Abstract

Angling tourism is becoming increasingly important at Central Europe’s largest lowland reservoir, Lake Tisza. The lake, created in the 1970s, covers 127 km2 and has been increasingly used for recreational and nature conservation purposes recently. This study seeks to identify anglers’ site selection preferences at Lake Tisza, considering hydrological and ecological aspects, in support of sustainable site management. In order to achieve this, an in-person questionnaire survey was carried out covering the whole area during springtime 2024. During the survey period, a total of 224 anglers provided answers about their preferred location and recreational characteristics. Data processing was carried out using SPSS 26 and ESRI ArcGIS version 10.4.1. Based on the created catchment area map, it was found that a significant proportion (74%) of anglers arrive from within a 50 km radius, but the lake also has appeal outside the country. A total of 53.1% of respondents visit the lake several times per month, typically for fishing purposes. In addition, cycling, walking and picnicking are popular recreational activities among anglers. The respondents considering different landscapes (pictures showed by the interviewers) for angling prefer shaded areas with vegetation and a narrow view of the wide expanse of water (62%). The results of the open-ended questions indicate that site selection is primarily based on the existence of a shadow (49.5%), and suitability for fishing is only the second aspect (40.6%). Our study also highlighted the international trend that anglers are more interested in leisure activities in a green environment. In addition, the results have practical significance for more successful recreation planning and sustainable site management.

1. Introduction

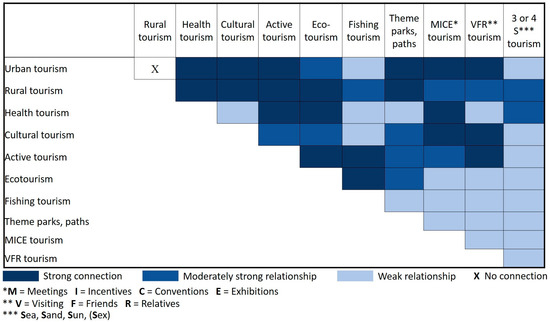

1.1. General Characteristics of Angling Tourism

Recreational fishing is a significant tourism activity, and despite being characterized by high participation rates and being an important economic activity, especially in coastal, lake and river areas, relatively little research is devoted to it [1]. For example, the FAO estimated the global non-market value of recreational fishing in inland waters at USD 65–79 billion in 2018 [2]. Fishing is a highly popular recreational activity in many countries [3]. In Europe, the number of anglers fishing in lakes and rivers is very significant in the Scandinavian countries, in Poland and in the United Kingdom [4]. In Norway, for example, 32% of the population are members of an anglers’ association. Angling tourism alone can be a market-leading type of tourism, but it also has a synergistic relationship with other products, which further strengthens its positive position. Anglers and their companions can come into contact with many other tourist products. There is a strong synergy between active tourism and ecotourism and moderately strong synergy with rural tourism; furthermore, it is connected to the tourism product shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Synergic connections of angler tourism with other tourism products (source: own editing based on Michalkó, 2011 [5]).

The literature on angling tourism is rich mainly in Swedish, Finnish, Polish, German, US and Canadian examples [6,7,8,9,10,11]. A significant body of literature deals with the attitudes of anglers. Several studies have found that the experience of harvest is more important than the prey itself [12,13,14,15]. The trend of recent years has been to increase the acceptance of catch-and-release (C&R) and size limitation fishing techniques aiming at ecological balance [16].

More recently, the majority of studies have focused on ecological sustainability and environmentally friendly angling because some experts see worrying phenomena regarding the future of this type of recreation [1,17]. However, certain research projects [17,18,19,20] have found that the sustainability of fishing sites in nature reserves is provided by creating protected shorelines.

1.2. Trends in Angling Tourism in Hungary

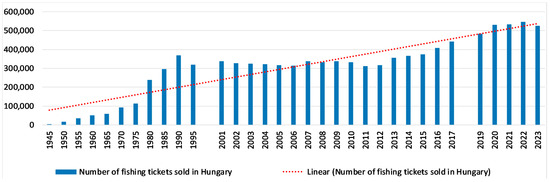

In Hungary, a continuous increase in the number of people buying annual fishing tickets since the middle of the 20th century can be observed. The unbroken rise lasted until the regime change, followed by almost 20–25 years of stagnation (Figure 2). From 2013 onwards, there has been a clear increase; infrastructural conditions have improved, and the number of fishing locations available has increased dramatically. In addition to fishing sites along rivers, many former rock, sand and gravel pits have been converted into fishing lakes, but new lakes (public and private) have also been added [21].

Figure 2.

Number of fishing tickets sold in Hungary (source: edited based on Raffay, 2022 [22], and data of PMO, 2024 [23]).

Figure 2 shows that 2022 was an outstanding year in terms of the number of anglers who purchased state fishing tickets. An even more dynamic increase can be seen in the number of registered anglers; in 2023, it exceeded 940 thousand (including those who bought so-called tourist fishing tickets), meaning that about 8% of the population of Hungary regularly fishes. With this proportion, Hungary is close to England, the Netherlands and France, thus positioning among the leaders in Europe [23]. There are several reasons for the outstandingly high value in Hungary, among which the conscious organizational development of MOHOSZ (Hungarian National Fishing Association) should be highlighted. The result is better tracked ticket sales. The cessation of commercial fishing (Act 2013/CII) may have had an indirect effect, but several successful domestic initiatives have also led to an increase in the number of anglers. For example, international fishing competitions enrich the domestic market (e.g., the International Balaton Carp Cup, IBCC). Finally, we should not forget that in 2020 the restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic affected domestic tourism less, and fishing was also one of the safest forms of leisure time [22].

1.3. Angling Tourism in the Case of Lake Tisza

In 1975 the Central Tisza Regional Management Committee established a recreation resort in the area of the Kisköre dam opened in 1973, with the aim of reducing overcrowding at Lake Balaton [24]. The unique image of the resort area began to take shape in the 1980s, relying on the different features of the surrounding settlements (14 settlements). Based on this, water sports—mainly fishing—were the main elements on offer in Tiszafüred and Kisköre, while swimming and sailing were the main elements in Abádszalók. By the end of the 1980s, marketing work promoting Lake Tisza also started [25]. The pace of development was slowed down by the burden of the debt crisis, with the exception of angling tourism.

From 2004, after joining the European Union, the number of attractions and products that made Lake Tisza attractive increased as a result of tender opportunities. Products include waterfront holidays, angling tourism, ecotourism, cycling tourism, rural tourism, gastro tourism, youth tourism, event and conference tourism, cultural tourism and health tourism [26]. Thanks to its spatially and temporally variable natural conditions [27], Lake Tisza offers the possibility to use different angling methods, almost all year round, which gives it a competitive advantage over Lake Balaton, for example. Today, angling tourism is characterized by a large market share at Lake Tisza, the second tourist segment targeted by local governments after cycling tourism [28]. The increasingly significant active tourism developments have a multifaceted impact on angling tourism, from platform infrastructure development that is beneficial for them to conflicts arising from common use.

Angling tourism is an essential element of tourism around Lake Tisza not only because of its season-lengthening effect but also because of its role in branding. It is part of the products that determine the USP (Unique Selling Proposition) of the area, thereby generating a beneficial effect on the popularity of the area [29].

At Lake Tisza, an activity closely related to fishing is backcountry camping [30] (overnight stay in an undesignated place, without developed infrastructure, with own equipment). There are several reasons for this, from the desire for successful fishing to good company [31]. Growing interest [27,30] also comes with increasing load, which is an urgent visitor management task for wetlands.

The appropriate design of fishing areas (location, area, etc.) is a very important site management tool with which visitors can enjoy the experience so that the natural values of the area are also sustained. The conscious application of this is important at one of the most popular fishing sites of Hungary, Lake Tisza, as well. Successful application depends on how well the area, on the one hand, and the visitors, on the other hand, are known.

Lake Tisza is an artificial lake that is the largest lowland water reservoir in Central Europe and the second largest lake in Hungary. In addition to water management and energy production, the lake now performs both recreational and nature conservation functions. Thanks to development and marketing, the number of visitors is increasing year by year, which means an increasing environmental burden. Therefore, multi-faceted research of this destination with its unique landscape character is indispensable.

1.4. Landscape History

The main river of the Great Hungarian Plain in the middle of the Carpathian Basin, the Tisza, was regulated in the second half of the 19th century, and, as a result, the marshland created by floods was reduced to one-tenth of its former extent [32]. Since rainfall in the central part of the Great Hungarian Plain does not reach 500 mm [33], a canal network of several hundred km was established in the first half of the 20th century for irrigation in order to mitigate the effects of frequent droughts and thus help arable farming [34]. Also, from the middle of the 20th century, the country’s energy demand increased. Between 1973 and 1980, a 30 km long and 3–6 km wide lake was formed above the Kisköre dam opened in 1973, which was first named Kisköre Reservoir, then, from 1988, Lake Tisza.

The utilization of the water of Lake Tisza has changed fundamentally over the past 40 years. The initial priority of irrigation water and energy supply was replaced by recreation, which was initially strongly related to fishing; the other perspective was nature conservation. The proportion of arable land in the region has been steadily decreasing since the 1990s [35].

With the formation of Lake Tisza, the area of wetlands that shrunk during the river regulations in the 19th century increased again, and the former semi-natural ecosystem was partially regenerated. The extensive reservoir provides a feeding and resting place for migratory birds in autumn and spring, and the local bird life is also rich. The entire area of the lake is a Natura 2000 area of European Community importance, managed by the Hortobágy National Park Directorate. Since 1979, its northern part has been a Wetland of International Importance, the so-called Ramsar area, and it is also an important part of the National Ecological Network. It was declared a nature reserve in 1972 and has been managed as a National Park since 1993.

Our research work regarding Lake Tisza has a history of more than 10 years [36,37,38,39]. Our investigations have always focused on the relationship between tourism and nature conservation [40]. In recent years, we have focused on analyzing the environmental impact of fishing [31]. In addition, partly with GIS tools, we began to survey land-use mosaicism, landscape diversity and typical landscape character types in detail [27].

The aim of this study is, on the one hand, to give an overview of the relationship between the landscape history of Lake Tisza, its ecological features and the development of angling tourism. On the other hand, we would like to present the results of a questionnaire survey conducted among anglers at Lake Tisza. The survey was carried out in order to help the managers of the area, who are also responsible for the development of the fishing sites, to manage sustainable angling tourism.

The questionnaire examined how anglers spend their time, the landscape characteristics of the sites they preferred and the environmental–landscape characteristics that contributed to the selection of the sites. During our questionnaire survey, we paid special attention to presenting locations with diverse landscape character to our respondents and assessing what kind of character (mosaics) they prefer for recreational purposes. Our hypothesis is that anglers visiting Lake Tisza prefer sites with natural landscape characteristics and that infrastructure is not important at all at a given fishing site (e.g., platform).

The novelty of our research lies in the fact that no similar landscape character preference survey has been conducted among anglers in Hungary before; therefore, our results may be of international interest. It also highlights the power of mosaicism in an artificially designed destination with diverse landscape features. Moreover, the results help site managers implement sustainable site management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Outline of the Study Area

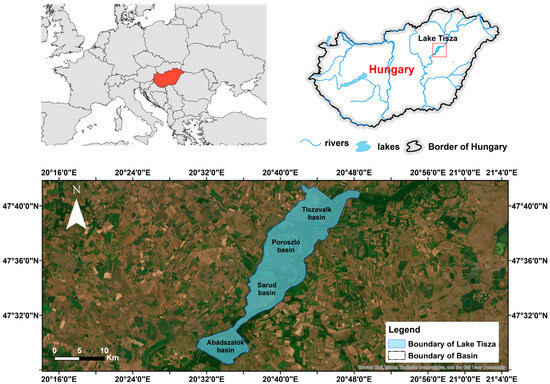

Lake Tisza is the second largest lake (and the largest lowland water reservoir) in Hungary with a water surface of 127 km2. Due to the establishment of extensive built-up areas following embanking (new residential areas, roads and agricultural buildings in the outskirts), only a lake with irregular shape was possible to establish. Considering topography, the lake can be divided into 4 sub-basins (Figure 3). The hydrodynamical, water quality, ecological and landscape conditions of the sub-basins differ from each other in many respects [27].

Figure 3.

Location and sub-basins of Lake Tisza (source: [27]).

The water level in the lake is regulated seasonally and is high in spring and summer and lower in autumn and winter. The main reason for setting the low water level in winter is that the ice formed in winter does not damage the dam or various technical facilities (lock gates, ports, etc.). From November to March, 43 km2 of the 127 km2 is temporarily dry. Due to the significant fluctuation in the area covered by water, the seasonal dynamics of vegetation again resemble the natural conditions before river regulation [41].

Woody vegetation can be found almost everywhere along the lakeshore, mostly planted poplar and willows. In some places, forming small patches of forest, a more complex woody ecosystem has emerged, with maple, elm and ash species. A total of 42% of the open water surface is covered by floating plant species (Potamogeton sp., Myriophyllum spicata, Salvinia natans, Trapa natans, etc.), despite the regular thinning of these plants, the proportion of open water surface decreases. Due to the spatial and temporal variability of water supply, Lake Tisza is characterized by a mosaic habitat pattern [27] (Photo 1).

Photo 1.

Mosaic ecological landscape structure of Lake Tisza (P.C.).

Ecological mosaicism alone increases the landscape attractiveness of the lake, and different habitat types allow for different tourist utilization [42]. The lake is surrounded by a continuous embankment with a narrow road (Photo 2).

Photo 2.

The embankment surrounding the lake and the road on it (P.C).

2.2. Mosaic Recreational Land Use of Lake Tisza

Lake Tisza and its immediate surroundings were declared a resort area in 1975, partly to reduce the overloading and crowdedness of Lake Balaton, the top lake resort in Hungary. The changing habit of the reservoir in space and time makes the area a unique destination, based on which the Tourism Development Concept completed in 1997 primarily supported ecotourism. The ecological approach to regional development was helped by the fact that the interventions were controlled by the Hortobágy National Park Directorate from the very beginning.

According to the morphological and hydrological characteristics of the reservoir, the so-called zonation land use system of the lake was elaborated, according to which different types of recreation are allowed in the 4 well-separated lake basins (see Figure 3) from N to S (in the direction of flow) [27]. Apart from the Tiszavalk Basin, fishing is possible in almost the entire area of the reservoir:

- In the Tiszavalk Basin, there are closed and strictly closed habitats and bird protection reserves where maintaining a close-to-natural state is given absolute priority.

- The Poroszló Basin is a nature conservation and ecotourism area where so-called ”soft” water sports and fishing are allowed.

- The Sarud area is a recreational and fishing area where certain conservation interests have to be also taken into account.

- Finally, in the area of the most separated Abádszalók Basin, priority is given to development for tourism, and the area is open primarily for water sports and fishing.

Potential recreational opportunities are mostly influenced by water depth and vegetation. For bathing, shallow water without floating vegetation is the best. For canoeing, sailboat, jet ski and speedboat trips, deeper but also vegetation-free areas offer the best options. Water “trails” for canoe and boat access are regularly established in areas overgrown with seaweed and water caltrop.

2.3. Applied Methods

The questionnaire survey was conducted in the spring of 2024 among anglers along the shores of Lake Tisza with the help of interviewers. During the survey, the entire area of the shore was covered thanks to the large number of interviewers. Our preliminary goal for the sample size was 180–200 because we thought that this number of respondents would give us a chance to conduct more thorough analysis. Personal questionnaires had a positive impact on the willingness to respond and the evaluability of answers.

Although our survey was conducted in spring, the season did not significantly influence the respondents’ location preferences. The choice of spring was primarily made to avoid the peak season when the lake is visited by other types of tourists (e.g., cyclists and beachgoers), thereby ensuring that we could focus specifically on anglers. The analysis of the attraction district revealed that most anglers came from the surrounding municipalities and were regular visitors to the lake. While their fishing locations may vary throughout the year, the respondents based their answers on their overall fishing experience.

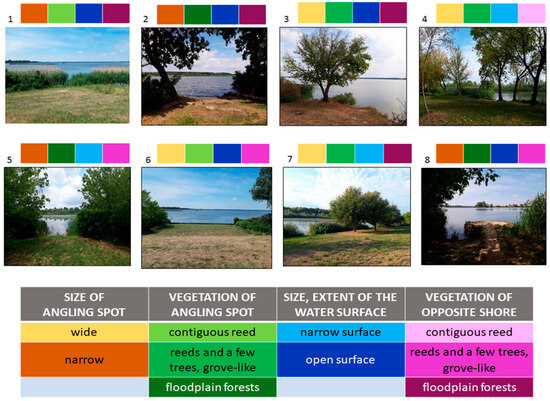

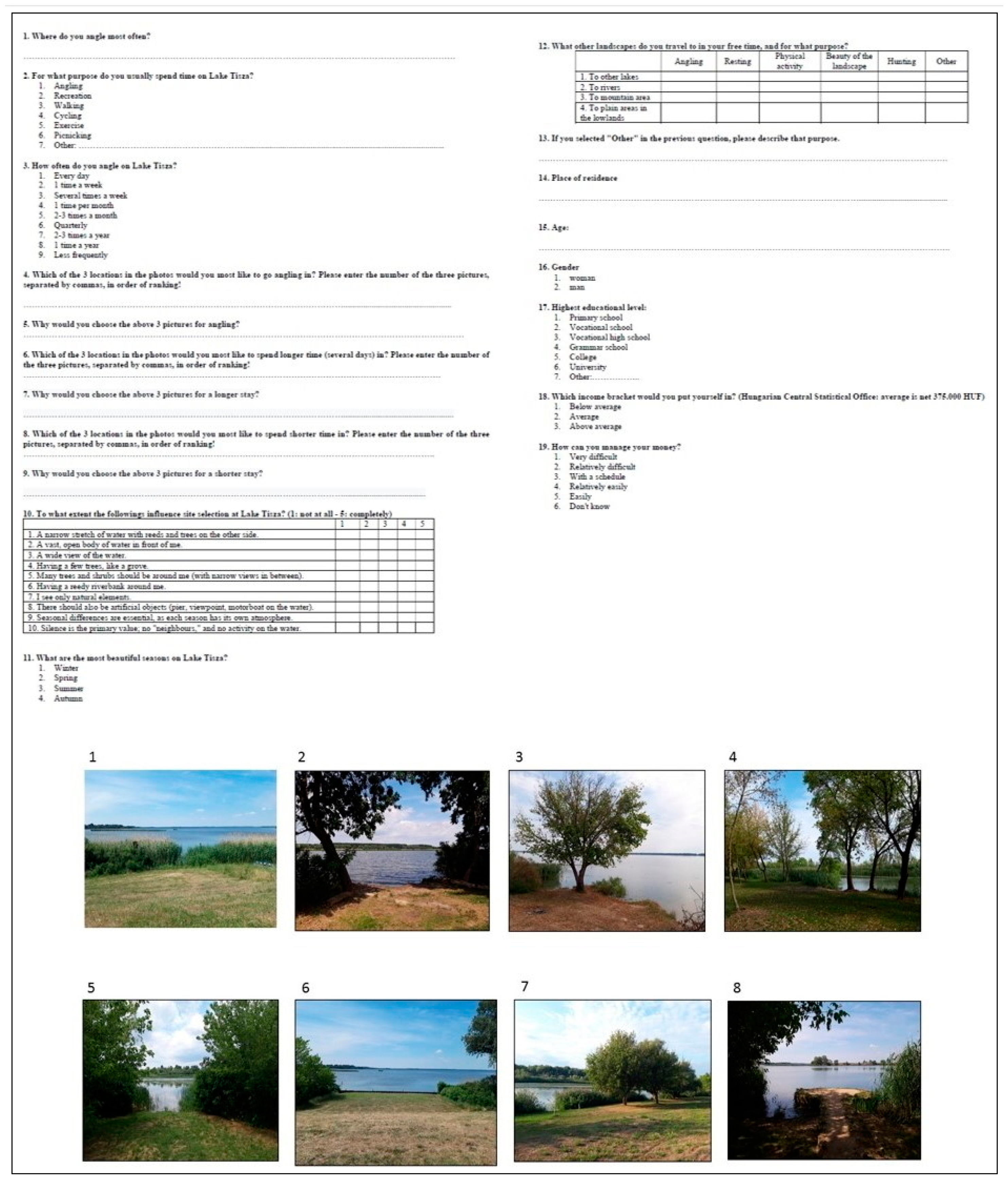

During the survey, the questionnaire was supplemented by a montage consisting of 8 photos (Appendix A). Based on foreground and background size, openness and vegetation characteristics, 36 potential scenery categories can be distinguished. The important aspects of views and the principle of selection can be seen in Appendix B. From these, 8 scenery categories (which can be seen from the shore) were selected (Figure 4) based on our studies about natural mosaic conditions [27] and field experience. (Many of the potential landscapes do not exist or are not particularly characteristic of the area.)

Figure 4.

Site types at Lake Tisza (as an illustration of the questionnaire survey) and the typical landscape characters.

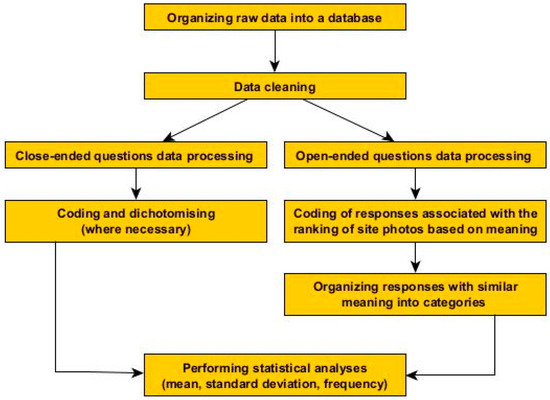

The questionnaire contained 19 questions (see Appendix C), which, in addition to sociodemographic indicators, examined the purpose of the visit, landscape preferences of anglers for recreation, nature, frequency and seasonal preferences of anglers spending time at Lake Tisza and factors influencing site selection. In addition, the preferred short- and long-stay locations for fishing were chosen by showing the respondents the pictures mentioned in the paragraph above [43], each with different and unique landscape characteristics, from which they could select and rank three. The answers were dichotomized during data encoding (1—selected; 0 not selected) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Main steps of data processing.

Several landscape metric indices are now used to describe and analyze a landscape [44,45]. In addition, one method is used frequently in landscape character research when landscape preference is presented through photographs showing typical types of landscape [46,47,48,49,50,51]. This method complies with participatory planning, which is considered one of the basic principles of modern landscape research and landscape design and thus satisfies the requirements of the European Landscape Convention.

In addition, the environmental characteristics contributing to site selection at Lake Tisza are based on ten statements and answers given on a five-step Likert scale (1—not at all; 5—completely). The processing and statistical analysis of the questionnaire data were carried out using the software SPSS 26.

3. Results

A total of 224 questionnaires were completed (N = 224). In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, the largest proportion of our respondents had vocational secondary school qualifications (65—29%), and the largest age group was 51–60 years old (54—24.1%). In terms of gender, the respondents were mostly men (197 people—87.9%), and 64.38% were living in towns.

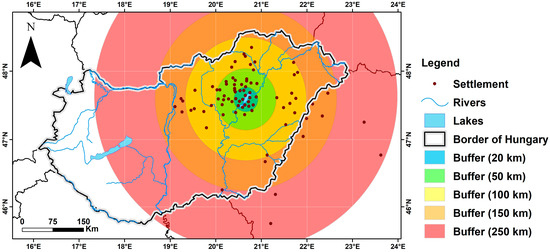

The respondents mainly came from within a radius of 50 km (61.6%), but the attraction district extends over the border as well, over a distance of 250 km (Figure 6). Similarly to our previous research [36,37], the proportion of returning anglers remains very high (89% in this survey).

Figure 6.

Attraction district based on the place of residence of the respondents.

Since respondents could pick several options for the question “For what purpose do you usually spend time at Lake Tisza?”, “only angling” (52.5%) was followed by “recreation” (47.5%). The category of recreation includes walking, cycling, picnic and physical exercise.

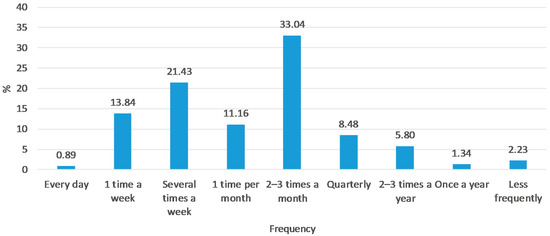

The largest proportion of the respondents visit the study area 2–3 times a month (33.04%), followed by those who visit several times a week (20.09%) (Figure 7). The same frequency applies for angling and recreational visitors. A total of 32.9% of anglers visit the lake 2–3 times a month, while 21.3% visit it several times a week. For those who come to relax, the proportions are 32.5% and 22.5%, respectively. Regarding the question “What are the most beautiful seasons at Lake Tisza?” most people (67.4%) chose spring. This was followed by autumn (56.7%), then summer (48.2%) and winter (17.4%).

Figure 7.

Frequency of visits among anglers.

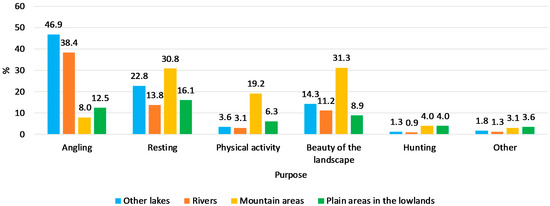

In order to assess the recreational habits of our respondents belonging to a specific landscape type, we asked the following question, during which they could pick several answers: “What other landscapes do you travel to in your free time, and for what purpose?” (Figure 8). Unsurprisingly, 46.9% of anglers go fishing to other lakes, and 38.4% to rivers. Some anglers also prefer lowland plains (12.5%) and mountainous areas (8%) for fishing. Since 82.4% of the area of Hungary is lowland with altitudes less than 200 m [52], vertically more dissected landscapes are valued. Therefore, our respondents consider mountain areas most attractive because of the beauty of the landscape (31.3%) and also value them for leisure (30.8%) and physical activity (19.2%) (Figure 8). The beauty of the landscape is a subjective element, but our goal was to assess which type of landscape is considered the “most beautiful”. Based on the data, we conclude that since most of our angler respondents come from an attraction district of 50 km (Figure 6), they are accustomed to similar landscapes to the lakes (e.g., Lake Tisza) and rivers (e.g., Tisza river and its tributaries) of the Great Hungarian Plain. Since they spend most of their life in this landscape, they consider the mountainous landscape, which has completely different characteristics, much more beautiful.

Figure 8.

Other landscape preferences of anglers for recreation (%).

We also examined the specific landscape characteristics and significance of our study area. We assessed how attractive the locations of Lake Tisza with different and specific landscape characteristics are for short or longer fishing stays. The anglers were shown eight images, from which they could select and rank three, and after data coding and clearing, we dichotomized the answers to the questions (0: was not selected; 1: selected).

For fishing, 62% (139 respondents) selected image 2 (first place: 9.4%, second place: 14.7% and third place: 37.9%). The image with the highest number of first place rankings was the eighth (28.1%). In the case of both pictures (2 and 8), there is a narrow view of the water from the fishing site, lined with vegetation giving a shade (gallery forest, reeds). The wide water is closed in the distance by a gallery forest (image 2) and some reeds peppered with trees (image 8).

For short stays (maximum 1–2 h), most people selected image 4 (first place: 8.5%, second place: 21.4% and third place: 12.1%). This image depicted a grove-like wide fishing site with one or two sparsely standing trees and a narrow water surface. It should be emphasized that the proportion of missing data in this question was very high (45 respondents—20.1%), which confirms that most of our respondents (anglers) do not visit here for a short time, so they could not justify the exact reason for their image selection. The image with the highest number of first place rankings was again the eighth (21.4%).

For longer stays, most respondents, 57.2%, selected image 2 as well (first place: 11.6%, second place: 14.3% and third place: 31.3%), and the image with the highest number of first place rankings was again the eighth, similarly to angling (23.2%).

In the case of the sites selected for short or long fishing stays from the images provided (Figure 4), respondents had to justify the decision in their own words (unlimited choices for three chosen pictures). A total of 377 responses were received for fishing, 314 for longer stays and only 219 responses for short stays.

In addition to ranking, they had to justify the decision in their own words by means of an open-ended response. The generated categories and their corresponding typical responses are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Categories established based on responses to open-ended questions and the most frequent typical mentions.

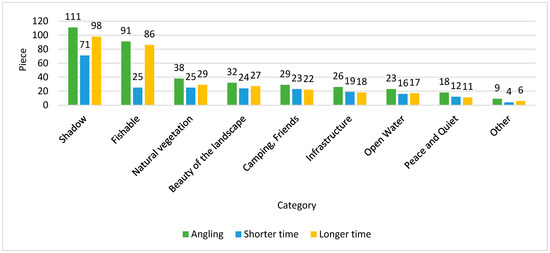

Since our respondents generally came for fishing, the reasons were mostly associated with suitability for fishing (e.g., presence of fish, vegetation that does not prevent casting and local knowledge) (91 mentions); however, natural vegetation (38 mentions) and shade (111 mentions) play a very important role in the decision. Spending a short time without fishing (e.g., relaxing while cycling and picnicking) received the smallest number of mentions, as this is less typical of the respondents, and many of them could not choose a picture based on their own experience. However, still shade was mentioned most frequently (71), followed by fishing (25), as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Factors influencing the selection of a site.

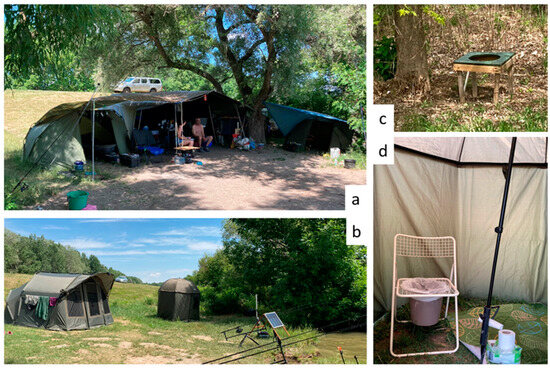

In the case of stays for several days, then in addition to the shade (86 mentions), it is a decisive feature whether several tents can fit at the site (98 mentions) (Figure 9) and whether it is suitable for wild camping. In such cases, anglers often set up several tents in addition to the sleeping tent, for example, for toilets and equipment (Photo 3). Therefore, the most important part of the infrastructure for them is the road on the embankment (18 mentions) (due to the large amount of equipment and luggage), but beyond that, the platform and the “tidy environment” were mentioned infrequently (e.g., cleared of vegetation and free of mud).

Photo 3.

Self-built campsite by anglers coming for a longer stay (a,b): tents for sleeping, kitchen, storage and bathing; (c,d): toilet equipment.

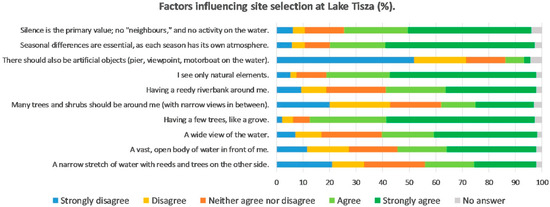

After the open-ended question, anglers had to rate the criteria given by us on a five-step Likert scale (1—not at all; 5—completely) according to how much they played a role in site selection (Figure 10). The most important was “A few trees, in a grove-like setting”. (mean: 4.36; SD: 0.94). A total of 55.8% of the total sample fully agreed with this statement. This was followed by “I want to see only natural elements”. (mean: 4.24; SD: 1.10), with which 54.9% of the respondents agreed fully. The least important was that “There should be artificial objects (platform, viewpoint, motorboat on the water” (mean: 1.83; SD: 1.09), a statement that only 2.2% of anglers agreed fully with; 51.8% did not consider it important at all (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Distribution of answers given to the question ”To what extent the followings influence site selection at Lake Tisza?” (%).

4. Discussion

In this study, we aimed to provide an overview of the connection between landscape history, ecological characteristics and the evolution of angling tourism at Lake Tisza. In addition, the study’s main goal was to present the findings of a questionnaire survey conducted among anglers at Lake Tisza. Our findings explored the purpose of the visit of anglers, their landscape preferences for recreation, together with the nature, frequency and seasonal preferences of anglers spending time at Lake Tisza and also the factors influencing their site selection. In addition, the locations chosen for short or longer fishing stays were analyzed.

In terms of the number of anglers, national data show that the number of tickets issued has increased sharply from 2021. This trend could be detected in the case of Lake Tisza as early as 2020. In 2020, the number of days spent fishing was 30%, more than in the previous year (130,000 days) based on the reviewing of catch logbooks. Data published by Lake Tisza Sport Angling Non-profit Ltd. show that the number of annual fishing tickets remained high in 2021, 2022 and 2023, with only a slight decrease compared to 2020. The lake is advertised as a “four-season fishing site”; besides nature walks and cycling, it also offers recreation in winter. Our results partly confirm this statement, as for the question “What are the most beautiful seasons at Lake Tisza?”, most people chose spring, followed by autumn, then summer and winter. Furthermore, our results reflect the importance of angling tourism in Hungary because the respondents mainly came from within a radius of 50 km, and the majority spent their time at Lake Tisza by angling.

The mosaic landscape structure provides a unique character for Lake Tisza. For the landscape character research, we used photographs showing typical types of landscapes at Lake Tisza. The main aspects are the size of the angling spot, vegetation of the angling spot, size and extent of the water surface and vegetation of the opposite shore. In the past 10–15 years, the role of a pleasant and diverse environment, silence and closeness to nature has become increasingly important. There is ample research detailing the environmental expectations of anglers [53,54,55]. Anglers are increasingly looking for recreation, and fishing success is less important [56,57,58,59]. The demand for high-quality infrastructure equipment of fishing locations has increased, and accessibility, cleanliness and nearby hygiene equipment are increasingly important [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Anglers consider an increasing number of circumstances when choosing a location, including a favorable visual image of the area [27,61,63,64,65,66,67]. This is contradicted by research by Carruthers et al. [60] and Matsummura et al. [68], who found that the exact fishing location is chosen increasingly based on the habitat of the target fish species, as few people fish based on the idea of “whatever caught”. According to the research of Dávid et al. [36], Lake Tisza was popular in 30.9% of the cases because of peace, tranquility and silence, while anglers referred to the uniqueness of the lake in 25% of responses. The basis of all this is habitat diversity, thanks to which 38 species of fish live in Lake Tisza [69]. Our results support these trends; since the respondents came to the lake mostly for angling, the reasons were mostly associated with suitability (e.g., the presence of fish, vegetation that does not prevent casting and local knowledge). Since each fish species requires different environments, sport anglers can choose from a variety of locations; it is possible to choose between areas of open water, along the reeds, covered with seaweed and shallow or deeper water. In addition to suitability for fishing, additional recreational ecosystem services provided by vegetation play a fundamental role in site selection: the visual experience of the natural landscape and shade. Apart from the road running on the embankment, anglers at Lake Tisza do not require significant infrastructure, rather preferring the beauty of the landscape and natural elements.

Based on our results, anglers’ choice of location is mainly determined by natural elements (trees, reeds), while the development of infrastructure (e.g., moorings and motorboats) is less relevant for them. This suggests that the conservation and reconstruction of natural habitats should be a top priority for development, whether at Lake Tisza or in other angling paradises.

Our findings are parallel to the results of Valdez et al. in 2019 [43], which stated that anglers preferred the less developed, natural sites.

Our results are not entirely in line with the research of [57], which investigated German anglers. The authors found that the angling preferences of different angler types are heterogeneous. Three groups were identified: catch-oriented, nature-oriented and trophy-oriented anglers. They all have specific preferences for water quality but not for natural landscapes.

Local communities’ involvement is significant in the implementation of conservation measures. Thus, raising awareness among anglers, most of whom are local or come from neighboring municipalities, is crucial to the site management of the area. The landscape preference of the respondents and their sensitivity to natural values can be a good basis for environmental education and awareness-raising campaigns.

An important objective is also to increase the resilience of the destination. The necessary risk management strategies should be prepared to sustain nature-based tourism (e.g., water quality degradation and climate change impacts).

From a policymaking perspective, the results offer several relevant lessons for promoting nature conservation in the Lake Tisza region. The results show that a significant proportion of anglers prefer sites with a natural landscape character and are less demanding in terms of infrastructure development. This may encourage conservation policymakers to:

- Increase the protection and rehabilitation of natural habitats (e.g., reedbeds and gallery forests).

- Introduce strict rules against excessive infrastructure development (e.g., speedboat traffic and moorings) that can damage wildlife.

- Implement sustainable fish management measures.

5. Conclusions

This study has analyzed the site preferences of anglers at Lake Tisza, which were found to be primarily related to being in the shade. For most people, fishing is not only a sport but also a recreational activity. Therefore, in addition to the sports experience, rest and relaxation are part of their pastime, which they like to take place in a natural, rich, mosaic landscape. The results supported our preliminary hypothesis that anglers visiting Lake Tisza prefer sites with natural landscape characteristics and that infrastructure is not important at a given fishing site (e.g., platform).

Based on the results, we believe that further research is required to obtain a more accurate picture of the recreational habits and landscape character preferences of anglers. These research results are comparable to results presented in the international literature and can serve as a basis for time-series analyses in Hungarian terms.

The time limitations of this study should also be mentioned. Data were collected in 2024; thus, data from a different time may differ.

Nevertheless, the results may contribute to the development of destination management that is based on real demands, taking into account natural conditions and prioritizing the preservation of values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. B.B. (Borbála Benkhard), E.K. and P.C.; methodology. B.B. (Borbála Benkhard), E.K., P.C. and M.V.; software. D.B. (Dániel Balla); validation. T.M., E.K., I.F., B.B. (Beáta Babka) and R.V.; formal analysis. B.B. (Borbála Benkhard), E.K., P.C. and M.V.; investigation. B.B. (Borbála Benkhard), E.K., P.C. and M.V.; resources. B.B. (Borbála Benkhard) and M.V.; data curation. E.K., B.B. (Borbála Benkhard), M.V. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation. B.B. (Borbála Benkhard), E.K., P.C., T.M., G.S. and M.V.; writing—review and editing. B.B. (Borbála Benkhard), E.K., P.C., T.M., G.S., D.B. (Dávid Balázs), B.B. (Beáta Babka) and R.V.; visualization. B.B. (Borbála Benkhard), E.K., P.C., M.V. and D.B. (Dániel Balla); supervision. P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by the University of Debrecen Scientific Research Bridging Fund (DETKA).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Layout of the Field Questionnaire

Appendix B. The Aspects of View and Principle of Selecting Photos

| Angling Spot | View/Opposite Site | Example (Photo in the Questionnaire) * | ||

| Size | Vegetation | Water Surface | Vegetation | |

| wide (>5 × 5 m) | contiguous reeds on both side | narrow | contiguous reeds | |

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| open | contiguous reeds | 6 | ||

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| reeds and a few trees, grove-like | narrow | contiguous reeds | 4 | |

| foodplain forest | 7 | |||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| open | contiguous reeds | |||

| foodplain forest | 3 | |||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| foodplain forest | narrow | contiguous reeds | ||

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| open | contiguous reeds | |||

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| narrow (<5 m) | contiguous reeds on both side | narrow | contiguous reeds | |

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| open | contiguous reeds | 1 | ||

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| reeds and a few trees, grove-like | narrow | contiguous reeds | ||

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| open | contiguous reeds | |||

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | ||||

| foodplain forest | narrow | contiguous reeds | ||

| foodplain forest | ||||

| reeds and few trees | 5 | |||

| open | contiguous reeds | |||

| foodplain forest | 2 | |||

| reeds and few trees | 8 | |||

| * Many of the potential landscapes do not exist or are not particularly characteristic of the area. | ||||

Appendix C. Questions of Survey

- 1. Where do you angle most often? ………

- 2. For what purpose do you usually spend time at Lake Tisza?

Angling//Recreation//Walking//Cycling//Exercise//Picnicking//Other: ………

- 3. How often do you angle at Lake Tisza?

Every day//1 time a week//Several times a week//1 time per month//2–3 times a month//Quarterly//2–3 times a year//1 time a year//Less frequently

- 4. Which of the 3 locations in the photos would you like the most to go angling in? Please enter the number of the three pictures, separated by commas, in order of ranking! ………

- 5. Why would you choose the above 3 pictures for angling? ………

- 6. Which of the 3 locations in the photos would you like the most to spend longer time (several days) in? Please enter the number of the three pictures, separated by commas, in order of ranking! ………

- 7. Why would you choose the above 3 pictures for a longer stay? ………

- 8. Which of the 3 locations in the photos would you like the most to spend shorter time in? Please enter the number of the three pictures, separated by commas, in order of ranking! ………

- 9. Why would you choose the above 3 pictures for a shorter stay? ………

- 10. To what extent the followings influence site selection at Lake Tisza? (1: not at all—5: completely)

A narrow stretch of water with reeds and trees on the other side.

A vast, open body of water in front of me.

A wide view of the water.

Having a few trees, like a grove.

Many trees and shrubs should be around me (with narrow views in between).

Having a reedy riverbank around me.

I see only natural elements.

There should also be artificial objects (pier, viewpoint, motorboat on the water).

Seasonal differences are essential, as each season has its own atmosphere.

Silence is the primary value; no “neighbours”, and no activity on the water.

- 11. What are the most beautiful seasons at Lake Tisza?

Winter//Spring//Summer//Autumn

- 12. What other landscapes do you travel to in your free time, and for what purpose?

Other landscapes: To other lakes//To rivers//To mountain areas//To plain areas in the lowlands

Purposes: Angling//Resting//Physical activity//Beauty of the landscape//Hunting//Other

- 13. If you selected “Other” in the previous question, please describe that purpose. ………

- 14. Place of residence: ………

- 15. Age: ………

- 16. Gender: female//male

- 17. Highest educational level: Primary school//Vocational school//Vocational high school//Grammar school//College//University//Other: ……….

- 18. Which income bracket would you put yourself in? (Hungarian Central Statistical Office: average is net 375,000 HUF) Below average//Average//Above average

- 19. How can you manage your money? Very difficult//Relatively difficult//With a schedule//Relatively easily//Easily//Don’t know

References

- Hall, C.M. Tourism and Fishing. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 21, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Ed.) Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. In The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 978-92-5-130562-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, S.J.; Arlinghaus, R.; Johnson, B.M.; Cowx, I.G. Recreational Fisheries in Inland Waters. In Freshwater Fisheries Ecology; Craig, J.F., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 449–465. ISBN 978-1-118-39442-7. [Google Scholar]

- Furgała-Selezniow, G.; Jankun-Woźnicka, M.; Mika, M. Lake Regions under Human Pressure in the Context of Socio-Economic Transition in Central-Eastern Europe: The Case Study of Olsztyn Lakeland, Poland. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalkó, G. A turisztikai termék (the Tourism Product). In Turisztikai Terméktervezés és Fejlesztés (Design and Development of Touristic Products); University of Pécs: Pécs, Hungary, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arlinghaus, R. A Human Dimensions Approach towards Sustainable Recreational Fisheries Management; Turnshare Ltd.: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1-903343-36-4. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M.J.; Jackson-Smith, D.; Haeffner, M. Influence of Recreational Activity on Water Quality Perceptions and Concerns in Utah: A Replicated Analysis. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2018, 22, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardmore, B.; Hunt, L.M.; Haider, W.; Dorow, M.; Arlinghaus, R. Effectively Managing Angler Satisfaction in Recreational Fisheries Requires Understanding the Fish Species and the Anglers. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2015, 72, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.; Stanley, B. Water Quality and Recreational Angling Demand in Ireland. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2016, 14, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, F.D.; Arlinghaus, R.; Dieckmann, U. Erratum: Diversity and Complexity of Angler Behaviour Drive Socially Optimal Input and Output Regulations in a Bioeconomic Recreational-Fisheries Model. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2010, 67, 1897–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, R.; Matern, S.; Schafft, M.; Maday, A.; Wolter, C.; Klefoth, T.; Arlinghaus, R. Influence of Protected Riparian Areas on Habitat Structure and Biodiversity in and at Small Lakes Managed by Recreational Fisheries. Fish. Res. 2022, 256, 106476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.K.; Ditton, R.B.; Hunt, K.M. Measuring Angler Attitudes Toward Catch-Related Aspects of Fishing. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2007, 12, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.M.; Floyd, M.F.; Ditton, R.B. African-American and Anglo Anglers’ Attitudes toward the Catch-Related Aspects of Fishing. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2007, 12, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, L.M.; Camp, E.; Van Poorten, B.; Arlinghaus, R. Catch and Non-Catch-Related Determinants of Where Anglers Fish: A Review of Three Decades of Site Choice Research in Recreational Fisheries. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2019, 27, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.-O.; Ditton, R.B. Using Recreation Specialization to Understand Multi-Attribute Management Preferences. Leis. Sci. 2006, 28, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Cooke, S.J.; Lyman, J.; Policansky, D.; Schwab, A.; Suski, C.; Sutton, S.G.; Thorstad, E.B. Understanding the Complexity of Catch-and-Release in Recreational Fishing: An Integrative Synthesis of Global Knowledge from Historical, Ethical, Social, and Biological Perspectives. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2007, 15, 75–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownscombe, J.W.; Hyder, K.; Potts, W.; Wilson, K.L.; Pope, K.L.; Danylchuk, A.J.; Cooke, S.J.; Clarke, A.; Arlinghaus, R.; Post, J.R. The Future of Recreational Fisheries: Advances in Science, Monitoring, Management, and Practice. Fish. Res. 2019, 211, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Mehner, T. Determinants of Management Preferences of Recreational Anglers in Germany: Habitat Management versus Fish Stocking. Limnologica 2005, 35, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.M.; Newbold, S.C.; Gentner, B. Valuing Water Quality Changes Using a Bioeconomic Model of a Coastal Recreational Fishery. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2006, 52, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, F.D.; Allen, M.S.; Beardmore, B.; Riepe, C.; Pagel, T.; Hühn, D.; Arlinghaus, R. How Ecological Processes Shape the Outcomes of Stock Enhancement and Harvest Regulations in Recreational Fisheries. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 2033–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PecaTavak.hu—Horgászvíz Adatbázis (Database of Angling Waters). Available online: https://pecatavak.hu/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Raffay, Z. A Horgászturizmus Pozíciójának Erősítése Magyarország Turizmusában. Tur. És Vidékfejlesztési Tanulmányok 2022, 7, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Prime Minister’s Office A Nemzeti Horgászturisztikai Stratégia horgász-, horgászszervezeti és szakmai konzultációi, valamint a kormányzati szervek által tett észrevételek, módosítási javaslatok alapján 2024. Available online: https://cdn.kormany.hu/uploads/document/c/c4/c49/c49e68e0ed9f14260c1b2134119296922d39d948.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Lóránt, D.; Gábor, M.; Zoltán, B. A Tisza-tó turizmusa (Tourism of Lake Tisza); Magyar Turizmus Zrt.: Budapest, Hungary, 2008; ISBN 978-963-06-4883-7.

- Füreder, B.; Reményik, B. A Tisza-tó turizmusának fejlődése. In A Tisza-tó Turizmusa; Magyar Turizmus Zrt.: Budapest, Hungary, 2008; pp. 31–39. ISBN 978-963-06-4883-7. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, A. A Tisza-tó régió turisztikai termékkínálata (Tourism products of the Lake Tisza region). In A Tisza-tó tu$rizmusa (Tourism of Lake Tisza); Magyar Turizmus Zrt.: Budapest, Hungary, 2008; pp. 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Benkhard, B.; Csorba, P.; Mester, T.; Balla, D.; Kiss, E.; Szabó, G.; Fazekas, I.; Vass, R.; Rooien, A.; Vasvári, M. Effects of Mosaic Natural Conditions on the Tourism Management of a Lowland Water Reservoir, Lake Tisza, Hungary. Land 2023, 12, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AÖFK Tisza-tó Térségi Aktív Turisztikai Fejlesztési Program. Aktív-És Ökoturisztikai Fejlesztési Közp—AÖFK; 2024. Available online: https://aofk.hu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/tisza-to-aktiv-turisztikai-fejlesztesi-program.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Brown, A.; Djohari, N.; Stolk, P. The Final Report of the Social and Community Benefits of Angling Project, 2012nd ed.; Substance: Manchester, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-906455-02-6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Wei, A.; Liu, Y.; Xia, T. The Relationship between Perceived Risks and Campsite Selection in the COVID-19 Era. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czicze, G.; Benkhard, B.R. My tent is my fortress—Change in wilderness Camp in the area of Tisza-lake. Az én sátram az én váram—A vadkempingezés változása a Tisza-tó térségében. Acta. Carolus Robertus 2020, 10, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T.; Fiala, K.; Sipos, G.; Szatmári, G. Long-Term Hydrological Changes after Various River Regulation Measures: Are We Responsible for Flow Extremes? Hydrol. Res. 2019, 50, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezősi, G. Physical Geography of the Great Hungarian Plain. In The Physical Geography of Hungary; Geography of the Physical Environment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 195–229. ISBN 978-3-319-45182-4. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, F. Drainage Network Development in the Pannonian Basin. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2015, 64, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derts, Z.; Koncsos, L. Ecosystem Services and Land Use Zonation in the Hungarian Tisza Deep Floodplains. Pollack Period. 2012, 7, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávid, L.D.; Kóródi, M.; Puczko, L.; Vasvári, M. A Tisza-Tó Imázsa És Márkázottsága. Tur. Bull. 2010, 2010, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Benkhard, B.; Vasvári, M. A Horgászturizmus Gazdasági Hatása a Tisza-tó Térségében; 2013; Available online: https://geo.unideb.hu/sites/default/files/upload_documents/tanulmany_horgaszturizmus-gazdasagi-hatasa_0.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Vasvári, M.; Boda, J.; Dávid, L.; Bujdosó, Z. Water-Based Tourism as Reflected in Visitors to Hungary’s Lakes. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2015, 15, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Vasvári, M.; Boda, J.; Dávid, L.; Bujdosó, Z. Lakes as Destinations of Tourism: A Case Study of Balaton and Lake Tisza, Hungary. Pensee 2014, 76, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mester, T.; Benkhard, B.; Vasvári, M.; Csorba, P.; Kiss, E.; Balla, D.; Fazekas, I.; Csépes, E.; Barkat, A.; Szabó, G. Hydrochemical Assessment of the Kisköre Reservoir (Lake Tisza) and the Impacts of Water Quality on Tourism Development. Water 2023, 15, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejes, L. A Tisza-Tó Vízrendszere. Available online: https://www.kotikovizig.hu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=20:tisza-to-vizrendszere&catid=47:tisza-to-vizrendszere&Itemid=77 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Hahn, T.; Heinrup, M.; Lindborg, R. Landscape Heterogeneity Correlates with Recreational Values: A Case Study from Swedish Agricultural Landscapes and Implications for Policy. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R.X.; Drake, M.D.; Burke, C.R.; Peterson, M.N.; Serenari, C.; Howell, A. Predicting Development Preferences for Fishing Sites among Diverse Anglers. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csorba, P. Tájmetriai mérések felhasználási lehetőségei (Application possibilities of landscape metric measurements.). In Tájkutatás—Tájökológia (Landscape Research—Landscape Ecology); Meridián Alapítvány, 2008; pp. 65–72. ISBN 978-963-06-6003-7. [Google Scholar]

- Túri, Z. Studying Landscape Pattern in Great Hungarian Plain Model Areas. Antrophogenic Asp. Landsc. Transform. 2010, 6, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, F.L.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Ramos, I.L.; Surová, D.; Menezes, H. Dealing with Landscape Fuzziness in User Preference Studies: Photo-Based Questionnaires in the Mediterranean Context. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 104, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häfner, K.; Zasada, I.; Van Zanten, B.T.; Ungaro, F.; Koetse, M.; Piorr, A. Assessing Landscape Preferences: A Visual Choice Experiment in the Agricultural Region of Märkische Schweiz, Germany. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedblom, M.; Hedenås, H.; Blicharska, M.; Adler, S.; Knez, I.; Mikusiński, G.; Svensson, J.; Sandström, S.; Sandström, P.; Wardle, D.A. Landscape Perception: Linking Physical Monitoring Data to Perceived Landscape Properties. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Briegel, R.; Schüpbach, B.; Junge, X. Aesthetic Preference for a Swiss Alpine Landscape: The Impact of Different Agricultural Land-Use with Different Biodiversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 98, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Hölzler, S.; Leitinger, G.; Bacher, M.; Tappeiner, U.; Tasser, E. Can We Model the Scenic Beauty of an Alpine Landscape? Sustainability 2013, 5, 1080–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, C. Landscape Character Assessment—Guidance for England and Scotland; Countryside Agency Publications: Gloucestershire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gábris, G.; Pécsi, M.; Schweitzer, F.; Telbisz, T. Domborzat. In Kocsis K. (Főszerk.): Magyarország Nemzeti Atlasza—Természeti Környezet; HUN-REN Csillagászati és Földtudományi Kutatóközpont: Budapest, Hungary, 2024; Volume 2, ISBN 978-963-9545-65-6. [Google Scholar]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Beardmore, B.; Riepe, C.; Pagel, T. Species-Specific Preference Heterogeneity in German Freshwater Anglers, with Implications for Management. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 32, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, F.; Morales-Nin, B. Anglers’ Perceptions of Recreational Fisheries and Fisheries Management in Mallorca. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2013, 82, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Raghavan, R.; Sivakumar, K.; Mathur, V.; Pinder, A.C. Assessing Recreational Fisheries in an Emerging Economy: Knowledge, Perceptions and Attitudes of Catch-and-Release Anglers in India. Fish. Res. 2015, 165, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, R.; Alós, J.; Beardmore, B.; Daedlow, K.; Dorow, M.; Fujitani, M.; Hühn, D.; Haider, W.; Hunt, L.M.; Johnson, B.M.; et al. Understanding and Managing Freshwater Recreational Fisheries as Complex Adaptive Social-Ecological Systems. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2017, 25, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnichsen, O.; Jensen, C.L.; Olsen, S.B. Fishing for More Tourists—An Empirical Investigation of Tourist Anglers’ Preferences for Angling Site Quality. Mar. Policy 2019, 106, 103532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenichel, E.P.; Abbott, J.K.; Huang, B. Modelling Angler Behaviour as a Part of the Management System: Synthesizing a Multi-disciplinary Literature. Fish Fish. 2013, 14, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, C.; Voyer, M.; McIlgorm, A.; Li, O. Chasing the Thrill or Just Passing the Time? Trialing a New Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Heterogeneity amongst Recreational Fishers Based on Motivations. Fish. Res. 2018, 199, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, T.R.; Dabrowska, K.; Haider, W.; Parkinson, E.A.; Varkey, D.A.; Ward, H.; McAllister, M.K.; Godin, T.; Van Poorten, B.; Askey, P.J.; et al. Landscape-Scale Social and Ecological Outcomes of Dynamic Angler and Fish Behaviours: Processes, Data, and Patterns. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 76, 970–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deely, J.; Hynes, S.; Curtis, J. Coarse Angler Site Choice Model with Perceived Site Attributes. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 32, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, S.; O’Reilly, P.; Corless, R. An On-Site versus a Household Survey Approach to Modelling the Demand for Recreational Angling: Do Welfare Estimates Differ? Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 16, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardmore, B.; Haider, W.; Hunt, L.M.; Arlinghaus, R. The Importance of Trip Context for Determining Primary Angler Motivations: Are More Specialized Anglers More Catch-Oriented than Previously Believed? N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2011, 31, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardmore, B.; Haider, W.; Hunt, L.M.; Arlinghaus, R. Evaluating the Ability of Specialization Indicators to Explain Fishing Preferences. Leis. Sci. 2013, 35, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, C.; Schroeder, S.A.; Fulton, D.C. Site Choice among Minnesota Walleye Anglers: The Influence of Resource Conditions, Regulations and Catch Orientation on Lake Preference. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2012, 32, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.; Breen, B. Irish Coarse and Game Anglers’ Preferences for Fishing Site Attributes. Fish. Res. 2017, 190, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitila, T.; Paulrud, A. A Multi-Attribute Extension of Discrete-Choice Contingent Valuation for Valuation of Angling Site Characteristics. J. Leis. Res. 2006, 38, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, S.; Beardmore, B.; Haider, W.; Dieckmann, U.; Arlinghaus, R. Ecological, Angler, and Spatial Heterogeneity Drive Social and Ecological Outcomes in an Integrated Landscape Model of Freshwater Recreational Fisheries. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2019, 27, 170–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, G.; Péter, G.; Halasi-Kovács, B. A halközösség struktúrájának sajátosságai a Tisza-tó különböző élőhelyein—(The attribution of the fish community structure in the different habitat types of the Lake Tisza). Pisces Hung. 2014, 8, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).