Co-Evaluating Landscape as a Driver for Territorial Regeneration: The Industrial Archaeology of the Noto–Pachino Railway (Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Uganda Railway Heritage (Kenya): the establishment of the Uganda Railway Museum in Mombasa illustrates how transport heritage can foster cultural tourism and community education [103].

- -

- China: in cities such as Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai, obsolete railway corridors have been transformed into greenways and cultural parks integrating ecological design, heritage preservation, and slow mobility [20].

- -

- Semmering Railway (Austria): completed in 1854 and listed as UNESCO World Heritage (1998), it exemplifies the integration of engineering innovation with Alpine landscape values [44].

- -

- Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (India): recognized for its Outstanding Universal Value, it operates as a living heritage system where transport, tourism, and community coexist [46].

- -

- Rhaetian Railway in the Albula/Bernina Landscapes (Switzerland/Italy): a transboundary case highlighting cross-border cooperation and sustainable heritage management [45].

- -

- Trans-Iranian Railway (Iran): listed by UNESCO in 2021, it demonstrates how industrial heritage can narrate modernization processes across cultural and environmental gradients [104].

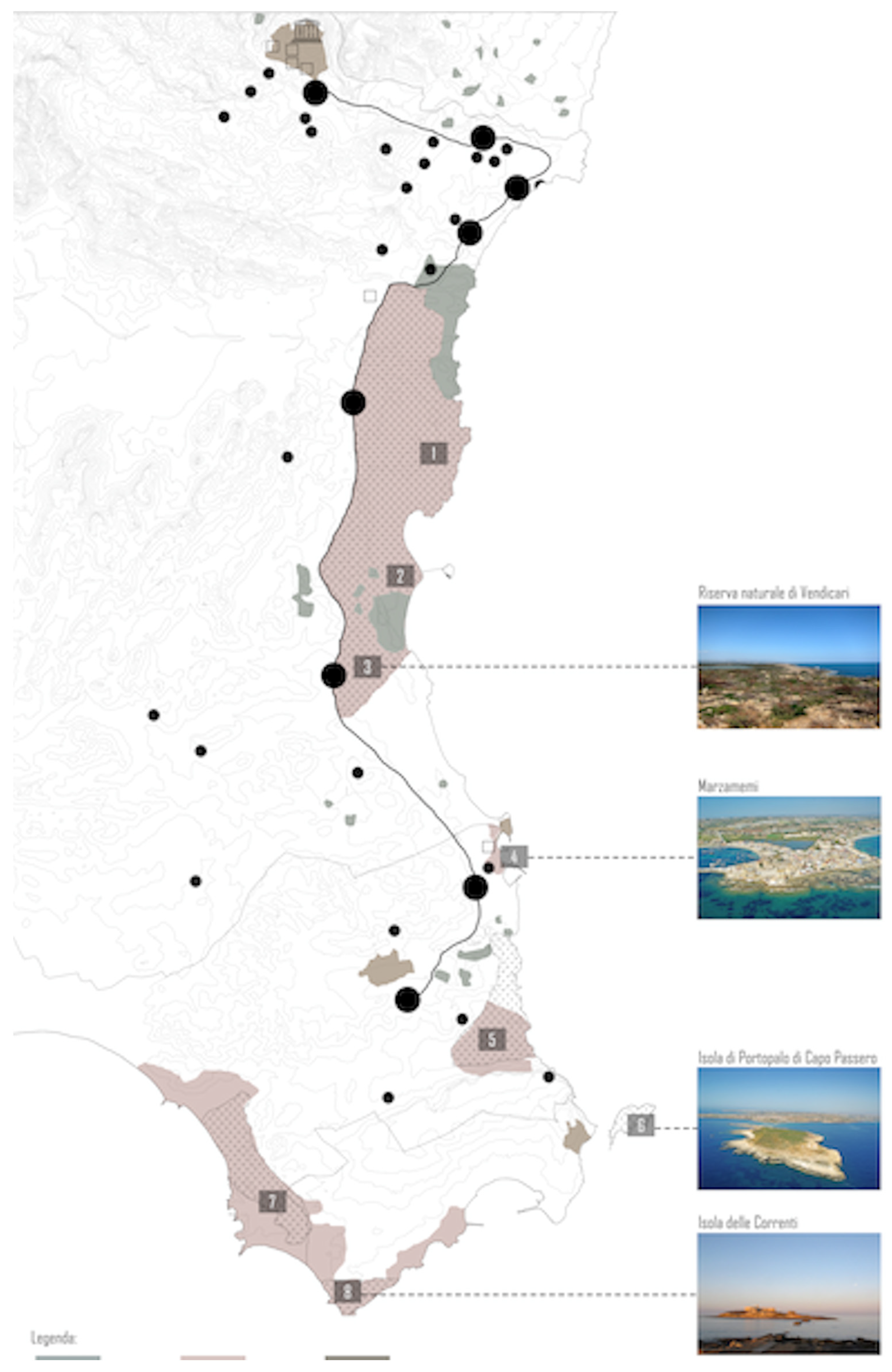

3. Case Study

- Historical and identity value: it reflects twentieth-century infrastructure policies and the effort to connect agricultural hinterlands with coastal towns. The railway’s memory remains alive in the collective consciousness of local communities.

- Landscape value: the line passes through high-quality agricultural, natural, and coastal landscapes, providing a continuous perceptual corridor linking urban, rural, and environmental areas.

- Social and economic value: disused stations and signal boxes represent tangible assets that could be repurposed for new uses, such as dispersed hospitality, cultural spaces, or environmental education centers. Conversion into a greenway or cycling route could stimulate local micro-economies and experiential tourism.

- Intangible and community value: the railway preserves social practices, memories, and narratives that strengthen a sense of belonging and could support territorial storytelling and heritage community initiatives.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Co-Formulation of Research Questions

- Thematic focus groups with citizens, local committees, and associations.

- Semi-structured narrative interviews with key informants, such as former railway workers, farmers, and local activists.

- Exploratory questionnaires distributed during community events.

- Participant observation in informal settings, including fairs, markets, and local gathering spots.

- Researcher field journals for recording insights, emotions, and cognitive dissonances.

- A preliminary mapping of perceived problems and available resources.

- Emergence of local “visions of the future,” including divergent perspectives.

- Building trust and fostering openness to collaboration.

4.2. Participatory Exploration of the Context

- Walkscape and exploratory walks: walking along the former railway path, guided by local experts—long-time residents, farmers, hunters, and local activists.

- Participatory mapping: collecting experiential data through mental maps, sketches, geo-referenced notes, and photographs to identify “hotspots” and critical points.

- Workshops and visual laboratories: producing interpretative materials such as thematic maps, collages, photo-stories, and infographics to support discussion.

- Listening tables with institutional and technical stakeholders.

- Identification of the railway’s landscape, symbolic, and emotional values.

- Emergence of latent conflicts between different visions for development.

- Production of shared, narrative accounts of the landscape and its transformations.

4.3. Building Territorial Laboratory

- Permanent territorial laboratories, conceived as open coordination and communication hubs.

- Thematic tables focusing on slow mobility, landscape, culture, agriculture, and tourism.

- Scenario simulations with physical or digital models (maquettes, GIS maps, digital platforms).

- Community agreements or “cooperation pacts” among stakeholders.

- Landscape Values Charter, collectively constructed to guide shared principles.

- Co-definition of project priorities.

- Clarification and negotiation of conflicts.

- Consolidation of a local coalition for change.

4.4. Experimentation and Field Action

- Activation events, such as railway memory days, cycling tours, and cultural walks.

- Temporary and tactical uses, for instance, small gardens along the tracks, stations repurposed as cultural hubs, and artistic installations.

- Co-designed activities with local associations and schools.

- Crowdmapping and participatory digital platforms to document the initiatives.

- Generation of visible and measurable effects on both the landscape and collective perception.

- Strengthening of local self-organization capacities.

- Field testing of the feasibility and sustainability of the shared strategies.

4.5. Co-Evaluation and Re-Learning

- Collective logbooks (written or audio) to capture experiences and reflections.

- Self-evaluation forms for participants.

- Public feedback sessions, where results were shared and discussed with the wider community.

- Qualitative and narrative indicators, such as change stories or relational metrics.

- Debriefing sessions between researchers and community members for co-creating new research questions.

- Assessment of tangible and intangible impacts generated by the process.

- Reformulation of strategies based on feedback received.

- Launch of a new action research cycle, built on stronger foundations and shared knowledge.

5. Results

5.1. Phase 1. Co-Creation of Research Questions

5.2. Results of Participatory Exploration of the Context

5.3. Construction of the Territorial Laboratory

5.4. Expected Outcomes—Experimentation and Field Action

5.5. Expected Outcomes—Co-Evaluation and Shared Learning

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Phase 1—Co-Creation of Research Questions (Completed)

Appendix A.1. Semi-Structured Narrative Interview Guide (Template)

| Section | Aim | Example Guiding Questions | Notes for Interviewer |

| 1. Personal background | Understand the informant’s connection to the territory | Can you describe your relationship with the railway or the surrounding landscape? | Allow free narration; prompt for memories or sensory descriptions. |

| 2. Collective memories | Explore shared cultural and emotional values | What memories do people in your community associate with the railway? | Use mapping aids (photos, old maps). |

| 3. Perceived challenges | Identify perceived barriers to reuse or enhancement | What are the main obstacles to reactivating the railway and its landscape? | Probe for institutional, social, or economic factors. |

| 4. Future visions | Collect ideas and aspirations | How do you imagine this railway in ten years? | Encourage creative and open responses. |

| 5. Collaboration and participation | Assess readiness for co-management | What forms of collaboration could you imagine between citizens, associations, and institutions? | Explore willingness to participate in collective actions. |

Appendix A.2. Exploratory Questionnaire

- -

- I feel emotionally attached to the railway and its landscape. → Mean: 4.3/5

- -

- I trust local institutions to manage heritage enhancement. → Mean: 2.8/5

- -

- I would be willing to participate in community maintenance or reuse projects. → Mean: 4.1/5

Appendix A.3. Preliminary Synthesis Report (Abstract and Analytical Framework)

Credit and Data Access Note

Appendix B. Phase 2—Participatory Exploration of the Context (Completed)

Appendix B.1. Walkscape Sheets (Fieldwork Documentation Template)

| Field | Description | Example Entry |

| Route Segment | Specific section explored along the Noto–Pachino line. | Noto—Testa dell’Acqua (rural segment, citrus fields). |

| Observers/Participants | Names and roles of contributors. | 10 participants (citizens, 2 researchers, 1 artist). |

| Spatial Observations | Notes on infrastructure, vegetation, accessibility. | Abandoned bridge over torrent, dry stone walls intact. |

| Emotional Perceptions | Keywords expressing affective reactions. | ‘Silence’, ‘memory’, ‘potential’. |

| Photographic/Sketch Records | Images or sketches linked to GPS points. | Photo 0321_Noto1.JPG—Old signage post. |

| Criticalities | Environmental, social, or infrastructural issues. | Illegal dumping near former station building. |

| Opportunities | Potential for reuse or enhancement. | Space suitable for rest area with educational panel. |

Appendix B.2. Participatory Mapping Outputs

Appendix B.3. Perception Survey Summary (Quantitative Indicators)

- Mean Landscape Attachment score: 4.5/5 (strong emotional bond).

- Perceived Accessibility: 2.9/5 (limited physical access, especially in northern sections).

- Perceived Reuse Potential: 4.2/5 (high interest in cultural and ecological reuse).

- 68% of respondents indicated willingness to participate in future co-design workshops.

- 57% identified the railway as a ‘landscape memory corridor’.

- Open-ended responses emphasized the need for soft mobility and environmental restoration.

Credit and Data Access Note

Appendix C. Phase 3 (Ongoing)—Building the Territorial Laboratory

Appendix C.1. Thematic Table Protocols (Draft Extracts)

- Thematic Laboratory 1—Slow Mobility and Cycle Tourism: Minutes of the meetings (June–August 2024); emerging priorities (signage system, greenway network, accessibility nodes).

- Thematic Laboratory 2—Landscape and Environment: Shared analysis grids and conflict-mapping notes regarding ecological corridors and agricultural landscapes.

- Thematic Laboratory 3—Culture and Railway Heritage: Draft of the Charter of Railway Landscape Values (first 10 shared principles).

- Thematic Laboratory 4—Local Economy and Agri-food Chains: Stakeholder mapping and cooperative scenarios for local product valorization.

- -

- 4 thematic tables activated, with an average of 12–15 participants per session.

- -

- 9 plenary meetings (June–September 2024).

- -

- 1 digital collaboration platform (Beta version, August 2024).

Appendix C.2. Charter of Railway Landscape Values (Working Draft)

- Section 1—Common Vision: “The railway landscape as a connective tissue between territories, memories, and communities.”

- Section 2—Guiding Principles: Care, reciprocity, transparency, adaptive reuse, and knowledge sharing.

- Section 3—Commitments: 10 collective commitments for stewardship and co-management, signed by 22 local actors (municipalities, associations, research institutions).

- Section 4—Implementation Tools: Cooperation pacts, participatory monitoring, and open data system for project updates.

- -

- Draft Charter published for consultation (September 2024).

- -

- 47 comments received via public online platform.

- -

- Consolidated version scheduled for public presentation (December 2025).

Appendix C.3. Digital Participation Platform—Beta Version Report

- Overview of the platform structure (interactive map, discussion forum, and document repository).

- Quantitative indicators: 125 registered users; 480 interactions recorded in the first three months.Preliminary feedback from usability survey:

- -

86% of respondents rated the interface as “useful” or “very useful”;- -

72% reported improved communication among working groups.

References

- Camagni, R.; Borri, D.; Ferlaino, F. Per un concetto di capitale territoriale. In Crescita e Sviluppo Regionale: Strumenti, Sistemi, Azioni; Borri, D., Ferlaino, F., Eds.; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2009; pp. 66–90. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Regional competitiveness and territorial capital: A conceptual approach and empirical evidence from the European Union. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy: A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations; Independent Report for the Regional Policy Commission; Economics and Econometrics Research Institute (EERI): Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, A. Alle origini dell’ingegneria ferroviaria in Campania: La costruzione della linea Avellino-Ponte S. Venere (1888–1895) e gli attuali problemi di conservazione. In Atti del 2° Convegno Nazionale Storia dell’Ingegneria; D’Agostino, S., Ed.; Cuzzolin Editore: Naples, Italy, 2008; pp. 1291–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M.; Parkinson, A.; Waldron, R.; Redmond, D. Planning for historic urban environments under austerity conditions: Insights from post-crash Ireland. Cities 2020, 103, 102788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Gabrys, J. Community-led landscape regeneration: A review of and framework for engagement in restoration initiatives. Ambio 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Bringing it all together—Taking care of the landscape. In Landscape Perspectives; Antrop, M., Van Eetvelde, V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 377–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaghi, A. Il Progetto Locale. Verso la Coscienza di Luogo; Bollati Boringhieri: Piemonte, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A. Montespertoli: Le Mappe di Comunità per lo Statuto del Territorio; Alinea Editrice: Florence, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, J.; Booher, D. Network power in collaborative planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2002, 21, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menatti, L. Landscape as a way of knowing the world: A philosophical perspective. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 758–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention). 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Jones, M.; Stenseke, M. (Eds.) The European Landscape Convention: Challenges of Participation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampa, F.; De Medici, S.; Viola, S.; Pinto, M.R. Regeneration criteria for adaptive reuse of the waterfront. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedata, L.; Altamura, P.; Rossi, L. Turning heritage railway architecture into an infrastructure for resilience and circularity: An opportunity for sustainable urban regeneration. In ETHICS: Endorse Technologies for Heritage Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L.; Lanteri, C. A collaborative multi-criteria decision-making framework for the adaptive reuse design of disused railways. Land 2024, 13, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, S. Le Ferrovie; Il Mulino: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Della Spina, L. Revitalization of inner and marginal areas: A multi-criteria decision aid approach for shared development strategies. Valori Valutazioni 2020, 2020, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, R.; Eizaguirre-Iribar, A.; García, J. From Railways to Greenways: A Complex Index for Assessing the Potential of Disused Railways for Sustainable Mobility. Transp. Res. Part D 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264837719320411 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Ristić, D.; Vukoičić, D.; Ivanović, M.; Nikolić, M.; Milentijević, N.; Mihajlović, L.; Petrović, D. Transformation of Abandoned Railways into Tourist Itineraries/Routes: Model of Revitalization of Marginal Rural Areas. Land 2024, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardi, R.; Cerreta, M.; Franciosa, A.; Gravagnuolo, A. Valuing cultural landscape services: A multidimensional and multi-group SDSS for scenario simulations. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2014; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C.M., Rocha, J.G., Falcão, M.I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferilli, G.; Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Forbici, S. Power to the people: When culture works as a social catalyst in urban regeneration processes (and when it does not). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, D. Il patrimonio territoriale fra capitale e risorsa nei processi di patrimonializzazione proattiva. In Aree Interne e Progetti D’area; Meloni, B., Ed.; Rosenberg & Sellier: Turin, Italy, 2015; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hutniczak, A.; Urbisz, A.; Watoła, A. The socio-economic importance of abandoned railway areas in the landscape of the Silesian Province (southern Poland). Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2023, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garramone, M.; Scaioni, M. A BIM/GIS digitalization process to explore the potential of disused railways in Italy. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Ma, H. Community Participation Strategy for Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Xiamen, China. Land 2022, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneklin, C.; Galuppo, L.; De Carlo, A. Dalla costruzione della committenza allo sviluppo dei committenti: L’avvio di una ricerca-azione. In La Ricerca-Azione Cambiare per Conoscere nei Contesti Organizzativi; Kaneklin, C., Piccardo, C., Scaratti, G., Eds.; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Milan, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saija, L. La Ricerca-Azione in Pianificazione Territoriale e Urbanistica; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Daldanise, G. Community branding (Co-Bra): A collaborative decision making process for urban regeneration. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2017; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Borruso, G., Torre, C.M., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Taniar, D., Apduhan., B.O., Stankova, E., Cuzzocrea, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10406, pp. 730–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Sustainable collaborative strategies of territorial regeneration: Learning from the Costa Viola case (Italy). Land 2023, 12, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Arts, J.; Vanclay, F.; Ward, J. Examining the social outcomes from urban transport infrastructure: Long-term consequences of spatial changes and varied interests at multiple levels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straatemeier, T.; Bertolini, L. How can planning for accessibility lead to more integrated transport and land-use strategies? Two examples from The Netherlands. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1713–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Strategic Planning and Decision Making: A Case Study for the Integrated Management of Cultural Heritage Assets in Southern Italy. In New Metropolitan Perspectives, NMP 2020; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaghi, A. Dalla partecipazione all’autogoverno della comunità locale: Verso il federalismo municipale solidale. Democr. E Dirit. 2006, 3, 134–151. [Google Scholar]

- Panaro, S. Landscape Co-Evaluation: Approcci Valutativi Adattivi per la co-Creatività Territoriale e L’innovazione Locale. Doctoral Dissertation, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Naples, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Della Spina, L.; Viglianisi, A. Hybrid evaluation approaches for cultural landscape: The case of “Riviera dei Gelsomini” area in Italy. In New Metropolitan Perspectives. NMP 2020; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettori, M.P. Common goods, cities, territories: Processes for the reactivation of disused public assets. TECHNE-J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2024, 28, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbanente, A.; Grassini, L. Landscape regeneration and place-based development in marginal areas: Learning from an Integrated Project in Southern Salento. City Territ. Archit. 2024, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L.; Giorno, C. Waste Landscape: Urban Regeneration Process for Shared Scenarios. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. Valuation of Industrial Heritage in Terms of Sustainability: Some Cases of Tourist Reference in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanedda, F. Post_production. Architectural design and the landscape of de-industrialisation. City Territ. Archit. 2023, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S.; Gattulli, V.; Landa, A.; Vannini, C. Protecting and Redeveloping Industrial Archaeological Heritage Through Design Strategies Driven by Digital Modelling. 2023. Available online: https://conservation-science.unibo.it/article/view/20083 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- UNESCO. Semmering Railway. 1998. World Heritage List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/785/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- UNESCO. Rhaetian Railway in the Albula/Bernina Landscapes (Switzerland/Italy). 2008. World Heritage List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1276/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- UNESCO. Mountain Railways of India (Darjeeling Himalayan Railway). 1999. World Heritage List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/944/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Esposito De Vita, G.; Trillo, C.; Martinez-Perez, A. Community planning and urban design in contested places: Some insights from Belfast. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anna, F. Multicriteria-decision support for master plan scheduling: Urban regeneration of an industrial area in Northern Italy. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2024, 42, 476–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L.; Carbonara, S.; Stefano, D.; Viglianisi, A. Circular Evaluation for Ranking Adaptive Reuse Strategies for Abandoned Industrial Heritage in Vulnerable Contexts. Buildings 2023, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settis, S. Il Paesaggio Come Bene Comune; La Scuola di Pitagora: Naples, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bonesio, L. Paesaggio, Identità e Comunità tra Locale e Globale; Diabasis: Parma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, J. The cultural values model: An integrated approach to values in landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, P. Planning at the Landscape Scale; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Onesti, A. Built environment, creativity, social art: The recovery of public space as engine of human development. Reg. J. ERSA 2017, 4, 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Huang, H. What is good action research? Why the resurgent interest? Action Res. 2010, 8, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. (Eds.) Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Inglese, P.; Malangone, V.; Panaro, S. Complex values-based approach for multidimensional evaluation of landscape. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2014; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C., Rocha, J.G., Falcão, M.I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8581. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Panaro, S.; Cannatella, D. Multidimensional spatial decision-making process: Local shared values in action. In Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F. Regenerative Streets: Pathways towards the Post-automobile City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.H. Securing Open Space for Urban America: Conservation Easements; Urban Land Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, A. Greenways as vehicles for expression. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J.; Fabos, J.G. Greenways as a planning strategy. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.S.; Hellmund, P.C. Ecology of Greenways: Design and Function of Linear Conservation Areas; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Searns, R.M. The evolution of greenways as an adaptive urban landscape form. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J.; Fabos, J.G. Greenways [Special Issue]. 1995. Landscape and Urban Planning, 33. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/landscape-and-urban-planning/vol/33/issue/1 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Fabos, J.G. Introduction and overview: The greenway movement, uses and potentials of greenways. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, A. Greenways and the making of urban form. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 81–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Xiang, W.N.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X. Incorporating landscape diversity into greenway alignment planning. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 35, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Li, D.; Li, N. The evolution of greenways in China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 76, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubisi, F.; DeMeo, T.; Ditto, N.D. Environmentally sensitive areas: A template for developing greenway corridors. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.M. Urban landscape conservation and the role of ecological greenways at local and metropolitan scales. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 76, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Haaren, C.; Reich, M. The German way to greenways and habitat networks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 76, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flink, C.A.; Olka, K.; Searns, R.M. Rails-to-Trails Conservancy. In Trails for the Twenty-First Century: Planning, Design, and Management Manual for Multi-Use Trails; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Flink, C.A.; Searns, R.M. Greenways: A Guide to Planning, Design, and Development, 1st ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Palardy, N.P.; Boley, B.B.; Johnson Gaither, C. Residents and urban greenways: Modeling support for the Atlanta BeltLine. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 169, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Nie, R.; Zhang, J. Greenway implementation influence on agricultural heritage sites (AHS): The case of Liantang Village, Zengcheng District, Guangzhou City, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.; Barão, T. Greenways for recreation and maintenance of landscape quality: Five case studies in Portugal. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 76, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, A.P.; Shannon, M.A. Building greenway policies within a participatory democracy framework. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, A. Author index. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 481–482. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; De Meulder, B.; Wang, S. Can greenways perform as a new planning strategy in the Pearl River Delta, China? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 187, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, C.; Jenkins, P. Place Identity, Participation and Planning; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Siderelis, C.; Moore, R. Outdoor recreation net benefits of rail-trails. J. Leis. Res. 1995, 27, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marino, M.; Tiitu, M.; Lapintie, K.; Viinikka, A.; Kopperoinen, L. Integrating green infrastructure and ecosystem services in land use planning: Results from two Finnish case studies. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; MacFarlane, R.; McGloin, C.; Roe, M. Green Infrastructure Planning Guide; North-East Community Forests: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mell, I.C. Can green infrastructure promote urban sustainability? Eng. Sustain. 2009, 162, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, J.; Gross, M.; Finn, J. Greenway planning: Developing a landscape ecological network approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, H. Regenerative cities. In Green Economy Reader; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Niemelä, J.; James, P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using green infrastructure: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Setälä, H.; Handel, S.N.; van der Ploeg, S.; Aronson, J.; Blignaut, J.N.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Nowak, D.J.; Kronenberg, J.; de Groot, R. Benefits of restoring ecosystem services in urban areas. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Barton, D.N. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Palomo, I.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Del Amo, D.G.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Palacios-Agundez, I.; Willaarts, B.; et al. Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Keith, S.J.; Fernandez, M.; Hallo, J.C.; Shafer, C.S.; Jennings, V. Ecosystem services and urban greenways: What’s the public’s perspective? Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 22, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.C.; Jellum, C. Rail trail development: A conceptual model for sustainable tourism. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2012, 9, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Hernández, L.; Carpio Pinedo, R.; Delgado Ruiz, M.A.; García Pastor, A. Intermodality: Bikes, Greenways and Public Transport. Best Practices Guide; Consorcio Regional de Transportes de Madrid (CRTM): Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Colorado, A.; Aizpurúa Giraldez, N.; Aycart Luengo, C. Desarrollo Sostenible y Empleo en Las Vías Verdes; Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, V.; Degioanni, A. How to support the design and evaluation of redevelopment projects for disused railways? A methodological proposal and key lessons learned. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 52, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mayor, C.; Martí, P.; Castaño, M.; Bernabeu-Bautista, Á. The Unexploited Potential of Converting Rail Tracks to Greenways: The Spanish Vías Verdes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycart Luengo, C. Vías verdes: Las pioneras. Ambient. Rev. Minist. Medio Ambiente 2007, 65, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de España, Ministerio de Fomento. Ferroviario. 2019. Available online: https://www.fomento.gob.es/ferroviario (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Guerrieri, M.; Ticali, D. Design standards for converting disused railway lines into Greenways. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Design and Construction (ICSDC) 2011, Kansas City, MO, USA, 23–25 March 2011; pp. 375–383. [Google Scholar]

- Aycart Luengo, C. Vias Verdes ‘Greenways’, to reuse disused rail-ways line for non motorised itineraries, leisure and tourism. Inf. Constr. 2001, 53, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://viasverdes.com/en/greenways/spanish-greenways-programme.asp (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- European Union External Action. European Union support: First Railway Museum in Uganda Opens. Delegation of the European Union to Uganda. 19 March 2021. Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/uganda/european-union-support-first-railway-museum-uganda-opens_en (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Trans-Iranian Railway (Iran): Listed by UNESCO in 2021. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1585 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Luhmann, N.; Febbrajo, A. Sistemi Sociali: Fondamenti di una Teoria Generale; Il Mulino: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 42. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, F.; MacDougall, C.; Smith, D. Participatory action research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, A.; De Medici, S. A sustainable adaptive reuse management model for disused railway cultural heritage to boost local and regional competitiveness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mısırlısoy, D. Railways as common cultural heritage: Cyprus as a case study. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 13, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L.; Rugolo, A. A Multicriteria Decision Aid Process for Urban Regeneration Process of Abandoned Industrial Areas. In New Metropolitan Perspectives—NMP 2020; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention. 2000. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/help/glossary/eea-glossary/european-landscape-convention (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Trapani, F.; Savarese, R.; Safonte, F. A territorial approach to the production of urban and rural landscape. Environ. Sci. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Napoli, G.; Trovato, M.R. Industrial areas and the city: Equalization and compensation in a value-oriented allocation pattern. In Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2016 (Lecture Notes in Computer Science); Gervasi, O., Apduhan, B.O., Taniar, D., Torre, C.M., Wang, S., Misra, S., Murgante, B., Stankova, E., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Eds.; Part IV; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9789, pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Time Frame | Main Actions | Tools & Methods | Participants | Outputs/Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Co-formulation of research questions | November 2023–Febrary 2024 | Identification of needs and expectations | Focus groups (4), semi-structured interviews (15), questionnaires (45), participant observation | ≈65 actors | Shared agenda; thematic synthesis; trust index |

| 2. Participatory exploration of the context | Febrary–May 2024 | Territorial immersion and mapping | Walkscapes (4), participatory mapping labs (3), visual workshops | ≈50 actors | 12 maps; 5 storyboards; perception survey |

| 3. Building a territorial laboratory | June 2024–ongoing | Establishment of a dialogue hub | Thematic tables (5), cooperation pacts, digital platform | ≈40 actors | Charter of Landscape Values (draft); governance map |

| 4. Experimentation and field action (planned) | 2026 (Planned) | Pilot reuse and cultural actions | Events, art residencies, tactical urbanism | ≈30 actors | Prototypes; attendance; feedback reports |

| 5. Co-evaluation and re-learning (planned) | 2026 (Planned) | Participatory evaluation | Focus groups; surveys; logbooks | ≈35 actors | Impact report; transfer guidelines |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Della Spina, L. Co-Evaluating Landscape as a Driver for Territorial Regeneration: The Industrial Archaeology of the Noto–Pachino Railway (Italy). Land 2025, 14, 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112116

Della Spina L. Co-Evaluating Landscape as a Driver for Territorial Regeneration: The Industrial Archaeology of the Noto–Pachino Railway (Italy). Land. 2025; 14(11):2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112116

Chicago/Turabian StyleDella Spina, Lucia. 2025. "Co-Evaluating Landscape as a Driver for Territorial Regeneration: The Industrial Archaeology of the Noto–Pachino Railway (Italy)" Land 14, no. 11: 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112116

APA StyleDella Spina, L. (2025). Co-Evaluating Landscape as a Driver for Territorial Regeneration: The Industrial Archaeology of the Noto–Pachino Railway (Italy). Land, 14(11), 2116. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112116