1. Introduction

In 2018, two sectoral Territorial Action Plans (PATs)

1 were approved in the Valencian Autonomous Region: the “Plan for the Management and Revitalization of the Huerta of Valencia” and the “Green Infrastructure Plan for the Coastal Area of the Region”. Between 2020 and 2023, a new series of PATs was developed, initially aimed at organizing the three biggest metropolitan areas (Valencia, Castellón, and Alicante–Elche) and subsequently other functional areas, including the Vega Baja del Segura and the Central Valencian Counties.

This study focuses on analyzing a set of public participation activities designed and developed with stakeholders involved in the drafting of the three comprehensive PATs under study: the PAT for the Alicante–Elche functional area, the PAT for Vega Baja del Segura County, and the PAT for the Central Valencian Counties. They were all developed in accordance with the legal framework in force in the Valencian Autonomous Region. The objective of the comprehensive plans was to harmoniously structure the three main components of the territorial system: green infrastructure, settlement system, and transportation infrastructure system. Their drafting and eventual approval represented a major challenge for the planning teams, of which the authors of this paper were part, given that, at that time, no comprehensive PAT had been approved in the Valencian Autonomous Region (only sectoral PATs had been approved).

An additional challenge was the broad territorial scope of the three spatial sub-regional plans, both in terms of surface area and population of the Valencian Autonomous Region. This was especially true for the PAT for the Central Valencian Counties, a cross-border plan which spans eight counties across the two provinces of Valencia and Alicante. Accordingly, for all three cases, a public participation plan was designed and implemented to meet the demands of each territorial context.

The opportunity to compare the same type of participatory activity, carried out by the same planning team over a four-year period, is relatively uncommon and allows for meaningful conclusions to be drawn about the effectiveness of participatory processes and their integration within spatial planning.

For each of the three PATs, a comprehensive set of participatory activities was carried out in parallel to reach diverse population profiles and relevant stakeholders. Many of these activities were designed to bring participation closer to where people live. The participatory activities analyzed in this study correspond to three key stages in the planning process: (a) the initial drafting phase; (b) a “check-in” moment with citizens and local actors to discuss preliminary territorial diagnoses developed by the planners’ team; and (c) a final stage involving thematic or territorial workshops aimed at refining the diagnosis and providing input for the identification of feasible alternatives to be proposed by the plan. All these activities, which were not mandatory based on the current Valencian Law on spatial planning, took place prior to the formal public consultation phase (binding by law in this case) in order to reach agreement on the negotiated alternatives to minimize potential conflicts during the public review (consultation) process.

2. Theoretical and Contextual Frameworks: Public Participation in Spatial and Urban Planning in Spain

2.1. A Spatial Planning System Rooted in Urban Planning Traditions with a Strong Normative Approach

The effectiveness of spatial planning largely depends on public trust in institutions and in the work of public administrations to create the necessary conditions for the population’s well-being, undertaking interventions that improve living conditions and support local economies. This trust is essential for the sustainability and continuity of spatial planning as a public policy [

1]. Conversely, low levels of trust can lead to closed social contexts in which the legitimacy of institutions is questioned, posing serious challenges to territorial governance. This, in turn, threatens the possibility of ensuring governance that upholds citizens’ rights and welfare within a social and democratic state governed by the rule of law [

2]. Trust in institutions can be built by introducing and promoting active citizen involvement. Citizen participation when designing public policies legitimizes their implementation, facilitates execution, and allows for solving specific problems by harnessing collective intelligence.

In the Spanish context, public participation emerged later than in neighboring countries, and often in a rushed or superficial manner, misunderstood as an end in itself rather than as a means to achieving specific goals. Nonetheless, the integration of participatory processes has brought about changes in planning practices, fostering innovation and leading to the development of new practices and professional profiles among planners. This has not been a smooth path, nor have the results always been remarkable, due to deep-rooted factors (path dependence) that are difficult to overcome. Transforming this dynamic into a process of path creation through social innovation aims to ultimately lead to better spatial and urban planning.

Based on standard classifications of spatial planning styles across Europe, Spain belongs to the group of Mediterranean countries, with a strong land-use planning tradition [

3]. In Spain, spatial and urban planning policies exhibit a clear regulatory bias and are highly institutionalized. The Spanish system is closer to the German tradition of spatial analysis (zoning-based land-use classification) than to the French model, which places greater emphasis on regional economic development and the integration of physical and socio-economic planning. In Spain, this regulatory and non-strategic nature dates back to the “Ley de Ensanche de Poblaciones” (1864) and was definitively consolidated with the first Land Act (“Ley del Suelo”) (1956). This provided the foundation for subsequent regional spatial planning laws in the 1980s and, more significantly, for the new autonomous regions’ urban planning laws in the 1990s. These new laws were necessary following the ruling of the Constitutional Court (STC 61/1997), which established that only the Autonomous Regions—and not the Spanish government—can legislate on spatial planning and urbanism

2.

This regulatory and institutionalized character still remains today, despite the clear influence of European Regional Policy—now Cohesion Policy—with its associated regulations, funding instruments, and tools: Community-Led Local Development (CLLD), Integrated Territorial Investments (ITI), Sustainable Urban Development Strategies (SUDS), later Integrated Territorial Development Strategies, Urban Initiatives, and Urban Agendas, in line with objectives 5.1 and 5.2 of the new 2021–2027 programming period. Unlike Spain’s traditional approach, these initiatives are based on local territorial strategies that integrate public policies and heavily rely on participatory processes involving local stakeholders.

Two types of plans are used to address spatial planning in the Valencian Community. At the municipal level, general urban development plans (planes generales) aim to define the territorial model of a municipality. At a supra-municipal level, Territorial Action Plans (Planes de Acción Territorial, PATs) are used. These PATs can be either integrated or sectoral in nature, both with the same hierarchical status. Integrated PATs are designed to address the three main components of spatial planning, namely, green infrastructure, the settlement system, and the infrastructure system, whereas sectoral PATs focus on specific territories or particular spatial issues. The planning framework has been documented in reports aimed at establishing the state of spatial planning in the territory of the Valencian Community [

4].

2.2. The Fit of Participation in Spanish Planning Practice

Despite all the above, and the enactment of successive participation laws in Spain (since 2006), as well as advances in supra-municipal scales for planning, public participation remains generally limited to formal mechanisms that involve taking part in the administrative processes that lead to the approval of the plan. This is the case with public consultation periods and the submission of objections [

5], and more recently, with public participation during drafting of the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) plan [

6]. In this regard, Spain places excessive emphasis on administrative law to secure legal certainty and legitimacy, which ultimately limits permeability in the relationship between government and citizens

3. This over-reliance on legally established procedures generates rigid participatory processes, only as a preliminary “information” level, according to the OECD Council Recommendation on Open Government [

7].

4The transposition of “Directive 2001/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 June 2001, on the environmental assessment of certain plans and programs” into Spanish law was also conducted in a particular manner. It also followed an administrative procedural approach more typical of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for projects rather than a comprehensive and cross-cutting sustainability vision that would permeate the entire planning process (see

Section 4.2). As a result, this SEA also becomes institutionalized, with two main phases: the definition of the scoping of the Strategic Environmental Report when the plan’s elaboration starts, and the Strategic Environmental Statement that “authorizes” the plan to proceed to its final approval.

Hence, the SEA is seen as a constraining element that complicates planning approval, leading to tendencies to simplify or relax it in order to facilitate interventions. Thus, broadly speaking, the need for participation from the perspective of the institutions and administrative bodies responsible for its implementation is interpreted more as an obligation to comply with a new legal requirement during the spatial plan’s drafting and approval phases than as a facilitating element for better defining and selecting alternatives to agree and decide the final territorial model.

From the viewpoint of the regional and municipal entities that promote, elaborate, and approve the plan, they face a significant issue—a combination and integration of conventional binding regulatory planning with the more innovative strategic territorial planning and its methods. Some planning theories take for granted the possibility of reaching collective agreements to implement selected alternatives [

8], based on [

9]. These are more theoretical than realistic approaches, considering the frequent conflicts driven by competing (often contradictory) interests and power dynamics in the territory [

10,

11] cited in [

12]. As a result, at least in the Spanish case, participation often ends up being not so much a mechanism for negotiation and agreement but, instead, a defensive pressure tactic to either ensure the demands of key actors with real influence or veto power are included in the plan or used as a means to voice the complaints of parties and less influential actors affected by the implementation of the plan.

Therefore, it is essential to introduce pedagogy into participatory processes and the concept of public welfare to help participants understand that there is a common space where all of them can benefit, and to contribute to reaching this, for example, by defining a territorial model using a spatial planning instrument agreed upon by participants.

It is easier to reach a broad consensus on global goals and general principles than on their practical implementation. The former allows for a more strategic and participatory approach. The latter, when transactional agreement is impossible, leads to responsible administrations and governments ultimately defining the range of possible choices and the rules of the game with due legal certainty. This, however, does not prevent—in the worst-case scenario—over-legislation or conflicting laws, which ultimately result in the judicialization of disputes, as is the case in Spain. Conflicts of interest are not resolved solely through scientific evidence but through agreements and, if these are unattainable, through political decisions and, ultimately, court rulings.

The final decision and control over the plan remain with the responsible planning authority. In the case of spatial plans, it is the Regional Government of each of the 17 Spanish Autonomous Regions that is the responsible authority; however, several binding reports from other administrations are needed during the process of obtaining final approval for the plan. When multiple authorities are involved, matters become more complicated due to the need for adequate cross-sectoral and multi-level coordination, which often fails due to the dominance of a siloed, sectoral approach in a Napoleonic-style administration. Add to this the fact that it is not mandatory to elaborate regional and sub-regional spatial plans in Spain (this is only mandatory for municipal urban master plans), when plans are contested, they are usually abandoned before their final approval or, if approved, are not implemented.

2.3. Participation Outcomes

The groups of stakeholders with the greatest veto power are ultimately the ones whose views are truly taken into account, as part of what could be called the “golden ring” of key actors; what is said matters less. This “golden ring” is composed of the responsible authorities or administrations, the economic actors responsible for public and civil works, and, more recently, environmentalist and conservation groups. This issue leads us to the debate on the usefulness of participation, including who participates, how

5 they participate, for what purpose (we assume to approve or help define a shared common spatial vision—for this, a good understanding of procedures and what spatial planning entails is needed for effective participation), and what capacity for real influence do they have (only “input legitimacy” or also “output generation”).

Focusing on the “Who”, we have already established a division between indirect co-decision-makers with significant influence who raise alarm among political leaders due to their ability to block the plans and potentially cause political damage. These include regional governments, municipal governments, construction companies, and environmental groups. This first ring would be followed by a second external ring comprising what we might call active participants, preferably organized, typically those whose interests are most affected by the plan, and who usually adopt a more reactive or preventive approach rather than one aimed at maximizing territorial potential. In a third outer ring are the remaining participants, either organized (preferable for validating the alternative leading to the territorial model proposed by the plan) or individuals.

These overlapping concentric groups, comprising actors from the administration, productive sectors, academia, or civil society, would ideally mix and propose joint options and (transactional) agreements in the participatory process. Some of these stakeholders are recurrent, which opens the debate on the representativeness and legitimacy of participatory processes. Frequent participation improves understanding of the processes and usefulness of both participation and planning

6. The introduction of a civic lottery is a tool that could correct these weaknesses, as it offers impartiality in selecting participants to discuss the territorial issues at hand and provides a representative sample of the society involved.

This brings us to the question of the degrees and objectives of participation (how and for what), and its final level of influence on the decision. From the well-known “ladder of participation” proposed by [

15], various approaches and adaptations to this idea have followed (see [

16]). Here, we highlight two that share common points. On the one hand is [

13], who identifies four phases based on the role participation plays in the decision-making process: public information, listening during the planning process, influencing the decision while seeking consensus, and accepting the decision through conflict resolution and negotiation. On the other hand [

17], bases the objectives of participation and levels of influence on the decision, from which we synthesize the following:

Developing capacities for adequate public involvement: This implies, on the one hand, raising public awareness about planning and participation activities before actors engage, and on the other hand, and more crucially, offering education (training) to prepare people so that they can participate productively. As a preliminary phase, it would not directly influence decision-making; but it can do so indirectly as a result of citizen empowerment [

18] by aligning actors at the planning stage, hence contributing to the development of a new territorial culture (in a ’learning by doing’ process). This territorial intelligence, which [

19] define as a collective intelligence based on the interaction of each individual with their environment and other community members, is necessary not only for decision-makers and institutions but also for civil society, individuals, and economic, social, and intellectual organizations [

20]. This contributes to participation, proposition, and designing future proposals and new reference frameworks that can be considered by political leaders. Collective intelligence also refers to common sensitivity and understanding of what is at stake in one’s own territory and how to facilitate agreements in a collective way to provide efficient solutions for the local community. In the case of low participation culture, such as in the Spanish case, institutionalized public participation activities help to develop this collective understanding and feeling for the common living space [

21,

22]. In this way, institutionalized participation activities help participants to not only learn how to participate, but also why spatial planning is useful.

Generating input: This input can be used by planners to complement or verify official or baseline information with local knowledge (public experiences, attitudes, beliefs), thus contributing to better decisions. This leads us to the relationship between expert and non-expert knowledge, citizen science [

23], post-normal science [

24], and the link between epistemic communities and communities of practice [

25]. If this input is ignored or misunderstood, its influence on decision-making is null. If it is ultimately used for decision-making (even as “input legitimacy”), it may have some influence.

Involving and committing citizens to decision-making, not only in formulating alternatives and designing criteria and methods for their selection, but also in the final decision on the chosen alternatives: What is agreed (consensus on objectives and action commitments to achieve them) will ultimately become normative and binding (as in the action plans of the new Local Urban Agendas [

26]). If implemented, its influence is maximal; if not, the influence returns to zero. Non-implementation is frequent in the Spanish context. Approved instruments are not always developed in practice or, if they are, rarely fully as designed [

27]. In this context, it is essential to move towards a change in the approaches of participatory processes, introducing an unorganized civil society using tools such as a civic lottery that can balance existing forces and prevent the formation of golden rings and decentralize elite power. On the other hand, it is crucial to clearly explain and define the exact margin of bindingness that the proposed measures will have in order to avoid participant disillusionment and unenforceable obligations for decision-makers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Objective

From previous characterization of participation in the Spanish and Valencian context, several questions emerge about how participation occurs in practice: What is its regulatory and procedural framework? What methods or formulas are used? Which actors participate? How are responsibilities distributed? Above all, what are the results? It is important to identify the factors and key issues that affect the quality and outcomes of this participation as a means of evaluation.

The main objective of our research is to use case studies to derive conclusions and recommendations about participatory practices in the study area, considering three types of participation conditions: contextual, procedural, and outcome. The study examines how territorial roundtables are developed in the respective public participation plans in the three selected cases (methods, techniques, and procedures followed). The analysis is based on a series of evaluation indicators (number of participants by PATs and thematic axes, contributions by topics, contributions by types of stakeholders, usefulness of contributions regarding the PAT jurisdictions, alignment of contributions based on the nature and objectives of PATs, external contextual factors) that lead us to the results and, through their discussion, to the development of a series of conclusions and recommendations about how to implement participation and governance actions that improve spatial planning.

3.2. Participation Process Evaluation Indicators

To objectively evaluate the participation activities referred to as “Territorial Roundtables”, we analyze a set of indicators. These also allow us to conduct a comparative analysis of the three plans.

The variables selected to analyze participation activities within the framework of sub-regional spatial plans in the Valencian Autonomous Region are as follows:

Participation balance in thematic roundtables: The convening and attendance at the territorial roundtables are analyzed.

Actor diversity: The roles of different participating actors are examined.

Balance of contributions across each PAT axis: Contributions are studied in relation to the planning instrument’s areas of competence.

Type of contributions: Contributions are classified as informational, reflective, or propositional.

Contributions by actor type: The relationship between actors and types of actions is established.

Alignment of contributions with PAT objectives: An analysis of how proposals can drive the spatial plan is conducted.

Aspects external to the PAT: Potential consequences of contextual conditions present in each PAT are evaluated as factors influencing the results obtained.

The variables developed by the authors of this study correspond to four main factors:

Evaluation of the participatory process itself, with questions such as the following: How have the stakeholders responded to the call for participation?

Factors associated with the methodology of the spatial planning process, which addresses three main areas of action: green infrastructure, settlement system, and infrastructure system. Questions explored include the following: Is there any particular axis in which stakeholders feel more comfortable participating?

Factors reflecting the authors’ concerns about how the contributions relate to the plan. For example, do the suggestions made by stakeholders actually have the potential to be implemented in the plan?

External factors affecting participation: Does the context support or hinder the public participation process?

3.3. Information Sources

The information sources primarily comprise documents generated during the plan drafting process and the in-depth knowledge of the authors of this work, who are members of the drafting team of the three PATs.

3.4. Methodology

To analyze the function and results of the thematic and territorial roundtables, the methodology follows both a quantitative and qualitative approach. In the quantitative approach, measurable aspects obtained objectively during plan development are established, related to the number of attendees, attendance ratio, number of contributions, and so on (see

Section 4). In the qualitative approach, aspects that relate to internal participation factors and external factors are highlighted, allowing us to have a more holistic vision of the process.

4. Analysis of Public Participation Experiences and Results

4.1. The Three PATs Under Analysis

Within the regional framework established by the Valencian Community Spatial Vision approved in January 2011, the Valencian government developed some subregional spatial plans between 2015 and 2023. Only some were approved (all sectoral, none integrated), including PATRICOVA, PATFOR, and, in 2018, PATIVEL and the Huerta PAT. This study analyzes three comprehensive PATs that were meant to define supra-municipal spatial planning: the Alicante–Elche Functional Area (PATAE), the Vega Baja del Segura (PATVB), and the Central Valencian Counties (PATCCCV) (see

Figure 1), which, as of now, have not been approved.

PATCCCV is the largest, encompassing 175 municipalities across eight counties, with an approximate population of 850,000 people. PATVB covers 27 municipalities and contains nearly 360,000 inhabitants. PATAE consists of 21 municipalities with approximately 825,000 inhabitants. Both PATAE and PATVB mainly affect one county each.

All three plans were developed based on the definition of the three traditional types of land that configure the territorial system: green infrastructure models, settlement models, and communication infrastructure models, typical of spatial analysis. A fourth important area of analysis and diagnosis, the socioeconomic model, was added to the studied plans, bringing together economy and land (see

Figure 2).

4.2. Thematic/Content Analysis of Legislation and Case Studies

A PAT follows a long and complex process in which participation is taken into consideration from the start of its drafting

7. The three PATs were developed while the previous 2014 LOTUP, now replaced by Legislative Decree 1/2021, was in force, approving the consolidated text of the Law on Spatial Planning, Urbanism and Landscape, which contains numerous references to public participation.

From a regulatory perspective, according to the 2014 LOTUP, participation was mandatory and binding for certain phases of the plan development process, including the corresponding territorial and environmental assessment procedures; however, nothing was said about the preliminary phase during the drafting of the preliminary version of the plan prior to its initial approval. The phases were as follows (we have underlined steps where the regulations demand participation):

Consultation with public administrations.

Scoping document of the Strategic Environmental and Territorial Report.

Formulation, by the promoting body, of a preliminary version of the plan or program, which will include a Strategic Environmental and Territorial Report.

Submission of the preliminary version of the plan or program, along with the Strategic Environmental and Territorial Report, to initiate the public participation process, public information, and consultations.

Preparation of the plan or program proposal.

Strategic Environmental and Territorial Statement.

If necessary, adaptation of the plan or program to the Strategic Environmental and Territorial Statement.

According to the criteria established in this Law, in cases where modifications are introduced to the plan or program document, new information for citizens is required.

Approval of the plan or program and public exposition.

Implementation of the environmental and territorial monitoring plan following its approval. Compliance with environmental and territorial provisions is verified.

Thus, there are three mandatory phases of consultation and requirements for citizen participation in the planning procedure: 1, 4, and 8. At no time is participation contemplated prior to the drafting of the preliminary version of the plan. Despite the lack of express legal requirement for an ex ante public participation process to support the preparation of the preliminary version of the plan, there is a technical and political will for it during the drafting of the three PATs.

The participation activities analyzed in this study were conducted prior to the public information phase of the PAT:

The objective was to have preliminary versions of the PATs that incorporated the aspirations of the main stakeholders and the general public, thereby reducing potential conflicts and entry barriers. This would streamline the regulated procedures that require submitting the proposed plan to the public for initial approval. All this is performed before proceeding with the development of the mandatory Strategic Environmental Statement and Sectoral Reports. This is followed by obtaining the final (and formal) approval for the plan and its publication in the Official Gazette, making it a binding regulation for planning and individuals.

4.3. Public Participation in the Drafting of the Initial Versions of PATs

A participation plan was designed and developed for each of the three PATs from the beginning of the launch, and initially involved concerned municipalities in each PAT. However, participation was most intensive during the preparation of the initial version of the PAT. This initial version contains the complete PAT documentation, which is binding upon final approval. Approval of the initial version of the PAT is followed by a mandatory public consultation phase, during which interested parties and stakeholders submit comments to revise the plan before the final version is approved.

It is important to note that the number of activities conducted (i.e., the intensity of the participatory process) is directly correlated with the availability of financial resources to support such activities. Between 5 and 10% of the budget allocated for drafting the territorial plans was dedicated to the participation process. The drafting team intended to increase this share beyond 10%; however, given the limited available funding, a participation plan was designed to produce robust results that would enrich the decision-making process.

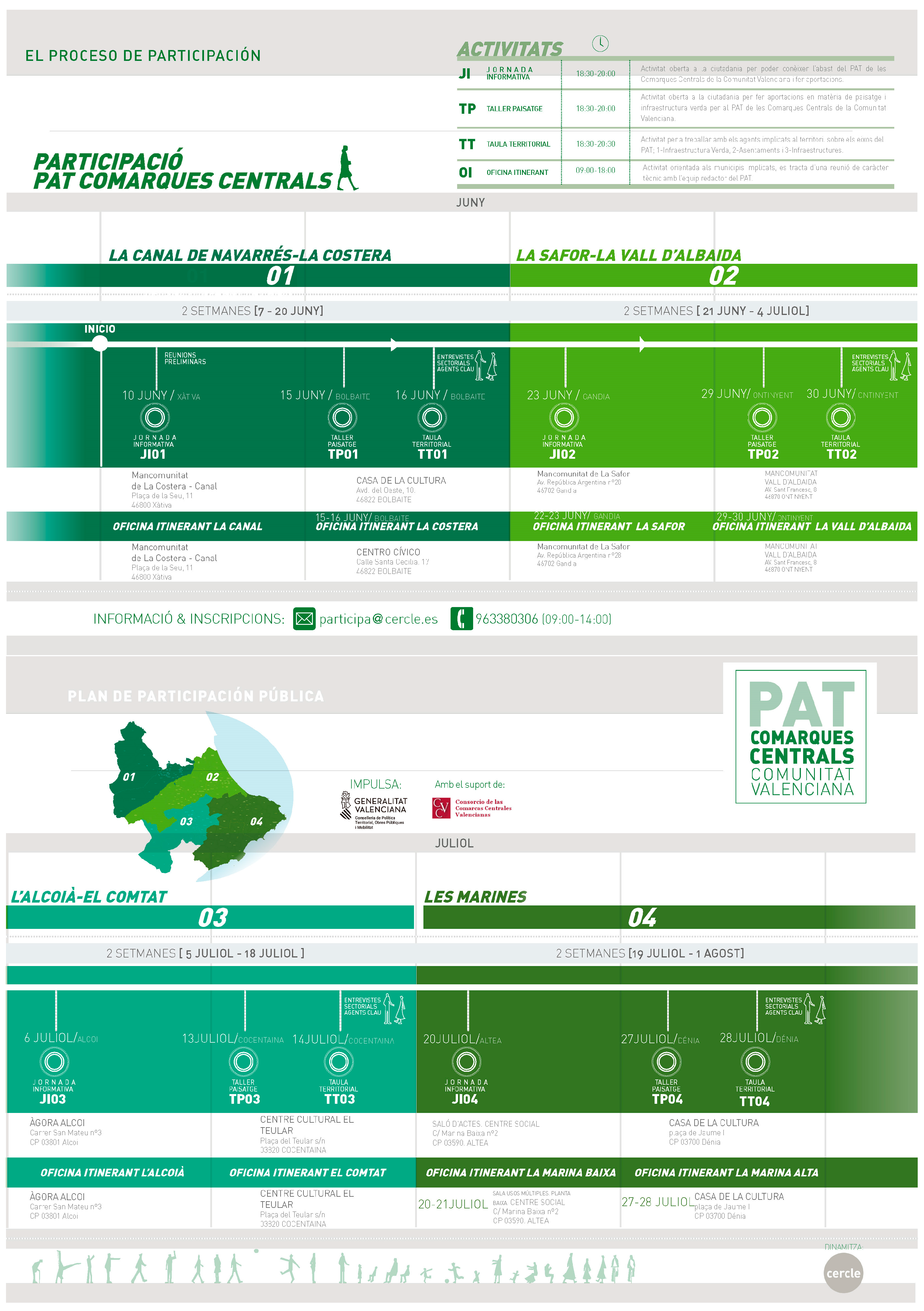

The participatory processes were concentrated within a two-month period, during which all activities were scheduled to maximize the effectiveness of communication efforts and the mobilization of key stakeholders and the general public. In the case of the PATVB, this period was extended due to the COVID-19 pandemic, necessitating an adjustment of the participatory timeline.

Prior to the most intensive phase of participation, a draft of the plan was prepared by the Generalitat Valenciana based on the territorial analyses conducted by the drafting team. For activities such as the territorial workshops described below, the draft plan was shared in the invitation, and the drafting team presented the work conducted up to that point.

The participation process was designed by the drafting team to fill a legal gap at the Spanish state level regarding how public participation should be addressed, specifically for urban and territorial plans. There are no national laws or regulations that specify the types of activities to be carried out or the approach to be followed. This legal gap is filled by guides or manuals, such as the Generalitat Valenciana’s Landscape Studies Guide [

28], which describes how to implement participation in landscape studies that require spatial planning documents.

All participation activities developed during the drafting phase of the initial version of each PAT were carried out in parallel with information sessions, as well as during landscape workshops and territorial roundtables, in order to obtain more robust and reliable results. These activities were as follows (see

Table 1):

Presentation and information sessions: These are meetings open to the general public, during which information about the initial document from which the PAT draft was developed is provided. The presentation session had a more institutional characteristic, while the information sessions had a more local characteristic and were held in different locations within the PAT territory.

Landscape workshops: During these sessions, specific aspects of the population’s relationship with their territory were addressed, including recognition and assessment of landscape units, identification of landscape resources or conflicts, and proposals for territorial requalification.

Territorial or thematic roundtables: This is a discussion forum that addresses the aforementioned three competency axes of the plan, articulating the territorial system. It consists of experts and stakeholders from the territory.

Meetings with municipalities: Once the planning alternatives had been noted, municipal entities participated in bilateral meetings with the PAT technical team to address the urban and territorial issues of each administrative area affected by the future PATs.

Territorial survey: A questionnaire was distributed to collect the general perception of spatial planning in the PAT area in question, analyzing the three axes around which the territorial system was articulated. Additionally, for PATCCCV, since its promoting body was the Intercounty Council (bottom-up) and not the regional administration (as is the case for the others), a survey of economic agents in the said territory, who already had clear prior internal articulation, was conducted (see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Feedback session: In the case of PATVB, a session was held to report the results of the participatory process, explaining how the conclusions from the process had been incorporated into the preliminary version of the proposals for PATVB.

4.4. Participation Period

This section compares the territorial roundtable activities developed in the three PATs from 2018 to 2021, highlighting the relevance of testing the same participation tool developed in the same type of territorial instrument over a 4-year period. The dates of the territorial roundtables are shown in

Table 2.

While the PATAE participatory process proceeded without significant constraints, the PATVB process was affected by COVID-19 restrictions, and the PATCCCV process was influenced by the summer conditions in this Mediterranean area, where intense heat coincides with vacations for most of the population (it was not possible to change dates due to procedural issues and the political agenda).

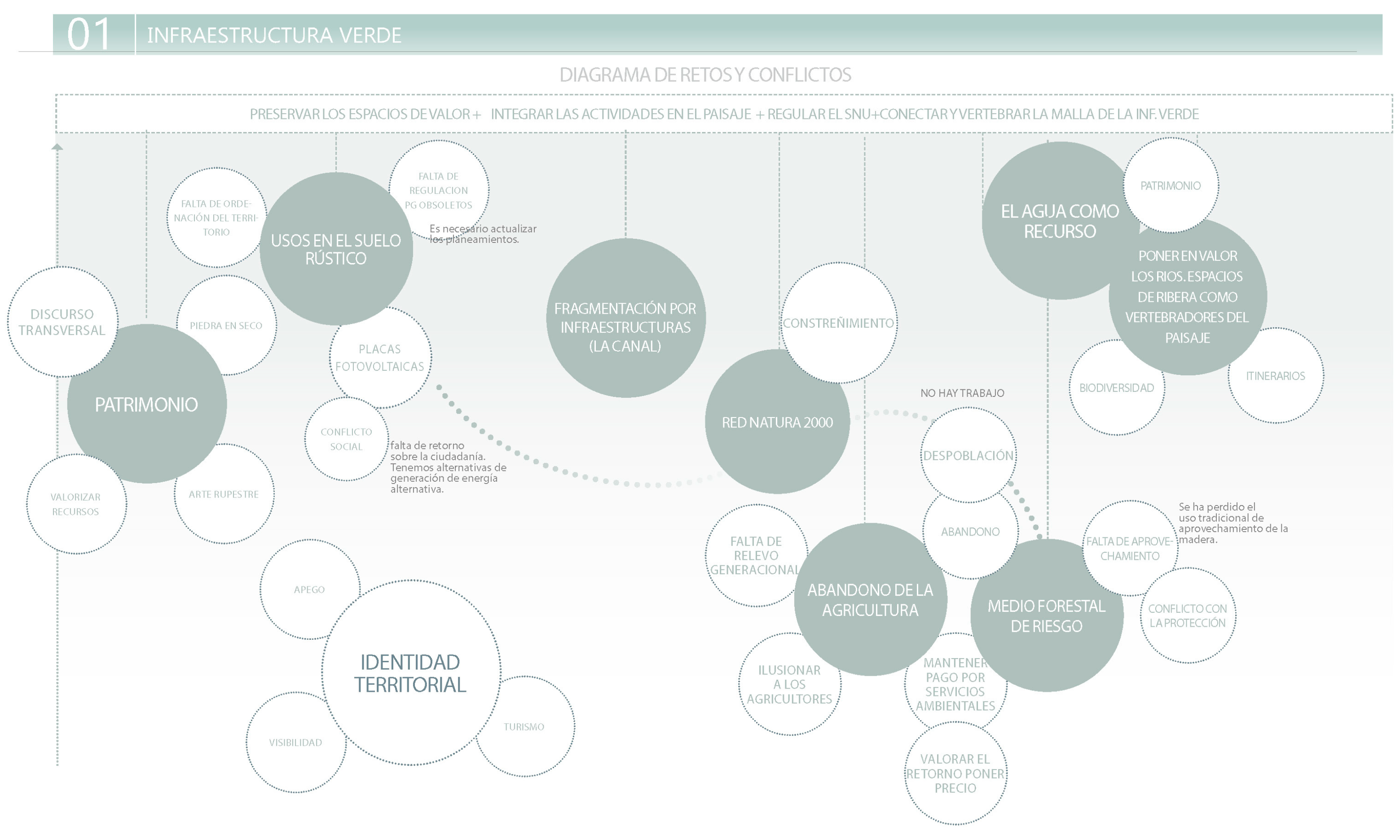

4.5. Participation Topics

The territorial roundtables were held prior to the drafting of the preliminary version of the PATs with the aim of incorporating the visions and contributions made by experts and organized interest groups from the civil society in each of the foundational thematic axes around which the PATs revolved. The planning alternatives were defined as follows:

Green infrastructure and the planning and regulation of rural land.

The settlement system and its orientation.

Analyzing the infrastructure system to improve aspects such as mobility.

Socioeconomic system.

These topics were approached slightly differently in each PAT to adapt the methodology to each specific territory. Due to the coastal position of the study area, the socioeconomic territorial roundtable in PATAE was oriented towards tourism as the main element. In PATVB, however, tourism was addressed more in the settlement roundtable due to the importance of residential tourism in the county. In PATCCCV, the three binding axes of the PAT (green infrastructure, settlements, and communication infrastructure) were addressed simultaneously in all territorial roundtables. In this plan, the socioeconomic axis appeared transversally in the debate when specific contributions were made on topics such as tourism, agriculture, or industry within the corresponding binding axis.

4.6. Call for Sessions

It is important to acknowledge the challenges of convening stakeholders from extensive territorial areas for in-person sessions. This aspect was considered in order to expand the resources and ensure a balanced representation of stakeholder groups in all participation activities.

Invitations were sent via email, convening previously selected stakeholders through a decantation process that involved reviewing previous processes in the same territory, contacting key agents who could provide guidance, and reviewing lists of official entities.

In the first, more theoretical part of this paper, we mentioned the participation “golden ring” of stakeholders. In the analyzed case studies, these were clearly identified as the usual key actors in previous plans: representative administrations at regional, local, and national levels; real estate developers; and environmental groups. However, the proposed participation methodology in the 3 CS aimed to expand this core ring by including additional stakeholders in the area [

29,

30].

The stakeholder groups convened were as follows:

ADMINISTRATIONS: All participants from different political administrative levels with competencies in the issues identified in each territory covered by the PAT.

Spanish: Representatives of governments, hydrographic confederations, and national companies such as Renfe, etc.

Regional: Representatives from relevant regional administration departments with competencies in the different thematic roundtables.

Provincial: Representatives from provincial councils and their associated departments.

County: County associations, as intermunicipal cooperation entities, were considered of high interest.

Municipal: While urbanism technicians from municipalities participated in the territorial roundtables in PATAE, in PATVB and PATCCCV, a clear distinction was made between local administrations and local stakeholders; therefore, while no local-level agents participated in the territorial roundtables in PATVB, local development agents (of great importance in predominantly rural areas) were encouraged to participate in PATCCCV.

ASSOCIATIONS AND NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS: Efforts were made to involve key groups in the spatial planning and management. The following were the main groups:

UNIVERSITIES: Specialists from various universities in the Valencian Community were encouraged to participate.

Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV): Staff from the Valencia, Alcoi, and Gandia campuses were invited. These campuses are located within PATCCCV.

Universitat de València (UV).

Miguel Hernández University of Elche (UMH): Staff from the Elche (PATAE area) and Orihuela (PATVB area) campuses were contacted.

The University of Alicante (UA), which is located in the PATAE area and affiliated with PATCCCV.

All these stakeholder groups received the call inviting them to participate in thematic roundtable meetings. The meetings were conducted in three stages, held over approximately two hours:

LAUNCH: At the beginning of the session, the consulting team provided a brief introduction to the progress of PAT in each thematic axis with the objective of providing more details and the right framework for the session. When participants received the invitation to attend the session via email or phone call, they were encouraged to review the available draft plan document. This draft, along with the introductory talk, set the basis for the debate held during the session.

DEVELOPMENT: Participants present their contributions on the thematic working axis of the sectoral roundtable. Several territorial actors were invited to each session based on the following criteria:

Association with the study area.

Diversity in terms of typology: citizen entities, universities, administrations, etc.

Representation of government levels: state, regional, provincial, or municipal.

Association with each session’s topic/theme.

Representativeness based on gender perspective.

As the facilitator, the consulting team guiding the session collected and categorized all contributions based on their potential to drive the PAT; that is, whether they were consistent with the spatial planning instrument’s capacity to establish binding determinations.

CONCLUSIONS: To close the session, an ideogram developed “just in time” (during the meeting) by the facilitating team was shared with the attendees. It contained the actors’ contributions based on their potential for integration into measures within the PATs’ competency scopes. Similarly, recurrences were identified and possible relationships between contributions were established (see

Figure 6).

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Balance of Participation in Thematic Roundtables and the Addressed Topics

One of the main challenges of any participation process is ensuring that relevant information and input are gathered for the plan. In the case of thematic roundtables, rigorous and in-depth debate on PAT issues was conducted. This is why the sample of stakeholders participating in the roundtable should match the workshop dynamics. The number and attendance ratio (% of invited people) of attendees per session were also analyzed.

First, it should be noted that launching the roundtable call in extensive territories that lack a minimal governance structure requires significant effort. This task must be accompanied by substantial persuasion to overcome the reactivity that many people exhibit towards processes led by the regional administration. This is worse if there have been several previous attempts in the same locations that did not complete the approval process.

Table 3 shows that participation ranged from 6 to 18 people for the set of thematic roundtables, with an average attendance of 13–14 people. For the PATVB roundtables, which were conducted under COVID-19 restrictions, participation was also extended to people who could follow the session via “streaming”.

Regarding the topics addressed, while thematic roundtables were held based on the PAT action axes in PATAE and PATVB, due to the large area covered by the PAT in PATCCCV, the territorial roundtables were held in different counties. In each county, three action axes were chosen based on the areas that the PAT had the competency to address, i.e., green infrastructure, settlement model, and infrastructure model (see

Table 3).

Analyzing the attendance ratios, which enable us to compare the proportion of invited agents versus those who actually attended, shows a significant decrease in PATCCCV, where about 70 involved agents were invited per session. Attendance ranged between 13% and 25% of the total invited persons (see

Table 4).

5.2. Degree of Balance in the Contributions to Each of the Axes

Comprehensive PATs, such as those analyzed in this study, must respond to the thematic axes for which the plan has legal jurisdiction. To this end, participation was designed so that the actors could contribute to the thematic axes that the PATs could influence when defining the spatial model of the entire area.

The results in

Table 5 show that in PATAE and PATVB, the issues represented by the axes were more balanced, highlighting infrastructure for PATAE and socioeconomic factors for PATVB, where agriculture and tourism are relevant factors. In PATCCCV, which has extensive territories with significant rural components, the proposals focused on the first block of green infrastructure, with suggestions to address issues such as agricultural landscapes, forest areas, and river corridors. It is striking how little attention was paid to socioeconomic aspects, despite the region being a territory with good internal articulation (with previous initiatives of interest such as the CONCERCOST Project, in the framework of the EU TERRA Programme in 1996) and having its own credit institutions (e.g., Caixa Ontinyent and Caixa Popular). However, it should be noted that those promoting the formulation of the PAT for this area were in the Steering Committee of the Consortium of Central Valencian Counties, where the main socioeconomic actors are represented.

5.3. Contributions by Type of Actors

The same actor typologies participated in the three PATs, with minor differences. While members of the municipal urbanism technical team (who had already participated ex ante in bilateral meetings with the planning team when the PAT was launched by the Valencian regional government) were invited to attend the thematic roundtables in PATAE, participants in the working roundtables in PATVB were political officials. This is because the PAT roundtables in PATVB coincided with the development of a Strategic Climate Change Adaptation Plan promoted by the Valencian Government Presidency (Plan Renhace). The political and budgetary involvement of the Valencian Government in the execution of planned actions, together with the development of a multilevel governance model where all administrations could participate, was a catalyst for the involvement of actors who do not usually participate.

The stakeholders who participated in the territorial and sectoral roundtables belonged to the following groups:

Civil society: Understood to be the group of individuals who, in their own right, have the political status of Valencian citizenship or reside in the planning area. Within this category are also citizen entities or associations whose scope of action occurs within the PATs’ thematic axes. Civil society can be organized, forming part of a collective with its own autonomy that does not originate from the institutions of the State, or operate individually as private citizens.

Academia: Universities and research centers with experts in the different subject areas of action.

Economic actors: Business people and developers whose scope of action corresponds to or affects the territory covered by the PAT.

Administration: Includes technicians from different political administrative levels, such as state, regional, provincial, or municipal. Only the second and fourth levels made contributions during the roundtables.

Professional associations: Concerned with or able to provide information on any of the contents or thematic axes in each PAT.

Similarities and differences are observed in the participation patterns (see

Table 6). Organized civil society played a very active role in all three PATs, while unorganized civil society was less involved. Local administration technicians made the highest number of contributions in PATAE. A high level of contributions from the economic sector was also observed in PATVB and PATCCCV.

The lack of contribution from administrations or entities at the county and provincial levels is noteworthy. Analysis of entities at the regional and national levels showed that members of the Valencian Government from departments other than the one promoting the PAT participated only in PATVB, specifically in a territorial area that had suffered flooding from the September 2019 DANA and where the Vega Baja Regeneration Plan (Plan Vega Renhace) had been launched.

5.4. Type of Contributions

The contributions made by different actors were classified into three categories:

• Informative: Providing data to enhance knowledge of the territory or specific problems, aiding in analysis and diagnosis.

• Reflective: Questioning certain aspects of the PAT’s scope and initiating debate as a catalyst for reviewing diagnoses and proposals.

• Propositional: Proactive and concrete proposals that stakeholders wanted to be included in the PAT.

Comparison of the data in

Table 7 shows that while informational contributions stood out in PATAE, in PATVB, actors made more propositional suggestions, potentially motivated by prior experience and preparation of the aforementioned Plan Vega Rehance and its corresponding action plan, which had been launched previously; in fact, many proposals were identical to those raised during Plan Vega Renhace. In PATCCCV, reflective and propositional contributions outweighed informative contributions. It should be noted that in this PAT, which had more condensed sessions, more propositional contributions were encouraged, probably due, again, to the territory’s own articulation and prior experiences.

5.5. Level of Alignment of Contributions with the PATs’ Nature and Objectives

Contributions were classified based on their potential to drive the PAT; that is, the extent to which they aligned with the PATs’ objectives and whether they could be developed consistently based on the PATs’ potential to establish binding determinations for urban planning and other derived planning that must be developed by municipalities and sectors. The following categories were considered:

- A.

Dissent: These aspects are contrary to the PAT’s objectives, making their integration impossible.

- B.

Low potential to drive the PAT: This category includes contributions that, due to the scale of the PAT or legal jurisdictions, can influence the PAT only indirectly, and therefore have very limited scope.

- C.

Medium potential to drive the PAT: Aspects that could be integrated into the plan. Often, these are contributions referring to instruments or plans of a more limited scale.

- D.

High potential to drive the PAT: These are considerations that are fully aligned with the PAT’s objectives and can be incorporated into urban planning.

- E.

Exceeds the PAT’s competency scope: These include proposals that fall outside the corresponding PAT’s reach.

Comparative analysis of these data showed how the debate framework was understood by the stakeholders (see

Table 8). Sometimes contributions cannot drive the PAT; therefore, the team responsible for the participation plan during these stages of plan development, prior to initial approval, where participation is not mandatory, needs to sift through the information to identify proposals that can be integrated into and ultimately improve the PAT in order to better define the desired spatial model for the area for which the plan is being developed.

More than 60% of the total contributions had the potential to drive the PAT, indicating the usefulness of the participation tasks. Up to 20% of the contributions exceeded the PATs’ competency scope, while only 3% contradicted the PATs’ objectives. This indicates the extent to which clearer information and better training on how to effectively participate in these sessions, and on why spatial planning is needed, should be provided in the future.

Examining the figures for each of the three PATs shows that PATAE had no contributions contrary to the objectives set at the start of the session; however, up to 35% of suggestions had little potential to be included in the PAT document as it is a spatial rather than an urban instrument (in this case, the participation of municipal urbanism technicians was prevalent).

In PATVB, some stakeholders made contributions that were contrary to the plan’s objectives; additionally, 24% of the suggestions exceeded the PAT’s competencies. Here, over 30% of issues raised could be implemented in this sub-regional spatial plan. One action proposed during the Strategic Plan Vega Renhace was to approve PATVB. This may explain why some stakeholders saw PATVB as an opportunity to reiterate similar measures suggested during the review of the Renhace Plan, despite them clearly being different planning instruments. Again, clearer information and better training on spatial planning are needed.

In PATCCCV, over 40% of suggestions had high potential to drive the PAT and could therefore be implemented. If we add medium-potential contributions, the figure increases to nearly 70%, making this the PAT for which stakeholder participation proved most fruitful, and which can be positively associated with the PAT’s promoting body being the Central Counties Consortium itself (bottom-up sense), which had prior experience with this objective.

5.6. External Contextual Factors Influencing PAT Participation and Outcomes

Every participation process is influenced by the territorial and temporal context in which it occurs. This allows for a better comparison of citizen and stakeholder involvement in each PAT (see

Table 9). Therefore, this section qualitatively evaluates some aspects associated with the participation context, distilled from reflections by the three authors who were members of the PATs’ planning team. This complements the previous quantitative analyses.

One factor that enriches the participation process and gives it more depth is having recently conducted similar work (not a large time lag). Plan Renhace had involved working with territorial stakeholders the year before as part of prioritizing actions to be launched in Vega Baja county after the 2019 floods; conversely, in some cases, certain actors used the same conceptual framework of contribution, diminishing the activity’s effectiveness, as shown above.

Robust results are achieved, among other reasons, by deploying different complementary participation activities. The intensities of activities for the three PATs were comparable; however, PATCCCV is a very large area (covering eight counties in the Valencian Autonomous Region), and bringing together actors from all counties was a significant logistical challenge.

PATVB was undertaken during a time when significant COVID-19 restrictions were still in place, and public information sessions could not be held prior to the thematic roundtables. Additionally, the pandemic made participation in the roundtables more difficult as it was harder to separate the participants from the pandemic’s impact such that they could focus on the tasks in the sessions.

An interesting aspect to consider is whether there are emerging processes in the territory that drive participation and reinforce the PAT. This was the case, for example, in the open debate on how photovoltaic energy should be implemented in the territory, given the current energy transition. While plans were being drafted in PATCCCV and PATVB, conflicts emerged between social groups and solar plant developers. This reinforced the recognition of the usefulness of such supra-municipal instruments to regulate this activity.

Another key issue driving participation in PATCCV was the CV60 extension project in La Safor County. CV60 is a highway that—while considered necessary by several authors—generated significant controversy by fragmenting an agricultural landscape with high cultural value. This topic attracted interested people to actively participate, and many contributions were collected through various activities on this topic.

Environmental risk perception by the population was also a relevant factor for participants. The 2019 DANA floods in Vega Baja, particularly in PATVB, and the forest fire risk in PATCCCV generated considerable interest among the participating actors, motivating them to contribute to the development of the PAT draft.

The governance framework has proven crucial for the proper functioning of the participatory process. While PATCCCV had a coordination body that became involved in the participation process itself and encouraged participation among territorial actors, the lack of political alignment in PATVB and PATAE, as well as differences between municipal governments and the regional administration, made the process more difficult and may even block it (as in PATAE).

6. Conclusions

As a main conclusion, participation in PATs—although regulated—can be beneficial and effective, both procedurally and substantively. The plans’ content helps to better define the desired spatial model from the substantive point of view, while from the procedural point of view, it reduces barriers and streamlines processes. Obtaining approval for the plan is easier when conflicts and barriers to implementation are reduced; thus, conducting and improving participation during all stages of the plan elaboration process, both mandatory and voluntary (e.g., before the plan’s initial approval), are useful in terms of obtaining input and promoting the plan.

Regarding the relationship between the resources employed to convene stakeholders and the final participation ratios, it should be emphasized that participation in places lacking a previous participatory culture requires additional effort. These efforts can sometimes exceed the resources allocated for the plan’s development; for this reason, it is crucial to use ICT and optimize the method of participant selection to improve efficiency. If the covered area is extensive, then the challenge is bigger. In this regard, it is worth considering the need for greater involvement in communicating the plan itself and in generating sustained participation structures that can catalyze governance processes. Sometimes these structures already exist; as in the case of PATCCCV where, although this advantage was not observed in the participation ratios, it was key in dynamizing the process.

Although material resources may be constrained, participation can be increased by investing time in preparatory training sessions that emphasize the PAT’s competencies and legal jurisdictions, provide information on how to participate, explain how stakeholders’ proposals can be taken into account, and inform participants on why, when, and how they can ask for feasible transactions. It is all about introducing and establishing a territorial culture among citizens so that they clearly understand how they can contribute, as well as how these spatial planning instruments influence their daily lives.

Analyses of contributions by type of stakeholder and PAT thematic axes showed that civil society has significant weight in green infrastructure proposals. At the sub-regional level, green infrastructure is seen as a landscape and culturally important territory. Agricultural landscapes, heritage sites, and landscape resources are referred to in this section more frequently than other items related to territory connectivity or ecosystem service provision, which are more typical of green infrastructure but are more alien to the actors involved. Although economic actors had an uneven presence in the PATs, they are key to addressing the relationship between territory and economic activity. These actors’ contributions often focus on infrastructure and economic activities; however, contributions related to settlements have been more distributed among groups of stakeholders when making proposals. Despite this evidence on the target of the agents involved and their “own” topics, it is necessary to investigate ways of encouraging the agents to step out of their comfort zones, as well as to confront scenarios regarding thematic axes that are not included in their initial aspirations.

Analysis of stakeholders’ understanding of the true meaning and scope of participation revealed that less than a quarter of the contributions exceeded the scope of the PAT or went against the objectives set out in the draft document. On the other hand, more than 55% of the contributions fit within the PAT’s scope and could support actions for which the PAT had the authority to propose management measures and alternatives. The debate among the stakeholders involved was fluid and resulted in a set of measures that could be implemented in a land use planning instrument of this nature. The ability of the proposals to drive the plan makes the participation process more efficient. Allowing room for maneuvering in the areas of discussion should be a primary objective in participation plans.

Participation can be greatly affected by contingencies and contextual conditions in complex processes, such as the development and approval of spatial planning instruments. An extraordinary event, such as a pandemic, can make a participatory process extremely difficult. Conversely, unforeseen circumstances may arise that can become catalysts for participation, if the involved stakeholders recognize that the planning tool can help mediate and advance the resolution of a conflict. However, these temporal hot topics (e.g., infrastructure construction and the proliferation of photovoltaic installations that have a significant impact on the territory) can capture the attention of the stakeholders during the debate and distract from the holistic vision. Overall, it is important to manage contingencies for the benefit of the planning process and avoid placing planning at the service of contingencies.

The relatively low level of conflict encountered when deciding the territorial model that the plan should propose in the participatory spaces developed in this non-mandatory phase contrasts with the strong opposition that plans face during the public disclosure phase (mandatory and binding). Certainly, more hegemonic actors avoid participating in these phases in order to influence the plan through other means, such as resorting to the courts and the judicialization of differences and conflicts. However, non-participation in these cases should be considered an indicator of a lack of willingness to engage in prior conciliation when the courts are required to issue a ruling (for instance, as already happens in labor laws, where attendance of pre-trial conciliation is binding), thus strengthening the already proven usefulness of such participation.

Finally, it is important to note that the plans were made during the participation process. In fact, before the roundtables, the only document shared with stakeholders was a draft version, which was very synthetic. The PAT is not modified by participation; it is derived from it and inspired by the pool of suggestions. Only one of the three PATs could follow the administration process, the PAT of Vega Baja, and none of them are approved at this moment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.-D. and P.L.-G.; methodology, J.F.-D., I.D.-T. and P.L.-G.; validation, J.F.-D., I.D.-T. and P.L.-G.; formal analysis, J.F.-D. and I.D.-T.; investigation, J.F.-D., I.D.-T. and P.L.-G.; resources, J.F.-D., I.D.-T. and P.L.-G.; data curation, P.L.-G. and I.D.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.-D., I.D.-T. and P.L.-G.; writing—review and editing, J.F.-D. and I.D.-T.; visualization, I.D.-T.; supervision, J.F.-D.; project administration, J.F.-D. and I.D.-T.; funding acquisition, J.F.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is part of the Spanish research project “Propuesta de diseño institucional y comunitario para una ordenación del territorio integral en la transición hacia una economía sostenible” (GOBEFTER-III), reference PID2021-128356NB-I00, financed by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This is the name for Subregional Spatial Plans in the Valencian Autonomous Region. In Spain, according to Article 148 of the Spanish Constitution (1978), the elaboration and approval of spatial plans is exclusively in the hands of Regional (Autonomous) Governments. |

| 2 | For an overview of the current situation regarding spatial planning instruments and legislation in all 17 Autonomous Regions of Spain, see [ 4]. |

| 3 | These relationships are ensured and regulated by Law 39/2015, of October 1, on the Common Administrative Procedure of Public Administrations. |

| 4 | This is an initial level of participation characterized by a unilateral relationship in which the government produces and delivers information to citizens and stakeholders. It includes proactive measures to disseminate information, but there is no real feedback between the administration and the administered, as could occur during consultation or at active participation levels. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | This does not usually happen, explaining why the demands and proposals raised in many participatory processes often have little to do with what the plan can or cannot do. |

| 7 | This is in accordance with the aforementioned Directive 2001/42/EC, transposed into Spanish law through Law 6/2001, of May 8 (currently Law 21/2013, of December 9, on environmental assessment), followed by various Spanish and Valencian Community public participation laws (Law 11/2008, of July 3, now repealed by the current LLEI 4/2023, of April 13, of Generalitat, on Citizen Participation and Promotion of Associative Life in the Valencian Autonomous Region). |

References

- Beunen, R.; Duineveld, M.; van Assche, K.A.M. Evolutionary Governance Theory and the Adaptive Capacity of the Dutch Planning System. In En Spatial Planning in a Complex Unpredictable World of Change: Towards a Proactive co-Evolutionary Type of Planning Within the Eurodelta; InPlanning: Driebergen-Rijsenburg, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinós, J. Gobernanza: Refinando significados desde el debate teórico pensando en la práctica. Un intento de aproximación fronética. Desenvolv. Reg. Em Debate 2015, 5, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy: The EU Compendium of Spatial Planning Systems and Policies; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 1997; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/059fcedf-d453-4d0d-af36-6f7126698556 (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Dasí Farinós, J. Marco Legal y Procedimental de la Ordenación del Territorio en España: Diagnóstico y Balance; Thomson Reuters-Aranzadi: Navarra, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lloret, P.; Farinós, J. La Dimensión Participativa en el Diseño de Políticas Urbanas. El Caso Valenciano; Gestión y Análisis de Políticas Públicas: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Volume 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenar-Muñoz, M.; Antequera-Terroso, E. Acerca del procedimiento de evaluación ambiental estratégica y la incardinación de la salud en el proceso de elaboración de los planes. In Marco Legal y Procedimental de la Ordenación del Territorio en ESPAÑA, Diagnóstico y Balance; Farinós, J., Peiró, E., Farinós, J., Eds.; Thomson Reuters Aranzadi: Navarra, Spain, 2020; pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- OCDE. Recomendación del Consejo Sobre Gobierno Abierto. 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/open-government/recomendacion-sobre-gobierno-abierto.htm (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning; Macmillan Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action; Thomas, M., Ed.; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Phronetic planning research: Theoretical and methodological reflections. Plan. Theory Pract. 2004, 5, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The ethic of care for the self as a practice of freedom. In The Final Foucault; Bernauer, J., Rasmussen, D., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988; pp. 112–131. [Google Scholar]

- Farinós, J.; Vera, O. Planificación territorial frenética y ética práctica. Acortando las distancias entre plan y poder (política). Finisterra Rev. Port. De Geografía 2016, 51, 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, J.L. The Public Participation Handbook: Making Better Decisions Through Citizen Involvement; Jossey-Bass: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Latasa, I.; Lloret, P. Técnicas de Participación Pública. Ordenación del Territorio y Medio Ambiente; Farinós, J., Olcina, J., Eds.; Tirant Humanidades: Valencia, Spain, 2022; pp. 553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Martín, P. Las Alas de Leo. La Participación Ciudadana del Siglo XX. Asociación Kyopol—Ciudad Simbiótica. 2010. Available online: https://libros.metabiblioteca.org/bitstreams/a74bdfe5-62cf-490d-9e86-2fb2627b15c9/download (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Miskowiak, D. Crafting an Effective Plan for Public Participation; Center for Land Use Education, University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point: Stevens Point, WI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Turnhout, E.; Van Bommel, S.; Aarts, N. How participation creates citizens: Participatory governance as performative practice. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/157421 (accessed on 29 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Farinós, J. Bases conceptuales de la gestión territorial: Inteligencia territorial y ética práctica. In Observatorios Territoriales Para el Desarrollo y la Sustentabilidad de los Territorios. Vol. 1: Marco Conceptual y Metodológico; Cittadini, E., Vitale, J., Eds.; Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria: Mendoza-San Juan, Argentina, 2017; pp. 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Neffati, H.; Girardot, J.-J. L’intelligence Territoriale, un Concept Émergent. Les Cahiers d’Administration, Hors-Série de la Revue Administration (Supplément au nº243), Collection Territoires Pour Demain. 2014. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01146237 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Quaglia, A.; Guimaraes Pereira, Â. Engaging with Food, People and Places; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC121910 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Turnhout, E.; Metze, T.; Wyborn, C.; Klenk, N.; Louder, E. The politics of co-production: Participation, power, and transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, H.; Scott, P.; Gibbons, M. Re-Thinking Science. Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Funtowicz, S.; Ravetz, J. Science for the post-normal age. Futures 1993, 25, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, J.R.; Pitxer, J.V.; Farinós, J. Marco general y narrativas predominantes que explican la forma en que se desarrollan los procesos: Una aproximación a la OT en España y las posibilidades de su conexión con la política del desarrollo económico regional. In Evaluación de Procesos: Una Mirada Crítica y Propositiva de la Situación de la Política e Instrumentos de Ordenación del Territorio en España; Farinós, J., Peiró, E., Rando, E., Eds.; Thomson Reuters Aranzadi: Navarra, Spain, 2021; pp. 45–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Partal, S. Los Planes de Acción Local de la Agenda Urbana Española: Su papel en el urbanismo del siglo XXI. Ciudad. Y Territorio. Estud. Territ. 2023, 55, 829–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinós, J. Presentación. Tratando de aproximar la teoría procedimental, con-textual y sustantiva de la planificación. In Evaluación de Procesos: Una Mirada Crítica y Propositiva de la Situación de la Política e Instrumentos de Ordenación del Territorio en España; Farinós, J., Peiró, E., Rando, E., Eds.; Thomson Reuters Aranzadi: Navarra, Spain, 2021; pp. 17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Criado, A.M. Guía Metodológica: Estudios de Paisaje; Generalitat Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbio, L. Designing effective public participation. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, J.; Kearnes, M. Remaking Participation: Science, Environment and Emergent Publics; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Territorial scopes of the three territorial action plans. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 1.

Territorial scopes of the three territorial action plans. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 2.

Competency axes and/or analysis–diagnosis axes of the three analyzed PATs: 01, green infrastructure; 02, settlement system; 03, infrastructures of mobility; 04, socioeconomic system. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 2.

Competency axes and/or analysis–diagnosis axes of the three analyzed PATs: 01, green infrastructure; 02, settlement system; 03, infrastructures of mobility; 04, socioeconomic system. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 3.

Initial phases of PAT drafting and integration of participation. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 3.

Initial phases of PAT drafting and integration of participation. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 4.

A set of activities developed for the four county groups during the drafting of the initial version of the Territorial Action Plan for the Central Valencian Counties (PATCCV). The activity schedule sequentially covers the entire territorial scope of the plan. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 4.

A set of activities developed for the four county groups during the drafting of the initial version of the Territorial Action Plan for the Central Valencian Counties (PATCCV). The activity schedule sequentially covers the entire territorial scope of the plan. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 5.

Images of the deployment of activities developed for the eight counties involved in the Territorial Action Plan for the Central Valencian Counties (PATCCV). Source: own elaboration.

Figure 5.

Images of the deployment of activities developed for the eight counties involved in the Territorial Action Plan for the Central Valencian Counties (PATCCV). Source: own elaboration.

Figure 6.

Example of a feedback ideogram developed within the framework of drafting the initial version of the PAT for PATCCCV at the Bolbaite territorial roundtable in June 2021. The contributions in the upper part of the panel are actions with greater potential to drive the PAT. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 6.

Example of a feedback ideogram developed within the framework of drafting the initial version of the PAT for PATCCCV at the Bolbaite territorial roundtable in June 2021. The contributions in the upper part of the panel are actions with greater potential to drive the PAT. Source: own elaboration.

Table 1.

Participation activities conducted during the drafting of the initial version of the three PATs. PS, presentation sessions; IS, information sessions; LW, landscape workshops; MT, territorial roundtables; MM, meetings with municipalities; FS, feedback sessions. Source: own elaboration.

Table 1.

Participation activities conducted during the drafting of the initial version of the three PATs. PS, presentation sessions; IS, information sessions; LW, landscape workshops; MT, territorial roundtables; MM, meetings with municipalities; FS, feedback sessions. Source: own elaboration.

| NUMBER OF PARTICIPATION ACTIVITIES |

| | PS | IS | LW | TR | MM | FS |

| PATAE | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 21 | 0 |

| PATVB | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 23 | 4 |

| PATCCCV | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 49 | 0 |

Table 2.

Dates on which participation activities were developed. Source: own elaboration.

Table 2.

Dates on which participation activities were developed. Source: own elaboration.

| | PERIOD OF REALIZATION OF PARTICIPATION ACTIVITIES |

| PATAE | May to June 2018 |

| PATVB | November to December 2020 |

| PATCCCV | June to July 2021 |

Table 3.

Attendance at each of the territorial roundtables. Source: own elaboration.

Table 3.

Attendance at each of the territorial roundtables. Source: own elaboration.

| ATTENDEES AT EACH OF THE TERRITORIAL ROUNDTABLES. |

| | GREEN INF. | SETTLEMENTS | INFRASTRACTURE | SOCIOECONOMIC |

| PATAE | 18 | 9 | 16 | 6 |

| PATVB | 12 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| PATCCV | MT1 BOLBAITE | MT2 ONTINYENT | MT3 COCENTAINA | MT4 DENIA |

| 17 | 17 | 13 | 15 |

Table 4.

Attendance ratio per territorial roundtable. Source: own elaboration.

Table 4.

Attendance ratio per territorial roundtable. Source: own elaboration.

| ATTENDANCE RATIO FOR EACH TERRITORIAL ROUNDTABLE. |

| | GREEN INF. | SETTLEMENTS | INFRASTRACTURE | SOCIOECONOMIC |

| PATAE | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.22 |

| PATVB | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.33 |

| PATCCCV | MT1 BOLBAITE | MT2 ONTINYENT | MT3 COCENTAINA | MT4 DENIA |

| 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

Table 5.

Percentage of contributions to each PAT based on thematic axis. Source: own elaboration.

Table 5.

Percentage of contributions to each PAT based on thematic axis. Source: own elaboration.

| % CONTRIBUTIONS RECEIVED BY MAIN LINE OF ACTION |

| | GREEN INFRAST. | SETTLEMENTS | INFRASTUCTURE | SOCIOECONOMIC |

| PATAE | 25.73 | 19.30 | 33.33 | 21.64 |

| PATVB | 27.2 | 20.08 | 19.67 | 33.05 |

| PATCCCV | 46.61 | 22.03 | 22.03 | 9.3 |

Table 6.

Percentage of total contributions based on actor groups: 01, civil society; 02, academia; 03, economic actors; 04.1, regional administration; 04.02, municipal administration; 05, professional associations. Source: own elaboration.

Table 6.

Percentage of total contributions based on actor groups: 01, civil society; 02, academia; 03, economic actors; 04.1, regional administration; 04.02, municipal administration; 05, professional associations. Source: own elaboration.

| PERCENTAGE OF CONTRIBUTION BASED ON TYPE OF STAKEHOLDER. | | | |

| | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04.01 | 04.02 | 05 |

| PATAE | 26.19 | 7.14 | 4.76 | 23.81 | 35.71 | 2.38 |

| PATVB | 39.75 | 18.83 | 26.78 | 0.84 | 2.93 | 2.09 |

| PATCCCV | 43.22 | 5.93 | 27.96 | 0 | 12.71 | 10.16 |

Table 7.

Types of contributions. Source: own elaboration.

Table 7.

Types of contributions. Source: own elaboration.

| PERCENTAGE OF THE TYPES OF CONTRIBUTIONS. | |

| | INFORMATIVE | REFLECTIVE | PROACTIVE |

| PATAE | 45.02 | 30.41 | 24.56 |

| PATVB | 17.57 | 25.94 | 56.49 |

| PATCCCV | 18.03 | 47.54 | 34.42 |

Table 8.

Percentages of contributions and their alignment with PAT objectives: (A) dissent; (B) low potential to drive the PAT; (C) medium potential to drive the PAT; (D) high potential to drive the PAT; (E) exceeds the PAT’s competency scope. Source: own elaboration.

Table 8.

Percentages of contributions and their alignment with PAT objectives: (A) dissent; (B) low potential to drive the PAT; (C) medium potential to drive the PAT; (D) high potential to drive the PAT; (E) exceeds the PAT’s competency scope. Source: own elaboration.

| PERCENTAGES OF CONTRIBUTIONS AND THEIR ALIGNMENT WITH PAT OBJECTIVES |

| | A | B | C | D | E |

| PATAE | 0 | 35 | 40 | 22.5 | 2.5 |

| PATVB | 6.32 | 13.68 | 28.42 | 27.37 | 24.21 |

| PATCCCV | 0 | 28.66 | 22.13 | 42.62 | 6.5 |

| TODOS | 3.19 | 15.96 | 30.32 | 30.85 | 19.68 |

Table 9.