The Policy Effectiveness and Citizen Feedback of Transferable Development Rights (TDR) Program in China: A Case Study of the Chongqing Land Ticket Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. An Overview of the Chongqing Land Ticket Model

2.1. An Adaptation of the TDR Mechanism in China

2.2. A Special Case in China’s TDR Programs

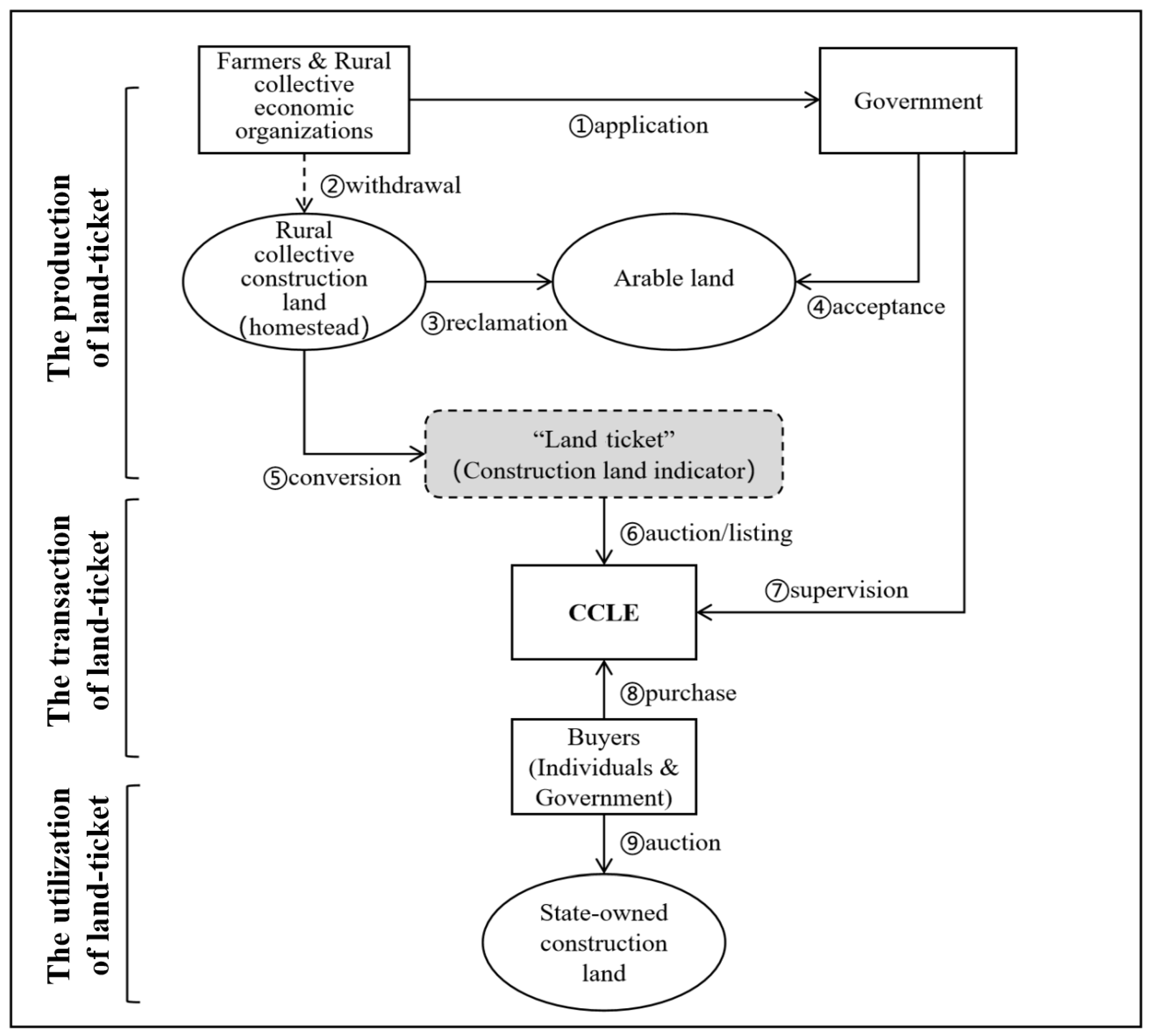

2.3. The Operating Procedure of the Chongqing Land Ticket Model

3. Methods

3.1. Evaluation of Policy Effectiveness

3.1.1. Standards of Measurement

3.1.2. Data Sources and Text Encoding

- The policy document must be officially released by a government department or its subordinate institution and possess legal normative authority;

- The term “land ticket” must be explicitly included in either the title or main text of the policy document;

- The policy document must apply to the entire scope of Chongqing city, rather than being restricted to a specific district or region;

- The policy document must provide detailed content regarding at least one aspect of the production, transaction, or utilization of land tickets, rather than merely referencing the term “land ticket”;

- The content of the policy document must not duplicate that of previously issued policies;

- Policy documents jointly issued by multiple departments may be considered as research samples, provided that at least one of the issuing entities is among the aforementioned departments (e.g., the Chongqing Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources);

- Attachments to policy documents are excluded from consideration as research samples.

3.1.3. Data Analysis

3.2. Evaluation of Citizen Feedback

3.2.1. Data Sources

3.2.2. Research Tools

3.2.3. Data Analysis

- Employ the Jieba word segmentation function (in Python v3.9) to accurately tokenize Chinese policy consulting texts, breaking sentences into discrete words;

- Take the text content of citizen feedback as the original corpus and define the encoding format as UTF-8.

- To prevent the interference of semantically insignificant words during the keyword extraction process, a customized dictionary was developed based on the HIT stopword dictionary (Table 3).10 This dictionary was incorporated into the keyword extraction avoidance rules to ensure that the resulting outcomes are highly pertinent to the research focus (land ticket).

- By employing the “jieba.analyse.extract” function with the parameters “topK = 20” and “withWeight = True”, we aimed to compute the TF-IDF values for all word segmentation results across the entire corpus and extract the top 20 keywords ranked in descending order of their importance.

- Organize the categories according to the meaning of the keywords.

- To achieve keyword visualization and further enhance the intuitive understanding of the text’s theme, a word cloud was generated by using the “wordcloud“ library based on the extracted keywords. Ultimately, the TF-IDF values of the top 50 keywords were divided into five grade intervals by the 20% percentile method, and keywords of different weights were marked in sequence from red to green.

4. Results

4.1. Policy Effectiveness Score and Characteristics of the Chongqing Land Ticket Policies

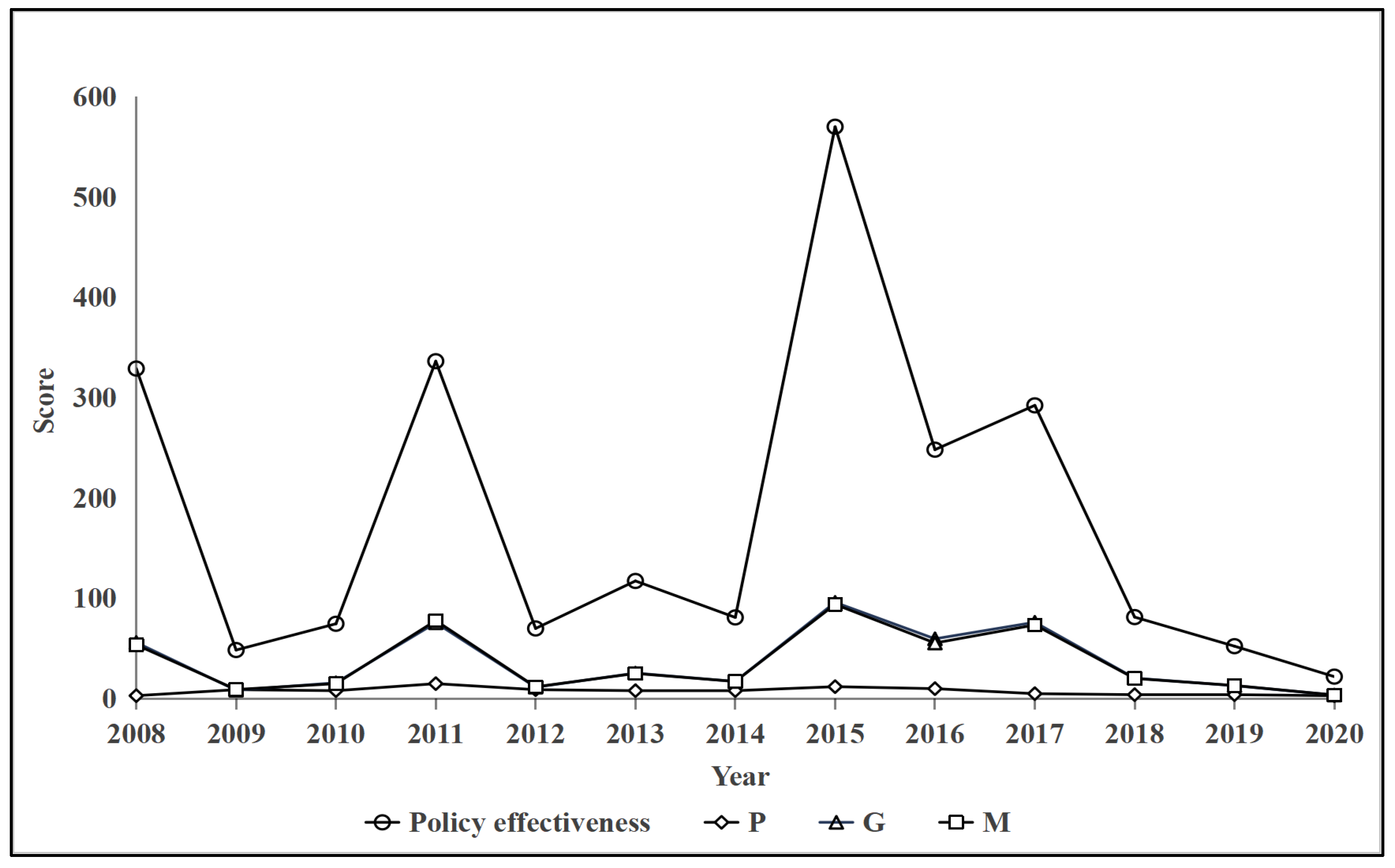

- Table 5 indicates that the policy power (P) scores exhibit relative consistency across the years under consideration. Among the 39 policy texts analyzed, all were issued by the Chongqing Municipal People’s Government and the Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration (currently the Chongqing Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources), except for two policies respectively issued by the State Council (PRC) and the CCLE (Table 5). The policy texts issued by the Chongqing Municipal People’s Government, which is responsible for steering the overall direction of the land ticket model, predominantly take the form of opinions and notices. In contrast, the policy texts issued by the Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration, which oversees the specific implementation of the land ticket model, include notices as well as methods, detailed rules, regulations, and guidelines. Moreover, the two sets of policies differ in their focus. The former offers policy support and guidance for the land ticket model from a macro perspective, addressing rural financial service reform, urban–rural household registration integration, and the supervision of trading venues. In contrast, the latter imposes institutional constraints and provides detailed operational guidance at a micro level, focusing on aspects directly related to the production, transaction, and utilization of land tickets, including transaction procedures, fund management rules, and standardized reclamation processes.

- 2.

- The scores for policy goals (G) and measures (M) in each year are comparable, exhibiting similar changing trends, which can be attributed to the clarity of the content and the comprehensiveness of the support measures. In addition to the two comprehensive policy documents,11 the majority of the remaining texts adhere to the principle of “one document, one matter, one solution”. Specific management measures corresponding to the depth of the content are typically proposed for issues in the production, transaction, and utilization of land ticket. This feature is particularly evident in policies related to reclamation work and the management of land ticket funds.

- 3.

- The peaks of policy effectiveness correspond to the key operational nodes of the land ticket model. The peaks of policy effectiveness are concentrated in the years of 2008, 2011, 2015, 2016, and 2017 (Figure 4), with scores of 329, 336.33, 570, 248.17, and 322.33 respectively. Among them, 2008 and 2015, 2016 can be regarded as the “institutional years” of this model. The promulgation of the Provisional administrative measure of Chongqing Country Land Exchange in 2008 marked the initial establishment of the land ticket model. This document, centered on the platform for land ticket transactions by CCLE, stipulated its institutional functions and management processes, and initially clarified the basic contents such as the objects and rules of land ticket transactions, establishing the basic framework of the model. In 2015, the guiding document for the land ticket model, the Measures of Chongqing Land Ticket Management, was issued. The numerous transaction rules, organizational support, and indicators transferring details during the previous trial period were reorganized, and most of these regulations have not been modified since then. On the other hand, 2011 can be regarded as the “trading years” of the Chongqing land ticket model, being the years with the largest number (52,900 mu) of reclamation program and land ticket transactions since the implementation of the model. The local government updated and improved the policies in a timely manner according to the development needs of the trading market. The fluctuations in policy effectiveness observed in 2016 and 2017 were primarily driven by external policy shocks. Specifically, 2016 marked the first year of China’s 13th Five-Year Plan, during which poverty alleviation was elevated to a national strategic priority, referred to as the “Battle against Poverty.” In response, the central government mandated local governments to adopt measures such as “relocation for poverty alleviation”12 to provide economic support and improved living conditions for farmers in impoverished areas. Under the pressure of centrally assigned poverty alleviation targets, policymakers in Chongqing re-emphasized the land ticket model, recognizing its potential to convert farmers’ land assets into economic income. Consequently, in 2016 and 2017, Chongqing initiated improvements to certain aspects of the land ticket model (e.g., granting priority participation rights to poor farmers), thereby tilting the policy design toward safeguarding farmers’ rights and interests. Notably, these refinements significantly boosted farmers’ enthusiasm for applying for homestead reclamation, culminating in the second-largest transaction surge in the history of the land ticket model in 2017 (48,032 mu).

- 4.

- The annual fluctuations in policy effectiveness are notably significant. Following the peak of policy effectiveness, there is often a subsequent trough. In the year succeeding the five years with the highest policy effectiveness, the average difference in policy effectiveness compared to the previous year was −211 points. This occurs because after a large number of policy documents are issued within a single year, it requires time for grassroots levels to comprehend the implementation goals and execute the established plans. Furthermore, the policy goals associated with the Chongqing land ticket model are relatively limited and concentrated, making it challenging for subsequent policies to establish new regulations for the same policy goals or modify the preceding policies.

- 5.

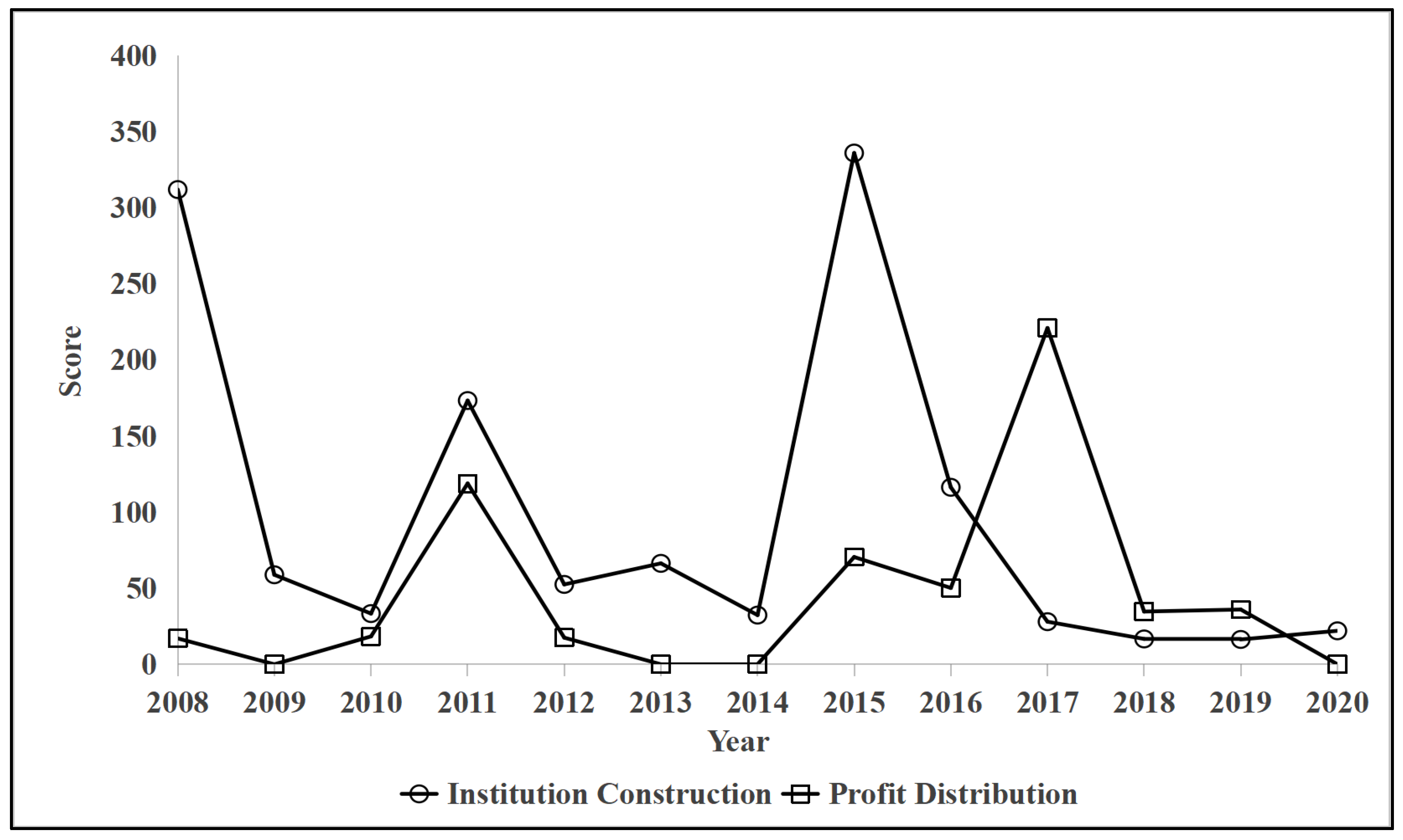

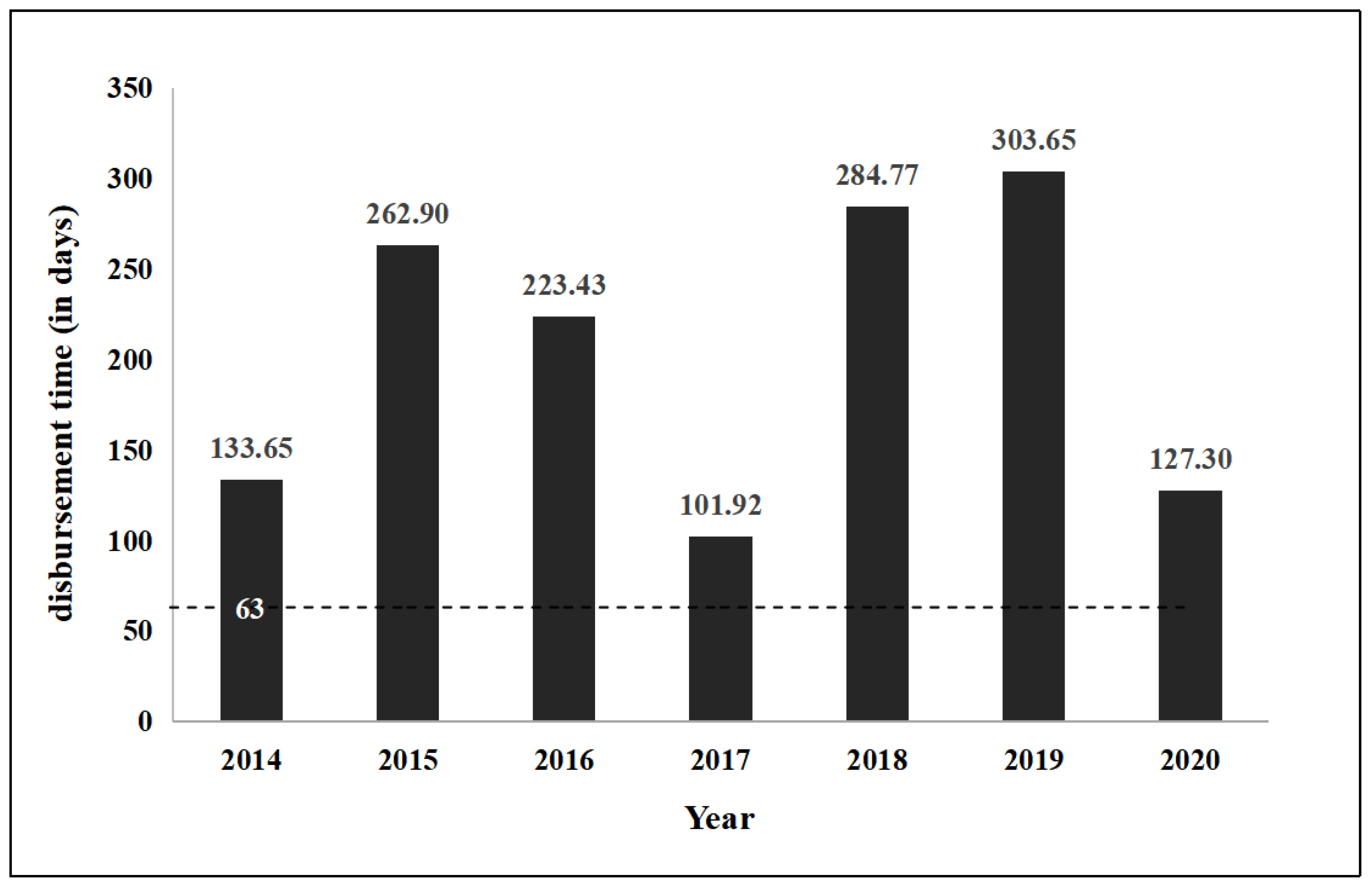

- The focus of policy effectiveness allocation has undergone a notable shift. The Chongqing land ticket model, which relies on institutional safeguards at one end and is closely tied to public welfare at the other, has placed significant emphasis on grassroots-level land reclamation and land ticket trading rules, as well as fund settlement and income distribution for farmers. Furthermore, from a temporal perspective, 2017 marks a pivotal turning point in the orientation of the policy effectiveness (Figure 5). Around this year, the emphasis of policy implementation transitioned from accelerating institutional construction to enhancing the income rights and interests of farmers. This shift occurred because, following the overheating of the trading market, farmers’ awareness of property rights gradually increased. At this time, concentrated feedback regarding issues such as non-standardized reclamation procedures and prolonged compensation payment cycles prompted policymakers to implement moderate reforms in the land ticket model, thereby addressing relevant complains.

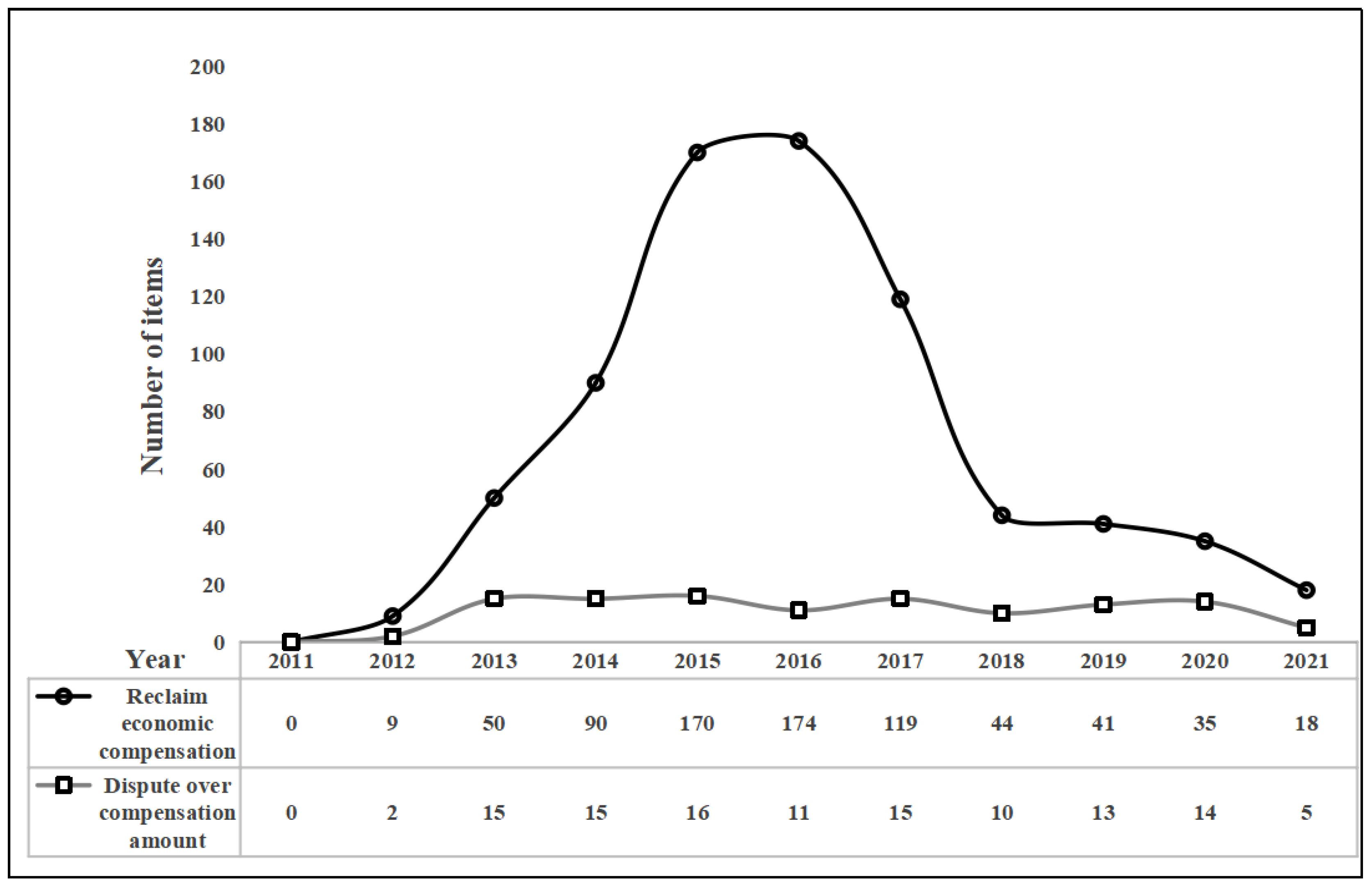

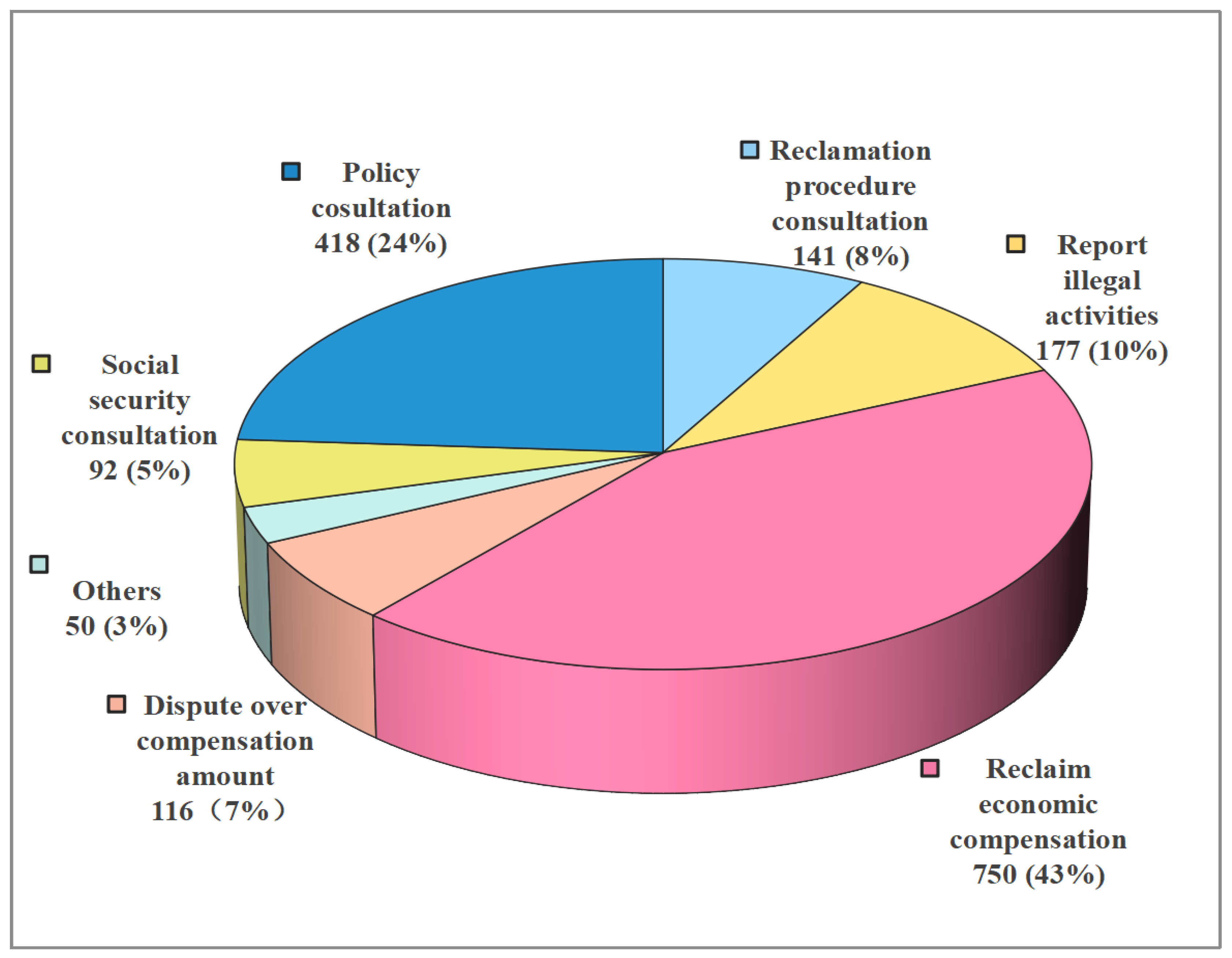

4.2. Key Information of Citizen Feedback in the Chongqing Land Ticket Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Why Is Policy Effectiveness More Focused on Institutional Construction?

- The pioneering nature of the Chongqing land ticket model necessitates a focus on policy effectiveness. In the early stages of policy formulation, it is predictable that decisions will prioritize rapid enhancement of core content construction. As an early implementation of TDR program in China, the Chongqing land ticket model lacks mature references for guidance. Local governments must explore a viable path within the existing land institution framework, ensuring compliance with higher-level laws while facilitating market-based transactions of rural construction land. From 2008 onward, it took seven years of piloting before the various components of the policy were officially established. During this period, the regulation permitting rural construction land to enter the market represented an innovative measure grounded in China’s land management realities, requiring extensive supporting policies to ensure the model’s operational success.

- Accelerating the institutional construction of land ticket model can enhance the political capital for local government officials’ promotion. As previously discussed, the land ticket model was a pilot program initiated by Chongqing Municipality under authorization from the central government. Since innovative achievements have been incorporated into the evaluation criteria for officials, the outcomes of pilot programs, as a form of policy innovation performance, have become a stepping stone for local government officials (policy makers) in their pursuit of career advancement [80]. For Chongqing’s local government officials, the land ticket model, being the first authorized, provided an excellent opportunity to demonstrate their policy design and implementation capabilities to the central government. However, as the central government extended its authorization to other regions, the uniqueness of Chongqing diminished. Distinctive localized land ticket models gradually formed a “pilot competition,” where those achieving remarkable results in pilot programs and developing localized experiences that attract greater attention and recognition from the central government would stand a better chance of promotion [81], while others might miss opportunities or even face elimination. Therefore, it is understandable that Chongqing’s policymakers adopted the strategy of accelerating the institutional construction of the land ticket model to transform it into a “star pilot program”.

- The rapid and comprehensive establishment of an institution related to land tickets can effectively address the government’s urgent need for land space. Land tickets provide at least an additional 10% of new construction land, significantly mitigating the challenge of insufficient development space. Although regulations stipulate that the total volume of land ticket transactions should not exceed 10% of the state-issued annual plan for new construction land, this limit has been frequently surpassed in practice. For instance, in 2020, the former Ministry of Land and Resources approved 190,000 mu of new construction land for Chongqing, while land ticket transactions amounted to approximately 27,000 mu, accounting for 14.21%. The supplementary construction land facilitated by land ticket has expanded opportunities for local industrial and real estate development in Chongqing and enhanced the government’s leverage in attracting investment. This clearly explains why the government is motivated to expedite the improvement of institutional frameworks to ensure the smooth functioning of land ticket transactions.

- The trading of land ticket can generate substantial off-budget fiscal revenue for the government. The rule that a “land ticket must be converted into land use rights through auctions” allows the government to capture the residual value of land development rights that have not been fully commercialized. Since land ticket trading represents a cross-regional model, the land value increment generated during this process is ultimately reflected in the price of the converted construction land indicators. This price consists of two components: the nominal value of the land ticket and the premium from the auction of the land transfer. When construction land indicators are converted into commercial or residential land, the latter’s proportion significantly increases, meaning that most of the land value increment accrues to local governments. In contrast, farmers receive only a small fraction of the revenue from land ticket trading. While the price of land ticket barely covers the costs associated with converting them into industrial land, developers must still pay substantial additional fees to the government when they chase for commercial or residential land. This implies that the remaining portion of the market price for land development rights—payable by developers to farmers—is effectively transferred to the government in the form of land transfer fees. Consequently, the significant profits the government derives from the specific rules of the land ticket model, underpinned by its monopoly in the primary land market, serve as a key driver for accelerating the refinement of the policy’s core content.

5.2. Why Is Citizen Feedback More Concerned with Procedural Justice?

- Certain procedures of the Chongqing land ticket model have infringed upon the legitimate rights and interests of farmers. This primarily results from the excessive administrative intervention by the government in land ticket transactions. According to the regulations, both the total volume of land ticket transactions and the transaction timing are determined by government departments. After voluntarily reclaiming their homesteads, farmers must patiently await their turn within designated transaction batches. Furthermore, farmers are unable to negotiate directly with buyers but must entrust the government to conduct transactions on their behalf, ultimately accepting the transaction outcomes passively. Although land ticket transactions incorporate market mechanisms such as auctions, the government’s excessive control over these transactions has undermined farmers’ rights to participation and transactional equality. This prevents them from fully realizing the value of their land rights and fails to ensure that transaction proceeds will not be intercepted or misappropriated by the government.

- Farmers urgently require the income from land ticket transactions as start-up capital for adapting to urban life. In China, the identities of rural and urban residents are differentiated by the “hukou” system. The right to use homesteads free of charge is one of the few privileges afforded to individuals with a rural “hukou” [82]. When farmers apply to participate in land ticket transactions, they are relinquishing this benefit and forfeiting their right to a rural residence. Consequently, these individuals must decide whether to relocate to urban areas. However, under the “hukou” system, farmers are unable to access the same identity-based privileges as urban residents. To ensure their children receive equitable access to quality compulsory education, as well as better medical and pension benefits, they must incur additional costs [83]. This also increases the likelihood that farmers migrating to cities will encounter significant hardships. They cannot return to rural areas, as their homesteads have been reclaimed, leaving them without a fallback option should they leave the city. Moreover, if they remain in urban areas, they face elevated living costs due to systemic identity-based discrimination. Although the local government in Chongqing pledged to grant urban “hukou” to farmers relocating to the city as part of its household registration reform, the policy was not implemented instantaneously and required a substantial amount of time for full execution. The funds from land ticket transactions serve as a crucial safeguard during their transition period of shifting between rural and urban identities. Consequently, delays in compensation disbursement can lead to significant dissatisfaction among them.

- Farmers exhibit relatively low sensitivity to the price of land ticket. On the one hand, their expectations regarding the transaction value of homesteads are comparatively modest. Land tickets arise from homesteads reclamation by farmers; however, the transfer of rural homesteads in China is restricted within collective economic organizations, and urban–rural transaction channels remain unopened. Consequently, there is no unified urban–rural market to reveal the market value of rural homesteads. Farmers’ perception of homestead value primarily stems from prices in the rural transaction market, which are significantly lower than concurrent urban housing prices. On the other hand, farmers lack more advantageous options for converting land assets into cash. Prior to the land ticket model, under the dual urban–rural system in China, the sole method for transforming rural collective construction land into urban state-owned construction land was through land expropriation. However, land expropriation compensation in China is not based on real-time land market prices but rather determined by government-set standards. If the per-unit-area transaction price of land ticket exceeds the expropriation compensation standard, farmers have no rational grounds to decline participation in land ticket transactions. Over the past decade, the Chongqing Municipal Bureau of Land and Housing Administration has adjusted the transaction guidance price of land ticket upward three times to safeguard the minimum income of participating farmers. In 2019, the minimum protection price per mu of land ticket was raised to CNY 178,000. After deducting reclamation costs of CNY 37,000 and distributing 85% to farmers, a remaining balance of CNY 119,850 was allocated. This amount significantly surpasses the concurrent land expropriation compensation standard. Given the absence of alternative channels for converting land assets into cash, farmers tend to accept this outcome relatively willingly.

5.3. Policy Improvement Suggestions

- Strengthen the protection of farmers’ rights and interests in the early stage of policy design. The initial design of a policy is a critical juncture that determines its long-term evolution. Once an initial policy is implemented, it will form a specific pattern of interest distribution and action rules. The vested interest groups within it will tend to maintain the existing policy content to preserve their advantageous position. In the land ticket model, it can be observed that the absence of the rights and interests of farmers, a vulnerable group, has been systematized and legalized, and even gradually internalized by them as a common belief, making it difficult to reverse through subsequent remedial policies. Therefore, it is imperative to address this potential risk at the source of policy design. (1) During the early stages of policy formulation, individual farmers should be granted full participation rights. Representatives of farmers could be included in the team of policy designers, ensuring that issues genuinely concerning farmers are integrated into the policy framework. (2) The valuable experience from pilot program should be fully leveraged. For highly controversial or broadly influential policy updates, small-scale pilots should precede district-wide implementation, with decisions based on feedback and evaluation outcomes. (3) Given the loss of homesteads during land ticket transactions and the challenges farmers face upon urban migration, a “compensation-first, reclamation-second” fund allocation mechanism could be established, supported by financial contributions from land reserve institutions and urban investment entities. (4) The bargaining right over land ticket should gradually shift to farmers, enabling them to negotiate directly with potential buyers for more transparent pricing and expedited revenue disbursement. (5) Stricter punitive measures must be implemented to supervise and prevent delays in farmers’ legitimate earnings, particularly addressing issues such as the withholding or misappropriation of land ticket funds by village cadres.

- The government should minimize excessive intervention in land ticket trading. In this model, local governments have implemented a structural substitution of administrative power for market mechanisms through full-chain control over “indicator generation–pricing–trading–revenue distribution.” In contrast to the role of the government in the USA TDR programs, local governments in China should reassume their roles as platform builders and transaction regulators. (1) In the USA TDR programs, the transactions of land development rights typically involve third-party intermediaries (such as appraisal agencies, legal services, and non-profit organizations), enabling land right holders to access transaction plans that align with market value assessments. Local governments in China should progressively introduce independent third-party transaction service institutions into land ticket trading while gradually restricting the functions and authority of trading platforms under their jurisdiction, thereby minimizing administrative intervention in land ticket trading. (2) Drawing on the operational methods of the USA TDR programs, local governments should gradually phase out price controls and total volume controls on land ticket. Pricing and trading volumes for land ticket should be entirely determined by market forces. (3) Likewise, the government should refocus its policy priorities on protecting areas designated for transferring land development rights. Compared to the stringent regulatory measures applied to development density in the USA TDR programs, the Chongqing land ticket model appears relatively lenient in managing farmland post-reclamation. A potential solution could involve integrating reclaimed farmland through leasing rather than expropriation, facilitating scale-agriculture-operation with enhanced productivity and stronger protection.

- In policy updates, it is essential to respond to public demands. The emergence of online political consultation platforms has enhanced the capacity of policy audiences to provide upward feedback. However, the government’s resolve within the land ticket model to translate scattered public demands into concrete policy outputs remains insufficient. Currently, the government primarily addresses citizen feedback through online channels. While this approach can swiftly alleviate some complaints, it fails to systematically adjust key aspects such as program design, distribution schemes, and rights protection in the land ticket model. Consequently, it does not effectively reduce the generation of negative feedback. (1) Local governments can introduce appealing and comparable policies in relevant management domains, explore new market-oriented mechanisms for land factors, and thereby empower farmers with the right to “vote with their feet”. This approach can compel existing policies to address their deficiencies and deliver tangible benefits to farmers through inter-policy competition. (2) The local government should regularly analyze online public opinion, systematically incorporate reasonable, widespread, and actionable demands into new policy content, and ensure continuous policy updates to align with public expectations and foster timely governmental responses.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This indicator, which is embedded in China’s land use master plans and annual land use plans, serves as a critical prerequisite for local governments to secure approval from higher-level authorities for converting rural land into urban construction land. The central government establishes the total quota of this indicator for each planning period and allocates it quantitatively to local governments on an annual basis. Furthermore, if the indicator is not fully utilized within a year, it becomes invalid, and any unused portion cannot be traded among local governments. Occupying rural land without sufficient use of this indicator constitutes a violation of the Land Administration Law, and the responsible local government may face accountability measures imposed by the central government. |

| 2 | The design concept of this policy was initially outlined in a 2004 State Council document (Decision on Deepening Reform and Strictly Managing Land). Its core principle is to “encourage the reclamation of rural construction land and link the expansion of urban construction land to the reduction of rural construction land.” Beginning in 2006, the policy was piloted in several provinces, including Shandong, Jiangsu, and Sichuan. By 2008, Chongqing city was officially incorporated into the policy’s implementation framework. |

| 3 | For more details, please refer to the Overall Program of Comprehensive Supporting Reform Pilot Program for Integrating Urban and Rural Areas in Chongqing Municipality. |

| 4 | It should be noted that since 2018, ecological land types such as grassland and woodland have also been included in the scope for generating land ticket, meaning that in addition to arable land, rural homesteads can be reclaimed into other forms of agricultural land based on the suitability of the area. However, the construction of residential buildings and profit-oriented facilities is strictly prohibited. For details, see the Opinions on Expanding the Ecological Function of Land Quotas to Promote Ecological Restoration (No.4 Document of Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration [2018]). |

| 5 | The data was disclosed by a leader of the Chongqing Municipal Development and Reform Commission. (Source: https://www.cq.gov.cn/zt/yyztls/lsjcx/202409/t20240904_13716936.html, accessed on 22 October 2024) |

| 6 | (1) Application for reclamation, (2) Reclamation procedure, (3) Reclamation check and acceptance, (4) Application for transaction, (5) Rules of transaction, (6) Settlement of compensation payments, (7) Revenue distribution, (8) Use and circulation of land ticket, (9) Organizational support. |

| 7 | It should be noted that the Chongqing land ticket model is still operating normally. This study selected policy documents from 2008 to 2020 because, during this period, after multiple rounds of policy supplementation and refinement (such as expanding the scope of land reclamation recognition and raising the minimum transaction protection price, etc.), the mechanism of the Chongqing land ticket model has become relatively stable. Based on the policy document screening criteria established in this study, no significant policy changes impacting this model were identified between 2021 and 2024. Currently, this model continues to adhere to the fundamental principles outlined in the 2015 (Measures of Chongqing Land Ticket Management). However, the revised edition of this policy text has been included in the Chongqing Municipal People’s Government’s legislative plan for 2025 and is currently undergoing preliminary research. The Chongqing land ticket model may thus experience another round of policy innovation in the near future. |

| 8 | The Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration was directly responsible for the land ticket model. Following the “ministerial reform” in 2019, the functions of the Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration were reorganized and merged into a new department, the Chongqing Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources. |

| 9 | Notably, in 2010, no messages related to the Chongqing land ticket model were observed, and thus that year was excluded from the statistical analysis. Furthermore, given that the actual program cycle of the Chongqing land ticket model—from the district or county land management department accepting reclamation applications to the final disbursement of transaction proceeds following a land ticket trade—typically lasts around one year, the deadline for collecting citizen feedback was set for the year following the last policy update (2020). While this approach may overlook some delayed information posted online by farmers, such content generally exhibits lower urgency compared to feedback generated during the policy change period. Excluding this delayed information helps reduce noise and facilitates the extraction of key information to better observe farmers’ real-time responses to policy changes. |

| 10 | The stopword dictionary used in this study was sourced from Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT), containing 767 words lacking substantive meaning, including modal particles (such as “ah“, “oh“), special symbols (such as “&“, “☆“), and conjunctions/prepositions (such as “in“, “and“). Additionally, to ensure the validity of the word segmentation results, we updated the stopword dictionary by adding 126 common but irrelevant words found in policy consultation texts (Table 3). The types and quantities of the added words are as follows: (1) 36 numerals and time words (such as “15”, “2019”, etc); (2) 43 county and district names (such as “Wanzhou”, “Dadukou”, etc); (3) 47 frequently-occurring words with no textual meaning (such as “Hello”, “Leader”,” Thank you”, “Hope”, “Suggest”, “Want”, etc.). |

| 11 | Refers to No.127 Document of Chongqing Municipal People’s Government [2008] and No.295 Document of Chongqing Municipal People’s Government [2015] (as a governmental decree). |

| 12 | The “relocation for poverty alleviation” is a poverty alleviation mechanism mandated by the central government of China. It involves relocating impoverished populations residing in areas with harsh ecological environments, frequent natural disasters, or severely constrained development conditions to new locations that offer better living conditions, basic public services, and developmental opportunities through centralized resettlement programs. This initiative aims to reduce the number of people living in poverty. The Chongqing land ticket model aligns closely with this central government requirement. As early as 2013, Chongqing city started encouraging impoverished farmers in mountainous regions to apply for the reclamation of their homesteads and subsequently improve their living standards by trading land tickets to generate income. For details, please refer to Opinions on Promoting the Ecological Poverty Alleviation Relocation in Mountainous Areas. (No.9 Document of Chongqing Municipal People’s Government [2013]) |

| 13 | The policy goal of “institutional construction” is related to (1) application for reclamation, (2) reclamation procedure, (3) reclamation check and acceptance, (4) application for transaction and (5) rules of transaction; while the policy goal of “profit distribution” is related to (6) settlement of compensation payments and (7) revenue distribution. |

| 14 | The regulation specifying a 63-day timeframe for land ticket transactions to payment disbursement is outlined in the "Notice on Issuing the Plan for Optimizing the Process of Rural Construction Land Reclamation and Land Ticket Trading" (No.921 Document of Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration [2013]). |

References

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Ma, G. Contribution of Marketization to China’s Economic Growth. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 46, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Zhou, Z. The Course, Basic Experience and Deepening Path of Rural Factor Marketization Reform in China. Reform 2020, 317, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Li, C.; Xia, F. Strategic Thinking on Deepening the Land Factor Mar ketization Reform. Reform 2020, 320, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. A Study on the Compensation of Farmland Expropriation from a Perspective of Development Value. Issues Agric. Econ. 2014, 35, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rithmire, M.E. Land institutions and Chinese political economy: Institutional complementarities and macroeconomic management. Polit. Soc. 2017, 45, 123–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, T. The issue of land in China’s transition and urbanization. In China’s Great Urbanization; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Tao, R. The ‘Zhejiang Mode’of land development rights transfer and trading—Institutional origins, operating model and its important implications. J. Manag. World 2009, 8, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Mo, Z.; Peng, Y.; Skitmore, M. Market-driven land nationalization in China: A new system for the capitalization of rural homesteads. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. 22. The structure of and changes to China’s land system. In China’s 40 Years of Reform and Development; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2018; p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.; Upham, F. Evolution of relational property rights: A case of chinese rural land reform. Iowa Law Rev. 2014, 100, 2479–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, N. Land acquisition compensation in China–problems and answers. Int. Real Estate Rev. 2003, 6, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, T.; Xu, G.; He, J.; Xu, Y.; Meng, H. The effect of land use planning (2006–2020) on construction land growth in China. Cities 2017, 68, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Zhu, J.; Qian, L.; Zheng, L. Study on the Rural Land Factor Marketization Reform in China. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 2, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Yang, Q. Restructuring the state: Policy transition of construction land supply in urban and rural China. Land 2020, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarguette, R. Chongqing: Model for a new economic and social policy? China Perspect. 2011, 4, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F. Hukou system reform and unification of rural–urban social welfare. China World Econ. 2011, 19, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Feng, S.; Wang, Q. Study on the effect of the introduction of market mechanism on the allocation efficiency of new urban construction land. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Spillover effects on transaction of land development right and regional economic growth: Empirical analysis based on land quota trading policy in Chongqing. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, A.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q. Effects of the land bill system in Chongqing municipality on the integrated development of urban and rural areas and implications. Prog. Geogr. 2024, 43, 888–904. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Wu, X. A study on the impact of the land ticket system on the property income of farmers. Agric. Econ. 2020, 7, 84–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, X.; Wang, W. Poverty Reduction Effects of Rural Collective Construction Land Transfer. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2021, 38, 62–83. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Q. Spatio-temporal characteristics of land coupon trading and its coupling mechanism with urban-rural migration in Chongqing. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 2926–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Fu, H. Study on Land Ticket Pattern and the Transfer System of Rural Collective Construction Lands: Taking Chongqing as an Example. J. Public Manag. 2011, 8, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Gao, Y. Effects of Transfer of Land Development Rights on Urban–Rural Integration: Theoretical Framework and Evidence from Chongqing, China. Land 2023, 12, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, P. The Impact of Land Development Right Transaction on Urban-rural Income Gap and Its Mechanism: An Example of the Practice of Chongqing Land Ticket. Chin. Rural Econ. 2022, 3, 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Jin, X. Study on Laws of Policy Change from the View of Dynamic Equilibrium. J. Public Manag. 2005, 2, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z.; Mu, Y. Land Market Reform in China: Institutional Change and Character Analysis. Issues Agric. Econ. 2013, 34, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y. From Index Rights Trading to Development Rights Trading—The enlightenment of TDR system in the USA to land ticket trading system. Hebei Law Sci. 2016, 34, 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. On Responsible Government. J. Renmin Univ. China 2000, 2, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.M. Retrofitting the steel frame: From mobilizing the masses to surveying the public. In Mao’s Invisible Hand; Brill: Leiden, Netherlands, 2011; pp. 237–268. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J. Study on functional mechanism and effectiveness of Land ticket system in the process of New-type urbanization. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S. Expropriation in the Name of Rights: Transferable Development Rights (TDRs), the Bundle of Sticks and Chinese Politics. New York Univ. J. Law Lib. 2019, 13, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, C. Exploration of Urban and Rural Land Ticket Trading from the Perspective of Land Development Rights and Institutional Change: An Analysis of the Chongqing Model. Reform Econ. Syst. 2010, 5, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, C.; Niu, D.; Gao, Q. Study on Risk Assessment of Chongqing Land Tickets System. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zeng, C. Analysis on Land Ticket Transaction System of Chongqing Municipality. Asian Agric. Res. 2013, 5, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Wang, N. A Study of the Protection of Farmers’Homestead Exit Revenue in Chongqing: Basing on Comparative Revenue. China Land Sci. 2016, 30, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, W.; Xiong, H. The Issue Research on Land Ticket Price and Income Distribution Based on Game Theory in Chongqing. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 4, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X. An Economic Analysis of the Game Between Each Beneficiary in Land Ticket Trade. Reform Strategy 2010, 26, 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Chen, X. The Land Quittance Intention of Peasants and The Key Link Consideration: Example from Chongqing. Reform 2011, 10, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Functional elements and households homestead withdrawal: Evidence samples from Liaoning and Chongqing. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2024, 23, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.S.; Lin, W. Transforming rural housing land to farmland in Chongqing, China: The land coupon approach and farmers’ complaints. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, G. Transferable density in connection with zoning. Tech. Bull. 1961, 40, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Costonis, J.J. Development rights transfer: An exploratory essay. Yale Law J. 1973, 83, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J. Past, present, and future constitutional challenges to transferable development rights. Wash. Law Rev. 1999, 74, 825. [Google Scholar]

- Barrows, R.L.; Prenguber, B.A. Transfer of development rights: An analysis of a new land use policy tool. Am. J. Agr. Econ. 1975, 57, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizor, P.J. Making TDR work: A study of program implementation. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 1986, 52, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruetz, R. Saved by Development: Preserving Environmental Areas, Farmland and Historic Landmarks with Transfer of Development Rights; Arje Press: Burbank, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz, M.D.; Machemer, P.; Pruetz, R. Planners’ experiences in managing growth using transferable development rights (TDR) in the United States. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, L.; Lovell, S.J. Combining spatial and survey data to explain participation in agricultural land reservation programs. Land Econ. 2003, 79, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomitz, K.M.; Thomas, T.S.; Brandão, A.S.P. The economic and environmental impact of trade in forest reserve obligations: A simulation analysis of options for dealing with habitat heterogeneity. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2005, 43, 657–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micelli, E. Development rights markets to manage urban plans in Italy. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yu, L.; Choguill, C.L. “Dipiao”, Chinese approach to transfer of land development rights: The experiences of Chongqing. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Xu, Z.; Li, J. Promote or Demote? Investigating the Impacts of China’s Transferable Development Rights Program on Farmers’ Income: A Case Study from Chongqing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Herrera, Y.; Shirley, M.; Benham, L.; Desapio, D.; Vortherms, S. “Flying Land”: Intergovernmental Cooperation in Local Economic Development in China; Working paper; University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yep, R.; Forrest, R. Elevating the peasants into high-rise apartments: The land bill system in Chongqing as a solution for land conflicts in China? J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Guo, Z. Is Urban and Rural Construction Land Quota Trading “Chicken Ribs”? An Empirical Study on Chongqing, China. Land 2022, 11, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.; Huang, Z. Comparative analysis of land ticket transaction pilots. Res. Real Estate Law China 2018, 18, 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Policy networks and the mechanisms for achieving public policy effectiveness. J. Manag. World 2006, 9, 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Zhong, W.; Sun, W. Policy measurement, coordinated policy evolution and economic performance: An empirical study based on innovation policy. J. Manag. World 2008, 9, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Q. Evaluation of the efficiency of city land intensive utilization policy based on policy quantification in Nanjing City. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, D.; He, M.; Chen, J. Research on the Multidimensional Coordination of the Urban-Rural Integration Development Policies between the Central and the Local Governments. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2023, 45, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Cao, Y.; Su, R.; Qiu, M.; Zhou, W. Evolution Characteristics and Laws of Cultivated Land Protection Policy in China Based on Policy Quantification. China Land Sci. 2020, 34, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, C.; Su, J. Remolding the Policy Text Data through Documents Quantitative Research: The Formation, Transformation and Method Innovation of Policy Documents Quantitative Research. J. Public Manag. 2015, 12, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Harmelink, M.; Nilsson, L.; Harmsen, R. Theory-based policy evaluation of 20 energy efficiency instruments. Energy Effic. 2008, 1, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonnell, L.M.; Elmore, R.F. Getting the job done: Alternative policy instruments. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1987, 9, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemelmans-Videc, M.; Rist, R.C.; Vedung, E.O. Carrots, Sticks, and Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Su, X.; Yao, Z.; Dong, L.; Lin, Q.; Yu, S. How Do Citizens View Digital Government Services? Study on Digital Government Service Quality Based on Citizen Feedback. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A. Internet Politics: States, Citizens, and New Communication Technologies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Balla, S.J.; Liao, Z. Online consultation and citizen feedback in Chinese policymaking. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 2013, 42, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, H. Online political consultation and Construction of government response mechanisms. E-Gov. 2017, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J. Network in Politics and the Social Management Practice Innovation. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 4, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, R.; Esteve, M.; Jankin Mikhaylov, S. Improving public services by mining citizen feedback: An application of natural language processing. Public Adm. 2020, 98, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lei, H.; Li, X.; Wu, J. Deep Learning in NLP: Methods and Applications. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. China 2017, 46, 913–919. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, C. Policy Attention, Measurement and Economic Benefits: LDA Modeling Based on Regional Co-development Policy Text. Stat. Res. 2024, 41, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; Jin, G.; Cai, Y.; Liu, L.; Cao, H.; Li, W.; Cai, R. Study on data mining of hydrogen energy policy in China based on natural language processing technology. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2024, 39, 1032–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Li, L.; Li, D. The public opinion effect and enlightenment of the introduction of the three-child policy—An analysis of network big data based on NLP. China Youth Study 2021, 10, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Yao, Y.; Wang, H. Peasants’ Petitions in Land Expropriation: Big Data Analysis Based on Local Leadership Message Board. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 7, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Tan, C.; Huang, Q.; Liu, H. Natural language processing (NLP) in management research: A literature review. J. Manag. Anal. 2020, 7, 139–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. Land expropriation, protest, and impunity in rural China. Focaal 2009, 2009, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, N. Competition for Innovation: A New Competitive Mechanism of Local Government. Wuhan Univ. J. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2017, 70, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Yang, H. Competitive Experimental Model of Policy Innovation in China. Local Gov. Res. 2022, 3, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. The Particularity and Potential Pathways for Reform of the Rural Homestead System. J. Chin. Acad. Gov. 2015, 3, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, S. What determines migrant workers’ life chances in contemporary China? Hukou, social exclusion, and the market. Mod. China 2011, 37, 243–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score | Scoring Criteria | Score | Scoring Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power dimension (P) | G7—Revenue distribution | ||

| 5 | P1- National People’s Congress (PRC) | 5 | Clearly define the ownership of the proceeds from the transaction and propose a specific plan for the distribution of revenue, etc. |

| 4 | P2- State Council (PRC) | 4 | Clarify revenue ownership and outline a basic distribution framework; some roles or proportions are mentioned, though lacking full institutional detail. |

| 3 | P3- Chongqing Municipal People’s Government | 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. |

| 2 | P4- Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration | 2 | Touch on benefit sharing in general terms, without indicating who holds ownership or how revenue is to be divided. |

| 1 | P5- Chongqing Country Land Exchange (CCLE) | 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle. |

| Goal dimension (G) | G8—Use and circulation of land tickets | ||

| G1—Application for reclamation | 5 | Specify the conditions and area for land tickets, clearly define the conditions for the circulation of land tickets and the attribution of benefits, etc. | |

| 5 | Clearly define the prerequisites for reclamation application, provide a detailed guide to the process, and specify the areas and types of land that can be reclaimed to generate land tickets, etc. | 4 | Define basic conditions and partial spatial scope for land ticket use; offer preliminary guidance on circulation and benefit attribution, though not fully elaborated. |

| 4 | Clearly state goals and main conditions for reclamation; outline basic steps and partially specify land types or areas. Some guiding requirements details are present but not comprehensive. | 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. |

| 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. | 2 | Mention land ticket circulation or use without clarifying applicable areas, conditions, or benefit arrangements. |

| 2 | Mention general goals and land types but lack procedures or clear criteria. Implementation depends heavily on interpretation. | 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle. |

| 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle. | G9—Organizational support | |

| G2—Reclamation procedure | 5 | Clearly define the responsibilities of each department and provide specific work guidelines or pilot project plans, etc. | |

| 5 | Clarify the cost of reclamation programs, develop a procedural plan for generating construction land indicators, etc. | 4 | Identify key responsible departments and outline general duties or arrangements; some work guidelines are included but lack full procedural clarity. |

| 4 | State the estimated costs and outline steps for generating land indicators; provide partial financial or procedural clarity. Some elements remain vague or incomplete. | 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. |

| 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. | 2 | Briefly reference departmental roles without specifying tasks, coordination mechanisms, or implementation steps. |

| 2 | Mention costs or land indicators vaguely without specific plans or standards. | 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle. |

| 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle. | Measure dimension (M) | |

| G3—Reclamation check and acceptance | M1—Command type | ||

| 5 | Quantitative standards and implementation procedures for the completion and acceptance of reclamation projects are established, as well as the text materials required, etc. | 5 | Clearly define the regulatory requirements for indicators such as the total amount of transactions, spatial scale, and reclamation quality, or the process of reclamation application and land ticket transactions, or clearly define the punitive measures for violating the above requirements. |

| 4 | Set basic acceptance criteria and describe parts of the procedure or required materials. Quantitative indicators may be partial or general. | 4 | Set preliminary thresholds or assessment criteria for transaction scale, quality, or process control; mention regulatory or punitive intent, but details are partially specified. |

| 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. | 3 | The above is included, but lacks detailed quantification, evaluation criteria, or penalties. |

| 2 | Mention acceptance in principle but lack concrete criteria, procedures, or document requirements. | 2 | Address regulatory issues in general terms, with limited reference to benchmarks, evaluation systems, or enforcement tools. |

| 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle | 1 | The above is included, but remains at the level of calling, advocacy, and publicity. |

| G4—Application for transaction | M2—Incentive type | ||

| 5 | Regulating the conditions for applying for land transfer and specifying the materials to be submitted when applying for land ticket trading, etc. | 5 | Clearly define financial, tax, information, talent, and organizational and technology support plans and provide a reduction or exemption from fees and charges. Clearly define a revenue distribution plan or price protection mechanism. |

| 4 | Clearly describe application conditions and list some required documents, but details may be incomplete or lack procedural clarity. | 4 | Outline support measures in key areas like finance, taxation, or talent; include partial provisions on revenue sharing or fee reduction, though lacking full operational clarity. |

| 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. | 3 | The above is included, but lacking a detailed description of the supporting content, distribution plan, or protection mechanism. |

| 2 | Briefly mention the trading application, with vague or no mention of supporting materials or requirements. | 2 | Mentions support or incentive themes without clarifying implementation pathways, responsible bodies, or safeguard arrangements. |

| 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle | 1 | The above is included, but remains at the level of calling, advocacy, and publicity. |

| G5—Rules of transaction | M3—Guidance type | ||

| 5 | Clearly define the detailed rules for the types, varieties, methods, and processes of land ticket transactions, etc. | 5 | Actively encourage farmers to participate in the production of land tickets and protect their rights and interests. Clearly require public disclosure or follow-up supervision of information such as reclamation plans and transaction results, clearly provide details of pilot projects, and provide a list of rights and responsibilities of relevant departments. |

| 4 | Specify main transaction types and outline general methods or procedures; some rules are clear, but others remain ambiguous or incomplete. | 4 | Emphasize farmer participation and outline basic rights protections; includes partial disclosure requirements or details, though some aspects lack binding force. |

| 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. | 3 | The above is included, but there is a lack of strict regulations on the principles of voluntariness and public oversight. Only a list of pilot projects is given, and only a list of functional departments responsible for policy implementation is given. |

| 2 | Vaguely refer to land ticket transactions without specifying types, methods, or procedures. | 2 | Refers to participation or transparency in broad terms, without specifying rules, enforcement mechanisms, or the scope of departmental responsibilities. |

| 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle | 1 | The above is included, but remains at the level of calling, advocacy, and publicity. |

| G6—Settlement of compensation payments | |||

| 5 | Establish a minimum protection price for land ticket transactions, clearly specify the process and time requirements for the allocation of payments, and establish a mechanism to monitor and publish the results of the allocation, etc. | ||

| 4 | Proposes baseline pricing or outlines general payment allocation steps; includes partial timelines or oversight measures, though some aspects lack precision. | ||

| 3 | Policy goals are clear but lack detailed explanations or quantitative standards. | ||

| 2 | Refers to payment distribution or pricing without offering specific mechanisms, timelines, or enforcement procedures. | ||

| 1 | Only expressing policy expectations or requirements of principle | ||

| No. | Year | Department | Document Title | Document Number | Format | Code | Content Analysis Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2008 | Chongqing Municipal People’s Government | Provisional administrative measure of Chongqing Country Land Exchange | No.127 Document of Chongqing Municipal People’s Government [2008] | Measure | 1 | |

| 1-1 | Article 4. Trading species | ||||||

| 1-2 | Article 5. Monitoring agency | ||||||

| …… | …… | ||||||

| …… | 1-18 | Article 31. Protection of interests allocation | |||||

| 5 | 2010 | Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration | Supplementary opinions on improving the distribution of land ticket payments | No.220 Document of Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration [2010] | Opinions | 5 | |

| 5-1 | Section 1. Use of payments of rural collective construction land reclamation | ||||||

| …… | 5-2 | Section 2. Use of payments that higher than the cost of reclaiming rural collective construction land | |||||

| 39 | 2020 | Chongqing Municipal People’s Government | Execution plan for reforming the property rights system for natural resource assets in Chongqing Municipality | No.56 Document of Chongqing Municipal People’s Government General Office [2020] | Plan | 39 | |

| 39-1 | Section 7. Promoting the restoration of natural ecological space systems and reasonable compensation |

| Category | Newly Added Stop Words |

|---|---|

| Numerals and time words | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2020, 2021, Year, Month, Day. |

| County and district names | Chongqing, Municipality, Wanzhou, Qianjiang, Fuling, Yuzhong, Dadukou, Jiangbei, Shapingba, Jiulongpo, Nan’an, Beibei, Yubei, Banan, Changshou, Jiangjin, Hechuan, Yongchuan, Nanchuan, Qijiang, Dazu, Bishan, Tongliang, Tongsan, Rongchang, Kaizhou, Liangping, Wulong, Chengkou, Fengdu, Dianjiang, Zhong, Yunyang, Fengjie, Wushan, Wuxi, Shizhu, Xiushan, Youyang, Pengshui, County, District, Autonomous Region. |

| Frequently-occurring words with no textual meaning | For this reason, Over the years, Attach importance to, Earnestly request, The masses, Pay attention to, Understand, Due to, Implement, Further, Then, Carefully, All along, Handle, We, I, Concerning, Matter, Thing, Attach importance to, Explanation, Situation, At present, Coordinate, Reply, Response, Hope for, Still, Problem, Unit, Gratitude, think, Long overdue, However, Hello, Indicator, Homestead, Handle, Reflect, Want to say, You, Hello, Leader, Thank you, Hope, Suggest, Want. |

| Year | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total |

| 1. Application for reclamation | 67.00 | 0 | 0 | 86.17 | 17.00 | 0 | 16.67 | 22.50 | 0 | 0 | 16.67 | 0 | 0 | 226.00 |

| 2. Reclamation procedure | 23.50 | 13.67 | 17.33 | 36.00 | 25.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.67 | 0 | 0 | 129.17 | |

| 3. Reclamation check and acceptance | 0 | 14.67 | 0 | 11.33 | 0 | 0 | 15.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41.67 |

| 4. Application for transaction | 68.50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23.00 | 17.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 108.83 |

| 5. Rules of transaction | 153.00 | 30.50 | 16.00 | 39.83 | 10.50 | 66.33 | 0 | 290.50 | 99.00 | 14.33 | 0 | 16.33 | 22.00 | 758.33 |

| 6. Settlement of compensation payments | 0 | 0 | 107.17 | 17.50 | 0 | 0 | 42.00 | 50.17 | 65.67 | 16.67 | 0 | 0 | 299.17 | |

| 7. Revenue distribution | 17.00 | 0 | 18.33 | 11.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28.50 | 0 | 155.33 | 18.00 | 36.00 | 0 | 284.83 |

| 8. Use and circulation of land ticket | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 124.50 | 64.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 200.17 |

| 9. Organizational support | 0 | 0 | 23.00 | 33.17 | 0 | 51.00 | 48.67 | 39.00 | 17.00 | 73.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 285.17 |

| Total | 329.00 | 58.83 | 74.67 | 336.33 | 70.00 | 117.33 | 81.00 | 570.00 | 248.17 | 322.33 | 51.33 | 52.33 | 22.00 | —— |

| Department | Format Year | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Council (PRC) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Opinions | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Chongqing Municipal People’s Government | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 19 | ||||

| Measures | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Plans | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Circulars | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||||||||

| Opinions | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 9 | |||||||||

| Government decrees | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Chongqing Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Circulars | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Chongqing Bureau of Land and Housing Administration | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 16 | ||||||

| Measures | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Plans | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Provisions | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Rules | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Circulars | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | |||||||||

| Detailed rules | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Opinions | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| CCLE | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Measures | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Total | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 39 |

| Category | Amount | TF-IDF | Keywords | Frequency | TF-IDF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic compensation | 1454 | 0.16415 | compensation payment | 332 | 0.05616 |

| compensation | 489 | 0.04738 | |||

| subsidies | 179 | 0.01796 | |||

| funds | 207 | 0.01467 | |||

| payments | 110 | 0.01450 | |||

| allowances | 137 | 0.01348 | |||

| Policy consultation | 1231 | 0.10167 | policy | 723 | 0.05163 |

| consultation | 248 | 0.02673 | |||

| application | 260 | 0.02331 | |||

| Reclamation procedure | 1002 | 0.12113 | measurement | 336 | 0.03631 |

| acceptance check | 186 | 0.02575 | |||

| notifications | 230 | 0.02194 | |||

| signature | 143 | 0.01882 | |||

| surveying | 127 | 0.01832 | |||

| Transformation of identity | 670 | 0.08247 | pension insurance | 205 | 0.03014 |

| “hukou” | 227 | 0.02161 | |||

| social insurance | 157 | 0.01665 | |||

| poor household | 81 | 0.01407 | |||

| Complaints and inquiries | 363 | 0.04463 | village cadres | 194 | 0.02689 |

| village committee | 169 | 0.01774 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Ji, L.; Wang, H. The Policy Effectiveness and Citizen Feedback of Transferable Development Rights (TDR) Program in China: A Case Study of the Chongqing Land Ticket Model. Land 2025, 14, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14061285

Zhang H, Ji L, Wang H. The Policy Effectiveness and Citizen Feedback of Transferable Development Rights (TDR) Program in China: A Case Study of the Chongqing Land Ticket Model. Land. 2025; 14(6):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14061285

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hongwei, Linhong Ji, and Hui Wang. 2025. "The Policy Effectiveness and Citizen Feedback of Transferable Development Rights (TDR) Program in China: A Case Study of the Chongqing Land Ticket Model" Land 14, no. 6: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14061285

APA StyleZhang, H., Ji, L., & Wang, H. (2025). The Policy Effectiveness and Citizen Feedback of Transferable Development Rights (TDR) Program in China: A Case Study of the Chongqing Land Ticket Model. Land, 14(6), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14061285