Exploring Community Residents’ Intentions to Support for Tourism in China’s National Park: A Two-Stage Structural Equation Modeling–Artificial Neural Network Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

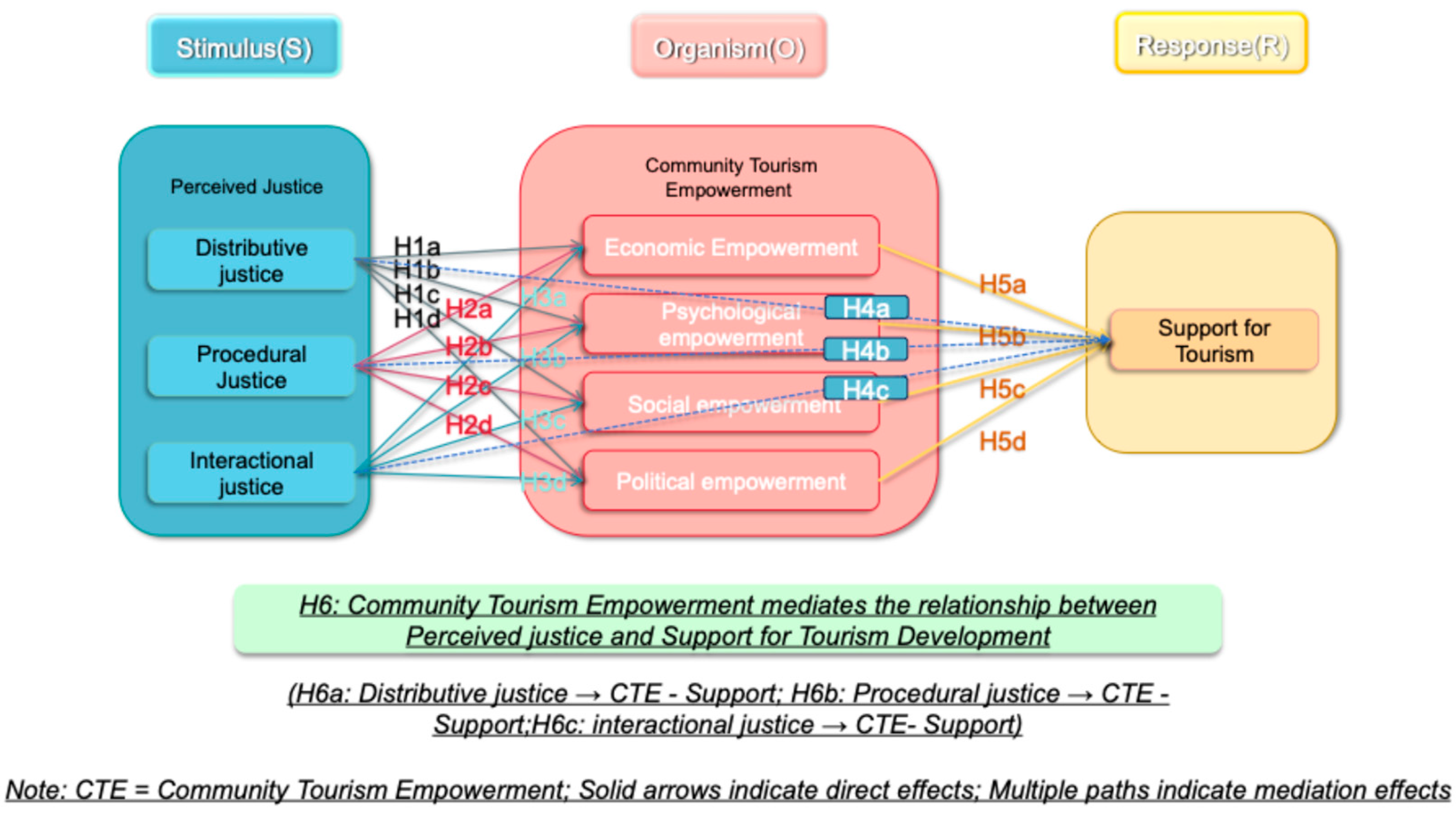

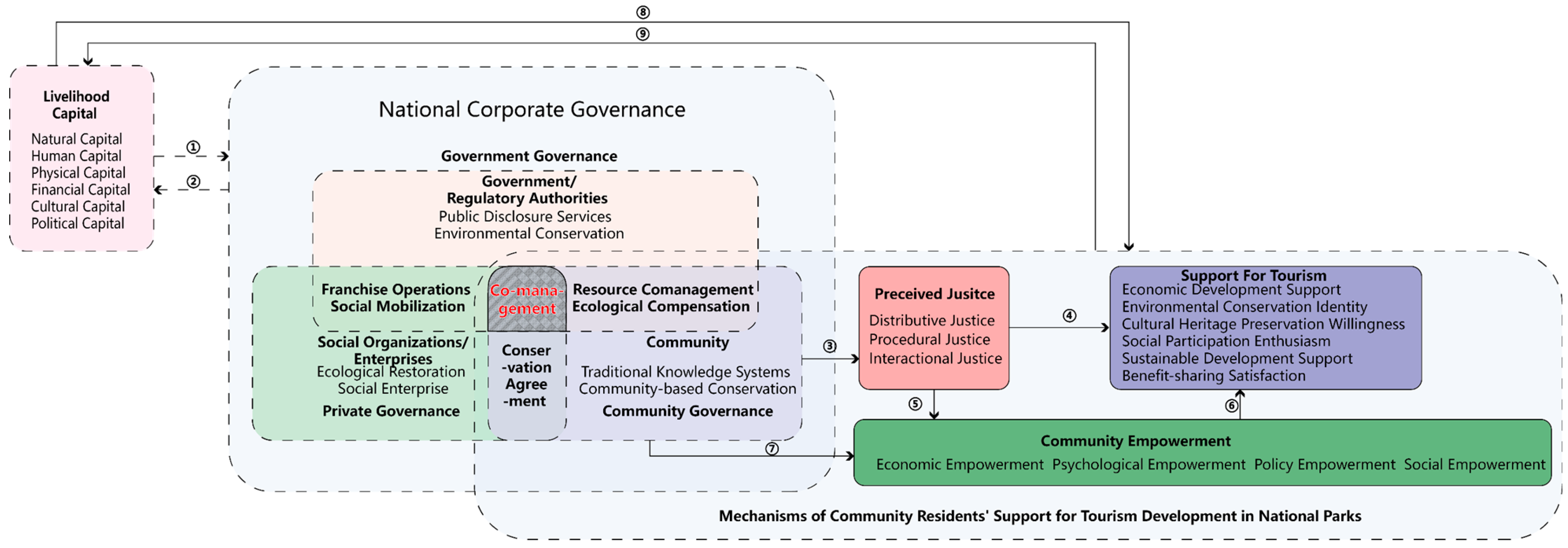

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) Theory

2.2. Perceived Justice

2.3. Community Tourism Empowerment

2.4. Support for Tourism

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Relationship Between Perceived Justice and Community-Based Tourism Empowerment

3.2. The Relationship Between Perceived Justice and Support for Tourism

3.3. The Relationship Between Community-Based Tourism Empowerment and Support for Tourism

3.4. Mediating Role of Community-Based Tourism Empowerment

4. Methods

4.1. Case Study Area

4.2. Data Collection and Sample

4.3. Research Instrument

4.4. Data Analysis Method

4.5. Non-Response Bias and Common Method Bias

5. Results

5.1. Assessing the Outer Measurement Model

5.2. Inspecting the Inner Structural Model

5.3. Mediating Effect of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness

5.4. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Analysis

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Implications

6.2.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2.2. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sample Size | Proportion (%) | Feature | Sample Size | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | ||||

| Male | 138 | 42.3 | 35 years old and below | 56 | 17.1 |

| Female | 188 | 57.7 | 36–44 years old | 47 | 14.4 |

| Educational Level | 45–54 years old | 83 | 25.5 | ||

| Primary school and below | 138 | 42.3 | 55–64 years old | 80 | 24.5 |

| Junior high school | 97 | 29.8 | 65 years old and above | 60 | 18.4 |

| High school or technical secondary school | 46 | 14.1 | Occupation | ||

| Bachelor’s degree and above (including college) | 45 | 13.8 | Self-employed | 166 | 50.9 |

| Length of Residence | Public institution/Civil servant | 22 | 6.7 | ||

| 11–20 years | 17 | 5.2 | Other | 15 | 4.6 |

| 21–30 years | 28 | 8.6 | Average Monthly Income | ||

| 31 years and above | 257 | 78.8 | Below 1000 yuan | 43 | 13.2 |

| Below 5 years | 17 | 5.2 | 1001–2000 yuan | 92 | 28.2 |

| 6–10 years | 7 | 2.1 | 2001–3000 yuan | 57 | 17.5 |

| Income Proportion from Tourism | 3001–4000 yuan | 60 | 18.4 | ||

| Partially from tourism | 188 | 57.7 | 4001–5000 yuan | 19 | 5.8 |

| Not related to tourism | 49 | 15.0 | 5001–6000 yuan | 20 | 6.1 |

| Mainly from tourism | 89 | 27.3 | Above 6001 yuan | 35 | 10.7 |

| Dimension | Variable | Item Code | Measurement Item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Justice | Distributive Justice | DJ1 | My tourism outcomes reflect my contribution to the village |

| DJ2 | Villagers with high tourism participation have high tourism outcomes | ||

| DJ3 | Considering the effort I put into my work, the tourism results I get are reasonable | ||

| DJ4 | Compared to other villagers in the village, the tourism outcomes I get are reasonable | ||

| Procedural Justice | PJ1 | My complaints in tourism development have been handled very promptly | |

| PJ2 | In tourism development, the procedures for handling my complaints are simple | ||

| PJ3 | The organization’s staff or employees make efforts to adjust the procedures for handling my complaints according to my needs in tourism development | ||

| PJ4 | My complaints can be resolved quickly | ||

| Interactional Justice | IJ1 | The organization’s staff or employees are very polite to me in tourism development | |

| IJ2 | The communication between the organization’s staff or employees and me is appropriate in tourism development | ||

| IJ3 | The organization’s staff or employees put appropriate effort into solving my problems in tourism development | ||

| IJ4 | The organization’s staff or employees show concern for tourism development | ||

| Community Tourism Empowerment | Economic Empowerment | EET1 | Local tourism development has improved my income level |

| EET2 | Local tourism development has increased my household income | ||

| EET3 | Part of my income or household income is related to local tourism development | ||

| EET4 | Local tourism development has created and provided me with more employment opportunities | ||

| Policy Empowerment | POET1 | I have opportunities and channels to provide opinions and ideas on local tourism development | |

| POET2 | When formulating local tourism development plans, I can participate and express my opinions and ideas | ||

| POET3 | I can participate in local tourism planning and express my opinions and ideas | ||

| POET4 | I can participate in local tourism decision-making (attending meetings, voting, expressing opinions) and have certain decision-making power in local tourism development | ||

| Social Empowerment | SET1 | Local tourism development has made my relationship with other people in the village/community closer | |

| SET2 | Local tourism development has made me more integrated into the village/community collective | ||

| SET3 | Local tourism development has provided me with more opportunities to participate in village/community collective affairs | ||

| SET4 | Local tourism development has strengthened my sense of collectivism | ||

| Psychological Empowerment | PET1 | I am proud to be a community villager where the national park is located | |

| PET2 | The high visibility of the national park has improved my local confidence | ||

| PET3 | Because many tourists come here for tourism, I feel that the natural resources, environment, and historical culture of the national park are of high quality and value, which is recognition of the local area | ||

| PET4 | Because many tourists come here for tourism, I feel that the natural resources, environment, and historical culture of the national park are of high quality and value, which is recognition of the local area | ||

| Support For Tourism | Tourism Support Level | S1 | I look forward to and welcome the arrival of tourists, and am willing to receive tourists warmly and friendly |

| S2 | I am willing to contribute to the sustainable development of local tourism | ||

| S3 | I am willing to participate in local tourism business activities (providing accommodation and catering services, etc.) | ||

| S4 | I am willing to support the management bureau/government/enterprises to increase investment in tourism development and build better tourism attractions | ||

| S5 | I am willing to participate in the benefit distribution of tourism development and share the results of local tourism development with stakeholders (other villagers, enterprises, managers) | ||

| S6 | My neighbors are willing to support local tourism development |

| Construct | Item | Substantive Outer Loading | Substantive Variance (Ra2) | Method Outer Loading (Rb) | Method Variance | FCT Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributive justice (DJ) | 1 | 0.714 | 0.510 | 0.077 | 0.006 | *** |

| 2 | 0.745 | 0.556 | 0.006 | 0.000 | ||

| 3 | 0.804 | 0.646 | −0.138 | 0.019 | ||

| 4 | 0.893 | 0.798 | −0.124 | 0.015 | ||

| Procedural Justice (PJ) | 1 | 0.870 | 0.757 | −0.044 | 0.002 | *** |

| 2 | 0.841 | 0.707 | −0.013 | 0.000 | ||

| 3 | 0.708 | 0.501 | 0.021 | 0.000 | ||

| 4 | 0.703 | 0.495 | −0.062 | 0.004 | ||

| Interactional justice (IJ) | 1 | 0.700 | 0.490 | −0.131 | 0.017 | *** |

| 2 | 0.744 | 0.554 | −0.122 | 0.015 | ||

| 3 | 0.778 | 0.606 | 0.135 | 0.018 | ||

| 4 | 0.731 | 0.535 | −0.011 | 0.000 | ||

| Community Tourism Economic Empowerment (ECET) | 1 | 0.725 | 0.525 | 0.094 | 0.009 | *** |

| 2 | 0.847 | 0.717 | −0.062 | 0.004 | ||

| 3 | 0.797 | 0.635 | 0.056 | 0.003 | ||

| 4 | 0.803 | 0.645 | −0.026 | 0.001 | ||

| Community Tourism Social Empowerment (SOET) | 1 | 0.686 | 0.470 | −0.121 | 0.015 | *** |

| 2 | 0.653 | 0.426 | −0.057 | 0.003 | ||

| 3 | 0.736 | 0.541 | −0.121 | 0.015 | ||

| 4 | 0.842 | 0.709 | 0.058 | 0.003 | ||

| Community Tourism Political Empowerment (POET) | 1 | 0.673 | 0.453 | 0.039 | 0.001 | *** |

| 2 | 0.749 | 0.560 | −0.075 | 0.006 | ||

| 3 | 0.857 | 0.735 | −0.018 | 0.000 | ||

| 4 | 0.730 | 0.532 | −0.121 | 0.015 | ||

| Community Tourism Psychological Empowerment (PSET) | 1 | 0.736 | 0.542 | 0.102 | 0.010 | *** |

| 2 | 0.647 | 0.419 | 0.115 | 0.013 | ||

| 3 | 0.890 | 0.792 | −0.124 | 0.015 | ||

| 4 | 0.659 | 0.434 | 0.090 | 0.008 | ||

| Support for tourism (SFT) | 1 | 0.804 | 0.647 | −0.041 | 0.002 | *** |

| 2 | 0.753 | 0.566 | −0.049 | 0.002 | ||

| 3 | 0.893 | 0.797 | −0.011 | 0.000 | ||

| 4 | 0.760 | 0.578 | 0.007 | 0.000 | ||

| 5 | 0.811 | 0.658 | −0.037 | 0.001 | ||

| 6 | 0.745 | 0.555 | −0.145 | 0.021 |

References

- Du, X.; Shen, Y.Q.; Xiao, Y.; Ouyang, Z.Y. Valuation of Ecological Products in National Parks. Available online: https://www.ecologica.cn/html/2023/1/stxb202112163575.htm (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Yang, W.; Sun, Z.; Wang, M.; Guan, H.; Yang, R. Research Context of Digital Villages at Home and Abroad from a Geographic Perspective. Prog. Geogr. 2025, 44, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Sun, H. Research on the Effect of Sustainable Livelihood in National Parks on Local Development Decision-making. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshliki, S.A.; Kaboudi, M. Community Perception of Tourism Impacts and Their Participation in Tourism Planning: A Case Study of Ramsar, Iran. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 36, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindrawati, D.Y. Challenges of community participation in tourism planning in developing countries. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2164240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyanto; Iqbal, M.; Supriono; Fahmi, M.R.A.; Yuliaji, E.S. The effect of community involvement and perceived impact on residents’ overall well-being: Evidence in Malang marine tourism. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2270800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peihai, D.; Wei, L.I. Research on the spatial effect and mechanism of community participation in tourism poverty alleviation from the perspective of geography. Ecotourism 2021, 11, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.M. Why Income Inequality Is Dissatisfying—Perceptions of Social Status and the Inequality-Satisfaction Link in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 35, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Van Der Watt, H. Tourism, Empowerment and Sustainable Development: A New Framework for Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkedder, N.; Bakır, M. A Hybrid Analysis of Consumer Preference for Domestic Products: Combining PLS-SEM and ANN Approaches. J. Glob. Mark. 2023, 36, 372–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; pp. xii, 266. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F. Hotel website quality, perceived flow, customer satisfaction and purchase intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2016, 7, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S. Towards an understanding of inequity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity In Social Exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; Volume 2, pp. 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, J.W.; Walker, L. Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1975; pp. 1–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bies, R.; Moag, J. Interactional Justice: Communication Criteria of Fairness|BibSonomy. Available online: https://www.bibsonomy.org/bibtex/3f5df0c0717e2f5aaafcb3f0afdf1f2a (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.N. Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Towards harmonious conservation relationships: A framework for understanding protected area staff-local community relationships in developing countries. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 25, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Nyaupane, G.P.; Budruk, M. Stakeholders’ Perspectives of Sustainable Tourism Development: A New Approach to Measuring Outcomes. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, S. Assessment of the main factors impacting community members’ attitudes towards tourism and protected areas in six southern African countries. Koedoe 2014, 56, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Filieri, R. Resident-tourist value co-creation: The role of residents’ perceived tourism impacts and life satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio, J.; Andriotis, K. Social representations and community attitudes towards spring breakers. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, S. The role of private sector ecotourism in local socio-economic development in southern Africa. J. Ecotourism 2017, 16, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, J.S. The influence of place identity on perceived tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. Community Based Tourism Sustainable Development in Kon Tum Province of Vietnam. Neuroquantology 2022, 20, 9314–9330. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G. Measuring empowerment: Developing and validating the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS). Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Camargo, B.A. Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the Just Destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Rodell, J.B.; Long, D.M.; Zapata, C.P.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Lind, E.A. A Relational Model of Authority in Groups. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 115–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Blader, S.L. The Group Engagement Model: Procedural Justice, Social Identity, and Cooperative Behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 7, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Empowerment and stakeholder participation in tourism destination communities. In Tourism, Power and Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S. Information and Empowerment: The Keys to Achieving Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofield, T.H.B. Empowerment for Sustainable Tourism Development. 2003. Available online: https://shop.elsevier.com/books/empowerment-for-sustainable-tourism-development/sofield/978-0-08-043946-4 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Blackstock, K. A critical look at community based tourism. Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G. Power relations and community-based tourism planning. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Timothy, D.J. (PDF) Arguments for Community Participation in the Tourism Development Process. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237203991_Arguments_for_Community_Participation_in_the_Tourism_Development_Process (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Bandura, A. Toward a Psychology of Human Agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Berbekova, A.; Uysal, M. Pursuing justice and quality of life: Supporting tourism. Tour. Manag. 2022, 89, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pfister, R.E. Residents’ Attitudes Toward Tourism and Perceived Personal Benefits in a Rural Community. J. Travel. Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Perdue, R.R.; Long, P. Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A.; Woosnam, K.M. Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Rigdon, E.E.; Straub, D. Editor’s Comments: An Update and Extension to SEM Guidelines for Administrative and Social Science Research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. Predicting the determinants of the NFC-enabled mobile credit card acceptance: A neural networks approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 5604–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, J.-J.; Leong, L.-Y.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Lee, V.-H.; Ooi, K.-B. Mobile social tourism shopping: A dual-stage analysis of a multi-mediation model. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PLS-SEM Book: A Primer on PLS-SEM, 3rd ed.; pls-sems Webseite! Available online: http://www.pls-sem.net/pls-sem-books/a-primer-on-pls-sem-3rd-ed/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Velasquez Estrada, J.M.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungtusanatham, M.; Miller, J.W.; Boyer, K.K. Theorizing, testing, and concluding for mediation in SCM research: Tutorial and procedural recommendations. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Ooi, K.-B.; Wei, J. Predicting mobile wallet resistance: A two-staged structural equation modeling-artificial neural network approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.K.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, L. Predicting and explaining patronage behavior toward web and traditional stores using neural networks: A comparative analysis with logistic regression. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 41, 514–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Marinković, V.; Kalinić, Z. A SEM-neural network approach for predicting antecedents of m-commerce acceptance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahani, A.; Rahim, N.Z.A.; Nilashi, M. Forecasting social CRM adoption in SMEs: A combined SEM-neural network method. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinić, Z.; Marinković, V.; Kalinić, L.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Neural network modeling of consumer satisfaction in mobile commerce: An empirical analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 175, 114803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D.; Jackson, D.A. Illuminating the “black box”: A randomization approach for understanding variable contributions in artificial neural networks. Ecol. Model. 2002, 154, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | County (City, District) | Township (Street) | Management Station | Administrative Village | Community Type | Main Industries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujian Region | ||||||

| Fujian Region | Wuyishan City | Xingcun Town | Xingcun Management Station | Tongmu Village | Internal Community | Tea Industry, Tourism |

| Fujian Region | Wuyishan City | Xingcun Town | Xingcun Management Station | Xingcun Village | Gateway Community | Tea Industry, Tourism |

| Fujian Region | Wuyishan City | Xingtian Town | Wuyi Management Station | Nanyuanling Village | Gateway Community | Tourism, Tea Industry |

| Fujian Region | Wuyishan City | Xingtian Town | Wuyi Management Station | Dazhou Village | Peripheral Community | Agriculture |

| Fujian Region | Guangze County | Zhaili Town | Zhaili Management Station | Baishi Village | Peripheral Community | Agriculture, Tobacco Leaves |

| Fujian Region | Guangze County | Zhaili Town | Zhaili Management Station | Taolin Village | Gateway Community | Tobacco Leaves, Edible Mushrooms |

| Fujian Region | Jianyang District | Huangkeng Town | Huangkeng Management Station | Aotou Village | Internal Community | Tea Industry, Beekeeping |

| Fujian Region | Jianyang District | Huangkeng Town | Huangkeng Management Station | Changjian Village | Gateway Community | Agriculture, Bamboo Industry |

| Jiangxi Region | ||||||

| Jiangxi Region | Yanshan County | Huangbi She Ethnic Township | Huangbi Management Station | Huangbi Village | Gateway Community | Tea Industry, Tourism |

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F Test | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFT × DJ | combined | 77.07 | 16 | 4.82 | 7.39 | 0.000 |

| Linearity | 48.38 | 1 | 48.38 | 74.25 | 0.000 | |

| Deviation from linearity | 28.69 | 15 | 1.91 | 2.94 | 0.015 | |

| SFT × PJ | combined | 54.56 | 16 | 3.41 | 4.71 | 0.000 |

| Linearity | 38.57 | 1 | 38.57 | 53.23 | 0.000 | |

| Deviation from linearity | 15.99 | 15 | 1.07 | 1.47 | 0.124 | |

| SFT × IJ | combined | 27.23 | 15 | 1.82 | 2.24 | 0.007 |

| Linearity | 17.65 | 1 | 17.65 | 21.78 | 0.000 | |

| Deviation from linearity | 9.58 | 14 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.622 | |

| SFT × ECET | combined | 28.46 | 16 | 1.78 | 2.20 | 0.006 |

| Linearity | 16.31 | 1 | 16.31 | 20.17 | 0.000 | |

| Deviation from linearity | 12.14 | 15 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.462 | |

| SFT × SOET | combined | 71.67 | 15 | 4.78 | 7.16 | 0.000 |

| Linearity | 56.86 | 1 | 56.86 | 85.25 | 0.000 | |

| Deviation from linearity | 14.81 | 14 | 1.06 | 1.59 | 0.092 | |

| SFT × POET | combined | 41.06 | 16 | 2.57 | 3.34 | 0.000 |

| Linearity | 31.76 | 1 | 31.76 | 41.34 | 0.000 | |

| Deviation from linearity | 9.30 | 15 | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.663 | |

| SFT × PSET | combined | 49.51 | 16 | 3.09 | 4.18 | 0.000 |

| Linearity | 35.76 | 1 | 35.76 | 48.28 | 0.000 | |

| Deviation from linearity | 13.75 | 15 | 0.92 | 1.24 | 0.259 |

| Construct | Item | Outer Loading | AVE | CR | Rho_A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributive Justice | 1 | 0.789 | 0.623 | 0.868 | 0.856 |

| 2 | 0.812 | ||||

| 3 | 0.798 | ||||

| 4 | 0.756 | ||||

| Procedural Justice | 1 | 0.834 | 0.682 | 0.895 | 0.887 |

| 2 | 0.847 | ||||

| 3 | 0.798 | ||||

| 4 | 0.823 | ||||

| Interactional Justice | 1 | 0.756 | 0.623 | 0.868 | 0.845 |

| 2 | 0.798 | ||||

| 3 | 0.812 | ||||

| 4 | 0.789 | ||||

| Community Tourism Economic Empowerment | 1 | 0.823 | 0.686 | 0.897 | 0.891 |

| 2 | 0.856 | ||||

| 3 | 0.834 | ||||

| 4 | 0.798 | ||||

| Community Tourism Social Empowerment | 1 | 0.867 | 0.719 | 0.911 | 0.912 |

| 2 | 0.845 | ||||

| 3 | 0.823 | ||||

| 4 | 0.856 | ||||

| Community Tourism Political Empowerment | 1 | 0.798 | 0.654 | 0.883 | 0.878 |

| 2 | 0.834 | ||||

| 3 | 0.812 | ||||

| 4 | 0.789 | ||||

| Community Tourism Psychological Empowerment | 1 | 0.812 | 0.668 | 0.890 | 0.886 |

| 2 | 0.789 | ||||

| 3 | 0.823 | ||||

| 4 | 0.845 | ||||

| Support For Tourism | 1 | 0.778 | 0.644 | 0.916 | 0.901 |

| 2 | 0.823 | ||||

| 3 | 0.845 | ||||

| 4 | 0.798 | ||||

| 5 | 0.812 | ||||

| 6 | 0.756 |

| SFT | DJ | PJ | IJ | ECET | SOET | POET | PSET | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFT | 0.752 | |||||||

| DJ | 0.417 | 0.798 | ||||||

| PJ | 0.372 | 0.305 | 0.785 | |||||

| IJ | 0.252 | 0.199 | 0.298 | 0.806 | ||||

| ECET | 0.242 | 0.398 | 0.294 | 0.357 | 0.773 | |||

| SOET | 0.452 | 0.333 | 0.284 | 0.239 | 0.313 | 0.791 | ||

| POET | 0.338 | 0.344 | 0.332 | 0.262 | 0.266 | 0.311 | 0.782 | |

| PSET | 0.358 | 0.348 | 0.424 | 0.285 | 0.337 | 0.327 | 0.340 | 0.768 |

| Effect | Stdβ | t-Value | 95%CIs | Remark | VIF | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||||

| H1 DJ→CTE | 0.391 | 6.854 | [0.279, 0.503] | Supported | 1.723 | 0.387 |

| H1a DJ→CTE(ECET) | 0.426 | 7.503 | [0.315, 0.537] | Supported | 1.658 | 0.342 |

| H1b DJ→CTE(POET) | 0.384 | 6.723 | [0.272, 0.496] | Supported | 1.689 | 0.298 |

| H1c DJ→CTE(PSET) | 0.371 | 6.512 | [0.259, 0.483] | Supported | 1.634 | 0.285 |

| H1d DJ→CTE(SOET) | 0.403 | 7.087 | [0.291, 0.515] | Supported | 1.712 | 0.324 |

| H2 PJ→CTE | 0.313 | 5.489 | [0.201, 0.425] | Supported | 1.847 | 0.387 |

| H2a PJ→CTE(ECET) | 0.349 | 6.125 | [0.237, 0.461] | Supported | 1.784 | 0.342 |

| H2b PJ→CTE(POET) | 0.295 | 5.178 | [0.183, 0.407] | Supported | 1.823 | 0.298 |

| H2c PJ→CTE(PSET) | 0.287 | 5.034 | [0.175, 0.399] | Supported | 1.756 | 0.285 |

| H2d PJ→CTE(SOET) | 0.331 | 5.801 | [0.219, 0.443] | Supported | 1.812 | 0.324 |

| H3 IJ→CTE | 0.272 | 4.767 | [0.160, 0.384] | Supported | 1.698 | 0.387 |

| H3a IJ→CTE(ECET) | 0.298 | 5.234 | [0.186, 0.410] | Supported | 1.623 | 0.342 |

| H3b IJ→CTE(POET) | 0.261 | 4.579 | [0.149, 0.373] | Supported | 1.667 | 0.298 |

| H3c IJ→CTE(PSET) | 0.254 | 4.456 | [0.142, 0.366] | Supported | 1.634 | 0.285 |

| H3d IJ→CTE(SOET) | 0.279 | 4.893 | [0.167, 0.391] | Supported | 1.656 | 0.324 |

| H4 JUSTICE→SFT | 0.347 | 6.500 | [0.242, 0.452] | Supported | 2.141 | 0.456 |

| H4a DJ→SFT | 0.417 | 7.321 | [0.305, 0.529] | Supported | 1.723 | 0.456 |

| H4b PJ→SFT | 0.372 | 6.534 | [0.260, 0.484] | Supported | 1.847 | 0.456 |

| H4c IJ→SFT | 0.252 | 4.423 | [0.140, 0.364] | Supported | 1.698 | 0.456 |

| H5 CTE→SFT | 0.495 | 8.689 | [0.383, 0.607] | Supported | 1.000 | 0.245 |

| H5a CTE(ECET)→SFT | 0.487 | 8.545 | [0.375, 0.599] | Supported | 2.145 | 0.534 |

| H5b CTE(POET)→SFT | 0.453 | 7.954 | [0.341, 0.565] | Supported | 2.089 | 0.534 |

| H5c CTE(PSET)→SFT | 0.469 | 8.234 | [0.357, 0.581] | Supported | 2.067 | 0.534 |

| H5d CTE(SOET)→SFT | 0.476 | 8.356 | [0.364, 0.588] | Supported | 2.123 | 0.534 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||

| H6 JUSTICE→CTE→SFT | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| H6a DJ→CTE→SFT | 0.194 | 4.234 | [0.108, 0.280] | Supported | - | - |

| H6b PJ→CTE→SFT | 0.155 | 3.512 | [0.069, 0.241] | Supported | - | - |

| H6c IJ→CTE→SFT | 0.135 | 3.089 | [0.049, 0.221] | Supported | - | - |

| Item | Q2 Predict | RMSE PLS-SEM | RMSE LM | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECET | 0.293 | 0.948 | 1.133 | −0.185 |

| SOET | 0.249 | 1.055 | 1.226 | −0.171 |

| POET | 0.284 | 0.858 | 1.021 | −0.164 |

| PSET | 0.264 | 0.887 | 1.053 | −0.166 |

| SFT1 | 0.187 | 1.028 | 1.150 | −0.122 |

| SFT2 | 0.094 | 1.057 | 1.121 | −0.064 |

| SFT3 | 0.105 | 1.158 | 1.233 | −0.075 |

| SFT4 | 0.159 | 1.029 | 1.129 | −0.100 |

| SFT5 | 0.171 | 1.026 | 1.135 | −0.109 |

| SFT6 | 0.114 | 1.050 | 1.129 | −0.079 |

| Neural Network | Modal A | Modal B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input: DJ, PJ, IJ; Output: CTE | Input: DJ, PJ, IJ, CTE; Output: SFT | |||

| Training | Testing | Training | Testing | |

| ANN1 | 0.532 | 0.426 | 0.781 | 0.687 |

| ANN2 | 0.525 | 0.500 | 0.769 | 0.810 |

| ANN3 | 0.519 | 0.543 | 0.760 | 0.861 |

| ANN4 | 0.517 | 0.559 | 0.764 | 0.840 |

| ANN5 | 0.519 | 0.548 | 0.770 | 0.789 |

| ANN6 | 0.519 | 0.528 | 0.769 | 0.800 |

| ANN7 | 0.535 | 0.390 | 0.771 | 0.760 |

| ANN8 | 0.521 | 0.541 | 0.765 | 0.820 |

| ANN9 | 0.524 | 0.500 | 0.777 | 0.749 |

| ANN10 | 0.527 | 0.458 | 0.784 | 0.654 |

| Mean | 0.524 | 0.499 | 0.771 | 0.777 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.006 | 0.054 | 0.007 | 0.062 |

| Neural Network | Modal A (Output: CTE) | Modal B (Output: SFT) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJ | PJ | IJ | DJ | PJ | IJ | CTE | |

| ANN1 | 0.329 | 0.338 | 0.333 | 0.260 | 0.251 | 0.215 | 0.275 |

| ANN2 | 0.377 | 0.313 | 0.310 | 0.285 | 0.192 | 0.222 | 0.301 |

| ANN3 | 0.379 | 0.350 | 0.271 | 0.300 | 0.170 | 0.155 | 0.375 |

| ANN4 | 0.416 | 0.317 | 0.267 | 0.299 | 0.240 | 0.175 | 0.287 |

| ANN5 | 0.364 | 0.293 | 0.343 | 0.357 | 0.171 | 0.142 | 0.329 |

| ANN6 | 0.377 | 0.304 | 0.319 | 0.299 | 0.205 | 0.186 | 0.310 |

| ANN7 | 0.384 | 0.287 | 0.329 | 0.287 | 0.229 | 0.181 | 0.303 |

| ANN8 | 0.364 | 0.325 | 0.311 | 0.292 | 0.177 | 0.239 | 0.291 |

| ANN9 | 0.386 | 0.318 | 0.295 | 0.295 | 0.202 | 0.116 | 0.387 |

| ANN10 | 0.348 | 0.343 | 0.309 | 0.314 | 0.195 | 0.151 | 0.340 |

| Average relative importance | 0.372 | 0.319 | 0.309 | 0.299 | 0.203 | 0.178 | 0.320 |

| Normalized relative importance | 100.0 | 85.6 | 82.9 | 93.4 | 63.5 | 55.7 | 100.0 |

| Path | Std.β | Normalized Relative Importance | Ranking (PLS-SEM) | Ranking (ANN) | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | |||||

| DJ→CTE | 0.391 | 100.0 | 1 | 1 | Consistent |

| PJ→CTE | 0.313 | 85.6 | 2 | 2 | Consistent |

| IJ→CTE | 0.272 | 82.9 | 3 | 3 | Consistent |

| Model B | |||||

| DJ→SFT | 0.323 | 93.4 | 2 | 2 | Consistent |

| PJ→SFT | 0.318 | 63.5 | 3 | 3 | Consistent |

| IJ→SFT | 0.208 | 55.7 | 4 | 4 | Consistent |

| CTE→SFT | 0.663 | 100.0 | 1 | 1 | Consistent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Yu, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Exploring Community Residents’ Intentions to Support for Tourism in China’s National Park: A Two-Stage Structural Equation Modeling–Artificial Neural Network Approach. Land 2025, 14, 2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112210

Liu Y, Yu P, Zhang X, Zhang X, Zhang Y. Exploring Community Residents’ Intentions to Support for Tourism in China’s National Park: A Two-Stage Structural Equation Modeling–Artificial Neural Network Approach. Land. 2025; 14(11):2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112210

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yantong, Pianpian Yu, Xianyi Zhang, Xinyao Zhang, and Yujun Zhang. 2025. "Exploring Community Residents’ Intentions to Support for Tourism in China’s National Park: A Two-Stage Structural Equation Modeling–Artificial Neural Network Approach" Land 14, no. 11: 2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112210

APA StyleLiu, Y., Yu, P., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Exploring Community Residents’ Intentions to Support for Tourism in China’s National Park: A Two-Stage Structural Equation Modeling–Artificial Neural Network Approach. Land, 14(11), 2210. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112210