1. Introduction

Land administration encompasses the following four main interrelated aspects: land tenure, land valuation, land use, and land development. Secure land tenure is essential to provide landowners with legal security, enable them to defend their rights, and facilitate land transactions [

1,

2,

3]. Secure land tenure can also increase agricultural productivity, enhance urban land values, and improve human welfare [

4]. On the other hand, land valuation plays an important role in determining the economic value of land, which affects investment decisions and financial services [

5]. Methods such as market price comparison and income capitalization can accurately estimate the value of land, thereby supporting national income growth and economic development [

1,

6]. In addition to land ownership and valuation, effective land use is essential to ensure that land resources are used efficiently and sustainably [

7,

8]. Appropriate land use planning regulations can help to address the challenges of rapid urbanization and maintain environmental balance [

8,

9]. The last aspect, land development, is crucial to optimize land use for public benefit, including housing, infrastructure, and commercial areas [

6,

10]. To ensure equitable and sustainable development, coordination among different stakeholders is necessary to improve the efficiency of the land development process. With a structured and integrated approach, land management can maximize the benefits for development and community welfare [

9].

While effective land governance can enhance tenure security, increase land value, optimize land use, and support development, challenges remain, particularly with respect to land conflicts. These conflicts can occur at different levels, from global to national. At the global level, land grabbing in the Global South often triggers conflicts, especially in plantation and agricultural projects. Despite mediation efforts, political and institutional factors often impede resolution [

11]. Land disputes also occur at the regional level. In Northeast Asia, nationalism and public perception influence conflicts such as the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute between Japan and China and the Takeshima/Dokdo dispute between Japan and South Korea [

12,

13,

14]. In Southeast Asia, the South China Sea is a focal point of conflict, with many countries interested in maritime boundaries and resource exploitation, with China playing a dominant role. In addition, border disputes such as Ambalat and Sipadan–Ligitan between Indonesia and Malaysia demonstrate the complexity of international arbitration and the importance of diplomacy in achieving a peaceful resolution [

15,

16,

17]. At the domestic level, Indonesia still faces ongoing conflicts due to overlapping claims and governance issues. Clear examples include the dispute over the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) initiative in West Kalimantan [

18], the protracted land tenure conflict in Rempek village, Lombok [

19], and the economic, environmental, and indigenous rights issues surrounding PT Freeport Indonesia [

20].

In general, land disputes can arise from technical and legal factors. From a technical perspective, inaccurate or incomplete land data are often the main cause of disputes, leading to uncertainty about land boundaries and ownership [

21,

22]. In addition, the existence of conflicting land titles creates legal uncertainty and complicates the settlement process, as multiple parties may claim rights to the same land [

23]. Another contributing factor is the inefficiency of the land administration and titling system, which fails to provide clear and reliable documentation of land ownership [

22,

24]. From a legal perspective, dualism in agrarian law is a major cause of land disputes, as different interpretations and applications of the legal framework can lead to overlapping claims to the same land [

21]. Legal ambiguity and the lack of a clear regulatory framework exacerbate conflicts and make dispute resolution difficult [

23,

25]. In addition, illegal activities by the land mafia, such as fraudulent land registration, complicate the legal process and undermine public confidence in the legal system [

21,

24].

To address the challenges in the land sector, it is critical to implement a reliable cadastral system to resolve land disputes and improve the efficiency of land administration. This system should integrate spatial and legal information for each parcel of land, and its success depends on the accuracy, reliability, and timely updating of data [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. One of the main functions of a cadastre is the accurate determination and recording of land boundaries. Unclear boundaries, especially in areas of high land pressure, often lead to conflicts. To avoid overlapping ownership, the system needs to be developed in a sustainable manner. As the cadastral system evolves, its legal and administrative aspects will be further strengthened by providing official records that are accessible to all stakeholders, thus helping to reduce uncertainty and facilitate dispute resolution [

31,

32,

33]. In addition, the implementation of a cadastral system will also contribute to spatial planning, land management, and fiscal optimization [

22,

23,

24,

25,

27,

34].

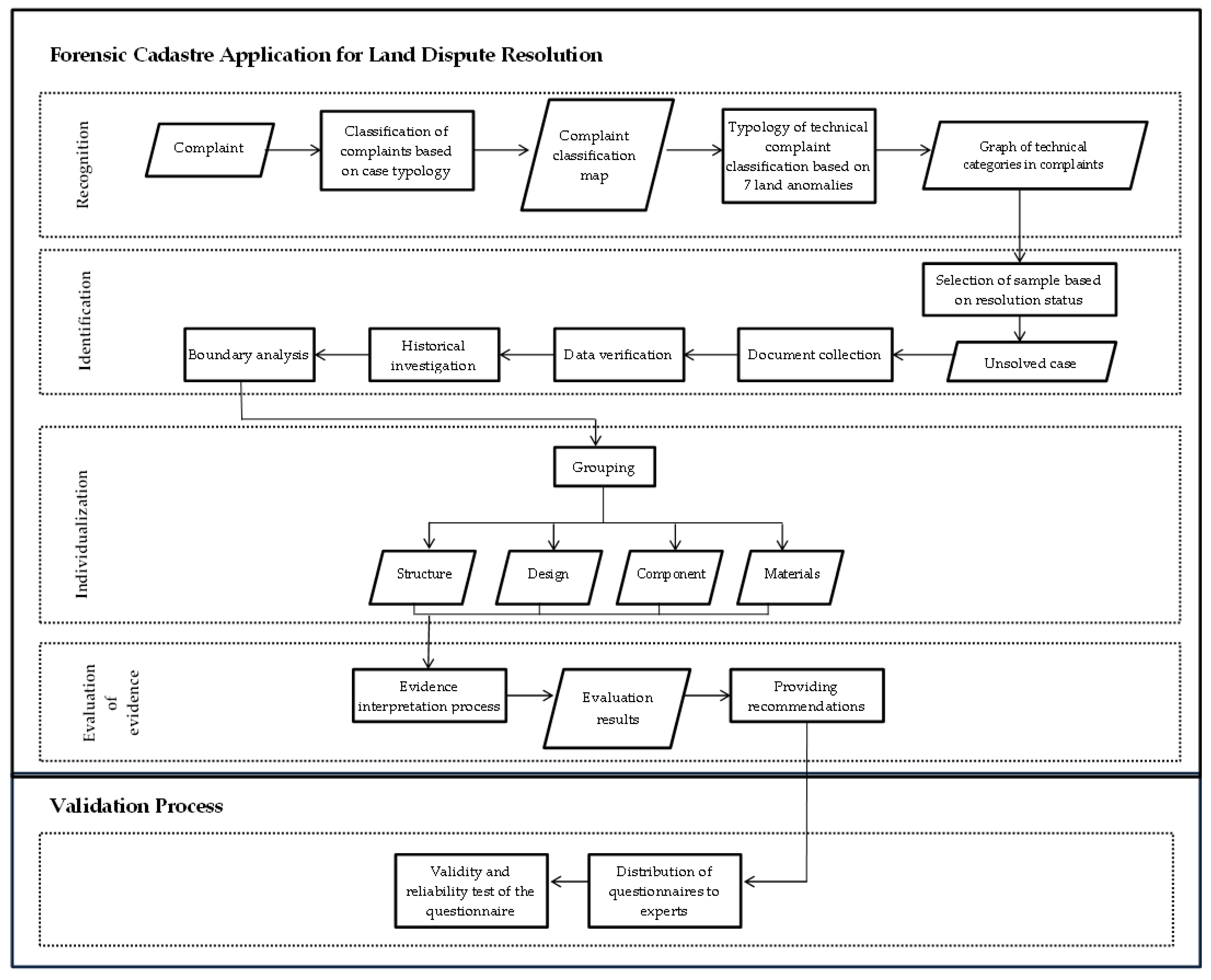

One approach that can improve the reliability and effectiveness of a cadastral system in resolving land disputes is the application of forensic science. This discipline combines scientific methods to reconstruct events based on physical evidence through processes of investigation, analysis, and evaluation. Forensic science also considers the interaction between people, materials, and other objects [

35,

36]. When cadastral information is used in a legal context or for dispute resolution, this information becomes part of a forensic practice known as forensic cadastre. This approach aims to ensure the accurate identification of land boundaries, provide evidence that is acceptable in court, and analyze cases such as land encroachment or illegal land use [

37,

38,

39].

In land administration, forensic cadastre plays an important role in resolving disputes over ownership status, unauthorized construction, and claims of co-ownership. In addition to facilitating a more objective resolution process, forensic cadastre also contributes to increased transparency in land administration [

39,

40].

Although it holds significant promise for tackling land-related challenges, the execution of forensic cadastre continues to encounter numerous obstacles, especially the absence of a uniform methodology [

40,

41,

42]. Earlier investigations revealed that the use of forensic cadastre was confined to field identification and data verification, lacking a thorough framework for assessing evidence [

40,

41]. Meanwhile, other research has provided a wide range of methods, such as document reviews, field inspections, and the creation of conflict resolution suggestions [

39]. However, these processes do not fully conform to the core tenets of forensic science, which are identification, recognition, individualization, and interpretation. Furthermore, to ensure procedural accuracy and the importance of recommended actions, each stage of the forensic cadastre process must be validated by experts in the cadastral field.

This study addresses existing gaps by proposing a novel methodology for the application of forensic cadastre. It emphasizes the integration of the foundational principles of forensic science and the inclusion of expert validation throughout each phase of the process. This method aims to improve the efficiency, impartiality, and clarity of land dispute resolution, offering a practical alternative for cases that remain unresolved through traditional approaches like mediation.

3. Result and Analysis

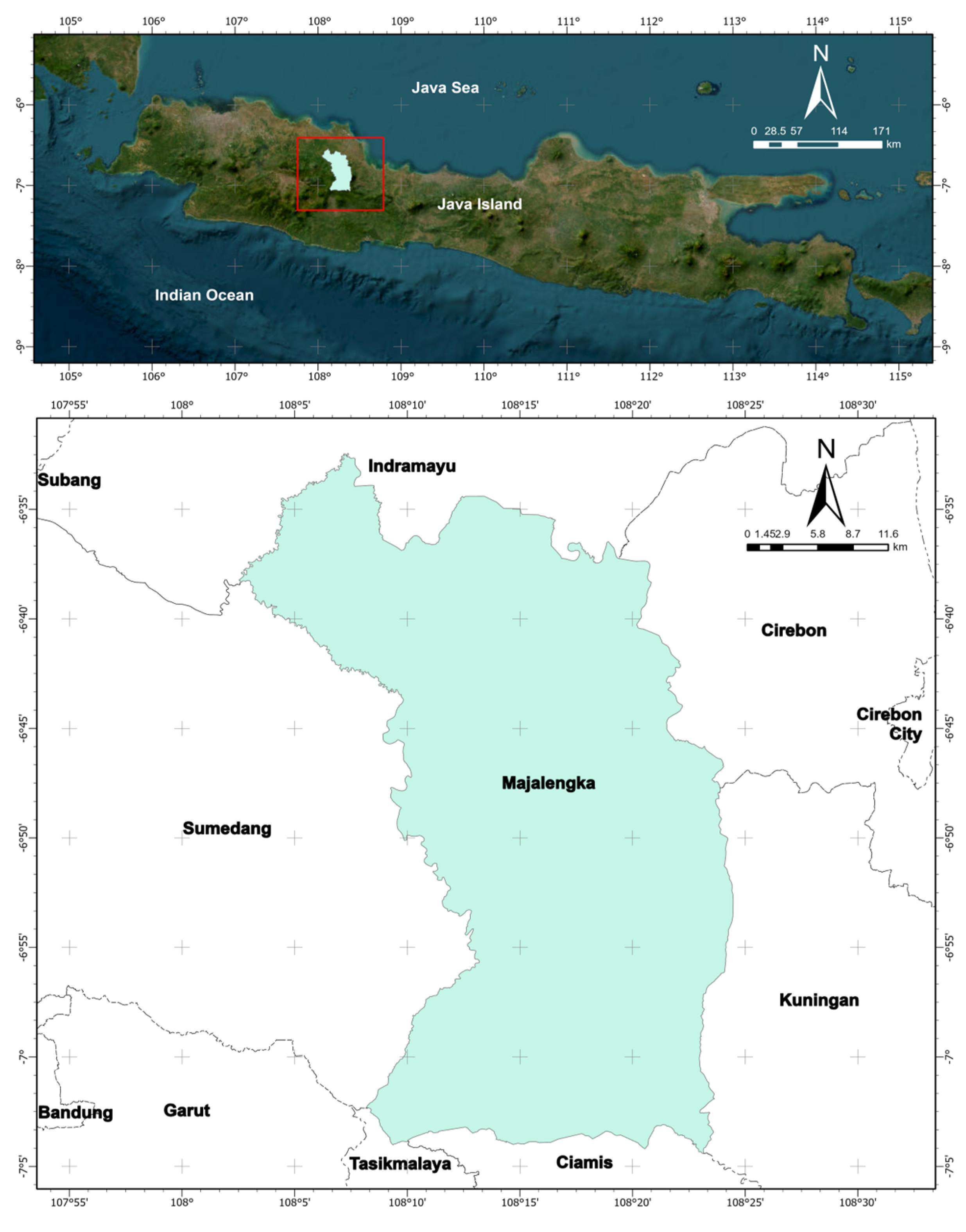

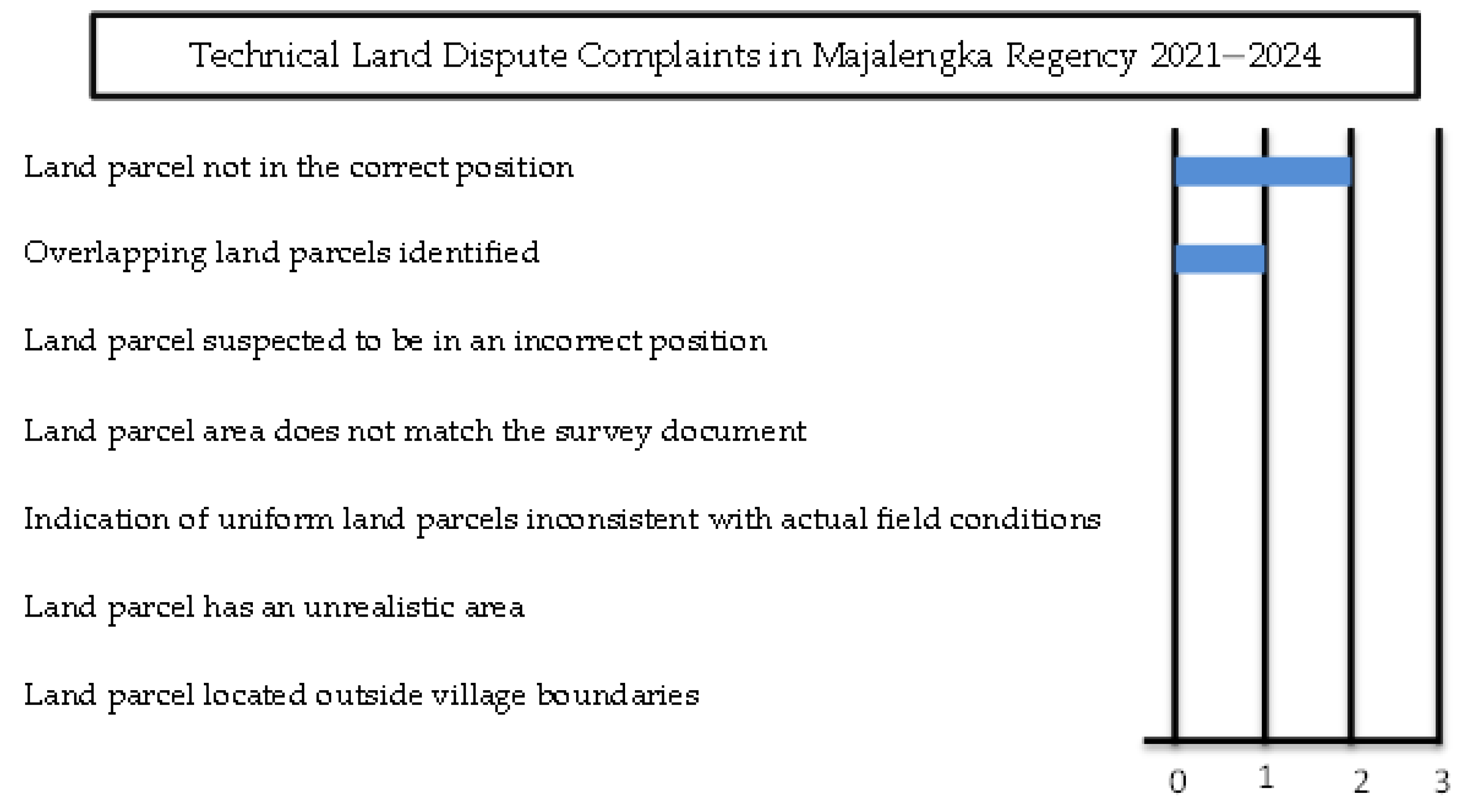

3.1. Complaint Distribution Map and Graph of Technical Land Dispute Complaints

Based on the collection of data regarding land disputes in Majalengka from 2021 to 2024, a map displaying the distribution of complaints is created, as shown in

Figure 3. This map illustrates the location and frequency of complaints, making it easier to identify areas with a high concentration of land disputes. Of all the complaints received, approximately 84% fall into the category of legal complaints, although this aspect is not the main focus of this study. In addition, technical complaints related to the physical and spatial aspects of land also arise, including issues of boundary determination and land plot location, as well as cases of overlapping land plots.

Based on the typology of the seven land anomalies, Boundary/Parcel Location Determination is classified as “Land parcel, not in the correct position”, with one reported case in Buntu Village, Ligung District. Meanwhile, Overlapping Land Parcels fall under the category of “Overlapping land parcels identified”, with two reported cases in Indangkerta Village, Maja District, and Karyamukti Village, Panyingkiran District. The distribution of these technical complaints can be further observed in the graph presented in

Figure 4.

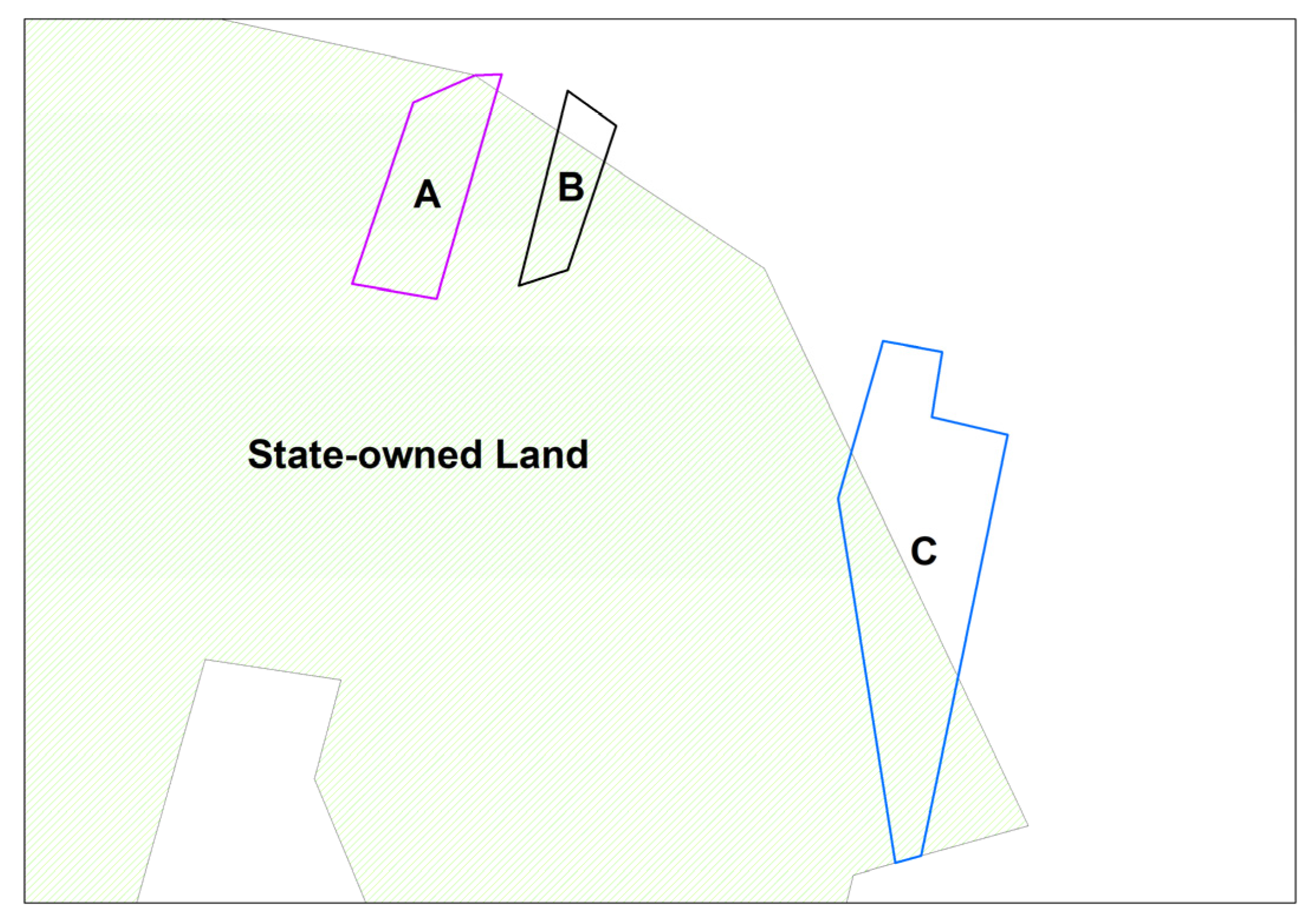

3.2. Unresolved Case Selected

Out of three technical land dispute complaints, two cases were successfully resolved through mediation in 2021 and 2023. Both cases had similar issues, namely, the applicants claimed that the boundary of the respondent’s land violated their land boundary, based on the land plot map accessed through the Bumi ATR/BPN website (

https://bhumi.atrbpn.go.id/ accessed on 10 March 2021). This dispute was relatively easy to resolve because it only involved two parties (the applicant and the respondent) and did not involve state-owned land. The issue was caused by a graphic mapping error that did not affect the area of land owned by the parties or the neighboring lands. Through the mediation process, it was agreed that the land boundaries would be determined according to each party’s certificate, without any change in area, only positional adjustments. With this agreement, both parties felt that they were not at a disadvantage. Illustrations of the land boundary conditions before and after mediation are shown in

Figure 5.

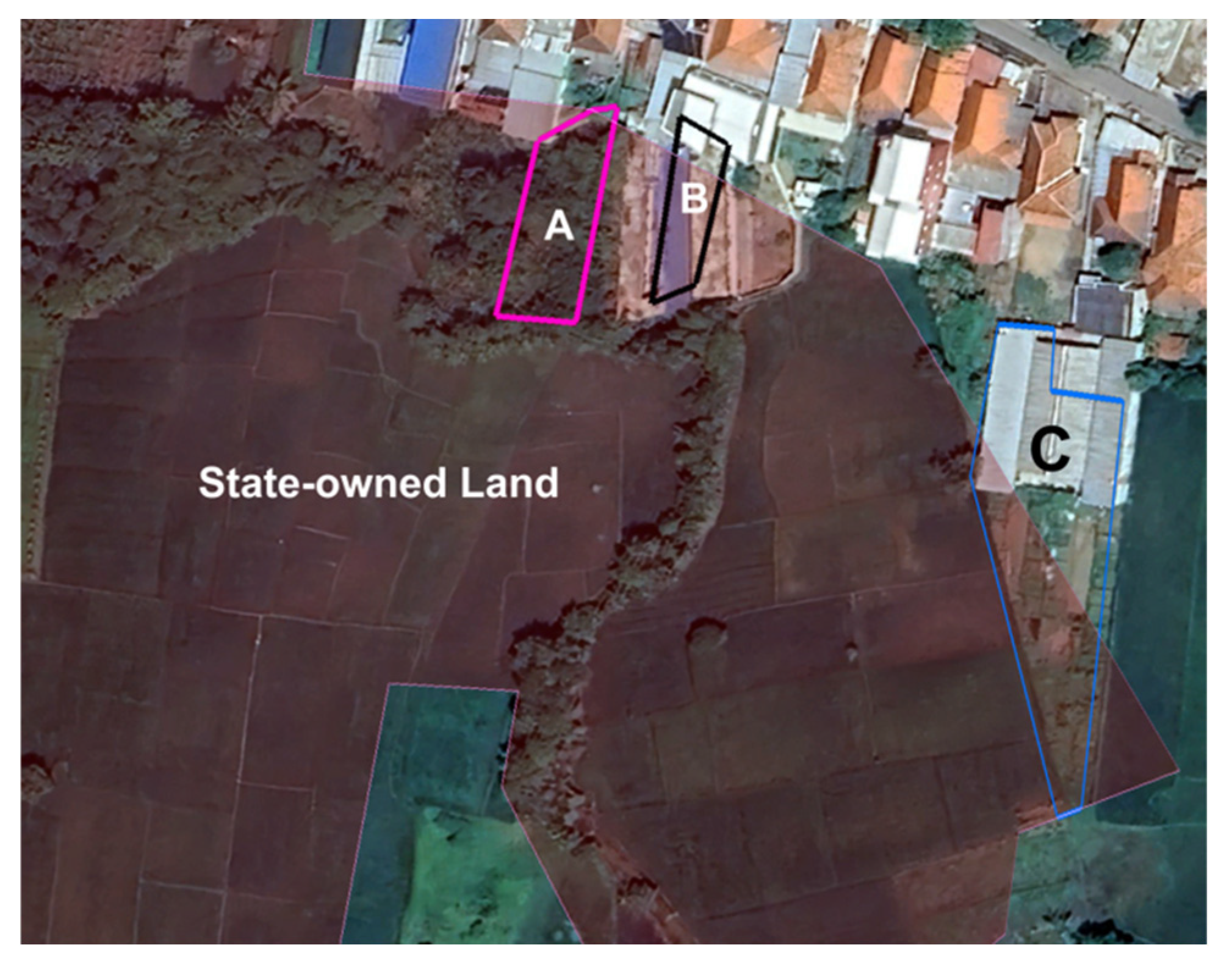

Meanwhile, the unresolved case involved state-owned land and three private lands. This case was raised in 2023 and was caused by overlapping land parcels. As shown in

Figure 6, land plots A, B, and C overlap, affecting nearly half of their total area. This case cannot be resolved through mediation, because if one party wins, the other party will suffer significant losses. Although three stages of mediation efforts have been carried out, no solution acceptable to both parties has been achieved. Therefore, this case was chosen as the focus of this study.

3.3. Results of Document Collection and Verification

After the case study was selected, a document collection and verification process was carried out.

Table 3 lists the details of the documents collected and verified for each involved party.

The verification results show that Owner C only has two out of the nine collected documents. This indicates that Owner C has incomplete documentation and records, as the other parties have all seven documents.

3.4. Result of Historical Investigation and Boundary Analysis

The collected and verified documents were then used for a historical investigation to trace land ownership, track changes in land status over time, and prevent encroachment or document forgery. The results of this historical investigation are presented in

Table 4, with a detailed description in

Table 5.

Description: Girik, Letter C, and Petok D were documents used as proof of land tax payments in the past, but do not serve as legal proof of ownership based on the Supreme Court of the Republic of Indonesia Decision No. 34/K/Sip/1960, dated 19 February 1960 [

77].

Among the four components of this historical investigation, the most crucial is proof of ownership, as this serves as the legal basis for the issuance of ownership rights. Proof of ownership documentation may take various forms, as outlined in the categories presented in

Table 4. Based on this consideration, the following irregularity was identified: Owner A provided proof of ownership and the transfer of rights only orally, which is legally weak and not recognized as valid evidence [

78]. In contrast, the owner of Parcel C failed to submit any supporting documents, including proof of ownership, which is the most fundamental requirement in land rights verification.

The following process involved boundary analysis. This step is crucial, especially since overlapping land parcels caused the case. The results of each component used for the boundary analysis are presented in

Table 6, with a visualization of the overlapping areas based on satellite imagery shown in

Figure 7.

Each document listed in

Table 6 plays an equally important role in boundary analysis, as boundary determination requires not only quantitative data, but also visual evidence and the involvement of authorized parties to define and verify boundaries. Based on the evidence review, the boundary accuracy of Owner C’s land cannot be confirmed and is considered weak due to the absence of complete supporting documents.

3.5. Structure, Design, Components, and Materials Analysis

The next step is to identify and analyze potential errors in structure, design, components, and materials based on the evidence collected.

Regarding structure, which includes the parties involved in land certificate issuance, the analysis of Parcels A, B, and C refers to the Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency Regulation No. 6 of 2018 on Systematic Complete Land Registration. Meanwhile, the structural analysis of state-owned land refers to the Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency Regulation No. 18 of 2021 on Procedures for Determining Management Rights and Land Rights [

66,

67].

The parties involved in issuing certificates for disputed land complied with the established standards, with details presented in

Table 7 and

Table 8.

After analyzing the structural aspects of the land certificate issuance process, the next step is to examine the design aspects related to the certificate issuance mechanism. Since all the land certificates in this case study were issued before the regulations on electronic certificates under Law No. 1 of 2021 came into effect, the process followed the implementation stages outlined in Government Regulation No. 24 of 1997, as shown in

Table 9 [

68].

Based on

Table 9, the issuance processes for the Owner A, Owner B, Owner C, and state-owned land certificates complied with the requirements set forth in the applicable regulations. For individual land rights holders, in this case, a certificate can be issued if no objections are raised within one month. Meanwhile, for state-owned land, the issuance process does not require a public announcement but is carried out through a decree issued by the Head of the Land Office or the Regional Office. During the designated one-month objection period, no objections or disputes were raised regarding the Owner A, Owner B, Owner C, or state-owned land certificates.

After reviewing the design aspects of the land certificate issuance mechanism, the next step is to analyze the components involved in resolving the land issues between Owner A, Owner B, Owner C, and the state-owned land. These components include human resources, decision makers from relevant organizations, the technology used, and the data collection process in the field, as presented in

Table 10.

As the final stage in the individualization process, the material aspect becomes the focus of analysis in resolving the land issues in this case study. All the examined land parcels use analog certificates and have fulfilled the certificate components, including the land register, measurement letter, land parcel map, and survey drawing. However, one parcel, namely Parcel C, lacks the warkah document, even though this document serves as the primary basis for issuing land certificates.

Among the four aspects analyzed during the individualization stage, structure and design are the most critical, as they play key roles in identifying the relevant parties and determining the procedural mechanisms for land certificate issuance. The land certificate itself serves as the primary legal instrument that establishes the legitimacy of land ownership.

3.6. Interpretation Results in Evaluation

After completing the analysis in the individualization stage, the next step is to proceed to the evaluation stage. In this phase, the evidence gathered during the identification process is analyzed in greater depth to examine each aspect of the individualization process. Through this evaluation, the evidence is further scrutinized to identify the key factors contributing to the underlying issues, with the mapping of potential failures presented in

Table 11.

Based on

Table 11, it was identified that the primary sources of issues or non-compliance with the applicable regulations stemmed from Owner C, followed by Owner A. Meanwhile, the review of Owner B’s ownership and state-owned land showed no issues. Therefore, the following recommendations are proposed:

The certificates of Owner A and Owner C should be reassessed, and if significant discrepancies are found, the certificates may be canceled. If Owners A and C cannot prove the validity of their land ownership, their claims will be considered void, and the land overlapping with state-owned land should be transferred to state ownership.

Owner B and the authorities managing the state-owned land should clarify the land boundaries to ensure legal certainty regarding land ownership. Since the documents held by both parties have equal legal weight, the policies that can be implemented include discussions for land area division. If the state refuses to divide the land, the state should consider purchasing the land from Owner B that overlaps with the state-owned land.

As an illustration, the visualization of the recommendations for each land parcel can be seen in

Figure 8.

The application of forensic cadastre enables a comprehensive examination of the evidence presented by each disputing party, thereby facilitating objective and well-informed recommendations. This methodological approach is expected to be applicable in other land dispute cases to support fair, transparent, and effective resolution processes.

3.7. Validations Result

The validation process of this study involved 43 respondents consisting of practitioners in the field of cadastre and decision makers. The main objective was to ensure that each stage based on forensic science and engineering can be applied in the cadastral forensic process. Validation was conducted through Google Forms with a rating scale from one to four, where a score of one indicated incompatibility and a score of four reflected a high level of suitability. Thus, this validation aimed to ensure that the stages of forensic science and forensic engineering are relevant in the context of cadastre to address land dispute issues. The questions posed are as follows:

The suitability of complaint classification based on case typology for effectively grouping complaints (Q1).

The accuracy of technical complaint typology based on the seven land anomalies in identifying technical issues (Q2).

The appropriateness of sample selection based on resolution status for determining cases for further analysis (Q3).

The relevance of document collection as a step in identifying complaint cases (Q4).

The necessity of data verification to ensure the accuracy of information in resolving complaints (Q5).

The role of historical investigation in gaining a deeper understanding of complaint contexts (Q6).

The suitability of boundary analysis in determining the legal aspects of complaint cases (Q7).

The accuracy of the individualization process, which categorizes evidence analysis into four categories (structure, design, components, and materials) to identify errors in unresolved cases (Q8).

Forensic cadastre procedures are necessary even when previous steps have followed standard protocols (Q9).

The accuracy of the research validation for applying forensic cadastre in land dispute resolution (Q10).

The detailed responses from the experts are presented in

Table A1. The validity and reliability tests of the questionnaire used for the validation process were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 Desktop. The results of the validity test showed that 80% of the total correlations had a

p-value below 0.05, indicating a good internal validity and the ability of the items to consistently measure the intended construct. Although 20% of those correlations were invalid, the proportion that was valid was much higher, indicating that this questionnaire still had a high level of reliability in evaluating each stage of cadastral forensics to resolve land disputes. The detected invalidity may have been caused by weak relationships between some of the questioned variables, differences in respondents’ interpretations, or external factors influencing the answers. This phenomenon is common in questionnaires, especially those involving complex variables.

In addition to validity, the reliability of the questionnaire was also tested, with a Cronbach’s Alpha result of 0.855 for 10 items. A value above 0.8 indicates a high internal consistency, so the instrument can be considered as reliable for assessing the forensic cadastre methodology.