How Does the National Key Ecological Function Areas Policy Affect High-Quality Economic Development?—Evidence from 243 Cities in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Theoretical Mechanism and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Direct Effect

3.2. Indirect Effect

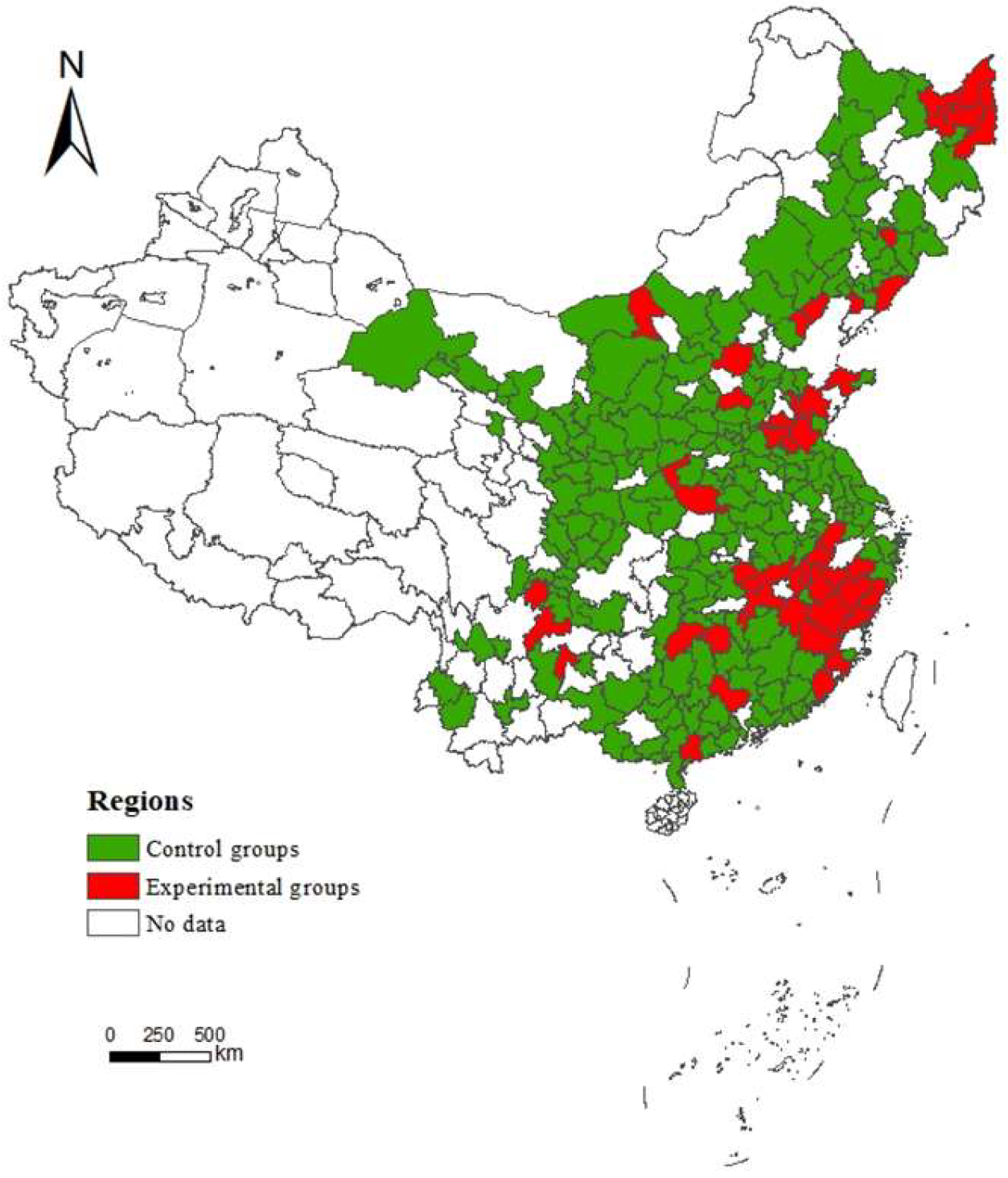

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Model Construction

4.2. Variables Selection and Measurement

4.2.1. Data Sources

4.2.2. Explained Variables

4.2.3. Core Explanatory Variables

4.2.4. Controlled Variables

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Benchmark Results

5.2. Robustness Test

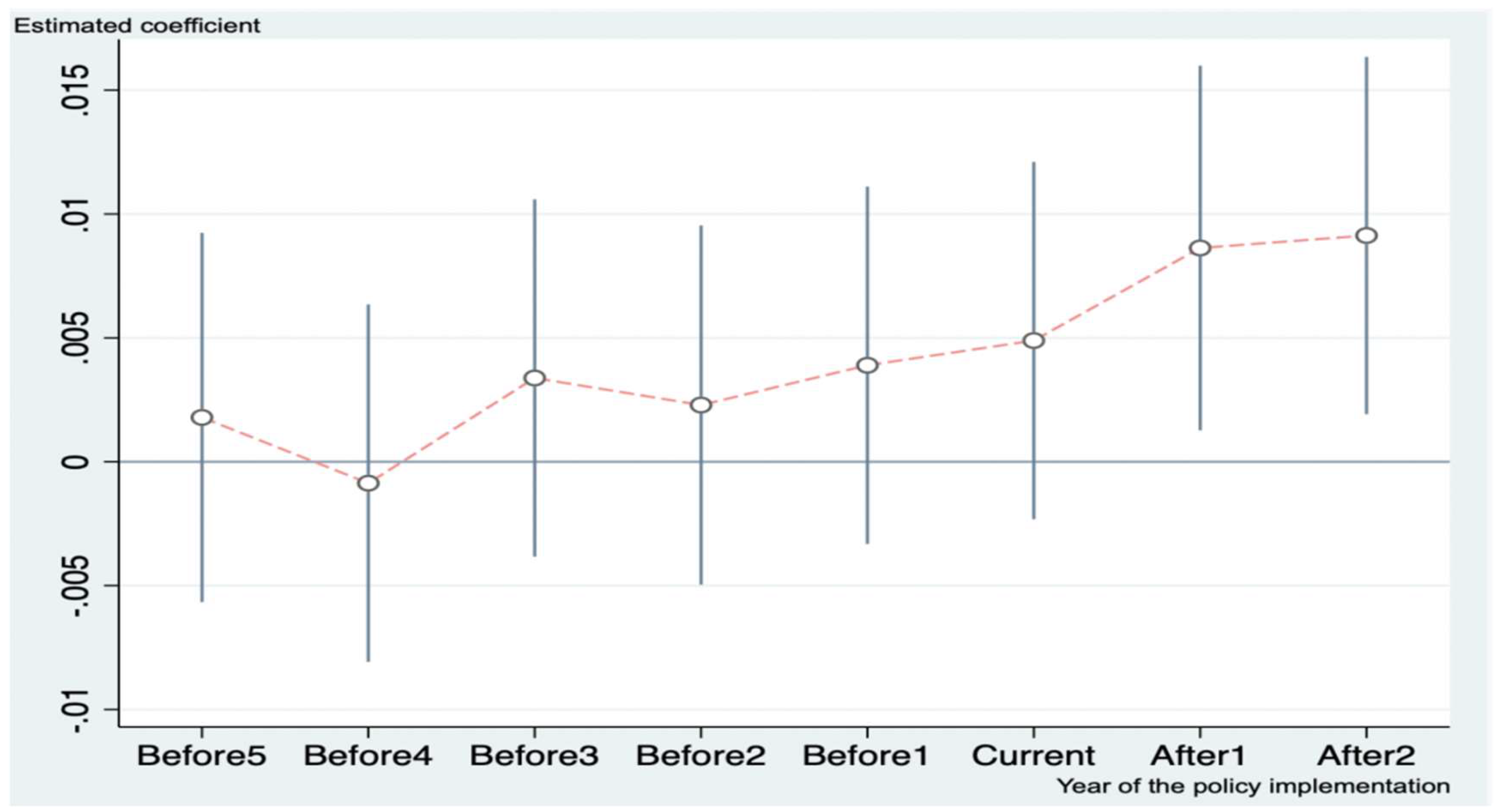

5.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

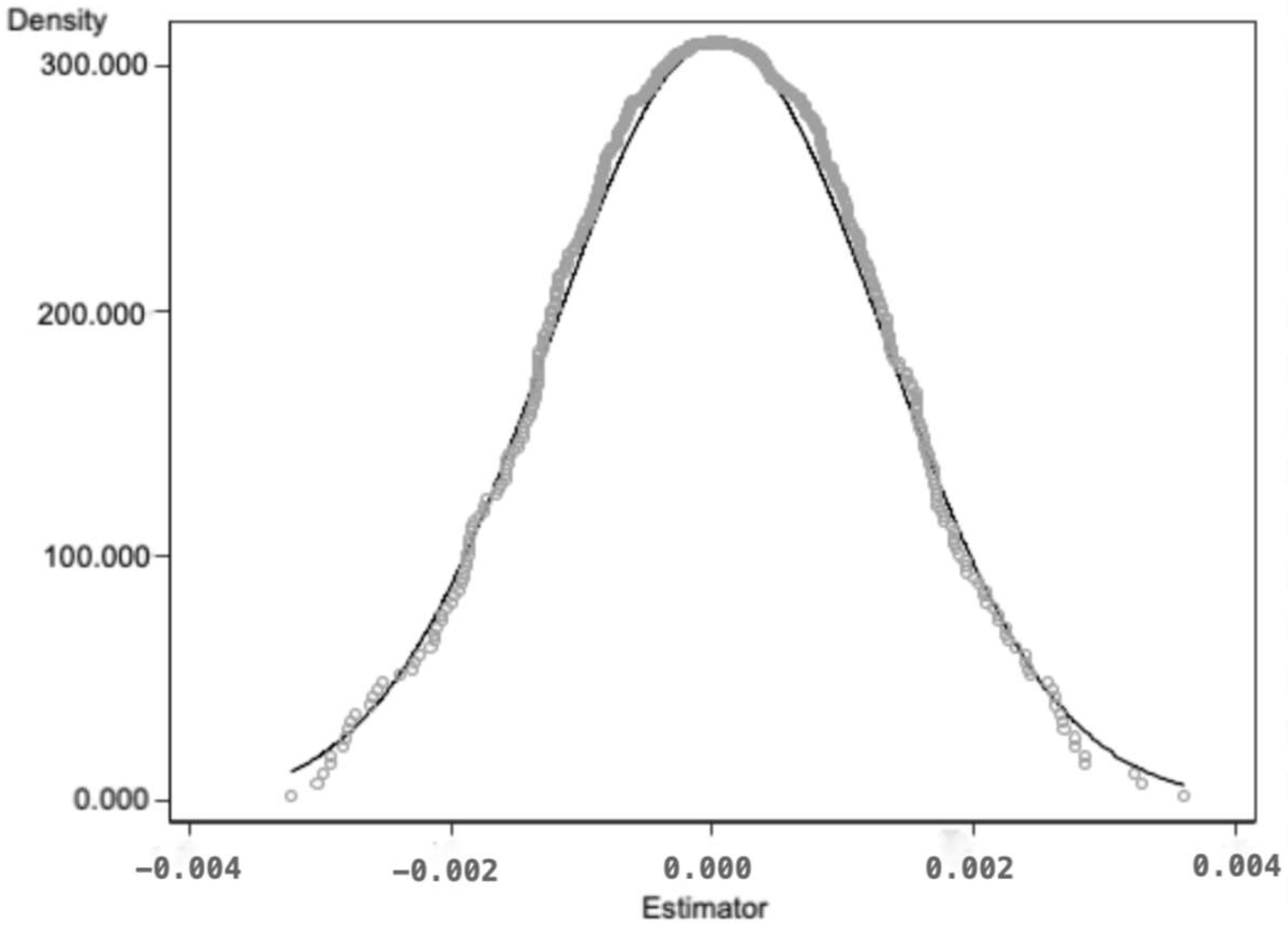

5.2.2. Placebo Test

5.2.3. Replacement of Explanatory Variables

5.2.4. Excluding Other Major Policies

5.3. Transmission Mechanism Analysis

5.3.1. Stimulating Consumer Demand

5.3.2. Increasing Investment in Technology and Education

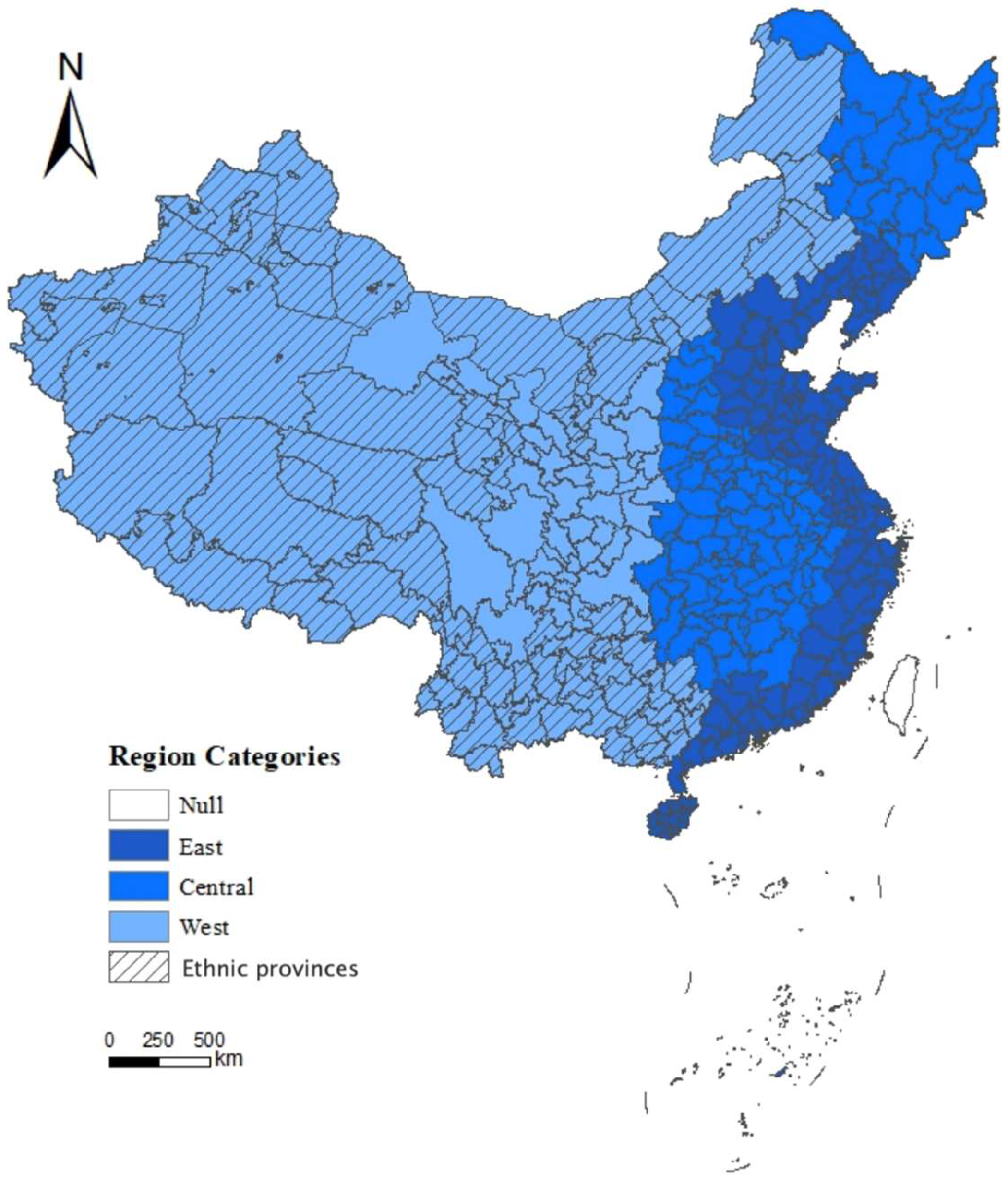

5.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.4.1. Analysis of Regional Heterogeneity in East, Central and West of China

5.4.2. Analysis of Regional Heterogeneity in Ethnic and Non-Ethnic Provinces of China

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion on Heterogeneity

6.2. Discussion on Intermediary Mechanism

6.3. Discussion on the Implications of Policy for Developing Countries

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Effectively guiding and supporting industries in key ecological function areas to further boost the consumption demand. The development of suitable industries is not only conducive to increasing people’s income, but also profoundly affects the regional consumption demand. NEKFA, under the premise of following the priority of protection, should be based on regional advantages and natural endowments to create one or even multiple growth poles to drive consumption. For example, the western region can establish the new concept of “regional tourism” by virtue of its good natural environment and diverse folk customs, actively develop the ecotourism industry, provide high-quality ecological products and enhance the vitality of economic development.

- (2)

- In the process of building the NKEFA, support for investment in technology and education should be increased. For example, Anji County in the Zhejiang Province, as a pilot zone, has paid attention to improving the level of education and technology in the process of policy implementation and promoted the upgrading and transformation of local industries by introducing high-end talents and advanced technologies. According to practical experience and experimental results, the investment in technology and education plays a positive role. This can lead to innovation while also improving energy use efficiency, improving the quality and skills of workers and achieving environmental and economic benefits. In the long run, it can maximize the encouragement of the zone to stimulate the endogenous development power of the western region and ethnic regions and alleviate the problem of unbalanced development between regions.

- (3)

- Policy makers should formulate differentiated policies according to the actual development of different regions and ensure the fairness and effectiveness of policies as much as possible. Since the effect of the policy is significant in the eastern and central regions, it is suggested to further strengthen the construction of the policy in these regions, optimize the allocation of resources, encourage the research and development of green technology and improve the coordinated development of ecological quality and economic quality in these regions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arrow, K.; Bolin, B.; Costanza, R.; Dasgupta, P.; Folke, C.; Holling, C.S.; Jansson, B.O.; Levin, S.; Mäler, K.G.; Perrings, C.; et al. Economic Growth, Carrying Capacity, and the Environment. Science 1995, 268, 520–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbaz, M.; Ozturk, I.; Afza, T.; Ali, A. Revisiting the environmental Kuznets curve in a global economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Dai, W.; Burns, K. Evaluation of industrial green development and industrial green competitiveness: Evidence from Chinese urban agglomerations. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 124, 107371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomislav, K. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Chen, D. Air pollution, Government control and high-quality economic development. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2018, 53, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, E.; Caprioli, C.; Cotella, G. Unpacking SDG target 11a: What is it about and how to measure its progress? City Environ. Interact. 2022, 14, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Hao, X. Does neighboring green development benefit or suffer from local economic growth targets? Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2023, 120, 106149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Su, X.; Yao, S. Nexus between green finance, fintech, and high-quality economic development: Empirical evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Lv, X.; Ma, L.; Shen, X. Can industrial relocation reduce air pollution? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 910668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Sharifi, A.; He, B. Resilient Smart Cities: Theoretical and Empirical Insights; The Urban Book Series; Sharifi, A., Salehi, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Jiang, Q.; Dong, X.; Dong, K.; Jiang, H. How does industrial structure adjustment reduce CO2 emissions? Spatial and mediation effects analysis for China. Energy Econ. 2022, 105, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasztelan, A. Green growth, green economy and sustainable development: Terminological and relational discourse. Prague Econ. Pap. 2017, 26, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lai, X.; Lu, C.; Cao, S. What has caused China’s economic growth? Econ. Syst. 2022, 46, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Xiong, L.; Wang, F. Is there an environment and economy trade off for the National Key Ecological Function Area policy in China? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 104, 107347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Sun, W.; Zhou, K.; Chen, D. Major function oriented zone: New method of spatial regulation for reshaping regional development pattern in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2012, 22, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Jiang, A.; Bao, B. Can China’s transfer payment in key ecological function areas reduce the carbon intensity?–Quasi–Natural experimental evidence from Jiangxi, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-b.; Zhong, C.-b. The establishment of the national key ecological functional zone and the county’s ecological green development. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1144245. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H.; Xue, B. Farmer households’ livelihood resilience in ecological-function areas: Case of the Yellow River water source area of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 9665–9686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yu, Z.; Ma, Z.; Xu, D.; Cao, S. What factors have driven urbanization in China? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 6508–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Lian, H.; Qin, Q. Spatial disparities of the coupling coordinated development among the economy, environment and society across China’s regions. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; He, Y.; Yu, C.; Chen, M. The development status and protection of traditional qiang ethnic minority villages. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1944, 020018. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, S.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, Y. Tourism and sociocultural identity discourses in ethnic minority communities: A study of she ethnic townships in Zhejiang Province, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J. Research on the Revitalization Path of Ethnic Villages Based on the Inheritance of Spatial Cultural Genes—Taking Tujia Village of Feng Xiang Xi in Guizhou Province as a Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.H.; Jiang, D.F.; Luan, Y.F.; Yao, Y. GIS-based spatial differentiation of ethnic minority villages in Guizhou Province, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2022, 19, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hou, P.; Jiang, J.; Zhai, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhang, B.; Xu, H. Coordination study on ecological and economic coupling of the Yellow River Basin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Feng, H.; Cao, Y. The spatial spillover effect of innovative city policy on carbon efficiency: Evidence from China. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Chen, L.; Feng, Q. Impacts of the Natural Forest Conservation Program on the livelihoods of residents of Northwestern China: Perceptions of residents affected by the program. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1454–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.; Zheng, C. Managing the poverty–CO2 reductions paradox: The case of China and the EU. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhou, X.; Wan, J. Unlocking sustainability potential: The impact of green finance reform on corporate ESG performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 4211–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Riechers, M.; Loos, J.; Martin-Lopez, B.; Temperton, V.M. Making the UN decade on eco-system restoration a social-ecological endeavour. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, M.; Zens, G.; Bangalor, M. Does the environment matter for poverty reduction. In The Role of Soil Fertility and Vegetation Vigor in Poverty Reduction; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Xue, W. Impacts of nature reserves on local residents’income in China. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 199, 107494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, L. The effects of population aging, life expectancy, unemployment rate, population density, per capita GDP, urbanization on per capita carbon emissions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 760–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kong, J. Effect of Equity in Education on the Quality of Economic Growth: Evidence from China. J. Hum. Sci. 2010, 7, 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, L.; Chen, Z. The Convergence Analysis of Regional Growth Differences in China: The Perspective of the Quality of Economic Growth. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2016, 9, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Lee, C.C. How does green finance affect green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2022, 107, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, D. Haze pollution, government governance and high-quality economic development. Econ. Res. 2018, 53, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Chen, H.; Hao, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, X.; Mok, T.M. The dynamic relationship between environmental pollution, economic development and public health: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.; Dailami, M.; Mansoor, D. The Quality of Growth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Wang, H. Comprehensive evaluation of urban high-quality development: A case study of Liaoning Province. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Wang, J.; Lu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. High-quality development in China: Measurement system, spatial pattern, and improvement paths. Habitat Int. 2021, 118, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, C.; Cheng, L. Measurement and Comparison of the High Quality Development Level of the World Economy. Economist 2020, 5, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.; Jiang, D.; Fu, J.; Cao, C.; Zhang, D. Spatial Conflict of Production–Living–Ecological Space and Sustainable-Development Scenario Simulation in Yangtze River Delta Agglomerations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Kern, F. Creative destruction or mere niche support? Innovation policy mixes for sustainability transitions. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.M.; Gomez, I.A.; Love, H.A. Environmental regulation cost and industry structure changes. Land Econ. 2011, 87, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z.; Qin, C.; Ye, X. Environmental regulation, economic network and sustainable growth of urban agglomerations in China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Qin, X. Financing constraints, carbon emissions and high-quality urban development—Empirical evidence from 290 Cities in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Guide for Delimiting Ecological Protection Red Lines. 2015. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bwj/201505/t20150518_301834.htm (accessed on 8 May 2015).

- BJNEWS. What Are the Advantages of China’s Ecological Protection Red Line Experience Being Recommended? Detailed Explanation by Experts from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment. 2021. Available online: https://www.bjnews.com.cn/detail/163118288214699.html (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Song, Z.; Wang, C.; Bergmann, L. China’s prefectural digital divide: Spatial analysis and multivariate determinants of ICT difusion. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christainsen, G.; Haveman, R. The contribution of environmental regulations to the slowdown in productivity growth. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1981, 8, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, P. Economic effects analysis of environmental regulation policy in the process of industrial structure upgrading: Evidence from Chinese provincial panel data. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 142004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. New digital infrastructure, financial resource allocation and high quality economic development in the internet Era. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2023, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okerekeoti, C.U. Government expenditure on education and economic growth in Nigeria. Int. J. Recent Res. Commer. Econ. Manag. (IJRRCEM) 2022, 9, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.C.; Lai, S.L. Government spending on tertiary education, knowledge, technology, and economic growth. J. Econ. Dev. 2022, 47, 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, Z. Government expenditure structure, technological progress and economic growth. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2024, 19, 3729–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wang, J.; Hua, X.; Liu, Z. Entrepreneurship and high-quality economic development: Based on the triple bottom line of sustainable development. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubas, G.; Ravikumar, B.; Ventura, G. Talent, labor quality, and economic development. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2016, 21, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hu, H. Carbon emissions, consumption structure upgrading, and high-quality economic development: Empirical evidence from China. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2021, 29, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. Social capital, innovation and economic growth. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2018, 73, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liu, J. Community-based ecotourism in nature reserve of China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2004, 14, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzula, N.I.; Armono, H.D.; Rosyid, D.M. Management of Baluran National Park resources for coastal ecotourism based on suitability and carrying capacity. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2017, 862, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.; Regmi, K.D.; Khanal, P.R. Host learning in community-based ecotourism in Nepal: The case of Sirubari and Ghalegaun homestays. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Yuan, Y. Industrial collaborative clustering, technological innovation and the quality of economic growth-based on empirical analysis of producer service industry and high-tech manufacturing industry. Theory Pract. Financ. Econ. 2020, 41, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Sun, Z. How does manufacturing agglomeration affect high-quality economic development in China? Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, R.B.; Bertarelli, S. Nonlinearities in economic growth and club convergence. Empir. Econ. 2013, 44, 1171–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Jian, X.H. Measurement of china’s high-quality development and analysis of provincial status. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2020, 37, 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, R.; Li, T.D. Establishment of free trade areas and high-quality economic development-quasi-natural experiment based on FTA. J. Bus. Econ. 2020, 5, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Yao, Y.; Long, X. What causes PM2. 5 pollution? Cross-economy empirical analysis from socioeconomic perspective. Energy Policy 2018, 119, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, R.; Joachim, W. Intra-industry adjustment to import competition: Theory and application to the German clothing industry. World Econ. 2010, 33, 1006–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Z.; Li, Z. Do foreign institutional investors enhance firm innovation in China? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2019, 26, 1125–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C. The role of parallel trends in event study settings: An application to environmental economics. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2021, 8, 235–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Chen, G. Can the carbon emissions trading system improve the green total factor productivity of the pilot cities?—A spatial difference-in-differences econometric analysis in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, W.; Cai, Z.; Luo, H. The environmental efects of digital economy: Evidence from province-level empirical data in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 63272–63288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First-Level Indicators | Second-Level Indicators | Detailed Indicators | Information Entropy (e) | Information Utility Value (d) | Weighting Factor (w) | Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality economic development | Innovative development | Financial Inclusion Index | 0.9885 | 0.0115 | 5.13% | + |

| Coordinated development | Industrial Advancement | 0.9828 | 0.0172 | 7.66% | + | |

| Public fiscal expenditure as a share of GDP | 0.9844 | 0.0156 | 6.98% | + | ||

| Population urbanization rate | 0.9896 | 0.0104 | 4.65% | + | ||

| Unemployment rate | 0.9995 | 0.0005 | 0.20% | − | ||

| Green Development | Comprehensive utilization rate of general industrial solid waste | 0.9936 | 0.0064 | 2.87% | + | |

| Centralized treatment rate of sewage treatment plants | 0.9968 | 0.0032 | 1.42% | + | ||

| Greening coverage in built-up areas | 0.998 | 0.002 | 0.88% | + | ||

| Open Development | Tens of thousands of Internet broadband access subscribers | 0.9643 | 0.0357 | 15.96% | + | |

| Shared Development | Number of doctors (medical practitioners, medical assistants) | 0.9732 | 0.0268 | 11.96% | + | |

| Road mileage | 0.9819 | 0.0181 | 8.08% | + | ||

| Number of students enrolled in general secondary schools | 0.9744 | 0.0256 | 11.44% | + | ||

| Number of pupils enrolled in primary schools | 0.9677 | 0.0323 | 14.44% | + | ||

| Urban–rural income gap | 0.9963 | 0.0037 | 1.67% | − | ||

| Real disposable income of the population | 0.9851 | 0.0149 | 6.66% | + |

| Types | Variables | N | Min | Max | Mean | Sd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variables | Composite index of high-quality development | 2187 | 0.10 | 0.66 | 0.27 | 0.79 |

| Core explanatory variables | did | 2187 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.28 |

| Controlled variables | Industrial value added per capita | 2187 | 1024.62 | 678,727,079.70 | 812,731.91 | 18,098,215.03 |

| Investment in fixed assets as a share of GDP | 2187 | 1218.32 | 417,527.70 | 36,980.71 | 25,045.53 | |

| PM2.5 | 2187 | 1844.42 | 27,439.17 | 10,450.32 | 4698.23 | |

| Loans from financial institutions per capita | 2187 | 693,465.42 | 301,167,299.00 | 15,437,010.12 | 21,669,475.35 | |

| Imports and exports per capita | 2187 | 0.10 | 209,697.62 | 8975.31 | 20,610.21 | |

| Mediating variables | Per capita retail sales of consumer goods | 2187 | 494.70 | 72,777.99 | 16,727.26 | 9539.73 |

| Per capita expenditure on science and technology education | 2187 | 1.04 | 141.74 | 18.28 | 4.88 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| did | 0.0583 *** (16.30) | 0.0038 * (2.28) | 0.0158 *** (7.39) | 0.0043 ** (2.63) |

| cons | 0.2595 *** (323.82) | 0.2175 *** (224.10) | 0.2628 *** (576.56) | 0.2253 *** (191.11) |

| R2 | 0.0103 | 0.8211 | 0.6843 | 0.8334 |

| F | 265.5313 | 1.1 × 103 | 821.8468 | 790.2142 |

| Control | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| City-FE | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Year-FE | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Obs | 2187 | 2187 | 2187 | 2187 |

| Variables | Replacement of Explanatory Variables | Elimination of Other Policy (Ecological Civilization Pilot Zone) | Elimination of Other Policy (Green Shield Action) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| did | 0.0043 ** (2.68) | 0.0048 * (2.54) | 0.0931 *** (4.18) |

| cons | 0.2308 *** (196.77) | 0.2254 *** (176.78) | −0.5076 *** (−36.63) |

| R2 | 0.8608 | 0.8275 | 0.8604 |

| F | 972.6124 | 697.5903 | 778.6174 |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City-FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 2187 | 2007 | 1737 |

| Variables | Per Capita Retail Sales of Consumer Goods | High-Quality Economic Development | Per Capita Expenditure on Technology and Education | High-Quality Economic Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| did | 0.0772 * (2.51) | 0.1269 ** (3.23) | ||

| M | 0.0083 *** (6.80) | 0.0086 *** (9.15) | ||

| Did × M | 0.0063 *** (3.81) | 0.0058 *** (3.56) | ||

| R2 | 0.7220 | 0.7268 | ||

| F | 521.2784 | 894.5424 | ||

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City-FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 2187 | 2187 | 2187 | 2187 |

| Variables | Eastern Region | Central Region | Western Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| did | 0.0056 * (2.16) | 0.0047 * (2.18) | 0.0020 (0.44) |

| cons | 0.6138 *** (6.80) | 0.6090 *** (10.13) | 0.1910 *** (96.16) |

| R2 | 0.8504 | 0.8531 | 0.8451 |

| F | 386.3946 | 357.3948 | 243.3903 |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City-FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 864 | 864 | 459 |

| Variables | Ethnic Provinces | Non-Ethnic Provinces |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| did | 0.0015 (0.31) | 0.0837 *** (32.96) |

| cons | −0.1241 (−0.81) | 0.2317 *** (161.98) |

| R2 | 0.8571 | 0.8306 |

| F | 114.3830 | 665.6672 |

| Control | Yes | Yes |

| City-FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year-FE | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 261 | 1926 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Su, C.; Xu, C. How Does the National Key Ecological Function Areas Policy Affect High-Quality Economic Development?—Evidence from 243 Cities in China. Land 2025, 14, 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020345

Zhang Y, Su C, Xu C. How Does the National Key Ecological Function Areas Policy Affect High-Quality Economic Development?—Evidence from 243 Cities in China. Land. 2025; 14(2):345. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020345

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuqian, Chenchen Su, and Chen Xu. 2025. "How Does the National Key Ecological Function Areas Policy Affect High-Quality Economic Development?—Evidence from 243 Cities in China" Land 14, no. 2: 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020345

APA StyleZhang, Y., Su, C., & Xu, C. (2025). How Does the National Key Ecological Function Areas Policy Affect High-Quality Economic Development?—Evidence from 243 Cities in China. Land, 14(2), 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14020345