1. Introduction

El Malpais National Monument in northern New Mexico, USA, is a distinctive geologic landscape with profound cultural significance (

Figure 1). The name El Malpais, Spanish for “the badlands,” aptly describes its rugged terrain characterized by extensive ancient lava flows, cinder cones, ice caves, and lava tubes, predominantly composed of black basalt. These features are remnants of a prolonged volcanic history that lasted roughly 700,000 years, marking one of the longest volcanic sequences in the United States [

1]. The McCartys lava flow is the most recent formation within this sequence, dating back approximately 3900 to 3200 years ago [

2].

Initially, the area’s harsh beauty might suggest an absence of life or human interaction; however, El Malpais is deeply embedded in the spiritual and cultural heritage of multiple Native American groups, including the Acoma, Zuni, Laguna, and Navajo. These communities have inhabited the area for countless generations, viewing it as a sacred part of their ancestral homeland, integrally woven into their cosmology, oral traditions, and daily lives [

3].

This area constitutes a landscape in Summerfield’s sense: a dynamic, historically layered configuration of the Earth’s surface shaped by both past and present geomorphic processes [

4]. Such landscapes result from surface and subsurface geological processes unfolding over geological time, situated at the intersection of Earth systems—including the lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere—emerging through complex, interacting forces [

4]. Simultaneously, the landscape embodies the entanglement of culture and nature, as human practices, meanings, and experiences are closely tied to the geological features.

This article examines landscape not only from an Earth sciences perspective but through the integration of geological features and cultural practices, here referred to as a

cultural landscape. The term is interpreted in alignment with Tim Ingold’s concept of the taskscape, which emphasizes the interrelation of lived activities and environmental features [

5]. Ingold notes that just as a landscape comprises related physical features, a taskscape comprises related activities, highlighting the temporal and social dimensions of human engagement with the environment: “Just as the landscape is an array of related features, so—by analogy—the taskscape is an array of related activities” [

5] (p. 158). Accordingly, the term cultural landscape highlights the interconnectedness of geosites and cultural practices, drawing attention to how landscapes are lived in, worked with, and imbued with meaning through ongoing relations between people and the geological features of the landscape.

Informed by previous scholarly work [

6,

7,

8], we refer to this cultural landscape as

sacred, highlighting that it is a place perceived as imbued with spiritual significance, wherein cultural practices, beliefs, rituals, memories, and ancestral histories converge, marking these areas as repositories of identity, community cohesion, and cosmological meaning. The sacredness attributed to landscapes emerges from dynamic relationships between human communities and their environments, involving reciprocal interactions, traditional ecological knowledge, and lived experiences through which space becomes spiritually charged and socially significant.

El Malpais provides an example of how a cultural landscape is interwoven with cosmology, oral history, and lived experiences. This paper contributes to the research discourse on geoheritage and geosites [

9,

10,

11] by showing how El Malpais National Monument, in connection with its surrounding landscapes, is understood and interpreted by native American tribes as an interconnected landscape of cultural significance. It is based on current ethnographic studies as well as literature studies inquiring into the interrelationship between culture and landscapes. By referencing the traditions of several Native American tribal groups in this paper, the point is to show that one volcanic landscape is a significant landscape in the origin accounts of several tribes, showing both similarities and differences in their understandings and interpretations.

The explicit aim of this research paper is to document and analyze how geological features within the volcanic landscape of El Malpais National Monument in New Mexico are integrally embedded in the cultural cosmologies, narratives, and ritual practices of Indigenous communities, particularly the Acoma, Zuni, Laguna, and Navajo tribes. Through ethnographic fieldwork and a literature review, the study seeks to illustrate the dynamic interactions between geology and culture, positioning El Malpais as a cultural landscape that informs broader discussions on the interconnectedness of geoheritage and intangible cultural heritage. To situate the discussion on the landscape of El Malpais, the paper seeks to explore the relationship between geology and culture more broadly. Around the world, distinctive geological features—from mountains and volcanoes to caves and monolithic rocks—have become deeply embedded in cultural beliefs, origin accounts, and religious practices. This landscape is not a mere backdrop for human activity; it often serves as a sacred space in cosmologies, origin accounts, and rituals. Contemporary geoscience and heritage scholars use the term

geoheritage to acknowledge this intertwining of geology with cultural heritage [

12]. Many geologically significant places carry intangible values—spiritual meanings, legends, and historical symbolism—layered atop their physical manifestation [

10]. Such culturally significant geo-sites are locations where the Earth’s features and human experience meet, giving rise to sacred narratives that give the landscape a profound meaning.

The paper is organized to guide the reader from a broad conceptual framing toward a focused case analysis, thereby demonstrating how geological features and cultural meaning are inseparable within a “peopled” landscape. The following section is the background that surveys the scholarship on geo-mythology, sacred landscapes, and UNESCO geoheritage, providing the theoretical scaffolding that situates El Malpais within a global comparative context. The following section on Materials and Methods then details the ethnographic work conducted with Acoma and Zuni representatives alongside a targeted literature review foregrounding Indigenous perspectives as the analytical anchor. The result section is structured into four sub-sections:

Section 4.1 explores mountains as integral parts of cultural landscapes and cosmologies,

Section 4.2 examines volcanoes and lava flows specifically within diverse cultural cosmologies, and

Section 4.3 focuses on the El Malpais as a culturally significant landscape.

Section 4.4. provides an examination of Mount Taylor and its connections to the El Malpais lava flows.

Section 5 is the concluding discussion, which is followed by the conclusions.

2. Background: The Integration of Culture and Nature

The connections between geology and human culture have gained international recognition in recent research [

10,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Scholars across anthropology, geography, and heritage studies emphasize that landscapes are culturally meaningful arenas shaped by and imbued with human experience. Indeed, it has long been recognized that sites valued for their geology often carry cultural significance, including spiritual meanings, origin accounts, historical events, and artistic inscriptions, that coexist with their scientific importance. In this article, the concept of geoheritage is used to encompass both the geological features of outstanding scientific, educational, or esthetic value and the cultural meanings attributed to them through human interaction [

17]. Similarly, the concept of

cultural landscape is used in this article to refer to the ways in which physical terrains are shaped, interpreted, and inhabited through cultural traditions and historical processes [

18].

The analysis builds on the premise that the ritual significance of geological features is best understood through the role they play in the formation and operation of living cultural landscapes [

13]. In other words, geology and culture are so intertwined that the broader landscape itself becomes the primary “text” through which heritage is interpreted. Anthropologist Tim Ingold sums up this view on the interconnectedness of landscape and geology quite well when stating: “The landscape tells—or rather is—a story. It enfolds the lives and times of predecessors who, over the generations, have moved around in it and played their part in its formation. To perceive the landscape is, therefore, to carry out an act of remembrance, and remembering is not so much a matter of calling up an internal image, stored in the mind, as of engaging perceptually with an environment that is itself pregnant with the past” [

5] (p. 152).

An essential aspect of the cultural landscape is the interconnectedness between various features in a landscape. Interconnectedness in this context refers to how various sites in a cultural landscape are connected in cultural representations such as origin accounts and rituals. Geological features such as mountains, valleys, seas, and rivers are not isolated elements but interconnected outcomes of long-term geological processes that have shaped the landscape over time. As disparate formations in a landscape are interconnected through the geological processes that formed them, the ritual significance of a landscape needs to be interpreted through interconnected places. As Stoffle and van Vlack argue about the Colorado River in the paper

Celebrating Creation, “From a Numic perspective, the river is one of the important veins of Mother Earth and all the tributaries that flow into the river and make up the functionally integrated sacred areas of the Colorado Plateau watershed” [

19]. This is just one of countless examples in which geological features connect places on a sacred level.

The interrelation between geological features and human origin accounts and rituals is contingent. That is, the cultural response to a sight can be articulated in different ways. Various cultural groups inhabiting an area might even interpret and interact with the same landscape differently. That said, dramatic features in the landscape often call for human responses. Mountains, ridges, and volcanoes have played essential roles in legends and rituals [

20]. Examples from every inhabited continent illustrate that from time immemorial, people have turned to dramatic Earth features to explain creation, connect with deities or ancestors, and anchor collective identity.

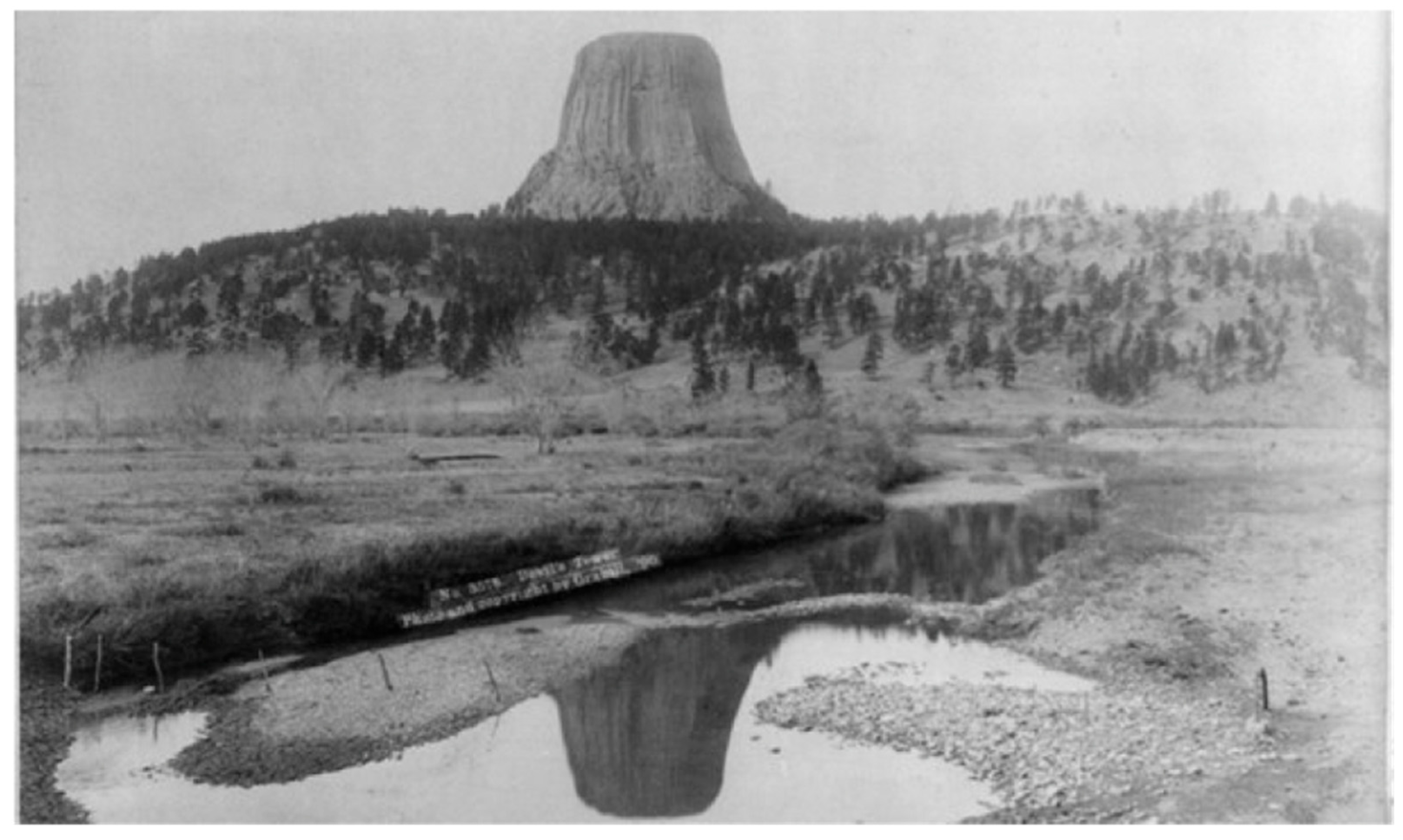

Examples include Uluru (Ayers Rock) in Australia, Mount Olympus in Greece, and Devils Tower (also known as Bear Lodge or Mateo Tape) in the United States—alongside other global examples such as sacred volcanoes and cave systems. While each culture’s narratives are unique, there are recurring themes: high peaks often symbolize a link between heaven and earth, caves lead to underworlds or wombs of creation, and erupting mountains often embody divine power [

21,

22]. Cultural geo-sites are often connected in geo-landscapes that tie locations together into

webs of significance [

23]. Pilgrimage trails and networks of sacred sites underscore that they are not isolated spots but the relationships among places that create a sacred geography. For instance, ethnographic testimony of Nuwuvi (Southern Paiute) and Newe (Western Shoshone) peoples describes a web of special spiritual places connected in sequence, forming the foundation of ceremonial journeys across the landscape [

24].

Narratives related to cultural landscapes are sometimes referred to as geomythology [

25]. Such geo-myths not only bind communities to their ancestral heritage but might also provide a guiding framework for how to relate to the land. Far from being a static body of lore, these stories can actively inform stewardship practices, reflecting intimate knowledge of ecological rhythms, water sources, and sustainable subsistence methods passed down through generations. Such stories “represent complex explanations of the origins and structure of the universe and the place and behavior of all elements in it” [

26]. As one geoscience perspective notes, geo-myths can preserve the memory of natural disasters or features and thus “help to better understand” past events [

10]. For instance, an ancient legend of a flooded valley might correspond to a volcanic crater lake formation. Such narratives, whether from the Australian Aṉangu’s Tjukurpa or the Zuni and Navajo traditions in El Malpais, remind us that geology and culture are not separate domains. Rather, they weave together into a cohesive worldview in which knowing and interacting with the land is inseparable from sustaining the community—an enduring testament to how Earth’s dramatic features become living, sentient parts of cultural life.

Throughout this paper, the term sacred geography is used to describe how geological features are imbued with spiritual and cultural significance. However, this sacredness is not monolithic [

27]. Rather, it encompasses multiple, interrelated dimensions that vary across traditions. In some cases, sacredness emerges through ritual function—as in shrines within lava tubes used for offerings and ceremonies, or pilgrimage routes that activate the landscape through performative movement. In other cases, sacredness reflects a mythic origin, where landforms like lava flows or Mount Taylor are seen as the embodied results of cosmological events, such as battles between deities or the emergence of ancestral beings. A third dimension is the ontological status of geological features—as animate, sentient entities or kin beings in ongoing relational worlds, rather than inert physical formations. These distinctions matter because they help reveal the multivocal nature of Indigenous epistemologies and prevent the flattening of spiritual meaning into abstract symbolism [

28]. By attending to these differentiated modes of sacredness, this study aims to more accurately represent the complexity of Indigenous relationships to place.

The interrelation of culture and geology has not only received attention in research but also in heritage management. In heritage management, this view is reflected in frameworks like UNESCO World Heritage cultural landscapes and Global Geoparks, which explicitly link geological and cultural values into one unified concept [

10]. While focusing on geology, UNESCO’s approach to geoheritage and Global Geoparks explicitly includes cultural narratives as an essential part of what makes a geological site valuable. According to UNESCO, a Global Geopark is not just a collection of rocks or landforms of scientific importance—it is “a single, unified geographical area where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education, and sustainable development” [

29]. This holistic concept means that the geopark “uses its geological heritage, in connection with all other aspects of the area’s natural and cultural heritage” to promote awareness and sustainable use of Earth’s resources [

29]. In other words, the geological features are seen in context, including how local people relate to them, the stories told about them, and the cultural practices tied to them.

UNESCO’s framework for geoheritage also overlaps with their work in World Heritage Sites [

30] and Intangible Cultural Heritage [

31]. Several famous geo-sites are recognized as mixed World Heritage properties for their natural and cultural value. For instance, Uluru-Kata Tjuta (Australia) and Mount Taishan (China) are inscribed for their geological significance and the associated indigenous beliefs and practices. UNESCO reports that as of early 2022, 39 World Heritage sites are listed as “mixed” natural-cultural properties, many of which involve geoheritage [

10]. Examples include the sacred travertine hot springs of Pamukkale with the ancient spa city of Hierapolis in Turkey, and the Meteora rock towers in Greece, crowned by Orthodox monasteries—these are places where geology and spirituality are built together [

10].

Additionally, UNESCO has supported studies on sacred natural sites [

32] and integrates respect for cultural traditions into conservation: guidelines often call for consulting with indigenous custodians of sacred mountains or caves when developing management plans. The UNESCO Global Geoparks Network (UGGp), which by 2024 included 213 geoparks in 48 countries [

29], serves as a platform to share best practices on this integration. Also, the International Commission on Geoheritage plays a prominent role in promoting geoheritage sites. In many geoparks, you will find interpretive panels or visitor center exhibits that tell not only the geologic story of how the rocks were formed but also the cultural story of what this rock means to the community [

10]. This dovetailing of science and culture enriches tourism and education and aligns with broader goals of sustainable development and intercultural dialog. In addition to UNESCO, the International Commission of Geoheritage, which is a sub-division of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), plays an important part in promoting geoheritage perspectives by its nominations of significant geoheritage sites and their promotion, dissemination, and education in geoheritage [

33]. For example, Devils Tower, which will be discussed further in this paper, is recognized as a Geological Heritage Site [

34].

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods design that combined community-based ethnography with a literature review. The overarching goal was to document how Indigenous knowledge systems map onto the volcanic landscape of El Malpais and to situate those local understandings within broader scholarship on sacred geological sites. The primary empirical foundation of this paper is a study conducted by the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, of which the author is a member. The ethnographic study of the area’s cultural significance was carried out in El Malpais National Monument during 2023 and 2024, in collaboration with representatives from the Zuni and Acoma communities. A total of 10 representatives from Zuni and Acoma, appointed by their tribal government, were interviewed on-site for a duration of eight days in total.

Data were gathered during site visits, where these designated tribal representatives identified and interpreted culturally significant features. Fieldwork combined participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and on-site cultural interpretation. In the studies, the tribal representatives were invited to share their knowledge and information on various sites. They were encouraged to speak freely about the visited sites, but a set of standardized questions was also asked. These questions included inquiries into traditional land use, ritual significance, and its connection to other sites. These items have been used in several similar studies and are well adjusted to Indigenous-led research protocols. These questions facilitated consistency across interviews while allowing space for open-ended responses rooted in oral traditions.

All conversations and interviews were recorded and transcribed. These transcriptions were analyzed with a focus on how geological features were situated within broader cultural landscapes, attending to the spatial, ritual, and narrative connections articulated by tribal representatives. Rather than segmenting data into abstract themes, the analysis prioritized understanding how specific sites were embedded in networks of meaning, linking places through pilgrimage routes, origin stories, seasonal practices, and spiritual significance. Particular attention was paid to expressions of interconnectedness between landscape features, reflecting the paper’s conceptual framing of the cultural landscape as a lived, storied, and relational geography. The analytical process thus sought to foreground Indigenous ways of knowing and landscape interpretation, with interpretations reviewed in dialog with tribal representatives to ensure respectful and accurate representation of culturally significant insights.

The study was funded by the National Parks and conducted through Arizona State University. This research included a Traditional Use Study (TUS) and an ethnographic resource inventory for El Malpais National Monument (ELMA). Participation by the tribal representatives is entirely voluntary and governed by the tribes themselves, often in coordination with pan-tribal organizations such as the National Congress of American Indians. Since the representatives were appointed by their respective tribal authorities, the study did not require a formal institutional ethical review. The tribe and its representatives share a mutual interest with the researchers in participating in the study, as it contributes to ELMA’s Cultural Resources Inventory System and supports future land management and stewardship efforts grounded in Indigenous perspectives.

The research was conducted with a recognition of the ethical sensitivities and epistemological responsibilities involved in working with Indigenous knowledge systems and sacred landscapes. Field interactions were grounded in a culturally responsive framework, where tribal representatives served as active knowledge holders and collaborators rather than passive informants. The project adhered to community-based research principles, including prior informed consent, tribal approval, and voluntary participation, and followed protocols established by the respective tribal authorities. Given the spiritual significance of many sites discussed, care was taken not to disclose restricted knowledge or sacred specifics deemed inappropriate for public dissemination. Statements and interpretations were collaboratively reviewed with tribal representatives to ensure respectful representation and cultural accuracy. The translation of Indigenous worldviews into academic categories was approached critically, acknowledging the limitations of Western epistemological frameworks and seeking to foreground Indigenous voices through direct quotation, co-interpretation, and relational engagement.

In addition to the data collected in the traditional use study described above, a focused literature study was conducted to build a comparative frame for the ethnographic evidence. In an initial Boolean search on Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, papers were identified that discussed the cultural significance (using strings such as ritual use, origin myth, pilgrimage, sacred) of geological features (volcano, lava field, mountain massif, cave). The literature study took a particular interest in papers that provided first-hand historical and ethnographic accounts of the cultural connection between landscapes and culture rather than purely theoretical discussions. These previous studies have helped identify examples of culturally significant geological features, particularly mountains and volcanoes. Through these examples, similarities and differences have been identified in the cultural understanding of such geological features.

The resulting synthesis of the literature review (presented in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2) is not intended to be exhaustive but to demonstrate similarities and differences in indigenous cosmologies in the sacred narration of geographical features. The examples included in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2 of this paper serve primarily as illustrative instances of diverse cultural responses to prominent geological features rather than as subjects of comparative cultural analysis or detailed ontological exploration. Their purpose within the text is specifically to highlight globally recurring themes—such as the frequent sacralization of geological formations and their incorporation into cosmological narratives—while explicitly recognizing that such sacralization is neither universal nor uniform. Indeed, mountainous geographies can and do receive varied conceptualizations, ranging from sacred and spiritual attributions to entirely secularized or pragmatic interpretations. This paper consciously acknowledges these differing cultural and ontological perspectives, emphasizing that the provided examples illustrate common but not universal patterns of human–geological relationships. By briefly referencing these global examples, the discussion situates El Malpais within broader international discourses on geoheritage, maintaining a detailed and ethnographically informed focus without implying universal equivalence or neglecting the rich cultural variability inherent in the perception and interpretation of mountains.

The representation of Indigenous views on landscape and sacred geography within this paper inevitably involves methodological and epistemological tensions inherent in translating culturally embedded spiritual worldviews into academic discourse and heritage management practices. This research explicitly adopts a mixed-methods approach, combining ethnographic fieldwork and targeted comparative literature review with indigenous perspectives. Nonetheless, the authors acknowledge the complexities and potential tensions arising from this translation, particularly the risk of simplifying or essentializing intricate spiritual beliefs into generalized academic categories. Recognizing these challenges, this paper emphasizes an interpretive framework that foregrounds Indigenous voices and experiential knowledge, advocating for collaborative, culturally sensitive methodologies. Such an approach seeks not only accurate representation but also aims to respect Indigenous epistemologies by recognizing the limitations of conventional academic discourse in fully capturing spiritual and cultural meanings. Consequently, this study argues for heritage management practices and scholarly frameworks that are reflexive and flexible enough to incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing, thus addressing and mitigating the epistemological tensions highlighted.

4. Results

4.1. Mountains as Cultural Landscapes

Mountains have long held a prominent place in the human cultural imagination, often regarded as sites of spiritual significance, where connections between the human and the divine are perceived to converge. In many cultures, high peaks are revered as sacred sites due to their proximity to the sky. For example, in ancient Greek mythology, Mount Olympus was venerated as the meeting place of heaven and earth, the legendary home of Zeus and the other Olympian gods [

35]. The Greeks viewed Olympus less as a literal residence one could visit than as a cosmic peak—a zone of great power symbolizing the connection between earthly terrain and the divine realm [

36]. Similarly, in the Abrahamic tradition, mountains carry sacred significance: the Hebrew Bible describes prophets encountering God on Mount Sinai, and Christian writings identify Jerusalem’s Mount of Olives as the prophesied site of Christ’s return. These examples show a common motif—mountains as axes mundi, pillars connecting heaven and earth [

22].

Across the world, Indigenous cosmologies view mountains or massifs as sacred. In the Andes of South America, for instance, the Indigenous peoples regard the high peaks as living deities or powerful spirits [

37]. For the native populations of the Andes, “the mountains are sacred places and central elements of a mythical historical identity” because, in Inca origin legends, the founding ancestors emerged from the land itself [

37]. Mountains are understood as the dwelling places of the dead and a host of spirits. Inside the mines of the Andean mountains, miners honor an ambivalent spirit called El Tío, who resides in the dark caverns and must be appeased with offerings [

37]. This illustrates how summits and the interior “wombs” of mountains figure in spiritual life. Taking an example from another continent, Mount Kenya is revered among the Kikuyu as God’s home on earth (

Figure 2). Kikuyu communities face the mountain when praying, regarding it as a sacred direction [

38]—this example also shows how a geological landscape is integrated not only in origin accounts but also in religious or spiritual rituals.

A recurring theme in the understanding of mountains and other geological features is their connection to the creation of the world or the creation of humankind. For example, Uluru (Ayers Rock) in Australia is connected to the Dreamtime in Aṉangu culture, and the rock is seen as evidence of ancestral beings who shaped the land and left behind physical marks [

39,

40]. Also, Devils Tower (

Figure 3) is widely regarded by Indigenous peoples as a sacred site of creation—a majestic rock shaped by supernatural forces [

41]. Many tribal stories describe a giant bear whose claws etched the Tower’s grooves and a divine act that lifted it skyward. Sundstrom [

42] writes that in Cheyenne tradition, Devil’s Tower is revered as the place where a girl was rescued from a giant bear spirit, connecting the formation to the constellations of the Pleiades and the Big Dipper. This shows that origin accounts not only link to geological features but also link the physical place to features in the wider galaxy.

4.2. Volcanic Landscapes as Geo-Sacapes

Perhaps no geological phenomenon demonstrates raw earth power more dramatically than volcanoes and their lava flows. From this perspective, it is little surprise that cultures living in the shadow of active volcanoes have developed rich origin accounts around these fiery mountains, sometimes personifying them as deities or viewing eruptions as divine judgments or creations. In Roman mythology, the idea of a god of fire under the mountain was evident in the origin accounts of Vulcan, the deity that has given name to volcanoes in the English language. The Romans believed that Vulcan’s forge lay beneath Mt. Etna (

Figure 4), explaining its periodic eruptions as the god’s smithing activity [

44]. Another example comes from Hawaii, where the volcano Kīlauea on the Big Island is sacred as the home of Pele, the goddess of volcanoes [

45]. Hawaiian chants and oral history describe Pele’s destructive power, consuming forests and villages in her fiery path. Holmberg [

46] notes that the indigenous Ngäbe people of Panama blamed the frequent earthquakes on a spirit living by the Barú volcano and would shoot arrows at it to scare the spirit away. There are also native American origin stories of the El Malpais lava flows, where the origin is attributed to deities who decided to destroy the earth with lava [

47], but in these legends, the destruction was stopped by the rain that solidified the flows.

Although often connected to destruction in origin accounts, volcanoes are also related to rebirth and creation. In the American Southwest, many Pueblo groups regard the lava tubes or other caverns as entrances to the Sipapu (Shipap to the Acoma)—the place of emergence where their ancestors climbed from the underworld to the surface [

13]. Volcanic eruptions and, by extension, volcanic geological features are often connected to creation, as the eruption quite literally produces new land masses. In Hawaii, volcanic eruptions are traditionally understood as the rebirth of the earth [

13]; they are understood as a creative force that can cause new land to be formed through lava flows that harden into rock [

45]. Likewise, the lava flows of El Malpais (

Figure 5) have been connected to fertility in Acoma lore [

48]. Stoffle and Van Vlack argue that “Native American people residing in the western U.S. share an understanding of volcanoes as places where the earth is reborn and eruptions are the active process of rebirth” [

49] (p. 3). Furthermore, “the Native groups recognize the volcanic activity of Sunset Crater as involving lessons of rebirth that are necessary for human survival” [

49] (p. 12).

There are also other examples of cultural groups who live near extensive lava flows and have integrated them as ritual sites or as part of origin accounts. For example, Icelandic folklore, born in a land of frequent volcanic eruptions, is replete with tales of how lava fields were formed by trolls or how eruptions were punishments from irate spirits [

50]. The Icelandic accounts are thus an example of the duality of some geo-mythology, where the volcanic eruption, while having negative connotations, also gives birth to a new land. In essence, in these cases, volcanoes and their lava landscapes are experienced not just as physical phenomena but as a sentient part of the world in many traditional cultures. This reinforces the theme that geological processes are viewed spiritually, not just physically. Holmberg [

46] suggests that volcanoes are ambiguous, as they are both permanent structures and evolve through their eruptions, giving them an uncertain “placement along the nature-culture continuum” [

46] (p. 203).

Aligned with their significance in origin accounts, volcanoes are known to be central to cultural beliefs and as sites of rituals [

49]. Stoffle and van Vlack note that in the Sandia Pueblo in New Mexico, USA, the “volcanoes and the spirit trails are interrelated, forming a communication nexus to the spirit world that can be used by living people to help their prayers and medicine in this world,” [

49] (p. 19) and that volcanoes are still significant in prayers and ceremonies. They continue to argue that several native American tribes describe volcanic landscapes as places where humans receive power, songs, and spiritual messages [

49]. These are examples showing that volcanic landscapes are not merely geological features but sacred, animated beings within cultural cosmologies. Volcanic landscapes are not passive terrains but active spiritual agents in origin accounts and rituals, reinforcing the idea that geoheritage includes deeply layered cultural and cosmological meanings.

4.3. El Malpais as a Cultural Landscape

El Malpais is a case in point of the interconnectedness between connected geological features and cultural narratives, as well as the cultural significance of volcanic landscapes and lava flows. Far from avoiding the lava lands, Indigenous peoples have interacted with them and revered them in various ways since time immemorial. Archaeological and ethnographic evidence shows that humans in this area have been crossing and utilizing the lava terrain for millennia, leaving behind trail markers, camps, and ceremonial sites [

3]. According to Benedict and Hudson [

51], a close connection between the landscape and the spiritual world is prominent in the perspectives of most Native Americans, stating that “the concept of landscape is not limited to the physical realm of topographic features, stone, trees, water, but also includes the spiritual world” [

51] (p. 14). El Malpais is a prominent example of such a place where heritage is integrated with topographic features, and it figures in the origin stories and ceremonies of Native American people.

Figure 5.

Malpais lava flows have cultural and historical significance for Acoma, Zuni, Laguna, and the Navajo.

Figure 5.

Malpais lava flows have cultural and historical significance for Acoma, Zuni, Laguna, and the Navajo.

A National Park Service survey notes that “El Malpais is the homeland of native peoples and is embedded in the origin stories, ceremonies, and continuing traditions of the Pueblo of Acoma, Pueblo of Zuni, Pueblo of Laguna, and the Navajo Nation” [

3]. Holmes writes that “The creation of lava flows is recorded as an incident in the creation and migration myth of the Zuni people” [

52] (p. 31). For the Pueblos, the lava’s numerous caves and basalt amphitheaters are said to be dwelling places of spiritual entities or portals to the underworld. Certain ice caves (where ice persists year-round in lava tube recesses) were traditionally used as a source of sacred water. Hooker [

1] writes the following: “Within the lava flows, caves formed, and in the caves the Indians often found ice. Ice accumulates in the caves and remains throughout the summer due to the unusual microclimatic effects of the lava formations. The Indians maintain shrines at the ice caves, believing that the ice is a gift of water from KauBat’ to the people” (p. 143). As such, the accounts maintained knowledge of the ice that was also much needed for survival in the harsh environments of the region.

Pottery sherds, petroglyphs, and even ancestral Pueblo dwellings (in their current form referred to in Zuni as

enote hes’ahdowe, meaning old homes) on the edges of the flows all attest to a long, continuous relationship between people and the volcanic landscape. The land was not a forbidden zone but rather a “living homeland” that demanded respect and provided teachings [

53]. The name “El Malpais” (“the badlands”) is a colonial one, showing that the Spanish explorers saw these jagged lava fields as cursed and impassable. However, the Pueblo peoples and Navajo saw them as a meaningful part of their homeland. With reference to El Malpais, Hooker [

1] says: “the Native American’s belief in the absolute immanence of the Creator in creation undergirds and structures all his ethics. They believe that they cannot disturb the Earth too much or the Great Spirit will leave, the cosmic order will be disrupted, and they will be lost. Of particular concern to Native Americans is the need to protect certain spiritual landmarks, such as particular mountain peaks, lakes, volcanic features, rivers, valleys, and forest groves” [

1] (p. 134–135).

This quote shows that volcanic features can be essential to ritual and world-upholding ceremonies and are thus not merely a place to avoid. Stoffle and Van Vlack [

49] show that the Zuni recognizes a sacred relationship between volcanoes, rocks, mountains, and medical plants. Furthermore, Stoffle and Van Vlack stress the importance of volcanoes as guideposts, writing that “Zuni Pueblo and Zia Pueblo elders said the volcanoes were an obvious guidepost and visual marker for people traveling between sacred mountains such as the Santa Fe Mountains, the Sandia Mountains, Mt. Taylor, the Ortiz Mountains, and the Magdalena Mountains” [

49] (p. 20).

The ritual significance of the volcanic landscapes is underscored by the shrines and offerings left at various sites identified by the tribal representatives in the ethnographic study. The Zuni representatives viewed volcanic eruptions as a powerful activity of Mother Earth, causing both rebirth and destruction. While volcanic sites are recognized as spiritual places for seeking knowledge and power [

49], the eruptions were also seen as destructive. The Zuni representatives explained that red hematite, pottery sherds, and other offerings were placed in the lava-tube shelter caves (

Figure 6)“so that we will not go through the devastation of eruptions again.” These types of world-upholding ceremonies are still conducted today, with Zuni people continuing their pilgrimage for offerings, asking the fiery forces (Adani) to stay and not come to the surface. Scholars such as Ruth Van Dyke [

54] have argued that participating in ceremonies at these geologically defined center places was seen as necessary to maintain cosmic order—to keep their lives—and the world—in balance.

From the ethnographic evidence, it is clear that various sites in the El Malpais are part of a larger cultural landscape. Speaking of the McCartys Lava Flows and trails, the Acoma tribal representatives of the study stressed that everything along this volcanic valley is connected; the flow, trails, water-catchment tinajas, and farming flats together illustrate how ancestors knew how to live off the land shaped by eruptions. Zedeño et al. (2001) cite Acoma representatives who talk about the El Calderon cinder cone in the El Malpais National Monument as naturally connected to other volcanoes in the region, connections that are underground and play a significant role in the creation of the world. For the Navajo, the cinder and flows are read as the spilled blood of a defeated monster, knitting Navajo cosmology directly into the terrain [

55].

The most prominent argument for the connectedness of geographical and geological sites in the El Malpais area is the pilgrimage trails, which physically and spiritually connect locations in the landscape. The places are connected through physical trails and spiritually through songs and lore [

55] (p. 138). These routes were not only of practical use but were also ways of connecting the spiritual features of the landscape. Ancient trails with both practical and ritual significance cutting straight across the lava are a testament to how Puebloans adapted to and respected this landscape [

3]. They built rock cairns to mark the way over the otherwise disorienting expanse of basalt, effectively encoding their knowledge of safe passage. Oral tradition recalled by the Acoma and Zuni representatives during the field study holds that these trails were both trade routes and pilgrimage routes, and travelers would offer prayers at certain points along the path across the Malpais [

3]. In this way, movement through the lava field took on a spiritual dimension, reinforcing bonds between communities and the land. Moving through the landscape—whether physically through pilgrimage or spiritually through traditional songs—is a performative act that weaves together different parts of the terrain, reaffirming its cultural significance while allowing meanings to evolve over time.

As such, El Malpais’ volcanic features are not merely geology but animate partners: mountains that govern weather, lava domes that teach history, tubes that shelter water and people, and black-rock trails that guide ritual journeys. Together, they are integral to Native American identity, stewardship duties, and material culture. In El Malpais volcanoes anchor creation stories, lava flows stitch together holy mountains, and ice caves provide sacred water and ritual space. Volcanism is thus woven into pilgrimage routes, ceremonial calendars, resource use, and the identity of several tribes. According to the tribal representatives knowledge of the volcanic eruptions has been passed down from generation to generation along with knowledge of how to perform the rituals to prevent the eruptions from happening again.

4.4. Mount Taylor and Its Connection to El Malpais Lava Flows

The cultural significance of El Malpais is even more pronounced when considered in the context of the larger sacred geography. Just to the north of the lava flows rises Mount Taylor (

Figure 7), a towering extinct stratovolcano that is one of the most sacred mountains in the region [

56]. Several authors have pointed out Mount Taylor as a significant physical and cultural landscape of local inhabitants throughout recorded history [

51,

52,

57,

58]. Holmes [

52] stresses its connection to El Malpais by stating that: “Mount Taylor is probably the most significant sacred locality in the vicinity of El Malpais.” For the Navajo, Zuni, Acoma, and Laguna (as other authors have noted) [

51], Mt. Taylor has significance also to other Native American groups including the Hopi, the Jicarilla Apache, and many of the Rio Grande Pueblos), the whole peak is an obsidian and sacred plant collection area, and on the peak is a shrine which is visited by all four tribes” (p. 26) The surrounding landscapes (including El Malpais and the adjacent mesas) form an interconnected sacred region for at least four cultures: Navajo, Acoma, Laguna, and Zuni [

48,

58]. In 2008, a coalition of these tribes plus the Hopi successfully nominated a 400,000-acre area around Mount Taylor as a Traditional Cultural Property for federal protection, explicitly citing its sacred status [

59].

Benedict and Hudson [

51] argue that Mount Taylor is defined as a landscape larger than the peak and its summit, encompassing the adjacent mesas, plateaus, and valleys. Native American tribes have historically used—and still use—the mountain for a wide range of traditional cultural and spiritual practices. These include activities such as gathering natural materials like plants, minerals, pigments, feathers, soil, and sand, hunting, making religious pilgrimages, visiting springs, and performing ceremonial offerings [

51]. According to Laguna consultants in the study of Zedeño et al. [

55], the area of El Malpais has many connections. The lava connects the area to the mountains from whence the lava flows, for example, El Calderon. The lava also stretches from Mt. Taylor to the north and therefore connects El Malpais to this sacred mountain. In addition to being an important site linked to origin accounts and with ritual significance, Mount Taylor is also a distinctive landmark to direct and aid in travel.

To the Navajo, Mt. Taylor is known as Tsoodził (Turquoise Mountain). Mount Taylor is one of the four cardinal sacred mountains marking the traditional boundaries of the Navajo world [

59]. According to Navajo origin accounts, First Man planted a lump of turquoise at the peak of Tsoodził to invest it with protective power, and the mountain is personified as a goddess who blesses the land [

60]. The mountain is equally sacred to the Pueblo peoples—for Acoma and Laguna, it is often called Kaweshtima or Matt’s Mountain and is central to rain ceremonies and seasonal pilgrimages [

57]. For the Acoma, the peak of Mount Taylor is associated with the north and is the home of a deity referred to as Ca’ kak who is said to bring rain and snow [

61]. The Zuni relation to Mount Taylor is described by Colwell and Ferguson with the following words [

58] (p. 239):

For Zunis, Mount Taylor is a living being. Zuni cultural advisors explain that the mountain was created within the earth’s womb, just as humans were. As a mountain formed by volcanic activity, it grew and still continues to shift shape. The mountain gives life, just as people do. As a snow-capped mountain most of the year, it is a symbol of what is most needed in a land constantly wanting moisture. The snow melts in spring and nourishes plants and wildlife for miles. Water is the mountain’s “blood.” Deep below is the “heart.” The buried minerals are the mountain’s “meat.” Like all living beings, in the Zuni view, the Zuni people have a social relationship with the mountain. Mount Taylor is a kin.

These examples of tribal interpretations of Mount Taylor provide some examples of its strong cultural significance.

To the Acoma the Kaweshtima is the home of the Spiritual Beings, who created the El Malpais lava flows [

48], highlighting the interconnectedness between the mountain and the lava fields. Also, Navajo oral history for Mount Taylor directly links it to the creation of the El Malpais lava flows—forging a single narrative between the mountain and the lava field. In Navajo legend, after the great monster Yé’iitsoh terrorized the land, the sacred Twins defeated this monster on Mount Taylor [

62]. When Yé’iitsoh was slain, his blood poured down the mountain’s slopes and congealed into the vast black lava fields of what the Navajo now call the Malpais [

59]. Thus, the frozen rivers of lava are the blood of a vanquished evil, sanctified by the Warriors’ victory and marking the landscape as a site of cosmic struggle and deliverance. This story sacralizes the lava: it is the physical proof of the past and a reminder of the Navajo deities’ protection. In ceremonies like the Blessingway and Enemyway, Mount Taylor (Tsoodził) is invoked for its power, and by extension the lava fields—the blood of the monster—are part of that sacred narrative geography [

57,

63].

When Navajo people travel near El Malpais, they know it as a place where legendary events unfolded; even the turquoise pebbles found are a reminder of the creation story [

64]. Similarly, the Pueblos have stories of Twin War Gods or Hero Twins who fought giants in primordial times [

65], paralleling the Navajo version and underscoring the shared reverence for the landscape. In one version told about the Black Rock River, El Malpais is said to be formed from the blood of the Blind Kachina, KauBat [

1]. In this account, KauBat’s sons—the Twins—robbed their father of his sight to penalize his unbridled gambling. As the blood cooled, “it solidified into serpentine ropes and cresting waves of black rock” (p. 143).

While Mount Taylor holds deep spiritual significance for all the Indigenous groups discussed, their interpretations reveal both shared themes and distinct ontologies. Across Zuni, Acoma, Laguna, and Navajo traditions, the mountain is recognized as a life-giving force, often personified and linked to origin stories, seasonal cycles, and ceremonial practices. Yet, the specific cosmological roles attributed to Mount Taylor differ: the Navajo revere it as Tsoodził, a protective boundary of their sacred geography and the site of mythic battles; the Acoma and Laguna emphasize its role as a source of rain and home of spiritual beings; while the Zuni view it as a living relative whose body sustains the land and whose vitality reflects a social relationship with the people. These perspectives converge in viewing the mountain as animate and sacred but diverge in the narrative textures, ritual associations, and symbolic meanings they attach to it—underscoring a multivocal sacred geography rooted in a shared landscape yet articulated through culturally distinct worldviews. These interpretive variations underscore the paper’s central claim of multivocality: that sacred geography is not a uniform category but a dynamic assemblage of culturally distinct yet overlapping epistemologies. Attending to these nuances affirms the importance of honoring the diversity of Indigenous worldviews rather than seeking a singular explanatory framework.

5. Discussion

El Malpais exemplifies how intangible cultural heritage emerges through lived relationships with dramatic Earth formations, forming an interconnected cultural landscape where geology and spirituality are inseparably entwined. As has been shown throughout the paper by the Acoma, Zuni, Laguna, and Navajo peoples, the region’s volcanic features—lava tubes, ice caves, and peaks like Mount Taylor—are not inert geological formations but animate participants in ancestral narratives, ritual practice, and cosmological meaning. Lava tubes are seen as portals to the underworld, ice caves as sacred water sources, and volcanic peaks as living beings, central to ceremonies, offerings, and pilgrimage routes. These sacred engagements transform what might appear to outsiders as desolate terrain into a spiritually vibrant landscape, densely inscribed with memory and meaning. The cultural heritage of El Malpais thus cannot be understood apart from its geological typology: its lava flows, badlands, and bluffs compose a sacred geography in which physical and spiritual dimensions coalesce. The ethnographic findings of this and previous studies underscore that this landscape functions as a network of interrelated sacred sites, anchored not only in place but in practice, sustaining Indigenous identity and cultural continuity across generations.

Contemporary landscape phenomenology provides a robust theoretical lens for understanding concepts of an interconnected geoheritage. Rather than treating land as an inert backdrop, phenomenologists emphasize the co-constitutive relationship between people and place. Ingold’s “dwelling perspective,” for example, dissolves the divide between subject and object by positing that humans are immersed in a living field of relationships; “the distinction between the animate and the inanimate seems to dissolve” [

5]. From Ingold’s perspective, humans do not act upon the land so much as to move along with it as part of its life process. Likewise, Casey’s place-focused phenomenology contends that perception of the environment shapes our experience as sentient beings [

66]. This theoretical framing resonates with Indigenous epistemologies, which have long regarded the landscape as alive and relational. Many Indigenous traditions conceive of mountains, rivers, and other features as sentient kin or ancestors rather than passive scenery [

67]. By engaging phenomenological and Indigenous perspectives, we deepen the notion of geoheritage as fundamentally relational and animate—sacred geographies are not merely sites of geological interest but living domains of interaction, imbued with spirit and meaning through the reciprocal engagement of land and people [

5]. This approach moves beyond the descriptive use of these concepts, situating them within a rigorous theoretical context that acknowledges landscape as an animate, storied, and intersubjective realm [

68].

Furthermore, the paper’s comparative approach situates El Malpais within a broader context of culturally significant geosites globally, offering insights into how diverse cultures attribute meaning to geological processes. By integrating ethnographic data with comparative literature, the research underscores recurring themes in global geoheritage discourse, such as the spiritual animation of landscapes, relational geographies, and the culturally constructed meanings of geological events [

69]. It positions El Malpais as an example of an Indigenous sacred landscape in which lava flows, cinder cones, underground chambers, and high mountains cooperate to sustain a unified cosmological geography—one that extends from the subterranean depths to the stellar canopy above.

This interconnected perspective aligns with global scholarly discussions on geoheritage and cultural landscapes. Landscapes like El Malpais demonstrate that geological and cultural values are inseparable. As Tim Ingold articulated, landscapes themselves tell stories embedded with the lives and memories of those inhabiting them [

5]. Recognizing geological sites as animate components of Indigenous cosmologies highlights their cultural importance. This study contributes an empirical case study to geoheritage scholarship by documenting the specific ways Indigenous communities actively engage with geological features as part of their living traditions, highlighting a dynamic interplay between human cultures and geological phenomena [

68]. This paper has also shown how perspectives from various tribes make the cultural landscape multivocal. El Malpais exemplifies a “peopled” landscape—a terrain where the earth’s features and the community’s history are entwined and continuously co-constituted. The paper has demonstrated that sacred geographies are defined by networks of meaningful places in the landscape, where geological features become sites of memory, ritual, and connection between humans and the larger cosmos—does so by connecting sites with other physical locations in the area connect geological features to the spiritual realm through origin accounts.

The paper argues for collaborative conservation approaches that integrate Indigenous perspectives, aligning with international models such as UNESCO Global Geoparks, thus advocating for inclusive stewardship of landscapes where natural and cultural heritages are inseparable. From a heritage management perspective, this integrated view necessitates inclusive, culturally informed stewardship. Traditional divisions between natural and cultural heritage fail to capture the essence of such landscapes. Thus, collaborative management approaches—such as co-management strategies practiced by agencies like the National Park Service—are essential. Practically, this approach requires continuous engagement with Indigenous communities, ensuring their perspectives and traditional practices shape management policies. Such collaborations not only preserve physical sites but also protect the intangible heritage associated with them.

The tribes have both similarities and differences in their world views and their connection to the cultural landscape. However, being able to access culturally significant places and preserve trails and viewscapes is an essential part of maintaining cultural continuity. This paper advocates for ongoing dialog between scholars, land managers, and Indigenous communities, emphasizing that sustainable management practices must respect and incorporate traditional ecological knowledge and cultural values. This holistic perspective supports cultural continuity: by safeguarding the land in a way that accommodates traditional practices (such as pilgrimages, ceremonies, and resource gathering), land managers help ensure that the spiritual and cultural connections between Indigenous communities and El Malpais remain for future generations. It also aligns with the principle that those who have historically cared for and understood the landscape should play a leading role in its stewardship.

The management of El Malpais is embedded in historical colonial processes, significantly impacting Indigenous land rights, access, and traditional stewardship practices. Colonial expansion, subsequent federal land designations, and related conservation policies have often restricted Indigenous communities’ access to sites of spiritual and cultural significance, imposing management frameworks that can conflict with traditional ecological knowledge and sacred geographies. Consequently, the current national monument status of El Malpais, although protective in intention, must be contextualized within a broader history of dispossession and restricted sovereignty. Acknowledging these tensions, the paper emphasizes the importance of incorporating Indigenous perspectives and restoring traditional access and stewardship practices to adequately recognize and honor Indigenous heritage and ongoing political struggles related to land rights.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that the volcanic landscape of El Malpais is not merely a geological phenomenon, but a living cultural landscape imbued with spiritual, historical, and epistemological significance for the Acoma, Zuni, Laguna, and Navajo communities. Through ethnographic engagement and comparative literature analysis, the research reveals that lava flows, cinder cones, caves, and mountains are experienced as animate agents, integral to origin stories, ritual practice, and cultural continuity. These findings affirm that geoheritage cannot be fully understood without attending to the intangible cultural meanings and Indigenous knowledge systems that animate such landscapes.

By integrating phenomenological and Indigenous perspectives, the paper contributes to a more relational and co-constitutive understanding of landscape—what might be termed a “peopled cultural landscape”—wherein geological features are entwined with human experience, memory, and ceremony. This approach challenges reductive divisions between natural and cultural heritage, instead advocating for heritage frameworks that acknowledge the sacred and storied qualities of land. El Malpais thus emerges as a paradigmatic example of sacred geography, where the Earth’s processes are not only observed but actively engaged through spiritual reciprocity and cultural stewardship.

In light of ongoing challenges posed by colonial land governance and heritage management regimes, this research underscores the importance of collaborative, community-led conservation strategies that center Indigenous voices and ontologies. Only by restoring access, recognizing spiritual sovereignty, and embedding Indigenous epistemologies in management practices can the cultural and geological integrity of places like El Malpais be sustained. As a case study, El Malpais offers a compelling argument for expanding the scope of geoheritage scholarship and policy to include relational and lived dimensions of geological landscapes.