Abstract

In recognition of the declining state of biodiversity, the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, signed in late 2022, committed countries to the protection of 30% of the Earth’s terrestrial and inland water areas and coastal and marine areas by 2030. Australia has committed to this target at a national level. The majority of public protected areas (e.g., national parks) in Australia are designated and managed by state and territory governments. The state of Victoria in southeastern Australia has a long history of regional assessments of public land to balance conservation (such as the declaration of protected areas), production of natural resources (e.g., timber harvesting, mineral extraction), and recreation, amongst other uses. The decision to phase out native forest timber harvesting on public land in Victoria presents the greatest opportunity in the state’s history to meet its statewide commitments, national commitments, and international targets, by establishing a comprehensive, adequate, and representative protected area system. We critique Victoria’s reliance on non-binding protections, such as Special Protection Zones in state forests over recent decades, and outline the principles and rationale for the expansion of the protected area system in state forests, recognizing that protected areas are part of a broader suite of future land uses for these public forests.

1. Introduction

In 2022, nations around the world committed to protecting 30% of lands, freshwaters, and oceans by 2030 (the “30 × 30 protection target”) and ensuring the networks were ecologically representative and well connected as part of the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework [1]. Australia has made a commitment to protecting 30% of its lands and 30% of its oceans at the national level, with support from all Australian states and territories [2,3]. This commitment continues Australia’s nationally agreed, science-based approach to developing a comprehensive, adequate, and representative (CAR) National Reserve System over the past three decades in collaboration with state governments, non-government organisations, private landholders, and traditional custodians [4,5]. Building a CAR reserve system was also a fundamental component of the National Forest Policy Statement and subsequent Regional Forest Agreements, guided by the Nationally Agreed Criteria for the Establishment of Comprehensive, Adequate, and Representative Reserve System for Forests in Australia (known as the “JANIS criteria”, developed by the Joint ANZECC [Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council]/MCFFA [Ministerial Council on Forestry, Fisheries and Aquaculture] National Forest Policy Statement Implementation Sub-committee) [6].

In Australia, four key pathways have been identified by science and policy experts to achieve Australia’s 30 × 30 ambition in a comprehensive, adequate, and representative manner [7]. These include land acquisition facilitated by a large, dedicated land purchase fund, increased support for Indigenous Protected Area establishment and long-term funding, increased support for conservation covenanting programs (which enable the formation of privately protected areas), and the designation of suitable public land as protected areas [7]. These build on existing or past successful programs for protected area expansion [8]. The Australian Government’s 30 × 30 roadmap [5] largely acknowledges these pathways but funding allocated does not yet match the ambition and need.

Under the Australian Constitution and Australian federation, the management of public land is mostly the responsibility of state and territory governments. This includes the management of national parks, public conservation reserves, and state forests. Hence, while the Australian national government is the only government to be able to sign international agreements (such as the Convention on Biological Diversity), the actual delivery of any protected area targets on public land (including changes to state forests) has to be carried out by state governments [9]. There is thus a continuous tension between the national interest and states’ rights, a political challenge shared by most federated states (e.g., [10]). Nonetheless, the states and territories have agreed to work with the Australian Government to deliver the 30 × 30 commitment across the country [2,3,5].

Here, we explore the opportunity presented by the decision to end the harvesting of timber in native forests on public land in the Australian state of Victoria for the expansion of the protected area estate to meet state, national, and international protected area targets. We also discuss the priorities for expansion and the tensions and challenges faced. This has applicability to other Australian jurisdictions that have phased out forestry (Western Australia) or may do so in the future.

2. Victoria’s Protected Area System

In Victoria, public land use assessment and planning has been informed by a series of independent statutory bodies since 1970: the Land Conservation Council, Environment Conservation Council, and Victorian Environmental Assessment Council [11,12,13]. These bodies have played a major role in mediating environmental conflicts over public land use and have significantly contributed to the increased size and coverage of Victoria’s protected area system [13], both on land and in the territorial waters [14,15]. Other complementary mechanisms for building the protected area system include conservation covenants on private land [16], land purchase to expand the public protected area estate [17,18], and the recognition of Indigenous Protected Areas (e.g., [19]).

Despite progress, there are still significant gaps in the system, including on public land [20,21]. Victoria’s Biodiversity Strategy, Biodiversity 2037 [22], clearly states the value of protected areas for biodiversity conservation: “Permanently protected habitats on public and private land and waters—in national parks, conservation reserves and Indigenous protected areas, and under covenants—form the backbone of biodiversity conservation. To maintain and improve biodiversity, the extent and condition of these permanently protected areas need to be enhanced”. The strategy further recognizes the need to expand the protected area estate: “Maintenance and improvement of Victoria’s system of protected areas requires a comprehensive, adequate, and representative protected area system across public land, private land and Indigenous protected areas, that continues to be the cornerstone of conserving biodiversity”.

3. Forestry Transition as an Opportunity for Protected Area Expansion

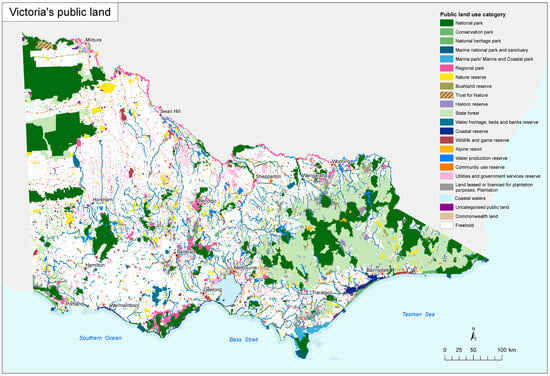

Public land categorized as “state forest” comprises approximately 3,148,800 ha in Victoria (13.8% of the state and 38.7% of all public land) [21]. Timber harvesting on public land has primarily occurred in state forests in Victoria. In November 2019, the Victorian Government announced that it would phase out native forest logging on public land (state forests; Figure 1) by the year 2030 [23]. However, on 23 May 2023, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews unexpectedly announced that the timeline would be brought forward and would “transition away from native timber logging earlier than planned—by 1 January 2024” [24]. The announcement stated “The Government will establish an advisory panel to consider and make recommendations to Government on the areas of our forests that qualify for protection as National Parks, the areas of our forests that would be suitable for recreation opportunities—including camping, hunting, hiking, mountain biking and four-wheel driving—and opportunities for management of public land by Traditional Owners” [24]. Within the announcement, the Victorian Minister for Environment, Ingrid Stitt, stated “This transition will see the largest expansion to our public forests in our state’s history—further protecting our precious biodiversity and endangered species” [24].

Figure 1.

Public land in Victoria, Australia, showing the extent of state forests (light green) in 2024 (source: adapted from [21]).

The Victorian Government announced two processes (the Eminent Panel for Community Engagement and the Great Outdoors Taskforce) to consider the future use and categories for public land in the state forests of eastern Victoria. The use of these processes represented a deviation from the use of the dedicated statutory authority, the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council (VEAC), which typically advises government on landscape-scale public land use allocations. VEAC’s role was reduced to providing advice to the two processes. No process for determining future use or categorization for state forests in the rest of Victoria had been announced at the time of writing.

The first process was the Eminent Panel for Community Engagement, announced in 2021 to provide recommendations on the future use of state forest areas in the Central Highlands and Immediate Protection Areas. In August 2022, the Eminent Panel for Community Engagement [25] completed its “Future Use and Management of Mirboo North and Strathbogie Ranges Immediate Protection Areas” and focused its work on the future use of state forests in the Central Highlands (Figure 2) with consultation closing in July 2024. The Eminent Panel commissioned VEAC to prepare an “Assessment of the values of state forests in the Central Highlands” [26] to help inform the process. At the time of writing, no recommendations on future land use have been made in this specific area.

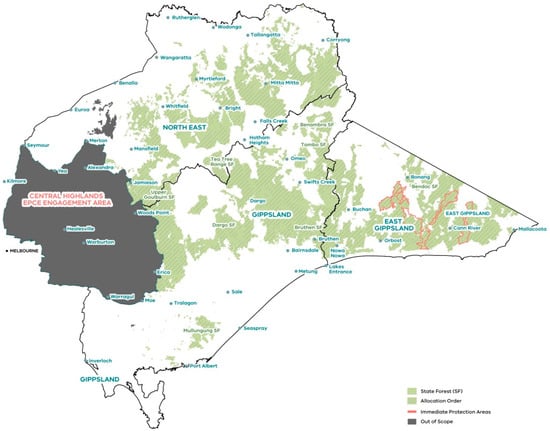

The second process was the Great Outdoors Taskforce announced on 1 April 2024 and covering the remainder of eastern Victoria (Figure 3). Public consultation was undertaken by the Taskforce between November 2024 and January 2025 with a final report expected in June 2025 [27]. Public meetings were held mostly in Victoria’s regional areas, with the 5.5 million people in the capital city Melbourne (80% of the population) only invited to make written submissions over the Christmas–New Year period.

Figure 3.

Study area for consultation on future uses of state forests in eastern Victoria by the Great Outdoors Taskforce (green areas; dark gray areas = Central Highlands Eminent Panel for Community Engagement (EPCE) area (source: [28]).

Figure 2.

Study area of Central Highlands under consideration by the Eminent Panel for Community Engagement (source: [28]).

The opportunity to expand the protected area estate was clearly acknowledged when the creation of what would become the Great Outdoors Taskforce was announced by Premier Daniel Andrews in his press release on 23 May 2023: “The Government will establish an advisory panel to consider and make recommendations to Government on the areas of our forests that qualify for protection as National Parks…” [24]. It was reinforced by Minister for Environment Steve Dimopoulos’ press release on 1 April 2024: “The Taskforce will also explore which areas need to be protected to safeguard threatened species, areas that qualify for protection as National Parks…” [29]. The terms of reference for the Great Outdoors Taskforce also clearly specify this important opportunity: “Identifies priority areas for reservation change, including state forest areas: i. that could be declared as national park or another park category under the National Parks Act 1975” [30].

However, in a press release announcing the commencement of further consultation by the Great Outdoors Taskforce on 19 November 2024, the Victorian Minister for Environment Steve Dimopoulos stated “The [Great Outdoors] Taskforce will not be making any recommendation for large-scale changes to land tenure” [31]. Further, the link from the press release to the Environment Department’s website stated “The Taskforce knows that accessing our forests for recreation and tourism and improving our biodiversity and conservation efforts can go hand in hand, and planning for these shared objectives can usher in a new era of state forest management. Because of this, the Taskforce will not be making any recommendation for large-scale changes to land tenure, including not creating any new National Parks. Instead, this Taskforce will actively focus on how this land can be managed responsibly for the future enjoyment and benefit of all Victorians” [27] [emphasis was bolded on the webpage].

No rationale was provided for this change in policy, but in public consultation meetings, it was clarified that “expanding existing national parks” would be contemplated. The change in position may in part be based on a perception or misconception that national parks overly restrict some recreational uses. Misunderstanding or misinformation on the activities allowed (or not allowed) in national parks has been a feature of opposition to new national parks as part of these processes [32,33,34] (Figure 4), as it has in previous processes proposing new protected areas in Victoria [35].

Figure 4.

Screenshot of Australian Broadcasting Corporation [32] news story on protests against potential new national parks in Victoria’s state forest. The signs incorrectly suggest national parks create increased restrictions on activities such as 4-wheel (4 × 4) driving and trail (dirt) bike access over current use in state forest.

Although national parks do restrict some uses, such as mining and dog walking, creating a comprehensive, adequate, and representative (CAR) reserve system would still leave much of the state forest available for these activities. Likewise, achieving a CAR protected area estate could be achieved by a variety of protected area categories such as nature conservation reserves and conservation parks, not simply national parks. Although there might be a temptation to consider state forests as “other effective area-based conservation measures” (OECMs) due to the cessation of logging, it is unlikely that they would qualify based on the lack of clarity on future management, the longevity of that management, and the need to demonstrate effective and long-term biodiversity conservation outcomes (e.g., [36,37]).

4. Principles for Increasing the Protected Area Estate in Victoria’s State Forests

Based on (a) international targets under the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, (b) Australian national policies, and (c) long-standing Victorian science-based assessment processes for establishing protected area networks, there are a number of principles that should be followed in reviewing state forests across Victoria. Drawing on strong scientific evidence, socio-economic assessments, and a robust public consultation process, which have been hallmarks of the Victorian approach to the public land assessment process in the past (e.g., [13]), adherence to these principles below will be important for Victoria to meet its own conservation policy commitments, contribute to Australia’s national 30 × 30 commitments, and thus the global 30 × 30 target.

4.1. Adherence to Principles of Comprehensiveness, Adequacy, and Representativeness (CAR)

Nationally agreed principles for establishing protected area networks in a comprehensive manner are embedded in Australia’s National Forest Policy Statement and the related Nationally Agreed Criteria for the Establishment of a Comprehensive, Adequate, and Representative Reserve System for Forests in Australia (the JANIS criteria) [6], Australia’s Strategy for National Reserve System 2009–2030 [4], VEAC’s obligations under the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council Act 2001, and Protecting Victoria’s Environment—Biodiversity 2037 [22]. The current protected area system in Victoria’s forests does not meet CAR principles. The CAR reserve system is based on three principles:

- Including the full range of vegetation communities (comprehensive);

- Ensuring the level of reservation is large enough to maintain species diversity (adequate);

- Conserving the diversity within each vegetation community, including genetic diversity (representative).

The “JANIS” criteria set targets for the protection of ecosystems:

- 15% of the pre-1750 distribution of each forest type;

- 60% of the existing distribution of each forest type if vulnerable;

- 60% of the existing old-growth forest;

- 90%, or more, of high-quality wilderness forests;

- All remaining occurrences (100%) of rare and endangered forest ecosystems including rare old-growth.

The JANIS criteria should be applied within a biogeographic regional framework based upon Australia’s bioregions (Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation of Australia; [38]). It should be noted that the JANIS criteria were developed in 1997 when there were not globally agreed upon protection targets. Under the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, the global target is at least 30% reservation. Australia has committed to this target at the national level [3].

4.2. Increasing Connectivity

Having a well-connected protected area system is a requirement for Australia as part of its obligations under Target 3 of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework [1]. Increasing the connectivity of conservation lands has also been a feature of policy and programs at the national and state levels (e.g., [39,40]). Due to past logging practices and bushfires, connectivity in many parts of the public forest estate has been compromised [41] and needs to be restored. This is increasingly critical with climate change [42]. There are significant opportunities to ensure the current protected area estate in Victoria’s forests has improved connectivity through the expansion and connection of existing protected areas. State forest, particularly in the east of the state (Figure 1 and Figure 5), is the main land use category separating existing protected areas. Thus, the cessation of logging offers important new opportunities to increase the linkages and connectivity between existing protected areas. This would complement efforts to improve connectivity between public and private land in more fragmented parts of Victoria [43].

4.3. Areas of Particular Importance for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functions and Services

Another requirement of Target 3 of the Global Biodiversity Framework is the need to include areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services in systems of protected areas [1]. These areas would include old-growth forests, refugia, important habitat for threatened or restricted range species (e.g., [44]), and key areas for water and carbon storage (e.g., [45]).

4.4. Improving Reserve Configuration and Design

The design and configuration of the existing protected area system in Victoria’s forests have been influenced by past compromises with competing land uses, particularly timber extraction, and in many cases do not represent logical boundaries for the ecological values they aim to protect nor for park managers or users of public land to comply with. Reviewing future uses and designations in state forests provides the opportunity to resolve these boundary issues.

4.5. Opportunities to Upgrade Special Protection Zones and Immediate Protection Areas in State Forests to Protected Areas

The JANIS criteria were a key driver of land use allocation outcomes in Regional Forest Agreements across Australia [46]. In addition to setting percent targets for ecosystem protection, the JANIS criteria [6] were also explicit about the type of protection required, i.e., “All reasonable effort should be made to provide for biodiversity and old-growth forest conservation and wilderness in the Dedicated Reserve system on public land. However, where it is demonstrated that it is not possible or practicable to meet the criteria in the Dedicated Reserve system, other approaches will be required. For example, conservation zones in approved forest management plans…” (emphasis added).

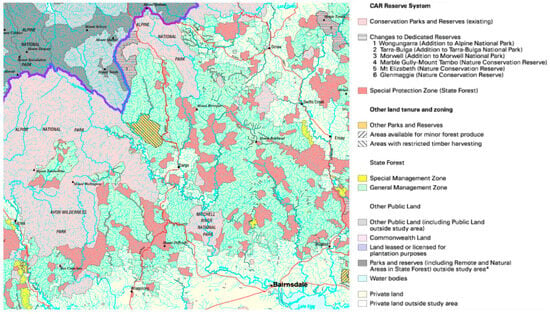

Around 92 percent of the “reserves” created under all the Victorian RFAs on or from state forests were informal and non-legislated reserves, specifically Special Protection Zones (SPZs) in state forests (Figure 5). Only 8 percent of the reserves created as part of the Victorian RFAs were “dedicated reserves” (i.e., protected areas such as national parks and nature conservation reserves) [47]. In the Central Highlands RFA, no new dedicated reserves were created [48] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Additions to the protected area estate (dedicated reserves) in each Victorian Regional Forest Agreement. Reserve names relevant at the time of the regional forest agreement (sources: [48,49,50,51,52]).

Figure 5.

Extract from the 2000 Gippsland Regional Forest Agreement showing that the majority of new “reserves” were informal Special Protection Zones, at odds with the requirements of the JANIS criteria (source: [49]).

The RFAs in Victoria did not provide a rationale to justify why it was “not possible or practicable” to declare the majority of areas that were identified as SPZs as dedicated reserves, and indeed, the vast majority could have been included. This was clearly in contravention of the JANIS criteria and the National Forest Policy Statement [53]. Victoria was the only RFA state not to have declared the majority of its reserve additions as dedicated reserves. SPZs are not considered protected areas under Victorian policy (as per [21,22]), do not have long-term security, and can allow activities inconsistent with nature conservation (e.g., grazing by stock). Recommending the declaration of the majority of SPZs to dedicated protected areas should be a high priority to ensure Victoria complies with the Nationally Agreed Criteria for the Establishment of a Comprehensive, Adequate, and Representative Reserve System for Forests in Australia.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the cessation of timber harvesting, as well as consultation processes (albeit limited and restricted) to review parts of Victoria’s state forest estate, presents a significant opportunity to expand the protected area estate in line with state, national, and international commitments and obligations. Victoria has committed to playing its part in creating a comprehensive, adequate, and representative protected area system that covers 30% of Australia by 2030 [2,3], a target strongly supported by the Australian general public [54]. With only 17% of Victoria’s land currently protected, by not playing its part, Victoria is in effect expecting other Australian states and territories to make up the shortfall in their jurisdictions. Additionally, Victoria should fulfill its obligations under the National Forest Policy Statement and JANIS criteria and create a dedicated protected area estate on forested public land. The cessation of logging does not alleviate its requirements under the JANIS criteria to establish a comprehensive, adequate, and representative protected area system in the forest estate. Victoria has the science and institutions (e.g., the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council) to develop a protected area system to fulfill its state and national commitments; it now needs the political will.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.F. and G.W.; writing—original draft preparation J.A.F. and G.W.; writing—review and editing, J.A.F. and G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank three reviewers and the editor for helpful comments that improved this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Convention on Biological Diversity. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, 15th Meeting of the Conference of Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, CBD/COP/15/L25. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-final-text-kunming-montreal-gbf-221222 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Environment Ministers. Environment Ministers Meeting—21 October 2022 Agreed Communiqué. 2022. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/emm-communique-21-oct-2022.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Australian Government. Australia’s Strategy for Nature: 2024–2030 Australia’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- NRMMC. Australia’s Strategy for the National Reserve System 2009–2030; Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Achieving 30 by 30 on Land: National Roadmap for Protecting and Conserving 30% of Australia’s Land by 2030; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- JANIS. Nationally Agreed Criteria for the Establishment of a Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative Reserve System for Forests in Australia; Joint ANZECC (Australia and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council)/MCFFA (Ministerial Council on Forestry, Fisheries and Aquaculture) NFPS (National Forest Policy Statement) Implementation Subcommittee: Canberra, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, J.; Picone, A.; Partridge, T.; Cornish, M. Protecting Australia’s Nature: Pathways to Protecting 30 per cent of Land by 2030; The Nature Conservancy, WWF-Australia, the Australian Land Conservation Alliance and the Pew Charitable Trusts: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.F.J.; Fitzsimons, J.; Sattler, P. Building Nature’s Safety Net 2014: A Decade of Protected Area Achievements in Australia; WWF-Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wescott, G.C. Australia’s distinctive national parks system. Environ. Conserv. 1991, 18, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, A.J.; McDonald, J. Environmental issues in Australia. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2014, 39, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wescott, G. Victoria’s national park system: Can the transition from quantity of parks to quality of management be successful? Aust. J. Environ. Manag. 1995, 2, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clode, D. As if for a Thousand Years: A History of Victoria’s Land Conservation and Environment Conservation Councils; Victorian Environmental Assessment Council: Melbourne, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, B.; Fitzsimons, J.A.; Gormly, R. Strategic public land use assessment and planning in Victoria, Australia: Four decades of trailblazing but where to from here? Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wescott, G. The long and winding road: The development of a comprehensive, adequate and representative system of highly protected marine protected areas in Victoria, Australia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2006, 49, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wescott, G. Victoria’s chequered history in the development and implementation of marine protected areas. In Big, Bold and Blue: Lessons from Australia’s Marine Protected Areas; Fitzsimons, J., Wescott, G., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2016; pp. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, J.; Wescott, G. The role and contribution of private land in Victoria to biodiversity conservation and the protected area system. Aust. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 8, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, J.A.; Ashe, C. Some recent strategic additions to Victoria’s protected area system 1997–2002. Victorian Nat. 2003, 120, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, J.A.; Williams, C.; Walsh, V.; FitzSimons, P.; U’Ren, G. Ecological attributes of strategic land acquisitions for addition to Victoria’s public protected area estate (2006–2007). Victorian Nat. 2008, 125, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L. Post-colonial appropriations of the colonial at Budj Bim, Western Victoria, Australia. In Indigenous Places and Colonial Spaces: The Politics of Intertwined Relations; Gombay, N., Palomino-Schalscha, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafi, S.M.; White, M.; Burgman, M. Implementing comprehensiveness, adequacy and representativeness criteria (CAR) to indicate gaps in an existing reserve system: A case study from Victoria, Australia. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VEAC. Statewide Assessment of Public Land Discussion Paper for Public Comment; Victorian Environmental Assessment Council: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. Protecting Victoria’s Environment—Biodiversity 2037; Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, D.; Securing the Future for Forestry Industry Workers. Media Release the Hon Daniel Andrews MP, Premier, 7 November 2019. Available online: https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/securing-the-future-for-forestry-industry-workers-0 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Andrews, D.; Delivering Certainty for Timber Workers. Media Release the Hon Daniel Andrews MP, Premier 23 May 2023. Available online: https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-05/230523-Delivering-Certainty-For-Timber-Workers.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Eminent Panel for Community Engagement. Future Use and Management of Mirboo North and Strathbogie Ranges Immediate Protection Areas Final Report; State of Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- VEAC. Assessment of the Values of State Forests in the Central Highlands Interim Report; Victorian Environmental Assessment Council: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Great Outdoors Taskforce. Great Outdoors Taskforce. 2024. Available online: https://www.deeca.vic.gov.au/futureforests/future-forests/great-outdoors-taskforce (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. Future of State Forests: The Future of Victoria’s State Forests. 2024. Available online: https://www.deeca.vic.gov.au/futureforests/future-forests (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Dimopoulos, S.; Have Your Say on the Future of Our Forests. Media Release. Steve Dimopoulos MP, Minister for Environment. 1 April 2024. Available online: https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/240401-Have-Your-Say-On-The-Future-Of-Our-Forests.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Dimopoulos, S. Great Outdoors Taskforce Terms of Reference. 2024. Available online: https://www.deeca.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/729733/GOT-Terms-of-Reference.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Dimopoulos, S.; Great Outdoors Taskforce Consultation Opens. Steve Dimopoulos MP, Minister for Environment. 19 November 2024. Available online: https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-11/241119-Great-Outdoors-Taskforce-Consultation-Opens.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Hundreds rally against plan to establish more national parks in Victoria. ABC News, 26 May 2024. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-26/national-parks-state-forest-rally/103894648 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kolovos, B.; A ‘scare campaign’ over national parks? The fight over the future of Victoria’s forests. The Guardian, 27 June 2024. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/article/2024/jul/28/victoria-great-forest-national-park-plan-disinformation (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Hall, E.; How our national parks got dragged into the culture wars. The Age, 7 February 2025. Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/how-our-national-parks-got-dragged-into-the-culture-wars-20250203-p5l95j.html (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Miles, D.; Victorian government creates three new national parks, but not everyone’s happy. ABC News, 24 June 2021. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-24/new-national-parks-for-victoria/100238132 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Fitzsimons, J.A.; Partridge, T.; Keen, R. Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs) in Australia: Key considerations for assessment and implementation. Conservation 2024, 4, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, J.; Stolton, S.; Dudley, N.; Mitchell, B. Clarifying ‘long-term’ for protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs): Why only 25 years of ‘intent’ does not qualify. Parks 2024, 30, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Australia’s Bioregions (IBRA). Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/land/nrs/science/ibra (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Pulsford, I.; Howling, G.; Dunn, R.; Crane, R. The Great Eastern Ranges Initiative: A continental-scale lifeline connecting people and nature. In Linking Australia’s Landscapes: Lessons and Opportunities from Large-Scale Conservation Networks; Fitzsimons, J., Pulsford, I., Wescott, G., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2013; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Zammit, C. Scaling up: The policy case for connectivity conservation and the development of Australia’s National Wildlife Corridors Plan. In Linking Australia’s Landscapes: Lessons and Opportunities from Large-Scale Conservation Networks; Fitzsimons, J., Pulsford, I., Wescott, G., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2013; pp. 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Temporal fragmentation of a critically endangered forest ecosystem. Austral Ecol. 2020, 45, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansergh, I.; Cheal, D.; Fitzsimons, J.A. Future landscapes in south-eastern Australia: The role of protected areas and biolinks in adaptation to climate change. Biodiversity 2008, 9, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, J.; Pulsford, I.; Wescott, G. (Eds.) Linking Australia’s Landscapes: Lessons and Opportunities from Large-Scale Conservation Networks; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer, D.B. Flawed forest policy: Flawed Regional Forest Agreements. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, H.; Vardon, M.; Stein, J.A.; Stein, J.L.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Ecosystem accounts define explicit and spatial trade-offs for managing natural resources. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillier, J. Fighting over the forests: Environmental conflict and decision-making capacity in forest planning processes. Aust. Geogr. Stud. 2003, 41, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VNPA. Victoria’s Regional Forest Agreements: The Failures and the Problems with Renewing for Another 20 Years; Victorian National Parks Association: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://www.deeca.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/438602/VNPA-Submission-2.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- State of Victoria; Commonwealth of Australia. Central Highlands Regional Forest Agreement; State of Victoria and Commonwealth of Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia; State of Victoria. Gippsland Regional Forest Agreement; Commonwealth of Australia & State of Victoria: Canberra, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia; State of Victoria. East Gippsland Regional Forest Agreement; Commonwealth of Australia & State of Victoria: Canberra, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia; State of Victoria. Noth East Regional Forest Agreement; Commonwealth of Australia & State of Victoria: Canberra, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia; State of Victoria. West Victoria Regional Forest Agreement; Commonwealth of Australia & State of Victoria: Canberra, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. National Forest Policy Statement: A New Focus for Australia’s Forests; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons, J.A.; Garrison, K.; Finnegan, B.; Luby, I. The 30 × 30 protection target: Attitudes of residents from seven countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).