Abstract

Herein is presented a systematic review on property documentation in Greece from 1830 to the present, examining the systems used and their impact on spatial data management and land administration policies. This review reveals that the adoption of the person-based land registry system in 1836, versus the parcel-based Cadastre, led to fragmented property documentation and hindered coherent land administration policies. The establishment of the Hellenic Cadastre in 1995 marked the transition to integrated property documentation within the sole official parcel-based system, facilitating spatial data management and sustainable development. The cadastral survey revealed significant spatial and descriptive fragmentation due to incomplete spatial and legal documentation, unregistered administrative acts, and unregistered public property, which also affects the operational Cadastre. This paper contributes to the literature on the full transition from land registries to a Cadastre, and its impact on spatial data management and overall land administration.

1. Introduction

Property ownership, exploitation, and land use are closely linked to human presence, as they provide all the necessary conditions for sustainable living and social development. Archaeological evidence spanning a broad period from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages confirms that land use and management has been a key issue since ancient times. Records on land morphology and land surveys, land parcels, cultivations, taxes, etc., that have come to light through archaeological research and excavations highlight the importance of land use, land management, and most of all, land documentation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. However, until the Middle Ages, land ownership was the exclusive privilege of a few privileged lords and those around them through the development of feudal systems, especially in Europe.

Within the feudal system, the notion of property emerged in social and economic aspects at first [8,9], setting the origins of private property [10], originally as serfdom [11], whilst the notion of private property is clearly defined in Byzantium [12] as the continuance of the Roman Empire legislation clearly described in the Roman–Byzantine Law (BLR) of Harmenopoulos [13].

The post-medieval period marked the end of feudal systems. Land ownership was no longer the exclusive privilege of the few, and gradually became a common practice for all, giving land an exchange value. This change from the exclusivity to universality of land ownership led to the establishment of the principle of numerus clausus as a basic legal practice on private property definition and exploitation [14,15,16], which consequently led to the definition of property rights as absolute rights exercised over property, both immovable and movable. Inevitably, there was a need for a solid technical/legal and legal/technical legislative framework in accordance with the new reality of the acquisition, possession, and ownership of land. Thus, property law was created, which defines the spatial/technical and descriptive/legal aspects of properties, and a bundle of rights exercised over them, and, in particular, the immovable ones that are directly related to the land.

Under property law, property rights are defined as the exclusive authority of individuals or legal entities to use and benefit from their property, and range from full ownership, absolute and complete control over a property, to easements and mortgages, and these rights can be created, modified, transferred, and extinguished [17]. Property rights are described in legal binding documents, deeds, titles, judicial decisions, and official administrative acts, and originally emerged in Europe, so as to safeguard mortgage systems [18]. Property rights could not be easily revoked [19], as they are obligatorily registered or transcribed in land registries, which are official and public archives accessible to everyone, and which operate under the principles of public faith, legal certainty, and equal treatment for each transaction and each party involved in property transactions [20].

Nevertheless, deeds and titles registered or transcribed in land registries focused more on the legal description of land and immovable property, with an emphasis on the detailed description of property rights or other legal restrictions and regulations on the use of land or immovable property in legally binding documents. Thus, land registries are considered as systems proper for the legal documentation of land and transactions over properties, depending on deferent legal origins and legal systems [18,21,22,23]. However, the spatial description of properties, which is inevitably correlated with their legal description, was still vague, leading to uncertainties about the real spatial status of properties and their geometric characteristics, which also led to uncertainties about their real legal status. Thus, the first cadastral maps with detailed information on parcels and their geometry and location, which were part of cadastral systems, appeared in parallel with land registers, mainly in Europe, North America, and Australia [24,25,26,27].

Since cadastral systems relate to properties that are legally documented in titles, deeds, and other legal documents that are recorded in land registers, they should therefore embody property rights as a bundle of rights with respect to regulations and restrictions imposed by public authorities [21,28]; public faith should also be safeguarded, as it is one of the fundamental principles of transactions with properties [29], as properties are legally documented and this documentation is obligatorily available to the public. In many European countries, both systems co-exist [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Still, land registries are considered as legal institutions safeguarding real rights [23] and public faith. However, they do not have qualitative and accurate data on the geometry and spatial aspects of properties, so their integration into cadastral systems, especially in terms of the legal security of rights, is complex and challenging over time [38,39,40].

In today’s rapidly changing world, where urban growth puts pressure on agricultural land, land reserves, forests, and wildlife areas, a solid cadastral infrastructure is the key to efficient and effective integrated land management, while ensuring sustainable development [41,42]. According to the International Federation of Surveyors, “a Cadastre is normally a parcel based, and up-to-date land information system containing a record of interests in land (e.g., rights, restrictions and responsibilities)” [43]. Hence, a modern cadastral system must contain legal information and documentation on property rights and ownership, detailed and precise geometric and spatial information on plots, land parcels, and complex properties, e.g., condominiums or separate ownerships, as well as rules and restrictions deriving from legislation on urban or spatial planning, environmental protection, etc., enhancing spatial data management and the overall land administration.

However, since modern cadastral systems are based on land registries mainly for the legal documentation of properties, which range from land parcels and plots, to condominiums and other complex properties, they need to maximize the accuracy of cadastral records at the spatial and legal level [37,44,45], improve the techniques of up-to-date cadastral data production [46,47], but above all include historical and still valid cadastral maps and diagrams of administrative acts [48] and topographic diagrams depicting land parcels and plots that have valid property rights described in valid titles and deeds that are transcribed or registered in land registers [49,50,51,52].

Both land registries and Cadastres are reviewed as Land Administration Systems, aiming not only at land documentation (legal and spatial), but land management and land governance as well, so as to achieve sustainable land organization, preservation, or natural resources, urban planning programming correlated with its implementation, and rightful land use and exploitation, safeguarding property transactions [53,54,55].

In the case of Greece, land registries, functioning as a person-based system operating since 1836, are completely replaced by the parcel-based system of the Hellenic Cadastre, established in 1995, through an ongoing transition. The peculiarity of this transition is that the Hellenic Cadastre is the only official property documentation system after the completion of the cadastral survey for its creation in a particular area. The completion of the cadastral survey signalizes the operational Cadastre stage through the cadastral offices. In the operational Cadastre stage, the operational status of land registries is suspended; they are completely replaced by the cadastral offices, which also maintain land registries’ archival repositories.

Herein, this transition from land registries to the Hellenic Cadastre is presented. As the land registry system is completely replaced by the Hellenic Cadastre system and cadastral offices, challenges in the overall operation of the cadastral offices and in the process of correcting inaccurate and incorrect cadastral records and problematic but transcribed to land registry titles must be met.

Furthermore, the latest legislative reform, which provides for the completion of the cadastral survey in the operational Cadastre stage, makes unique the case of the Hellenic Cadastre, as not only completely altering the land administration system, but moreover taking place within the operational Cadastre stage.

This paper aims to contribute to the existent literature on land registries and Cadastres, in terms of property documentation, spatial data management, and land administration policy enhancement. It focuses on the difficulties and the challenges posed by the full transition from a person-based to a parcel-based system in Greece, which is unique, and the effects of this transition on spatial data management and the overall land administration policies.

2. Methodological Framework

In Greece, the parcel-based system of the Hellenic Cadastre completely replaces the person-based system of land registries, making the Greek case unique, as the two systems do not operate in parallel. Thus, the Hellenic Cadastre functions first of all as a solemn system for the implementation of Greek property law, the documentation of properties and property rights, the safeguarding of property transactions, and as a land administration system. The Hellenic Cadastre has to follow the strict legal and technical regulations of the Greek property law; therefore, it is incumbent on the obligatory verification of titles, legality, and corrections, including the spatial ones, so as to be approved for registration. Submitted titles to the HC have to be verified for their legal and technical/spatial status, which spans over time and is correlated with other legal documents.

By acknowledging the uniqueness of the Hellenic Cadastre, the transition process from the one system to the other is directly impacted by the following:

- Territorial succession of Greece, primarily by the Ottoman Empire, especially in land classification, categorization, and management;

- The legal provisions on property ownership granted in respect to social conditions;

- The selected system on property documentation and transactions safeguarding, with respect to the legal framework for the definition of properties and property rights;

- The relevant legal frameworks determining restrictions and regulations imposed on properties, which have impacted land administration and land management through large scale interventions.

Based upon the aforementioned, the methodological approach consists of the following distinct stages:

A. Identifying the procedures for securing property in the modern Greek state, related to the inheritance of territories, mainly from the Ottoman Empire, and the chosen legal system for documenting and securing property and property rights through the land registries that also aimed to serve land administration processes (Section 3).

B. Identifying the cadastral procedures that were carried out prior to the selection and implementation of the Hellenic Cadastre, chosen in 1995, and have had a catalytic effect on ownership and land management; identifying the basic characteristics and procedures for implementing and operating Hellenic Cadastre; and identifying the definition of the cadastral parcel that is directly correlated with properties described in a succession of legal documents created outside the Hellenic Cadastre, but which must be must incorporated into it (Section 4).

C. Comparing the two systems, land registries and the Hellenic Cadastre, and organizational schemes, which are based on different foundations (Section 5). Through this comparison, the following goals are outlined:

- i.

- Identify the spatial and descriptive fragmentations and inconsistencies of property documentation, due to flaws on the organizational scheme of land registries, revealed by the Hellenic Cadastre;

- ii.

- Highlight the first comprehensive documentation of public property throughout the country, with a view to its effective protection and use;

- iii.

- Identify ad hoc and on-the-fly procedures, incorporated into the cadastral legislation, that arose from the initiation of the implementation of the Hellenic Cadastre, aiming to improve the effectiveness of the system adapted to the Greek property law provisions;

- iv.

- Identify procedures to enhance the role of the Hellenic Cadastre as a spatial data management system linked to the rigorous legal status of the records it contains and maintains.

D. Emphasizing the complexity of this transition and the need for systematic research, especially for the precise spatial documentation of cadastral parcels in relation to the legally binding documents that describe them and were created outside the Hellenic cadastral system (Section 6).

3. Securing Ownership and Property Rights in the Modern Greek State

3.1. Territorial Evolution of Greece

Greece is located in the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea, in the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula, in south-eastern Europe, and covers an area of 131,957 square kilometers. According to the official census of 2021, the population is just under 10.5 million.

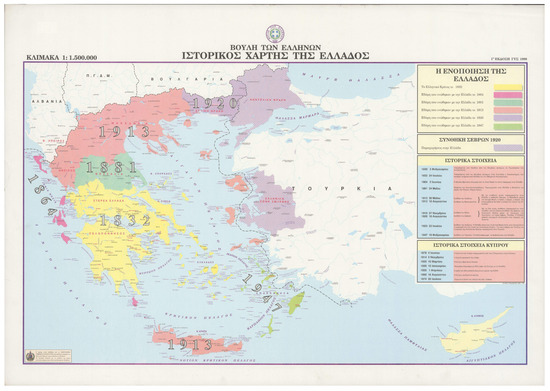

With the exception of the Ionian and Dodecanese Islands, the territories of Greece were acquired by the Greek state through the process of succession from the Ottoman Empire over a period of more than 120 years, from 1831 to 1923. The Ionian Islands were ceded by the United Kingdom to the newly crowned King of Greece in 1864, while the Dodecanese Islands were incorporated into Greece following the 1947 Treaty of Paris between Italy and the Allied Powers, shown in Figure 1. This long-lasting territorial succession resulted in different definitions of property rights and different legal and technical documentations of property rights and plots, land parcels, and complex properties of the successively integrated annexed territories. Both the Ionian Islands and the Dodecanese Islands had their own distinct legislation on property definition, ownership, and property rights. The Ionian Code and the Italian Civil Code, combined with the Dodecanese cadastral system, respectively, provided the foundation for these legal frameworks.

Figure 1.

Territorial evolution of Greece (Source [56]).

In accordance with the Ottoman legal system, all lands within the Ottoman territories were considered the property of the Sultan, the Ottoman Emperor. The Sultan was the only authority that could grant limited rights for land exploitation to its citizens and enhanced rights to religious bodies and recognized charities. In the early 17th century, a reform of the land administration system led to the establishment of the Çiftlik System. By this reform, the Sultan could grant tenure rights for land cultivation, typically ranging from 6 to 12 hectares including the surrounding settlements, to his high-ranking military officers, under the condition that these rights could only be inherited by their sons [57].

By the time of the Greek Revolution in 1821, the legal status of land in Greece was divided into five categories, according to use and possession rights [50]:

- (a)

- Mulk/Mulki Land: private land of relatively limited surface, consisting exclusively of buildings, wineries, or beehives, forming enhanced surface rights and subject to free and informal transfer.

- (b)

- Mirrie Land: public land consisting of fields for cultivation, meadows, and forests. A limited right, equivalent to today’s easement, the tessaruf was granted by official titles.

- (c)

- Vakuf Land: land granted to monasteries and other religious bodies or charities, its use and exploitation served charity purposes, was not eligible for property transactions, consisting of arable land, forestry, and residential land.

- (d)

- Metrouke Land: land granted to settlements and villages for common use spaces like roads, squares, etc.

- (e)

- Mevat Land: unused or abandoned land, e.g., mountains, hilly/mountainous and stony places, for which the Sultan had both tenure and ownership, exempt from any transaction.

A Çiftlik was typically comprised of Mulk, Mirrie, and Metrouke land, resembling a feudal estate, while multiple individuals could also possess Mulks.

The Çiftlik System and the Ottoman Empire land categorization has a significant impact on land management and land administration in Greece, playing a crucial role in the establishment of valid and solid property rights that are still the subject of legal battles between individuals and the Greek state.

In 1829, the Ottoman Emperor, acknowledging the formation of the Greek state, passed an act for the Attica region. The act formally recognized and granted to the Muslim Ottomans full proprietary rights over Mulk, Mirrie, and Metrouke lands, including the the Çiftliks and all the then real property rights in general. Thus, public land was effectively converted into private property.

The London Protocol (22 January/3 February 1830) that finalized the terms of Greece’s independence and its succession over the Ottoman Empire covered the mainland regions of Peloponnese and Central Greece, the island of Evia, and the island complexes of Saronic Gulf, Cyclades, and Sporades. The Protocol stipulated that Greece, as the successor state of the Ottoman Empire, and the Ottoman Empire, were obliged to respect existing private properties and property rights both of Greek origin and for Muslim Ottomans living in the territories of the then newly formed Greek state. In accordance with the Protocol’s provisions, Muslim Ottomans were divided into those willing to remain in the Greek state and those wishing to depart from the Greek state. The latter were given the permission to sell their properties to Greeks within a one-year period. The first private properties in Greece originated from the sale of Ottomans departing for Greece.

Furthermore, abandoned Mulk, Merrie, and Metrouke land, as well as Mevat land, became the ownership of the Greek state, recognized as public property and placed under the strict protection of the state. Active Mulk, Merrie with tessaruf, and Metrouke land, along with the Çiftlik, were formally recognized as private properties with full ownership rights, rendering them eligible for property transactions. Vakuf land was recognized as the legitimate private property of monasteries, religious bodies, and other charities [58]—but only for those active at the time of London Protocol enactment—and was also placed under the State’s strict protection. The Vakuf land of non-active bodies was automatically transferred to the Greek state and recognized as public property.

In 1864, the Ionian Islands were ceded to Greece by Great Britain, becoming Greece’s territory. Already from 1841, the Ionian Civil Code was enacted, and consisted of three books, one of which was the Ionian property law. The Cession Treaty provided for the status of private and communal (public) property, whilst “all non-private property is property of communes and communities”. The general provision for “all non-private properties recognized as communal ones” resulted in a vague spatial identification, resulting in disputes between the municipal authorities and individuals to this day.

Following the 1881 Convention of Constantinople, Thessaly was annexed into the Greek state. Çiftliks were predominant in Thessaly and were under the administration of Çiftlik supervisors, a position usually held by a Greek appointed by the Ottoman authorities. Agricultural land was cultivated by tenant farmers who were granted small houses. After Thessaly’s annexation, the Greek Çiftlik supervisors were granted full ownership rights, while the tenant farmers retained no rights over the land. This resulted in the Agricultural Issue and the demand for the distribution of public lands to farmer tenants. Distributions started in the mid-1880s and gradually spanned to the then-Greek territories. However, as tensions over the Agricultural Issue persisted, especially in Thessaly, the 1907 legislation reform was enacted, which foresaw the expropriation of large properties, including Çiftlik and monasteries land, and this land would be distributed to landless people and tenant farmers.

The victorious Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, combined with Greece’s victory in the First World War, resulted in new territories being annexed in Northen Greece (Epirus, Macedonia, and West Thrace), North Aegean Islands, and Crete, and agricultural reforms sped up. The 1917 agricultural reform secured the legal framework on agricultural land expropriation for the rehabilitation of landless people. The reform’s core was the total prohibition of the sale of agricultural land owned by the public or state legal entities and for more than 20 hectares for land belonging to individuals, without prior approval by the Greek state and the Cabinet. This provision still impacts transactions on outer-urban and agricultural land, mainly in the Attica Prefecture.

The Asia Minor Catastrophe, and the resulting 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, led to the exchange of territories and populations between Greece and Turkey. More than 1,500,000 refugees of Greek origin from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace sought refuge in Greece. The urgent need for refugee rehabilitation resulted in the implementation of a large-scale and comprehensive land distribution program in the recently annexed territories and the redistribution of land within the existing boundaries of the Greek state.

The newly acquired lands, and especially the Çiftliks, were meticulously surveyed and allocated to refugees who settled in designated refugee settlements. These settlements were strategically located in proximity to agricultural land and farms, which were also distributed. In parallel, large-scale expropriations of large agricultural properties of “old” Greece and Çiftliks were also undertaken, and the agricultural land was distributed to refuges, landless people, and tenants. The distributed, private, urban, and agricultural land remained under the strict protection of the state. Until 1968, all transfers and transactions on distributed land were prohibited, or required the prior authorization of the Minister of Agriculture, except in the case of inheritance rights. Those land distributions were the first large-scale, systematized, and universally applicable land management policies for achieving social cohesion and were based on the most accurate spatial data available at the time.

In 1947, and after the end of World War II, the Dodecanese Islands were transferred to Greece. The largest islands, e.g., Rhodes and Kos, were under the 1929 Italian Dodecanese cadastral system, which documented the then-Italian-owned public land and private land, and is still operational.

3.2. Byzantine–Roman Legislation and Land Registries

The first Governor of Greece, I. Kapodistrias, established the institution of “Mnimones” in 1830. “Mnimones” were civil servants responsible for drafting and archiving titles related to land transactions and wills, an institution with roots in Byzantine times.

After the assassination of Governor Kapodistrias in 1831, King Otto came into power. King’s Otto administration wanted to introduce a Civil Code, including property laws, and in 1834, replaced Mnimones by Notaries, public officials responsible for drafting and archiving titles and wills. In the interim period of the preparation of the Civil Code, the pre-existing Byzantine–Roman legislation, the Harmenopoulos’ Exabiblos, was established as the official legal framework, regulating, amongst other things, property rights, property documentation, and in general, land administration and management [59]. Byzantine–Roman legislation (BRL) ownership, and in particular full ownership, is an absolute and universal right on properties, while other property rights are as follows: usufruct easements, mortgages, encumbrances, surface rights, water rights, plantation rights, separate ownership rights, and adverse possession property rights.

The BRL also included legal provisions correlated with technical provisions for urban planning and building regulations, forest administration, the supervision of monastic real estate and public property exploitation, and public land distribution for agricultural exploitation [50,60]. Those provisions were pivotal in the early stages of land administration in the modern Greek state, imposing restrictions on property exploitation and the exercise of property rights [50,60].

As the institutional provisions of the BRL were too general and could not adequately meet the needs of coherent land administration, and in particular the correlation between spatial data and legal rights or constraints, they were gradually specified and detailed in laws and regulations that affect the spatial and legal status and documentation of properties and property rights. Legislation on public and private forest indexes, on meadow indexes, on urban planning, and urban planning implementation, especially for public space creation from private land, were enacted between 1833 and 1840. In 1833, taxation for grazing in state-owned meadows was enacted, while in 1836, two important royal decrees regulating land administration and development, i.e., “implementing Athens’ Urban Plan” for urban areas and on “private forests and meadows”, were also enacted. In the case of urban plans, rightful owners, with proven ownership by official titles, had to contribute land for the creation or improvement of public spaces, e.g., a road network, while limitations on property exploitation and building activities were imposed, archived at the respective municipal department for urban plans. For the first time in the modern Greek state, land contributions for the creation of public spaces were obligatory and free of compensation (up to an amount) for urban planning implementation, a legislative practice that, nowadays, is constitutionally foreseen. In the case of private forests and meadows, individuals and legal entities, e.g., municipalities or monasteries claiming ownership, were obliged to declare them before the Ministry of Finance by providing rightful ownership titles, issued by the preceding Ottoman authority, or by the Greek state in the case of approved transactions by departing Muslim ottomans (e.g., in Attica).

The flagship legislation of that period was the establishment of a parcel-based cadastral system, under the responsibility of the Ministry of Finance. The 1836 royal decree on the “Cadastre” foresaw that all rights exercised over properties and land, along with mortgages and encumbrances, should be recorded in cadastral tables correlated with cadastral maps. Also, in 1836, the official public mortgage offices were established at the headquarters of the district courts. The offices registered mortgages on both immovable and movable property. The original plan was for the mortgage offices to be linked to the Cadastre. However, Greece’s rough terrain and landscape was considered prohibitive to the completion and establishment of the Cadastre; thus, the public notaries were unable to safeguard public faith during property transactions, and public land and public assets were already vulnerable to encroachment.

The 1856 law “On Property Ownership, Transcription, etc.”, established the land registers, a person-based system that introduced obligatory titles transcriptions/mortgages as the only appropriate system to ensure public faith, publicity, and public security on property transactions, under the publicity principle. A land registry is a public office, established at the seat of the local court or the court of the first instance, under the responsibility of the Ministry of Justice and the local prosecuting authorities acting as the superior authority. It has a specific territorial jurisdiction, coinciding with respective administrative boundaries of a municipality or of municipalities and commune group, and the system is characterized as decentralized and quasi-autonomous for each distinct structure. There is no relevant map for the territorial jurisdictions, only official descriptive documentations in each local prosecuting authority and the component local land registry of the area of responsibility.

All privately owned properties and all respective property rights, legally established and guaranteed, ought to be described in legal binding documents and titles, issued by either public notaries or by public authorities, public institutions, and courts. All individuals or legal entities with legitimate property rights are recorded in nominal lists that are linked to transcriptions and public registration books, accessible to all. Titles pertaining to the rights of ownership, usufructs, easements, and other forms of restricted ownership rights are transcribed in the transcription books. Mortgages, burdens, and other encumbrances are registered in registration books.

Both transcriptions and registration books are archived in the component land registry, under the sole responsibility of the land registrar, the registry’s supervisor, according to the principle of time priority, i.e., the title or mortgage that is submitted to the registry is indexed in the respective books first. Any new indexation in the registry’s books results in the updating of the persons’ nominal list. Thus, anyone who wishes to consult the registry’s public books can access them only through the entity/person index.

Titles and all relevant legal documents ought to describe the legal status of the property, e.g., the ownership status, mortgages, and encumbrances, along with the description of some basic spatial characteristics such as boundaries, areas, neighboring property owners, and things that are firmly attached to it (e.g., buildings, trees, etc.). There is no obligation for the in-detail geometric/spatial depiction of the property to any official or other reference system, as the land registries do not archive topographic maps or diagrams.

Public lands and assets, e.g., forests, meadows, and beaches, are exempted from registration in land registers and are recorded in official catalogues/indexes originally of the Ministry of Finance. Between 1930 and 2009, records on agricultural public lands, public forests, and meadows were under the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture, while all other public lands were foreseen by the Ministry of Finance and the respective Ministry, e.g., in the case of archeological sites or health infrastructure, with the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Health, respectively.

Monastic lands, properties, and assets were also exempted from registration in land registers, as they are under the supervision of the Ministry of Finance and were registered in special public catalogues/indexes of the Hellenic Church Technical Department. No detailed maps or equivalent cadastral products were created to support the indexes on public or monastic properties, even though those indexes are legal binding official governmental documents and acts. Disputes over public ownership and monastic ownership were constant; thus, the church and the Ministry of Finance were separating their properties by presidential decrees on selective areas, beginning in the 1930s and ending in 1952, and were also exempted from registration in land registries up until 2014.

The exemption of the registration of public land and properties to the component land registry facilitated adverse possession in public and monasterial properties, especially in agricultural areas. In 1915, legislation on public property protection prohibited any adverse possession on public or monasterial land and properties unless ownership could be proven by titles transcribed in land registries by 1885 at the latest.

The person-based operational scheme of land registers does not facilitate the correlation between the legal status and the spatial/geometric status of properties, making it impossible to actually locate a property, its neighboring ones, and their owners. Maps or topographical diagrams are not submitted to land registers and can only be found in the archive of either the notary or the public authority that issued the title and had obligations for the draft. Excluding public and monastic lands from land registries does not only fail to facilitate their spatial documentation, but also fails to protect them from being encroached upon or illegally possessed.

3.3. Property Law Enactment

The Greek property law (GPL), book 3 of the Greek Civil Code, was enacted in 1946, shortly after the end of World War II. Unlike the preceding Byzantine–Roman legislation, the GPL defines only four absolute property rights: ownership, easement, encumbrance, and mortgage. The GPL also foresees that properties and property rights may be subject to restrictions deriving from legislation on urban planning, transport planning, building regulations, codes, etc., which are enacted for the general good and safeguarding of public interest, creating a sphere of public power that limits their full exercise [61].

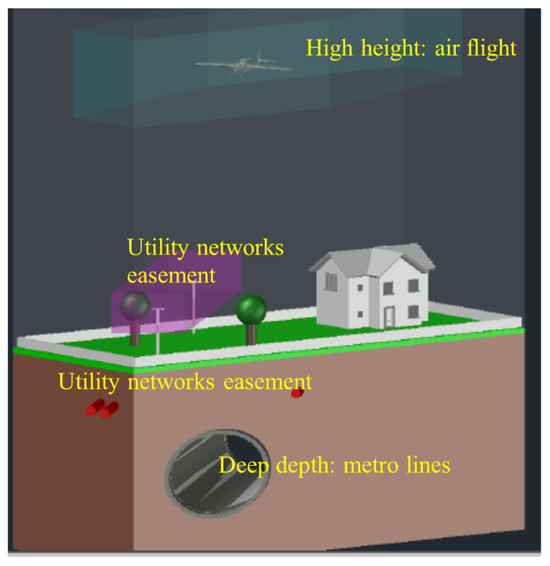

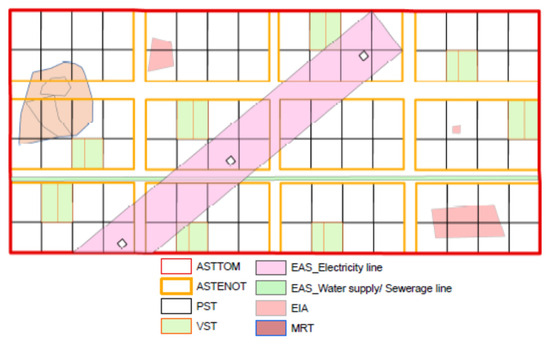

Property rights are a bundle of rights, as “the owner of the thing can, as long as there is no conflict with the law or the rights of third parties, use it as the owner pleases and exclude any third-party action on it” (Article 1001). The use of property, land parcels, or plots is restricted by legislation on urban and spatial planning, the development of utility networks, the development of transport networks, or air traffic rights [20] (Figure 2). In the case of air flights in high heights and the underground development and operation of transport networks in deep depths, the owners are exempt from any form of compensation [61].

Figure 2.

Property rights and restrictions as defined by GPL (source [20]).

Furthermore, the GPL introduced rules and restrictions on the use of property and land exploitation, e.g., separate ownership in the case of condominiums that are referred to in the Greek legal framework as “horizontal/vertical/vertical combined with horizontal division”, ownership on quarries, mines, wells, and underground waters. It also kept provisions on adverse possession, setting possession rights for a bona fide 10-year period and for a non-bona fide 20-year period, and adverse possessions sought to be acquired by court decision, but in many cases, the juridical procedure is bypassed and those rights are created via titles transcribed to the respective land registry, acquiring quasi legalization.

The GPL legislator, Athens Law School professor George Balis, stated that the legal framework on property and property rights introduced in 1946 is inextricably linked to the precedent Byzantine–Roman legislation of Harmenopoulos. Balis adds that the BRL has served as the foundational binding legal document for Greeks to regulate their affairs from the late Byzantine era of the 14th century, through the Ottoman period, from the mid-15th century until 1832, and from 1832, when the modern Greek state was established, until 1946, the year in which the GPL was enacted [62,63].

3.4. Titles and Other Legal Documents Transcripted to Land Registers After GPL Enactment

The titles or other legal binding documents for transactions on land, properties, and property rights that must be transcribed/registered in Greek Land Registries are as follows:

- Official titles issued by public notaries for property transactions: sales, easements, pledges/mortgages, long-term commercial leases, leases in general, and inheritance succession that was not subjected to obligatory transcription by the precedent Byzantine–Roman legislation.

- Judicial decisions on property claims or mortgages.

- Titles granted/issued by the state after the completion of land distribution to refugees or landless persons or as a result of land re-parceling (the cadastral plans or maps of these acts are not transcribed).

- Titles granted by the state after the completion of the implementation of the urban plan expansion (the cadastral plan or map of this act is not transcribed).

Prior to transcription, the land registrar conducts a legal compliance review of titles and other legal documents submitted for registration. If the registrar identifies any legal defects, it reserves the right to refuse the transcription, e.g., the registrar could decline a title transcription in cases of the incomplete descriptive and spatial documentation of a property. As the spatial/geometrical documentation verification by the registrar is not feasible, attention is paid only with respect to the legal rules set by the GPL, resulting in the inability of fully safeguarding public faith and any bona fide protection [50].

Expropriations carried out by public bodies, and seashore and beach border lines defined and carried out by the Ministry of Finance, are exempt from transcription, as their publication in the official Governmental Gazette is considered adequate for the publicity of the act but could be noted in special books. Public forests and meadows are also exempt from transcription, and beginning in 2014, monastic properties ought to be transcribed at the component land registry.

4. Cadastral System in Greece

4.1. Cadastral Processes in Grecce, Before the Hellenic Cadastre

From the 1830s until the late 1870s, there was no significant cadastral activity in Greece. Official registration to the official catalogues of the Ministry of Finance was only obligatory for public and privately owned forests or meadows, including those of public legal entities, the church of Greece, monasteries, and municipalities. This registration was mainly descriptive, with no spatial/geographical reference or any relevant geometrical description [50,64].

The need to increase agricultural production for an adequate food supply, along with agricultural land tenant demands, led to the distribution of National Estates that started in 1871. The National Estates Technical Agency, Ministry of Finance, was responsible for National Estates distributions. National Estates distributions were not subjected to any official and analytical documentation, even though the entire distribution process was regarded as the first inaugural large-scale land administration policy in modern Greece in order to avoid social unrest. A total of 265,000 hectares was distributed through 357,000 titles granted by the state, covering the continental part of central and southern Greece, lasting for more than 30 years. Nominal titles were transcribed to the component land registry.

In the mid-1880s, the Greek government recognized that the absence of a reliable cadastral map posed a significant challenge to the distribution of National Estates. Without such a map, it was impossible to ascertain the actual land distributed or to delineate the boundaries of the distributed agricultural parcels. In 1889, the Geodetic Mission (NGM) was established as a result of the cooperation between the Hellenic Army and the Institute of Military Geography in Vienna. The GM was tasked with the production of the national cadastral map, overseen by Austrian officials, with the objective of determining the income of the Hellenic State derived from the distribution of public land and calculating tariffs and rational taxes. As the number of officials responsible for cadastral mapping was insufficient, the GM was limited only to geodetic, large-scale surveying and mapping activities, which were undertaken by its successor the Hellenic Military Geographical Service (GYS) [65].

4.1.1. Ministry of Agriculture Cadastral Surveys and Products

In 1918, as Greece had doubled its territory, there was an urgent need to distribute the newly acquired agricultural land in the newly annexed areas, in the context of the national agricultural reform. To facilitate the process, the Survey Agency of the Ministry of Agriculture (SAMA) was established in 1917, detached from the National Estates Technical Agency, and became the essential department of the newly established Ministry of Agriculture. From its early days, the SAMA was a body of rural and surveying engineers with scientific and technical backgrounds to carry out detailed topographic, mapping, and cadastral activities, so as to ensure the rapid and accurate distribution of full ownership rights of agricultural land to its rightful beneficiaries, through official administrative acts, resulting in state deeds correlated with detailed cadastral diagrams and tables, including both private and public properties [66].

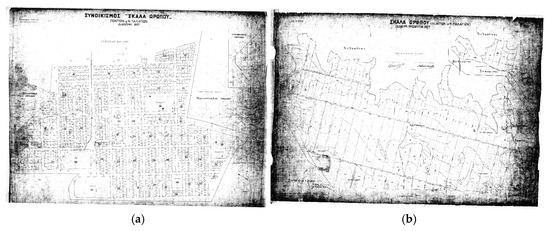

After the Asia Minor Catastrophe, the SAMA played a pivotal role in the rehabilitation of more than 1,500,000 refugees of Greek origin. The SAMA was also responsible for the distribution of agricultural land not only to refugees but also to tenants and economically vulnerable Greeks, in order to avoid collisions between the two groups. Distributions were carried out on the basis of detailed cadastral maps and cadastral tables, according to the provisions of the 1924 Agricultural Code [67]. The SAMA was also responsible for detailed agricultural settlement urban plans, so as to provide housing infrastructures. Each settlement plan also provided adequate public/common spaces to meet the social, economic, and recreational needs of its residents [50] (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

SAMA Official Cadastral Maps for Refuges Rehabilitation: (a) 1927 Settlement of Pontion and Palation, Skala Oropou, Attica region, (b) 1927 Agricultural Land of Settlement of Pontion and Palation, Skala Oropou, Attica (source [67]).

As there was a pressure for the rapid completion of distributions, the regional services of the SAMA worked on multiple and localized geodetic networks that were established all over Greece [48,68], which sped up the process of land distribution and also included official detailed cadastral maps. The official and nominal titles were signed by the Minister of Agriculture, after the act was published at the official Governmental Gazette. Abstracts of cadastral tables were transcribed in the competent land registry (within a period of 20–25 years), while the detailed and official distribution cadastral maps and cadastral tables were archived by the local or regional SAMA offices.

All SAMA land distributions, redistributions, re-parceling, and urban plans of settlement cadastral data are certified and official governmental acts, and are still legally binding and valid, and adverse possession is strictly prohibited. The SAMA’s detailed cadastral maps and tables are still active operational archives, combining technical and legal documentation for the agricultural and urban land of large parts of Greece’s territories. Any unauthorized sale and/or subdivision of land distributed before 1968, officially transcribed in land registries, or unofficially documented by a private agreement with a secure date, ought to be verified by the local court.

After the completion of urban and agricultural land distributions, in the early 1950s, the SAMA continued its work by re-parceling existing agricultural land distributions fragmented due to heritance rights or agricultural land that had not previously been distributed by the state, following the will of the landowners.

Any SAMA’s work was, and still is, essential for policies on agricultural land management and administration, ensuring the viability of rural communities, especially in periods of uncertainty and political instability, and achieving overall social cohesion and sustainable development.

4.1.2. Urban Expansion—Urban Plans

Urban expansion in Greece is also a highly regulated and strict process, and it is conducted through the use of detailed cadastral maps and tables.

From 1836 to 1923, the legal framework foresaw local adjustments of plots, recorded by the municipal technical department, with plot owners to be subjected to land contributions for public and common space creation. The urban plan diagram, usually of a 1/1000 or 1/2000 scale, and the corresponding local building regulation approval and publication in the Governmental Gazette, was consider adequate for the plan’s implementation and the safeguarding of property rights, especially for public and common spaces.

The 1923 reform by the Legislative Decree on urban plans of cities and communes of Greece, established a more rigorous and consistent process. Any approved urban plan ought to be followed by a detailed implementation plan, with the same scale as the plan, usually 1/1000, archived by the municipal technical department. From 1923 until the late 1930s, the majority of urban expansions, especially in major urban areas like Athens, were undertaken by shareholding urban development companies. After those companies had in their possession wider peri-urban areas destined for urban expansion, they were obliged to draft and approve the urban plan, in cooperation with the respective Ministry on urban planning. After the publication of the urban plans in the official Governmental Gazette, all public and common spaces became property of the municipality or the commune, and the companies were able to sell plots. The construction of all the necessary public facilities, e.g., roads, sewage networks, schools, etc., was the company’s responsibility. Titles on plot sales were transcribed to land registries, whilst the possession on public or common areas was secured upon the urban plan’s official publication.

After the end of WWII, urban expansion was undertaken by building associations or groups of individual land owners. The association members were paying for shares, and the association was then able to buy land; following this, urban plans were approved and plots were given to members by contracts transcribed in land registries. The group of individuals simply had to proceed with urban plan drafting and approval. Many of those new urban areas were created in the vicinity or within forests (public or private), after official permission was obtained. Plans approved by groups of individuals could be partially implemented through the issue of arrangement plans. Arrangement plans included the parts of the private property given for roads and public or common space creation and the owner’s financial contribution to the implementation. Arrangement plans consisted of cadastral maps, non-referenced in the official state reference system, and cadastral tables that ought to be transcribed in the component land registry. The partial implementation, via arrangement plans, led to problematic implementations. In several cases, the implementation was halted, as there was a reluctance to pay the relevant financial contribution by the individuals. Thus, the urban space became fragmented, with many spatial inconsistencies.

Following the 1975 Greek Constitution, the legal framework on urban planning and urban expansion was modified in 1983 by law 1337, and any urban expansion was initiated strictly by the municipalities and the Ministry for the Environment; it is approved by Presidential Decree, after the Council of State official review, and is subjected to a rigorous technical and legal process, which includes the following:

- Property owners must submit their official titles, including the official certificate of transcription issued by the competent land registry.

- Property owners are required to contribute land for the implementation of the urban plan, for the creation of sufficient public and common spaces, in accordance with Constitutional Provisions, Article 24. Up to a percent, set by law 1337, land contribution is not considered expropriation, but as necessary for public and common space creations, and is not subjected to any compensation.

- For land contribution and the final plot area, an official cadastral map is drawn, correlated with the official cadastral table, depicting the final boundaries of the plots in relation to public and common spaces, and the building regulations (e.g., minimum plot area and dimensions to obtain official building permit) under the official Urban Plan Implementation Act (UPIA). The cadastral map is referenced to the official Greek coordinate system, e.g., TM3, or GGRS87 after mid-1990s. The cadastral table includes, for each proprietor, the compulsory land contribution and the finances that are calculated as a percentage of the final plot area.

- The final UPIA is approved by the regional governor (or its deputy). Subsequently, the cadastral table is transcribed in the relevant land registry, while both the cadastral map and the cadastral table are archived by the technical department of the component municipality.

- Any subsequent transaction on the final plot, such as a sale, should be harmonized with the official cadastral data of the act, including the actual plot boundaries and area. The subdivision of the final plot is contingent upon approval by the municipal technical department and is included in the official archive.

- Forests are excluded from urban expansion; therefore, the Forestry Administration grands its approval prior to urban plan approval.

Law 1337 regulated urban expansion and the UPIA cadastral data contributed, for the first time, to the transparency and equitable sharing of the obligations arising from the plan’s implementation, treating the under-expansion space as one spatial unit. The transcription of the UPIA cadastral table, which also included public and common spaces, facilitated the record of all property rights, including the municipal ones. The UPIA referenced to official state reference system cadastral plan, was easy to implement either by the technical department of the respective municipality or private surveying engineers.

4.1.3. Expropriations

According to the Greek Constitution, expropriation is in the exclusive competence of the Greek state. It is carried out exclusively by public bodies, authorities, and departments. The 1975 Constitution foresees that this is linked to projects of public interest for the state to achieve its public objectives more effectively. The owners are obligatorily compensated for the loss of their property. Typically, expropriations pertain to major motorways or highways, overhead electrical infrastructure, power stations, substations of alternating current (AC) and direct current (DC), underground water and sewage networks, general infrastructure, railway networks, airports, etc. In the case of underground utility networks and above-ground electricity networks, expropriations concern passing-through property easements, except electricity pylons, for which full ownership is compensated. Also, for the passing-through easements, restrictions on construction activities are foreseen within the easement zone; thus, official building permits must be approved by the public utility body/company prior to its approval by the responsible public authority on building permits [20].

Expropriations are cadastral procedures, based on a detailed cadastral map, with the geometrical characteristics of the land parcel or plot being correlated to a cadastral ownership table that includes the titles of the rightful owners and all things firmly attached to the ground, e.g., buildings or trees that are also subject to compensation. Until the mid-1990s, cadastral diagrams were not referenced to official state coordinates systems; thus, they were missing spatial accuracy. The cadastral data on expropriations are archived by the respective public body, ministry company, or agency. The Expropriation Code foresees that expropriation declaration, expropriation completion, and deposits to the relevant monetary compensation in the State Deposit and Loan Fund, are obligatorily published in the Governmental Gazette for publicity of the act [48]. Unless the compensation is deposited within and 18-month period, compensation is revoked. It is also revoked if the foreseen project is not implemented within a period of 18 months. The final amount of compensation is decided by a court, in which all rightful owners have to confirm their property rights through official documents in order to receive the compensation.

Expropriation registration in the component land registry is not obligatory and legally binding, but indicative, as the person-based system does not facilitate the identification of property owners per expropriated property (in some cases it is not possible). The Expropriation Code foresees that expropriation is fulfilled by the publication of its declaration and completion in the Governmental Gazette. Usually, expropriations are recorded in a separate index/record by land registers and are not linked to owners’ indexes. After receiving compensation, owners ought to update their personal indexes in land registers, but usually they do not proceed.

4.1.4. Seashore and Beach Border Line/Zones

According to a constitutional mandate, the GPL, and the component legal framework, seashore and beach zones (a strip of land behind the seashore) are public goods, owned by the state, and exempt from all property transactions [61]. Seashore and beach zones are defined by boundary lines through an official administrative act issued by the Ministry of Finance. This act includes a detailed topographic diagram depiction, not only of seashore and beach lines, but all structures within the zones or structures that may be built in the sea, e.g., harbor construction [20], which is not correlated to any descriptive data on supposed private ownerships.

The administrative act is published in the Governmental Gazette, guaranteeing the publicity of the act. In cases of private property rights that are exercised within the zones, those are considered under expropriation, and compensation is due within 18 months of the official publication, provided that owners have legal and valid titles. The topographic diagram of the act is referenced at the national coordinate system (that was in in force when the act was officially issued) and is archived at the component department of the Ministry of Finance as an active archive.

4.2. Greece’s Cadastral Systems Prior to Hellanic Cadastre

Since the mid-1920s, there was no robust framework on Cadastres in Greece, as the 1836 legislation on Cadastres was inactive. In 1923, the law on the “Cadastral Survey of Urban Properties” was launched, one year after the arrival of the Minor Asia refugees in Greece, and provided for the following:

- The creation of a cadastral map via a detailed cadastral survey of all urban properties (the term “urban” applies for cities, towns, settlements, under development or future urban areas, carried out by civil servant surveyors). The creation of a cadastral property book for citizens to obligatorily declare their urban property.

- The establishment of a public cadastral service and cadastral archive to maintain, update, and modify the cadastral map.

- All surveyed properties are given a unique cadastral number.

- Any change in the status or the geometric characteristics of a property by an official act or title is recorded on both cadastral map and books.

- The recording of any other technical information on property status, e.g., existing buildings, building construction, or demolition via official building permits and any other construction affecting the legal status of the property.

- The official approval of the cadastral map made mandatory the attachment of a cadastral map; otherwise, the transaction is invalid.

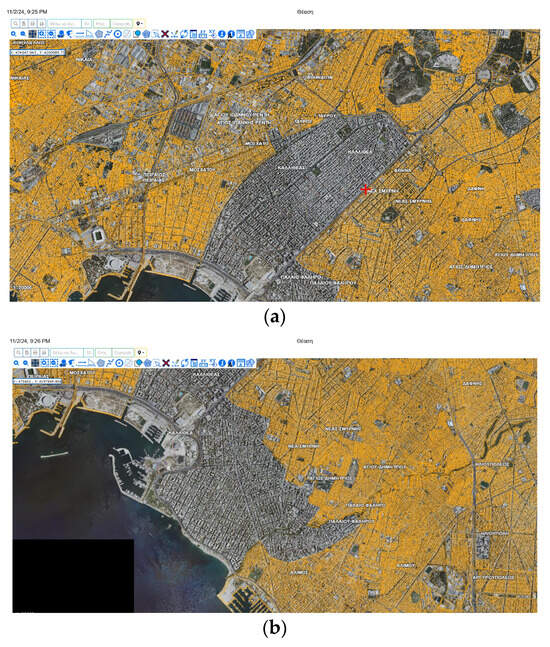

Due to Greece’s political, social, and economic conditions in the 1920s, the cadastral survey was completed in two residential areas in Attica, and parts of the municipalities of Kallithea and Palaio Faliro, forming the “Operational Cadastre of the Capital”, covering 665 blocks at Kallithea and 343 blocks at Palaio Faliro, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

“Cadastre of the Capital”, Municipality of Kallithea (a), Municipality of Palaio Faliro (b), shown as no cadastral parcel (orange) areas (source: Hellenic Cadastre, accessed on 30 October 2024).

The islands of Rhodes, Kos, and a part of Leros, which were annexed by Greece in 1947 as a part of the Dodecanese Islands, also have a functioning cadastral system, the Dodecanese Cadastre. The Dodecanese Cadastre was established during the islands’ Italian occupation between 1912 and 1943, by the Governmental Decree 132/1929, which remained in force by law 510/1949. The Dodecanes Cadastre includes a public register of properties (plots and land parcels) correlated with cadastral maps and detailed diagrams, for all properties, private or public, covering an area of more than 140,000 hectares. The map scale is 1/2000 for urban areas and 1/5000 for non-urban areas, whilst the diagram scale is 1/100–1/200 and 1/1000–1/2000, respectively.

The Dodecanese Cadastre has resulted in numerous disputes, particularly in properties neighboring seashore and beach border lines/zones and other public properties, as it was chosen by the Italian administration to conduct a form of expropriation without compensation, driven only by boundary determination. It also foresees a 5-year period of record finalization, indicating the efforts of the administration on expropriation practices.

4.3. The Hellenic Cadastre

The current legal framework for Greece’s official cadastral system, the Hellenic Cadastre (HC), was enacted in 1995, by law 2308 on “Cadastral Survey for the Creation of HC”, and further supplemented in 1998 by law 2664 on “the Operation of the Hellenic Cadastre”. As mentioned above, the Hellenic Cadastre completely replaces the land registry system, upon cadastral survey completion.

In contrast to the land registers, the HC is a “parcel-based system”. It comprises a comprehensive cadastral map correlated to a detailed cadastral table of owners/beneficiaries, incorporating information on titles, rights, land use, and types of property, organized in cadastral books that consist of cadastral sheets. The HC cadastral map is referenced to the current official Greek reference system, GGRS87 (EPSG 2100-Greek Grid).

According to law 2664 in the HC, “all the necessary information, both technical and legal, is recorded, aiming at determining the precise and in detail boundaries of land parcels and the publicity of property transactions, registered in the cadastral books, to ensure public faith, protecting also every bona fide party that makes transactions with properties based on those cadastral records”. The incorporation of additional technical information that will facilitate the sustainable organization and development of Greece, such as official administrative acts and decrees on land uses, urban planning, building factors, etc., is also foreseen, but not activated yet.

The Hellenic Cadastre is run by the Hellenic Cadastre public body (former National Cadastre and Mapping SA, and Cadastre SA). From 1995 until 2020, the Hellenic Cadastre was under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environment and Energy. A legislative reform in 2020 transferred its jurisdiction to the Ministry of Digital Governance.

The HC is based on six fundamental principles that are set to guarantee the seamless and smooth transition from the land registers (law 2664/1998):

- A parcel-based structure for recording and modifying cadastral information, which necessitates the continuous production, modification, and updating of cadastral maps and diagrams.

- Legal compliance prior to the approval of any new transaction recorded in cadastral books.

- The registration of new transactions in cadastral books follows a first-come, first-served basis (time priority principle).

- Cadastral books and all relevant information and data contained therein are publicly available to everyone.

- The protection of the public faith in property transactions and bona fide protections.

- The suitability of the NC as a receptive system for the registration of any other relevant information (technical or legal) pertaining to properties, property rights, and so forth, in accordance with the open Cadastre principle.

Legal compliance prior to the approval of any transaction, time priority, publicity, and public availability of cadastral books are principles inherited by the land registry system.

The HC database (HCDB) is a cadastral database structured as a two-dimensional spatial database correlated with a descriptive database. The 2D cadastral spatial DB contains the precise spatial and geometric representation of each individual parcel/plot that is determined as a “cadastral parcel” at the PST spatial level, while other spatial features that define spatial objects or spatial relationships/restrictions/regulations, such as boundaries of administrative acts, boundaries of administrative and cadastral units, e.g., administrative units (prefecture, municipality, commune), cadastral sectors and cadastral units, easements, the vertical separation of parcels, etc., are represented at the equivalent spatial information levels [69] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hellenic Cadastre 2D spatial DB scheme (source [69]).

Each cadastral parcel of the PST (Figure 5), is assigned a unique 12-digit code, i.e., a Hellenic Cadastre Code Number (KAEK in the Greek language), while all other spatial features, objects, or spatial relationships/restrictions/regulations of the other spatial features are also given a specific KAEK, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cadastral object coding, HCDB (author’s elaboration from HC technical specifications).

Thus, this treatment of the land parcel as a distinct object with a spatial layer, PST, defines the notion of cadastral parcels, as the unique unit of the parcel-based system of the Hellenic Cadastre. The PST spatial level also includes spatial objects, such as man-made or natural boundaries, e.g., roads, rivers, etc., classified as special areas (EK in Greek), and forms the basis of the 2D spatial cadastral bade, through the assignment of its unique KAEK. Other property rights are included in different spatial layers: exclusive uses in the VST spatial layer, easements in the EAS spatial layer, mining rights in the MRT spatial layer, and special property objects in the EIA spatial layer, while they maintain the KAEK assigned in the fundamental PST spatial layer. The grouping of cadastral parcels of the PSR spatial layer and of the other spatial layers, VST, EAS, MRT, and EIA, into cadastral units and cadastral sectors, separated by land parcels of special areas, EK, facilitates the spatial organization of the 2D spatial cadastral database. The inclusion of polygons defining administrative boundaries, Dbound, facilitates the spatial correlation of land plots and other property rights to real estate with the spatial extent of administrative acts and the performance of spatial controls, correlations, or joinings, so as to ensure their spatially correct registration in the Hellenic Cadastre system. Thus, the HC 2D spatial cadastral database incorporates not only spatial elements but also legal elements that are distinctive spatial objects, correlated with specific cadastral parcels of the PST spatial layer. The descriptive cadastral database contains all the necessary legal and descriptive documentation for plots and land parcels, including six main categories of entities:

- Beneficiaries: an individual or a legal entity with rights over one or more land parcel, plot, or any immovable property.

- Rights: Ownership, easement, mortgage, or encumbrances according to the Greek Property Code [61]—rights in rem and all other valid rights—transcribed rights of the precedent Byzantine–Roman legal framework [20,61], other rights, like rights on mines, transferable Development Rights [70], surface rights (re-instated for public owned properties in 2011), rights of customary law in various parts of Greece (e.g., Cyclades Islands), and all other rights in general that were not transcribed in land registries.

- Documents: legal binding documents, e.g., titles, etc., transcribed in land registers, court decisions on property rights or mortgages registered in land registers, long-term leases also registered in land registers, administrative acts either registered in land registers, e.g., land distribution or UPIA, or published in the Governmental Gazette, e.g., seashore and beach border line/zone determination, expropriations, etc.

- Document issuer: for each category of document, the legal entity responsible for issuing it, e.g., notaries for titles, courts for court decisions, presidential decrees for administrative acts, e.g., land distribution or mining, ministerial decisions for administrative acts, e.g., expropriations, regional/local authority acts, e.g., seashore and beach border line/zone determination, or urban plan extension.

- Property: land parcels, part of a land parcel or part of a building (e.g., condominium unit in Greece, referred to as horizontal deviation), etc., on which rights of beneficiaries described in documents issued by issuers are exercised or to which restrictions/regulations are imposed.

- Protocol number of property right declaration.

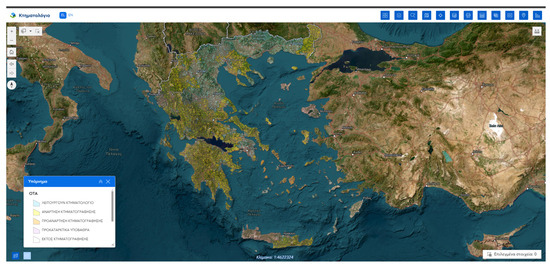

Currently, the status of the HC is either under elaboration of the cadastral survey, or in the operational Cadastre, Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Greece’s Hellenic Cadastre status: operational Cadastre: blue, cadastral survey: i. early stage: orange, ii. mid-stage: yellow, iii. preliminary stage: light purple, Dodecanese Cadastre Urban Cadastre: white (source: Hellenic Cadastre, URL: https://maps.ktimatologio.gr/?locale=el (accessed on 23 March 2025)).

4.3.1. Cadastral Survey for Hellenic Cadastre Creation

Law 2308/1995 foresees the cadastral survey for the creation of the HC. The CS is conducted by private consortia comprising surveyor engineers and surveying companies, registered to official indexes of the Technical Chamber of Greece and the General Secretariat of Public Works, respectively, with proven rights on cadastral surveys and overall cadastral processes. The consortia also include legal professionals, layers, or law firms, undertaken after public procurement and supervised by the Hellenic Cadastre public body. Each consortium is responsible for the operation of the Cadastral Survey Office throughout the entire territory of its responsibility.

The CS is carried out in the 1995 administrative boundaries of municipalities and communes (over 6000 municipalities and communes) and includes the collection of property declarations (from individuals and legal entities), the integrated production of cadastral maps and tables, the official posting of temporary cadastral data for objections, objections’ processing and hearing, and the finalization of cadastral data for operational Cadastre initiation. It is conducted according to specific and obligatory technical specifications, published in the Governmental Gazette. In Table 2, the basic information about the six rounds of CS programs is presented.

Table 2.

HC cadastral survey status and basic information (source: author’s elaboration from Hellenic Cadastre data).

The critical date for the CS is the date of the official posting of temporary cadastral data, the temporary cadastral database official posting; for objections, this is a strictly four-month process (two months for domestic residents and all private entities, and four months for foreign residents and the Greek state). The official posting signifies a fundamental shift from the person-based system of the land registries to the parcel-based system of the Hellenic Cadastre. Subsequent to official posting initiation and prior to CS culmination, a Certificate of Cadastral Property (CCP—PKA in Greek language) must be appended to every legal transaction by titles or any legal action involving property rights before a court. The CCP should also be appended to any legal documents published to the official Governmental Gazette. The CCP encompasses fundamental spatial and descriptive information on the property, including the temporary cadastral parcel unique code, KAEK.

Consequently, the official posting marks the systematization of land management and spatial organization within the framework of the parcel-based HC, signaling the primacy of HC over land registries. The registration of official administrative acts that previously could not be registered in the land registries signifies a huge shift in spatial data management and public body engagement. The registration of expropriations or the delineation of seashore and beach boundaries enables their essential publicity, which is crucial for maintaining transparency and public faith. Even the declaration of adverse possession becomes stricter, especially in the cases of cadastral parcels, or cadastral records identified as “Unknown Owner”, as any declaration on them must be followed by objection, which is obligatorily communicated to the Greek state’s Legal Council of the State. “Unknown Owner” registrations are of public interest, as under the operational Cadastre, they become public property.

After the completion of the four-month period of the official posting, the temporal cadastral database is constantly updated by the incorporation of data derived from new legal documents (drafted after posting initiation), corrections to obvious errors, and not-declared properties at the stage of declaration collection. Concurrently, the resolutions of the committees responsible for the objection examinations are also incorporated into the database and signify the completion of the cadastral survey. CS completion is declared by a ministerial declaratory act, in which the minister declares the completion, but not the correctness of the survey. After the publication of the declaratory act in the official Governmental Gazette, the HC passes to the operational Cadastre stage, while the final CS cadastral records become “initial registrations” of the operational Cadastre.

From Table 2, it is evident that there is a considerable time discrepancy among cadastral programs, and that cadastral surveys have gone through different technical specifications, especially with regards to the spatial cadastral database formation. The early cadastral programs (referred to as “Old Programs”) were characterized by their limited technical specifications for the production of cadastral maps and diagrams. Consequently, there is a substantial number of erroneous entries in the operational Cadastre, particularly spatial corrections, which are often addressed by cadastral judges.

4.3.2. Operational Cadastre

Following the completion of the cadastral survey and the subsequent publication of the Minister’s decision of completion in the official Governmental Gazette, the HC is in the operational stage, known as operational Cadastre. In the operational Cadastre stage, the land registers are suspended and become the official archive of the series of legal documents transcribed or recorded to them of the person-based system. The operational Cadastre is run by cadastral offices (CO) under the exclusive responsibility of the Ministry of Digital Governance (formerly by Ministry for the Environment and Energy).

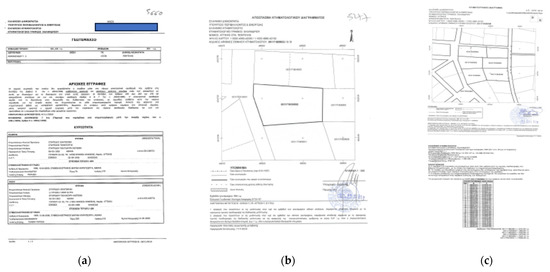

The basic cadastral data of wide use, which are necessary for the spatiοtemporal and descriptive documentation of the cadastral records, properties, and property rights, and that also are used in various cadastral tasks, are the cadastral diagrams and the cadastral sheet and, accessible through the KAEK for each parcel, or the extended KAEK separated or divided ownerships within the same cadastral parcel. The simple cadastral diagram, Figure 7b, includes the parcel’s KAEK and the KAEK of the neighboring parcels, whilst the detailed cadastral diagram also includes the coordinates of their boundaries and access to the 2D spatial cadastral DB of the operational Cadastre, as shown in Figure 7c. The cadastral sheet includes all the relevant descriptive information on the property’s legal status, the original records, those directly linked to the finalization of the CS, and any subsequent information, including any modification or alteration to a cadastral parcel’s or property’s spatial and legal status, as shown Figure 7a.

Figure 7.

Descriptive and spatial documentation of cadastral parcels: (a) cadastral sheet, (b) cadastral diagram, and (c) detailed cadastral diagram (source: Hellenic Cadastre).

Each CO has a specific territorial jurisdiction coinciding with the distinct boundaries of the cadastral administrative units (cadastral boundaries of municipalities and communes in 1995—pre-Kapodistrian), organized in groups by prefecture. If a cadastral parcel falls within the boundaries of two cadastral administrative units, it is registered in both of them, according to its lawful parts, with a note on the cadastral sheet. The CO is responsible for the ensurance of the maintenance, modification, and alteration of spatial and/or descriptive cadastral records and overall cadastral registrations by the submission of a new legal or other relevant document, amending the initial registrations to “subsequent registrations”.

The operational Cadastre is divided into two stages: the “initial registrations” stage and “definitive registrations” stage. During the initial registration stage, the CO is not only responsible for the ensurance of cadastral record maintenance and modification and the overall cadastral registrations supervision, but also for the correction of initial registrations if they are found to be inaccurate, both in their spatial and descriptive aspect. The corrections may be made either by the correction of a manifest error, by court order, or by consent of the owner(s) of the cadastral parcels or rights concerned. In the stage of definitive registrations, the cadastral records are considered to create an irrefutable presumption that cannot be challenged, the “Unknown Owner” registration may become public property, and in the event of a judicial challenge, only monetary compensation is due, as it is considered that a quasi-expropriation procedure has taken place; however, it has not yet been implemented.

5. Transition from Land Registries to Hellenic Cadastre: A Shift in Properties Legal Documentation, Land Administration Policies, and Spatial Data Management

As noted above, the person-based system of land registries is completely replaced by the parcel-based system of the Hellenic Cadastre, with no intermediate stage and without running the two systems in parallel for a smoother transition. Land registries serve only as official archives for the legal documents that they include.

As shown in Table 3, the two systems have significant operational and functional differences.

Table 3.

Hellenic Cadastre (operational stage) and land registries organizational schemes comparison (source: author).

In Table 3, it is evident that the two systems are predicated on disparate foundations. In the context of land registries, the registration of the individual is a pivotal element. Conversely, in the Cadastre and cadastral offices, the registration of the individual is intertwined with the registration and spatial reference of the “cadastral parcel”, over which the individual holds and exercises property rights. The disparate functional and operational designs of the two systems engendered issues not only in the realm of management but also in the substance of the succession between the two systems. These issues were already evident from the first programs, namely the old programs, as there was a shift in property declaration obligation that afterwords included the Greek state (see Table 2).

From old cadastral programs, it was already apparent that the person-based land registries system could not actually safeguard public faith, ensure the security of legitimate transactions, and protect any bona fide property transaction. The fragmentation of the land registries territorial authority, as each one was functioning as an autonomous unit, in combination with the complete absence of any spatial information in transactions with properties, resulted in incomplete records in land registries in terms of spatial and geometrical documentation. The person-based organization of land registries also hindered the effective control of titles transcribed to them, leading to official records with many legal defects and in many cases linked to a property that is not the actual property in the real world.

The cadastral survey for the creation of the Hellenic Cadastre revealed the spatial fragmentation of property spatial documentation, inconsistencies in the descriptive documentation of properties, and a lack of consistency with administrative acts, ranging from the issuance of building permits to the implementation of expropriations and distributions, as well as the adequate protection of public and private property of land registry records and registrations. Also, for the first time, a systematic and comprehensive documentation of the public assets was conducted within the HC, offering a comprehensive view of its holdings.

5.1. Spatial Fragmentation and Spatial Inconsistencies of Land Resgistries Revealed by the Helenic Cadastre Processes

During the cadastral survey stage, the issue of the correct identification and spatial location of land parcels or plots was firstly revealed. The person-based system of land registries, even though it had as a fundamental base the safeguarding of public faith during transactions with bona fide properties, failed due to its person-based structure and organization and the complete lack of any spatial reference, even in cases of administrative acts that included cadastral and topographic maps and diagrams.