Assessing the Multifunctional Potential and Performance of Cultivated Land in Historical Irrigation Districts: A Case Study of the Mulanbei Irrigation District in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Identification of Multifunctionality in Cultivated Land Within HIDs

2.3. Assessing the Multifunctional Potential of Cultivated Land in HIDs

2.4. Assessment of Multifunctional Performance of Cultivated Land in HIDs

- Production Function

- 2.

- Ecological Function

- 3.

- Social Function

- 4.

- Landscape and Cultural Function

2.5. Spatial Matching of Multifactional Potential and Performance of Cultivated Land in HIDs

2.6. Study Area

2.7. Data Sources

3. Results

3.1. Multifunctional Potential of Cultivated Land in the HIDs and Its Spatial Distribution Characteristics

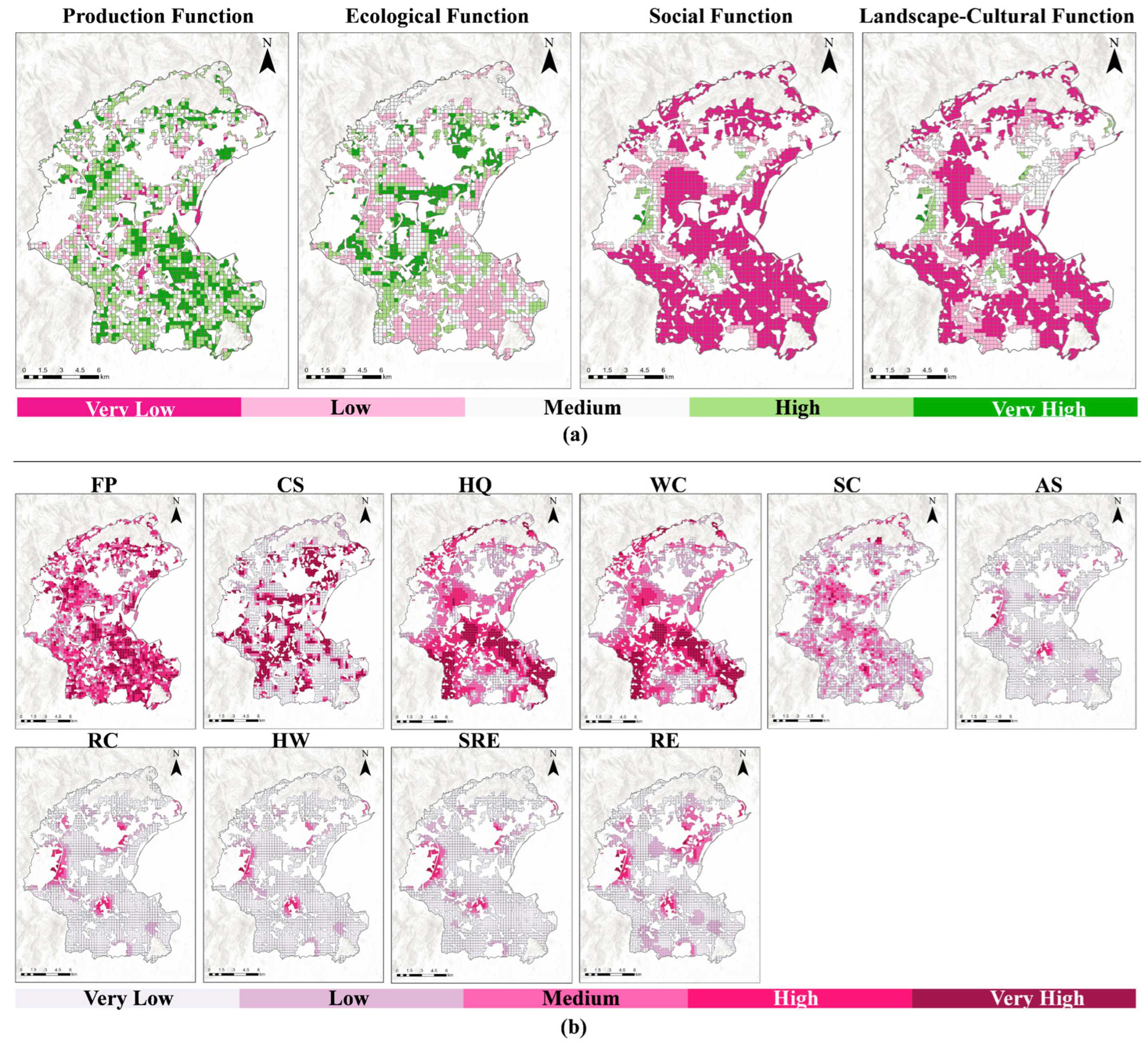

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution of Multifunctional Potential of Cultivated Land

3.1.2. Spatial Distribution of Influencing Factors for the Multifunctional Potential of Cultivated Land

3.2. Multifunctional Performance of Cultivated Land in the HIDs and Its Spatial Distribution Characteristics

3.2.1. Spatial Distribution of Multifunctional Performance of Cultivated Land

3.2.2. Spatial Distribution of Representative Function for the Multifunctional Performance of Cultivated Land

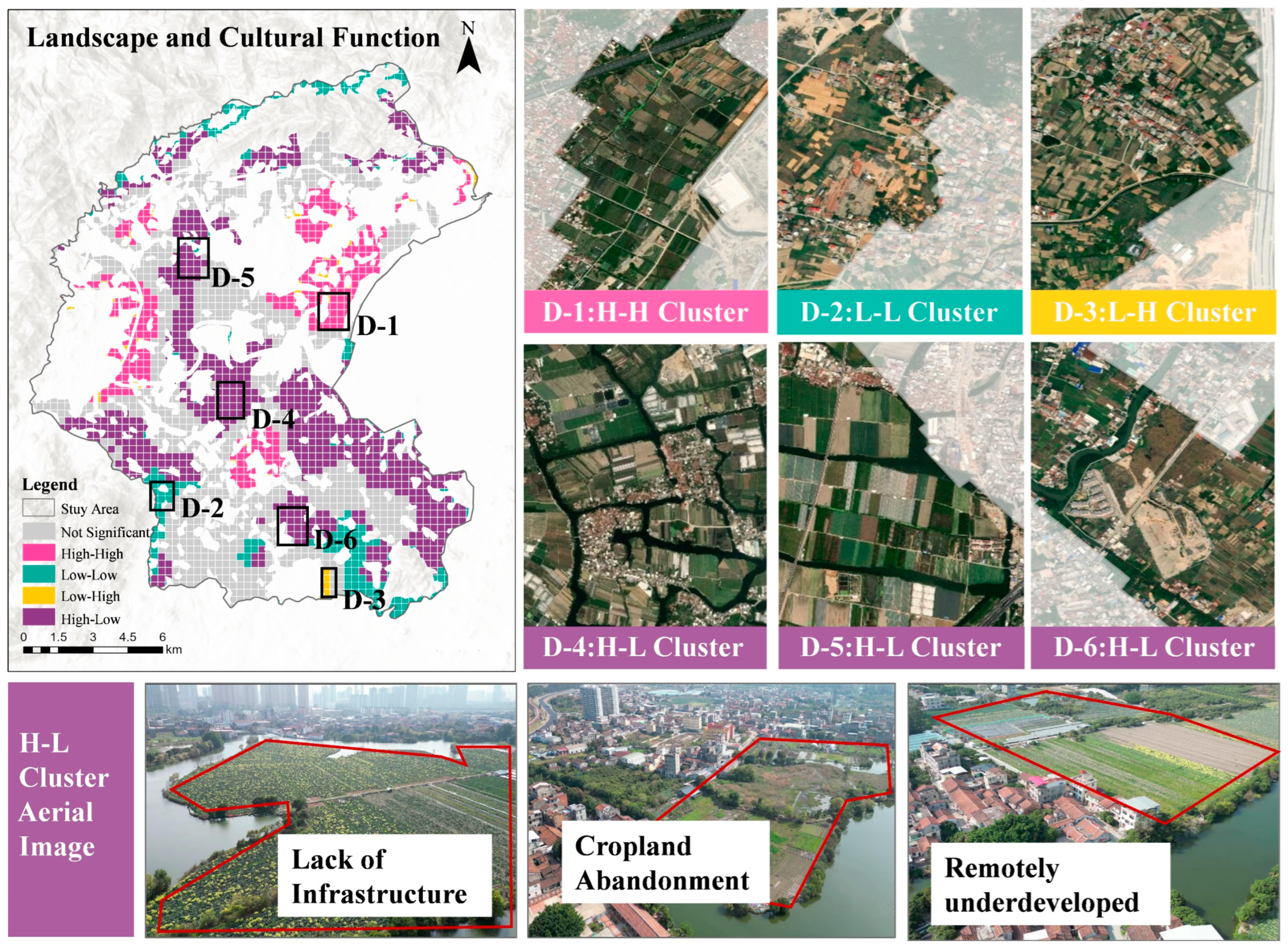

3.3. Spatial Matching Analysis Between Multifunctional Potential and Performance of Cultivated Land in HID

3.3.1. Production Function

3.3.2. Ecological Function

3.3.3. Social Function

3.3.4. Landscape–Cultural Function

4. Discussion

4.1. Driving Factors of Performance Differences in Cultivated Land Multifunction

4.2. Implications of the Potential–Performance Framework for Cultivated Land Multifunction

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cultivated Land Multifunctionality | Representative Function | Keyword | Relevant Sentence | Source |

| Production Function | Food Production | Farmland; Irrigation | Vast expanses of once barren, saline land were converted into highly productive farmland. | The Water Conservancy Annals of Putian, Volume 2 |

| The farmland outside the city relied completely on the water stored in this lake for irrigation. | The Joint Petition by Gentry and Scholars including Chen Danchi in the Sixth Month of the Sixth Year of the Kangxi Reign | |||

| Social Function | Residential Carrying Capacity | Family; Livelihood | Thanks to effective water management, the farmlands were protected from flooding and salinization, ensuring the livelihood and stability of numerous families, who thus praised the benevolent governance of the dynasty | Rhapsody on Mulanbei |

| Families owning numerous fields near the canals | Record of Repairing Lakes and Canals | |||

| Agricultural Product Services | Trade; Benefit | He then instructed his fellow villagers, based on his experience, to manage the Putian area—a former saline land—by having the people engage in excavation and trade | Xinghua Prefecture Putian County Gazetteer, Volume 2 | |

| Planting mulberry, hemp, reeds, and similar species to check water flow, thereby benefiting the people who profited from these livelihoods | Huzhou City Gazetteer | |||

| Healthcare and Wellness | Healthcare; Cultivation | Integrating agricultural production with healthcare services to serve health intervention functions | Luo et al. [71] | |

| Combining rice cultivation with care services to promote social participation among care recipients and optimize the quality of care | Ura et al. [72] | |||

| Ecological Function | Habitat Quality | Egret; Islets float | The stone embankments and sand dykes curb the sea’s force, while teals and mandarin ducks dart amidst the vibrant spring scenery | Mulanbei |

| Islets float upon the water’s surface, gathering abundant wild ducks and egrets on solitary spits | Memorial to Governor on Dredging the West Lake | |||

| Water Conservation | water | The Mulanbei irrigates ten thousand qing of farmland, and every year the people drink from its water | Xinghua Prefecture Putian County Gazetteer, Volume 2 | |

| Water flows outside the polder dykes, while fertile fields are formed within them | Chinese Historical Hydraulic Archives: Taihu Lake and Southeast China, Volume 2 | |||

| Carbon Sequestration | Oxygen; Carbon | Its water systems circulate, oxygen converges, and it boosts local vitality while broadly benefiting the people and all living things. | Letter to Lu Laizang on Irrigation Management | |

| Farmland ecosystems play a significant role in the carbon cycle of terrestrial ecosystems | Sun et al. [73] | |||

| Soil Conservation | Soil; Polder Dyke | At the ends of fields facing the ditches, soil was piled into mounds about a foot high for protection. | Xinghua Prefecture Putian County Gazetteer, Volume 2 | |

| Consequently, polder dykes were built adjacent to the city, creating fertile farmland in the Wu region | Guangxu Gaochun County Gazetteer | |||

| Landscape and Cultural Function | Recreation and Ecotourism | Scenery | From then on, boats and ships connected the waterways, fields stretched far into the distance, and the scenery rivaled that of Jiangnan | The Water Conservancy Annals of Putian, Volume 1 |

| These channels connected like veins, distributed vertically and horizontally, resembling the scenery of the well-field system. | Chronicles of Seawall Defense | |||

| Scientific Research and Education | Scientific; Education | Educational and scientific research services provided by farmland to humanity | Ecological Product Catalog (2024 Edition) | |

| As a result, governance and education were extensively implemented. | Study on Water Conservancy of Fuzhou City Rivers |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. The Multifunctional Potential of Cultivated Land

Appendix B.1.1. Production Function

| Production Function | Geographical Factor | Infrastructure Factor | Historical Factor |

| Geographical Factor | 1 | - | - |

| Infrastructure Factor | 11/7 | 1 | - |

| Historical Factor | 3/5 | 5/8 | 1 |

| Geographical Factor | Slope | Elevation |

| Slope | 1 | - |

| Elevation | 1/3 | 1 |

| Infrastructure Factor | Density of Field Roads | Distance from Cultivated Land to Highways | Distance from Cultivated Land to Rural Settlements |

| Density of Field Roads | 1 | - | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Highways | 25/9 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Rural Settlements | 3 | 11/9 | 1 |

| Historical Factor | Soil Fertility | Density of Irrigation Canals | Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites |

| Soil Fertility | 1 | - | - |

| Density of Irrigation Canals | 25/9 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites | 3 | 11/9 | 1 |

Appendix B.1.2. Ecological Function

| Ecological Function | Geographical Factor | Land Management Factor |

| Geographical Factor | 1 | - |

| Land Management Factor | 1 | 1 |

| Geographical Factor | Slope | Elevation |

| Slope | 1 | - |

| Elevation | 3/5 | 1 |

| Land Management Factor | Cultivated Land Aggregation Index | Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land |

| Cultivated land Aggregation Index | 1 | - | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | 1/2 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land | 3/8 | 5/6 | 1 |

Appendix B.1.3. Social Function

| Social Function | Infrastructure Factor | Land Management Factor | Historical Factor |

| Infrastructure Factor | 1 | - | - |

| Land Management Factor | 3/5 | 1 | - |

| Historical Factor | 4/5 | 4/5 | 1 |

| Infrastructure Factor | Density of Field Roads | Distance from Cultivated Land to Highways | Distance from Cultivated Land to Rural Settlements |

| Density of Field Roads | 1 | - | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Highways | 31/6 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Rural Settlements | 32/3 | 12/5 | 1 |

| Land Management Factor | Cultivated Land Aggregation Index | Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land |

| Cultivated land Aggregation Index | 1 | - | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | 11/7 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land | 8/9 | 4/5 | 1 |

| Historical Factor | Soil Fertility | Density of Irrigation Canals | Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites |

| Soil Fertility | 1 | - | - |

| Density of Irrigation Canals | 13/7 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites | 11/3 | 13/8 | 1 |

Appendix B.1.4. Landscape–Cultural Function

| Landscape–Cultural Function | Geographical Factor | Land Management Factor | Historical Factor |

| Geographical Factor | 1 | - | - |

| Land Management Factor | 11/3 | 1 | - |

| Historical Factor | 25/9 | 23/4 | 1 |

| Geographical Factor | Slope | Elevation |

| Slope | 1 | - |

| Elevation | 3/5 | 1 |

| Land Management Factor | Cultivated Land Aggregation Index | Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land |

| Cultivated land Aggregation Index | 1 | - | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | 1 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land | 5/7 | 3/4 | 1 |

| Historical Factor | Soil Fertility | Density of Irrigation Canals | Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites |

| Soil Fertility | 1 | - | - |

| Density of Irrigation Canals | 24/7 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites | 31/2 | 21/4 | 1 |

Appendix B.2. The Multifunctional Performance of Cultivated Land

Appendix B.2.1. Production Function Performance of Cultivated Land

| Production Function | Food Production |

| Food production | 31/2 |

Appendix B.2.2. Ecological Function Performance of Cultivated Land

| Ecological Function | Habitat Quality | Water Conservation | Soil Conservation | Carbon Sequestration |

| Habitat Quality | 1 | - | - | - |

| Water Conservation | 11/3 | 1 | - | - |

| Soil Conservation | 11/4 | 11/6 | 1 | - |

| Distance from Carbon Sequestration | 2/3 | 3/5 | 5/7 | 1 |

Appendix B.2.3. Social Function Performance of Cultivated Land

| Social Function | Residential Carrying Capacity | Agricultural Produce Services | Healthcare and Wellness |

| Residential Carrying Capacity | 1 | - | - |

| Agricultural Product Services | 1/2 | 1 | - |

| Healthcare and wellness | 1/3 | 2/3 | 1 |

Appendix B.2.4. Landscape–Cultural Function Performance of Cultivated Land

| Landscape-Cultural Function | Scientific Research and Education | Recreation and Ecotourism |

| Scientific Research and Education | 1 | - |

| Recreation and Ecotourism | 2/5 | 1 |

References

- UNESCO Bangkok. UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation; UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. World Heritage irrigation structure and its protection significance analysis. China Water Resour. 2020, 2020, 47–49+53. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Sun, J.; Ji, W.; Hou, X. Landscape of the Irrigation Districts: Traditional Landscape Camping in the Perspective of Territorial Spatial Development. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2023, 38, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X. Global understanding of farmland abandonment: A review and prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1123–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Nijhuis, S.; Tillie, N. Optimizing urban agriculture for long-term ecosystem services: Integrating scenario-based suitability analysis and the landscape approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 536, 147149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, U.K.; Karim, F.; Yu, Y.; Ghosh, A.; Zahan, T.; Mallick, S.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Paul, P.L.C.; Mainuddin, M. Assessing vulnerability and climate risk to agriculture for developing resilient farming strategies in the Ganges Delta. Clim. Risk Manag. 2025, 47, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanir, T.; Yildirim, E.; Ferreira, C.M.; Demir, I. Social vulnerability and climate risk assessment for agricultural communities in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H. Theorizing land use transitions: A human geography perspective. Habitat Int. 2022, 128, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Ouyang, Z. Changes of cultivated land function in China since 1949. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Zhang, X.; He, J.; Zhou, X.; Zou, Q.; Zhang, P. Spatial differentiation of cropland multifunctionality trade-offs and their drivers across urban-rural gradients: A case study of major grain-producing areas, China. Habitat Int. 2026, 167, 103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Ouyang, Z. Connotation of multifunctional cultivated land and its implications for cultivated land protection. Prog. Geogr. 2012, 31, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Natural Resources Management and Environment Department. Taking stock of the multifunctional character of agriculture and land. In Proceedings of the FAO/Netherlands Conference on the Multifunctional Character of Agriculture and Land, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 12–17 September 1999; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Multifunctionality: Towards an Analytical Framework; OECD: Paris, France, 2001; pp. 1–157. ISBN 92-64-18625-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, W. International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD): Global Program Review; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, B.; Zhang, L. Land-use change and ecosystem services: Concepts, methods and progress. Prog. Geogr. 2014, 33, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liccari, F.; Boscutti, F.; Bacaro, G.; Sigura, M. Connectivity, landscape structure, and plant diversity across agricultural landscapes: Novel insight into effective ecological network planning. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.; Hamerlinck, J.; McKinlay, A. Institutional support for building resilience within rural communities characterised by multifunctional land use. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.J.; Kumar, G.; Sharma, N.K.; Deshwal, J.S.; Mishra, M.; Roy, P.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Madhu, M. Conservation tillage-based Arundo donax agro-geotextiles enhance productivity and profitability of sloping croplands in the Indian Himalayas by reducing soil erosion and improving soil organic carbon. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. The process and driving forces of change in arable-land area in the Yangtze River Delta during the past 50 years. J. Nat. Resour. 2001, 16, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Du, J.; Shen, Z.; El Asraoui, H.; Song, M. Effects of modern agricultural demonstration zones on cropland utilization efficiency: An empirical study based on county pilot. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Zhang, F.; Kong, X.; Qin, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X. The different levels and the protection of multi-functions of cultivated land. China Land Sci. 2011, 25, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ma, E.; Ji, Y. Multifunctional spatiotemporal evolution and its inter-regional coupling of cultivated land in a typical transect in Northern China. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobert, F.; Schwieder, M.; Hostert, P.; Gocht, A.; Erasmi, S. Characterizing spatio-temporal patterns of winter cropland cover in Germany based on Landsat and Sentinel-2 time series. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 142, 104728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, P.; Ahmadi Nadoushan, M.; Besalatpour, A. Cropland abandonment in a shrinking agricultural landscape: Patch-level measurement of different cropland fragmentation patterns in Central Iran. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 158, 103023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Huang, J.; Luo, C.; Fang, M.; Xu, X.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, L. Deciphering supply-demand mismatch and influencing mechanisms of cropland multifunction in China: Toward targeted spatial governance. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 527, 146719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Zhang, J.; Dong, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, T.; Qian, Z.; Ma, X.; Sun, F. Spatial heterogeneity in cropland multifunctionality trade-offs and their drivers: A case study of the Huaihai Economic Zone, China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 107, 107569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Ren, J.; Wang, H.; Shi, Z.; Wang, J. How to transform cultivated land protection on the Northeast Tibetan Plateau ? A multifunctional path exploration. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 112988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Wu, S.; Yan, Z.; Han, J. Cultivated land multifunctionality in undeveloped peri-urban agriculture areas in China: Implications for sustainable land management. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, X. Inhibit or promote: Spatial impacts of multifunctional farmland use transition on grain production from the perspective of major function-oriented zoning. Habitat Int. 2024, 152, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonato, M.; Burian, A.; Equihua, J.A.; Cord, A.F.; Bartkowski, B.; Strauch, M. Minimizing trade-offs in agricultural landscapes through optimal spatial allocation of agri-environmental practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 126939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Ye, C.; Cai, Y.; Xing, X.; Chen, Q. The impact of rural out-migration on land use transition in China: Past, present and trend. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Li, Y. Key issues of land use in China and implications for policy making. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jin, X.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Fan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. How to achieve adaptive optimization of cultivated land multifunctionality? Insights from coupled supply-utilization-demand interactions. Habitat Int. 2025, 164, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Q.; Guo, W. Genesis and characteristics of the traditional human settlement system of polder fields in the Xitiaoxi River Basin. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, S. The Noordoostpolder: A Landscape Planning Perspective on the Preservation and Development of Twentieth-Century Polder Landscapes in the Netherlands. In Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage: Past, Present and Future; Hein, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 212–229. [Google Scholar]

- da-Silva-Branco, C.; de Brito, A.G.; Seixas, P.C. A comprehensive review of traditional irrigation systems: Sustainability and future prospects. Agric. Syst. 2026, 231, 104481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.R.V.; Börjesson, P.; Smith, H.G. Understanding land use impacts of croplands on biodiversity through UNEP’s Global Guidance for Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 222, 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, W.; Gu, H. Ecological restoration effect of paddy fields after rice planting pattern transformation in the rural wetlands of Chenhaiwei, Jiangsu Province. J. East China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 2020, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansen, N.; Petersen, R.J.; Hoffmann, C.C.; Kjeldgaard, A.; Thodsen, H.; Zak, D.H.; Kronvang, B.; Larsen, S.E.; Audet, J. Long-term evidence of nitrogen removal from four decades of wetland restoration in agricultural landscapes in Denmark. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2026, 395, 109924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Guo, W. Polder landscape study: Discussion on form, function and impact. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 22, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckscher, E.F.; Ohlin, B.G. Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Theory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlin, B.G. Interregional and International Trade; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, L.; Cao, S.; Wei, Y.; Xie, G.; Li, F.; Li, Y. Land use functions: Conceptual framework and application for China. Resour. Sci. 2009, 31, 544–551. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Luo, W. Ecological product zoning method and governance path based on “potentiality--suitability” coupling. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2024, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, X. Influence of livelihood capitals on landscape service cognition and behavioral intentions in rural heritage sites. Land 2024, 13, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, C.; Ren, W.; Wang, X. Study on the landscape multifunctionality and multi-subject game in the Fuzhou West Lake water heritage. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y. Theory building and empirical research of production-living-ecological function of cultivated land based on the elements. Geogr. Res. 2021, 40, 839–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shi, D. Spatio-temporal variation in soil erosion on sloping farmland based on the integrated valuation of ecosystem services and trade-offs model: A case study of Chongqing, southwest China. CATENA 2024, 236, 107693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Liu, T. Study on the landscape pattern of southwest transition zone from mountainous to hilly areas under the influence of multi-dimensional terrain factors: A case study of the middle and upper reaches of Fujiang River Basin. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2020, 36, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Mu, W.; Luo, W. Soil fertility and influencing factors of cultivated land based on the Geodetector. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 7378–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, Q. Traditional Chinese mountain-water-field-city system from the perspective of territorial landscape. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 25, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Hu, W.; Zhao, Z. Dynamic analysis on spatial-temporal pattern of trade-offs and synergies of multifunctional cultivated land---Evidence from Hubei Province. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 38, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heringa, P.W.; van der Heide, C.M.; Heijman, W.J.M. The economic impact of multifunctional agriculture in Dutch regions: An input-output model. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2013, 64–65, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Wang, Q.; Bian, Z.; Yang, Z.; Kang, M. Site condition assessment during prime farmland demarcating. J. Nat. Resour. 2016, 31, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, L.; Lü, H.; He, X. Soil fertility evaluation for urban forests and green spaces in Changchun City. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, S.; Aftab, A.; Xie, J.; Han, L. Development of a simplified health assessment method for saline cultivated land using soil and crop indicators. Geoderma 2025, 463, 117557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, K.; Rodela, R.; Lehtilä, K. Indicators of visual and ecological complexity of urban wetlands and lakes in Stockholm. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 181, 114362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liu, L.; Su, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, J. Multifunctional trade-off/synergy relationship of cultivated land in Guangdong: A long time series analysis from 2010 to 2030. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Ehrlich, A.H. The causes and consequences of the disappearance of species. Q. Rev. Biol. 1981, 56, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- van Zanten, B.T.; Verburg, P.H.; Espinosa, M.; Gomez-y-Paloma, S.; Galimberti, G.; Kantelhardt, J.; Kapfer, M.; Lefebvre, M.; Manrique, R.; Piorr, A.; et al. European agricultural landscapes, common agricultural policy and ecosystem services: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Cao, X.J.; Huang, X.; Cao, X. Applying the IPA--Kano model to examine environmental correlates of residential satisfaction: A case study of Xi’an. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Lin, T.; Zhang, G.Q.; Jones, L.; Xue, X.Z.; Ye, H.; Liu, Y.Q. Spatiotemporal patterns and inequity of urban green space accessibility and its relationship with urban spatial expansion in China during rapid urbanization period. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 151123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Lin, T.; Zhang, G.Q.; Zhu, Y.G.; Zeng, Z.W.; Ye, H. Spatial patterns of urban green space and its actual utilization status in China based on big data analysis. Big Earth Data 2021, 5, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, T.; Zeng, Z.; Geng, H. Green infrastructuration and characteristics of suburban cropland from a zonal perspective. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Peng, J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y. Tradeoffs and synergies between ecosystem services in Ordos City. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.; Fonseca, C.; Vergílio, M.; Calado, H.; Gil, A. Spatial assessment of habitat conservation status in a Macaronesian island based on the InVEST model: A case study of Pico Island (Azores, Portugal). Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wu, X.; Wen, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, F.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, J. Ecological security pattern based on XGBoost-MCR model: A case study of the Three Gorges Reservoir Region. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, K.G. Predicting Soil Erosion by Water: A Guide to Conservation Planning with the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE); U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; Volume Agricultural Handbook No. 703.

- Porter, J.; Costanza, R.; Sandhu, H.; Sigsgaard, L.; Wratten, S. The value of producing food, energy, and ecosystem services within an agro-ecosystem. MBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2009, 38, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wan, C.; Xu, G.; Chen, L.; Yang, C. Exploring the relationship and influencing factors of cultivated land multifunction in China from the perspective of trade-off/synergy. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 149, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; He, Q. Multi-functional spatiotemporal evolution of cultivated land and its driving mechanisms in Poyang Lake Plain. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 43, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.A.P. The interpretation of statistical maps. J. R. Stat. Society. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1948, 10, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabbagh, T.A.; Mohamadi, B.; Abu Ghazala, M.O.; Younes, A. Land use as a target for terrorism: A geospatial and temporal framework of terrorist preferences analysis in Egypt. Land Use Policy 2026, 160, 107822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. AQUASTAT – Global Maps: Irrigated Areas. Available online: https://www.fao.org/aquastat/zh/geospatial-information/global-maps-irrigated-areas/irrigation-by-country/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Zhu, C.; Li, W.; Du, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S. Spatial-temporal change, trade-off and synergy relationships of cropland multifunctional value in Zhejiang Province, China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Jin, X.; Xiang, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Evaluation and spatial characteristics of arable land multifunction in southern Jiangsu. Resour. Sci. 2018, 40, 980–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Lin, L.; Luo, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Guan, J. Spatiotemporal pattern and driving force analysis of multi-functional coupling coordinated development of cultivated land. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yun, W.; Tang, H.; Xu, Y. Analysis on spatial differentiation of arable land multifunction and socio-economic coordination model in Beijing. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Xing, L.; Dou, C. Multifunctional evaluation and multiscenario regulation of non-grain farmlands from the grain security perspective: Evidence from the Wuhan Metropolitan Area, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 146, 107322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, H.; Ma, L.; Ge, D.; Tu, S.; Qu, Y. Farmland function evolution in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain: Processes, patterns and mechanisms. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zou, R.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, Y.; Tan, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, A.-X.; Gong, J.; Mao, X. Sustainable utilization of cultivated land resources based on “element coupling-function synergy” analytical framework: A case study of Guangdong, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 146, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, C.; Yan, W. Mechanism and pattern of polders in the Yangtze River Delta: Effective physical form for ecosystem services provision. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 25, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

| Cultivated Land Multifunctionality | Criterion Layer | Criterion Weight | Indicator Layer | Global Weight | Indicator Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production Function | Geographical Factor | 0.3291 | Slope | 0.2468 | − |

| Elevation | 0.0823 | − | |||

| Infrastructure Factor | 0.4376 | Density of Field Roads | 0.0645 | + | |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Highways | 0.1717 | − | |||

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Rural Settlements | 0.2014 | − | |||

| Historical Factor | 0.2333 | Soil Fertility | 0.1183 | + | |

| Density of Irrigation Canals | 0.0859 | + | |||

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites | 0.0291 | − | |||

| Ecological Function | Geographical Factor | 0.5000 | Slope | 0.3125 | − |

| Elevation | 0.1875 | − | |||

| Land Management Factor | 0.5000 | Cultivated land Aggregation Index | 0.2671 | + | |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | 0.1290 | − | |||

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land | 0.1038 | − | |||

| Social Function | Infrastructure Factor | 0.4182 | Density of Field Roads | 0.0244 | + |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Highways | 0.1201 | − | |||

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Rural Settlements | 0.2737 | − | |||

| Land Management Factor | 0.2985 | Cultivated land Aggregation Index | 0.0879 | + | |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | 0.1229 | − | |||

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land | 0.0877 | − | |||

| Historical Factor | 0.2833 | Soil Fertility | 0.0442 | + | |

| Density of Irrigation Canals | 0.0875 | + | |||

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites | 0.1516 | − | |||

| Landscape–Cultural Function | Geographical Factor | 0.1360 | Slope | 0.0850 | − |

| Elevation | 0.0510 | − | |||

| Land Management Factor | 0.2494 | Cultivated land Aggregation Index | 0.0921 | + | |

| Distance from Cultivated Land to the Central Urban Area | 0.0906 | − | |||

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Other Construction Land | 0.0668 | − | |||

| Historical factor | 0.6146 | Soil Fertility | 0.0299 | + | |

| Density of Irrigation Canals | 0.0977 | + | |||

| Distance from Cultivated Land to Historical Sites | 0.4870 | − |

| Cultivated Land Multifunctionality | Criterion Layer | AHP Weight | Function Weight | Global Weight | Indicator Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production Function | Food production | 1 | 0.4037 | 0.4037 | + |

| Ecological Function | Habitat Quality | 0.1513 | 0.3357 | 0.0508 | + |

| Water Conservation | 0.3077 | 0.1033 | + | ||

| Soil Conservation | 0.3669 | 0.1232 | + | ||

| Carbon Sequestration | 0.1741 | 0.0584 | + | ||

| Social Function | Residential Carrying Capacity | 0.2728 | 0.1081 | 0.0295 | + |

| Agricultural Product Services | 0.5455 | 0.0589 | + | ||

| Healthcare and wellness | 0.1819 | 0.0197 | + | ||

| Landscape–Cultural Function | Scientific Research and Education | 0.7143 | 0.1525 | 0.1089 | + |

| Recreation and Ecotourism | 0.2857 | 0.0436 | + |

| Data | Data Description | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Land use (Landsat 8) | Land use data with resolution of 30 m in 2020 | The Centre for Resource and Environmental Science and Data of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.resdc.cn/) (accessed on 24 July 2024) |

| DEM | DEM with resolution of 30 m in 2020 | U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-nasadem-hgt-001) (accessed on 24 July 2024) |

| Soil data | Soil depth data with resolution of 1 km in 2020 | The World Soil Database (https://gaez.fao.org/pages/hwsd) (accessed on 25 July 2024) |

| Meteorological data | Daily observation data of meteorological station from January to December in 2020 | National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/71ab4677-b66c-4fd1-a004-b2a541c4d5bf) (accessed on 25 July 2024) |

| NPP (MODIS) | NPP with resolution of 500 m in 2020 | NASA’s Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod17a3hgfv061/) (accessed on 24 July 2024) |

| NDVI (Landsat 5/7/8/9) | NDVI with resolution of 30 m in 2020 | National Ecosystem Science Data Center (http://www.nesdc.org.cn) (accessed on 24 July 2024) |

| Grain production | Crop Yield in 2020 | Putian Statistical Yearbook 2021 (https://www.putian.gov.cn/tjnj/pttjnj2021.htm) (accessed on 24 July 2024) |

| Road networks | Roads and waterways | OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org/)(accessed on 24 July 2024) (accessed on 26 July 2024) |

| POI | 1 km buffer surrounding each cultivated land grid | Gaode Maps (https://lbs.amap.com/) (accessed on 24 July 2024) |

| Cultivated Land Multifunctionality | Production Function | Ecological Function | Social Function | Landscape–Cultural Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-H Cluster | 19% | 20% | 10% | 12% |

| L-L Cluster | 4% | 4% | 10% | 13% |

| H-L Cluster | 6% | 4% | 33% | 27% |

| L-H Cluster | 4% | 3% | 2% | 3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lin, T. Assessing the Multifunctional Potential and Performance of Cultivated Land in Historical Irrigation Districts: A Case Study of the Mulanbei Irrigation District in China. Land 2025, 14, 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122421

Zhu Y, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Lin T. Assessing the Multifunctional Potential and Performance of Cultivated Land in Historical Irrigation Districts: A Case Study of the Mulanbei Irrigation District in China. Land. 2025; 14(12):2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122421

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yuting, Zukun Zhang, Xuewei Zhang, and Tao Lin. 2025. "Assessing the Multifunctional Potential and Performance of Cultivated Land in Historical Irrigation Districts: A Case Study of the Mulanbei Irrigation District in China" Land 14, no. 12: 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122421

APA StyleZhu, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhang, X., & Lin, T. (2025). Assessing the Multifunctional Potential and Performance of Cultivated Land in Historical Irrigation Districts: A Case Study of the Mulanbei Irrigation District in China. Land, 14(12), 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122421