Understanding the Spatial Distribution of Ecotourism in Indonesia and Its Relevance to the Protected Landscape

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Develop a map of ecotourism sites for Indonesia using the data from location-based social networks (LBSNs)

- Investigate the relationships between the distribution of ecotourism sites within the country’s protected landscapes and ecoregions

- Explore the influencing factors that contribute to the variations in ecotourism distribution across Indonesia

2. Literature Review

2.1. Roots of Ecotourism in Indonesia

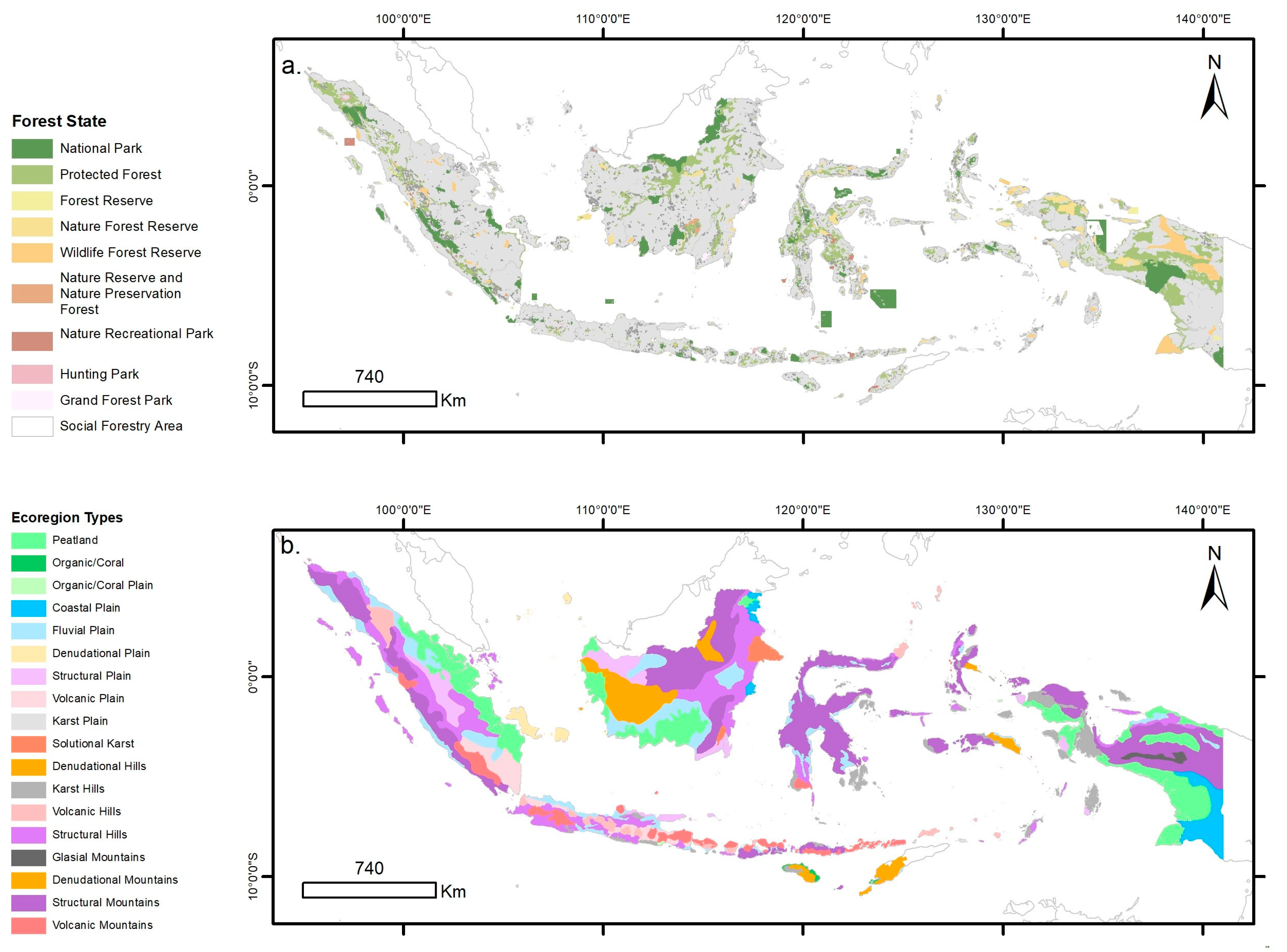

2.2. Protected Landscape in Indonesia

2.3. Location-Based Social Networks (LSBNs)

2.4. Ecoregions of Indonesia

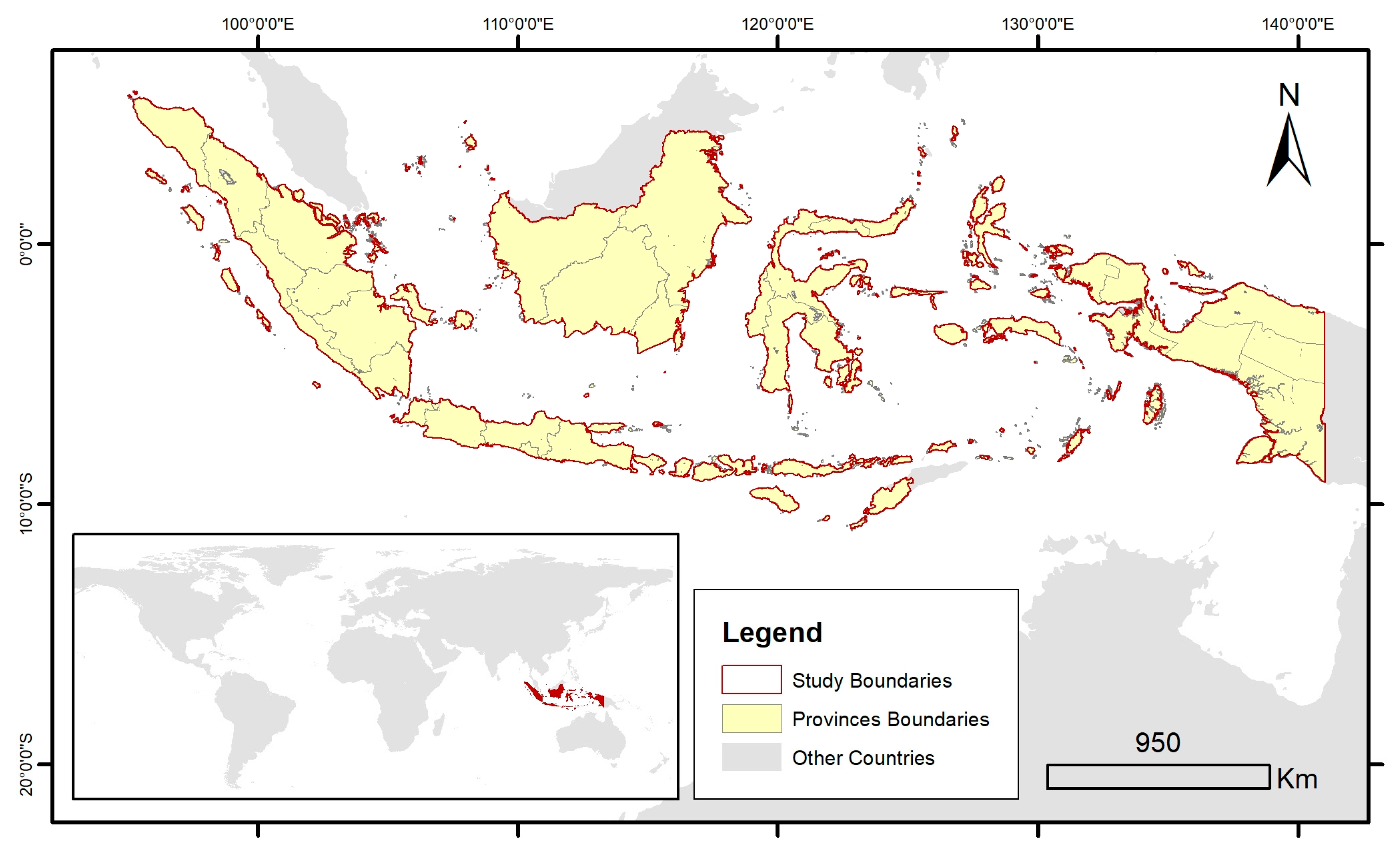

3. Study Area, Data, and Methodology

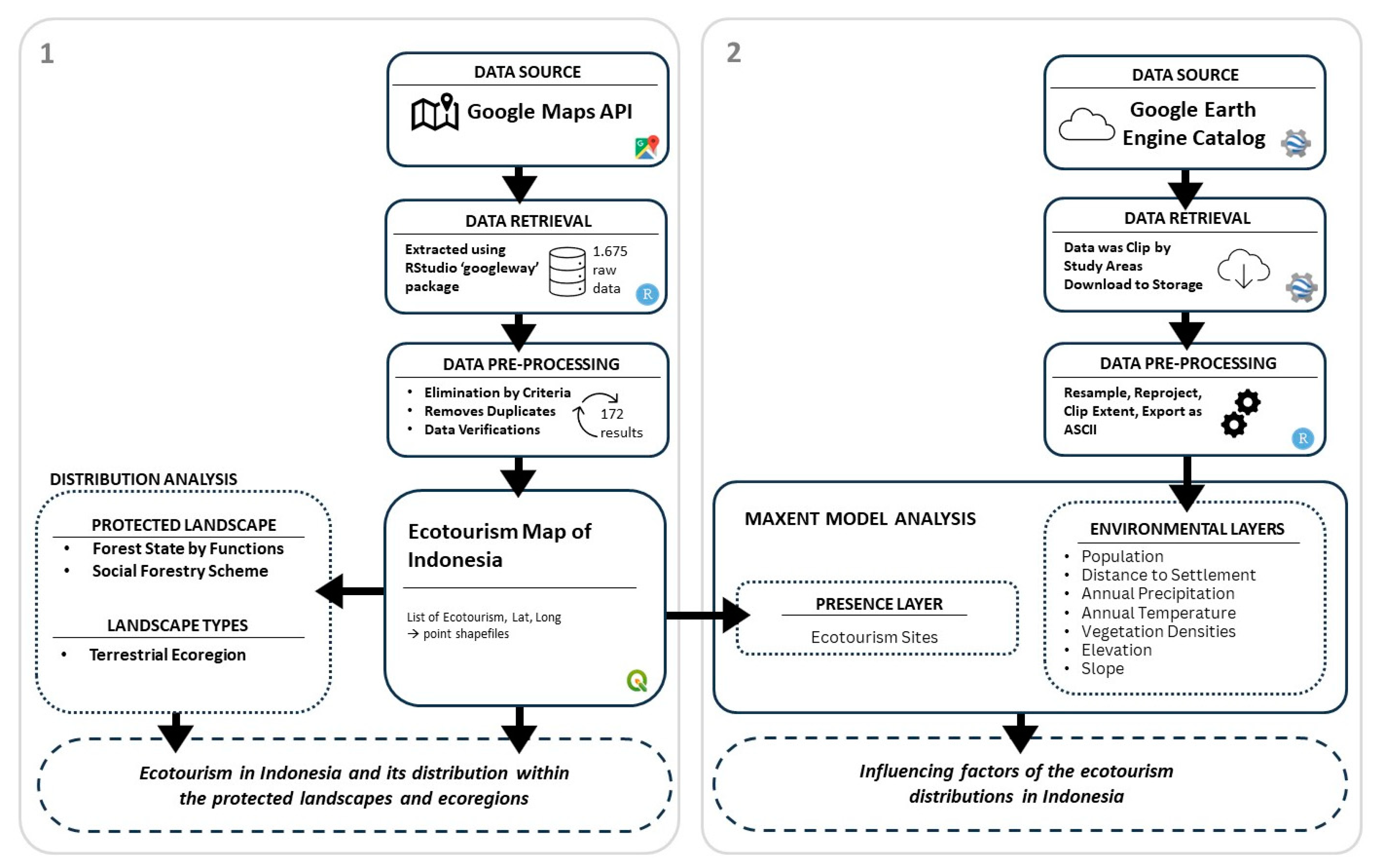

3.1. Development of Ecotourism Distribution Map Utilizing Google Places Application Programming Interface (API)

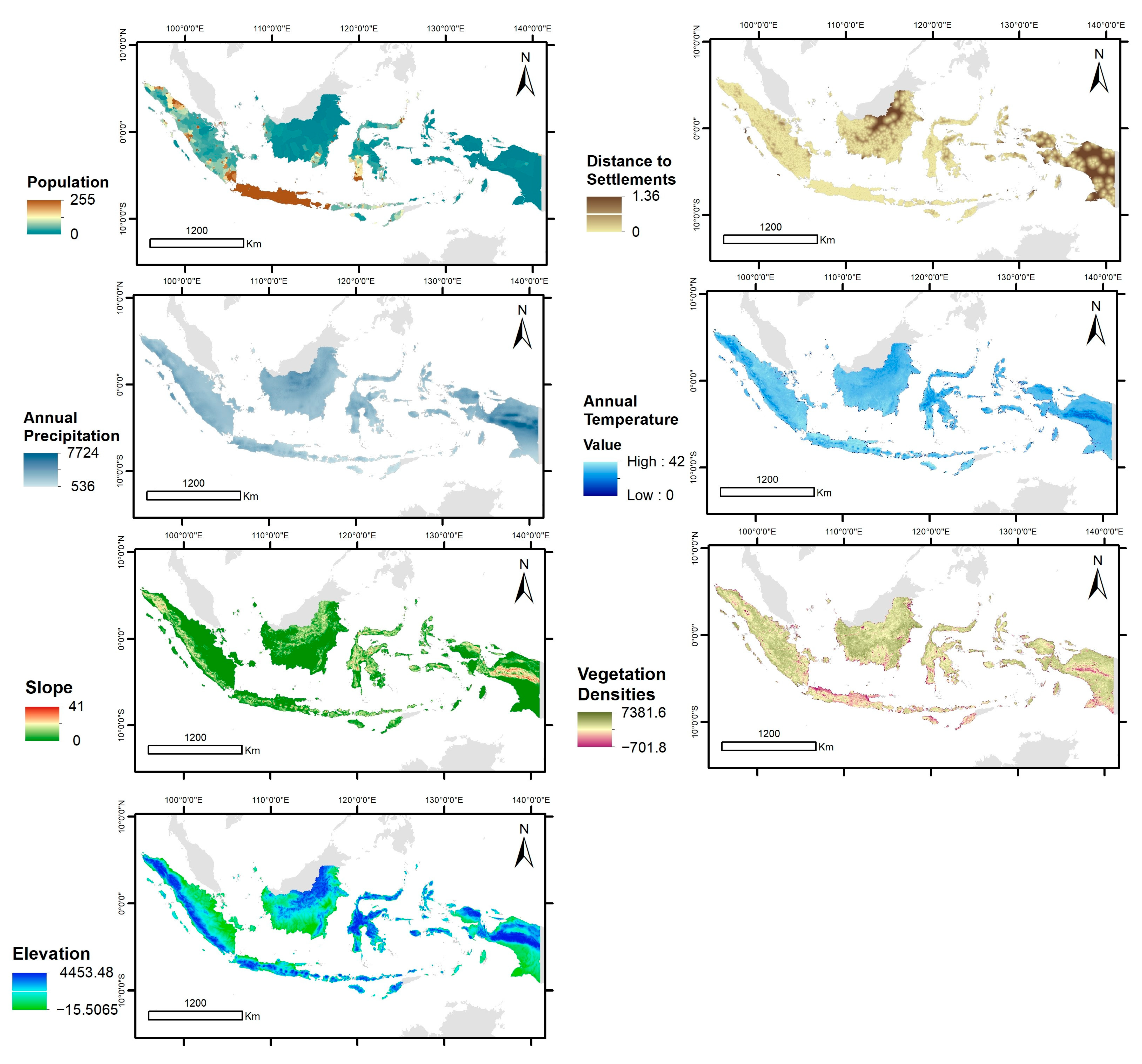

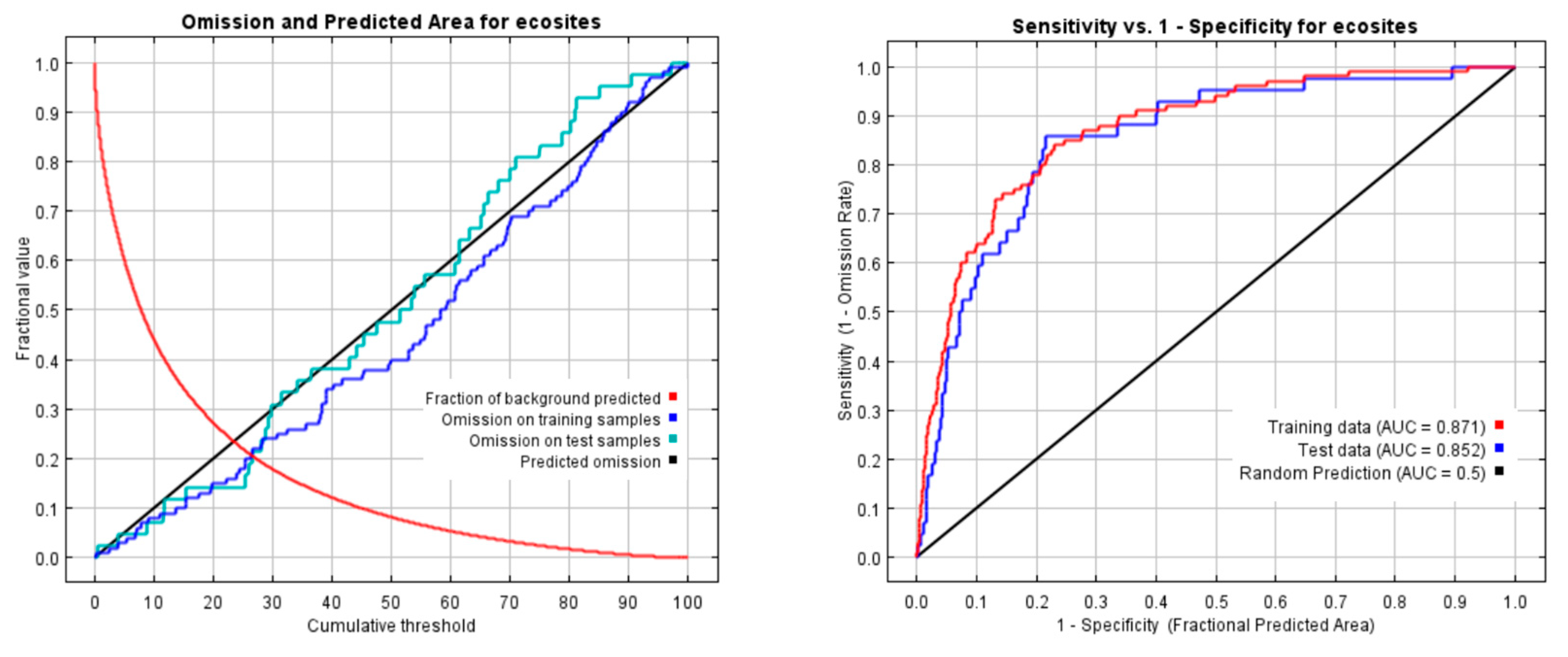

3.2. MaxEnt Model for Determining Influencing Factors

4. Results

4.1. Ecotourism in Indonesia and Its Distribution within Protected Landscapes and Ecoregions

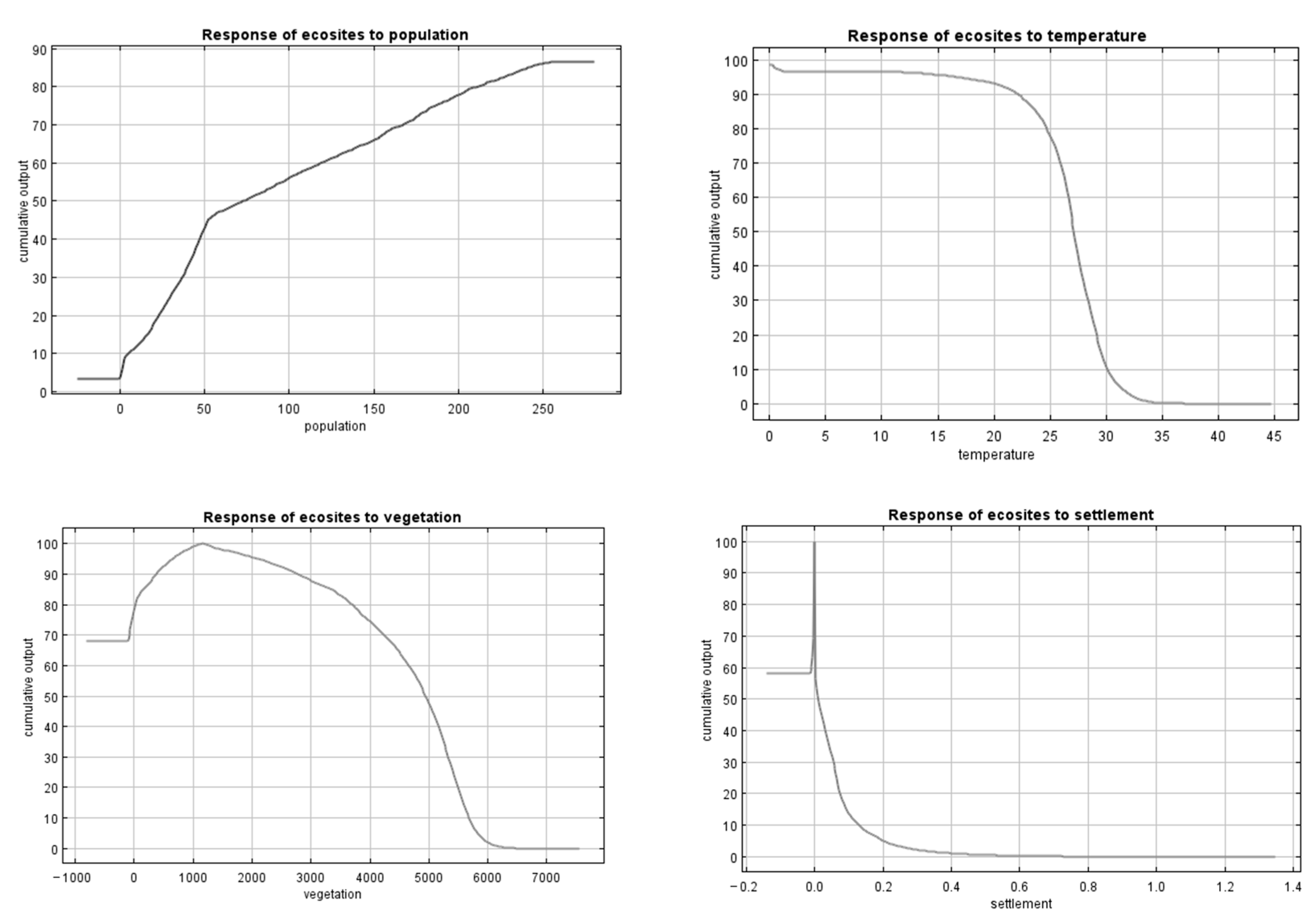

4.2. Influencing Factors of Ecotourism Distribution Based on MaxEnt Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Ecotourism in Indonesia

5.2. Relevance of This Study for the Protected Landscapes in Indonesia

5.3. Landscape Characteristics of Ecotourism in Indonesia

5.4. Human Effects and Effective Approaches

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Province | Name | Latitude | Longitude | Types * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aceh | Mount Leuser National Park | 3.519292 | 97.46344 | a |

| 2 | Taman Hutan Raya Pocut Meurah Intan | 5.443313 | 95.75949 | a | |

| 3 | Teupin Layeu | 5.871526 | 95.25749 | a | |

| 4 | Wisata Hutan Mangrove Kota Langsa | 4.521636 | 98.0162 | a | |

| 5 | Bali | Bali Botanical Garden | −8.276122 | 115.1542 | b |

| 6 | Bunut Bolong | −8.386378 | 114.8737 | b | |

| 7 | Desa Wisata Wanagiri or Tourist Information | −8.243979 | 115.1035 | a | |

| 8 | Eco Mangrove Kedonganan | −8.768786 | 115.1801 | a | |

| 9 | Tahura Ngurah Rai | −8.743976 | 115.1846 | a | |

| 10 | West Bali National Park | −8.127611 | 114.4753 | a | |

| 11 | Bangka Belitung | Pantai Batu Ampar | −1.978567 | 106.1531 | b |

| 12 | Pantai Tuing Indah | −1.658443 | 106.0214 | b | |

| 13 | Belitung Mangrove Park. | −2.771407 | 107.6191 | a | |

| 14 | Eco Wisata Gusong Bugis | −2.765375 | 107.6121 | a | |

| 15 | Hkm Juru Seberang | −2.764355 | 107.6109 | a | |

| 16 | Mangrove Munjang Kurau Barat | −2.324781 | 106.2214 | a | |

| 17 | Banten | Cagar Alam Pulau Dua/Burung | −6.017053 | 106.1941 | b |

| 18 | Negri Di Atas Awan | −6.742029 | 106.332 | a | |

| 19 | Ujung Kulon National Park | −6.784694 | 105.3751 | a | |

| 20 | Gorontalo | Bukit Peyapata | 0.5934472 | 123.1482 | b |

| 21 | Puncak Lestari | 0.7172864 | 123.02 | b | |

| 22 | Ilomata River Camp | 0.6988795 | 123.1824 | a | |

| 23 | Objek Wisata Hungayono | 0.5051694 | 123.2915 | a | |

| 24 | Jakarta | Taman Wisata Alam Mangrove, Angke Kapuk | −6.10649 | 106.7369 | a |

| 25 | Jambi | Air Terjun Telun Berasap | −1.6898849 | 101.3397 | b |

| 26 | Bukit Khayangan, Sungai Penuh, Kerinci | −2.1094083 | 101.3888 | b | |

| 27 | Berbak National Park | −1.2868651 | 104.2396 | a | |

| 28 | Bukit Duabelas National Park | −1.91667 | 102.7136 | a | |

| 29 | Lake Kaco | −2.3267771 | 101.5399 | a | |

| 30 | Jawa Barat | Ekowisata Saung Alas | −6.022639 | 106.9969 | b |

| 31 | Ekowisata Tambak Alas Blanakan | −6.263679 | 107.6647 | b | |

| 32 | Hutan Mangrove Muara Blacan | −6.024626 | 107.0235 | b | |

| 33 | Bodogol Nature Reserve (Ppka Bodogol) | −6.776267 | 106.8561 | a | |

| 34 | Ecotourism Mangrove Forest Bloom Beach | −6.024533 | 106.9967 | a | |

| 35 | Ekowisata Cisantana | −6.94909 | 108.4436 | a | |

| 36 | Kampung Wisata Ciwaluh | −6.764422 | 106.8463 | a | |

| 37 | Kawasan Taman Nasional Gunung Ciremai | −6.937826 | 108.3425 | a | |

| 38 | Taman Buru Gunung Masigit Kareumbi | −6.953246 | 107.9143 | a | |

| 39 | Jawa Tengah | Umbul Songo Kopeng | −7.403025 | 110.421 | b |

| 40 | Ekowisata Kali Talang | −7.583105 | 110.462 | a | |

| 41 | Jawa Timur | Ekowisata Mangrove Lembung | −7.165048 | 113.5737 | b |

| 42 | Labuhan Mangrove Education Park–Mitra Binaan Pertamina Hulu Energi Wmo | −6.886514 | 112.9928 | b | |

| 43 | Taman Mangrove 2 | −6.885801 | 112.9822 | b | |

| 44 | Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park | −8.021875 | 112.9524 | a | |

| 45 | Mangrove Bedul Ecotourism | −8.605017 | 114.276 | a | |

| 46 | Kalimantan Barat | Betung Kerihun National Park | 1.2015147 | 113.1886 | a |

| 47 | Sentarum Lake National Park | 0.8303082 | 112.1769 | a | |

| 48 | Kalimantan Selatan | Bukit Batu | −3.504433 | 115.0718 | b |

| 49 | Bukit Matang Kaladan | −3.525424 | 115.0094 | b | |

| 50 | Goa Liang Tapah | −1.812259 | 115.6266 | b | |

| 51 | Jeram Alam Roh Tujuh Belas | −3.419173 | 115.1415 | b | |

| 52 | Mandin Mangapan | −2.860428 | 115.5502 | b | |

| 53 | Shelter 1 Kembar Muara Kahung | −3.622409 | 115.0319 | b | |

| 54 | Taman Hutan Raya Sultan Adam | −3.519414 | 114.9501 | b | |

| 55 | Villa Pantai Batakan | −4.096644 | 114.6306 | b | |

| 56 | Taman Wisata Alam Pulau Bakut | −3.215241 | 114.5576 | a | |

| 57 | Kalimantan Tengah | Resort Mangkok–Sebangau National Park | −2.580089 | 114.0412 | b |

| 58 | Camp Leakey | −2.760856 | 111.9448 | a | |

| 59 | Hutan Lindung Sei Wain | −1.1452551 | 116.8397 | a | |

| 60 | Sebangau National Park | −2.597377 | 113.6738 | a | |

| 61 | Taman Nasional Tanjung Puting | −3.055015 | 111.9184 | a | |

| 62 | Tanjung Keluang | −2.905829 | 111.7063 | a | |

| 63 | Kalimantan Timur | Pantai Indah Teluk Kaba Kaltim Indonesia | 0.3160878 | 117.5236 | b |

| 64 | Bontang Mangrove Park | 0.1456522 | 117.4976 | a | |

| 65 | Ekowisata Mangrove Kutai Timur | 0.3877682 | 117.5636 | a | |

| 66 | Wisata Alam Prevab Tnkutai | 0.5315004 | 117.4653 | a | |

| 67 | Wisata Hutan Bambu | −1.1574416 | 116.901 | a | |

| 68 | Kalimantan Utara | Kayan Mentarang National Park | 2.871817 | 115.3786 | a |

| 69 | Lampung | Waterfall Way Tayas | −5.813779 | 105.6219 | b |

| 70 | Air Terjun Way Kalam | −5.776258 | 105.6644 | a | |

| 71 | Camp Ground Danau Lebar Suoh | −5.247633 | 104.2706 | a | |

| 72 | Nirwana Keramikan | −5.237233 | 104.2593 | a | |

| 73 | Pinus Ecopark Lampung | −4.983055 | 104.4952 | a | |

| 74 | Tahura Wan Abdul Rachman (Gunung Betung) | −5.436948 | 105.1571 | a | |

| 75 | Taman Nasional Bukit Barisan Selatan | −5.448473 | 104.3516 | a | |

| 76 | Wana Wisata Tanjung Harapan | −5.224397 | 104.7919 | a | |

| 77 | Way Kambas National Park | −4.927576 | 105.7769 | a | |

| 78 | Maluku | Pantai Nh (Nitang Hahai) | −3.5170446 | 128.2277 | b |

| 79 | Manusela National Park | −3.075128 | 129.62 | a | |

| 80 | Maluku Utara | Puncak Gunung Gamalama | 0.8091909 | 127.3333 | b |

| 81 | Sajafi Island | 0.5312862 | 128.8362 | b | |

| 82 | Tanjung Waka Desa Fatkauyon. Kabupaten Kepulauan Sula, Maluku Utara | −2.4765968 | 126.05 | b | |

| 83 | Ekowisata Mangrove Maitara Tengah | 0.728751 | 127.3782 | a | |

| 84 | Nusa Tenggara Barat | Agal Waterfall | −8.54639 | 117.0502 | b |

| 85 | Air Terjun Benang Kelambu | −8.532428 | 116.337 | b | |

| 86 | Air Terjun Jeruk Manis | −8.515453 | 116.424 | b | |

| 87 | Air Terjun Tibu Bunter | −8.536218 | 116.2599 | b | |

| 88 | Goa Raksasa Tanjung Ringgit | −8.86012 | 116.5933 | b | |

| 89 | Kawasan Ekowisata Mangrove & Pengamatan Burung Gili Meno | −8.351133 | 116.0566 | b | |

| 90 | Camping Ground Ekowisata Gawar Gong | −8.506452 | 116.5341 | a | |

| 91 | Mount Tambora National Park | −8.272661 | 117.982 | a | |

| 92 | Taman Wisata Alam Gunung Tunak | −8.911051 | 116.381 | a | |

| 93 | Tanjung Ringgit | −8.861667 | 116.5944 | a | |

| 94 | Nusa Tenggara Timur | Danau Ranamese (Ranamese Lake) | −8.639167 | 120.5611 | b |

| 95 | Golo Depet | −8.65601 | 120.5609 | b | |

| 96 | Loh Buaya Komodo National Park | −8.653757 | 119.7169 | b | |

| 97 | Loh Liang–Komodo National Park | −8.569461 | 119.5007 | b | |

| 98 | Mulut Seribu Beach | −10.561694 | 123.3726 | b | |

| 99 | Niagara Murukeba | −8.747879 | 121.8252 | b | |

| 100 | Pantai Litianak | −10.755165 | 122.8999 | b | |

| 101 | Pantai Onanbalu | −10.224845 | 123.3515 | b | |

| 102 | Pantai Uiasa | −10.147299 | 123.4648 | b | |

| 103 | Taman Wisata Alam Menipo | −10.148512 | 124.1491 | b | |

| 104 | Taman Wisata Alam Ruteng | −8.641901 | 120.5592 | b | |

| 105 | Wolokoro Ecotourism | −8.81706 | 120.9341 | b | |

| 106 | Kelimutu National Park | −8.741548 | 121.7936 | a | |

| 107 | Komodo National Park | −8.527716 | 119.4833 | a | |

| 108 | Papua | Pantai Wagi | −3.3808233 | 135.1236 | b |

| 109 | Papua | Ekowisata Hutan Mangrove Pomako | −4.7977436 | 136.7697 | a |

| 110 | Papua Barat | Piaynemo Raja Ampat | −0.5642076 | 130.2708 | b |

| 111 | Sauwandarek Village | −0.5903592 | 130.6023 | b | |

| 112 | Papua Pegunungan | Lorentz National Park | −4.6297633 | 137.9727 | b |

| 113 | Riau | Air Terjun Tujuh Tingkat | −0.6174255 | 101.3224 | b |

| 114 | Bukit Tigapuluh National Park | −0.922584 | 102.4685 | a | |

| 115 | Suaka Margasatwa Rimbang Baling | −0.1835694 | 100.9355 | a | |

| 116 | Wisata Batu Belah Desa Batu Sanggan | −0.1953949 | 101.0406 | a | |

| 117 | Wisata Pulau Tilan | 1.5412444 | 101.0913 | a | |

| 118 | Sulawesi Selatan | Air Terjun Sarambu Ala | −2.704501 | 120.1323 | b |

| 119 | Bukit Bossolo | −5.501162 | 119.8437 | b | |

| 120 | Ide Beach | −2.51529 | 121.3423 | b | |

| 121 | Karawa Waterfall | −3.477889 | 119.5488 | b | |

| 122 | Balai Taman Nasional Bantimurung Bulusaraung | −4.801184 | 119.8235 | a | |

| 123 | Wisata Leang Lonrong | −4.861953 | 119.6366 | a | |

| 124 | Sulawesi Tengah | Lore Lindu National Park | −1.47495 | 120.1889 | a |

| 125 | Sulawesi Tenggara | Air Panas Wawolesea | −3.696262 | 122.3033 | b |

| 126 | Taman Nasional Rawa Aopa Watumohai | −4.438332 | 121.8733 | a | |

| 127 | Wakatobi National Park | −5.563474 | 123.9304 | a | |

| 128 | Sulawesi Utara | Obyek Wisata Pantai Batu Pinagut | 0.9202904 | 123.2694 | b |

| 129 | Pantai Lakban Ratatotok | 0.8492183 | 124.7087 | b | |

| 130 | Tanjung Kamala Watuline | 1.7277707 | 125.0225 | b | |

| 131 | Bunaken National Marine Park | 1.675843 | 124.7556 | a | |

| 132 | Ekowisata Mangrove Desa Bahoi | 1.7180899 | 125.02 | a | |

| 133 | Kek Pariwisata Likupang | 1.6801855 | 125.1575 | a | |

| 134 | Mangrove Park Bahowo | 1.5809465 | 124.8194 | a | |

| 135 | Tangkoko Batuangus Nature Reserve | 1.5082463 | 125.1882 | a | |

| 136 | Sumatera Barat | Aia Tigo Raso Nagari Koto Malintang Agam | −0.3028417 | 100.1271 | b |

| 137 | Air Terjun Langkuik | −0.4248701 | 100.28 | b | |

| 138 | Air Terjun Lubuak Bulan | −0.03658 | 100.60104 | b | |

| 139 | Air Terjun Lubuak Rantiang | −0.797728 | 100.37684 | b | |

| 140 | Air Terjun Lubuk Hitam | −1.0519767 | 100.4311 | b | |

| 141 | Air Terjun Proklamator 2022 | −0.482063 | 100.34348 | b | |

| 142 | Air Terjun Sarasah | −0.9328629 | 100.49915 | b | |

| 143 | Ngalau Loguang | −0.401077 | 100.4228 | b | |

| 144 | Pemandian Lubuk Lukum | −0.7876688 | 100.40595 | b | |

| 145 | Sarasah Bunta Waterfall | −0.1082169 | 100.6754 | b | |

| 146 | Sarasah Tanggo | −0.1372626 | 100.64031 | b | |

| 147 | Ujung Kapuri Beach | −1.1244429 | 100.36491 | b | |

| 148 | Harau Valley Waterfall | −0.10004 | 100.6659 | a | |

| 149 | Kerinci Seblat National Park | −1.7042204 | 101.26899 | a | |

| 150 | Lawang Adventure Park | −0.2807779 | 100.2416 | a | |

| 151 | Lembah Anai Waterfall | −0.483611 | 100.3384 | a | |

| 152 | Objek Wisata Taman Suaka Alam Rimbo Panti | 0.3463983 | 100.06914 | a | |

| 153 | Panorama Aka Barayun | −0.1009714 | 100.66691 | a | |

| 154 | Siberut Island National Park | −1.3174892 | 98.88916 | a | |

| 155 | Sumatera Selatan | Bukit Cogong | −3.151267 | 102.9072 | a |

| 156 | Bukit Sulap | −3.285871 | 102.8569 | a | |

| 157 | Ekowisata Hutan Lindung Bukit Botak | −3.155926 | 102.926 | a | |

| 158 | Ekowisata Kibuk | −4.045187 | 103.1414 | a | |

| 159 | Puntikayu Amusement Palembang | −2.943726 | 104.7283 | a | |

| 160 | Taman Nasional Sembilang | −2.035627 | 104.6593 | a | |

| 161 | Sumatera Utara | Air Terjun Sikulikap | 3.2454292 | 98.53399 | b |

| 162 | Air Terjun Sipitu-Pitu | 1.686052 | 98.94605 | b | |

| 163 | Bat Cave Bukit Lawang | 3.535454 | 98.11727 | b | |

| 164 | Tangkahan | 3.695156 | 98.07107 | a | |

| 165 | Toba Caldera Resort | 2.6075849 | 98.94648 | a | |

| 166 | Yogyakarta | Becici Peak | −7.902036 | 110.4375 | b |

| 167 | Hutan Pinus Asri | −7.920921 | 110.4356 | b | |

| 168 | Hutan Pinus Pengger | −7.871204 | 110.4595 | b | |

| 169 | Mojo Gumelem Hill | −7.957364 | 110.4334 | b | |

| 170 | Hutan Pinus Mangunan | −7.925816 | 110.4318 | a | |

| 171 | Rph Mangunan | −7.930329 | 110.4297 | a | |

| 172 | Wisata Air Terjun Sri Gethuk | −7.943178 | 110.4892 | a |

Appendix B

| No | Name of Ecoregion Complex | Number of Ecotourism Sites |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marine Ecoregion | 11 |

| 2 | Ecoregion Complex of Structural Hills of Bukit Rimbang–Bukit Baling Dangku–Bukit Tigapuluh | 11 |

| 3 | Ecoregion Complex of Kerinci Seblat Structural Mountains–Bukit Barisan Selatan | 11 |

| 4 | Ecoregion Complex of Lore Lindu Structural Mountains–Bogani Nani Wartabone | 10 |

| 5 | Ecoregion Complex of Volcanic Mountains Bali–Lombok | 8 |

| 6 | Ecoregion Complex of Meratus Structural Mountains | 7 |

| 7 | Ecoregion Complex of Wonosari Structural Hills–Trenggalek | 7 |

| 8 | Ecoregion Complex of Flores Volcanic Mountains | 7 |

| 9 | Ecoregion Complex of Benakat Semangus Volcanic Plain–Way Kambas | 6 |

| 10 | Ecoregion Complex of Cilegon Indramayu Fluvial Plain–Pekalongan | 6 |

| 11 | Ecoregion Complex of North South Maninjau Volcanic Mountains–Mount Sado | 6 |

| 12 | Ecoregion Complex of Meratus Structural Hills | 5 |

| 13 | Ecoregion Complex of Denudational Plain Kep. Bangka Belitung | 5 |

| 14 | Ecoregion Complex of Peat Plains of S. Katingan–S. Sebangau | 4 |

| 15 | Ecoregion Complex of Volcanic Mountains G. Halimun–G. Salak–M. Sawal | 4 |

| 16 | Ecoregion Complex of Manembo Nembo Volcanic Hills–Duasudara–Tangkoko | 3 |

| 17 | Ecoregion Complex of Janthoi Structural Mountains–Mount Leuser | 3 |

| 18 | Ecoregion Complex of Peat Plains of the East Coast of Sumatra | 3 |

| 19 | Ecoregion Complex of Gumay Tebing Tinggi Volcanic Mountains–Gunung Raya | 3 |

| 20 | Ecoregion Complex of Flores Structural Hills | 2 |

| 21 | Ecoregion Complex of Sibolangit–Dolok–Sipirok Volcanic Hills | 2 |

| 22 | Ecoregion Complex of Volcanic Hills of Mount Slamet–Merapi | 2 |

| 23 | Ecoregion Complex of Bangkalan Structural Plain–Sumenep | 2 |

| 24 | Ecoregion Complex of Structural Hills of Bali–Lombok | 2 |

| 25 | Ecoregion Complex of Mahakam Structural Mountains | 2 |

| 26 | Ecoregion Complex of Structural Hills of the West Coast of Sumatra | 2 |

| 27 | Ecoregion Complex of Kuala Kuayan Fluvial Plain–Kasongan | 2 |

| 28 | Ecoregion Complex of G.Ceremai Volcanic Hills | 2 |

| 29 | Ecoregion Complex of Volcanic Mountains of North Maluku | 2 |

| 30 | Ecoregion Complex of Organic/South Central Timor Coral | 2 |

| 31 | Ecoregion Complex of Barumun Structural Mountains–Malampah Alahan Panjang | 2 |

| 32 | Ecoregion Complex of P. Waigeo Structural Mountains | 1 |

| 33 | Ecoregion Complex of Volcanic Hills of Bali–Lombok | 1 |

| 34 | Ecoregion Complex of Denudational Mountains P. Seram | 1 |

| 35 | Ecoregion Complex of Kuis River Peat Plain–Bapai River. | 1 |

| 36 | Ecoregion Complex of Organic/Coral Plains P. Misol–P. Kofiau | 1 |

| 37 | Ecoregion Complex of Organic/Coral Bali–Lombok | 1 |

| 38 | Ecoregion Complex of Jayawijaya Route Structural Hills. | 1 |

| 39 | Ecoregion Complex of Malino Volcanic Mountains | 1 |

| 40 | Ecoregion Complex of Ujung Kulon Structural Hills–Cikepuh- Leuweung Sancang | 1 |

| 41 | Ecoregion Complex of Idirayeuk Fluvial Plain–Binjai–Sutan Syarif Qasim | 1 |

| 42 | Ecoregion Complex of Denudational Mountains of South-Central Timor | 1 |

| 43 | Ecoregion Complex of Sumbawa Volcanic Mountains | 1 |

| 44 | Ecoregion Complex of Cut Nyak Dhien- Lampahan- Langkat Structural Hills | 1 |

| 45 | Ecoregion Complex of Denudational Hills of North Maluku | 1 |

| 46 | Ecoregion Complex of G. Gogugu–S. Ranoyapo Structural Hills | 1 |

| 47 | Ecoregion Complex of Fluvial Plains of Bali–Lombok | 1 |

| 48 | Ecoregion Complex of Structural Hills of North Maluku | 1 |

| 49 | Ecoregion Complex of Bantimurung Karst Hills–Bulusaraung | 1 |

| 50 | Ecoregion Complex of Central Structural Mountains of Papua | 1 |

| 51 | Ecoregion Complex of Siranggas Structural Hills–Batang Girls | 1 |

| 52 | Ecoregion Complex of S. Darau Structural Plain | 1 |

| 53 | Ecoregion Complex of Sentarum Fluvial Plain | 1 |

| 54 | Ecoregion Complex of Tesso Nilo Structural Plain–Bukit Duabelas | 1 |

| 55 | Ecoregion Complex of P. Seram Structural Mountains | 1 |

| 56 | Ecoregion Complex of Bromo Volcanic Mountains–Yang Plateau–Baluran | 1 |

| 57 | Ecoregion Complex of Alas Purwo Fluvial Plain | 1 |

| 58 | Ecoregion Complex of Cani Sirenreng Structural Hills | 1 |

| 59 | Ecoregion Complex of Denudational Hills of South-Central Timor | 1 |

| Grand Total | 172 |

References

- Buckley, R. (Ed.) Environmental Impacts of Ecotourism; Ecotourism Book Series; CABI Pub: Wallingford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-85199-810-7. [Google Scholar]

- Boo, E. Ecotourism: The Potentials and Pitfalls: Country Case Studies; World Wildlife Fund: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lasso, A.H.; Dahles, H. A Community Perspective on Local Ecotourism Development: Lessons from Komodo National Park. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 634–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatma Indra Jaya, P.; Izudin, A.; Aditya, R. The Role of Ecotourism in Developing Local Communities in Indonesia. J. Ecotourism 2022, 23, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butarbutar, R.R.; Soemarno, S. Community Empowerment Efforts in Sustainable Ecotourism Management in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Indones. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kia, Z. Ecotourism in Indonesia: Local Community Involvement and The Affecting Factors. J. Gov. Public Policy 2021, 8, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A. Ecotourism, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-415-82964-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wearing, S.; Neil, J. Ecotourism: Impacts, Potentials and Possibilities? 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-7506-6249-9. [Google Scholar]

- Purnomo, M.; Maryudi, A.; Dedy Andriatmoko, N.; Muhamad Jayadi, E.; Faust, H. The Cost of Leisure: The Political Ecology of the Commercialization of Indonesia’s Protected Areas. Environ. Sociol. 2022, 8, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisriany, A.; Furuya, K. Ecotourism Policy Research Trends in Indonesia, Japan, and Australia. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. J. Trop. For. Manag. 2020, 26, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masser, I. All Shapes and Sizes: The First Generation of National Spatial Data Infrastructures. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1999, 13, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretz, K.J. Indonesia’s One Map Policy: A Critical Look at the Social Implications of a’Mess’. Senior Thesis, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/134/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Fisher, R.P.; Myers, B.A. Free and Simple GIS as Appropriate for Health Mapping in a Low Resource Setting: A Case Study in Eastern Indonesia. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanthi, N.S.; Purwanto, T.H. Application of OpenStreetMap (OSM) to Support the Mapping Village in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 47, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, T.Y.D.; Sekimoto, Y.; Shibasaki, R. Toward the Evolution of National Spatial Data Infrastructure Development in Indonesia. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, M.; Yamashita, S.; Adams, K.M.; Borchers, H.; Bennett, J.; Richter, L. (Eds.) Tourism in Southeast Asia: Challenges and New Directions; Nias Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009; ISBN 978-87-7694-033-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, J. New Directions in Indonesian Ecotourism. In Tourism in Southeast Asia: Challenges and New Directions; Nias Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009; pp. 254–269. [Google Scholar]

- Government Regulation No. 23 of 2021 on Forestry Implementation. Available online: http://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/161853/pp-no-23-tahun-2021 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Sahide, M.A.K.; Fisher, M.R.; Erbaugh, J.T.; Intarini, D.; Dharmiasih, W.; Makmur, M.; Faturachmat, F.; Verheijen, B.; Maryudi, A. The Boom of Social Forestry Policy and the Bust of Social Forests in Indonesia: Developing and Applying an Access-Exclusion Framework to Assess Policy Outcomes. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 120, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbaugh, J.T. Responsibilization and Social Forestry in Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 109, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamstead, Z.A.; Fisher, D.; Ilieva, R.T.; Wood, S.A.; McPhearson, T.; Kremer, P. Geolocated Social Media as a Rapid Indicator of Park Visitation and Equitable Park Access. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 72, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, N.; Manovich, L. Zooming into an Instagram City: Reading the Local through Social Media. First Monday 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel, A. Visualizing the Perceived Environment Using Crowdsourced Photo Geodata. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 142, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, P.; Serrano-Estrada, L.; Nolasco-Cirugeda, A. Social Media Data: Challenges, Opportunities and Limitations in Urban Studies. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 74, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Forestry and Environment Indonesia. KLHK. Available online: https://Sigap.Menlhk.Go.Id/KLHK (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Ministy of Environment. Description of the Ecoregion Map on the Island/Archipelago; Deputy for Environmental Management, Ministy of Environment: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013; ISBN 978-602-8773-09-6.

- Andréfouët, S.; Paul, M.; Farhan, A.R. Indonesia’s 13558 Islands: A New Census from Space and a First Step towards a One Map for Small Islands Policy. Mar. Policy 2022, 135, 104848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudik, M.; Schapire, R.E. [Internet] Maxent Software for Modeling Species Niches and Distributions (Version 3.4.1). Available online: http://biodiversityinformatics.amnh.org/open_source/maxent/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Kim, G.; Kang, W.; Park, C.R.; Lee, D. Factors of Spatial Distribution of Korean Village Groves and Relevance to Landscape Conservation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 176, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, E.S.; Örücü, Ö.K. MaxEnt Modelling of the Potential Distribution Areas of Cultural Ecosystem Services Using Social Media Data and GIS. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 2655–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Kuo, C.-L.; Feng, C.-C.; Huang, W.; Fan, H.; Zipf, A. Coupling Maximum Entropy Modeling with Geotagged Social Media Data to Determine the Geographic Distribution of Tourists. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 32, 1699–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaresi, M.; Ehrlich, D.; Ferri, S.; Florczyk, A.; Carneiro, F.S.M.; Halkia, S.; Julea, A.M.; Kemper, T.; Soille, P.; Syrris, V. Operating Procedure for the Production of the Global Human Settlement Layer from Landsat Data of the Epochs 1975, 1990, 2000, and 2014. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC97705 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Population Count, v4.11: Gridded Population of the World (GPW), v4|SEDAC. Available online: https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/gpw-v4-population-count-rev11 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Didan, K. MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250m SIN Grid V061. 2021, Distributed by NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD13Q1.061 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- NASADEM Merged DEM Global 1 Arc Second V001. Available online: https://cmr.earthdata.nasa.gov/search/concepts/C1546314043-LPDAAC_ECS.html (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- OpenLandMap Long-Term Land Surface Temperature Monthly Day-Night Difference|Earth Engine Data Catalog. Available online: https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/OpenLandMap_CLM_CLM_LST_MOD11A2-DAYNIGHT_M_v01 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Brocca, L.; Filippucci, P.; Hahn, S.; Ciabatta, L.; Massari, C.; Camici, S.; Schüller, L.; Bojkov, B.; Wagner, W. SM2RAIN–ASCAT (2007–2018): Global Daily Satellite Rainfall Data from ASCAT Soil Moisture Observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1583–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M. Modeling of Species Distributions with Maxent: New Extensions and a Comprehensive Evaluation. Ecography 2008, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, W.P.; Sekartjakrarini, S. Disentangling Ecotourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundmark, L.J.T.; Fredman, P.; Sandell, K. National Parks and Protected Areas and the Role for Employment in Tourism and Forest Sectors: A Swedish Case. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, art19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açıksöz, S.; Cetinkaya, G.C.; Uzun, O.; Erduran Nemutlu, F.; Ilke, E.F. Linkages among Ecotourism, Landscape and Natural Resource Management, and Livelihood Diversification in the Region of Suğla Lake, Turkey. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A. Ecotourism Programme Planning; CABI Pub: Wallingford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-85199-610-3. [Google Scholar]

| Aspects | Explanatory Variables | Description | Google Earth Engine Data Catalog Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Pressures | Settlement | Distance to Settlements | GHSL: Global Human Settlement Layers, Built-Up Grid 1975-1990-2000-2015 (P2016) [32] |

| Population | Population counts per grid | GPWv411: Population Count (Gridded Population of the World Version 4.11) [33] | |

| Landscape Characters | Vegetation | Enhanced vegetation index (EVI) | MOD13Q1.061 Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day Global 250 m [34] |

| Elevation | Elevation | National Aeronautics and Space Administration Digital Elevation Model (NASADEM): NASADEM Digital Elevation 30 m4 [35] | |

| Slope | Slope | ||

| Climate | Temperature | Annual Temperature | OpenLandMap Long-term Land Surface Temperature Monthly Day-Night Difference [36] |

| Precipitation | Annual Precipitation | OpenLandMap Precipitation Monthly [37] |

| Islands | Province | Sites | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sumatra | West Sumatra | 19 | 58 |

| Lampung | 9 | ||

| South Sumatra | 6 | ||

| Bangka Belitung | 6 | ||

| North Sumatra | 5 | ||

| Jambi | 5 | ||

| Riau | 5 | ||

| Aceh | 4 | ||

| Bali and Nusa Tenggara | East Nusa Tenggara | 14 | 27 |

| West Nusa Tenggara | 10 | ||

| Bali | 6 | ||

| Java | West Java | 9 | 26 |

| Yogyakarta | 7 | ||

| East Java | 5 | ||

| Banten | 3 | ||

| Central Java | 2 | ||

| Jakarta | 1 | ||

| Kalimantan | South Kalimantan | 9 | 22 |

| Central Kalimantan | 6 | ||

| East Kalimantan | 5 | ||

| West Kalimantan | 2 | ||

| North Kalimantan | 1 | ||

| Sulawesi | South Sulawesi | 6 | 17 |

| North Sulawesi | 8 | ||

| Gorontalo | 4 | ||

| Southeast Sulawesi | 3 | ||

| Central Sulawesi | 1 | ||

| Maluku | North Maluku | 4 | 6 |

| Maluku | 2 | ||

| Papua | Papua | 2 | 5 |

| West Papua | 2 | ||

| Highland Papua | 1 | ||

| Grand Total | 172 | ||

| Forest State by Function | Social Forestry Scheme | Sites | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Forest Park | Non-Social Forestry | 8 | 8 |

| Hunting Park | Non-Social Forestry | 1 | 1 |

| National Park | Customary Forest | 1 | 60 |

| Forestry Partnership | 3 | ||

| Community Forest | 1 | ||

| Non-Social Forestry | 55 | ||

| Nature Forest Reserve | Village Forest | 3 | 7 |

| Non-Social Forestry | 4 | ||

| Nature Recreational Park | Village Forest | 1 | 20 |

| Community Forest | 1 | ||

| Non-Social Forestry | 18 | ||

| Wildlife Forest Reserve | Non-Social Forestry | 3 | 3 |

| Protected Forest | Forestry Partnership | 1 | 71 |

| Village Forest | 4 | ||

| Community Forest | 13 | ||

| Non-Social Forestry | 53 | ||

| Nature Reserves and Nature Preservation Forest | Non-Social Forestry | 2 | 2 |

| Grand Total | 172 | ||

| No. | Ecoregion Type | Total | No. | Ecoregion Type | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Structural Mountains | 38 | 9 | Denudational Plains | 5 |

| 2 | Structural Hills | 36 | 10 | Structural Plains | 4 |

| 3 | Volcanic Mountains | 33 | 11 | Organic/Coral Plains | 3 |

| 4 | Fluvial Plains | 12 | 12 | Denudational Hills | 2 |

| 5 | Marine Ecoregion | 11 | 13 | Denudational Mountains | 2 |

| 6 | Volcanic Hills | 10 | 14 | Karst Hills | 1 |

| 7 | Peatland | 8 | 15 | Organic/Coral Plains | 1 |

| 8 | Volcanic Plains | 6 | Grand Total | 172 | |

| Variable | Permutation Importance (%) | Variable | Permutation Importance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 49.7 | Slope | 3.8 |

| Annual Temperature | 22.5 | Elevation | 2.3 |

| Vegetation density | 12.5 | Annual Precipitation | 0.6 |

| Settlement | 8.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sisriany, S.; Furuya, K. Understanding the Spatial Distribution of Ecotourism in Indonesia and Its Relevance to the Protected Landscape. Land 2024, 13, 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13030370

Sisriany S, Furuya K. Understanding the Spatial Distribution of Ecotourism in Indonesia and Its Relevance to the Protected Landscape. Land. 2024; 13(3):370. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13030370

Chicago/Turabian StyleSisriany, Saraswati, and Katsunori Furuya. 2024. "Understanding the Spatial Distribution of Ecotourism in Indonesia and Its Relevance to the Protected Landscape" Land 13, no. 3: 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13030370

APA StyleSisriany, S., & Furuya, K. (2024). Understanding the Spatial Distribution of Ecotourism in Indonesia and Its Relevance to the Protected Landscape. Land, 13(3), 370. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13030370