Abstract

This study investigates the institutional dynamics behind the phenomenon of apartment construction within urban parks in South Korea, using the Policy Arrangement Approach (PAA) as an analytical framework. By comparing two landmark policies—the Citizens Apartments Construction Project (CACP69) of 1969 and the Private Park Special Project (PPSP09) initiated in 2009—it will reveal how park erosion has been legitimized through shifting governance structures, legal mechanisms, and discursive strategies. CACP69 emerged under authoritarian rule to address housing shortages, leveraging public authority to repurpose park land. In contrast, PPSP09 reflects neoliberal tendencies, incentivizing private capital to develop unexecuted park sites amid looming sunset clauses. Both cases illustrate how the long-term neglect of park creation and ambiguous legal definitions have enabled the commodification of public green spaces. The study argues that park management policies in Korea have been shaped by a property-rights-oriented logic, sidelining community participation and ecological integrity. These findings offer critical insights into the intersection of urban planning, environmental governance, and the privatization of public space.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Background of the Study

A public park is a universal resource in a city with a variety of functions [1,2]. Parks redefine the lost link between humans and nature in cities and balance the dominant gray infrastructure with green infrastructure [3,4]. Parks provide health benefits and can be used as a natural alternative for socio-economic benefits combined with urban components [5,6,7,8]. Parks strengthen the environmental–ecological functions of cities by providing ecosystem services. Some countries are reforming their park management systems and various organizations to address the challenges of climate change [9,10]. The development of urban and landscape ecology optimizes space–ecological management and strengthens urban and natural linkages by providing a conceptual basis for the development of parks [11,12,13].

One of the definitions of a park in the dictionary is “a tract of land that often includes lawns, woodland, and pasture attached to a country house and is used as a game preserve and for recreation” and “an area designed for a specified type of use (such as industrial, commercial, or residential use) [14]. If this concept is expanded, parks can be linked to housing development. The production and recovery of park space can lead to changes in housing prices and the lives of residents [15,16,17]. In addition to the traditional discourse of urban ecology development, parks also serve as a social space that promote social coordination with neighbors, improve the dissemination of information through direct contact, civic pride, community formation, and crime prevention [18,19,20,21].

Looking at historical records and previous studies, housing development provided both opportunities and threats to parks [22,23,24,25]. First, in terms of opportunity, in London, England in the 19th century, despite the recession in housing construction [26], individual houses were built around Regent Park (1818) in London, owned by the Royal Family. The simultaneous development of parks and houses at the time improved the unsanitary conditions of overcrowded housing, which was called “the city of dreadful night” [27]. In the 1920s, C. Perry’s neighborhood unit established the scope of attachment to a community by controlling the density of residential complexes through proper park layout [28].

At the same time, from the moment parks were invented, parks were eroded by housing construction. Birkenhead Park (1884) was the first park where public finance was injected. Despite its historical significance, part of the park was used for housing development [29]. In 2009, Tokyo, Japan implemented a policy to allow the private sector to build middle- to high-rise buildings in parks to develop Kayama Park. The buildings were not able to be built for a long period of time, and the project was not implemented considering the public nature of the park [30]. In all of these cases, part of the land was encroached by residential buildings to cover the cost of creating a park.

Regarding park erosion, previous studies have focused on the problem of private capital on public land and its legal mechanisms. First, the former view is based on the environmental definition that appears in discourses on nature. The process of denying natural resources appears to be the result of reducing citizens’ access to nature. This process begins with the emergence of private capital receiving preferential treatment from specific groups in the region. Parks are democratic nature, being originally operated on a public budget. However, this discussion emphasizes that the privatization of parks leads to a decrease in public investment and does not provide full social benefits [31,32,33,34,35]. The latter view is based on the former theory, and a government’s policy and legal mechanisms play a role in the conflict between the preservation of parks and land use. Zérah argued that “park erosion leads to a decrease in parks,” but legal mechanisms are more interested in supporting urban growth than in protecting the environment and ignoring the scientific truth [36].

1.2. The Purpose of the Study

As stated above, Korean parks have also been threatened by housing development for a long time. Official records show that as much as 1556 km2 (1971–2018) of the nation’s green belt has disappeared: 28.8% of the initial amount was used for supplying housing [37,38]. From 1940 to 2000, the area of parks that was supplied by housing development was 5.13 km2, but the policy also reduced the area of parks by 5.68 km2 [39].

The erosion of parks by housing development resulted from policy intervention by the state which inevitably affects park management in cities. The land originally reserved for parks serving as public goods are now being diverted for capital or property use which makes one doubt whether the government is implementing policies in accordance with the original intention for the creation of the park. Therefore, this study analyzes the relationship between housing development and park management policy in the boundary of parks as public goods. The detailed purpose of this study is to find the answer to the following questions:

- What caused housing developments in parks?

- What are the changes in park management policy in response to the previous question?

- How does park management policy mechanism work?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Policy Arrangement Approach (PAA)

When a policy is limited to a park as a type of physical urban facility, the political context of the policy affects the ‘place keeping’ of the park. Thus, policy plays an important role in improving the quality of the physical environment or improving the social disadvantages of the neighbors so that sustainability as a dominant paradigm can be implemented [40]. In this respect, in existing park policy research, policy is regarded as a ‘judgmental role’ that interacts with society for park development, management goals, and ‘instrumental means’ to realize strategic planning and management [41]. This trend stems from the social practice that policies are predominantly state-dominated and made from the frame of rational choice. For this reason, a large part of the policy studies commissioned by government authorities have induced ‘management’ bias by revealing prejudice through strategic interpretation or overemphasizing substantive relevance [42,43].

After 1980, with the emergence of new institutionalism, a different type of debate from traditional policy research began. Researchers interested in this concept have focused on the characteristics of institutional or policy changes over time. The first characteristic is to observe and analyze the phenomenon in which the actor’s behavior solidifies into patterns and structures. The second characteristic is to gradually or radically adapt the meaning of the policy according to the rules of action and organizational structure to reproduce and recreate the meaning of the relevant policy [44,45,46].

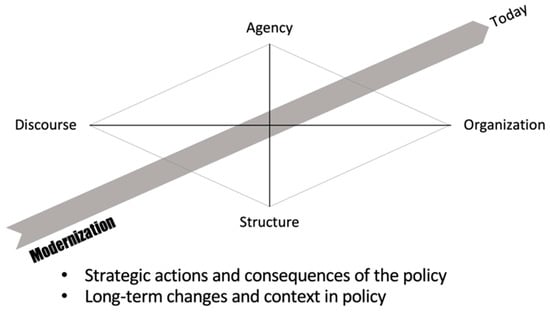

Among the policy analysis theories inspired by neo-institutionalism is the policy arrangement approach (PAA). Policy arrangement is defined as “temporary stabilization of the content and organization of a specific policy area” [47]. According to this concept, policy research does not (1) explain routine and temporary policy processes but analyzes mid- to long-term changes and patterns of stable institutions. (2) In most cases, the approach is described and characterized from a comparative perspective. (3) The approach interprets the mechanism behind relative safety or change and the dynamics of the mechanism. Through this, (4) the policy process is examined from an institutional perspective, and the definition is applied to practical and organizational aspects. (5) Considering the long-term perspective of specifying modern society, it is initially captured as a comprehensive concept of ‘modernization’.

Thus, the compressed concept of PAA deals with policy innovation and traditions and aims to interpret them from the perspective of institutional dynamics. In this process, PAA analyzes policy practices and structural changes [48,49,50]. Through this, PAA suggests that institutional patterns or policy mechanisms understand both practical and organizational problems and their interactions. Based on the idea of modernization and the process of constructing modern society, this paper proposes policy decisions that reflect the process of long-term contextual social and political trends as well as the consequences of strategic actions.

PAA analyzes policies sequentially across dimensions ranging from agency to structure, and from discourse to organization (Figure 1). The advantages of this crossing dualities are that it can reach approaches related to social science in general, especially environmental policy analysis. An approach that focuses on the behavior and capabilities of the agency is primarily based on rational choice theory. The agency acts on the assumption that it is reasonable, knowledgeable, and informed. Structure regards environmental issues as an inevitable consequence of the unilateral instrumentalization of the combination of capitalist production systems and the lack of the political system’s ability to control them. This contains views of neo-Marxism, but it also includes institutions and their ability to act, which are the real drivers of environmental degradation. Discourse is an important part of policymaking as a “shared way to understand the world.” In an environment, discourse includes awareness and attitudes toward problems and approaches to problem solving. Organization is a device that is purposefully built to realize discourse as a strategic policy. This deals with ideological–organizational duality to address the success of environmental modernization and the impact it has on policy strategies [49,50,51].

Figure 1.

Framework of PAA.

2.2. Method

This study is based on empirical analysis in line with PAA studies reporting changes in policy [49]. Keeping PAA in mind, which analyzes the modernization process and changes in policy, this study focuses on two different time frames (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study materials.

One is the Citizens Apartments Construction Project (CACP69), which was executed in 15 different parks in Seoul in 1969. This case started as part of a policy to respond to the rapid increase in Seoul’s population after the Korean War (1950–1953). This case is noteworthy in that it occurred immediately after the enactment of The Park Act, 1967, which was the first law to stipulate regulations on “building and management of urban parks” in 1967. However, a large number of constructions of apartment houses in the parks ceased after the collapse of civic apartments at Wow Park in 1970.

The following is the Private Park Special Project (PPSP09). In this project, the Korean government encouraged the development of apartments in parks. The project was implemented in cities across the country except Seoul in December 2009, when the Korean Urban Park Act newly inserted “The Special Case Concerning Develop Activities in Sites for Urban Parks.” What these two projects have in common is that natural parks have been legally eroded by housing.

To track the facts about the PAA, this paper collected the following research materials. First of all, each case has a different temporal range. For this reason, CACP69 was concentrated in data produced by public institutions from the early 1960s to the early 1970s when the relevant policies were implemented, while PPSP09 relied on data produced after 2000. In order to explore the entities participating in the policy area and the agencies and structures that contain normative frameworks that restrict or promote their actions, we collected park-related laws, park green space masterplan reports, and policy reports. Each law was obtained from the Ministry of Legislation, the government of the Republic of Korea, and the report was obtained from the Seoul Library and a national research institute. The following is a framework of perception that interprets and gives meaning to policy issues, and a power structure that reflects the distribution and accessibility of the resources of discourse and organization based on newspaper articles and research papers that introduce and discuss policy outcomes. Among them, newspaper articles were collected from portal sites, and old paper newspapers from the 1960s~70s dealing with CACP69 were viewed on Naver News Library, which provides original articles as digital images (Appendix A).

3. Results

3.1. Construction of Civic Apartments in Parks, 1969

3.1.1. Agent: Rapid Changes in Korean Society and Parks Managed by Public Authority

- ○

- An administrative vacuum at the parks

In Korea, the principle for managing its national territory began in Japanese colonial era. At that time, Japan made it a principle that the development and management of land would be managed by the public sector for efficient colonial rule and resource transport. Accordingly, the Chosun Planning Order for Urban Area was enacted in June 1934, allowing the Japanese Government-General of Korea to forcibly accept land determined by urban planning without compensation. Based on this, the Keijo government designated 140 parks (13.8 km2) in the current-day Seoul region [The Japanese Government General of Korea Notice No. 208, March 1940].

Furthermore, the public concept of land was reduced due to the sudden liberation of Korea (1945) and the Korean War (1950). At that time, there was an administrative vacuum in national land management, including parks. This occurred due to the lack of technical personnel in the government. A number of park-related properties were devastated, and the Government frequently sold the parks to the private sector [54]. In addition, 30 percent of houses in Seoul were damaged by the Korean War, and former residents built shanty houses on top of dilapidated parks.

The Park Chung-hee military regime, established in 1961, established various policies to justify itself as a revolutionary regime and carried out legal reorganization. Accordingly, the government enacted the Urban Planning Act to restore the “promotion of public welfare” and limited the subject of land development and management for public use by recognizing the nature of land as a public good. Thus, the right to decide on the use of the national land was established by the central government and the right to execute the use was placed in the hands of the local government [Urban Planning Act, 1962. §4 and §5]. Through this law, the government restricted inappropriate construction activities on state-owned land that was contrary to the set terms of disposal and use [41].

- ○

- Strengthening public power over parks and the emergence of Seoul mayor called bulldozer

The limitation of public power over parks was discovered by the Urban Planning Act. For example, in 1964, several civilians conspired to sell 2/3 of the Sajik Park site, which was the property of the Seoul Metropolitan Government, and the funds for the sale flowed into political circles [Kyunghyang Newspaper, 6 April 1964]. The government said it would review the proposal for the Park Act, which it withdrew to cover up the scandal. Furthermore, it included a regulation in the bill that “private rights cannot be exercised over land or objects that make up the urban park.” [Park Act, 1967 §36].

Seoul Mayor Kim Hyun-ok, who took office in 1966, made the most of his authority for the management of the land and parks that were established in the aforementioned way. He was called the “Bulldozer Mayor,” and he advocated the modernization of the country and set the city slogan as the “Year of Construction Rush” [55]. He built a new Seoul using a potent power system and completed the current framework of Seoul. From 1969 to 1971, he completed the construction of 434 buildings comprising 17,402 apartment units, including 277 built across 15 parks—all aimed at alleviating housing shortages (Table 2).

Table 2.

The size of the construction of civic apartments in the park and the area of the abolished park.

3.1.2. Structure: Social Structural Causes for Housing Construction in Parks

- ○

- Seoul is full

The population of Seoul exploded in a short time. From 1960 to 1965, the number of people in Seoul increased by more than 300,000 every year, and the average population growth rate in Seoul reached 13.14% [Kyunghyang Newspaper, 6 February 1965]. As far back as 1910, the population of Seoul increased by 18 times over the next 55 years. As a result, 283,704 households, or 46% of the total number of households, did not own homes in Seoul. The housing rate continued to decline from 55.27% (1962) to 49.00% (1966) [Seoul Statistical Yearbook 1961–1970].

According to Article 245 of the Civil Law at the time, “The period of acquisition of real estate ownership due to occupancy”, the occupant could own the land if the period of unauthorized occupancy was more than 20 years. Under this law, urban planning sites, including parks and private land whose owners were unknown, were in the hands of illegal building occupants. Therefore, in order to solve Seoul’s overpopulation and housing shortage, Mayor Kim Hyun-ok fostered unauthorized housing (substandard housing) while supplying a large number of civic apartments. The former will be discussed in detail in the next section, but the latter was also closely intertwined with park management and maintenance. In 1968, the Seoul Metropolitan Government cultivated 1.34 km2 of unauthorized housing areas and 44,493 buildings. Among them, unlicensed houses equivalent to 0.73 km2 (51.9%) and 17,478 buildings (39.3%) were distributed in the park [The Masterplan of Seoul Urban Planning Park, 1968]. Eungbong Park (149,327 m2/1,204,408 m2) was the most encroached, and so were Changgyeong Park (2460 m2/183,300 m2), which was part of a palace cultural artifact, and Sajik Park (63,210 m2/192,400 m2).

- ○

- Uncreated urban planned parks and expansion of Seoul

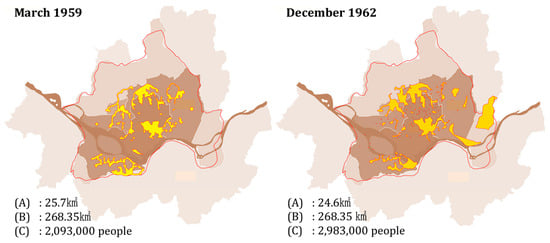

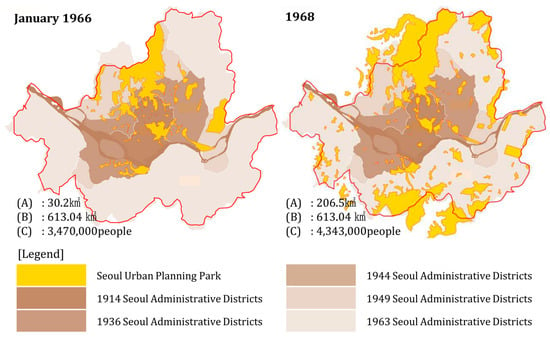

In the 1960s, the Seoul Metropolitan Government revised or changed the park plan several times, but it continued to be neglected without the creation of a park (Figure 2). The area of parks planned in Seoul increased from 13.8 km2 (1940) to 24.9 km2 (1965), but only 2.1 km2 (1964) was constructed [Seoul Statistical Yearbook 1961–1970 and Seoul Urban Planning, 1965].

Figure 2.

Changes in Seoul’s Urban Planning Park in the 1960s. [A] is the park area. [B] is the area of Seoul. [C] is the population of Seoul. Source: It was reconstructed by the author with reference to the following literature. Seoul Statistical Yearbook, 1961–1970 (research report to Seoul Metropolitan). Seoul Urban Planning Book, 1965 (research report to Seoul Metropolitan). The Masterplan of Seoul Urban Planning Park, 1968 (research report to Seoul Metropolitan).

In 1963, the area of Seoul’s administrative area expanded by 2.3 times from 268.35 km2 to 613.04 km2 [The Ministry of Construction Notice No. 524, August 1963]. Kim Hyun-ok, who took office as mayor of Seoul in 1966, was tasked with establishing and implementing urban plans to cope with the expanded administrative area of Seoul. The Masterplan of Seoul Urban Planning Park (1968) was established to reorganize parks as part of an urban plan. The park redistribution method was based on a population allocation plan to relocate people to the outskirts, in line with the new boundaries of Seoul. Accordingly, as park green areas were distributed to area before being incorporated into Seoul in 1963, parks such as Ansan, Inwang, Waryong, Samcheong, Namsan, Eungbong, and Haengdang, which were at the outskirts of Seoul, were located in the city center. With this plan, the planned parks in Seoul were planned to cover 206.5 km2 at 557 locations, similar to the area of Seoul before 1963.

3.1.3. Organization: Establishment of Policy and Institutional Know-How for Housing Construction in Parks

- ○

- Preliminary policies for the construction of housing in parks

At that time, the Korean government used park land to solve serious housing problems after the war. At the same time, it aimed to strengthen public power to prevent damage to the parks by the private sector. After the Korean War, the government started encouraging housing construction in parks, and the policy changed in stages to lift the designation of parks for building permits.

As the first policy, the Seoul Metropolitan Government changed the regulations on “Building on land in conflict with urban planning” in the Construction Administrative Guidelines in August 1953. The existing policy strongly restrained the construction of new buildings that were in conflict with urban planning, but it was later converted to a fairly loose policy [The Past and Future of Seoul Urban Planning, 1962] [56].

Then, President Rhee Syng-man ordered to “stop urban planning” in 1956 to encourage private construction. Due to this order, the Seoul Metropolitan Government built many houses for the working class by fully utilizing the park area scattered across the city (Dong_A Daily, 13 July 1956)”. And in April, 44 parks that were not built were “conditionally approved for temporary construction (Dong_A Daily, 13 August 1956)”. Seoul Mayor Ko Jae-bong, who implemented the policy, said at the time, “In light of the current financial situation in Seoul, it is expected to take some time for parks to be constructed, so this is a measure to ensure that private land is properly used by its owners in the meantime” [News·Seoul, 15 October 1956].

During Japanese colonial era, the park planning standards of the Keijo government were set at areas with an altitude of 75 m or higher among hilly areas. At that time, areas above that elevation were the point where water supply could not reach, and the Keijo government designated the undeveloped area as park sites. In 1962, the Seoul Metropolitan Government of Park Chung-hee pointed out that the restricted elevation set by Japan was the main reason for the erosion of park sites, but designated elevations were changed to more than 80 m (1966) and 120 m (1968) to expand the housing development area [The Masterplan of Seoul Urban Planning Park, 1968]. At the same time, the government established the “Planned Park Maintenance Standards” in 1962 so that park area designation could be lifted “where existing general buildings are concentrated in public and private lands” and “where housing construction projects are taking place in state-owned land.” In addition, old palaces or historical sites could be designated as parks to make up for the undesignated park sites [The Ministry of Construction Notice No. 187, December 1962].

- ○

- A legal mechanism for the construction of housing in parks

At that time, the Park Act, the basis for installing and managing parks in the city, contained both the dual nature of preservation/protection and development. As mentioned earlier, the Park Act was a regulatory law that was enacted “with the aim of contributing to the improvement in people’s health, recreation, and emotional life” by limiting private activities in parks and strengthening public authority. For this reason, this Act defines urban parks as “parks and green spaces installed as urban planning facilities” which “restriction on private rights” [Park Act, 1967. §2 and §36]. The Enforcement Decree of the Park Act and the Enforcement Rules of the Building Act stipulated park facilities that can be installed in (urban) parks [Enforcement Decree of Park Act, 1967. §1, 200, 1965. §114-2]. According to this Act, the Park Act does not actually define houses or apartments as park facilities.

Article 8 of the Park Act states, “Parks cannot be abolished or changed. [Park Act, 1967. 88]”, and in principle, parks are set as a permanent preservation space. There is also an exception clause, “Inevitable case for military or public interest,” but housing did not fall under this category [Enforcement Decree of Park Act, 1967. §5]. In fact, it seems impossible to change the park area by constructing a house in the park. However, the law also had the opposite binding force of abolishing or changing the area under the conditions of it “not actually being used as a park or recognizing that the utility as a park has been lost”, enabling the construction of housing in the parks.

3.1.4. Discourse: Intentions and Approaches to the Construction of Apartments in Parks

- ○

- The construction of civic apartments and the elite’s intent

The construction of civic apartments was an inevitable measure to provide sufficient housing and a spectacle to show a modernized Seoul. At that time, four organizations participated in the expanded urban planning of Seoul. Among them, the Housing, Urban and Regional Planning Institute (HURPI) focused on developing a housing model suitable for Korea and naturally showed great interest in civic apartments [57,58]. HURPI was founded by Oswald Nagler in 1966 and belonged to the Ministry of Construction in Korea, but it received financial and operational support from The Asia Foundation in the United States.

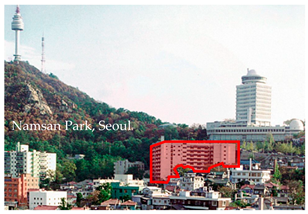

The Seoul Metropolitan Government and HURPI first selected Geumhwa Park among other candidate sites for pilot city planning under the guidelines of “high-density urban development” (Figure 3). They conducted thorough field surveys and case studies in the Philippines and Vietnam, where low-cost housing projects were implemented with aid funds for low-cost housing design for low-income families. HURPI attributed the increase in urban poor every year to poor housing located on the outskirts and existing landowners moving to the center of the city as those houses were sold or leased. They dealt with the problems of standardization, land use, supply method, and housing finance of low-rise apartments through specific housing plans for Geumhwa civic apartments and suggested the following step-by-step approach strategy.

Figure 3.

Shantytowns and civic apartments in Geumhwa Park. Source: Seoul Photo Archives [59].

First, a land formation process was planned to develop state-owned land into a large number of residential areas for the masses. Second, it was encouraged to build low-rise apartments that were smaller than the government-supplied public houses to save construction costs. Third, the apartment plan was a self-help housing method to reduce public financial burden. Fourth, the government proposed some support for interest costs, proposed low down payments, and long-term loans so that the houses could be bought on a monthly salary for middle- and low-income families [58].

Seoul Mayor Kim Hyun-ok, who planned to supply civic apartments, was also interested in Geumhwa civic apartments. From the perspective of the Seoul Metropolitan Government, supplying apartments to substandard housing sites in hilly park areas offered two key advantages: it required no land acquisition costs, and the city retained ownership of the land after development. However, as the Seoul Metropolitan Government increased the supply area of apartments by two to three times higher than the number recommended by HURPI, the amount of bank loans for those who wanted to buy the homes increased. As a result, the original intention of the self-help and self-owned housing model for the low-income class was questioned as the target of the civic apartment supply shifted to the middle class. And the aid organization was deprived of experimental opportunities, creating a point of conflict with government officials.

- ○

- Demolition of shantytown, construction of civic apartment, and release of parks

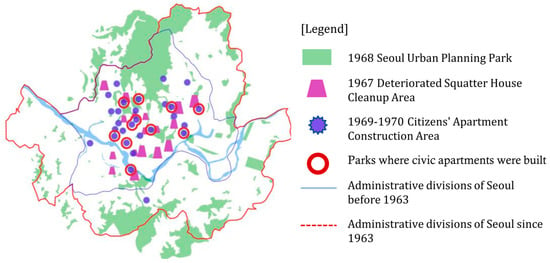

The construction of civic apartments was carried out in stages. At that time, Seoul Mayor Kim Hyun-ok built settlements on the outskirts to remove unauthorized houses at the city center. The “Substandard Buildings Removal Plan” was established in 1967. Among the demolished unlicensed houses in 1969, it planned to build civic apartments on state-owned land [Substandard Buildings Removal Plan, 1967] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Location of Seoul Urban Planning Park where citizens’ apartments were built. Source: It was reconstructed by the author with reference to the following literature. Survey Report of Substandard Housing, 1965 (research report to Seoul Metropolitan Urban Planning Commission). Citizen apartment Construction Master Plan, 28 February 1969 (official document of Seoul Metropolitan: No. 770-366). The City is A Line: Mayor Kim Hyeon-Ok. 2016 (brochure to Seoul Museum of History) [55]. The Masterplan of Seoul Urban Planning Park, 1968 (research report to Seoul Metropolitan).

The civic apartment construction plan, which emerged as part of the substandard building removal plan, proceeded at such a fast rate that 320 buildings were completed by July 1969, and Mayor Kim Hyun-ok tried to build 2000 buildings (90,9009 apartment units) by 1971. However, the project was discontinued on 8 April 1970 when a citizen’s apartment at Wow Park collapsed (Dong-A Daily, 8 April 1970). As a result, 17,402 apartments units in 434 buildings were built in 32 districts over the course of three years.

There were 15 parks at the site where the civic apartments were built. The Seoul Metropolitan Government first constructed an apartment at the park site and then applied to the Ministry of Construction in August 1968 to convert a park area consisting of 457,494 m2 into a landscape area and residential land where housing can be constructed. The Ministry of Construction approved the lifting of the restrictions of a total of 456,894 m2 in February 1971 (Table 2).

In the wake of the Wow apartment collapse, the Ministry of Construction said in September 1970, “Regarding the request for lifting the park designation for the purpose of building an apartment…. they deny such request.” [Partial Changes to Seoul Urban Planning Park: Opinions of the 8th Central Urban Planning Commission, September 1970]. Until then, the construction of civic apartments focused on cleaning up unauthorized buildings in the park, which had nothing to do with park management and development. However, in February 1971, Jaeil Life Insurance, the largest company at that time, decided to build the last civic apartment at Jeonnong Park, and a new method of developing a park of a size of 4941 m2 and donating was proposed [Seoul Urban Planning Park-Jeonnonong Park-Party Change No. 415-2636, February 1971].

3.2. Private Park Special Project, 2009

3.2.1. Agent: Limitations of Public Development and Expansion of Private Project Promoters

- ○

- Limitations of public development and the start of private sector development

As mentioned above, the government’s land development in the early days of the Republic took public development as its principle, and private development proceeded in a very limited way. This was especially the case for parks since private rights were limited at parks. In developing a park, the government was the primary supplier by buying raw land and developing it, and through a public offering, the government appointed private business operators to install structures(s) [60]. In this way, Seoul Mayor Kim Hyun-ok built civic apartments in the parks, but the financial burden was a problem to overcome. During Mayor Kim’s tenure, construction costs accounted for more than 75% of both general and special accounts. [Seoul Statistical Yearbook 1961–1970]. As a result, he opened the door to private capital and private-led development, arguing that it was time to change the concept of what a budget is in order to overcome the financial burden of construction projects. At that time, this was not a familiar method in Korea, but he argued that it was necessary to establish a reasonable urban development plan by considering capital and capabilities comprehensively rather than neglecting rapid urban growth due to lack of finances [61].

- ○

- Expansion of private development projects

With the 10 June Democratic Uprising in 1987 and the election of the democratically elected president in 1993, the basic direction of the legal system and policy of the Republic of Korea shifted to deregulation. Thus, the policy on private equity projects shifted from a passive attitude to an active one. In 1994, the Promotion of Private Capital into Social Overhead Capital Investment Act was enacted by the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea. The law paved the way for private developers to directly accommodate private land within the project target site, albeit in a limited way, so that government finances could be reduced. To preserve investments and promote the operation of private firms, additional projects could be implemented [Promotion of Private Capital into Social Overhead Capital Investment Act, 1994. §18 and §20].

In 2000, the government enacted the Urban Development Act to “use private capital and technology” for urban development projects [Urban Development Act (draft) proposal, December 1999. Official Document of National Assembly Committee on Construction and Transport]. The Government took the following measures to meet the demand for private sector projects through this Act: (1) The implementers were expanded to landowners, associations, private partnerships in Infrastructure Project Corporation, or private and public joint corporations. (2) Private corporations could also propose the designation of urban development zones with the consent of landowners who own more than four-fifths of the land area. (3) The method of implementation of the project could be selected from the method of expiration or use of land, the replotting method, or the combined method. (4) With the purchase of more than 2/3 of the project target land and the consent of more than 2/3 of the landowners, land expropriation rights could be granted. Thus, regulations were drastically eased, which were the necessary steps for easier execution of private projects in cities.

3.2.2. Structure: Neglected Parks and the 2020 Park Sunset Clause

- ○

- Urban parks that were not constructed for a long period of time

In the 1960s and the present day, neglecting parks in the city without creating them has long been a big social problem in Korea. The main cause of the parks being neglected was due to the growing financial burden of local governments in creating a park. In 2008, when the area of neglected parks was the largest, a government budget of 58.55 trillion won was needed to create the neglected parks. This amount was about 32% of the main budget of the government of Korea at that time.

The reasons why the parks had not been created for a long time are as follows: (1) due to the high proportion of private properties in the parks, the increase in compensation costs and the lack of financial resources due to the increase in buildings; (2) irrational existing park plans, such as intensive park placements at the outskirts of the city, difficult topographical conditions to create parks, and loss of value due to the closeness to adjacent parks; (3) delayed park construction due to the failure of urban development projects being executed, delayed location and relocation of other public facilities, and the concentration of unauthorized buildings [62,63].

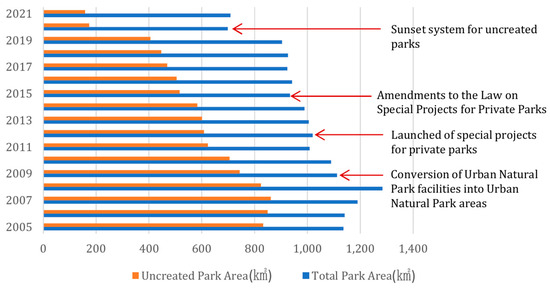

For this reason, it was not uncommon for parks designated in the Japanese colonial era to not be built even 60 years later. Looking at the status of the urban park area, in which the recordkeeping started in 1972, there was little difference between the planned parks (474.8 km2) and the non-constructed parks (428.5 km2), and only 9.7% of the parks were actually created [Korean Urban Yearbook, 1972]. Official Statistics Data to Ministry of Home Affairs]. In 2008, the planned park area (1284.5 km2) reached its peak by increasing to three times the statistic from 1972, and uncreated parks (860.6 km2) doubled in area instead of decreasing [41]. However, since 2008, the area of uncreated parks has decreased to 158.1 km2 in 2021 with the implementation of the sunset clause in 2020 (Figure 5). Due to such an active policy aiming to reduce uncreated parks, park creation rate in the city has reached 80.2%.

Figure 5.

Current status of uncreated Urban Planning Park 2005–2021. Source: It was reconstructed by the author with reference to the following literature. Current Status of Unexecuted Urban Planning Facilities (official statistics data to Korea Land and Geospatial Informatix Corporation) [64]. Current Status of Urban Planning Facilities (official statistics data to Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport) [65].

- ○

- A Law taking effect to remove the park status of uncreated parks in 2020

After 1990, the government began to show interest in guaranteeing individual property rights. Due to the influence of the laws enacted during the Japanese colonial period, the use and sale of privately owned land designated as parks were restricted. Until the land was put into use, no compensation was given for the restrictions on property rights. Until 2000, the Korean law did not set a specific period for the freezing of land assets, so the construction of the parks could be postponed indefinitely and the restrictions on land property rights could be extended indefinitely. In October 1999, the Constitutional Court ruled that long-term, non-executed urban planning facilities were unconstitutional due to the imbalance between public interest and private interests regarding urban planning facilities or parks. In January 2000, the government decided to introduce a sunset clause for uncreated parks on 1 July 2020 [Urban Planning Act, 2000. §41; Urban Park Act, 2000. supplementary provision]. Since there is no preliminary judgment such as whether to lift restrictions or preserve a park, the sunset clause “automatically removes regulations after a specified period unless renewed.” Regarding the sunset clause for uncreated parks, Korea’s Constitutional Court ruled that the decision was aimed at breaking down the measures that had been carried out without careful consideration of feasibility, business feasibility, and financial resources in the name of administrative convenience [Constitutional Court, 2007헌바110].

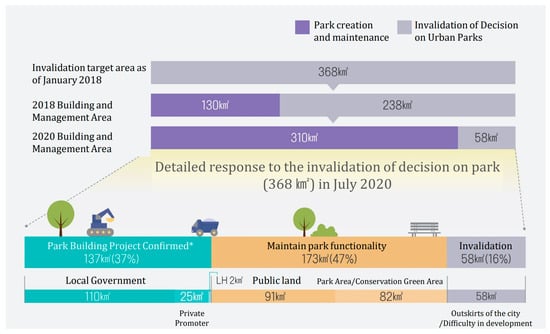

The Government implemented a number of policies to make soft landings in preparation for the impact of the 2020 sunset clause (Figure 5). The policies for resolving the cancelation of a park’s construction and the policy for resolving uncreated parks, which centered on private projects, excluded the central or local government’s financial support. The specific policy is as follows. (1) In 2000, if the park was not built for more than 10 years, the landowner could request the local government to purchase the land [Urban Planning Act, 2000. §40; Urban Park Act, 2000. §8]. (2) In 2009, “Special case of private parks” was established to resolve the problem of long-term uncreated parks, such as by providing incentives to attract private capital, as most urban parks were left unattended for a long period of time due to poor financial conditions of local governments [Act on Urban parks and Grean Areas, 2009. §21-2] [66]. (3) In 2010, urban nature parks, which were widely located in suburban areas surrounding the city, were excluded from the statistics of uncreated parks, which was tracked and managed by the government [Act on Urban parks and Grean Areas, 2005. supplementary provision §6]. (4) Meanwhile, in 2014, there was no case of private capital creating parks, even though the law was introduced in December 2009. The law was created before the sunset clause regarding uncreated parks was implemented. Suwon City (Youngheung Park), Uijeongbu City (Jikdong Park, Chudong Park), and Wonju City (Central Park) were considering private park projects, but they said it would be difficult to execute their projects under the 2009 system. It was expected that the government would improve the special system for private parks to resolve the problem of long-term uncreated parks, in which the statutes for them would expire in July 2020, and the improvement would lure additional investments [67].

Due to the government’s active action, the area of uncreated parks has shifted to a decline since 2008, and there was a decline of 455 km2 of unconstructed park area in the park status statistics until 2019, the year before the sunset clause was implemented. In July 2020, the sunset clause was implemented for uncreated parks, which was an area equivalent to 368 km2. According to the latest statistics in 2021, only 158 km2 of the park area had not been built for less than 10 years (Figure 5).

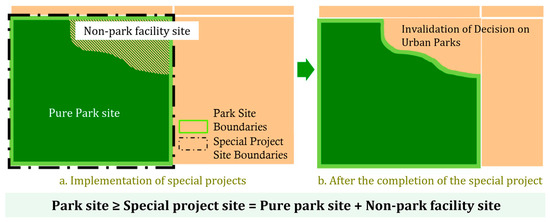

3.2.3. Organization: Special Cases Concerning Developing Activities in Site for Urban Parks

The government, ahead of the implementation of the sunset clause for uncreated parks, conducted a study on a special law that allows the private sector to create parks by guaranteeing maximum profits without introducing legislation. In December 2009, the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea revised the Act on Urban Parks and Green Areas (Act on Urban Parks and Green Areas, 2005) to provide incentives to actively attract private capital to park development. According to Article 21-2 of “Special Cases concerning Developing Activities in Sites for Urban Parks,” a private park promoter may develop an undeveloped park of 100,000 m2 or more if a park was created within more than 80% of the site area, and non-park facilities including apartments were built on less than 20% of the site, on the condition of non-payment of donations to the local government (Figure 6). Private park project promoters were able to exercise the right to expropriate land for private land in the park. The park development method was similar to urban planning or urban development, so it was possible to apply a replotting method that could exchange green areas in the park for land that could be built [68].

Figure 6.

Diagram of private park special project. Source: It was translated by the authors. A Study on the Participation of LH in the Building and Management of Urban Parks Unexecuted under the Special Use Permit (research report to Land and Housing Research Institute) [68].

In 2014, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport established guidelines for the invalidation of long-term unexecuted urban planning facilities, instructing local governments to classify parks of which the private sector will participate in developing and then lift park designation for areas where a project will not be implemented [69]. Then, as a follow-up measure, the government revised Article 21-2 of this Act to ease the burden on private park project promoters. Typically, the area of the target site where the project is possible was lowered to more than 50,000 m2, and the area where non-park facilities can be constructed was raised to less than 30%. In addition, administrative procedures were simplified, and private park project promoters could prepare park creation plans and propose projects themselves.

3.2.4. Discourse: Characteristics and Problems of the Implementation of Private Parks Special Projects

- ○

- Quantitative contribution and characteristics of private parks

As of 2018, the law was planned to take effect on 368 km2 of park area, which has been left unattended for more than 10 years. The government made efforts to maintain the function of parks or create parks to minimize the effect of the law taking place. First, the government prevented the law from taking effect on park lands of 91 km2 of state-owned land in 2019. At the same time, park areas with high elevation and steep slopes, which totaled to 82 km2, were set up as green belts or conservation green areas to maintain its function as a park even if the park status was invalidated [70] (Figure 7). The government created parks (650 locations) for 137 km2 to reduce the effects of the law taking place. Among them, 110 km2 was developed by local governments and 25 km2 by private park promoters. By 2020, the proportion of practical contributions of private parks to the effectiveness of parks accounted for 6.8% and 18.2% of the park’s construction area.

Figure 7.

Current status of long-term uncreated parks (results of measures for target sites to invalidation in July 2020). Source: It was translated by the authors. Long-term uncreated park site that will disappear as invalidation system, 84% protected (press release to Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. 18 June 2020) [71].

Currently, the special project for private parks, which creates parks instead of apartments on uncreated park areas, is considered to be much larger than the confirmed supply. As of June 2020, 65 private park special projects have received environmental effects evaluation (Table 3). The park area is 109.7 km2, of which the site area of non-park facilities is 26.3 km2. The government expects the construction of private park areas of 25.5 km2 with the use of private capital of 5.6 trillion won (about 4.02 billion dollars) by 2023 [70].

Table 3.

Ratio of non-park facility area of private park special projects by local government (2020).

During the promotion of this special project, it was revealed that most projects were carried out in areas heavily influenced by the real estate market, such as the Seoul Capital Area (Gyeonggi-do, Incheon). However, the Seoul Metropolitan City, which has very high land compensation costs, was excluded. In response, the Seoul Metropolitan Government said, “In principle, we are opposed to converting even some of the existing parks to non-park use,” and added, “There is no suitable park site for this project” [Maeil Economy, 25 August 2019]. By conducting income and expenditure analysis on the compensation value and market value for Seoul’s uncreated parks in 2013, Seoul Metropolitan Government expected that it would be difficult for private project promoters to realize the benefits due to excessively high land prices [72].

Meanwhile, non-park facility sites that damage the park land accounted for an average of 21.4%. In particular, the average area of apartment construction in parks was lower in southern regions such as Busan and Gwangju. This was because local governments, experts, and civic groups gathered together to fully discuss the location and area of non-park facilities in the process of executing the project, rather than the physical characteristics of the region. Through such governance, it was possible to preserve areas with excellent ecosystems and minimize social conflicts that could occur in the process of implementing projects [71].

- ○

- Concerns about private parks

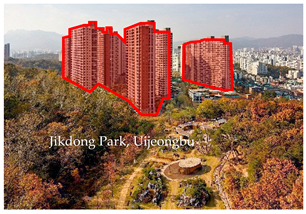

Even before the establishment of the system for private parks, the following concerns have been raised. First, the erosion of the park’s green space. Starting in 2020, when the regulation against long-term uncreated parks became effective, it was thought that park spaces would lose their functions as parks, and many feared there would be reckless development on private land in the park. The private park system also allowed development activities on some of the park sites, resulting in a decrease in the existing park area. In particular, the special project for private parks was carried out as a high-rise apartment project because the project considered maximizing the profit. However, such execution was difficult due to opposition from local residents and opposition from the Urban Park Committee. Due to environmental and landscape problems with the parks, a total of six projects, including Gwangyo Park in Incheon, Jungang Park, and Mandeok Park in Busan, were canceled. A total of six parks, including Huimang Park in Incheon, Myeongjang Park in Busan, and Onseok Park in Seosan, were put on hold due to lawsuits by local civic groups. In the case of Uijeongbu’s Jikdong Park, where the private park special project was first carried out, the park areas that were part of the contributed acceptance were planned as ecological and rest-type parks, but in 2015, the project promoter added more than 20 tennis courts and stadiums as a profit-making venture in the park’s mountainous area [73], raising concerns from local residents.

Second, it was difficult to ensure the continuity of the project due to complex relationships other than park creation. The local government, which is the operator of the project, is involved in overall policies such as evaluating project performance ability, estimating project costs, and managing the contents of park creation plans. Since the project is based on the Act on Urban Parks and Green Areas, it is difficult to discern which government is responsible for the projects. As a result, it required expertise in both developing projects and on park green areas. However, there were no specific guidelines or precedents for the project, and the current legal structure and organizational system did not have guidelines either. Hence, it was difficult to execute the projects smoothly [74]. For this reason, a total of 35 special private park projects were suspended by 2021. Looking into the details, 9 cases were rejected during the administrative process after the private firms participated in the project, 23 cases were abandoned due to lack of business feasibility, and 3 cases were suspended for litigation and other reasons [75].

4. Discussion

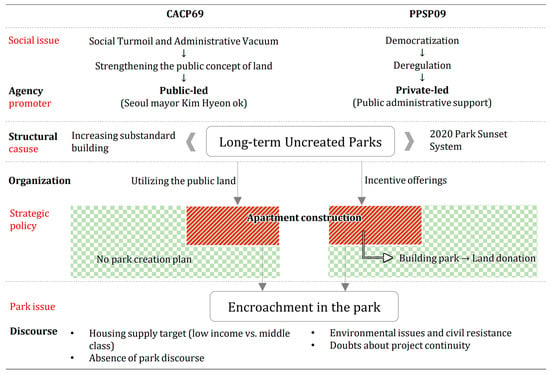

This study examined policies related to apartment construction in parks through the PAA framework, focusing on causes, policy changes, and mechanisms. The CACP69 of the late 1960s relied on strong public authority to address administrative vacuums after independence and the Korean War, with Seoul Mayor Kim Hyun-ok as the central actor. In contrast, the PPSP09, introduced in the 2000s, required private capital and technological capacity, reflecting democratization and deregulation trends of the 1990s, with government reforms supporting private participation (as shown in Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of PAAs for CACP69 and PPSP09 Cases.

Two structural causes underpinned housing in parks: the need to supply housing by reorganizing illegal constructions and the necessity of addressing long-term unexecuted parks under the sunset clause. CACP69 emphasized housing supply, while PPSP09 prioritized rapid park creation. Organizationally, the former lifted park status to allow apartment construction, whereas the latter incentivized private developers with profits from housing sales to fund park creation.

Discursively, CACP69 presented the issue as one of community housing supply while excluding park concerns, whereas PPSP09 acknowledged environmental issues and park erosion from high-rise construction. Both cases revealed that private capital and technology became instrumental in park development, with institutional mechanisms balancing private and public interests. Ultimately, the intersection of CACP69 and PPSP09 lies in the long-term uncreated parks—used first for housing supply and later as a means to resolve park deficits—highlighting the need for a deeper discussion on park management policies that enable housing within park spaces.

4.1. The Impact of the Construction of Apartments in Parks on the Park Green Space Policy

CACP69, which built citizen apartments on park sites, contributed to solving housing shortages in the short term, but in the long run, it had a significant impact on Seoul’s park green space policy and urban structure. As urban parks were diverted to residential areas, rest and ecological functions were lost, which fixed the gap in urban green spaces. As a result, the policy relied on the expansion of large parks on the outskirts rather than neighborhood parks in the living area, and citizens’ daily access decreased. In addition, as parks were recognized as ‘reserved land’ that could be used rather than independent protected objects, their release and diversion were repeatedly justified, and development methods linked to private capital strengthened the tendency to emphasize profitability rather than publicity. In the end, the construction of citizen apartments solved the housing shortage and at the same time converted parks and green spaces into land resources, leaving structural problems that continue to this day.

PPSP09 has made a certain contribution to the conservation and expansion of park supply, but at the same time, it has revealed various problems. Through this system, some long-term undeveloped parks have been secured nationwide, and large-scale park construction has become possible in a short period of time by reducing the financial burden on local governments. However, publicity has been weakened as parks have lost their original public good nature and are recognized as land that can be exchanged for private development. Most of the non-park facilities have been uniformly converted into apartments, which has resulted in the park green space policy being subordinated to the logic of housing supply. In addition, it was mainly promoted in large cities with high business potential, which caused equity issues between regions, and social conflicts such as preferential treatment controversies and opposition from residents were frequent in the process of selecting business operators. In the end, PPSP09 contributed to the conservation of parks in the short term, but in the long term, it left structural problems that subordinated the park green space policy to the logic of real estate development.

4.2. Comparison and Limitations with Similar Policies in Japan

As mentioned in the previous introduction, the birth of parks and land overlaps with houses have an innate relationship. Unlike naturally occurring unlicensed houses in Korean parks in the 1950s~1970s or Tijuca park [76] in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in the 1990s, building houses in parks as a government policy is a rare phenomenon worldwide since the establishment of the Regent park in the United Kingdom. In particular, in South Korea, the collapse of the Wow apartment building built with CACP69 created great trauma, and the construction of apartments in the park was restricted until PPSP04 was implemented.

On the other hand, Japan has an urban issue about undeveloped parks like Korea, and to solve it, it has promoted the construction of houses in parks ahead of Korea. Because of this, South Korea’s PPSP09 was able to benchmark Japan’s Private Development Parks (PDP04) in 2004. Both policies aim to encourage private operators to get involved in developing parks that have been left uncreated for an extended period. However, Japan’s PDP04 is designed to ensure the public interest of the park. The main features are that the target park must be designated as an evacuation site in the local disaster prevention plan, and the private operator must pay the management fee of the park [30,77]. On the other hand, PPS09, which is the case of this study, allowed high construction density for non-park facilities and allowed profit-making facilities to be built and operated.

On the other hand, the differentiated policy design of both countries also affected their policy performance. Only one park (Hygiyama Park) was created by PDP04 in consideration of public interest. However, PPSP09 has 65 projects scheduled in Korea (see Table 3) thanks to sufficient incentives given to private project promoters. As we have seen in this case, we can recognize the long-term neglect of park creation as a public goods issue, and in order to promote projects by the private sector, active administration by the government is required to ensure their interests first (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the scale of private development between PPSP09 in Korea and PDP04 in Japan.

4.3. Property Rights-Oriented Park Management Policy Revealed in the Uncreated Park

It takes quite some time to partition the land needed for parks and to install park facilities. If private land is included in the land determined for park use, the landowner would not be able to change the use of the land or receive compensation from the government until the park was created. These regulations have been in effect since the Japanese colonial period and have been put in place in the Korean society for a long time. Since the period for landowners to endure was not stipulated, the period of restriction on property rights was unlimited until 2000. Therefore, it was difficult to exercise property rights on these lands for up to three generations. Due to the expansion of cities and the quantitative expansion of the planned parks, the number of landowners whose rights were limited had increased. For this reason, the balancing of public interest and private interest has long been discussed as an important issue in urban planning and park planning [62]. In order to balance the two interests, the courts stated that the exercise of property rights by individual(s) is a specific judicial right in the case related to park development, which was underway with the participation of the private sector (Supreme Court No.자94마2218).

“In theory, parks are for everyone.” However, people experience parks differently, depending on both the individual and the park itself, but when private land is opened to citizens as a park, park users remain aware that such space is owned by individuals [78]. Park erosion caused by CACP69 or PPSP09 was due to the process of ownership or privatization by selling public spaces. For the spaces that were scheduled to be used as a park, the existing landowner gained an opportunity to be compensated. And a new property owner had exclusive monopoly over the usage of the land, encouraging the pursuit of profits and sale of the property [79]. If parks could not begin construction for a long period of time, spaces in the public domain would eventually be consumed and become fragmented and decrease over time [80,81]. This trend is based on the institutional design formed by the accumulated experience of the country.

The solid relationships between publicization and privatization exclude community members from participating in park planning, operation, and management, and prevent them from feeling a sense of community and ownership of the parks. The Korean judiciary also made it clear that local residents or communities are not stakeholders in the park projects (Supreme Court 자94마2218). When CACP69 took place, it was before governance took place in Korea. However, even with the advent of PPSP09, participation of local communities was mostly excluded. PPSP09 implemented in Gwangju and Busan, which was mentioned above, was able to minimize the area of park erosion by non-park facilities, in comparison to other park projects in other regions, due to the participation of local communities. The attitude in which park management policy was carried out in resolving the tragedy of neglected parks was through administrative power, land expropriation, and landowners having the ability to compensate and develop.

4.4. Lack of Legal Definition for Parks and Ambiguous Concept

Helen Littke [23] saw that the conflict arising from the proposition of “parkification of nature, urbanization of parks” stems from an ambiguous concept of parks. Many people believe that parks and nature are the same, but they fail to appreciate the distinction. The ambiguity of these concepts follows a myriad of relationships, which include everyday practice and professional language, legal and functional contexts, urban design technical description and maintenance concepts, and changing perceptions of parks over time. Depending on how one defines a park, a focus on high density reflected in plans and policies causes complex conflicts within urban green spaces.

The concept of parks in Korea is also not clear. As mentioned earlier, the initial legal definition of a park was “park and green area installed as a facility for urban planning under the Urban Planning Act.” This definition was born out of precedence over institutional procedures and forms rather than following the meaning or function of the park. Meanwhile, scholars in Korea viewed the reasons for the neglect and erosion of parks during CACP69 as being caused by the confusion between what constitutes a park and a green area. Their logic is that government officials recognized parks as land that is frozen for development and a reserve for future development because they equated parks with green areas. In other words, the government’s park policy takes precedence over preserving the park itself for the purpose of reservation (or conversion) for other uses instead of imposing institutional regulations based on human preferences. For this reason, scholars suggested that the concept of parks should be prioritized over green areas, and they expected the creation of parks would actively induce citizens to use them [82,83,84]. Therefore, it can be said that the construction of civic apartments in the park during CACP49 originated from the attitude of bureaucrats who recognized parks as land reserved for other purposes.

So far, parks in Korea have followed the same footsteps as “the tragedy of the commons.” The development of apartment complexes within park areas reflects a fundamental deficiency in policy-makers’ attitudes and highlights the inadequacy of current urban planning policies, having narrowly interpreted what the public and private sectors are. Parks, which are public goods, were recognized as shared resources, such as reserves, in the policy process. Furthermore, there were chronic problems of congestion or abuse that did not appear in pure public goods.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzes the background of housing development in parks in Korea and its policy implications. First, the housing development in parks stemmed from structural factors such as rapid urban population growth, chronic housing shortages, and the accumulation of undeveloped parks that had been neglected for a long time. As such, parks were recognized as reserves for urban growth and housing supply rather than their original public goods, which were further exacerbated by administrative gaps and institutional loopholes.

Second, the park management policy has changed from the CACP69 in the 1960s based on authoritarian public power to the PPSP09 after the 2000s, which systematically guaranteed the participation of private capital. The former showed the difference in public-led compulsory development and the latter was profit-guaranteed development through private participation, but both periods had commonalities in that they used parks as a means of housing supply.

Third, the policy mechanism operated through the interaction of the four elements of the Policy Arrangement Approach (PAA)—actors, structures, discourses, and organizations. Actors moved from the public sector to the private sector, and the structural background was overcrowding, housing shortages, and the accumulation of undeveloped parks. At the discourse level, the justification of balancing public and private interests was emphasized, but in reality, the bureaucratic perception of parks as land that could be developed is dominant. Organizationally, it was institutionalized so that the park site could be legally diverted for housing development through laws and institutional mechanisms.

In summary, the construction of apartments in parks in Korea can be understood as not just a housing supply policy, but a series of processes that consume common land in the administrative neglect of park management and institutional structure. This is the result of weakening the publicity of parks and subordinating them to the logic of urban growth, suggesting that future park management policies need to be restructured around community participation and restoration of publicity.

As seen in the case of Korea, this study presents the following strategic implications for park management policies to minimize further erosion of parks.

- The concept presented in the park-related theories should be reflected in the legal definition. Especially in developing countries, the concept of parks should be legally established so that problems related to parks will not be passed on to future generations.

- If the concept of the park is legally clear, illegal occupation in the park can be blocked in advance. Particularly, illegal occupation by buildings not only makes it difficult to create a park, but such buildings can also become legal facilities that intrude in the parks in the future.

- It is necessary to clarify the completion time after securing the necessary budget at the park policy establishment stage to minimize the time gap between park planning and park creation. This would be the best way to prevent park encroachment.

- A three-prong structure should be formed in which members of the local community can directly participate, breaking away from the establishment of stakeholders centered on public institutions and landowners. This is a means to minimize environmental problems and residents’ resistance when developing parks. At the same time, this is a theory about parks that has been advocated since the birth of parks.

Author Contributions

The first author C.O. and the second author S.P. designed this study and wrote the manuscript jointly. C.O. collected data for conducting the study, provided a theoretical framework, and interpreted the results. S.P. was in charge of visualization, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Archives collected in connection with CACP69.

Table A1.

Archives collected in connection with CACP69.

| Category | Title | Source or Author | Year | Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official documents | The Japanese Government-General of Korea Notice No.208 | the Japanese Government-General of Korea. | March 1940 | Designated as Korea’s first park |

| Seoul Statistical Yearbook | Seoul Metropolitan | 1961–1970 | Current status of parks and green spaces in Seoul | |

| The Ministry of Construction Notice No. 524 | The Ministry of Construction | August 1963 | Apartment construction status in the park | |

| The Ministry of Construction Notice No. 187 | The Ministry of Construction | December 1962 | Apartment construction status in the park | |

| The Ministry of Construction Notice No. 174, | The Ministry of Construction | April 1970 | Apartment construction status in the park | |

| The Ministry of Construction Notice No. 56 | The Ministry of Construction | February 1971 | Apartment construction status in the park | |

| The Ministry of Construction Notice No. 108 | The Ministry of Construction | February 1971 | Apartment construction status in the park | |

| Partial Changes to Seoul Urban Planning Park: Opinions of the 8th Central Urban Planning Commission (No,1) | The Ministry of Construction | September 1970 | Decision to stop construction of apartments in the park | |

| Seoul Urban Planning Park-Jeonnong Park-Partial Change No. 415-2636 | The Ministry of Construction | February 1971 | Construction of the last citizen apartment in the park | |

| Policy Reports | The Masterplan of Seoul Urban Planning Park | Seoul Metropolitan | 1968 | Seoul Park and Green Space Plan |

| History of Seoul Metropolitan | Seoul Metropolitan | 1965 | Seoul Park and Green Space Plan | |

| Seoul Urban Planning | Seoul Metropolitan | 1965 | Seoul Park and Green Space Plan | |

| The Basic Plan of Seoul Metropolitan | Seoul Metropolitan | 1966 | Seoul Park and Green Space Plan | |

| Construction Administrative Guidelines | Seoul Metropolitan | 1953 | Seoul Park and Green Space Plan | |

| The Past and Future of Seoul Urban Planning | Seoul Metropolitan | 1962 | Seoul Park and Green Space Plan | |

| Substandard Buildings Removal Plan | Seoul Metropolitan Urban Planning Commission | 1965 | Plans to demolish unauthorized buildings in the park | |

| Citizen Apartment Construction Masterplan | Seoul Metropolitan | 1969 | Planning for the supply of citizen apartments and the construction of apartments in the park | |

| law | Chosun Planning Ordinance for Urban Area | the Japanese Government-General of Korea. | 1934 | Necessary regulations regarding the creation, management, and use of parks |

| Urban Planning Act | National Assembly of Korea | 1961 | Necessary regulations regarding the creation, management, and use of parks | |

| Park Act | National Assembly of Korea | 1967 | Necessary regulations regarding the creation, management, and use of parks | |

| Enforcement Decree of Park Act | National Assembly of Korea | 1967 | Necessary regulations regarding the creation, management, and use of parks | |

| Enforcement Regulation of Building Act | National Assembly of Korea | 1965 | Necessary regulations regarding the creation, management, and use of parks | |

| Research papers, etc. | Park Byung-Joo’s ‘New Seoul Blank Plan (1966)’ in the Context of South Korea’s Urban Design during 1960–1970s | Um, W.J.; Jung, I.H. | 2020 | The construction process of citizen apartments in the park and the discourse at the time |

| A Study on the 1960s’ Seoul Pilot Projects—Based on Archives from the Asia Foundation Records 1951–1996. | Kang, H.Y. | 2020 | The construction process of citizen apartments in the park and the discourse at the time | |

| The City is A Line: Mayor Kim Hyeon-Ok | Seoul Museum of History | 2016 | The direction of the mayor’s park and green space plan in Seoul | |

| Newspapers | News·Seoul | 15 October 1956 | Government policy to allow the construction of houses in the park | |

| Dong_A | 13 July 1956 | Government policy to allow the construction of houses in the park | ||

| Dong_A | 13 August 1956 | Government policy to allow the construction of houses in the park | ||

| Kyunghyang | 6 February 1965 | Seoul’s population explosion | ||

| Dong_A | 8 April 1970 | Apartment collapse accident in the park |

Table A2.

Archives collected in connection with PPSP09.

Table A2.

Archives collected in connection with PPSP09.

| Category | Title | Source or Author | Year | Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official documents | Current Status of Unexecuted Urban Planning Facilities | Korea Land and Geospatial Informatix Corporation | 2005–2021 | Status of unexecuted parks |

| Current Status of Urban Planning Facilities | Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport | 2005–2021 | Status of planned parks and development parks | |

| Korean Urban Yearbook | Ministry of Home Affairs | 1972 | Status of planned parks and development parks | |

| Long-term uncreated park site that will disappear as invalidation system, 84% protected. | Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport | 2020 | Current status of long-term uncrated parks | |

| Private Capital Park Development Promotes “Increasing Revenue and Simplifying Procedures”: Announcement of Administrative Proposal to Amend Guidelines on Special Cases for Development of Urban Park Sites | Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport | 2014 | Guidelines for the release of long-term uncreated parks and PPSP09 implementation criteria | |

| The central and local governments, public institutions, and civic organizations work together to protect the lungs of the city | Government Organization of the Republic of Korea | 2018 | Governance organization for PPSP09 implementation | |

| Policy Reports | Urban Development Act (draft) proposal | National Assembly Committee on Construction and Transport | 1999 | Regulations related to housing development in the city |

| Guidelines for Invalidation of Long-term Unexecuted Urban Planning Facilities | Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport | 2014 | Guidelines for the release of long-term uncreated parks | |

| Analysis of the status of environmental impact assessment of private park special projects | Korea Environment Institute | 2020 | PPSP09 Plan Status | |

| A Study on the Participation of LH in the Building and Management of Urban Parks Unexecuted under the Special Use Permit | Land and Housing Research institute | 2016 | Study of PPSP09 Implementation Guidelines | |

| Law and precedent | Promotion of Private Capital into Social Overhead Capital Investment Act | National Assembly of Korea | 1994 | Act on Promotion of Investment by Private Capital for Public Utilities |

| Urban Development Act | National Assembly of Korea | 2000 | Sunset regulations for long-term uncreated parks | |

| Urban Planning Act | National Assembly of Korea | 2000 | Sunset regulations for long-term uncreated parks | |

| Urban Park Act | National Assembly of Korea | 2000 | Sunset regulations for long-term uncreated parks | |

| Act on Urban parks and Grean Areas | National Assembly of Korea | 2005, 2009, 2014 | Sunset regulations for long-term uncreated parks and amendments to the Law on PPSP09 | |

| 자94마2218 | Supreme Court | 1993 | Precedent that property rights take precedence over the public interest of parks | |

| 97헌바26 | Constitutional Court | 1999 | Precedent that property rights take precedence over the public interest of parks | |

| 2007헌바110 | Constitutional Court | 2007 | Legal Purpose of the Sunset System for Uncreated Parks | |

| Research papers, etc. | A Simulation to Estimate the Applicability of Special Use Permit Policy to Seoul Park System | Jang, N.J.; Kim, J. | 2013 | Challenges in the application of PPSP09 in Seoul |

| Issues related to the public and private interests of park creation through private participation | Yoon, E.J. | 2016 | PPSP09 Implementation and issues | |

| A Study on the Characteristics of projects Following the Promotion of Private Park Special Projects. | Gweon, Y.D.; Park, H.B.; Kim, D.P. | 2021 | PPSP09 Policy characteristics | |

| Newspapers | Mail Economy | 25 August 2019 | Challenges in the application of PPSP09 in Seoul |

References

- Eisenman, T.S. Frederick Law Olmsted, Green Infrastructure, and the Evolving City. J. Plan. Hist. 2013, 12, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chan Michael, W.H. Urban Greenspace Delivery in Hong Kong: Spatial-Institutional Limitations and Solutions. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, E.; Northridge, M.E.; Metcalf, S.S. Integrating Grey and Green Infrastructure to Improve the Health and Well-Being of Urban Populations. Cities Environ. 2012, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Coutts, A.M.; Livesley, S.J.; Williams, N.S.G. Decision Principles for the Selection and Placement of Green Infrastructure to Mitigate Urban Hotspots and Heat waves. In Victorian Centre for Climate Change Adaptation Research; University of Melbourne and Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mell, I.C.; Henneberry, J.; Hehl-Lange, S.; Keskin, B. Promoting Urban Greening: Valuing the Development of Green Infrastructure Investments in the Urban Core of Manchester, UK. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuzere, D.; Orru, K.; Heidrich, O.; Olazabal, E.; Geneletti, D.; Orru, H.; Bhave, A.G.; Mittal, N.; Feliu, E.; Faehnle, M. Mitigating and Adapting to Climate Change: Multi-functional and Multi-scale Assessment of Green Urban Infrastructure. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; James, P. Promoting Ecosystem and Human Health in Urban Areas Using Green Infrastructure: A Literature Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, P.; Sanderson, D. Healthy Cities Indicators: A Suitable Instrument to Measure Health? J. Urban Health 2013, 90 (Suppl. 1), 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landscape Institute. Green Infrastructure: Connected and Multifunctional Landscapes, Position Statement. 2009. Available online: https://landscapewpstorage01.blob.core.windows.net/www-landscapeinstitute-org/2016/03/GreenInfrastructurepositionstatement13May09.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Birkmann, J.; Garschagen, M.; Setiadi, N. New Challenges for Adaptive Urban Governance in Highly Dynamic Environments: Revisiting Planning Systems and Tools for Adaptive and Strategic Planning. Urban Clim. 2014, 7, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, I.; Goode, D.; Houck, M.C.; Wang, R. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alvey, A.A. Promoting and Preserving Biodiversity in the Urban Forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Davies, C.; Sanesi, G.; Konijnendijk, C.C. Green Infrastructure as a Tool to Support Spatial Planning in European Urban Regions. iForest-Biogeosciences For. 2013, 6, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In Merrian-Webster.com. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/park (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Checker, M. Wiped Out by the “Greenwave”: Environmental Gentrification and the Paradoxical Politics of Urban Sustainability. City Soc. 2011, 23, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]