Valuation of Public Urban Space: From Social Value to Fair Value—Mind the Gap

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Public Urban Space as a Multidimensional Asset

- The present economic systems, which measure public spaces through monetary values, do not account for their social and environmental value.

- The solution of a pluralist and ethically grounded valuation framework enables the combination of diverse perspectives to create an inclusive approach for urban development.

- Informal or ambiguous urban areas create barriers against commercialization because they support different ways of creating value.

1.1.1. The Problem of Valuation

1.1.2. Why “Mind the Gap”

1.2. Aim, Contribution, and Structure

- To clarify the nature of the valuation gap, in the light of theoretical, historical, and political parameters and approaches.

- To explore how modern valuation systems weaken and marginalize aspects of public space that have no economic basis, such as social, cultural, and environmental values.

- Promoting a multidimensional and unifying framework that combines economic, social, ecological, and cultural parameters.

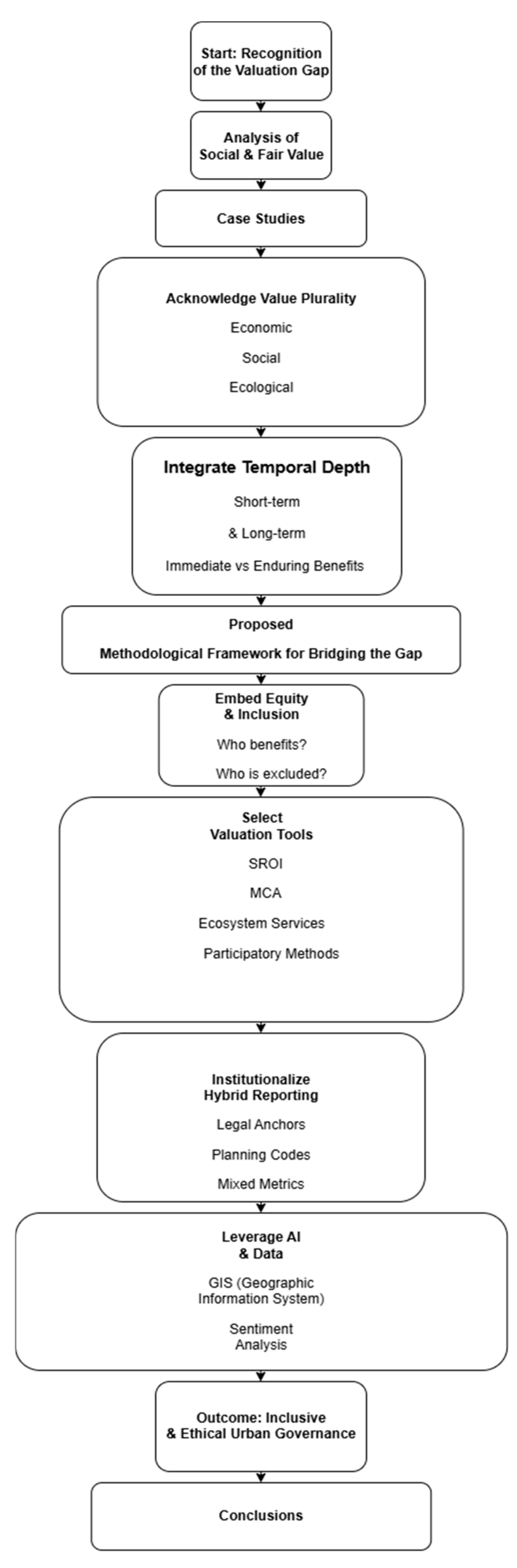

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Social Value in Urban Space

2.1.2. Fair Value and Economic Logics

2.1.3. Bridging Attempts

- Social Return on Investment (SROI)

- Ecosystem Services Valuation

- Multicriteria Analysis (MCA)

- Participatory Valuation

2.1.4. Valuation Divide

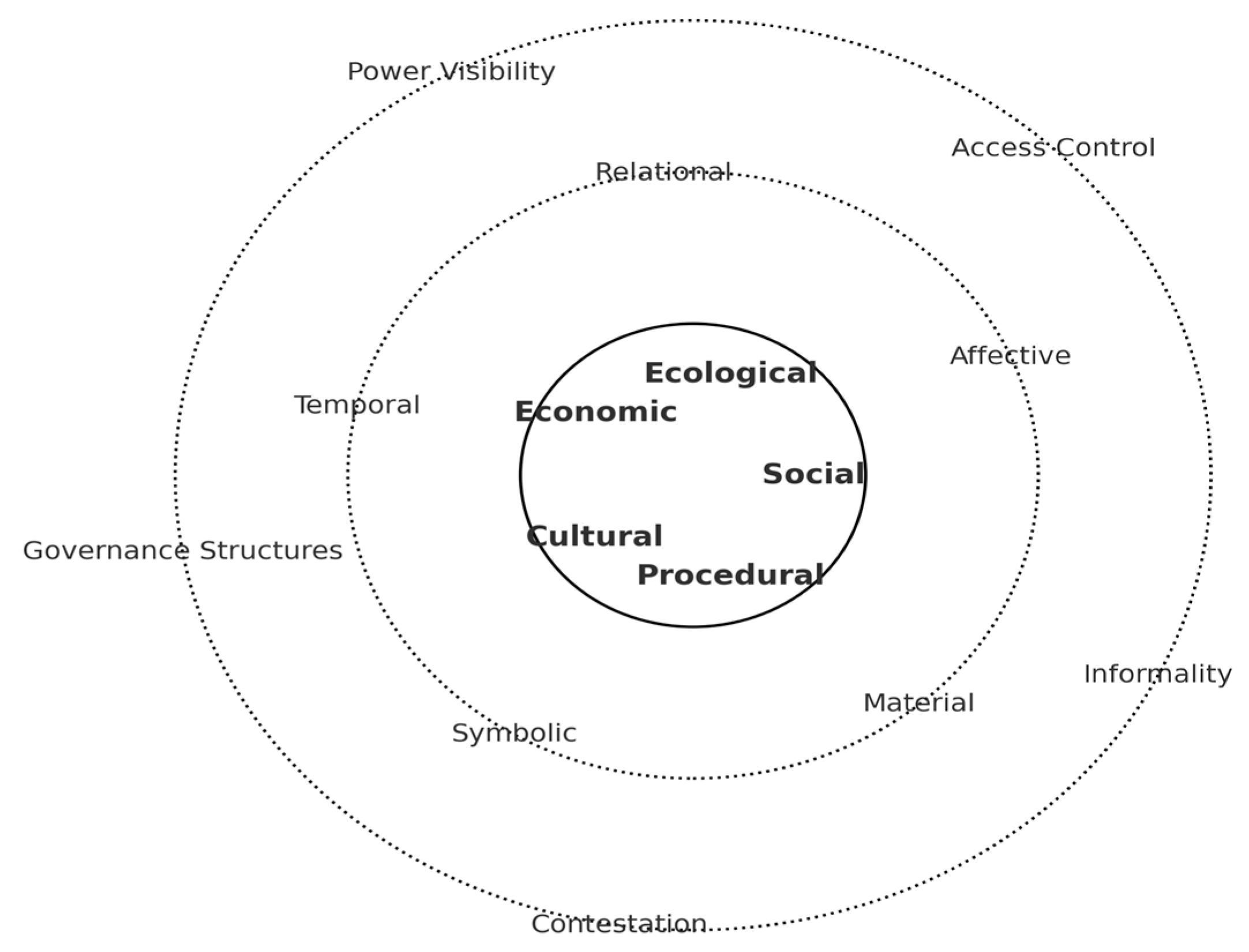

2.1.5. Theoretical Framework: Conceptualizing the Valuation Gap

2.1.6. Valuation as a Social and Political Act

2.1.7. Defining Social Value and Fair Value

2.2. The “Valuation Gap”

2.2.1. Conceptual Matrix of Urban Space Valuation

2.2.2. Implications of the Valuation Gap

- Deterioration of the Spatial Inequality of Justice Issues: Marginalized communities are disproportionately affected as their quality of life, which depends on social infrastructure, is not taken seriously in official decision-making, thus reinforcing exclusion and displacement patterns [1,15]. Finally, the one-dimensional focus of valuation on economic data leads to a risk to the legitimacy of governance. In other words, it undermines social trust while exacerbating social conflicts and ultimately weakening the institutional foundations of democracy [12,20].

3. Methodology

Toward an Integrative Valuation Paradigm

4. Results

4.1. Valuation Gap Through Empirical Examples

4.1.1. Syntagma Square, Athens

4.1.2. Public Spaces Adjacent to Metro Stations

4.1.3. Waterfront Redevelopment: Thessaloniki, London Docklands, and Mumbai

4.1.4. Holiday Rentals in the Historic Place of Barcelona

4.2. Synthesis of Illustrations

- Economic metrics (such as property prices and commercial activity) direct the discussion about valuation methods and planning strategies. In particular, real estate prices form the basis of valuation methods, transforming intangible urban characteristics into monetary terms and highlighting the behavior of the market [42]. At the same time, cities adopt planning strategies determined by measures of competitiveness in investment, tourism, and commercial activity, enslaving the redesign of public spaces to the demands of the service economy.

- Social and environmental values are marginalized, since notions such as democracy, social cohesion, or environmental management are not reflected in valuation calculations.

- The existing valuation system has adverse effects, driving vulnerable groups into social and spatial isolation and turning public spaces into virtual private ones.

- The valuation methods used do not accurately reflect the experiences and institutionally enshrined interests of the community, leading to a lack of public trust and frequent public disputes over valuation procedures.

5. Discussion

5.1. “Non-Conforming” Spaces

5.2. Structural Factors of Valuation Gap

5.2.1. Urban Justice Implications

5.2.2. Governance and Legitimacy

5.2.3. Methodological Challenges and Risks

- First, the evaluation framework needs modifications to handle different time spans because it needs to achieve short-term financial benefits while building social value, cultural heritage, and environmental sustainability in the long run.

- Second, emphasis should be placed on equality and inclusion, bringing the voices and experiences of marginalized people to the forefront and fostering more democratic forms of governance.

- Third, successful implementation of policies needs governance systems that establish mechanisms for participation, transparency, and accountability and that incorporate pluralistic values into actual decision-making processes.

- Ultimately, the capabilities of innovative technologies and data sources, including crowdsourcing platforms, participatory mapping, and sentiment analysis, enable the collection of social value dimensions that were previously unmeasurable.

5.3. Toward an Integrative Framework

5.3.1. Principles of the Integrative Framework

- Plurality of Value

- 2.

- Temporal Depth

- 3.

- Equity and Inclusion

5.3.2. Valuation Dimensions and Indicators

| Perspective | Quantitative Factors | Qualitative Factors | Tool and Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Property Value, Rental Income, Investment Cash Flow | Views on Affordability, Economic Opportunities | Hedonic Pricing, Cost–Benefit Analysis, Econometric Models |

| Social | Accessibility Indexes, Crime Statistics, Mobility Flows | Sense of Belonging, Safety, Inclusivity, Trust | Surveys, Ethnography, Social Mapping, Participatory Valuation, SROI |

| Ecological | Biodiversity Indices, CO2 Sequestration Rates, Stormwater Absorption | Environmental Quality Perceptions, Ecological Narratives | Ecosystem Services Valuation, GIS, Environmental Modeling |

| Cultural | Number of Cultural Events, Heritage Site Preservation Status, Visitor Numbers to Museums/Sites | Cultural Narratives, Identity, Collective Memory | Content Analysis, Oral Histories, Storytelling Workshops, Historical Documentation |

5.3.3. Governance Mechanisms and Tools

- The participatory valuation forums establish official meeting spaces for community members to work together on value definition and priority setting and direct valuation process involvement. The forums both implement equity principles and enhance democratic governance systems in urban areas.

- The valuation reports combine economic evaluations with assessments of social elements and cultural and environmental factors (hybrid valuation). The reports accomplish this through the combination of various evaluation approaches within planning and policy documents, which allow decision-makers to select options based on full value assessments.

- Legal and institutional anchors are essential for consolidating plural valuation principles. The implementation of these values within legal frameworks and municipal planning rules establishes procedural authority that protects non-economic values from being excluded in practice.

- AI-augmented monitoring systems combined with big data, GIS mapping, and mobile tracking and sentiment analysis of social media content allow for real-time evaluation of urban space usage and public perception.

5.4. Advantages and Opportunities

- Comprehensiveness

- Legitimacy

- Resilience

- Justice

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

- Recognize the different values of economics, society, nature, and culture as separate entities that cannot be combined into a single measurement system.

- Implement short-term economic requirements alongside sustainable community development and environmental protection through time-based implementation.

- Integrate an equity perspective which gives priority to marginalized voices while performing cost–benefit assessments to benefit all stakeholders for spatial justice purposes.

- Employ a variety of methodological tools, which include participatory valuation, multi-criteria analysis, ecosystem service assessments, and advanced data analytics.

- Institutionalize through governance systems that protect inclusion and transparency and accountability through legal frameworks, hybrid valuation reports, and continuous monitoring systems which use emerging technologies.

- Current system needs to overcome its reliance on basic economic logic.

- Valuation should be recognized as a governance method which cannot be separated from values and power dynamics and competing urban development perspectives.

- The project requires experts from economics, urban sociology, environmental science, and critical planning to work together in a transdisciplinary manner.

- The development of operational frameworks should focus on creating systems which adapt to specific contexts whilst understanding social and cultural and ecological relationships and producing results that can be applied directly to real-world governance.

6.2. Implementation Challenges

6.3. Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| MCA | Multi-Criteria Analysis |

| SROI | Social Return on Investment |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| PCP | Public–Community Partnership |

| IVSC | International Valuation Standards Council |

References

- Madanipour, A. Whose Public Space? International Case Studies in Urban Design and Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Le droit à la Ville; Anthropos: Sankt Augustin, Germany, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrides, S. Common Space: The City as Commons; Zed Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies: Towards a Relational Planning for Our Times; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M.; Taplin, D.; Scheld, S. Rethinking Urban Parks: Public Space and Cultural Diversity; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Espeland, W.N.; Stevens, M.L. Commensuration as a social process. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Marcuse, P.; Mayer, M. Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dombroski, K.; Diprose, K.; Sharp, E. Valuing diverse economies in urban policy. Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 846–861. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. The 21st-century metropolis: New geographies of theory. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.S. The Just City; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, S. Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Product differentiation in pure competition. J. Political Econ. 1974, 82, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, A.E.; Greenberg, D.A.; Vining, A.R.; Weimer, D.L. Cost–Benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J.; Tickell, A. Neoliberalizing space. Antipode 2002, 34, 380–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.; Lawlor, E.; Neitzert, E.; Goodspeed, T. A Guide to Social Return on Investment; The SROI Network: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondrogianni, D.; Stephanedes, Y.J.; Saranti, P.G.I. Multiple-criteria decision analysis of urban planning methods towards resilient open urban praces. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Urban Planning and Regional Development Regional Planning and Inform. Soc. (REAL CORP), Vienna, Austria, 14–16 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Latouche, S. Farewell to Growth; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. The Cultures of Cities; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Başaslan, Z. The Square as a Tool of Social Communication and Socialization. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2022, 7, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Dalakoglou, D. The Crisis before The Crisis: Violence and Urban Neoliberalization in Athens. Soc. Justice 2012, 39, 24–42. [Google Scholar]

- van Wee, B.; van Cranenburgh, S.; Maat, K. Substitutability as a spatial concept to evaluate travel alternatives. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 79, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierikko, K.; Nieminen, H.; Salomaa, V.; Häkkinen, J.; Salminen, J.; Sorvari, J. Kiertotalous Maankäytön Suunnittelussa: Kaavoitus kestävän; Suomen Ympäristökeskus: Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L.; Braconi, F. Gentrification and displacement: New York City in the 1990s. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2004, 70, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gemenetzi, G. Thessaloniki: The changing geography of the city and the role of spatial planning. Cities 2017, 64, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.; Hubbard, P. The Entrepreneurial City: Geographies of Politics, Regime, and Representation; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baviskar, A. Waterscapes: The Cultural Politics of a Natural Resources (Nature, Culture, Conservation); Permanent Black: Delhi, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Seccombe-Hett, T. Economic Valuation and Environmental Decision-Making in Europe. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 38, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabatzis, G.; Myrivili, E. The Waterfront of Thessaloniki: A Landscape of Contested Identities and Selective Memory. The Politics of the Urban Waterfront; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cócola-Gant, A. Holiday rentals: The new gentrification battlefront. Sociol. Res. Online 2016, 21, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Solà-Morales, I. Terrain Vague; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Franck, K.; Stevens, Q. Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, D.; Uffer, S. The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; Conservation Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L. The city and the territory system: Towards the "New Humanism" paradigm. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. For Space; SAGE: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K.; Pafka, E. What is Walkability? Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecca, U.; Mecca, B. Surfacing Values Created by Incentive Policies in Support of Sustainable Urban Development: A Theoretical Evaluation Framework. Land 2023, 12, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czembrowski, P.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Kronenberg, J. Bioculturally valuable but not necessarily worth the price: Integrating different dimensions of value of urban green spaces. Urban for. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, J.; Newman, P. Vauban: A European model bridging the green and brown agendas. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2009, 2, 75–102. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Short-Term | Long-Term |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | Property Values, Taxes, Fiscal Benefits | Investment Multipliers, Public revenue from taxation |

| Social | Accessibility, Public Safety, Civic Events | Cultural Heritage, Democratic Governance, Social Trust and Cohesion |

| Dimension | Short-Term | Long-Term |

|---|---|---|

| Economic (Fair Value) | - Real estate prices - Income from rents - Taxation receipts | - Returns on investment multipliers - Fiscal expansion - Increase in property values |

| Social (Use Value) | - Spatial Accessibility - Public safety - Participation in community events | - Preservation of cultural heritage - Social trust and cohesion - Environmental sustainability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karanikolas, N.; Athanasouli, E.; Kyriakidou, E. Valuation of Public Urban Space: From Social Value to Fair Value—Mind the Gap. Land 2025, 14, 2012. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102012

Karanikolas N, Athanasouli E, Kyriakidou E. Valuation of Public Urban Space: From Social Value to Fair Value—Mind the Gap. Land. 2025; 14(10):2012. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaranikolas, Nikolaos, Eleni Athanasouli, and Eleni Kyriakidou. 2025. "Valuation of Public Urban Space: From Social Value to Fair Value—Mind the Gap" Land 14, no. 10: 2012. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102012

APA StyleKaranikolas, N., Athanasouli, E., & Kyriakidou, E. (2025). Valuation of Public Urban Space: From Social Value to Fair Value—Mind the Gap. Land, 14(10), 2012. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14102012