Modeling the Multiple Driving Mechanisms and Dynamic Evolution of Urban Inefficient Land Redevelopment: An Integrated SEM-FCM Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Multiple Stakeholders in UILR

2.2. Multiple Driving Factors and Mechanisms of UILR

2.3. SEM and FCM Methods

3. Methodology

3.1. SEM Framework Specification

3.2. SEM Validation

3.3. FCM Model Construction

3.4. FCM Simulation Analysis

4. Model Establishment

4.1. Identification of Driving Factors

4.1.1. Classification of Driving Factors

4.1.2. Identification of Relevant Variables

4.2. Research Hypotheses and Path Model

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Reliability and Validity Assessment

4.5. Hypothesis Testing and Path Analysis

4.6. FCM Model Development

5. Results of FCM Analysis

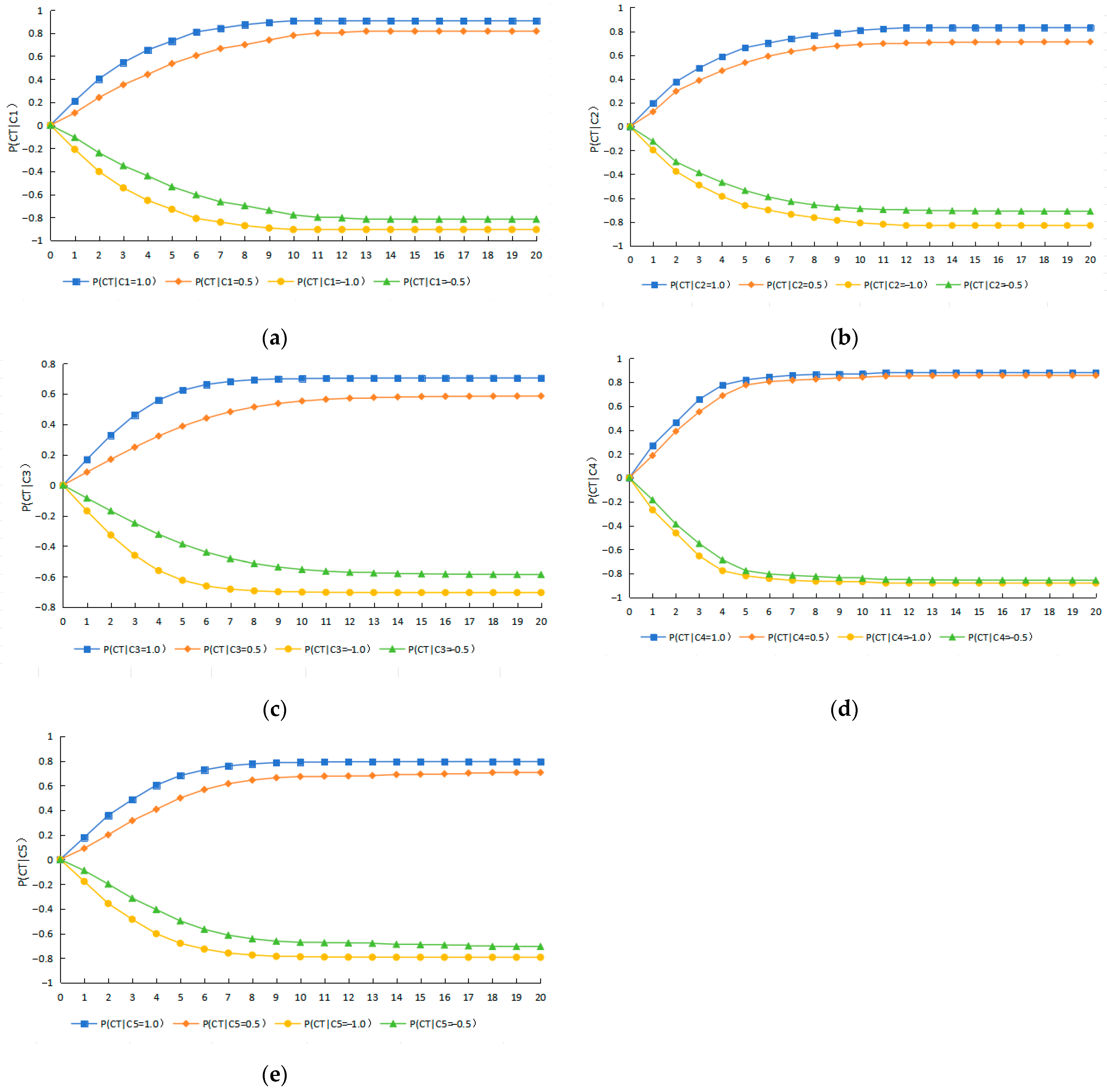

5.1. Predictive Analysis

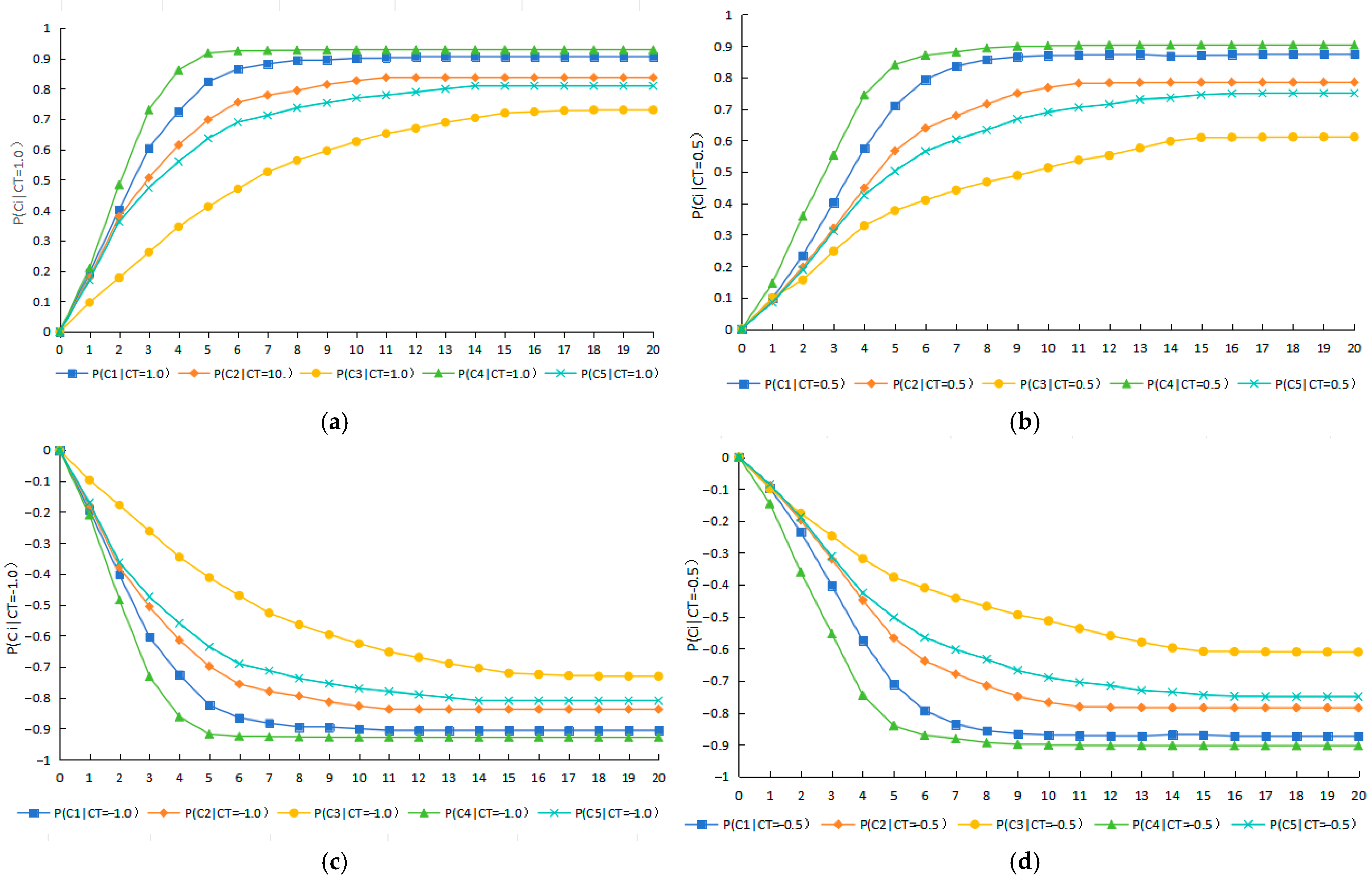

5.2. Diagnostic Analysis

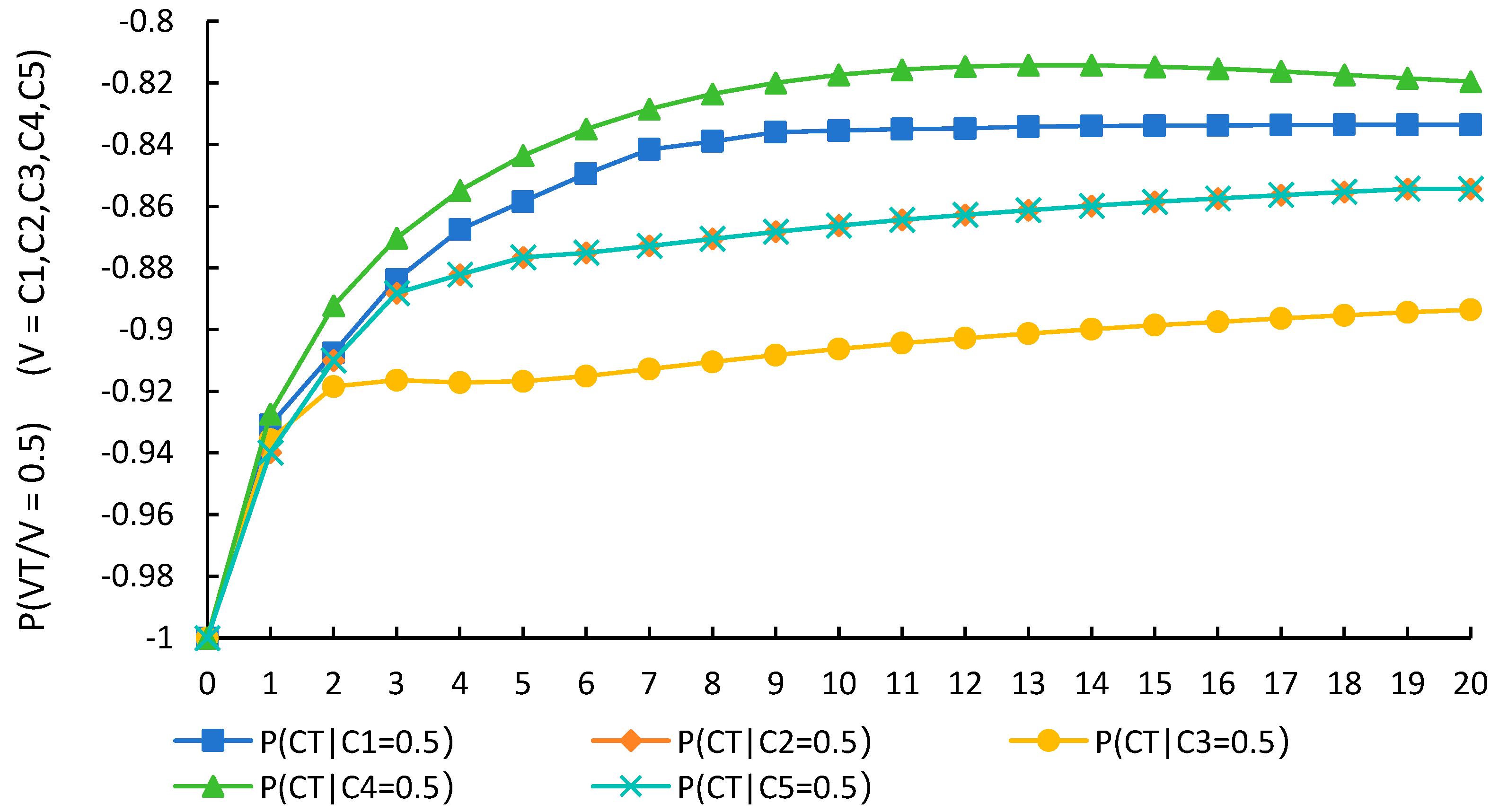

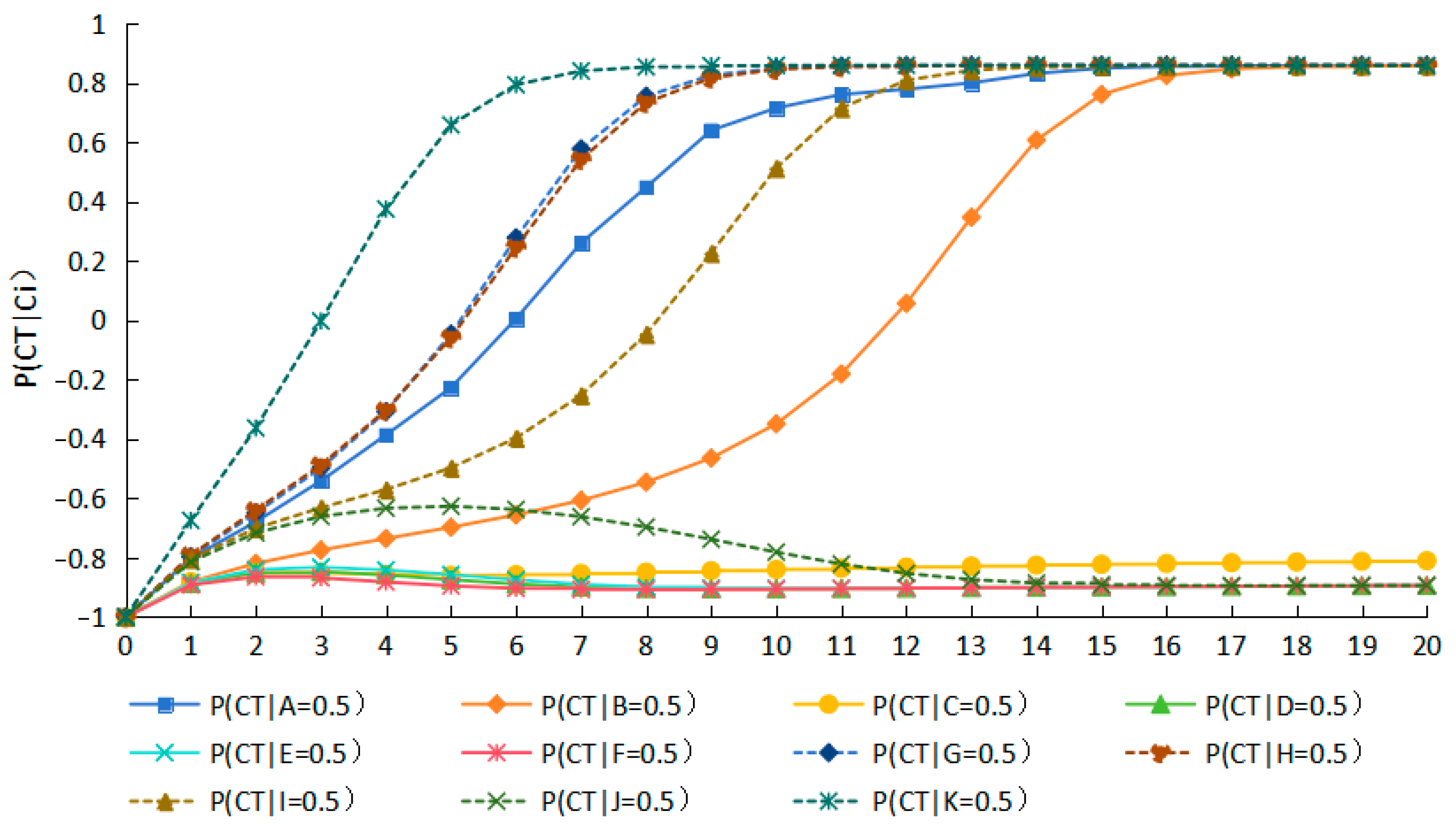

5.3. Hybrid Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Static Structural Relationships

6.2. Dynamic Evolutionary Relationships

6.3. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wan, J.; Wang, Q.; Miao, S. The Impact of Urbanization on Industrial Transformation and Upgrading: Evidence from Early 20th Century China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating the Value Relationships of Stakeholders in Urban Land Redevelopment: A Study Based on Stakeholder Value Network and Adversarial Interpretive Structure Modeling. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, K.; Ji, X.; Xu, H.; Xiao, Y. Assessment and Spatial-Temporal Evolution Analysis of Urban Land Use Efficiency under Green Development Orientation: Case of the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomerations. Land 2021, 10, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Jin, X.; Wang, J.; Yin, Y.; Liu, C.; Sun, R.; Zhou, Y. Identifying Inefficient Urban Land Redevelopment Potential for Evidence-Based Decision Making in China. Habitat Int. 2022, 128, 102661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Deng, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, X. Mechanism and Simulation of Intensive Use of Urban Inefficient Land Based on Evolutionary Game Theory. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 95, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Barham, B.L.; Coxhead, I. Measuring Soil Quality Dynamics a Role for Economists, and Implications for Economic Analysis. Agric. Econ. 2000, 25, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.N. The Triple Structure Theory of the Driving Force of Thing Development and Its Implications. Peoples Trib. 2013, 14, 194–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yuan, J.; Xia, N.; Bouferguene, A.; Al-Hussein, M. Improving Information Sharing in Major Construction Projects through OC and POC: RDT Perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, K.; Guo, P. Construction Safety Risks of Metro Tunnels Constructed by the Mining Method in Wuhan City, China: A Structural Equation Model-Fuzzy Cognitive Map Hybrid Method. Buildings 2023, 13, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroso, N.H.; Zevenbergen, J.A. Urban Land Management under Rapid Urbanization: Exploring the Link between Urban Land Policies and Urban Land Use Efficiency in Ethiopia. Cities 2024, 153, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, S.; You, H.; Wang, C. Governments’ Behavioral Strategies in Cross-Regional Reduction of Inefficient Industrial Land: Learned from a Tripartite Evolutionary Game Model. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Liang, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Shi, Q.; Wang, G. An Optimization Model for Managing Stakeholder Conflicts in Urban Redevelopment Projects in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, X. Different Pathways, Same Goal: Configuring Different Types of Policy Tools to Improve the Urban Land Green Use Efficiency. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-H.; Zhu, Y.-M.; He, L.; Song, H.-J.; Mu, B.-X.; Lyu, F. Recognizing and Managing Construction Land Reduction Barriers for Sustainable Land Use in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 14074–14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, H.; Ji, J. The Local Government Fiscal Pressure’s Effect on Green Total Factor Productivity: Exploring Mechanisms from the Perspective of Government Behavior. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2024, 96, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Choy, L.H.T. How Transaction Costs Affect Real Estate Developers Entering into the Building Energy Efficiency (BEE) Market? Habitat Int. 2013, 37, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. Garnering Sympathy: Moral Appeals and Land Bargaining under Autocracy. J. Institutional Econ. 2022, 18, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wu, M.; Qu, J.; Fan, Y. How to Motivate Planners to Participate in Community Micro-Renewal: An Evolutionary Game Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 943958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Dallimer, M.; Stringer, L.C.; Bai, Z.; Siu, Y.L. Land Expropriation Compensation among Multiple Stakeholders in a Mining Area: Explaining “Skeleton House” Compensation. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanlan, L.; Yuting, Q.; Jingjing, L.; Ranran, Y. Modeling of Residents’ Participation Behavior in China’s Community Green Renewal Projects through Integration of Social Networks and Multi-Agent Simulation. Cities 2025, 162, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Ren, F.; Wang, Y. Study on the Relationship Between Ecological Transformation of Urban Infrastructure and Urban Resilience-Based on Complex System Perspective. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 16, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G. The Network Governance of Urban Renewal: A Comparative Analysis of Two Cities in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Kuang, C.; Li, W. Spatial correlation network and impacts of urban renewal and ecological resilience in urban agglomerations in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2024, 44, 1936–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G. An Analysis of Urban Renewal Decision-Making in China from the Perspective of Transaction Costs Theory: The Case of Chongqing. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 1177–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bao, X.; Ge, Z.; Xi, J.; Zhao, Y. Identification and Redevelopment of Inefficient Residential Land use in Urban Areas: A Case Study of Ring Expressway Area in Harbin City of China. Land 2024, 13, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chau, K.W.; Zhang, M.; Yang, L. Institutional Innovations from State-Dominated to Market-Oriented: Price Premium Differentials of Urban Redevelopment Projects in Shenzhen, China. Cities 2022, 131, 103993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhou, W.; Guan, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, B.; Lei, F.; Yang, H.; Huo, W. Evolution of Policy Concerning the Readjustment of Inefficient Urban Land Use in China Based on a Content Analysis Method. Sustainability 2020, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Chi, G.; Wang, H. Scenario Analysis of Carbon Emission Changes Resulting from a Rural Residential Land Decrement Strategy: A Case Study in China. Land 2024, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Li, Q.; Guo, H.; Li, H. Quantifying the Core Driving Force for the Sustainable Redevelopment of Industrial Heritage: Implications for Urban Renewal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 48097–48111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Needs Hierarchy for Public Service Facilities and Guidance-Control Programming in Small Chinese Towns Influenced by Complex Urbanization of Residents: The Evidence from Zhejiang. Land 2023, 12, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Ren, S.; Liu, Y. The Driving Factors of Green Technology Innovation Efficiency—A Study Based on the Dynamic QCA Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Cao, X. Spatiotemporal Differentiation of Ecological Resilience under Urban Renewal and Its Influencing Mechanisms Around the Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan Urban Agglomeration. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Liu, W.; Chen, J. Land use evolution in waterfront urban renewal: A case study of Xiaguan, Nanjing. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 3225–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Han, D.; Yi, C. Comparison and mechanism optimization of urban renewal governance models from the perspective of social network. Urban Dev. Stud. 2022, 29, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, H. Research Progress and Prospects on Driving Mechanisms and Influence Effects of Urban Renewal. J. Nat. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 2025, 48, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Várady, G.; Zagorácz, M.B. Sustainable Application of Automatically Generated Multi-Agent System Model in Urban Renewal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiqi, Z. Dynamic Coupling and Interaction Mechanisms between Digital Infrastructure and Urban Sustainable Renewal: A Case Study of Jiangsu Province. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Hong, X.; Sun, Y. Research on the Multi-scale Spatial Deconstruction of Urban Resilience Evaluation Indicators from a Multidimensional Perspective. J. Eng. Manag. 2025, 39, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Wei, L.; Ye, Y. Simulation and Prediction of Land Use Structure in Context of Transformation of Resource-based Cities. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 44, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Yu, M.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X.; Hou, J. Evolutionary Analysis of Value Co-Destruction in Urban Village Renovation Using SEM-FCM Model. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 7486–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X.Z. Research on the mechanism of collaborative governance of old neighborhood renovation based on fuzzy cognitive map. Chongqing Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahim, S.; Mir, B.A.; Suhara, H.; Mohamed, F.A.; Sato, M. Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Social Media Use and Education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, X.; Bian, Z.; Wang, Y. Interaction Mechanism between Inter-Organizational Relationship Cognition and Engineering Project Value Added from the Perspective of Dynamic Impact. Systems 2024, 12, 362–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, Q. Research on the Impact Path of the Resilience of Prefabricated Building Supply Chain on Construction Cost. Constr. Econ. 2024, 45, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, X.; Zhang, N.; Lu, Y. Using Fuzzy Cognitive Maps to Explore the Dynamic Impact on Management Team Resilience in International Construction Projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 3998–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhang, L.; He, Q. Linking Project Complexity to Project Success: A Hybrid SEM–FCM Method. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 2591–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Wang, M.; Deng, X.; Mao, H.; He, P. What Affects the Corporate Social Responsibility Practices of Chinese International Contractors Considering Dynamic Interactions? A Hybrid Structural Equation Modeling–Fuzzy Cognitive Map Approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 2646–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Sun, B.; Luo, L.; Deng, X. Simulation Analysis of International Reputation Formation Mechanism for High-Speed Railway Enterprises Based on Fuzzy Cognitive Map. J. Syst. Manag. 2024, 33, 536–546. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, W. Policy Synergy for Conflicting Interests in Low-Carbon Innovation: An Evolutionary Game Analysis of Dynamic Incentives and Risk-Sharing in China’s Urban Renewal. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcada, N.; Alvarez, A.P.; Love, P.E.D.; Edwards, D.J. Rework in Urban Renewal Projects in Colombia. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2017, 23, 04016034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Correction to: Reporting Reliability, Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Structural Equation Modeling: A Review and Best-Practice Recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2024, 41, 785–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M.; De Rosa, S.P. Use of Fuzzy Cognitive Maps to Develop Policy Strategies for the Optimization of Municipal Waste Management: A Case Study of the Land of Fires (Italy). Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.Z.; Chen, H.Y.; Xu, W. Evaluation of Urban Large-scale Infrastructure Sustainability Based on Dynamic Fuzzy Cognitive Map. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2023, 40, 111–117+153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, G.; Nápoles, G.; Falcon, R.; Froelich, W.; Vanhoof, K.; Bello, R. A Review on Methods and Software for Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 52, 1707–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chettupuzha, A.J.A.; Chen, H.; Wu, X.; AbouRizk, S.M. Fuzzy Cognitive Maps Enabled Root Cause Analysis in Complex Projects. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 57, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.X. Research on the Driving Mechanism of Green Renovation of Existing Public Buildings in Towns and Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Zhang, Q.G.; Wang, X. Spillover Effect and Solutions of High Level Sports Team University Enrollment Policy under New Productive Forces. J. Wuhan Inst. Phys. Educ. 2024, 58, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Deng, Y.; Song, C. Exploring the Drivers of Urban Renewal through Comparative Modeling of Multiple Types in Shenzhen, China. Cities 2023, 137, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, J. Low-Carbon Strategy Analysis in a Construction Supply Chain Considering Government Subsidies and Contract Design. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaloupková, M.; Kunc, J.; Koutský, J. Creative Economy: Support of Creative Hubs by the Public Sector in the Urban Environment. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2023, 29, 1611–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gächter, S.; Kölle, F.; Quercia, S.; Thoni, C. A CRISP Framework of Rule Compliance: An Interdisciplinary Review. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønneberg, S.; Irmer, J.P. Non-Parametric Regression among Factor Scores: Motivation and Diagnostics for Nonlinear Structural Equation Models. Psychometrika 2024, 89, 822–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Driving Factor | Category | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Economic incentives | Drivers | The pursuit of higher economic returns by market entities constitutes the fundamental driving force. |

| 2 | Environmental objectives | Pressure | Environmental constraints and sustainability objectives generate compelling pressure for redevelopment. |

| 3 | Social needs | Pressure | Public demands for improved living conditions and urban quality generate sustained social pressure. |

| 4 | Policy guidance | Enablers | Government policies and regulations provide directional guidance and institutional support. |

| 5 | Implementation conditions | Enablers | Financial resources, technical expertise, and property rights integration serve as essential enabling conditions. |

| Variable | Measurement Items | Reference Source |

|---|---|---|

| Economic incentives (ECO) | Expected GDP growth rate (ECO1) | [39] |

| Forecasted growth in property values (ECO2) | [4] | |

| Industrial upgrading and restructuring (ECO3) | [3] | |

| Expected local tax revenue increase (ECO4) | [20] | |

| Environmental objectives (ENV) | Land resource Shortage (ENV1) | [36] |

| Environmental pollution and ecological stress (ENV2) | [38] | |

| Infrastructure carrying capacity pressure (ENV3) | [34] | |

| Social needs (SOC) | Demand for improved living environment (SOC1) | [25] |

| Need for enhanced public service facilities (SOC2) | [5] | |

| Public support and engagement (SOC3) | [58] | |

| Policy guidance (POL) | Level of support from higher-level policies (POL1) | [42] |

| Compliance with urban planning (POL2) | [4] | |

| Guidance from specialized plans (POL3) | [29] | |

| Efficiency of administrative approval (POL4) | [59] | |

| Implementation conditions (IMP) | Adequacy of funding (IMP1) | [8] |

| Technical and plan feasibility (IMP2) | [31] | |

| Effectiveness of stakeholder coordination mechanisms (IMP3) | [22] | |

| Redevelopment performance (RED) | Improvement in intensive land use level (RED1) | [21] |

| Level of regional economic value-added (RED2) | [11] | |

| Overall satisfaction of surrounding residents (RED3) | [32] |

| Variable Type | Items | Options | Valid N | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic information | Type of employer | Government department | 14 | 6.30% |

| Academia/Research institute | 55 | 24.80% | ||

| Development company | 60 | 27.00% | ||

| Community organization | 48 | 21.60% | ||

| Other | 45 | 20.30% | ||

| Years of experience | 1–3 years | 40 | 18.00% | |

| 3–5 years | 99 | 44.60% | ||

| 5–10 years | 56 | 25.20% | ||

| Over 10 years | 27 | 12.20% | ||

| Professional relevance | Familiar with related work? | Very familiar | 56 | 25.20% |

| Fairly familiar | 64 | 28.80% | ||

| Moderately familiar | 74 | 33.30% | ||

| Not very familiar | 28 | 12.60% | ||

| Involved in related projects? | Yes | 168 | 75.70% | |

| No | 54 | 24.30% | ||

| Total | 222 | 100% | ||

| Factor | Variable | Factor Loading | Mean | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic incentives | C11 | 0.806 | 3.43 | 0.889 | 0.666 | 0.888 |

| C12 | 0.817 | 3.42 | ||||

| C13 | 0.787 | 3.35 | ||||

| C14 | 0.854 | 3.30 | ||||

| Environmental objectives | C21 | 0.777 | 3.39 | 0.856 | 0.664 | 0.854 |

| C22 | 0.816 | 3.36 | ||||

| C23 | 0.850 | 3.41 | ||||

| Social needs | C31 | 0.807 | 3.54 | 0.862 | 0.676 | 0.862 |

| C32 | 0.829 | 3.62 | ||||

| C33 | 0.830 | 3.66 | ||||

| Policy guidance | C41 | 0.820 | 3.57 | 0.871 | 0.629 | 0.871 |

| C42 | 0.763 | 3.62 | ||||

| C43 | 0.784 | 3.61 | ||||

| C44 | 0.804 | 3.73 | ||||

| Implementation conditions | C51 | 0.888 | 3.58 | 0.887 | 0.723 | 0.886 |

| C52 | 0.822 | 3.51 | ||||

| C53 | 0.840 | 3.49 | ||||

| Redevelopment performance | CT1 | 0.852 | 3.35 | 0.879 | 0.707 | 0.878 |

| CT2 | 0.825 | 3.41 | ||||

| CT3 | 0.846 | 3.38 |

| Variable | Economic Incentives | Environmental Objectives | Social Needs | Policy Guidance | Implementation Conditions | Redevelopment Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic incentives | 0.816 | |||||

| Environmental objectives | 0.166 | 0.815 | ||||

| Social needs | 0.247 | 0.211 | 0.822 | |||

| Policy guidance | 0.285 | 0.224 | 0.405 | 0.793 | ||

| Implementation conditions | 0.376 | 0.354 | 0.302 | 0.372 | 0.850 | |

| Redevelopment performance | 0.442 | 0.367 | 0.403 | 0.459 | 0.481 | 0.841 |

| N | Hypothesis | β | S.E. | C.R. | P | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Economic incentives→ Redevelopment performance | 0.196 | 0.079 | 2.332 | *** | support |

| H2 | Environmental objectives→ Redevelopment performance | 0.180 | 0.084 | 2.262 | ** | support |

| H3 | Social needs→ Redevelopment performance | 0.199 | 0.073 | 2.694 | *** | support |

| H4 | Policy guidance→ Redevelopment performance | 0.213 | 0.085 | 2.600 | ** | support |

| H5 | Implementation conditions→ Redevelopment performance | 0.171 | 0.072 | 2.297 | ** | support |

| H6 | Policy guidance→ Economic incentives | 0.283 | 0.087 | 3.607 | 0.015 | support |

| H7 | Policy guidance→ Implementation conditions | 0.297 | 0.078 | 4.082 | *** | support |

| H8 | Environmental objectives→ Implementation conditions | 0.234 | 0.091 | 2.805 | *** | support |

| H10 | Economic incentives→ Implementation conditions | 0.205 | 0.092 | 2.301 | *** | support |

| Index | Variable Name | Index | Variable Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Economic incentives | C4 | Policy guidance |

| C2 | Environmental objectives | C5 | Implementation conditions |

| C3 | Social needs | CT | Redevelopment performance |

| P (CT|Ci = 1) | P (CT|Ci = 0.5) | P (CT|Ci = −1) | P (CT|Ci = −0.5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.9064 | 0.8164 | −0.9064 | −0.8164 |

| C2 | 0.8302 | 0.7108 | −0.8302 | −0.7108 |

| C3 | 0.7038 | 0.5854 | −0.7038 | −0.5854 |

| C4 | 0.8803 | 0.8564 | −0.8803 | −0.8564 |

| C5 | 0.7938 | 0.7055 | −0.7938 | −0.7055 |

| N | P (Ci|CT = 1.0) | P (Ci|CT = 0.5) | P (Ci|CT = −1.0) | P (Ci|CT = −0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.9056 | 0.8734 | −0.9056 | −0.8374 |

| C2 | 0.8370 | 0.7845 | −0.8370 | −0.7845 |

| C3 | 0.7302 | 0.6108 | −0.7302 | −0.6108 |

| C4 | 0.9280 | 0.9030 | −0.9280 | −0.9030 |

| C5 | 0.8093 | 0.7495 | −0.8093 | −0.7495 |

| Integrated Intervention Scenarios | C1 | C2 | C4 | C5 | CT | Effect Sorting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated intervention scenarios 1 | 0.5 | −1 | 0.5 | −1 | 0.8590 | 4 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 2 | −1 | −1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8580 | 6 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 3 | −1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | −1 | −0.8104 | 7 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 4 | 0.5 | −1 | −1 | 0.5 | −0.8936 | 9 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | −1 | −1 | −0.8936 | 9 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 6 | −1 | 0.5 | −1 | 0.5 | −0.8936 | 9 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 7 | 0.5 | −1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8591 | 2 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | −1 | 0.8591 | 2 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 9 | −1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8583 | 5 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 10 | 0.5 | 0.5 | −1 | 0.5 | −0.8934 | 8 |

| Integrated intervention scenarios 11 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8591 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H. Modeling the Multiple Driving Mechanisms and Dynamic Evolution of Urban Inefficient Land Redevelopment: An Integrated SEM-FCM Approach. Land 2025, 14, 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122411

Yang S, Zhang Y, Zhang P, Chen H. Modeling the Multiple Driving Mechanisms and Dynamic Evolution of Urban Inefficient Land Redevelopment: An Integrated SEM-FCM Approach. Land. 2025; 14(12):2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122411

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Siling, Yang Zhang, Puwei Zhang, and Hao Chen. 2025. "Modeling the Multiple Driving Mechanisms and Dynamic Evolution of Urban Inefficient Land Redevelopment: An Integrated SEM-FCM Approach" Land 14, no. 12: 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122411

APA StyleYang, S., Zhang, Y., Zhang, P., & Chen, H. (2025). Modeling the Multiple Driving Mechanisms and Dynamic Evolution of Urban Inefficient Land Redevelopment: An Integrated SEM-FCM Approach. Land, 14(12), 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122411