Abstract

The withdrawal of rural households from contracted farmland optimizes land resource allocation, aligning with urbanization and agricultural modernization goals, and supports agricultural transformation and urban–rural integration. Utilizing survey data from 1478 rural households in Shanghai and Wuhan suburbs, this study employs ordered Probit models and mediation effect tests to examine how urban social security influences farmland withdrawal and the role of pension income. Results indicate that within the context of new urbanization, 56.90% of rural households exhibit a social security participation rate exceeding 50%, with urban social security enrollment significantly facilitating the withdrawal of contracted farmland by suburban rural households. Specifically, a one-unit rise in the proportion of insured individuals escalates the likelihood of permanent farmland withdrawal by 25%. Among these, pension income plays a positive mediating role in the process of urban social security influencing farmers’ withdrawal from farmland. Participation in urban social security enhances farmers’ pension income levels, thereby strengthening their farmland withdrawal degree. Consequently, to effectively advance the mechanism for rural farmland withdrawal, social security emerges as a fundamental pillar. This study furnishes empirical backing for the “substituting land security with social security” proposition and offers crucial insights for enhancing rural land withdrawal policies.

1. Introduction

The withdrawal of rural contracted land serves as an effective mechanism for optimizing the allocation and rational flow of land resources, representing a tangible manifestation of the realization of farmers’ land rights and interests. This process can facilitate urbanization and agricultural modernization, while also promoting the urban integration of agricultural migrant workers [1,2,3]. As early as 2015, the State Council outlined in the “Opinions on Accelerating the Transformation of Agricultural Development Modes” the voluntary implementation of pilot programs for compensating rural households for withdrawing from contracted land in designated rural reform pilot regions. These initiatives aim to guide rural households in orderly withdrawing their land contract management rights. Various withdrawal models have emerged in practice, such as the “dual-land linkage” model in Huqiu, Jiangsu, the “three-self and three-exchange” model in Neijiang, Sichuan, and the “two-separation and two-exchange” model in Jiaxing, Zhejiang. Despite these diverse models, the current “land withdrawal” reform remains in the experimental phase, lacking standardized institutional frameworks concerning withdrawal period and methods. Academic discourse also reflects discrepancies in defining this concept. Scholars have approached the definition of withdrawal from contracted land from multiple perspectives, categorizing it as passive or active withdrawal based on voluntariness [4], short-term, long-term, or permanent withdrawal based on contract duration [5], and withdrawal of management rights or contract rights based on property rights delineation [6]. Despite these varied classifications, the core of voluntary and compensated withdrawal from contracted land entails the permanent relinquishment of land contractual rights by rural households. This inherent characteristic has somewhat limited the actual number of rural households engaging in land withdrawal practices.

The ongoing reform has prompted scholarly attention to farmers’ inclination to relinquish contracted land, scrutinized at micro and macro levels. Research indicates that farmers’ willingness to withdraw is primarily shaped by individual traits, family resources, and external policy factors [7,8,9,10]. Individual characteristics encompass gender, age, education, and health status [11]. Family resources include income, assets, and dependency ratios [12,13,14,15], off-farm employment status [16,17,18,19], and perceptions of land property rights [20,21,22]. Furthermore, factors such as the size, quality, and cultivation conditions of contracted land also play a significant role [23,24,25].

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, China has made significant progress in its new urbanization initiative. The country’s permanent resident urbanization rate has reached 66.16%, with approximately 165 million agricultural migrants having settled in urban areas over the past decade. The large-scale transfer of rural labor to cities has gradually diminished the social security function of rural land, a trend particularly evident in the suburbs of major cities. The demographic shifts and changes in agricultural management modes driven by urban–rural structural transformation have become fundamental forces motivating farmers to relinquish their contracted land. Contracted land for farmers not only serves as a means of production but also fulfills various security functions, acting as a guarantee for essential survival needs such as economic income, employment, old-age support, and housing. The correlation between social security, particularly old-age security, and the withdrawal of contracted land has garnered significant attention. Despite the relatively modest overall rural social security provisions, which often fall short of meeting farmers’ practical requirements, urban areas boast a more comprehensive social insurance framework covering employment, healthcare, old-age support, and housing. This urban system exerts a certain substitutive influence on the security role traditionally played by contracted land. The extensive urban social security benefits, accumulated through prolonged urban residency, intensify farmers’ aspirations for enhanced social security. Studies indicate that as farmers progressively access comprehensive urban social security benefits, their inclination towards permanent withdrawal from contracted land increases [26,27]. Noteworthy pilot initiatives involving “exchanging contracted land for social security” in specific regions demonstrate that by withdrawing contracted land agreements, elderly farmers unable to work can secure corresponding old-age benefits, thereby elevating their social security level [28]. Furthermore, an investigation into farmers’ withdrawal preferences revealed that 81.9% of respondents expressed readiness to forego contracted land in favor of urban employee endowment insurance [29], underscoring that heightened social security provisions can further incentivize farmers to permanently withdrawal from contracted land.

Scholars worldwide have extensively researched and debated various aspects related to contracted land withdrawal, including its conceptual definition [30], interest demands [31,32], withdrawal forms [33,34], withdrawal willingness, and influencing factors [24,35]. Previous studies have elucidated the essence, methodologies, models, and willingness associated with contracted land withdrawal, offering crucial theoretical underpinnings and methodological frameworks for this study. However, few studies have specifically examined the impact of urban social security factors on the degree of farmland withdrawal by rural households, and even fewer have explored the role of pension income as an intermediary variable in influencing farmland withdrawal. Most empirical analyses have merely considered old-age security as a control factor [36,37]. Furthermore, existing literature predominantly concentrates on the correlation between rural old-age security and land transfer [38,39,40], which has somewhat facilitated the withdrawal of land management rights. However, prevalent issues persist in China’s rural social security system, such as inadequate security levels and funding. Despite its broad coverage, the system’s efficacy remains limited, failing to substantially incentivize farmers to fully and permanently withdraw from contracted land [41]. Given the pivotal role of contracted land in farmers’ old-age security, this study delves into the internal impact mechanism of social security on farmers’ inclination for contracted land withdrawal, focusing on urban social insurance and pension income levels. The aim is to propose viable policy strategies for advancing urban–rural integration.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Social Security and the Withdrawal of Rural Households from Contracted Farmland

For an extended period, land has served as a crucial source of social security for farmers, providing employment and old-age support. Despite the relatively low efficiency of agricultural production, farmers have traditionally relied on their contracted land to obtain essential food supplies, thereby reducing household expenses and easing the burden of old-age support. As farmers grow older, their labor capacity diminishes gradually, leading to challenges of unemployment and retirement, whether they reside in rural or urban settings. Thus, the contracted land plays a vital role in ensuring farmers’ livelihood security. The establishment of China’s social security system commenced belatedly, resulting in a significant disparity in social security provisions between rural and urban areas due to the enduring urban–rural dual social and economic structure. Notably, there exist marked discrepancies in the social security benefits accessible to farmers compared to urban residents. Given the inadequacies of the current social security system, farmers encounter difficulties in deciding to relinquish their contracted land. Presently, urban social insurance offers robust protection, effectively diminishing the social security function of contracted land. The post-retirement pension, characterized by a high replacement rate relative to the insured individual’s pre-retirement wage, adequately meets basic old-age support requirements. Consequently, rural households enrolled in urban social insurance no longer rely on contracted land for old-age support [42]. At this moment, the contracted land assumes the role of an idle asset. Disengaging from the contracted land enables farmers to realize its asset value fully, enhance household asset utilization efficiency, alleviate economic pressures, elevate living standards, augment old-age savings, and facilitate the transition to urban residency. Hence, farmers participating in urban social insurance exhibit a greater inclination to permanently withdraw from their contracted land compared to those who do not participate, recognizing the array of benefits associated with such a decision.

The decision-making process of farmers to withdraw from contracted land is a rational one driven by the pursuit of economic and social benefits. Farmers opt for permanent withdrawal from contracted land only when the potential benefits of doing so outweigh those of retaining the land. Enhancing the level of social security is theoretically linked to increased income for farmers [43,44], reduced dependence on land [45], and consequently, facilitates land withdrawal. Specifically, within urban social security, endowment insurance plays a pivotal role in farmers’ decisions to withdraw from land. As farmers age, endowment insurance serves as a source of income, influencing their decision-making process regarding land withdrawal [46]. Endowment insurance, a key component of the “five insurances and one housing fund”, exhibits a high participation rate and partially substitutes the old-age security function traditionally provided by contracted land. Participation in urban endowment insurance alleviates labor burdens, enhances farmers’ risk management capabilities, and increases the likelihood of land withdrawal [47]. Furthermore, an increase in the benefits of social endowment insurance within a certain threshold promotes farmers’ permanent withdrawal from contracted land [42]. A comprehensive social security system significantly influences farmers’ decisions to exit agricultural production and addresses their apprehensions regarding land withdrawal [27,48]. The degree of farmers’ withdrawal from contracted land is primarily contingent upon the prevailing social security conditions.

Hypothesis 1.

Urban social security has a significant positive impact on farmers’ withdrawal from contracted farmland. Participation in urban social security enhances the degree of withdrawal from contracted farmland, and the higher the proportion of household members participating in urban social security, the stronger the degree of withdrawal.

2.2. Mechanism of Action of Pension Income

Against the backdrop of rapid development of new-type urbanization in China, large-scale outflow of rural labor from suburban areas, and the continuous weakening of the land pension function for farmers, the relatively stable and annually increasing pension insurance funds are playing an increasingly important role. The more farmers participate in social insurance and the higher their contribution levels, the more pension they will receive in old age. Therefore, farmers with higher contribution standards will primarily rely on socialized pension systems in the future, while those with lower contributions or no participation in social insurance are more likely to choose traditional family-based or land-based pension pathways. Such farmers have a relatively higher dependence on land and a lower degree of land contract withdrawal [49]. Various studies corroborate these findings. For instance, research in Cuba revealed that an upsurge in pension benefits led to a 38% decline in elderly individuals engaging in agricultural work, resulting in a reduction of up to 22.5 weekly labor hours [50]. Drawing on South African data, Bertrand [51] highlighted a significant decrease in agricultural labor provided by adult children, particularly the eldest son, following the receipt of pension benefits by the family. Pension income markedly influences the decision of rural elderly individuals to partake in agricultural work and the number of hours dedicated to such activities. From a marginal effect perspective, for every additional 1 yuan of other pension income, rural elderly individuals will engage in 0.144 fewer hours of agricultural labor [52]. These findings suggest that increased pension income can free farmers from agricultural labor [53], increase their likelihood of seeking off-farm employment [54], and thereby promote the withdrawal from contracted land.

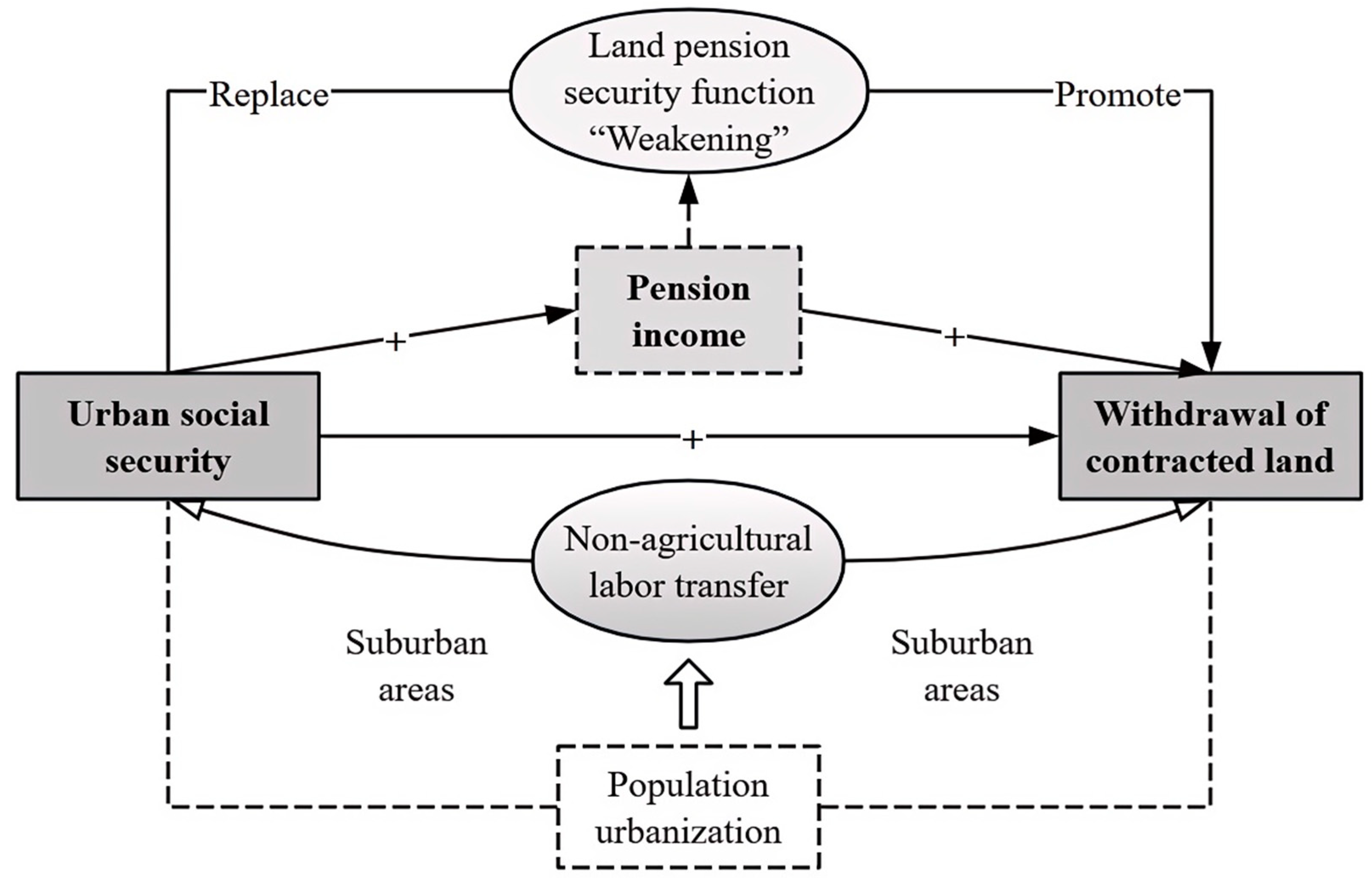

Farmers with lower pension incomes rely more on their contracted farmland and prioritize its production and security functions. When considering withdrawing from farmland, they prioritize their families’ livelihood issues. Conversely, farmers with higher pension levels can rely on social insurance in old age, eliminating the need for farmland for support. For them, withdrawing from farmland means losing some agricultural income or rent without significantly impacting old-age support or basic living conditions. Additionally, compensation for withdrawing can enhance their quality of life in old age. Hence, under suitable circumstances, to maximize farmland asset value and income, these farmers are more inclined to monetize their contracted farmland rights through permanent withdrawal to meet their families’ financial needs. The theoretical framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework.

Hypothesis 2.

Pension income has a significant positive impact on farmers’ withdrawal from contracted farmland; the higher the pension income, the greater the degree of withdrawal from contracted farmland.

Hypothesis 3.

Pension income serves as a key channel through which urban social security influences farmers’ withdrawal from contracted land. An increase in the proportion of individuals participating in urban social security raises farmers’ pension income, thereby enhance the extent to which they withdraw from their contracted land.

3. Data Sources and Variable Selection

3.1. Study Area

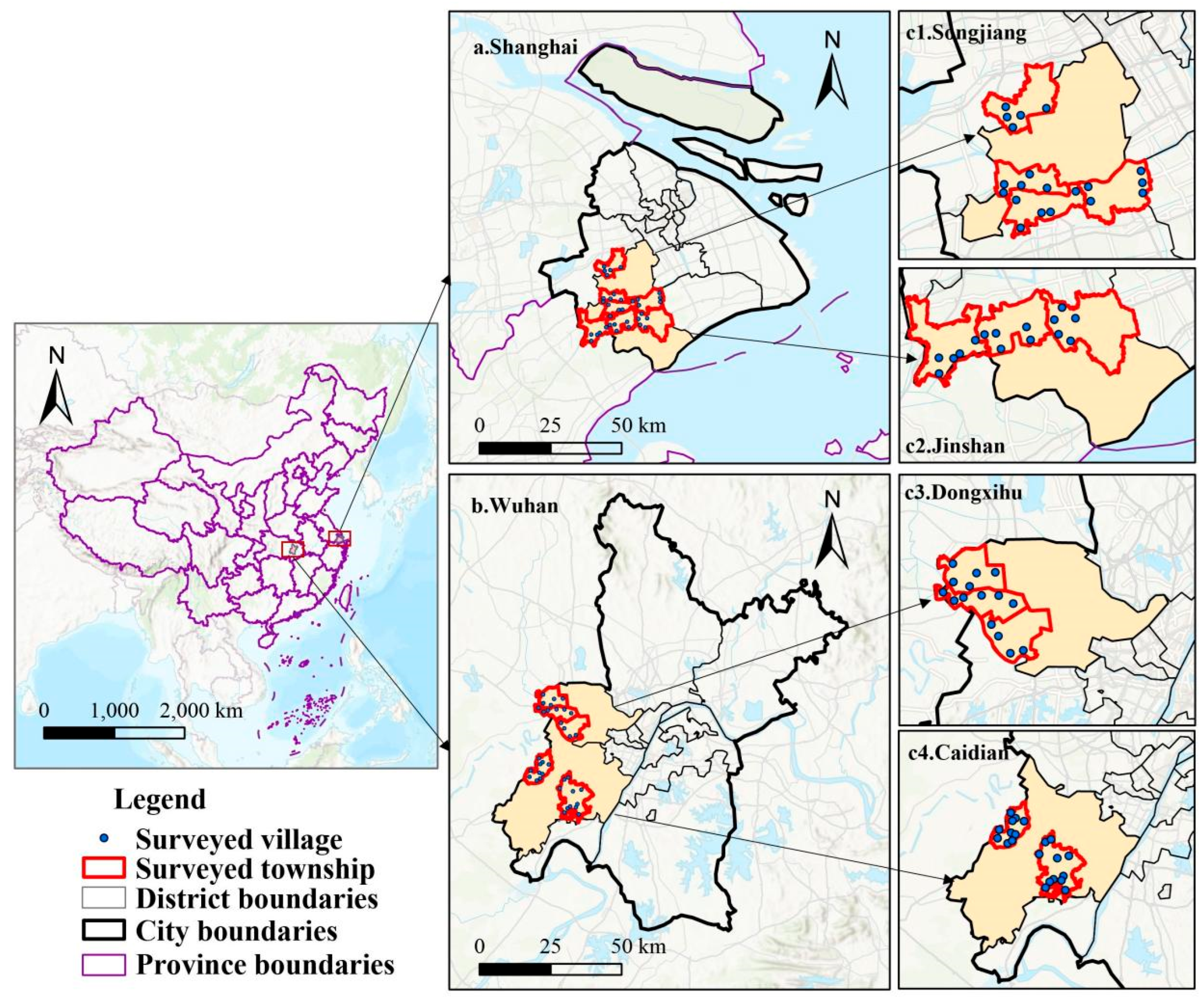

Shanghai, China’s foremost international economic and financial hub, boasts unparalleled economic vitality. As one of China’s megacities, Shanghai’s urbanization rate reached 89.46% by 2023, ranking first nationwide. The Songjiang District, situated in the southwest of Shanghai and renowned as the city’s “Root”, exemplifies Shanghai’s strategic focus on suburban new town development. Housing the national Shanghai Songjiang Economic and Technological Development Zone, this district epitomizes Shanghai’s historical prosperity and significance. Renowned as a key hub for premium rice production and a vital source of fresh produce for its residents, Songjiang District upholds a rich agricultural heritage, earning it the moniker “land of fish and rice”. Notably, it boasts the highest concentration of large-scale rice cultivation in Shanghai and ranks among the nation’s top grain-producing regions, underscoring the pivotal role of agriculture in its economy. Pioneering rural land reform in China, some local residents have opted to relinquish their contracted land in exchange for compensation. Similarly, the Jinshan District, a prominent agricultural region in Shanghai, stands out for its robust agricultural output and diverse crop resources. In recent years, it has strategically pivoted towards urban agriculture, earning recognition as Shanghai’s premier national modern agricultural industrial park.

Wuhan stands out as the sole sub-provincial mega-city within the six central provinces of China, playing a pivotal role as the central city in central China and serving as the strategic core for the advancement of central China, as well as the nucleus in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. The Caidian District and Dongxihu District, located on the periphery of the urban area, exhibit dynamic urban–rural interactions, undergoing significant transformations in the human-land relationship. Historically reliant on agriculture, Caidian District serves as a crucial source of agricultural and sideline products for the central urban area of Wuhan, blending features of urban development zones with traditional agricultural production areas due to its unique geographical positioning. Conversely, Dongxihu District has evolved into an economic and technological development zone at the vanguard of urbanization, earning the distinction in 2013 as the sole national-level development zone named “Lin kong gang” in China. It also hosts the largest cluster of state-owned farms in Wuhan, with its rural landscape shaped by a distinctive history of agricultural reclamation. In recent years, both districts have intensified the amalgamation of urban and rural industries, leading to a steady increase in urbanization rates. By 2023, Wuhan achieved an urbanization rate of 84.79% among its permanent residents. A significant portion of rural inhabitants have sought employment opportunities outside agriculture, with the majority of farmers’ income stemming from non-agricultural sectors. The proportion of non-agricultural workers in Caidian and Dongxihu Districts has reached 75.00% and 61.34%, respectively. Furthermore, numerous rural households have secured stable non-agricultural jobs and have even relocated to urban centers. The prevalent trend of non-agriculturalization has laid the groundwork for the relinquishment of contracted farmland (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Location of the study area.

The urban areas of Shanghai and Wuhan, characterized by economic development, offer abundant non-agricultural employment opportunities and income sources. Rural inhabitants in these regions have increased access to urban social insurance and receive comparatively higher payment levels. Given the existing demand and fulfillment of requisite conditions for withdrawing contracted land, it is imperative to facilitate this process at an opportune juncture. For developed regions with high levels of urbanization, the timely introduction of a reasonable mechanism for withdrawing from contracted farmland can not only promote the transformation and development of modern agriculture but also enhance the welfare of farmers relinquishing their land. These areas can serve as pilot zones for China’s farmland withdrawal initiatives. Therefore, selecting these regions as research samples holds significant representativeness.

3.2. Data Sources

The data were collected through a field survey conducted by the research group among farmers in Songjiang District and Jinshan District of Shanghai, as well as Caidian District and Dongxihu District of Wuhan between June and September 2023. The survey encompassed 12 townships and 72 villages, utilizing a combination of random and quota sampling methods. Rural households were selected for in-home interviews based on cultivated land resource utilization and household livelihood development status, with a sampling rate ranging from 8% to 10% of permanent households in each village. Trained investigators conducted face-to-face interviews with household heads or knowledgeable adults, with each interview lasting approximately 60 min. The survey addressed various aspects, including household characteristics, development attitudes, livelihood capital, social security, land management, transfer, and withdrawal. Out of 1748 distributed questionnaires, 1630 valid responses were obtained after excluding incomplete or contradictory data, as well as responses from initially landless farmers and non-local tenant farmers, resulting in an overall effective rate of 93.25%. Excluding farmers forced to withdraw from land due to expropriation, the final sample size was 1478, comprising 415 respondents from Songjiang District, 303 from Jinshan District, 444 from Caidian District, and 316 from Dongxihu District.

The surveyed samples indicate a predominant presence of male householders, comprising 86.34% of the population. The majority of individuals are aged over 60, representing 74.17%, aligning with the prevalent trend of aging labor forces in rural areas. Educational attainment among householders is generally modest, with 86.41% having education levels below junior high school. Family sizes typically range from 3 to 6 individuals, accounting for 69.24% of the households. The majority of farmers operate on less than 5 mu of contracted land, encompassing 64.37%, with an average per capita landholding of approximately 1 mu. Notably, 84.58% of sampled families report annual incomes exceeding 100,000 yuan, with a per capita annual income of 52,400 yuan. Additionally, 65.92% of families own urban housing, indicating relatively high income levels among farmers in the Yangtze River Delta and the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. However, agricultural income remains low for most households, with 78.84% earning below 20,000 yuan. In essence, the survey samples offer a representative portrayal of farmers in the prosperous eastern and central regions, effectively reflecting the prevailing socioeconomic realities.

3.3. Variables

(1) Dependent variables. The concept of “withdrawal of contracted land” as defined by previous studies [4,5,6] involves farmers reallocating agricultural land voluntarily and proactively. This process entails farmers returning land contractual management rights to the village collective or transferring them to others in a voluntary and compensated manner, resulting in property income for the farmers. This voluntary and compensated withdrawal facilitates the free exchange of land among farmers. It is important to note that this definition excludes scenarios where land contractual management rights are lost due to household registration changes, such as for educational purposes, or through government-mandated expropriation for public interest reasons. The establishment of voluntary and compensated principles integrates land contractual management rights withdrawal into market-oriented practices.

In a sense, the long-term temporary withdrawal of land management rights constitutes a “delayed withdrawal”. Once conditions are ripe, this “delayed withdrawal” may evolve into a “full withdrawal”, meaning the permanent and complete relinquishment of land contracting rights, which is irreversible. This study categorizes the degree of contracted land withdrawal into four levels ranging from minimal to maximal: no withdrawal, short-term withdrawal, long-term withdrawal, and permanent withdrawal, each associated with incremental variables from 0 to 3 accordingly (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definition of the degree of contracted land withdrawal.

(2) Independent variables. China’s social security framework comprises two distinct systems: social insurance for urban and rural residents, and social insurance for urban employees. These systems differ notably in terms of the covered population and the extent of coverage. Drawing from the preceding theoretical framework, the “percentage of household members enrolled in urban social security” is identified as the key metric. This metric denotes the ratio of household members enrolled in urban social security to the total number of household members.

(3) Mediating variables. Family pension income is chosen as mediating variables to investigate how urban social security influences the degree of farmers’ land withdrawal and to assess the mediating role of their pension income.

(4) Control variables. Drawing from pertinent literature and prior studies [13,14,18,24], control variables encompass individual, family, village, and geographical factors. Individual characteristics comprise gender, age, and education level of the household head. Family characteristics include family size, number of dependents, total income, proportion of agricultural income, urban housing, family financial obligations and savings, land expropriation experience, amount of contracted land, and perception of land ownership. Village characteristics consist of village collective income, healthcare facilities, and ecological conditions. Geographical location is indicated by regional dummy variables, with Shanghai serving as the control group and Wuhan as the reference group.

The meanings and explanations of the above variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the variables.

3.4. Methodology

Farmers’ decisions to relinquish contracted land involve a complex process. Drawing on existing research [13,14], the degree of land withdrawal can be treated as an ordered multi-class variable with increasing levels, constituting a typical multiple choice problem. This makes the multilevel ordered Probit model suitable for empirical analysis. This model can be used to examine the correlation between urban social security factors and control variables. such as individual characteristics, household endowments, and location conditions, and the degree of withdrawal from contracted farmland.

where denotes the degree of contracted land withdrawal, signifies urban social security, accounts for a set of control variables, denotes the constant term, and represent the parameters to be estimated, and stands for the random error term.

To investigate the specific pathway by which urban social security impacts the withdrawal of contracted land through pension income, this study employs the methodology proposed by Jiang T [55], a channel testing approach utilized by previous researchers [56,57]. The model for testing the specific mechanism is outlined as follows:

the variable denoted as serves as an intermediary, specifically reflecting pension income. The definitions of and align with those outlined in Equation (1), where signifies the constant term, and denote the parameters under estimation, and represents the random error term.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of the Descriptive Results

In the survey sample, the family member participation rate in urban social security is 57.23%. Specifically, the participation rate among rural households in Shanghai stands at 68.35%, while in Wuhan, it is 46.72%. On average, each family has 2–3 members enrolled in the insurance program. Notably, 56.90% of rural households have a participation rate exceeding 50%, with Shanghai exhibiting a significantly higher rate compared to Wuhan. The average pension income per family is 31,100 yuan, with rural households in Shanghai and Wuhan receiving 39,000 yuan and 23,500 yuan, respectively. The suburban areas of Shanghai and Wuhan, characterized by robust economic development, boast a per capita annual income of 52,400 yuan. Additionally, the average non-agricultural employment income for rural households amounts to 164,600 yuan. This substantial non-agricultural employment income provides robust financial backing for insurance participation, allowing for diversified participation methods and higher payment levels, consequently leading to elevated pension levels. Regarding land withdrawal patterns, surveyed rural households predominantly opt for medium to long-term or permanent withdrawal. Families participating in urban social security exhibit a higher degree of land withdrawal compared to non-insured families.

4.2. Analysis of the Impact of Social Security on the Withdrawal from Contracted Farmland

Prior to regression analysis, a multicollinearity test was performed to verify the precision and reliability of the model. The variance inflation factor (VIF) for each variable was below 10, and the tolerance exceeded 0.1, confirming the absence of multicollinearity issues among the chosen variables and ensuring the suitability of conducting further regression analysis. Additionally, to mitigate the impact of heteroscedasticity, robust standard errors were applied to all equations. The estimated results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of model estimation.

The regression analysis of Model (1) presented in Table 3 demonstrates that urban social security, the primary explanatory variable, exhibits a statistically significant positive association at the 1% confidence level. This significance persists in Model (2) after incorporating additional control variables related to individual, household, village, and location characteristics. This result confirms that urban social security significantly promotes the withdrawal of contracted farmland by households. Specifically, the higher the proportion of household members participating in urban social security, the greater the degree of farmland withdrawal, thereby validating Hypothesis H1. The reasons are as follows: First, in rural China, contracted land serves not only as a production factor but also fulfills crucial social security functions, particularly in old-age support. For farmers, land is regarded as their “last resort”; even if migrant work fails, they can return to farming to sustain basic livelihoods. Urban social security systems (including pension, medical, and unemployment insurance) provide farmers with institutionalized, socialized risk mitigation mechanisms. Once farmers enroll in urban social security programs, they gain a more stable and reliable social safety net that can replace land as a resource, significantly reducing their dependence on land. This, in turn, increases both their willingness and ability to exit farming. Second, relinquishing contracted farmland is an irreversible major decision that carries significant future risks. Urban social security effectively alleviates farmers’ concerns and uncertainties about their future livelihoods by providing stable and predictable pensions or medical reimbursement. This heightened sense of security has become one of the key factors driving their decision to withdraw their land. Third, the variable “proportion of household members covered by urban social security” reflects the extent to which the entire household has transitioned from agriculture to urban life and the level of security they enjoy. A higher proportion of participation in urban social security indicates that the household’s economic activities and life cycle have become more deeply integrated into the urban system, no longer reliant on rural land. For example, if not only the younger members of a household have urban social security, but the elderly also enjoy urban pension insurance, the household faces a lower risk of completely exiting the land contracting system. Consequently, they are more likely to choose full rather than partial withdrawal, achieving a more thorough exit from contracted land. The marginal effects outlined in Table 4 reveal that a 1% increase in the proportion of insured household members corresponds to a 25% rise in the likelihood of farmers opting for permanent land withdrawal, further substantiating the validity of Hypothesis H1.

Table 4.

Results of marginal effects.

Regression results reveal several significant factors influencing farmland withdrawal by rural households. Firstly, the gender of the household head exerts a significantly negative impact on farmland withdrawal at a 5% confidence level, with women showing a greater tendency to migrate to urban areas for employment opportunities, thereby altering the family’s economic trajectory [58]. Secondly, an increase in the number of dependents within a family is significantly positively associated with farmland withdrawal at a 10% confidence level, indicating that higher economic pressures, driven by a larger population burden of elderly and children, lead to a greater likelihood of labor force migration in pursuit of higher income as migrant workers. Moreover, the proportion of agricultural income within the family and the extent of contracted farmland both exhibit significantly negative impacts on farmland withdrawal. A higher reliance on agricultural income strengthens farmers’ attachment to the land, discouraging permanent withdrawal. Conversely, households with lower agricultural income or smaller land holdings are more inclined to permanently withdraw from contracted farmland to seek higher non-agricultural income due to challenges in achieving economies of scale and low output efficiency. Furthermore, the ownership of urban housing by a household significantly positively influences farmland withdrawal at a 10% confidence level, reflecting a stronger material foundation and a shift in focus towards urban living, thereby increasing the likelihood of permanent farmland withdrawal. Household debt and savings also play significant roles, with negative coefficients indicating that debt raises expectations of compensation for farmland withdrawal, thereby inhibiting withdrawal. Additionally, land expropriation has a significantly positive impact on farmland withdrawal at a 1% confidence level, as higher compensation levels for land expropriation elevate farmers’ expectations for farmland withdrawal [59]. Particularly in developed urban areas, where compensation standards for farmland withdrawal align with those for land expropriation, farmers with prior land expropriation experiences are more inclined to permanently withdraw from contracted farmland.

The village collective dividend exhibits statistical significance at the 1% confidence level, showing a positive coefficient. By retaining entitlement to village collective earnings, farmers can continue to receive dividend income even after relinquishing land, thereby increasing their likelihood of permanent land withdrawal. The health conditions within the village negatively influence farmers’ land withdrawal decisions at the 5% confidence level, whereas the ecological environment exerts a positive impact on the extent of land withdrawal. The geographical location variable demonstrates significance at the 1% confidence level, displaying a positive coefficient. In comparison to Wuhan, Shanghai boasts higher urbanization levels, elevated land prices, and more comprehensive social security measures. Consequently, farmers in Shanghai exhibit a greater propensity to permanently withdraw from land to capitalize on their assets, leading to increased levels of land withdrawal.

4.3. Analysis of the Mechanism of Pension Income on the Withdrawal from Contracted Farmland

According to the theoretical analysis in the previous text, an increase in the proportion of families participating in urban social security will raise the pension income of farmers, and thereby enhance the degree of their withdrawal from contracted land. This section aims to empirically examine the aforementioned potential causal pathways. Following the methodological framework outlined by Jiang T [55] and other scholars for testing pathways, we will assess the influence of the primary explanatory variable on the mediating variable M. To address concerns regarding the adequacy of the theoretical justification for the causal relationship between M and Y, we will also investigate the impact of M on Y to complement the existing evidence of association [60].

The regression analysis from Models (3) and (4) in Table 3 demonstrates a significant positive impact of participation in the urban social security system on the pension income of rural households. Increased participation by family members correlates with higher future pension benefits, leading these households to increasingly rely on socialized pension schemes. Specifically, a rise in the proportion of individuals enrolled in urban endowment insurance signifies greater savings and accumulation for future pensions or the commencement of pension receipt. This directly elevates the overall pension income of the household, bolstering its resilience against pension-related risks. To enhance the quality of elderly care or pursue a more comfortable urban life, farmers are more inclined to permanently withdrawal their contracted land, and the degree of their land withdrawal is even higher.

Furthermore, as a stable source of monetized income, pension benefits can effectively replace the economic returns generated by land. If the pension income is substantial enough to meet or surpass the net income obtained from farming the land, the opportunity cost of retaining and working the land will rise considerably. Through rational decision-making, farmers will opt to permanently relinquish their rights to the contracted land. The income impact resulting from the provision of old-age security represents the most immediate and influential motivating factor, effectively mitigating the enduring challenge of “land-based old-age support” in rural China.

The findings above confirm Hypotheses H2 and H3 posited in this study, demonstrating that engagement in urban social security significantly influences the degree of farmland contract relinquishment by enhancing the pension income of rural households. Within this framework, pension income serves as a discernible mediator, functioning as a conduit and linkage mechanism.

4.4. Robustness Test

To assess the reliability of the model estimations, this study conducts comprehensive tests employing the variable replacement method, model modification method, and sub-sample regression method. Initially, adjustments are made to the measurement approach of the dependent variable. The dependent variables in Model (1) and Model (2) are substituted with the binary variable “participation in urban social security” (Yes = 1, No = 0), followed by a reiteration of the regression analysis. Subsequently, Model (4) and Model (6) are recalculated using the ordered Logit model to scrutinize the influence of model specification on the outcomes. Lastly, following established research protocols [61,62], the total sample is partitioned into Shanghai and Wuhan sub-samples based on geographical location, with separate model re-estimations conducted to explore potential regional heterogeneity effects on the core findings. The outcomes presented in Table 5 and Table 6 demonstrate that across various robustness tests, the estimated coefficients’ directions and the significance levels of the principal variables align closely with the regression results in Table 3. This consistency indicates the robustness of the empirical findings, further bolstering the support for Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3. The results confirm that participating in urban social security can significantly increase farmers’ pension income, thereby enhancing the degree of their contracted land withdrawal. That is, pension income plays a significant mediating role in the process in which urban social security affects the withdrawal of contracted land.

Table 5.

Results of robustness tests with variable replacement and alternative methods.

Table 6.

Results of robustness tests for Sub-samples.

5. Discussion

This study reveals the intrinsic transmission mechanism of “social security → pension income → withdrawal from contracted land,” offering new theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence for addressing the dilemma of “relying on land for retirement.” It particularly clarifies the pivotal role of pension income as an intermediary variable, thereby filling gaps in existing research on mechanism discussions. The study also find that farmers’ withdrawal from contracted land is the result of multiple factors acting in concert. Beyond pension security, household characteristics such as female-headed households, high dependency ratios, low agricultural income share, and ownership of urban housing are associated with stronger withdrawal tendencies. Among institutional and environmental factors, experiences with land expropriation, village collective dividend income, and favorable rural ecological environments all significantly promote farmers’ permanent withdrawal from contracted land. Notably: First, female-headed households exhibit greater willingness to relinquish contracted land, likely stemming from their prioritization of urban employment and educational resources. This reflects gender differences in decision-making, indicating that policies should pay greater attention to gender-specific needs. Second, village collective dividend rights and land expropriation compensation mechanisms significantly promote permanent land abandonment, indicating that securing land income is central to reducing farmers’ risk perceptions. Third, developed regions like Shanghai exhibit higher land withdrawal degree than Wuhan due to robust social security systems and higher land prices, highlighting the need to address regional imbalances in the process of relinquishing contracted land.

It should also be noted that this study focuses on the suburban areas of megacities like Shanghai and Wuhan, where economic development is relatively advanced. Farmers in these regions exhibit lower dependence on land, resulting in higher degree of land withdrawal. It is recommended that the government prioritize implementing land withdrawal policies in developed suburban rural areas, establishing them as the leading zones for reform. Subsequently, the policy should be gradually rolled out to general agricultural areas and remote underdeveloped regions in a phased manner, thereby systematically guiding farmers to actively withdraw from their contracted land.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This study integrates social security, pension income, and the withdrawal of contracted farmland by rural households into a theoretical framework. Utilizing survey data from rural households in the outskirts of Shanghai and Wuhan, an empirical model is employed to investigate the influence and mechanisms of urban social security and pension income on the withdrawal of contracted farmland by rural households. The key findings are as follows: Initially, the data from the sample indicate that 57.23% of rural households participate in urban social security, with over half of these households having an insurance participation rate exceeding 50%. Insured families exhibit significantly higher levels of pension income compared to uninsured families. Econometric results suggest that a higher proportion of insured individuals correlates with a more pronounced withdrawal of contracted farmland by rural households. Urban social security diminishes rural households’ reliance on land by offering a stable alternative security, thereby empirically supporting the concept of “social security replacing land security.” Subsequently, regression analysis confirms that engagement in urban social security significantly boosts the withdrawal of contracted farmland. Specifically, for every 1% rise in the proportion of insured family members, the likelihood of rural households permanently withdrawing from farmland increases by 25%. Lastly, the mediating effect analysis demonstrates that pension income plays a crucial mediating role in the relationship between social security and the withdrawal of contracted farmland. Participation in urban social security increases the pension income level of farmers, thereby enhancing the extent to which they withdraw from their contracted land. Pension income, as a stable source of cash flow, effectively replaces the economic benefits derived from land, encouraging farmers to permanently relinquish their contracted farmland. This mechanism discovery provides crucial insights for optimizing rural land withdrawal policies.

To facilitate the orderly withdrawal of farmers from their contracted land, it is essential to establish a comprehensive urban–rural integrated social security system. This system should gradually supplant the traditional role of land in providing old-age and other forms of security, thereby encouraging farmers to voluntarily and permanently relinquish their contracted land. The following policy recommendations are proposed: First, increase farmers’ participation in social insurance to reduce their dependence on land. This can be achieved through multiple measures, including moderately relaxing eligibility requirements for urban social security, optimizing cross-regional transfer and continuation mechanisms, and encouraging enterprises to enroll migrant workers in urban social insurance programs. Concurrently, rural social security benefits should be further enhanced, and effective integration with the urban social security system should be strengthened to provide institutional support for the orderly withdrawal of contracted farmland. Second, enhance farmers’ pension security and increase compensation standards for relinquishing contracted land. Efforts should be made to continuously improve pension benefits for both urban and rural residents. Specific measures include raising the standard of basic pension distribution, increasing policy subsidies for rural pension contributions, and strengthening publicity and guidance to encourage farmers to opt for higher contribution tiers, enabling them to genuinely rely on pensions for their retirement security. Additionally, compensation standards for relinquishing contracted land should be moderately increased to enhance policy appeal and effectively encourage farmers to permanently withdraw from their contracted land. Finally, improve supporting policies and rights protection mechanisms. Integrate land withdrawal policies with urban–rural integration measures such as employment placement, housing security, and vocational training, prioritizing the needs of female-headed households and families with multiple dependents to facilitate their smooth transition from agriculture to urban life. This study also reveals that village collective dividends significantly encourage farmers to relinquish their contracted land. It is essential to ensure that farmers who withdraw their land can continue to enjoy the right to share in the distribution of village collective assets under certain conditions. This would alleviate their concerns and encourage long-term or permanent withdrawal from contracted land.

Author Contributions

Y.S.: data collection, organization, methodology, and writing the original draft. Y.C.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, and supervision. X.T.: investigation, review and editing the draft. W.Z.: review and charting. All of the authors contributed to improving the quality of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 71974068; 72374080).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, X.Y. Withdrawal of farmers’ land contracting right: Objectives, difficulties and conditions. Economist 2022, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.W.; Gu, H.Y. Study on the voluntary and compensated withdrawal mechanism of rural land contract right based on the roles of government and market. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2023, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, T.; Gu, H. Farmers’ Decision-Making Regarding Land under Economic Incentives: Evidence from Rural China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B. The legal dilemma and institutional construction of the land contractual management rights withdrawal mechanism. Rural. Econ. 2017, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B.L.; Zou, B.L.; He, Y.M. Adverse selection in the duration of agricultural land leases: An empirical analysis based on farmer surveys from Nine Provinces. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2017, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Ju, K.X. Has the confirmation of farmland rights increased farmers’ willingness to withdraw from contracted land: Based on analysis of the sample data of 935 farmers households in 15 Counties of 3 Provinces. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 21, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, M.H.; Zhang, H. Influence of family life cycle on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from land contract right. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Lu, Q.; Li, L.; Sarkar, A.; Li, H. Does Labor Transfer Improve Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Farming?—A Bivariate Probit Modeling Approach. Land 2023, 12, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lu, H.; Xu, D. “Absorbing in” or “Crowding out”: The Impact of High-Standard Farmland Construction on Farmers’ Land Withdrawal. Land Use Policy 2025, 157, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggi, M.; Sardonini, L.; Viaggi, D. The Effects of the Common Agricultural Policy on Exit Strategies and Land Re-Allocation. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.Q.; Ding, Z.C.; Zhou, M.; Li, J. Factors influencing farmers’ willingness to abdicate the land contract right: A meta-regression analysis. J. China Agric. Univ. 2021, 26, 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.L.; Liu, X.Y. A study on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from land contract rights and its influencing factors: Based on Micro-level survey data from Hubei Province. Jianghan Trib. 2017, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Zhao, Q.D.; Song, C.X. Study on farmers’ withdrawal willingness of land contract right and choice of compensation method from the perspective of intergenerational difference: Based on a questionnaire survey of 1012 rural households in 11 provinces. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 24, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.W.; Yang, Z.C. Farmers’ characteristics, regional differences and farmers’ willingness to withdraw the Land. Econ. Surv. 2022, 39, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.W.; Gu, H.Y. Urban housing, farmland dependence and land contract right exit. J. Manag. World 2016, 9, 55–69+187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.H.; Cai, Y.Y. Scale of land expropriation, stability of non-agricultural employment and withdrawal of rural land contract right in suburban areas: A case study of Wuhan city. China Land Sci. 2025, 39, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.S.; Kong, X.Z. Are farmer renting out farmland inclined to abdicate their land contract right. China Soft Sci. 2020, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.Y.; Ye, X.Q. Rural-household differentiation, rural land circulation and the withdrawal. Reform 2019, 32, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Su, B.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y. How Does Nonfarm Employment Stability Influence Farmers’ Farmland Transfer Decisions? Implications for China’s Land Use Policy. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.Q.; Liu, R.; Cao, G.Z. The ownership of contracted land cognition and farmers’ willingness to exit their contracted land under the background of urbanization in China. Urban Dev. Stud. 2018, 25, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.Q.; Miao, H.M.; Zhu, J.F. Non-agricultural employment, cognition of contracted land ownership and farmers’ withdrawal from contracted land. J. China Agric. Univ. 2022, 27, 258–271. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.W.; Gu, H.Y. Tenure intensification, development appeal and farmers’ willingness to hold land contract right. Financ. Trade Res. 2019, 30, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.H.; Mi, Y.S.; Xue, Z.J. Land expropriation experience, illusion of value, and the willingness to withdraw contract rights among off-farm rural households. China Land Sci. 2025, 39, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, H.P.; Sun, Y.M. Factors affecting farmers’ willingness and mode of farmland abandonment for rural households land contractual operation right. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.S. Agricultural mechanization, nonfarm work and farmers’ willingness to abdicate contracted land. China Population. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Jin, X.Y. The impacts of resource endowment and the social-security system on migrant workers’ willingness of land disposal: From the perspective of rational choice theory. China Rural. Surv. 2015, 16–25+95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.B. Are aged farmers willing to renounce the rights of contract and management of the land: Based on the survey of farmers in Henan Province. Econ. Surv. 2019, 36, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.W.; Wang, P.; Guo, X.M. Research on the mechanism for the paid withdrawal of land contractual operating rights by farmers with different endowments: Based on the experience and insights from the urban district of Neijiang City, Sichuan Province. Rural. Econ. 2019, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.X.; Zhao, J.J. Rural contracted land withdrawal: Theoretical logic and choice preferences. Rural. Econ. 2019, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.Q.; Zhou, M. The abdication of land contract right: Policy evolution, connotation and key problem. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ding, Y.W.; Guo, X.M. Stakeholder interests in the withdrawal of agricultural land management rights under China’s three-right division framework: Demands, structures and mediation pathways. Rural. Econ. 2021, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.; Zheng, Y. How to Promote the Withdrawal of Rural Land Contract Rights ? An Evolutionary Game Analysis Based on Prospect Theory. Land 2022, 11, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Song, H.Y. Study on the exit mechanism of contractual right of rural lands. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 17, 74–84+158. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.Q.; Tan, J.; Lei, J.Z. Comparative study on models for the paid withdrawal of farmers’ contracted land. Rural. Econ. 2017, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, Y.N.; Sun, Y.Q.; Jiang, T.H. To keep or not to keep the farmland: Incentives and barriers to farmers’ decisions in urbanizing China. Habitat Int. 2022, 130, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Wang, C.P.; Sun, Z.X. Impact of rural-household differentiation on the exit willingness of farmland contracting and management rights. China Land Sci. 2015, 29, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Wang, L. Does Participation in Social Security Increase Chinese Farmers’ Willingness of Homestead Withdrawal? Land 2025, 14, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, J. Do Social Pension and Family Support Affect Farmers’ Land Transfer? Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jin, S.; Tang, Z.; Awokuse, T. The Effect of Pension Income on Land Transfers: Evidence from Rural China. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2022, 71, 333–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Cheng, P.; Liu, Z. Social Security, Intergenerational Care, and Cultivated Land Renting Out Behavior of Elderly Farmers: Findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey. Land 2023, 12, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.R.; Hong, G.L.; Zheng, L.Y. The social pension insurance level and the development of agricultural land rental market: Based on the dual perspectives of both quantity and quality. Issues Agric. Econ. 2022, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, C.T. The influence of pension security on farmers’ willingness to withdraw from farmland contract and management right: Based on the survey of 580 households in Five provinces. J. Guangxi Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 56, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, D.; Yang, C.R. Research on the impact of social security on individual income disparities. Stat. Decis. 2023, 39, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, D. Analysis of the Impact of Social Insurance on Farmers in China: A Study Exploring Subjective Perceptions of Well-Being and the Mechanisms of Common Prosperity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1004581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H. How Does China’s New Rural Pension Scheme Affect Agricultural Production? Agriculture 2022, 12, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Y.; Liu, S.; Guo, Q.H. Will the increase in land rent restrain the withdrawal of smallholders’ land contracting rights: Based on the survey of contracting rights withdrawal pilots. Res. Econ. Manag. 2022, 43, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Cheng, Y.Y. Is Household burden a constraint on the transfer of agricultural land. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2019, 4, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jansuwan, P.; Zander, K.K. What to do with the farmland? Coping with ageing in rural Thailand. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 81, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Li, F. Non-agricultural employment, social security and farmer’s land transfer: An empirical analysis based on 476 farmers in 30 Towns and 49 Villages. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho Filho, I.E. Old-Age Benefits and Retirement Decisions of Rural Elderly in Brazil. J. Dev. Econ. 2008, 86, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M. Public Policy and Extended Families: Evidence from Pensions in South Africa. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2003, 17, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.J.; Li, F. The impact of pension income on the labor supply of the rural elderly: Empirical analysis based on CHARLS. Issues Agric. Econ. 2017, 38, 63–71+111. [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston, K.; Sun, A.; Zhan, Z. The Impact of Rural Pensions in China on Labor Migration. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2018, 32, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, C. The Power of Social Pensions: Evidence from China’s New Rural Pension Scheme. Am. Econ. J.-Appl. Econ. 2021, 13, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, T. Mediating effects and moderating effects in causal inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Q.; Wang, C.S.; Yuan, Z.H. How can green finance enhance food security: Perspectives from rural human capital and agricultural industry agglomeration. J. Univ. Jinan (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 34, 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J. Digital economy to improve urban economic efficiency: Theoretical mechanism and path choice: A case study of Yangtze River Delta cities. J. Soochow Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 45, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mohabir, N.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, R. Chinese floating migrants: Rural-urban migrant labourers’ intentions to stay or return. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.P.; Cai, Y.Y.; Xie, J.; Tian, X.; Yang, Q. The influencing factors of suburban farmers’ land expropriation expectation from the perspective of livelihood pattern differentiation: A case study of Caidian District, Wuhan City. Res. Agric. Mod. 2023, 44, 410–420. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.L.; Liu, H.C.; Long, Z.N.; Tang, X.D. Enterprise digital transformation and the geographic distribution of supply chain. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2023, 40, 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.Y.; Zheng, Y.F.; Xu, J.X. Outgoing experience, farmland transfer behavior and rural-urban migration: An empirical analysis based on CHIP2013. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2021, 3, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.Y.; Chen, Y.R.; Hu, W.Y.; Mei, Y.; Yuan, K.H. A study on the relationship between social capital, cultivated land value cognition and farmers’ willingness to pay for cultivated land protection: An empirical analysis based on a moderated mediator model. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2019, 29, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).