Abstract

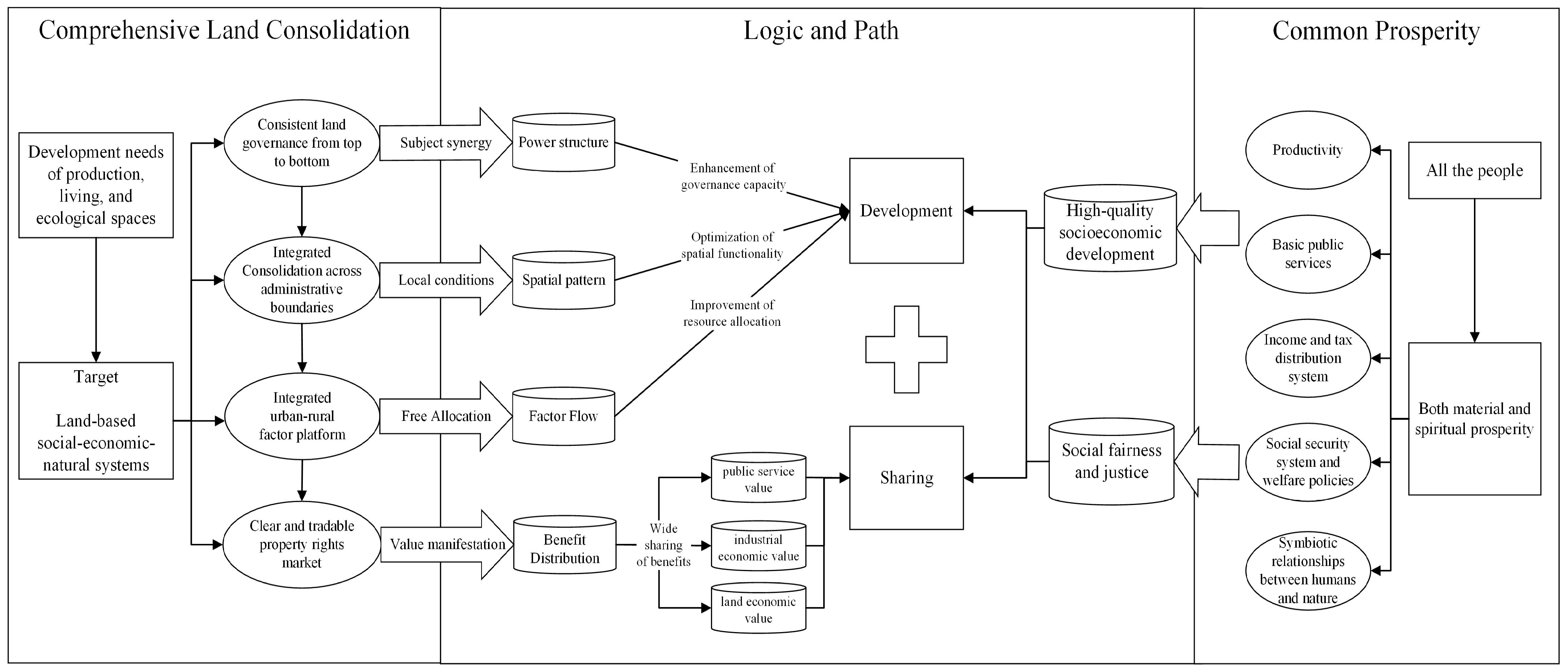

Eliminating poverty and achieving social justice are global concerns. China has focused on common prosperity. Comprehensive land consolidation is a potential policy tool that can contribute to common prosperity, but its effectiveness and implementation methods are yet to be verified and discussed. Therefore, we construct an analytical framework to understand how comprehensive land consolidation promotes common prosperity. The pilot area for comprehensive land consolidation in Ningbo City is used as a qualitative case study. The research results indicate that comprehensive land consolidation focuses on development and sharing to promote high-quality socio-economic development, social fairness, and justice. The paths for achieving development included the following: (1) a network governance structure consisting of multiple entities to enhance land governance; (2) various consolidation activities were conducted at the town scale to optimize the functionality and spatial pattern of public spaces; and (3) enabling the flow of urban and rural factors for improved resource allocation efficiency and providing an impetus for industrial development. The paths for achieving sharing included clarifying collective land ownership and promoting land transactions to provide diverse land values and ensure a shared distribution. This research provides new insights applicable to other Chinese cities and numerous developing countries engaged in land consolidation to address social distribution issues.

1. Introduction

Achieving social justice is a global issue [1]. In 2015, the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including “eradicating poverty” and “social equality”, making a historic commitment. The primary goal is to eliminate poverty in every corner of the world [2]. Against the backdrop of increasing wealth disparity in many countries over the past few decades, reducing social unemployment, increasing per capita income, and narrowing social distribution gaps are concerns of governments globally, particularly in developing countries. China, the world’s largest developing country with the largest population, faced a daunting poverty reduction task because 66.3% of its population lived in poverty in 1990 [3]. In 2015, the Chinese government announced the implementation of the targeted poverty alleviation strategy, achieving significant milestones. By 2021, the Chinese government declared that, according to the World Bank’s USD 1.9/day poverty standard (2011 PPP), 98.99 million people in China had successfully lifted themselves out of extreme poverty, reducing the poverty rate to 0.7%. China’s contribution to global poverty reduction exceeded 70%, making it the country with the highest number of people lifted out of poverty worldwide [4].

The elimination of extreme poverty is not the endpoint. The American economist Kuznets has stated that income inequality follows an inverted U-shaped curve during economic growth, expanding initially and then contracting [5]. Post-World War II, many developed Western countries established comprehensive welfare systems to address income inequality, commonly achieved through progressive personal income taxes, more social policies, and commitments to higher levels of social security [6,7]. Since the beginning of economic reforms in China, there has been a long-standing emphasis on prioritizing economic development. However, the quality and sustainability of economic development in less developed regions have been insufficient. Absolute disparities exist in the allocation of basic public services, such as housing, education, and healthcare. Social security expenditures for urban and rural residents exhibit significant mismatches, and the tax system is not progressive [6,8]. In response to these challenges, the Chinese government has proposed a steadfast promotion of “common prosperity” to facilitate the achievement of governance objectives, such as eliminating poverty and achieving social equality. This initiative is also seen as a response to the SDGs.

“Common prosperity” shares similarities with “residents’ well-being” and “shared prosperity”. Residents’ well-being is typically addressed in urban research. Scholars in Europe and the United States have investigated public health and environmental fairness [9]. Research has focused on increasing urban green spaces to address environmental injustice and public health disparities, meeting the urgent need to improve urban ecology [10]. Improving environmental conditions has a positive impact on residents’ quality of life and happiness [11]. Previous studies have identified material well-being, health, safety, psychological satisfaction, and good social relationships as important indicators of residents’ well-being [12]. On the other hand, “shared prosperity” aims to increase the income of the bottom 40% of the population, comprising low-income and vulnerable groups; it has become a new indicator of national progress and citizen happiness [13]. This concept emphasizes that economic growth is sustainable and meaningful only when everyone benefits from economic activities [13]. Inclusive growth and sustainable development are two critical factors influencing shared prosperity. The former emphasizes the compatibility between economic growth and equitable opportunities, and the latter focuses on the sustainability of growth and sharing [14]. Research on residents’ well-being and shared prosperity has provided international insights for developing a theory and selecting goals to achieve common prosperity in China.

Land consolidation is an effective policy tool to achieve socio-economic development. This concept originated in Germany. Land consolidation has a long history in Europe [15]. Traditional land consolidation involves the reorganizing and rearranging of land parcels and their ownership to address land fragmentation [16,17]. Land consolidation in the Slovak Republic is the result of historical conditions and the persistent fragmentation of land ownership [18]. Furthermore, research has been conducted on the legislation regarding land valuation to ensure that legislation regulating the state’s entry into the freedom to dispose of land corresponds to the needs of society and the rights of the parties involved [19]. Due to socio-economic development, land consolidation has become a crucial policy tool for promoting rural development, advancing modern agriculture, and achieving ecological restoration. Land consolidation in Eastern Europe has mitigated rural decline triggered by urbanization, promoting sustainable development in rural and agricultural economies [15,20]. Land consolidation in China has shifted from a singular focus on agricultural development to a development-oriented approach based on social, economic, and ecological needs [16]. The positive outcomes of land consolidation in China include maintaining a dynamic balance in arable land quantity, improving rural production and living conditions, clarifying and adjusting land ownership, alleviating regional conflicts between people and land, optimizing urban–rural spatial patterns, and achieving significant results in environmental friendliness and ecological restoration [21,22,23,24]. Land consolidation has the potential to promote common prosperity.

The policy objectives of land consolidation in China have evolved through three stages. The first stage focused on increasing the arable land area, improving land quality, and increasing tradable construction land to maximize the economic benefits of land output [25]. The second stage emphasized adjusting land property rights, organizing land use, and protecting the environment to achieve balanced and coordinated development of the economy, population, resources, and environment [26]. The third stage focused on promoting the national governance goals of modernization, ecological civilization construction, rural revitalization, and urban–rural integration [27]. The policy objectives of land consolidation reflect changes in the government’s governance values, which is one reason for conducting this study.

However, China’s past land consolidation has focused on achieving socio-economic development, but to some extent, they have neglected the protection of land ownership, especially the rights of farmers. This has led to issues related to the distribution of interests based on land ownership and has become a crucial concern that needs special attention in promoting common prosperity through comprehensive land consolidation. With the continuous emphasis on common prosperity by the Chinese government, whether comprehensive land consolidation can serve as an effective policy tool for promoting common prosperity, and how to implement it, are yet to be verified and discussed. Therefore, based on the practical investigations in the pilot area of Ningbo City, this paper aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of comprehensive land consolidation as a policy tool, reveal its inherent logic and implementation path, and provide spatial governance experience and policy suggestions for promoting common prosperity and addressing current social contradictions. The research findings also have implications for cities in Southeastern China and other major cities in Asia engaged in land consolidation and promoting social justice.

The remainder of this paper is organized into five parts. Section 2 describes the establishment of a theoretical logical framework based on a literature review and policy evolution. Section 3 provides an overview of the research area and the methods employed for data collection. Section 4 presents the implementation path for the case study. Section 5 provides the discussion, and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. The Theoretical Framework of Comprehensive Land Consolidation for Promoting Common Prosperity

2.1. Common Prosperity

The concept of common prosperity originates from Karl Marx’s economic theories [28]. In his work “Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts”, Marx posited that the rapid development of social productive forces would lead to production to increase everyone’s prosperity, meeting the needs of everyone without sacrificing the needs of individuals [29]. This belief is the essence of common prosperity, namely, developing productivity and achieving fair social distribution. The social security and welfare systems in developed countries can provide insights for China to achieve common prosperity. The “Beveridge Report” analyzed the causes of poverty in the United Kingdom, emphasizing that social security must be a joint responsibility of the state and individuals. Citizens should seek private welfare benefits in the market, and the state has a remedial role in meeting individual welfare needs. Social insurance is considered a fundamental social policy, providing income security and eliminating poverty [30]. Continental European countries like Germany and France advocate corporatism, relying on social organizations (churches and charities) and communities to provide citizens with welfare services and protection through substantial payments [30,31]. Nordic countries, renowned for their high-welfare models, emphasize the importance of equal citizen rights and redistribution. They provide extensive welfare protection for the entire population by providing pensions, free education, unemployment insurance, medical insurance, and housing supply to eliminate social poverty and distribution problems [32]. The United States government, which emphasizes the work ethic and the freedom of individuals, reinforces the value of social sharing. By implementing limited and decentralized relief policies, it has effectively controlled social poverty and racial issues [31]. Despite differences or emphases in the responsibilities, distribution methods, and employment structures among various social security models, all are based on the growth of social wealth redistribution and equal rights for citizens of different classes. These concepts are in line with common prosperity to achieve productivity development and fair social distribution.

The concept of common prosperity has acquired a more explicit connotation based on the experiences of Western countries and the practical context in China. The Tenth Meeting of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs of the Communist Party of China stated that common prosperity entails affluence for all, encompassing the material and spiritual well-being of the entire populace [33]. Scholars have argued that China’s commitment to common prosperity seeks to diminish the disparities in living standards across different social strata, between urban and rural residents, and among individuals in economically developed and underdeveloped regions. Additionally, it encompasses the widespread enjoyment of spiritual confidence, a livable environment, social harmony, universal access to public services, and abundant sharing of cultural products [29]. Achieving common prosperity is a national goal; it is a comprehensive and gradual process [34], emphasizing the balance between the development of the market economy and the promotion of social equity. Therefore, the economic and social goals of common prosperity encompass the following governance components: (1) achieving high-quality productivity development; (2) ensuring equal access to basic public services for residents; (3) adjusting the distribution system for residents’ income and taxes; (4) refining the social security system and welfare policies; and (5) enhancing the sustainability of symbiotic relationships between humans and nature.

Similar to the governance practices of developed Western countries, the five governance components of common prosperity have two target dimensions: development and sharing. Development involves enhancing productivity to achieve high-quality growth and sustainability in society, economy, and ecology. It envisions a system where all people have equal opportunities and capabilities to participate, providing ample material security and wealth accumulation through fair social distribution. On the other hand, sharing involves compensating for and rectifying inequalities caused by institutional factors through initiatives, such as the widespread provision of public services, the reformation of the tax system, and the refinement of social security. This approach ensures that all people can share the fruits of economic and social development to achieve social fairness and justice.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

The policy requirements for land consolidation serve as the starting point for analyzing this process. These requirements reflect the policy’s goals and values and determine the measures and targets of land consolidation. Different land consolidation measures result in different land-use patterns and require different implementation paths. The ultimate effects of land consolidation for different paths promote development and sharing.

The continuous expansion of urban and rural construction land in China has reduced agricultural land and conservation areas and caused significant environmental pollution and ecosystem degradation. This effect has exacerbated the imbalance between the supply and demand for production, living, and ecological spaces, hindering productivity development and social equity [35]. Unlike traditional land consolidation, the comprehensive land consolidation implemented since 2019 is based on the development needs of production, living, and ecological spaces. This approach regards land as a complex “social–economic–natural” system. The consolidated land types include agricultural, industrial, ecological, idle or inefficient urban, and transportation land and villages. Comprehensive land consolidation adjusts the basic elements and spatial structure of urban and rural land, population, industry, ownership, and other factors. It optimizes the land-use functions, reshapes the spatial value of urban and rural areas, systematically promotes integrated urban and rural development, and coordinates the relationship between people and land [36]. On the basis of a reliable finding of ownership and usage and related property rights [37], the comprehensive land consolidation can achieve efficient and fair land-use allocation. Since its goal is common prosperity, comprehensive land consolidation includes the use of policy tools, such as land taxation, industrial development, increasing the value of resource products, and transfer payments [38].

The following four points are considered in the remedial measures and implementation paths:

- (1)

- Change in Power Structure: The power structure is the foundation of China’s spatial planning and operations [39]. The hierarchical structure of land consolidation policies requires the coordination of higher-level governments and responses from local entities. Traditional land consolidation policies rely on top–down administrative orders, lacking public participation and oversight. The passive choices of local entities like farmers lead to economic challenges [40]. Comprehensive land consolidation is based on national land-use planning, emphasizing a coordinated consensus between higher-level governments and local entities. In the pursuit of maximizing individual interests, a “competition–cooperation” relationship is established among different entities, changing the land governance structure. The bidirectional interaction between entities from top to bottom and bottom to top forms a collaborative network governance structure, improving governance alienation caused by government dominance [41] and significantly enhancing land governance capability.

- (2)

- Optimization Spatial Patterns: Comprehensive land consolidation breaks through administrative boundaries, facilitating the optimization of land-use spatial patterns. The cross-boundary adjustment of spatial patterns prevents the local protectionism of administrative forces [42], achieving a unified goal-oriented and functional spatial layout and avoiding functional inconsistencies caused by economic rationality. It enables the maximization of remediation benefits for different land types, improving public services and infrastructure, and ensuring the coordination and sustainability of spatial patterns. It is worth noting that the premises of adjustment are the public interest or the law, only to the extent necessary, and in return, for reasonable compensation [37].

- (3)

- Adequate Factor Flow: Urban and rural areas are inseparable. However, the household registration, rural land, and human–land systems pose institutional barriers to urban–rural interaction and integration [43]. The advancement of land governance policies allows comprehensive land consolidation to bypass inherent institutional barriers, changing the urban–rural dual structure. It serves as a platform for the flow of urban and rural factors, opening channels for the free flow of urban and rural resources. It facilitates the flow of urban factors to rural areas, reducing the cost and risk of factor flow [44], improving the efficiency and autonomy of factor allocation, and enhancing production quality and efficiency. In addition, it improves rural infrastructure and public services, ensuring that scarce urban factors flowing into rural areas remain in rural areas. Thus, the types and scale of the rural factor pool are expanded, improving the endogenous development capacity of rural areas [44].

- (4)

- Sharing Benefit Distribution: After defining land property rights, market competition and transaction mechanisms can improve the land value, resulting in diverse land outputs [45]. In Ukraine and some European Union countries, the lack of a stable land market and legislation at the required level in this field has led to the possibility of restricting foreign ownership of land to prevent the potential loss of valuable land [46]. In China, there has been a long-standing issue of unclear rural property rights, vague subjects, discrimination, and inequality regarding urban and rural land property rights [47]. These problems have reduced the land value and the potential benefits. Comprehensive land consolidation adjusts the power structure, land-use patterns, and factor flow, improving transactions and land property rights to achieve high-quality productivity development. Land consolidation benefits are diverse. The benefits include improved public service and higher land and industry values. Moreover, the collaborative participation of multiple entities in the consolidation model allows more people to participate in the distribution of benefits.

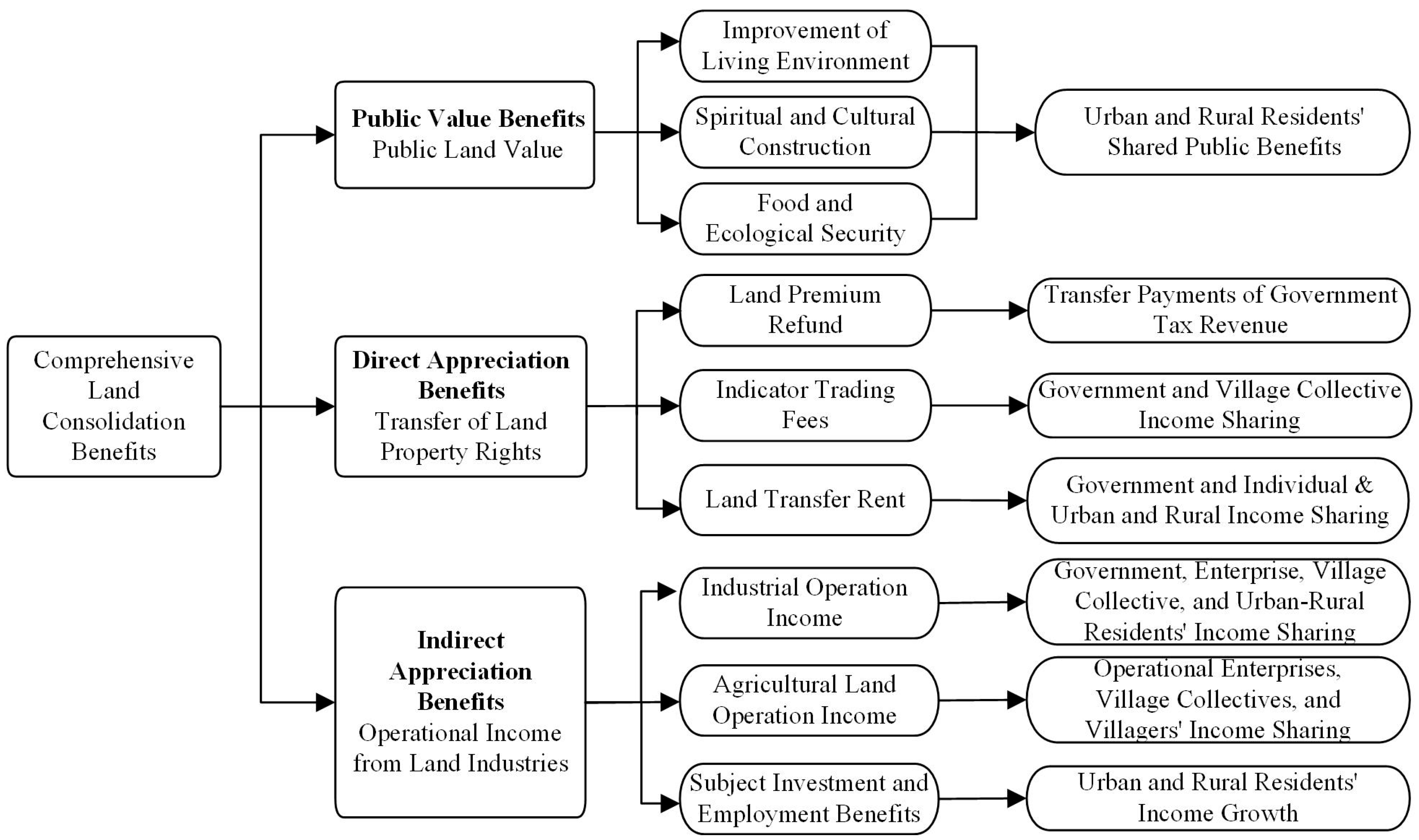

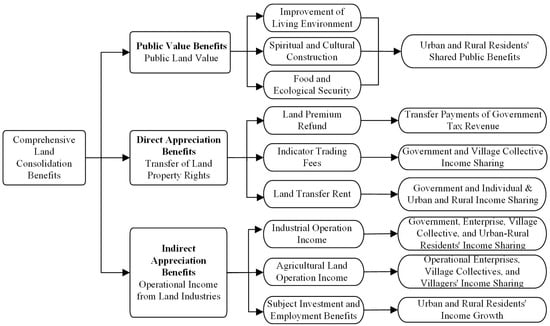

Comprehensive land consolidation promotes common prosperity through development and sharing (Figure 1). The paths for achieving development include changes in the power structure, land-use patterns, and factor flow: (1) collaborative governance ensures local residents’ rights to be informed, participate, and make decisions; (2) a coordinated land-use pattern ensures equal functions and services; and (3) the free interaction of urban and rural elements provides crucial support for achieving high-quality productivity development. The path for achieving sharing includes income distribution. The benefits of land consolidation include improved public services, high-quality industries, and the redistribution of land transfer fees. These benefits improve employment, tax reform, social security, cultural heritage, living environment, and ecological governance. Comprehensive land consolidation fosters high-quality economic and social development, promotes social fairness and justice, and addresses imbalances in the current Chinese society. It serves as an effective governance tool for achieving common prosperity.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework of comprehensive land consolidation to promote common prosperity.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

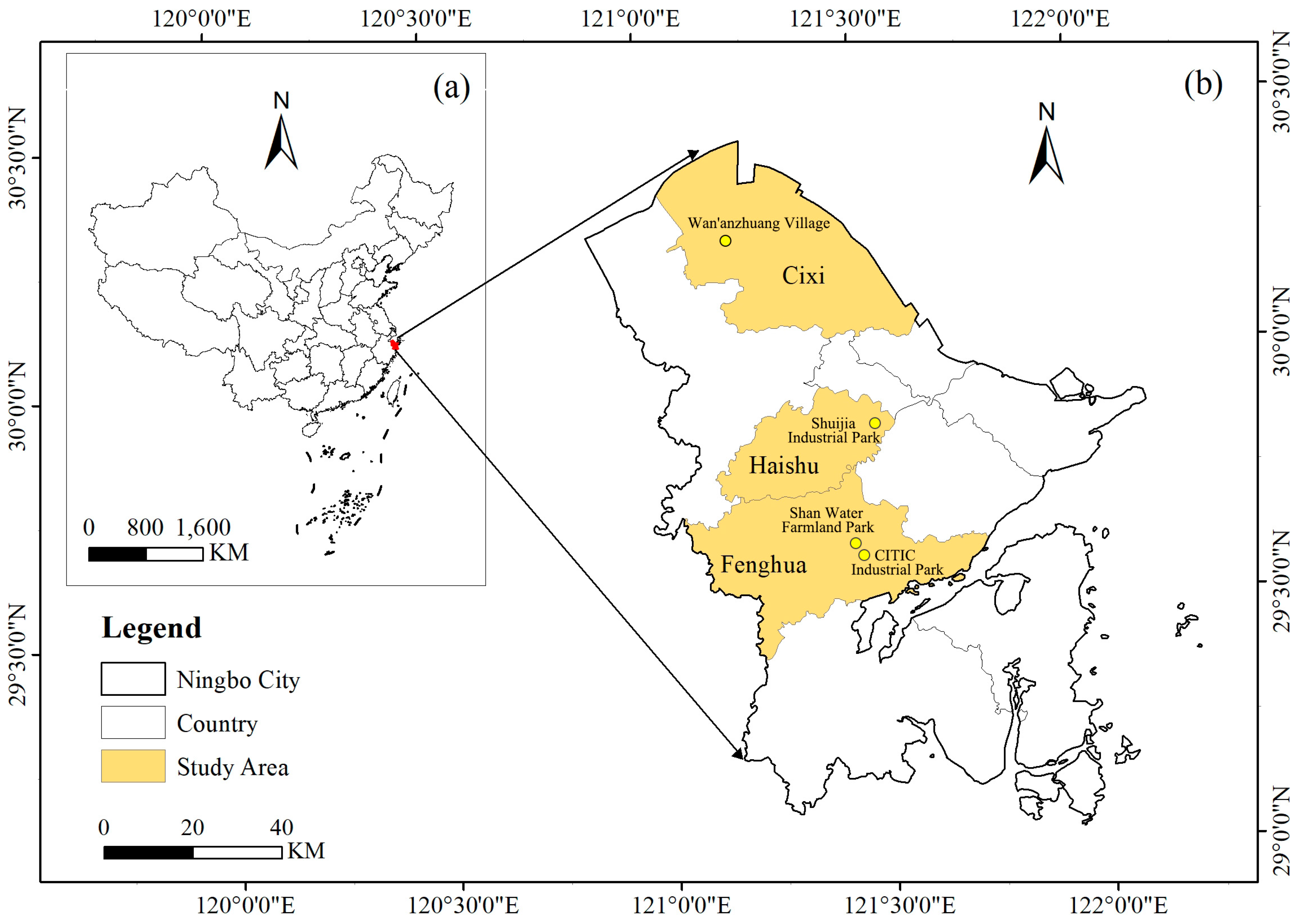

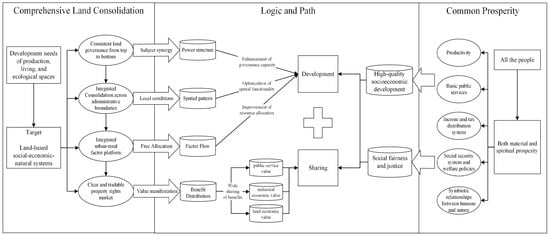

Ningbo City is located in Zhejiang Province, China (28°51′ N–30°33′ N, 120°55′ E–122°16′ E), on the southern side of the Yangtze River Delta. It is an important financial and economic center and an international port city in Zhejiang Province. Ningbo plays a crucial role in the integrated development of the Yangtze River Delta and the coordinated construction of the Shanghai metropolitan area, being a key growth pole of the region (Figure 2). In 2019, the Ministry of Natural Resources launched a pilot program for comprehensive land consolidation across the country, choosing Ningbo as one of the pilot cities. The city has been actively promoting farmland consolidation, village improvement, ecological protection and restoration, industrial land consolidation, and the redevelopment of inefficient urban land. As part of the nationwide efforts to build demonstration zones for common prosperity, Ningbo was designated a pilot city in 2021 to construct a demonstration zone for common prosperity. In 2022, Ningbo City issued Opinions on Carrying Out Comprehensive Land Consolidation to Promote High-Quality Development and Build a Pioneer City for Common Prosperity, integrating comprehensive land consolidation to achieve common prosperity. The objective was to achieve high-quality urban development focusing on the “satisfaction of the people, improvement of arable land, increased grain production, enhanced disaster reduction capabilities, and improvement of the environment”. This initiative aims to provide exemplary experiences for promoting common prosperity.

Figure 2.

Location of Ningbo City (a) and case study area (b).

As a pilot region with multiple policies, Ningbo City has made significant progress and accumulated governance experience, making it representative of the region’s land consolidation characteristics. Thus, this area is suitable for assessing the implementation paths of comprehensive land consolidation in the region to promote common prosperity. The research findings provide valuable insights and references for other cities in Southeastern China engaged in land consolidation to achieve common prosperity. As the current comprehensive land consolidation pilot project in Ningbo City is still in the initiation phase, we selected four typical projects from the Fenghua, Cixi, and Haishu districts as study cases (Figure 2) based on criteria such as geographic location, consolidation type, project scale, and work progress. These four typical projects that we have chosen can provide a practical comparison to reflect the overall progress and achievements of the current land consolidation efforts in Ningbo City.

3.2. Research Methods

This study employed a qualitative approach, using semi-structured interviews, on-site investigations, and observations to collect information and investigate how comprehensive land consolidation contributes to common prosperity. We conducted three rounds of on-site investigations in March, June, and September 2023. We interviewed officials from the Ningbo Municipal Government, district-level governments in Fenghua, Haishu, and Cixi, the leadership team for comprehensive land consolidation, state-owned enterprises involved in the implementation, and township and village committees in each district to obtain information on the progress and challenges of comprehensive land consolidation. The research team conducted on-site visits to the Fenghua Shan Water Farmland Park, CITIC Industrial Park, and Haishu Shuijia Industrial Park to assess the government’s involvement, industrial structure, operating entities, funded operations, and employment level. Additionally, the team visited more than 20 villages, including Zhang Village, Wan’anzhuang Village, and Shuijia Village, conducting household interviews to gather information on housing, living conditions, arable land area, employment structure, income, and policy participation. We conducted 63 interviews with 157 participants, including village residents, obtaining extensive data, including 900,000 words of transcribed interviews (Table 1). Soil samples in Fenghua district were collected and analyzed to understand the impact of land consolidation on soil ecology. Moreover, the team obtained and analyzed key policy documents from the central government, Zhejiang Province, and Ningbo City, as well as comprehensive consolidation plans for the pilot areas, ensuring the study’s authenticity and accuracy.

Table 1.

Examples of descriptive statistics in case studies.

4. Results and Analysis: The Implementation Paths of Comprehensive Land Consolidation to Promote Common Prosperity

Traditional land consolidation is often the responsibility of land management departments, focusing on optimizing and reorganizing land elements to meet the demand in societal development. However, its contribution to promoting common prosperity is limited. In practice, comprehensive land consolidation in Ningbo City, as a policy tool, has gained rich and extended implications. Ningbo City considers comprehensive land consolidation as a basic task for conducting various activities related to urban and rural economy, culture, and ecology. It enhances government governance capacity and coordination efforts through collaborative efforts across multiple departments, aligning with the current trend of administrative reform in China. Building upon this foundation, it systematically manages the spatial form and various elements carried by the land to achieve the goal of promoting common prosperity. In this process, designing institutional frameworks for governance methods and profit distribution becomes indispensable. Therefore, this study conducts case studies by combining the theoretical implications of comprehensive land consolidation with the practical process in Ningbo City.

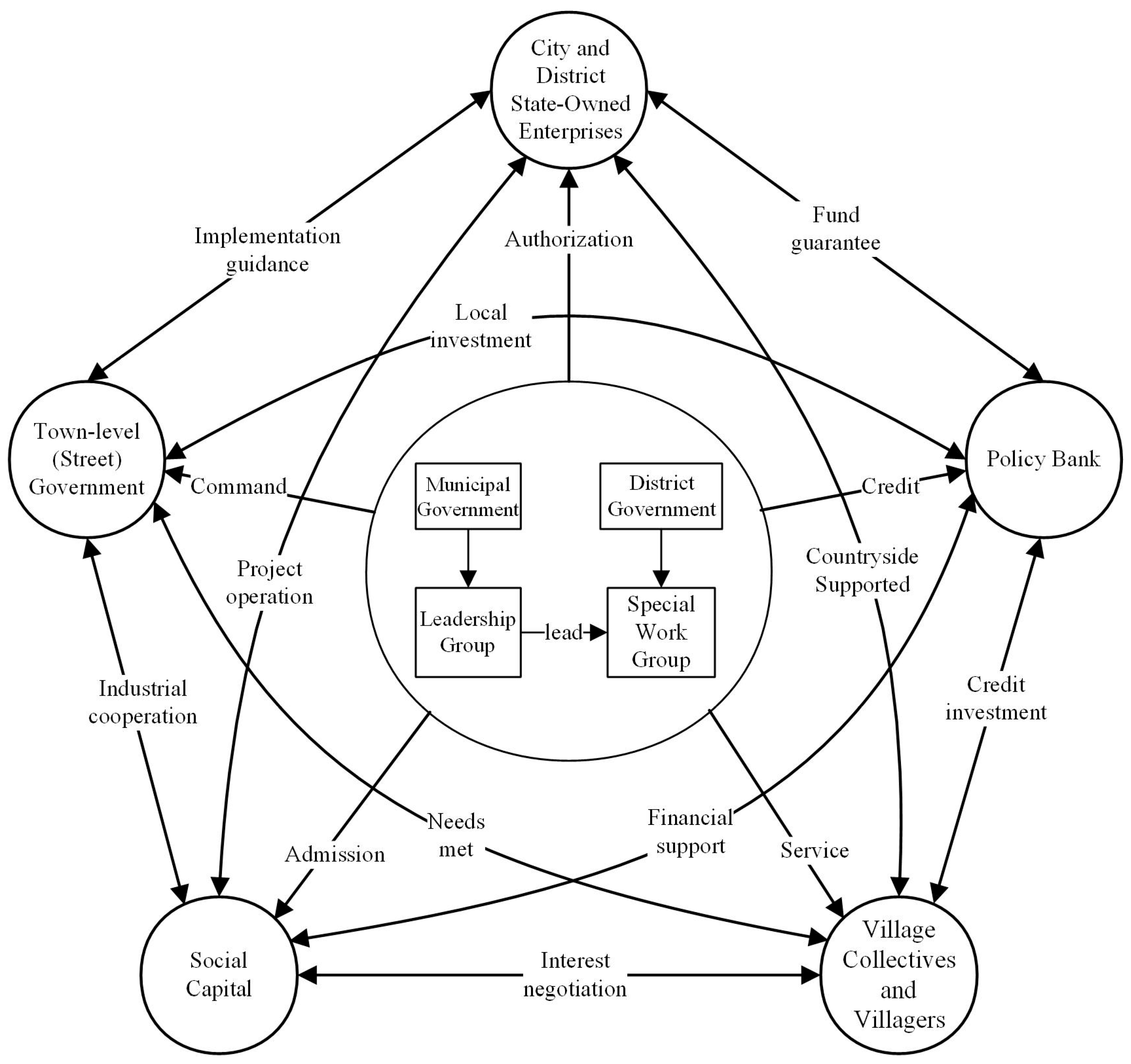

4.1. The Network Governance Structure

Network governance is an interactive social governance process that promotes collaboration and shared governance among diverse entities, such as government, non-governmental organizations, and citizens, to maximize public interests [48]. This organizational structure is based on ethics, democracy, political interaction, citizen participation, and responsiveness to achieve social equity [49]. Dedicated working groups for land consolidation are the core of a network governance structure. At the municipal level, the Ningbo City government created the Comprehensive Land Consolidation Leadership Group. At the district (county) level, local governments established the Comprehensive Land Consolidation Special Working Group. Members of the two-tier government working groups come from more than 20 government departments, including the Natural Resources and Planning Bureau, Agriculture and Rural Affairs Bureau, Big Data Bureau, Development and Reform Commission, Industry and Information Bureau, Ecology and Environment Bureau, Housing and Urban-Rural Development Bureau, Water Resources Bureau, Finance Bureau, State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, and Financial Regulatory Bureau. They represent the government’s responsibilities in the planning, decision making, leadership, coordination, and supervision of consolidation projects. State-owned enterprises at the municipal and county levels are the primary implementers of the projects. They are responsible for planning services, obtaining funds and credit, administrative guidance, industrial development, and implementation authorization. In addition, town-level governments, village collectives, and villagers are involved in project implementation. Social capital related to industries is developed, and advanced technologies are incorporated, balancing the financial pressure while ensuring the interests of local entities and individuals. Policy banks provide various forms of financial support to different entities through fiscal and financial channels. The interactive governance process among different entities is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Network governance structure of comprehensive land consolidation in Ningbo City.

In the land consolidation project in Shan Water Farmland Park, Fenghua District, comprehensive land consolidation was used for resource exchange, information sharing, and the redistribution of benefits among different entities. Before the comprehensive land consolidation, Shan Water Farmland Park primarily consisted of farmland, woodland, and various flower plantings and peach orchards. The long-term cultivation of flowers and trees had resulted in significant soil compaction and low-quality arable land. The Fenghua District government was the planning entity. It responded to the policy requirements of the Ningbo City government and guided the implementation of the land consolidation project. The Agricultural and Commercial Group, a state-owned enterprise, acted as the government-authorized agent responsible for advancing the consolidation project. It provided financial support for arable land consolidation, land-use right transfer, and bidding operations. The policy banks primarily issued special bonds, serving as the main financing channel for the government. The Daoji Agriculture Company, a social capital entity, was responsible for managing the agricultural land after its transfer. It developed new types of agricultural production and business activities to generate income. According to the cooperation agreement, a portion of the income was shared with the Fenghua District government and the state-owned enterprise, Agricultural and Commercial Group. The government and the state-owned enterprise regarded this as a main source of recovering capital costs. The village committee and villagers had the right to establish homesteads and use the arable land. During the consolidation and transfer, they negotiated and bargained with the government. They obtained income from the land transfer and were employed in the arable land operation, increasing job opportunities and income.

According to China’s second soil census nutrient classification standards, we conducted a nutrient indicator grading assessment on the farmland (rice fields) soil in Shan Water Farmland Park. The results indicate that the farmland soil in Shan Water Farmland Park is weakly acidic (pH = 5.79), with a medium-to-low level of organic matter content (18.2 g/kg), abundant levels of available phosphorus (28.8 mg/kg), and extremely rich levels of available potassium (925 mg/kg). According to Cultivated Land Quality Grade (GB/T 33469–2016) (farmland quality grading in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River), and the current soil conditions of Shan Water Farmland Park, the overall quality level of the farmland is approximately at a Grade Four level. The soil pH falls within the range of Grade One to Grade Four (5.5~8.0); the organic matter content is within Grade Six to Grade Eight (15~30 g/kg); the soil nutrient status is at an abundant level, roughly falling within Grade One to Grade Three; the heavy metal content in the soil is within the range of risk control, and no organic pesticides or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons have been detected, indicating that the soil is at a clean level; furthermore, the effective soil layer thickness in the farmland is >100 cm, indicating a higher level.

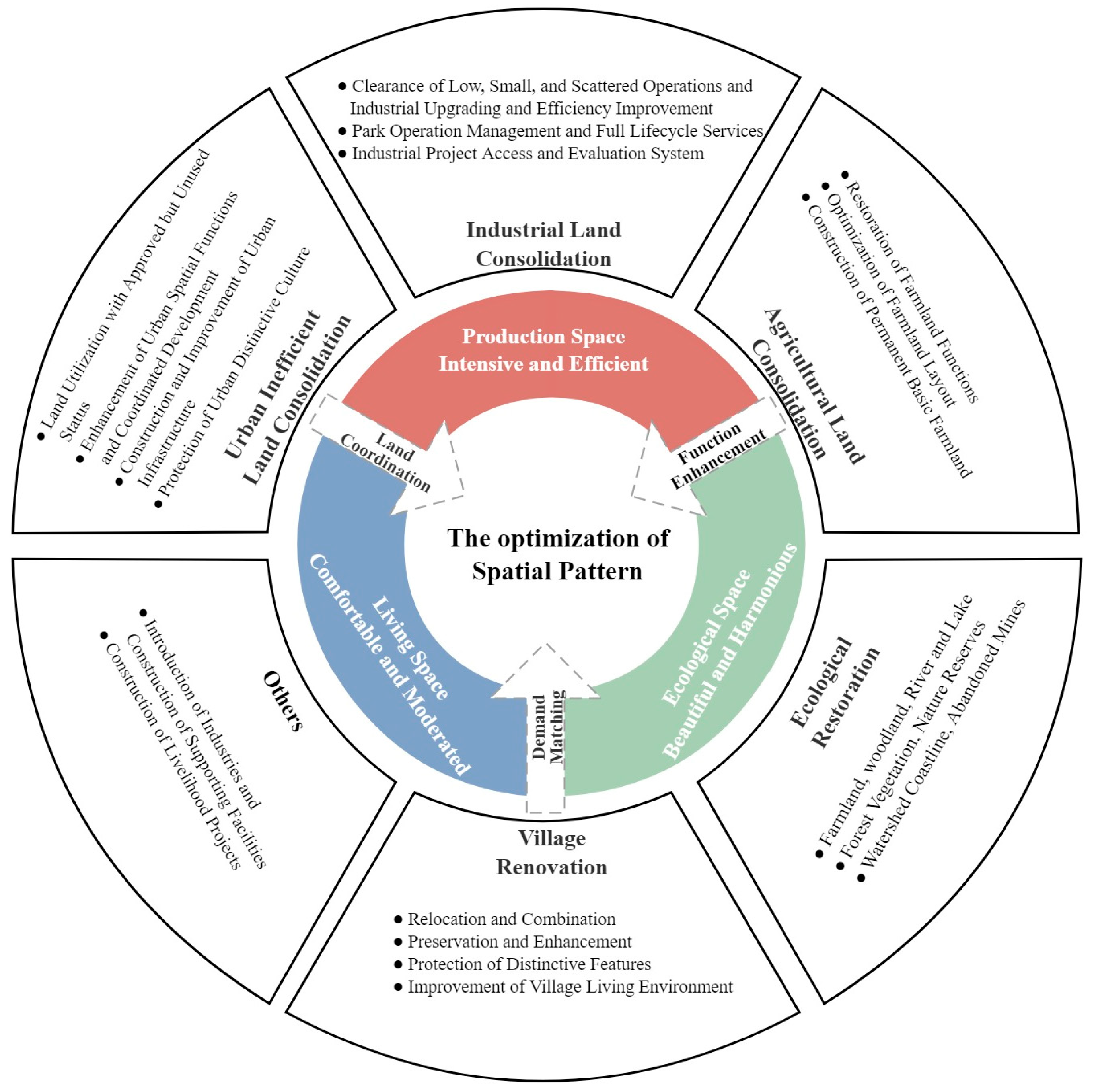

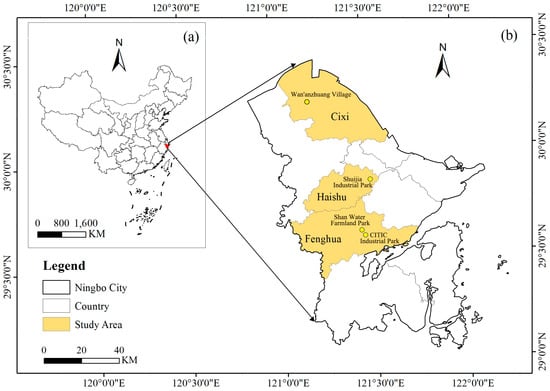

4.2. The Optimization of the Spatial Pattern

Optimizing the land-use pattern improves social development. It transforms strong conflicts resulting from the land-use patterns into weak conflicts (coordination), maximizing land-use efficiency [50]. The comprehensive land consolidation in Ningbo overcame the constraints of specific administrative regions and was not limited to traditional farmland or agricultural spaces. Based on the land-use suitability and spatial pattern, it involved merging scattered farmland, organizing homesteads, restoring rivers and lakes, addressing abandoned mines, and improving inefficient construction land. These initiatives enhanced the intensity of cultivated land use, the efficiency of construction land, and the ecological health of the land by optimizing the land-use patterns for production, living, and ecological purposes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Optimization of spatial pattern in comprehensive land consolidation in Ningbo City.

The adjustment of the spatial pattern in different townships (streets) was achieved in the industrial land consolidation project of the CITIC Industrial Park in Fenghua District. The layout of industrial, residential, financial, technological, and ecological zones in the project area was optimized to integrate these areas by comprehensive land consolidation. The CITIC Industrial Park in Fenghua District is located between the Jiangkou, Xiaowangmiao, and Jinping streets, encompassing a village. Prior to the comprehensive land consolidation, the region had a mix of industry and residential areas, mainly consisting of small industrial buildings, with an average tax revenue of less than CNY 100,000 per mu. The consolidation primarily involved relocating the industrial blocks to create an industrial area that integrated production, residential, and commerce areas to ensure that the area was suitable for production, living, and business. The project was entrusted to the CITIC City Development (Ningbo) Co., Ltd., which was responsible for demolition, construction, investment attraction, and operation. The demolition primarily targeted outdated enterprises that did not meet the development goals and output value requirements. Development and construction included primary land development, organization, and infrastructure construction, such as municipal roads, water systems, and green spaces. Investment attraction focused on bringing in high-value-added industries, such as electronics, new materials, high-end manufacturing, and healthcare industries. The operation provided support for developing residential and commercial buildings and parks, including residential areas, restaurants, commercial centers, entertainment venues, national laboratories, technology transfer centers, logistics, environmental protection, and other public supporting services. The company was responsible for property management. The optimization of the spatial pattern resulted in industrial transformation, upgrading, and urbanization.

4.3. The Movement of Urban and Rural Factors

The flow and allocation of production factors between urban and rural areas determine urban and rural development levels [51]. Ensuring the free movement of factors, such as land resources and capital, ensures the optimal allocation of resources in a broader spatial range in urban and rural areas, ultimately achieving urban–rural integration and coordinated development [52]. Comprehensive land consolidation in the entire region using measures such as coordinating increases and decreases in urban and rural construction land, social capital investment, and rural industry development improves the value of land for living, production, and operation. Thus, land consolidation fosters the exchange and movement of urban and rural factors. The optimization of the governance structure and spatial pattern removes obstacles to the sufficient flow of factors, including urban industries, population, capital, technology, education, and information. This flow into rural areas through land governance improves rural productivity by promoting advanced industries and technologies. Conversely, rural factors, such as land, products, labor, environment, and culture, flow into urban areas through the joint operations of government–enterprise partnerships and village collectives, entering urban consumption markets.

Urban funds, technology, information, and the labor force were some of the factors flowing between urban and rural areas in the village renovation project in Wan’anzhuang, Cixi City. This approach revitalized rural land resources and improved the factor flow of the economy, providing endogenous power for rural development. Wan’anzhuang utilized urban capital and developed new technology to create new businesses, such as the Taizhou Gu Zhi Yuan Beverage Co., Ltd., a service center for specialty agricultural products encompassing production, storage, processing, and sales. This development focused on cultivating specialty agricultural products like bayberries and yellow rosewood and included the brand management of agricultural products. The project also provided support for developing Cixi City’s Small Appliance Intelligent Manufacturing Town, creating a service facility with office spaces and exhibition displays, focusing on innovation, entrepreneurship, and e-commerce live broadcasting. Without increasing the construction land, Wan’anzhuang used an old farm to create a 120-acre shared farm, adopting a scenario based on the local farming culture. This farm is operated by an urban professional team that established a shareholder cooperative called “Farmers + Farm + Village Cooperative + Operating Team”. This cooperative model represents an intelligent shared farm focused on U-picking, harvesting, planting, experiencing, and sightseeing tourism.

4.4. Sharing Benefits from Comprehensive Land Consolidation

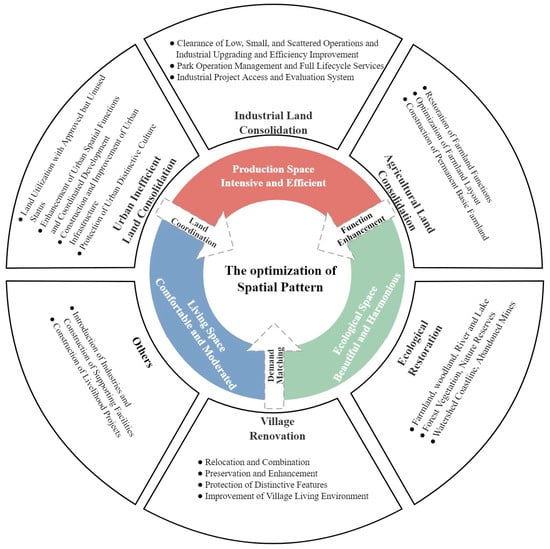

It is crucial to provide guarantees for the rational sharing of land benefits to ensure the rights and responsibilities of all stakeholders and achieve common prosperity [53]. Clearly defined property rights can reduce transaction costs and promote efficient land transfer [54]. The comprehensive land consolidation in Ningbo improves the living environment and infrastructure, raising the level of public services in urban and rural spaces. Coordinated projects, such as digital agriculture, rural study tours, and the reconstruction of community spaces, facilitate the integration of urban and rural areas, highlighting the economic value of land market transactions, rural tri-sector operations, and the transformation of urban and rural industries. Based on these efforts, the goal is to achieve shared benefits in terms of public revenue, operational income from industries, and benefits derived from land (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Shared benefits resulting from comprehensive land consolidation in Ningbo City.

We use the Shuijia Industrial Park in Haishu District as an example. It had problems, such as unclear land property rights, low economic benefits from the collective industrial economy, and a lack of village infrastructure. The comprehensive land consolidation addressed the unclear property rights and unclear lease terms for collectively owned industrial land in the Shuijia Industrial Park. It granted clear property rights for collective industrial land, consolidated fragmented ownership into the hands of the village collective, and facilitated uniform leasing contracts between leasing enterprises and the village collective to resolve ownership disputes. These strategies helped establish long-term and stable property rights relationships, unlocking the potential value of rural industrial land. By building on this foundation, the village collective independently transformed the industrial park by relocating residential and agricultural land within the industrial area, unifying and replacing industrial buildings to separate production and residential areas. Old buildings and inefficient factories were demolished, and standardized industrial buildings were constructed. Additionally, the collective invested in electricity and sewage treatment facilities and road infrastructure, improving the village’s infrastructure. The village collective took charge of leasing operations, and the operational, maintenance, and security costs of the industrial park were covered by the village-level economy. Furthermore, the Haishu District government provided policy support through incentives, such as tax rebates, policy bank financing, and financial subsidies for demolishing and constructing new facilities and supporting the village-level industrial park renovation.

The Shuijia Industrial Park in Haishu District successfully transformed into an inefficient village-level industrial park, obtaining diverse outputs and shared land. These changes improved its public value and living environment, allowing residents to enjoy high-quality public services and improved infrastructure. The rearrangement of land quotas promoted intensive and efficient land use, unlocking the potential value of the village’s collective land. The village collective is expected to generate an annual rental income of CNY 5 million, providing additional income for rural farmers and contributing to the goal of common prosperity. In terms of industrial value, the enterprises in the park were transformed and upgraded. The annual output value is expected to increase to CNY 1.81 billion, a sevenfold increase in per mu tax revenue. The village-level industrial park demonstrated its ability to attract industrial enterprise spillover from urban areas.

It is worth noting that we also identified inevitable endogeneity issues among the four implementation paths mentioned above. Based on our investigation of various cases, we found that making institutional adjustments to the governance structure is the foundation for influencing other pathways, aligning with the general logic of bureaucratic hierarchy. The redistribution of government power, represented by the establishment of the Special Working Group, allows for the planning and adjustment of space based on the needs and interests of different departments and entities, simplifying unnecessary administrative procedures. Simultaneously, the Special Working Group can effectively expand the channels for the flow of various factors within the administrative region, ultimately achieving planning-based benefits sharing.

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Comparison and Implications

Compared with previous studies on the impact of land governance on rural revitalization and urban–rural integration, our research reveals consistencies in the paths or approaches for achieving different social governance goals. A common emphasis exists on promoting the free flow of urban–rural factors, market-oriented land allocation, rational industrial layout, and assistance to vulnerable rural groups [36,55,56]. This consistency stems from the continued policy focus on government objectives, such as urban–rural integration, rural revitalization, and common prosperity, driven by real-world needs. It underscores the adaptability and vitality of comprehensive land consolidation in addressing complex social issues. The difference from the existing research lies in that traditional land governance activities are often confined to the efforts of land management departments. However, against the backdrop of the government’s increasing attention to common prosperity, comprehensive land consolidation in Ningbo involves more participating departments, exhibiting a stronger systematic nature in land governance policies, and a broader coverage of land consolidation benefits.

Our study suggests the necessity of adjusting power structures. Comprehensive land consolidation requires that the government is the primary governing entity. If there is insufficient social capital and rural communities, relying on administrative efforts results in a governance approach lacking dynamism. Governance dominated by administrative forces may be strongly authoritative [57]. Land consolidation in rural areas, such as the concentrated residences of farmers and the restoration of agricultural land functions, may cause short-term losses and face resistance from farmers [58,59]. Adjusting power structures diversifies the entities participating in land consolidation, ensuring a variety of voices and aligning with the expectations of the majority. The ultimate result of power structure adjustment is productivity development and the sharing of development outcomes. Furthermore, our research suggests that comprehensive land consolidation, as a policy tool, needs to pay greater attention to the protection of land ownership. This ensures the equal participation of more stakeholders in the various aspects of land consolidation, which is also a necessary condition for promoting common prosperity. This perspective provides insights into addressing poverty and achieving social equity and justice, serving as a reference for other regions in China and many developing countries worldwide.

Additionally, the importance of cultural heritage and ecological protection should not be underestimated in comprehensive land consolidation. Culture and ecology are closely related for achieving common prosperity. During on-site investigations and interviews in Ningbo, we found that the construction of cultural venues and the development of cultural tourism were dominant in maintaining cultural inheritance. Enhancing the vitality and creativity of culture to meet the increasing spiritual needs of the people is an essential component for achieving common prosperity. Existing research has noted the negative impact of comprehensive land consolidation on the environment [56]. Our soil tests in the farmland of the Fenghua District, Ningbo, also indicated the overuse of phosphorus and potassium fertilizers, and invasive species, such as the channeled apple snail, indicated an increased ecological risk. A study on the European environmental liability regime concluded that the competent national authorities appear as the representatives of the environment, whose protection they are responsible for, while citizens and companies themselves must also prevent, repair, anticipate, avoid, and report environmental damage, or the threats of such damage [60]. Addressing carbon emissions, increasing carbon sinks, and achieving harmonious coexistence between humans and nature are inevitable and critical issues during comprehensive land consolidation to promote common prosperity.

5.2. Relationship to the Theory of Spatial Production

This study’s theoretical logic is related to Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production. The core idea of spatial production theory is that “social space is a product of society”, where changes in physical space are linked to social development processes, social power dynamics, social connections, and the transformations in everyday life [61,62]. Land consolidation with the goal of common prosperity can be regarded as a process based on social relationships and social order. From this perspective, a spatial system can be constructed encompassing an institutional space, an economic space, and a social space [62,63]. Comprehensive land consolidation alters the institutional space, reshaping the power of the governing system and influencing the planning of spatial patterns. Economic space primarily involves the interaction of different entities in the flow of factors and the distribution of benefits. The government promotes resource transfer and the distribution of public values through hierarchical channels, administrative control, and policy guidance. Various market entities participate in factor allocation and benefit acquisition through market price mechanisms. Other entities obtain benefits through agreements and negotiations based on trust. The ultimate goal of changing the institutional and economic spaces is to reorganize social relationships and social order by changing productive forces and the relationship with production, thereby establishing a social space with rational institutions, efficient production, and fair distribution. This goal aligns with the requirements of common prosperity, emphasizing “development and sharing”. Finally, while our study is related to the spatial production theory, the applicability of this theory requires further systematic and in-depth considerations.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

The limitations of this research method include the selection of economically developed regions as case studies, which may limit the generalizability of the conclusions to less developed regions, such as Western China. This limitation is often attributed to differences in government governance models, social inclusiveness, and educational levels among populations in regions with different levels of economic development. Disparities in land resource endowments in different regions also have an impact. Additionally, qualitative case studies rely on policy documents and interviews to provide theoretical explanations and practical foundations for the four implementation paths (power structure, spatial patterns, factor flow, and benefit distribution) in comprehensive land consolidation. We did not conduct a quantitative analysis of the weights or influences of different paths, and their potential endogeneity issues remain to be addressed. Achieving common prosperity is a long-term socio-economic development goal. Therefore, we will perform the long-term tracking and observations of the case study subjects. In the future, we plan to conduct comparative studies between cases or the cross-temporal comparative studies of cases to clarify the framework for achieving common prosperity and validate the sustainability achieved through different paths. We also aim to collect more consolidation data to quantify the impact of comprehensive land consolidation on development and sharing dimensions in socio-economic terms, enhancing the persuasiveness of the research.

6.2. Research Conclusions

China is making efforts to promote common prosperity to eliminate poverty and achieve social justice. Development and sharing are two goals of common prosperity. As China’s land consolidation policy objectives have evolved, the multifunctionality of comprehensive land consolidation has emerged. Comprehensive land consolidation is a feasible policy tool to promote common prosperity. Therefore, this study established a theoretical logical framework and implementation path for comprehensive land consolidation to promote common prosperity. The logical approach consisted of assessing the requirements, determining suitable measures, developing an implementation path, and evaluating the effectiveness. The power structure, spatial patterns, and factor flow are the main paths for development, while the benefit distribution is the path to ensure benefit sharing.

We conducted a qualitative analysis using four typical consolidation projects in Ningbo as examples. The results showed that comprehensive land consolidation promoted common prosperity, achieving development and sharing in the consolidated regions. The case study demonstrated that the paths for achieving development included the following. (1) The formation of a network governance structure involving government, state-owned enterprises, social capital, village committees, and villagers to enhance land governance. (2) Conducting consolidation activities in different towns to optimize the functionality and spatial patterns of public spaces. (3) Facilitating the flow of urban–rural elements, improving the efficiency of resource allocation, such as funds, technology, and information, and providing momentum for the independent development of rural areas. The paths for achieving sharing included clarifying collective land property rights, promoting land transfer and leasing, and providing diverse land values to ensure a shared distribution. Development and sharing promote high-quality socio-economic development and social justice. The research conclusions have implications for cities in Southeastern China and other major cities in Asia engaging in land consolidation and addressing social distribution issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and J.Z.; Methodology, X.Z.; Formal analysis, X.Z., Y.L., J.Z. and X.G.; Investigation, X.Z., Y.L., J.Z. and X.G.; Resources, X.Z., Y.L. and J.Z.; Data curation, Y.L., J.Z. and X.G.; Writing—Original draft, Y.L.; Writing—Review and editing, X.Z., Y.L., J.Z. and X.G.; Visualization, Y.L.; Supervision, X.Z. and X.G.; Project administration, X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 72074143 and 72374139).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Guterres, A. Our Common Agenda; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Un Doc. A/Res/70/1 (25 September 2015). 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Wang, S. Beating Poverty by Means of Developmenta Summary and Evaluation of the Experiences of China’s Large-Scale Reduction of Poverty in the Past 30 Years. Manag. World 2008, 11, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. Report of the ASEAN Regional Assessment of MDG Achievement and Post-2015 Development Priorities; The ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R.J. Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. J. Econ. Growth 2000, 5, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ren, J. Common Prosperity: Theoretical Connotation and Policy Agenda. Cass J. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, X. From negative welfare to positive welfare: A new exploration of welfare system reform in Western countries. J. Soc. Sci. 2004, 8, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- The Development Research Center of the State Council and the World Bank; Li, W.; Indrawati, S.M.; Liu, S.; Han, J.; Rohland, K.; Hofman, B.; Hou, Y.; Warwick, M.; Goh, C.; et al. China: Promote efficient, inclusive and sustainable urbanization. J. Manag. World 2014, 4, 5–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, K.; Chen, T.; Li, P. Progress and prospect of research on urban ecological space. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, R.; Mishra, V.; Qian, X. The environment and well-being in urban China. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 68, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, X.; Gu, X.; Liang, Y. Impact mechanism of ecosystem services on resident well-being under sustainable development goals: A case study of the Shanghai metropolitan area. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 103, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Chanduvi, J. Shared Prosperity: A New Goal for a Changing World. 2013. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/05/08/shared-prosperity-goal-for-changing-world (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- He, L.; Cao, Z.; Li, W. Research Progress on Shared Prosperity. Econ. Perspect. 2023, 10, 144–160. [Google Scholar]

- Vitikainen, A. An overview of land consolidation in Europe. Nord. J. Surv. Real Estate Res. 2004, 1, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.M.; Xu, C.C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in China: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgan, M.; Bavorova, M. How to increase landowners’ participation in land consolidation: Evidence from North Macedonia. Land Use Policy 2022, 123, 106424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sombati, J. Politické a právne aspekty reštitúcií pozemkového vlastníctva na Slovensku po roku 1989. Hist. Theor. Iuris 2019, 11, 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Peráček, T.; Srebalová, M.; Srebala, A. The Valuation of Land in Land Consolidation and Relevant Administrative Procedures in the Conditions of the Slovak Republic. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, D.; Stillwell, J.; See, L. Land consolidation in Cyprus: Why is an integrated planning and decision support system required? Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Fan, C.; Chai, D.; Zhang, Z.F. Evaluation for the Production Ability of Agricultural Land in Different Types of Agricultural Land Consolidation Area. J. Nat. Resour. 2013, 28, 745–753. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Gu, X. Effects of land consolidation in plains and hills on plots use. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2013, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Shen, D.; Gu, X.; Li, X.T.; Zhang, S.L. Comprehensive Land Consolidation and Multifunctional Cultivated Land in Metropolis: The Analysis Based on the “Situation-Structure-Implementation-Outcome”. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Ying, L.; Zhong, L. Thinking for the transformation of land consolidation and ecological restoration in the new era. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Rural vitalization in China: A perspective of land consolidation. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhong, L. Literature Analysis on Land Consolidation Research in China. China Land Sci. 2016, 30, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, F. Comprehensive land consolidation: Development background, system connotation and trend prospects. Zhejiang Land Resour. 2018, 10, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B. Marxist economic theory of social security and its reality. Contemp. Econ. Res. 1999, 4, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Qian, T.; Hwang, S.H.; Dong, X.B. The Connotation, Realization Path and Measurement Method of Common Prosperity for All. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zheng, H. The Evolution of the Western Social Welfare System and Its Revelation to China. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2013, 52, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. Social Control and State Governance Realized by Welfare State—Comparative Analysis and Theoretical Exploration based on the Practice of Britain Germany and America. Acad. Mon. 2022, 54, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J. The Dilemma and Evolution Trend of the Welfare System in the Nordic Countries and Its Enlightenment to China’s Common Prosperity. Shanghai J. Econ. 2023, 1, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Liang, J. Xi Stresses Promoting Common Prosperity Amid High-Quality Development, Forestalling Major Financial Risks. 2021. Available online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2021/0818/c90000-9885064.html (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Yang, Y.; Wang, M. The Road to Building a Common Prosperity Society; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022; ISBN 978-7-01-025026-7. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, J.; Wang, H. Research progress of the identification and optimization of production-living-ecological spaces. Prog. Geogr. 2020, 39, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lu, Y. Mechanism and optimization path of comprehensive land consolidation oriented urban-rural integration. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 2201–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokov, A.S.; Krasilnikova, V.S.; Cherkasova, O.V. Economic Valuation of Recovery and Increased Efficiency in Agricultural Land Use. Stud. Russ. Econ. Dev. 2022, 33, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Su, S. The path of comprehensive land consolidation under the goal of common prosperity. China Land 2021, 12, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W. Connotation, Logical System and Its Reflections of Production of Space on Chinese New Urbanization Practice. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wang, X.; Lin, B. The Analysis of Economic Dilemma Caused by the Township Government-led Rural Land Transfer after the Rural Land Comprehensive Consolidation—A Case of D-town. Chin. Public Adm. 2017, 9, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. Land Property Rights Reform and Rural Governance Order: An Analytical Framework of Agricultural Policy Change—Case Study Based on Z Village in Hubei Province. J. Public Manag. 2020, 17, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X. A Study of the Competitive Patterns Between Local Governments. Manag. World 2002, 12, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Z. From Town-country Integration to Urban-rural Integration: New Thinking on the Relationship Between Urban and Rural Areas. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2018, 38, 1624–1633. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Z.; Zhang, Q. Urban and rural element mobility and allocation optimization under the background of rural priority development. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, B.; Gu, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, G. Influencing Mechanism and Countermeasures of Rural Residential Land Redevelopment in Urban Suburbs: A Case Study on the Suburbs of Yangtze River Delta. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn, D.; Ignatenko, I. Protection of land ownership of foreigners in Ukraine. Jurid. Trib. J. Trib. Jurid. 2018, 8, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, F.; Tian, G. The Coordination Urban Growth between Rural Development, and the Reform of the System of the Property Right of the Rural Collective Land. J. Manag. World 2011, 6, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q. Multi-subject cooperative governance under social network structure. J. Zhengzhou Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 44, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, V. The Intellectual Crisis in American Public Administration; University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Long, H. The mechanism of land use transitions and optimization of territorial spatial development patterns: Analysis based on the spatial functions of land use benefits. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 2447–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Zou, J. Assessment of Rural Development Types and Their Rurality in Eastern Coastal China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2009, 64, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- HU, C. Establishing a Policy Tool for Liberalized Conveyance of Land Between Rural and Urban Sectors: Probe into a Tool of Land Exchange Property Certification. China Land Sci. 2009, 23, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhong, J. Market-Oriented Reform of Land Factor Allocation: Property Rights Foundation, Transfer Path and Revenue Distribution. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Di Lishati, X.F. The Implementation of the Rural Revitalization Strategy and the Deepening of the Reform of the “Three Rights Separation” of Rural Homesteads. Reform 2019, 1, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.Z.; Wang, J.Y. Land Consolidation in Rural China: Historical Stages, Typical Modes, and Improvement Paths. Land 2023, 12, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.F.; Long, H.L.; Tang, Y.T.; Deng, W.; Chen, K.; Zheng, Y. The impact of land consolidation on rural vitalization at village level: A case study of a Chinese village. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Lu, G.; Ren, Y. From Government Control to Farmers’ Participation: The Logic Conversion and Path Optimization of Rural Environmental Governance. Issues Agric. Econ. 2022, 8, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Research on the urban-rural integration and rural revitalization in the new era in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 637–650. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Xi, Y.; Zhong, L. Study on the Influence Factors of Farmers’ Willingness to Protect Cultivated Land. Areal Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Seia, C.A. Environmental Liability, Study for a Future Amendment of European Legislation. Persp. L. Pub. Admin. 2023, 12, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, X. Review on Studies on Production of Urban Space. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 31, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Hong, S.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Jin, F.; Li, P. County-level Urban-rural Integration from Edge Space to Innovation Space: A Case Study in the Science and Innovation Corridor in the West of Hangzhou City. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).