Bridging the Gap: Misaligned Perceptions of Urban Agriculture and Health Between Planning and Design Experts and Urban Farmers in Greater Lomé, Togo

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. UA Dynamics in Greater Lomé

1.2. The Role of Expert Planners

1.3. State of the Art and Contributions of the Study

2. Methods

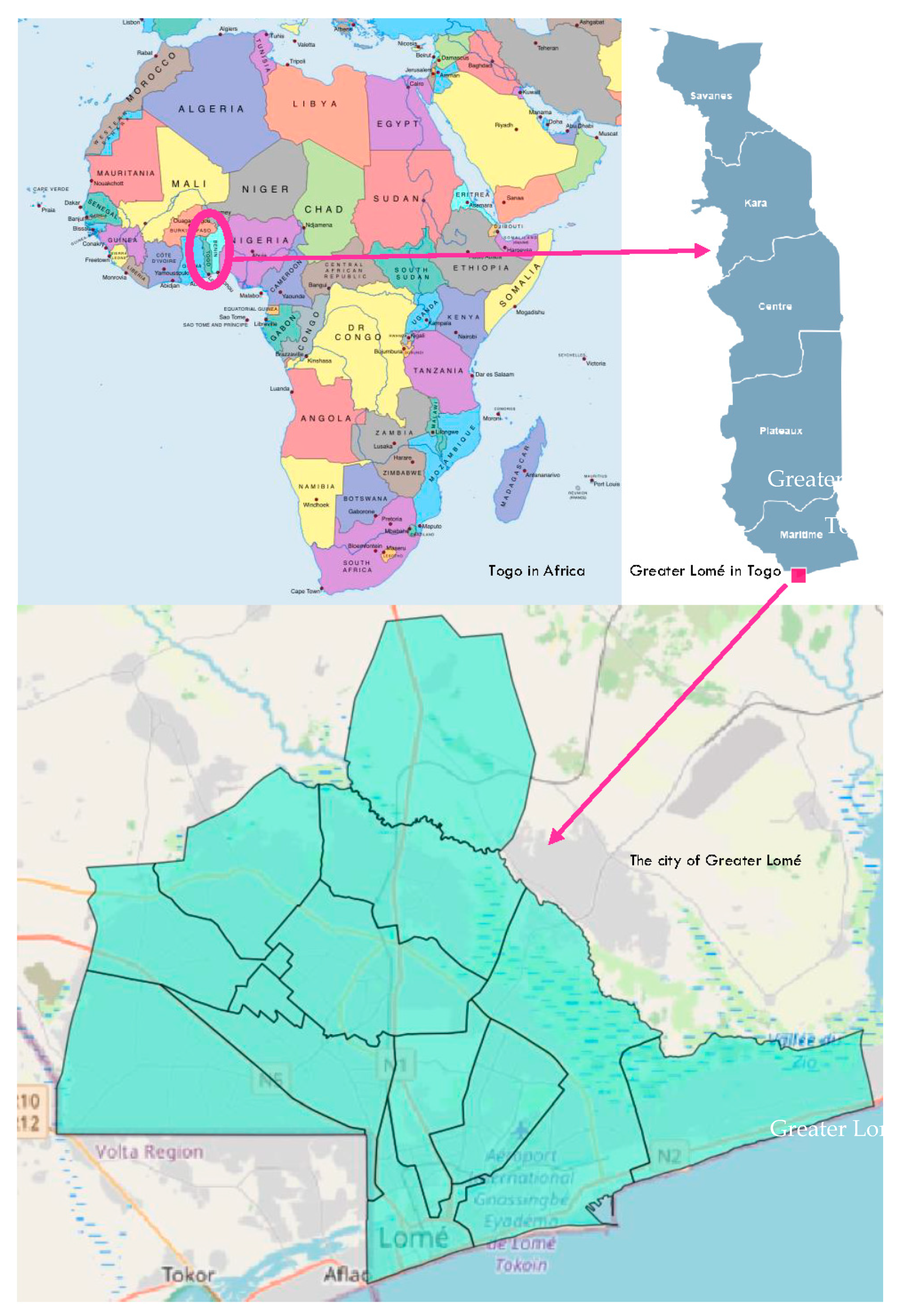

2.1. The Study Area

2.2. The Data Collection Phase

2.2.1. Interviews

- What types of tools regulate urban planning in Togo?

- What documents are you aware of that have been drawn up for planning the city of Lomé?

- Have you ever participated in the development of one or more of these documents?

- Do you know what UA is? If so, how do you define it?

- Has UA been taken into account in the planning documents you mentioned?

- In your opinion, does UA have advantages, disadvantages or both?

- If there are, what are they?

- Do you know if UA has any specific health impacts? If so, what are they?

- How long have you lived in Lomé?

- Do you know whether UA is practiced in Lomé? If so, is it legal or legitimate?

- Are you aware of the difficulties facing urban farmers in Lomé? If so, what are they?

- Do you think it would be useful or not for health to integrate UA into planning documents?

- Do you have any planning documents and GIS data or data sources for the city of Lomé to share with us, with a view to furthering our research?

2.2.2. Surveys

2.2.3. Content Analysis

2.3. The Analysis Phase

2.3.1. Analysis of Interview Data

2.3.2. Analysis of Survey Data

2.3.3. The Material

3. Results

3.1. What Experts Think Farmers Are Facing, and What Farmers Are Facing

3.1.1. What Experts Think Farmers’ Problems Are

- -

- “This type of agriculture has no land on which to express itself. These are the difficulties”.

- -

- “Those who used to practice UA no longer have space”.

- -

- “Rapid urbanization is advancing and taking land away from agriculture”.

- -

- “Landowners are occupying their sites and land to develop projects”.

- -

- “Now, for the neighbor who farms next to the empty plot, his difficulty is when the owner decides to actually settle on the land. That’s when he loses a production area”.

- -

- “The profitability of their business doesn’t allow them to compete with land speculation”.

- -

- “There are times when you don’t expect the rain, it comes, and times when you do expect the rain, it doesn’t come. It’s especially in the city that we notice this”.

- -

- “…chronic illnesses…”

- -

- “There are these illnesses that are increasing day by day, they’re having difficulties”.

- -

- “So, it’s not with drinkable water that we water the planks in Lomé”.

- -

- “…already weakened psychologically and financially added“.

- -

- “… as it’s not an organized sector”.

- -

- “The government doesn’t provide any such products, subsidies”.

- -

- “The framework is not formal”.

- -

- “Question of how much water to pour per day, diseases at the product level, there’s all that there that they don’t master”.

- -

- “The government doesn’t provide enough resources, there’s no policy to support this type of agriculture, whereas elsewhere, UA is even supported”.

3.1.2. Urban Farmers’ Reported Challenges

- Diseases caused by agricultural activity in Greater Lomé

3.1.3. UA’s Impacts on Health

3.1.4. Impact on Health

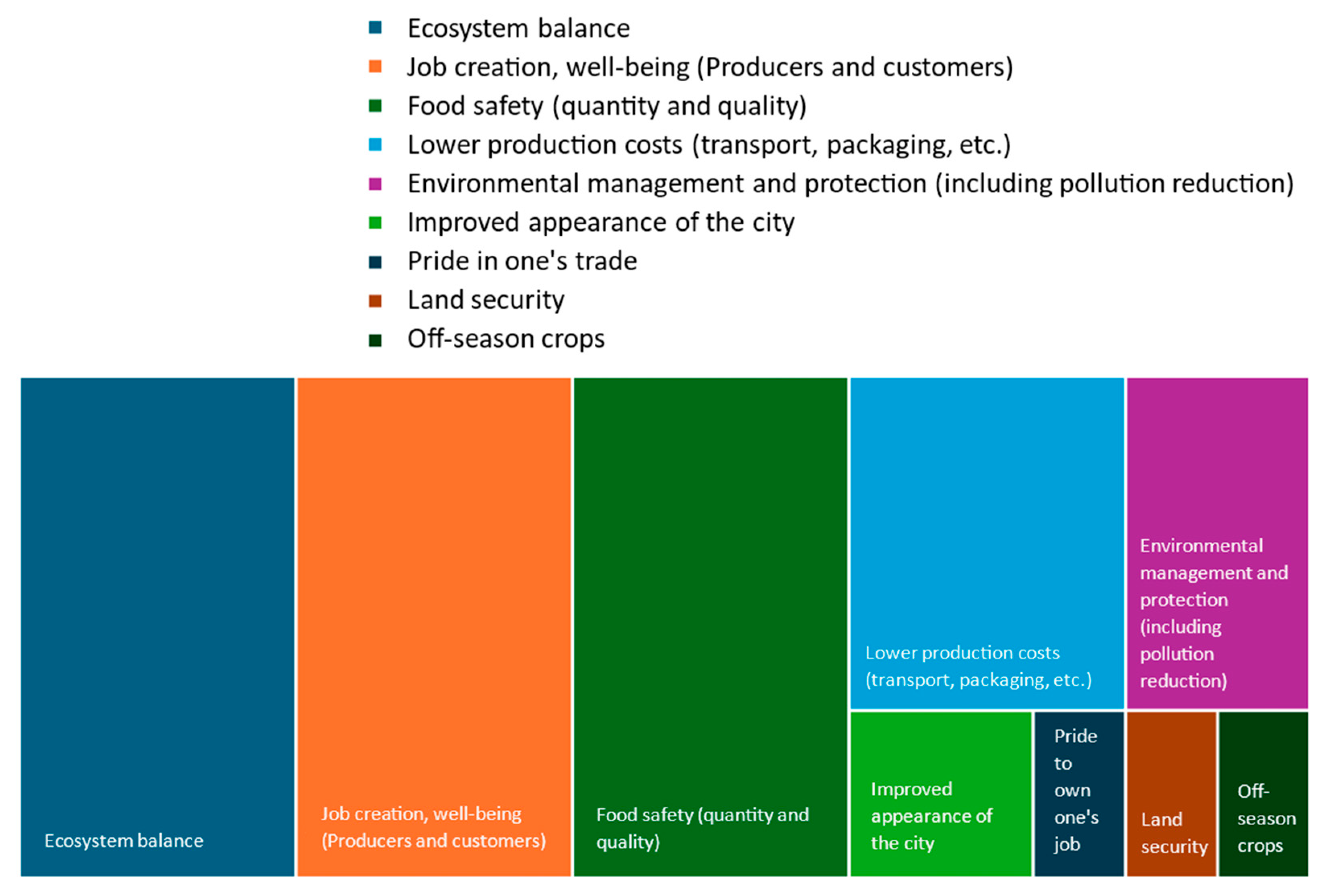

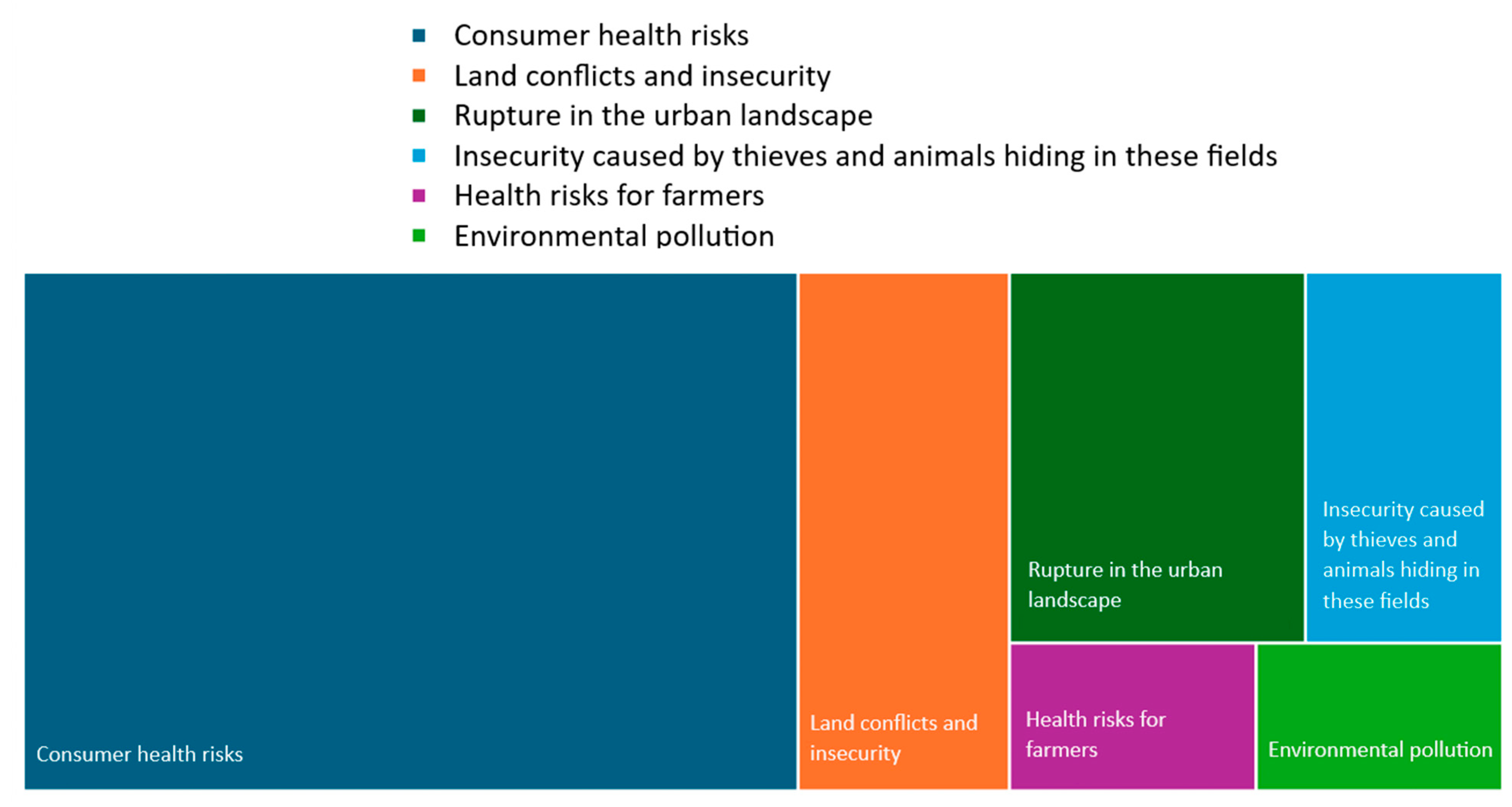

3.1.5. Advantages and Disadvantages of UA Practice

- Advantages:

- Disadvantages:

3.2. UA and Health in Policies

3.2.1. Has UA Been Considered in the Planning Documents Cited?

3.2.2. Legal Framework

3.2.3. Land Security

3.2.4. The Explicit vs. Latent Dialectic

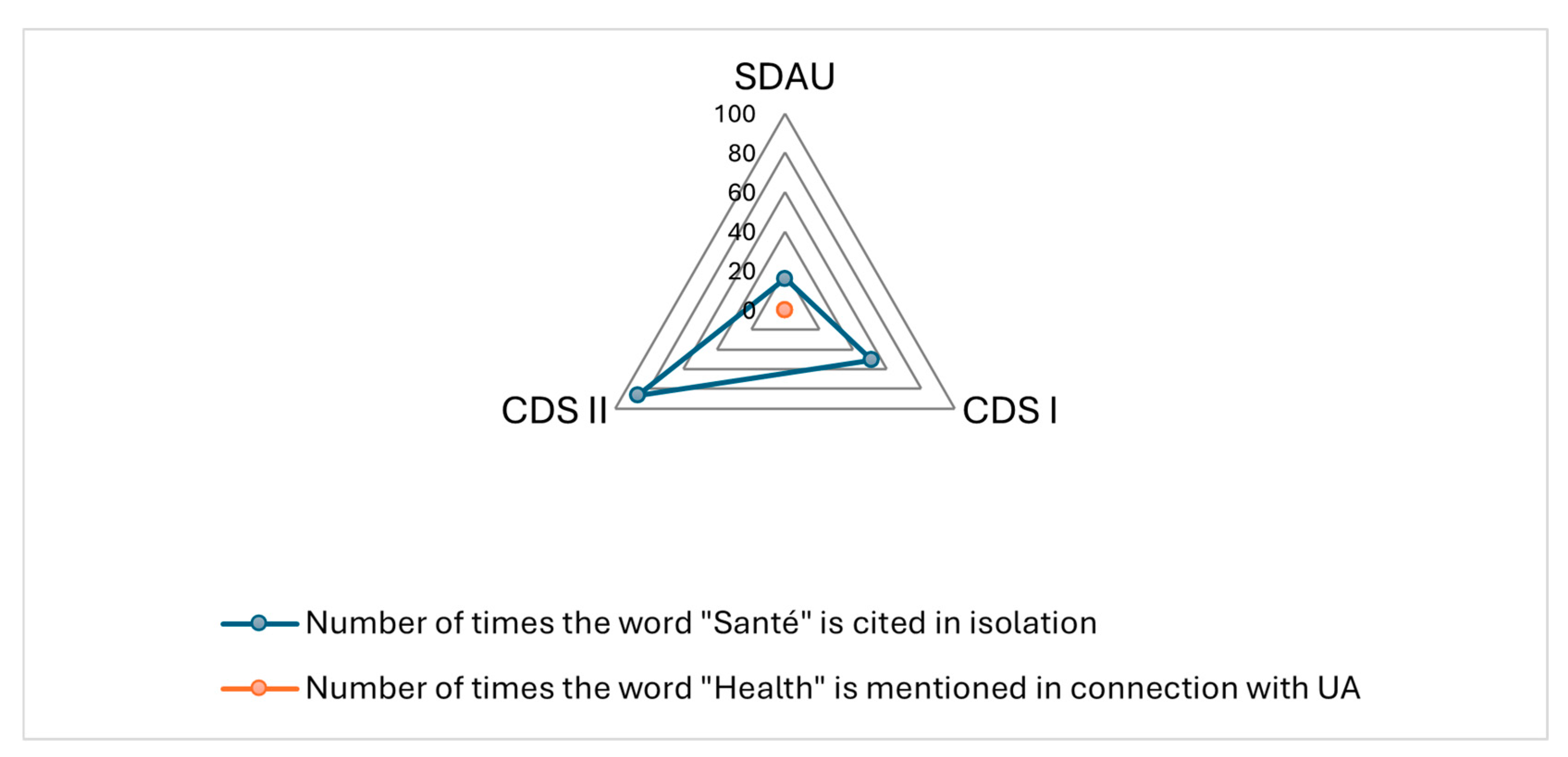

3.3. Content Analysis of the SDAU and CDS Volume I and II for Greater Lomé

3.3.1. The Planning Document “Urban Planning and Development Master Plan (SDAU) of Greater Lomé”

3.3.2. The Planning Document “Urban Development Strategy for Greater Lomé ‘CDS Greater Lomé’, Volume I”

3.3.3. The Planning Document “Urban Development Strategy for Greater Lomé ‘CDS’, Volume II”

- In the CDS II search, the occurrences of the targeted words related to agriculture can be summarized as follows. “Agricultural” is mentioned most frequently, with 35 occurrences. “Water” follows, with 26 mentions, underlining its importance in agriculture. “Agriculture” appears 19 times, indicating that it is a central topic. Agriculture-specific terms such as “culture”, “couverture”, “maraîcher”, and “pays an” are also frequently cited. “Alimentaire/agroalimentaire” (“Food/agri-food”) is mentioned 11 times.

3.3.4. Number of Times the Word “Health” Is Mentioned in Planning Documents

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison Between What Expert Perceptions of Farmers’ General Problems and Health Concerns Related to UA, and Urban Farmers’ Realities

4.1.1. Vision of UA Policies

4.1.2. Policy Exclusions

4.2. Mixed Impacts and Typology of Health Issues Raised

4.2.1. Mixed Impacts

4.2.2. Typology of Health Problems

4.3. Multivariate Analysis and Complementary Qualitative Studies

4.4. Content Analysis

4.5. Limitations

4.5.1. Number of Experts

4.5.2. Gender Imbalance

4.5.3. Using the Zoom 5.6.6 Tool

4.5.4. Prior Knowledge of the Questionnaire

4.6. Recommendations

4.6.1. Understanding and Bridging the Gap Between Politicians and Urban Farmers

4.6.2. Planning UA Sites Considering Surveys and Spatial Analyses

4.6.3. Legal Frameworks and Complete Definitions

4.6.4. Research and Planning Tools

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McClintock, N. Why Farm the City? Theorizing Urban Agriculture Through a Lens of Metabolic Rift. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. |Oxf. Acad. 2010, 3, 191–207. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/cjres/article-abstract/3/2/191/441835 (accessed on 12 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zezza, A.; Tasciotti, L. Urban Agriculture, Poverty, and Food Security: Empirical Evidence from a Sample of Developing Countries. Food Policy 2010, 35, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konou, A.A.; Kemajou Mbianda, A.F.; Munyaka, B.J.-C.; Chenal, J. Two Decades of Architects’ and Urban Planners’ Contribution to Urban Agriculture and Health Research in Africa. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konou, A.A.; Zinsou-Klassou, K.; Mwakalinga, V.M.; Munyaka, B.J.-C.; Kemajou Mbianda, A.F.; Chenal, J. Exploring the Association of Urban Agricultural Practices with Farmers’ Psychosocial Well-Being in Dar Es Salaam and Greater Lomé: A Perceptual Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E. Farm Households’ Adoption of Climate-Smart Practices in Subsistence Agriculture: Evidence from Northern Togo. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azunre, G.A.; Amponsah, O.; Peprah, C.; Takyi, S.A.; Braimah, I. A Review of the Role of Urban Agriculture in the Sustainable City Discourse. Cities 2019, 93, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graner, A.; Dzamah, A.-F.; Ahovi, K.D.; Tchangani, L.; Michel, I. Dynamique Maraîchère de La Plaine de Djagblé (Au Togo): Des Exploitations Agricoles Péri-Urbaines En Quête de Durabilité. Cah. Agric. 2023, 32, 28. Available online: https://www.cahiersagricultures.fr/fr/articles/cagri/full_html/2023/01/cagri220155/cagri220155.html (accessed on 14 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mougeot, L.J. Agropolis: The Social, Political and Environmental Dimensions of Urban Agriculture—Google Livres. Available online: https://books.google.tg/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=0_KOK1_yhI8C&oi=fnd&pg=PA51&dq=urban+farming+in+Togo&ots=B0BkGMmhIw&sig=XYKuJ5qeBI-eKZCk8c6c2nVw9vE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=urban%20farming%20in%20Togo&f=false (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- AlShrouf, A. Hydroponics, Aeroponic and Aquaponic as Compared with Conventional Farming. Am. Sci. Res. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2017, 27, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C.; Boone, C. Introduction: Land Politics in Africa–Constituting Authority over Territory, Property and Persons|Africa|Cambridge Core. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/africa/article/abs/introduction-land-politics-in-africa-constituting-authority-over-territory-property-and-persons/45EFEF04AA7C5262EC9C4369C5021416 (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Marguerat, Y. Dynamique Sociale Et Dynamique Spatiale D’une Capitale Africaine: Les Etapes De La Croissance De Lomé. Available online: https://docplayer.fr/78531985-Yves-marguerat-de-lome-avril-1986.html (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Kakaye, G. Corruption in Togo’s Land Registration and Its Impact on Real Estate Development. Doctoral Dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Berrisford, S. Why It Is Difficult to Change Urban Planning Laws in African Countries. Urban Forum 2011, 22, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatele, D.M.; Binns, T. Motivation and Marginalization in African Urban Agriculture: The Case of Lusaka, Zambia. Urban Forum 2008, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N. Urban Agriculture, Racial Capitalism, and Resistance in the Settler-Colonial City. Geogr. Compass 2018, 12, e12373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arku, G.; Mkandawire, P.; Aguda, N.; Kuuire, V. Africa’s Quest for Food Security: What is the Role of Urban Agriculture? The Institute of Development Studies and Partner Organisations. Report. 2012. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/articles/report/Africa_s_quest_for_food_security_what_is_the_role_of_urban_agriculture_/26449873?file=48098497 (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Hamilton, A.J.; Burry, K.; Mok, H.-F.; Barker, S.F.; Grove, J.R.; Williamson, V.G. Give Peas a Chance? Urban Agriculture in Developing Countries. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, S.L.G.; Pineda-Martos, R.; Timpe, A.; Pölling, B.; Bohn, K.; Külvik, M.; Delgado, C.; Pedras, C.M.G.; Paço, T.A.; Ćujić, M.; et al. Urban Agriculture as a Keystone Contribution towards Securing Sustainable and Healthy Development for Cities in the Future. Blue-Green Syst. 2019, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakpama, W.; Kanda, M.; Folega, F.; Lamboni, D.T.; Batawila, K.; Akpagana, K. Agriculture urbaine et périurbaine dans la ville de Lomé et ses banlieues. Rev. Marocaine Sci. Agron. Vét. 2021, 9, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.G.; DeLong, A.N.; Diaz, J.M. Commercial Urban Agriculture in Florida: A Qualitative Needs Assessment. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2023, 38, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemajou, A.; Konou, A.A.; Jaligot, R.; Chenal, J. Analyzing Four Decades of Literature on Urban Planning Studies in Africa (1980–2020). Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2020, 40, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, M.; Djaneye-Boundjou, G.; Wala, K.; Gnandi, K.; Batawila, K.; Sanni, A.; Akpagana, K. Application des pesticides en agriculture maraichère au Togo. VertigO-la Revue Électronique Sci. L’environ. 2013, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsel, P.; Dongus, S. Dynamics and Sustainability of Urban Agriculture: Examples from Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustain. Sci. 2010, 5, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeuw, H.D.; Veenhuizen, R.V.; Dubbeling, M. The Role of Urban Agriculture in Building Resilient Cities in Developing Countries. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Dare to Dream: Bringing Futures into Planning. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2001, 67, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayne, B.; McCordic, C.; Shilomboleni, H. Growing Out of Poverty: Does Urban Agriculture Contribute to Household Food Security in Southern African Cities? Urban Forum 2014, 25, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbemedi, Y.M. Production de la Plage dans le grand Lomé (Togo) et le Greater Accra (Ghana): Pratiques, Logiques, Enjeux. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Nanterre-Paris X, Nanterre, France, Université de Lomé (Togo), Lomé, Togo, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, M.; Wala, K.; Batawila, K.; Djaneye-Boundjou, G.; Ahanchede, A.; Akpagana, K. Periurban Market Gardening in Lomé: Agricultural Practices, Health Hazards, and Territorial Dynamics. Cah. Agric. 2009, 18, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, M.; Akpavi, S.; Wala, K.; Djaneye-Boundjou, G.; Akpagana, K. Diversité Des Espèces Cultivées et Contraintes à La Production En Agriculture Maraîchère Au Togo. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2014, 8, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kanda, M.; Badjana, H.M.; Folega, F.; Akpavi, S.; Wala, K.; Imbernon, J.; Akpagana, K. Dynamique centrifuge du maraîchage périurbain de Lomé (Togo) en réponse à la pression foncière. Cah. Agric. 2017, 26, 15001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4833-5905-2. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Turner, L.A. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2021; 100p, ISBN 9781529771282. Available online: http://digital.casalini.it/9781529771282 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Imbert, G. L’entretien semi-directif: À la frontière de la santé publique et de l’anthropologie. Rech. Soins Infirm. 2010, 102, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. Using Zoom Videoconferencing for Qualitative Data Collection: Perceptions and Experiences of Researchers and Participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919874596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, M.I. Leveraging Zoom Video-Conferencing Features in Interview Data Generation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Research and Teaching in a Pandemic World: The Challenges of Establishing Academic Identities During Times of Crisis; Cahusac de Caux, B., Pretorius, L., Macaulay, L., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 391–407. ISBN 978-981-19775-7-2. [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Kelly, M.T.; Gonzalez Montaner, G.; Yu Ko, W.F. Zoom Interviews: Benefits and Concessions. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 16094069211053522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, S. Pixilated Partnerships, Overcoming Obstacles in Qualitative Interviews via Skype: A Research Note. Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Iacono, V.; Symonds, P.; Brown, D.H.K. Skype as a Tool for Qualitative Research Interviews. Sociol. Res. Online 2016, 21, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, H.; Wakefield, K. Skype Interviewing: Reflections of Two PhD Researchers. Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Convenience Sampling|The BMJ. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f6304.full.pdf+html (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- De Bon, H.; Parrot, L.; Moustier, P. Sustainable Urban Agriculture in Developing Countries. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margenat, A.; Matamoros, V.; Díez, S.; Cañameras, N.; Comas, J.; Bayona, J.M. Occurrence and Human Health Implications of Chemical Contaminants in Vegetables Grown in Peri-Urban Agriculture. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, G.C.; Valin, H.; Sands, R.D.; Havlík, P.; Ahammad, H.; Deryng, D.; Elliott, J.; Fujimori, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Heyhoe, E.; et al. Climate Change Effects on Agriculture: Economic Responses to Biophysical Shocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3274–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofie, O.O.; Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G.; Drechsel, P. The Use of Human Waste for Peri-Urban Agriculture in Northern Ghana. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2005, 20, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foeken, D.W.J.; Owuor, S.O. Farming as a Livelihood Source for the Urban Poor of Nakuru, Kenya. Geoforum 2008, 39, 1978–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeot, L. Urban Agriculture: Definition, Presence, Potentials and Risks. In Growing Cities, Growing Food. Urban Agriculture on the Policy Agenda; International Development Research Centre (IDRC): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, P.M.; Marshall, J.M. Factors Contributing to Urban Malaria Transmission in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. J. Trop. Med. 2012, 2012, e819563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, A.; Cantoreggi, N.; Simos, J.; Duchemin, É. Impacts sur la santé des pratiques des agriculteurs urbains à Dakar (Sénégal). VertigO Rev. Électronique En Sci. L’environ. 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Urban Agriculture in the 21st Century|1|Urban Soils|Rattan Lal|. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781315154251-1/urban-agriculture-21st-century-rattan-lal (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Campbell, C.G.; Rampold, S.D. Urban Agriculture: Local Government Stakeholders’ Perspectives and Informational Needs. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2021, 36, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.; Matunga, H.; Viswanathan, L.; Patrick, L.; Walker, R.; Sandercock, L.; Moraes, D.; Frantz, J.; Thompson-Fawcett, M.; Riddle, C.; et al. Indigenous Planning: From Principles to Practice/A Revolutionary Pedagogy of/for Indigenous Planning/Settler-Indigenous Relationships as Liminal Spaces in Planning Education and Practice/Indigenist Planning/What Is the Work of Non-Indigenous People in the Service of a Decolonizing Agenda?/Supporting Indigenous Planning in the City/Film as a Catalyst for Indigenous Community Development/Being Ourselves and Seeing Ourselves in the City: Enabling the Conceptual Space for Indigenous Urban Planning/Universities Can Empower the Next Generation of Architects, Planners, and Landscape Architects in Indigenous Design and Planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2017, 18, 639–666. [Google Scholar]

- Raddad, B.S.H. Strategic Planning to Integrate Urban Agriculture in Palestinian Urban Development under Conditions of Political Instability. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 76, 127734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.; Reynolds, K. Urban Agriculture Policy Making in New York’s “New Political Spaces”: Strategizing for a Participatory and Representative System. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2014, 34, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Sarkissian, W. Housing as If People Mattered: Site Design Guidelines for the Planning of Medium-Density Family Housing; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-0-520-90879-6. [Google Scholar]

- Siegner, A.; Sowerwine, J.; Acey, C. Does Urban Agriculture Improve Food Security? Examining the Nexus of Food Access and Distribution of Urban Produced Foods in the United States: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.; Raj, S.; Ramos-Gerena, C.E. Municipal Planning Response to Urban Agriculture: Equity Is Not Quite on the Table. In Planning for Equitable Urban Agriculture in the United States: Future Directions for a New Ethic in City Building; Raja, S., Caton Campbell, M., Judelsohn, A., Born, B., Morales, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 237–250. ISBN 978-3-031-32076-7. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, C.; Oveysi, Z.; Dundar, B.; McGarvey, R. Assessment of the Effect of Urban Agriculture on Achieving a Localized Food System Centered on Chicago, IL Using Robust Optimization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2684–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasiya, S.; Khillare, P.S.; Jyethi, D.S. Health Risk Assessment of Organochlorine Pesticide Exposure through Dietary Intake of Vegetables Grown in the Periurban Sites of Delhi, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5793–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Deng, M.; Japenga, J.; Li, T.; Yang, X.; He, Z. Heavy Metal Pollution and Health Risk Assessment of Agricultural Soils in a Typical Peri-Urban Area in Southeast China. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 207, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanja, N.N.; Njenga, M.; Mutua, G.K.; Lagerkvist, C.J.; Kutto, E.; Okello, J.J. Concentrations of Heavy Metals and Pesticide Residues in Leafy Vegetables and Implications for Peri-Urban Farming in Nairobi, Kenya. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2012, 3, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nicholas, S.O.; Groot, S.; Harré, N. Understanding Urban Agriculture in Context: Environmental, Social, and Psychological Benefits of Agriculture in Singapore. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 1446–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutter, C.; Stoltz, A. Community Gardens and Urban Agriculture: Healthy Environment/Healthy Citizens. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Escobedo, F.J.; Cirella, G.T.; Zerbe, S. Edible Green Infrastructure: An Approach and Review of Provisioning Ecosystem Services and Disservices in Urban Environments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 242, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artmann, M.; Breuste, J. Urban Agriculture—More Than Food Production. In Making Green Cities: Concepts, Challenges and Practice; Breuste, J., Artmann, M., Ioja, C., Qureshi, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 75–176. ISBN 978-3-030-37716-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.Y.; Parelius, J.M.; Singh, K. Multivariate Analysis by Data Depth: Descriptive Statistics, Graphics and Inference, (with Discussion and a Rejoinder by Liu and Singh). Ann. Stat. 1999, 27, 783–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condomines, B.; Hennequin, E. Studying Sensitive Subjects: Advantages of a Mixed Approach. SSRN Electron. J. 2013. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2212034 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Ghezeljeh, A. Investigating the Intersection of Urban Agriculture and Urban Planning Concerning Urban Governance and Elements in Victoria, Canada. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerer, K.S.; Bell, M.G.; Chirisa, I.; Duvall, C.S.; Egerer, M.; Hung, P.-Y.; Lerner, A.M.; Shackleton, C.; Ward, J.D.; Yacamán Ochoa, C. Grand Challenges in Urban Agriculture: Ecological and Social Approaches to Transformative Sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 668561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Barriers to Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs-Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, U. Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Research Practice: Purposes and Advantages. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.K. Getting Farming on the Agenda: Planning, Policymaking, and Governance Practices of Urban Agriculture in New York City. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 19, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzone, C.; Woods, C. Food Urbanism: Typologies, Strategies, Case Studies; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-0356-1567-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chenal, J. The West-African City: Urban Space and Models of Urban Planning; EPFL Press: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 978-0-415-75021-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.; Korth, M.; Langer, L.; Rafferty, S.; Da Silva, N.R.; van Rooyen, C. What Are the Impacts of Urban Agriculture Programs on Food Security in Low and Middle-Income Countries? Environ. Evid. 2013, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, R.; Landry, M. L’Aide à la Décision: Nature, Instruments et Perspectives D’avenir; Presses Université Laval: Quebec, QC, Canada, 1986; ISBN 978-2-7637-7084-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Khreis, H.; Verlinghieri, E.; Mueller, N.; Rojas-Rueda, D. Participatory Quantitative Health Impact Assessment of Urban and Transport Planning in Cities: A Review and Research Needs. Environ. Int. 2017, 103, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Explicit | Latent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender of farmers used by experts during interview | The experts mainly and exclusively used male farmer pronouns in their interviews, with no female pronouns mentioned. | Unless they simply use the generic masculine default, one might conclude from their assertions that urban farmers are all men. |

| Temporality | Most participants did not express their thoughts on this element, while those who responded indicated that spaces can be temporary, permanent, or both. | According to their latent conceptualization, UA is timeless in Greater Lomé. |

| Nature of spaces | On this point, this message from one of the experts particularly caught the researchers’ attention and inspired the question: “In reality, for me, in the theme where we make urban parks, where we make urban gardens to make urban gardens, it has no life. …The advantage of having urban agriculture or a vegetable garden on the city scale is to attribute life to the thing”. | Therefore, this part of the study assesses the latent concepts expressed by experts as to whether spaces hosting UA are considered to be living/spontaneous or dead/useless. Through the exchanges, it was discovered that all of the experts considered the spaces to be living and spontaneous, with none of the participants considering them to be dead or useless. |

| Scope | Regarding the extent of urban fields, all participants indicated that spaces can be broad and interstitial. | According to their latent conceptualization, UA can have any surface size in Greater Lomé. |

| Open space or built and to be built? | All participants pointed out that the spaces are open and capable of being built on. | According to their latent conceptualization, the spaces hosting UA in Greater Lomé have no clear land status. |

| The health benefits of integrating UA into planning documents | The answers to this question were unequivocal. All of the experts agreed that UA should be systematically integrated into urban planning documents. Here is an illustration based on the first sentences of the 11 experts’ answers. | The result is that UA is essential to the urban health of Greater Lomé. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Konou, A.A.; Zinsou-Klassou, K.; De Roulet, P.T.H.; Kemajou Mbianda, A.F.; Chenal, J. Bridging the Gap: Misaligned Perceptions of Urban Agriculture and Health Between Planning and Design Experts and Urban Farmers in Greater Lomé, Togo. Land 2025, 14, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010123

Konou AA, Zinsou-Klassou K, De Roulet PTH, Kemajou Mbianda AF, Chenal J. Bridging the Gap: Misaligned Perceptions of Urban Agriculture and Health Between Planning and Design Experts and Urban Farmers in Greater Lomé, Togo. Land. 2025; 14(1):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010123

Chicago/Turabian StyleKonou, Akuto Akpedze, Kossiwa Zinsou-Klassou, Pablo Txomin Harpo De Roulet, Armel Firmin Kemajou Mbianda, and Jérôme Chenal. 2025. "Bridging the Gap: Misaligned Perceptions of Urban Agriculture and Health Between Planning and Design Experts and Urban Farmers in Greater Lomé, Togo" Land 14, no. 1: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010123

APA StyleKonou, A. A., Zinsou-Klassou, K., De Roulet, P. T. H., Kemajou Mbianda, A. F., & Chenal, J. (2025). Bridging the Gap: Misaligned Perceptions of Urban Agriculture and Health Between Planning and Design Experts and Urban Farmers in Greater Lomé, Togo. Land, 14(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14010123