Research on Urban Spatial Environment Optimization Based on the Combined Influence of Steady-State and Dynamic Vitality: A Case Study of Wuhan City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

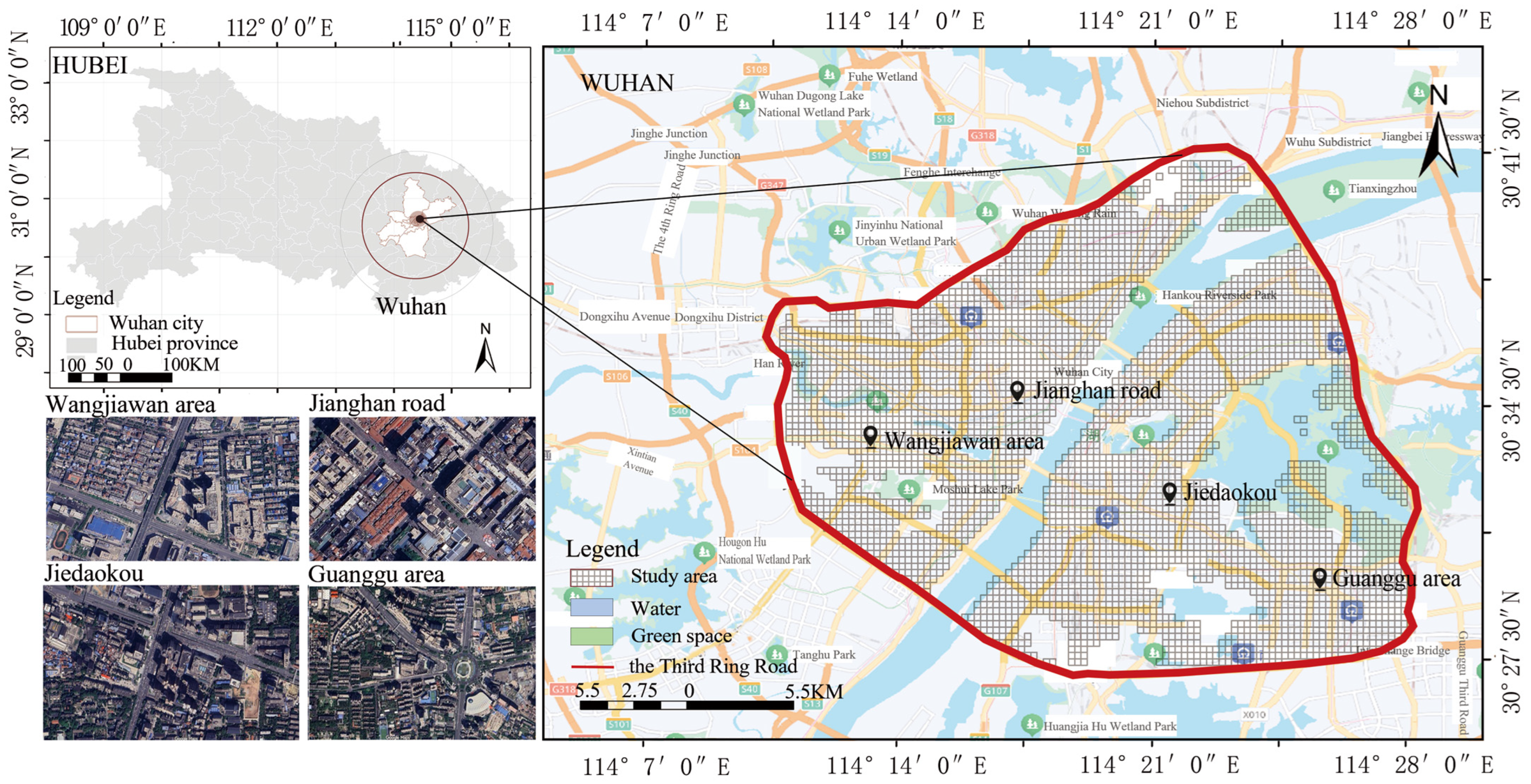

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Mobile Phone Signaling Data

2.2.2. Tencent Location Big Data

2.2.3. Influencing Indicator Data

2.3. Methodology of Steady-State Vitality Research

2.3.1. Steady-State Vitality

2.3.2. The Spatial Aggregation of SVI

2.3.3. Quantitative Study on the Influencing Indicator of SVI

2.4. Methodology for Dynamic Vitality Research

2.4.1. Dynamic Vitality Spatial Density

2.4.2. Vitality Fluctuation Index

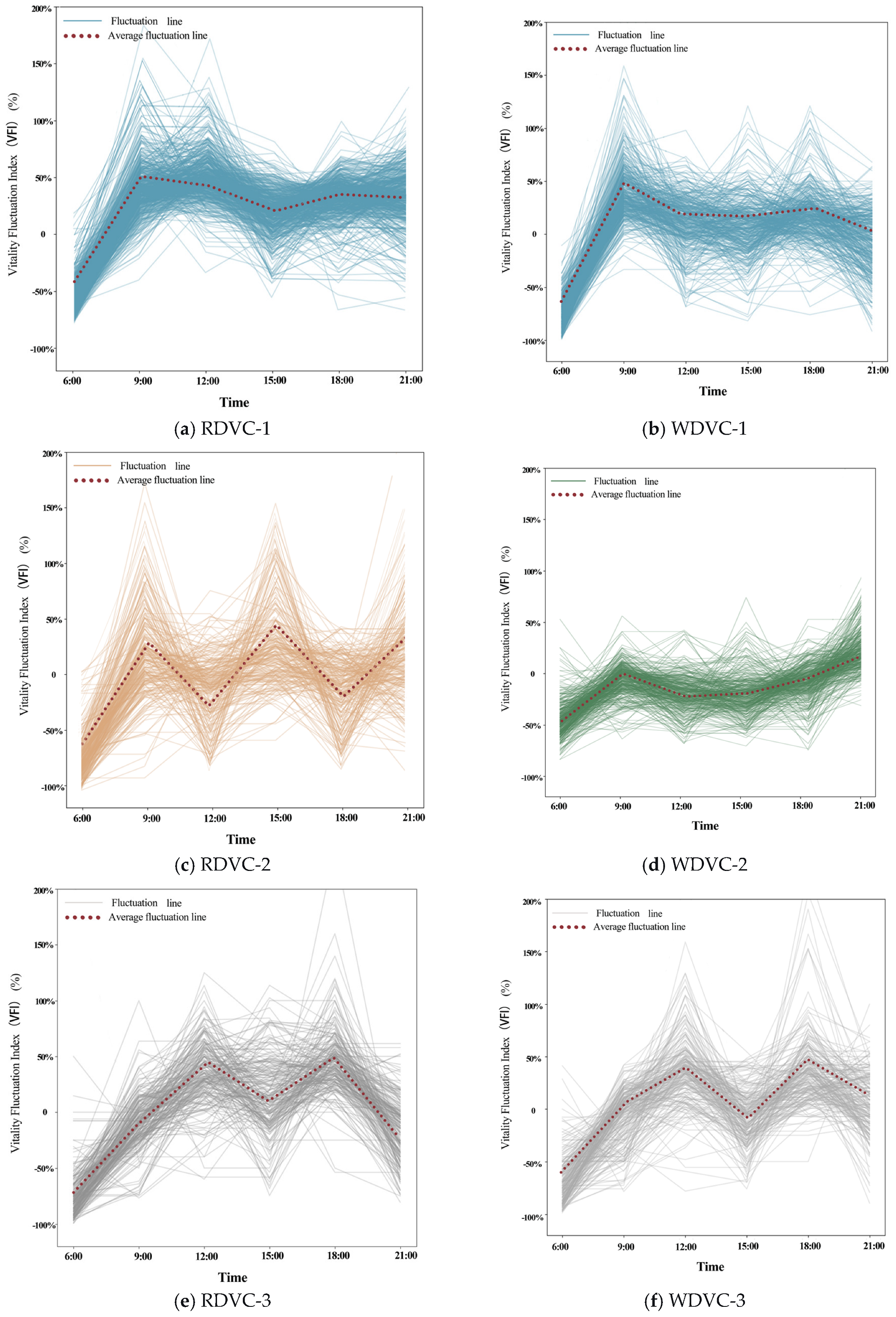

2.4.3. VFI Clustering Analysis

2.4.4. Quantitative Study on the Influencing Indicator of VFI Clustering Results

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Urban Steady-State Vitality

3.1.1. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of SVI

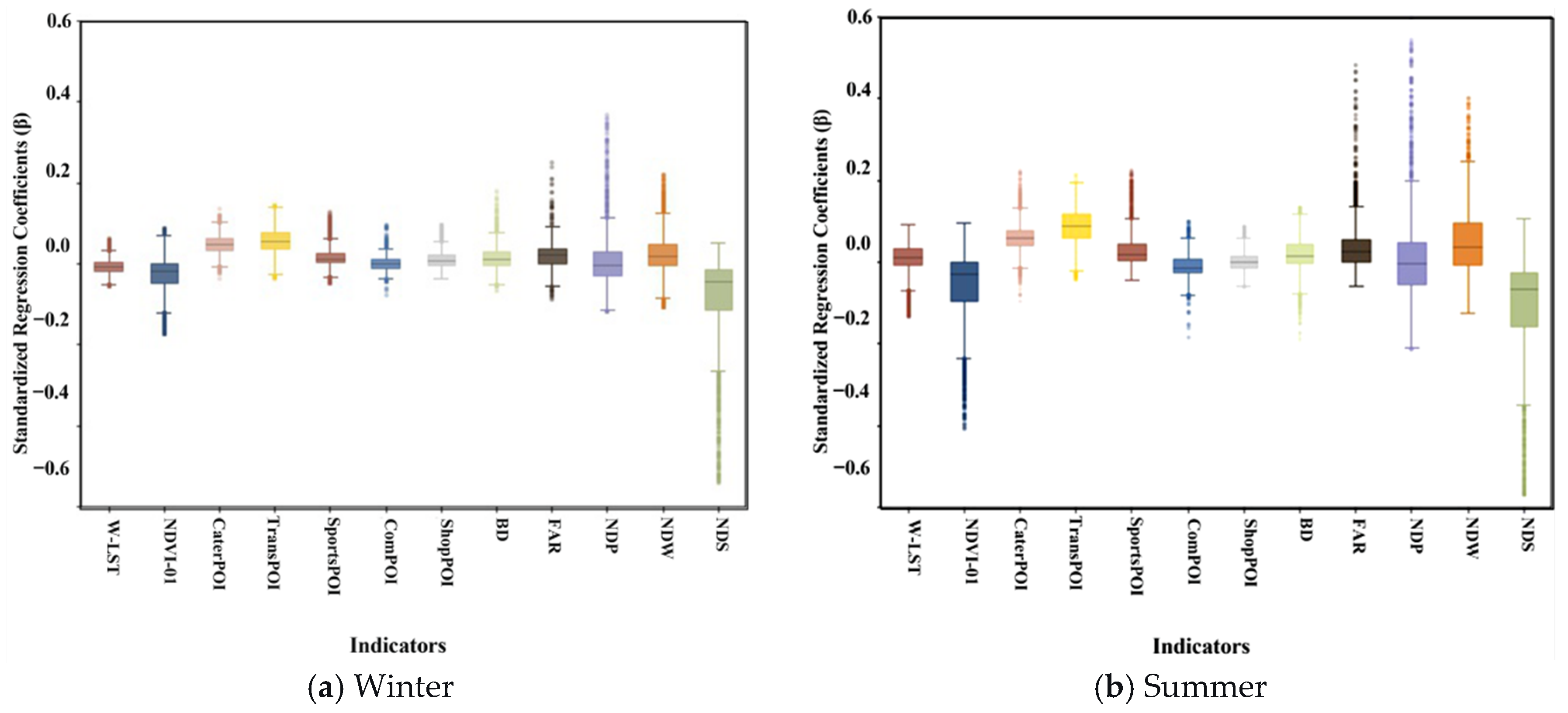

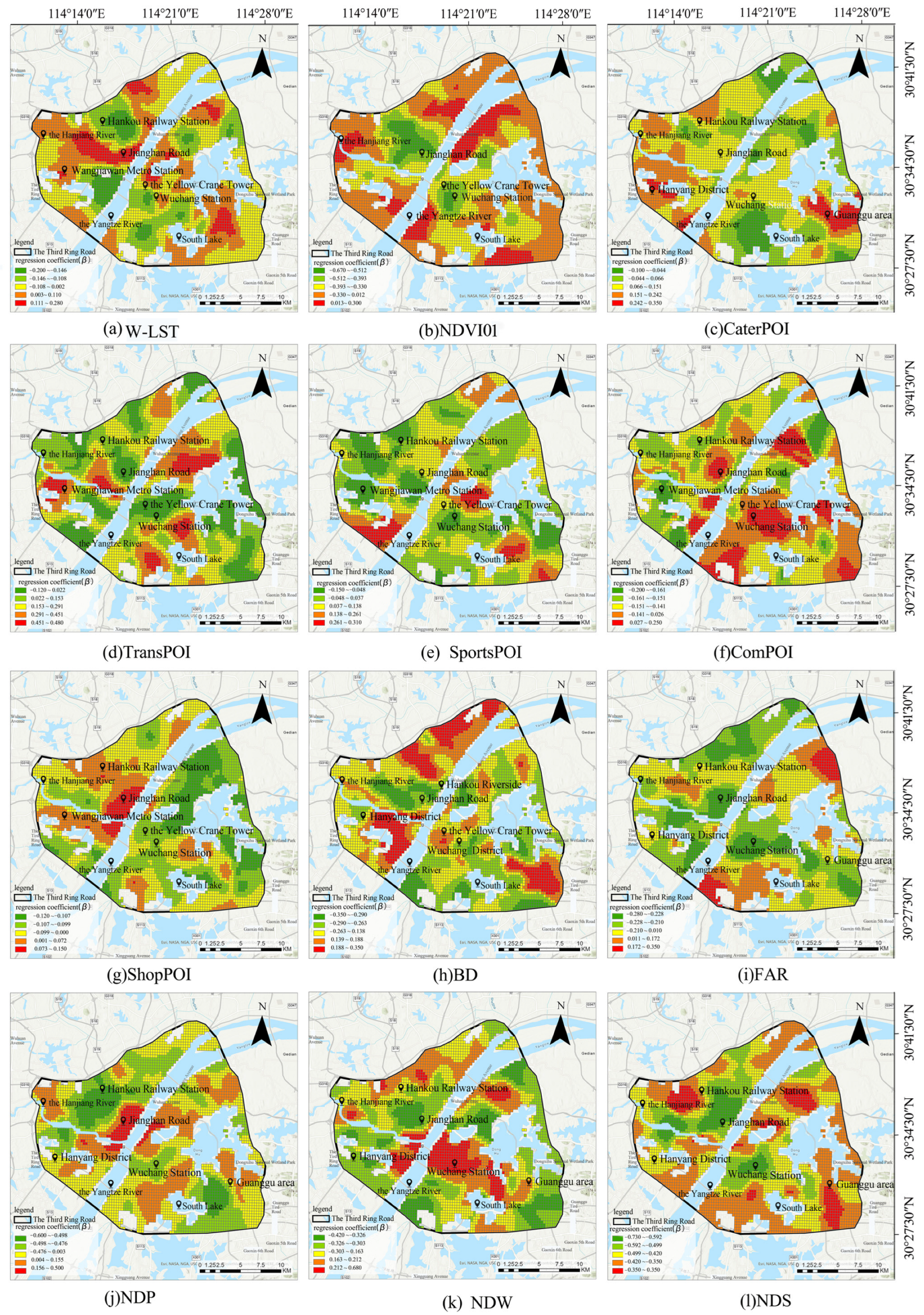

3.1.2. Analysis of Influencing Indicator

3.2. Analysis of Urban Dynamic Vitality

3.2.1. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of DVSD

3.2.2. Analysis of VFI Cluster Result

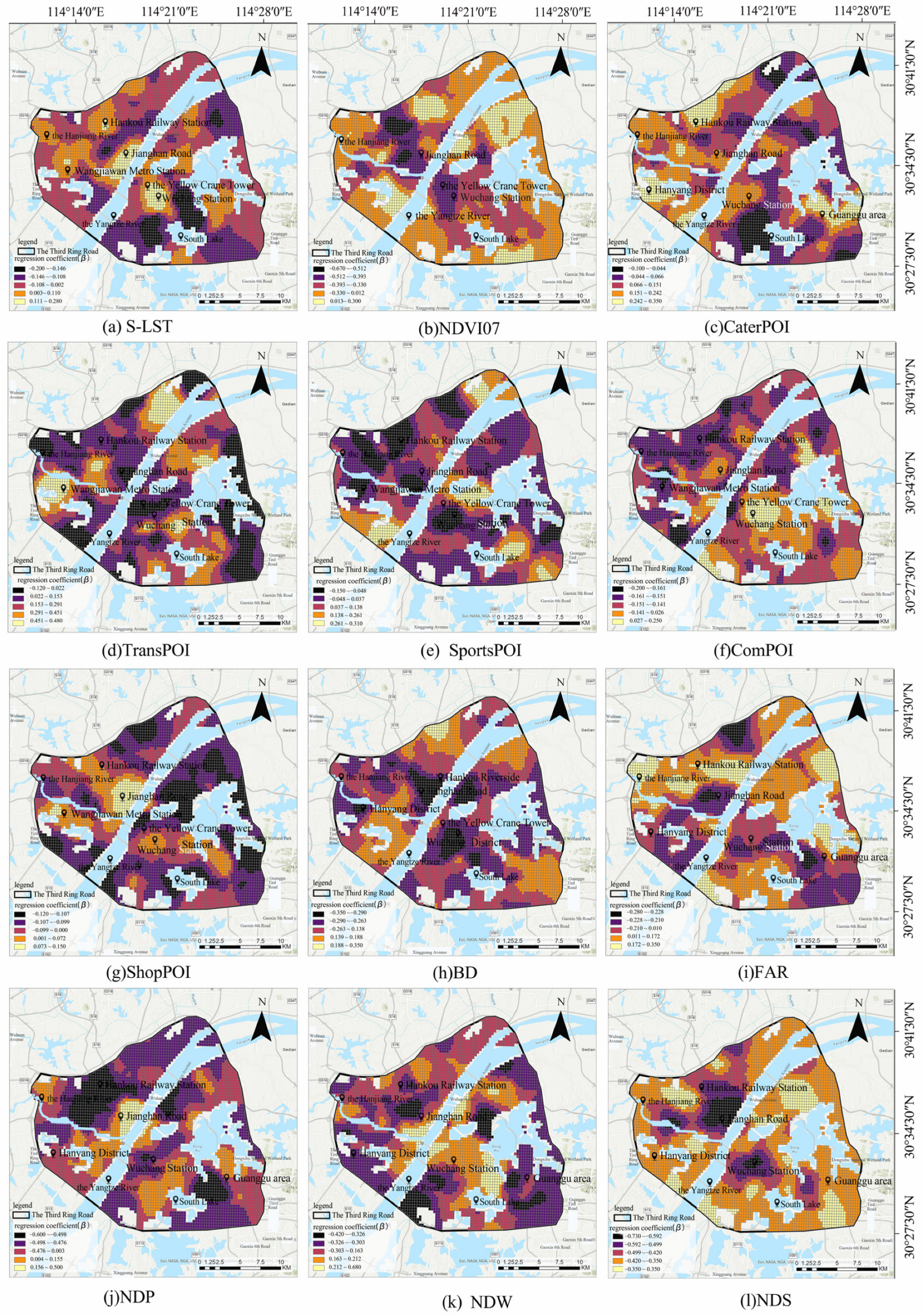

3.2.3. Analysis of Influencing Indicators for Urban DVC Formation

Analysis of Influencing Factors for RDVC-1 and WDVC-1

Analysis of Influencing Factors of RDVC-2

Analysis of Influencing Factors of WDVC-2

Analysis of Influencing Factors of RDVC-3 and WDVC-3

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.1.1. Mechanisms of Polycentric Steady-State Vitality

4.1.2. Mechanisms of Dynamic Vitality DVC

4.1.3. The Interactive Relationship Between Steady-State and Dynamic Vitality

4.2. Implication and Limitation

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- From the perspective of steady-state vitality, the central districts of Wuhan within the Third Ring Expressway demonstrate a polycentric structure, with commercial districts, universities, and transportation hubs forming the core zones of high vitality. Specifically, over 63% of the areas classified as level-5 high-vitality cores (SVI = 5) are occupied by university campuses and commercial centers, where factors such as TransPOI (β > 0.18) and CaterPOI (β > 0.11) exert significant positive effects on the formation of high vitality. Moreover, the area of level-5 SVI high-vitality zones in summer is approximately 5.97 times larger than in winter, indicating a pronounced seasonal variation in the effects of natural elements on steady-state vitality. This also verifies that large Chinese cities exhibit a polycentric vitality structure with mixed functions, providing specific practical directions for the optimal spatial functional layout of Wuhan’s urban space.

- (b)

- The spatiotemporal distribution of dynamic vitality exhibits distinct patterns between weekdays and rest day. Compared with rest days, weekday population aggregation peaks occur approximately three hours earlier—around 9:00—mainly driven by commuting demand. In contrast, on rest days, the peak area of level-5 DVSD zones appears around 12:00 and is primarily influenced by nearby leisure facilities and green spaces. Moreover, due to residents’ recreational activities on rest days, the area of level-5 DVSD zones at 21:00 is 21% larger than that on weekdays. This study reveals distinct urban vitality patterns between weekdays and rest days. Accordingly, urban management should adopt time-differentiated strategies: prioritizing commuting efficiency on weekdays and focusing on the development of leisure and nighttime economies on rest days, so as to achieve the optimal allocation of spatial resources.

- (c)

- The spatial aggregation and dispersion characteristics of dynamic vitality are influenced by multiple factors. FAR (β > 0.083) serves as a key determinant of the RDVC-1 and WDVC-1 patterns, which represent areas of sustained high-density population aggregation and maintain average VFI values above 25% throughout the day. The RDVC-2 typically occurs in areas distant from metro stations (NDS: = 0.178), with low vegetation coverage (NDVI01: = −0.470) and a sparse distribution of commercial facilities (ComPOI: = −0.329), exhibiting pronounced periodic fluctuations. In contrast, green coverage (NDVI01: = 0.294) and building density (BD: = 0.263) exert strong positive effects on the formation of the WDVC-2 pattern, characterized by low—low aggregation of citizens’ activities. This pattern is primarily distributed in residential and educational—research land, accounting for approximately 55.8% of such areas. Both RDVC-3 and WDVC-3 patterns display bimodal fluctuations in VFI values, with variations primarily driven by CaterPOI (β > 0.18) and NDVI01 (β > 0.13). By systematically deconstructing the multi-pattern differentiation mechanism of urban dynamic vitality, this study proposes a pattern-oriented urban governance approach, whose core lies in the implementation of precise and differentiated planning and management based on distinct spatial agglomeration and dispersion characteristics.

- (d)

- The areas characterized by high levels of both steady-state and dynamic vitality exhibit a substantial degree of spatial overlap, primarily concentrated around commercial districts and transportation hubs. In terms of steady-state vitality, over 90% of level-5 SVI high-vitality zones coincide with regions of equivalent vitality under dynamic conditions. Furthermore, these zones overlap by approximately 68% with zones of continuous high population aggregation, where the average VFI exceeds 30% (corresponding to RDVC-1 and WDVC-1 patterns).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GWR | Geographically Weighted Regression |

| GWLR | Geographically Weighted Logistic Regression |

| GLR | Global Logistic Regression |

| POI | Points of interest |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| W-LST | Winter Land Surface Temperature |

| S-LST | Summer Land Surface Temperature |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| CaterPOI | Catering points of interest |

| TransPOI | Transportation points of interest |

| ComPOI | Company points of interest |

| ShopPOI | Shopping points of interest |

| BD | Building Density |

| FAR | Floor Area Ratio |

| NDP | Distance to Park |

| NDW | Distance to Waterbody |

| NDS | Distance to Subway |

| SVI | Steady-state Vitality Index |

| DVSD | Dynamic Vitality Spatial Density |

| VFI | Vitality Fluctuation Index |

| DVC | Dynamic Vitality Cluster |

| WDVC | Weekday Dynamic Vitality Cluster |

| RDVC | Rest-day Dynamic Vitality Cluster |

References

- Jiang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X. Evaluating the Impact of Urban Morphology on Urban Vitality: An Exploratory Study Using Big Geo-Data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2327571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Long, Y. Urban Vitality Area Identification and Pattern Analysis from the Perspective of Time and Space Fusion. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sun, P. Urban Shrinkage and Urban Vitality Correlation Research in the Three Northeastern Provinces of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, T.; Fukuda, H.; Ma, M.H. Evidence of Multi-Source Data Fusion on the Relationship between the Specific Urban Built Environment and Urban Vitality in Shenzhen. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Cui, C.; Liu, F.; Wu, Q.; Run, Y.; Han, Z. Multidimensional Urban Vitality on Streets: Spatial Patterns and Influence Factor Identification Using Multi-Source Urban Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y. Spatial Explicit Assessment of Urban Vitality Using Multi-Source Data: A Case of Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.-D. Measuring Urban Form and Its Effects on Urban Vitality in Seoul, South Korea: Urban Morphometric Approach. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 05024019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paköz, M.Z.; Işık, M. Rethinking urban density, vitality and healthy environment in the post-pandemic city: The case of istanbul. Cities 2022, 124, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Niu, X. Influence of Built Environment on Urban Vitality: Case Study of Shanghai Using Mobile Phone Location Data. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2019, 145, 04019035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-L. Data-Driven Approach to Characterize Urban Vitality: How Spatiotemporal Context Dynamically Defines Seoul’s Nighttime. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 1235–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-L. Seoul’s wi-fi hotspots: Wi-fi access points as an indicator of urban vitality. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 72, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delclòs-Alió, X.; Gutiérrez, A.; Miralles-Guasch, C. The Urban Vitality Conditions of Jane Jacobs in Barcelona: Residential and Smartphone-Based Tracking Measurements of the Built Environment in a Mediterranean Metropolis. Cities 2019, 86, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wen, Z.; Tian, D.; Zhang, M.; Hou, Y. Study on Community Detection Method for Morning and Evening Peak Shared Bicycle Trips in Urban Areas: A Case Study of Six Districts in Beijing. Buildings 2023, 13, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Cities and Complexity: Understanding Cities with Cellular Automata, Agent-Based Models, and Fractals; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, T.D.; Avitabile, D.; Siebers, P.-O.; Robinson, D.; Owen, M.R. Modelling the emergence of cities and urban patterning using coupled integro-differential equations. J. R. Soc. Interface 2022, 19, 20220176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; He, X.; Zhou, C.; Cao, Y.; He, X.; Zhou, C. Characteristics and influencing factors of population migration under different population agglomeration patterns—A case study of urban agglomeration in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Song, X.; Niu, X. Characters of functional linkage of urban spatial structure: A case study of shanghai central city. City Plan. Rev. 2019, 43, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Varo, I.; Delclòs-Alió, X.; Miralles-Guasch, C. Jane Jacobs Reloaded: A Contemporary Operationalization of Urban Vitality in a District in Barcelona. Cities 2022, 123, 103565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, Q.C.; Ma, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X. Nonlinear and Threshold Effects of the Built Environment, Road Vehicles and Air Pollution on Urban Vitality. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 253, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, H.; Eon, C.; Breadsell, J. Improving City Vitality through Urban Heat Reduction with Green Infrastructure and Design Solutions: A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings 2020, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumelzu, A.; Barrientos-Trinanes, M. Analysis of the effects of urban form on neighborhood vitality: Five cases in Valdivia, Southern Chile. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 34, 897–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X. Impact of Check-In Data on Urban Vitality in the Macao Peninsula. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 7179965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Du, J.; Chen, M.; Lin, Y.; Huang, S.; Cai, Y. Evaluating the spatial-temporal impact of urban nature on urban vitality in vancouver: A social media and GPS data approach. Land Use Policy 2026, 160, 107824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Lee, S. Residential Built Environment and Walking Activity: Empirical Evidence of Jane Jacobs’ Urban Vitality. Transp. Res. Part D 2015, 41, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.X.; Shi, Y.S. The Influence Mechanism of Urban Spatial Structure on Urban Vitality Based on Geographic Big Data: A Case Study in Downtown Shanghai. Buildings 2022, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paköz, M.Z.; Yaratgan, D.; Şahin, A. Re-mapping urban vitality through jane jacobs’ criteria: The case of kayseri, turkey. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D.; Cai, T.; Zhang, Y. The Relationship between Urban Vibrancy and Built Environment: An Empirical Study from an Emerging City in an Arid Region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouratidis, K.; Poortinga, W. Built Environment, Urban Vitality and Social Cohesion: Do Vibrant Neighborhoods Foster Strong Communities? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Song, Y.; He, Q.; Shen, F. Spatially Explicit Assessment on Urban Vitality: Case Studies in Chicago and Wuhan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, T.; Xiao, R. Urban Vitality and Its Influencing Factors: Comparative Analysis Based on Taxi Trajectory Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 5102–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cai, Y.; Guo, S.; Sun, R.; Song, Y.; Shen, X. Evaluating implied urban nature vitality in san francisco: An interdisciplinary approach combining census data, street view images, and social media analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 95, 128289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.N.; Camanho, A.S. Public green space use and consequences on urban vitality: An assessment of European cities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Jin, Y.; Girling, C.; Wu, S. Indicators Shaping Urban Greenspace Spatial Performance in China: A Systematic Review of the Literature. World Dev. 2025, 195, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Jia, J.; Zhai, Y.; Tian, Y.; Xu, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ren, Z.; Ye, Z.; et al. Integrating Morphology and Vitality to Quantify Seasonal Contributions of Urban Functional Zones to Thermal Environment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 120, 106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Nordstrom, B.W.; Scholes, J.; Joncas, K.; Gordon, P.; Krivenko, E.; Haynes, W.; Higdon, R.; Stewart, E.; Kolker, N.; et al. A Case Study: Analyzing City Vitality with Four Pillars of Activity—Live, Work, Shop, and Play. Big Data 2016, 4, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahas, R.; Aasa, A.; Yuan, Y.; Raubal, M.; Smoreda, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ziemlicki, C.; Tiru, M.; Zook, M. Everyday space–time geographies: Using mobile phone-based sensor data to monitor urban activity in harbin, paris, and tallinn. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 29, 2017–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Long, Y.; Long, Y.; Xu, M. A New Urban Vitality Analysis and Evaluation Framework Based on Human Activity Modeling Using Multi-Source Big Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Garau, C. A Literature Review on the Assessment of Vitality and Its Theoretical Framework. Emerging Perspectives for Geodesign in the Urban Context. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2021; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Tarantino, E., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12958, pp. 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, H.Y.; Mou, Y.C.; Wang, D.; Hu, A. Optimal Block Size for Improving Urban Vitality: An Exploratory Analysis with Multiple Vitality Indicators. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 04021027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, M.; Pan, H. Using Multi-Source Geospatial Big Data to Identify the Structure of Polycentric Cities. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gou, P.; Xiong, J. Vital Triangle: A New Concept to Evaluate Urban Vitality. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 98, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Xu, L.; Zhao, K. Spatial Nonlinear Effects of Urban Vitality under the Constraints of Development Intensity and Functional Diversity. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 77, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, R.K.; Htike, K.M.; Sornlorm, K.; Koro, A.B.; Kafle, A.; Sharma, V. A Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis of Road Traffic Accidents by Severity Using Moran’s I Spatial Statistics: A Study from Nepal 2019–2022. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Shang, C.; Deng, X. Evolution of Urban Vitality Drivers from 2014 to 2022: A Case Study of Kunming, China. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 11459–11472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.G.; Miao, W. Urban Vitality Evaluation and Spatial Correlation Research: A Case Study from Shanghai, China. Land 2021, 10, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykostratis, K.; Giannopoulou, M.; Roukouni, A. Measuring Urban Configuration: A GWR Approach. In New Metropolitan Perspectives; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Bevilacqua, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 100, pp. 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulekan, A.; Jamaludin, S.S.S. Review on Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) Approach in Spatial Analysis. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2020, 16, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, X.; Shao, Z.; Wang, M.; Wu, H.; Zhao, H.; Gong, J.; Li, D. ST-GWLR: Combining Geographically Weighted Logistic Regression and Spatiotemporal Hotspot Trend Analysis to Explore the Effect of Built Environment on Traffic Crash. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 1017–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, T.; Das, A.; Pereira, P. Exploring the Drivers of Urban Expansion in a Medium-Class Urban Agglomeration in India Using Remote Sensing Techniques and Geographically Weighted Models. Geogr. Sustain. 2023, 4, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Wang, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Xue, L.; Cai, X.; Zhang, K. Relationship between the Built Environment and Urban Vitality of Nanjing’s Central Urban Area Based on Multi-Source Data. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2025, 52, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafri, N.M.; Khan, A. Using Geographically Weighted Logistic Regression (GWLR) for Pedestrian Crash Severity Modeling: Exploring Spatially Varying Relationships with Natural and Built Environment Factors. IATSS Res. 2023, 47, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Lai, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Identifying Tourists and Locals by K-Means Clustering Method from Mobile Phone Signaling Data. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2021, 147, 04021070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.H.; Peng, F.L.; Guo, T.F. Quantitative Assessment Method on Urban Vitality of Metro-Led Underground Space Based on Multi-Source Data: A Case Study of Shanghai Inner Ring Area. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 116, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamtrakul, P.; Chayphong, S.; Panuwatwanich, K. A Comprehensive Exploration of Urban Spatial Economic Vitality through the Application of the Node-Place Model. J. Urban Des. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, S.; Xia, C.; Tung, C.-L. Investigating the Effects of Urban Morphology on Vitality of Community Life Circles Using Machine Learning and Geospatial Approaches. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 167, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Bi, Y. Quantifying the Relationship between Land Use Intensity and Ecosystem Services’ Value in the Hanjiang River Basin: A Case Study of the Hubei Section. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.N.; Lv, Z.; Chen, C.M.; Liu, Q. Exploring Employment Spatial Structure Based on Mobile Phone Signaling Data: The Case of Shenzhen, China. Land 2022, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Wu, X.; He, Y. Exploring the Urban Structure of Recreational Spaces through Residents’ Mobility Behavior Using Mobile Phone Signaling Data. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 05025011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zheng, J. Assessing the Completeness and Positional Accuracy of OpenStreetMap in China. In Thematic Cartography for the Society; Bandrova, T., Konecny, M., Zlatanova, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Shi, H.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z. Diurnal Variation in the Urban Thermal Environment and Its Relationship to Human Activities in China: A Tencent Location-Based Service Geographic Big Data Perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 14218–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, H.; Duan, S.; Zhao, W.; Ren, H.; Liu, X.; Leng, P.; Tang, R.; Ye, X.; Zhu, J.; et al. Satellite Remote Sensing of Global Land Surface Temperature: Definition, Methods, Products, and Applications. Rev. Geophys. 2023, 61, e2022RG000777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, W.B.; Ren, J.Y.; Xiao, X.M.; Xia, J.C. Relationship between Urban Spatial Form and Seasonal Land Surface Temperature under Different Grid Scales. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikon, N.; Kumar, D.; Ahmed, S.A. Quantitative Assessment of Land Surface erature and Vegetation Indices on a Kilometer Grid Scale. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 107236–107258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C.; Sun, Y.R.; Chan, T.O.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, A.Y.; Liu, Z. Exploring Impact of Surrounding Service Facilities on Urban Vibrancy Using Tencent Location-Aware Data: A Case of Guangzhou. Sustainability 2021, 13, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, H.; Yang, X. An Evaluation of Street Dynamic Vitality and Its Influential Factors Based on Multi-Source Big Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lu, H.; Zheng, T.; Rong, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Y.; Tang, L. Vitality of Urban Parks and Its Influencing Factors from the Perspective of Recreational Service Supply, Demand, and Spatial Links. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Vuilliomenet, A. Urban Nature: Does Green Infrastructure Relate to the Cultural and Creative Vitality of European Cities? Sustainability 2021, 13, 8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Zeng, Z.; Huo, Z. How Do Subway Stations Encourage the Vitality of Urban Consumption Amenities in Shanghai: A Perspective on Agglomeration. J. Transp. Land Use 2025, 18, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, S.T.; Li, H.W.; Zhang, B.; Lv, J.R. Research on Geographical Environment Unit Division Based on the Method of Natural Breaks (Jenks). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, XL-4-W3, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.J.; Jiang, P.K.; Zhou, G.M.; Zhao, K.L. Using Moran’s I and GIS to Study the Spatial Pattern of Forest Litter Carbon Density in a Subtropical Region of Southeastern China. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2401–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węglarczyk, S. Kernel Density Estimation and Its Application. ITM Web Conf. 2018, 23, 00037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Seraj, R.; Islam, S.M.S. The K-Means Algorithm: A Comprehensive Survey and Performance Evaluation. Electronics 2020, 9, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Indicator (Abbreviation) | Calculation Method | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Environment Source: NASA LAADS DAAC (https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/) (accessed on 25 December 2019) | Winter Land Surface Temperature (W-LST) | : Land surface temperature of the i-th pixel : Number of pixels in the grid | °C | [62,63] |

| Summer Land Surface Temperature (S-LST) | °C | |||

| Natural Environment Source: Landsat 8 OLI, spatial resolution (http://www.usgs.gov/) (accessed on 25 December 2019) | Winter Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI-01) | : Near-infrared reflectance : Red reflectance Travel Purpose | Unitless | [64] |

| Summer Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI-07) | Unitless | |||

| Travel Purpose Source: Amap (https://www.amap.com) (accessed on 24 December 2019) and Open Street Map (https://www.openstreetmap.org/) (accessed on 24 December 2019) | Catering POI (CaterPOI) | : The i-th POI for a specific category : Number of POI in the grid. | POI/km2 | [65,66] |

| Transportation POI (TransPOI) | POI/km2 | |||

| Sports POI | POI/km2 | |||

| Company POI (ComPOI) | POI/km2 | |||

| Shopping POI (ShopPOI) | POI/km2 | |||

| Built Environment Source: Baidu Map (https://lbsyun.baidu.com/) (accessed on 24 December 2019) | Building Density (BD) | : Area of the i-th building : Total area of the grid. | % | [63] |

| Floor Area Ratio (FAR) | : The total building area in grid : The land area in grid , | Unitless | ||

| Distance to Park (NDP) | : Park location : Points within the grid. | m | [67] | |

| Distance to Waterbody (NDW) | : Waterbody location : Points within the grid. | m | [68] | |

| Distance to Subway (NDS) | : Subway station location : Points within the grid. | m | [69] |

| Level | Steady-State Vitality Zone | Value Range |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Low Vitality Zone | 0–0.042 |

| Level 2 | Relatively Low Vitality Zone | 0.042–0.112 |

| Level 3 | Moderate Vitality Zone | 0.112–0.204 |

| Level 4 | Relatively High Vitality Zone | 0.204–0.356 |

| Level 5 | High Vitality Core Zone | 0.356–1.000 |

| Level | Dynamic Vitality Zone | Value Range (per/km2) |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Low Vitality Zone | 0–97 |

| Level 2 | Relatively Low Vitality Zone | 97–269 |

| Level 3 | Moderate Vitality Zone | 269–442 |

| Level 4 | Relatively High Vitality Zone | 442–647 |

| Level 5 | High Vitality Core Zone | 647–1127 |

| DVC | Temporal Characteristics | Figure |

|---|---|---|

| RDVC-1/WDVC-1 | The VFI values on both working days and rest days remain consistently high, thereby demonstrating the characteristic of continuous population aggregation | Figure 8a RDVC-1; Figure 8b WDVC-1 |

| RDVC-2 | On rest days, VFI amplitude > 1.5σ, indicating significant crowd fluctuations | Figure 8c RDVC-2 |

| WDVC-2 | On weekdays VFI standard deviation < 0.3, indicating relatively stable crowd fluctuations within specific areas | Figure 8d WDVC-2 |

| RDVC-3/WDVC-3 | crowd changes exhibit pronounced bimodal fluctuations | Figure 8e RDVC-3; Figure 8f WDVC-3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, X.; Li, K.; Xie, D.; Fang, Y. Research on Urban Spatial Environment Optimization Based on the Combined Influence of Steady-State and Dynamic Vitality: A Case Study of Wuhan City. Land 2025, 14, 2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122427

Tang X, Li K, Xie D, Fang Y. Research on Urban Spatial Environment Optimization Based on the Combined Influence of Steady-State and Dynamic Vitality: A Case Study of Wuhan City. Land. 2025; 14(12):2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122427

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Xiaoxue, Kun Li, Dong Xie, and Yuan Fang. 2025. "Research on Urban Spatial Environment Optimization Based on the Combined Influence of Steady-State and Dynamic Vitality: A Case Study of Wuhan City" Land 14, no. 12: 2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122427

APA StyleTang, X., Li, K., Xie, D., & Fang, Y. (2025). Research on Urban Spatial Environment Optimization Based on the Combined Influence of Steady-State and Dynamic Vitality: A Case Study of Wuhan City. Land, 14(12), 2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122427