3.2. Territory and Landscape of Villa Giusti-Puttini Through Historical Maps

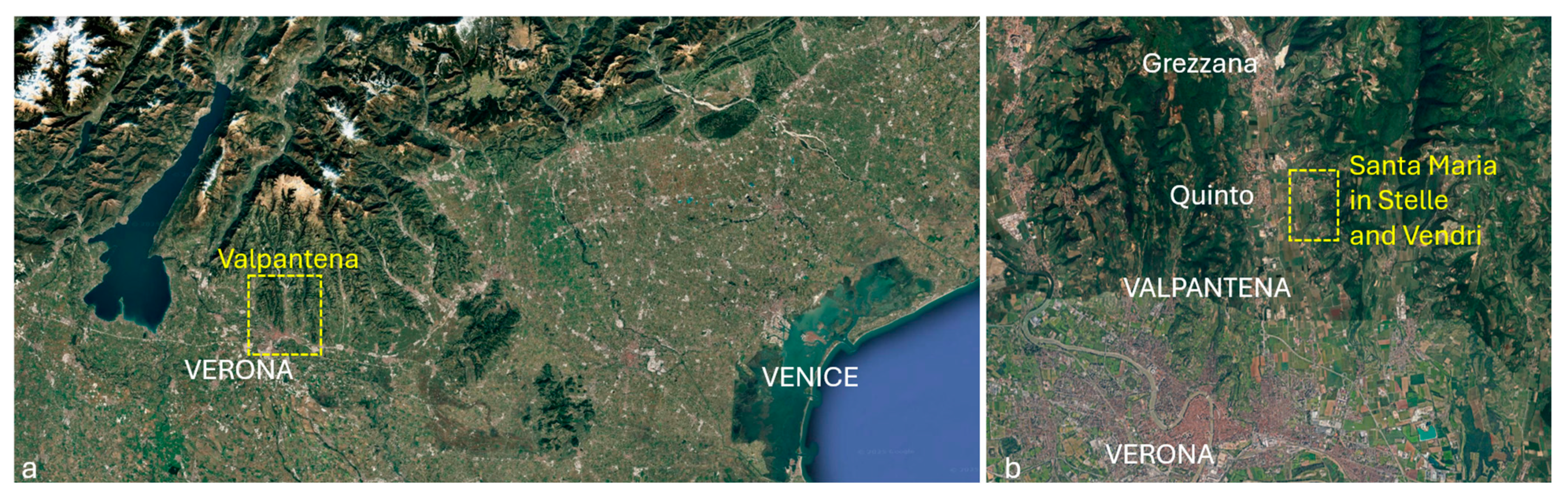

The first known representation of Villa Giusti-Puttini to date is probably the one drawn in the village of Santa Maria in Stelle in the Carta dell’Almagià (

Figure 4a), a map dated around 1460 [

33]. It is a sketchy representation that, despite its inaccuracy, gives us relevant information about the villa and the landscape. One must bear in mind that, especially in the case of the residential buildings, it is a conventional representation that probably mainly represents the size and importance of the settlement [

33]. In the detail of the village of Santa Maria in Stelle (

Figure 4b), a number of elements can be clearly distinguished: the church at the end of the main road, the residential buildings flanking the road; a building that appears to be covered with a dome that could symbolise the hypogeum or a chapel to the left of the church and to the right of the main road, a large complex with a pigeon tower and two courtyards.

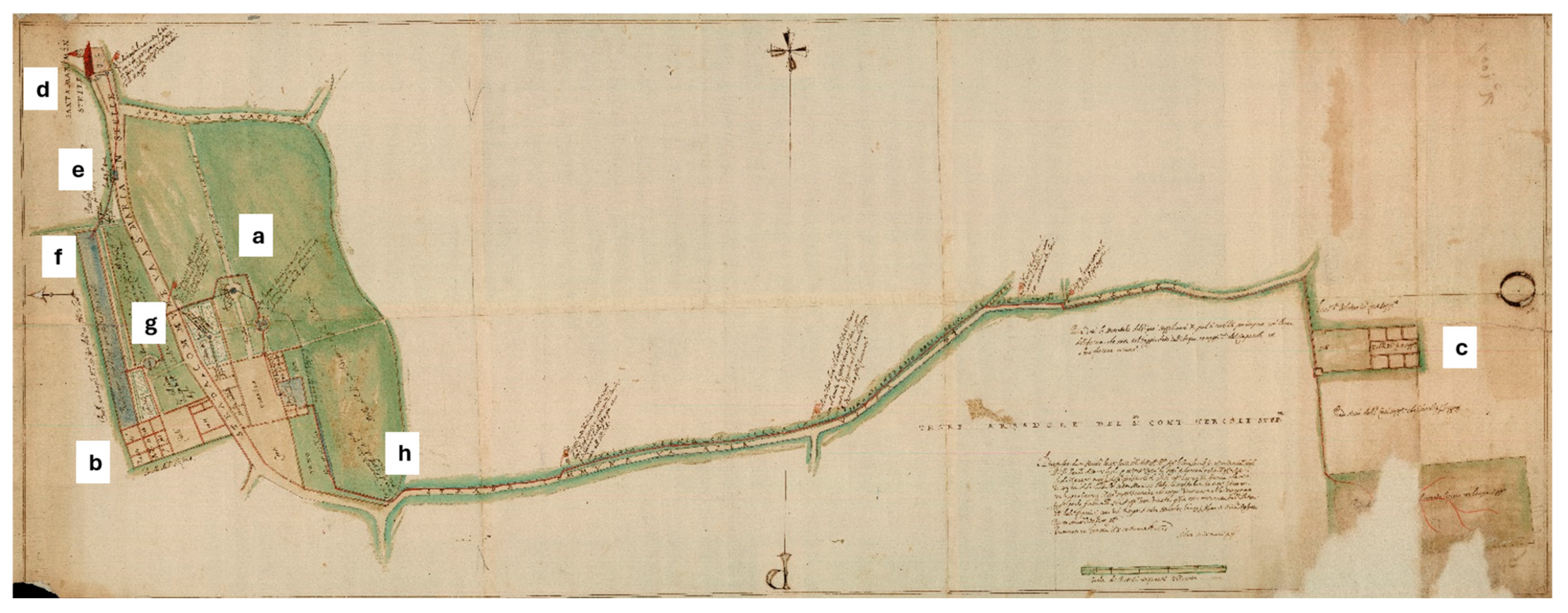

The first map in which a direct reference to the villa appears dates back to 1598 (A.S.VR. Campagna Archive—B.13, no. 155), even though the drawing centres on the Vendri property, currently Villa Giusti-Melloni. Much more detail is provided by Ercole Peretti’s drawing of 1625 (A.S.VE. Beni Inculti—Verona, rot. 74, deck 64, dis. 5) which refers to the property inherited by Vinciguerra San Bonifacio in 1622. The drawing (

Figure 5), representing Villa Giusti-Puttini (a), the palace of Zenovello (b) in Santa Maria in Stelle and Villa Giusti-Melloni in Vendri (c), was made to define the correct management of water between the three properties. The complaint lodged by Count Ercole Giusti, owner of the villa in Vendri (c), concerned the water that, coming from under the church of Santa Maria delle Stelle (d), was to irrigate his property passing through the properties both of Count Francesco and his son Giusti (b-f-g) and Count Vinciguerra and his son Sanbonifacio (a). The path of water through the three properties is quite complex. It starts from under the church, passes through the wash house of Santa Maria in Stelle (e), enters the fishpond of Francesco Giusti (f), passes through his garden, the spring and the grove of plane trees (g) and then passes under the road and enters the property of Vinciguerra di Sambonifacio (a) to irrigate the garden and the

brolo, bringing water to the fountain. Then it divides between the canalisation that irrigated the

brolo directly and the one that entered a first fishpond and a second fishpond to then join the moat behind the manor house and finally exit in the south-eastern corner from the property (h) to skirt the road towards Vendri and the property of Ercole Giusti (c).

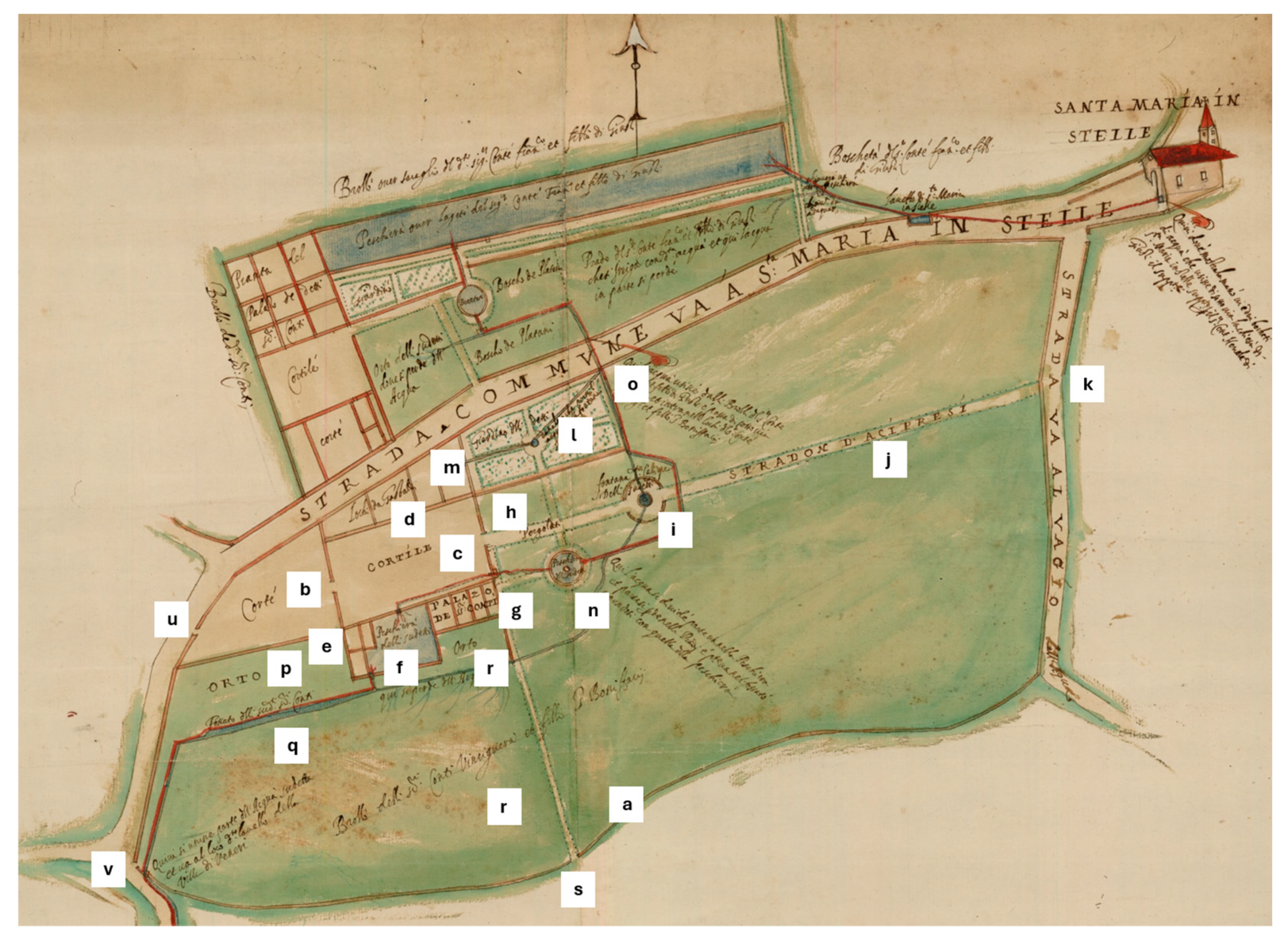

The detail with which the map was drawn allows us to know the essential parts and elements of the properties that the water crossed. The drawing (

Figure 6) shows the boundary wall and the walls of the buildings in the plan, as well as details of all the garden elements, the vegetable gardens, the

brolo, etc. It is a drawing made to scale in “pertiche veronesi” (2.057489 m) and in fact, if one compares the proportions of the map elements with those of the buildings that are still present, it has a good degree of reliability. In this sense, it seems sensible to take it into account as a faithful representation of the villa in 1625.

The villa is bounded by a boundary wall (a) separating it from the surrounding fields and consists of the following elements from left to right: the first courtyard (b) accessed from the road through an opening on the west side; the second courtyard (c) flanked, to the west and east, by two boundary walls both with a central opening, to the north, by constructions called “Lochi da Gastaldi” (foreman building) (d), to the south, by constructions without denomination (e), the fishpond (f) and the manor of the counts (g); and to the east of the courtyard, an opening gives access to a path called “pergola” (h) leading to the fountain where the name of the muse of the poem “Caliope” seems to be read (i). The path then continues in the “stradone d’acipressi” (cypress avenue) (j) to an opening in the “strada va al vagio dell’acqua” (k). In the northern part of the path named “pergola” (h), there is a garden (l) with a central fountain or basin, four large flowerbeds, a gutter named “underground” and a connection of the basin or fountain to the building named “Lochi da Gastaldi” (d) where there is a water slope (m) on the eastern wall towards the garden. To the south of the path is a circular fishpond (n) that functions as a circulation element for the water entering the property from the north (o) and follows towards the large rectangular fishpond (f). In the southern part of the courtyard and manor house are two orchards (p) separated by a moat (q) from the brolo (r). This map also shows the access paths to the villa on the south (s), east (k) and west (u) sides and a possible small access in the south-east corner (v). In this drawing, the water path is very detailed and has a main route which enters the property from the municipal road to the north (o), circles around the fountain (i), enters the circular fishpond (n), enters the courtyard (c), the rectangular fishpond (f) and the moat (q) and exits the property in the south-western corner and then continues to the hamlet of Vendri. Several paths branch off from this main route, which serve to irrigate and beautify the property: the garden (l), the fountain (i), and the brolo (r).

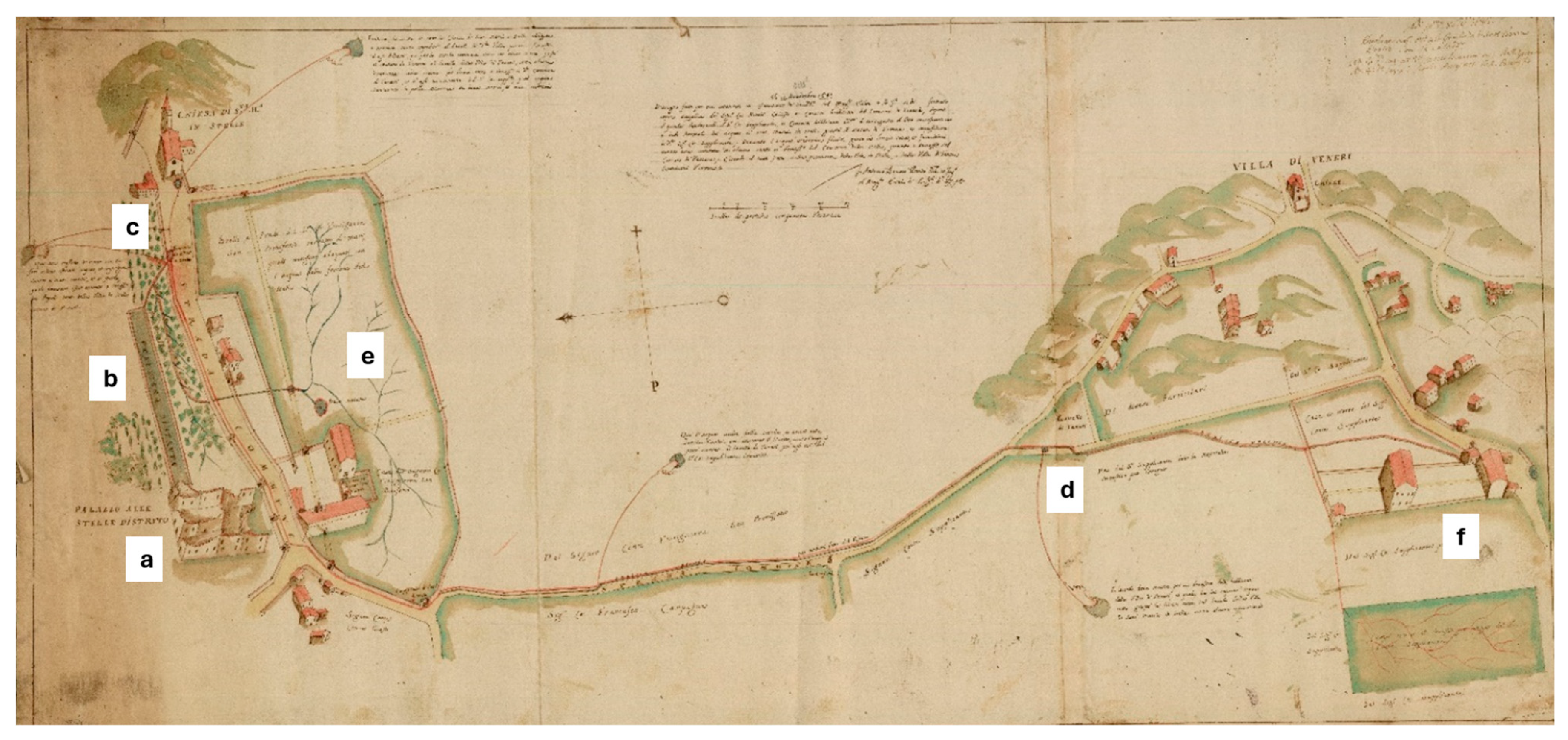

This planimetric drawing was followed by several axonometric drawings depicting the complex, which give the measure of the transformations the villa has undergone over more than two centuries. In the map drawn by Antonio Benoni in 1683 (A.S.VE. Beni Inculti—Verona, rot. 102, deck 86, dis. 5) (

Figure 7) some significant differences from the map of 1625 (

Figure 5) appear. Firstly, this document records the destruction of the Palazzo di Zenovello in 1675 (a) and the large fishpond annexed to the palace (b). It is possible that the destruction of the palace led to a change in the circulation of water. In the map of 1625, the water that came out of the hypogeum spring under the church of Santa Maria in Stelle apparently passed through the public wash house to enter the garden of the Zenovello palace and finally into the villa of Vinciguerra Sanbonifacio. On the contrary, in the map of 1683 (

Figure 7) there appears to be a direct circulation between the public wash house of Santa Maria in Stelle (c) and that of Vendri (d). The diatribe consists in the claim of Count Nicolò Giusti, owner of the villa in Vendri (f), to ensure that the water flowing from the spring of Santa Maria in Stelle reaches Vendri without intermediate interruptions.

The detail of the present Villa Giusti-Puttini (

Figure 8) shows us some important differences from the layout mapped in the 1625 drawing (

Figure 6). Firstly, a portion of the land in the northern area of the property appears to be cut out and surrounded by a new boundary wall and the construction of three new buildings, possibly residential or rustic (a). Secondly, where in 1625 there was only a dividing wall between the courtyard and the access courtyard, in 1683, a transversal building is drawn that occupies the entire size of the courtyard and, with a subway, provides access to the manor courtyard (b). Thirdly, with respect to the elements of the park, the garden with the flowerbeds disappears, being occupied by the construction of the new buildings to the north (a); the enclosure of the access court towards the

brolo disappears (c); the large quadrangular fishpond that was located to the west of the manor appears as “ruined fishpond now orchard” (d); the circular fishpond to the east of the manor appears as “dry hole” (e); and the water canals change their layout—those that fed the garden and the western fishpond disappearing, and those that fed the orchard and the

brolo becoming much simpler. Although the representation of the buildings may not be correct, given that the purpose of the map was water management, some details can be detected that may have some veracity: the quadrangular fishpond retains a boundary wall (d), adjacent to the fishpond appears a small tower that could be the present pigeon tower (f), and the manor appears to have access from the west side (g). Access to the property from the main road to the west (h) and from the road behind to the east (i) is preserved.

The following graphic document dates back to 1735 and is the drawing by Francesco Cornale, an engineer of the city of Verona and public surveyor (A.S.VR, Campagna Archive—B. 13, no. 154) with the aim of defining the boundaries of the properties of Count Giovan Battista Giusti and his nephew Cesare Giusti (

Figure 9). The fact that the purpose of the map is different from the previous ones is evident in the area drawn as well as in the lack of attention to water courses and canals. The map clearly identifies the different properties: on the left side of the map, north of the municipal road, the “

Brolo of the destroyed palace of Count Zenovel Giusti, with legacy in 1503” (a); and south of the same road, the “

Brolo and manor of Count Giusto Giusti then Giovanni Francesco Giusti, with legacy in 1560” (b). To the west of the church (c), drawn with some accuracy and with access to the hypogeum located in front of it, were two buildings: the first is a “small house now inhabited by the agent of the Counts Giusti” (d); and the second is called “Casa dei Casali”, inhabited by the Counts Giusti after the destruction of the Palazzo and improved (e). These two properties have small plots of land (f and g).

In the specific detail of the present Villa Giusti-Puttini in the 1735 map (

Figure 10), some elements of interest for the interpretation of the villa appear: the first courtyard (a); the second courtyard (b) with an orchard enclosed by walls, to the south, the pigeon tower, an orchard enclosed by a wall at the site of the ancient fishpond (c) and the count manor (d), to the east, a boundary wall with a gate that leads to a pergola (e) covering the paths in the immediate vicinity of the manor house and leading to a third orchard enclosed by a perimeter wall (f) and to what could be the fishpond and fountain; and beyond the pergola, a wide

brolo opens up (g). The nucleus of buildings built on the communal road seems to be consolidated with more buildings than on the previous map (h). To the south of the manor, an element appears that did not exist or had not been drawn on the maps until this time: a wall that runs along the path (i) to an access with pillars and spires (j), which seems to give more importance to this access than to the access from the municipal road and the western courtyard. The portal drawn in the south access (j) is clearly the one we find today in the west access, so we could have two explanations: either the portal was in the south access and after 1735 it was moved to the west access, or the map draftsman confused one access with the other. If one consults the previous maps (

Figure 6 and

Figure 8), it will appear that the western access to the courtyard was through an open doorway in the boundary wall, so that the rusticated portal may indeed have been inserted later in the present location. If this hypothesis were true, the southern access to the villa should have been more important than the other accesses at least in the 18th century. To the south of the manor, there seems to be a wall parallel to the manor house enclosing a garden (k). With respect to the accesses to the property, apart from the access from the south with the gate with pillars (j) and the access from the west through the courtyard (a), from the drawing, it would seem that the eastern access had been closed (l) while a new access from the communal road had opened in the north-eastern part of the

brolo (m). Again, it is difficult to know whether this is an error or confusion on the part of the cartographer or a previous access opened in the north wall later disappeared. In the south-western corner, what in earlier maps might have looked like an access appears instead to be a niche (n) and may correspond to the niche that houses St. Anthony that was later to be moved to build the buildings on this spot.

The following drawing, by Giovan Battista Pallesina in 1798 (A.S.VR., Campagna Archive—B. 32, no. 337), once again related to the dispute over water distribution, is possibly much less accurate in terms of architecture and the rest of the landscape elements (

Figure 11). The property of the present-day Villa Giusti-Puttini is defined as the “

brolo of Count Maffei”. The drawing of the two courtyards and the villa’s manor is evidently approximate, while the circulation of water entering the property passing under the road seems to have remained intact, as has its circulation through the

brolo to the exit from the property through the south-west corner. The circular fishpond and fountain are portrayed, as is the access to the property from the secondary road to the east of the villa.

From the 19th century, the property is documented in the Napoleonic cadastre of 1817 as the property of Uguccione Giusti, and in the Austrian cadastre from 1844 to 1894 as the “holiday home” of the Verdari family (1844–1894). From 1970 to the present day, the estate is owned by the Puttini family. The map of the Napoleonic Cadastre (

Figure 12) shows the two successive courtyards with the buildings surrounding them described as the “foreman’s house with courtyard and oven”, the manor identified as “house of own use”, the pastures, the meadow avenue, the fish market, the vegetable gardens and the meadow with orchards.

In the map of the Austrian cadastre (1844–1890) (

Figure 13), the first and second courtyards with the rustic buildings are both defined as “farmhouse”, the manor as “holiday home” and the orchard, the ploughed fields and the meadow are shown. In this map, there are no references to the fishpond, path or pergola. In both the Napoleonic and the Austrian cadastres, a double line dividing the

brolo is maintained, which corresponds to a canalisation through which water circulated and which appears to be exactly the one on the 1625 map.

In the Italian cadastre (1896) the layout of the canal and the access to the

brolo from the south are maintained. In the following updates to this cadastre, the major transformation is linked to the construction of the front of the houses located on the communal road between 1950 and 1970. A new property with a building in the north-eastern corner of what was the

brolo of the villa also appears at the same time. In the 1971 EIRA map, in the same north-eastern corner appears the construction of two buildings and a plot in the lower part, cutting off a large part of its eastern edge from the property and its exit onto the corresponding road. Finally, it is in the following EIRA map of 1997 when the situation is definitively consolidated to the present day with the complete separation of the entire eastern part of the

brolo at the current football pitch. This is the consolidated arrangement that we still find in the present map (

Figure 14).

3.3. Historical Data for the Reconstruction of the Villa

The first clear description of the complex is found in the deed of contribution of the dowry of Zilia Campagna, widow of Bonsignorio Montagna, married in second marriage to Lelio Giusti in 1446. This description is followed by other succinct descriptions in the Giusti family documents [

20,

21,

25]. The villa as a whole is described in greater detail in Pietro Avogaro’s letter (B.S.V.PD., doc. 1652, 647.I) written around 1495, of which a brief summary of the translation made by the authors of the text is given:

“The enclosure of the villa, called Justianum, located in the centre of the valley with the pond, fountains and gardens, is entered through a stone gate through two courtyards where, in the first and smaller courtyard, are the stables, the hayloft above, the cellar and the woodshed, while in the second and very large courtyard, there are the service buildings with the servants‘ quarters, the kitchen, the granaries, the fruit store, the larder, the oven, the aviary and the shelter where animals such as hares, chickens and rabbits are bred. On the other side of the courtyard is the lords‘ and guests’ manor house, adorned with marble and paintings, with regal entrances, noble porticoes, living rooms, bedrooms, winter and summer dining rooms with the windows of the rooms opening to the east towards the orchard and the olive-grown mountains, and to the west towards a large pool where fish swim and feed. Next to the manor house, on the side where the illustrious guest’s quarters are located, is a fine fountain with marble arches and columns on all the walls, and in the middle stands a Parian marble statue of Neptune, standing on a dolphin”.

It follows from this description that the villa described by Avogaro must not have been very different from the one depicted on the 1625 map (

Figure 6). The configuration of the villa, as already observed by other authors [

26], corresponds perfectly with the description made by the Bolognese Pietro De’ Crescenzi (ca. 1233-1320) in his

De Agricultura, with respect to the “Intrinsic disposition of the court” [

55], originally written around 1305, with later and still extant copies from between 1471 and 1495 [

55]. Later transcriptions in Florentine were made, such as the one edited by Bartolomeo De Rossi [

56], from which the following is paraphrased:

“The courtyard should be arranged in the middle and open on one side the entrance from the street and on the other, symmetrically, the exit to the farmyard, vineyard or fields. On one side of the road that divides the courtyard the lord’s house must be arranged with the long side facing the street and the short side that must not be very deep. (…) There, on the edge of the courtyard, arbour vines should be planted that will rise eight or ten feet above the ground, creating a beautiful arbour that is close to the trees. Nearby, fruit trees (figs, pomegranates, hazelnuts, jujubes and apple trees) are to be planted five or six feet from the courtyard, and further away, pear and apple trees are to be planted so that they bear fruit throughout the year. In the same place shall be built a delightful garden of fine and minute herbs, and there shall be kept the Lord’s garden, bees, and turtledoves (...). In the other half of the courtyard let houses and huts be built near the outer border, occupying one or two sides according to the need of the workers’ family and the animals. At the side of the workers’ house, the well and the oven should be built if a fountain did not already exist in the noblest part (...)”.

The description of the garden, the peach orchard, the vine arbour and the kitchen garden, named in the court layout, are taken up again later in the work (in Book VIII, the garden, the peach orchard and the arbour in Chapter III and the orchard in Chapter VIII). A paraphrased description is given briefly:

“For the garden of the Lords, a flat place with a spring will be chosen, which will spread around its places and will be enclosed with walls as high as is convenient. In the northern part, trees will be planted (called verziere) where animals can hide. In the southern part, the lords’ manor will be built so that it will shade the garden in summer and its windows will open onto the verziere. Also, there shall be made a fishpond where different kinds of fish shall feed, and there shall be placed hares, deer, rabbits and similar non-prey animals. And on certain bushes located near the manor, a house should be built with a thickly latticed copper wire roof and walls, where pheasants, partridges, nightingales, blackbirds, buntings, ferns and all kinds of birds that sing can be kept (...) A structure can be built of dry wood and vines can be planted around it, covering the whole building (...). Let it be set up in rich soil and irrigated with a fountain or a rivulet running between the separate spaces so that it can be maintained in times of great heat in order to nourish good herbs to eat, like medicine”.

The description shows how Villa Giusti-Puttini (

Figure 15) was developed according to these same rules, either because they were known at the time or because the indications themselves were part of an established tradition at the time of its construction. The layout of the main courtyard follows the east–west and north–south axes, is divided into two parts with the noble part to the south and the workers’ part to the north and is enclosed between the buildings and the surrounding walls.

A detailed description of the park and garden, with its layout and botanical species present historically, is provided by Avogaro in his letter written in 1495 (B.S.V.PD., doc. 1652, 647.I):

“Here and there box trees, cedars, laurels crown the work of the gardener. The garden is separated from the outside and in that is a spring that gurgles continuously with a gentle murmur, next to which is a cistern that conveniently receives water flowing from the spring whenever it is thirsty. The spring is enclosed by a little theatre and those who sit there hear the murmur of the fountain. The following grow and feed in the garden: wisteria, cyclamen, heliotrope, crocus, black violet, lutea, iris versicolor, elderberry, acanthus, white lily, red lily, crocea… and all species besides the common ones, such as beetroot, buglosa, lettuce, envy, mint, pygenum, sage, rosemary, leek, solanum, serpyllum, ocynum, asparagus, cordum and many other hydrangeas. Thanks to this arrangement, and to the kindness of the roofs and the garden further away from the hill, the pause is completely offered to the astonished eyes of the guests, with myrtles, laurels, cedars and box trees, which are always green with their leaves, here the border is covered on both sides with vines that are supported by marble columns, to the right of those who enter there is a Christ, perfumed with violets and roses of various kinds and variously arranged seats, which, tired of walking, help the same pause. At the other end, and by the curve approaching the walls that enclose the pool here, come a large number of violets and roses. On the other side the peach and fig trees were often leafy, and on that side he made a fountain”.

In Avogaro’s description, we can imagine how the park of the villa at that time must have been divided into different parts: the walled garden with flowers, vegetables and medicinal herbs; the orchard with peach and fig trees; the

veridarium or area with evergreen trees; and the fountains and pools. The park described is the place where the coexistence of flowers, fruit and leafy trees recalled the richness of Eden [

11] and at the same time created a coexistence between the literary and leisure garden and the variety of fruit and vegetable crops necessary for the internal consumption of the villa [

40].

The description mentions “a spring bubbling continuously with a gentle murmur, next to which is a cistern that conveniently receives water”. It is difficult to tell whether the spring was inside or outside the garden, but in any case, it must have been, if not inside, at least close by. It could be where the water enters the property through the north wall. Another element that is perhaps mentioned is the pergola that we might recognise in the description “the border is covered on both sides with vines that are supported by marble columns”.

The garden with flowers and medicinal herbs described in such detail by Avogaro must have been located on the north side of the park adjacent to the wall and is recognisable in the “garden” enclosed between walls visible on the 1625 map (

Figure 15). In the 1683 map, the wall seems to remain, but the garden is not drawn; however, it reappears in the 1735 map showing it as an “orchard” but remaining enclosed between walls. The wall enclosing this space to the south with a supposed central gateway seems to disappear in the Napoleonic cadastre (1817), perhaps to extend the orchard that seems to reach as far as the path, an extension that seems to be maintained in the following cadastres. The garden of medicinal herbs and vegetables, enclosed between walls, clearly refers to the literary idea of the

hortus conclusus [

35], the protected garden of which there are numerous literary as well as pictorial references [

37].

Another element described by Avogaro and present in historical maps is the pergola that, according to the 1735 drawing (

Figure 10), covered the paths between the manor house, the garden, the fishpond and the fountain. The pergola must have existed because it is also drawn on the 1625 map, whereas it was not drawn on the 1683 and 1798 maps. As seen in De Crescenzi’s description, vine-covered pergolas were a common element of the late medieval and humanistic garden as can be seen in many of the garden illustrations of the time [

37]. Among the illustrations, one drawing from

De Agricultura [

55] stands out: (

Figure 16a) is a view of a garden enclosed by a wall and the pergola and fountain can be seen in the background. Two other drawings are worth mentioning. The first (

Figure 16b), reported by Marchi [

57], illustrates men of letters in the

brolo of a Veronese villa: to the right of the pergola, the fishpond with two characters fishing reminds us of the spatial relationship between the pergola and the fishpond of Villa Giusti-Puttini. The last illustration (

Figure 16c), from the publication

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili by Francesco Colonna (1495), shows a pergola with a clear classical taste, with marble or wooden columns with classical forms and clearly wooden ribs for the transverse laths. This element is reminiscent of classical architecture and shows a clear humanist taste that initiates antiquarian culture [

34]. Since this is the garden of Giusto Giusti, well known for his literary activity in the humanist environment of Verona, these two illustrations seem relevant as a reference for a possible pergola in the garden of his villa. Moreover, the depiction of the classical pergola reminds us of Avogaro’s description.

With respect to the statue of Neptune, king of the seas in Greek and Roman mythology, mentioned by Avogaro in his letter, there have been countless examples of this element since Roman times. Neptune was often placed in the centre of fountains and fishponds, and the statue of Neptune described by Avogaro, naked, of Parian marble (uniform white and fine grain), at whose feet stands a dolphin, vibrating his trident is entirely plausible. Strangely, this statue that so impressed Avogaro, does not appear in any other description or historical map. It could perhaps have been placed on the central element of the circular fishpond, clearly visible in the 1625 map (

Figure 15), but it is difficult to go any further in the hypothesis with the information we have so far.

In the map of the villa dated 1625 (

Figure 15), the fountain located in the centre of the park’s path appears to bear the inscription “Musa Caliope”, this figure being fully consistent with the profile of a literary and juristic lord such as Giusto Giusti was. The Greek muse Calliope is the muse of poetry and the goddess of eloquence that she bestowed on rulers and crowned with laurel. She is depicted with a waxed tablet or parchment and a stylus for writing. Unlike the statues of Neptune, which are very frequently associated with fountains, basins or springs, we have not found the presence of the muse Calliope linked to fountains. The fountain under discussion in the 1625 drawing would appear to be surrounded by a structure drawn with the line used for walls (continuous line and marron-coloured field). Again, however, the lack of certain data prevents a reliable hypothesis on the layout of the fountain.

3.4. The Present Garden: Elements of Permanence and Absence

As can be appreciated through the study of historical maps, the villa has maintained a constant layout over time in the structure of the two courtyards, the outbuildings, the pigeon tower, the manor house and the parts of the garden in the immediate vicinity (

Figure 17). The

brolo of the villa is inextricably connected with the built part of the villa. The buildings are concentrated in the north-western part of the property area and create a visual reference in the landscape of the villa as a whole, as the tower in particular is visible from all parts of the

brolo.

The transformation of the landscape took place progressively over the centuries (

Figure 18): the construction of new buildings as early as the 17th century led to the formation of the two present-day courtyards; the loss of part of the

brolo in the northern edge to the village from the 17th century onwards and then consolidated over the centuries to its current situation; the construction of buildings and private gardens in the western edge of the

brolo that completely occupied the south-west corner of the property between 1950 and 1970; and the loss of the entire eastern strip of the

brolo with the construction of the building in the north-east corner and the sports field from 1970 onwards.

If the occupation of the northern part of the brolo by the borough is of long standing and therefore, in a certain sense, an operation that has been metabolised by the villa, the interventions of the second half of the 20th century have opened new wounds in the layout of the whole area. The construction of the buildings in the south-west corner involved the elimination of the brolo wall and the removal of the niche of St. Anthony from the corner itself and its reinsertion on the other side of the street. The construction of the building in the north-east corner of the brolo involved the insertion of a large construction which, although in the extreme and barely visible from the building, constitutes an important element of impact on the whole area. The sports field, apparently harmless as a green element, completely eliminates the eastern access to the villa and truncates the path of the tree-lined path that once ran through the brolo from the fountain to the boundary wall in this position. The tree-lined path, or at least the path that led to the eastern exit, is depicted on historical maps up to 1798, and must have been a characteristic element of the park.

On the other hand, the presence in the park of certain elements allows traces of the park’s history to be found (

Figure 19). These include the following: the northern and southern walls of the

brolo, the southern access through the wall and the path through the

brolo to the manor house surrounded by vineyards, the circular fishpond, the stone canals that still allow the water to flow, the possible remains of the fountain, the orchard that, although it has lost its surrounding wall, remains located where it was in the past, and the trees surrounding the fishpond.

The built elements that characterise the park include the limits of the villa, the boundaries between its parts and some paths: the

brolo wall (

Figure 20), built with a masonry of limestone alternated with courses of flat red breccia; the path that joins the southern entrance and the manor, bordered by a terraced wall that saves the difference in height between the two parts of the

brolo; and the wall that separates the main courtyard from the garden and the

brolo that, despite later modifications, remains the constant boundary between the inhabited and cultivated parts of the villa. The wall of the

brolo is lost to the west at the point where the football pitch is inserted, but it is precisely in the ramp that gives access to the football pitch that a section of the historic wall that closed the

brolo to the east remains and possibly still preserves the hole of the ancient eastern access to the villa (

Figure 21). Although this element materially remains, its total decontextualisation means that the east–west axis that characterised the

brolo in the past has now been lost.

The map of 1735 (

Figure 10) shows, as already commented, a rusticated entrance portal marking the southern entrance as a representative entrance to the villa. This is the access portal through which one enters the courtyard from the west side today and may, therefore, have been moved here at the time when this entrance was remodelled. Without having any concrete data on this fact, we could hypothesise that this alteration took place between 1950 and 1970 when the houses were built on the eastern boundary of the villa and, therefore, this whole side of the property was altered. Nevertheless, the emphasis that the rusticated portal gives to the southern entrance strongly marks the two perpendicular axes structure pointed out by De Crescenzi. At present, this axis of the villa is preserved, which starts from the same southern access and crosses the

brolo to the manor house and then joins the east–west route leading into the courtyards.

The waterway is undoubtedly one of the elements that most strongly characterises the landscape of the villa and which, although not entirely complete, remains as a strong mark across the centuries. The water comes from the natural spring that lies about 100 metres north of the Roman hypogeum [

18]. The continuous slope of the land means that the water flows in stone canals probably built in Roman times from the mountain down to the valley. Along this route is the

brolo of Villa Giusti-Puttini. The water route has been extensively depicted on historical maps from 1625 onwards (see

Section 3.2) and has also been included in descriptions such as the letter written by Avogaro around 1495 (B.S.V.PD., doc. 1652, 647.I) (see

Section 3.3). Some fundamental elements remain from this route, such as the water inlet on the property from the north side (

Figure 22), the stone canals running along the

brolo built with stone elements (probably a grey limestone from Noriglio, [

58]) shaped in the form of a canal and connected together with very thin joints (

Figure 23), the circular fishpond between the reeds also built with the same stone (

Figure 24) and the moat on the southern side of the manor house. The circular fishpond must have played a fundamental role in the organisation of the water flow and at the same time provided an element of coolness in the hottest periods. At the centre of the fishpond is a rocky cone on which a sculpture could be placed, perhaps the Neptune described by Avogaro. According to De Crescenzi’s description, the fishpond was not only a decorative element but also the place where the fish necessary to feed the family were raised.

Other elements, however, have been lost, although traces of them remain: the fountain, known as the fountain of Calliope in the map of 1625, which can perhaps be identified in the lapidary fountain still existing in the garden (

Figure 25), and the large rectangular fishpond, closed in 1683, of which there is no clear material trace except for the rectangular shape of the garden in front of the west façade of the manor house.

This large basin located between the west façade of the palazzo and the pigeon tower, depicted in 1625 as a pond surrounded by walls, was described in the 1683 plan as a “ruined fishpond now orchard”, in that of 1735 as an orchard and in that of 1798 as a garden. The presence of this pond would explain why there was initially no access door to the manor house from the west side, which only opened, as shown by its posteriority to the Renaissance frescoes [

20], in a later period that could be identified as between 1625 and 1683. Among the stone fragments scattered in the park, one also encounters tombstones, most probably Roman, capitals that connect the villa to the former Roman settlements in the valley and the presence of a Roman necropolis, which should be studied archaeologically.

The park of the villa was evidently very much determined by the green elements. As we have seen, the letter written by Avogaro went in depth into the description of the garden rich in flowers, vegetables and herbs. This garden, judging by the map of 1625, was in the northern part of the property and delimited by a perimeter wall. It was a garden with four flowerbeds, a fountain in the middle and an underground canal that fed the fountain and nourished the plant life. This garden, now transformed into an orchard (

Figure 26 and

Figure 27), does not appear on either the 1683 or the 1798 map, but it does appear on the 1735 map where it is depicted as an orchard bounded by walls and with an access gate from the south side. It should be noted that the memory of the orchard remains today in the type of cultivation of this part of the garden. The perimeter wall was probably removed after 1735, but the location of the orchard remains in this same area to the present day.

In addition to the garden, there are other green areas in the

brolo that deserve attention. Firstly, there is an area of leafy trees (

Figure 19) to the east of the manor house, which could be interpreted as the “verziere” described by De Crescenzi, with large trees to shade the manor house. Beyond these trees, the vineyards now extend beyond the manor house and occupy the whole of the rest of the

brolo. Vineyards are the main crop in Valpantena, already present in this valley since the Roman times and increased after the Venetian domination [

59]. Its presence in the properties of the Giusti family has already been recorded in the map of 1598 where the lands of Vendri are defined as cultivated with vines. On the other hand, it is difficult to confirm that the Villa Giusti-Puttini

brolo was dedicated to the cultivation of vineyards from a very early date. In the letter written by Avogaro, it is stated that “the windows of the rooms opening eastwards towards the fruit tree area and the mountains were planted with olive trees”, so perhaps the

brolo was more destined to fruit trees and perhaps the surrounding fields to the cultivation of vineyards, while on the hills above, olive trees were cultivated. The hypothesis that the

brolo was largely cultivated as an orchard is also supported in the advice given by De Crescenzi regarding cultivation for the villas. The orchard, with figs, pomegranates, hazelnuts, jujubes, pear and apple trees allowed for fresh fruit throughout the year. Nevertheless, the extension of Villa Giusti-Puttini’s

brolo would have perfectly allowed the fruit trees and the vineyards to coexist.