Regionalization of the Croatian Landscape: An Integrative Approach to Methods and Criteria for Defining Boundaries

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Determine which parts of the studied regions are represented in all analyzed regionalizations; that is, which parts of the landscape region contain the key landscape features.

- Show similarities and differences in approaches to determining the boundaries of the two regions and identify which landscape features (criteria) all authors agree are the bearers of identity.

- Determine to what extent the listed criteria coincide with those defined by the Landscape Character Assessment (LCA of the Republic of Croatia (2024) as relevant for the regional scale).

2. Materials and Methods

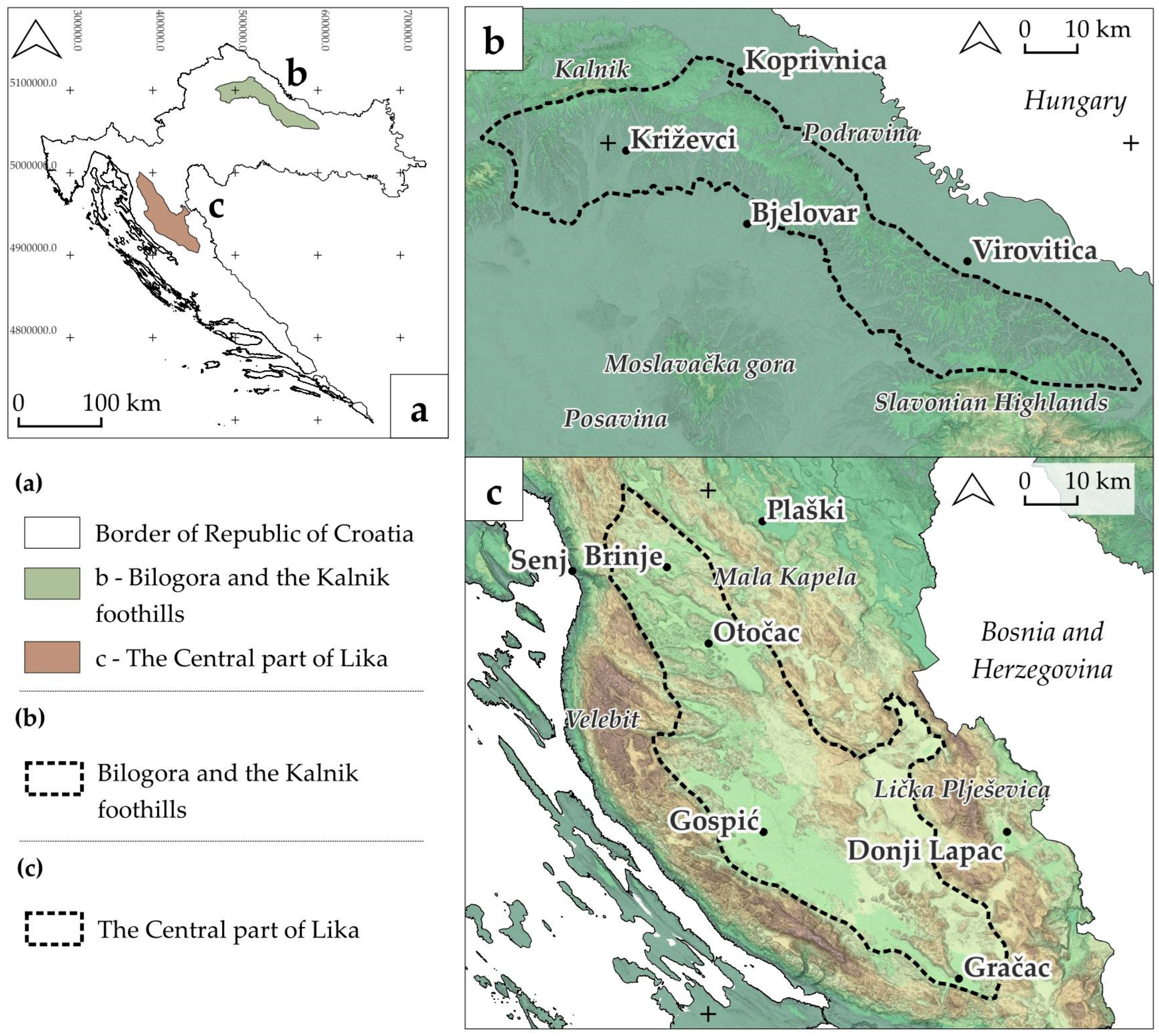

2.1. Research Area

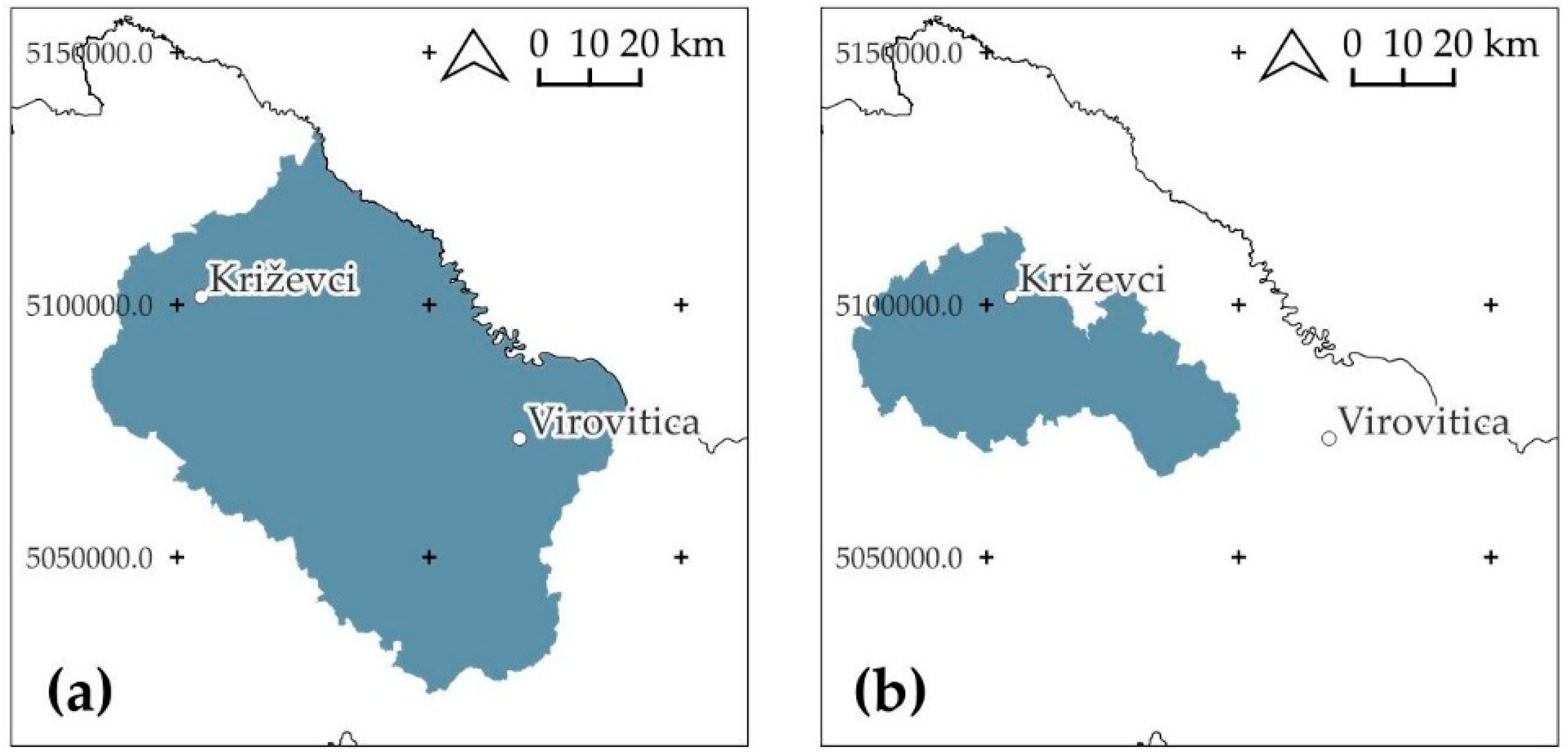

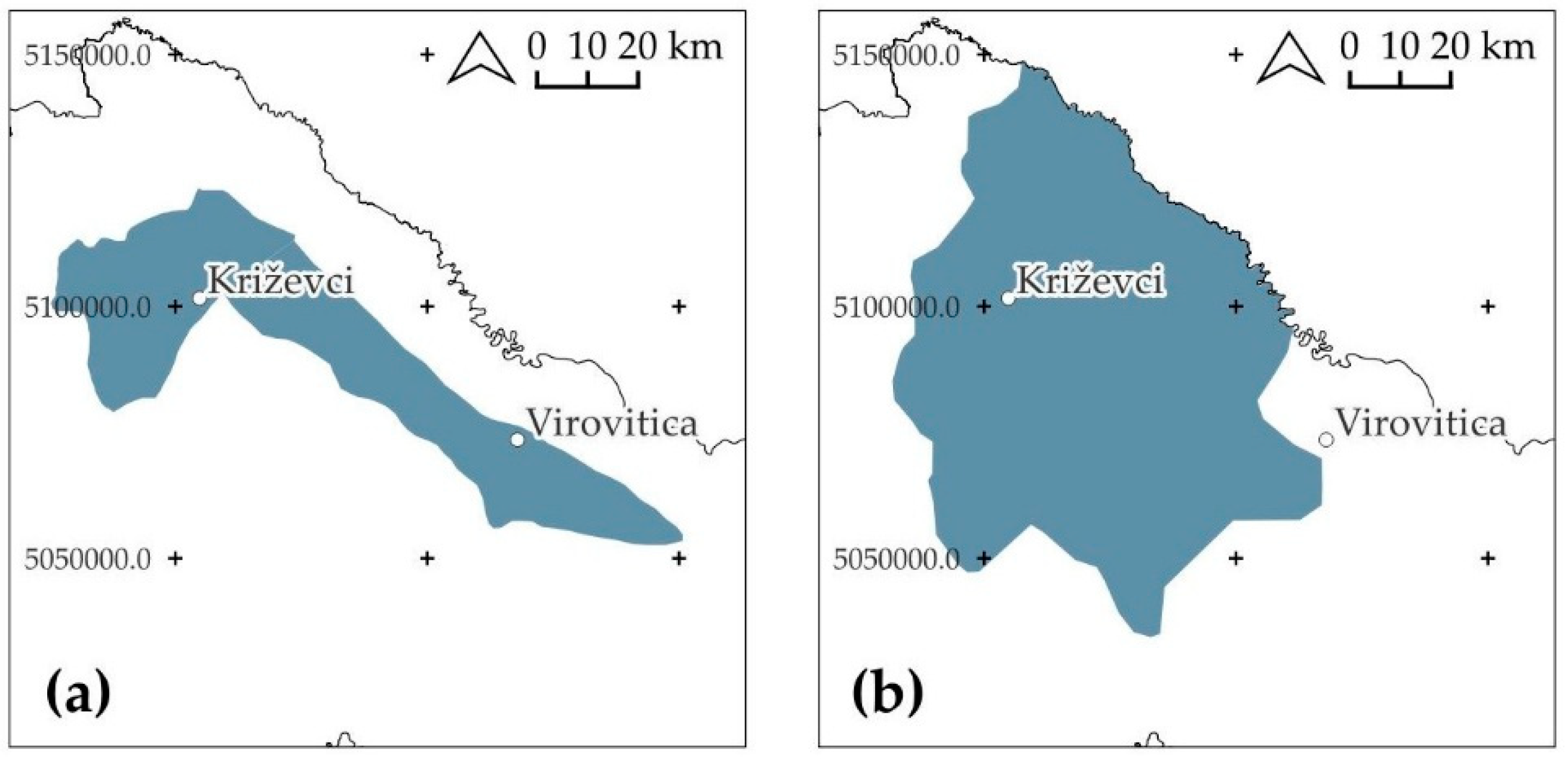

2.1.1. Bilogora and the Kalnik Foothills

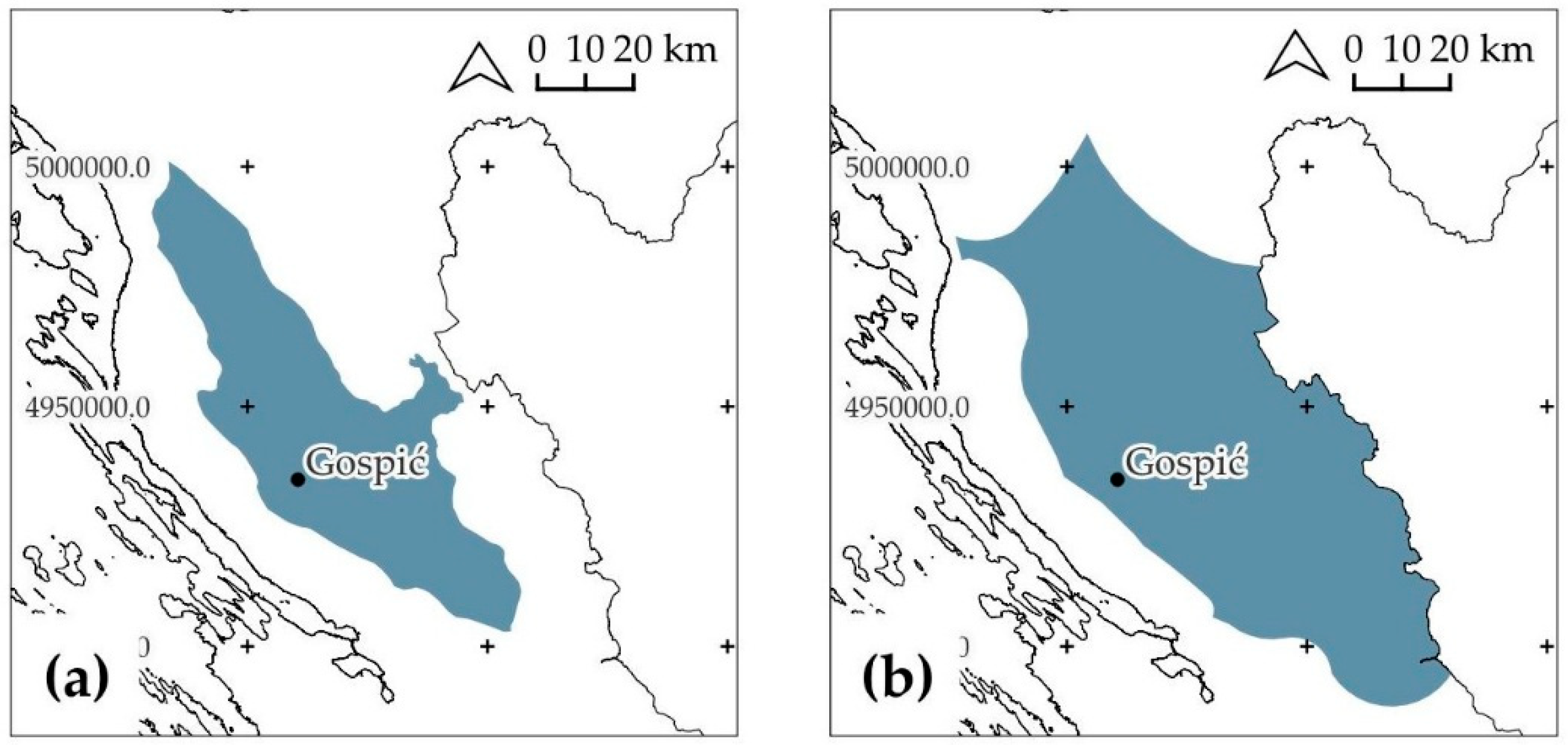

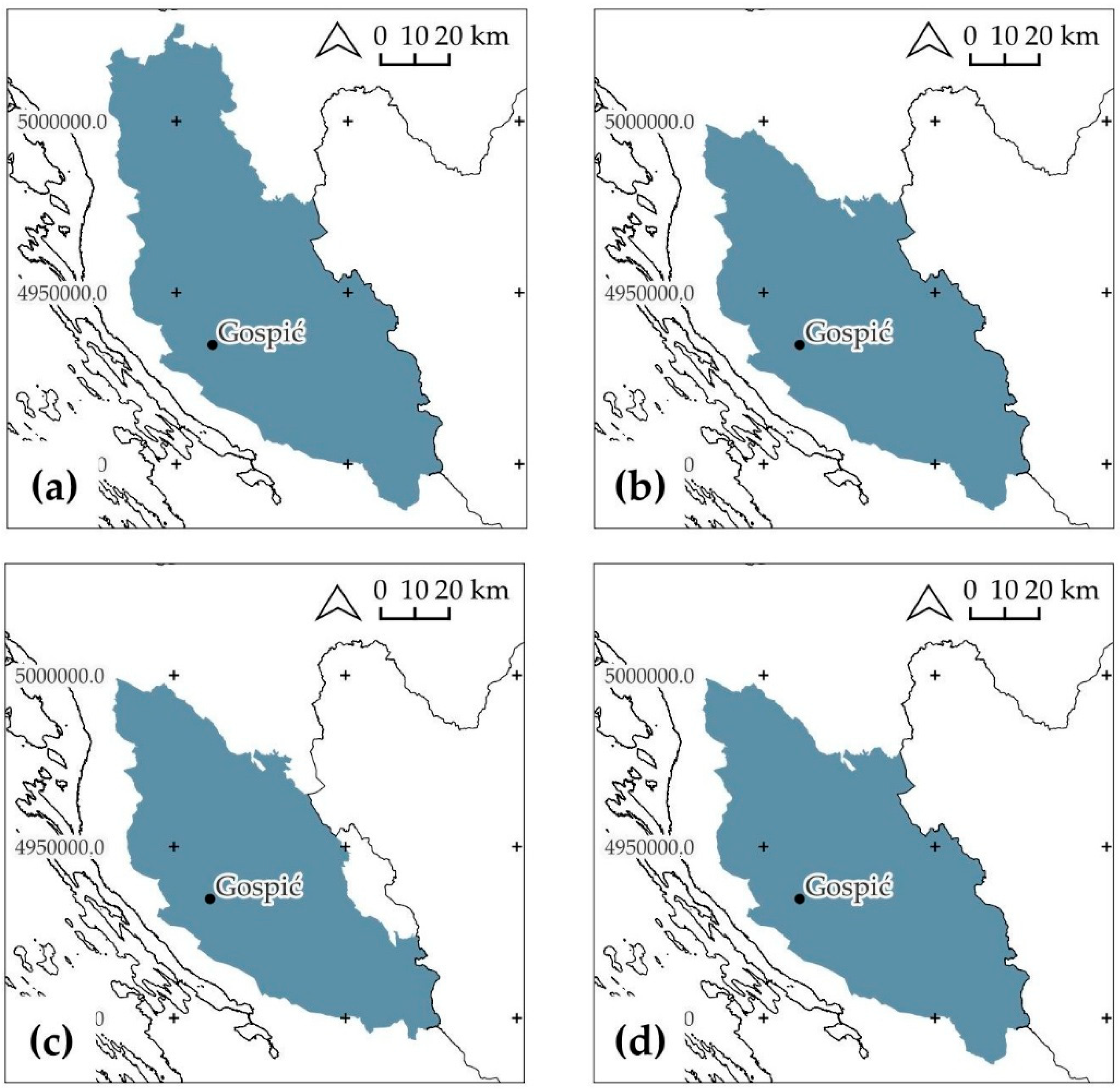

2.1.2. The Central Part of Lika

2.2. Overview of Analyzed Regionalizations

2.2.1. Landscape Regionalizations

| Regionalization | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Landscape regionalizations | |

| Landscape regionalization according to Bralić (1995) [49] | Relief Water Vegetation |

| LCA of the Republic of Croatia (2024) [50] | (Hydro)geology Hydrology Relief Cultural regions Land cover (CLC)–first level Forest vegetation |

| Geographical regionalizations | |

| Natural-geographical regionalization [52] | Morphostructural and morpholithogenic elements are key for regional differentiation, but in individual cases, the prevailing relationship of climatic, hydrological, biogeographic, and pedological elements was also of great importance. |

| Geographic regionalization [53] | Natural basis Specificities of socio-economic structures in the regions |

| Conditionally homogeneous regionalization [54] | Grouping economically relevant criteria of relief structure, climatic–ecological characteristics, and processes of historical–geographical development expressed in types of population structure related to ethnographic and economic characteristics. |

| Conditionally homogeneous regionalization [55] | It is based on the principle of “conditional uniqueness of individual Croatian spatial units”. |

| Natural regionalization | |

| Geomorphological regionalization of Croatia [56] | Relief Hydrology |

| Cultural regionalizations | |

| Regionalization of Croatian traditional architecture [57] | Natural factors: (1) geological composition of the soil, (2) vegetation cover, (3) climate, and (4) terrain configuration. Social factors: (1) economic activity of the population, (2) family structure, (3) social and political system, (4) population migration, (5) transport connections and therefore external influences, (6) public safety, (7) religion, etc. |

| Agricultural regionalization [58] | Similar geographical–climatic features Predominant land use |

| Historical–geographical region [59] | The Miroslav Krleža Lexicographic Institute is the central Croatian lexicographic institution. The encyclopedias, atlases, dictionaries, lexicons, and bibliographies of the Lexicographic Institute are traditionally reliable and interpret facts from Croatian heritage and social reality in a recognizable way. |

2.2.2. Geographical Regionalizations

2.2.3. Natural Regionalization

2.2.4. Cultural Regionalizations

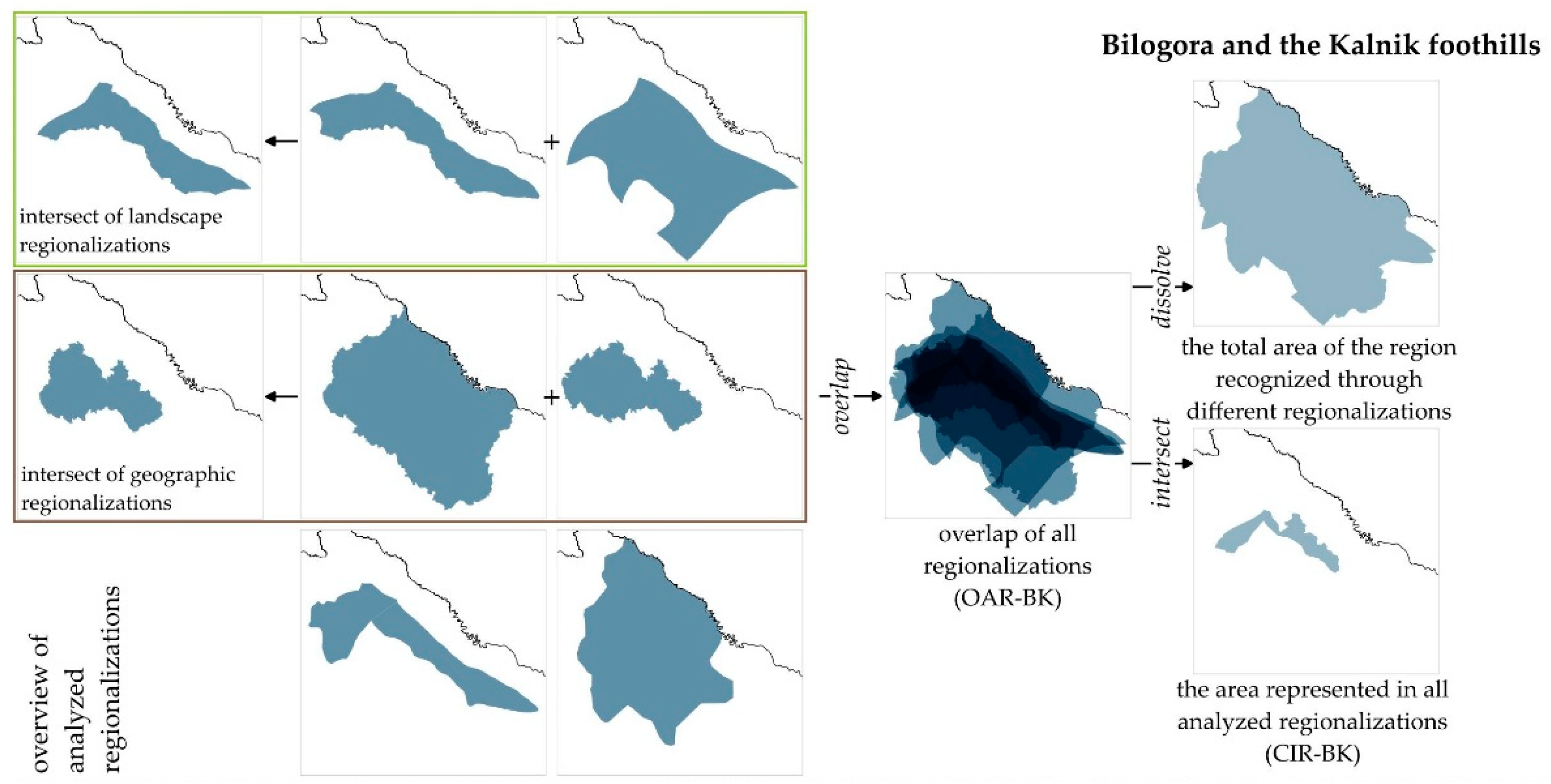

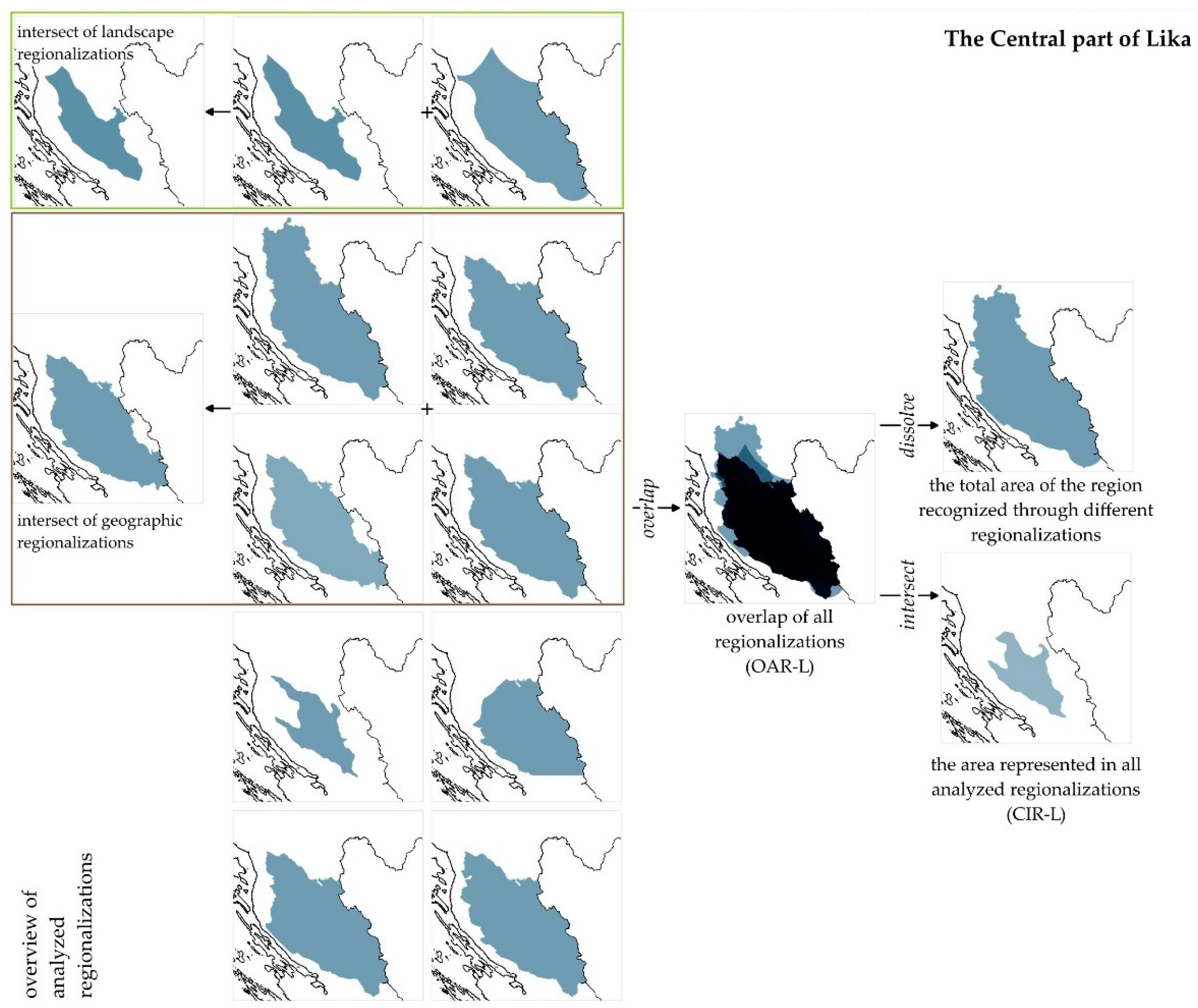

2.3. Methods

3. Results

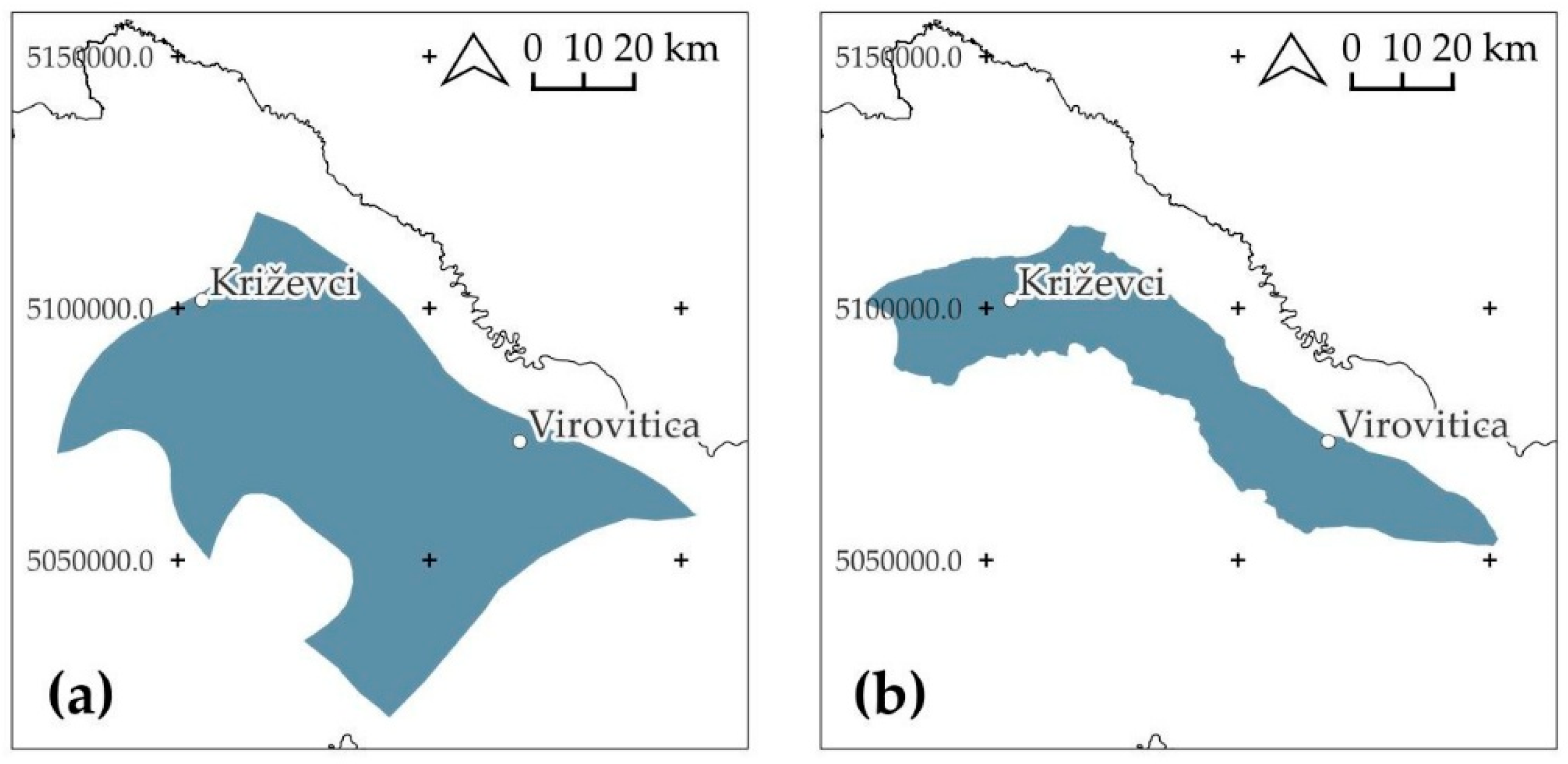

3.1. Bilogora and the Kalnik Foothills

3.1.1. Landscape Regionalizations of Bilogora and the Kalnik Foothills

3.1.2. Geographical Regionalizations of Bilogora and the Kalnik Foothills

3.1.3. Natural and Cultural Regionalizations of Bilogora and the Kalnik Foothills

3.2. The Central Part of Lika

3.2.1. Landscape Regionalizations of the Central Part of Lika

3.2.2. Geographical Regionalizations of the Central Part of Lika

3.2.3. Natural and Cultural Regionalizations of the Central Part of Lika

3.3. Comparison of Results in Two Regions

3.3.1. Bilogora and the Kalnik Foothills Regionalization Comparison

3.3.2. The Central Part of Lika Regionalization Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Identity of the Regions

4.2. Determination of the Criteria

4.3. Possibilities for Improving the Approach to Landscape Regionalizations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCA | Landscape Character Assessment |

| OLR-BK | Overlap (intersect) of landscape regionalizations (Bilogora and the Kalnik foothills) |

| OGR-BK | Overlap (intersect) of geographic regionalizations (Bilogora and the Kalnik foothills) |

| OAR-BK | Overlap (dissolve) of all regionalizations (Bilogora and the Kalnik foothills) |

| CIR-BK | An area that carries the identity of the region (Bilogora and the Kalnik foothills) |

| OLR-L | Overlap (intersect) of landscape regionalizations (The Central Part of Lika) |

| OGR-L | Overlap (intersect) of geographic regionalizations (The Central Part of Lika) |

| OAR-L | Overlap (dissolve) of all regionalizations (The Central Part of Lika) |

| CIR-L | An area that carries the identity of the region (The Central Part of Lika) |

Appendix A

| Title of the Region (Subject Region: 1-Bilogora/Kalnik, 2-Lika) | Area (ha) | |

|---|---|---|

| Landscape regionalizations | ||

| Landscape regionalization, 1995. | 1: Bilogora–Moslavina area | 494,301.36 |

| 2: Lika | 524,835.82 | |

| LCA of the Republic of Croatia, 2024. | 1: Bilogora and Kalnik foothills | 229,985.39 |

| 2: The central part of Lika | 261,043.12 | |

| Intersection of landscape regionalizations of Bilogora/Kalnik | 189,521.72 | |

| Intersection of landscape regionalizations of Lika | 241,296.05 | |

| Geographical regionalizations | ||

| Natural–geographical regionalization, 1996. | 1: N/A | N/A |

| 2: Lika | 636,958.27 | |

| Geographic regionalization, 1974. | 1: Lonjsko-Ilovska valley and the Bilogora part of Podravina | 628,085.76 |

| 2: Lika | 527,920.89 | |

| Conditionally homogeneous regionalization, 1983. | 1: Kalnik–Bilogora foothills area | 202,108.75 |

| 2: Lika valley | 472,832.72 | |

| Conditionally homogeneous regionalization, 2013. | 1: N/A | N/A |

| 2: Lika | 527,920.89 | |

| Intersection of geographical regionalizations of Bilogora/Kalnik | 175,527.11 | |

| Intersection of geographical regionalizations of Lika | 472,832.72 | |

| Natural regionalization | ||

| Geomorphological regionalization of Croatia, 1999. | 1: Bilogora hills with Slatinsko-voćinski hills / Kalnik mountain massif with foothill step and Žitomir hills | 236,250.90 |

| 2: Lika valley | 187,731.68 | |

| Cultural regionalizations | ||

| Regionalization of Croatian traditional architecture, 2013. | 1: N/A | N/A |

| 2: Lika | 408,850.45 | |

| Agricultural regionalization, 1993. | 1: Bilogora–Moslavina– Podravina region | 567,493.73 |

| 2: Lika | 546,366.30 | |

| Historical-geographical regionalization | 1: N/A | N/A |

| 2: Lika | 542,205.07 | |

| Intersection of cultural regionalizations of Bilogora/Kalnik | 567,493.73 | |

| Intersection of cultural regionalizations of Lika | 408,850.45 | |

| Overlap (dissolve) of all regionalizations of Bilogora/Kalnik | 836,353.50 | |

| Intersection of all regionalizations of Lika | 688,075.05 | |

| An area that carries the identity of the region (Bilogora and the Kalnik foothills) | 52,975.57 | |

| An area that carries the identity of the region (The Central Part of Lika) | 152,330.22 | |

References

- Brabyn, L. Landscape Classification Using GIS and National Digital Databases. Landsc. Res. 1996, 21, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simensen, T.; Halvorsen, R.; Erikstad, L. Methods for Landscape Characterisation and Mapping: A Systematic Review. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, N.P.; Hribar, M.Š.; Hudoklin, J.; Pipan, T.; Golobič, M. Defining Landscapes, and Their Importance for National Identity—A Case Study from Slovenia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wascher, D. European Landscape Character Areas—Typologies, Cartography and Indicators for the Assessment of Sustainable Landscapes; Final ELCAI Project Report; Landscape Europe; Information Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/1778 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Mücher, C.A.; Klijn, J.A.; Wascher, D.M.; Schaminée, J.H. A New European Landscape Classification (LANMAP): A Transparent, Flexible and User-Oriented Methodology to Distinguish Landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J.; Sunderland, T.; Ghazoul, J.; Pfund, J.-L.; Sheil, D.; Meijaard, E.; Venter, M.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Day, M.; Garcia, C.; et al. Ten Principles for a Landscape Approach to Reconciling Agriculture, Conservation, and Other Competing Land Uses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8349–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, K.; Egenhofer, M.J. Egenhofer. Identity-Based Change: A Foundation for Spatiotemporal Knowledge Representation. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2000, 14, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobbelaar, D.J.; Pedroli, B. Perspectives on Landscape Identity: A Conceptual Challenge. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Landscape Change: Plan of Chaos? Landsc. Urban Plan. 1998, 41, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; Sarlöv-Herlin, I.; Knez, I.; Ångman, E.; Sang, Å.O.; Åkerskog, A. Landscape Identity, before and after a Forest Fire. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkoly-Gyuró, É.; Balázs, P.; Tirászi, Á. Transdisciplinary approach of transboundary landscape studies: A case study of an Austro-Hungarian transboundary landscape. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Dan. J. Geogr. 2019, 119, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Brabyn, L. An Analysis of the Relationships between Multiple Values and Physical Landscapes at a Regional Scale Using Public Participation GIS and Landscape Character Classification. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugstad, K.; Svarstad, H.; Vistad, O.I. A Case of Conflicts in Conservation: Two Trenches or a Three-Dimensional Complexity? Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetta, G.; Voghera, A. Evaluating Landscape for Shared Values: Tools, Principles, and Methods. Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J. The Cultural Values Model: An Integrated Approach to Values in Landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHarg, I.L. Design with Nature; The Natural History Press: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, C.S. The Concept of Land Units and Land Systems; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Landscape Perspectives: The Holistic Nature of Landscape; Landscape Series; Springer Dordrecht: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce, R.; Barr, C.; Clarke, R.; Howard, D.; Lane, A. Land Classification for Strategic Ecological Survey. J. Environ. Manag. 1996, 47, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazeu, G.; Metzger, M.; Mücher, C.; Perez-Soba, M.; Renetzeder, C.; Andersen, E. European Environmental Stratifications and Typologies: An Overview. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 142, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. The Temporality of the Landscape. World Archaeol. 1993, 25, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marušič, I. Regionalna Razdelitev Krajinskih Tipov v Sloveniji—Metodološke Osnove; Ministrstvo za Okolje in Prostor: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, L.; Grobe, P.; Quast, B.; Bartolomaeus, T. Fiat or bona fide boundary—A matter of granular perspective. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piniarski, W. Challenges of a GIS-based physical-geographical regionalization of Poland. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caflisch, L. A typology of borders. In International Law: New Actors, New Concepts—Continuing Dilemmas; Brill|Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 183–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzi, A. Philosophical Issues in Geography—An Introduction. Topoi 2001, 20, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluemling, B.; Tai, H.-S.; Choe, H. Boundaries, Limits, Landscapes and Flows: An Analytical Framework for Boundaries in Natural Resource Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, 112129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atik, M.; Karadeniz, N. New approaches for new regions: Turkey. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape Character Assessment, 1st ed.; Fairclough, G., Herlin, I.S., Swanwick, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Käyhkö, N.; Fagerholm, N.; Khamis, M.; Hamdan, S.I.; Juma, M. The collaborative, Participatory Process of Landscape Character Mapping for Land and Forest Planning in Zanzibar, Tanzania. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape Character Assessment, 1st ed.; Fairclough, G., Herlin, I.S., Swanwick, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Swanwick, C. Landscape Character Assessment: Guidance for England and Scotland; The Countryside Agency and Scotish Natural Heritage: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reljić, D.T.; Butula, S.; Hrdalo, I.; Pereković, P.; Andlar, G. Overcoming the Institutional Approach to Protection Through Landscape Modeling. In Bridging the Gap; ECLAS Conference 2016, Conference Proceedings; Series of the Institute for Landscape and Open Space; HSR Hochschule für Technik Rapperswil: Rapperswil-Jona, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Geršič, M.; Perko, D. Regional Identity in Slovenia; Pokrajine v Sloveniji; Lex localis, Maribor; Institute for Local Self-Government Maribor: Maribor, Slovenia, 2020; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perko, D.; Ciglič, R.; Hrvatin, M. Landscape macrotypologies and microtypologies of Slovenia. AGS 2021, 61, 7–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanc, M.; Ferk, M.; Fridl, J.; Gašperič, P.; Klun, M.I.; Pipan, P.; Planinc, T.R.; Hribar, M.Š. Oblikovanje Predstav o Slovenskih Pokrajinah v Izobraževalnem Procesu; Geografija Slovenije 34; Založba ZRC: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoj, M. Slovenski Etimološki Slovar; Založba ZRC: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Huang, B.; Li, S.; Zhao, H.; Yang, X.; Zhu, J. SwinClustering: A new paradigm for landscape character assessment through visual segmentation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1509113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortt, N. Methods: Regionalization/Zoning Systems. In International Encyclopaedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bartůněk, M.; Bláha, J.D. Fluid regionalisation of semantic regions: Possibilities for visualisation. J. Maps 2025, 21, 2504068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Regions and Regional Dynamics. In The Sage Handbook of European Studies; Sage: London, UK, 2009; pp. 464–480. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, G. Region. In The Dictionary of Human Geography; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2009; pp. 630–632. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. Region and Place: Regional Identity in Question. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 27, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, M. The New Regionalism in Western Europe; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, M.J. Rethinking the Region: Culture, Institutions and Economic Development in Catalonia and Galicia. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2001, 8, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, C.L. Our Visual Landscape: Managing the Landscape under Special Consideration of Visual Aspects. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitavska, N. The Method of Landscape Identity Assessment. Res. Rural. Dev. 2011, 2, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A.; Sarlöv-Herlin, I. Changing Landscape Identity—Practice, Plurality, and Power. Landsc. Res. 2019, 44, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, G.; Herlin, I.S.; Swanwick, C. Routledge Handbook of Landscape Character Assessment, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. Where Are the Genii Loci? In Landscape, Our Home/Lebensraum Landschaft; Essays on the Culture of the European Landscape as a Task; Indigo: Zeist, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bralić, I. Landscape Differentiation and Evaluation with Regard to Natural Features. In Landscape: Content and methodological basis of Landscape Character Assessment of Croatia; Uređenje prostora; Ministry of Physical Planning, Construction and Housing of the Republic of Croatia, Department of Spatial Planning: Zagreb, Croatia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture; Green Infrastructure Ltd. Analytical framework for the development of the Landscape Character Assessment of the Republic of Croatia. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention. 2000. Available online: https://www.iflaeurope.eu/assets/docs/European_Landscape_Convention-Txt-Ref_en.pdf_.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Bognar, A. Physical and geographical assumptions of regional development in Croatia. In Proceedings of the 1st Croatian Geographical Congress, Krasno, Croatia, 18–19 September 2025; Croatian Geographical Society: Zagreb, Croatia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cvitanović, A. Geography of the Socialist Republic of Croatia; Školska knjiga: Zagreb, Croatia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Roglić, V. Outline of the conditionally homogenious regionalisation of Socialist Republic of Croatia. Hrvat. Geogr. Glas. 1983, 45, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Magaš, D. Geography of Croatia; Manualia Universitatis studiorum Iadertinae; Bibliotheca Geographia Croatica; Department of Geography, University of Zadar, Meridijani: Zadar, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bognar, A. Geomorphological regionalisation of Croatia. Acta Geogr. Croat. 1999, 34, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Department of Ornamental Plants and Landscape Architecture. Landscape: Content and methodological basis of Landscape Framework of Croatia; Uređenje prostora; Ministry of Physical Planning, Construction and Housing of the Republic of Croatia, Department of Spatial Planning: Zagreb, Croatia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Živković, Z. Croatian traditional architecture; Ministry of Culture, Directorate for the Protection of Cultural Heritage: Zagreb, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lika|Proleksis Enciklopedija. Available online: https://proleksis.lzmk.hr/34630/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Roglić, V. Geographical concept of the region. Hrvat. Geogr. Glas. 1963, 25, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Veyret-Verner, G. Sorre (Max).—Les Fondements de la Géographie humaine. Rev. Géogr. Alp. 1953, 41, 382–383. [Google Scholar]

- Pleić, T.; Glasnović, V.; Prelogović, V.; Kaufmann, P.R. In Search of Spatial Perceptions: The Balkans as A Vernacular Region. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 112, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šakaja, L. Stereotypes among Zagreb youth regarding the Balkans: A Contribution to the Study of Imaginative Geography. Rev. Za Sociol. 2001, 32, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pleić, T. Cultural regions in the teaching of geography: The example of a vernacular region. Geogr. Horiz. 2021, 67, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bilogora|Proleksis Enciklopedija. Available online: https://proleksis.lzmk.hr/12264/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-Identity: Physical World Socialization of the Self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Durrheim, K. Displacing Place-Identity: A Discursive Approach to Locating Self and Other. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 39, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perko, D.; Ciglič, R.; Hrvatin, M. The Usefulness of Unsupervised Classification Methods for Landscape Typification: The Case of Slovenia. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2019, 59, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilogora—Hrvatska Enciklopedija. Available online: https://www.enciklopedija.hr/clanak/bilogora (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Swaffield, S.; Challenger, N.; Davis, S. He tangata, he tangata, he tangata: Landscape characterisation in Aotearoa-New Zealand. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape Character Assessment, 1st ed.; Fairclough, G., Herlin, I.S., Swanwick, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsen, D. Space, Place and Perception: The Sociology of Landscape Exploring the Boundaries of Landscape Architecture. In Exploring the Boundaries of Landscape Architecture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ode, Å.; Tveit, M.S.; Fry, G. Capturing Landscape Visual Character Using Indicators: Touching Base with Landscape Aesthetic Theory. Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, C.; Jenkins, P. Place Identity, Participation and Planning, 1st ed.; RTPI Library Series; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, J. People and Place. Plan. Theory Pract. 2010, 11, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánek, J. From Mental Maps to GeoParticipation. Cartogr. J. 2016, 53, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffelen, A.; Kamminga, O.; Groote, P.; Meijles, E.; Weitkamp, G.; Hoving, A. Making use of sense of place in amalgamated municipalities. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2024, 34, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwig, K.R. The Practice of Landscape ‘Conventions’ and the Just Landscape: The Case of the European Landscape Convention. Landsc. Res. 2007, 32, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Culture and Changing Landscape Structure. Landsc. Ecol. 1995, 10, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Eastman, J.R. Application of fuzzy measures in multi-criteria evaluation in GIS. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2000, 14, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, J.R. Multi-criteria evaluation and GIS. In Geographical Information Systems, 2nd ed.; Goodchild, M.F., Maguire, D.J., Rhind, D.W., Eds.; Longley, JohnWiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 493–502. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P.C. Multilayered regionalization in Northern Europe. GeoJournal 2012, 77, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasala, K.; Šifta, M. The region as a concept: Traditional and constructivist view. AUC Geogr. 2017, 52, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartůněk, M.; Bláha, J.D. Visualisation of administrative division dynamics: Transformation of borders and names in the Bohemian-Saxonian borderland case. GeoScape 2023, 17, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, G.; Herlin, I.S.; Swanwick, C. Conclusion: Seeing obstacles and finding ways ahead. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape Character Assessment, 1st ed.; Fairclough, G., Herlin, I.S., Swanwick, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsich, M. Exploring the Correspondence Between Regional Forms of Governance and Regional Identity: The Case of Western Europe. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2010, 17, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bogovac, L.; Kamenečki, M.; Pereković, P.; Hrdalo, I.; Tomić Reljić, D. Regionalization of the Croatian Landscape: An Integrative Approach to Methods and Criteria for Defining Boundaries. Land 2025, 14, 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102068

Bogovac L, Kamenečki M, Pereković P, Hrdalo I, Tomić Reljić D. Regionalization of the Croatian Landscape: An Integrative Approach to Methods and Criteria for Defining Boundaries. Land. 2025; 14(10):2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102068

Chicago/Turabian StyleBogovac, Lara, Monika Kamenečki, Petra Pereković, Ines Hrdalo, and Dora Tomić Reljić. 2025. "Regionalization of the Croatian Landscape: An Integrative Approach to Methods and Criteria for Defining Boundaries" Land 14, no. 10: 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102068

APA StyleBogovac, L., Kamenečki, M., Pereković, P., Hrdalo, I., & Tomić Reljić, D. (2025). Regionalization of the Croatian Landscape: An Integrative Approach to Methods and Criteria for Defining Boundaries. Land, 14(10), 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102068