1. Introduction

Rural regions around the world face mounting challenges including population decline, underutilized infrastructure, and economic stagnation [

1]. In many communities, schools, factories, and homes lie abandoned, visible reminders of structural change and urban migration. At the same time, tourism is increasingly viewed as a tool for rural revitalization, offering pathways for economic diversification, cultural preservation, attraction of the relational population, and community resilience [

2,

3,

4]. However, traditional tourism development often prioritizes new construction, large-scale investment, and external ownership, raising concerns about environmental degradation, cultural dilution, and community exclusion [

5,

6]. This is particularly evident in rural tourism, which is defined as tourism that takes place in non-urban areas, offering visitors experiences related to natural environments, agricultural practices, and the cultural and social life of rural communities [

7].

Amid these concerns, the concept of the circular economy has emerged as a promising framework for rethinking how tourism can be developed more sustainably [

8]. By prioritizing the reuse of existing resources, minimizing waste, and creating regenerative systems, circular economy principles offer a pathway to low-impact, community-centered tourism [

4]. One particularly relevant strategy within this framework is adaptive reuse, which is the repurposing of abandoned or underused buildings for new tourism-related functions [

9,

10]. This approach not only extends the life cycle of built environments but also contributes to sustainable land use and the conservation of cultural landscapes [

11,

12].

Tourism cooperatives are community-based, democratically governed organizations that can play a critical role in facilitating such transformations [

13]. Their embeddedness in local contexts allows them to mobilize community participation, align development with local values, and reinvest resources into socially and ecologically beneficial projects. Beyond their social and environmental contributions, tourism cooperatives also generate economic significance through the creation of value loops, locally generated economic benefits such as profits from tourism services, sales of local products, and reinvestment in infrastructure, that are deliberately recirculated within the community rather than leaking to external actors. Yet, the role of tourism cooperatives in enabling circular land use practices, such as the adaptive reuse of abandoned buildings, remains underexplored in both tourism and rural development literature.

This study explores how tourism cooperatives can function as effective governance models for advancing circular economy principles through a comparative analysis of two distinct cases in rural communities in South Korea, seeking to identify commonalities and contextual differences in their implementation strategies. Specifically, this study focuses on how these cooperatives repurpose abandoned buildings, such as homes and a multi-purpose community center, into guesthouses, retail shops, museums, and multi-use facilities to promote sustainable and community-driven development. Through a circular economy lens, this study analyzes how such transformations promote sustainable land use, enhance ecosystem services, and strengthen community interactions. Using a case study approach, this research further examines how tourism cooperatives function as integrative mechanisms that foster resilient, economically inclusive, and community-driven models of rural tourism development. To explore this phenomenon, the study is guided by the following research questions:

Research Question 1: What forms of adaptive reuse and asset recirculation strategies are adopted by tourism cooperatives in rural communities in South Korea to advance circular economy principles?

Research Question 2: How does the cooperative governance model facilitate the selection, financing, and management of adaptive reuse projects that promote circular economy principles within the local community?

Research Question 3: How do the adaptive reuse projects and circular economy initiatives contribute to the creation and local recirculation of perceived economic value within the community?

Research Question 4: What are the key similarities and differences between the two tourism cooperatives regarding the governance mechanisms and the challenges faced in maintaining the economic viability of community tourism assets derived from their adaptive reuse initiatives?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the theoretical foundations and key literature on regenerative and circular approaches, adaptive reuse, and cooperative-led development in tourism.

Section 3 details the materials and methods.

Section 4 presents the results from the two case studies.

Section 5 discusses the key findings, and

Section 6 concludes with the theoretical contributions and practical implications for sustainable tourism and rural revitalization.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative case study approach, which is particularly suited to exploring complex phenomena within their real-life contexts [

38,

39]. The case approach based on the comparative method enables an in-depth examination of tourism cooperatives, focusing on the processes, practices, and outcomes associated with adaptive reuse initiatives implemented by these organizations [

40]. According to the principles of qualitative scientific inquiry, where rigor is established through depth, contextual understanding, and analytical generalization [

38,

41], this study aims to explore and interpret how tourism cooperatives have successfully implemented adaptive reuse strategies in rural contexts. Understanding successful cases of circular economy practices across diverse contexts is essential for advancing the theory, as these cases provide a broader conceptual foundation and help identify potential factors or hypotheses that can later be tested.

South Korea was chosen as the study context because it has been gaining international recognition for promoting responsible and sustainable tourism practices [

42,

43]. The number of cooperatives in South Korea has grown rapidly since the enactment of the Framework Act on Cooperatives in 2012, which lowered the barriers to cooperative formation [

44]. As of the end of 2022, a total of 23,892 cooperatives were registered nationwide, of which 10,976 (45.9%) were actively operating [

45]. The majority of active cooperatives (10,976) are general cooperatives (8362; 76.2%), followed by social cooperatives (2566; 23.4%) and federations (48; 0.4%). General cooperatives are further classified into four types: business cooperatives (54.5%), multi-stakeholder cooperatives (16.5%), employee cooperatives (2.9%), and consumer cooperatives (2.3%) [

46]. Although all cooperatives in South Korea must be officially registered, there is no specific registration category for tourism cooperatives, making it difficult to classify and identify them. Tourism cooperatives are categorized as such when their primary business activities and main areas of operation are related to tourism [

44].

3.1. Case Selection

The case studies were selected using purposive sampling, complemented by snowball referrals, to identify cooperatives that had successfully implemented adaptive reuse projects relevant to the study’s objectives. The selection was guided by the goal of gaining in-depth insights into how cooperative governance models advance circular economy principles. Two distinct tourism cooperatives, the Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative in Gangwon-do and the Sehwa Village Cooperative in Jeju-do, were selected as instrumental cases to provide a focused understanding of these dynamics [

39].

The two cases represent distinct yet complementary examples of tourism cooperatives engaging in adaptive reuse within different regional and organizational contexts. As shown in

Table 1, Case 1 (Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative), established in April 2020, is a small business cooperative located in a mountain village and a former mining town. It is characterized by its intimate organizational structure and small membership (12 members), its community-driven approach to rural revitalization through rural tourism and small-scale entrepreneurship. In contrast, Case 2 (Sehwa Village Cooperative), founded in October 2019, operates as a business cooperative in a seaside village characterized by traditional agriculture and fishing, with a substantially larger membership (494), which reflects a broader governance base and more complex coordination among local stakeholders. These contrasting characteristics, particularly regarding setting, scale, and community context, enabled a valuable comparative analysis to examine how different cooperative structures implement adaptive reuse strategies to support sustainable rural development within the framework of circular economy principles.

3.2. Data Collection

Data was collected through a multi-method approach that combined in-depth interviews (guided conversations) with key informants from each cooperative, direct observations during field visits, and documentary content analysis [

38]. Fieldwork for direct observations was conducted between 17 June and 22 June 2024, during a period when both cooperatives operated under regular, non-holiday conditions. This timing allowed observation of routine practices rather than peak-season or festival-related activities. The schedule also aligned with key informant availability and provided opportunities to observe the repurposed facilities in active use. The onsite engagement included in-depth interviews with cooperative representatives to gain contextual understanding of organizational structures, community tourism initiatives, sustainable and responsible tourism practices, and perceived challenges and impacts. Each interview lasted approximately 100 min and was conducted face-to-face at the cooperative’s office, recorded with consent, and transcribed verbatim. As part of direct observations, researchers spent one or more nights in each community and joined local tours before or after the meetings, facilitating immersion in the cooperative’s operational and social environment.

Table 2 summarizes key details of the two study cases.

In addition, naturalistic and direct observational fieldwork was conducted during regular operations of each cooperative. Because the original (pre-reuse) structures were no longer directly observable, observations focused on the current use and management of the adaptively reused sites. Researchers documented how renovated buildings and facilities were integrated into community tourism activities. For the documentary component, we reviewed each cooperative’s website, social media accounts, news articles, and community publications detailing the cooperatives’ origins, local development initiatives, and historical transitions, which were triangulated with field direct observations and informant interview narratives during content analysis.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the findings, several strategies for methodological rigor were employed. Triangulation was achieved by integrating data from multiple sources, such as informant accounts, field observations, and documentary materials, to corroborate the findings [

38,

39]. Prolonged engagement in the field enabled researchers to gain contextual familiarity and verify interpretations through direct observation. Additionally, peer debriefing and iterative cross-checking between researchers were used to minimize bias and confirm consistency in interpretation. These procedures strengthened the overall credibility and trustworthiness of the analysis.

3.3. Case Descriptions

3.3.1. Geographical and Historical Background of Case 1

Case 1, the Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative, is located in Gohan-eup

1, Jeongseon County, Gangwon Province, South Korea. Gohan-eup encompasses approximately 52.34 km

2 with a population of about 4275 residents, including both Korean nationals and foreigners [

47]. It is a typical mountainous area, with over 85% of its total area located at elevations above 700 m, leaving very little usable land [

48]. Although the official name Gohan-eup has only been used since 1985, the area has a history of over 1400 years. Until the early 1950s, it was a quiet mountain village of about 780 households, where farmers mainly engaged in dry-field cultivation and the gathering of forest products. With the 1962 enactment of the Temporary Measures Act on Coal Mine Development, large mining companies moved in, attracting people from across the country and transforming the village into a mining town.

Figure 1 depicts Gohan in the early 1960s.

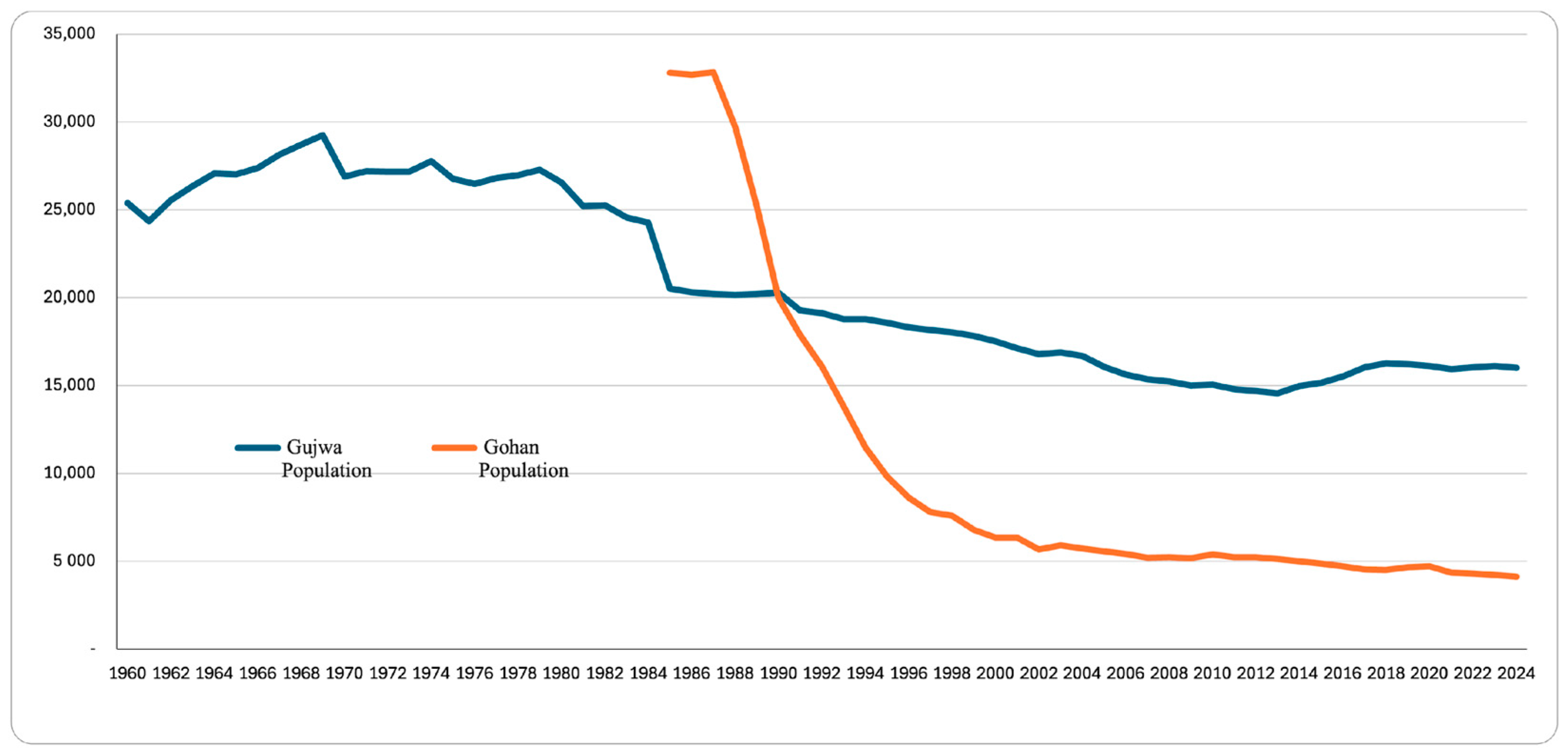

Fueled by rapid coal mining development, Gohan-eup’s population reached 32,801 in 1985, establishing it as a booming mining town. However, the community entered a steep decline beginning in 1990 when the Coal Industry Rationalization Policy led to successive mine closures (

Figure 2). At its peak, more than 20 mines produced 15% of the nation’s anthracite output, but with the final closures in 2001, the town faced severe economic downturn and significant population decline [

48]. At the Jeongseon County level, large-scale tourism infrastructure projects, Kangwon Land Casino and Hotel and the High One Ski Resort, were developed to stimulate economic revitalization and attract visitors. Both of which are located in neighboring villages.

3.3.2. Overview of the Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative (Case 1)

Case 1, the Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative, was founded in April 2020 to revitalize the local village economy. While its initial focus centered on community revitalization, the cooperative’s goals continue to evolve in response to emerging opportunities and challenges. With 12 members, the cooperative operates on a smaller scale but fosters close-knit collaboration among its members and partners. Key partnerships include the local government, small business groups within the village, and local museums and attractions, creating synergies that enhance tourism potential and economic activity. The cooperative received a grant to initiate operations, along with funding to support two staff positions for the first two years. These resources have been instrumental in launching income-generating activities and establishing the cooperative as a driver of community-led tourism development in the region.

3.3.3. Geographical and Historical Background of Case 2

Case 2, the Sehwa Village Cooperative, is located in Sehwa-ri

2, Gujwa-eup, Jeju City, South Korea. Sehwa-ri is a coastal village, renowned for its scenic landscapes and cultural heritage. The village overlooks Sehwa Beach, known for its white sandy shores and striking black basalt formations set against emerald waters [

50]. Jeju-do, the island on which the village is located, has been designated as both a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Sehwa boasts a diverse range of natural resources, including Darangshi Oreum, a parasitic volcano [

51]. The village is also notable for its traditional haenyeo (female divers), whose communal fishing practices, recognized by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage—defined as “the practice, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills as well as the instruments, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces associated therewith that communities, group and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage” [

52]—are central to Sehwa’s identity [

53].

Historically reliant on agriculture and fishing, especially its signature carrot crops, the village faced economic decline when these industries waned. Similar to other rural communities, Sehwa has also experienced the outmigration of young and middle-aged residents, population aging, and the influx of newcomers, which have weakened traditional community bonds [

54]. As shown in

Figure 3, Sehwa village also experienced a steady population decline, although it was less pronounced than in Gohan. In response, the community embraced tourism, leveraging its cultural assets and natural beauty. Its efforts earned Sehwa recognition as one of UN Tourism’s “Best Tourism Villages” in 2023, highlighting its culinary heritage, haenyeo storytelling, and culturally immersive food experiences [

55].

3.3.4. Overview of the Sehwa Village Cooperative (Case 2)

The Sehwa Village Cooperative operates the Jilgeuraengi Community Hub Center, which was created by remodeling the community’s abandoned general welfare center. The cooperative’s origins trace back to 2015, when Sehwa-ri was selected as a target site for the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs’ Rural Center Revitalization Project. The initiative secured a budget of 8.6 billion KRW (approximately 6.3 million USD), including national funding, to address pressing local issues such as population aging and the influx of newcomers [

56]. In response, village residents convened to share ideas and, through expert consultations, developed a comprehensive community revitalization plan.

Under the leadership of the village head, cooperative information sessions were organized in August 2019 across all six natural villages within Sehwa-ri. These efforts resulted in 477 residents, comprising farmers, haenyeo (female divers), and other community members, out of a total population of approximately 700 investing a combined KRW 270 million (around USD 200,000) [

56]. This collective effort led to the formal establishment of the Sehwa Village Cooperative in October 2019. Today, the cooperative’s primary mission is to revitalize the village community and reinvest profits from income-generating activities into addressing local challenges and community needs. With a current membership of 494 individuals, the cooperative collaborates with provincial government agencies and private companies, leveraging grants and funding for facility improvements, staff salaries, and sustainable income-generating projects.

4. Results

This section presents the findings from the two case studies, focusing on how each cooperative operationalized circular economy principles through adaptive reuse and community engagement.

4.1. Case 1: The Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative—Revitalizing an Entire Village Through Adaptive Reuse

As described in the earlier section, the village hotel 18th street project emerged in a former coal-mining neighborhood that experienced severe depopulation and widespread building abandonment following the closure of local mines. Many houses built in the 1960s and 1970s stood vacant, village commercial alleys were underused, and the area’s image was further overshadowed by its proximity to a nearby casino resort that was developed as part of a large-scale redevelopment initiative that followed the mining industry’s collapse. In contrast to neighboring towns that pursued capital-intensive tourism projects through casino resorts and ski resorts, this small community adopted a decentralized and innovative “village-as-hotel” model that prioritized the adaptive reuse of existing structures. Through this model, abandoned houses and shuttered shops were retrofitted into guest rooms, cafes, studios, and shared offices, avoiding demolition waste and capitalizing on the embodied carbon of the original buildings as presented in

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

The transformation was achieved through a lease-for-retrofit model, in which the cooperative negotiated directly with individual property owners to repurpose their unused buildings. Because the cooperative did not own these properties, members began by renovating their own homes and first demonstrated visible improvements, such as façade restorations, alley cleaning, and new signage, to rebuild community trust and spark local interest. These early interventions served as tangible proof of concept, convincing other property owners to participate.

As a legally recognized tourism cooperative, the organization was eligible to apply for government grants that individual residents or private businesses could not access. Through its own initiative, the cooperative identified and secured such grants to finance substantial renovations of abandoned houses and commercial buildings, converting them into guesthouses, cafés, studios, and shared workspaces. These efforts not only revitalized the village’s physical environment but also created a replicable model of collaborative regeneration. As participation expanded, local government agencies followed with complementary infrastructure investments, including block paving, lighting, and parking facilities, reinforcing the cooperative’s bottom-up revitalization process.

As the street gradually transformed through the cooperative’s adaptive reuse initiatives, programming and activation of spaces became the central mechanism for sustaining revitalization. Rather than relying on new large-scale construction, the cooperative focused on curating diverse experiential programs that animated the repurposed sites and maintained community engagement. Seasonal night-sky tours, craft workshops, mining heritage walks, temple visits, and docent-led tours of 18th Street encouraged year-round visitation and diversified the use of rehabilitated spaces (

Figure 9). Governance within the Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative is intentionally maintained through a small-scale structure characterized by capped dividends, transparent accounting, and oversight by a board and auditors to ensure accountability. This compact membership model enables agile decision-making, rapid implementation, and sustained financial viability. The project evolved from initial micro-grants supporting lodging and tour operations into a self-sustaining enterprise that transformed an area once known for “vacant-house alleys” into a vibrant hospitality corridor, attracting resort visitors to the village as a destination in its own right.

Despite these achievements, the cooperative’s leadership remains mindful of its dependence on tourism, estimated to comprise roughly 90 percent of local economic activity, and the potential risks posed by policy or market shifts. Future priorities include formalizing maintenance and end-of-lease transition protocols, establishing utilization metrics such as space-hours, and building capacity among property owners who gradually assume operational responsibilities for the renovated facilities. During the initial phase, the cooperative directly managed several adaptively reused spaces, such as guesthouses and cafés, but ownership participation has increased over time as properties were handed back for local operation. As many owners lack prior experience or training in managing tourism-related facilities, targeted hospitality and service training will be essential to ensure operational quality, sustain visitor satisfaction, and secure long-term resilience and balanced growth.

4.2. Case 2: The Sehwa Village Cooperative—Transforming a General Welfare Center into a Multipurpose Community Center

The second case, the Sehwa Village Cooperative, exemplifies how adaptive reuse can strengthen social and economic resilience in coastal rural communities. Unlike the mountain-based Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative, Sehwa operates in a fishing and farming village experiencing population aging and weakening community cohesion, driven by the outmigration of young adults to urban areas for education and employment, as well as the influx of foreign newcomers. The cooperative’s central project involved repurposing the village’s former general welfare center into the Jilgeuraengi Community Hub, a multi-functional facility that houses a café, meeting rooms, guesthouses, and shared workstations for workcation users (

Figure 11). This adaptive reuse approach prioritized the conservation of the existing structure’s cultural and environmental value while enabling diverse community and tourism functions. By activating previously underutilized or vacant spaces, the cooperative fostered a dynamic venue for tourism and educational programs, co-working, and wellness activities, effectively maximizing the use of local assets and minimizing new construction.

The newly constructed Jilgeuraengi Center broadened the scope of services. Its first floor houses the Sehwa Village Cooperative office; the second floor features a café and a market for locally produced products; the third floor provides shared offices (workcation stations) and seminar rooms; and the fourth floor includes guesthouse accommodations (

Figure 12). At a time when the term workcation was still unfamiliar, the center opened Jeju’s first shared office in 2021. As the Jilgeuraengi Center’s shared office space gained attention through social media, visitors from across the country began traveling to Sehwa for workcations, and today it attracts both office workers and tourists alike [

54].

A defining feature of Sehwa’s approach is the integration of human capacity building into its circular economy practices. The cooperative provides financial support for residents pursuing certifications in free-diving, lifesaving, Nordic skiing, and boat operation, thereby enabling residents to design and deliver tour programs that draw on the community’s cultural heritage and natural resources. As shown in

Figure 13, signature offerings include haenyeo heritage tours in partnership with a local museum, wellness walks on the Darangshi Oreum and Nokkomi volcanic cones, and week-long live-in experiences that rotate guests through different local lodgings and eateries [

58]. Workcation programs further optimize the use of existing guesthouses and hub facilities during off-peak tourist seasons. At the center of these developments is the remodeled Jilgeuraengi Center, which anchors and supports the cooperative’s diverse initiatives.

The cooperative operates with a large and diverse membership of nearly 500, supported by transparent financial reconciliation, capped dividends, and democratic decision-making processes. Initial public support came through designation as an “experience village” and the funding of one coordinator position. However, the cooperative now functions independently of annual government subsidies, relying instead on program revenues reinvested into community projects while applying for diverse grants from various government agencies. The outcomes include year-round utilization of village spaces, expanded income opportunities for older residents, and stronger civic participation. As a result, Sehwa has recently seen a modest population increase (

Figure 2).

Framed within the principles of the circular economy, Sehwa’s approach highlights the reuse of existing buildings and the creation of circular value by developing tourism rooted in local heritage and natural resources. By training and supporting residents to design and deliver programs, such as Haenyeo heritage tours and eco-wellness walks in Darangshi Oreum, the cooperative strengthens local capacity while ensuring that tourism revenues are reinvested into community assets. In doing so, it advances cultural sustainability by preserving traditions, social sustainability by fostering community participation and cohesion, and economic sustainability by diversifying income opportunities within the village.

5. Discussion

The cases of the Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative and the Sehwa Village Cooperative illustrate distinct yet complementary pathways through which rural communities operationalize circular economy principles to foster tourism-led revitalization while minimizing environmental and social costs. Both initiatives center on the adaptive reuse of existing physical and social assets, reflecting a shift from linear “build and consume” models toward regenerative, community-centered development.

Table 3 presents a comparative summary of the two cases. As shown, the comparative framework integrates both theoretical and empirical dimensions of circular economy practices. The criteria were derived from our research questions and key constructs in the literature, such as adaptive reuse, value retention, and governance mechanisms, and were refined inductively through cross-case analysis [

38,

39]. This framework provided a structured yet flexible basis for comparing how each cooperative implemented adaptive reuse and operationalized circular economy principles within its local context.

Regarding adaptive reuse and asset recirculation strategies, Case 1 (the Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative) reimagines a declining former coal-mining district through a distributed “village-as-hotel” strategy. The cooperative’s lease-for-retrofit model transformed derelict housing stock into guest accommodations, cafés, and creative workspaces without major new construction, thereby extending the lifecycle of built assets and reducing material waste. Early, low-cost facade and public-space improvements fostered visible progress and encouraged broader participation from property owners. The cooperative’s adaptive practice not only preserved embodied carbon but also retained the village’s spatial fabric and cultural identity, serving as a primary catalyst for economic activity. Seasonal events and heritage-based experiences have further increased year-round space utilization and visitor engagement.

In Case 2 (the Sehwa Village Cooperative), an underused welfare building was transformed into a multifunctional community hub integrating educational, tourism, and wellness programs. While its circular economy practice similarly conserved embodied carbon through the reuse of existing structure, its focus on human capital regeneration has been equally transformative. By providing residents with training and certifications in diving, guiding, and wellness programs, the cooperative has empowered community members through capacity building and skill development, enabling them to operate local tourism programs that draw on existing natural and cultural resources, while utilizing the repurposed facilities (e.g., café, office in the community hub) as supportive spaces for coordination and community use.

In terms of governance as a mechanism for advancing circular economy principles, both cases, regardless of their scale of membership, demonstrated the effectiveness of the cooperative model in enabling community-led regeneration. The cooperatives’ legal status provided eligibility to access and implement government grants, while financial accountability was maintained through capped dividends, transparent accounting, and a gradual transition toward commission-based revenue structures. This governance model fostered community trust, equitable benefit-sharing, and collective ownership, although achieving full financial self-sufficiency remains an ongoing process.

Both cases also highlight how adaptive reuse projects grounded in circular economy principles contribute to local economic value creation and the recirculation of that value within the community. The Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative stimulated economic and social revitalization by increasing property values and attracting tourism spending, thereby restoring residents’ sense of confidence and attachment to place. Collective efforts to maintain shared spaces further reinforced social cohesion and community identity. Similarly, the Sehwa village Cooperative prioritized the retention and circulation of local benefits. Through cooperative ownership and resident-led program implementation, tourism revenues were circulated within the community, while reinvestment in local training and programs translated economic gains into capacity-building and long-term community resilience.

Overall, a comparative view highlights both convergence and divergence in circular economy practice. Both cases demonstrate the reuse, refurbishment, and repurposing of existing assets as foundational strategies, prioritizing programmatic activation over capital-intensive infrastructure expansion. Both employ cooperative governance models to ensure community ownership and value retention, and both reinvest a portion of tourism revenues into local capacity building. However, their emphases differ: the Case 1’s approach is place-centric, leveraging architectural and spatial revitalization to reframe the village as a tourism destination—linking fragmented resources into a cohesive tourism platform, whereas the Case 2’s is people-centric, embedding skills development within its reuse strategy to expand local agency in tourism operations, emphasizing the integration of human capital development into physical asset reuse. This distinction reflects different pathways to achieving circularity, one prioritizing the physical regeneration of underutilized space, the other embedding circularity into social systems and human capital.

Both cases reveal ongoing challenges and future priorities. In Case 1, while the initiative has successfully reactivated a once-abandoned streetscape, its heavy dependence on tourism (estimated at 90 percent of local activity) underscores the need for diversification strategies. To sustain the success of community tourism in Gohan, the Village Hotel 18th Street Cooperative should prioritize training programs for homeowners resuming operations after the lease period, ensuring they can maintain service quality and repeat visitation. The cooperative also envisions connecting underutilized facilities, cultural sites, and natural attractions into integrated tourism products. This approach extends the lifecycle of existing assets, reduces redundancy, and circulates benefits across municipalities and stakeholders.

In Case 2, the Sehwa Village Cooperative seeks to strengthen international visibility and resident capacity by hosting global forums and offering hospitality and interpretation training. Its focus is on maximizing the use of existing infrastructure through layered cultural programming and resident-led activities rather than new construction. By recycling and amplifying local assets, such as Haenyeo traditions, food culture, and agricultural practices, the cooperative can generate recurring value for residents and visitors alike. Engagement with international forums will further promote the circulation of knowledge and recognition, reinforcing local resilience.

Together, these cases suggest that rural tourism development guided by circular economy principles can extend beyond environmental efficiency to encompass social regeneration, cultural continuity, and economic resilience. They also demonstrate that circular economy practices in tourism need not follow a uniform model; rather, they can be contextually adapted to local resource endowments, governance capacities, and community priorities. Future scaling will require addressing identified vulnerabilities, such as tourism dependency in Case 1 and the need to institutionalize sustainability practices in Case 2, to ensure that circular practices contribute to long-term rural resilience.

6. Conclusions

This study examined two distinct yet complementary models of circular economy practice in rural tourism contexts: the Village Hotel 18th Street initiative in Gohan and the Sehwa Village Cooperative in Sehwa. Despite differences in scale, context, and resource bases, both cases demonstrate that circular economy principles in rural revitalization extend beyond material reuse to encompass the circulation of economic, social, and cultural value within a defined locality. This study indicates that (i) adaptive reuse of underutilized assets can anchor place-based tourism economies without large-scale new construction; (ii) tourism cooperatives as a governance structure play the central role and work effectively, particularly enhancing local participation and transparency as well as utilizing local heritage and assets; and (iii) sustaining local buy-in requires mechanisms for reinvestment of revenues into community projects and equitable participation in program benefits.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study extends circular economy theory by introducing tourism cooperatives as a governance structure that operationalizes circular economy principles through adaptive reuse, linking community-based governance with regenerative local development. By examining tourism cooperatives as mechanisms that enable circular value retention and resource recirculation at the community scale, the study advances theoretical understanding of how social and organizational systems facilitate the implementation of circular economy practices in rural contexts.

This case study contributes to rural tourism and circular economy literature by broadening the conceptualization of “loops” beyond physical material cycles to include value loops and social benefit cycles [

61,

62]. In the case cooperatives studied in this paper, value loops emerged as locally generated economic benefits, such as profits from tourism services, sales of local products, and reinvestment in infrastructure, that were deliberately recirculated within the community rather than leaking to external actors. Social benefit cycles were evident in the way tourism activities created jobs for locals, provided funds for residents to pursue training and obtain necessary or required certificates, strengthened community cohesion through collective revitalization of alleys and villages, and reinforced residents’ sense of empowerment. These cycles were self-reinforcing: active resident participation led to skill development and collective pride, which in turn encouraged further engagement and innovation in tourism initiatives.

This reframing positions tourism cooperatives as a governance model that enables transparent revenue allocation and fosters inclusive participation, ensuring that cooperative-led revitalization strengthens community empowerment and resilience. By structuring decision-making through mechanisms such as delegate assemblies, performance-based referrals, and in-kind benefit capture, tourism cooperatives operationalize circular economy principles at the micro-local scale. In doing so, they integrate economic and social returns into rural tourism systems, creating regenerative processes that align with both circular economy thinking and community-based tourism theory. This integrated governance and operational approach highlights how a circular economy can be meaningfully localized in rural contexts while addressing the socio-cultural dimensions essential for sustainable revitalization.

6.2. Practical Contributions

From a practitioner’s perspective, the two cases illustrate actionable strategies for rural destinations seeking to embed circular economy principles. First, both demonstrate that prioritizing the adaptive reuse of existing structures can reduce environmental impact and financial risk, while simultaneously preserving the architectural and cultural character of the locality. Second, formalized benefit-sharing arrangements, including the use of capped distributions, earmarked community funds, and non-cash in-kind contributions, proved essential for maintaining community legitimacy and ensuring that spending is recirculated locally. The cases also underscore the importance of engaging both members and non-members in tourism programming and promotions to prevent exclusivity and to sustain broad-based community goodwill. Finally, they highlight the value of investing in local human capital, such as through licensing, certification, and skills training, to enable residents to deliver tourism products and services directly, thereby reducing dependence on external operators and fostering greater long-term self-sufficiency.

For policymakers, the cases underline the importance of flexible yet accountable support mechanisms. Seed funding and coordination staff can catalyze early-stage operations, but long-term autonomy is strengthened when cooperatives generate self-sustaining revenues. Rather than relying on top-down, government-led projects, rural revitalization policy should prioritize indirect forms of support that empower local actors. As evidenced in the cases, cooperatives function most effectively when driven by residents’ voluntary participation and sustain motivation, which, over time, strengthens local skills and collective capacity. Governments can therefore play a catalytic role by providing targeted grants to cooperatives or investing in essential infrastructure such as tourist parking facilities, paved access roads, or other amenities that enable community organizations to deliver tourism services more effectively. Policy should also encourage multi-scalar governance linkages, connecting village bodies, cooperatives, and municipal authorities, to enhance transparency, align development with local priorities, and integrate tourism into broader socio-economic planning. Additionally, circular economy adoption can be accelerated by creating regulatory and incentive frameworks for adaptive reuse, in-kind benefit programs, and small-scale environmental improvements that align with tourism product development. Such an approach not only preserves community autonomy but also ensures that the benefits of tourism remain embedded in the local economy, contributing to the long-term sustainability of rural tourism initiatives.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study employed a qualitative case study approach to provide an in-depth and contextual understanding of cooperative-led adaptive reuse in rural tourism. While this method offers rich insights into how adaptive reuse initiatives were implemented and managed within the communities [

38,

39], the findings are drawn from two cases in South Korea, which may limit their generalizability. Further studies could address the data and measurement gaps identified here, including household-level income tracking, longitudinal property and business performance data, and environmental impact metrics (e.g., waste reduction, material life extension). Comparative research across different cultural and policy environments would clarify how governance models and benefit-sharing systems adapt to varying legal, economic, and social contexts. Finally, integrating visitor-side circular economy behaviors such as participation in refill culture, reuse-oriented accommodations, or low-impact programs could extend understanding of circular economy adoption from the supply side to a more holistic destination perspective.