Abstract

Land taxation, mainly the Land and Building Tax (LBT), is a critical revenue source for local governments in Indonesia, yet its contribution remains suboptimal due to inefficiencies in assessment and administration. This study focuses on the Lebak Regency to optimize the Sales Value of Taxable Objects (SVTO) assessment, a key determinant of LBT revenue. Using spatial analysis, Land Value Zones (LVZ), and socio-economic data, the research evaluates assessment ratios to identify discrepancies between SVTO and market values. Adjustments to SVTO are proposed based on spatial patterns, such as land use and infrastructure, and the Index of Developing Villages (IDV). Findings reveal significant disparities between assessed and market values, with assessment ratios ranging from 1% to 267%. Simulations indicate potential LBT revenue of IDR 224.7 billion under full compliance, compared to IDR 44.22 billion, the 2024 target. Adjustments based on spatial patterns from land use planning and village development indices enhance equity and accuracy in tax assessments, optimizing local revenues. Despite these improvements, the study’s limitations lie in the lack of community validation for the proposed methodology, which is essential to confirm its practicality and acceptance. Future research should address this gap and explore household-level dynamics, including tax affordability and spending patterns, to enhance policy inclusivity and align taxation systems with local socio-economic realities.

1. Introduction

Land taxation constitutes a significant revenue source for local governments across many countries [1,2,3,4]. A notable example of land-based financing, such as property taxes, is in Sub-Saharan African cities, where local authorities increasingly rely on these instruments to strengthen fiscal capacity [5]. Ref. [6] highlights that local governments are the primary beneficiaries of property taxes, which also promote financial independence at the regional level. This financial autonomy is often perceived positively by taxpayers, as it reflects a relationship between locally provided services (e.g., medical units, schools, infrastructure) and property values.

Land value assessment is a critical aspect of land taxation, and assessors are responsible for accurately determining land values within their jurisdictions. They must employ precise and comprehensible valuation methods compatible with computer-based assessment systems to ensure transparency for taxpayers and judicial oversight. Accurate land value assessments are essential for effective taxation systems, as they influence tax amounts levied and revenue collected by local governments. Moreover, such assessments enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of tax collection while ensuring fairness and transparency within property tax systems [7].

Globally, land valuation is conducted using various methods, ranging from traditional to modern approaches. Conventional methods typically rely on individual assessments by professional valuers, where each property is appraised separately based on its market value, with taxes applied proportionally to property values—higher-value properties incur higher taxes [8]. However, these methods become inefficient on a large scale due to significant resource demands in terms of time and labor [9]. Modern valuation methods such as banding and mass appraisal have emerged to address these challenges, leveraging technology to improve efficiency and accuracy. Banding simplifies the process by grouping properties within specific value ranges, thereby reducing administrative costs. While more efficient, these methods face challenges related to fairness, as properties grouped in the same value category may exhibit significant variations in actual values [8].

Sometimes, valuations fail to reflect true market prices, leading to inequities. Disparities in the assessment process can result in an uneven tax burden, where lower-valued properties are often taxed proportionally higher than higher-valued ones. This condition imposes a heavier tax burden on lower-value property owners and can reduce the total revenue received by local governments [10,11,12]. Research by [10] shows the elasticity of effective tax rates relative to property sales prices in the United States is −0.37, indicating that effective tax rates tend to decrease as property prices increase. This negative elasticity suggests that for every 1% increase in property prices, the effective tax rate decreases by 0.37%. The research further revealed that properties in the lowest price decile are subject to an effective tax rate more than twice as high as those in the highest price decile within the same jurisdiction. This phenomenon reflects inequities in the property tax system, where owners of lower-valued properties bear a disproportionately higher tax burden than owners of higher-valued properties.

Equitable assessments ensure that tax burdens are distributed proportionally among property owners in property tax systems. Assessment ratios, which compare assessed property values determined by tax authorities with fair market values, serve as a critical tool for measuring such equity [13,14]. These ratios reflect how property assessments align with actual market prices. According to [15], in jurisdictions implementing property assessments, market value serves as a fair basis for determining tax burdens, as it represents the actual value obtainable in an open market.

Geospatial analysis is a method that utilizes data with geographic or spatial components to inform and support the decision-making process. These data can include satellite imagery, maps, and other location-based information that can be visualized and analyzed to identify patterns, trends, and relationships relevant to the decisions made [16,17]. In the context of taxation, previous studies have shown that geospatial analysis in property tax assessments, such as in the Hauz Khas region of India, successfully created detailed spatial databases that contributed to more accurate property tax calculations [18]. Furthermore, integrating geospatial techniques with advanced statistical methods, such as the Geostatistical Eigenvector Spatial Filter (ESF) combined with modern regression techniques, has proven effective in improving the accuracy of mass property assessments. This approach yields more accurate and understandable results and effectively addresses spatial autocorrelation issues, where property data within an area influence each other [19]. Furthermore, according to [20], advancements in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and machine learning algorithms have significantly enhanced property valuation methods and tax assessment processes.

Previous studies on land taxation have primarily concentrated on uniform valuation methods or top-down policy approaches. For example, ref. [21] examined the relationship between land value and building value, focusing on individual property dynamics rather than regional disparities in land value. Similarly, ref. [22] explored the differential effects of land value taxation across various land use types but did not sufficiently address broader spatial or socio-economic dimensions. Ref. [18] demonstrated the potential of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for improving property tax assessment by enhancing spatial data collection and visualization. However, their approach focused primarily on spatial elements without incorporating other factors, limiting their applicability in addressing inequities in taxation systems. Meanwhile, ref. [23] focused solely on the spatial integration of land and taxation geospatial data using QGIS, effectively addressing differences in file formats and attributes but without considering broader taxation or socio-economic implications.

This study involves analyzing geospatial and attribute data to calculate assessment ratios at the village level, specifically comparing the Sales Value of Taxable Objects (SVTO) (government-assessed land values) with market values. Through this method, the research aims to identify villages with discrepancies in tax values, enabling evaluations of SVTO. The ultimate goal is to adjust SVTO based on assessment ratio results and additional factors, such as village status indices and land-use planning. These adjustments are expected to produce tax values that better reflect market prices, enhance tax equity for taxpayers, and optimize regional revenues through LBT in Rural and Urban Areas. Furthermore, these adjustments provide a foundation for improving data-driven fiscal policies with greater transparency and accuracy.

Context of Indonesia

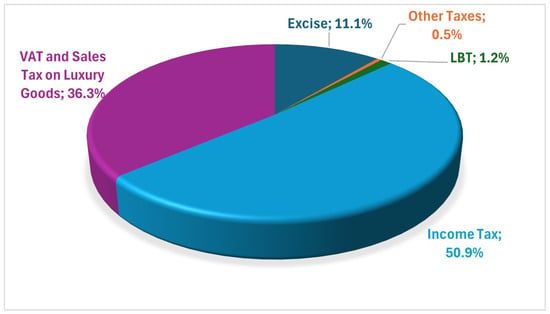

According to the 2023 data from the Indonesia Central Bureau of Statistics, despite the significant potential of LBT, its contribution to state revenue is still relatively low, accounting for only about 1% of total national income. This contribution is much smaller than income tax, Value Added Tax (VAT) and Luxury Goods Tax, and Excise duties. In 2023, although LBT revenue grew by 9.45% compared to 2022, its contribution to total state revenue only reached 1.2%, reflecting stagnation in land tax collection (see Figure 1). One of the main factors contributing to this low contribution is the high level of tax evasion, coupled with the inefficiency of the existing tax administration system. As a result, tax compliance remains low, ranging from 61% to 71% in 2022, which hampers the optimization of property tax revenue despite the sector’s more significant potential to contribute to both national and regional income [24].

Figure 1.

LBT Percentage Compared to Other Taxes [25].

Land taxation, particularly in the form of Land and Building Tax (LBT), is one of the critical sources of revenue in Indonesia’s tax system. The basis for LBT revenue is the Sales Value of Taxable Object (SVTO), which is the average price derived from information on buying and selling transactions [26,27]. This assessment determines the amount of tax that taxpayers must pay, generally based on market prices or comparisons with similar tax objects. As a significant revenue source, land tax has substantial potential to support regional development and promote economic equity across Indonesia [14,28].

However, despite the critical role of land taxation, the existing SVTO assessment system in Indonesia still faces several challenges. The mass assessment process conducted by tax officials sometimes produces inaccurate data, primarily due to limited human resources and the vast area to be covered. Research conducted in several places, such as Tanjungpinang Timur Subdistrict and Pamijahan Village, has shown that SVTO assessments often do not align with actual market values, leading to unfair land tax assessments [14,29].

Land taxation in Indonesia is governed by Law Number 12 of 1994 concerning LBT, and is divided into two categories: LBT for rural and urban sectors and LBT for plantations, forestry, and mining sectors. With the implementation of Law Number 28 of 2009, the authority to collect LBT for the rural and urban sectors was transferred to district/city governments, while other sectors remain managed by the central government through the Directorate General of Taxes. This division of authority aims to strengthen local government’s ability to manage land taxes, expecting to increase revenue and promote equitable development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

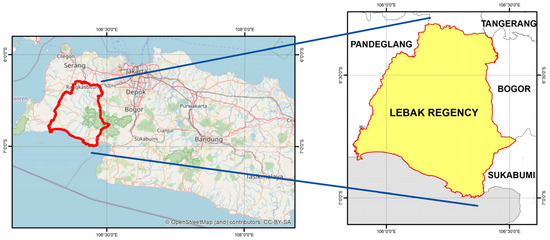

Lebak Regency is one of the regencies in Banten Province, with its capital in Rangkasbitung. Located in the southern part of Banten Province, Serang and Tangerang Regencies border this regency to the north, Bogor and Sukabumi Regencies to the east, the Indian Ocean to the south, and Pandeglang Regency to the west (see Figure 2). Lebak Regency consists of 28 sub-districts and 340 villages. The area is known for its fertile agricultural land in lowlands and mountainous regions, with agriculture dominating the landscape. The agricultural sector plays a significant role in the economy, mainly through rice productivity, which is the leading staple food for the population [30].

Figure 2.

Research study location.

Geographically, Lebak Regency lies between 105°25′–106°30′ E and 6°18′–7°00′ S. The northern part of the regency is characterized by lowland terrain. In contrast, the southern part is mountainous, with Mount Halimun in the southeast as the highest peak, bordering Bogor and Sukabumi Regencies. The people of Lebak, including the Baduy ethnic group, are known for preserving their cultural heritage and traditions and living a unique traditional lifestyle. The Baduy tribe is exempt from land and building taxes, with no tax targets set for Kanekes Village [31]. Most land in Kanekes Village is used communally, and there is no common property development, such as modern housing or commercial buildings. Furthermore, the Baduy people live in harmony with nature, where land use serves economic purposes and aims to maintain ecosystem balance. In addition to the agricultural sector, Lebak Regency has a significant industrial sector. PT Cemindo Gemilang, which operates a cement factory in Bayah, contributes about 89% of all investment activities in the regency, according to data from the Industry and Trade Office of Lebak Regency in 2020. This cement factory is one of the largest and most renowned in the region.

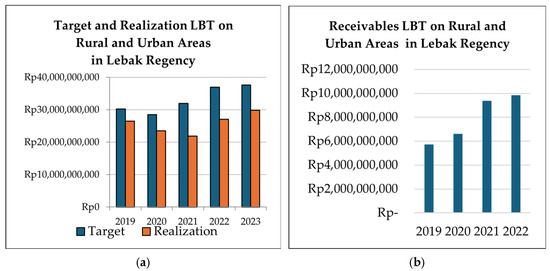

Figure 3 shows that while the realization of LBT on Rural and Urban Areas revenue in Lebak Regency has tended to increase from 2019 to 2023, the total amount still consistently remains below the set target. On the other hand, the accounts receivable graph for LBT in Rural and Urban Areas shows a significant upward trend in tax arrears, from around IDR 6 billion in 2019 to nearly IDR 12 billion in 2022. This situation requires serious attention, enhanced supervision, more effective socialization, and stronger law enforcement to ensure compliance and reduce arrears.

Figure 3.

Graph of (a) Target and Realization, and (b) Receivables of LBT on Rural and Urban Areas in Lebak Regency.

2.2. Research Method

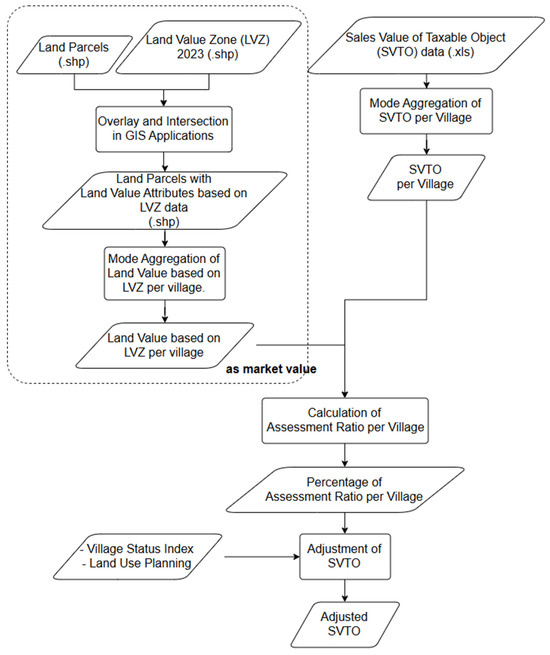

The methodology of this study integrates spatial and attribute data to evaluate the alignment of SVTO with market values, as outlined in the research methodology flowchart (see Figure 4). Land Parcel and Land Value Zone (LVZ) data were processed through spatial analysis to determine land values based on LVZ, considering the market value for each village. Spatial data processing was conducted using QGIS Desktop 3.28.1, an open-source Geographic Information System software that provided advanced tools for spatial analysis. Additionally, tabular data and statistical calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel under an institutional license provided by Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB). SVTO data were then compared to market values by calculating the assessment ratio and identifying discrepancies between the two. Based on the assessment ratio results and data such as the Village Status Index and Land Use Planning, SVTO adjustments were proposed to enhance accuracy and better reflect market conditions, thereby supporting tax equity and optimizing local revenue.

Figure 4.

Research method flowchart.

2.3. Assessment of Market Value per Village

According to the International Association of Assessing Officers IAAO market value accuracy is a key factor in determining the precision of assessment ratio calculations, making it crucial to employ methods capable of accurately representing market values [32]. This study utilizes Land Value Zones (LVZ) data obtained from the Land Office of Lebak Regency to represent land market values. LVZ is developed through a process that integrates transaction data and offers data adjusted to approximate real market prices. LVZ represents a conceptual framework for determining land values based on specific zones. In Indonesia, LVZ determination employs various spatial analysis methods to create zones that reflect real-world land value conditions [33,34]. Article 16, Paragraph (1) of the Government Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia Number 128 of 2015 specifies that LVZ represents the land value (market value) determined by the National Land Agency [35]. LVZ follows the Technical Guidelines for Land Valuation and Land Economy 2024 issued by the Directorate of Land Valuation and Land Economy, Directorate General of Land Procurement and Development, Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/National Land Agency.

The following are key justifications for utilizing LVZ as a representation of market value:

- Alignment with Official Technical Guidelines based on the Technical Guidelines for Land Valuation and Land Economy 2024: LVZ development involves collecting land transactions and offering data adjusted to reflect market prices. As outlined in the technical guidelines, data adjustments are made by reducing prices by a specific percentage based on field analysis. This ensures that the resulting values are more accurate and valid representations of the market.

- Following the guidelines, land prices used in LVZ are processed to represent only land values. For parcels with buildings, land value is derived by subtracting the building’s value, including depreciation, from the total land and building value. This process ensures pure land value, as described in the official guidelines.

- The obtained prices directly represent land values without requiring additional adjustments for vacant land parcels. This aligns with the principle in the technical guidelines that LVZ values should specifically reflect market land values.

Determining land values based on LVZ utilizes GIS applications and begins with two primary datasets. The first dataset is Land Parcels (.shp), which contains information on land parcels in shapefile format. The second dataset is the 2023 Land Value Zones (.shp), which includes the latest land value zone data in the same format. These datasets serve as the foundation for integrating spatial information on land values and land parcels in detail. The next step involves overlay and intersection analysis using GIS applications. This process combines Land Parcel data with LVZ data to assign land value attributes to each parcel based on its value zone. This enables each parcel to “adopt” the land value from the corresponding zone, resulting in a new dataset containing parcels with assigned land value attributes based on LVZ. After the overlay and intersection process, the resulting dataset includes Land Parcels with associated land value attributes. This dataset provides a detailed view of how each parcel has a distinct value determined by its geographic location and assigned value zone.

The subsequent step is mode aggregation, which calculates the most frequently occurring land value within each village’s LVZ data. When dealing with asymmetrical data distributions or significant outliers, the mode serves as a robust central tendency measure [36,37]. The mode, defined as the most frequently occurring value in a dataset [38], is less influenced by extreme values compared to the mean [38,39]. This makes it an appropriate choice for analyzing skewed data or data containing significant outliers, which are often encountered in real-world scenarios [38]. The aggregation simplifies the data, producing a representative LVZ value for each village. This approach ensures standardized and consistent results for analysis at broader administrative levels, such as villages or sub-districts.

The final result of this process is determining land values per village based on LVZ, which are regarded as market values. This output serves various purposes, including land tax analysis, spatial planning, and property policy evaluation. The methodology demonstrates how integrating spatial data and GIS analysis can create accurate land value maps to support data-driven decision-making.

2.4. Assessment of Sales Value of Taxable Object (SVTO) per Village

The data used in this study consist of Sales Value of Taxable Object (SVTO) information obtained from the Revenue Agency of Lebak Regency concerning LBT on Rural and Urban Areas for 2023. The data in Excel format include key details such as Tax Object Numbers, taxpayer information (including names and addresses), object locations, land and building areas, SVTO values, land classifications, total LBT liabilities, and payment due dates. This comprehensive dataset offers valuable insights into taxable objects in the Lebak Regency, enabling analysis of trends and discrepancies in property tax assessments.

Before further analysis, the dataset is cleaned to ensure its accuracy and consistency. This process involves several steps, including identifying and correcting recording errors. This is crucial as datasets often contain missing values, data entry errors, or even undefined outliers. Any inaccuracies or missing data are rectified or removed to ensure that flawed data do not compromise the analysis results. Once the data have been cleaned, the next step involves conducting statistical analysis to determine the mode of SVTO for each village. This ensures that the analysis accurately reflects representative property values and supports reliable conclusions.

2.5. Calculation of Assessment Ratio

The assessment ratio is calculated using a formula [40]:

Assessment Ratio = Assessed Value/Fair Market Value

In this context, the assessed value refers to the property value determined by tax authorities to calculate the tax liability of property owners, whereas the fair market value (FMV) is an estimate of the price a property would likely command if sold in an open and competitive market. In regions with limited or no available transaction data, alternative methodologies are employed to estimate the FMV. One such method is the replacement cost method, which has been utilized in areas such as Zanzibar where market transaction data are not readily available. However, this method has limitations, as it does not fully account for locational value, potentially resulting in a less accurate reflection of market conditions [41]. Alternatively, the mass appraisal model is often employed, a method that systematically divides the area into sub-regions based on land value stratification, assigns corresponding land values to each sub-region, and identifies key factors influencing land value. This approach is widely advocated in situations where transaction data are insufficient, as it provides a more robust and consistent framework for estimating FMV [41]. In the present study, the mass appraisal model is utilized, owing to the availability of Land Value Zones (LVZ) data in Lebak Regency. The LVZ data enable a more precise estimation of land values, as they allow for the stratification of land into distinct value zones that reflect varying market conditions.

If the assessment ratio indicates that the assessed value exceeds the market value by more than 110%, the property is considered over-assessed, suggesting that the owner might be paying higher taxes than warranted. Conversely, if the ratio is below 90%, the property is deemed under-assessed, meaning the owner might be paying less tax than appropriate [40]. Such discrepancies can result in inequities, where some property owners pay taxes disproportionately higher or lower than the actual market value of their properties. Hence, tax authorities must maintain consistent assessment ratios to ensure that all properties are taxed equitably.

The thresholds of 110% and 90% are derived from guidelines established by the International Association of Assessing Officers (IAAO), as outlined in their Standard on Ratio Studies [32]. These guidelines emphasize the importance of uniformity in assessment ratios to ensure fairness and equity in property taxation systems. If the average assessment ratio in a region exceeds 110%, it indicates regressivity, where lower-valued properties bear a disproportionately higher tax burden [13]. Conversely, ratios below 90% reflect progressivity, where lower-valued properties benefit from relatively lower tax burdens. As explained by [15], property assessments that align closely with market values ensure a fair and equitable taxation system among all property owners, thereby preventing disparities in the distribution of tax burdens.

2.6. Adjustment of Sales Value of Taxable Object (SVTO)

2.6.1. Index of Developing Villages (IDV)

Index of Developing Villages (IDV) is a tool used to assess the development level of villages, encompassing social, economic, and environmental dimensions [42]. It is administered by the Directorate General of Village and Rural Development, Ministry of Villages, Development of Disadvantaged Regions, and Transmigration of the Republic of Indonesia. One of the key factors influencing IDV is the economic condition of the village population, particularly concerning poverty levels and their ability to meet basic needs, including the payment of land and building taxes [43]. Therefore, it is essential to consider the IDV status when determining tax policies, especially for villages with low IDV scores, such as Underdeveloped and Very Underdeveloped Villages.

Villages with low IDV statuses often face significant challenges, including poverty, lack of infrastructure, and limited access to basic services. These conditions make the population in such villages highly vulnerable to higher tax burdens. Tax increases in villages with low IDV statuses may worsen the economic situation of the already struggling population, thereby exacerbating social and economic disparities in these areas.

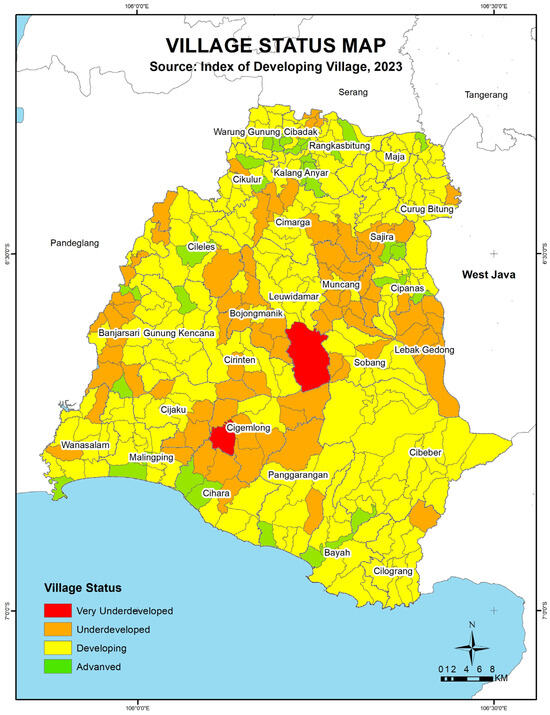

Figure 5 is a map depicting the village status based on the IDV 2023 in Lebak Regency, categorized into advanced, developing, underdeveloped, and very underdeveloped. The map shows that most villages, accounting for 66% of the total, are classified as Developing, with 24% classified as Underdeveloped and 1% as Very Underdeveloped. Only 10% of villages are categorized as Advanced, indicating that many villages in Lebak Regency are still facing challenges in terms of development and welfare.

Figure 5.

Village Status Map of Lebak Regency [44].

2.6.2. Land Use Planning

SVTO is a key indicator in calculating LBT, reflecting the average property value based on fair market transactions. The government determines SVTO by considering spatial planning policies, location, and accessibility. Land use planning, which involves the organization and regulation of land use, plays a critical role in shaping the SVTO of an area. Strategic land use planning policies can enhance a region’s investment appeal, thereby contributing to an increase in SVTO [45].

The influence of land use planning on SVTO is evident in zoning regulations, which divide areas into residential, commercial, industrial, and green space zones. Properties in strategic zones, such as those near business centers or public transportation hubs, tend to have higher SVTO. Conversely, peripheral areas with limited accessibility typically have lower SVTO. Land use planning not only governs zoning but also supports more targeted land management and development, fostering economic growth and [46,47,48].

Infrastructure policies also contribute to the determination of SVTO. Large-scale infrastructure developments, such as toll roads, airports, and public transportation facilities, enhance connectivity and increase the value of nearby properties. Areas that gain improved accessibility often experience a rise in SVTO due to higher demand for properties for economic and social activities. Therefore, land use planning and infrastructure development serve as strategic tools for governments to enhance land and property values across various regions [49].

2.6.3. Calculation of SVTO Adjustment

Adjustments of SVTO are conducted using two distinct approaches: for villages categorized as under-assessed and those categorized as over-assessed. Below are detailed explanations of each approach and their respective calculation methods:

- Under-Assessment Approach

Villages categorized as under-assessed have SVTO lower than their market prices. Adjustments are made using the following formula:

Explanation of Variables:

- Vs: A factor representing the village status, based on the Index of Developing Villages (IDV) 2023;

- SP: A factor representing the spatial structure by the Land Use Planning of Kabupaten Lebak.

The tables below provide values for Village Status (Vs) and Spatial Pattern (SP): Table 1 presents the data for Village Status (Vs), and Table 2 shows the data for Spatial Pattern (SP).

Table 1.

Values for Village Status (Vs).

Table 2.

Values for Spatial Pattern (SP).

Very Underdeveloped Villages are not given an increase in SVTO due to poor economic conditions, high poverty levels, and limited access to basic services and infrastructure, making land value increases unrealistic [42,50]. Underdeveloped Villages are given a multiplier of 10% because, despite facing various challenges, these villages show signs of economic recovery and have the potential for gradual land value increases. Developing Villages with progress in social and economic aspects are given a 50% multiplier, reflecting a higher potential for land value increases as infrastructure and the economy improve. Finally, Advanced Villages, with stable economic conditions and good infrastructure, are given a 100% multiplier, as their land values already reflect market values and have a higher economic appeal [42,50].

Based on the regulation of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/National Land Agency of the Republic of Indonesia, spatial patterns refer to the distribution of spatial designations in an area, including those for protection and cultivation functions. Protected areas are locations designated primarily to preserve the environment, including natural and artificial resources. A Cultivation Area is a space designated primarily for agriculture, relying on the conditions and potential of natural, human, and manufactured resources. The ratio used in this research is based on the area’s function, characteristics, and activities contributing to tax revenue.

- 2.

- Over-Assessment Approach

Villages categorized as over-assessed have SVTO higher than their market prices. Adjustments in this case are made using the formula:

Explanation of Variables:

- Vs: A factor representing the village status, based on the Index of Developing Villages (IDV) 2023 (as listed above);

- SP: A factor representing the spatial pattern by the Land Use Planning of Kabupaten Lebak (as listed above).

Formulas (2) and (3) were developed as an original contribution by the authors to address the under-assessment and over-assessment of SVTO in certain villages, integrating key factors of socio-economic status and land-use planning. The theoretical foundation for this formula lies in studies conducted in Indonesia, which highlight the significant impact of land-use regulations and socio-economic variables on land values. Research on Indonesia’s land-use patterns demonstrates that areas such as urban residential zones, industrial zones, and plantation areas significantly influence land values, with flexible regulatory enforcement and dynamic informal housing systems further shaping this outcome [51]. Moreover, socio-economic factors, including village status, infrastructure quality, and economic activity, have been shown to play critical roles in determining land values. For instance, villages with higher socio-economic progress, as indicated by the 2023 Village Development Index (IDV), tend to have better infrastructure and greater economic potential, resulting in higher land values [52]. The coefficients of 0.5 for both Vs (village status) and SP (spatial pattern) were determined to represent a balanced contribution of socio-economic and land-use variables, supported by empirical testing using 2023 SVTO data and analysis.

After obtaining the adjusted SVTO, which more accurately reflects the market value, the subsequent step involves calculating the increase of SVTO 2023 by comparing the original SVTO with the adjusted SVTO. This procedure is intended to quantify the degree of disparity between the original SVTO and the adjusted SVTO, thereby providing a measure of the alignment between the assessed values and the prevailing market conditions.

The following is the formula for calculating the increase of the original SVTO to the adjusted SVTO.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Assessment of Market Value per Village

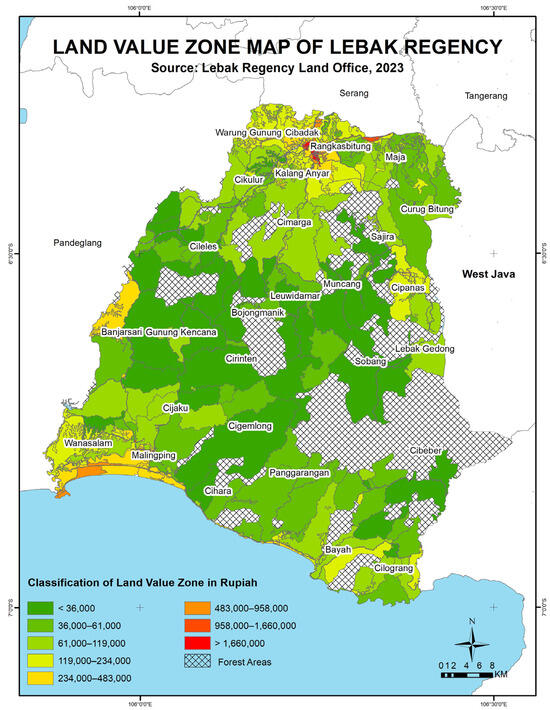

In Lebak Regency, 716,453 land parcels were successfully identified. Figure 6 shows an overlay process that was then conducted on the LVZ map obtained from the Lebak Regency Land Office. This overlay process aimed to integrate the land value attributes from the LVZ map into each identified land parcel, ensuring that every parcel is associated with land value information corresponding to its designated zone.

Figure 6.

Land Value Zone (LVZ) Map of Lebak Regency, 2023 [53].

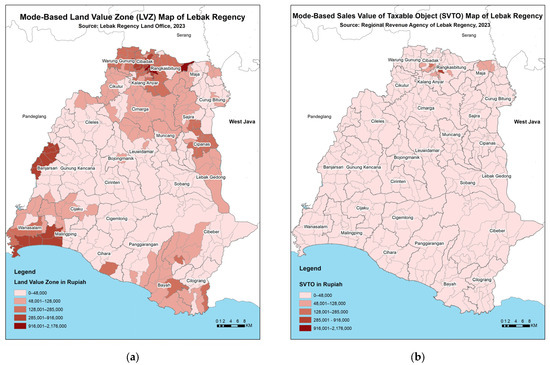

Following the overlay process, land value aggregation was performed using the mode value method for each village. The results of this analysis are presented in Figure 7a, which provides a spatial representation of the land value distribution based on mode value aggregation at the village level.

Figure 7.

Maps: (a) Mode-Based Land Value Zone (LVZ) of Lebak Regency, 2023; (b) Mode-Based Sales Value of Taxable Object (SVTO) of Lebak Regency, 2023.

3.2. Assessment of Sales Value of Taxable Object (SVTO) per Village

Based on data from the Regional Revenue Agency of Lebak Regency in 2023, the total number of registered taxpayers amounted to 774,791. An aggregation analysis using the mode value method was then conducted for the SVTO at the village level. The results of this analysis are visualized in the form of a map, as shown in Figure 7b.

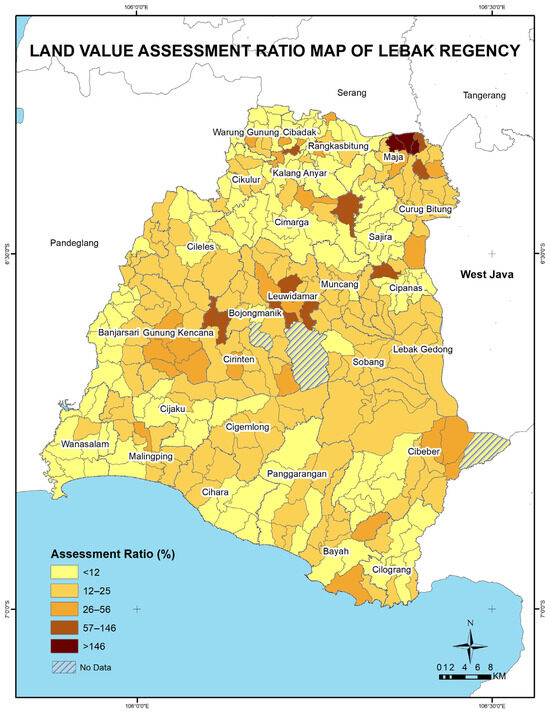

3.3. Calculation of Assessment Ratio

The assessment ratio is calculated by dividing the SVTO’s mode value by the LVZ’s mode value, which is assumed to represent the market value. The result of this calculation is then converted into a percentage to depict the level of alignment between SVTO and market values. Subsequently, the analysis results are visualized as a map, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Land Value Assessment Ratio Map of Lebak Regency, 2023.

In Lebak Regency, the Index of Developing Village (IDV) 2023 reveals that the majority of villages (66%) are categorized as developing, highlighting the region’s transitional stage toward more advanced development. This classification underscores critical challenges in achieving equitable access to public services and fostering sustainable growth, particularly in rural areas. The issue of high land tax assessment ratios further complicates this situation by disproportionately affecting low-income populations, who are predominant in developing villages [54]. Research demonstrates that low-value properties, such as affordable housing, are often over-assessed, leading to an inequitable tax burden that erodes public trust in the taxation system and impedes the establishment of a fair and equitable tax structure [55,56].

High assessment ratios may discourage investment, exacerbate inefficient land use, and contribute to urban sprawl. This scattered development pattern increases the cost of infrastructure and public service provision, thereby limiting economic growth and impeding the equitable distribution of resources [57,58]. Furthermore, inaccurate or inconsistent valuation practices weaken the efficiency of tax administration, reducing taxpayer compliance and increasing the prevalence of tax evasion, especially in economically vulnerable areas. This directly affects the stability of government revenue, which is essential for financing critical public services such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure development [59,60,61].

To address these challenges, it is imperative for the local government of Lebak Regency to adopt accurate and market-aligned land tax assessment practices. Such measures are crucial for promoting a fair taxation system, rebuilding public trust, and ensuring stable government revenues that can support inclusive development and sustainable growth across the region. These efforts will not only improve fiscal equity but also contribute to the economic resilience and overall well-being of communities in developing villages.

3.4. Adjustment of Sales Value of Taxable Object (SVTO)

The adjustment of SVTO in Lebak Regency is carried out based on several key factors, including the assessment ratio, the village status according to the Index of Developing Village (IDV) of 2023, and the land use planning of Lebak Regency. The calculation process follows the methods explained in the previous chapter. Additionally, the determination of SVTO classes is based on the Minister of Finance Regulation No. 150/PMK.03/2010. In this regulation, land is classified into specific classes based on the range of Land Value per square meter. This classification establishes SVTO values uniformly and proportionally based on the land value within a designated zone. The classification of SVTO for land per square meter is outlined in Table 3, and complete data can be found in Appendix A.

Table 3.

SVTO classes are determined based on the Minister of Finance Regulation Number 150/PMK.03/2010.

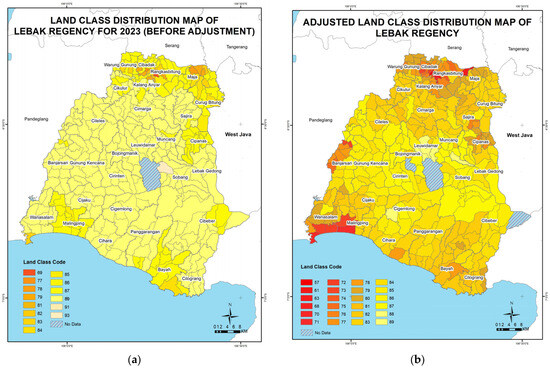

The following is a comparison map of land classes before and after adjustment, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Maps: (a) Land Class Distribution before Adjustment of Lebak Regency; (b) Land Class Distribution after Adjustment of Lebak Regency.

Table 4 summarizes the SVTO adjustments per village in Bajarsari District. Complete data are in Appendix B.

Table 4.

A summary of the SVTO adjustments, both pre-and post-adjustment, along with the associated increases in SVTO and their respective classes, by Minister of Finance Regulation Number 150/PMK.03/2010, for Banjarsari District.

4. Discussion

Based on the Assessment Ratio in Lebak Regency results, the Assessment Ratio values found vary between 1% and 267%. The determination of tax object values shows significant variation, encompassing under-assessment and over-assessment ranges. This indicates that the assessed land values still deviate from the actual market values. Therefore, adjustments are needed for tax object values in both under-assessed and over-assessed categories to reflect more accurate market prices.

Some villages in Lebak Regency, such as Kanekes, home to the Baduy Tribe, do not have SVTO data, as the area is exempt from LBT and is not included in tax assessments. The Baduy people live in harmony with nature, and most of the land in Kanekes is communally used. Meanwhile, the villages of Cimayang and Sinargalih fall within forest areas, which causes them to be excluded from the land value zone map used for determining market values. Villages in the over-assessed category include Curug Badak, Maja Baru, and Pasir Kembang, all located in the Maja district. These villages have SVTO values higher than market prices, signaling the need for adjustments in the land valuation in these areas. Table 5 presents the distribution of assessment ratios for villages in Lebak Regency, categorized into specific categories.

Table 5.

Distribution of Assessment Ratio in Lebak Regency.

Category Explanations:

- Under-Assessed:

- Low Ratio (0–10%): Most villages have SVTO values much lower than market prices, with the highest number of villages in this range;

- Medium Ratio (11–50%): Villages with a more significant gap, but still better than the low ratio;

- High Ratio (51–89%): Villages with SVTO values approaching market values but still lower than actual market prices.

- Over-Assessed: Villages with SVTO values significantly higher than market prices.

After adjusting the SVTO values based on the village status according to the IDV 2023 and spatial patterns from land use planning of Lebak Regency, several changes occurred that reflect the actual conditions on the ground. Some villages saw significant increases in their SVTO after the adjustments, indicating that the land market values in these villages were much higher than the previously assessed SVTO. According to IDV 2023, village status also played an essential role in these adjustments, with villages in better status, such as “advanced”, experiencing higher SVTO increases, reflecting their economic growth and development.

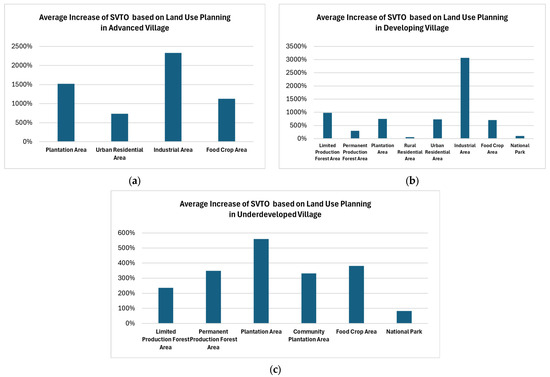

Figure 10 illustrates graphs of the average SVTO increase based on spatial patterns within a single village status, reflecting trends in land value changes after adjustments based on IDV 2023 and the spatial planning of Lebak Regency. The highest increases in SVTO were recorded in Industrial and Plantation Areas, with significant jumps in Mekarsari Village, Rangkasbitung (9125%) due to the presence of large companies such as plywood manufacturers, shoe producers, and activated carbon companies based on the data from the Industry and Trade Office of Lebak Regency in 2020. The “Advanced” category, Plantation Areas in Kalang Anyar, Sukamekarsari, increased by 6104%, indicating improved agricultural productivity. The following is a graph of the average SVTO increase in land use planning for each village status, illustrating the trends based on spatial planning. Some “Underdeveloped” villages experienced a rise in SVTO driven by plantation areas, such as Banjarsari–Jalupang Girang and Banjarsari–Laban Jaya, which recorded increases of 3250%. These villages are predominantly plantation areas, with most land privately owned and having Certificates of Ownership covering areas larger than 1000 m2, enhancing the land’s productivity, as corroborated by spatial data from the official online map provided by the Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/National Land Agency (ATR/BPN) Indonesia through bhumi.atrbpn.go.id. This increase highlights the positive influence of the plantation sector on land values in these areas.

Figure 10.

Graphs of the average SVTO increase in land use planning are (a) advanced villages, (b) developing villages, and (c) underdeveloped villages.

However, not all villages experienced an increase. Some villages experienced a decrease in SVTO after the adjustments, indicating that the SVTO previously set was higher than the actual market value. This decrease occurred in over-assessed areas, suggesting that SVTO adjustments were made to better reflect actual market conditions. These adjustments reduced previously inflated SVTO values to align more proportionally with the real market prices.

The adjustment of SVTO offers a significant opportunity to enhance the revenue potential of LBT for Urban and Rural Areas. The taxable amount for LBT for Urban and Rural Areas is determined based on Article 40 of Law of the Republic of Indonesia No. 1 of 2022 using the following formula [62]:

According to revenue simulations, full compliance (100% coverage) is projected to yield a maximum revenue potential of IDR 224,714,488,585. However, under moderate compliance (60% coverage), the projected revenue declines to IDR 134,828,693,151, and in a low-compliance scenario (20% coverage), the estimated revenue is limited to IDR 44,942,897,717. These findings underscore the critical role of SVTO adjustments in expanding the revenue base, particularly in relation to land. Notably, the SVTO and the physical area of buildings remain unchanged pre- and post-adjustment, thereby exerting a neutral influence on revenue dynamics.

Nevertheless, the revenue target set for 2024 stands at IDR 44,220,000,000, which is substantially below the maximum potential identified through simulation. This discrepancy highlights key challenges, including suboptimal taxpayer compliance, administrative inefficiencies, and potential resistance to the adjusted SVTO. Such factors collectively constrain the realization of the full revenue potential.

5. Conclusions

This research highlights the importance of integrating spatial analysis, land value assessment, and socio-economic factors to improve the effectiveness and fairness of land taxation systems. Spatial analysis plays a crucial role in achieving accurate land value assessments by producing land value maps that reflect actual market conditions, thereby supporting more precise adjustments of the Sales Value of Taxable Objects (SVTO). The Assessment Ratio, calculated as the comparison between SVTO and market values, serves as a key tool for evaluating the fairness of property tax assessments. This analysis identifies areas that are under-assessed (taxable values below market values) or over-assessed (taxable values exceeding market values), ensuring a more equitable distribution of tax burdens among taxpayers. Additionally, this approach enhances transparency, balances tax burdens, and improves the efficiency of the tax administration system.

SVTO adjustments further ensure equitable taxation by integrating spatial patterns derived from land use planning and socio-economic indicators such as the Index of Developing Village (IDV). These adjustments take into account spatial characteristics such as residential areas, industrial zones, plantations, and forests. Areas with high economic potential, such as strategically located residential or industrial zones, are adjusted to reflect their true market values. Conversely, underdeveloped villages or protected zones are assigned lower SVTO to prevent excessive tax burdens. This approach creates a transparent, equitable, and data-driven tax system that aligns with local economic conditions and spatial characteristics.

The potential for revenue enhancement is another significant benefit of SVTO optimization. Simulations indicate that under full tax compliance (100%), potential revenue from the Land and Building Tax (LBT) could reach IDR 224.7 billion, compared to IDR 134.8 billion at 60% compliance and IDR 44.9 billion at 20% compliance. By integrating spatial patterns in land use planning, especially in high-value zones such as industrial and plantation areas, more precise SVTO adjustments can improve tax collection efficiency. This approach not only supports achieving the 2024 revenue target of IDR 44.22 billion but also unlocks greater revenue potential in the future.

However, this study has limitations. Validation of the proposed methodology is still pending responses from the community, which will be essential to confirm the practicality and acceptance of the approach. Additionally, future research should broaden its scope by incorporating other socio-economic factors influencing decision-making at the household and community levels. These factors include the ability to pay taxes, purchasing power, and household expenditure patterns, which could provide deeper insights into the socio-economic dynamics affecting land taxation systems. By including these variables, future studies can offer a more comprehensive analysis and contribute to the development of more inclusive land taxation policies that align with local socio-economic and spatial dynamics.

6. Patents

The Land Value Assessment Ratio Map of Lebak Regency has been officially registered under Intellectual Property Rights (HAKI) with registration number 000777705. This registration was issued and signed by the Minister of Law and Human Rights of the Republic of Indonesia (A.N.), the Directorate General of Intellectual Property, and the Director of Copyright and Industrial Designs.

Author Contributions

Conception and design of the study: A.H., I.M., R.A. and A.P.H.; acquisition of data: S.L.N., N.S.E.P., R.W., P.M. and F.N.C.; analysis and/or interpretation of data: A.H., D.S., A.P.H. and R.A.; drafting the manuscript: S.L.N. and R.W.; revising the manuscript for significant intellectual content: A.H., I.M., A.P.H., R.A. and A.Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Program for Research, Community Service, and Innovation of the Faculty of Earth Science and Technology (PPMI FITB) at the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) for the Fiscal Year 2024, with a funding amount of IDR 100,000,000.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Doddy Irawan, Head of the Regional Revenue Agency of Lebak Regency, for his invaluable support. Our heartfelt thanks also go to The Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/National Land Agency, especially the Lebak Land Agency (BPN Kabupaten Lebak), for providing the essential data for this research. Additionally, we are grateful to the Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering Graduate School of the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) for their unwavering support throughout the research activities.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. SVTO Classes Refer to the Minister of Finance Regulation Number 150/PMK.03/2010

Table A1.

SVTO classes refer to the Minister of Finance Regulation Number 150/PMK.03/2010.

Table A1.

SVTO classes refer to the Minister of Finance Regulation Number 150/PMK.03/2010.

| Class | Land Value Range (IDR/m2) | SVTO (IDR/m2) |

|---|---|---|

| 69 | >573,000–655,000 | 614,000 |

| 70 | >501,000–573,000 | 537,000 |

| 71 | >426,000–501,000 | 464,000 |

| 72 | >362,000–426,000 | 394,000 |

| 73 | >308,000–362,000 | 335,000 |

| 74 | >262,000–308,000 | 285,000 |

| 75 | >223,000–262,000 | 243,000 |

| 76 | >178,000–223,000 | 200,000 |

| 77 | >142,000–178,000 | 160,000 |

| 78 | >114,000–142,000 | 128,000 |

| 79 | >91,000–114,000 | 103,000 |

| 80 | >73,000–91,000 | 82,000 |

| 81 | >55,000–73,000 | 64,000 |

| 82 | >41,000–55,000 | 48,000 |

| 83 | >31,000–41,000 | 36,000 |

| 84 | >23,000–31,000 | 27,000 |

| 85 | >17,000–23,000 | 20,000 |

| 86 | >12,000–17,000 | 14,000 |

| 87 | >8400–12,000 | 10,000 |

| 88 | >5900–8400 | 7150 |

| 89 | >4100–5900 | 5000 |

| 90 | >2900–3500 | 4100 |

| 91 | >2000–2900 | 2450 |

| 92 | >1400–2000 | 1700 |

| 93 | >1050–1400 | 1200 |

Appendix B. A Summary of the SVTO Adjustments, Both Pre- and Post-Adjustment, Along with the Associated Increases in SVTO and Their Respective Classes, in Accordance with Minister of Finance Regulation Number 150/PMK.03/2010

Table A2.

SVTO adjustments, both pre-and post-adjustment, along with the associated increases in SVTO and their respective classes, by Minister of Finance Regulation Number 150/PMK.03/2010.

Table A2.

SVTO adjustments, both pre-and post-adjustment, along with the associated increases in SVTO and their respective classes, by Minister of Finance Regulation Number 150/PMK.03/2010.

| District | Village | SVTO 2023 (IDR) | Land Class 2023 | Adjusted SVTO (IDR) | Adjusted Land Class | SVTO Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banjarsari | Cilegong Ilir | 5000 | 89 | 167,500 | 077 | 3250% |

| Banjarsari | JalupangGirang | 5000 | 89 | 167,500 | 077 | 3250% |

| Banjarsari | Laban Jaya | 5000 | 89 | 167,500 | 077 | 3250% |

| Banjarsari | Lebak Keusik | 5000 | 89 | 234,500 | 075 | 4590% |

| Banjarsari | Cisampih | 5000 | 89 | 134,000 | 078 | 2580% |

| Banjarsari | Cidahu | 14,000 | 86 | 318,250 | 073 | 2173% |

| Banjarsari | Kerta | 5000 | 89 | 77,900 | 080 | 1458% |

| Banjarsari | Bendungan | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Banjarsari | Kertaraharja | 5000 | 89 | 24,000 | 084 | 380% |

| Banjarsari | Tamansari | 5000 | 89 | 24,000 | 084 | 380% |

| Banjarsari | Umbul Jaya | 5000 | 89 | 24,000 | 084 | 380% |

| Banjarsari | Kumpay | 5000 | 89 | 21,600 | 085 | 332% |

| Banjarsari | Bojong Juruh | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Banjarsari | Kadu Hauk | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Banjarsari | Kerta Rahayu | 5000 | 89 | 18,000 | 085 | 260% |

| Banjarsari | Keusik | 5000 | 89 | 16,200 | 086 | 224% |

| Banjarsari | Gunungsari | 5000 | 89 | 14,400 | 086 | 188% |

| Banjarsari | Cibatur Keusik | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Banjarsari | Ciruji | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Banjarsari | Leuwi Ipuh | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Bayah | Pamubulan | 10,000 | 87 | 140,000 | 078 | 1300% |

| Bayah | Darmasari | 10,000 | 87 | 72,100 | 081 | 621% |

| Bayah | Bayah Barat | 10,000 | 87 | 60,800 | 081 | 508% |

| Bayah | Bayah Timur | 10,000 | 87 | 60,800 | 081 | 508% |

| Bayah | Cimancak | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Bayah | Cisuren | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Bayah | Pasir Gombong | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Bayah | Suwakan | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Bayah | Sawarna Timur | 14,000 | 86 | 44,800 | 082 | 220% |

| Bayah | Cidikit | 10,000 | 87 | 25,200 | 084 | 152% |

| Bayah | Sawarna | 27,000 | 84 | 44,800 | 082 | 66% |

| Bojongmanik | Bojongmanik | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Bojongmanik | Parakan Beusi | 5000 | 89 | 14,450 | 086 | 189% |

| Bojongmanik | Harjawana | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Bojongmanik | Kadurahayu | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Bojongmanik | Mekarmanik | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Bojongmanik | Mekarrahayu | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Bojongmanik | Pasir Bitung | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Bojongmanik | Kebon Cau | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Bojongmanik | Cimayang | 5000 | 89 | No Data | No Data | No Data |

| Cibadak | Kadu Agung Timur | 64,000 | 81 | 2,176,000 | 057 | 3300% |

| Cibadak | Mekaragung | 10,000 | 87 | 236,400 | 075 | 2264% |

| Cibadak | Asem Margaluyu | 10,000 | 87 | 182,250 | 076 | 1723% |

| Cibadak | Panancangan | 14,000 | 86 | 157,600 | 077 | 1026% |

| Cibadak | Pasar Keong | 14,000 | 86 | 236,400 | 075 | 1589% |

| Cibadak | Cibadak | 14,000 | 86 | 150,000 | 077 | 971% |

| Cibadak | Asem | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Cibadak | Cimenteng Jaya | 10,000 | 87 | 89,600 | 080 | 796% |

| Cibadak | Bojong Cae | 10,000 | 87 | 80,000 | 080 | 700% |

| Cibadak | Cisangu | 10,000 | 87 | 80,000 | 080 | 700% |

| Cibadak | Malabar | 10,000 | 87 | 51,200 | 082 | 412% |

| Cibadak | Kadu Agung Barat | 103,000 | 79 | 334,900 | 073 | 225% |

| Cibadak | Tambakbaya | 10,000 | 87 | 25,200 | 084 | 152% |

| Cibadak | Kadu Agung Tengah | 160,000 | 77 | 394,000 | 072 | 146% |

| Cibadak | Bojong Leles | 103,000 | 79 | 190,000 | 076 | 84% |

| Cibeber | Ciherang | 5000 | 89 | 112,000 | 079 | 2140% |

| Cibeber | Cibeber | 5000 | 89 | 45,600 | 082 | 812% |

| Cibeber | Cihambali | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cibeber | Cikotok | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cibeber | Hegarmanah | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cibeber | Neglasari | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cibeber | Sukamulya | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cibeber | Warung Banten | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cibeber | Cisungsang | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cibeber | Kujang Jaya | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cibeber | Mekarsari | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cibeber | Wanasari | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cibeber | Cikadu | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cibeber | Citorek Sabrang | 5000 | 89 | 16,200 | 086 | 224% |

| Cibeber | Citorek Tengah | 5000 | 89 | 16,200 | 086 | 224% |

| Cibeber | Gunung Wangun | 10,000 | 87 | 25,200 | 084 | 152% |

| Cibeber | Citorek Kidul | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Cibeber | Citorek Timur | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Cibeber | Situmulya | 10,000 | 87 | 18,000 | 085 | 80% |

| Cibeber | Kujangsari | 10,000 | 87 | 14,400 | 086 | 44% |

| Cibeber | Citorek Barat | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Cibeber | Sirnagalih | 5000 | 89 | No Data | No Data | No Data |

| Cigemblong | Cibungur | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cigemblong | Cigemblong | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cigemblong | Peucangpari | 5000 | 89 | 24,000 | 084 | 380% |

| Cigemblong | Cikadongdong | 5000 | 89 | 21,200 | 085 | 324% |

| Cigemblong | Cikate | 5000 | 89 | 21,200 | 085 | 324% |

| Cigemblong | Wangunjaya | 5000 | 89 | 21,200 | 085 | 324% |

| Cigemblong | Mugijaya | 5000 | 89 | 18,000 | 085 | 260% |

| Cigemblong | Cikaratuan | 5000 | 89 | 14,400 | 086 | 188% |

| Cigemblong | Cikaret | 5000 | 89 | 5000 | 89 | 0% |

| Cihara | Karang Kamulyan | 5000 | 89 | 121,500 | 078 | 2330% |

| Cihara | Pondok Panjang | 5000 | 89 | 34,200 | 083 | 584% |

| Cihara | Cihara | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cihara | Mekarsari | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cihara | Panyaungan | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cihara | Ciparahu | 5000 | 89 | 25,650 | 084 | 413% |

| Cihara | Barunai | 5000 | 89 | 24,000 | 084 | 380% |

| Cihara | Citepuseun | 5000 | 89 | 18,000 | 085 | 260% |

| Cihara | Lebak Peundeuy | 5000 | 89 | 18,000 | 085 | 260% |

| Cijaku | Mekarjaya | 5000 | 89 | 32,000 | 083 | 540% |

| Cijaku | Cihujan | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cijaku | Kandangsapi | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cijaku | Kapunduhan | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cijaku | Sukasenang | 5000 | 89 | 25,600 | 084 | 412% |

| Cijaku | Cimenga | 5000 | 89 | 24,000 | 084 | 380% |

| Cijaku | Ciapus | 5000 | 89 | 19,200 | 085 | 284% |

| Cijaku | Cijaku | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Cijaku | Cipalabuh | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Cijaku | Cibeureum | 5000 | 89 | 18,000 | 085 | 260% |

| Cikulur | Anggalan | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cikulur | Muara Dua | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cikulur | Pasir Gintung | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cikulur | Parage | 5000 | 89 | 38,400 | 083 | 668% |

| Cikulur | Sukadaya | 5000 | 89 | 38,400 | 083 | 668% |

| Cikulur | Tamanjaya | 5000 | 89 | 38,400 | 083 | 668% |

| Cikulur | Cigoong Selatan | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cikulur | Cigoong Utara | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cikulur | Sukaharja | 5000 | 89 | 38,400 | 083 | 668% |

| Cikulur | Muncang Kopong | 10,000 | 87 | 38,400 | 083 | 284% |

| Cikulur | Sumur Bandung | 10,000 | 87 | 54,400 | 082 | 444% |

| Cikulur | Cikulur | 10,000 | 87 | 45,600 | 082 | 356% |

| Cikulur | Curug Panjang | 10,000 | 87 | 32,000 | 083 | 220% |

| Cileles | Cikareo | 5000 | 89 | 45,600 | 082 | 812% |

| Cileles | Gumuruh | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cileles | Prabu Gantungan | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cileles | Cileles | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cileles | Doroyon | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cileles | Margamulya | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cileles | Cipadang | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cileles | Pasindangan | 5000 | 89 | 20,250 | 085 | 305% |

| Cileles | Kujangsari | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Cileles | Mekarjaya | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Cileles | Banjarsari | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Cileles | Parung Kujang | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Cilograng | Cibareno | 5000 | 89 | 112,000 | 079 | 2140% |

| Cilograng | Pasir Bungur | 5000 | 89 | 112,000 | 079 | 2140% |

| Cilograng | Lebak Tipar | 5000 | 89 | 57,400 | 081 | 1048% |

| Cilograng | Cireundeu | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cilograng | Gunung Batu | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cilograng | Cijengkol | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cilograng | Cikamunding | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cilograng | Cilograng | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cilograng | Cikatomas | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cilograng | Girimukti | 5000 | 89 | 24,000 | 084 | 380% |

| Cimarga | Girimukti | 20,000 | 85 | 32,000 | 083 | 60% |

| Cimarga | Margajaya | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cimarga | Karya Jaya | 5000 | 89 | 57,400 | 081 | 1048% |

| Cimarga | Cimarga | 5000 | 89 | 49,200 | 082 | 884% |

| Cimarga | Jayasari | 5000 | 89 | 61,500 | 081 | 1130% |

| Cimarga | Sangkanmanik | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cimarga | Intenjaya | 5000 | 89 | 41,000 | 083 | 720% |

| Cimarga | Sudamanik | 5000 | 89 | 38,400 | 083 | 668% |

| Cimarga | Jayamanik | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cimarga | Margaluyu | 5000 | 89 | 32,000 | 083 | 540% |

| Cimarga | Mekarmulya | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Cimarga | Sarageni | 5000 | 89 | 28,800 | 084 | 476% |

| Cimarga | Margatirta | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Cimarga | Mekarjaya | 10,000 | 87 | 41,000 | 083 | 310% |

| Cimarga | Sangiang Jaya | 5000 | 89 | 19,200 | 085 | 284% |

| Cimarga | Tambak | 5000 | 89 | 32,000 | 083 | 540% |

| Cimarga | Gunung Anten | 5000 | 89 | 14,400 | 086 | 188% |

| Cipanas | Cipanas | 10,000 | 87 | 152,000 | 077 | 1420% |

| Cipanas | Bintang Resmi | 10,000 | 87 | 206,550 | 076 | 1966% |

| Cipanas | Luhur Jaya | 10,000 | 87 | 112,000 | 079 | 1020% |

| Cipanas | Harum Sari | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Cipanas | Haur Gajrug | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Cipanas | Jayapura | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Cipanas | Sipayung | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Cipanas | Talaga Hiang | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Cipanas | Bintangsari | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Cipanas | Giriharja | 10,000 | 87 | 64,000 | 081 | 540% |

| Cipanas | Malangsari | 10,000 | 87 | 108,800 | 079 | 988% |

| Cipanas | Girilaya | 10,000 | 87 | 18,900 | 085 | 89% |

| Cipanas | Pasir Haur | 10,000 | 87 | 18,900 | 085 | 89% |

| Cipanas | Sukasari | 10,000 | 87 | 16,200 | 086 | 62% |

| Cirinten | Cibarani | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cirinten | Karangnunggal | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Cirinten | Cirinten | 5000 | 89 | 21,600 | 085 | 332% |

| Cirinten | Kadudamas | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Cirinten | Badur | 5000 | 89 | 16,200 | 086 | 224% |

| Cirinten | Datarcae | 5000 | 89 | 16,200 | 086 | 224% |

| Cirinten | Parakan Lima | 5000 | 89 | 16,200 | 086 | 224% |

| Cirinten | Campaka | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Cirinten | Karoya | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Cirinten | Nangerang | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Curug Bitung | Cidadap | 10,000 | 87 | 36,000 | 083 | 260% |

| Curug Bitung | Cilayang | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Curug Bitung | Lebak Asih | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Curug Bitung | Sekarwangi | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Curug Bitung | Curug Bitung | 14,000 | 86 | 33,600 | 083 | 140% |

| Curug Bitung | Guradog | 20,000 | 85 | 33,600 | 083 | 68% |

| Curug Bitung | Mayak | 14,000 | 86 | 24,000 | 084 | 71% |

| Curug Bitung | Candi | 27,000 | 84 | 44,800 | 082 | 66% |

| Curug Bitung | Ciburuy | 27,000 | 84 | 44,800 | 082 | 66% |

| Curug Bitung | Cipining | 27,000 | 84 | 36,000 | 083 | 33% |

| Gunungkencana | Gunung Kencana | 5000 | 89 | 25,650 | 084 | 413% |

| Gunungkencana | Gunung Kendeng | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Gunungkencana | Tanjungsari Indah | 5000 | 89 | 19,800 | 085 | 296% |

| Gunungkencana | Bojong Koneng | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Gunungkencana | Bulakan | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Gunungkencana | Ciakar | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Gunungkencana | Cicaringin | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Gunungkencana | Ciginggang | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Gunungkencana | Cimanyangray | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Gunungkencana | Cisampang | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Gunungkencana | Kramatjaya | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Gunungkencana | Sukanegara | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Kalanganyar | Sukamekarsari | 2450 | 91 | 152,000 | 077 | 6104% |

| Kalanganyar | Sangiang Tanjung | 5000 | 89 | 152,000 | 077 | 2940% |

| Kalanganyar | Cikatapis | 14,000 | 86 | 295,500 | 074 | 2011% |

| Kalanganyar | Kalang Anyar | 10,000 | 87 | 136,000 | 078 | 1260% |

| Kalanganyar | Pasirkupa | 5000 | 89 | 57,400 | 081 | 1048% |

| Kalanganyar | Cilangkap | 10,000 | 87 | 112,000 | 079 | 1020% |

| Kalanganyar | Aweh | 103,000 | 79 | 128,000 | 078 | 24% |

| Lebakgedong | Lebak Sangka | 5000 | 89 | 33,800 | 083 | 576% |

| Lebakgedong | Ciladeun | 5000 | 89 | 32,000 | 083 | 540% |

| Lebakgedong | Banjar Irigasi | 5000 | 89 | 25,600 | 084 | 412% |

| Lebakgedong | Banjarsari | 5000 | 89 | 22,400 | 085 | 348% |

| Lebakgedong | Lebak Gedong | 5000 | 89 | 22,400 | 085 | 348% |

| Lebakgedong | Lebak Situ | 5000 | 89 | 12,800 | 086 | 156% |

| Leuwidamar | Kanekes | No Data | No Data | No Data | No Data | No Data |

| Leuwidamar | Jalupang Mulya | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Leuwidamar | Lebak Parahiang | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Leuwidamar | Leuwidamar | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Leuwidamar | Wantisari | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Leuwidamar | Marga Wangi | 5000 | 89 | 38,400 | 083 | 668% |

| Leuwidamar | Cisimeut | 5000 | 89 | 21,600 | 085 | 332% |

| Leuwidamar | Cibungur | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Leuwidamar | Bojong Menteng | 5000 | 89 | 7000 | 088 | 40% |

| Leuwidamar | Sangkan Wangi | 5000 | 89 | 7000 | 088 | 40% |

| Leuwidamar | Cisimeut Raya | 5000 | 89 | 6000 | 088 | 20% |

| Leuwidamar | Nayagati | 5000 | 89 | 6000 | 088 | 20% |

| Maja | Binong | 10,000 | 87 | 89,600 | 080 | 796% |

| Maja | Sindang Mulya | 14,000 | 86 | 89,600 | 080 | 540% |

| Maja | Sangiang | 10,000 | 87 | 48,000 | 082 | 380% |

| Maja | Gubugan Cibeureum | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Maja | Padasuka | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Maja | Tanjungsari | 14,000 | 86 | 48,000 | 082 | 243% |

| Maja | Buyut Mekar | 14,000 | 86 | 44,800 | 082 | 220% |

| Maja | Cilangkap | 14,000 | 86 | 36,000 | 083 | 157% |

| Maja | Mekarsari | 27,000 | 84 | 36,000 | 083 | 33% |

| Maja | Maja | 48,000 | 82 | 64,000 | 081 | 33% |

| Maja | Pasir Kacapi | 36,000 | 83 | 36,000 | 083 | 0% |

| Maja | Curug Badak | 103,000 | 79 | 77,250 | 080 | −25% |

| Maja | Maja Baru | 103,000 | 79 | 77,250 | 080 | −25% |

| Maja | Pasir Kembang | 128,000 | 78 | 96,000 | 079 | −25% |

| Malingping | Bolang | 10,000 | 87 | 324,800 | 073 | 3148% |

| Malingping | Sukamanah | 10,000 | 87 | 440,800 | 071 | 4308% |

| Malingping | Rahong | 10,000 | 87 | 278,400 | 074 | 2684% |

| Malingping | Malingping Selatan | 20,000 | 85 | 440,800 | 071 | 2104% |

| Malingping | Senanghati | 10,000 | 87 | 57,400 | 081 | 474% |

| Malingping | Cipeundeuy | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Malingping | Sangiang | 10,000 | 87 | 32,000 | 083 | 220% |

| Malingping | Cilangkahan | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Malingping | Kadujajar | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Malingping | Pagelaran | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Malingping | Sukaraja | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Malingping | Sumber Waras | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Malingping | Kersaratu | 10,000 | 87 | 24,000 | 084 | 140% |

| Malingping | Malingping Utara | 20,000 | 85 | 44,800 | 082 | 124% |

| Muncang | Ciminyak | 5000 | 89 | 49,200 | 082 | 884% |

| Muncang | Mekarwangi | 5000 | 89 | 32,000 | 083 | 540% |

| Muncang | Sindangwangi | 5000 | 89 | 32,000 | 083 | 540% |

| Muncang | Muncang | 5000 | 89 | 21,600 | 085 | 332% |

| Muncang | Girijagabaya | 5000 | 89 | 14,400 | 086 | 188% |

| Muncang | Pasir Nangka | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Muncang | Sukanagara | 10,000 | 87 | 25,600 | 084 | 156% |

| Muncang | Cikarang | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Muncang | Leuwi Coo | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Muncang | Pasireurih | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Muncang | Tanjungwangi | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Muncang | Jagaraksa | 5000 | 89 | 5400 | 089 | 8% |

| Panggarangan | Panggarangan | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Panggarangan | Mekarjaya | 5000 | 89 | 32,000 | 083 | 540% |

| Panggarangan | Cibarengkok | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Panggarangan | Cimandiri | 5000 | 89 | 33,600 | 083 | 572% |

| Panggarangan | Situregen | 5000 | 89 | 45,600 | 082 | 812% |

| Panggarangan | Jatake | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Panggarangan | Sindangratu | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Panggarangan | Sogong | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Panggarangan | Gunung Gede | 5000 | 89 | 24,000 | 084 | 380% |

| Panggarangan | Sukajadi | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Panggarangan | Hegarmanah | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Rangkasbitung | Mekarsari | 14,000 | 86 | 1,291,500 | 063 | 9125% |

| Rangkasbitung | Muara Ciujung Barat | 27,000 | 84 | 1,632,000 | 061 | 5944% |

| Rangkasbitung | Nameng | 10,000 | 87 | 243,000 | 075 | 2330% |

| Rangkasbitung | Citeras | 10,000 | 87 | 170,100 | 077 | 1601% |

| Rangkasbitung | Sukamanah | 10,000 | 87 | 145,800 | 077 | 1358% |

| Rangkasbitung | Pabuaran | 10,000 | 87 | 120,000 | 078 | 1100% |

| Rangkasbitung | Pasir Tanjung | 10,000 | 87 | 112,000 | 079 | 1020% |

| Rangkasbitung | Rangkasbitung Barat | 64,000 | 81 | 687,000 | 068 | 973% |

| Rangkasbitung | Rangkasbitung Timur | 20,000 | 85 | 213,750 | 076 | 969% |

| Rangkasbitung | Jatimulya | 48,000 | 82 | 213,750 | 076 | 345% |

| Rangkasbitung | Cijoro Pasir | 36,000 | 83 | 150,000 | 077 | 317% |

| Rangkasbitung | Cimangeunteung | 10,000 | 87 | 33,600 | 083 | 236% |

| Rangkasbitung | Narimbang Mulia | 103,000 | 79 | 285,000 | 074 | 177% |

| Rangkasbitung | Kolelet Wetan | 14,000 | 86 | 36,000 | 083 | 157% |

| Rangkasbitung | Muara Ciujung Timur | 614,000 | 69 | 1,509,750 | 061 | 146% |

| Rangkasbitung | Cijoro Lebak | 103,000 | 79 | 150,000 | 077 | 46% |

| Sajira | Sajira Mekar | 5000 | 89 | 136,000 | 078 | 2620% |

| Sajira | Sajira | 10,000 | 87 | 190,000 | 076 | 1800% |

| Sajira | Bungurmekar | 5000 | 89 | 72,100 | 081 | 1342% |

| Sajira | Mekarsari | 5000 | 89 | 72,100 | 081 | 1342% |

| Sajira | Pajagan | 5000 | 89 | 89,600 | 080 | 1692% |

| Sajira | Calung Bungur | 5000 | 89 | 51,500 | 082 | 930% |

| Sajira | Paja | 5000 | 89 | 72,100 | 081 | 1342% |

| Sajira | Sukajaya | 5000 | 89 | 51,500 | 082 | 930% |

| Sajira | Ciuyah | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Sajira | Sindangsari | 5000 | 89 | 41,000 | 083 | 720% |

| Sajira | Parungsari | 10,000 | 87 | 44,800 | 082 | 348% |

| Sajira | Sukarame | 5000 | 89 | 21,600 | 085 | 332% |

| Sajira | Maraya | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Sajira | Margaluyu | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Sajira | Sukamarga | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Sobang | Hariang | 1200 | 93 | 25,200 | 084 | 2000% |

| Sobang | Majasari | 5000 | 89 | 25,200 | 084 | 404% |

| Sobang | Cirompang | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Sobang | Sindanglaya | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Sobang | Sukamaju | 5000 | 89 | 18,900 | 085 | 278% |

| Sobang | Sinar Jaya | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Sobang | Sukajaya | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Sobang | Sukaresmi | 5000 | 89 | 13,500 | 086 | 170% |

| Sobang | Ciparasi | 5000 | 89 | 14,000 | 086 | 180% |

| Sobang | Sobang | 5000 | 89 | 10,800 | 087 | 116% |

| Wanasalam | Sukatani | 5000 | 89 | 375,900 | 072 | 7418% |

| Wanasalam | Wanasalam | 5000 | 89 | 375,900 | 072 | 7418% |

| Wanasalam | Bejod | 5000 | 89 | 112,000 | 079 | 2140% |

| Wanasalam | Cikeusik | 5000 | 89 | 112,000 | 079 | 2140% |

| Wanasalam | Cipedang | 5000 | 89 | 140,000 | 078 | 2700% |

| Wanasalam | Cisarap | 5000 | 89 | 100,000 | 079 | 1900% |

| Wanasalam | Parung Panjang | 5000 | 89 | 89,600 | 080 | 1692% |

| Wanasalam | Muara | 36,000 | 83 | 510,150 | 070 | 1317% |

| Wanasalam | Karangpamindangan | 5000 | 89 | 57,400 | 081 | 1048% |

| Wanasalam | Ketapang | 5000 | 89 | 57,400 | 081 | 1048% |

| Wanasalam | Cilangkap | 5000 | 89 | 41,000 | 083 | 720% |

| Wanasalam | Cipeucang | 5000 | 89 | 44,800 | 082 | 796% |

| Wanasalam | Parungsari | 5000 | 89 | 14,000 | 086 | 180% |

| Warunggunung | Sindangsari | 10,000 | 87 | 182,250 | 076 | 1723% |

| Warunggunung | Baros | 10,000 | 87 | 150,000 | 077 | 1400% |

| Warunggunung | Warung Gunung | 10,000 | 87 | 136,000 | 078 | 1260% |

| Warunggunung | Pasir Tangkil | 10,000 | 87 | 120,000 | 078 | 1100% |

| Warunggunung | Campaka | 20,000 | 85 | 236,400 | 075 | 1082% |

| Warunggunung | Banjarsari | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Warunggunung | Jagabaya | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Warunggunung | Padasuka | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Warunggunung | Sukaraja | 10,000 | 87 | 96,000 | 079 | 860% |

| Warunggunung | Sukarendah | 10,000 | 87 | 38,400 | 083 | 284% |

| Warunggunung | Selaraja | 36,000 | 83 | 136,000 | 078 | 278% |

| Warunggunung | Cibuah | 36,000 | 83 | 96,000 | 079 | 167% |

References

- Hughes, C.; Sayce, S.; Shepherd, E.; Wyatt, P. Implementing a land value tax: Considerations on moving from theory to practice. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Kumar, R.R.; Stauvermann, P.J. Taxation of Land and Economic Growth. Economies 2021, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brülhart, M.; Bucovetsky, S.; Schmidheiny, K. Chapter 17—Taxes in Cities. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Duranton, G., Henderson, J.V., Strange, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 5, pp. 1123–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasotskaya, N.; Stashina, Y.; Ilyin, V. Audit of The Land Tax of An Economic Entity. Ekon. I Upr. Probl. Resheniya 2023, 5/2, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrisford, S.; Cirolia, L.R.; Palmer, I. Land-based financing in sub-Saharan African cities. Environ. Urban. 2018, 30, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischel, W.A. Homevoters, Municipal Corporate Governance, and the Benefit View of the Property Tax. Natl. Tax J. 2001, 54, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidanset, P.; Elkins, A.; Rakow, R.; Rearich, J.; Quintos, C. Practitioner’s panel paper on land valuation guidance. J. Hous. Econ. 2022, 58, 101880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimmer, F.; Mccluskey, W.; Connellan, O. Valuation Banding-An International Property Tax Solution? J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2001, 20, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichek, Y.O.; Lando, Y.O.; Bielieva, K.K. The Mass Appraisal Models for Residential Real Estate. Ukr. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2023, 4, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.R. Reassessing the Property Tax. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demianyshyn, V.; Horyn, V. Property Tax as A Tool For Financial Regulation of Public Welfare. World Financ. 2020, 3, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, O. Housing Crisis and Vertical Equity of the Property Tax in a Market Value–based Assessment System. Public Financ. Rev. 2013, 42, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAAO. Standard on Property Tax Policy; IAAO: Kansas, MO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yanto, M. Analisis Tingkat Akurasi Penetapan Njop pada Pajak Bumi dan Bangunan terhadap Nilai Pasar dengan Metode Assessment Sales Ratio pada BPPRD Kota Tanjungpinang. Jurnal Riset dan Ekonomi. 2023, 3, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmillen, D.P. Assessment Regressivity A Tale of Two Illinois Counties. Land Lines 2011, 23, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Butko, I. Model and method of making management decisions based on the analysis of geospatial information. Adv. Inf. Syst. 2021, 5, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, N.; Scarlat, C. An Overview of AI And Geospatial Data Towards Improved Strategic Decisions and Automated Business Decision Process. In Proceedings of the Towards Increased Business Resilience: Facing Digital Opportunities and Challenges, Bucharest, Romania, 16–17 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, S.K.; Meraj, G.; Kanga, S.; Farooq, M.; Kranjčić, N.; Đurin, B.; Sudhanshu. Designing Geographic Information System Based Property Tax Assessment in India. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, M.; Lo, D.; Davis, P.; McCord, J.; Hermans, L.; Bidanset, P. Applying the Geostatistical Eigenvector Spatial Filter Approach into Regularized Regression for Improving Prediction Accuracy for Mass Appraisal. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Syafaruddin, S. Property Taxes and Their Implications on the Real Estate Market: A Literature Review. Adv. Tax. Res. 2024, 2, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tideman, N.; Plassmann, F. The effects of changes in land value on the value of buildings. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018, 69, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Differential effects of land value taxation. J. Hous. Econ. 2018, 39, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, B.; Daniel; Willyanto, S.; Irwansyah, E. Integration of Land and Tax Geospatial Data with Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Based Clustering. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society (ICISS), Bandung, Indonesia, 4–5 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samudra, A.A. Property Tax in Indonesia: A Proposal for Increasing Land and Building Tax Revenue Using the System Dynamics Simulation Method. J. Tax Reform 2024, 10, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]