Abstract

Climate adaptation in urban environments is often constrained by rigid institutional rules and fragmented governance, which limit inclusive and context-specific planning of public spaces such as schoolyards. This study addresses this challenge by examining how collaborative planning can transform schoolyards, from asphalt-dominated, monofunctional spaces into green, climate-resilient community assets. The research employed the Institutional Analysis and Development framework within a qualitative case study design. Two public schools in the San Cristóbal de los Ángeles neighbourhood of Madrid served as case studies, with data collected through document analysis, participant observation, and interviews with municipal officials, urban planners, educators, and community members. Results indicate that the collaborative planning process reshaped rules in use, expanded the network of actors, and transformed decision-making processes. Existing rules were flexibly reinterpreted to allow new uses of space. Children, teachers, and residents became co-producers of the public space, expanding the governance network, where new deliberative practices emerged that improved coordination across people and organisations. These institutional changes occurred without formal regulatory reform, but with the reinterpretation of the game’s rules by each organisation. Thus, schoolyards can serve as laboratories for institutional innovation and participatory climate adaptation, demonstrating how urban experiments have the potential to catalyse not only physical transformations but also transformations in urban management.

1. Introduction

Climate change poses increasing challenges for cities, which must adapt to more extreme, recurrent, and unevenly distributed weather conditions. This challenge is particularly urgent in school environments, where vulnerable groups such as children are concentrated and where high temperatures and a lack of shade or green infrastructure affect thermal comfort and students’ physical, emotional, and social well-being [1,2]. The transformation of these spaces should not be understood solely as a technical exercise of bioclimatic architecture, but also as an opportunity to rethink the relationships among public institutions, citizens, and territory in search of socially legitimised and sustainable solutions over time [3,4].

In this context, the role of proximity as a spatial logic and the diffusion of activity hubs within neighbourhoods are receiving growing attention in the scientific literature [4,5,6]. Transforming school environments into multifunctional infrastructures within daily urban systems contributes to decentralising public services and reinforces territorial equity. As Moreno’s ‘15-min city’ model highlights, proximity enhances access and promotes socio-spatial cohesion and ecological resilience [4]. This interpretative framework underpins the relevance of schoolyards as relational nodes capable of concentrating environmental, educational, and civic functions, especially in vulnerable urban areas.

City councils worldwide have implemented urban regeneration strategies and plans. Specifically, since 2020, the Madrid City Council has advanced a new urban agenda focused on the ecological regeneration of school environments. The aim is to transform school playgrounds and entrances into ‘climate-social oases’ [7,8,9]. However, the traditional design procedure for this type of intervention has historically been led by municipal technical teams and external consultants, with limited participation of the educational communities, let alone the children, their families, and communities, the users of these public facilities. Although effective from an operational point of view, this techno-institutional approach tends to render invisible situated knowledge, local needs, and community aspirations, reproducing dynamics of fragmentation and inequality in the use and appropriation of public space [10,11].

The European project LIFE PACT (People-Driven: Adapting Cities for Tomorrow) [12] proposes an alternative model for intervening in school environments and schoolyards. Based on urban experimentation, the model consists of active listening, co-creation, participatory prototyping, evolving communication, and evaluation. Implemented in Madrid between 2021 and 2025, the project was carried out in the San Cristóbal de los Ángeles neighbourhood (Villaverde district), one of the areas with the highest levels of social, economic, and climate vulnerability in the city [13]. A local consortium—including schools, municipal technicians, cultural and civil society organisations, and universities—was formed to test a new procedural model that introduces collaborative planning to co-design resilient school infrastructures [14].

Although collaborative planning has proliferated globally, it often remains confined to small-scale ‘niches’ due to significant barriers to expansion, including the challenges of interdisciplinary collaboration [15,16] and the difficulty of transitioning into established regimes without being co-opted [17]. Similarly, establishing effective multi-actor collaborations [18] or integrating institutional innovation into existing organisational structures [19,20] remains an ongoing challenge.

This paper addresses the following research question: How do collaborative planning processes and actor networks in the transformation of schoolyards reshape institutional arrangements? This question responds to an emerging need to analyse the physical outcomes of nature-based interventions and the institutional mechanisms that enable or hinder their implementation, diffusion, and continuity over time.

To address this question, the article draws on the experience of Madrid and analyses it through the lens of the institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework, developed by Elinor Ostrom [21,22,23,24]. The IAD framework enables the observation of how ‘rules in use’, community attributes, and the biophysical characteristics of the environment collectively shape an ‘action situation’—that is, an institutional space where actors interact, make decisions, cooperate, or conflict [22]. By applying this analytical framework to the case study, this research identifies how the configuration of the actor system influences institutional arrangements, the incentives for collective action, the rules governing access and deliberation, and both the intangible and physical outcomes of the intervention.

This approach is part of the growing interest in applying theoretical frameworks from multistakeholder governance analysis to the study of urban innovation [24,25]. In contrast to linear or technocratic views of institutional change, the IAD framework allows us to capture informal transformations that are not always reflected in formal regulations or structures, but impact the legitimacy, sustainability, or adaptive capacity of public actions [22]. Moreover, the case study connects with an emerging stream of experimental urbanism studies where the shared production of knowledge, the validation of ideas in authentic contexts, and openness to uncertainty are seen as drivers of institutional transformation [14,26].

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the conceptual framework, focusing on reframing schoolyards through institutional innovation and collaborative urban planning. Section 3 describes the materials and methods used in the Madrid case study, including documentary analysis, direct observation, and interviews with key stakeholders. It also details the IAD framework developed by Elinor Ostrom, which was applied to assess the institutional dynamics of the case study. Section 4 presents the results, offering a comparative analysis of the traditional planning procedure and the experimental model introduced. Section 5 discusses the findings, reflecting on the implications of these transformations for urban policy, participatory planning, and the design of institutional arrangements. Finally, Section 6 concludes by summarising the main insights and outlining recommendations.

The study reveals that the introduction of collaborative planning broadens the number and diversity of actors engaged in the intervention while also reshaping the rules that structure their interactions. Rather than following a closed process with predetermined decisions, collaborative planning fosters dynamics of deliberation, mutual learning, and co-production of expert and situated knowledge. These dynamics in turn enhance all participants’ sense of ownership, relevance, and legitimacy.

2. Reframing Schoolyards: Collaborative Planning and Institutional Change in Urban Ecosystems

Adapting schoolyards and their surroundings to climate change offers a strategic window for rethinking and innovating urban management practices [4]. Traditionally conceived as functional spaces for children’s recreation and sports practice, these spaces have historically been managed under centralised technical logic, with little institutional flexibility and little participation of the educational community [26,27,28]. However, the climate emergency, the growing concern for children’s health, and the need to build more inclusive cities are revaluating these environments’ role in urban regeneration and social resilience [26,27,29].

Innovation in the urban design of school playgrounds and environments does not lie exclusively in the technical–material dimension but also in the modes of governance and institutional management that allow these transformations to occur in a more democratic, contextualised, and sustainable manner [14,22,30]. The transition from top-down planning—centralised in the municipal administration, but fragmented in decision-making by its different departments—to increasingly collaborative urban planning, decentralised and co-led, implies a transformation in how decisions are made, how rules are negotiated, and who has the initiative in public interventions [31,32,33,34]. Collaborative urban planning requires integrating community voices into the deliberative and regulatory dimensions, thus bridging the gap between grass-roots action and institutional procedures [5,35].

2.1. From Functional Spaces to Climatic and Social Infrastructures

The design of school environments and playgrounds during much of the twentieth century was profoundly shaped by the principles of functionalist urbanism [36,37,38] emerging from the modernist movements of the early 1900s and particularly codified through the Athens Charter [39] promoted by Le Corbusier and the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM). This paradigm advocated for a zoning of urban functions—housing, work, recreation, and circulation—each separated and optimised according to technical rationales [39,40,41]. Schools, extensions of this logic, were designed following highly standardised models, where playgrounds were treated as empty, asphalted areas dedicated to physical exercise, surveillance, and discipline [26,36]. The physical environment reflected and reinforced a pedagogical model centred on order, repetition, and control, limiting opportunities for exploration, diversity of uses, or ecological interaction [6,40]. In this conception, children and the educational community were not considered active agents in shaping their environment. Instead, they were positioned as passive users within predetermined spatial arrangements, echoing the broader modernist aspiration to regulate urban life through technocratic design [36,41]. The legacy of the functionalist paradigm remains evident in many contemporary school environments: extensive impermeable surfaces, a lack of shade or ecological diversity, the prioritisation of movement over rest, and a limited understanding of children’s social, emotional, and environmental needs [26,41].

In response, numerous European cities are making significant efforts to reverse this trend through ambitious urban policies that aim to reimagine school environments as climate-resilient and socially inclusive infrastructures. Examples include Barcelona’s Protegim les Escoles programme [42], Pontevedra’s Ciudad de la Infancia [43], Paris’ initiatives Rues aux Écoles [44] and La Cour Oasis [45], and London’s Climate Resilient Schools project [46]. Despite these efforts, a persistent imbalance remains between regulation, design, and social negotiation in urban interventions [21,22,23,24]. Institutional inertia and pre-established procedural norms limit meaningful citizen engagement in defining, managing, or transforming these public infrastructures. In many cases, the most significant barriers are not technical or economic, but institutional: fragmented competencies across municipal departments, rigid regulatory frameworks, lack of participatory channels, and insufficient intersectoral collaboration all hinder the systemic integration that school environments could enable [26,27].

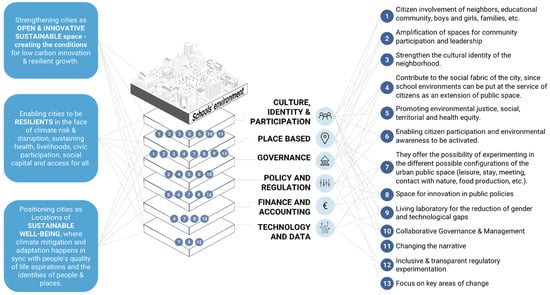

As illustrated in Figure 1, these spaces intersect with multiple urban dimensions, from health and education to mobility, biodiversity, and democratic governance. Addressing these challenges requires a systemic approach to the problem to open the door to the multiple potential of these spaces, recognising school environments and playgrounds as more than isolated challenges, but as leverage points within a complex urban ecosystem [27,47]. The transformations of school playgrounds generate benefits that transcend the microclimatic sphere, such as thermal regulation and reduction in pollutants, and impact physical and mental health, community cohesion, and the development of social skills [48]. Conceiving school environments as climatic and social infrastructures demands activating systemic urban transformations that intertwine health, equity, sustainability, and education [27]. School playgrounds, as laboratory spaces, offer fertile ground for testing these dimensions in an integrated way [49]. These transformations improve the quality of public space and reformulate the urban language, orienting it towards a more liveable, inclusive, and resilient city [8,9].

Figure 1.

Multilayered analysis of school environments as spaces of urban transformation [26].

2.2. Paradigm Shift: Experimenting with the Adaptation of School Playgrounds Through Collaborative Urban Planning and Adaptive Regulatory Frameworks

The urban experimentation is the deliberate introduction of new rules of the game (procedures or forms of organisation) within an urban system to collectively test, observe, and reflect on socio-spatial innovations in an open way [14,50,51]. According to Ostrom [24], “the rules of the game” structure human action. Altering these rules—for example, by enabling children and community members to co-design their school environments—implies a profound reconfiguration of power dynamics, administrative routines, and urban governance practice [25,50]. This approach resonates with the ‘experimental urbanism’ literature, where the co-production of knowledge and situated learning are essential public innovation mechanisms [51]. Notable examples include studies on temporary urbanism, living labs, and tactical interventions, which challenge the linearity of formal planning and promote hybrid processes of institutional transformation [17,19,26,50].

The transformation of schoolyards must be understood within the broader planning system and regulatory frameworks that govern public space. Urban planning is structured around the intricate and sometimes conflicting interplay of regulation, design, and negotiation [52,53]. Intervening in school playgrounds, therefore, requires architectural or participatory innovation and engagement with land-use rules, planning instruments, maintenance responsibilities, and an interdepartmental coordination mechanism [17]. Collaborative urban planning offers a strategic opportunity to realign conventional procedures by creating deliberative arenas where institutional actors, such as municipal departments and schools, engage alongside civil society and local communities to co-define priorities and modes of intervention [18,19]. Rather than a mere participatory add-on, it constitutes a pathway to renegotiate institutional roles, redefine public responsibilities, and reform existing regulatory frameworks [54].

While collaborative planning offers multiple benefits, many authors have highlighted inherent ambiguities. For instance, Savini and Bertolini [55] caution that collaborative planning risks becoming a superficial innovation strategy disconnected from substantive institutional transformation without a deeper engagement with structural inequalities. Similarly, Swyngedouw [35] criticises that these practices are often promoted by governmental or technocratic elites, avoiding conflict and depoliticising urban decisions under the discourse of the ‘possible’ or the ‘prototypable’. Swyngedouw adds that many participatory initiatives tend to depoliticise urban action, masking conflict under technocratic consensus [9]. Purcell stresses that without clear structures of equity and accountability, these processes can be co-opted by dominant actors [56]. Therefore, collaborative planning must transcend symbolic or non-binding engagement, anchoring participation in legally robust and inclusive mechanisms [57]. A critical and situated perspective is essential to ensure that collaborative planning not only innovates in technical terms but also addresses entrenched power structures, reshapes institutional priorities, and reconfigures modes of urban production.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopts the IAD framework, developed by Elinor Ostrom and collaborators [21,22,23,24], to understand how collaborative planning processes and actor networks in schoolyard transformation reshape institutional arrangements. The IAD framework provides a robust conceptual tool to examine the institutional arrangements that shape collective decision-making processes, their internal dynamics, and their capacity for adaptation and transformation.

3.1. Conceptual Framework: Institutional Analysis and Development Framework

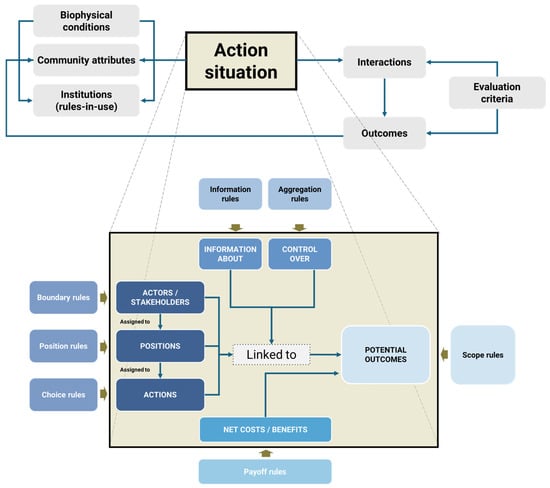

The IAD framework, developed by Elinor Ostrom in the 1990s, provides a conceptual tool for understanding how people make decisions, interact, and manage common resources in complex contexts. Although it initially emerged from analysing natural resource systems, its scope has been progressively extended to public policy, urban planning, and governance of social–ecological systems [22,25]. In its revised version, Ostrom [24] emphasises the analysis of institutional change and the capacity of governance arrangements to adapt to dynamic, multi-scale contexts. This broadening of the framework allows for looking at current governance structures and their trajectory, openness to learning, and potential for transformation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Institutional analysis and development framework and detailed ‘action situation’ analysis structure elements [22].

The core of the IAD framework is the ‘action situation’, conceived as the social space where different actors make decisions, negotiate, cooperate, or enter into conflict. This concept allows us to focus the analysis on the immediate structures that shape collective behaviours and the outcomes of an institutional process [21,22,23,24,25]. The IAD framework proposes we decompose these situations into their key elements to identify patterns, explain dynamics, and guide possible reforms in institutional arrangements.

Three major components condition the action situation: (1) the biophysical environment, which defines the material and ecological conditions that frame collective action; (2) community attributes, which include culture, social capital, shared norms, and history of cooperation; and (3) the rules in use, both formal and informal, that determine who participates, what they can do, with what information, and under what criteria decisions are made. These rules are organised into various analytical categories. Position rules delimit the roles that actors can play; access rules establish the criteria for entry or exit into those roles; and others regulate the actions allowed, the information available, the collective decision-making procedures, the applicable incentives or sanctions, and the outcomes that are considered legitimate. These rules shape the institutional framework within which actors interact [25]. While the IAD is a robust framework for analysing and mapping institutional relationships, it also has limitations. One is its tendency to simplify the multi-scale complexity characterising many decisions in contemporary cities. Urban practices are conditioned by influences that cut across different institutional and territorial levels, which requires complementing the analysis with a situated and relational view of the context [55]. A qualitative analysis based on interviews with project actors was incorporated to mitigate this bias and provide a systemic view at the institutional level and the broader context influencing management decisions and outcomes [58].

This analytical framework could generate contributions such as (i) identifying how the introduction of an urban experiment of collaborative planning transforms the rules in use into rigid institutional processes, allowing the recognition of new actors, knowledge and languages within urban design, and (ii) evidencing the emergence of collaborative governance mechanisms within and outside public administrations that overcome the traditional sectoral fragmentation in management. These contributions, rooted in the case study, allow us to understand institutional innovation not as a disruptive leap, but as a progressive transformation of the formal and informal rules that regulate urban public action.

With regard to the challenges pointed out by Ostrom, this article addresses (i) the need to adapt institutional arrangements to changing contexts, which is reflected in operational and regulatory flexibility; (ii) the importance of polycentric governance, observed in the articulation between diverse actors and different scales (municipal, district, school, neighbourhood); (iii) the potential replicability of the model; and (iv) the internal reflection of public institutions on their capacities to innovate from situated action.

Finally, the IAD framework was particularly suited for this study, as it critically examines how institutional arrangements are informally transformed through practice, without requiring formal regulatory change. In a complex, multi-actor intervention such as the participatory redesign of school playground, the IAD framework makes it possible the analysis of how power, rules, and responsibilities are renegotiated in situ. Its focus on ‘rules in use’ provides analytical traction to capture the institutional innovation that emerges through urban experimentation beyond prescriptive planning models.

3.2. Method

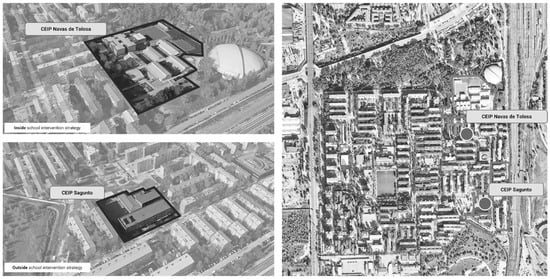

This study adopted a qualitative research approach based on a case study methodology, which is particularly suited for investigating complex social phenomena and exploring the relationships among context, agency, and institutional change [58,59]. As Eisenhardt [60] highlights, case study research is especially valuable in theory building, as it enables the researcher to generate in-depth and context-rich insights from real-world interventions. The case analysed corresponded to the collaborative planning for the renaturalisation of two public school environments (See Figure 3). This case was selected not only due to its relevance as a site of climate–social experimentation but also because of the direct involvement of the research team in the process, which enabled the consolidation of relationships of trust with both institutional and community actors.

Figure 3.

Plan and axonometry of the location of the case study (Navas de Tolosa School, Sagunto School, Villaverde).

Data collection combined primary and secondary sources. Five semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders, including municipal technicians, teachers, members of the consortium, and design facilitators [Appendix A: List of interviewees]. These interviewees were selected through purposive sampling to ensure a diversity of perspectives relevant to the institutional dimension of the experiment, though they did not constitute a statistically representative sample [61,62]. The data were analysed using a deductive–inductive coding strategy informed by the categories of the IAD framework, while remaining open to emergent themes grounded in the fieldwork.

Complementary sources included documentary analysis of strategic, regulatory, and technical materials (such as implementation projects, diagnostic reports, and municipal policy plans), participant observation during design sessions, community events and interdepartmental meetings, as well as the review of audiovisual records, including a video-manifesto, photographs, and graphic documentation of the participatory process [See Supplementary Materials]. This methodological triangulation allowed for the identification of visible changes in the physical configuration of the school environments and less tangible shifts in institutional rules, power dynamics, and organisational learning patterns.

The methodological approach is framed as collaborative management research [63], in which researchers and system actors co-produce actionable knowledge [64,65]. This mode of inquiry made it possible to generate situated and practice-oriented insights, reduce interpretation biases by engaging with diverse stakeholders, and participate directly in key moments of the experimental process. Although the study was based on a single case (two schools in Madrid), the consistency of patterns observed across actors, levels, and outputs suggests the presence of trends that may be transferable to other urban contexts while acknowledging the inherent limitations of a singular case analysis.

3.3. Materials: Case Study

The case study analysed in this research focused on the renaturalisation of two public school environments located in the neighbourhood of San Cristóbal de los Ángeles, in the district of Villaverde, Madrid. With a population of 16,886 inhabitants [66,67], San Cristóbal is considered one of the areas with the highest levels of climate vulnerability in the city [13]. It also registers the lowest average net household income in the municipality, and it presents a high proportion of residents with only basic education (28.21%), which reflects a significant risk of the consolidation of social exclusion conditions [67]. According to the Municipal Register of 2021, 35.83% of the population is of foreign origin, predominantly from Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Eastern Europe [66,67]. Despite these limitations, it has a rich neighbourhood network, with many self-deployed associations and services [66,67].

Within this context, the two public schools selected—Sagunto School and Navas de Tolosa School—served as test beds for exploring innovative approaches to the design of educational spaces that are not only greener and more climate-resilient, but also socially inclusive and better integrated into the neighbourhood’s urban and community dynamics. Their selection was especially pertinent given their strategic role as daily points of encounter for vulnerable children and families, their limited environmental quality, and their potential to catalyse broader processes of ecological regeneration and community empowerment at the neighbourhood scale.

The project to renaturalise school playgrounds was supported by a multi-actor ecosystem composed of several municipal departments, educational institutions, civil society organisations, academic institutions, and design facilitators, whose coordinated involvement was essential throughout the different phases of the process. The Department of Energy and Climate Change of the Madrid City Council provided institutional leadership, aligning the intervention with climate adaptation policies and securing public investment. The participating schools—Sagunto School and Navas de Tolosa School—acted as territorial anchors, mobilising their educational communities and facilitating the integration of pedagogical, social, and spatial perspectives. Local civil society organisations and cultural associations contributed their proximity to the territory and knowledge of community dynamics, helping to mediate participation and support vulnerable groups. The Innovation and Technology for Development Centre team at the Technical University of Madrid (itdUPM) played a dual role as process facilitator and research partner, designing the participatory methodology, coordinating actor engagement, and documenting institutional learning. Finally, external design and engineering teams collaborated throughout the process to translate the co-created visions into technically viable execution projects. This distributed governance structure enabled a dynamic interplay of roles and responsibilities, fostering trust, mutual learning, and shared ownership across organisations.

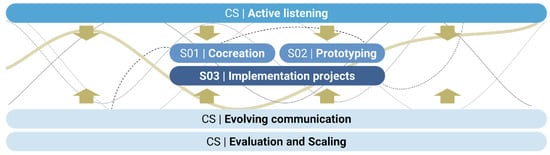

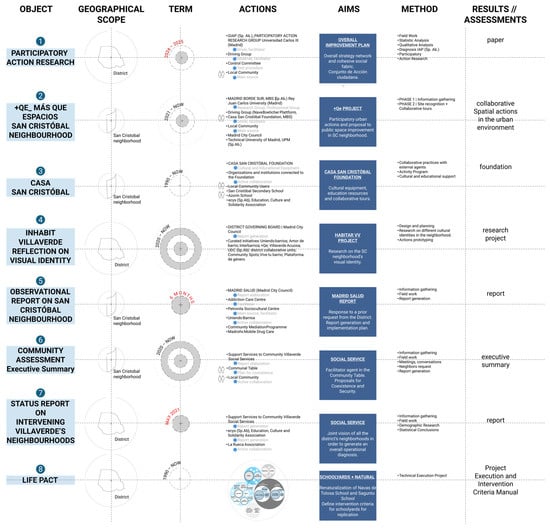

A multiphase methodological architecture was structured around the project to bridge technical development with civic engagement. It combined three cross stages (CSs)—active listening, evolutionary communication, and evaluation and scaling—with three iterative stages (Ss): co-creation, prototyping, and technical drafting of the implementation project (Figure 4). These stages articulated participatory urban experimentation with formal planning instruments, enabling institutional reflection, collective creativity, and situated learning. This architecture allowed for integrating pedagogical, political, and design perspectives into a cohesive process of urban transformation, positioning the schoolyards not merely as objects of design, but as platforms for testing new governance models and climate–social infrastructures [Appendix B: Methodological architecture of the urban experiment].

Figure 4.

Stages of work implemented in the school playground project.

Each stage of the process is detailed below.

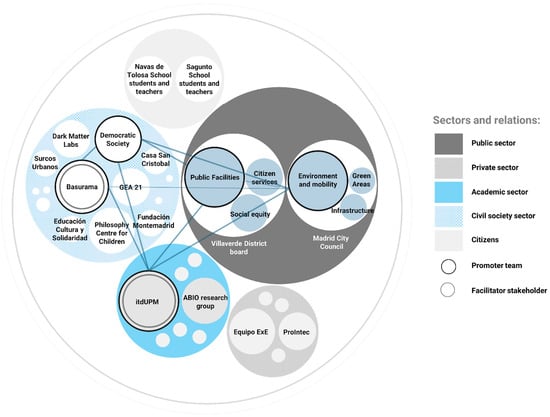

- CS|Active listening: From the very beginning of the project, a strategy of active listening [68] was implemented, including not only stakeholder mapping (Figure 5) but also the identification and analysing of existing projects, studies, and initiatives in the territory (Figure 6). This knowledge allowed a deeper understanding of the stakeholders in the area and their needs, tensions, and opportunities. This stage included participatory diagnostics with schools, interviews with local actors, urban tours with technical teams, and the analysis of municipal strategic documents and previous neighbourhood studies. Through this approach, spatial conflicts that were not visible were identified, such as those related to the lack of shade, inequality in the use of the playground according to gender, or the perception of insecurity in school access and environments. Active listening was key to situating the design in a relational framework, where the school space was not understood in isolation, but as part of a broader urban ecosystem. The mobilisation of the ecosystem of actors by the facilitator team also made it possible to connect the experiment with another seven projects from the public sector, academia, and civil society, establishing synergies and complementarities and generating a greater impact on the territory and better allocation of resources to each of them.

Figure 5. Mapping of the ecosystem of actors involved in the experiment.

Figure 5. Mapping of the ecosystem of actors involved in the experiment. Figure 6. Mapping of existing projects, studies, and initiatives in the territory.

Figure 6. Mapping of existing projects, studies, and initiatives in the territory. - CS|Evolving communication: The second cross-cutting stage consisted of designing a communication strategy as a pedagogical, political, and cultural tool that did not limit itself to informing, but accompanied the process, critically documented it, and allowed for shared learning [69]. Audiovisual materials were produced (such as the video manifesto La Asamblea de la Infancia and the documentary In Praise of the Schoolyard), collective publications, graphic records of the workshops, and educational resources adapted to different ages and audiences [Appendix C: List of dissemination activities (videos)]. In addition, public events, school presentations, and technical forums were held, where progress was shared, impressions were gathered, and approaches were fine-tuned. This evolving communication legitimised the process, broadened its scope, and strengthened community ownership.

- CS|Evaluation and scaling up: The third cross-cutting stage consisted of the evolutive evaluation of the learning generated, with the aim of systematising methodologies, identifying institutional barriers, and exploring possibilities for replicability. Unlike traditional evaluations, which are usually carried out only at the final stages, this approach proposed a dynamic and adaptive evaluation throughout the project’s life cycle [70]. The evaluation was participatory and multi-scale: it included sessions with students, interviews with municipal technicians, meetings with school management teams, and reflective analysis by the research team. Moreover, the evaluation process extended beyond the project’s formal conclusion by establishing a collective monitoring mechanism. The post-execution monitoring aimed to assess the resilience and social appropriation of the interventions over time, incorporating feedback from school communities, neighbourhood organisations, and municipal services. Regular dialogues were initiated with other educational centres interested in replicating the approach, facilitating peer learning and promoting the diffusion of the methodological framework to new contexts. Based on the findings generated throughout this stage, synthesis reports, policy recommendations, and proposals for integrating the approach into municipal strategies were produced. These included intervention guidelines for school environments and playgrounds with climate change adaptation criteria and new technical specifications for playground maintenance.

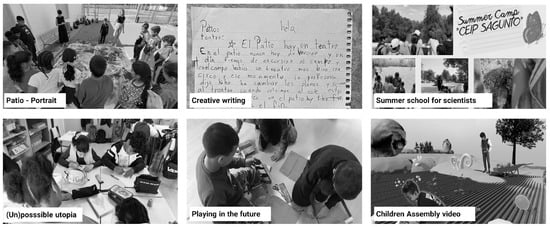

- S01|Co-creation: Co-creation stood at the heart of the process, serving as both a methodological and political device that fostered the participation of diverse actors to jointly generate value through equality, transparency, dialogue, and trust among participants [71,72]. According to Trischler [73], co-creation transforms the traditional supplier–customer relationship, turning the citizen into an end user and a designer. Through more than 24 sessions with students from both schools, creative writing, ecological imagination, and participatory design strategies were deployed. Dynamics included games, emotional mapping, commented tours, and dramatisation of desired futures. Exercises such as the ‘Patio Portrait’ or ‘Utopia is Possible’ allowed for construction of a collective narrative of the school space and its shortcomings and potential (Figure 7). Co-creation was also extended to teachers, families, social organisations in the neighbourhood, and municipal technicians, creating a multistakeholder and multidisciplinary meeting space.

Figure 7. Co-creation and prototyping sessions of the experiment.

Figure 7. Co-creation and prototyping sessions of the experiment. - S02|Prototyping: Based on the results of the co-creation stage, a prototyping stage was carried out, in which spatial, material, and functional proposals were specified. Ideas were represented through ephemeral installations and uses were tested in the schoolyard and the immediate environment. This people-centred approach ensures that the prototypes provide contextually relevant and culturally appropriate solutions [74]. This phase allowed for the validation of solutions with criteria of climatic comfort, diversity of uses, accessibility, and identity. In addition, prototyping facilitated the conversation between technical and non-technical languages by translating children’s imaginings into formats understandable to architectural teams and public procurement officers (Figure 7).

- S03|Drafting of technical projects: The last stage consisted of the drafting of the technical execution project based on the synthesis of the learning generated. The final design incorporated proposals such as the replacement of impermeable floors with draining paving, the planting of adapted trees, the creation of shaded areas, the installation of fountains and inclusive furniture, and the improvement of accessibility. The school entrances were also redefined and the playgrounds were connected to the adjacent school squares, creating a climate infrastructure on a neighbourhood scale. The municipal teams validated these technical projects and integrated them into the City Council’s investment plans, leveraging close to EUR 5 million of public investment for their implementation. [Appendix D: List of design recommendations grouped by typology and school; Appendix E: Images of before and after the intervention]

Finally, based on interviews conducted with local stakeholders during the evaluation process and the systematisation report, the project generated significant impact in both environmental and social respects. The intervention covered more than 30,000 m2, improving thermal comfort for students and reducing surface temperatures in schoolyards. Over 130 trees were planted, increasing local biodiversity and creating new shaded areas. The participatory process engaged more than 600 individuals on the social front, including students, teachers, families, municipal staff, and neighbourhood organisations. Finally, the lessons learned and the criteria developed for interventions in school environments were systematised and compiled in the Patios Escolares + Naturales guide published by Madrid City Council, providing technical guidelines to support the potential replication of the model in other urban contexts of the city.

4. Results

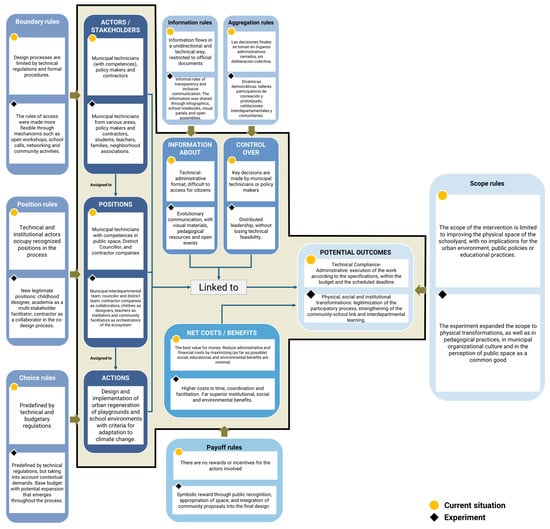

The results of applying the IAD framework to the case study are presented below. Figure 8 summarises the analysis of the action situation [23]. For this research, the traditional process is referred to as the ‘current situation’ and the collaborative planning as ‘the experiment’. The current situation refers to the traditional process of designing school environments, characterised by a hierarchical, expert-led approach with limited participation from the educational community and a focus on technical compliance. The experiment denotes collaboratively redesigning and renaturalising two schoolyards through active listening, co-creation, participatory prototyping, and collective monitoring, integrating children’s, teachers’, and community members’ knowledge and perspectives into public decision-making. The comparative analysis reconfigures the conditions that structure collective action and public decisions in the urban realm.

Figure 8.

Analysis of the action situation using the IAD framework.

Firstly, there is a substantial broadening of the range of participants in the experiment (actors/stakeholders in Figure 8). While in traditional procedures, the relevant actors are mainly municipal technicians, policymakers, and contractors, the experiment actively involved students, teachers, neighbourhood associations, art collectives, and urban facilitators. More than 600 people and 33 organisations from different sectors participated. The mobilisation of the ecosystem of actors also enabled the experiment to establish connections with seven other projects from the public sector, academia, and civil society, fostering synergies and complementarities that amplified the territorial impact and optimised the allocation of resources across initiatives. This articulation was not merely nominal, but involved a substantive redistribution of agency and decision-making power over the space, reconfiguring the institutional ecology involved in planning and managing the school environment.

The configuration of roles also underwent significant changes. The traditional process is characterised by a hierarchical and rigid distribution of roles between the public sector (municipal technicians) and the private sector (architects, designers, contractors), excluding the space’s direct users. In contrast, the experiment allowed the emergence of new positions: children were recognised as valid design agents; teachers adopted a mediation role between the pedagogical and the spatial dimensions; and the experiment’s facilitators played key roles in translating technical and community languages. The institutional action situation was redefined by acknowledging students as users and co-authors of the intervention. This redistribution of the field of positions opened up new possibilities for deliberation and co-responsibility. Students’ contributions shaped both spatial proposals and normative criteria, evidencing their ability to influence decision-making arenas. From identifying conflicts such as gender-based use inequalities to suggesting alternative uses and aesthetic preferences, their inputs introduced affective, symbolic, and experiential dimensions that broadened the planning rationale beyond technical–functional considerations.

The rules of choice also changed in the experiment. In traditional processes, technical regulations strictly delimit possible actions without room for contextual adaptation. The experiment introduced dynamics of iterative deliberation, where decisions were progressively adjusted according to collective learning, evidence, and the imaginings projected by the children and the community. Children’s imaginings functioned as a basis for evaluating design options, modifying the game’s rules. Although no formal changes in regulations were established, the municipal technicians could technically and legally justify the proposals in the different co-design spaces by relying on interpretations of existing norms. An example is the inclusion of water games in the school playground, the first to be installed in a public school playground in Madrid.

Another central issue was the level of information available during the process. Standard procedures restrict access to information, concentrating it in technical hands and reducing circulation to administrative documents of difficult non-technical interpretation. In the experiment, evolving communication strategies were developed that included visual materials, pedagogical tools, public events, and resources adapted to different ages and audiences. This pluralistic information circulation facilitated understanding and ownership of the process, informed participation, and greater institutional transparency.

Decision-making control was also altered. While this control rests almost exclusively with technical and political bodies in traditional processes, shared decision-making mechanisms were enabled in the experiment. Co-creation workshops, community validations, and participatory prototypes allowed for redistributing decision-making power, transforming urban design into an open, deliberative space. This openness did not eliminate existing institutional frameworks, but made them more flexible to incorporate other rationalities and sensibilities.

Regarding positional rules, the experiment shows how redefining the informal normative frameworks that determine who has the right to intervene in urban design is possible. The institutional recognition of children and the community as legitimate actors breaks a long tradition of technocratic planning. Likewise, the contractor moves from a unilateral transactional relationship (subcontracting) to an active agent in the collaborative design process, translating the ideas and imaginings of the participants into viable technical solutions. The facilitating team reconfigured the boundary rules by orchestrating the progressive entry and exit of stakeholders into the experiment, thus expanding the boundaries of the planning process. Aggregation rules, which in traditional procedures usually delegate decision-making to closed instances, were replaced by more horizontal aggregation mechanisms in the experiment. Consensus building took place through collective validations, interdepartmental agreements, and collaborative design sessions, where the final decision resulted from integrating multiple perspectives. In addition, reporting rules were transformed by adopting more accessible, inclusive, and visual formats, which democratised access to technical knowledge and reduced asymmetries between actors. Reward rules, traditionally non-existent in conventional procedures, were also modified. The participation of the network of actors in the experiment generated symbolic (recognition, appropriation of space) and organisational (institutional legitimacy, internal learning, public visibility) incentives, helping to sustain collective commitment throughout the process. These incentives were validated in the project’s dissemination sessions, and video documentaries on the urban transformation were developed [Appendix D: List of dissemination activities and products].

The traditional model is limited to the physical execution of the work in terms of the intervention’s scope. Thanks to the collaborative planning and the direct involvement of municipal technicians and political agents, the experiment expanded the scope of the intervention from 8000 to almost 30,000 square meters, leveraging EUR 5 million of public resources for its implementation. In this sense, the experiment broadened the scope towards physical transformations and pedagogical practices in the municipal organisational culture and the perception of public space as a common good.

Although the IAD framework does not formally include the evaluation of results as one of its core analytical components, this study incorporates it as a complementary lens to capture emergent outcomes related to learning, legitimacy, and social impact. Important differences emerged between the traditional process and the experiment in this regard. In the conventional model, evaluation is primarily based on quantitative technical indicators, focusing on compliance with the project specifications, adherence to deadlines, and budgetary efficiency. In contrast, the experiment incorporated a participatory, qualitative, and multi-criteria evaluation approach. Beyond the physical execution, it assessed dimensions such as climatic comfort, children’s ownership of the space, symbolic impact, quality of the collaborative process, and the potential for replicability. This shift broadened the scope of what was considered an outcome. While the traditional approach narrowly measured success in technical terms, the experiment recognised social, pedagogical, and institutional outcomes as equally relevant.

In terms of costs and benefits, although the experiment required greater investments of time, coordination, and institutional flexibility, it generated significant qualitative returns: it strengthened the social fabric, enhanced the legitimacy of participants within institutional frameworks, promoted organisational learning, and improved both the climatic and educational environment of the schoolyards. Particularly in high-vulnerability contexts such as San Cristóbal, this approach’s medium- and long-term benefits outweighed the initial investment, demonstrating the value of integrating broader criteria into evaluating public interventions.

5. Discussion

Applying the IAD framework to this case study allowed reflection on how collaborative urban planning processes can be transformed through situated experimentation. This section discusses the study’s findings considering four significant challenges: (i) the need to adapt institutional arrangements to changing contexts, (ii) the importance of developing collaborative governance schemes, (iii) the intrinsic tensions and contradictions in the rules in use, and (iv) the generation of institutional capacities to innovate operational practices.

5.1. Institutional Arrangements in Complex Contexts

One of the key findings of the case study is its demonstrated capacity to operationalise the adaptation of institutional arrangements to the specific conditions of complex neighbourhoods characterised by intersecting social, urban, and climatic vulnerabilities. In these contexts, the rigidity of current administrative and regulatory frameworks in responding to the territory’s needs is evident. Urban planning operates with standardised solutions, hierarchical procedures, and closed specifications that limit the possibility of integrating situated knowledge, community proposals, or adaptations during the project. In contrast to the traditional model, the experiment introduced a working logic based on multistakeholder collaboration, enabling greater flexibility in operational frameworks without departing from existing institutional structures. An iterative process was designed to combine cyclical stages (co-creation, prototyping, technical drafting) with transversal stages (active listening, evolutionary communication, evaluation, and scaling). This methodological architecture progressively incorporated new rules, actors, and deliberation mechanisms within the institutional framework, fostering more adaptive and context-sensitive forms of public intervention.

The observed flexibility did not come from formal normative reforms, but from a practical reinterpretation of the game’s rules, which enabled new forms of action without modifying the current legal framework. This reinterpretation was made possible thanks to interdepartmental collaboration, political will, and the mediation of the facilitating team, which translated the technical language into understandable and adaptable formats. In this sense, the experiment responds to Ostrom’s [22] call to build governance frameworks capable of adapting to changing local conditions through organisational learning. A crucial factor in this flexibility was the inclusion of students’ perspectives, which grounded design and planning procedures in everyday school life and tangible user experiences. This factor is particularly relevant for designing public policies that address complex problems such as climate change adaptation and social inclusion. This operational flexibility is one of the keys to designing public policies that are technically feasible, socially relevant, and territorially adjustable.

5.2. Collaborative Governance: Articulation Across Scales and Actors

In contrast to the dominant top-down approach in urban planning, the experiment promoted a distributed and multi-actor leadership, articulated across different scales (school, neighbourhood, district, and city) and sectors (technical, educational, community, and academic). This polycentric approach did not imply the elimination of formal frameworks of competence, but rather their reorganisation to allow for more horizontal collaboration among stakeholders. The process mobilised a network of more than 600 individuals and 33 organisations who participated throughout the different stages of the project.

This broad and sustained collaboration was not spontaneous: it was enabled by the explicit agreement on a set of action rules, as analysed in Figure 7 through the IAD framework. The definition of payoff rules, control rules, boundary rules, and aggregation rules created a clear operational framework for communication, coordination, and decision-making, which proved fundamental to sustaining the experiment over time and across organisational boundaries. In particular, the aggregation rules played a crucial role by establishing deliberative mechanisms, such as collective validations, participatory prototyping sessions, and interdepartmental agreements, that replaced closed decision-making processes with open and negotiated ones. This approach increased transparency and ensured that diverse perspectives were effectively integrated into the outcomes. Children’s participation in these deliberative arenas was not only symbolic: their viewpoints reshaped spatial priorities and challenged adult-centric planning logics.

By not depending on a single actor or administrative unit, the experiment demonstrated a capacity for resilience, sustaining itself despite changes in political agendas, staff turnover, or shifting contextual conditions. This resilience is consistent with McGinnis [25] and Ostrom [24], who argue that distributed systems enhance organisations’ ability to adapt, learn, and respond to complex and dynamic environments. Similarly, the fact that the experiment was embedded within a European project with a four-year horizon provided a crucial structural advantage: it created spaces for reflection, iterative learning, and distributed decision-making beyond the typical financial cycles of public institutions—something that would have been very difficult to achieve under standard administrative conditions.

5.3. Replicability of the Model and Public Capacities to Innovate from Situated Action

Unlike many pilot projects encapsulated in their singularity, the case study was conceived as an open, documented, and transferable model designed for scalability. This was made possible through the continuous systematisation of the process, the development of pedagogical tools, the elaboration of methodological and training guides, and the active involvement of municipal technicians with competencies in urban planning and regeneration. Furthermore, all materials produced during the experiment—including methodological frameworks, educational resources, and communication outputs—were disseminated under Creative Commons licences, reinforcing the project’s commitment to openness and knowledge sharing and facilitating its adaptation to other urban contexts.

The replicability of the model resides not only in the physical redesign of schoolyards but also in the institutional architecture that enabled their transformation. The stages of listening, co-creation, prototyping, and evaluation—together with the set of action rules agreed upon by managers and users—constitute a processual framework that can be adapted to diverse urban contexts, provided that its underlying principles of situated participation, iterative experimentation, and intersectoral collaboration are maintained. This orientation coincides with the proposals of Sabel and Zeitlin [75], who underline that practical institutional innovation does not come from fixed recipes, but from adaptive frameworks that learn from action. In this regard, students’ feedback loops were essential for refining implementation strategies and aligning interventions with actual needs.

In addition to its replicability potential, the project generated significant organisational learning within the public administration. It enabled the implementation of new forms of interdepartmental collaboration, the revision of public procurement procedures, the incorporation of climate and social criteria into technical specifications, and the redefinition of the role of municipal teams as mediators rather than mere executors. These lessons have already been reflected in broader initiatives, such as the municipal programme for the ecological regeneration of school environments. Furthermore, the strategies, methodologies, and measures developed through the experiment are progressively being scaled across the city. Madrid has established the renaturalisation of schoolyards and their surroundings with climate adaptation criteria as a strategic priority. This commitment has been formally embedded in Madrid’s Climate City Contract under the European Union’s Mission framework for 100 climate-neutral and smart cities by 2030 [9]. This institutional anchoring illustrates how collaborative planning, when systematically documented, evaluated, and shared, can transcend its initial scope and shape long-term urban policy at a metropolitan scale.

The institutional transformation was not planned ex ante, but emerged due to the process. This learning by doing constitutes one of the most important contributions of the experiment. As Karvonen et al. [76] have pointed out, cities need technological innovation or advanced design and institutional frameworks that allow testing, correcting, scaling, and learning. Although the case study results are encouraging, their consolidation as a model of urban intervention requires overcoming several challenges. Among them is the need to institutionalise the learning generated and adapting the regulatory and budgetary frameworks so that experimentation does not depend solely on calls for international funds, exceptional financing, or individual wills. Developing institutional capacities—particularly within local governments—is crucial to managing these processes’ complexity, conflict, and uncertainty [14,26,27]. Advancing towards a model of innovative and adaptive urban management requires articulating three key dimensions: (i) the technical, ensuring the environmental quality of interventions; (ii) the political, enabling open and equitable decision-making spaces; and (iii) the deliberative, fostering critical engagement with the territory and institutional actions.

However, its replicability does not rely solely on the methodological instruments developed, but rather on the presence of key enabling conditions: (i) a strong and active community fabric capable of sustaining trust-based relationships; (ii) institutional legitimacy to engage with the ecosystem of actors, along with the administrative competencies required to implement neighbourhood-scale transformations; and (iii) dedicated financial resources to support the facilitation of the entire collaborative planning process.

5.4. Tensions and Contradictions in the Rules in Use

While the experiment enabled more inclusive and flexible planning processes, it also revealed key tensions between co-produced dynamics and existing formal rules. A prominent example concerns public procurement. Although co-creation workshops generated innovative design proposals rooted in children’s and community members’ inputs, these ideas had to be reconciled with legal and technical standards of public tendering. The challenge lay in translating collectively imagined solutions into specifications that could pass legal scrutiny while preserving their original intent.

Similarly, maintenance responsibilities became a friction point. The informal agreements and spontaneous uses generated through participatory prototyping often exceeded what existing service contracts or maintenance protocols could accommodate. This friction created a mismatch between the intervention’s adaptive nature and the rigidity of municipal maintenance routines. In some cases, municipal departments hesitated to assume responsibility for non-standard elements, such as artistic installations or ephemeral interventions. These tensions did not result in outright conflicts, but required continuous negotiation. Facilitating teams played a key role in mediating between institutional imperatives and the experimental ethos, often serving as translators between formal frameworks and informal practices. From the IAD framework perspective, these dynamics reflect frictions between ‘rules in form’ and ‘rules in use’—with the latter evolving through situated action and collective learning.

Recognising these tensions is crucial for institutionalising similar interventions. Rather than viewing them as barriers, they should be understood as productive contradictions that reveal the limits of current governance structures and the need for reform. In this sense, the experiment acted as a testing ground not only for spatial designs but also for institutional resilience itself.

From the IAD framework, the introduction of collaborative processes transforms action situations by redefining roles, rules, and decision-making criteria while broadening the range of actors involved and the types of knowledge mobilised. Its institutional value lies in challenging established routines and fostering new forms of governance that are more flexible, inclusive, and conducive to organisational learning. This approach acts as a field of collective learning, where both the community and administrations develop capacities to manage uncertainty and respond to complex contexts. Children’s involvement exemplifies how non-traditional actors can contribute meaningfully to governance innovation, primarily when mechanisms exist to translate their input into planning criteria. However, as Karvonen et al. [76] warn, its transformative potential depends on its success in influencing institutional structures and not being limited to pilot dynamics without continuity. In this sense, collaborative planning should be understood as a mechanism of progressive institutional innovation [75] whose impact lies in its integration into public logic and its capacity to reformulate the state’s role as facilitator, mediator, and learner.

While the experiment illustrates the potential of collaborative planning to generate institutional innovation, it is important to acknowledge the risks and tensions highlighted by the literature critically. Scholars such as Savini [55] and Swyngedouw [11,35] have warned that collaborative approaches may be co-opted by dominant actors, depoliticise planning decisions, or reproduce existing power asymmetries under the guise of consensus. In this case, efforts were made to counter these risks through active facilitation, open-ended deliberation formats, and the deliberate inclusion of non-traditional actors in the co-design process. Nevertheless, the possibility of asymmetries in influence or institutional inertia should not be underestimated. Ensuring collaborative planning processes remain genuinely democratic requires continuous reflexivity, transparency in governance mechanisms, and the capacity to confront conflict rather than neutralise it. Recognising these challenges is essential for evaluating the outcomes of this experiment and guiding the design of future participatory interventions.

6. Conclusions

This case study, analysed through the lens of the IAD framework, demonstrates that incorporating collaborative planning into the design of schoolyards can trigger profound transformations in the rules in use, the distribution of roles, and the structure of decision-making within public institutions. These transformations respond directly to the research question, showing that collaborative planning processes and multistakeholder networks reshape institutional arrangements by introducing more flexible, inclusive, and context-sensitive modes of governance. The study demonstrates how these transformations reconfigure the institutional ‘action situation’, shifting the centre of gravity of planning from a hierarchical and technical logic towards more adaptive and situated forms of urban governance. This reconfiguration manifested in the redistribution of decision-making power between technical, educational and community actors; in the relaxation of previously rigid rules defining who could participate and with what kind of knowledge; and in the emergence of deliberative dynamics in which decisions were the product of dialogue rather than imposition. In this new framework for action, traditional urban planning ceased to be a closed technical exercise. It became a shared process of institutional construction in which the objectives, means, and criteria for success were co-defined by a multiplicity of actors with diverse interests, incentives, and knowledge.

By integrating its different stages, the case study articulated a multistakeholder and multilevel ecosystem that improved the physical results of the intervention and contributed to organisational learning, normative innovation from practice, and the institutionalisation of more democratic methodologies. The new emerging rules broadened the base of actors involved, diversified the knowledge considered valid, and redefined the criteria by which the results of a public intervention are evaluated. These institutional changes reveal the transformative potential of collaborative practices for advancing inclusive climate adaptation strategies. This institutional innovation, anchored in situated action and the recognition of the specific conditions of territories, offers relevant clues for designing urban public policies capable of responding to complex challenges, such as adapting to climate change, reducing territorial inequalities, and strengthening social cohesion. Rather than replicating closed models, the case study highlights the capacity of local governments to experiment, adapt, and learn by doing.

From a theoretical perspective, this study substantially contributes to the IAD framework and collaborative urban planning theory. First, it extends the application of the IAD framework to the field of participatory urban design by showing that institutional ‘action situations’ can be restructured through practice-based collaborative processes. These findings provide nuance to classical institutional theory, demonstrating that institutional innovation can occur progressively without formal regulatory change. Second, the study enriches collaborative planning theory by offering an analytical lens to understand its effects: empirical findings show that active involvement of schools and local actors in planning enhances spatial outcomes and reshapes power structures and rules within public institutions. It challenges the traditional consultative view of participation and repositions collaborative planning as a driver of institutional transformation aligned with polycentric governance principles.

The research also presents certain limitations. First, it focused on a limited number of case studies (two schoolyards), which restricts the generalizability of the findings. However, the consistency of institutional transformations observed in both sites provides valid and solid grounds to extract conclusions applicable to other contexts facing similar challenges. Although transferable elements have been identified, their application in other environments will require adaptation and contextual analysis. The model’s scalability will depend on each territory’s ability to ensure three key enabling conditions: an active community fabric, institutional capacity to coordinate and execute interventions, and targeted funding to support deliberative and collaborative planning processes. In this regard, further studies should explore mechanisms for institutional scalability of such experimental processes, identifying which factors enable their stable incorporation into public policy, how rules in use evolve over time, and what institutional capacities are needed to sustain inclusive governance models. To this end, we propose a set of concrete and actionable policy recommendations across governance levels: locally, municipalities should embed collaborative planning practices into schoolyard transformation programmes, ensuring the early involvement of schools and communities and allocating specific resources for co-production; nationally, education and urban policies should support these approaches with dedicated funding, regulatory flexibility, and technical guidance; and at the supranational level, entities like the European Union should promote these practices within urban resilience agendas, encouraging replication through targeted funding and knowledge exchange platforms.

This study also offers an operational insight: cities are not merely objects of planning. Nevertheless, they can act as agents of institutional change, capable of redefining their own rules based on lived experience and collective imagination. In a scenario of climate, social, and urban uncertainty, this approach is essential to building governance frameworks that are more resilient, inclusive, and transformative.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1DdPrAuH40Apw9hQRzAeKDw_aivvzVTPq?usp=drive_link (Reviewed 26 April 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.A. and S.R.-M.; methodology, M.A. and S.R.-M.; validation, M.A.; formal analysis, M.A.; investigation, M.A.; resources, M.A.; data curation, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and S.R.-M.; visualisation, M.A.; supervision, S.R.-M.; project administration, M.A.; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the European project ‘People-Driven: Adapting Cities for Tomorrow’—LIFE PACT (LIFE20CCA/BE/001710), which is funded by the European Union’s LIFE Programme.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the daily work of the Madrid City Council staff: Juan Azcárate, Marisol Mena, Luis Tejero, and Irene García, from the Subdirección General de Cambio Climático y Energía, Área de Gobierno de Medio Ambiente y Movilidad. Thanks to the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid team working on the experiment: Nieves Mestre and Irene Ezquerra. Thanks to the team working on the European project: Juan López-Aranguren (Democratic Society), Baptist Vlaeminck (Leuven City Council), and Alicia Carvajal (Dark Matter Labs).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders were not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, the manuscript writing, or the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. List of Interviewees

Appendix B. Methodological Architecture of the Urban Experiment

Appendix C. List of Dissemination Activities (Videos)

| Tittle | Description | Link |

| This Playground is a World event | A reflection event and launch of climate micro-missions in schoolyards, based on the ClimaX Guide methodology | https://youtu.be/inGnOtlTIP8 (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

| Documentary In Praise of the Schoolyard | Interviews with neighbours, students, and school administrators following the intervention in the playground at the Navas de Tolosa Primary School | https://youtu.be/_j5ExJE_Nig?si=TO0dfY0CiL4f0-EQ (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

| LIFE PACT Stories—Madrid (Video 1) | Collaboration with public, academic, and community stakeholders in the co-creation of school spaces | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8KQKQemEUWk (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

| LIFE PACT Stories—Madrid (Video 2) | Generating collective narratives on climate adaptation through participatory design | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHrsP4MdJQg (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

| LIFE PACT Stories—Madrid (Video 3) | Sensory portrait of the San Cristóbal neighbourhood, connecting biodiversity and urban ecosystems | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rW6JJQznMzw (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

| Children’s Assembly | Participatory space for children to propose school transformations through art and philosophy | https://youtu.be/17KxmiyV1aY (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

| Compromisos por el Clima 2022 | School Environments Micro-Mission: Importance of intervening in school environments to improve air quality and climate adaptation | https://www.youtube.com/live/WqpKKRu8Dfw?t=12692s (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

| Compromisos por el Clima 2023 | School Environments Micro-Mission (Pilots): Presentation of progress and lessons learned from the nine school environment transformation pilots in Madrid | https://www.youtube.com/live/CJ1fMgrVlCs?si=KOxkDiPjq3JkhUSJ&t=2627 (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

| Compromisos por el Clima 2023 | A Living Room for Sancris Impact of Co-Design at Navas de Tolosa Primary School as a Driver of Social and Urban Revitalisation in San Cristóbal | https://www.youtube.com/live/CJ1fMgrVlCs?t=11289s (accessed on 26 May 2025) |

Appendix D. List of Design Recommendations Grouped by Typology and School

References

- Almestar, M.; Mestre, N.; Romero, S. The Wild City: Collaborative Practices in Urban Renaturing, 1st ed.; UPM Press: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Baró, F.; Camacho, D.A.; Del Pulgar, C.P.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Anguelovski, I. School greening: Right or privilege? Examining urban nature within and around primary schools through an equity lens. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 208, 104019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.A.; Amel, E.L.; Manning, C.M. Psychology for Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C. La Revolución de la Proximidad: De la «Ciudad-Mundo» a la «Ciudad de los Quince Minutos»; Comercial Grupo Anaya: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961; Volume 21, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Plan de Calidad del Aire y Cambio Climático. Plan A—Portal de transparencia del Ayuntamiento de Madrid (15 January 2025). Madrid City Council. Recuperado 26 de Abril de 2025. Available online: https://transparencia.madrid.es/portales/transparencia/es/Transparencia-por-sectores/Medio-ambiente/Aire/Plan-de-calidad-del-aire-y-cambio-climatico-Plan-A-2017-2020/?vgnextoid=fab664457127f510VgnVCM1000001d4a900aRCRD&vgnextchannel=33d9508929a56510VgnVCM1000008a4a900aRCRD (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Madrid City Council. Roadmap to Climate Neutrality by 2050 of the City of Madrid. 2022. Available online: https://www.madrid.es/UnidadesDescentralizadas/Sostenibilidad/EspeInf/EnergiayCC/06Divulgaci%C3%B3n/6cDocumentacion/6cNHRNeutral/Ficheros/RoadmapENG2022.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Madrid City Council. Madrid Climate City Contract. 2024. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/resource-4063 (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Miraftab, F. Insurgent planning: Situating radical planning in the Global South. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E. Governance innovation and the citizen: The Janus face of governance-beyond-the-state. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1991–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. LIFE 3.0—Life Pact People-Driven: Adaptive Cities for Tomorrow. (LIFE20 CCA/BE/001710). 2024. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/project/LIFE20-CCA-BE-001710/people-driven-adapting-cities-for-tomorrow (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Tapia, C.; Abajo, B.; Feliu, E.; Fernández, J.G.; Padró, A.; Castaño, J. Análisis de Vulnerabilidad Ante el Cambio Climático en el Municipio de Madrid; Ayuntamiento de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Karvonen, A.; Raven, R. (Eds.) The Experimental City; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursztyn, M.; Drummond, J. Sustainability science and the university: Pitfalls and bridges to interdisciplinarity. Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammer, G.; O’Rourke, M.; O’Connell, D.; Neuhauser, L.; Midgley, G.; Klein, J.T.; Richardson, G.P. Expertise in research integration and implementation for tackling complex problems: When is it needed, where can it be found and how can it be strengthened? Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Social innovation, democracy and makerspaces. Rev. Española Terc. Sector 2017, 36, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Partnership and Transformation: The Promise of Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration in Context; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Sanz, V.; Romero Muñoz, S.; Sánchez Chaparro, T.; Bello Gómez, L.; Herdt, T. Making green work: Implementation strategies in a new generation of urban forests. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Muñoz, S.; Alméstar, M.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T.; Muñoz Sanz, V. The Impact of Institutional Innovation on a Public Tender: The Case of Madrid Metropolitan Forest. Land 2023, 12, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Do institutions for collective action evolve? J. Bioeconomics 2014, 16, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alméstar, M.; Mestres, N.; Ezquerra, I. Cocreación a Través de la Experimentación Urbana: Los Entornos Escolares Como Oasis Climático-Social en Villaverde. [Comunicación Técnica]. Congreso Nacional de Medio Ambiente 2024, Madrid, España. 2024. Available online: https://www.fundacionconama.org/wp-content/uploads/conama/comunicaciones/7877/20240923_CONAMA_JMAU_word.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Alméstar, M.; Sastre-Merino, S.; Velón, P.; Martínez-Núñez, M.; Marchamalo, M.; Calderón-Guerrero, C. Schools as levers of change in urban transformation: Practical strategies to promote the sustainability of climate action educational programs. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Şensoy, S.; Sarı, R.M. Re-Design of Schoolyard for Effective Development of Child From a Universal Design Perspective//Etkili Çocuk Gelişimi İçin Evrensel Tasarım Perspektifinden Okul Bahçesi Tasarımı. Megaron 2019, 14, 443. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre-Merino, S.; Zanarotti-Prestes-Rosa, C.; Izaguirres-Betancourth, M.-J. Analysis of initiatives to promote education for sustainability and climate action in schools in Madrid and proposals for improvement [Análisis de iniciativas para fomentar la educación escolar para la sostenibilidad y la acción climática en Madrid y propuestas de mejora]. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2025, 83, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Dumitru, A.; Anguelovski, I.; Avelino, F.; Bach, M.; Best, B.; Binder, C.; Barnes, J.; Carrus, G.; Egermann, M.; et al. Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 22, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Making governance networks effective and democratic through metagovernance. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]