Abstract

Pilot policy relating to the building of rental houses on collectively owned land is crucial for forming integrated urban and rural construction land markets and promoting rural revitalization. However, inequalities in the distribution of benefits may impede pilot projects. This paper employs a mixed-methods approach combining social network analysis, case study, and game theory to analyze the strategic decisions of key stakeholders in pilot policy, aiming to identify challenges and barriers to its implementation. Local governments, rural collective economic organizations, and enterprises are defined as the three key stakeholders, according to social network analysis. The findings suggest that the successful implementation of pilot policy requires cooperation among at least two stakeholders. Key factors influencing stakeholders include policy risk, market risk, the local government’s stance on the pilot policy, communication, coordination costs, the capabilities of collective economic organizations, and expected benefits, all of which can lead to conflicts among stakeholders. Strategies to support equilibrium of the interests of all parties are proposed, in order to promote cooperation among these three core categories of stakeholders.

1. Introduction

The development of affordable rental housing is critical for fostering social equity and inclusive urban growth [1]. However, given real estate’s historical role as a pillar of China’s economic expansion, local governments and private enterprises have lacked incentives to prioritize rental housing, resulting in systemic shortages, income-based disparities in housing, and substandard living conditions [2,3,4,5]. According to the 2020 National Population Census, China’s floating population reached 376 million—a 70.14% increase from 2010—while the rent-to-price ratio for developer-held properties fell to 1.3%, down 0.5 percentage points over the same period. This widening gap between increasing housing demand and slow development of the rental market has undermined the national goal of “ensure people’s access to housing”. To address this, China has initiated reforms to integrate housing rental and ownership systems.

Land supply persists as a critical bottleneck constraining the scalability of rental housing markets in China [6]. In July 2017, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ministry of Housing and Urban–=Rural Development jointly implemented the Collectively Owned Construction Land Rental Housing Pilot Policy (BRHCOCL). This landmark reform authorized 13 pilot cities (including Beijing and Shanghai) to develop affordable rental housing on rural collective construction land without consuming municipal construction land quotas.

Prior to this institutional reform, China’s land governance operated under two restrictive mechanisms: The Land Use Regulation System mandated strict control over construction land expansion and the Urban–Rural Dual Construction Land Market System legally segregated urban and rural land transactions [7,8,9]. Under this dual framework, all rental housing construction—whether utilizing state-owned land or rural construction land—invariably consumed newly allocated construction land quotas [10]. This regulatory environment created direct competition for limited land resource between commercial housing development and the construction of rental housing, consequently constricting the supply and availability of land for expansion of the rental market [11,12].

The policy’s theoretical advantage stems from its reclassification of rural collective construction land as existing construction land stock. This strategic categorization allows rental housing to be developed on such land parcels without depleting quotas for new construction land, thereby technically increasing the potential land supply for rental housing [13]. However, this market intervention has disrupted the entrenched distribution of interest within China’s dual land market system. Despite the pilot program expanding to 18 cities by 2019, empirical studies have demonstrated BRHCOCL’s limited success in alleviating housing shortages within megacities [6,13,14]. Consequently, systematic identification of core stakeholders and rigorous analysis of their strategic decision-making patterns carry significant practical implications for advancing reform of China’s rental housing policy. The current investigation provides essential theoretical guidance for resolving implementation barriers and optimizing institutional design in the context of ongoing transformation of the housing system.

Existing research on the implementation of the BRHCOCL pilot policy has predominantly focused on operational challenges such as institutional barriers [15], conflicts relating to the distribution of benefits [16], and risk management issues [17], alongside documenting grassroots innovations in policy execution [18,19,20]. While these studies provide valuable insights into systemic obstacles and localized adaptations, they critical gaps remain in terms of stakeholder-centric analyses. Specifically, few studies have systematically identified the key actors involved in BRHCOCL implementation or examined their roles in shaping policy outcomes [21,22]. This oversight is particularly consequential given the inherent complexity of China’s urban–rural land governance, where fragmented stakeholder interests often derail coordinated action. For instance, while prior work acknowledged the importance of institutional frameworks and financial mechanisms, it largely neglected the role of inter-stakeholder coordination costs—a factor that directly impacts the feasibility of multi-party collaborations. Furthermore, the absence of granular analyses of stakeholder motivations and trade-offs limits policymakers’ ability to design incentive-compatible governance structures. These gaps collectively constrain the development of evidence-based strategies for scaling BRHCOCL initiatives nationally.

Methodologically, BRHCOCL research remains divided between qualitative case studies and quantitative econometric models, with limited integration of mixed-methods approaches [16]. Social network analysis (SNA) has been sporadically applied to map stakeholder relationships [22], but its potential for informing actor selection in game-theoretic models remains underexplored. Conversely, evolutionary game theory (EGT)—a well-established framework for modeling strategic interactions in land policy—has yet to be systematically adapted to BRHCOCL contexts [23,24,25,26,27]. This disjuncture is problematic because BRHCOCL implementation inherently involves dynamic, nonlinear interactions among governments, collective economic organizations, and enterprises, where strategic choices evolve in response to shifting payoffs and risk perceptions. The tripartite nature of these interactions creates path-dependent outcomes that conventional static analyses cannot capture. For example, local governments may initially prioritize fiscal gains from land conversions but shift toward social welfare objectives under public pressure. Only through EGT can such behavioral dynamics be rigorously modeled; this is particularly the case when identifying evolutionary stable strategies (ESS) that predict long-term policy trajectories [28].

This study bridges these theoretical and methodological gaps through an innovative synthesis of stakeholder theory and EGT, augmented by mixed-methods triangulation. By employing SNA to identify core stakeholders and using case studies to obtain the ground-truth model parameters, we establish a replicable framework for analyzing land policy implementation. Our investigation addresses three pivotal questions: First, who constitutes the core stakeholder ecosystem in BRHCOCL implementation, and how do their interests align or conflict? Second, what factors determine the success or failure of BRHCOCL execution? Third, under what conditions can stable, equitable governance regimes emerge from the strategic interplay of key actors?

This research makes a dual contribution to theory and practice. Theoretically, it advances the scholarship on land policy by formalizing coordination costs as a critical variable in multi-stakeholder governance models. By quantifying how transaction costs between local governments, collectives, and enterprises affect policy adherence, we challenge the prevailing assumption that legal-institutional reforms alone can ensure BRHCOCL success. Practically, the mixed-methods approach demonstrates how SNA-derived stakeholder networks can inform the selection of EGT actors, while empirical case data enhance model realism [29]. Mixed methods ensure that simulation outcomes reflect on-the-ground economic realities rather than abstract theoretical constructs.

2. Methodology

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Stakeholder Identification Methods

Policy implementation inherently involves collaboration and negotiation among stakeholders, where actors articulate their demands and values through formal and informal channels, refine strategies through mutual learning, and ultimately reach a stable state. Stakeholder identification is a fundamental step in analyzing conflicts among interest groups. Identifying core stakeholders, those occupying advantageous positions, is crucial for understanding key conflicts and influencing factors and for facilitating policy optimization. The existing research on stakeholder identification methods remains limited, with literature analysis and SNA being the most commonly used approaches [22]. This study systemically integrates both qualitative and quantitative methods, using literature analysis and social network analysis (SNA) to identify key stakeholders in the pilot policy of BRHCOCL. The specific steps were as follows: (1) a review of the literature, in order to identify potential stakeholders based on policy documents and case studies. (2) SNA to construct a stakeholder network using UCINET 6.0. Social actors operate within formal and informal relationship networks, where their behaviors and outcomes are shaped by their structural positions. Core stakeholders possess greater bargaining power, influence, and visibility in resource exchanges [14], and SNA offers a rigorous framework for identifying such actors; (3) core stakeholder identification to determine key actors based on network centrality metrics.

2.1.2. The Evolutionary Game Model and Its Applicability

Unlike traditional game theory, evolutionary game theory does not require participants to be fully rational, nor does it assume complete information conditions. It combines game-theoretic analysis with the analysis of dynamic evolutionary processes. The fundamental idea of evolutionary game theory is that, due to limited rationality, players cannot identify optimal strategies and equilibrium points from the outset. Instead, they adjust and improve their strategies through mutual learning, eventually evolving over time towards a stable combination of strategies known as an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). Methodologically, evolutionary game theory defines a dynamic equilibrium represented by replicator dynamic equations that describe how participants gradually converge to a stable state.

The purpose of exploring evolutionary game theory is to understand the dynamic processes of group evolution and to explain why and how a group reaches a particular state. Factors influencing group changes exhibit both a degree of randomness and perturbation as well as regularities that emerge through the selection mechanisms present in the evolutionary process.

Throughout the development of the pilot policy for building rental houses on collectively owned land, the behavioral choices of stakeholders have been integral to the evolution of this policy. In an uncertain political and economic environment, relevant stakeholders cannot identify optimal strategies from the outset; instead, they continuously adjust and improve their strategies through mutual learning and imitation, ultimately determining a particular strategy through selection and mutation, thereby revealing certain regularities.

Specifically, the core stakeholders discussed in this paper exhibit limited rationality and do not possess complete information. For example, enterprises cannot fully anticipate the expected returns for collective economic organizations following the development of collectively owned construction land, while neither collective economic organizations nor enterprises can predict the extent of the policy subsidies that local governments are willing to invest to promote the implementation of BRHCOCL policy. The strategic choices of individual stakeholders are influenced by the choices of others, and a stakeholder’s strategy in one region may also be affected by the choices of similar stakeholders in other regions. Inter-stakeholder learning and imitation ultimately lead to cooperative or non-cooperative outcomes in policy execution.

2.2. Stakeholder Identification

2.2.1. Literature-Based Stakeholder Identification

Stakeholders in the pilot policy of BRHCOCL include individuals, groups, and organizations that may be positively or negatively affected by policy implementation. Given the relatively recent development of BRHCOCL projects in China and their frequent inclusion within public rental housing policy studies, the current study first identified stakeholders from both policy contexts. These stakeholders were then refined through case-specific adjustments (merging, removing, or adding entities) to ensure an accurate representation of key actors in the BRHCOCL policy framework.

Table 1 lists stakeholders involved in public rental housing or BRHCOCL policies, identified through a review of the literature. Key stakeholders include government, public, media, academia, tenants, financial institutions, construction/operation firms (designers, employees, subcontractors, suppliers, service providers, insurance companies), and NGOs. A defining feature of BRHCOCL projects is their reliance on collective-owned land supplied by rural collectives, making rural collective economic organizations and farmers critical stakeholders. Field studies and case analyses (e.g., the Beijing HuaRun YouChao International Apartment project, jointly developed by HuaRun Properties and PingAn Real Estate on land provided by Baotai Village) further revealed that BRHCOCL planning often targets enterprises with concentrated rental demand. For instance, 75% of tenants in the cited project are employees of nearby high-tech manufacturing firms. Thus, neighboring enterprises with rental needs (hereafter “peripheral enterprises”) are also stakeholders. In total, 11 stakeholder groups were identified: government, public, media, academia, tenants, financial institutions, collective economic organizations, farmers, construction/operation firms, NGOs, and peripheral enterprises.

Table 1.

Stakeholders identified from the literature.

2.2.2. Identifying Core Stakeholders via Social Network Analysis (SNA)

Building on the stakeholder list derived in Section 2.2.1, we conducted face-to-face interviews with public housing experts and policymakers to assess relational strength among stakeholders. These data were used to construct an adjacency matrix, which was modeled in UCINET 6.0. Core stakeholders were identified through network visualization and centrality metrics (degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality). The following were considered:

- (1)

- Relational strength, reflecting the intensity, trust, reciprocity, and frequency of interactions between actors. Following the stated methodology, we operationalized this construct using five dimensions: coordination, contractual agreements, information exchange, performance incentives, and directives. Interviews with 12 BRHCOCL participants (e.g., village committee members, project managers, district officials, scholars) quantified pairwise relational strength across the 11 stakeholder groups. Participants scored relationships on a 0–5 scale (0 = no interaction; 5 = intensive collaboration), irrespective of perceived importance. Scores were aggregated into an adjacency matrix (See Table 2) for SNA modeling.

Table 2. BRHCOCL project stakeholder relationship strength adjacency matrix.

Table 2. BRHCOCL project stakeholder relationship strength adjacency matrix.

- (2)

- Centrality Measures, assessed via centrality analysis conducted in UCINET 6.0 using the adjacency matrix to quantitatively compare node importance. A higher degree of centrality (See Table 3) indicates greater node significance within the network. As shown, construction/operation enterprises, governments, collective economic organizations, farmers, and tenants exhibited the highest degree of centrality scores, underscoring their pivotal roles in BRHCOCL projects.

Table 3. Stakeholders’ Centrality.

Table 3. Stakeholders’ Centrality.

- (3)

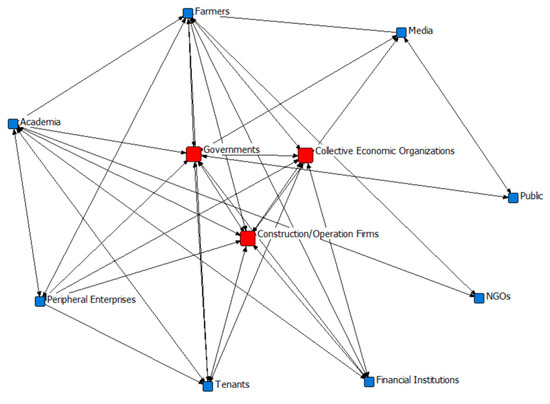

- The social network model, whereby the stakeholder network was visualized via NetDraw (Figure 1), confirming that local governments, rural collectives, farmers, construction/operation enterprises, and tenant groups maintained denser and stronger ties with other stakeholders—consistented with centrality results. Peripheral actors (e.g., the public, media, academia, financiers, and neighboring firms) demonstrated weaker linkages and marginal influence on policy implementation.

Figure 1. Social Network Modeling of BRHCOCL Project Stakeholders.

Figure 1. Social Network Modeling of BRHCOCL Project Stakeholders.

Combining logical reasoning and the literature review, we identified 11 BRHCOCL stakeholders. SNA quantified the dominance of five core groups: local governments, rural collectives, farmers, construction/operational enterprises, and tenants. Among these, governments, collective economic organizations, and construction/operational enterprises wielded the greatest influence over policy execution.

2.3. Analysis of Stakeholders’ Interests

2.3.1. Government

In China, the government bears significant responsibilities for promoting economic and social development and managing social affairs according to the decisions and deployments of the Party and the state. This responsibility spans five administrative levels: central, provincial, municipal, district (county), and township (town), and can be divided into central and local governments. The central government is the policymaker, while local governments are the promoters and executors of policies. The interests and demands of local governments significantly influence the outcomes of policy implementation. Some scholars argue that the interests of local government encompass both the self-interests of local government organizations and the interests of enterprises and the public within their jurisdictions. Local government interests include political and economic benefits; political interests relate to political promotion, the accountability of officials, and local stability, while economic interests mainly refer to maximizing fiscal revenues [14]. In the execution of BRHCOCL projects, the multiple interests and demands of local governments can be summarized into the following three aspects.

First, local governments are responsible for ensuring the supply of affordable housing and optimizing the structure of the local housing rental and sales market. Under the central government’s policies of ‘housing is for living in, not for speculation’ and ‘integrating rental and sales’, it is the duty of local governments to promote the construction of affordable rental housing, optimize the local rental and sales market structure, and ensure the healthy, stable, and orderly development of the real estate market. Given the financial constraints faced by local governments, collaborating with collective economic organizations and enterprises to BRHCOCL can alleviate fiscal pressure on the government, fulfill the task of providing affordable rental housing, and achieve social benefits.

Second, local governments seek to gain land appreciation benefits and increase local fiscal revenues. For the normal operation of national governance, taxation is fundamental, and finance is its lifeblood [16]. In the implementation of BRHCOCL policy, the economic interests of local governments include exploring tax-based participation to obtain land appreciation benefits from the development and transfer of collective construction land, as well as securing central government funding for the development of the housing rental market. Local governments should also aim to provide a favorable living environment for migrant workers, young talents, and employees in industrial parks, enhancing the attractiveness of local cities, optimizing the business environment, driving investment, and increasing tax revenues.

Third, local governments aim to complete pilot tasks and gain recognition from higher authorities to accumulate political capital. In China, pilots are an important feature of reform methods and are regarded as a foundational governance mechanism [30]. From a ‘top-down’ perspective, pilots initiated by central government often include political tasks. As the executors of these pilots, local governments bear the responsibility of completing the pilot tasks. If local governments actively implement the BRHCOCL scheme and achieve good results, and if they are included in the central government’s list of pilot promotions, they can enhance the political influence of local officials and accumulate capital for political advancement.

2.3.2. Construction/Operational Enterprises

Construction/operational enterprises (referred to as ‘enterprises’) are the main participants in market economic activities. They include socio-economic organizations that operate independently, assume responsibility for their profits and losses, and provide goods or services to the market for profit, utilizing various production factors (such as land, labor, capital, technology, and entrepreneurship). In the implementation of the pilot policy of BRHCOCL, most of the investment, construction, and operational management of the pilot projects relies heavily on the participation of such enterprises. The participating enterprises in these pilot projects include state-owned enterprises, such as China Resources Land and local investment companies, as well as leading private real estate companies like Vanke and Longfor. The primary interests of enterprises participating in the BRHCOCL projects mainly include reducing transaction costs and obtaining long-term benefits.

First, it is essential to reasonably determine the development model to reduce land and communication costs, thereby achieving the minimization of investment costs. According to the ‘Pilot Program’, 18 pilot cities have embarked on differentiated explorations, leading to the formation of various cooperation models between collective economic organizations and enterprises. Different cooperation models result in varying investment costs for the construction enterprises. In the independent development model, the completed properties are leased in their entirety to enterprises for operational management, with the operating enterprises paying a certain percentage of rent to the collective economic organizations each year. This model clarifies the rights and profit distribution between the collective economic organizations and enterprises, does not involve land costs, and incurs lower transaction costs. The cooperative development model involves assessment of the market price of collective construction land and the equity ratio between collective economic organizations and enterprises, resulting in higher costs for communication and negotiation. In the transfer development model, enterprises must pay the land transfer fee upfront in a lump sum, leading to higher initial costs. In the promotion of BRHCOCL projects, regardless of the chosen development model, the primary interest of enterprises participating in construction is the minimization of investment costs. The return on investment is quite low for developers constructing housing for commercial rent, with most annual yields between only 1% and 2%. In this context, utilizing collective construction land with relatively lower land prices can achieve an annual rate of return on investment exceeding 5% under marketized rental conditions [31].

Second, it is crucial to tapping into the rental housing market, build long-term rental brands, accumulate operational experience, and achieve long-term benefits. Under the policy backdrop of ‘housing is for living in, not for speculation’ and ‘integrating rental and sales’, China’s rental housing market is rapidly developing, with affordable rental and long-term rental housing representing new opportunities and challenges in the real estate market. Historically, China’s real estate development enterprises have been accustomed to the high-profit “development–sales” model since the marketization of self-owned housing, leading to a rough and rapid development style that lacks the capability and patience for long-term operational management of rental housing projects.

Regarding the current status of BRHCOCL projects, brands such as China Resources Land’s ‘Youchao’, Vanke’s ‘Vanke Apartment’, and Longfor’s ‘Longfor Apartment’ are actively participating in the development and management of these projects. For instance, Vanke Apartment’s slogan is ‘Providing a warm home for aspiring youth on the move’, highlighting the determination of leading real estate companies to capture the centralized rental housing market.

Looking back at history and analyzing the current situation, construction and operational enterprises working on these projects aim to accumulate operational experience in rental housing, enhance their brand image, achieve long-term benefits, and promote sustainable development. However, currently, only leading real estate companies possess the financial strength and risk resistance necessary to match this strategic vision. Furthermore, state-controlled enterprises in China, in addition to pursuing their own profits, bear significant social responsibilities due to their unique role in economic development. In BRHCOCL projects, their interests and demands include assuming political responsibilities and safeguarding the collective rights of farmers, distinguishing them from private enterprises.

2.3.3. Collective Economic Organization

According to the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Rural Collective Economic Organizations,” collective economic organizations are regional economic entities based on collective land ownership that exercise ownership rights on behalf of their members in accordance with the law. They operate under a dual-layer management system that combines family contracting with centralized and decentralized operations. Collective economic organizations are not fully market entities; rather, they are special economic organizations that assume various social functions, undertaking three basic responsibilities: managing collective assets, providing production and operational services to farmers, and supplying operational funds for villagers’ self-governing organizations.

The pilot program for BRHCOCL has opened channels for collective construction land to enter the urban rental housing market. As collective economic organizations maintain ownership of rural collective construction land, they have the responsibility to gain and distribute the appreciation benefits from this land. Therefore, one of the interest pursuits of collective economic organizations is to transform land resources into high-quality assets, obtain land appreciation income such as rental or share income, strengthen collective economic strength, and drive the development of related rural industries.

According to Chinese law, rural collective economic organizations or villagers’ committees have the right to manage collective land and obtain appreciation benefits from it. Articles 59 and 63 of the 2019 “Land Administration Law” place restrictions on the use of rural collective land and limit the trading of land use rights. While maintaining the stability of the land system and preventing chaos in land transactions, this law also reduces the profit space for collective economic organizations to dispose of collective land. The pilot policy of BRHCOCL represents a breakthrough from the original legislation, expanding the uses of collective land and enhancing the powers of collective economic organizations in managing collective land.

Any land development has an impact on the surrounding environment. The use of collective construction land for urban rental housing development will shape the villages and ecological environment on which farmers depend for their livelihoods, promote the flow of capital and labor into rural areas, incentivize the construction of basic public facilities in villages, and drive rural industrial revitalization. Therefore, the interests of rural collective economic organizations can be summarized as fully exercising their rights to use collective construction land, obtaining appreciation benefits from collective land, promoting the development of the collective economy, and facilitating the revitalization of rural industries.

Second, as representatives of farmers, collective economic organizations are tasked with safeguarding collective rights and protecting farmers’ interests when negotiating with external parties. Originating from the agricultural cooperative movement and rooted in rural social networks, rural collective economic organizations represent the unity of laborers and bear the responsibility and mission of seeking benefits for and the well-being of farmers. Since reform and opening up, these organizations have played an important role as intermediaries connecting the government, enterprises, and dispersed farmers, with strongly demanding protection for farmers and upholding collective rights.

Third, collective economic organizations aim to complete the governments’ pilot tasks and reduce the administrative management costs of autonomous operation. In the context of rural revitalization and urban–rural integration, village committees assume many administrative functions, adopting a quasi-governmental role, and they are even regarded as an extension of grassroots government hierarchy. In fact, salaried incomes and subsidies for village committee staff depend on governmental financial allocations, which effectively means that village committees act as agents of the government, particularly at the grassroots level. After the higher government designates pilot sites for BRHCOCL, the ‘quasi-administrative’ orientation of the village committees encourages them to cooperate with government pilot tasks. Additionally, like any organization, village committees and collective economic organizations have their own interests in terms of sustaining their existence and development, including the desire to cover the operational costs of their organization through the management of collective assets.

2.4. Hypothesis and Model

To simplify the analysis, this paper constructs a game model involving three core stakeholders: local governments, collective economic organizations, and enterprises, in order to explore the characteristic evolution of the decision-making behaviors of these stakeholders and manifestations of conflict between them.

2.4.1. Hypothesis and Variables

Assumption 1.

Local governments, collective economic organizations, and enterprises are all limited rational agents.

Each party in the game lacks sufficient predictions and information about the behavioral characteristics, strategy space, and payoffs of the others, making decisions under conditions of incomplete information. As a result, each party in the game cannot fully understand the action strategies of the other two parties. The players engage in multiple rounds of the game through mutual learning, trial and error, and imitation, adjusting their strategies in the process to pursue optimal payoffs.

Assumption 2.

Strategy Sets of Local Governments, Collective Economic Organizations, and Enterprises.

- (1)

- Local Governments’ Strategy Set:

Active Implementation (): This refers to local governments actively executing a series of actions, including advancing project registration and approval, selecting well-located pilot sites, providing tax reductions, constructing infrastructure, guiding collective economic organizations and enterprises to participate in the BRHCOCL policy, and being willing to carry out unified management of these houses when necessary.

Passive Implementation (): This indicates that local governments have a lackluster attitude towards promoting the BRHCOCL projects, limiting their actions to issuing notifications and site selection, with a weak commitment to implementing the pilot program and holding a negative stance.

- (2)

- Collective Economic Organizations’ Strategy Set:

Agreement (): This means that collective economic organizations agree to transfer the usage rights of collectively owned construction land or to invest in the implementation of BRHCOCL policy. If enterprises do not participate, the collective economic organizations fund the construction of the rental houses themselves.

Disagreement (): This indicates that collective economic organizations, for certain reasons, consider not using collectively owned land for the construction of building rental houses.

- (3)

- Enterprises’ Strategy Set:

Participation (): This means that enterprises respond to the call of the pilot policy or, for their long-term interests, participate in the development and management of the BRHCOCL projects.

Non-participation (): This refers to enterprises choosing not to participate in the development and operation of BRHCOCL projects, due to considerations of costs and risk.

Assumption 3.

In the course of the game, the probability that local government chooses ‘active implementation’ is , and the probability that it chooses ‘passive implementation’ is . The probability that collective economic organization chooses ‘agreement’ is , and the probability that they choose ‘disagreement’ is . The probability that enterprises choose ‘participation’ is , and the probability that they choose ‘non-participation’ is , with the constraint that , , .

Assumption 4.

Setting cost and benefit parameters for each stakeholder

When local government adopts an ‘active implementation’ strategy, collective economic organizations adopt an ‘agreement’ strategy, and enterprises adopt a ‘participation’ strategy, the benefits obtained by the local government, collective economic organization, and enterprise are denoted as , , and , respectively. If local government follows an ‘active implementation’ strategy while the collective economic organization chooses ‘disagreement’ regarding investment or the transfer of usage rights of collectively owned construction land, local government needs to communicate and coordinate with the collective economic organization, with the coordination cost denoted as . If local government adopts the ‘active implementation’ strategy and the enterprise chooses ‘non-participation’ in the implementation of BRHCOCL policy, local government will need to communicate and coordinate with the enterprise, with the coordination cost denoted as .

When the collective economic organization adopts the ‘agreement’ strategy and the enterprise chooses ‘non-participation’, the collective economic organization needs to self-fund the development and construction, with the cost denoted as . Financial subsidies available are denoted as , while the market risks and financial risks faced are denoted as Rm. When the collective economic organization adopts the ‘agreement’ strategy and the enterprise chooses ‘participation’, the construction investment and operational management costs incurred by the enterprise are denoted as . The financial subsidies that the enterprise can obtain as the developer are denoted as , and the bargaining costs incurred by both parties are denoted as . Here, the market risks and financial risks faced by the collective economic organization are denoted as (0 < n < 1) and , representing the economic risk coefficient, while the market risks and financial risks faced by the enterprise are denoted as .

If the enterprise chooses ‘participation’ while the collective economic organization chooses ‘disagreement’, the communication and coordination costs incurred by the enterprise are denoted as , and the use of collectively owned construction land is restricted. When the local government chooses the ‘passive implementation’ strategy, which does not intentionally help the enterprise and the collective economic organization to avoid the policy and legal risks of BRHCOCL projects, if the collective economic organization chooses ‘agreement’ while the enterprise chooses ‘non-participation’, the policy and legal risks faced by the collective economic organization are denoted as . When the enterprise chooses ‘participation’, the risks faced by the collective economic organization and the enterprise are denoted as (0 < m < 1) and , representing the policy risk coefficient. Given that the return cycle of building rental houses is long and the development risks are high, when the local government adopts the ‘passive implementation’ strategy, the collective economic organization adopts the ‘disagreement’ strategy, and the enterprise adopts the ‘non-participation’ strategy, the time, energy, and economic losses that can be avoided by the three parties are denoted as , , and , respectively. Table 4 shows the basic parameters and it’s meaning of evolutionary game model.

Table 4.

Basic parameters and meaning of evolutionary game model.

Based on the behavioral strategies of the local government, collective economic organizations, and enterprises, there are eight possible game combinations among the three parties: (active implementation, agreement, participation), (active implementation, agreement, non-participation), (active implementation, disagreement, participation), (active implementation, disagreement, non-participation), (passive implementation, agreement, participation), (passive implementation, agreement, non-participation), (passive implementation, disagreement, participation), and (passive implementation, disagreement, non-participation).

Based on the above assumptions, a payoff matrix for the three parties was constructed, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Three-party behavior selection and game payoff matrix.

From the behavioral choices and the game-theoretic payoff matrix for local government, collective economic organizations, and enterprises, the expected payoff functions and replication dynamics equations for the three game participants were derived. The replication dynamics equation is a core concept in evolutionary game theory. Analyzing the behavioral evolution of the game participants based on the replication dynamics equation is a common approach in evolutionary game research.

2.4.2. Expected Payoff Function and Replication Dynamics Equation

- (1)

- The expected payoff function and replication dynamics equation for local government

Let the payoff functions representing the local government’s choice of “active implementation” and “passive implementation” strategies be denoted by and , respectively, with representing the average payoff.

The expected payoff function for local government choosing the “active implementation” strategy is as follows:

The expected payoff function for local government choosing the “passive implementation” strategy is as follows:

The average expected payoff function for local government is as follows:

The replication dynamics equation for local government is as follows:

- (2)

- The expected payoff function and replication dynamics equation for the collective economic organization

Let the payoff functions representing the collective economic organization’s choice of “agreement” and “disagreement” strategies be denoted by and , respectively, with representing the average payoff.

The expected payoff function for the collective economic organization choosing the “agreement” strategy is as follows:

Then, the expected payoff function for the collective economic organization choosing the “disagreement” strategy is as follows:

The average expected payoff function of the collective economic organization is as follows:

The replication dynamics equation of the collective economic organization is as follows:

- (3)

- The expected payoff function and replication dynamics equation for the enterprise

Let the payoff functions representing the enterprise’s choice of “participation” and “non-participation” strategies be denoted by and , respectively, with representing the average payoff.

The expected payoff function for the enterprise choosing the “participation” strategy is as follows:

The expected payoff function for the enterprise choosing the “non-participation” strategy is as follows:

The average expected payoff function for the enterprise is as follows:

The replication dynamics equation for the enterprise is as follows:

By solving Equations (4), (8) and (12) simultaneously, we obtain:

Equation (13) is the dynamic equation of the game system, which represents the relationships between the various elements in the system.

3. Results

3.1. Model Solution and Stability Analysis

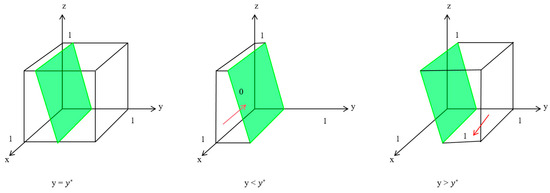

3.1.1. Stability Analysis of the Local Government’s Strategy

Based on evolutionary game theory and the replication dynamics equation of the local government’s “active implementation” behavior, taking the first derivative of and setting the local government’s replication dynamic equation to zero, the evolutionary trend of the local government’s behavior and the asymptotic stability phase diagram wase obtained (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Evolutionary Trend of Local Government Behavior and Asymptotic Stability Phase Diagram.

When the local government’s strategy reaches stability, it must satisfy the stability theorem of differential equations, as and .

- (1)

- When , holds true for any interval of , indicating that the local government cannot determine a stable strategy.

- (2)

- When , the two possible equilibrium points of are and .

- (a)

- When , and , suggesting that under this condition, is the evolutionarily stable strategy for the local government, meaning the local government will tend to choose “passive implementation”.

- (b)

- When , and , indicating that under this condition, is the evolutionarily stable strategy for the local government, meaning the local government will tend to choose “active implementation”.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the evolution of the local government’s strategy is influenced by the strategy choices of collective economic organizations and enterprises, as well as factors such as the communication and coordination costs between local government, collective economic organizations, and enterprises, the payoff that local government gains from adopting the “active implementation” strategy, and the losses it can avoid by choosing the “passive implementation” strategy. When , the local government tends to choose “active implementation”. The pilot program of BRHCOCL clearly stipulates that collective economic organizations must participate voluntarily and operate independently. When the collective economic organization chooses to “agree” to participate in theproject and can bear certain development costs and market risks, the probability of local government adopting the “active implementation” strategy is higher.

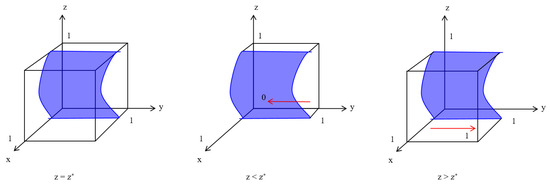

3.1.2. Stability Analysis of the Collective Economic Organization’s Strategy

Based on evolutionary game theory and the replication dynamics equation of the collective economic organization’s “agreement” behavior, by taking the first derivative of and setting the replication dynamics equation of the collective economic organization to zero, the evolutionary trend of the collective economic organization and the asymptotic stability phase diagram was obtained (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Evolutionary Trend of collective economic organization Behavior and Asymptotic Stability Phase Diagram.

When the collective economic organization’s strategy reaches stability, it must satisfy the stability theorem of differential equations, as and .

- (1)

- When , holds true for any interval of , indicating that the collective economic organization cannot determine a stable strategy.

- (2)

- When , the two possible equilibrium points of are and .

- (a)

- When , and , suggesting that under this condition, is the evolutionarily stable strategy for the local government, meaning the collective economic organization will tend to choose “agreement”.

- (b)

- When , and , which indicates that under this condition, is the evolutionarily stable strategy for the local government, meaning the collective economic organization will tend to choose “disagreement”.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the evolution of the collective economic organization’s strategy is influenced by the strategic choices of local government and enterprises, as well as factors such as the payoff the collective economic organization gains from adopting the “agree” strategy, the cost of bargaining with enterprises, the financial subsidies received, development and construction costs, and the market and policy risks borne. When , the collective economic organization tends to choose the “agree” strategy. Given the weak strength of the collective economic organization, when enterprises choose to “participate” in the BRHCOCL project, the enterprises bear most of the development and construction costs and the risks. Whether the collective economic organization transfers land or contributes land as equity, it can obtain certain returns. Therefore, when enterprises choose the “participate” strategy, the probability of the collective economic organization choosing the “agree” strategy is higher.

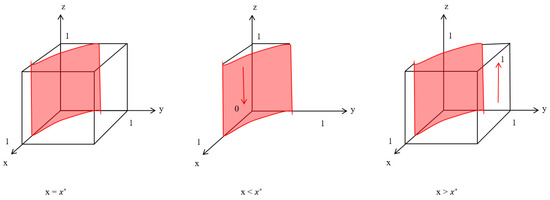

3.1.3. Stability Analysis of the Enterprise’s Strategy

Based on evolutionary game theory and the replication dynamics equation of the enterprise’s “participation” behavior, taking the first derivative of and setting the replication dynamic equation of the enterprise to zero, the evolutionary trend of the enterprise and the asymptotic stability phase diagram were obtained (See Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Evolutionary Trend of Enterprise Behavior and Asymptotic Stability Phase Diagram.

When the enterprise’s strategy reaches stability, it must satisfy the stability theorem of differential equations, as and .

- (1)

- When , holds true for any interval of , indicating that the enterprise cannot determine a stable strategy.

- (2)

- When , the two possible equilibrium points of are and .

- (a)

- When , and , suggesting that under this condition, is the evolutionarily stable strategy for the local government, meaning the enterprise will tend to choose “participation”.

- (b)

- When , and , indicating that under this condition, is the evolutionarily stable strategy for the local government, meaning the enterprise will tend to choose “non-participation”.

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the evolution of the enterprise’s strategy is influenced by the strategic choices of the collective economic organization and other enterprises, as well as factors such as the payoff the enterprise receives from participation, the financial subsidies obtained, the cost of bargaining with the collective economic organization, communication and coordination costs, the market and policy risks it bears, and the losses it can avoid by adopting a “non-participation” strategy. When , the enterprise shows willingness to “participate”. The BRHCOCL project is in the pilot exploration phase, with both opportunities and challenges. When the government adopts an “active implementation” strategy to provide policy guarantees, support, and even financial subsidies, it can reduce the policy risks and development costs faced by enterprises, and lower the costs of bargaining, communication, and coordination with the collective economic organization. Therefore, when the government strongly supports the project, the enterprise is more willing to bear certain risk costs and participate in the development, construction, and operation of BRHCOCL projects.

3.1.4. Asymptotic Stability Analysis Under a Mixed Strategy

According to evolutionary game theory, each of the three participants will choose a corresponding strategy based on various factors, gradually tending toward a stable state. By conducting local stability analysis of the system’s Jacobian matrix, the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS) of the system was obtained. Based on the replication dynamics equation of the system, the Jacobian matrix (J) of the system can be derived as follows:

Let , and we obtain a total of 8 local equilibrium points. By substituting each equilibrium point into the matrix, the corresponding Jacobian matrix for each equilibrium point was obtained, along with the eigenvalues for each matrix, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Behavior Choices of the Three Parties and Payoff Matrix.

According to Lyapunov’s first method, if an equilibrium point is an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), the corresponding eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix should all be negative. In the above case, points A(0, 0, 1), D(1, 0, 0), and E(1, 0, 1) clearly do not satisfy the stability condition. The remaining stable points and equilibrium conditions are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Stable Points and Equilibrium Conditions.

Scenario 1: When the local government chooses the “passive implementation” strategy, the collective economic organization chooses to “disagree” with the use of collective construction land for building rental houses, and the enterprise chooses “non-participation” in investing in and constructing rental houses, O(0, 0, 0) is the equilibrium point. The strategies of all three parties are stable and must satisfy the condition At this point, the payoff obtained by the collective economic organization is less than the sum of the development and operational costs, market risks, policy risks, and avoidable losses borne by the collective economic organization if it participates while the other two parties do not. As a result, the BRHCOCL pilot policy will be in a state of stagnation.

Scenario 2: When the local government chooses the “passive implementation” strategy, the enterprise chooses the “non-participation” strategy, and the collective economic organization adopts the “agreement” strategy and is willing to bear the development and construction costs, B(0, 1, 0) becomes the equilibrium point. The strategies of all three parties are stable and must satisfy the following conditions: , and

This means that the local government’s payoff must be greater than the losses it can avoid, as well as the communication and coordination costs with the enterprise when the enterprise chooses the “non-participation” strategy, while the collective economic organization’s payoff must be greater than the sum of the development and operational costs, market risks, policy risks, and avoidable losses borne by the collective economic organization when the other two parties do not participate.

The financial subsidy received by the collective economic organization, the payoff received by the enterprise, and the market risks faced by the collective economic organization when the enterprise chooses the “participation” strategy, along with the legal risks faced by the enterprise in the “participation” strategy, must be less than the sum of the market risks, policy risks, and the development and operational costs borne by the collective economic organization when the other two parties do not participate. In such a case, the collective economic organization must independently bear the development and construction costs, as well as various risks, making policy implementation very difficult.

Scenario 3: When the local government chooses the “passive implementation” strategy, the collective economic organization adopts the “agree” strategy, and the enterprise chooses the “participation” strategy, C(0, 1, 1) is the equilibrium point. The strategies of all three parties are stable and must simultaneously satisfy the following conditions: , and .

This implies that the payoff for local government when it adopts the “active implementation” strategy must be less than the losses it can avoid by choosing the “passive implementation” strategy.

The payoff for the collective economic organization when it adopts the “agree” strategy must be greater than the bargaining costs with the enterprise and the losses it can avoid by choosing the “disagree” strategy, considering the market risks faced by the collective economic organization when the enterprise adopts a “participation” strategy, and the legal risks faced by the local government when it adopts the “passive implementation” strategy.

When the collective economic organization adopts the “agree” strategy and the enterprise adopts the “participation” strategy, the developmental and operational costs met by the enterprise, the cost of bargaining between the two, the losses the enterprise can avoid by choosing the “non-participation” strategy, and the market and policy risks faced by the collective economic organization when the enterprise chooses the “non-participation” strategy must be less than the benefits the enterprise gains, with regard to the financial subsidies as well as the market and policy risks the collective economic organization faces when the enterprise adopts the “participation” strategy.

At this point, the collective economic organization and the enterprise cooperate to develop and construct rental houses, with the enterprise bearing the costs of development and construction. There are no financial subsidies, and the enterprise focuses on the ration of risk shared with the collective economic organization. In the context of underdeveloped rules and procedures for transactions involving collective land, when the local government chooses the “passive implementation” strategy, the collective economic organization lacks the capacity and strength to bear risks. With low returns from the BRHCOCL project, it is difficult for enterprises and collective economic organizations to reach cooperative agreement. However, when the government’s transaction rules are relatively sound, the transaction platform is transparent, the approval process is efficient, the rural collective land market is well developed, the collective economic organization has the negotiating power to engage with the enterprise without government intervention, and rental house building is profitable, the collective economic organization and the enterprise can cooperate with minimal government intervention.

Scenario 4: When the local government chooses the “active implementation” strategy, the collective economic organization adopts the “agree” strategy, but the enterprise chooses the “non-participation” strategy, F(1, 1, 0) becomes the equilibrium point. The strategies of all three parties are stable and must simultaneously satisfy the following conditions: , and .This means that the payoff for local government when it adopts the “active implementation” strategy must be greater than the communication and coordination costs incurred by the enterprise when it chooses the “non-participation” strategy in addition to losses the local government can avoid by adopting the “passive implementation” strategy.

The development and operational costs borne by the collective economic organization when the enterprise chooses the “non-participation” strategy, the losses the collective organization can avoid by adopting the “disagree” strategy, and the market risks the collective organization bears when it chooses the “agree” strategy and the enterprise chooses the “non-participation” strategy must be less than the payoff the collective economic organization receives when it chooses the “agree” strategy combined with the financial subsidies it receives when the enterprise chooses the “non-participation” strategy.

The payoff the enterprise receives, the financial subsidies, and the market risks the collective economic organization bears when the enterprise chooses the “participation” strategy must be less than the development and operational costs, bargaining costs, market risks, and avoidable losses when the enterprise chooses the “non-participation” strategy.

Under these circumstances, the enterprise chooses “non-participation” in the BRHCOCL project due to reasons such as insufficient funds and excessive risks. Although the collective economic organization agrees to the project and has some level of financial strength, it is unable to complete the project on its own. Government financial subsidies and policy guarantees are necessary for the project to move forward. Once completed, the building will be leased to the government for unified management, and it will be incorporated into the local public rental housing system.

Scenario 5: When the local government chooses the “active implementation” strategy, the collective economic organization adopts the “agree” strategy, and the enterprise chooses the “participation” strategy, G(1, 1, 1) becomes the equilibrium point. The strategies of all three parties are stable and must simultaneously satisfy the following conditions: , and .This means that the payoff for local government when it adopts the “active implementation” strategy must be greater than the losses it can avoid by adopting the “passive implementation” strategy, while the bargaining costs between the collective economic organization and the enterprise, the market risks borne by the collective economic organization, and the losses it can avoid by adopting the “disagree” strategy must be less than the benefits the collective economic organization receives when it adopts the “agree” strategy and the enterprise adopts the “participation” strategy.

The development and operational costs, bargaining costs, and the market risks faced by the collective economic organization when the enterprise chooses the “participation” strategy must be less than the benefits and financial subsidies the enterprise receives when it chooses the “participation” strategy, along with the market risks the collective economic organization bears.

In this situation, the government acts as a bridge between the collective economic organization and the enterprise, promoting the implementation of BRHCOCL policy. The government actively completes pilot tasks, communicates and coordinates with the collective economic organization to reduce bargaining costs, helps the collective economic organization obtain land revenue, and allows the enterprise to bear development and construction costs along with some market risks. The government provides financial support to the enterprise and helps mitigate policy risks, ensuring the smooth progress of the BRHCOCL project.

The above analysis indicates that only when two of the three parties—local government, enterprises, and collective economic organizations—cooperate, or when all three parties collaborate, is it likely that the BRHCOCL pilot policy will be successfully implemented. The actions of one party influence the behavioral choices of the other two parties. Key factors that influence the decisions of the three stakeholders include local government attitude toward the pilot policy, the cost of communication and coordination between the three parties, the collective economic organization’s cognitive capacity and ability to engage in the market economy, as well as the benefits that the collective economic organization and enterprises gain from participating in the BRHCOCL project. These factors are not only central to the interests of stakeholders but are also key elements that can trigger conflicts among core stakeholders. When one or two of the three parties is unwilling to participate in the BRHCOCL projects, it indicates an irreconcilable conflict among the core stakeholders, manifesting as high communication and coordination costs, insufficient capability, and difficulties in sharing risks.

3.2. Simulation Analysis and Case Study

The stability analysis results indicate that strategic interaction between local government, collective economic organizations, and enterprises may lead to five possible scenarios. To validate the effectiveness of the evolutionary stability analysis, we conducted numerical simulations using Python 3.12, enabling more intuitive visualization of the evolutionary paths of the tripartite game.

To ensure that the simulation closely reflected real-world conditions, we conducted field research on a BRHCOCL project in Huayuan Village, Qingbaijiang District, Chengdu. The data obtained from this field study served as a reference for parameter selection [33]. Additionally, we integrated the simulation results with real-world cases in order to assess the robustness of our findings [34,35].

The simulation parameters were determined as follows. In the “Sunshine Dongshanli” project in Huayuan Village, the village committee and the company jointly invested RMB 9.29 million, with the village committee contributing RMB 4.74 million and Ronghe Modern Agriculture Development Co., Ltd. Investing RMB 4.55 million(C4). The District Rental Housing Property Security Service Center provided a financial subsidy of RMB 8.31 million (E1). The project resulted in the construction of 98 rental units, generating an average annual rental income of RMB 13,600 per unit. Assuming a 70-year property ownership period, the projected revenue amounts to RMB 93.32 million. Based on investment proportions and relevant tax regulations, the estimated earnings were calculated as follows. The local government (V1) is expected to receive RMB 750,000, the collective economic organization (V2) RMB 20.11 million, and the enterprise (V3) RMB 19.32 million. The total cost of the project’s construction was RMB 28.2043 million. If the collective economic organization had proceeded independently without participation from enterprises, its developmental and operational costs (C3) would have been RMB 15.16 million.

The policy risk coefficient was calculated as the normalized average ratio of the number of policy documents issued by pilot cities and their respective provinces in 2023 to the total number of policies. The market risk coefficient was derived from the normalized average rent-to-sale ratio of pilot cities in 2023 (See Table 8). Accordingly, in the simulation analysis, the values of , , , , , , , and were fixed at 75, 2011, 1932, 1516, 455, 831, 0.46, and 0.72, respectively. The evolutionary game outcomes under the five scenarios are discussed below.

Table 8.

The policy risk coefficient m and the market risk coefficient n.

3.2.1. Simulation Analysis Results for Scenario One

In Scenario One, the following conditions hold: .

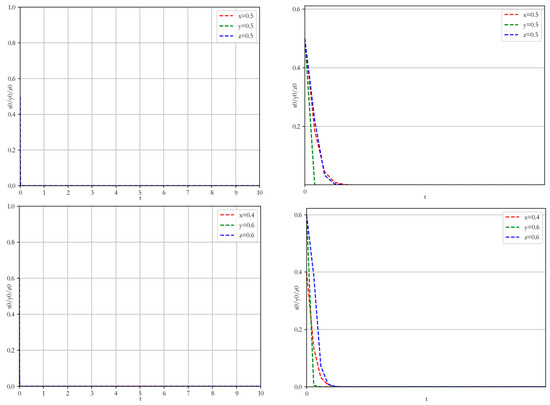

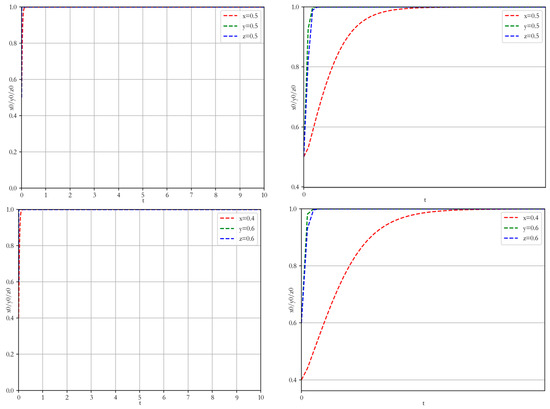

The parameter values were set as follows: = 75, = 2011, = 1932, = 10, = 15, = 1516, = 455, = 35, = 32, = 831, = 262, = 575, = 346, = 0.46, = 0.72, = 288, = 1955, = 388. Following the approach of Xie et al. [36], the initial values for (x, y, z) were set as (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) and (0.4, 0.6, 0.6) to examine whether the initial values would influence the results. The simulation results are shown in Figure 5. It was observed that regardless of how the initial values changed, the game system ultimately converged to (0, 0, 0); i.e., the strategy of “passive execution, disagreement, and non-participation” became the stable equilibrium strategy of the tripartite evolutionary game in this scenario.

Figure 5.

Evolutionary Path of the Game in Scenario One.

Currently, construction has not begun in any of the pilot land plots in Nanjing, one of the cities selected for the second batch of BRHCOCL projects on collectively owned construction land. In 2018, the Nanjing municipal government designated three pilot land plots: the Nanxiang Mountain plot in Qixia District, the Yepo Village plot in Liuhe District, and the Linshan Village plot in Pukou District. According to the Nanjing Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning, the selected pilot sites face poor conditions due to limitations in urban and land planning. The Nanxiang Mountain plot in Qixia District is located far from centers of economic activity and major streets, resulting in insufficient demand for rental housing and high market risks. The Linshan Village plot in Pukou District is designated for metro land acquisition, requiring a payment of RMB 120 million to the metro company before the construction of rental housing. Additionally, the estimated construction costs for the housing project are RMB 370 million, making it financially unfeasible for collective economic organizations to bear. Similarly, the Yepo Village plot in Liuhe District faces challenges due to the limited economic capacity of collective economic organizations and the lack of activity in the rental housing market. This evolutionary path is consistent with the stability analysis findings.

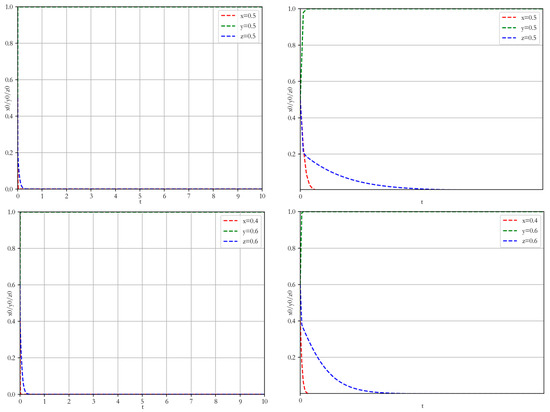

3.2.2. Simulation Analysis Results for Scenario Two

In Scenario Two, the following conditions hold: , and .

The parameter values were set as follows: = 75, = 2011, = 1932, = 10, = 15, = 1516, = 455, = 35, = 32, = 831, = 262, = 75, = 46, = 0.46, = 0.72, = 288, = 255, = 1668. The initial values for (x, y, z) were set as (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) and (0.4, 0.6, 0.6) to examine the influence of the initial conditions on the results. The simulation results are shown in Figure 6. It was observed that, regardless of how the initial values changed, the game system ultimately converged to (0, 1, 0), i.e., the strategy of “passive execution, agreement, and non-participation” became the stable equilibrium strategy of the tripartite evolutionary game in this scenario. Taking the early pilot project in Beijing, the Haizhuo Village project, as an example, the project was approved by the joint meeting of the “two committees” of Haizhuo Village, and construction began in December 2010, with a total investment of RMB 570 million. By the end of 2017, the village collective had paid over RMB 400 million. During the construction period, the town, district, and city governments attached great importance to the project, but due to the slow approval process (as there were no precedents), policy uncertainties, and legal risks, the project was delayed for a long time before the nationwide pilot policy was introduced. This evolutionary path is consistent with the stability analysis findings.

Figure 6.

Evolutionary Path of the Game in Scenario Two.

3.2.3. Simulation Analysis Results for Scenario Three

In Scenario Three, the following conditions hold: , and .

The parameter values were set as follows: = 75, = 2011, = 1932, = 10, = 15, = 1516, = 455, = 35, = 32, = 831, = 262, = 575, = 346, = 0.46, = 0.72, = 288, = 955, = 388. The initial values for (x, y, z) were set as (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) and (0.4, 0.6, 0.6) to examine the influence of the initial conditions on the results. The simulation results are shown in Figure 7. It was observed that, regardless of how the initial values changed, the game system ultimately converged to (0, 1, 1), i.e., the strategy of “passive execution, agreement, and participation” became the stable equilibrium strategy of the tripartite evolutionary game in this scenario.

Figure 7.

Evolutionary Path of the Game in Scenario Three.

The Xizhihé Village project in Shibalidian Township, Chaoyang District, Beijing, serves as an exemplary case. It was jointly developed by the Beijing Capital Group and the collective economic organization of Shibalidian Township. The collective economic organization covered the costs for land preparation in the initial stages and holds a 51% equity stake, based on 40 years of land use rights. The Beijing Capital Group met the land clearing fees and construction costs, holding a 49% equity stake. The joint venture established by the two entities is responsible for the operation of the project. The Capital Heyuan Fanxing Rental Housing Community, developed as part of this project, is currently the largest rental housing community of its kind in Beijing. The first and second phases of the community provide over 6500 rental units, with an occupancy rate exceeding 90%. This evolutionary path is consistent with the stability analysis findings.

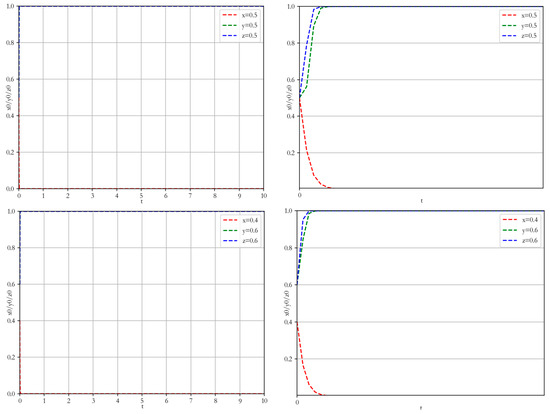

3.2.4. Simulation Analysis Results for Scenario Four

In Scenario Four, the following conditions hold: , and . The parameter values were set as follows: = 75, = 2011, = 1932, = 2, = 5, = 1516, = 455, = 3, = 4, = 831, = 10, = 75, = 46, = 0.46, = 0.72, = 65, = 255, = 166. The initial values for (x, y, z) were set as (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) and (0.4, 0.6, 0.6) to examine the influence of the initial conditions on the results. The simulation results are shown in Figure 8. It was observed that, regardless of how the initial values changed, the game system ultimately converged to (1, 1, 0), i.e., the strategy of “active execution, agreement, and non-participation” became the stable equilibrium strategy of the tripartite evolutionary game in this scenario.

Figure 8.

Evolutionary Path of the Game in Scenario Four.

Taking the pilot project in Xiangyang Village, Xiaoshan District, Hangzhou, as an example, the village received approximately RMB 200 million from the land transfer. The village collective had over 10 million yuan in funds, which were able to cover the construction costs of the rental housing. Despite the possibility of project losses, the village collective considered that the project would improve the investment environment for enterprises and stimulate nearby economic development. Therefore, it actively sought to implement the BRHCOCL pilot project. The Xiaoshan District government provided policy support, including exemptions from municipal civil defense fees, simplified bidding procedures, and the waiver of the feasibility report. This created a collaborative model of “village collective self-construction, government collaboration, and regional development,” as described in the case study. This evolutionary path is consistent with the stability analysis findings.

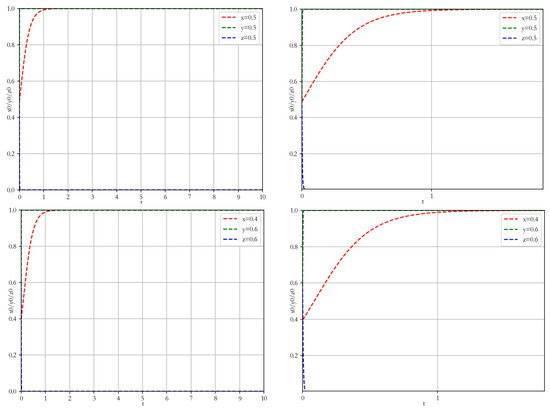

3.2.5. Simulation Analysis Results for Scenario Five

In Scenario Five, the following conditions hold: , and . The parameter values were set as follows: = 75, = 2011, = 1932, = 2, = 5, = 1516, = 455, = 3, = 4, = 831, = 200, = 950, = 20, = 0.46, = 0.72, = 28, = 455, = 525. The initial values for (x, y, z) were set as (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) and (0.4, 0.6, 0.6) to examine the influence of the initial conditions on the results. The simulation results are shown in Figure 9. It was observed that, regardless of how the initial values changed, the game system ultimately converged to (1, 1, 1), i.e., the strategy of “active execution, agreement, and participation” became the stable equilibrium strategy of the tripartite evolutionary game in this scenario.

Figure 9.

Evolutionary Path of the Game in Scenario Five.

The most common approach in recently completed projects has been a collaborative model involving all three parties. The “Dongshan Sunshine Li” project in Huayuan Village, Qingbaijiang District, Chengdu, serves as an illustrative case. In 2019, the Qingbaijiang District government identified the site for a BRHCOCL project on collectively owned construction land. The plot is located in Group 1 of Huayuan Village, Qingquan Town, covering an area of 7.18 acres and categorized as collective village construction land. The project involves collaboration between the Qingbaijiang District government, the village committee of Huayuan Village, and Chengdu Ronghe Modern Agricultural Development Co., Ltd. Construction of the project commenced in December 2019 and was completed in December 2020, with 98 rental units built. In 2022, the entire project was leased to the Aerospace Cyberspace Industrial Technology Research Institute, a tenant in a nearby industrial park, for use as staff accommodation. This evolutionary path is consistent with the stability analysis findings.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

In the context of the rural revitalization strategy, activating idle rural resources and increasing farmers’ incomes are key issues in constructing a modern socialist nation. While the development status of rural areas in China varies greatly, the problem of idle resources on collective construction land, such as “hollow villages,” abandoned factories, and old mining sites, is widespread. The use of collective construction land for building rental housing helps revitalize and utilize idle rural land resources, promoting the efficient and intensive use of rural land. Moreover, rental income from these housing projects can serve as a stable and sustainable economic source for rural collective economic organizations and households, contributing to increased property-based income for rural residents and optimizing the distribution of benefits between urban and rural areas.

The pilot policy of BRHCOCL was introduced alongside significant changes in China’s land system. In the context of the fourth land reform, implementing the pilot policy for building rental housing on collectively owned construction land faces challenges such as conflicts of rights, conflicting interests, and the absence of clear regulations among multiple stakeholders. The relationships between these stakeholders are complex, and the inevitable conflicts of interest hinder the smooth execution of projects.

This study provides an in-depth exploration and analysis of the implementation process of the pilot policy of BRHCOCL. Using a mixed-methods approach combining SNA, case study, and game theory analysis, we identified the key stakeholders in the execution of policy on collectively owned construction land and pinpointed the critical factors that hinder policy implementation. Based on these findings, we offer suggestions for improving and optimizing the policy.

Theoretically, this research advances the theoretical understanding of polycentric governance in land policy implementation by dissecting the decision-making dynamics of stakeholders in China’s pilot policy of building rental housing on collective construction land. We identified three core subjects in the implementation of the pilot policy of building rental housing on collective construction land. The implementation of the pilot policy involves decision-making by multiple actors, raising issues of coordination [37]. We considered several types of factors that lead to failure of policy implementation, including policy risks, market risks, the cost of communication and coordination between the core stakeholders, and the capacity of collective economic organizations, in addition to the potential benefits.

This work also bridges stakeholder theory [38] and the literature on policy implementation [39]. Prior research on collective land policies [40,41,42] predominantly focused on macro-level institutional barriers, such as ambiguous property rights. By contrast, our identification of “coordination costs” as a critical failure factor—manifested in prolonged negotiations between villagers’ committees and developers—highlights the micro-level behavioral constraints that hinder polycentric collaboration.

Practically, by analyzing the experiences of four failed projects and three successful ones, we emphasize the importance of stakeholder cooperation and provide valuable insights and lessons for the successful execution of the policy. The four failed cases were early pilot projects, and the legal risks associated with the imperfections of the relevant systems and the risks of unknown market returns prevented the development of cooperation. In the three successful cases, the role of the collective economic organization was instrumental. Collective economic organizations can help government or enterprises to negotiate and communicate with villagers, thus reducing transaction costs. These findings also serve as a benchmark and guide for the nationwide implementation of the policy.

This study also includes particular uncertainties and limitations. First, it examines the game theory interactions only among three key stakeholder groups, without considering other potential stakeholders in the building of rental housing on collectively owned construction land, such as financing institutions, media, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These actors may have a significant impact on the projects or be involved in more complex game-theoretic relationships with the three main stakeholders. Second, the tripartite game model does not incorporate the formation of coalitions among stakeholders, warranting further investigation using cooperative game theory frameworks in future studies. For example, collusion between enterprises and local governments could also lead to the failure of rental housing projects on collectively owned construction land. Third, parameter calibration requires greater practical grounding. While the current parameters were derived from a specific case study, their applicability remains constrained by significant regional and project-specific variations. Future investigations should prioritize the development of adaptive parameter frameworks that account for spatial heterogeneity and contextual operational variables.

4.2. Conclusions

This paper identifies the three categories of core stakeholder involved in the building of rental housing on collectively owned land, deriving and comparing the equilibrium states of the tripartite game under five different scenarios. The analysis reveals that successful implementation of the rental housing building policy relies on cooperation between any two or all three of the core stakeholders: local governments, enterprises, and collective economic organizations. Further analysis of the conditions required for cooperation among these three stakeholders in the implementation of the policy reveals that policy risks, market risks, the cost of communication and coordination between the core stakeholders, the capacity of collective economic organizations, and the potential benefits are key influencing factors. Based on these findings, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

- 1.

- Improve the institutional framework for building rental houses and reduce policy risks and transaction costs, as follows:

- (1)