Abstract

How to coordinate the relationship between nature reserves and surrounding communities to achieve a win–win situation for protection and development has become an urgent issue that governments around the world need to address. The concept of community co-management emerged in this context, aiming to promote cooperation and interaction between protected areas and surrounding communities, achieve sustainable use of natural resources, and promote the healthy development of the community economy. This study conducted empirical analysis using the Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve and surrounding communities in China as a case study. This study aims to reveal the key factors affecting the perception of the households in the surrounding communities of the national nature reserve through an in-depth analysis of their perceptions, attitudes, and actual effects on the innovative management model of community co-management. At the same time, it provides empirical evidence and theoretical support for the construction of a more reasonable, efficient, and win–win nature reserve management model. Based on field research and interviews, combined with a questionnaire survey of stakeholders, this study utilized the Q method to conduct a comprehensive analysis of household perceptions under community co-management. The research results indicate that community co-management is an effective path to promote the coordinated development of the local economy, society, and ecology. Specifically, this model not only significantly promotes employment and entrepreneurship among community residents but also achieves economic self-sufficiency and steady growth by cultivating characteristic industries and building distinctive brands. Further analysis reveals that improving residents’ well-being is the core value of community co-management. Meanwhile, system reform is seen as the key to promoting the deepening development of community co-management. This study not only helps to enhance households’ understanding and participation in ecological protection and promotes the deep integration of ecological protection and community development but also provides valuable experience and inspiration for the management of nature reserves in other regions around the world.

1. Introduction

In the context of an increasingly severe global ecological environment, protected areas serve as crucial barriers to maintaining biodiversity and ensuring ecological security. Their effective management and sustainable development have become a focal point of international attention [1]. As of October 2024, the number of protected areas worldwide has exceeded 300,000, covering a total area of approximately 52.31 million square kilometers, or about 24.69% of the Earth’s surface1, effectively protecting numerous rare and endangered species and their habitats. However, the establishment of nature reserves often comes with conflicts and tensions with local communities and farmers. These conflicts mainly stem from restrictions on resource utilization by communities surrounding the reserve and potential threats to the reserve’s ecological environment posed by community development [2,3,4]. On one hand, strict management of nature reserves restricts the traditional livelihood activities of local farmers, leading to resistance from some farmers towards the reserves. On the other hand, overdevelopment in surrounding communities, such as illegal logging and poaching, poses serious threats to the reserve’s ecosystem. Therefore, how to harmonize the relationship between nature reserves and surrounding communities and achieve a win–win situation for both protection and development has become an urgent issue to address [5]. In this context, the concept of community co-management emerged to promote cooperation and interaction between protected areas and surrounding communities, achieve sustainable use of natural resources, and promote the healthy development of the community economy.

The theory of community co-management originated from the development of community forestry. Since the 1960s, countries have developed distinctive contractual management and protection models based on their respective national and forest conditions [6,7,8]. Examples include India’s “Joint Forest Management”, Japan’s “Forest Production Portfolio”, and Nepal’s “Forest Use Groups”. These models emphasize the democratization and transparency of community participation and resource management, laying the foundation for the later theory of community co-management. International organizations such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the International Union of Forests (IUFRO) have played an important role in promoting the development of community co-management theory [9]. They not only promote community forestry as an internationally recognized term but also promote the widespread dissemination and deepening of community co-management concepts through hosting international conferences, publishing research reports, and other means. When discussing the empirical research and practical cases of community-based conservation (CBC) in nature reserves, we need to deeply analyze the complex social ecosystem behind this model and its multi-dimensional impact. Community co-management, as an innovative approach to natural resource management, aims to achieve a win–win goal of biodiversity conservation, community economic development, and social well-being improvement by enhancing cooperation and interaction between local communities and conservation agencies [10]. The following is a further expanded explanation of research and practice in this field.

The operation mechanism and effect evaluation of the community co-management model. The successful implementation of community co-management relies on a sound operating mechanism, which usually includes clear power distribution, responsibility definition, resource utilization rules, and benefitor-sharing mechanisms [11]. The researchers conducted a case analysis to explore in detail how different countries and regions construct adaptive co-management models based on local social, cultural, and economic conditions, and ecological environment characteristics. For instance, in some regions of Africa, community co-management projects have established management committees composed of community members, non-governmental organizations, government representatives, and experts to jointly make decisions on matters such as the daily management of protected areas, the development of eco-tourism, and environmental monitoring [12]. This participatory decision-making mechanism not only enhances the transparency and scientific nature of decision-making but also strengthens the sense of belonging and responsibility of community members. In terms of effect evaluation, researchers adopted a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to assess the impact of the co-management model on aspects such as biodiversity conservation, community economic development, and changes in social structure [13,14]. By establishing baseline data, conducting regular monitoring, and comparative analysis, they found that effective community co-management can significantly reduce destructive behaviors, such as illegal hunting and illegal logging, and promote the recovery of species diversity. The community co-management model can bring economic benefits to the community and improve the living standards of residents by developing green industries such as eco-tourism and sustainable agriculture. In addition, the co-management model has also promoted unity and cooperation within the community and enhanced the community’s ability to self-manage.

The roles, functions, and benefit distribution of community households. As the core stakeholders of the co-management model, the roles, functions, and benefit distribution of community households are directly related to the success or failure of co-management [15]. Research has shown that households are not only the direct users and managers of natural resources but also an important force in biodiversity conservation [16]. By participating in co-management, households can learn scientific methods of resource utilization and reduce the negative impact on the natural environment. Meanwhile, they can also obtain economic returns from conservation activities, such as eco-tourism revenue and ecological compensation funds, thereby stimulating their enthusiasm for protecting natural resources. However, the issue of benefit distribution often becomes the main challenge in the process of joint management. To ensure fairness and rationality, researchers suggest adopting multiple benefit distribution mechanisms [17], such as contribution-based reward systems and mutual fund management, to ensure that all participants can benefit from co-management. Furthermore, enhancing information transparency and regularly disclosing accounts and distribution situations are also key to strengthening trust and reducing conflicts.

Perception data and acceptance and satisfaction analysis. In order to gain a deeper understanding of the true feelings of community farmers towards the community co-management model, researchers widely used methods such as questionnaire surveys, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions to collect farmers’ perception data [18,19]. These data not only reflect households’ awareness of the co-management policy but also reveal their satisfaction and future expectations of the co-management effect. By analyzing these data, researchers can identify the strengths and weaknesses of the co-management model, providing a scientific basis for policy adjustment and optimization [20]. For example, some studies have found that although most farmers are satisfied with the economic benefits brought by co-management, there are still some farmers who are concerned that co-management may limit their traditional livelihood methods or feel dissatisfied with unfair resource allocation [21]. In response to these issues, researchers suggest strengthening communication and negotiation and developing more flexible and diverse co-management strategies to meet the needs and expectations of different farmers.

The empirical research and practical cases of community co-management in nature reserves in China provide rich experience and inspiration for this study. In China, the introduction of community co-management theory and practice is mainly due to the promotion of international aid projects. Since the 1990s, community co-management has gradually been applied as a new management model in areas such as poverty alleviation, rural development, and environmental protection [22]. Especially in the management of nature reserves, community co-management is regarded as an effective way to coordinate protection and community economic development. By drawing on successful experiences in community forestry, participatory poverty alleviation, and public resource management from abroad, China’s nature reserves have begun to explore community co-management models that are suitable for local communities [23].

In recent years, Chinese scholars have conducted extensive empirical research on community co-management in nature reserves. These studies mainly focus on the following aspects: firstly, analyzing the operational mechanism and implementation effects of the community co-management model [24]; the second is to explore the participation willingness and influencing factors of community farmers in the process of community co-management [25]; and the third is to evaluate the impact of community co-management on natural resource conservation, community economic development, and residents’ living standards [26]. For example, the community co-management practices in Baishuijiang Nature Reserve and Mengla Nature Reserve provide rich examples for understanding the application of community co-management in Chinese nature reserves. However, there are still some shortcomings in the current research in China. Firstly, the exploration at the theoretical level is relatively lagging behind, lacking a systematic construction of the theoretical system for community co-management. Secondly, empirical research often focuses on case analysis and lacks comparative studies across regions and types, making it difficult to form universal conclusions. In addition, there is severe competition for departmental interests, and most studies take the position of protected areas, lacking comprehensive consideration from the perspective of community households.

Although research on community co-management of nature reserves in China has achieved certain results, further deepening is still needed [27,28]. On the one hand, it is necessary to strengthen the research on community co-management theory and construct a theoretical system that is in line with China’s national conditions; on the other hand, the scope of empirical research should be expanded, and comparative studies across regions and types should be strengthened to improve the universality and practicality of research results. At the same time, more attention should be paid to the perception and needs of community households, and from their perspective, more scientific and reasonable community co-management models should be explored.

The main purpose of this study is to analyze the effectiveness of community co-management in promoting the sustainable development of nature reserves, taking Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve in China as an example. This study uses the Q methodology for empirical analysis in order to understand how community co-management balances protection and development, enhances economic self-sufficiency, and improves the well-being of local residents. This study can provide evidence-based recommendations for decision-makers to promote a more harmonious relationship between the protected areas and surrounding communities.

Another major objective of this study is to improve the understanding and participation of community families in ecological protection. The purpose of this study is to find out the factors affecting their participation in conservation activities by studying the cognition, attitude, and practical effect of community residents around Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve on community co-management. The results of this study are intended to provide information for the formulation of strategies to effectively involve local communities in ecological protection, thus contributing to the long-term sustainability of the reserve and improving the quality of life of residents.

2. Study Areas

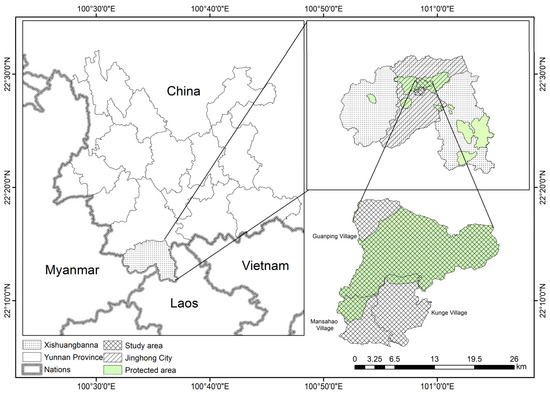

The Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve (XNNR) is located in the Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture in southern Yunnan Province, China. It has a unique geographical location (Figure 1), situated at 21°10′–22°24′ N latitude and 100°16′–101°50′ E longitude. This protected area consists of five disconnected sub-protected areas, including Mengyang, Mengla, Shangyong, Menglun, and Manfang, with a total area of 242,510 hectares, accounting for 12.68% of the Xishuangbanna city’s land area. As one of the most well-preserved and biologically rich regions in China’s tropical forest ecosystem, the XNNR is known as the “emerald on the crown of flora and fauna” and the “gene bank of tropical biological species”. The biodiversity within the protected area is extremely rich, covering a variety of rare wild animals and plants, especially the largest and most concentrated population of Asian elephants, as well as national key protected animals such as the north dolphin-tailed monkey and bison. In addition, the protected area also preserves a large number of tropical rainforest ecosystems, which are important bases for scientific research and ecotourism.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area.

However, the surrounding communities of the XNNR have relatively underdeveloped economies, inconvenient transportation, a small population, and low levels of education. Although there are co-management institutions between these communities and protected areas, harmonious development still faces many challenges. In order to achieve harmonious development between nature reserves and surrounding communities, local governments and relevant departments have taken a series of measures. On the one hand, they have strengthened the construction and management of nature reserves, improved protection mechanisms, and enhanced protection effectiveness; on the other hand, they are actively promoting community development, improving residents’ living conditions, and guiding community residents to participate in ecological protection. By establishing community co-management institutions, conducting ecological education and skills training, and providing ecological compensation, we can promote the transformation of production and lifestyle among community residents, achieving a win–win situation for ecological protection and economic development. In short, the XNNR and its surrounding communities are a region full of challenges and opportunities. By strengthening the combination of ecological protection and community development, achieving harmonious coexistence between nature reserves and surrounding communities can not only protect this unique treasure trove of biodiversity but also promote the sustainable development of the local economy and the improvement of residents’ living standards.

3. Methods and Data Sources

3.1. Q Methodology

Q Methodology is a mixed method for studying human subjectivity, which involves having participants rank or judge according to a set of declarative sentences and then collecting and analyzing this data to understand individual or group opinions, attitudes, motivations, perceptions, etc. The Q method emphasizes that participants should sort the declarative sentences themselves, which increases the intrinsic validity of this study, as it allows participants to directly express their opinions. Overall, the Q method provides researchers with a powerful tool for exploring human subjectivity in depth. The Q method has become a popular research method widely used by foreign scholars in the fields of nature reserves and community governance [29]. For example, it is used for policy evaluation to understand the different perspectives of stakeholders on the burning system in the northern Cape York Peninsula of Australia in order to adjust existing policies [30]; it is used for policy-making by analyzing stakeholder perspectives to find consensus that is conducive to developing policies that are more widely accepted, so Norway’s wildlife management policies receive maximum support [31]; it is used for decision optimization to improve the sustainable management of natural resources in the Mahong Forest in Perak, Malaysia [32]; it is used to resolve conflicts and alleviate conflicts among stakeholders in the participatory management process of Benin’s Panjaly National Park [33]; or it can be used to increase participation and analyze stakeholder attitudes and perspectives to enhance public participation in the governance of protected areas in Poland [34]. Chinese scholars have also used the Q method to explore the views of domestic experts in the field of nature conservation on the national park system [35].

Both social governance and public policy are faced with reflective individuals, and only by fully understanding their subjective views and cognition can the effectiveness of institutions and organizations be truly unleashed [36]. By analyzing the consensus and differences among stakeholders, we can more accurately grasp principles and directions, which is helpful for adjusting and implementing relevant policies. Therefore, in exploring the optimization of community co-management mechanisms, this study should pay attention to the perspectives of various stakeholders, which may be organically combined with the Q method.

3.2. Application of Q Methodology in This Study

3.2.1. Generating Research Topics

The optimization of the community co-management mechanism in this study was constructed primarily through three avenues: literature research, field research, and targeted interviews. Literature research delves into academic hotspots, policy documents, and news reports related to community co-management while also drawing insights from real-world cases of community co-management practices. Field research involves institutional discussions, visits, farmer survey questionnaires, and on-site residential observations, fostering a sensory understanding of nature reserves and community governance. This approach helps in comprehending the critical and challenging aspects of community co-management mechanisms’ construction and operation, leading to the design of targeted interview outlines (see Appendix A). During the targeted interviews, in-depth communication with various stakeholders captured their genuine perspectives on community co-management. Building on this research, 37 significant topics with universal relevance, research value, and high stakeholder interest were selected. These topics were articulated in declarative sentences to preliminarily establish a research statement set.

3.2.2. Develop Q-Set

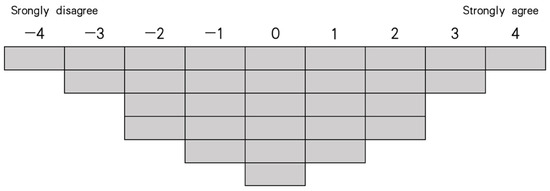

Based on the initial formation of the statement set, experts in nature conservation, staff from local protected area management agencies, and village committees were invited to offer optimization suggestions for the statements during field research. Statements with unclear meanings or redundant content were revised, and any missing content was added. During the interview process, two local villagers were selected to participate in this experiment, and the wording of certain sentences was tweaked to ensure there was no confusion after explanation by the interview organizer. Ultimately, the initial 37 statements were condensed into 30, which were then randomly numbered to create the Q-set (see Table 1). Q-sorting was based on a scale ranging from −4 (strongly disagree) to +4 (strongly agree) (see Figure 2). The 30 statements in the Q-set were filled in the corresponding cells of the scale by the respondents, forcing them to follow a quasi-normal distribution.

Table 1.

Q-set of this study.

Figure 2.

Q-sorting scale.

3.2.3. Determine Respondents (P Set)

Due to the uniqueness of the Q method, the empirical rule that a larger sample size is better may not necessarily be applicable. Although some studies have chosen larger P sets, satisfactory results can be obtained using small and targeted samples, so the general guiding principle is that the number of respondents in the P set is generally less than the number of statements in the Q-set [37]. In order to ensure a more targeted sample of respondents, priority should be given to selecting groups who have a basic understanding of policies related to nature reserves and communities, the construction of protected areas, and community co-management. In principle, it is necessary to facilitate communication during the research period, have sufficient time for interviews, and be willing to accept follow-up visits in the later stage of this research. Overall, it is important to cover a wide range of stakeholders. Therefore, the number of interviewees in the P set of this study was planned to be 20. However, in order to ensure the number of interviewees to be tracked and contacted in the later stage, and to prevent the effective sample size from being less than 20, 5 interviewees were added, for a total of 25 interviewees. The selection of interviewees adopted a combination of direct sampling and snowball sampling methods. Firstly, experienced leaders and staff from protected area management institutions were selected as interviewees. Then, through work contacts and professional knowledge recommendations, snowball sampling was used to identify additional interviewees. Participants were asked to recommend individuals who had direct experience with community co-management, represented different stakeholder groups, and were willing to share informed views on protected area governance. Since this process generated a larger pool of potential participants, the final P set was constructed by selecting the most suitable individuals based on the proportional representation of stakeholder categories, thereby ensuring diversity and balance in the sample.

The number and numbering of stakeholders covered by the P set are as follows, including 2 management personnel (GL1 and GL2) from the government and protected area management agencies, 1 professional and technical personnel (ZJ1), 3 grassroots protection station leaders or staff (JC1, JC2, and JC3), 3 community leaders (managers) (LW1, LW2, and LW3), and 6 villagers with significant differences in production and lifestyle (CM1, CM2, CM3, CM4, CM5, and CM6), 1 staff member from a scenic tourism enterprise, 1 homestay owner, and 1 restaurant owner (JQ1, MS1, and CG1), 2 responsible persons from enterprises (or cooperatives) that operate ecological products (QY1 and QY2), 2 staff members from relevant social organizations (SG1 and SG2), 1 expert and scholar (XZ1) whose research direction is related to nature reserves and community governance, and 1 graduate student (XS1 and XS2) majoring in agricultural and forestry economic management and public management. Based on field research, except for social organization staff, expert scholars, and graduate students, other data were selected from the main research areas of Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve in Yunnan province. Communities within XNNR were selected for three reasons: (1) selecting several communities within one protected area makes data collection easier; (2) XNNR started early in establishing and reforming the reserve system; and (3) it has encountered numerous difficulties and complex situations in protected area and community management, accumulating ample experience. As early as 1997, XNNR formulated the “Community Co-management Action Plan of XNNR”, “Community Co-management Charter”, and “Responsibilities of Leadership Group Members and Coordinators” with local communities, which were implemented in Jinghong and Mengla, respectively. Therefor XNNR has typical and representative charac-teristics nationwide. For graduate students who have joined the agricultural and forestry economic management and public management majors in the P concentration, they are mainly set up as peripheral stakeholders to understand knowledge related to protected areas and community governance.

3.3. Data Sources and Analysis

3.3.1. Data Sources

The data collection was mainly conducted through face-to-face interviews in the XNNR in Yunnan Province. First, introduce the purpose and expected duration of the interview (about 40–60 min) to the interviewee, obtain permission for recording, and inquire about and record the interviewee’s basic information; second, present the Q-set to the interviewee, introduce the Q-sorting steps, and guide the interviewee to roughly and evenly divide the statements into three categories: agreement, general, and disagreement, and then fill in the Q-sorting scale; finally, communicate and discuss with the interviewee about the “three statements that they most agree with and least agree with”, “what suggestions do you have for this study”, and “whether there were any difficulties encountered during the sorting process”. During the interview process, considering the dialect habits of some respondents, this study sought the help of individuals who are proficient in the local dialect and have good Mandarin proficiency to translate. Although the Q method interview process is usually conducted face-to-face, it can also be performed through mail or online methods for convenience [38]. Therefore, some respondents’ Q rankings were conducted online, mainly using online questionnaire filling. Prior to data analysis, some interviewees were also interviewed by phone to supplement some content. Due to the failure of a social organization worker (SG1) to provide qualified Q-ranking data, this study ultimately obtained 24 valid data, meeting the initial requirements of the research design.

3.3.2. Data Analysis

The data analysis of Q method can be completed using numerous programs and tools, including mainstream software such as PQMethod, PCQ, qmethod package for R, Ken-Q Analysis, etc. Among them, the Q method series of software developed by Banasick has simpler operation, including online software Ken-Q Analysis [39], its desktop counterpart KADE [40], and other supporting tools. Ken-Q Analysis brings the interactivity and convenience of the web into the Q method and realizes browser-based online data processing. Therefore, this study used Ken-Q Analysis (version 2.0.1) to analyze the data, which automatically and conveniently processed the data online and generated key graphs.

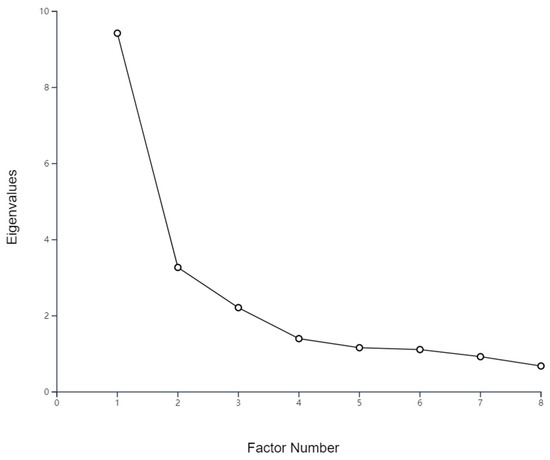

The essence of the analysis process is the inverted principal component analysis (PAC) method, which creates components based on the interviewee rather than declarative statements. Using Ken-Q Analysis (Version 2.0.1), first start by analyzing the correlation between each respondent’s Q-sorted data and all other respondent’s Q-sorted data and automatically generate a correlation matrix for the respondent’s Q-sorted data. Then output a table of eigenvalues for each factor (Table 2. Eigenvalues and Explained Variance for Factors) and a scree plot (Figure 3. Scree Plot Showing the Eigenvalues of Factors) by automatically performing a principal component analysis on the correlation matrix.

Table 2.

Eigenvalues and explained variance for factors.

Figure 3.

Scree plot showing the eigenvalues of factors.

In the stage of selecting the factors to be retained, it is mainly determined based on the classical PCA method, taking into account the reference eigenvalues, the total amount of variation explained, and the scree plot. Although Factor 5 and Factor 6 can also be theoretically adopted according to the prevailing Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue λ > 1), there is a significant drop in eigenvalues between Factor 4 and Factor 5, and the eigenvalues of Factors 5 and 6 are only slightly above 1. Thus, their ability to explain additional variation is relatively limited, and they were not retained in the final model. Considering the interpretability of the factors and the need to ensure that the final result is neither overly complex (with too many perspectives) nor overly simplified, while also reflecting the realities observed during field research as accurately as possible, this study ultimately retained the first four factors. Finally, the variance rotation method (Varimax) commonly used by most scholars [29] was selected for analysis, and a factor loading table arranged according to the respondents was obtained (Appendix B). At a 95% confidence level, the load of the respondents is automatically labeled in each factor. The subsequent steps are automatically carried out by the software, and the results are recorded. The final output includes a series of tables containing the results of each stage for analysis and presentation reporting. Based on the results, the respondents marked in each factor are as follows: Factor 1—GL2, JC2, CM5, MS1, and QY1; Factor 2—LW1, LW2, CM1, CM2, CM6, SG2, and XS1; Factor 3—ZJ1, JC1; Factor 4—GL1, JC3, CM3, QY2, and XZ1. These respondents are considered the most representative of that factor’s viewpoint.

4. Results

4.1. Determine and Describe Viewpoints

Table 3 shows the main characteristics of the four selected factors, with a total of 68% of the variance explained. The percentage of variance explained by other similar articles is mostly at a similar level: 65% [41], 66.48% [42], and 67% [43]. The overall comprehensive reliability is high (above the critical value of 0.8).

Table 3.

Main characteristics of selected factors.

By summarizing and organizing the data analysis results of each stage, a comprehensive Q-ranking table (Appendix C) was obtained, which displays the significance (or “distinctiveness”) and ranking of each statement in each viewpoint. Based on the qualitative data collected during field research and Q-method interviews, this study identifies a summary name for each viewpoint that is related to its main characteristics and explains and discusses each viewpoint. In the interpretation process, particular attention was given to the three highest- and lowest-ranked statements for each viewpoint, as they reflect the strongest agreement and disagreement within that discourse, respectively. Additionally, statements identified as statistically significant were emphasized, as they represent the highest level of resonance among the defining sorts for that viewpoint. Each viewpoint was then described by integrating the analytical results with qualitative insights gathered during field research.

Seize the opportunity and drive local development through community co-management

This viewpoint is the most strongly felt among the interviewees, characterized by their indifference to the impact of introducing enterprises into the communities surrounding protected areas on the coordinated development of the local economy, society, and ecology (6, 30, **)2. They recognize the positive role of various industrial development projects in community co-management in effectively driving employment and entrepreneurship among community residents (4, 28). Many respondents who hold this view have already benefited from community co-management and now hope to seize current development opportunities. This includes protecting and inheriting the local community’s characteristic cultural traditions (2, 1, **), creating distinctive brands, developing unique industries, and integrating community co-management with the current rural revitalization strategy (14, 3). They are actively involved in the construction and development of their hometowns.

While this group holds an open and welcoming attitude towards the involvement of market entities in the development of protected areas and communities, they do not believe that non-governmental entities can lead the governance of natural protected areas and communities in the current environment (10, 29). However, they strongly agree that the government should delegate some power to entities such as enterprises and social organizations during community co-management (5, 2, *). They believe that enterprises and social organizations can handle some issues better than the government and that community affairs can achieve autonomy and self-determination through resident empowerment. In addition, they hope the government can introduce more preferential policies, continuously optimize the business environment of protected communities, guide the development of a green economy, and vigorously support civil society organizations, volunteer service groups, and scientific research teams to carry out activities in protected areas and communities.

People-oriented and valuing the well-being of community residents in protected areas

The most prominent feature of this viewpoint is the greater emphasis on the well-being of community residents in protected areas. Although the respondents who hold this view did not question the effectiveness of community co-management, the vast majority did not benefit much from it. On the one hand, it is strongly believed that the rights and interests of the community and residents have been neglected in the process of community co-management and construction (7, 3, **). Although there is a strong willingness to participate (8, 26, **), the relevant systems and legal protections are not perfect (16, 4, **), and the participation of community residents in grassroots governance of protected areas has not been effectively achieved. In the current situation, there is still a long way to go to promote the realization of community democracy through the concept of “co governance” of community co-management (22, 28). In addition, the lack of excellent resource endowments and development opportunities in the local area is also an opportunity to achieve effective co-management (19, 25, **). On the other hand, more attention is paid to immediate economic interests, and it is strongly recommended that joint management projects prioritize infrastructure construction to ensure a decent life for community residents (11, 1, **). It is hoped that the community and its residents will be regarded as an organic part of nature reserves (1, 2). In reality, some villages are unable to build or upgrade roads due to strict restrictions on protected areas, which affects the travel of villagers and makes it difficult to attract tourists for tourism development. The ecological agricultural products grown in these villages cannot be transported out; without new homesteads, old houses cannot be renovated, and new houses cannot be built; the whole village even has no construction land available for building public facilities, which has led to the outflow of young people, severe aging, and the gradual decline of the village. The wild animals in the protected area breed rapidly under good protection, while wild boars and other wild animals indiscriminately invade farmland and even cause conflicts between humans and animals. However, the compensation received by residents is difficult to cover the losses (28, 30). In addition, their views on the protected areas they live in are more inclined to believe that the higher the level and larger the scale of the protected areas, the more effective co-management can be achieved (20, 29), especially after the first batch of national parks were officially established, and they are more supportive of integrating their own protected areas into national parks. After gaining a higher level and greater fame, the village may be able to plan and construct or relocate uniformly, with greater financial support and compensation. Their daily living conditions will be better, and they will benefit more from it.

Emphasize the issue and call for the system to deeply promote reform

The prominent feature of this viewpoint is that it pays more attention to the practical problems faced by community co-management and hopes to carry out a more systematic reform of community co-management from the perspective of governance (29, 27, *). Respondents who hold this view sharply pointed out that a considerable portion of the current community co-management construction in nature reserves exists to meet the requirements of relevant national policy documents and is not truly community co-management. Instead, other existing management models or construction projects are packaged as community co-management and even promoted as achievements. To solve this series of problems, determining the positioning of the community co-management committee (or similar organization) is a starting point, by building a sound system to ensure its proper role (13, 1, **) while granting it corresponding powers. They stated that the implementation efficiency of community co-management projects is generally low, and the problem of form being greater than content (25, 3, **) can be partly attributed to the government’s behavioral logic. In most nature reserves, non-governmental entities generally do not have the ability to lead the governance of nature reserves and communities (10, 28), and the government remains the primary entity leading the work. As the largest investor, the government does not have the driving force to promote community co-management in the face of huge investment and uncertain outputl after all, there are no clear assessment constraints. The biggest problem in the difficulty of community co-management construction generally lies in funding (15, 2), which is often confirmed in scenarios where other funding sources outside the government are needed for support. The proportion of community residents who suffer losses due to reasons related to protected areas through government funding compensation is even smaller, and residents find it difficult to be satisfied with the compensation they receive (28, 30). So, relying solely on a government-centered governance model is neither realistic nor sustainable. Starting from the system and deepening reform is the breakthrough point to solve current problems. By clarifying the division of responsibilities among various governance entities, promoting the healthy development of protected areas and community governance, and providing a favorable environment for the coordinated development of local economy, society, and ecology, effective community co-management can be achieved. At the same time, some respondents also pointed out that although community co-management is helpful in resolving conflicts between protected areas and communities, attention should also be paid to the new divisions and conflicts that may arise within the community during this process (30, 29, **). For example, elite groups such as government officials, village officials, and local business leaders often have greater say in community co-management, can access more information and influence decision-making, and have an advantage over ordinary residents, leading to unequal development opportunities and wealth inequality.

Be content with the status quo and believe and expect the government to take action

The prominent feature of this viewpoint is that the concept is more traditional and conservative, content with the status quo, and more willing to believe in and support the government. Respondents who hold this view do not doubt that equal cooperation and joint governance among diverse entities is the future of community governance but firmly believe that government leadership is more in line with current reality (26, 3, **) and believe that overall, non-governmental entities may not be able to do better than the government in the governance of nature reserves and communities (10, 30). Individual respondents pointed out that there are no distinctive resources in their community that can be explored to drive economic development. Most residents have low cultural levels and lack vocational skills and have been mainly engaged in traditional agricultural production. In recent years, the government has created many job opportunities such as patrol officers through community co-management and some project construction, which has brought tangible benefits to community residents. People have a stronger sense of identity with protected areas and gradually see themselves as part of nature reserves (1, 1), willing to participate in ecological protection work and community governance of protected areas. Although many residents are not satisfied with the compensation they receive due to reasons related to protected areas (28, 29), it is still better than before. Especially now, community co-management committees (or village committees) are very concerned about community affairs (13, 28, **), such as actively helping residents apply for compensation when encountering incidents involving wild animals. Respondents believe that while financial security is important, it is not a necessary condition for achieving effective community co-management (15, 26, **) and that happiness and a sense of gain are not entirely linked to money. In addition, respondents who hold this view are full of expectations for the organic combination of community co-management and rural revitalization (14, 2), hoping that national policies can be implemented and life can become better and better under the leadership of the government.

4.2. Consensus and Differences Among Stakeholders

Conducting consistency analysis on the statements in the Q ranking of various viewpoints and sorting them according to the size of the results (Appendix D) can observe the consensus and divergence between different viewpoints. On the one hand, respondents generally believe that the current community co-management mechanism requires good institutional guarantees, and the most significant consensus is that community co-management activities should be subject to comprehensive internal and external supervision (12, 1, *). Therefore, it is necessary to establish an effective supervision mechanism, especially to pay attention to the rights and interests of the community and residents, ensure smooth internal supervision channels, and thus improve the enthusiasm of the community and residents to participate in co-management, as well as to establish a more transparent information disclosure mechanism (23, 2, *) to enable residents of protected areas and various sectors of society to understand the situation of community co-management and fund utilization and promote information and data sharing among collaborative units. On the other hand, respondents pointed out that there are abundant practical cases of community co-management in China, but there is insufficient theoretical research (21, 3). Community co-management has been practiced in China for 30 years, and how to summarize the experience, explain the essence of its concept of “co construction, co governance, and sharing”, and reconstruct it under the current national governance theory system is an urgent problem that needs to be solved in the theoretical community. In addition, most respondents also called for accelerating the construction of a nature reserve system with national parks as the main body, further integrating nature reserves to achieve more effective co-management (20, 4).

The differences in opinions held by the interviewees are greatly influenced by their respective living environments, educational levels, and subjective judgments, and there are no obvious identity characteristics. Taking the three most divergent issues as examples, they are the positioning and role of community co-management committees (or similar organizations) (13, 30), the impact of funding on community co-management construction (15, 28), and the execution efficiency of community co-management projects (25, 29). This indicates that in the process of promoting community co-management construction, the above issues are more likely to cause controversy and need to be resolved more cautiously in order to seek maximum cooperation from stakeholders. For such highly divergent issues, it is often necessary to analyze the specific problems based on differences in regional economic levels, joint management projects, and government governance concepts, and solve them according to local conditions.

5. Discussion

This study takes the Xishuangbanna National Nature Reserve as a case for in-depth analysis. It not only comprehensively examines the views and attitudes of residents around the reserve on the community management model but also reveals many profound insights, enriching the existing knowledge system and theoretical framework.

This study makes significant theoretical contributions to the existing literature on community co-management. It deepens the understanding of the role of community co-management in promoting local sustainable development by emphasizing its potential to drive employment, entrepreneurship, and economic self-sufficiency. This study highlights the importance of residents’ well-being as the core value of community co-management, shedding light on practical difficulties faced by community residents in participating fully. Furthermore, it advances the discourse on system reform as the key to fostering the in-depth development of community co-management, proposing measures such as clarifying organizational positioning, optimizing government behavior, and diversifying funding mechanisms. By integrating these insights, this study not only enriches the theoretical framework of community co-management but also provides practical guidance for policymaking and implementation in protected areas worldwide.

This study confirms the effectiveness of community co-management in promoting local economic prosperity, social harmony, and ecological conservation, which is consistent with previous research findings [44]. However, it further emphasizes the critical role of community co-management in stimulating local development potential and creating new opportunities. This not only deepens our understanding of participatory community management models but also provides a new perspective for exploring sustainable development models at the local level. This study found that the view of “seizing opportunities and promoting local development through community co-management” resonated strongly with respondents, aligning with some existing literature while presenting a fresh perspective. The literature generally highlights community co-management as a balanced tool for protection and development, capable of achieving local economic and ecological goals [45,46]. This study further points out that community co-management serves both as a passive adaptive strategy and an active mechanism for seizing opportunities and fostering distinctive local development. What sets this study apart is its emphasis on the close integration of respondents ‘attention to cultural heritage preservation, brand building, and rural revitalization strategies, reflecting new directions and requirements for community development under China’s current policy context. Additionally, this study reveals respondents’ expectations for a shift in government roles, where the government should delegate some powers to businesses and social organizations, aligning with the multi-center governance concept emphasized in the literature [5]. However, in terms of specific implementation paths such as policy support and business environment optimization, it is more in line with the actual situation of the research region.

This study emphasizes the core value of enhancing residents’ happiness in community co-management practices, which is often marginalized or overlooked in other studies. In fact, it is an indispensable component in measuring the effectiveness of community management [14]. By delving into the specific challenges and difficulties faced by community residents, this study highlights the complexity and multifaceted nature of community co-management practices in improving people’s well-being [47], providing a deeper perspective on understanding the challenges and opportunities of community co-management practices. This research’s “people-oriented approach, emphasizing the well-being of residents in protected area communities” aligns with the core concept of many documents, which states that community co-management should focus on improving residents’ quality of life [48]. However, this study further reveals the practical difficulties faced by community residents during participation, such as insufficient institutional support and inadequate channels for involvement. Although these issues have been mentioned in the previous literature, this study enhances their visibility and urgency through concrete cases and data. This study points out residents’ concerns about infrastructure construction and economic benefits, contrasting with some documents that solely emphasize ecological protection, highlighting the balance between economic, social, and ecological aspects in community co-management [49]. Respondents’ expectations for the inclusion of high-level protected areas in national parks also reflect residents’ desire for higher levels of protection and development opportunities under China’s unique policy background.

This study directly addresses the urgent need for reform in protected area management systems, particularly the practical issues related to wildlife damage compensation, which have rarely been thoroughly discussed in the previous literature. This study emphasizes the perspective of “highlighting problems and calling for systematic and profound reforms”, aligning closely with the exploration of challenges and solutions faced by community co-management in the literature [50]. However, this study specifically identifies formalism, low implementation efficiency, and financial dependence as issues in current community co-management and delves into the underlying reasons behind government behavior logic, areas that are seldom addressed in the previous literature. It is suggested to start with institutional reform and establish a comprehensive system of institutional guarantee to clarify the responsibilities among various governance subjects. This suggestion is in line with the goal of promoting the modernization of global governance systems [51]. However, this study highlights the unique characteristics of China’s national conditions, such as the shift in government dominance and the increased role of non-governmental actors, providing valuable references for applying international experiences in China.

This study also reflects some negative attitudes among stakeholders towards community co-management. Some stakeholders and farmers in nature conservation areas hold negative attitudes toward community-based co-management, a phenomenon that conceals multiple complex reasons. First, insufficient economic compensation is undoubtedly the most direct and pressing issue. Many farmers and residents feel that the financial assistance provided by the government or conservation agencies falls far short of compensating for the various restrictions imposed on their daily land use, agricultural production, and living activities due to the implementation of protective measures. This economic imbalance leaves them lacking the motivation and enthusiasm to participate in co-management. Secondly, the operational inefficiencies of community-based co-management are also a significant factor contributing to negative attitudes. The lack of transparency in decision-making processes and the absence of guidance and coordination mechanisms often make local communities feel marginalized and unable to truly participate in the planning and management of protected areas. This sense of frustration further diminishes their willingness to engage. Finally, the unfair distribution of benefits adds fuel to the fire. When the economic gains from conservation efforts fail to fairly benefit all stakeholders, discontent and resentment spread through the community, making the vision of shared management even harder to achieve. These intertwined issues not only erode the trust within the system but also inadvertently intensify conflicts and tensions among various parties.

Based on the above analysis, this study shares similarities and differences with the existing literature in multiple aspects. These similarities and differences not only enrich our understanding of community co-management practices in China’s national nature reserves but also provide new perspectives and directions for future research. Future studies can further explore how to promote community co-management from form to substance at the policy level and how to build more equitable and effective participation mechanisms, ensuring that community residents truly benefit from both conservation and development. At the same time, as the rural revitalization strategy deepens and the national park system is established, how to transform these policy benefits into practical impetus for community co-management is another issue that requires further research. Additionally, interdisciplinary research methods, such as integrating knowledge from sociology, economics, ecology, and other fields, will help reveal the complexity and diversity of community co-management more comprehensively, providing theoretical support for formulating more scientifically sound policies.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Community co-management is an effective path to promote local sustainable development. This study indicates that community co-management, as an innovative management model for protected areas, has great potential to promote coordinated development of the local economy, society, and ecology. The respondents generally agree that community co-management can not only effectively drive employment and entrepreneurship among community residents and achieve economic self-sufficiency and growth through the development of characteristic industries and brands but also organically combines the goals of protection and development, making protected areas a new engine for rural revitalization. This model not only alleviates the contradiction between protection and development but also enhances the community residents’ sense of identity and participation in nature conservation. In the future, we should further explore and improve the policy system of community co-management, ensure that the interests of all parties are taken into account, especially increase support for community co-management projects, optimize the business environment, guide the development of a green economy, and inject strong impetus into local sustainable development.

Strengthening residents’ well-being is the core value of community co-management. This study emphasizes that putting people first and valuing the well-being of community residents in protected areas is an indispensable part of community co-management work. Although community co-management is widely recognized at the theoretical level, in practical operation, some community residents have not fully enjoyed the benefits brought by co-management. This highlights the shortcomings of the current joint management mechanism in safeguarding residents’ rights and participation. Therefore, in the future, community co-management work should pay more attention to institutional design and legal protection, ensuring that the rights of community residents to know, participate, and benefit are fully respected. At the same time, we need to increase investment in infrastructure construction, improve residents’ living conditions, and reduce the negative impact of protection policies. In addition, it is necessary to actively build a harmonious symbiotic relationship between communities and protected areas so that residents can become an important force in nature conservation and share the fruits of protection and development.

System reform is the key to promoting the in-depth development of community co-management. This study points out that the current community co-management work faces many practical problems and challenges, such as formalism, low efficiency, and insufficient funding, which seriously restrict the in-depth development of co-management work. Therefore, it is necessary to start from the institutional level and carry out systematic and in-depth reforms. Firstly, it is necessary to clarify the positioning and responsibilities of community co-management organizations, establish a sound institutional system, and ensure their effective operation. Secondly, it is necessary to optimize the logic of government behavior, enhance the initiative and enthusiasm of the government to promote community co-management, and avoid treating co-management work only as a performance project. At the same time, we should actively explore diversified funding mechanisms to alleviate government financial pressure and improve the efficiency of fund utilization. Finally, it is necessary to strengthen supervision and evaluation, establish a scientific assessment system, and ensure the effectiveness of community co-management work. These measures promote the healthy development of protected areas and community governance and provide strong guarantees for the coordinated development of the economy, society, and ecology.

Community co-management is a proven path towards fostering local sustainable development. Building on the findings of this study, we propose three specific action plans to enhance community involvement and coordination in protected areas:

Strengthening community engagement and capacity building to fully realize the benefits of community co-management is crucial to actively engage residents and build their capacity. This can be achieved through regular community meetings, workshops, and training programs that educate residents on the importance of conservation, entrepreneurship, and sustainable development practices. Additionally, establishing community-led initiatives and volunteer programs can boost local ownership and participation in conservation efforts. Implementing a comprehensive policy framework and legal protection. Ensuring a robust policy framework that includes legal protection for community rights and interests is essential. This involves developing clear guidelines and regulations that outline the rights, responsibilities, and benefits of community residents in protected areas. Strengthening institutional design and legal protection will ensure that communities have a voice in decision-making processes and can effectively benefit from co-management initiatives. Foster partnerships and diverse funding mechanisms. Promoting partnerships between community groups, local governments, non-governmental organizations, and private sectors can drive innovation and resource mobilization. Establishing diverse funding mechanisms, such as grants, loans, and crowdfunding platforms, can alleviate financial constraints and ensure sustainable funding for community co-management projects. These partnerships and financial supports should be targeted towards infrastructure development, green economy projects, and community well-being programs.

6.2. Policy Implications

The results of this study have important practical significance for policymakers, community leaders, and other stakeholders in the protected areas. First, for policymakers, the findings of this study provide valuable insights and information for formulating effective protection policies. Understanding the unique challenges and needs of protected areas can help decision-makers develop targeted measures to solve these problems. This may include allocating more resources for monitoring and law enforcement, implementing community-based protection plans, or developing strategies to involve local residents in protection efforts. For community leaders, the findings highlight the importance of building strong partnerships between local communities and protection authorities. Community leaders can use this information to advocate for greater participation in the decision-making process and benefit from conservation initiatives. By doing so, they can help ensure the sustainability of conservation efforts and ensure that local communities are not adversely affected. In addition, community leaders can use these findings to raise awareness and educational programs to highlight the benefits of protected areas for local livelihoods and the environment. Other stakeholders, such as non-governmental organizations and private sector entities, can also derive practical significance from the findings. Non-governmental organizations can use this research to prove the rationality of fund application and design more effective protection projects to solve the identified problems. Private sector stakeholders, including tourism operators and enterprises, can adjust their businesses to better support protection objectives. This may include adopting a sustainable approach, supporting community development projects, and participating in corporate social responsibility initiatives in favor of protected areas. In a word, the research results provide a road map for policymakers, community leaders, and other stakeholders to strengthen the protection of protected areas. By addressing the unique needs and challenges of these regions, stakeholders can work together to create a more sustainable and resilient future for mankind and the environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.; methodology, A.L.; formal analysis, C.W.; investigation, C.W. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the China–Africa Cooperation Research Project of the China–Africa Institute (Project Number: CAI-J2023-01) and the Key Project of the Research and Interpretation Project of Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Project Number: 2025XYZD02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study used micro-level survey data collected with participants’ informed consent. According to Article 32 of China’s Ethical Review Measures for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Humans (issued by National Health Commission et al.)3, this research is exempt from ethical approval as it involves no harm to participants, sensitive personal information, or commercial interests.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Outline of Interview on Community Co-management of Nature Reserves

0. Prepare.

Thank the interviewee’s participation and for providing relevant information.

Prepare interview environment and debug recording equipment.

Inquire and record the basic information of the interviewee.

1. Understanding of community co-management in nature reserves.

Do you know about community co-management or similar concepts?

What elements do you think the definition of community co-management should include?

How do you understand the significance of community co-management in the context of national park system reform?

2. The model of community co-management in nature reserves.

Have you participated in community co-management or related projects?

What is your understanding of community co-management models for nature reserves?

What do you think are the differences between different community co-management models?

What do you think are the new changes in the current focus of community co-management compared to before?

3. The operational mechanism of community co-management in nature reserves.

Has your organization had or currently has there been any community co-management or related projects in the past or present?

What operational mechanisms do you think community co-management involves?

Please provide a detailed introduction to the operating mechanism you are familiar with.

4. Practice of community co-management in nature reserves.

Please share successful (or failed) cases of community co-management that you have participated in or learned about and explain the reasons for their success (or failure).

What factors do you think are key to ensuring successful community co-management of nature reserves?

Please share your experience and lessons learned in promoting community co-management projects.

5. Evaluation of community co-management in nature reserves.

What stakeholders do you think community co-management involves? Which group do you belong to?

Do you think community co-management would help your interests and demands?

What do you think is the important significance of community co-management for the governance of nature reserves and communities?

6. Prospects for community co-management of nature reserves.

What do you think can be improved in the current community co-management?

What do you think is the future direction of community co-management?

What suggestions do you have for promoting and building community co-management?

7. Summary.

Confirm that all questions have been answered seriously by the interviewee.

Ask the interviewee if there are any additional supplements and explanations.

Express gratitude to the interviewee and provide compensation.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Factor Loadings Table.

Table A1.

Factor Loadings Table.

| No. | Q Sort | Factor 1 | Flagged | Factor 2 | Flagged | Factor 3 | Flagged | Factor 4 | Flagged |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GL1 | 0.545 | −0.0002 | −0.1597 | 0.6764 | √ | |||

| 2 | GL2 | 0.7476 | √ | 0.1216 | 0.3448 | 0.0213 | |||

| 3 | ZJ1 | 0.187 | 0.0547 | 0.8682 | √ | −0.0302 | |||

| 4 | JC1 | 0.2882 | 0.2836 | 0.7288 | √ | 0.1921 | |||

| 5 | JC2 | 0.641 | √ | 0.3334 | 0.0941 | 0.197 | |||

| 6 | JC3 | −0.0486 | −0.1343 | 0.3736 | 0.7408 | √ | |||

| 7 | LW1 | 0.2414 | 0.7447 | √ | 0.0179 | −0.0501 | |||

| 8 | LW2 | 0.1791 | 0.7407 | √ | 0.0877 | 0.2955 | |||

| 9 | LW3 | 0.5336 | 0.5659 | −0.1202 | 0.2546 | ||||

| 10 | CM1 | −0.1127 | 0.7815 | √ | 0.4 | −0.2595 | |||

| 11 | CM2 | 0.1402 | 0.6056 | √ | 0.3098 | 0.2688 | |||

| 12 | CM3 | 0.3127 | 0.2775 | −0.022 | 0.4565 | √ | |||

| 13 | CM4 | 0.6194 | 0.4954 | −0.2995 | 0.3336 | ||||

| 14 | CM5 | 0.6463 | √ | 0.178 | −0.0021 | 0.2339 | |||

| 15 | CM6 | −0.1246 | 0.67 | √ | 0.4863 | 0.1915 | |||

| 16 | JQ1 | 0.9007 | √ | 0.1232 | 0.061 | 0.207 | |||

| 17 | MS1 | 0.6066 | √ | 0.4493 | −0.0329 | 0.2284 | |||

| 18 | CG1 | 0.4121 | 0.4111 | 0.1864 | −0.0009 | ||||

| 19 | QY1 | 0.8767 | √ | 0.0107 | 0.1499 | 0.1531 | |||

| 20 | QY2 | 0.5115 | 0.1692 | 0.1504 | 0.5736 | √ | |||

| 21 | SG2 | 0.505 | 0.6126 | √ | −0.1423 | −0.0063 | |||

| 22 | XZ1 | 0.391 | 0.2765 | −0.3166 | 0.6569 | √ | |||

| 23 | XS1 | 0.2851 | 0.6899 | √ | −0.2104 | 0.0656 | |||

| 24 | XS2 | 0.5955 | 0.1977 | −0.5603 | 0.3901 | ||||

| explained variance | 25% | 20% | 11% | 12% | |||||

Note: When using Ken-Q Analysis (Version 2.0.1) for data analysis, select Varimax to extract and rotate important factors and automatically mark the resulting factor loadings (√).

Appendix C

Table A2.

Comprehensive Q-Ranking Table.

Table A2.

Comprehensive Q-Ranking Table.

| No. | Statement | Perspective I | Perspective II | Perspective III | Perspective IV | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Score | Rank | Z-Score | Rank | Z-Score | Rank | Z-Score | Rank | ||||||

| 1 | Communities and their residents should be regarded as an integral part of nature reserves | 1.36 | 4 | 1.83 | 2 | 0.56 | * | 10 | 1.91 | 1 | |||

| 2 | Community co-management must protect and inherit the unique cultural traditions of the local community | 1.74 | ** | 1 | 0.56 | * | 10 | −0.22 | 19 | −0.39 | 22 | ||

| 3 | Community co-management must meet the demands of different stakeholders | −1.03 | 26 | 0.28 | 13 | −0.56 | 22 | 0.23 | 14 | ||||

| 4 | Community co-management is difficult to effectively drive employment and entrepreneurship among community residents | 1.42 | 28 | −0.26 | 17 | 0.39 | 11 | −0.92 | 24 | ||||

| 5 | In the process of community co-management, the government can delegate some power to entities such as enterprises and social organizations | 1.71 | * | 2 | −0.21 | * | 16 | 0.78 | 7 | 0.46 | 9 | ||

| 6 | It is difficult to achieve coordinated development of local economy, society, and ecology by introducing enterprises into the surrounding communities of protected areas | −1.86 | ** | 30 | −0.47 | 19 | −0.17 | 17 | −0.11 | 17 | |||

| 7 | The rights and interests of the community and residents have been neglected in the process of community co-management construction | −0.56 | 20 | 1.51 | ** | 3 | −0.95 | 25 | −0.37 | 21 | |||

| 8 | Community residents should participate in co-management decision-making indirectly | 0.52 | 10 | −0.98 | ** | 26 | 0.05 | 13 | 0.47 | 8 | |||

| 9 | Local governments have the motivation to actively promote community co-management construction | −0.26 | 19 | −0.81 | 24 | −0.73 | 23 | 0.29 | 12 | ||||

| 10 | Non governmental entities can take the lead in the governance of nature reserves and communities | −1.65 | 29 | −0.06 | ** | 15 | −1.69 | 28 | −1.84 | 30 | |||

| 11 | Community co-management projects should prioritize infrastructure construction to ensure a dignified life for community residents | 0.89 | * | 6 | 2.05 | ** | 1 | −0.22 | 20 | 0.21 | 15 | ||

| 12 | Community co-management activities should be subject to comprehensive internal and external supervision | 0.48 | 11 | 0.77 | 8 | 0.34 | 12 | 0.90 | 5 | ||||

| 13 | The community co-management committee (or similar organization) has a vague positioning and limited role to play | −0.69 | 22 | −0.60 | 23 | 1.56 | ** | 1 | −1.59 | ** | 28 | ||

| 14 | Community co-management and rural revitalization can be organically combined | 1.57 | 3 | 0.79 | 7 | 1.30 | 4 | 1.85 | 2 | ||||

| 15 | The biggest problem when community co-management construction is difficult usually lies in funding | 0.48 | 12 | 0.88 | 5 | 1.52 | 2 | −1.22 | ** | 26 | |||

| 16 | There is no complete system and legal guarantee for community co-management | −0.21 | 17 | 1.11 | ** | 4 | −0.17 | 18 | −0.33 | 20 | |||

| 17 | The key to the construction of entrance communities and characteristic towns is to mobilize the enthusiasm of stakeholders | 1.08 | 5 | 0.29 | 12 | 0.73 | 8 | 1.47 | 4 | ||||

| 18 | Community co-management adheres to the problem orientation, adapts measures to local conditions, and is unable to form a unified model that can be widely promoted | 0.26 | 13 | −1.04 | ** | 27 | 0.05 | 14 | 0.25 | 13 | |||

| 19 | Only regions with certain resource endowments and development potential can effectively implement community co-management | 0.82 | 7 | −0.88 | ** | 25 | 0.69 | 9 | 0.41 | 11 | |||

| 20 | The higher the level and larger the scale of nature reserves, the more difficult it is to achieve effective co-management | −0.88 | 24 | −1.44 | 29 | −0.95 | 26 | −0.51 | 23 | ||||

| 21 | There are abundant practical cases of community co-management in China, but there is insufficient theoretical research | 0.80 | * | 8 | 0.04 | 14 | 0.00 | 15 | 0.11 | 16 | |||

| 22 | Community co-management can promote the realization of community democracy | −0.21 | 18 | −1.07 | 28 | −0.78 | 24 | −0.23 | 18 | ||||

| 23 | Community co-management must establish a more transparent information disclosure mechanism | 0.59 | 9 | 0.73 | 9 | 0.00 | 16 | 0.45 | 10 | ||||

| 24 | It is often inadequate for the implementation of community co-management policies at the grassroots level | −0.63 | 21 | 0.81 | 6 | 1.30 | 5 | −1.03 | 25 | ||||

| 25 | The execution efficiency of community co-management projects is generally not high, and the form is greater than the content | −0.91 | 25 | 0.45 | ** | 11 | 1.52 | ** | 3 | −1.33 | 27 | ||

| 26 | The future of community co-management lies in the equal cooperation and joint governance of diverse subjects, but government led governance is more in line with current reality | −0.85 | 23 | −0.50 | 21 | −0.22 | 21 | 1.54 | ** | 3 | |||

| 27 | Low education level and insufficient professional knowledge and skills are the biggest obstacles for community residents to effectively participate in community co-management | 0.00 | * | 15 | −0.56 | * | 22 | 0.95 | 6 | 0.67 | 6 | ||

| 28 | Community residents are satisfied with the compensation they have received due to reasons related to protected areas | −1.18 | 27 | −2.42 | 30 | −2.25 | 30 | −1.67 | 29 | ||||

| 29 | Community co-management should be seen as a governance concept rather than a governance tool | 0.05 | 14 | −0.34 | 18 | −1.13 | * | 27 | 0.62 | 7 | |||

| 30 | Community co-management is also helpful in resolving internal disagreements and conflicts within the community | −0.01 | 16 | −0.47 | 20 | −1.69 | ** | 29 | −0.31 | 19 | |||

Note: The significance (or “distinctiveness”) statements within the factor are indicated by * (p < 0.05) and ** (p < 0.01), and the top and bottom three statements of each viewpoint are bolded for observation.

Appendix D

Table A3.

Ranking Table of “Consensus” and “Disagreement”.

Table A3.

Ranking Table of “Consensus” and “Disagreement”.

| No. | Statement | Perspective | Ranking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | Value | |||

| 12 | Community co-management activities should be subject to comprehensive internal and external supervision☐ (*) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.049 | 1 |

| 23 | Community co-management must establish a more transparent information disclosure mechanism☐ (*) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.075 | 2 |

| 21 | There are abundant practical cases of community co-management in China, but there is insufficient theoretical research | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.108 | 3 |

| 20 | The higher the level and larger the scale of nature reserves, the more difficult it is to achieve effective co-management | −2 | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0.111 | 4 |

| 22 | Community co-management can promote the realization of community democracy | 0 | −3 | −2 | 0 | 0.135 | 5 |

| 14 | Community co-management and rural revitalization can be organically combined | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0.155 | 6 |

| 17 | The key to the construction of entrance communities and characteristic towns is to mobilize the enthusiasm of stakeholders | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.188 | 7 |

| 9 | Local governments have the motivation to actively promote community co-management construction | −1 | −2 | −1 | 1 | 0.192 | 8 |

| 28 | Community residents are satisfied with the compensation they have received due to reasons related to protected areas | −2 | −4 | −4 | −3 | 0.24 | 9 |

| 1 | Communities and their residents should be regarded as an integral part of nature reserves | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.287 | 10 |

| 18 | Community co-management adheres to the problem orientation, adapts measures to local conditions, and is unable to form a unified model that can be widely promoted | 0 | −2 | 0 | 0 | 0.288 | 11 |

| 3 | Community co-management must meet the demands of different stakeholders | −2 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0.304 | 12 |

| 16 | There is no complete system and legal guarantee for community co-management | 0 | 2 | 0 | −1 | 0.342 | 13 |

| 27 | Low education level and insufficient professional knowledge and skills are the biggest obstacles for community residents to effectively participate in community co-management | 0 | −1 | 2 | 2 | 0.347 | 14 |

| 8 | Community residents should participate in co-management decision-making indirectly | 1 | −2 | 0 | 1 | 0.361 | 15 |

| 29 | Community co-management should be seen as a governance concept rather than a governance tool | 0 | 0 | −2 | 2 | 0.402 | 16 |

| 30 | Community co-management is also helpful in resolving internal disagreements and conflicts within the community | 0 | −1 | −3 | −1 | 0.409 | 17 |

| 19 | Only regions with certain resource endowments and development potential can effectively implement community co-management | 2 | −2 | 1 | 1 | 0.453 | 18 |

| 4 | Community co-management is difficult to effectively drive employment and entrepreneurship among community residents | −3 | 0 | 1 | −2 | 0.467 | 19 |

| 5 | In the process of community co-management, the government can delegate some power to entities such as enterprises and social organizations | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.478 | 20 |