnesota Digital Library. Winona County Historical Society; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2025. Available online: https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog?f[contributing_organization_ssi][]=Winona+County+Historical+Society (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Fremling, C.R.; Heins, G.A. A Lake Winona Compendium: Information Concerning the Reclamation of an Urban Winter-Kill Lake at Winona, Minnesota, 2nd ed.; Winona State University: Winona, MN, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Winona Republican-Herald. Extensive Improvement Program on Garvin Heights Being Considered. Winona Republican-Herald, 28 November 1939; Volume 39, p. 3. Available online: https://newspaperarchive.winona.edu/?a=d&d=TWH19391128-01.2.125&srpos=4&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-garvin+heights------ (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Archibold, O.W.; Brooks, D.; Delanoy, L. An investigation of the invasive shrub European buckthorn, Rhamnus cathartica L., near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Can. Field-Nat. 1997, 111, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoy, L.; Archibold, O.W. Efficacy of control measures for European buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica L.) in Saskatchewan. Environ. Manag. 2007, 40, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisikwa, J.; Natukunda, M.I.; Becker, R.L. Effect of method and time of management on European buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica L.) growth and development in Minnesota. J. Sci. Agric. 2020, 4, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.R. The composition of savanna vegetation in Wisconsin. Ecology 1960, 41, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerner, S.E.; Burkepile, D.E.; Fynn, R.W.S.; Burns, C.E.; Eby, S.; Govender, N.; Hagenah, N.; Matchett, K.J.; Thompson, D.I.; Wilcox, K.R.; et al. Plant community response to loss of large herbivores differs between North American and South African savanna grasslands. Ecology 2014, 95, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwig, L.M.; Damschen, E.I.; Rogers, D.A. Sixty years of community change in the prairie-savanna-forest mosaic of Wisconsin. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 8458–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillhouse, H.L.; Zedler, P.H. Native species establishment in tallgrass prairie plantings. Am. Midl. Nat. 2011, 166, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.L.; Bright, J.B.; Drobney, P.; Larson, J.L.; Vacek, S. Persistence of native and exotic plants 10 years after prairie reconstruction. Restor. Ecolo. 2017, 25, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, D.M.; Bidwell, T.G. Viewpoint: The response of central North American prairies to seasonal fire. J. Range Manag. 2001, 54, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, E.E.; Estes, B.L.; Skinner, C.N. Ecological Effects of Prescribed Fire Season: A Literature Review and Synthesis for Managers; United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, General Technical Report PSW-GTR-224; USDA-Forest Service: Albany, CA, USA, 2009; Available online: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jfspsynthesis/4 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Grant, T.A.; Madden, E.M.; Shaffer, T.L.; Dockens, J.S. Effects of prescribed fire on vegetation and passerine birds in northern mixed-grass prairie. J. Wildl. Manag. 2010, 74, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Fish & Wildlife Service. Rusty Patched Bumble Bee; United States Fish & Wildlife Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/species/rusty-patched-bumble-bee-bombus-affinis (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Rare Species Guide: Arnoglossum reniforme (Hook.) H.E. Robins. Great Indian Plantain; Minnesota Department of Natural Resources: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/rsg/profile.html?action=elementDetail&selectedElement=PDASTD7040 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Dietz, T.E.; Marsh, M.K.; Mundahl, N.D. A rapidly expanding population of Great Indian Plantain (Arnoglossum reniforme) in southeastern Minnesota. Prairie Nat. in press.

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Native Plant Community and Habitat Spotlights: Oak Savanna; Minnesota Department of Natural Resources: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/woodlands/spotlights-oak-savanna.html (accessed on 8 February 2025).

| Functional Group | Scientific Name | Common Name |

|---|---|---|

| Forbs | Asclepias tuberosa | Butterfly Weed |

| Aster azureus | Sky Blue Aster | |

| Astragalus canadensis | Canadian Milk Vetch | |

| Baptisia leucantha | White Wild Indigo | |

| Cassia fasciculata | Partridge Pea | |

| Coreopsis palmata | Prairie Coreopsis | |

| Lespedeza capitata | Round-headed Bush Clover | |

| Liatris aspera | Button Blazing Star | |

| Pentalostemum candidum | White Prairie Clover | |

| Pentalostemum purpureum | Purple Prairie Clover | |

| Rudbeckia hirta | Black-eyed Susan | |

| Tradescantia ohiensis | Ohio Spiderwort | |

| Verbena stricta | Hoary Vervain | |

| Grasses | Bouteloua curtipendula | Side-oats Grama |

| Schizachyrium scoparium | Little Bluestem |

| Functional Group | Scientific Name | Common Name | 2004/05 Seeds | 2018/20 Seeds | 2019 Plugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forbs | Agastache nepetoides | Yellow Giant Hyssop | X | X | |

| Agastache scrophurlariaefolia | Purple Giant Hyssop | X | |||

| Anaphalis margaritacea | Pearly Everlasting | X | |||

| Aquilegia canadensis | Canada Columbine | X | X | ||

| Anemone virginiana | Tall Thimbleweed | X | |||

| Arnoglossum reniforme | Great Indian Plantain | X | |||

| Aureolaria grandiflora | Yellow False Foxglove | X | |||

| Aster azureus | Sky Blue Aster | X | |||

| Aster ericoides | Heath Aster | X | |||

| Aster laevis | Smooth Blue Aster | X | |||

| Aster novae-angliae | New England Aster | X | |||

| Aster sagittifolius | Arrow-leaved Aster | X | |||

| Astragalus canadensis | Canadian Milk Vetch | X | |||

| Baptisial leucantha | White Wild Indigo | X | |||

| Baptisia leucophaea | Cream Wild Indigo | X | |||

| Blephilia hirsuta | Hairy Wood-mint | X | X | ||

| Campanula americana | Tall Bellflower | X | |||

| Coreopsis palmata | Prairie Coreopsis | X | |||

| Cryptotaenia canadensis | Honewort | X | |||

| Desmodium illinoense | Illinois Tick Trefoil | X | |||

| Dodecatheon meadia | Midland Shooting Star | X | |||

| Eryngium yuccifolium | Rattlesnake Master | X | |||

| Eupatorium altissimum | Tall Boneset | X | |||

| Eurybia furcata | Forked Aster | X | |||

| Euthamia graminifolia | Grass-leaved Goldenrod | X | |||

| Eutrochium maculatum | Spotted Joe Pye Weed | X | |||

| Eutrochium purpureum | Sweet Joe Pye Weed | X | X | ||

| Gentiana flavida | Cream Gentian | X | |||

| Gentiana quinquefolia | Stiff Gentian | X | |||

| Geranium maculatum | Wild Geranium | X | |||

| Heliopsis helianthoides | Early Sunflower | X | |||

| Hypericum punctatum | Dotted St. John’s Wort | X | |||

| Hypericum pyramidatum | Great St. John’s Wort | X | |||

| Kuhnia eupatorioides | False Boneset | X | |||

| Lespedeza capitata | Round-headed Bush Clover | X | |||

| Lobelia inflata | Indian Tobacco | X | |||

| Lupinus perennis | Wild Lupine | X | |||

| Maianthemum racemosum | Solomon’s Plume | X | X | ||

| Monarda fistulosa | Wild Bergamot | X | |||

| Onosmodium molle | Marbleseed | X | |||

| Osmorhiza claytonii | Sweet Cicely | X | |||

| Pedicularis canadensis | Wood Betony | X | |||

| Penstemon hirsutus | Hairy Beardtongue | X | |||

| Petalostemum candidum | White Prairie Clover | X | |||

| Petalostemum purpureum | Purple Prairie Clover | X | |||

| Persicaria virginiana | Woodland Knotweed | X | |||

| Phlox divaricata | Wild Blue Phlox | X | |||

| Polemonium reptans | Jacob’s Ladder | X | X | ||

| Polygonatum biflorum | Solomon’s Seal | X | X | ||

| Prenanthes alba | Lion’s Foot | X | |||

| Pycanthemum virginianum | Mountain mint | X | |||

| Ratibida pinnata | Yellow Coneflower | X | |||

| Rudbeckia hirta | Black-eyed Susan | X | X | ||

| Rudbeckia subtomentosa | Sweet Black-eyed Susan | X | |||

| Rudbeckia triloba | Brown-eyed Susan | X | X | ||

| Scrophularia lanceolata | Early Figwort | X | X | ||

| Scrophularia marilandica | Late Figwort | X | |||

| Silene stellata | Starry Campion | X | X | ||

| Silphium laciniatum | Compass Plant | X | |||

| Solidago flexicaulis | Zigzag Goldenrod | X | X | ||

| Solidago graminifolia | Grass-leaved Goldenrod | X | |||

| Solidago nemoralis | Old Field Goldenrod | X | |||

| Solidago rigida | Stiff Goldenrod | X | |||

| Solidago speciosa | Showy Goldenrod | X | |||

| Solidago ulmifolia | Elm-leaved Goldenrod | X | |||

| Symphyotrichum prenanthoides | Crooked-stem Aster | X | |||

| Symphyotrichum shortii | Short’s Aster | X | |||

| Taenidia integerrima | Yellow Pimpernel | X | |||

| Tephroisa virginiana | Goat’s Rue | X | |||

| Teucrium canadense | Germander | X | |||

| Thaspium trifoliatum | Meadow Parsnip | X | |||

| Verbena stricta | Hoary Vervain | X | |||

| Veronicastrum virginicum | Culver’s Root | X | |||

| Zizia aurea | Golden Alexanders | X | X | ||

| Grasses | Andropogon gerardii | Big Bluestem | X | ||

| Bouteloua curtipendula | Side-oats Grama | X | |||

| Bromus kalmii | Prairie Brome | X | |||

| Bromus pubescens | Hairy Wood Chess | X | X | ||

| Diarrhena obovata | Beak Grass | X | X | ||

| Elymus canadensis | Canada Wild Rye | X | X | ||

| Elymus hystrix | Bottlebrush Grass | X | X | X | |

| Elymus villosus | Silky Wild Rye | X | |||

| Koeleria macrantha | Prairie Junegrass | X | |||

| Schizachyrium scoparium | Little Bluestem | X | X | ||

| Sorghastrum nutans | Indian Grass | X | |||

| Sporobolus heterolepsis | Northern Dropseed | X | |||

| Sedges | Carex grisea | Wood Gray Sedge | X | ||

| Carex molesta | Field Oval Sedge | X | |||

| Carex sprengelii | Long-beaked Sedge | X | |||

| Shrubs/vines | Amorpha canescens | Lead Plant | X | ||

| Ceanothus americanus | New Jersey Tea | X | |||

| Clematis virginiana | Virgin’s Bower | X | |||

| Rosa blanda | Early Wild Rose | X | X | ||

| Rosa arkansana | Prairie Wild Rose | X |

| Treatment | Upper Prairie | Lower Prairie | Large Savanna | Small Savanna |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear and chemically treat | Yes | In part | In part | Yes |

| Goat browsing | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Seeding and planting | Yes | No | In part | No |

| Prescribed burns | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mundahl, N.D.; Yantes, A.M.; Howard, J. Plant Community Restoration Efforts in Degraded Blufftop Parkland in Southeastern Minnesota, USA. Land 2025, 14, 1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071326

Mundahl ND, Yantes AM, Howard J. Plant Community Restoration Efforts in Degraded Blufftop Parkland in Southeastern Minnesota, USA. Land. 2025; 14(7):1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071326

Chicago/Turabian StyleMundahl, Neal D., Austin M. Yantes, and John Howard. 2025. "Plant Community Restoration Efforts in Degraded Blufftop Parkland in Southeastern Minnesota, USA" Land 14, no. 7: 1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071326

APA StyleMundahl, N. D., Yantes, A. M., & Howard, J. (2025). Plant Community Restoration Efforts in Degraded Blufftop Parkland in Southeastern Minnesota, USA. Land, 14(7), 1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071326