Official Projection vs. Public Perception: Measuring the Perceptual Discrepancy of Creative Industry Parks in the Industrial Heritage Category Using Large Language Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What perceptual dimensions do official projections and public perceptions focus on in industrial heritage creative industry parks, and which of these dimensions exist significant discrepancies between the two?

- What is the public’s overall emotional tendency towards these creative industry parks, and what are the key factors driving these emotions?

- How can large language models and multimodal data be leveraged to construct an effective framework for quantifying perceptual discrepancy?

2. Methods

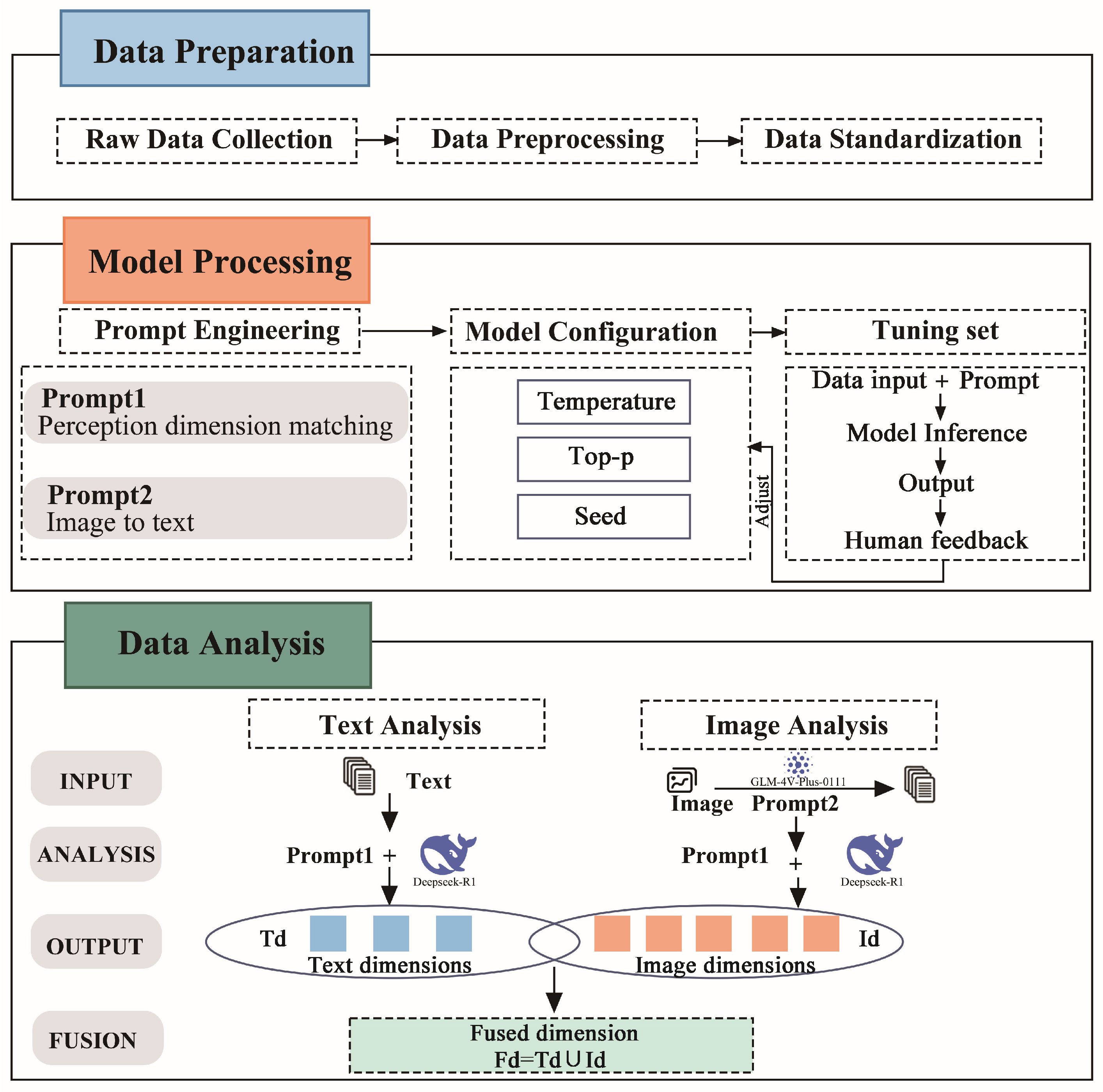

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Study Area

- Exemplary in the transformation of industrial heritage into creative industry parks, serving as models of successful adaptation.

- The transformed parks exhibit a functional integration of cultural, artistic, commercial, and innovative activities.

- The parks encompass various types of industrial heritage and geographic distributions, reflecting the diversity of the research subjects in both type and regional characteristics.

- The parks offer sufficient data to support a comprehensive analysis.

2.3. Perceptual Dimension System

2.4. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.4.1. Data Collection

2.4.2. Data Preprocessing

2.5. Large Language Models and Prompt Engineering

2.6. Analysis Methodology

2.6.1. Text Analysis

2.6.2. Sentiment Analysis

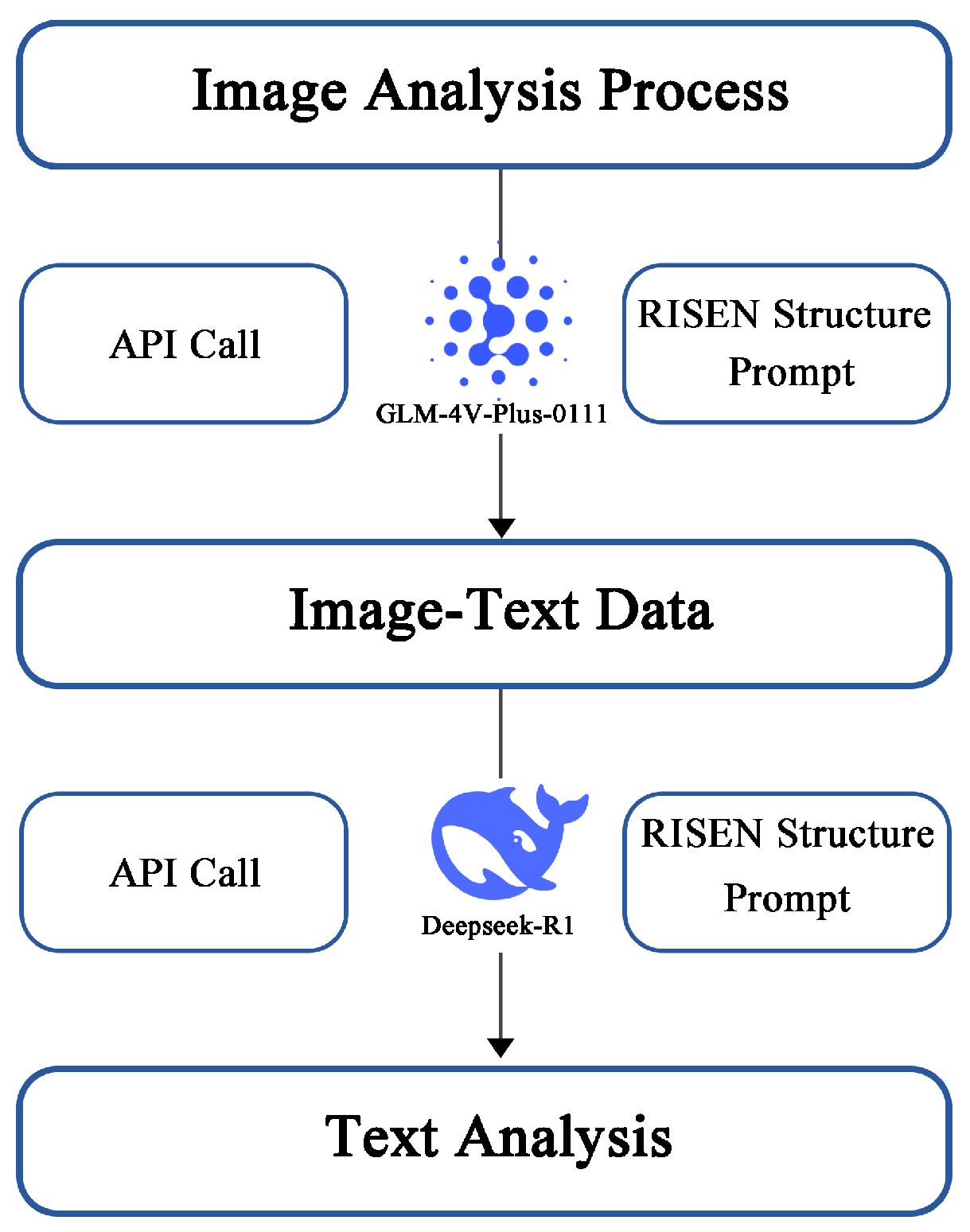

2.6.3. Image Analysis

2.6.4. Validation

2.7. Multimodal Data Fusion and Discrepancy Quantification

2.7.1. Multimodal Data Fusion

2.7.2. Frequency Distribution and Chi-Square Test

3. Results

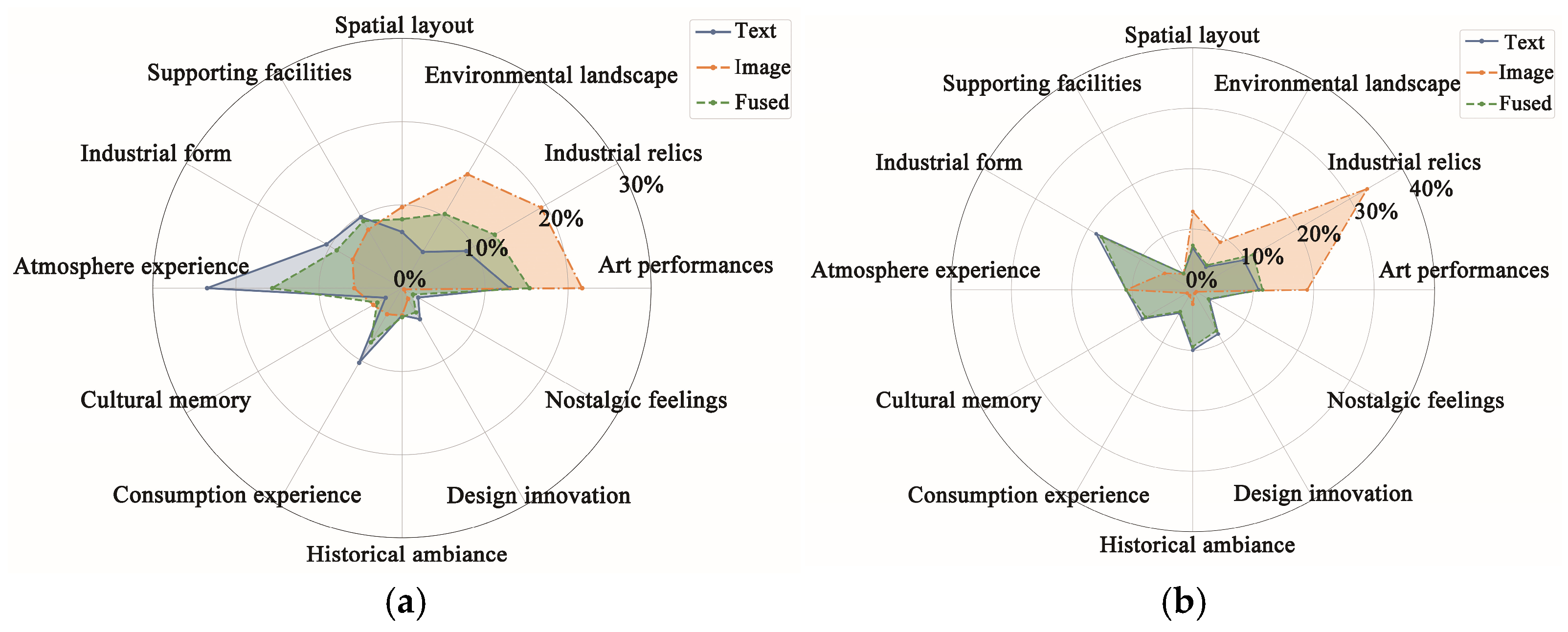

3.1. Multimodal Data Fusion Results

3.1.1. Statistical Results of Public Perceptions

3.1.2. Statistical Results of Official Projections

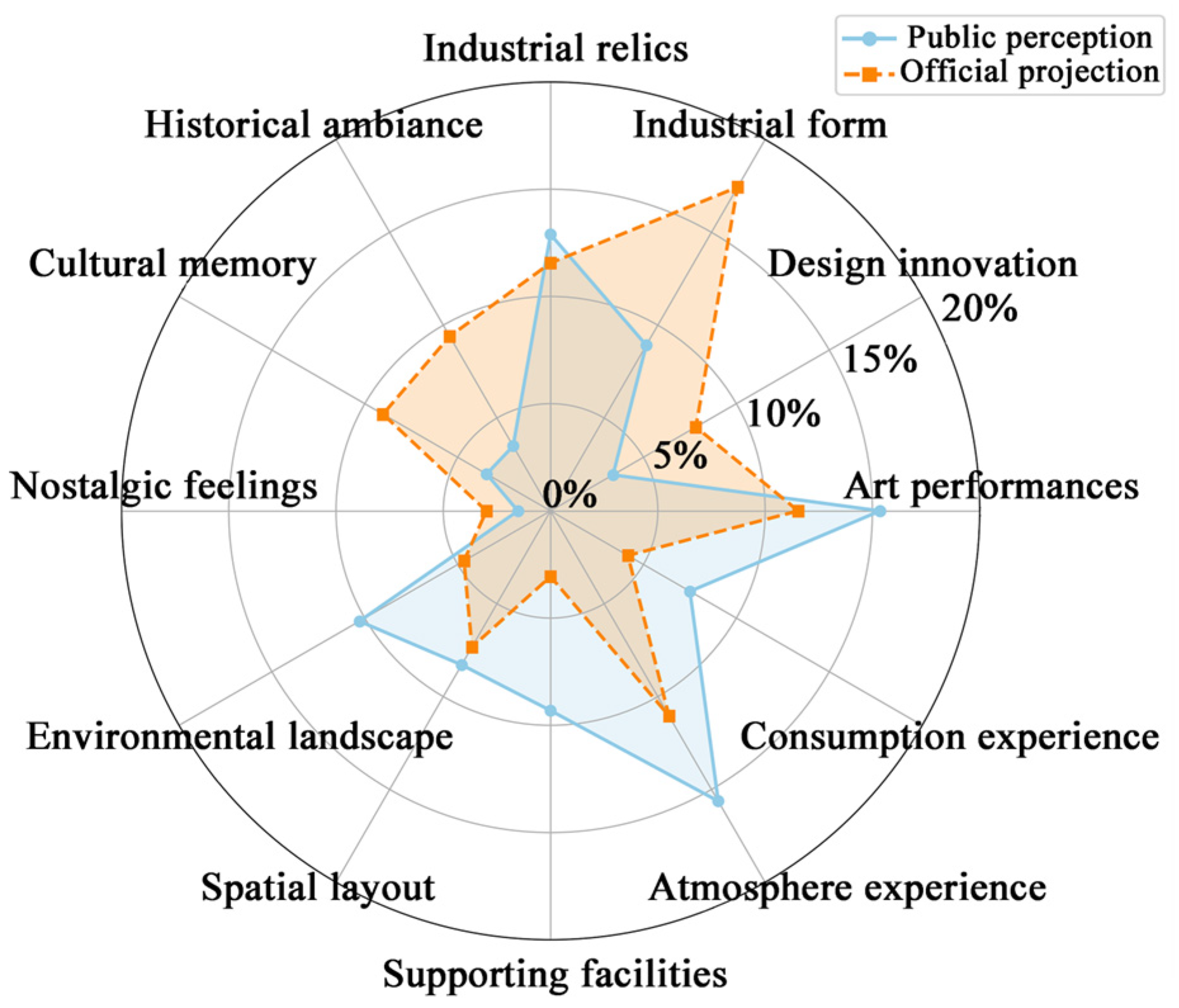

3.2. Quantification and Validation of Discrepancies Between Official Projections and Public Perception

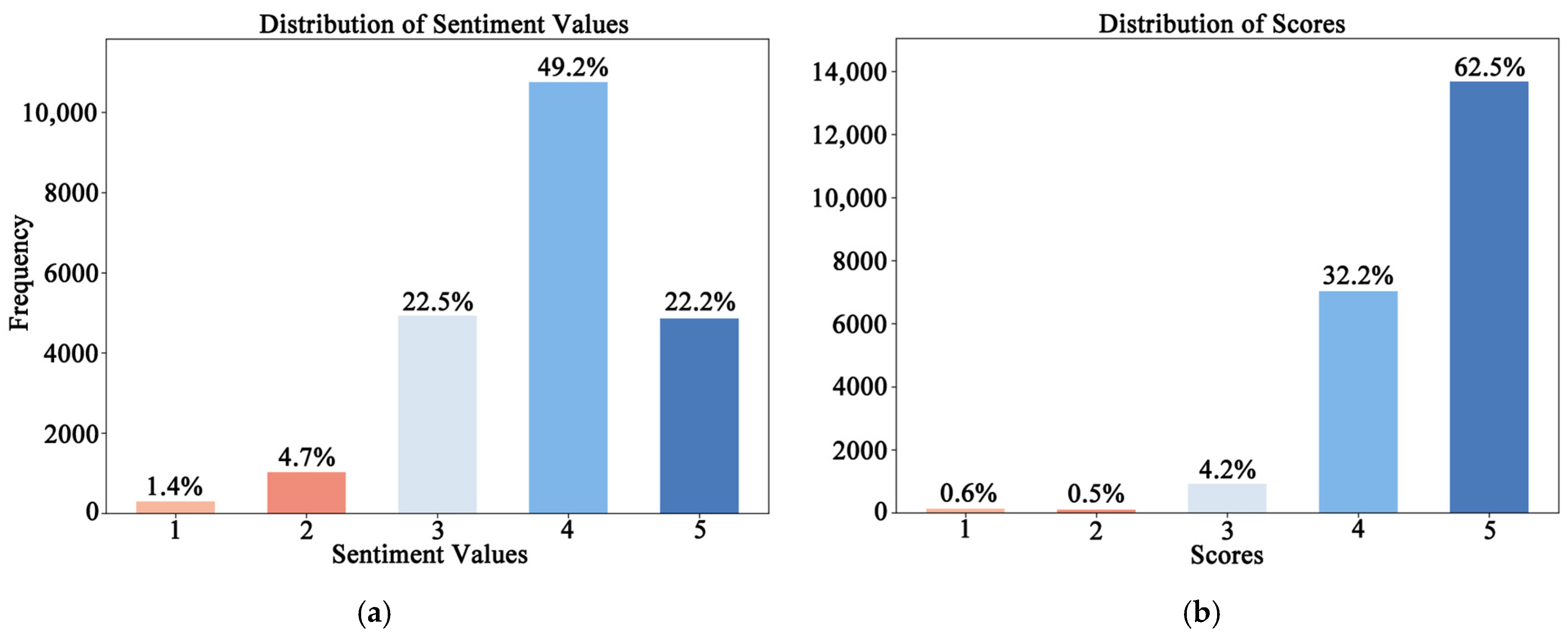

3.3. Distribution of Sentiment

4. Discussion

4.1. Mapping and Quantification of Perceptual Dimensions

4.2. Discrepancies Between Official Projections and Public Perceptions

4.3. Implications for Operational Management and Planning

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Discrepancies exist between official projections and public perceptions across dimensions. Official narratives adopt a macro perspective, emphasizing the park’s historical and cultural value, and functional layout. Consequently, this places greater emphasis on promoting dimensions such as HA, CM, and IF. However, constrained by the spatial presentation of heritage elements, the public’s overall perception of this dimension remains relatively weak. Therefore, subsequent planning should enhance the visual representation and scenarization of heritage elements to bridge this cognitive gap. As primary users of the space, the public prioritizes sensory experiences and functional services. Consequently, their perception intensity regarding dimensions such as supporting facilities and consumption experience within the Service experience perception is significantly higher than that of official projections. This disparity reflects the differing positions and needs between the two parties. Furthermore, both official projections and public perceptions exhibit a high proportion of attention to the Creative industry form dimension, highlighting the need to sustain and further enhance this dimension in future park operations.

- (2)

- The public’s overall sentiment toward the park is predominantly positive, with particularly high satisfaction levels associated with the DI, CM, and NF dimensions, which serve as key factors driving positive sentiment. Negative sentiments are primarily concentrated in the SF and CE dimensions, where issues such as inadequate supporting facilities, poor consumer experience, and limited spatial accessibility significantly impact public satisfaction.

- (3)

- This study develops an analytical framework utilizing LLMs and multimodal data to quantify perceptual discrepancies. By employing structured prompts and LLM APIs, this approach facilitates the systematic analysis of both textual and image data. The integrated data provides a more holistic representation of the park’s perceptual image, significantly enhancing model interpretability. Furthermore, it also provides a reusable analytical pipeline for similar multimodal research.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UGC | User-generated content |

| LLMs | Large language models |

| MLLMs | Multimodal Large Language Models |

References

- Soares, Z.M.; Marques, J.; Sousa, C. Regional development through industrial tourism: A literature review. RPER 2024, 68, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.; Zuo, Y. “Intangible cultural heritage” label in destination marketing toolkits: Does it work and how? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, Y. Research on tourism development of cultural and creative industry park based on the network text analysis: A case study of dafen oil painting village in Shenzhen. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Information Management (ICIM), Chengdu, China, 21–23 April 2017; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Zhang, H. Progress and prospects in industrial heritage reconstruction and reuse research during the past five years: Review and outlook. Land 2022, 11, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Qi, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, L.; Wan, D.; Burak-Gajewski, P.; Zawisza, R.; Liu, L. External spatial morphology of creative industries parks in the industrial heritage category based on spatial syntax: Taking Tianjin as an example. Buildings 2024, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, Z.; Marques, J.; Sousa, C. Industrial tourism as a factor of sustainability and competitiveness in operating industrial companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F.; Ramos, R.A.R. Vacant industrial buildings in Portugal: A case study from four municipalities. Plan. Pract. Res. 2019, 34, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Kwilinski, A.; Krawczyk, D. Post-industrial tourism as a driver of sustainable development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, W.R. Mining for tourists: An analysis of industrial tourism and government policy in Wales. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 18, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćopić, S.; Đorđević, J.; Lukić, T.; Stojanović, V.; Đukičin, S.; Besermenji, S.; Stamenković, L.; Tumarić, A. Transformation of industrial heritage: An example of tourism industry development in the Ruhr area (Germany). Geogr. Pannonica 2014, 18, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Guo, P. Regeneration path of abandoned industrial buildings: The moderating role of the goodness of regeneration mode. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardopoulos, I. Critical sustainable development factors in the adaptive reuse of urban industrial buildings. A fuzzy DEMATEL approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfst, J.; Sandriester, J.; Fischer, W. Industrial heritage tourism as a driver of sustainable development? A case study of Steirische Eisenstrasse (Austria). Sustainability 2021, 13, 3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, P.; Wang, L. A study of the affective motives of city industrial heritage tourists: A case study from Tianjin, China. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2023, 21, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Kerstetter, D.L.; Graefe, A.R. Tourists’ reasons for visiting industrial heritage sites. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2001, 8, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Liu, M.; Wang, R. Reproducing the discourse on industrial heritage in China: Reflections on the evolution of values, policies and practices. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, J.; Skowron, B.M. Visitor Characteristics, Activities and Satisfaction at Two Industrial Tourism Sites in the Ruhr Area: A Quantitative Descriptive Study. Proc. Int. Conf. New Find. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2025, 2, 20–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Jin, C.; Zhou, L.; Gu, Y.; Gai, Z.; Liu, R.; Qiu, B. Using social media text data to analyze the characteristics and influencing factors of daily urban green space usage—A case study of Xiamen, China. Forests 2023, 14, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagni, F.; Batallé, J.N.; Baró, F.; Langemeyer, J. A tag is worth a thousand pictures: A framework for an empirically grounded typology of relational values through social media. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 58, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R.C.; Witt, S.F.; Hamer, C. Tourism as experience: The case of heritage parks. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, J.; Dou, Q.; Fu, F.; Shi, Y. Digital footprint as a public participatory tool: Identifying and assessing industrial heritage landscape through user-generated content on social media. Land 2024, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N.; Hung, K.P. Examining tourists’ loyalty toward cultural quarters. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 51, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Banerji, H. Disparities in expert and community perceptions of industrial heritage and implications for urban well-being in West Bengal, India. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosspietsch, M. Perceived and projected images of Rwanda: Visitor and international tour operator perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Chung, W. The impact of park environmental characteristics and visitor perceptions on visitor emotions from a cross-cultural perspective. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 102, 128575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Rawding, L. Tourism marketing images of industrial cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Deng, N.; Li, X.; Gu, H. How to “Read” a Destination from Images? Machine Learning and Network Methods for DMOs’ Image Projection and Photo Evaluation. J. Travel Res. 2021, 61, 597–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Udomwong, P.; Fu, J.; Onpium, P. Destination image: A review from 2012 to 2023. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2240569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.N. Online destination image: Comparing national tourism organisation’s and tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Xiang, G.; Dong, Y. Network mechanism contrast: A new perspective of the ‘projection-perception’ contrast of the destination image. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 1482–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B. Measuring the gap between projected and perceived destination images of Catalonia using compositional analysis. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Huang, J.; Shen, H.; Li, X.; Law, A. Evaluating tourist perceptions of architectural heritage values at a World Heritage Site in South-East China: The case of Gulangyu Island. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegara-Ferri, J.M.; Ibáñez-Ortega, D.; Carboneros, M.; López-Gullón, J.M.; Angosto, S. Evaluation of the tourist perception of the spectator in an eSport event. Publicaciones 2020, 50, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassia, F.; Vigolo, V.; Ugolini, M.M.; Baratta, R. Exploring city image: Residents’ versus tourists’ perceptions. TQM J. 2018, 30, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.P.; Ayob, N.; Puah, C.H.; Arip, M.A.; Jong, M.C. Destination image perception mediated by experience quality: The case of Qingzhou as an emerging destination in China. Electronics 2023, 12, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Han, W.; Liu, S. Urban Tourism Destination Image Perception Based on LDA Integrating Social Network and Emotion Analysis: The Example of Wuhan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Tao, Z.; Hou, M.; Chen, D.; Wang, L. A comparative study of perceptions of destination image based on content mining: Fengjing Ancient Town and Zhaojialou Ancient Town as examples. Land 2023, 12, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Zhao, E.; Wang, S. How do tourists perceive churches as tourism destinations? A text mining approach through online reviews. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Marafa, L.M.; Chan, C.S.; Xu, H.; Cheung, L.T. Measuring the gaps in the projected image and perceived image of rural tourism destinations in China’s Yangtze River Delta. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, S.; Liu, R.; Jiang, Q. Exploring the discrepancy between projected and perceived destination images: A cross-cultural and sustainable analysis using LDA modeling. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Elhoushy, S.; Kuhzady, S.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Zaman, M. Bridging the Green Marketing Communication Gap: Assessing Image Coherence in Green Hotels. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Zhan, F. Visual destination images of Peru: Comparative content analysis of DMO and user-generated photography. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Jo, H.I.; Lee, K. Potential restorative effects of urban soundscapes: Personality traits, temperament, and perceptions of VR urban environments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Han, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zeng, X.; Liao, H. Do the DMO and the tourists deliver the similar image? Research on representation of the health destination image based on UGC and the theory of discourse power: A case study of Bama, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, T.; Liu, Z. Keep it real: Assessing destination image congruence and its impact on tourist experience evaluations. Tour. Manag. 2023, 97, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, J.; Cao, S.; Gao, M. Popularity influence mechanism of coastal spaces in urban areas: Insights from multi-modal large language models. Cities 2025, 161, 105909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Su, Y. Perception study of urban green spaces in Singapore urban parks: Spatio-temporal evaluation and the relationship with land cover. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 99, 128455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chang, J.; An, X.; Li, S. Global and local feature extraction of urban historical spatial perception using large language models: A case study of Harbin Central Street District. Cities 2025, 165, 106183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Ameur, N.E.H.B.; Liu, X.; Ding, F.; Cai, Y. Using large language models to investigate cultural ecosystem services perceptions: A few-shot and prompt method. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 258, 105323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, X.; Wang, X.; Fan, W. Public Perception of Urban Recreational Spaces Based on Large Vision–Language Models: A Case Study of Beijing’s Third Ring Area. Land 2025, 14, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Huang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zheng, A. Quantifying tourist perception of cultural landscapes in traditional towns in China using multimodal machine learning. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Geng, J. Research on the perception of the terrain image of the tourism destination based on multimodal user-generated content data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yang, Y. A multi-modal social media data analysis framework: Exploring the complex relationships among urban environment, public activity, and public perception—A case study of Xi’an, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, S.; Yu, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, M. How to bridge the gap between modalities: Survey on multimodal large language model. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 5311–5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yu, L.; Fang, H.; Wu, J. Research on the protection and reuse of industrial heritage from the perspective of public participation—A case study of northern mining area of Pingdingshan, China. Land 2021, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS; TICCIH. Joint ICOMOS-TICCIH Principles for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage Sites, Structures, Areas and Landscapes. Available online: https://ticcih.org/about/about-ticcih/dublin-principles/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Bing, Z.; Tang, S.; Wang, R. Exploring the Spatial Differentiation of Urban Tourism Image Based on Geotagged Photos: Taking Five World Famous Tourist Cities as Examples. World Reg. Stud. 2022, 31, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, P. Popularity influence mechanism of creative industry parks: A semantic analysis based on social media data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 90, 104384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, B.; Chen, Z.; Ma, D.; Sun, C.; Wang, M.; Jiang, X. Landscape Perception in Cultural and Creative Industrial Parks: Integrating User-Generated Content (UGC) and Electrodermal Activity Insights. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yang, S. Coupling Relationship Between Tourists’ Space Perception and Tourism Image in Nanxun Ancient Town Based on Social Media Data Visualization. Buildings 2025, 15, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiaan, M.A.K.; Mukta, M.S.H.; Fatema, K.; Fahad, N.M.; Sakib, S.; Mim, M.M.J.; Ahmad, J.; Ali, M.E.; Azam, S. A review on large language models: Architectures, applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26839–26874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Fu, Q.; Hays, S.; Sandborn, M.; Olea, C.; Gilbert, H.; Schmidt, D.C. A prompt pattern catalog to enhance prompt engineering with chatgpt. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.11382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Lyu, X.; Holtzman, A.; Artetxe, M.; Lewis, M.; Hajishirzi, H.; Zettlemoyer, L. Rethinking the Role of Demonstrations: What Makes In-Context Learning Work? In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 11048–11064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bsharat, S.M.; Myrzakhan, A.; Shen, Z. Principled instructions are all you need for questioning llama-1/2, gpt-3.5/4. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.16171. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Kuchiba, A.; Koyama, T. Confidence interval for micro-averaged F1 and macro-averaged F1 scores. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 4961–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Cai, C.; Furuya, K. Toward sustainable and differentiated protection of cultural heritage illustrated by a multisensory analysis of Suzhou and Kyoto using deep learning. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, Y. Public emotions and visual perception of the East Coast Park in Singapore: A deep learning method using social media data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 94, 128285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Kirilenko, A.; Yang, J. Capturing differences between culturally dissimilar audiences in the authentication of SMIs who organically promote destinations: The large language model approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2025, 35, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; MacInnis, E.; Yang, C. Understanding the landscape of a modern Chinese city and summer resort from a missionary’s perspective: Text mining ‘Beard Family Papers’ via large language models. Landsc. Res. 2025, 50, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Yang, M.; Wang, J.; Mao, W.; Xu, J.; Ning, H. Tourllm: Enhancing llms with tourism knowledge. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, H.; Yang, T.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, T.; Liu, T. Urban planning in the age of large language models: Assessing OpenAI o1’s performance and capabilities across 556 tasks. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2025, 121, 102332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changyu, C.; Hanting, Y.; Yuhan, G. Perception and Reality: Urban Green Space Analysis Using Language Model-Based Social Media Insights. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference of the Association for Computer Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Singapore, 20–26 April 2024; Volume 2, pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lehto, X.Y. Projected and perceived destination brand personalities: The case of South Korea. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Nik Hashim, N.H.; Goh, H.C. Public perception of cultural ecosystem services in historic districts based on biterm topic model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Chen, M.; Yan, J.; Du, Y.; Su, X. Tourist crowding versus service quality: Impacting mechanism of tourist satisfaction in World Natural Heritage Sites from the Mountain Sanqingshan National Park, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, M. Tracing the Evolution of Tourist Perception of Destination Image: A Multi-Method Analysis of a Cultural Heritage Tourist Site. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z.; Fu, H.; Cheng, J.; Raza, H.; Fang, D. Digital threads of architectural heritage: Navigating tourism destination image through social media reviews and machine learning insights. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fan, W.; You, J. Evaluation of tourism elements in historical and cultural blocks using machine learning: A case study of Taiping Street in Hunan Province. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, S.; Kim, J.M. Analyzing Tourist Online Environmental Discourse With Big Data: A Study of 43 UNESCO Natural World Heritage Sites. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, e70087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Y. An Evaluation Study on Tourists’ Environmental Satisfaction after Re-Use of Industrial Heritage Buildings. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Yao, J.; Shi, J. The influence of environmental factors, perception, and participation on industrial heritage tourism satisfaction—A study based on multiple heritages in Shanghai. Buildings 2024, 14, 3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimic, K.; Polko, P. The use of urban parks by older adults in the context of perceived security. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, M.; Ríos-Rodríguez, M.L.; Suárez, E.; Hernández, B.; Rosales, C. Quality analysis and categorisation of public space. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Chaiyakut, P.; Panthupakorn, P. A Comparative Study of the Transformation of Old Industrial Sites in China into Cultural and Creative Parks. Silpa Bhirasri J. Fine Arts 2025, 13, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.; Cha, H.S. Development of an augmented reality tour guide for a cultural heritage site. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. JOCCH 2019, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Xu, H.; Lei, Z. From phygital experience to virtual travel in cultural heritage destination: The role of tourist inspiration. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Curras-Perez, R.; Ruiz, C.; Andreu, L. I want to travel to the past! The role of creative style and historical reconstructions as antecedents of informativeness in a virtual visit to a heritage tourist destination. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 3369–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Feng, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C. Visual Analysis of Social Media Data on Experiences at a World Heritage Tourist Destination: Historic Centre of Macau. Buildings 2024, 14, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, J. Fairytale authenticity: Historic city tourism, Harry Potter, medievalism and the magical gaze. In Authenticity and Authentication of Heritage; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.; Liu, M.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, S. Effects of creative atmosphere on tourists’ post-experience behaviors in creative tourism: The mediation roles of tourist inspiration and place attachment. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 25, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Park Name | Area (Hectare) | Geographic Location | Brief Introduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dahua 1935 | 8.7 | Shaanxi Province | Dahua 1935, originally Chang’an Dahua Textile Mill, has been transformed into a cultural and commercial complex centered on industrial heritage renovation and adaptive reuse. It integrates urban consumption functions such as fashion, dining, culture, entertainment, and tourism. |

| Taoxichuan Creative Industry Park | 8.9 | Jiangxi Province | Taoxicuan is based on the protection and utilization of ceramic industrial heritage. It offers diverse business forms, including Taoxicuan cultural and art space, social spaces, research study base, and other industry forms. |

| Canal Hub 1958 | 6.2 | Jiangsu Province | Canal Hub 1958, originally a historic steel industrial plant along the Wuxi canal. It integrates diverse scenarios including cultural and creative arts, specialty dining, leisure and social spaces, family-friendly interactions, trendy retail. |

| Eastern Suburb Memory | 20 | Sichuan Province | Eastern Suburb Memory integrates art exhibitions, industrial heritage, graffiti walls, commercial spaces, and more into a multifunctional cultural district. |

| M50 Creative Industry Park | 4.1 | Shanghai | M50 Creative Industrial Park is one of the most iconic examples of industrial heritage revitalization in Shanghai. It has established a diverse ecosystem integrating contemporary art, creative design, and cultural consumption. |

| Dimension | Sub-Dimension | Abbreviation | Explain | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural value of heritage | Industrial relics | IR | Physical remains of industrial civilization | Production facilities, industrial equipment, and factory buildings |

| Historical ambiance | HA | Conveying historical authenticity and temporal accumulation. | History, sense of era, mottled traces | |

| Cultural memory | CM | The intangible cultural values and spiritual values of industrial heritage. | Culture, memory, inheritance, and spirit | |

| Nostalgic feelings | NF | Evoking collective nostalgia through recognizable industrial symbols, fostering emotional connection and identity. | Nostalgia, the past, reminiscence, emotional belonging | |

| Spatial environmental perception | Spatial layout | SL | Industrial architectural and renovation design, reflecting style and layout features. | Style, materials, renovation design, layout, structure |

| Environmental landscape | EL | The integrated landscape system within the creative industry parks site, including lighting, sculptures and greenery. | Environment design, lighting, sculptures, nightscape, greenery | |

| Creative industry form | Art performances | AP | Industrial spaces hosting artistic creation and exhibitions. | Art exhibitions graffiti, theaters, performances |

| Design innovation | DI | Creative clusters that driving the functional transformation and innovation within industrial heritage. | Design studios, innovation hubs, creative incubators | |

| Industrial form | IF | Agglomeration, diversity, operational vitality, and development potential of creative industries. | Industrial clusters, diverse business formats, operational status | |

| Service experience perception | Supporting facilities | SF | Basic services such as catering, transportation, navigation, and convenient facilities | Shops, transportation, parking lots, recreational facilities, navigation, restrooms |

| Atmosphere experience | AE | Social interaction, check-in behavior, and emotional experiences | Internet-famous spaces, photography, check-in, vibrant ambiance | |

| Consumption experience | CE | Perception of the scene, price judgment, price sensitivity, and willingness to pay in cultural consumption | price-performance ratio, cultural and creative, products |

| Framework Part | Public’s Text Analysis | Official’s Text Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Role | Role: You are an expert in destination image perception, specializing in industrial tourism, with expertise in:

| Role: You are an expert in destination image perception, specializing in industrial tourism, with expertise in:

|

| Instructions | Your task is to analyze the text reviews in depth. Specific tasks are matching the text reviews to perceptual dimensions and providing confidence levels, ultimately outputting up to three valid matching dimensions. | Your task is to analyze the official text in depth. Specific tasks include splitting long texts into smaller chunks based on semantic boundaries; matching the text content to perceptual dimensions and providing confidence levels; ultimately outputting up to three valid matching dimensions. |

| Steps |

|

|

| End Goal | Output structured analysis results, including perceptual dimensions matching and confidence levels (sorted in descending order). The results must be presented in a modularized and clearly structured format to ensure effective text analysis. | Output structured analysis results, including perceptual dimensions matching and confidence levels (sorted in descending order). The results must be presented in a modularized and clearly structured format to ensure effective text analysis. |

| Narrowing |

|

|

| Input | Input data: Text reviews posted by the public on the Dianping platform. “It is rich in artistic atmosphere, can be regarded as the most instagrammable spot, which is great for wandering around.” | Input data: Official text content published on the platform. “Relevant data show that more than 300 enterprises have settled in this park … In 2025, Chengdu International Fashion Industrial Park will continue to promote digital transformation and introduce more international digital art exhibitions.” |

| Output | Comment Number: 1 Primary Dimension: Atmospheric experience Confidence Level: 0.9 Secondary Dimension: Art performances Confidence Level: 0.8 Third Dimension: null | Text Number: 1 “Relevant data shows that there are more than 300 enterprises settle in this park … ” Primary Dimension: Industrial form Confidence Level: 0.9 … Text Number: 2 “The proportion of business formats such as modern fashion, creative design, cultural and tourism consumption continues to expand … ” Primary Dimension: Industrial form Confidence Level: 0.9 … Text Number: 3 “In 2025, Chengdu International Fashion Industrial Park will give full play to the “early advantage” of digital transformation and development … ” Primary Dimension: Art performances Confidence Level: 0.9 … |

| Sentiment Values | User Star Ratings | Sentiment Label | Quantitative Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5, 4.5 | Very Positive | “very/too/extremely/completely” + positive word |

| 4 | 4, 3.5 | Positive | “Quite/comparatively/kinda/quite” + positive word |

| 3 | 3, 2.5 | Neutral | No clear emotional tendency or both positive and negative |

| 2 | 2, 1.5 | Negative | Adverbs of degree + negative words |

| 1 | 1, 0.5 | Very Negative | Strong adverbs + negative words |

| Step 1: Image-Text Prompt Engineering. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Role | Role: You are an expert in destination image perception, specializing in industrial tourism, with expertise in:

| ||

| Instructions | Your task is to recognize the core visual elements and key content within the image and generate semantically rich and coherent visual description text. | ||

| Steps |

| ||

| End Goal | Output structured analytical results, comprising the image sequence number and the image description content, to facilitate the transformation from image to text. | ||

| Narrowing | The description should be based on the visual elements visible in the image, and any speculation or derivation is prohibited. Output formatted in Markdown. | ||

| Input data | Image data released on the platforms by both the public and official. | ||

| Input |  |  |  |

| Output | There is a red mechanical device located on a circular grassy area. … The mechanical device appears to be part of a large grab bucket or crane, with a vibrant color. | The scene shows an indoor space with multiple paintings hanging on the wall, each varying in style and rich in color. The floor is gray, and several large metal frames are positioned within the space. | This picture depicts a modern architectural structure with a distinct industrial design style. … The building primarily consists of a metal framework with multiple floors inside. |

| Step 2: Text analysis prompt engineering. | |||

| Role | Consistent with the text analysis role description. | ||

| Instructions | Your task is to analyze the text in depth. Matching the text content with perceptual dimensions and outputting the best-matched dimension along with its confidence levels. | ||

| Steps |

| ||

| End goal | Output structured analysis results, including image sequence number, perceptual dimensions matching and confidence levels. The results must be presented in a modularized and clearly structured format to effectively accomplish image-text analysis. | ||

| Narrowing |

| ||

| Input | Image Serial Number: 1328776515.0_1 There is a red mechanical device located on a circular grassy area… | Image Serial Number: 1792521113.0_0 The scene shows an indoor space with multiple paintings hanging on the wall… | Image Serial Number: 1529806494.0_2 This picture depicts a modern architectural structure… |

| Output | Image Serial Number: 1328776515.0_1 Matching dimension: Industrial relics Confidence Level: 0.9 | Image Serial Number: 1792521113.0_0 Matching dimension: Art performances Confidence Level: 0.9 | Image Serial Number: 1529806494.0_2 Matching dimension: Spatial layout Confidence Level: 0.9 |

| Dimension | Sub-Dimension | Official Projected | Public Perceived | χ2 | p | φ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |||||

| Cultural value of heritage | Industrial relics | 692 | 11.56% | 11,600 | 12.89% | 8.929 | <0.001 | 0.0096 |

| Historical ambiance | 563 | 9.4% | 3137 | 3.49% | 530.305 | <0.001 | 0.0743 | |

| Cultural memory | 540 | 9.02% | 3094 | 3.44% | 479.953 | <0.001 | 0.0707 | |

| Nostalgic feelings | 179 | 2.99% | 1372 | 1.52% | 75.783 | <0.01 | 0.0281 | |

| Total | 1974 | 32.97% | 19,203 | 21.34% | ||||

| Spatial environmental perception | Spatial layout | 439 | 7.33% | 7460 | 8.29% | 6.818 | <0.001 | 0.0084 |

| Environmental landscape | 279 | 4.66% | 9259 | 10.29% | 198.752 | <0.001 | 0.0455 | |

| Total | 718 | 11.99% | 16,719 | 18.58% | ||||

| Creative industry form | Art performances | 691 | 11.54% | 13,821 | 15.36% | 63.745 | <0.001 | 0.0258 |

| Design innovation | 468 | 7.82% | 3025 | 3.36% | 317.698 | <0.001 | 0.0575 | |

| Industrial form | 1044 | 17.43% | 8032 | 8.92% | 474.958 | <0.001 | 0.0703 | |

| Total | 2203 | 36.79% | 24,878 | 27.64% | ||||

| Service experience perception | Supporting facilities | 183 | 3.06% | 8381 | 9.31% | 270.429 | <0.001 | 0.0531 |

| Atmosphere experience | 661 | 11.04% | 14,070 | 15.63% | 91.237 | <0.001 | 0.0308 | |

| Consumption experience | 249 | 4.16% | 6748 | 7.5% | 92.652 | <0.001 | 0.031 | |

| Total | 1093 | 18.25% | 29,199 | 32.44% | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Hu, B.; Zhao, J. Official Projection vs. Public Perception: Measuring the Perceptual Discrepancy of Creative Industry Parks in the Industrial Heritage Category Using Large Language Models. Land 2025, 14, 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122371

Yang X, Hu B, Zhao J. Official Projection vs. Public Perception: Measuring the Perceptual Discrepancy of Creative Industry Parks in the Industrial Heritage Category Using Large Language Models. Land. 2025; 14(12):2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122371

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiaoke, Bin Hu, and Jingwei Zhao. 2025. "Official Projection vs. Public Perception: Measuring the Perceptual Discrepancy of Creative Industry Parks in the Industrial Heritage Category Using Large Language Models" Land 14, no. 12: 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122371

APA StyleYang, X., Hu, B., & Zhao, J. (2025). Official Projection vs. Public Perception: Measuring the Perceptual Discrepancy of Creative Industry Parks in the Industrial Heritage Category Using Large Language Models. Land, 14(12), 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122371