Mapping Urban Environmental Quality in Isfahan: A Scenario-Driven Framework for Decision Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Method

3.2.1. Evaluation Criteria

3.2.2. Standardization of Evaluation Criteria

3.2.3. Determination of the Weight of Evaluation Criteria

3.2.4. Combining Evaluation Criteria and Scenario Development

3.2.5. Evaluation and Spatial Analysis of UEQ Variations Across Scenarios

3.2.6. Dynamic ORness Computation and Stakeholder Preference Integration

3.2.7. Variability Evaluation and Degree of Agreement in UEQ Assessment

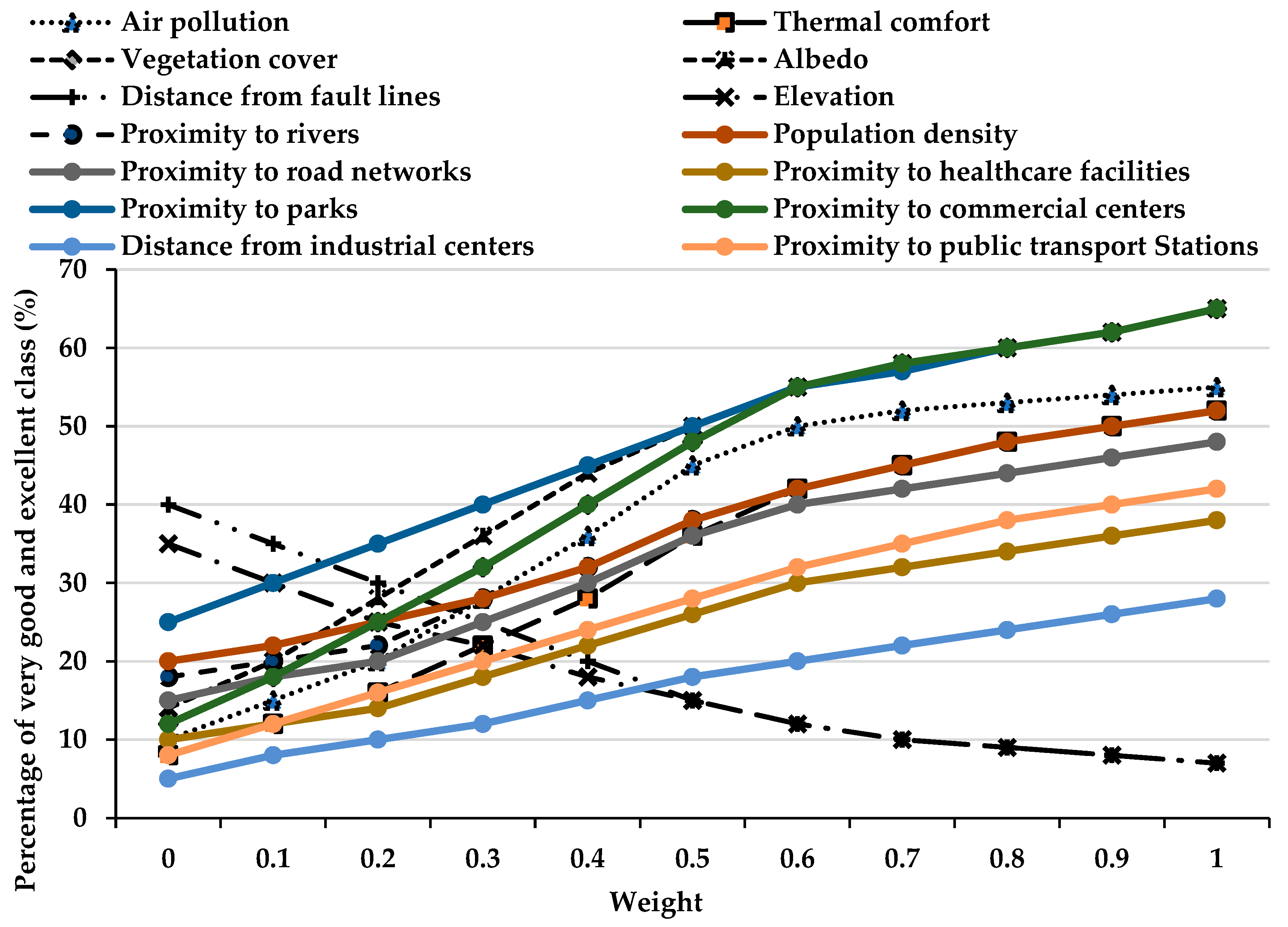

3.2.8. Sensitivity Analysis

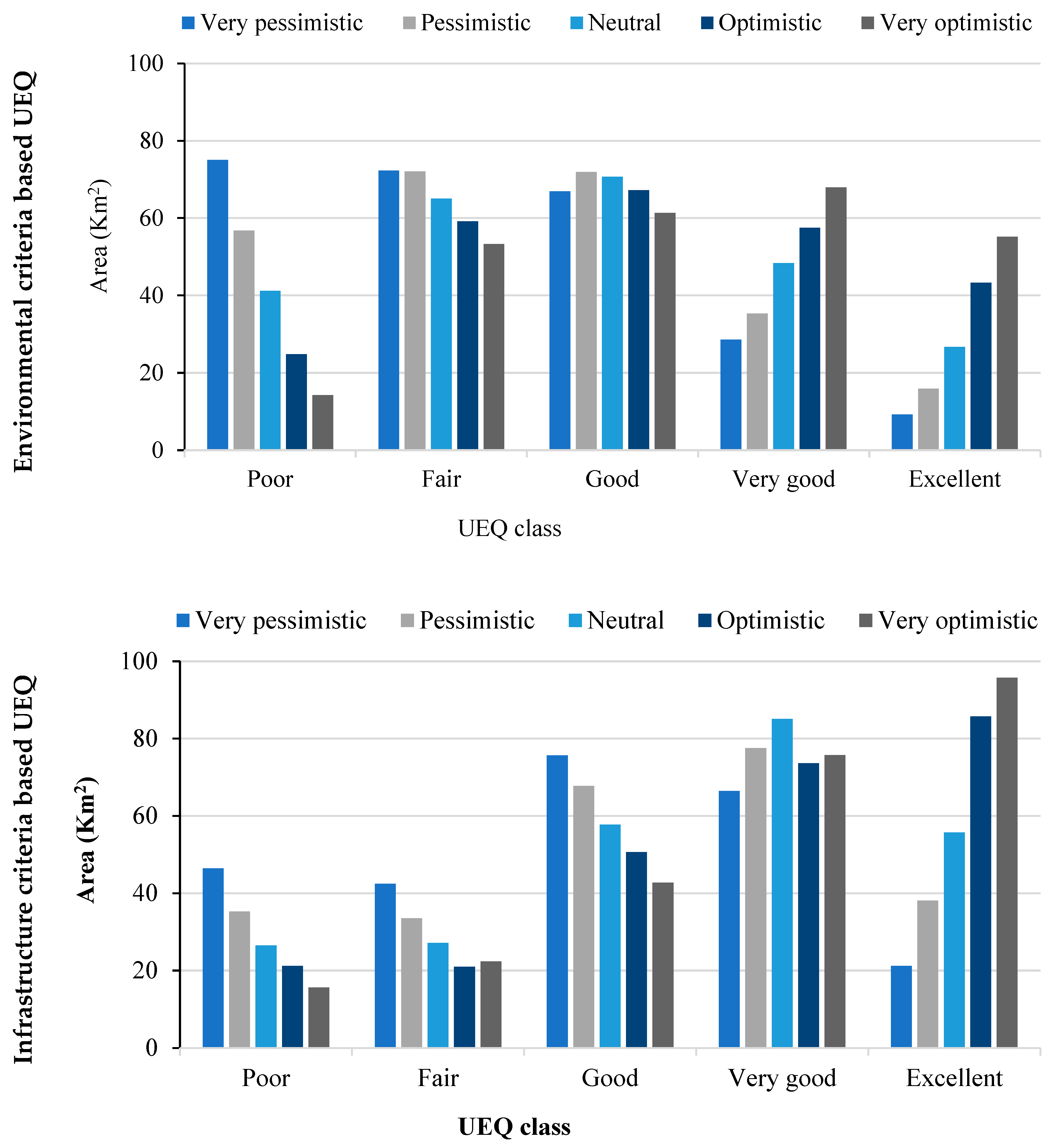

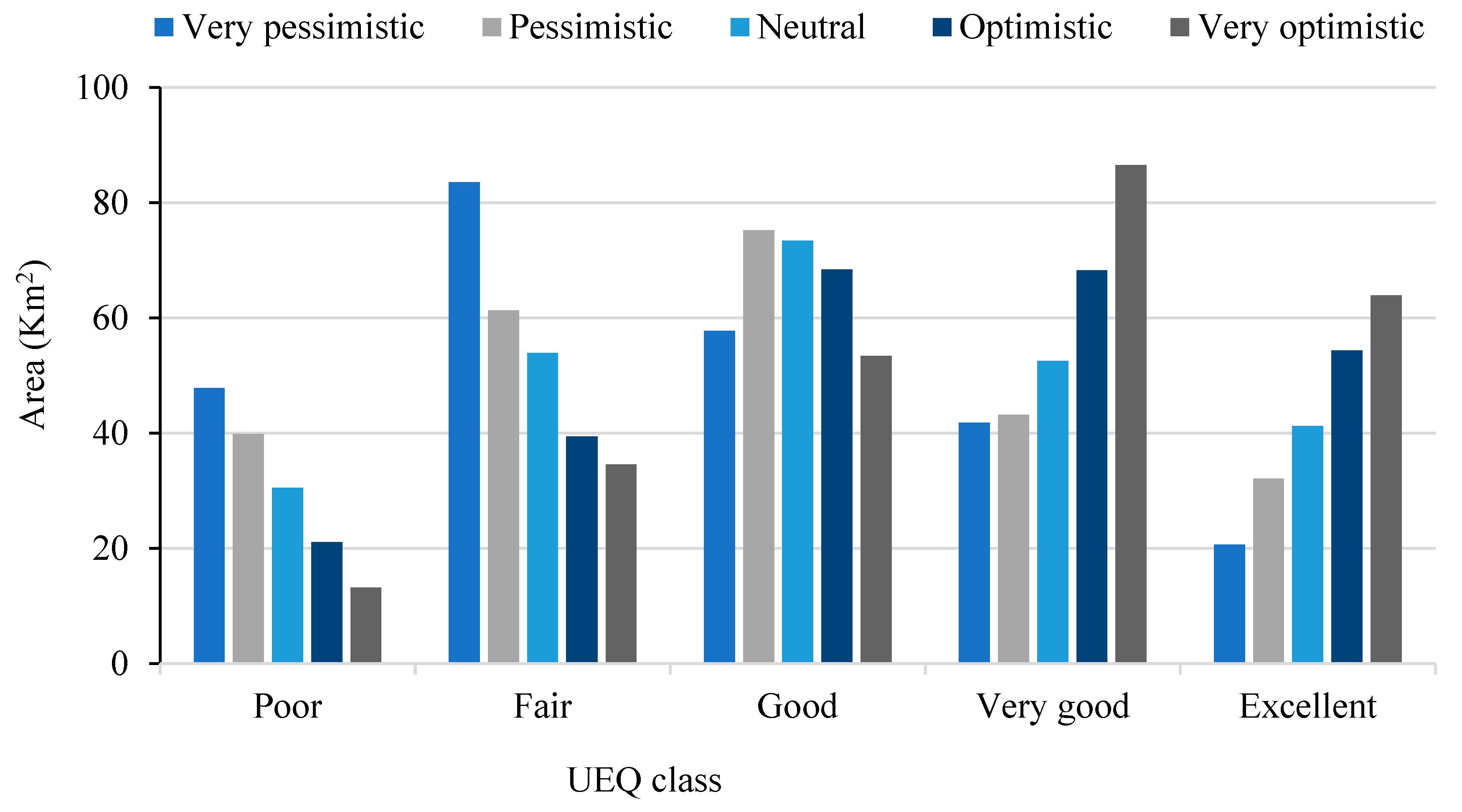

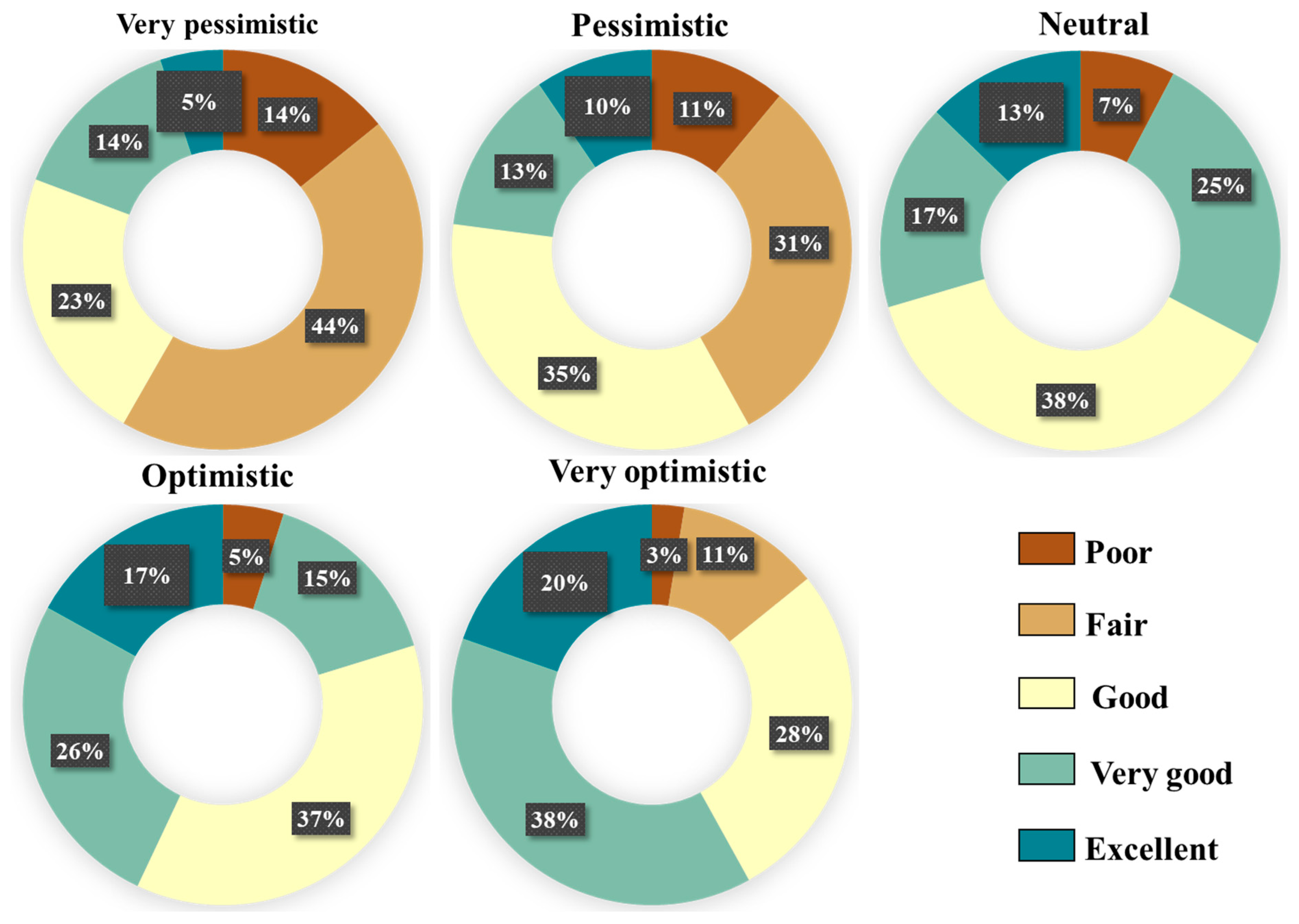

4. Results

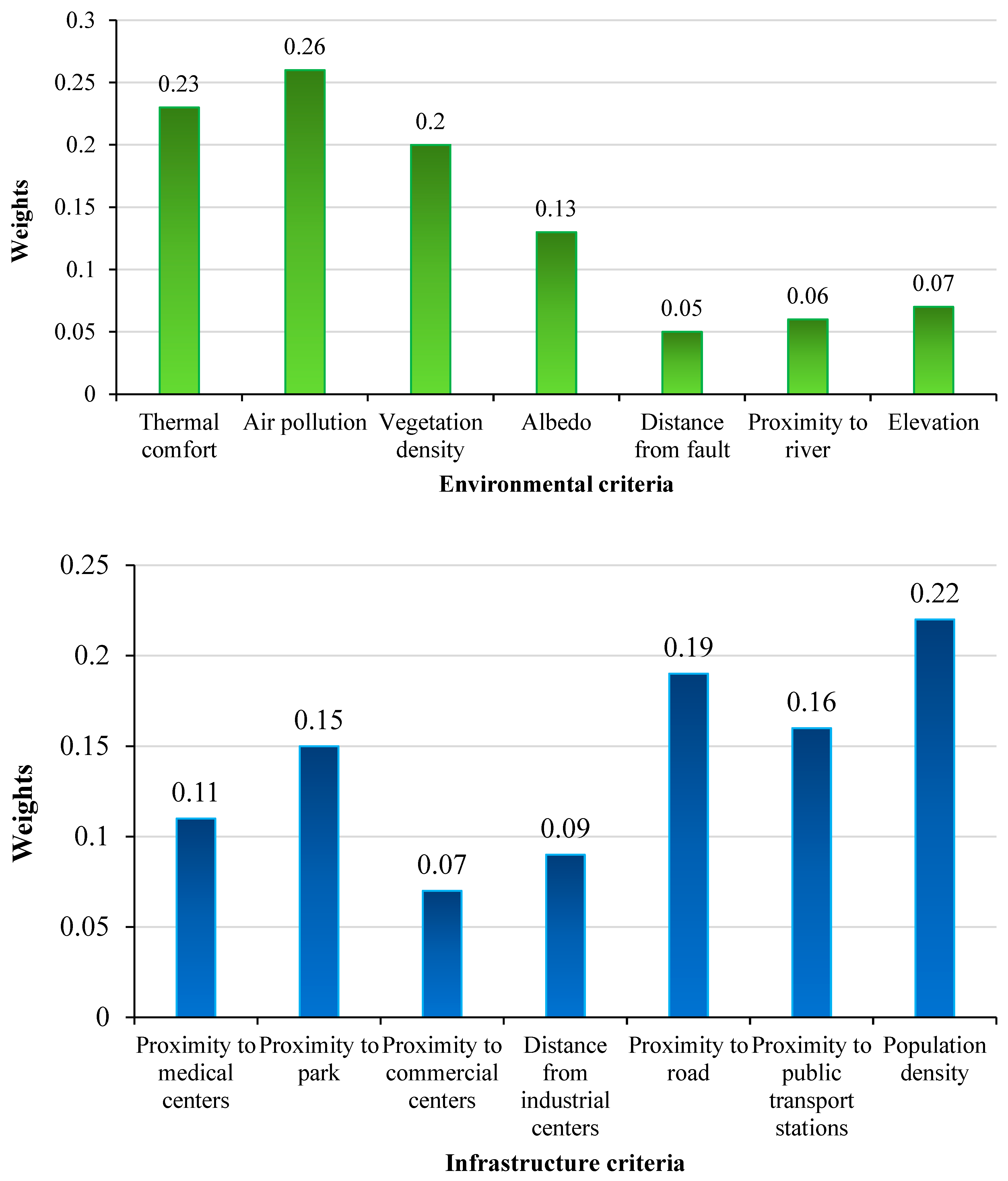

Weights of Evaluation Criteria

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stone, B. Urban sprawl and air quality in large US cities. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Weng, Q.; Zhao, C.; Kiavarz, M.; Lu, L.; Alavipanah, S.K. Surface anthropogenic heat islands in six megacities: An assessment based on a triple-source surface energy balance model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 242, 111751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Sedighi, A.; Kiavarz, M.; Alavipanah, S.K. Statistical analysis of surface urban heat island intensity variations: A case study of Babol city, Iran. GIScience Remote Sens. 2019, 56, 576–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Mijani, N.; Fathololoumi, S.; Arsanjani, J.J. Forecasting spatiotemporal dynamics of daytime surface urban cool islands in response to urbanization in drylands: Case study of Kerman and Zahedan Cities, Iran. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Firozjaei, M.; Mijani, N.; Nadizadeh Shorabeh, S.; Kazemi, Y.; Ebrahimian Ghajari, Y.; Jokar Arsanjani, J.; Kiavarz, M.; Alavipanah, S.K. Assessing the Effect of Urban Growth on Surface Ecological Status Using Multi-Temporal Satellite Imagery: A Multi-City Analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martek, I.; Hosseini, M.R.; Shrestha, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Seaton, S. The sustainability narrative in contemporary architecture: Falling short of building a sustainable future. Sustainability 2018, 10, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Sedighi, A.; Argany, M.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M.; Arsanjani, J.J. A geographical direction-based approach for capturing the local variation of urban expansion in the application of CA-Markov model. Cities 2019, 93, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marans, R.W. Quality of urban life & environmental sustainability studies: Future linkage opportunities. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; Akbari, R.; Taghavi, S.R.; Fardad, F.; Esmailzadeh, A.; Ahmadi, M.Z.; Attarroshan, S.; Nickravesh, F.; Jokar Arsanjani, J.; Amirkhani, M. A scenario-based spatial multi-criteria decision-making system for urban environment quality assessment: Case study of tehran. Land 2023, 12, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musse, M.A.; Barona, D.A.; Rodriguez, L.M.S. Urban environmental quality assessment using remote sensing and census data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 71, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Bose, A.; Majumder, S.; Roy Chowdhury, I.; Abdo, H.G.; Almohamad, H.; Abdullah Al Dughairi, A. Evaluating urban environment quality (UEQ) for Class-I Indian city: An integrated RS-GIS based exploratory spatial analysis. Geocarto Int. 2022, 38, 2153932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martek, I.; Hosseini, M.R.; Shrestha, A.; Edwards, D.J.; Seaton, S.; Costin, G. End-user engagement: The missing link of sustainability transition for Australian residential buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 224, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.S.; Firoz, C.M. Regional urban environmental quality assessment and spatial analysis. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Gao, W.; Shi, T.; Liu, X.; Wu, G. Rapid urbanization and policy variation greatly drive ecological quality evolution in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area of China: A remote sensing perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, C.; Carpentieri, G. Quality of life in the urban environment and primary health services for the elderly during the Covid-19 pandemic: An application to the city of Milan (Italy). Cities 2021, 110, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.A.E.E. Enhancing quality of life through strategic urban planning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2012, 5, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, K.E. Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously: Economic Development, the Environment, and Quality of Life in American Cities; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.; Smith, M.K. Residents’ quality of life in smart cities: A systematic literature review. Land 2023, 12, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.; Wang, F.; Wang, L. GIS-based assessment of urban environmental quality in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, J.; Asadi-Lari, M.; Baghbanian, A.; Ghaem, H.; Kassani, A.; Rezaianzadeh, A. Association between social capital, health-related quality of life, and mental health: A structural-equation modeling approach. Croat. Med. J. 2016, 57, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miremadi, M.; Bandari, R.; Heravi-Karimooi, M.; Rejeh, N.; Sharif Nia, H.; Montazeri, A. The Persian short form aging perceptions questionnaire (APQ-P): A validation study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aithal, A.; Aithal, P. Development and validation of survey questionnaire & experimental data–a systematical review-based statistical approach. Int. J. Manag. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2020, 5, 233–251. [Google Scholar]

- Fradelos, E.C.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Mitsi, D.; Tsaras, K.; Kleisiaris, C.F.; Kourkouta, L. Health based geographic information systems (GIS) and their applications. Acta Inform. Medica 2014, 22, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akyol, E.; Alkan, M.; Kaya, A.; Tasdelen, S.; Aydin, A. Environmental urbanization assessment using gis and multicriteria decision analysis: A case study for Denizli (Turkey) municipal area. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 6915938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J.; Rinner, C. Multicriteria Decision Analysis in Geographic Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, R.C.; Hippensteel, C.; Nelson, V.; Greene-Moton, E.; Furr-Holden, C.D. Community-engaged development of a GIS-based healthfulness index to shape health equity solutions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 227, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El Karim, A.; Awawdeh, M.M. Integrating GIS accessibility and location-allocation models with multicriteria decision analysis for evaluating quality of life in Buraidah city, KSA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Nematollahi, O.; Mijani, N.; Shorabeh, S.N.; Firozjaei, H.K.; Toomanian, A. An integrated GIS-based Ordered Weighted Averaging analysis for solar energy evaluation in Iran: Current conditions and future planning. Renew. Energy 2019, 136, 1130–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabihi, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Kibet Langat, P.; Karami, M.; Shahabi, H.; Ahmad, A.; Nor Said, M.; Lee, S. GIS multi-criteria analysis by ordered weighted averaging (OWA): Toward an integrated citrus management strategy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragih, D.P.; Purba, M.; Pariawan, S.P.D. The advantages of the ordered weighted averaging (OWA) method in decision making and reliability testing of spatial multi-criteria site selection (SMCSS) model. Indones. J. Geogr. 2024, 56, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, C.S.; Lee, B.K.; Turner, S. A tale of three greenway trails: User perceptions related to quality of life. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 49, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijani, N.; Alavipanah, S.K.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Arsanjani, J.J.; Hamzeh, S.; Weng, Q. Modeling outdoor thermal comfort using satellite imagery: A principle component analysis-based approach. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijani, N.; Alavipanah, S.K.; Hamzeh, S.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Arsanjani, J.J. Modeling thermal comfort in different condition of mind using satellite images: An Ordered Weighted Averaging approach and a case study. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 104, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Firozjaei, M.; Mahmoodi, H.; Jokar Arsanjani, J. Daytime Surface Urban Heat Island Variation in Response to Future Urban Expansion: An Assessment of Different Climate Regimes. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, F.; Rahimi, A.; Tarashkar, M.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Ioja, C.; Ondrejicka, V.; Finka, M. Assessing the Green Infrastructure and Built Up effects in Enhancing Thermal Comfort for Vulnerable Populations in Urban Heat Waves: A Case Study of Tabriz Metropolitan. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 39, 101671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelata, A.; Sodoudi, S. Evaluating urban vegetation scenarios to mitigate urban heat island and reduce buildings’ energy in dense built-up areas in Cairo. Build. Environ. 2019, 166, 106407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Zong, J.; Xiao, X. Assessing spatial-temporal dynamics of urban expansion, vegetation greenness and photosynthesis in megacity Shanghai, China during 2000–2016. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 233, 111374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.K. Effect of urban surface albedo enhancement in India on regional climate cooling. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2017, 8, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, M. The impact of increasing urban surface albedo on outdoor summer thermal comfort within a university campus. Urban Clim. 2018, 24, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y. The impact of building density and building height heterogeneity on average urban albedo and street surface temperature. Build. Environ. 2015, 90, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsari, R.; Nadizadeh Shorabeh, S.; Bakhshi Lomer, A.R.; Homaee, M.; Arsanjani, J.J. Using artificial neural networks to assess earthquake vulnerability in urban blocks of Tehran. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksha, S.K.; Juran, L.; Resler, L.M.; Zhang, Y. An analysis of social vulnerability to natural hazards in Nepal using a modified social vulnerability index. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2019, 10, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yue, W.; Fan, P.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J. Assessing the urban environmental quality of mountainous cities: A case study in Chongqing, China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 81, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Kumar, Y.; Fazal, S.; Bhaskaran, S. Urbanization and quality of urban environment using remote sensing and GIS techniques in East Delhi-India. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2011, 3, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, C.M.; Kihal-Talantikit, W.; Perez, S.; Deguen, S. Use of geographic indicators of healthcare, environment and socioeconomic factors to characterize environmental health disparities. Environ. Health 2016, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigolon, A. Parks and young people: An environmental justice study of park proximity, acreage, and quality in Denver, Colorado. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.R.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Cotinez-O’Ryan, A.; Miranda, J.J. Park use, perceived park proximity, and neighborhood characteristics: Evidence from 11 cities in Latin America. Cities 2020, 105, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudzadeh, H.; Abedini, A.; Aram, F.; Mosavi, A. Evaluating urban environmental quality using multi criteria decision making. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Deng, W. Industrial structure change and its eco-environmental influence since the establishment of municipality in Chongqing, China. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2010, 2, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarazzo, V.; Coppola, P.; Dell’Olio, L.; Ibeas, A.; Ottomanelli, M. The effects of environmental quality on residential choice location. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 162, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, J.; Zhao, Q. Local environmental factors in walking distance at metro stations. Public Transport 2018, 10, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorabeh, S.N.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Nematollahi, O.; Firozjaei, H.K.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M. A risk-based multi-criteria spatial decision analysis for solar power plant site selection in different climates: A case study in Iran. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 958–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Firozjaei, M.; Sedighi, A.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M. An urban growth simulation model based on integration of local weights and decision risk values. Trans. GIS 2020, 24, 1695–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, R.; Fathololoumi, S.; Soltanbeygi, M.; Firozjaei, M.K. A Sustainability-Oriented Spatial Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Framework for Optimizing Recreational Ecological Park Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompf, K.; Traverso, M.; Hetterich, J. Using analytical hierarchy process (AHP) to introduce weights to social life cycle assessment of mobility services. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.L.; Mak, H.W.L. From comparative and statistical assessments of liveability and health conditions of districts in Hong Kong towards future city development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorabeh, S.N.; Varnaseri, A.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Nickravesh, F.; Samany, N.N. Spatial modeling of areas suitable for public libraries construction by integration of GIS and multi-attribute decision making: Case study Tehran, Iran. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2020, 42, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamalizadeh, A.; Shorabeh, S.N.; Choubineh, K.; Karimi, A.; Ghahremani, L.; Firozjaei, M.K. Exploring the climatic conditions effect on spatial urban photovoltaic systems development using a spatial multi-criteria decision analysis: A multi-city analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 116, 105941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, R.R. On ordered weighted averaging aggregation operators in multicriteria decisionmaking. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1988, 18, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J. Ordered weighted averaging with fuzzy quantifiers: GIS-based multicriteria evaluation for land-use suitability analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2006, 8, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J.; Liu, X. Local ordered weighted averaging in GIS-based multicriteria analysis. Ann. GIS 2014, 20, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yi, S.; Tang, Z. Integrated flood hazard assessment based on spatial ordered weighted averaging method considering spatial heterogeneity of risk preference. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiavarz, M.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M. Geothermal prospectivity mapping using GIS-based Ordered Weighted Averaging approach: A case study in Japan’s Akita and Iwate provinces. Geothermics 2017, 70, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, N.; Taheri, Z.; Jokar Arsanjani, J.; Firozjaei, M.K. A Scenario-Based Framework to Optimising Eco-Wellness Tourism Development and Creating Niche Markets: A Case Study of Ardabil, Iran. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thokala, P.; Madhavan, G. Stakeholder involvement in multi-criteria decision analysis. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.S. Parameterized OWA operator weights: An extreme point approach. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2010, 51, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrouznejad, A.; Marra, M. Ordered weighted averaging operators 1988–2014: A citation-based literature survey. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2014, 29, 994–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Abdeyazdan, H.; Esmailzadeh, A.; Sedighi, A. Optimizing urban solar photovoltaic potential: A large group spatial decision-making approach for Tehran. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 85, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fildes, S.G.; Bruce, D.; Clark, I.F.; Raimondo, T.; Keane, R.; Batelaan, O. Integrating spatially explicit sensitivity and uncertainty analysis in a multi-criteria decision analysis-based groundwater potential zone model. J. Hydrol. 2022, 610, 127837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Khan, S. Spatial sensitivity analysis of multi-criteria weights in GIS-based land suitability evaluation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 1582–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, K.; Ali, M.; Abd Rahman, N.; Mispan, M. Application on one-at-a-time sensitivity analysis of semi-distributed hydrological model in tropical watershed. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2016, 8, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yun, S.-T.; Hwang, S.-I.; Chae, G. One-at-a-time sensitivity analysis of pollutant loadings to subsurface properties for the assessment of soil and groundwater pollution potential. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 21216–21238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Nezamabadi-Pour, H. Using gravitational search algorithm in prototype generation for nearest neighbor classification. Neurocomputing 2015, 157, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanolya, N.M.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M.; Toomanian, A. Validation of spatial multicriteria decision analysis results using public participation GIS. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 112, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, C.; Kabak, M.; Erbaş, M.; Özceylan, E. Evaluation of ecotourism sites: A GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis. Kybernetes 2018, 47, 1664–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigović, L.; Pamučar, D.; Lukić, D.; Marković, S. GIS-Fuzzy DEMATEL MCDA model for the evaluation of the sites for ecotourism development: A case study of “Dunavski ključ” region, Serbia. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajer, E.; Demir, S. Ecotourism strategy of UNESCO city in Iran: Applying a new quantitative method integrated with BWM. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymaz, Ç.K.; Çakır, Ç.; Birinci, S.; Kızılkan, Y. GIS-Fuzzy DEMATEL MCDA model in the evaluation of the areas for ecotourism development: A case study of “Uzundere”, Erzurum-Turkey. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 136, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Melón, M.; Gómez-Navarro, T.; Acuña-Dutra, S. A combined ANP-delphi approach to evaluate sustainable tourism. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2012, 34, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J.; Chapman, T.; Flegel, C.; Walters, D.; Shrubsole, D.; Healy, M.A. GIS–multicriteria evaluation with ordered weighted averaging (OWA): Case study of developing watershed management strategies. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1769–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorabeh, S.N.; Firozjaei, H.K.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M.; Homaee, M.; Nematollahi, O. The site selection of wind energy power plant using GIS-multi-criteria evaluation from economic perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wu, W.; Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Li, L. Socioeconomic factors behind the relationship between urban expansion and ecosystem services: A multiscale study in China. Landsc. Ecol. 2025, 40, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannico, V.; Spano, G.; Elia, M.; D’Este, M.; Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R. Green spaces, quality of life, and citizen perception in European cities. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Su, M.; Chen, B.; Chen, S.; Liang, C. A comparative study of Beijing and three global cities: A perspective on urban livability. Front. Earth Sci. 2011, 5, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, R.L. Urban sustainability and the urban forms of China’s leading mega cities: Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Urban Policy Res. 2012, 30, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, H.W.L.; Laughner, J.L.; Fung, J.C.H.; Zhu, Q.; Cohen, R.C. Improved satellite retrieval of tropospheric NO2 column density via updating of air mass factor (AMF): Case study of Southern China. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffin, S.R.; Rosenzweig, C.; Xing, X.; Yetman, G. Downscaling and geo-spatial gridding of socio-economic projections from the IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES). Glob. Environ. Change 2004, 14, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Brussel, S.; Huyse, H. Citizen science on speed? Realising the triple objective of scientific rigour, policy influence and deep citizen engagement in a large-scale citizen science project on ambient air quality in Antwerp. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liang, W. Assessing urban environmental quality and citizen science data quality: Identifying indicator bird species in cities of China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 59, e03575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, A.C.; Grythe, H.; Hellebust, S.; Lopez-Aparicio, S.; O’Dowd, C.; Hamer, P.D.; Santos, G.S.; Nyhan, M.M. Data fusion for enhancing urban air quality modeling using large-scale citizen science data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 116, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraisl, D.; Hager, G.; Bedessem, B.; Gold, M.; Hsing, P.-Y.; Danielsen, F.; Hitchcock, C.B.; Hulbert, J.M.; Piera, J.; Spiers, H. Citizen science in environmental and ecological sciences. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Criteria | Data | Format | Source/Provider | Original Resolution/Scale | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental criteria | Land Surface Temperature (LST) | Tiff | Landsat Collection 2 Level-2 Images | 30 m | https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 20 April 2025) |

| Albedo Surface | |||||

| Vegetation (NDVI) | |||||

| Elevation | ASTER Digital Elevation Model | 30 m | https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 20 April 2025) | ||

| Air Pollution | Sentinel 5 Greenhouse Gas Products/MOD04 AOD from MODIS Terra | 1000 m | https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/data-products and https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/ (accessed on 22 April 2025) | ||

| Fault Map | SHP (Polyline) | Geological Survey of Iran | 1:50,000 | - | |

| River Network | OpenStreetMap | 1:2000 | https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (accessed on 25 April 2025) | ||

| Infrastructure criteria | Road Network | ||||

| Industrial Areas | SHP (Polygon) | ||||

| Green Spaces and Parks | |||||

| Commercial and Service Centers | |||||

| public transport Stations (Bus and Metro) | SHP (Point) | ||||

| Healthcare Centers (Hospitals) | |||||

| Demographic Data | SHP (Polygon) | Iranian Statistical Center | Censes block | - |

| Main Criterion | Sub-Criterion | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental criteria | Air pollution | Air pollution is one of the major environmental challenges in large cities, with significant negative impacts on human health and the physical environment [31]. Pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, methane, and aerosols have been analyzed. |

| Thermal comfort | Thermal comfort plays an important role in the well-being and health of residents. Reduced thermal comfort leads to fatigue, sleep problems, decreased concentration, and even health threats [32,33,34]. This criterion is influenced by climatic conditions, biophysical surface characteristics, and urban structure [35]. | |

| Vegetation cover | Vegetation cover improves environmental quality by absorbing carbon dioxide, filtering pollution, and reducing air temperature. It also helps reduce the urban heat island effect and provides green, calming spaces for citizens [34,36,37]. | |

| Albedo | Albedo, or the amount of radiation reflected from the earth’s surface, is influenced by human activities and can affect the radiative balance and urban climate. Higher albedo typically improves environmental quality and helps cool urban heat islands [38,39,40]. | |

| Distance from fault lines | Proximity to fault lines increases seismic risks, threatening residential safety. Areas farther from fault lines have higher environmental quality and safety [41,42]. | |

| Elevation | Elevation and slope affect access to infrastructure and services. Areas with lower elevation typically have better access to facilities and services, leading to higher environmental quality [43]. | |

| Proximity to rivers | Rivers play an important role in improving UEQ. Proximity to rivers reduces temperature, increases humidity, enhances urban scenery, and creates green and recreational spaces [9]. Isfahan has only one significant river; lakes or seas are absent. | |

| Infrastructure criteria | Population density | Population density indicates the number of individuals per unit area. High population density may increase pressure on infrastructure and reduce quality of life, while lower density can enhance access to resources and open spaces, improving environmental quality [10,44]. |

| Proximity to road networks | Proximity to roads and networks can improve access to various services and infrastructure. This criterion enhances life quality and convenience for daily commuting, and is particularly important for transport and emergency access [9,41]. | |

| Proximity to healthcare facilities | Healthcare centers are essential for residents’ health and well-being. Proximity to these centers means faster access to emergency services and better overall health. This criterion contributes to residents’ welfare and safety, enhancing environmental quality [15,45]. | |

| Proximity to parks | Parks and green spaces help improve air quality, reduce stress, and provide recreational and social opportunities. Proximity to these spaces can increase residents’ comfort and well-being, improving UEQ [46,47]. | |

| Proximity to commercial centers | Proximity to commercial centers and stores allows residents to meet daily needs easily. This criterion improves well-being, reduces the need for long trips for shopping, and enhances urban life quality [19,48]. | |

| Distance from industrial centers | Proximity to industrial centers can have negative environmental and health impacts, as these areas are often sources of air and noise pollution. Greater distance from these centers reduces pollution and enhances environmental quality [9,49]. | |

| Proximity to public transport Stations | Access to public transportation stations, such as metro and bus stations, helps reduce private car usage, thus decreasing traffic and air pollution. Proximity to these stations also increases convenience for residents’ daily commuting [50,51]. |

| Districts | Very Pessimistic | Pessimistic | Neutral | Optimistic | Very Optimistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.3 | 11.6 | 19.0 | 36.7 | 51.0 |

| 2 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 8.1 | 12.1 |

| 3 | 6.5 | 10.7 | 15.5 | 25.4 | 32.6 |

| 4 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 12.0 |

| 5 | 22.5 | 32.8 | 40.0 | 47.9 | 52.4 |

| 6 | 13.9 | 19.1 | 23.1 | 27.8 | 30.6 |

| 7 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 3.5 |

| 8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 3.8 |

| 9 | 12.4 | 20.9 | 28.6 | 41.4 | 51.6 |

| 10 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 3.6 |

| 11 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 7.9 | 11.5 |

| 12 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| 13 | 25.7 | 42.5 | 52.7 | 62.1 | 67.5 |

| 14 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| 15 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taheri, Z.; Javid, M.; Esmaili, S.; Sedighi, A.; Karimi Firozjaei, M.; Haase, D. Mapping Urban Environmental Quality in Isfahan: A Scenario-Driven Framework for Decision Support. Land 2025, 14, 2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112213

Taheri Z, Javid M, Esmaili S, Sedighi A, Karimi Firozjaei M, Haase D. Mapping Urban Environmental Quality in Isfahan: A Scenario-Driven Framework for Decision Support. Land. 2025; 14(11):2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112213

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaheri, Zahra, Majid Javid, Saeideh Esmaili, Amir Sedighi, Mohammad Karimi Firozjaei, and Dagmar Haase. 2025. "Mapping Urban Environmental Quality in Isfahan: A Scenario-Driven Framework for Decision Support" Land 14, no. 11: 2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112213

APA StyleTaheri, Z., Javid, M., Esmaili, S., Sedighi, A., Karimi Firozjaei, M., & Haase, D. (2025). Mapping Urban Environmental Quality in Isfahan: A Scenario-Driven Framework for Decision Support. Land, 14(11), 2213. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112213