Abstract

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate to what extent the ambiguity and excessive detail of the provisions of local spatial development plans (LSDPs) lead to an increase in investment risk and destabilization of the real estate market. The analysis was conducted based on a study of the content of selected LSDPs and their impact on property values and investment processes. The scope of the study includes the analysis of cases of municipalities (local administrative units) with a different approach to spatial planning as well as Polish regulations in the field of spatial planning. Case studies of cities and areas in which the adopted local plans had an impact on investment decisions and property values were taken into account. The conclusions from the analysis will be used to assess the effectiveness of the regulations used and to formulate recommendations regarding the optimization of the spatial planning in a way that enables the harmonious combination of the interests of investors, residents, and local government authorities.

1. Introduction

Local spatial development plans (LSDPs) are fundamental spatial policy instruments defining land use principles and the legal framework for investments. They enable effective spatial management, minimize conflicts, ensure coherent development, and create a basis for sustainable urban growth [1,2]. LSDPs define permissible land development for all market participants. Owners face restrictions that may increase land value but limit investment opportunities. Investors assess risk based on planning provisions (e.g., development intensity, infrastructure). Residents experience these decisions through their quality of life, access to public space, and built environment. LSDP research typically focuses on three areas: economic consequences of planning regulations, legal aspects of property rights, and social/urban outcomes. Diverse scholarly approaches create tensions between economic, urban, and legal perspectives. The literature highlights three main strands: (i) economic effects (land values, fiscal revenues, investment dynamics); (ii) legal implications (property rights, administrative procedures); and (iii) social/urban outcomes (housing affordability, gentrification). Restrictive provisions may increase land prices via scarcity but also raise investment risk. International and Polish cases confirm mixed consequences. This study contributes by systematically linking these effects with valuation evidence from four Polish case studies. The restrictiveness of LSDPs, expressed through intensity limits, biologically active area requirements, or prohibitions of certain functions, also raises fiscal questions. Piotrowska [3] showed that with a restrictive intensity index (≤0.4), predicted declines in property tax revenues reduce land value by an average of 15% within five years. Czekiel-Świtalska [4] demonstrated that extending the forecast horizon to 10 years overestimates expected revenue from planning fees by about 23%, softening the image of costs. On a national scale, Śleszyński et al. [5] estimated that lack of coupling with value capture tools generates a municipal deficit equal to 0.4% of GDP annually. By contrast, Botticini and Auzins [6] described an investment fee model recovering about 30% of lost revenues while stabilizing land prices. These findings illustrate how financial forecasts and value capture mechanisms shift risks between municipalities and investors, affecting project implementation. Without such feedback, no plan indicator can be reliably assessed in market terms.

Overly restrictive LSDPs often produce unintended economic effects. While designed to manage growth and prevent sprawl, they can distort housing supply, limiting access for younger households and raising prices, particularly in agglomerations with strong demand [7]. In the Polish context, Krajewska, Szopińska and Siemińska (2021) [8] found that restrictiveness in Kraków and Warsaw’s centers raised property values but constrained new commercial supply. This reflects the ongoing tension between urban planning, which seeks spatial order [1], and economics, which emphasizes investment freedom and transaction costs [9]. Legal aspects add further complexity: Rokicka-Murszewska (2019) [10] stressed that, as local law, LSDPs must comply with the Act on Spatial Planning and Development. Yet vague language, undefined concepts, and an over-delegation of interpretation often lead to disputes and lengthy administrative procedures.

Rigid plans also lack flexibility to adapt to changing conditions. Unlike Germany or the Netherlands, Poland’s system offers limited mechanisms for revising plans, reducing their long-term relevance. The OECD (2011) [11] emphasized that planning systems allowing dynamic revisions are more effective in urban management. Beyond economics and law, LSDPs have significant social effects. Balawejder et al. (2021) [12] noted that they may foster integration or trigger gentrification. In Warsaw’s Praga, restrictive provisions raised land values but displaced residents, while in Berlin and Amsterdam, strict rules reshaped social structures. Conversely, Lechowska [13] argued that restrictive standards can act as minimal guarantees of access to services and green space, while Drzazga [14] observed that “soft” guidelines are prone to negotiation, shifting risks to the private side. Empirical confirmation is provided by the analysis of Kantor-Pietraga et al. [15], who found that the introduction of a mandatory blue–green infrastructure index (hereinafter: BGI) of at least 30% of the investment area in the LSDP of Piekary Śląskie (in Poland) reduced the coefficient of variation in land prices from 0.28 to 0.22 (−21%) and shortened the average time of exposure of plots on the market from 22 to 14 months. Studies indicate that hard, enforceable BGI parameters reduce risk perception: investors lower the capitalization rate (in Piekary from 8.8% to 6%), which directly raises land valuations and accelerates the moment of construction commencement. Our own case studies confirm this relationship—plans equipped with mandatory BGI indicators show a lower risk discount and a shorter investment cycle compared to plans based solely on soft guidelines.

Planning regulations affect economic development, regional competitiveness, and market mechanisms. Well-designed LSDPs can increase investment attractiveness by providing legal predictability and regulatory stability. However, overly restrictive or ambiguous plans may increase investment costs and limit real estate supply, raising market prices [16]. An international example is Cambridge, UK, which illustrates both the advantages and negative effects of planning regulations. In the 1990s, this innovation center introduced restrictive LSDPs to protect suburban areas. As Cheshire and Sheppard (2002) [17] point out, these restrictions led to sharp price increases for commercial and residential properties, hindering local technology companies. Consequently, many firms relocated to areas with less restrictive regulations, such as Milton Keynes or Peterborough. In addition, private investors pointed to the high costs of adapting to planning requirements, leading to the abandonment of some projects [1]. Similar mechanisms exist in Poland. Kraków’s case shows that excessive restrictions in historical areas limit investment and cause economic problems through elevating project costs and subsequently limiting commercial and residential supply [18].

Miličić and Ćormić (2023) [19] analyzed 1314 transactions in 27 agricultural municipalities in Serbia, using a heteroscedastic hedonic model. The introduction in the LSDP of a requirement for a minimum plot front width increased by 20% compared to the median parceling raised the coefficient of price variation from 0.21 to 0.26, i.e., by 22%. This also reduced concluded contracts by one-third within two years. The authors interpret this as an increased entry barrier: small owners stop dividing land, and developers move projects to milder-regulation areas. Our eastern Greater Poland case studies reveal an analogous market reaction, confirming geometric restrictions can be a stronger risk determinant than distance from large labor markets.

The impact of the provisions of local spatial development plans on transaction prices should be fundamentally considered locally, as this is also the scope of these plans. The study [20] analyzed the impact of the provisions of a local plan (Policy-562—the Law of Heights) in the city of Bogotá on transaction prices. Among the recorded increases in property prices in the analyzed period, it was determined that the provisions of Policy-562 translated into this increase at the level of 15–33%. LSDPs affect not only economic and urban aspects but also cultural identity and residents’ quality of life. Properly designed plans can promote heritage preservation and social integration, while poor regulations may contribute to spatial conflicts and gentrification [12]. An example of negative effects is Warsaw’s Praga gentrification. New spatial regulations limited modernization without meeting rigorous conservation standards, increasing property prices and displacing existing residents for affluent groups. Consequently, the district’s social fabric transformed, forcing relocations [9]. Conversely, Copenhagen shows positive LSDP aspects on quality of life. Local plans ensure an even distribution of green areas, playgrounds, and social infrastructure, promoting social integration and improving residents’ quality of life [11].

Local spatial development plans are a key instrument for minimizing investment risk. As local law, they determine property purpose, development potential, and building parameters. An LSDP covering an investment area shortens building permit procedures by months, allowing investors to better estimate project costs and schedules. Hajduk and Baran (2013) [21] point out that numerous plans adopted after 2003 have excessive details, interfering with project documentation, limiting architectural flexibility, and generating adaptation costs. A different but equally problematic situation is created by the still-binding plans drawn up on the basis of the Act of 1994; due to the generality of the provisions and the lack of forecasts of financial effects, they increase the investment risk.

In Asian contexts, Zhou and Wang (2022) [22], using a set of over 220,000 Chinese transactions, show that in the quarter preceding the adoption of the local plan, land prices create a kind of “uncertainty bubble”: the spread between the 25th and 75th quantiles increases from about 7% to 18%. After the plan comes into force, the bubble bursts—within six months, the difference returns below 5%. A similar pattern was recorded by Gao and Deng (2021) [23] for Shenzhen—the announcement of the adoption of a new plan raised the standard deviation of prices by 9 percentage points, but after the final announcement, the price dispersion quickly fell to the value before the procedure. Both studies suggest price fluctuations are largely an artifact of the adoption stage—when restrictions become public—not the regulations’ content or planning system differences. In practice, clear consultation schedules and transparent communication can limit speculative price amplitude without changing the plan’s substantive parameters.

LSDPs are regulatory tools and mechanisms shaping urban/regional economic, social, and cultural structures. Proper plans can boost investment attractiveness, protect cultural heritage, and improve residents’ quality of life. However, examples (Cambridge, Kraków, Warsaw) show excessive restrictiveness can cause negative effects like increased property costs, limited housing, or gentrification. Thus, LSDPs require flexible, balanced design adapted to local socioeconomic realities for effective spatial management and urban development. The study [24] analyzed the abuse of municipal planning authority. Several rulings held that the Act on Spatial Planning and Development’s provisions do not grant primacy to public interest over individual interest. The Act’s solutions rest on balancing national, municipal, and individual interests. This mandates a careful balance between individual rights and the public interest, particularly during collisions.

The Provincial Administrative Court in Łódź judgment (II SA/Łd 528/05) used “circumventing the law” in the context of municipal planning. The court held that authorities using local plan prohibitions to obtain a specific legal effect (ceasing a negative environmental technology) that is identical to one that should result from a competent administrative body’s decision circumvents specific environmental laws. This also violates Article 6 of the Act on Municipal Self-Government (regarding the municipality’s scope). The line of reasoning of the court is reminiscent of the concept of abuse of procedure, which is more widely known in French law [25], and it is recognized when an authority chooses one procedure over another, whose conditions were not met, to gain benefits. Piotrowska (2017) [3] shows that forecasts prepared exclusively by planning departments underestimate future compensation costs by an average of 26%. This gap was revealed by a study by Hełdak et al. [26], which showed that an underestimated forecast promotes the creation of a planning vacuum in which investors maneuver between simplified procedures, while the municipality bears legal risk without controlling the actual development. In addition, the study [27] analyzed the potential costs associated with the construction of infrastructure as mentioned in the LSDP for a selected northern part of the city of Wrocław in Poland. The highest projected costs are estimated to be related to the purchase of land intended for the construction of public roads. A contrasting example is the Portuguese one described by Gorzym-Wilkowski and Trykacz [28]. There, mandatory forecast verification by an independent property appraiser shortened average compensation disputes from 30 to 14 months and reduced complaints by almost one-third. Analyses indicate that it is not the restrictions’ existence that matters but rather the entity and methodology for valuing effects: an expert forecast subjected to external audit minimizes local government financial risk and increases investor predictability.

The literature review reveals key tensions regarding LSDPs. Economists focus on land value and investment freedom, urban planners prioritize spatial order and quality of life, while legal practitioners analyze regulatory effectiveness and property rights. Despite extensive research, gaps remain, particularly the lack of clear methods for assessing LSDP effectiveness and insufficient research on their effects in smaller municipalities. LSDPs are not only a regulatory tool but also a mechanism shaping economic, social, and cultural structures. Well-designed plans can increase investment attractiveness, protect heritage, and improve quality of life. However, excessive restrictiveness may lead to unintended consequences such as higher costs, limited housing, and gentrification. The literature highlights the need for flexible, balanced, and context-sensitive LSDPs that integrate economic, legal, and social perspectives, ensuring both investment stability and sustainable spatial development.

2. Materials and Methods

The main goal of this paper is that the ambiguity and excessive detail of the provisions of local spatial development plans (LSDP) lead to an increase in investment risk and destabilization of the real estate market. Regulations that are either too general or too detailed limit the predictability of planning processes, which may result in a reduction in investment activity and an increase in the costs associated with adapting projects to the requirements of the LSDP. The analysis of cases of municipalities (local administrative units) with a different approach to spatial planning allows us to show to what extent the precision of regulations affects land value and investment mechanisms.

In order to verify the stated thesis, the following research questions have been formulated:

- 1.

- How does the ambiguity of LSDP provisions affect investment decisions and property valuation?

- 2.

- What mechanisms in the LSDP increase investment risk and what are their market consequences?

- 3.

- Are there legal and planning solutions that minimize the uncertainty resulting from LSDP regulations?

- 4.

- What are examples of the effects of incorrect interpretations of LSDPs in different cities and regions?

The analysis was carried out based on a study of the content of selected local spatial development plans (LSDPs) and their impact on property values and investment processes. The purpose of the study is to demonstrate to what extent the ambiguity of LSDP provisions, their excessive restrictiveness, or a lack of sufficient precision can limit spatial development and affect the investment decisions of economic entities and local governments.

The list of areas covered by the analysis are presented in Table 1 according to the LAU classification, the common classification of Territorial Units for Statistical Purposes [29], to facilitate their identification. The NUTS regulation mandates that NUTS 3 units may be subdivided into LAUs (municipalities). The degree of urbanization (DEGURBA) presented in the case studies is a classification that indicates the character of an area. It classifies the territory of a country on an urban–rural continuum. The DEGURBA metric combines population size and population density thresholds to establish three mutually exclusive classes: cities, towns and suburbs and rural areas. NUTS and LAU classification is provided to enhance the replicability of research findings and to allow for cross-referencing regions with various sources within these identification numbers.

Table 1.

Local administrative units of analyzed case studies.

Scope of Research and Case Studies

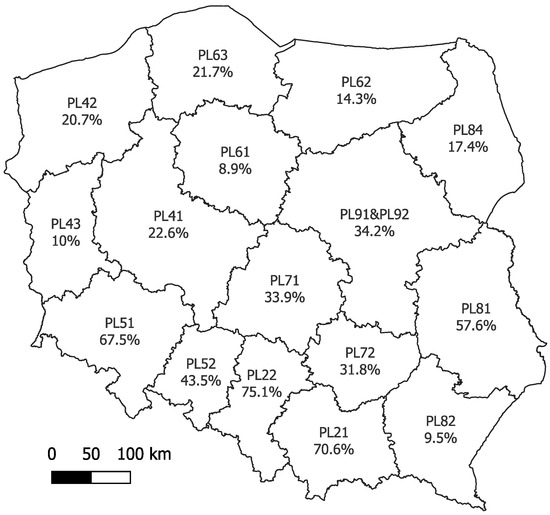

The scope of the study includes the analysis of selected local spatial development plans (LSDPs) and their impact on investment decisions and property values. Case studies of cities and areas in which planning regulations were of key importance for shaping the real estate market, as well as Polish regulations in the field of spatial planning, were taken into account. The coverage of Poland with binding local spatial development plans is illustrated in Figure 1. The graphic shows a very significant variation in coverage with local plans, which may translate into the investment attractiveness of regions in terms of the stability of local law. Detailed information on the number and area of local plans is presented in Table 2. The data were developed based on information contained in the Local Data Bank published by the Polish Central Statistical Office. The Local Data Bank (BDL) is the largest database in Poland on the economy, society, and environment. The first data come from 1995 [30]. Based on the analysis of the table, it can be observed that for areas with little coverage with local plans, the spatial policy of the municipality is implemented based on decisions on the conditions of development and land management.

Figure 1.

Coverage of local spatial development plans in force in Poland as for NUTS2 level (the codes in the figure represent the NUTS2 region classifications for Poland).

Table 2.

Coverage of local spatial development plans as of 2023.

The analysis of the content of the LSDP includes selected examples of provisions characterized by unclear, excessively restrictive, or overly detailed clauses. Particular attention was paid to regulations that directly affect the functioning of the real estate market and may be a source of investment uncertainty. The provisions regarding the purpose of the land will be analyzed, in particular those cases in which the lack of a clear definition of land functions leads to interpretation problems. One example may be a situation in which the plan defines a given area as “residential and service development area” without precisely defining the proportions between the two functions, which may lead to difficulties in estimating the potential value of the property.

Urban planning indicators, such as maximum development intensity, building height, and requirements for biologically active areas, are also an important issue. Restrictions on these aspects can significantly affect the profitability of investments and limit the possibilities of land development. Similarly, in the case of architectural regulations, excessively detailed requirements regarding the aesthetics of buildings may lead to an increase in project implementation costs. The provisions regarding access to technical infrastructure, which are crucial for investors planning development in a given area, will also be analyzed.

To assess the actual impact of the LSDP on the real estate market, we have conducted four unique case study analyses for areas where the adopted local plans had an impact on investment decisions in various urban planning contexts. Knowing that LSDPs can be very comprehensive in shaping spatial policies creates almost unlimited controversial examples. The analyzed case studies were selected from our practice due to their relevance, as they broadly illustrate the different scope of interaction between local spatial development plans and the real estate market such as value compensation conflicts and regulations outside the area of LSDPs, ambiguous conditions, unclear definitions, and infrastructure disconnects.

The conclusions from the analysis will be used to assess the effectiveness of the regulations used and to formulate recommendations regarding the optimization of spatial planning in a way that enables the harmonious combination of the interests of investors, residents, and local government authorities.

3. Case Study Analysis

In order to provide a coherent and analytically rigorous presentation, each case study is structured as a self-contained unit. This organization follows established methodological recommendations for empirical research in urban planning and real estate valuation, where contextual background and methodological assumptions must be presented together with their outcomes to ensure the traceability and reproducibility of results [31,32]. Accordingly, every case study is organized into three subsections: (i) background information and the relevant provisions of the LSDP, which establish the legal and planning framework; (ii) the methodological approach applied in the valuation experiment, including assumptions and adjustment procedures; and (iii) the valuation results and their interpretation, explicitly linking numerical outcomes with the identified planning restrictions. This integrated narrative avoids the earlier separation of descriptive and analytical components across different sections, which reviewers noted as impairing readability, and instead allows the reader to follow the complete causal chain in a single, continuous section: from the planning provisions, through their methodological treatment, to the resulting valuation effects. For appropriate clarity, the individual results of the case study analyses are contained within the following respective subsections. As of June 2025, the exchange rate of EUR/PLN was approx. 4.25.

3.1. Case Study 1—Valuation of the Real Estate for the Purpose of Determining the Compensation Due to Adoption or Amendment of the Local Spatial Development Plan in Miękinia, Poland

The case study we analyzed concerns a situation in which, due to the adoption of a local plan or its amendment, the use of the property or its part in the existing manner or in accordance with the existing purpose has become impossible or significantly limited. In this case, the property owner may demand compensation from the municipality for the actual damage incurred or the purchase of the property or its part.

The possibility of applying for compensation is not possible if the restriction is not the exclusive determination of the municipality but results, for example, from hydrological, geological, geomorphological, or natural conditions regarding the occurrence of floods and related restrictions, such as a building ban.

The fulfillment of claims for compensation or purchase may also take place by the municipality offering the property owner a replacement property.

If, in connection with the adoption of a local plan or its amendment, the value of the property has decreased, and the owner or perpetual leaseholder sells the property and has not exercised the rights referred to above, they may demand compensation from the municipality equal to the decrease in the value of the property.

The amount of compensation for the decrease in the value of the property is determined from the date of sale. The decrease in the value of the property is the difference between the value of the property determined taking into account the intended use of the land in force after the adoption or amendment of the local plan and its value determined taking into account the intended use of the land in force before the amendment of this plan or the actual method of use of the property before the adoption of this plan.

A claim related to the sale of real estate that has lost value can be reported within 5 years from the date on which the local plan or its amendment became binding.

The alienation of real estate that has undergone a reduction in value or has become less useful may, in extreme cases, be very difficult or even impossible due to a lack of buyer interest. However, to avoid losing the opportunity to apply for compensation related to the loss of value, transactions are sometimes concluded between related parties. From a legal perspective, such transactions are not prohibited and effectively interrupt the five-year period. Presumably, the legislator’s intention was not for owners to engage in sham transactions; however, documenting actual damage by owners is difficult, and it is easier to wait for an indication of the value difference from a court expert (expert witness) and perhaps challenge that difference.

The subject of the valuation was an undeveloped land property located in the Miękinia municipality with a total area of 81.2839 ha. According to the cadastral register (land and building register), the property is designated as arable land and pastures, although in reality it remains uncultivated.

The key points and timeline of this case study are as follows. In 2009, the entrepreneur obtained a license for aggregate extraction. In 2011, the municipality council adopted a local spatial development plan for the area [33]. In 2016, the property owner sold the property and filed a claim for compensation in connection with the decrease in property value as a result of the adoption of the local spatial development plan.

The acquisition of a license for aggregate extraction was possible, among other things, thanks to the decision obtained on environmental conditions for consent to the implementation of the project issued by the same municipality that later adopted the local plan.

In the next step, to allow exploitation, the entrepreneur had an approved mine operation plan, i.e., a study required by the Polish geological and mining law, whose operation plan regulates the conduct of mining activities in a specific area on this specific property.

Furthermore, the Polish Geological and Mining Law Act [34] in Article 7(2) states that in the absence of a local spatial development plan, undertaking and performing activities (mining) specified by law is permissible. In other words, the lack of a local plan does not automatically eliminate the possibility of mining development of the property.

The 2011 resolution of the municipality council regarding the adoption of the local spatial development plan states the following:

§ 11.1. Areas delineated by boundary lines, marked on the plan with symbols 1.PE and 2.PE, are designated for the following purposes:(1) Primary:(a) Areas for surface extraction of natural aggregate conducted by a mining enterprise based on granted concessions, according to relevant geological and mining law provisions.The local spatial development plan further stipulates the following:§ 11.5. The following principles for the modernization, expansion, and construction of communication systems are specified:(2) For freight transport related to the construction of the mining plant and loading port until the start of exploitation—through a network of access and internal roads connected to the district road (…),(3) For the transport of the exploited sand and gravel—through a network of access and internal roads within the area covered by the plan and further (after reloading)—using river or rail transport.

Given the facts and provisions analyzed above, article 7(2) of the Geological and Mining Law states that mining activities are permitted in the absence of a local spatial development plan; thus, the comparable properties used in the valuation, based on the state of the property before the enactment of the local spatial development plan, can include properties for which entrepreneurs have obtained mining concessions. However, it should be noted that a concession is issued to a specific economic entity and not to the property itself.

Therefore, to provide a comprehensive view of the situation, we estimated the value of the property three times:

- 1.

- According to the condition resulting from the documentation and the planning status before the adoption of the local spatial development plan.

- 2.

- According to the condition resulting from the documentation and in accordance with the restrictions resulting from the local plan in two variants:

- (a)

- Adjusting (extrapolating to zero) the user’s available deposit richness as an existing deposit but essentially inaccessible to the user.

- (b)

- Determining the value as agricultural land, since the enacted transport ban prevents the extraction of minerals.

The attributes of the subject property and six comparable sales used in the valuation are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Property attributes of comparable sales (marked as unique A–F letters) —case study no. 1.

Mineral property appraisal is considered a distinct valuation practice. Due to the high diversity of deposit types, minerals, extraction techniques, and the scarcity of real estate transactions associated with this variability, robust adjustments for comparable sales, as shown in Table 4, are feasible. This perspective is also reflected in [35,36].

Table 4.

Property adjustments of comparable sales (marked as unique A–F letters), PLN/ha—case study no. 1.

In Table 5, attributes such as the mineral resources and cadastral area are self-explanatory, but additional comments require information on the type of transaction and location. Comparable sales consist of properties that were purchased solely to expand adjacent mineral extraction or to establish a greenfield project. Regarding location, comparable sales were divided into two groups: a favorable location indicates that the property is situated within a county with low market competition, while an unfavorable location refers to areas where the market is highly competitive in terms of active mines (above the median of active mines).

Table 5.

Attributes and adjustment range for case study no. 1.

As for the justification of the assumption of limitation of transport, the provision (§11.5) explicitly restricted the transport of minerals by rail or river after reloading. At the time of adoption, no rail siding operated within feasible distance, and the Odra port required disproportionate investment. Therefore, road transport—the only practical option—was excluded. Infrastructure data (2015–2016) confirmed the absence of alternatives, validating the assumption of effective transport unavailability.

Attribute corrections were calculated by comparing the subject property with each comparable and scaling the difference proportionally to the predefined adjustment range (Table 5). For example, take Comparable A (minerals): the subject property had a mineral richness of 224 thousand tonnes per hectare, while Comparable A had 60. The maximum in the dataset was 228 and the minimum was 60. The adjustment range for this attribute was 41,489.92 PLN/ha. The difference between the subject and Comparable A () represents almost the full span of the dataset (168). Therefore, Comparable A required an upward correction of 41,027.18 PLN/ha. Adding the other adjustments (+20,367.78 PLN/ha for transaction type, and −9806.71 PLN/ha for location) gave a total correction of 74,580.33 PLN/ha. After applying this correction, the adjusted unit price of Comparable A amounted to 151,590.43 PLN/ha (see Table 4).

Results of Valuation Case Study No. 1

In case study no. 1—valuation of the undeveloped land property located in the Miękinia municipality with a total area of 81.2839 ha to determine compensation due to the adoption or amendment of the local spatial development plan, where the transport of extracted sand and gravel limitations were applied to provide a comprehensive view of the situation—we estimated the value of the property three times:

- 1.

- According to the condition resulting from the documentation and the planning status before the adoption of the local spatial development plan, resulting in a market value of MV1 = 13,896,000 PLN.

- 2.

- According to the condition resulting from the documentation and in accordance with the restrictions resulting from the local plan in two variants:

- (a)

- Adjusting (extrapolating to zero) the user’s available deposit richness, as an existing deposit but essentially inaccessible to the user, resulting in a market value of MV2a = 9,353,000 PLN.

- (b)

- Determining the value as agricultural land, since the enacted transport ban prevents the extraction of minerals, resulting in a market value of MV2b = 3,351,000 PLN.

The variant MV2a is a scenario where it is assumed that the deposit resources are inaccessible to the user, which is adjusted for by the “available richness” characteristic to a level of 0 (zero), indicating resources unavailable on the date for which the value is determined. This variant in the valuation is based on mining properties and considers the existence of the deposit as an integral part of the property.

The variant MV2b is an auxiliary scenario that reflects the economic effects of the provision with respect to the lack of transport possibilities, thus limiting the way property rights are exercised. A certain kind of “paralysis” or contradiction occurred here because the local plan, which makes provisions for areas l.PE, 2.PE—areas designated for the surface exploitation of natural aggregate deposits, and PO—areas intended for servicing the exploitation of natural aggregate deposits, does not foresee any other activities, such as agricultural. As a result of the transport restriction, the possibility of mining use was essentially excluded. This variant does not consider any value of the deposit, as the comparative transactions constituted large-area agricultural lands. According to the cadastral register (land and building register), the property was designated as arable land and pastures, although in reality it remained uncultivated. Because (as was also mentioned earlier) the land was not developed, it could easily technically be valued as agricultural land (as demonstration despite the LSDP zoning). Since this kind of valuation is obvious, it was not demonstrated as a separate valuation path. The transactional prices of four comparable sales were used for valuation: 49,968 PLN/ha, 39,927 PLN/ha, 43,554 PLN/ha, and 36,376 PLN/ha. The average adjusted price (value result) was 41,871 PLN/ha, which can be identified as stable according to comparable sales.

For a property with a designation related to the surface mining of a natural aggregate deposit in the case study Section 3.1, relating the values obtained from both variants to the baseline value before the amendment of the local plan (MV1), the variant with a reduction of available resources to zero (MV2a) due to the adoption of the local spatial development plan results in a 33% loss in the property value, while the valuation variant as agricultural land (MV2b) with complete omission of the deposit as a component results in a loss in value of 76%. These results are also presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Case study no. 1 results.

One must remember that the market value assessed by a property appraiser reflects the value as of the date specified in the appraisal report. The value of the property itself may change over time, depending on a number of factors related to the property itself, which are the so-called internal factors. In the case of a property with a deposit, these could include a reduction in the amount of overburden above the deposit or a more accurate recognition of the deposit, resulting in an increase in resources. External factors that may affect the level of property value include changes arising from excessive competition, market saturation, and alterations in nature protection regulations. It should be noted that according to the purpose of the valuation, any change in the value of the property as a result of the adoption or amendment of the local plan should be attributed to changes caused by that specific plan.

3.2. Case Study 2—Valuation of the Real Estate for the Purpose of Determining the Sale Price in Ząbkowice Śląskie, Poland

The subject of the valuation was an undeveloped land property located in the Ząbkowice Śląskie municipality, consisting of two cadastral plots with a total area of 76.2496 ha. The scope of the valuation included the right of perpetual usufruct of the subject property.

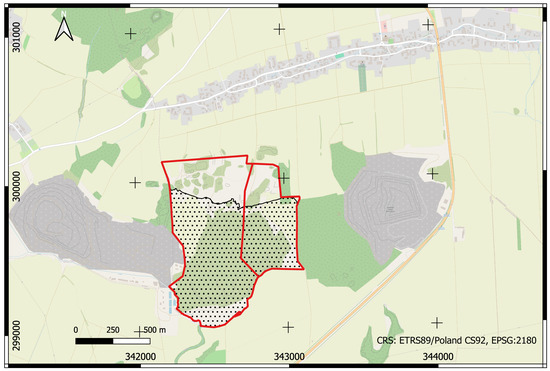

The location of the property (red color) in relation to the national road, mining excavations, and the village of Braszowice (to the north) is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Subject property (red outline) and the area of the terrain below the elevation of 340 m above sea level (dotted hatching).

We analyzed the local spatial development plan for this area. It was adopted in 2000; however, despite the adoption of the Act on Spatial Planning and Development in 2003, under transitional provisions, this plan, like others adopted after 1995, remains valid.

The subject of the plan’s provisions for the property is a functional area related to a municipal waste disposal and landfill facility. In addition to typical provisions regarding building parameters and communication services, the local plan, Resolution of the municipality Council of 2000 [37], includes two interesting provisions:

§ 15.3. The range of the municipality waste landfill on the north side cannot exceed the contour line that runs at an altitude of 340.0 m above sea level.

§ 17. The condition for the implementation of the utilization plant, which is the subject of this resolution, is to ensure the full connection of the residents to the existing water supply in the village of Braszowice and to eliminate all individual wells used for domestic purposes.

In the case of the first provision, we performed a spatial analysis of the course of the 340 m a.s.l. contour line with respect to the property boundaries using a digital terrain model and the QGIS 3.40.7 software. As a result of the analysis, we determined that due to this provision of the plan, the area suitable for the construction of the landfill constitutes 73% of the area of the plots, which is the area that we have shown with dotted hatching.

As also results from the provisions of the local spatial development plan, a condition for the implementation of the waste utilization plant is to ensure the full connection of residents to the existing water supply in the village of Braszowice (the village on the northeastern side in Figure 2) and to eliminate all individual wells used for domestic purposes.

As we can see, this provision refers to the conditions that must be met for the implementation of the waste utilization plant. It is worth noting that this determination concerns an event, the expression of consent of third parties to connect to the water supply. Moreover, the conditionality of this provision concerns conditions beyond the boundaries of the local spatial development plan.

Results of Valuation Case Study No. 2

Case study no 2. concerns the valuation of undeveloped land property located in the municipality of Ząbkowice Sląskie, with a total area of 76.2496 ha, to determine the sale price. In this circumstance, in order to allow the waste utilization plant, the local spatial development plan requires the full connection of residents from the nearby village to the existing water supply and the elimination of all individual wells used for domestic purposes.

The market value of the property was determined using a comparable sales approach without taking into account the elimination of all individual wells located nearby. Despite the attempt, no such provisions could be found in comparable transactions. In our opinion, such conditional provision should not necessarily be included in the local spatial development plan, but it should result from another decision obtained in the investment process, e.g., an environmental decision. Furthermore, the provisions that refer to areas outside the scope of the local plan raise questions from both a formal and a legal point of view. When the municipality adopts a resolution to begin the preparation of a local spatial development plan, it accurately defines the boundaries of the area for which these provisions will be created on a map through a graphic attachment. As mentioned, the implementation of a municipal waste landfill will be possible if all residents of the nearby village are connected to the water supply and individual intakes are eliminated, which might not materialize for an extended period of time, if at all. This risk could be attempted to be reflected in the income approach in the discount rate, but in the comparable sales approach, it was decided not to introduce adjustments for this reason due to the difficulty in quantifying this phenomenon that refers to the outside area of the LSDP and the lack of other transactions of this type. Alternatively, the investor could seek a formal repeal of the provision concerning the area beyond the spatial scope of the local plan; however, until the formal annulment of that part of the local plan, these provisions remain binding.

3.3. Case Study 3—Real Estate Analysis for Investment Process in Ozorzyce, Poland

To identify the background context of the Ozorzyce case, it must be read against the broader historical trajectory of Polish spatial planning after the 2003 Planning Act. In many municipalities, local plans were drafted with highly generalized clauses, which are often shaped by social pressure to preserve agricultural landscapes and by environmental concerns linked to soil protection. However, these clauses were frequently disconnected from the realities of investment practice and market demand. In the case of Ozorzyce, the vague provision of “agricultural production” illustrates how an attempt to balance environmental protection with development potential generated interpretative uncertainty for both investors and appraisers. In legal doctrine and the spatial planning literature, it is widely emphasized that the designation of a property’s function in the local spatial development plan (LSDP) is one of the most significant determinants of land market value. Specifically, determining the intended use—whether residential, commercial, industrial, or agricultural—directly translates into development possibilities, investment profitability, and the scope of potential administrative restrictions. The legal importance of this competence of municipal bodies is crucial, since the LSDP, as a local act of law, binds property owners and investors and sets the framework for permissible spatial development. The case concerns a property located in Ozorzyce in the Siechnice municipality (Wrocław district). According to the LSDP, the land was classified as 8RPO—agricultural production area. The plan stipulates that “agricultural production should not cause nuisances beyond the property boundaries” and simultaneously prohibits “the location of service and production facilities that negatively impact the environment.” However, the plan does not provide a precise definition of “agricultural production” nor does it specify the criteria for determining nuisances “extending beyond the property boundaries.” Such wording raises doubts as to whether activities such as establishing a horse stud farm can be regarded as agricultural production. Although jurisprudence and statutory definitions often include stud farms within agricultural activity, the absence of an explicit definition in the LSDP created interpretative uncertainty. To clarify this, the investor formally requested an interpretation of the provision from the competent municipal authority. This initiated an internal and external consultation procedure within the office, which was intended to provide a written clarification of the plan. The consultation process lasted more than two months. The municipal authority was unable to clearly define the scope of the disputed provision. In its written reply, the office indicated that the final decision on whether the planned investment could be implemented would ultimately be taken by the architectural and construction administration authority during the assessment of the building permit application. Consequently, despite the request for clarification, the ambiguity of the provision remained unresolved, leading to the extension of the preparatory stage and an increase in procedural costs.

Results of Investment Analysis of Case Study No. 3

Our analysis of Ozorzyce case study no 3. illustrates how significantly imprecise language in a planning act affects the prolongation of the investment process, the increase in preparatory costs, and the disintegration of predictions regarding the market value of the property.

From the perspective of a property appraiser and the analysis of the market value of the property, such a state of affairs generates additional uncertainty, resulting in the need to apply a higher discount rate or to lower the offer price due to legal and investment risks. The unclear assignment of a functional use in the LSDP leads, in practice, to a situation in which potential buyers or investors withhold their purchase decision, fearing negative administrative consequences or the need for lengthy enforcement of the right to develop.

The Ozorzyce case therefore proves that the designation of a property in the LSDP cannot be treated only as technical planning information but rather as a fundamental legal and economic premise that determines the possibility of real use of the land. Any imprecise, non-operational formulation results not only in difficulties in the investment process but also in a disruption of valuation mechanisms, which should be based on clear, unambiguous and feasible planning premises.

3.4. Case Study 4—Real Estate Analysis for Investment Process in Międzyrzecz, Poland

To identify the background context of the Międzyrzecz case, it should be noted that it reflects a recurrent paradox in Polish planning practice: formally pro-investment zoning designations were introduced in areas where infrastructure capacity lagged behind regulatory intentions. This disconnection stems from the legacy of the 1990s and early 2000s, when rapid socio-economic transformation outpaced technical infrastructure development, especially in smaller municipalities. In Międzyrzecz, the absence of a feasible water supply connection was not merely a technical issue but the outcome of long-term underinvestment in utilities. As a result, the positive economic designation in the plan was undermined by unresolved infrastructural and institutional constraints.

In the literature on the subject, it is emphasized that properly designed provisions of the local spatial development plan (LSDP) should correspond not only to the intended functional and spatial structure of an area but also to the actual level of available technical infrastructure. A mismatch between planning provisions and infrastructure capacity may significantly increase investment risk. The case analyzed refers to an investment planned in the Międzyrzecz municipality. The LSDP designated the area for economic activity, including storage, warehousing, and small-scale production. The plan explicitly required water supply from the municipal network while at the same time allowing for temporary provision from an individual intake. In accordance with these provisions, the investor submitted an application to the municipal water supply company for a network connection. To fulfill the requirements, the investor declared readiness to finance and construct a 650 m extension of the water main and to transfer this infrastructure to the municipality free of charge. Despite compliance with the provisions of the LSDP, the investor was refused connection to the municipal water network. The justification indicated that the refusal did not result from the absence of a formal connection point but rather from the technical inefficiency of the main, which was unable to serve the planned development. Although the expansion of the water network was included in the company’s plans, no binding schedule for its implementation was available due to the complexity of procedures and the lack of investment decisions. As a result, further design work was discontinued and the investment project was abandoned, while the costs incurred in preparation remained unrecoverable.

Results of Investment Analysis of Case Study No. 4

Our analysis shows that the situation in Międzyrzecz led to a complete abandonment of further design work and a resignation from the investment. Despite favorable planning designation and convenient location, land with high development potential was considered “noninvestment”—solely due to the inconsistency between the provisions of the LSDP and the actual state of technical infrastructure. For investors, this resulted not only in direct losses associated with the costs incurred in preparing the investment but also in a loss of confidence in the stability and credibility of the spatial planning system as a tool for predictably shaping investment decisions.

From a theoretical perspective, this case fits into a broader discourse on the role of the LSDP as a tool for determining land value and as a source of investment risk. The lack of support for planning designations not only devalues the formal provisions of the plan but also directly impacts the ability to accurately estimate the value of the property. This exemplifies a classic mismatch between planning policy and market logic.

4. Discussion

This paper critically examines the significant impact of local spatial development plans (LSDPs) on the real estate market and investment climate in Poland and provides evidence that ambiguous or overly restrictive LSDP provisions directly distort property values. The impact of local spatial development plans on the value of the property and the investment process is local due to the specificity of the real estate. However, referring to the research questions posed earlier in Section 2, it should be stated that the ambiguity of local plans can affect the value of real estate, as demonstrated as a percentage of value loss in case study no 1. Meanwhile, case study no 2. shows that the external conditionality linked to third-party consent (individual wells closure) is very unusual and has an impact that is difficult to quantify. Case study no 3. revealed that ambiguous definitions can increase capitalization rates by 1 to 1.5 p.p., lowering the property value. Last, case study no 4. illustrated that the absence of technical feasibility (water supply) nullified the added value of favorable zoning. The analysis reveals a fundamental tension between the objectives of spatial regulations, economic development, and the protection of property rights. The findings indicate that the ambiguity, excessive detail, and inflexibility of many LSDPs are primary sources of investment risk, market destabilization, and social tensions.

Regarding research question no. 1, How does the ambiguity of LSDP provisions affect investment decisions and property valuation?, the core finding of this research is that the lack of clarity and predictability in LSDPs creates substantial uncertainty for all market participants. The study demonstrates that overly restrictive planning regulations, while sometimes increasing property values, often do so by creating artificial scarcity rather than improving the quality of the built environment. This can have severe negative consequences, including driving out innovative businesses, as seen in the case of Cambridge [17], and creating barriers to housing for less affluent populations.

Our case study from Ozorzyce demonstrates how an imprecise wording of plan provisions prolongs the investment process and generates additional costs. This finding is consistent with observations of Rokicka-Murszewska [10] who underlined that vague legal formulations increase the number of disputes and administrative delays.

Regarding research question no. 2, What mechanisms in the LSDP increase investment risk and what are their market consequences?, this research highlights the procedural and legal shortcomings in the current system. Vague language and the absence of clear definitions within the plans frequently lead to prolonged legal disputes and administrative delays. The “uncertainty bubble” observed in land prices just before a plan’s adoption underscores the market’s sensitivity to the planning process itself, suggesting that transparent communication and clear timelines are as crucial as the content of the regulations. The study also points to the troubling issue of municipalities potentially using planning authority to circumvent other environmental or administrative laws, which is an action that a Polish court has identified as a “circumvention of the law”.

Similarly, our analysis of many LSDPs as in Hajduk and Baran [21] confirms that local spatial development plans after 2003 are characterized by excessive details, making it almost impossible to adjust comparable sales for differences while performing a valuation of real estate.

The Międzyrzecz case study highlights the risks caused by discrepancies between planning provisions and the actual state of infrastructure. Although the LSDP allowed temporary water supply solutions, the lack of technical feasibility prevented the investment. This confirms earlier conclusions by Hajduk and Baran (2013) [21], who showed that plans often interfere excessively with project documentation, ignoring technical realities. Moreover, our findings resonate with Krajewska, Szopińska and Siemińska [8], who argued that overly restrictive or unrealistic planning provisions in Polish cities raised land values while at the same time constraining new supply. In Międzyrzecz, instead of higher value, the result was the opposite—the land was effectively excluded from development.

Regarding research question no. 3, Are there legal and planning solutions that minimize the uncertainty resulting from LSDP regulations?, this paper provides evidence that well-designed planning can yield positive outcomes. The mandatory inclusion of quantifiable standards, such as the blue–green infrastructure index (BGI) in Piekary Śląskie, was shown to reduce price volatility, lower investment risk, and shorten the time that properties spent on the market. This suggests that clear and enforceable standards can provide the confidence investors seek, ultimately leading to more sustainable and higher quality development.

From the standpoint of real estate market participants and property appraisers alike, it is well established that the designated use of a property within the local spatial development plan can exert a significant influence on its value. This is because local spatial development plans, in conjunction with other pertinent regulations, define the permissible use of the property. As local spatial development plans constitute acts of local law, they are subject to strict adherence. Notwithstanding that a particular provision of a local plan may appear deficient, it is only through its formal revocation, executed via the appropriate procedure, that noncompliance is permissible. Until such a provision is formally repealed, it remains legally binding.

Regarding research question no. 4, What are examples of the effects of incorrect interpretations of LSDPs in different cities and regions?, the Ozorzyce and Międzyrzecz cases exemplify the long-term consequences of ambiguous or impractical planning provisions. They mirror findings from Krajewska, Szopińska and Siemińska [8], who showed that in Kraków and Warsaw, restrictive provisions increased values but limited supply. At the same time, they diverge from the positive examples highlighted by the OECD [11], where flexible systems (e.g., Germany, the Netherlands) allowed dynamic revisions and adaptation to infrastructure. Similarly, while Cheshire and Sheppard [17], as well as Glaeser and Ward [38], demonstrated that restrictive planning can artificially raise property prices, our case studies illustrate another trajectory: uncertainty and infrastructural contradictions may not increase values but instead discourage investment entirely.

Currently, the practice of adopting large-scale LSDPs with multiple land use designations has been largely abandoned. The “rationale” is that the enactment process for such comprehensive plans, complicated by numerous zones of influence, makes their rational design and subsequent legal adoption extremely time consuming. Furthermore, amending such a plan is very difficult, as the law stipulates that local plans must be changed using the same full procedure required for their initial enactment. To circumvent this regulation, local administrative units create a mosaic of new, smaller-area plans in place of existing ones, which causes the previous large plan to lose its validity within the specific area covered by the new, smaller plan, with other provisions and designations of the larger plan being untouched. This often can lead to spatial chaos, as small-scale LSDPs may not follow the pattern of larger-scale local spatial development plans.

The findings have significant implications for Polish policy makers and planning practitioners. There is a clear need to reform the legislative framework to promote greater flexibility, clarity, and predictability in spatial planning. Three takeaway points from this research are as follows:

- LSDPs must move away from excessive detail and ambiguity. Regulations should be clear, concise, and focused on essential outcomes, providing a stable but adaptable framework for investment. Adopting practices from countries like Germany and the Netherlands, which utilize more dynamic and flexible planning revision mechanisms, could be beneficial.

- The current lack of a precise, independent analysis of the financial consequences of LSDPs is a major flaw. As the research shows, forecasts prepared solely by planning departments often underestimate costs, creating a “planning vacuum”. Implementing a mandatory, independent verification of financial forecasts, similar to the Portuguese model, could reduce disputes and increase the reliability of the plans as market-shaping tools.

- The principle of balancing the interests of the municipality and individuals must be actively upheld in practice to prevent any abuse of planning authority.

Future research should focus on developing standardized methods for assessing the economic and social impacts of LSDPs in a wider and more diverse range of municipalities. Local policies might be aggregated, and their impact on the real estate market should be monitored.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Methodology, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Validation, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Formal analysis, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Investigation, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Resources, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Data curation, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Writing—original draft, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Writing—review & editing, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Visualization, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Supervision, M.D. and A.N.-Ś.; Project administration, M.D.; Funding acquisition, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC was funded by a subsidy for the year 2025 of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education executed at the Wrocław University of Science and Technology.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LSDP | local spatial development plan |

| DEGURBA | degree of urbanization |

| NUTS | Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics, abbreviated NUTS (from the French version Nomenclature des Unités territoriales statistiques), is a geographical nomenclature subdividing the economic territory of the European Union into regions at three different levels (NUTS 1, 2 and 3, respectively, moving from larger to smaller territorial units). |

References

- Alterman, R. 755 Land-Use Regulations and Property Values: The “Windfalls Capture” Idea Revisited. In The Oxford Handbook of Urban Economics and Planning; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolka, M.O. Implementing Value Capture in Latin America: Policies and Tools for Urban Development; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska, L. Okres prognozowania skutków finansowych uchwalenia miejscowego planu zagospodarowania przestrzennego. Przestrz. Ekon. SpołEczeńStwo 2017, 12, 263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Czekiel-Świtalska, E. Prognoza skutków finansowych uchwalenia miejscowego planu zagospodarowania przestrzennego a budżet gminy. Przestrz. Forma 2013, 19, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P.; Nowak, M.; Sudra, P.; Załęczna, M.; Blaszke, M. Economic consequences of adopting local spatial development plans for the spatial management system: The case of Poland. Land 2021, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botticini, F.; Auzins, A.; Lacoere, P.; Lewis, O.; Tiboni, M. Land Take and Value Capture: Towards More Efficient Land Use. Sustainability 2022, 14, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandwa, B.; Ogura, L. Local urban growth controls and regional economic growth. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2013, 51, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, M.; Szopińska, K.; Siemińska, E. Value of land properties in the context of planning conditions risk on the example of the suburban zone of a Polish city. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimmer, F.; McCluskey, W.J. Property taxation for developing economies. Fig Comm.—Valuat. Manag. Real Estate 2016, 67, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rokicka-Murszewska, K. Administracyjnoprawne Aspekty Opłaty Planistycznej; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika: Toruń, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The Governance of Land Use in OECD Countries: Policy Analysis and Recommendations; OECD: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Balawejder, M.; Kolodiy, P.; Kuśnierz, K.; Sebzda, J. Analysis of local spatial development plans for the smart city of Rzeszow (Poland). Gis Odyssey J. 2021, 1, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechowska, E. Planowanie Przestrzenne na Poziomie Lokalnym: Powiązanie Teorii z Praktyką; Polska Akademia Nauk, Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Drzazga, D. Systemowe Uwarunkowania Planowania Przestrzennego Jako Instrumentu Osiągania Sustensywnego Rozwoju; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu ódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Zdyrko-Bednarczyk, A.; Bednarczyk, J. Importance of Blue–Green Infrastructure in the Spatial Development of Post-Industrial and Post-Mining Areas: The Case of Piekary Śląskie, Poland. Land 2025, 14, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G.E. Unlocking Land Values to Finance Urban Infrastructure; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, P.; Sheppard, S. The welfare economics of land use planning. J. Urban Econ. 2002, 52, 242–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, M.; Źróbek, S.; Kovač, M.Š. The role of spatial planning in the investment process in Poland and Slovenia. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2014, 22, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duolaiti, X.; Kasimu, A.; Reheman, R.; Aizizi, Y.; Wei, B. Assessment of Water Yield and Water Purification Services in the Arid Zone of Northwest China: The Case of the Ebinur Lake Basin. Land 2023, 12, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago-Mora, D.; Àngel Garcia-López, M. Real estate prices and land use regulations: Evidence from the Law of Heights in Bogotá. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2023, 101, 103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, S.; Baran, A. Planowanie przestrzenne gmin a proces inwestycyjny–zagadnienia problematyczne. Optimum. Studia Ekon. 2013, 62, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cai, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S. Analysis of the Working Response Mechanism of Wrapped Face Reinforced Soil Retaining Wall under Strong Vibration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Gallagher, L.; Min, Q. Examining Linkages among Livelihood Strategies, Ecosystem Services, and Social Well-Being to Improve National Park Management. Land 2021, 10, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchomiuk, J. Abuse of the Municipality’s Planning Authority. Samorz. Teryt. 2014, 4, 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Auby, J.M. The Abuse of Power in French Administrative Law. Am. J. Comp. Law 1970, 18, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hełdak, M.; Ogórka, K.; Raszka, B. Legal Loopholes and Investment Pressure in the Development of Individual Recreational Buildings in Protected Landscapes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hełdak, M.; Płuciennik, M. Ekonomiczne aspekty decyzji planistycznych na przykładzie miasta Wrocławia. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. WrocłAwiu 2018, 504, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gorzym-Wilkowski, W.A.; Trykacz, K. Public Interest in Spatial Planning Systems in Poland and Portugal. Land 2022, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/2066 of 21 November 2016 Amending the Annexes to Regulation (EC) No 1059/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Establishment of a Common Classification of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS), C/2016/7380, OJ L 322, 29.11.2016. pp. 1–61. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/2066/oj/eng (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- GUS—Bank Danych Lokalnych. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/start (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications; Sage Thousand: Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miękinia, R.G. Uchwała Rady Gminy Miękinia nr V/41/11 z Dnia 25 Marca 2011 r. (Dz. Urz. Woj. Dolnośląskiego z 2011 r. Nr 89, poz. 1407). Available online: https://edzienniki.duw.pl/WDU_D/2011/89/1407/Akt.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- ACT of 9 June 2011 Geological and Mining Law, Journal of Laws of 2011, No. 163, Item 981. Available online: https://rmis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/uploads/legislation/POLAND_Geological&MiningAct.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Ellis, T.R. Sales comparison valuation of development and operating stage mineral properties. Min. Eng. 2011, 63, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rudenno, V. The Mining Valuation Handbook 4e: Mining and Energy Valuation for Investors and Management; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Uchwała Nr X/66/2000 Rady Miejskiej w Ząbkowicach Śląskich z dnia 24 Listopada 2000 roku w Sprawie Zmiany Miejscowego Planu ogóLnego Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Gminy Ząbkowice Śląskie; Rady Miejskiej w Ząbkowicach Śląskich: Ząbkowicach Śląskich, Poland, 2000.

- Glaeser, E.L.; Ward, B.A. The causes and consequences of land use regulation: Evidence from Greater Boston. J. Urban Econ. 2009, 65, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).