The Nature and Production of Urban Space in Latin America: A Historical Review of the Case of Ibagué (Colombia)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study: Ibagué (Colombia)

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

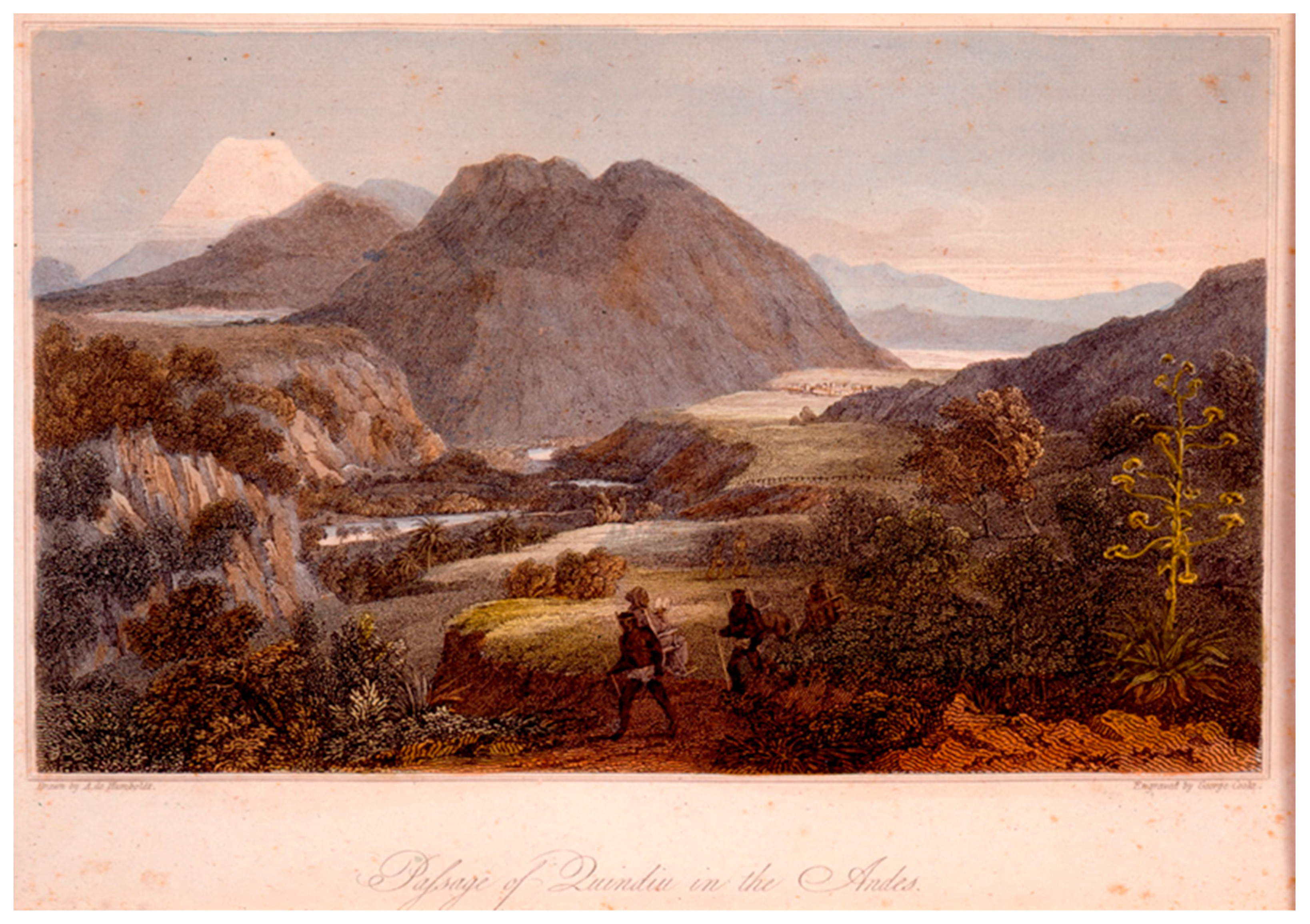

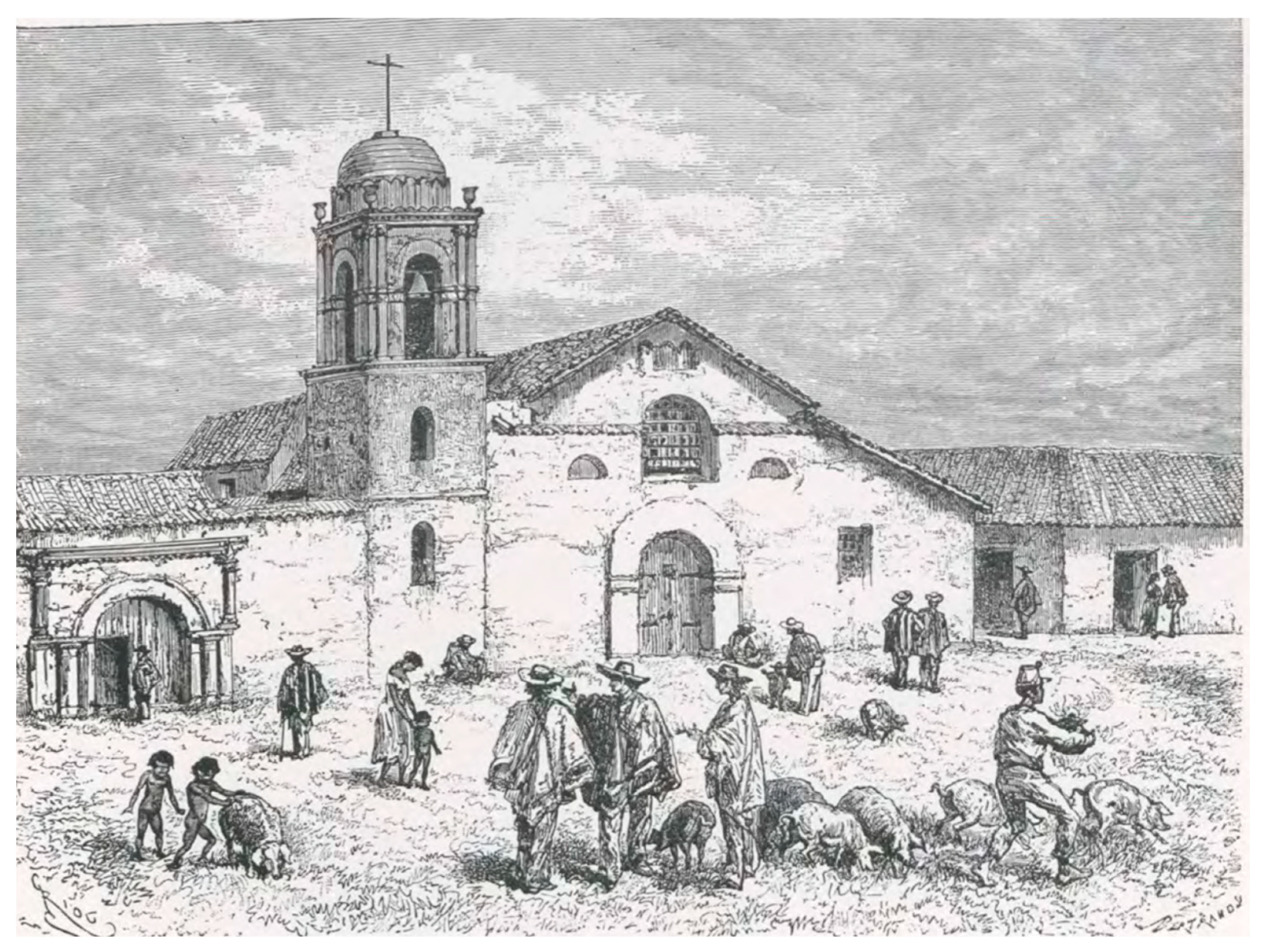

3.1. Nature as a Limit and Resource

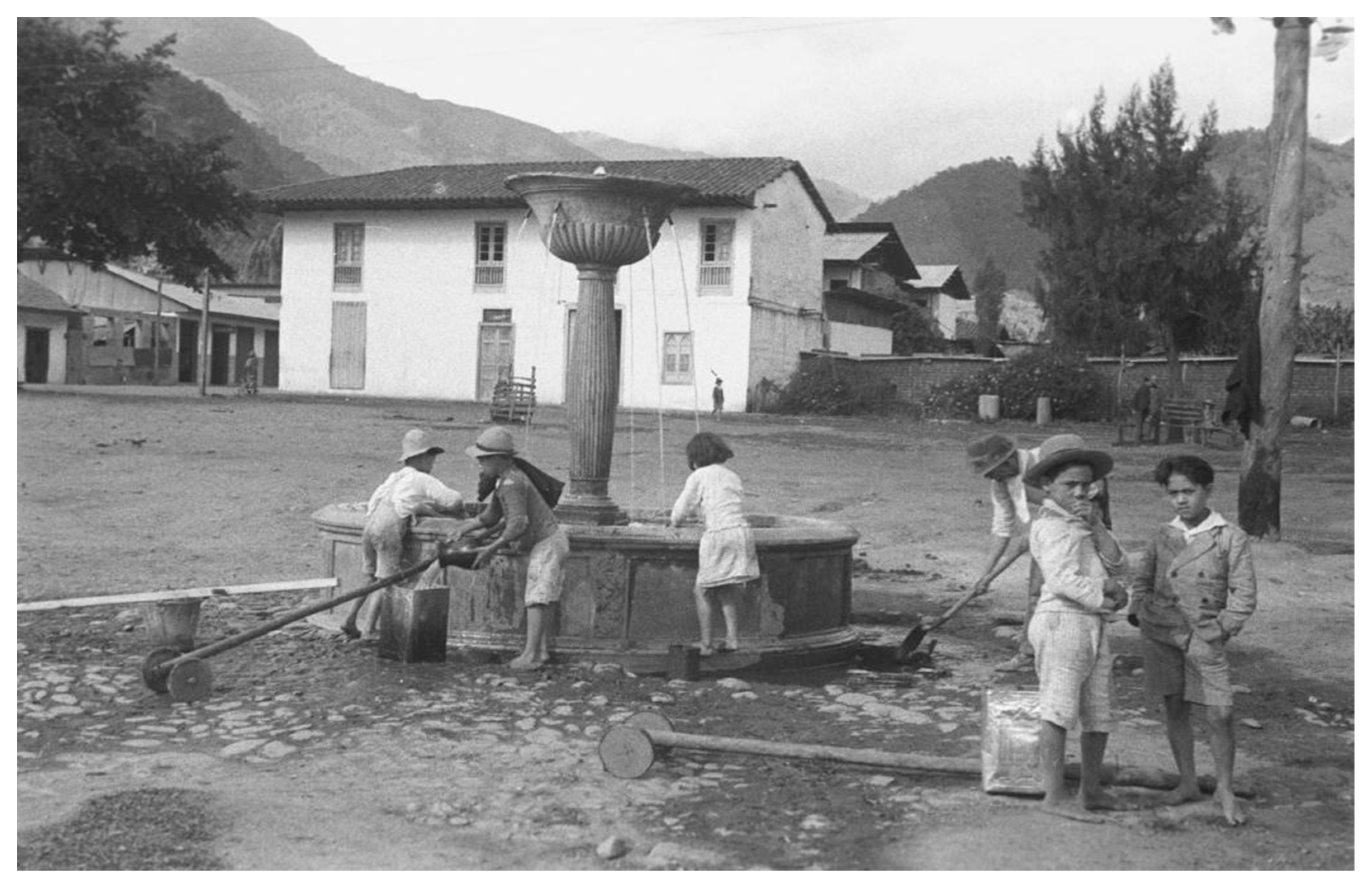

3.2. The Triumph of the City over Nature

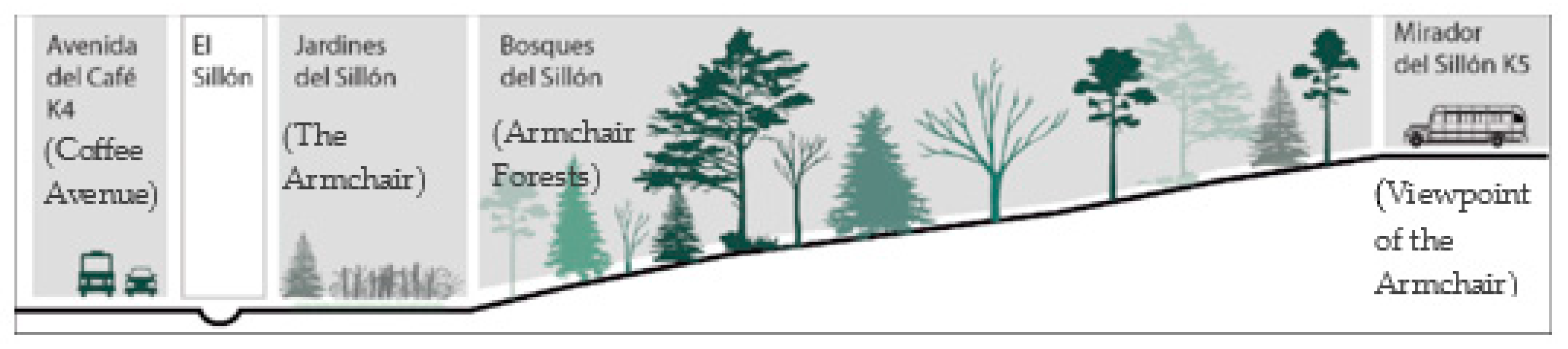

3.3. The Urban Edge as a Reference Point for Environmental Planning in the City

4. Discussion

The Redefinition of Urban–Rural Dynamics as a Return to Nature

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altamira y Crevea, R. Ordenanzas del Descubrimiento y población dadas por Felipe II en 1573; Jaus: Ciudad de México, México, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Francel, A. Historia y Patrimonio de la Periferia Interior de Ibagué; Casa de Libros: Ibagué, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, J.L. Latin America. Its Cities and Ideas; Azar, I., Ed.; Cultural Series 59; Interamer Collection: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Naredo, J.M. Diagnóstico Sobre la Sostenibilidad: La Especie Humana Como Patología Terrestre; Cuadernos de Crítica de la Cultura: Archipiélago, México, 2004; Volume 62, pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M. La Naturaleza del Espacio: Técnica y Tiempo; Razón y Emoción; Ariel Geografía: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. La Production de l’Espace; Anthropos: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.L. De la Ciudad al Territorio. La Configuración del Espacio Urbano en Ibagué: 1886–1986; Aquelarre: Ibagué, Colombia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- DANE. Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda; Dane: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braudel, F. History and the Social Sciences: The Longue Durée. Review 2009, 32, 171–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, C. What good is urban history. J. Urban Hist. 1996, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGAC. Cartografía Básica; IGAC: Bogotá, Colombia, 2022. Available online: https://glx-gov-esri-co.hub.arcgis.com/apps/22c21604d7654cf38116827da3e41701/explore (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- SINUPOT. Secretaría Distrital de Planeación. 2023. Available online: https://glx-gov-esri-co.hub.arcgis.com/ (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Da Costa, P.; Berdoulay, V. Imagens na geografia: Importância da dimensão visual no pensamento geográfico. Cuad. Geografía. Rev. Colomb. Geogr. 2018, 27, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdoulay, V.; Da Costa, P.; Maude, L.J. L’image dans l’écriture géographique: Enjeux épistémologiques et valeur heuristique. Géogr. Cult. 2015, 93, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, F. On Geography as a Visual Discipline. Antipode 2003, 35, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza de León, P.D. Crónica del Perú; Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú: Lima, Peru, 1994; Folio 4V. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, C. Apuntes Sobre el Urbanismo en el Nuevo Reino de Granada; Banco de la República: Bogotá, Colombia, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco Barros, J.A. Fundaciones coloniales y republicanas en Colombia: Normas, trazado y ritos fundacionales. Credencial Hist. 2001, 141, 17–32. Available online: https://www.banrepcultural.org/biblioteca-virtual/credencial-historia/numero-141/fundaciones-coloniales-y-republicanas-en-colombia (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango: Bogotá, Colombia, Fondo: AP2121.

- Foster, G. Culture and Conquest. America´s Spanish Heritage; Viking Fund Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Journal El Tolima, Ibagué, Colombia, 30 August 1888.

- Archivo de Memoria Visual; Biblioteca Darío Echandía: Ibagué, Colombia, 1922.

- Hardoy, J.E. La forma de las ciudades coloniales en la América española. In Estudios Sobre la Ciudad Iberoamericana; De Solano, F., Ed.; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1983; pp. 315–344. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, J. Ibagué Tierra Buena. Arte Órgano Conserv. 1935, 16, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- La Crónica, Ibagué, Colombia, 2 June 1933.

- La Hoja, Ibagué, Colombia, 14 October 1893.

- Saffray, C. Geografía Pintoresca de Colombia: La Nueva Granada Vista por dos Viajeros Franceses del Siglo XIX; Litografía Arco: Bogotá, Colombia, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- DANE. Censo Nacional. Colombia, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Sunkel, O. Introducción. La interacción entre los estilos de desarrollo y el medio ambiente en América Latina. In Estilos de Desarrollo y Medio Ambiente en América Latina; Sunkel, O., Gligo, N., Eds.; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de México, México, 1980; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, L. Técnica y Civilización; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Acta del Concejo Municipal, Número 166; Archivo Histórico de Ibagué (A.H.I.): Ibagué, Colombia, 1918.

- Francel, A.; Hormechea, P.; Uribe, C. Types of Land occupation in the urban periphery. Ibagué, Colombia, 1935. In Research Tracks in Urbanism: Dynamics, Planning and Desing in Contemporary Urban Territoires; Allegri, A., Benatti, A., Abascal, E., Sabaté, J., Costa, J.P., Schicchi, M., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Silva, C. Historia de la Forma Urbana de Ibagué; Alcaldía de Ibagué: Ibagué, Colombia, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Terraza, H.; Pons, B.; Soulier, G.M.; Juan, A. Desarrollo Gestión Urbana, Asociaciones Puúblico-Privadas y Captación de Plusvalías: El Caso de la Recuperación del Frente Costero del río Paraná en la Ciudad de Rosario, Bid. Nota Técnica # IDBMG-303. 2015. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/viewer/Gesti%C3%B3n-urbana-asociaciones-p%C3%BAblico-privadas-y-captaci%C3%B3n-de-plusval%C3%ADas-El-caso-de-la-recuperaci%C3%B3n-del-frente-costero-del-r%C3%ADo-Paran%C3%A1-en-la-Ciudad-de-Rosario-Argentina.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Espinoza, E. Ríos que Dan Vida: Las Ciudades Latinoamericanas Que se Transforman en Torno al Agua El País, Madrid. 2023. Available online: https://elpais.com/america-futura/2023-05-30/rios-que-dan-vida-las-ciudades-latinoamericanas-que-se-transforman-en-torno-al-agua.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Evaluation of the Costs and Benefits of Water and Sanitation Improvements at the Global Level; Citado por BID Nota Técnica # IDBMG-303, abril 2015; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mayorga, N. Experiencias de Parques Lineales en Brasil: Espacios Multifuncionales con Potencial para Brindar Alternativas a Problemas de Drenaje y Aguas Urbanas. BID, Nota Técnica # IDBTN-518. 2013. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/viewer/Experiencias-de-parques-lineales-en-Brasil-Espacios-multifuncionales-con-potencial-para-brindar-alternativas-a-problemas-de-drenaje-y-aguas-urbanas.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, Sección de Planeamiento urbano. Plan Piloto de Desarrollo Urbano de la Ciudad de Ibagué; Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi: Bogotá, Colombia, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaldía de Ibagué. Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial; Acuerdo 116; Alcaldía de Ibagué: Ibagué, Colombia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

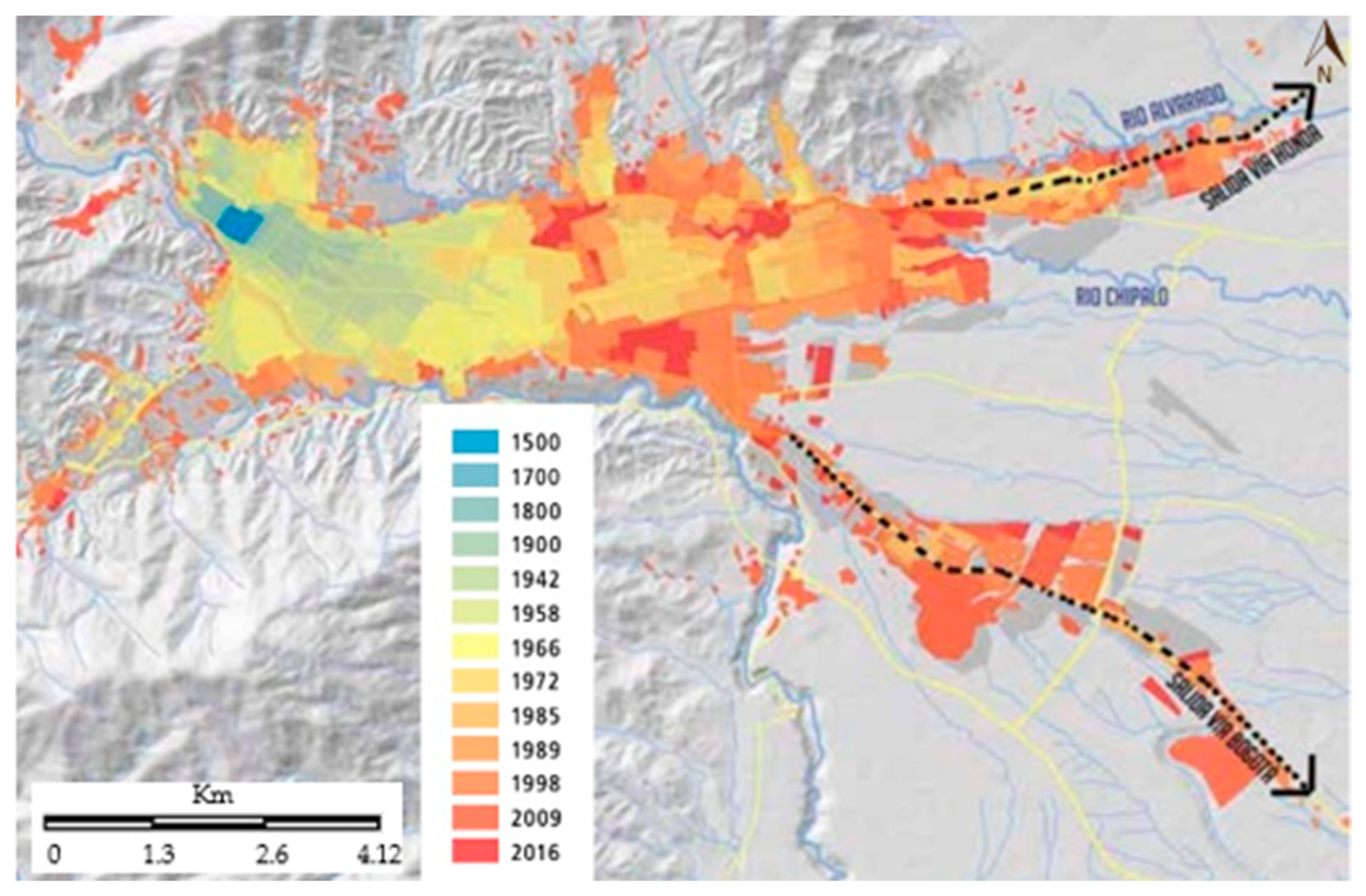

- IDOM, 64, 2016. Studies Base Module 3-Urban Growth. Modified. 2017.

- Capel, H. La definición de lo urbano. Estud. Geogr. 1975, 36, 265–301. [Google Scholar]

- Duby, G. Histoire de la France Urbaine: La Ville Clasique; Seuil: París, France, 1980; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cahya, D.L.; Martini, E.; Kasikoen, K.M. Urbanization and Land Use Changes in Peri-Urban Area using Spatial Analysis Methods (Case Study: Ciawi Urban Areas, Bogor Regency). In Proceedings of the 2nd Geoplanning-International Conference on Geomatics and Planning, Surakarta-Central Java, Indonesia, 9–10 August 2017; IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Volume 123. [Google Scholar]

- Samat, N.; Mahamud, M.; Tan, M.; Maghsoodi, M.; Tew, Y. Modelling Land Cover Changes in Peri-Urban Areas: A Case Study of George Town Conurbation, Malaysia. Land 2020, 9, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallent, N. The rural–urban fringe: A new priority for planning policy? Plan. Pract. Res. 2006, 21, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallent, N.; Shaw, D. Spatial planning, area action plans and the rural-urban fringe. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2007, 50, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A. Environmental planning and management of the peri-urban interface: Perspectives on an emerging field. Environ. Urban. 2003, 15, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravetz, J.; Fertner, C.; Nielsen, T.S. The dynamics of peri-urbanization. In Peri-Urban Futures: Scenarios and Models for Land Use Change in Europe; Nilsson, K., Pauleit, S., Bell, S., Aalbers, C., Nielsen, T.A.S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ruoso, L.E.; Plant, R. A politics of place framework for unravelling peri-urban conflict: An example of peri-urban Sydney, Australia. J. Urban Manag. 2018, 7, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanier, M. Qu’est-ce que le tiers espace? Territorialités complexes et construction politique. Rev. Géogr. Alp. 2000, 88, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlaund, S.; Yves, J.; Rouyoux, D. Rural-Urbain. Nouveaux Liens, Nouvelles Frontiéres; Press Universitaires de Rennes: Rennes, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M. El Animal Público; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Calle, J.L.; Sánchez Contreras, C.A.; Monteserín Abella, O. The Nature and Production of Urban Space in Latin America: A Historical Review of the Case of Ibagué (Colombia). Land 2023, 12, 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091807

González-Calle JL, Sánchez Contreras CA, Monteserín Abella O. The Nature and Production of Urban Space in Latin America: A Historical Review of the Case of Ibagué (Colombia). Land. 2023; 12(9):1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091807

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Calle, Jorge Luis, César Augusto Sánchez Contreras, and Obdulia Monteserín Abella. 2023. "The Nature and Production of Urban Space in Latin America: A Historical Review of the Case of Ibagué (Colombia)" Land 12, no. 9: 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091807

APA StyleGonzález-Calle, J. L., Sánchez Contreras, C. A., & Monteserín Abella, O. (2023). The Nature and Production of Urban Space in Latin America: A Historical Review of the Case of Ibagué (Colombia). Land, 12(9), 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091807