Nature Through Young Eyes: Exploring Children’s Understanding of Nature in Urban Landscapes in Beijing, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

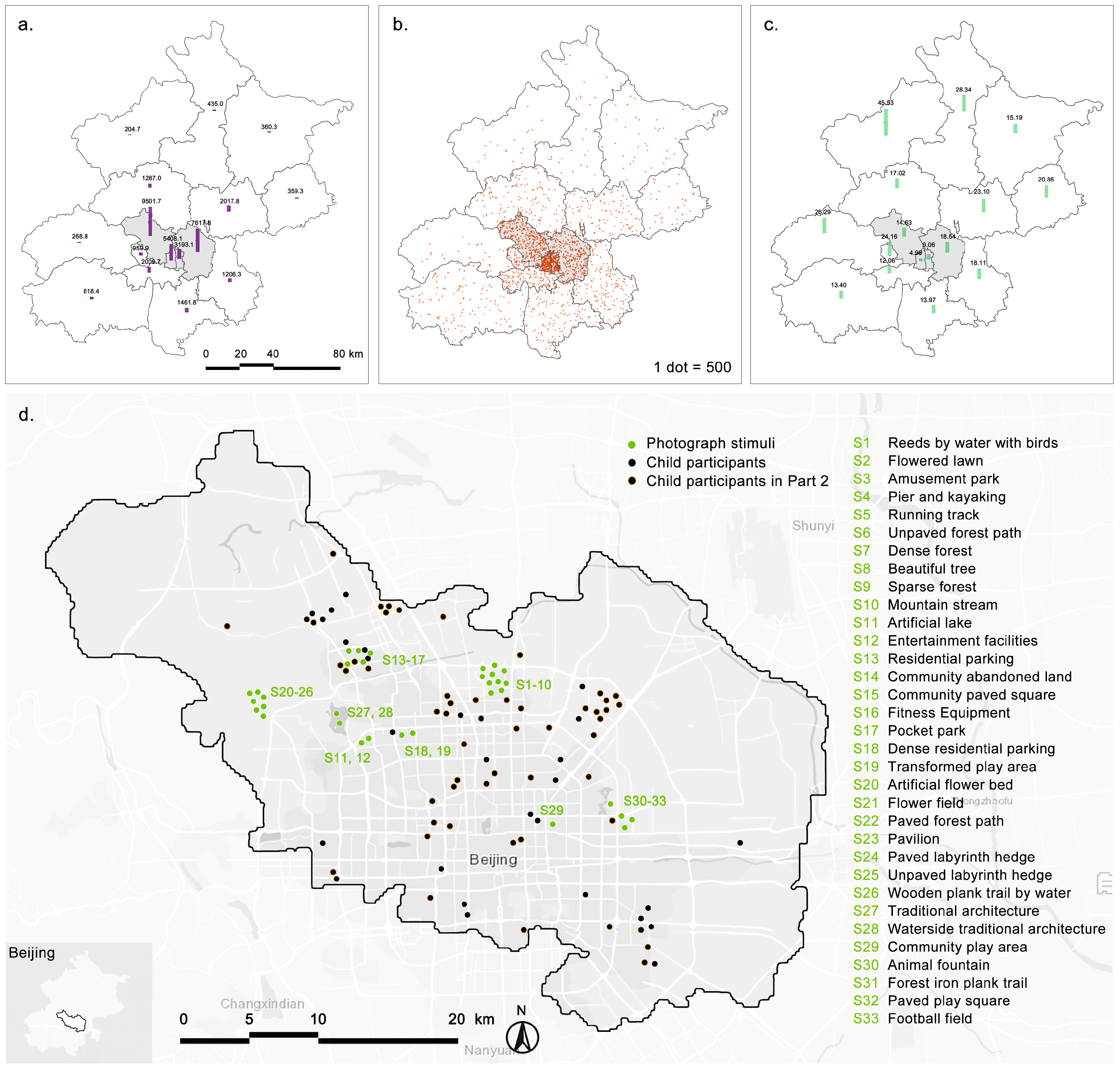

2.1. Research Site and Sampling

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2.1. Part 1—Understanding of Nature

2.2.2. Part 2—Perceptions of Nature in the City

3. Results

3.1. Understanding of Nature—Conceptual and Accessible

3.1.1. Living Organisms

3.1.2. Non-Living Entities

3.1.3. Scenarios—Involving Humans and Nonhumans

3.2. Perception of Nature in the City

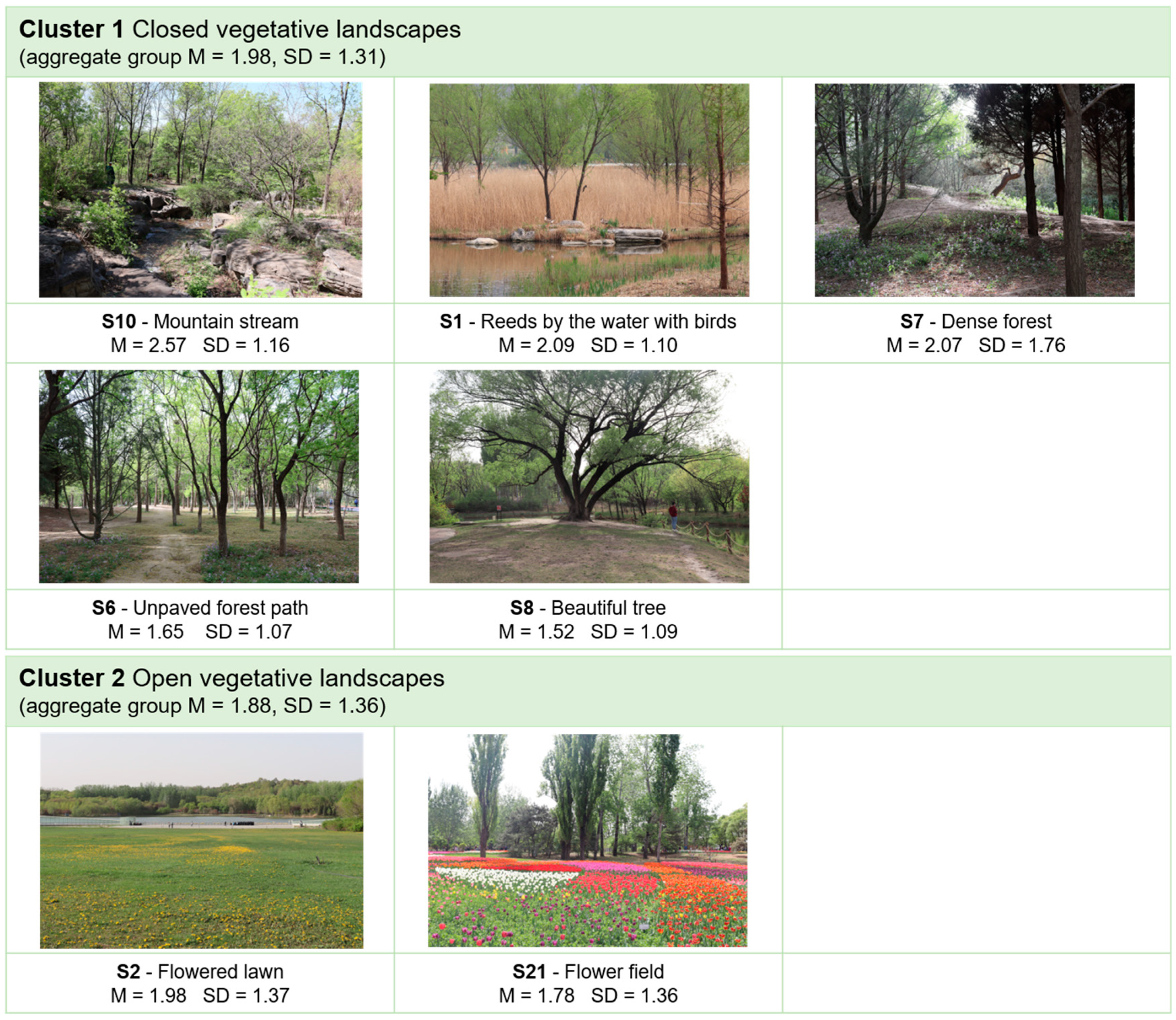

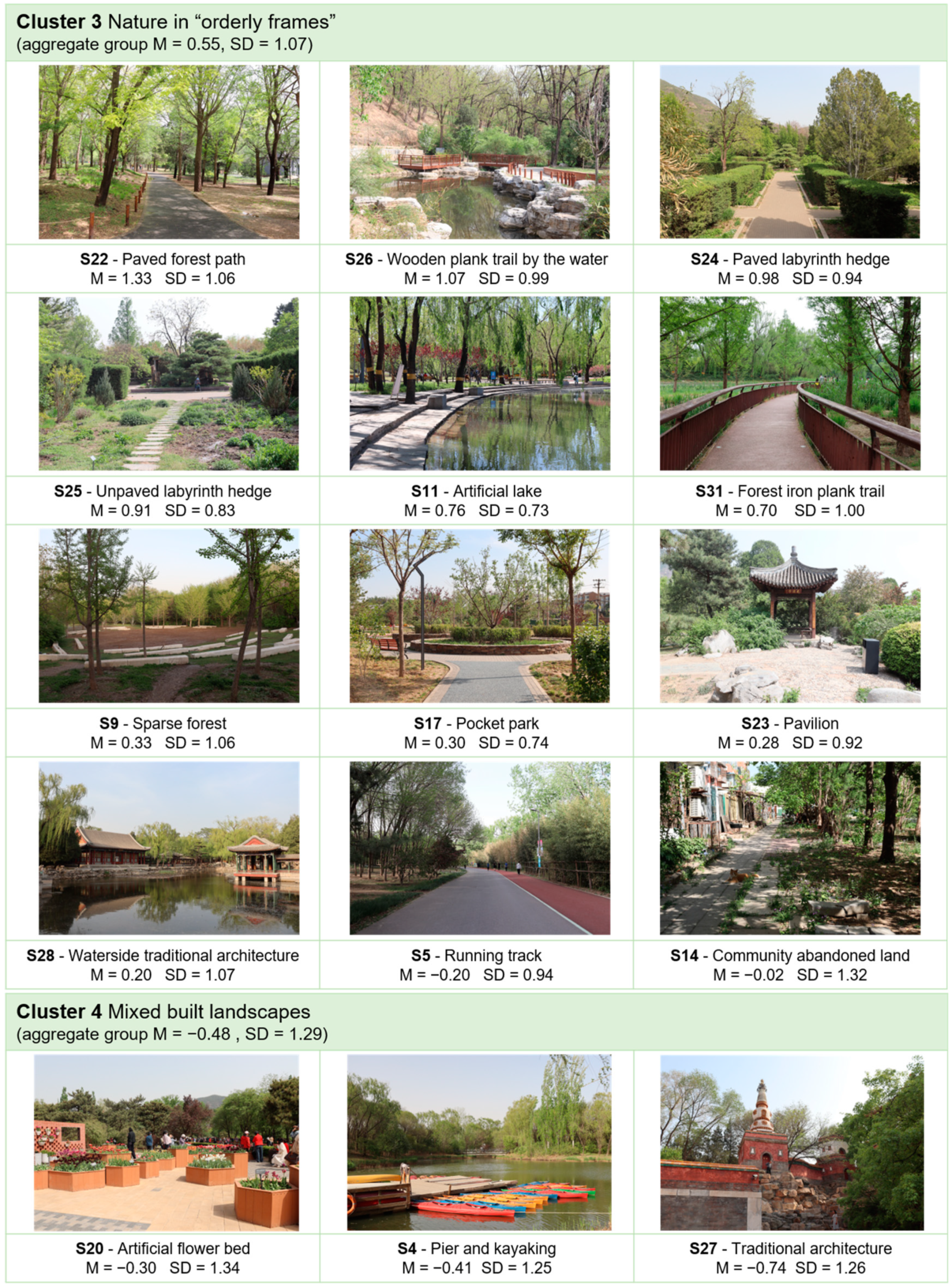

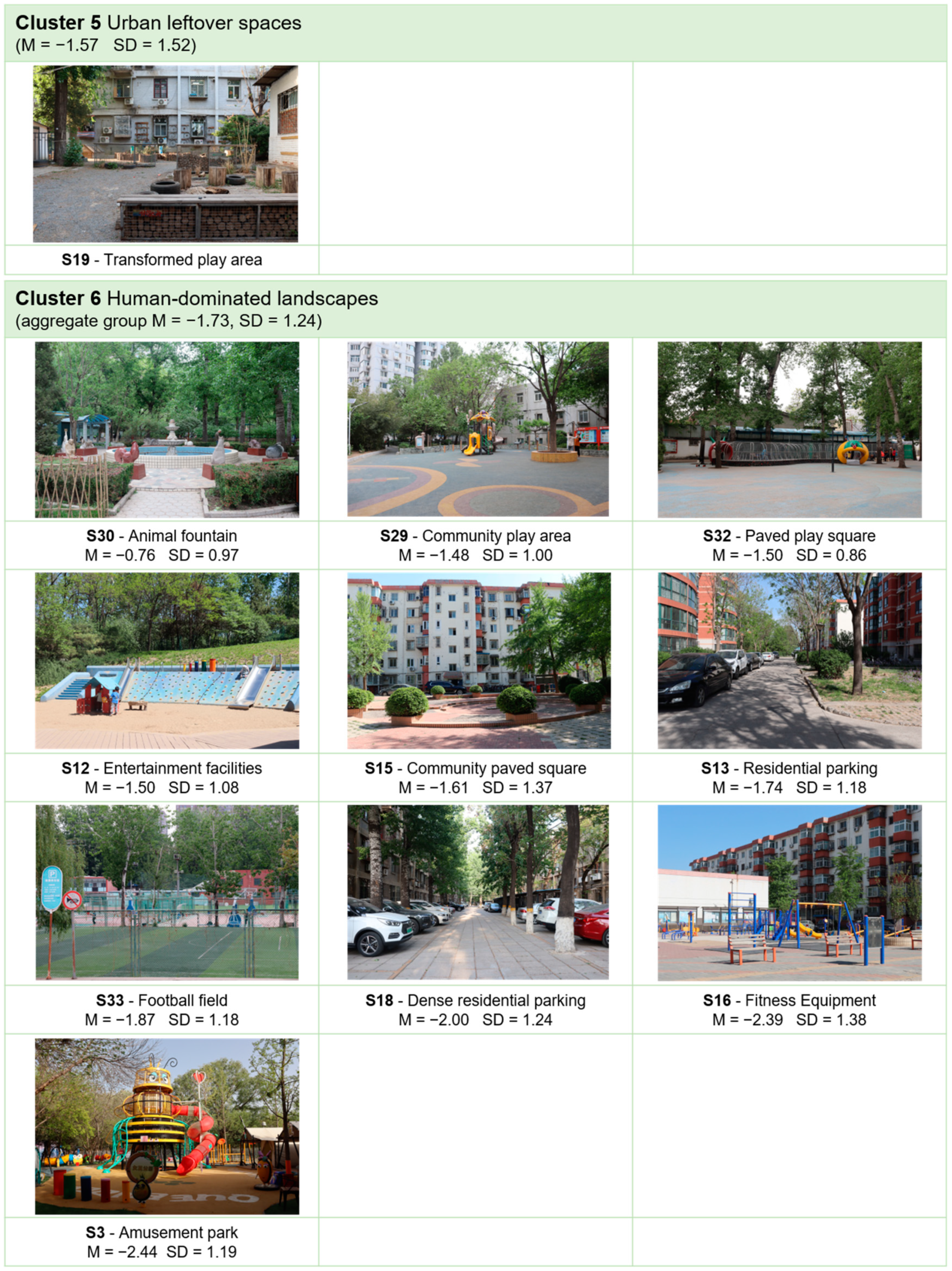

3.2.1. Perceived Naturalness

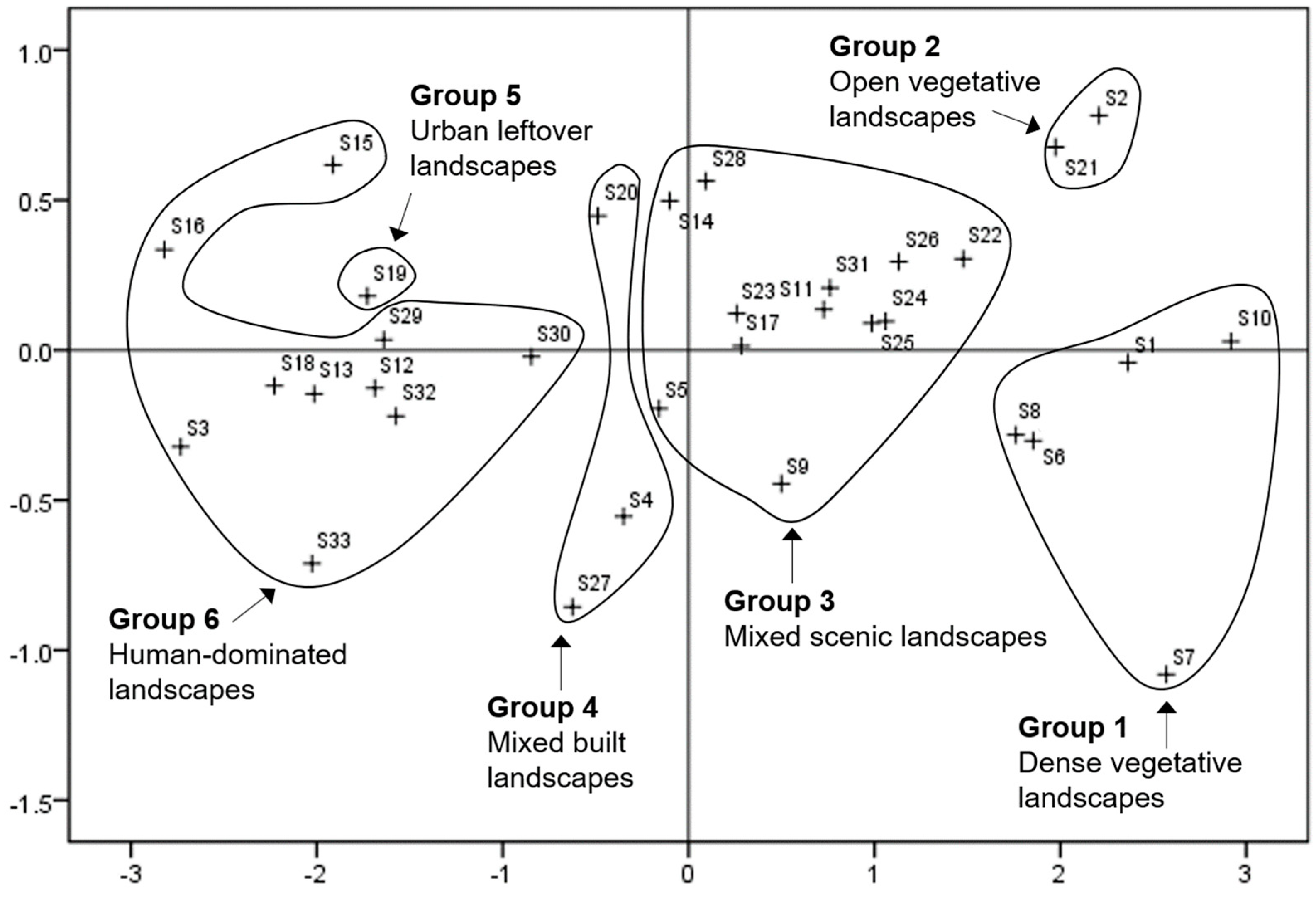

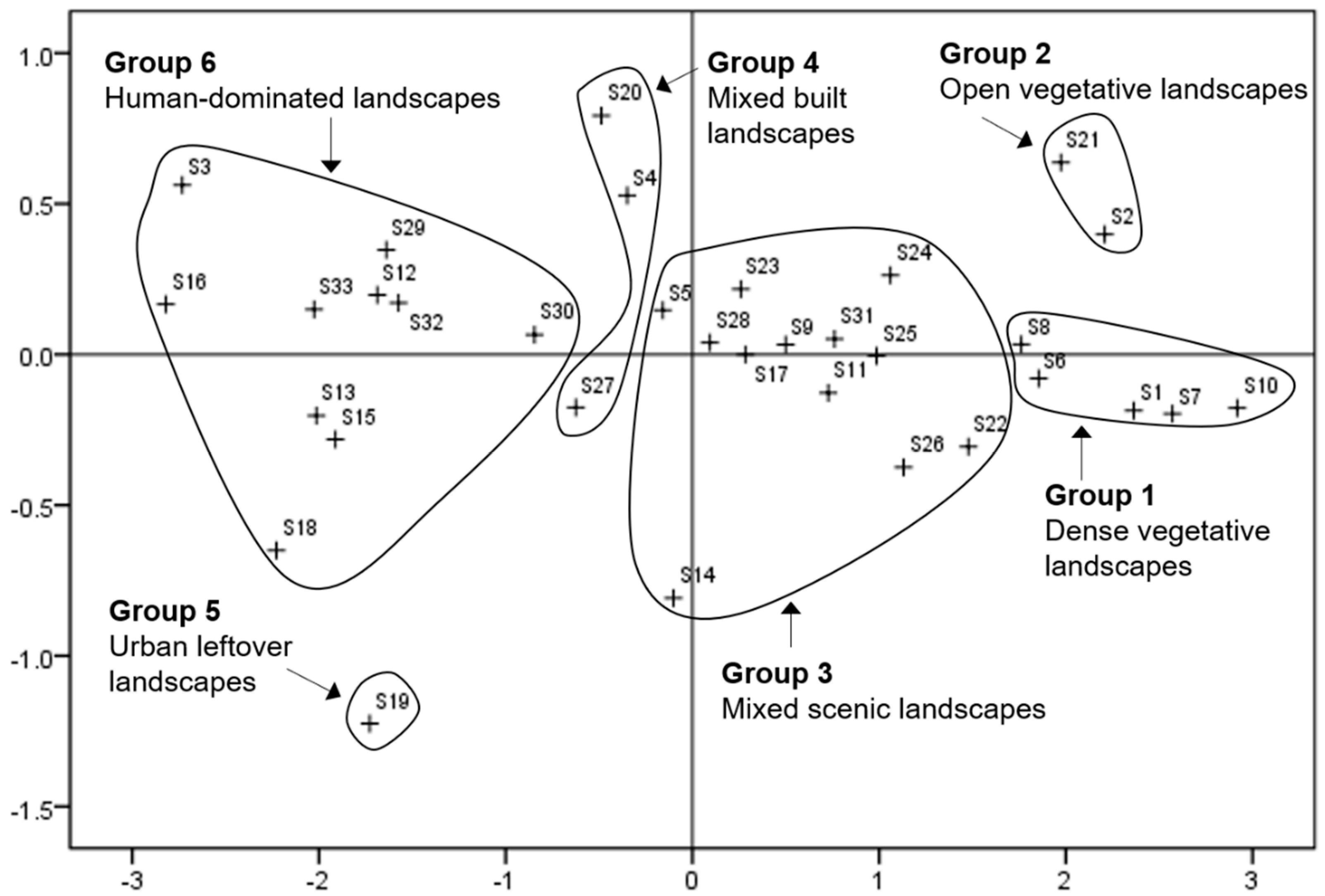

3.2.2. Neighborhood Clusters

3.2.3. Underlying Perceptual Dimensions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chawla, L. Childhood Nature Connection and Constructive Hope: A Review of Research on Connecting with Nature and Coping with Environmental Loss. People Nat. 2020, 2, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.H.; Monroe, M.C. Connection to Nature: Children’s Affective Attitude toward Nature. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder (Updated and Expanded); Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill: New York, USA, 2008; ISBN-13: 978-1-56512-605-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780415475976. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simon, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagot, K.L.; Allen, F.C.L.; Toukhsati, S. Perceived Restorativeness of Children’s School Playground Environments: Nature, Playground Features and Play Period Experiences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Keena, K.; Pevec, I.; Stanley, E. Green Schoolyards as Havens from Stress and Resources for Resilience in Childhood and Adolescence. Health Place 2014, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeland, J.; Moens, M.A.; Beute, F.; Assink, M.; Staaks, J.P.C.; Overbeek, G. A Dose of Nature: Two Three-Level Meta-Analyses of the Beneficial Effects of Exposure to Nature on Children’s Self-Regulation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Green, R.J. The Effect of Exposure to Nature on Children’s Psychological Well-Being: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 81, 127846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.; Ma, H. The Restorative Environmental Sounds Perceived by Children. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 60, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, K.; Perazzo, J.; Brokamp, C.; Gillespie, G.L.; Cecil, K.M.; LeMasters, G.; Yolton, K.; Ryan, P. Residential Surrounding Greenness and Self-Reported Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Adolescents. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Green, R.J. Children’s pro-Environmental Behaviour: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental Knowledge and Conservation Behavior: Exploring Prevalence and Structure in a Representative Sample. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-Based Environmental Education of Children: Environmental Knowledge and Connectedness to Nature, Together, Are Related to Ecological Behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, D.W. Political Economy and the Ecology of Childhood. In Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural and Evolutionary Investigations; Peter, H., Kahn, J., Kellert, S.R., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, R.M. Eden in a Vacant Lot: Special Places, Species and Kids in the Neighborhood of Life. In Children and Nature; Peter, H., Kahn, J., Kellert, S.R., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Van Aart, C.J.C.; Michels, N.; Sioen, I.; De Decker, A.; Bijnens, E.M.; Janssen, B.G.; De Henauw, S.; Nawrot, T.S. Residential Landscape as a Predictor of Psychosocial Stress in the Life Course from Childhood to Adolescence. Environ. Int. 2018, 120, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.R. Biodiversity Conservation and the Extinction of Experience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Evans, M.J.; Yamanoi, T.; Fukano, Y.; Tsuchiya, K.; Koyanagi, T.F.; Kanai, T. How Can We Mitigate against Increasing Biophobia among Children during the Extinction of Experience ? Biol. Conserv. 2020, 242, 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlwill, J.F. The Concept of Nature: A Psychologist’s View. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983; ISBN 978-1-4613-3541-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, G.A. A Theory of Personality: The Psychology of Personal Constructs; Norton: New York, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, P.H.; Kellert, S.R. Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations; Kahn, P.H., Kellert, S.R., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780262112671. [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel, J. Inquiry by Design: Tools for Environment-Behavior Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wijngaarden, V. Q Method and Ethnography in Tourism Research: Enhancing Insights, Comparability and Reflexivity. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckeown, B.; Thoma, D.B. Q Methodology, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, W. The Study of Behaviour: Q-Technique and Its Methodology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, D.G.; Zube, E.H. The Q Sort Method: Use in Landscape Assessment Research and Landscape Planning. In Proceedings on Our National Landscape: A Conference on Applied Techniques for Analysis and Management of the Visual Resource; Elsner, G.H., Smardon, R.C., Eds.; USDA Forest Service: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Green, R. Community Perceptions of Environmental and Social Change and Tourism Development on the Island of Koh Samui, Thailand. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, M.; Johnson, M.F.; Ives, C.D. Values Influence Public Perceptions of Flood Management Schemes. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 291, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather, J.R.; Swaffield, S.R. Visitor Experiences of Kaikoura, New Zealand: An Interpretative Study Using Photographs of Landscapes and Q Method. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naspetti, S.; Mandolesi, S.; Zanoli, R. Using Visual Q Sorting to Determine the Impact of Photovoltaic Applications on the Landscape. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H.; Pitt, D.G.; Evans, G.W. A Lifespan Developmental Study of Landscape Assessment. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.N.; Sarre, P. Personal Construct Theory in the Measurement of Environmental Images. Environ. Behav. 1975, 7, 3–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milcu, A.I.; Sherren, K.; Hanspach, J.; Abson, D.; Fischer, J. Navigating Conflicting Landscape Aspirations: Application of a Photo-Based Q-Method in Transylvania (Central Romania). Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Hout, M.C.; Kardan, O.; Hunter, M.C.R.; Yourganov, G.; Henderson, J.M.; Hanayik, T.; Karimi, H.; Jonides, J. The Perception of Naturalness Correlates with Low-Level Visual Features of Environmental Scenes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detrinidad, E.; López-Ruiz, V.R. The Interplay of Happiness and Sustainability: A Multidimensional Scaling and K-Means Cluster Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbie, M.; Green, R. Public Perceptions of Freshwater Wetlands in Victoria, Australia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 110, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takane, Y.; Young, F.W.; de Leeuw, J. Nonmetric Individual Differences Multidimensional Scaling: An Alternating Least Squares Method with Optimal Scaling Features. Psychometrika 1977, 42, 7–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, J.B. Multidimensional Scaling by Optimising Good- Ness of Fit to a Nonmetric Hypothesis. Psychometrika 1964, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, E.; Arce, C.; Sabucedo, J.M. Classification of Landscapes Using Quantitative and Categorical Data, and Prediction of Their Scenic Beauty in North-Western Spain. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandersee, J.H.; Schussler, E.E. Preventing Plant Blindness. Am. Biol. Teach. 1999, 61, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Goodale, E.; Chen, J. How Contact with Nature Affects Children’s Biophilia, Biophobia and Conservation Attitude in China. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 177, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames. Landsc. J. 1995, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Íñiguez-Rueda, L.; Corraliza, J.A. Experiencing Nature and Children’s Conceptualizations of the Natural World. Child. Geogr. 2016, 14, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Orians, G.H. An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach to Landscape Aesthetics. In Landscape Meanings and Values; Routledge: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Balling, J.D.; Falk, J.H. Development of Visual Preference for Natural Environments. Environ. Behav. 1982, 14, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, M.; Woolley, H. Let’s Splash: Children’s Active and Passive Water Play in Constructed and Natural Water Features in Urban Green Spaces in Sheffield. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 52, 126696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. The Ability of A-Level Students to Name Plants. J. Biol. Educ. 2005, 39, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, P.; Tunnicliffe, S.D. What Plants and Animals Do Early Childhood and Primary Students’ Name? Where Do They See Them? J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2011, 20, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balas, B.; Momsen, J.L. Attention “Blinks” Differently for Plants and Animals. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2014, 13, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schussler, E.E.; Link-Pérez, M.A.; Weber, K.M.; Dollo, V.H. Exploring Plant and Animal Content in Elementary Science Textbooks. J. Biol. Educ. 2010, 44, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey, J.N. Where Have All the Flowers Gone?—The Place of Plants in School Science. J. Biol. Educ. 1987, 21, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link-Pérez, M.A.; Dollo, V.H.; Weber, K.M.; Schussler, E.E. What’s in a Name: Differential Labelling of Plant and Animal Photographs in Two Nationally Syndicated Elementary Science Textbook Series. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2010, 32, 1227–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clucas, B.; McHugh, K.; Caro, T. Flagship Species on Covers of US Conservation and Nature Magazines. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 17, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalino, L.M.; Gheler-Costa, C.; Santos, G.; Gonçalves, M.T.; Fonseca, C.; Leal, A.I. Conservation Priorities for Elementary School Students: Neotropical and European Perspectives. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 2675–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Sub-Categories | Conceptual Nature | Accessible Nature | |

| Living organisms | Total |  |  | |

| Flora | General flora |  |  | |

| Specific flora |  |  | ||

| Fauna | General fauna |  |  | |

| Specific fauna |  |  | ||

| Fungi |  |  | ||

| Non-living entities | Total |  |  | |

| Natural elements |  |  | ||

| Natural phenomena |  |  | ||

| Scenarios | Total |  |  | |

| Human-involved |  |  | ||

| Nonhuman |  |  | ||

= 0%,

= 0%,  = (0%, 12.5%],

= (0%, 12.5%],  = (12.5%, 25%],

= (12.5%, 25%],  = (25%, 37.5%],

= (25%, 37.5%],  = (37.5%, 50%];

= (37.5%, 50%];  = (50%, 67.5%],

= (50%, 67.5%],  = (67.5%, 75%],

= (67.5%, 75%],  = (75%, 87.5%],

= (75%, 87.5%],  = (87.5%, 100%].

= (87.5%, 100%].Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Green, R.J. Nature Through Young Eyes: Exploring Children’s Understanding of Nature in Urban Landscapes in Beijing, China. Land 2025, 14, 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030624

Liu J, Green RJ. Nature Through Young Eyes: Exploring Children’s Understanding of Nature in Urban Landscapes in Beijing, China. Land. 2025; 14(3):624. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030624

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jianjiao, and Raymond James Green. 2025. "Nature Through Young Eyes: Exploring Children’s Understanding of Nature in Urban Landscapes in Beijing, China" Land 14, no. 3: 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030624

APA StyleLiu, J., & Green, R. J. (2025). Nature Through Young Eyes: Exploring Children’s Understanding of Nature in Urban Landscapes in Beijing, China. Land, 14(3), 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030624