Land Property Rights, Social Trust, and Non-Agricultural Employment: An Interactive Study of Formal and Informal Institutions in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

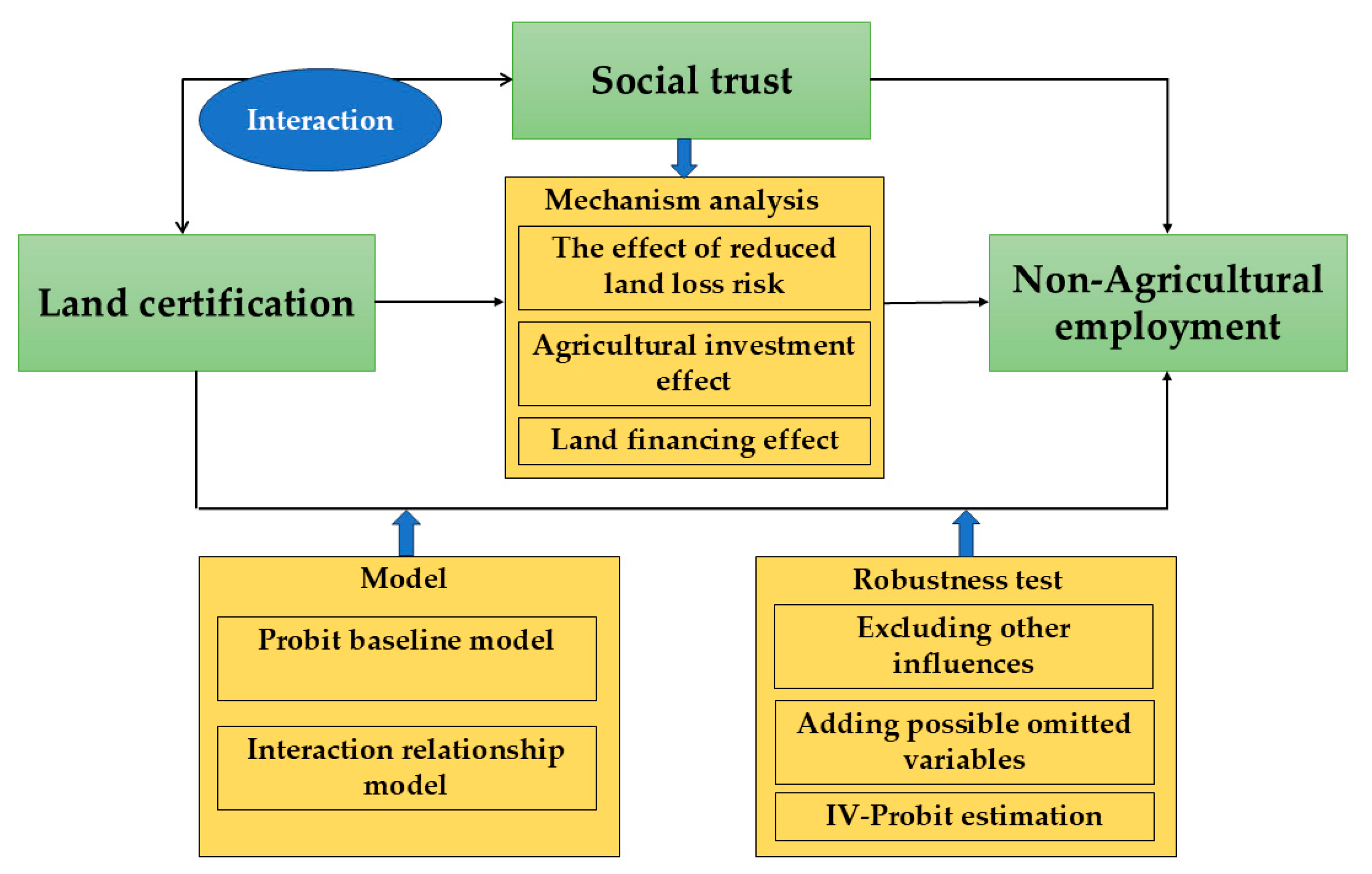

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Land Certification and Non-Agricultural Employment

2.1.1. The Land Certification Policy

2.1.2. The Relationship Between Land Certification and Non-Agricultural Employment

2.2. The Interactive Effect of Land Certification and Social Trust on Non-Agricultural Employment

2.2.1. Complementary Relationship

2.2.2. Substitutive Relationship

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Empirical Models

3.2.1. Baseline Model

3.2.2. Interaction Relationship Model

3.3. Variable Definitions and Descriptive Statistics

3.3.1. Non-Agricultural Employment (N-AE4)

3.3.2. Land Certification (LC)

3.3.3. Social Trust (ST)

3.3.4. Control Variables

3.4. Data Description

4. Results

4.1. Basic Model Regression

4.2. Robustness Test

4.2.1. Excluding Other Influences

4.2.2. Adding Possible Omitted Variables

4.2.3. IV-Probit Estimation Results

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

4.3.1. The Effect of Reduced Land Loss Risk

4.3.2. Agricultural Investment Effect

4.3.3. Land Financing Effect

4.4. Interaction Between Formal and Informal Institutions: The Interaction Effect of Land Certification and Social Trust

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| N-AE | Non-Agricultural Employment |

| LC | Land Certification |

| ST | Social Trust |

| S.D. | Standard Deviation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| N-AE | Household N-AE | Household N-AE Ratio | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Land certification | 0.1004 ** (0.0457) | 0.1646 ** (0.0745) | 0.2612 *** (0.0756) | 0.0347 ** (0.0171) |

| Social pension insurance participation | −0.1135 ** (0.0443) | −0.0496 (0.0768) | −0.3694 * (0.2230) | −0.0665 (0.0530) |

| Land certification × Social pension insurance participation | −0.0947 (0.0852) | −0.4702 * (0.2410) | −0.0660 (0.0589) | |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 8371 | 8371 | 4319 | 4319 |

| R2 | 0.3293 | 0.3295 | 0.1644 | 0.1439 |

| Regional Classification | Economic Development (Per Capita GDP) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Eastern | (2) Central | (3) Western | (4) High | (5) Medium | (6) Low | |

| Land certification | 0.0668 (0.0937) | 0.0565 (0.0642) | 0.2394 ** (0.0935) | −0.0182 (0.0821) | −0.0992 (0.0811) | 0.2954 *** (0.0680) |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 2275 | 3466 | 2630 | 2704 | 2273 | 3394 |

| R2 | 0.3619 | 0.3609 | 0.2718 | 0.3676 | 0.3658 | 0.2914 |

| Non-Agricultural Employment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Land certification | 0.1014 ** (0.0458) | 0.1014 ** (0.0458) | 0.1014 ** (0.0458) | 0.1014 ** (0.0458) | 0.1014 ** (0.0458) |

| Social pension insurance participation | −0.1124 ** (0.0444) | −0.1124 ** (0.0444) | −0.1124 ** (0.0444) | −0.1124 ** (0.0444) | −0.1124 ** (0.0444) |

| Confucian culture | 0.2079 *** (0.0673) | −0.0357 (0.0692) | 0.0188 (0.0433) | −0.0055 (0.0212) | −0.0185 (0.0189) |

| Clan culture | 0.0350 (0.0730) | 0.0350 (0.0730) | 0.0350 (0.0730) | 0.0350 (0.0730) | 0.0350 (0.0730) |

| Marketization index | 0.3151 * (0.1659) | 0.0956 (0.4938) | |||

| Population mobility ratio | 6.5703 * (3.4597) | 0.4176 (0.4630) | |||

| Urbanization rate | 2.6591 (7.8545) | ||||

| Proportion of non-Agricultural registered residents | −0.0421 (0.1244) | ||||

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 8350 | 8350 | 8350 | 8350 | 8350 |

| R2 | 0.3293 | 0.3293 | 0.3293 | 0.3293 | 0.3293 |

Appendix A.2

| 1. | China’s land property rights system has undergone a series of reforms, broadly categorized into five phases: (1) before 1952, the land reform period characterized by privatization of property rights; (2) 1953–1978, the period of mutual assistance, cooperatives, and the People’s Commune system, marked by the nationalization of land property rights; (3) 1978–2003, the phase of separating collective ownership from household contractual rights; (4) 2003–2013, during which farmland contract rights became legally transferable; and (5) from 2014 onwards, the introduction of the ‘‘three rights separation’’ framework, distinguishing collective ownership, household contract rights, and operational rights. |

| 2. | According to the scope of trust, academia usually divides trust into two categories: particularized trust (restricted trust) and social trust (generalized trust). The former refers to trust in specific individuals, namely people one knows, while the latter extends to strangers and most of society, forming through interactions with unfamiliar others [22]. |

| 3. | Unless otherwise specified (e.g., for robustness checks), we employ Probit models to estimate the relationship between land certification and both individual non-agricultural employment and household non-agricultural employment status. In contrast, we use OLS models to analyze the relationship between land certification and the household’s ratio of non-agricultural employment. |

| 4. | In the following regression tables, we abbreviate the non-agricultural employment variable as N-AE, land certification as LC, and social trust as ST to be concise and save space in the subsequent discussion. |

| 5. | The latter three provincial-level data are all sourced from the 2010 China Sixth National Population Census data. Additionally, considering that including both the marketization index and population mobility ratio simultaneously, or both the urbanization rate and the proportion of non-agricultural registered residents, could lead to severe multicollinearity, we opted to incorporate them sequentially. |

| 6. | For land transfer-in (out), “transfer-in (out)” is assigned a value of 1, and “not transferred-in (out)” is assigned a value of 0; for the time for land transfer-in (out), when the transfer-in (out) period is 1 year or indefinite, it is assigned a value of 0; when the transfer-in (out) period is 2 years or more, it is assigned a value of 1. |

| 7. | Considering that some farmers grow rice and wheat, which may affect the estimation results, we also exclude the samples of farmers who grow rice and wheat and perform regressions separately. The conclusions are robust, but are not shown due to space limitations. |

References

- Lewis, A. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labor. Manch. Sch. 1954, 22, 139–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranis, G.; Fei, J.C. A Theory of Economic Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 533–565. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro, M.P. A Model of Labor Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less Developed Countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- De Soto, H. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else; Bantam Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J. Rural Geography: Globalizing the Countryside. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 32, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D.W. Formalising Property Relations in the Developing World: The Wrong Prescription for the Wrong Malady. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byamugisha, F.F. Securing Africa’s Land for Shared Prosperity: A Program to Scale up Reforms and Investments; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Besley, T.J.; Ghatak, M. Property Rights and Economic Development. Handb. Dev. Econ. 2010, 5, 4525–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, K.; Grosjean, P.; Kontoleon, A. Land Tenure Arrangements and Rural-Urban Migration in China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Janvry, A.; Emerick, K.; Gonzalez-Navarro, M.; Sadoulet, E. Delinking Land Rights from Land Use: Certification and Migration in Mexico. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 3125–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Gu, Y.; Zhu, H. Land Tenure Arrangements and Rural-to-Urban Migration: Evidence from Implementation of China’s Rural Land Contracting Law. J. Chin. Gov. 2020, 5, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau, E.; Glachant, J.M. New Institutional Economics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.S.; Xu, X.; Gao, Y. The China Growth Miracle: The Role of the Formal and the Informal Institutions. World Econ. 2015, 38, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gërxhani, K.; Cichocki, S. Formal and Informal Institutions: Understanding the Shadow Economy in Transition Countries. J. Inst. Econ. 2023, 19, 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannicini, T.; Stella, A.; Tabellini, G.; Troiano, U. Social Capital and Political Accountability. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2013, 5, 222–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert-Mogiliansky, A.; Sonin, K.; Zhuravskaya, E. Are Russian Commercial Courts Biased? Evidence from a Bankruptcy Law Transplant. J. Comp. Econ. 2007, 35, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. Kinship Networks and Entrepreneurs in China’s Transitional Economy. Am. J. Sociol. 2004, 109, 1045–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helme, G.; Levitsky, S. Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda. Perspect. Politics 2004, 2, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méon, P.G.; Sekkat, K. The Formal and Informal Institutional Framework of Capital Accumulation. J. Comp. Econ. 2015, 43, 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, J. Rural Geography I: Changing Expectations and Contradictions in the Rural. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 37, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misztal, B.A. Trust in Modern Societies: The Search for the Bases of Social Order. Theory Soc. 1996, 25, 235–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society; Hamilton, G.G.; Wang, Z., Translators; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q. Urban and Rural China (Revised Edition); CITIC Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.Y.; Wang, Y.G. From Native Rural China to Urban-rural China: The Rural Transition Perspective of China Transformation. Manag. World 2018, 34, 128–146+232. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Land and Labor Allocation under Communal Tenure: Theory and Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 147, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, G.S. Property Rights and Investment Incentives: Theory and Evidence from Ghana. J. Polit. Econ. 1995, 103, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Cuadrado, F.; Poschke, M. Structural Change out of Agriculture: Labor Push versus Labor Pull. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2011, 3, 127–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L. Does the Land Certification Program Promote Rural Housing Land Transfer in China? Evidence from Household Surveys in Hubei Province. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B. The Logic and Limits of Trust; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gongbuzeren; Li, W. The Role of Market Mechanisms and Customary Institutions in Rangeland Management: A Case Study in Qinghai Tibetan Plateau. J. Nat. Resour. 2016, 10, 1637–1647. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, E.S. Studies of Independence and Conformity: I. A Minority of One against a Unanimous Majority. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1956, 70, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Zou, L.; Wang, Y. Does Culture Affect Farmer Willingness to Transfer Rural Land? Evidence from Southern Fujian, China. Land 2021, 10, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ke, R. Trust in China: A Cross-Regional Analysis. SSRN Electron. J. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Qiu, T.; Li, N. Property Rights Context, Social Trust, and Social Recognition of Land Property Rights. Jianghai Acad. J. 2016, 4, 92–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 526–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. The Heterogeneous Impact of Pension Income on Elderly Living Arrangements: Evidence from China’s New Rural Pension Scheme. J. Popul. Econ. 2018, 31, 155–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, D.R. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Contemp. Sociol. 1994, 23, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z. Confucian Ethics and Agency Costs in the Context of Globalization. Manag. World 2015, 3, 113–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yao, Y. Informal Institutions, Collective Action, and Public Investment in Rural China. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2015, 109, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cui, J.; Feng, L.; Yan, H. Does County Financial Marketization Promote High-Quality Development of Agricultural Economy? Analysis of the Mechanism of County Urbanization. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W. Social Trust, Institution, and Economic Growth: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2017, 53, 1243–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhelm, T.; Zhang, X.; Oishi, S.; Shimin, C.; Duan, D.; Lan, X.; Kitayama, S. Large-Scale Psychological Differences Within China Explained by Rice versus Wheat Agriculture. Science 2014, 344, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Luo, Y.; Teng, Y. Land Certification, Tenure Security and Off-Farm Employment: Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2024, 147, 107328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezabih, M.; Mannberg, A.; Siba, E. The Land Certification Program and Off-Farm Employment in Ethiopia; Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlerup, P.; Olsson, O.; Yanagizawa, D. Social Capital vs. Institutions in the Growth Process. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2009, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C. Combating Corruption: On the Interplay between Institutional Quality and Social Trust. J. Law Econ. 2011, 54, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, M. The Impact of Interplay between Formal and Informal Institutions on Innovation Performance: Evidence from CEECs. Eng. Econ. 2021, 32, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafouros, M.; Chandrashekar, S.P.; Aliyev, M.; Zhao, H. How Do Formal and Informal Institutions Influence Firm Profitability in Emerging Countries? J. Int. Manag. 2022, 28, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Wei, L. Persistence and Change in the Rural Land System of Contemporary China. Soc. Sci. China 2018, 35, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.A.; Dang, K.K.; Dang, V.A.; Vu, T.L. The Effects of Trust and Land Administration on Economic Outcomes: Evidence from Vietnam. Food Policy 2020, 94, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Zhang, D.; Choy, S.B.; Luo, B. The Interaction between Informal and Formal Institutions: A Case Study of Private Land Property Rights in Rural China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 72, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G. To explain or to predict? Stat. Sci. 2010, 25, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Non-Agricultural Employment (N = 3875) | Agricultural Employment (N = 4803) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | ||

| Key independent variable | Land certification | 0.6973 | 0.4595 | 0.6921 | 0.4617 |

| Individual characteristics | Gender | 0.6302 | 0.4828 | 0.4928 | 0.5000 |

| Age | 37.2150 | 11.8999 | 50.5249 | 9.8936 | |

| Age squared | 1526.5250 | 941.6271 | 2650.6260 | 931.4842 | |

| Marital status | 0.7143 | 0.4518 | 0.9271 | 0.2600 | |

| Education | 3.3502 | 1.4063 | 2.3881 | 0.8990 | |

| Health | 3.7316 | 0.9380 | 3.1924 | 1.0320 | |

| Household characteristics | Family size | 4.6919 | 1.6956 | 4.0729 | 1.7972 |

| Proportion of elderly (75+) | 0.0316 | 0.0855 | 0.0337 | 0.0943 | |

| Proportion of children (6−) | 0.0592 | 0.1020 | 0.0506 | 0.0996 | |

| Family total assets | 12.3359 | 1.3973 | 11.8103 | 1.3837 | |

| Village characteristics | Per capita cultivated land area | 1.6833 | 2.6537 | 2.2926 | 3.2423 |

| Per capita income | 8.8227 | 0.7121 | 8.6700 | 0.7620 | |

| Proportion of economic crops | 34.3415 | 32.6719 | 35.7551 | 32.7432 | |

| External labor force proportion | 0.2194 | 0.1599 | 0.2117 | 0.1517 | |

| Roads to the county center | 1.8010 | 0.8696 | 1.6750 | 0.8262 | |

| Number of land expropriation times | 0.1272 | 0.4312 | 0.1094 | 0.4362 | |

| (1) N-AE | (2) N-AE | (3) N-AE | (4) N-AE | (5) Household N-AE | (6) Household N-AE Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land certification | 0.0914 ** (0.0391) | 0.0985 ** (0.0451) | 0.0898 * (0.0483) | 0.0227 * (0.0120) | 0.1468 *** (0.0486) | 0.0187 * (0.0114) |

| Gender | 0.3480 *** (0.0320) | 0.3386 *** (0.0349) | 0.0971 *** (0.0084) | |||

| Age | −0.0387 *** (0.0135) | −0.0360 ** (0.0139) | −0.0147 *** (0.0034) | |||

| Age squared | −0.0002 (0.0002) | −0.0002 (0.0002) | −0.0000 (0.0000) | |||

| Marital status | −0.2075 *** (0.0661) | −0.1202 (0.0766) | −0.0353 ** (0.0173) | |||

| Education | 0.2160 *** (0.0206) | 0.2112 *** (0.0230) | 0.0495 *** (0.0046) | |||

| Health | 0.0816 *** (0.0186) | 0.0825 *** (0.0206) | −0.0229 *** (0.0050) | |||

| Family size | 0.0350 ** (0.0152) | −0.0019 (0.0158) | 0.0114 *** (0.0040) | 0.3282 *** (0.0186) | 0.0373 *** (0.0032) | |

| Proportion of elderly (75+) | −0.4681 ** (0.2049) | −0.5092 ** (0.2244) | −0.1504 *** (0.0564) | −1.0520 *** (0.2036) | −0.0916 * (0.0520) | |

| Proportion of children (6−) | −0.7533 *** (0.2233) | −0.6336 *** (0.2371) | −0.1910 *** (0.0588) | −1.4866 *** (0.2611) | −0.2376 *** (0.0454) | |

| Family total assets | 0.0703 *** (0.0166) | 0.0953 *** (0.0178) | 0.0183 *** (0.0043) | 0.1403 *** (0.0169) | 0.0362 *** (0.0039) | |

| Per capita cultivated land area | −0.0253 (0.0173) | −0.0229 (0.0171) | −0.0069 * (0.0043) | −0.0218 (0.0164) | −0.0058 * (0.0031) | |

| Per capita income | 0.1252 *** (0.0473) | 0.1444 ** (0.0564) | 0.0363 *** (0.0117) | 0.1208 *** (0.0415) | 0.0217 ** (0.0103) | |

| Proportion of economic crops | −0.0032 *** (0.0010) | −0.0030 *** (0.0010) | −0.0009 *** (0.0003) | −0.0024 ** (0.0009) | −0.0007 *** (0.0002) | |

| External labor force proportion | 0.3797 * (0.2077) | 0.3051 (0.2164) | 0.0981 * (0.0542) | 0.3021 (0.1919) | 0.0341 (0.0480) | |

| Roads to the county center | 0.0519 (0.0377) | 0.0740 * (0.0401) | 0.0112 (0.0100) | 0.0175 (0.0361) | 0.0132 (0.0087) | |

| Number of land expropriation times | 0.0712 (0.0473) | 0.0625 (0.0514) | 0.0187 (0.0136) | −0.0660 (0.0545) | −0.0002 (0.0113) | |

| Constant | 0.7642 *** (0.2063) | 0.1658 (0.5574) | −0.5168 (0.6010) | 0.6638 *** (0.1412) | −2.7019 *** (0.4956) | −0.1537 (0.1103) |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 8678 | 8588 | 7204 | 8588 | 4319 | 4319 |

| R2 | 0.0421 | 0.3317 | 0.2954 | 0.3800 | 0.1594 | 0.1406 |

| N-AE | Household N-AE | Household N-AE Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Land certification | 0.0985 ** (0.0451) | 0.0997 ** (0.0453) | 0.1014 ** (0.0458) | 0.1476 *** (0.0493) | 0.0191 * (0.0114) |

| Confucian culture | 0.2167 *** (0.0645) | 0.2079 *** (0.0673) | 0.1819 ** (0.0727) | 0.0411 *** (0.0153) | |

| Clan culture | 0.0287 (0.0717) | 0.0350 (0.0730) | 0.1242 * (0.0643) | 0.0040 (0.0168) | |

| Social pension insurance participation | −0.1124 ** (0.0444) | −0.7110 *** (0.1464) | −0.1140 *** (0.0337) | ||

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 8588 | 8567 | 8350 | 4309 | 4309 |

| R2 | 0.3317 | 0.3317 | 0.3293 | 0.1646 | 0.1432 |

| Benchmark Regression | Correlation Test | Instrumental Variable Estimation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) N-AE | (2) N-AE | (3) Household N-AE Ratio | (4) N-AE | (5) Household N-AE Ratio | |

| Land certification | 0.0985 ** (0.0451) | 0.2916 ** (0.1295) | 0.0740 * (0.0393) | ||

| Village land certification rate | 3.0561 *** (0.0866) | 2.1818 *** (0.0986) | |||

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 8588 | 8349 | 4304 | 8349 | 4304 |

| R2 | 0.3317 | 0.2658 | 0.1973 | —— | 0.1372 |

| A | (1a) Perception of Risk of Losing Land | (2a) Land Transfer-out | (3a) The Time for Land Transfer-out | (4a) Land Financing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land certification | 0.3074 *** (0.0630) | −0.0303 (0.0685) | 0.3026 * (0.1662) | 0.2684 * (0.1527) |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 7889 | 8349 | 1191 | 6059 |

| R2 | 0.0531 | 0.0816 | 0.1609 | 0.2129 |

| B | (1b) Short-Term Agricultural Investment | (2b) Land Transfer-in | (3b) The Time for Land Transfer-in | (4b) Agricultural Machinery Value |

| Land certification | −0.0532 (0.0558) | −0.1617 *** (0.0562) | 0.0761 (0.1491) | 0.2440 (0.1851) |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 6440 | 8350 | 1470 | 7598 |

| R2 | 0.3771 | 0.0676 | 0.1207 | 0.2077 |

|

(1) Individual Social Trust |

(2) Village-Level Social Trust |

(3) County-Level Social Trust | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land certification | 0.2685 *** (0.0911) | 0.5386 ** (0.2409) | 0.7774 *** (0.2633) |

| Social trust | 0.0781 ** (0.0361) | 0.2427 ** (0.1213) | 0.4436 *** (0.1374) |

| Land certification × Social trust | −0.0864 ** (0.0426) | −0.2282 * (0.1270) | −0.3531 ** (0.1369) |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 8308 | 8350 | 8350 |

| R2 | 0.3294 | 0.3300 | 0.3310 |

| N-AE | Household N-AE | Household N-AE Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Rice | (2) Wheat | (3) Rice | (4) Wheat | (5) Rice | (6) Wheat | |

| Land certification | 0.2017 ** (0.0866) | −0.0093 (0.0975) | 0.2403 *** (0.0815) | −0.1167 (0.1143) | 0.0476 *** (0.0177) | −0.0052 (0.0226) |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Fixed effect | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 2953 | 1966 | 1454 | 990 | 1456 | 994 |

| R2 | 0.3416 | 0.3876 | 0.1889 | 0.2273 | 0.1635 | 0.1621 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, B.; Pu, Y. Land Property Rights, Social Trust, and Non-Agricultural Employment: An Interactive Study of Formal and Informal Institutions in China. Land 2025, 14, 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030613

Yuan B, Pu Y. Land Property Rights, Social Trust, and Non-Agricultural Employment: An Interactive Study of Formal and Informal Institutions in China. Land. 2025; 14(3):613. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030613

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Bohui, and Yanping Pu. 2025. "Land Property Rights, Social Trust, and Non-Agricultural Employment: An Interactive Study of Formal and Informal Institutions in China" Land 14, no. 3: 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030613

APA StyleYuan, B., & Pu, Y. (2025). Land Property Rights, Social Trust, and Non-Agricultural Employment: An Interactive Study of Formal and Informal Institutions in China. Land, 14(3), 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030613