The Use of Public Spaces in Traditional Residential Areas After Tourism-Oriented Renovation: A Case Study of Liu Xing Street in Yining, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Public Spaces and Users

2.2. Impacts of Tourism on Urban Public Spaces

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Background

3.2. Study Site

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Database Creation and Analysis Techniques

4. Results

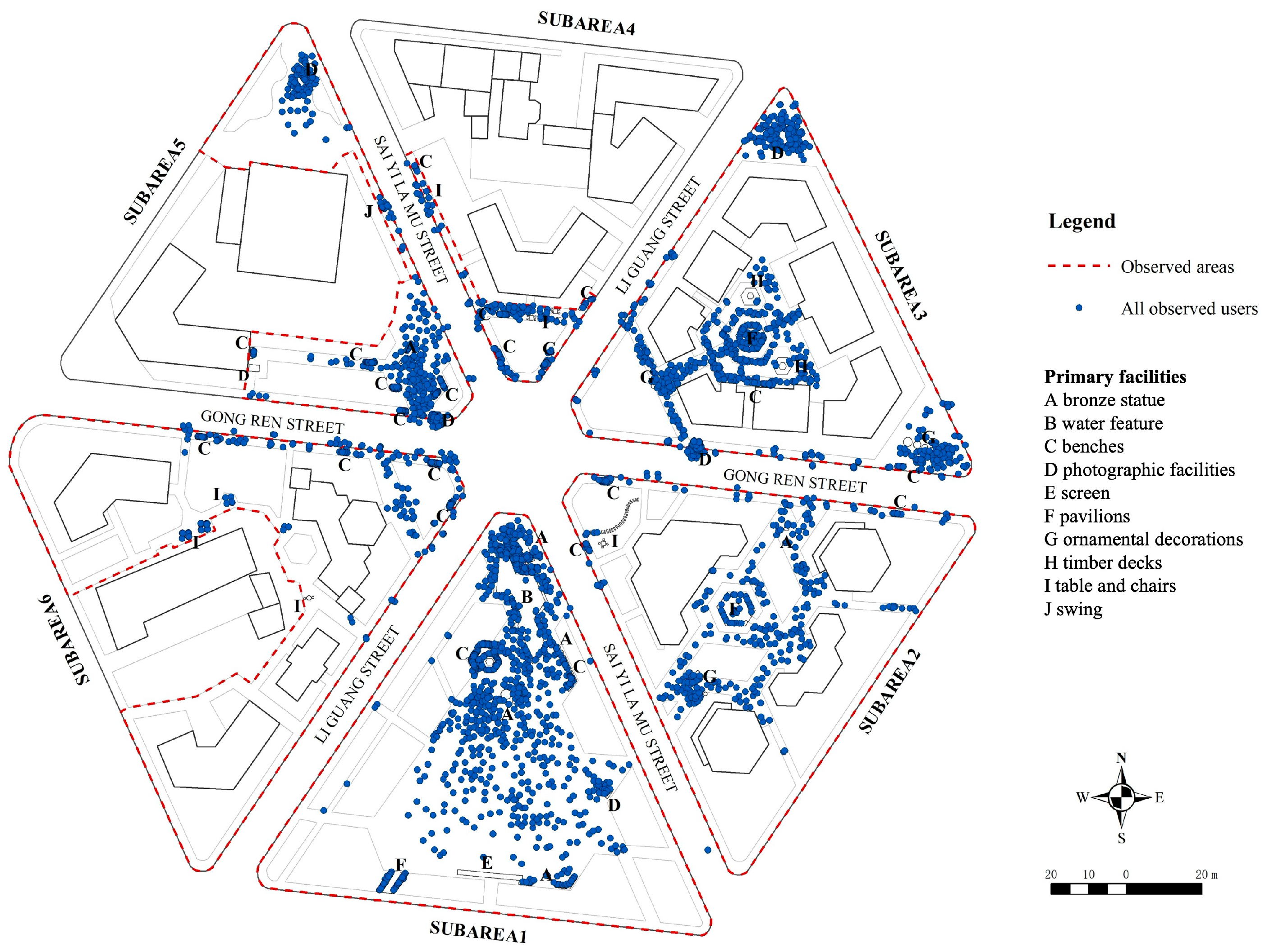

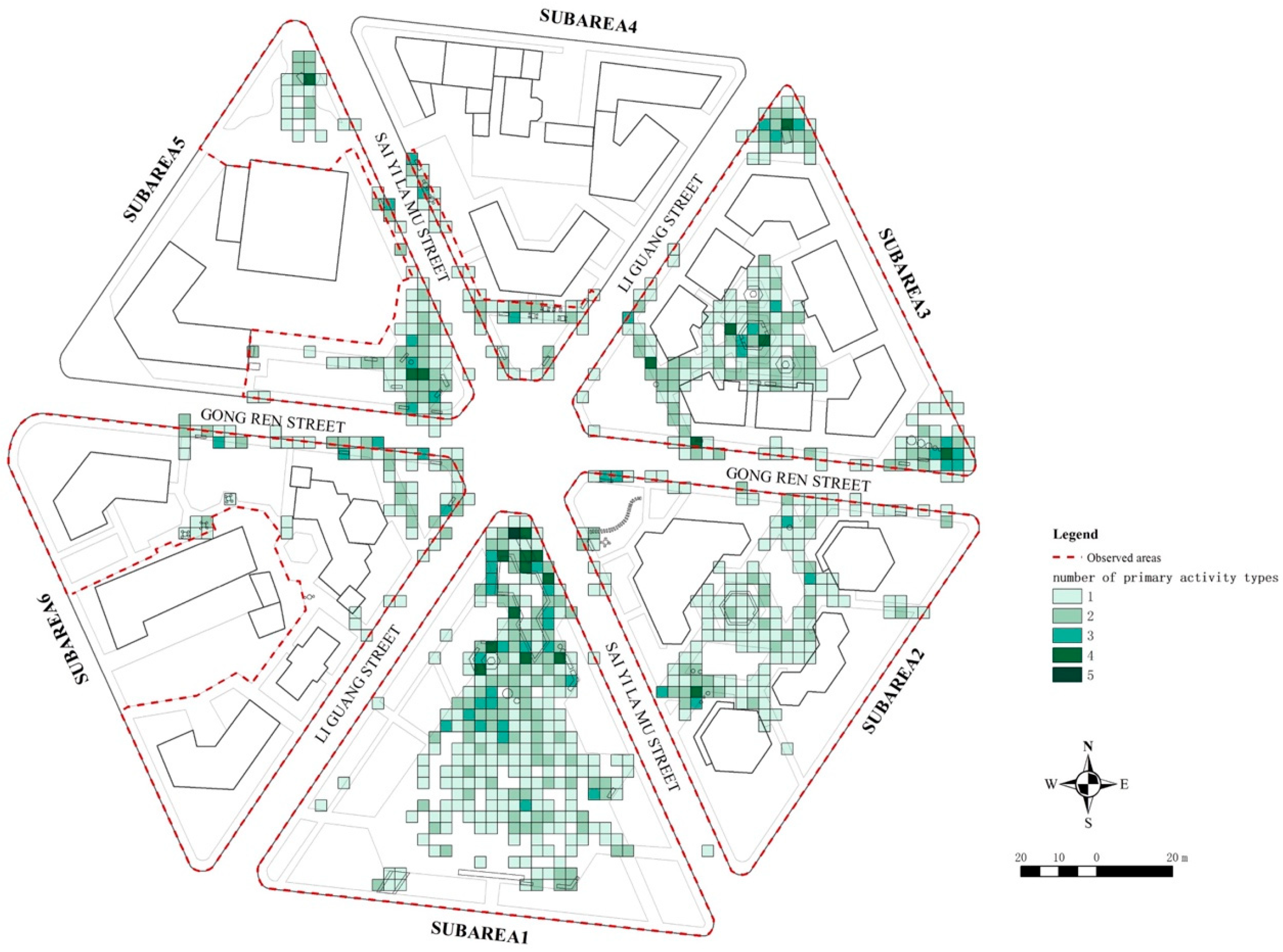

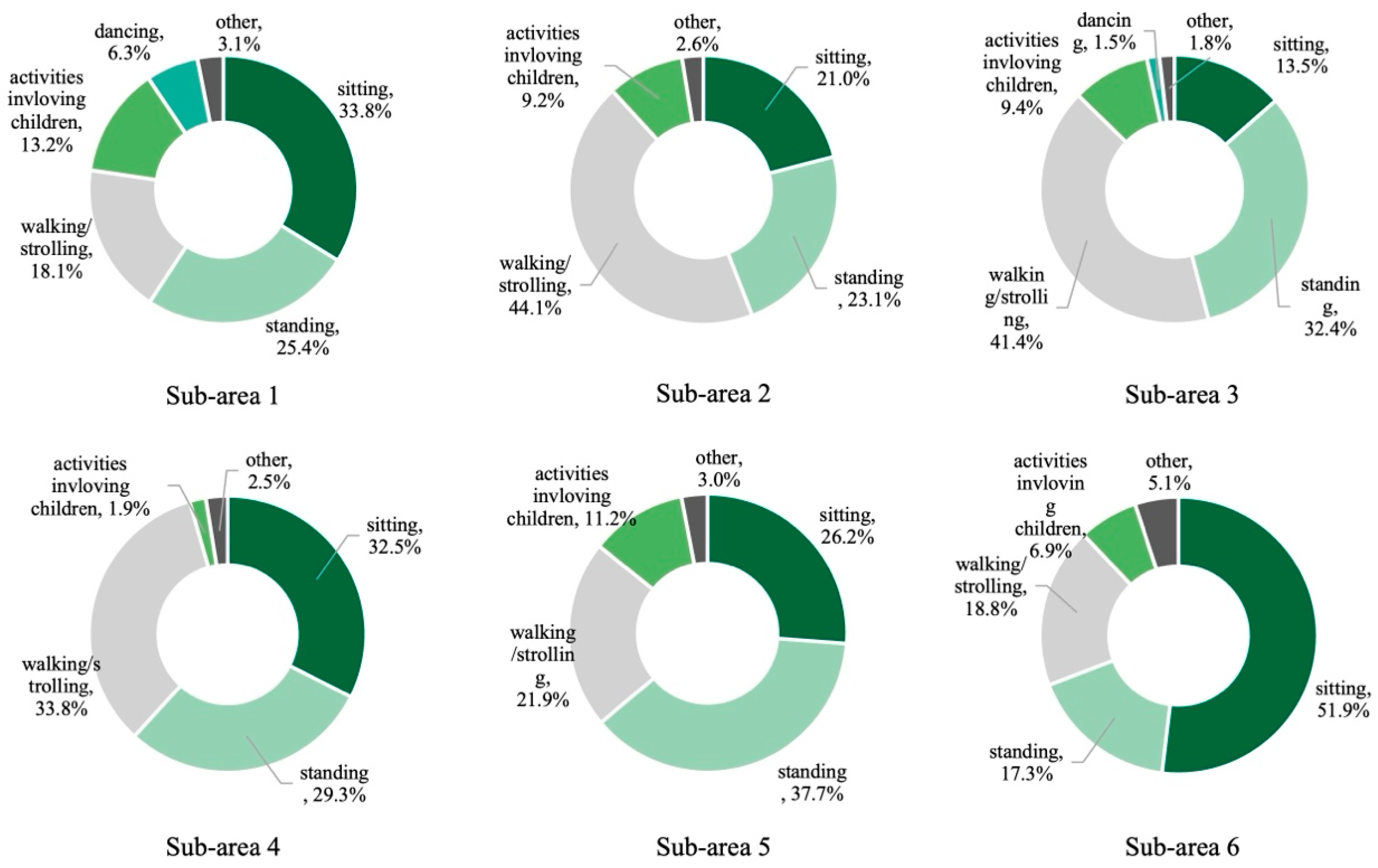

4.1. Activities Observed

4.2. Spatial Distribution of Activities in Each Sub-Area

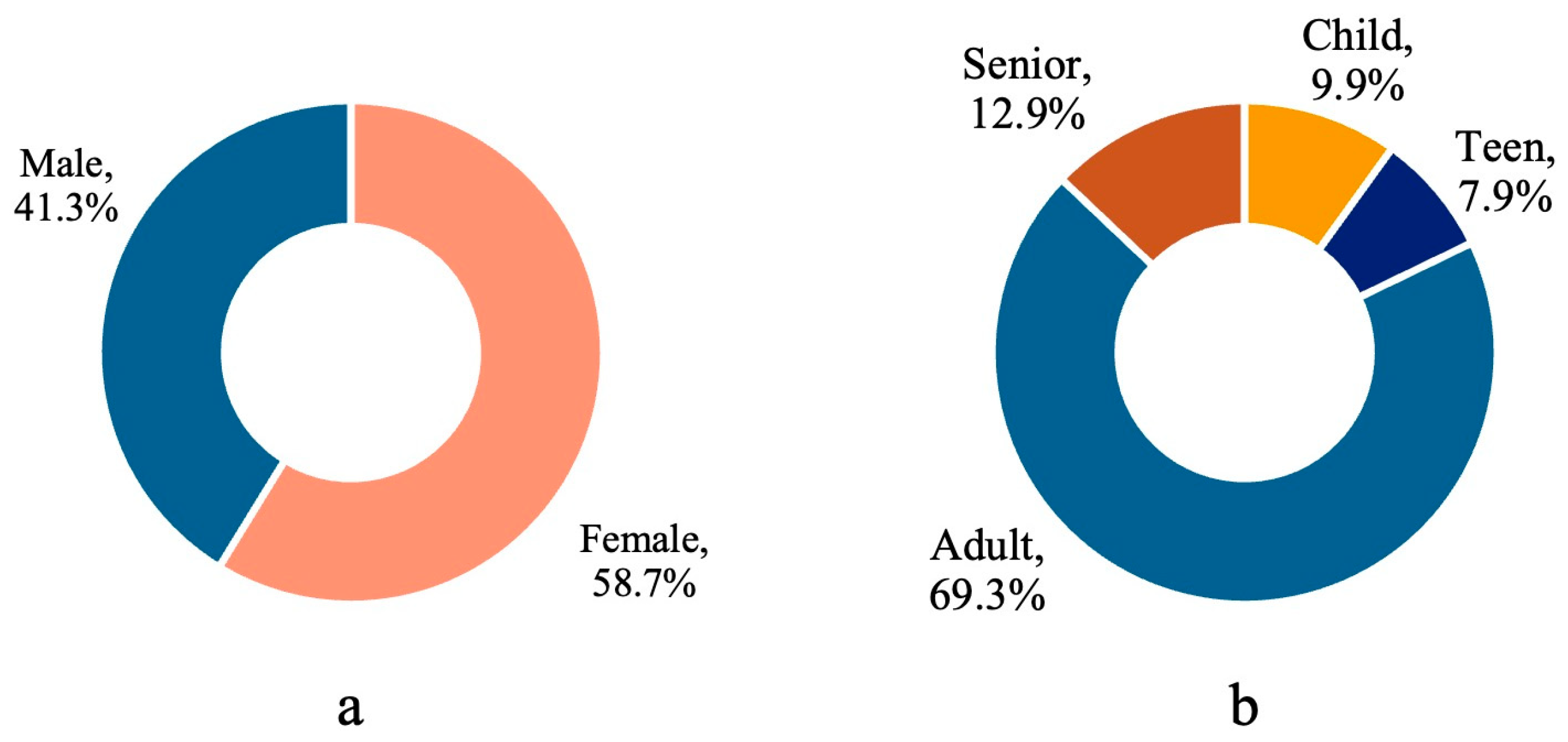

4.3. Users from Different Groups

5. Discussion

5.1. Site Characteristics and Activities

5.2. The Use of Facilities

5.3. Users’ Usage Trends

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez, E.; Alfonso, L. Residents’ opinions and perceptions of tourism development in the historic city of Toledo, Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z. Reinterpreting activity space in tourism by mapping tourist-resident interactions in populated cities. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 49, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Who is the city for? Overtourism, lifestyle migration and social sustainability. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 24, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Duignan, M. Progress in Tourism Management: Is urban tourism a paradoxical research domain? Progress since 2011 and prospects for the future. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-J.; Li, M.; He, J.; Chan, W.K. Conflicts and interactions in urban tourism: Use of urban public space by residents, tourists, and migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2024, 105, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, M.; De la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city centres under pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.L. Culture, heritage and access to open spaces. In Open Space: People Space; Thompson, C.W., Travlou, P., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2007; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.W. Urban open space in the 21st century. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 60, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, D.P. The historical development of urban open space. In Urban Open Spaces; Taylor, L., Ed.; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V. Evaluating public space. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 53–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budner, W.W. The evaluation of the equipment and quality of the public space of Poznań. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2016, 24, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, A.H.; Soltani, S. Determinants of a successful public open space: The case of Dataran Merdeka in the city centre of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Landsc. Res. 2018, 44, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.; Lynch, K. Open space: Freedom and control. In Urban Open Spaces; Taylor, L., Ed.; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, K. How To Turn A Place Around: A Placemaking Handbook; Project for Public Spaces: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlee, M.; Omar, D.; Mohd Yunus, R.; Samadi, Z. Attributes of successful public spaces through users perception. Asian J. Qual. Life 2018, 3, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Li, D.; Wu, C.; Wu, H. Urban park facility use and intensity of seniors’ physical activity: An examination combining accelerometer and GPS tracking. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C. Characteristics of Public Space Behavior and Demand of Rural Residents in Foshan. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 276, 02011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahriny, F.; Bell, S. Patterns of urban park use and Their relationship to factors of quality: A case study of Tehran, Iran. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, W. Increasing the use of large-scale public open spaces: A case study of the North Central Axis Square in Shenzhen, China. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, K.; Yan, Y.; Xu, P. Characteristics of Urban Parks in Chengdu and Their Relation to Public Behaviour and Preferences. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. Perceptual information of “an entirely different order”: The “cultural environment” in the senses considered as perceptual systems. Ecol. Psychol. 2017, 29, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.F.; Thompson, C.W.; Aspinall, P.; Bell, S. Communities facing urban depopulation: Exploring people’s environmental preferences. A case study of Lisbon, Portugal. Cities Health 2020, 6, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrunoff, N.A.; Yi, N.X.; Dickens, B.; Sia, A.; Koo, J.; Cook, A.R.; Lin, W.H.; Lu, Y.; Hsing, A.W.; Dam, R.M.v.; et al. Associations of park access, park use and physical activity in parks with wellbeing in an Asian urban environment: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, H.; Han, R. Residents’ Preferences and Perceptions toward Green Open Spaces in an Urban Area. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Conejos, S.; Chan, E.H.W. Social needs of the elderly and active aging in public open spaces in urban renewal. Cities 2016, 52, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tang, X. Evaluating the effectiveness of community public open space renewal: A case study of the Ruijin community, Shanghai. Land 2022, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Kang, J. Social relationships and patterns of use in urban public spaces in China and the United Kingdom. Cities 2019, 93, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Shim, C. Comparing resident and tourist perceptions of an urban park: A latent profile analysis of perceived place value. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chiou, S. A study on the sustainable development of historic district landscapes based on place attachment among tourists: A case study of Taiping Old Street, Taiwan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristianova, K.; Jaszczak, A. Historical Centers of Small Cities in Slovakia—Problems and Potentials of Creating Livable Public Spaces. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 022012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwah, A.A.Q.; Li, W.; Alwah, M.A.Q.; Shahrah, S. Developing a quantitative tool to measure the extent to which public spaces meet user needs. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.; Francis, M.; Rivlin, L.G.; Stone, A.M. Public Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Merylova, I.; Smilka, V.; Kovalska, G. Public spaces in historic environment as urban fundamentals of sustainable development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1275, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Cheng, T.; Wang, T.; He, Q. The theory and practice of urban renewal in China. China Anc. City 2021, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Liu, J. Urban Sociology; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. Research on the progress of Chinese urban renewal in the last decade. In Proceedings of the Urban Planning Annual Conference, Chongqing, China, 19 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X. Vitality Evaluation of Public Spaces in Historical and Cultural Blocks Based on Multi-Source Data, a Case Study of Suzhou Changmen. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiaerken, M. Investigation of the renewal and development path of Liu Xing Street within the context of cultural tourism integration. Tour. Overv. 2024, 4, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S. Research on the Protection and Innovative Application of Water Landscape in Yili Traditional Historical and Cultural Blocks—Taking Liuxing Street as an Example; Shihezi University: Shihezi, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Teng, S.; Molake, A.; Liu, F. The application of regional architectural culture in the renewal design of Liuxing Street in Yining City. Huazhong Archit. 2023, 41, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xue, S.; Hou, M. “Harmony in Diversity”: Study on the strategies of embedding new buildings in the historic districts—A case of the section on the west side of Worker’s Street on Liuxing Street in Yining. Urban. Archit. 2022, 13, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D. Research on the Production of Tourism Space in Historical and Cultural Block: A Case Study of Liuxing Street in Yining City; Xinjiang University of Finance & Economics: Urumqi, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dilimulati, N. Study on Block Protection and Micro Renewal: A Case Study of Liuxingstreet, Yining City, Xinjiang; Xinjiang University: Urumqi, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. Research on the Protection Division of Liuxing Street in Yili City from the Perspective of Place; Southwest University of Science and Technology: Mianyang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Dialysis on the Multicultural Connotation of Xinjiang Traditional Ethnic Constructs—From the Ethnic Constructs to See the Exchange Between the Ethnic Relations; Xinjiang University: Urumqi, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reheman, A.; Ma, D. A Brief History of Uygur Culture; Xinjiang Remin Press: Urumqi, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S. The Diversity of Xinjiang; China Intercontinental Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, S. Research on the Protection and Renewal of Ayidun Historical District in Yining City; Chongqing University: Chongqing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K. The Regional Research of Vernacular Architecture in Xinjiang, Yili; Southwest University of Science and Technology: Mianyang, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Xinjiang Traditional Dwellings; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dilixiati, D. Analysis of the modelling and decoration of traditional Uygur dwellings doors and windows in Yili, Xinjiang—Taking Xinlu street residence in Yining city as an example. Design 2018, 23, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L. Investigation and exploration of the elite in the Liuxing Street tourist community in Yili. Tour. Overv. 2023, 17, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, J. Syntactic analysis of historical and cultural neighbourhoods in Yining City—Taking Six Star Street as an example. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 43, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marušić, B.G.n.; Marušić, D. Behavioural maps and GIS in place evaluation and design. In Application of Geographic Information Systems; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.W.; Aspinall, P.; Bell, S. Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space 2; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.C.; Cosco, N.G. Using behaviour mapping to investigate healthy outdoor environments for children and families. In Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 55–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Bell, S.; Scott, I.; Qian, J. Everyday use of urban street spaces: The spatio-temporal relations between pedestrians and street vendors: A case study in Yuncheng, China. Landsc. Res. 2019, 45, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlkvist, E.; Engström, M.; Nilsson, A. Residents’ use and perceptions of residential care facility gardens: A behaviour mapping and conversation study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2020, 15, e12283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Fleming, L.E.; Grellier, J.; Kuhlmann, F.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; White, M.P. Urban Blue Spaces Planning and Design for Water, Health and Well-Being; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiljev, P. BlueHealth Behaviour Assessment Tool: A Protocol for Acquiring Data from Participant Site Observation. 2020. Available online: https://bluehealth2020.eu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/BlueHealth-Behaviour-Assessment-Tool-data-acquisition-protocol.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Bell, S.; Vassiljev, P.; Wilczynska, A. BlueHealth Behaviour Assessment Tool: A Guidebook for Analysing Data from Participant Site Observations. 2020. Available online: https://bluehealth2020.eu/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/BlueHealth-Behaviour-Assessment-Tool-analysis-guidebook.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Goličnik, B.; Thompson, C.W. Emerging relationships between design and use of urban park spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Population Census Yearbook 2020; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Talbot, J.F.; Kapla, R. Judging the sizes of urban open areas: Is bigger always better? Landsc. J. 1986, 5, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, P. People, Paths and Purposes: Notations for Participatory Envirotecture; Seattle University of Washington Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczyńska, M. Warsaw small and medium-sized public urban green spaces as a response to short-time leisure needs of local residents and passers-by. Leis. Stud. 2024, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Ma, J. Exploring Design Interventions to Enhance Intergenerational Sharing: An Importance–Performance Analysis of Public Spaces in Changsha, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, C.; Lu, H.; Che, S. Rational planning of public open space by exploring the effects of environmental factors on human recreation—A case study in Shanghai, China. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 1247–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavampour, E.; Aguila, M.D.; Vale, B. GIS mapping and analysis of behaviour in small urban public spaces. Area 2017, 49, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G.R.; Rock, M.; Toohey, A.M.; Hignell, D. Characteristics of urban parks associated with park use and physical activity: A review of qualitative research. Health Place 2010, 16, 712–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Xie, X.; Marušić, B.G. What attracts people to visit community open spaces? A case study of the Overseas Chinese Town Community in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofa, R.A.; Bonotulshi, D.; Guaralda, M. ‘GenUrban: Shaping cities for all genders’—Right to the city planning framework, Hong Kong. Cities 2024, 150, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Activities | Gender | Age | All | % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Child | Teen | Adult | Senior | |||

| Sitting | 429 | 416 | 26 | 52 | 586 | 181 | 845 | 27.7 |

| Crouching | 17 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 17 | 1 | 26 | 0.9 |

| Lying down | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0.1 | |||

| Standing | 568 | 291 | 15 | 81 | 696 | 67 | 859 | 28.1 |

| Walking/strolling | 502 | 364 | 42 | 92 | 621 | 111 | 866 | 28.4 |

| Walking with a child | 63 | 17 | 2 | 57 | 21 | 80 | 2.6 | |

| Walking a dog | 8 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 12 | 0.4 | ||

| Using a wheelchair | 9 | 10 | 13 | 6 | 19 | 0.6 | ||

| Pushing a stroller | 15 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 19 | 0.6 | ||

| Street sweeping | 14 | 4 | 18 | 18 | 0.6 | |||

| (Child) playing freely | 86 | 83 | 168 | 1 | 169 | 5.5 | ||

| (Child) playing on equipment | 7 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 0.3 | |||

| Playing on a swing | 8 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 14 | 0.5 | |

| (Child) riding a scooter | 2 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 0.2 | |||

| Riding a baby trike | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.1 | |||

| Roller skating | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.1 | |||

| Riding a bike | 1 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 0.2 | ||

| Playing football | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0.2 | ||||

| Playing badminton | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0.1 | |||

| Dancing | 56 | 22 | 2 | 4 | 70 | 2 | 78 | 2.6 |

| Skipping rope | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | ||||

| Total | 1793 | 1259 | 303 | 241 | 2114 | 394 | 3052 | 100.0 |

| Descriptions | Photos of Each Sub-Area |

|---|---|

| Sub-area 1: Due to the equal division of the hexagons, the area of each sub-area is similar, approximately 3000 m2 in area. Benches, bronze statues, pavilions, etc., are the main facilities of this area. The open space here provides opportunities for various activities, such as public square dancing and children playing football. Older people often sit on benches to enjoy the sunshine, while younger people sit at the edge of the water feature to watch their children playing freely. |  |

| Sub-area 2: This area is surrounded by shops that sell local specialties. Many people often stop to take photos with decorative ornaments, especially parents with their children, or sit in the pavilion to rest. |  |

| Sub-area 3: The architecture in this sub-area exhibits the typical features of Uyghur traditional houses in the city of Yining. In addition to the Russian-style architecture, the garden filled with beautiful flowers is an important part of traditional Uyghur houses. Similarly, this sub-area is filled with various flowers that attract many visitors, especially during spring and summer. Furthermore, during the tourist season, there are sometimes some short folk song and dance performances that attract visitors to stop and watch. |  |

| Sub-area 4: This sub-area has the least number of users and types of activities among all the sub-areas as there is limited space and facilities. Tables and chairs are temporarily provided by the nearby shops. People often stop here to sit and rest. |  |

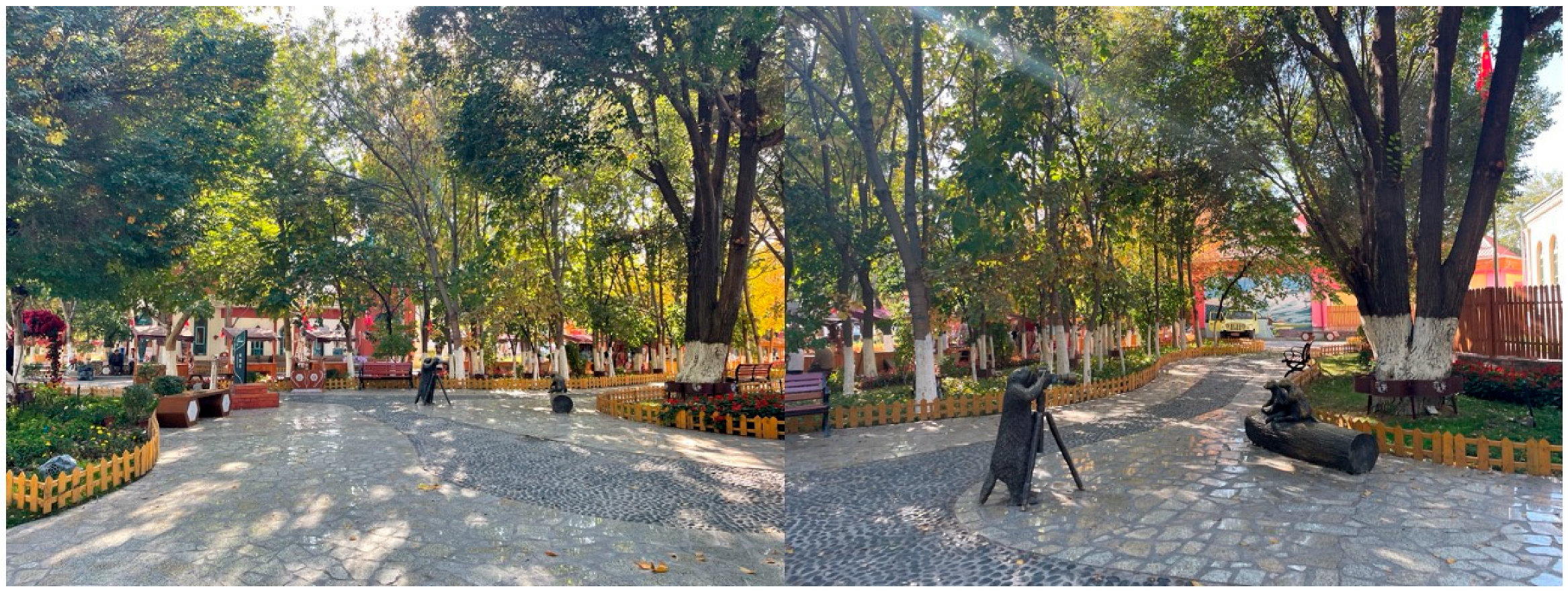

| Sub-area 5: The mosque and public toilet are the main buildings in this sub-area. Since the mosque gate was closed during the observation period, only the surrounding areas were observed, and the front area of the public toilet was excluded. Tall trees provide plenty of shade in this area, making it one of the favourable spots for resting, especially in summer. In addition, a piano and an old car serve as decorative elements to enrich the space. |  |

| Sub-area 6: Although this sub-area provides some tables and chairs, very few people use them. In contrast, people prefer to sit on the benches along the streets, which offer a good view. As a result, this sub-area has become a place for a brief rest. |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dilixiati, D.; Bell, S. The Use of Public Spaces in Traditional Residential Areas After Tourism-Oriented Renovation: A Case Study of Liu Xing Street in Yining, China. Land 2025, 14, 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051041

Dilixiati D, Bell S. The Use of Public Spaces in Traditional Residential Areas After Tourism-Oriented Renovation: A Case Study of Liu Xing Street in Yining, China. Land. 2025; 14(5):1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051041

Chicago/Turabian StyleDilixiati, Dilidaner, and Simon Bell. 2025. "The Use of Public Spaces in Traditional Residential Areas After Tourism-Oriented Renovation: A Case Study of Liu Xing Street in Yining, China" Land 14, no. 5: 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051041

APA StyleDilixiati, D., & Bell, S. (2025). The Use of Public Spaces in Traditional Residential Areas After Tourism-Oriented Renovation: A Case Study of Liu Xing Street in Yining, China. Land, 14(5), 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14051041