The Olive Grove Landscape as a Tourist Resource in Andalucía: Oleotourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

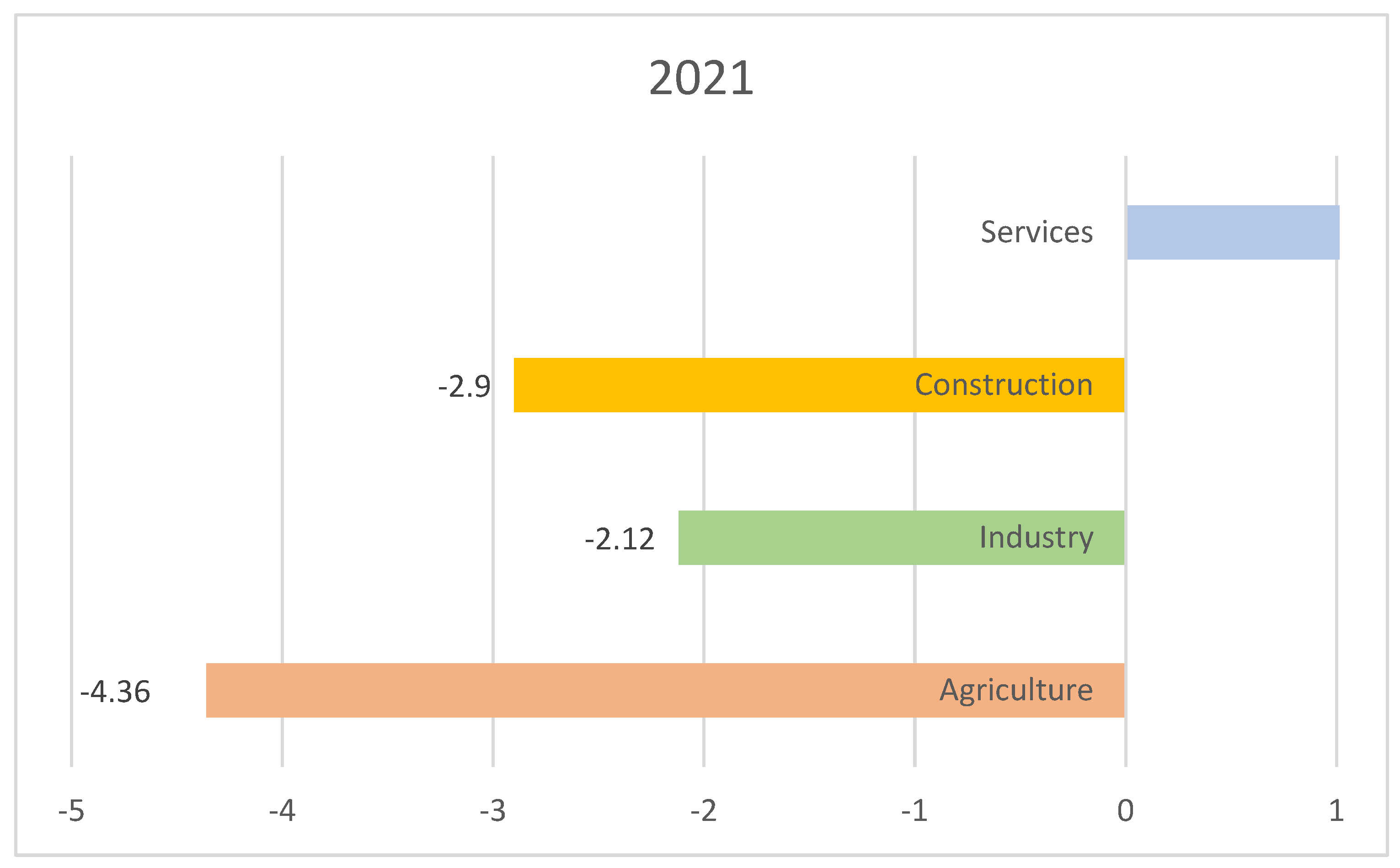

2. The Olive Grove Landscape in Andalucía and Tourist Activity

- Consolidate the role of tourism as a vehicle for sustainable development and the creation of stable, qualified, and high-quality employment for the Andalucían economy.

- Advance toward a new tourism management model whose fundamental pillars are environmental, economic, and social sustainability, particularly benefiting the inland towns where the average income per capita is very low. This includes creating new tourism offerings such as olive tourism that allow for additional income through this tourism activity and prevent the migration of young people from rural areas to cities.

- Guarantee a model of tourism development based on integration and excellence, as well as inclusive, accessible, and multigenerational tourism.

- Ensure greater coordination of tourism planning with similar tools of the Andalucían Regional Government and other national and international organizations.

- Optimize the profitability and competitiveness of the Andalucían tourism sector through excellent services and tourist destinations.

- Consolidate the competitive transformation of the Andalucían tourism industry, where innovation, continuous digital adaptation, and an emphasis on tourism intelligence constitute factors of competitiveness for our tourism sector.

- Promote the development of new strategies for academic and professional training and support for tourism entrepreneurs.

- Enhance strategies aimed at reducing the seasonality of tourism activity by creating products and developing segments that can be implemented throughout the year, contributing to territorial cohesion. Olive tourism with visits to the olive grove landscape would be included within this objective.

- Develop a marketing policy that promotes better commercialization of products and destinations, responds to the motivations of an increasingly diverse range of visitors, and highlights the unique characteristics of each territory under the umbrella of the Andalucía brand.

- Consolidate the regeneration of the Andalucían tourism sector, focusing on a safe and healthy destination.

- Ensure legal security in the practice of tourism activities.

- Increase the contribution of tourism to the Andalucían economy compared to pre-health crisis levels, improving tourist income by an average cumulative annual growth of 3%.

- Generate quality, stable, and equal employment in the Andalucían tourism sector, with a cumulative annual average growth of 2.5% in the number of employees. This seeks to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals 5 (gender equality) and 8 (decent work and economic growth).

- Optimize the process of continuous technological adaptation and transformation in the Andalucían tourism sector, especially in rural and inland areas.

- Contribute to a more homogeneous territorial and temporal distribution of tourist flows, reducing seasonality by at least 2% in the cumulative annual average rate.

- Promote and improve the comprehensive sustainability management of Andalucían tourist destinations. This includes achieving the goals of Affordable and Clean Energy (Goal 7), Clean Water and Sanitation (Goal 6), Responsible Production and Consumption (Goal 12), Climate Action (Goal 13), Life Below Water (Goal 14), and Life on Land (Goal 15).

- ▪

- Increase in erosive processes in the Mediterranean context—already notoriously affected by its geomorphology and irregular climatology—where both the wild olive groves (acebuchal) and cultivated olive groves play and should continue to play a significant role in supporting slopes and hillsides (Figure 3), instead of becoming promoters of gullies, loss of fertile soil, and desertification. Losses of nearly 90 tons per hectare per year have been documented, far exceeding any sustainable level of soil loss [42].

- ▪

3. The Olive Grove Landscape as a World Heritage Site Declaration

- ▪

- Four areas linked to the olive specialization of the 19th century: Campiñas de Jaén, Subbética Cordobesa, Sierra Mágina, and Hacienda de La Laguna—Alto Guadalquivir.

- ▪

- Three areas referring to the Enlightenment-era olive groves, represented by Montoro and its surroundings, and the Haciendas of Seville and Cadiz, associated with the 16th to 18th centuries.

- ▪

- An area related to the olive groves of the medieval-Islamic period in the Lecrín Valley (Granada).

- ▪

- The area of Valle del Segura linked to the olive groves of the 13th to 15th centuries.

- ▪

- The Astigi-Bajo Genil area (Écija) connected to the olive groves of the Roman period, from the 1st to the 3rd centuries.

- ▪

- The area of Periana and Alora in Malaga, representing the early cultivation practices of the olive tree.

- ⮚

- Aesthetic values: The capacity of a landscape to evoke a particular sense of beauty. Landscape values form an inseparable set with other cultural elements. In this case, it refers to olive grove areas or environments with outstanding visual beauty.

- ⮚

- Ecological values: Factors or elements that determine the quality of the natural environment. An olive grove is not composed solely of olive trees; it also encompasses associated resources such as soil, water, other plants, and the fauna that inhabit it. In this sense, olive cultivation stands out for its adaptation to the Mediterranean climate, its efficient water usage, and its occupation of generally unsuitable land for other crops, often constituting environmentally and aesthetically valuable areas that serve as refuges for unique flora and fauna.

- ⮚

- Productive values: The capacity of a landscape to generate economic benefits by transforming its elements into resources.

- ⮚

- Historical values: Olive groves preserve a centuries-old cultural legacy that reflects the most relevant imprints left by different civilizations on this landscape throughout history.

- ⮚

- Social use values: The utilization of a landscape by individuals or specific communities. Olive groves are agricultural landscapes that, unlike spaces shaped by nature (cliffs, ravines, escarpments) or intentionally designed by humans (parks and gardens), combine physical appearance and functionality in an indissoluble manner.

- ⮚

- Symbolic and identity values: The identification of a particular community with a landscape.

4. Materials and Methods

- A univariate descriptive analysis was conducted to determine the profile of oleotourists, with the objective of identifying if there are significant differences between tourists.

- A bivariate analysis was conducted using contingency tables to identify whether there is an association or independence between two variables, using the χ2 statistic (where H0 is that the analyzed variables are independent and H1 is that the analyzed variables are related). The aim of said analysis was to determine the associations between variables, thus allowing for the identification of the profiles of gastronomic tourists.

- A bivariate analysis was conducted using a test to compare means regarding some evaluations obtained before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

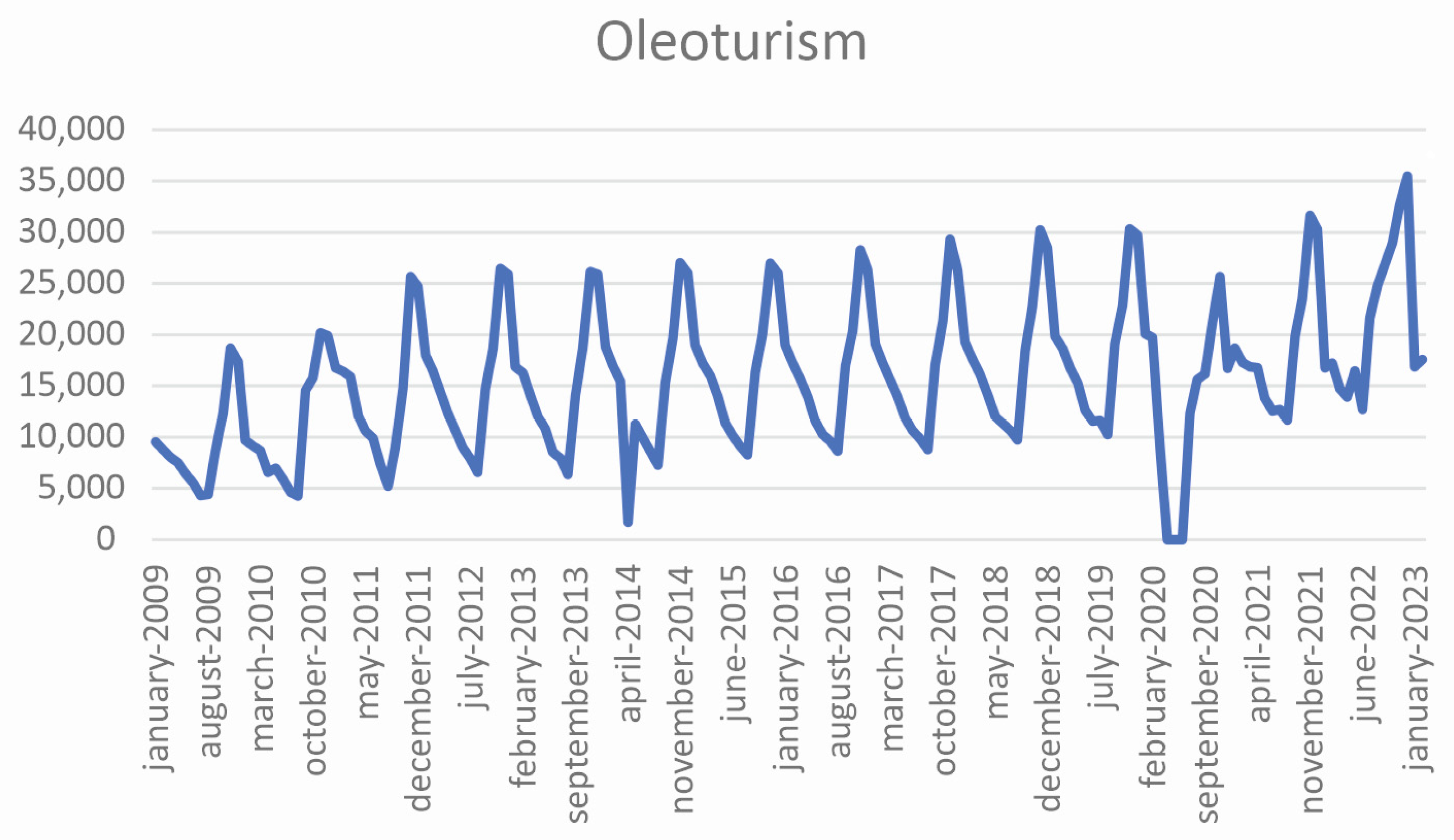

- A SARIMA (Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) model was applied to forecast the demand for oleotourism in the year 2023, aiming to understand the evolution of this tourism segment and identify its challenges and opportunities. The SARIMA model (used in previous studies of tourists, such as those by Lim [50] to predict tourist demand in Macao after the COVID-19 pandemic; Yang and Zhang [51] to predict the tourist demand in 29 Chinese regions; Petrevska [52] to predict the tourist demand in Macedonia; and Zhang [53] to predict tourist occupancy in a hotel) was used to predict the potential demand for oleotourism in Andalucía based on a sample (170 observations) collected from January 2009 to February 2023. SARIMA models, popularly known as the Box–Jenkins (BJ) methodology, analyze the probabilistic, or stochastic, properties of economic time series themselves [54]. In this case, this was the number of oleotourists in Andalucía.

5. Results

5.1. Univariate Descriptive Analysis

5.2. Bivariate Analysis

5.3. Comparison of Means Test

5.4. SARIMA Demand Estimation Model

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calatrava, J.; Sayadi, S. Análisis Funcional de Los Sistemas Agrarios Para el Desarrollo Rural Sostenible: Las Funciones Productiva, Recreativa y Estética de la Agricultura en la Alta Alpujarra; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, Centro de Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2001.

- Consejo de Europa. Convenio Europeo del Paisaje; Consejo de Europa: Florencia, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, J. El Patrimonio Territorial como recurso cultural y económico. Rev. Ciudad. 1998, 4, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, M.G.; Amador, L.; Arjona, J.M. El oleoturismo: Una alternativa para preservar los paisajes del olivar y promover el desarrollo rural y regional de Andalucía (España). Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2015, 60, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larondelle, N.; Haase, D. Valuing post-mining landscapes using an ecosystem services approach—An example from Germany. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassianidou, V. Mining landscapes of prehistoric Cyprus. Metalla 2013, 20, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorn, C.; Wesselingh, F.P.; ter Steege, H.; Bermudez, M.A.; Mora, A.; Sevink, J.; Sanmartín, I.; Sanchez-Meseguer, A.; Anderson, C.L.; Figueiredo, J.P.; et al. Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science 2010, 330, 927–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildanhrand, A. Creación, conservación y gestión del paisaje un elemento clave para el desarrollo rural en Andalucía. Rev. Estud. Andal. 1993, 19, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G. Cultural landscapes. In The Conservation Challenge in a Changing Europe; Institute for European Environmental Policy: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1996; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, M.; De Aranzabal, I.; Aguilera, P.; Rescia, A.; Pineda, F. Relationship between landscape typology and socioeconomic structure. Scenarios of change in Spanish cultural landscapes. Ecol. Model. 2003, 168, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slámová, M.; Belčáková, I. The role of small farm activities for the sustainable management of agricultural landscapes: Case studies from Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladro-Prieto, J.M.; García-Casasola, M.; Castellano-Bravo, B.; Ostos-Prieto, F.J.; Ponce Ortiz de Insagurbe, M. Lo agrícola, lo defensivo y lo antropológico: Claves culturales para una gestión sostenible del patrimonio en el contexto rural. Archit. City Environ. 2022, 17, 11381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Palomino, M. Transformaciones del bosque El Olivar: La ruta hacia la conservación del paisaje. Limaq Rev. Arquit. Univ. Lima 2021, 7, 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- Renes, H.; Centeri, C.; Kruse, A.; Kučera, Z. The future of traditional landscapes: Discussions and visions. Land 2019, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, B.; Ojeda, J.F.; Infante, J.; Andreu, C. Los olivares andaluces y sus paisajes distintivos del mundo mediterráneo. Rev. Estud. Reg. 2013, 96, 267–291. [Google Scholar]

- López, M.P. La fase romana en Arastipi (Cauche el Viejo, Antequera): El molino de aceite. Mainake 1995, 17, 125–170. [Google Scholar]

- Laurens, L. L’olivier, un arbre symbolique de la Méditerranée au service de la multifonctionnalité des espaces périurbains: Le cas de la France. In La Multifonctionnalité de L’agriculture et des Territoires Ruraux; Jean, B., Lafontaine, D., Eds.; Le CRDT: Chicoutimi, QC, Canada, 2006; pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Rojo, M. The role of ecosystem services in the design of agroecological transitions in Spain. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 61, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterchuk, Y.; Prokopchuk, O.; Tsymbalyuk, Y.; Rolinskyi, O.; Bilan, Y. Current status and prospects of development of the system of agrarian insurance in Ukraine. Investig. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2018, 15, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahorka, M. Formation of the ecological-economical management of ecologization of agrarian production. Agric. Resour. Econ. Int. Sci. E-J. 2019, 5, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Casabianca, F. Qualité et valorisation des produits régionaux dans le développement des zones marginalisées. In Proceedings of the Rencontre Internationale sur le Développement des Zones Défavorisées Méditerranéennes, Fes-Sefrou, Morocco, 1–4 November 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Guillou, M. La qualité, Instrument de Politique Agricole? Qualité et systémes agraire. In Techniques, Lieux, Acteurs. Etudes et Récherches sur les Systémes Agraires et le Développement n° 28; INRA: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economic of Natural Resource and the Environment; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1989; p. 392. [Google Scholar]

- Palacín, P.C.; Miqueleiz, E.U.; Micaló, P.R. Valor Económico Total de un espacio de interés natural. La dehesa del área de Monfragiüe. In Gestión de Espacios Naturales; Azqueta, D., Pérez, L., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 1996; pp. 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.; Nicholls, I. Ecología: Única esperanza para la soberanía alimentaria y la resiliencia socioecologica. Agroecología 2012, 7, 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Puerta, F. Extensión Agraria y Desarrollo Rural; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 1996; pp. 1–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ayhan, Ç.K.; Taşlı, T.C.; Özkök, F.; Tatlı, H. Land use suitability analysis of rural tourism activities: Yenice, Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103949. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Chen, M.H.; Su, C.H.J.; Zhi, Y.; Xi, J. Effects of rural revitalization on rural tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Sustainable development and rural tourism in depopulated areas. Land 2021, 10, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dašić, D.; Živković, D.; Vujić, T. Rural tourism in development function of rural areas in Serbia. Econ. Agric. 2020, 67, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Uribe-Toril, J.; de Pablo Valenciano, J.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C. Rural tourism and development: Evolution in scientific literature and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 1322–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero-Sosa, A.; Sánchez-Cubo, F.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J. Environmental Sustainability in Andalusian Rural Accommodation: Perceptions by Gender. Can. Soc. Sci. 2022, 18, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, A.D.; Northcote, J. The development of olive tourism in Western Australia: A case study of an emerging tourism industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, I. Olive oil as a tourist resource: Conceptual boundaries. Olivae 2011, 115, 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, M.G.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Amador-Hidalgo, L. Olive oil tourism: Promoting rural development in Andalusia (Spain). Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 21, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Potential of olive oil tourism in promoting local quality food products: A case study of the region of Extremadura, Spain. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cava Jimenez, J.A.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G.; Dancausa Millán, M.G. Factors that characterize oleotourists in the province of Córdoba. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz, E.; Caballero-Galeote, L. Recovery Measures for the Tourism Industry in Andalusia: Residents as Tourist Consumers. Economies 2022, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Estadistica y Cartografía de Andalucía. 2023. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/temas/est/tema_turismo.htm (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. 2023. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/ (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Vanwalleghem, T.; Infante-Amate, J.; González de Molina, M.; Soto, D.; Gómez, J.A. Quantifying the effect of historical soil management on soil erosion rates in Mediterranean olive orchards. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 142, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Cobo, J.M.; Klemming, J.M.; Romero, C.; Torres, M.J.R. Análisis cualitativo y cuantitativo de las comunidades de aves en cuatro tipos de olivares en Jaén (I) comunidades primaverales. Bol. Sanid. Veg. Plagas 2001, 27, 259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Foraster, L. Transición Agroecológica del Olivar. Estudio de Caso. Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad Internacional de Andalucía, Sevilla, Spain, 1 February 2016. Available online: https://dspace.unia.es/handle/10334/6265 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Ojeda-Rivera, J.F.; Andreu-Lara, C.; Infante-Amate, J. Razones y recelos de un reconocimiento patrimonial: Los paisajes del olivar andaluz. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2018, 79, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, J.R.; Zoido, F. El olivar andaluz en su dimensión paisajística. Espacio vivido y paisaje sentido. In Andalucía, el Olivar; Izquierdo, J.M., Ed.; Editorial Juan Ramón Guillén: Sevilla, Spain, 2013; Volume 3, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Andalucía Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca, Agua y Desarrollo Rural. 2023. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/agriculturapescaaguaydesarrollorural.html (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Sánchez, J.D.; Gallego, V.J.; Araque, E. Agrarian policies, productive systems and new olive grove landscapes in Andalusia. In New Ruralities and Sustainable Use of Territory; Frutos, L.M., Ed.; Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2009; pp. 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Millán-Vázquez, G.; Pablo-Romero, M.; Sánchez Rivas, J. Oleotourism as a Sustainable Product: An Analysis of Its Demand in the South of Spain (Andalusia). Sustainability 2018, 10, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M.; To, W.M. The economic impact of a global pandemic on the tourism economy: The case of COVID-19 and Macao’s destination-and gambling-dependent economy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. Spatial-temporal forecasting of tourism demand. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrevska, B. Predicting tourism demand by ARIMA models. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2017, 30, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Pan, B.; Zhang, G. Weekly hotel occupancy forecasting of a tourism destination. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control, 5th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–712. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Casado-Montilla, J.; Carrillo-Hidalgo, I. Análisis del comportamiento de la demanda de oleoturismo desde la perspectiva de la oferta. Investig. Tur. 2021, 21, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazón, T.; Hurtado, J.A.; Colmenares, M. El turismo gastronómico en la Península Ibérica: El caso de Benidorm, España. Iberóforum Rev. Cienc. Soc. Univ. Iberoam. 2014, 9, 73–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Casado-Montilla, J.; Carrillo-Hidalgo, I.; de la Cruz Pulido-Fernández, M. Evaluating olive oil tourism experiences based on the segmentation of demand. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caamaño-Franco, I.; Pérez-García, A.; Martínez-Iglesias, S. Enogastronomic tourism as a travel motivation in Rías Baixas (Pontevedra, Spain). J. Tour. Herit. Res. 2020, 3, 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dancausa, M.G.; Millán, M.G. Quality Food Products as a Tourist Attraction in the Province of Córdoba (Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dansac, Y.; González, L. Voices about the impact of tourism on the Agave Landscape: Comparisons between Tequila and Teuchitlan, Mexico. Int. J. Tour. Anthropol. 2014, 3, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancausa, M.G.; Millan, M.G.; Huete-Alcocer, N. Olive oil as a gourmet ingredient in contemporary cuisine. A gastronomic tourism proposal. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 29, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, P.; Larcher, F. Integrity in UNESCO World Heritage Sites. A comparative study for rural landscapes. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Capano, G.; Toivonen, T.; Soutullo, A.; Fernández, A.; Dimitriadis, C.; Garibotto-Carton, G.; Di Minin, E. Exploring landowners’ perceptions, motivations and needs for voluntary conservation in a cultural landscape. People Nat. 2020, 2, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, A.; Marano-Marcolini, C.; Čehić, A.; Tregua, M. Oleotourism: A comparison of three mediterranean countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Paddison, B. El oleoturismo en los mercados internacionales. In En Cultura, Património e Turismo na Sociedade Digital; Piñeiro-Naval, V., Serra, P., Eds.; Editora LabCom: Covilhã, Portugal, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 129–153. [Google Scholar]

| Region | Surface Area of Olive Grove (Hectares) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Andalucía | 1,673,071 | 60.38 |

| Aragón | 60,332 | 2.18 |

| Balearic Islands | 9126 | 0.33 |

| Canary Islands | 435 | 0.016 |

| Castilla León | 6986 | 0.252 |

| Castilla la Mancha | 449,387 | 16.22 |

| Catalonia | 114,350 | 4.127 |

| Valencian Community | 95,695 | 3.454 |

| Extremadura | 288,692 | 10.426 |

| Galicia | 52 | 0.002 |

| Madrid Community | 29,621 | 1.069 |

| Region of Murcia | 29,032 | 1.048 |

| Navarre Community | 9922 | 0.358 |

| Basque Country | 322 | 0.013 |

| La Rioja | 3475 | 0.125 |

| Total | 2,770,498 | 100 |

| Andalucía | Area (Hectares) | Olive Oil Production | Variation from Previous Campaign | Organic Olive Oil Production | Variation from Previous Campaign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almería | 22,026 | 10,000 | −25.7 | 300 | −55.5 |

| Cádiz | 30,845 | 9000 | −19.2 | 200 | −34.8 |

| Córdoba | 371,134 | 158,000 | −47.3 | 8000 | −44.8 |

| Granada | 206,694 | 70,000 | −41.4 | 1000 | −45.7 |

| Huelva | 35,749 | 10,000 | −18.5 | 3100 | −18.4 |

| Jaén | 588,252 | 200,000 | −60 | 1200 | −46.8 |

| Málaga | 141,405 | 40,000 | −30.4 | 400 | −31.4 |

| Seville | 242,215 | 90,000 | −35.2 | 2500 | −48.7 |

| Total | 1,638,320 | 587,000 | −49.1 | 16,700 | −42 |

| Demand Survey | |

|---|---|

| Population | Tourists over 18 years of age who visited an olive oil route/PDO route in Andalucía |

| Sample size | 416 |

| Sampling error | ±4.2% |

| Confidence level | 95%; p = q = 0.5 |

| Date of fieldwork | March 2022 to October 2022 |

| Characteristics | Percentajes Study 2017 (564 Surveys) | Percentajes Study 2019 Pre-COVID-19 (630 Surveys) | Percentajes Study 2022 Post-COVID-19 (416 Surveys) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female Male | 43.3 56.7 | 42.3 57.7 | 42.8 57.2 | |

| Age | Between 18 and 29 years Between 30 and 39 years Between 40 and 49 years Between 50 and 59 years More than 60 years | 17.4 25.6 22.3 15.8 18.9 | 14.4 27.3 19.7 30.5 8.1 | 16.1 26.0 15.6 33.4 8.9 | |

| Level of studies | No competed studies Primary education Secondary/VET studies High level | 1.3 25.2 59.3 14.2 | 9.5 20.5 42.0 28.0 | 8.2 18.3 46.9 26.7 | |

| Personal data | Marital status | Single Married Divorced/separated Other | 27.1 51.4 21.4 0.1 | 27.3 47.3 25.2 0.2 | 27.6 47.4 24.8 0.2 |

| Provenance | Andalucía Rest of Spain Rest of European Union Rest of world | 48.9 42.3 6.8 2.0 | 59.4 29.8 10.2 0.5 | 59.1 29.6 10.3 0.7 | |

| Income | Less than EUR 1000 EUR 1001–1500 EUR 1501–2000 EUR 2001–2500 More than EUR 2500 | 37.6 12.6 17.4 14.2 18.2 | 19.8 20.0 30.0 20.0 10.2 | 19.5 19.7 29.8 20.7 10.3 | |

| Number of days | Less than 24 h Between 2 and 3 days More than 3 days | 62.7 29.1 8.2 | 54.2 33.3 12.5 | 56.5 36.1 7.5 | |

| Average daily expenses | Less than EUR 30 Between EUR 30 and 65 Between EUR 66 and 100 More than EUR 100 | 27.2 30.5 27.6 14.7 | 11.1 23.9 43.9 21.1 | 13.9 20.9 44.0 21.2 | |

| Itinerary | Individual accompanying | Alone Accompanied my partner Family Friends | 17.9 24.8 15.3 42.0 | 2.0 49.4 38.4 10.2 | 2.0 47.8 10.1 35.8 |

| Motivation | Oil mill visits Culinary tradition region Food festivals | 53.7 36.4 9.9 | 50.2 39.7 10.1 | 40.1 49.5 10.3 | |

| Satisfaction with the destination | Satisfied Indifferent Not satisfied | 83.2 10.7 6.1 | 98.3 1.1 0.6 | 95.4 3.1 1.4 | |

| χ2 | Degrees of Freedom | Prob | Accepted Hypothesis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender–satisfaction | 17.896 | 2 | 0.00013 * | H1 |

| Age–satisfaction | 24.3521 | 8 | 0.002 * | H1 |

| Income level–satisfaction | 11.4203 | 8 | 0.179 | H0 |

| Motivation–satisfaction | 37.2498 | 4 | <0.00001 * | H1 |

| Educational level–satisfaction Knowledge of olive oil–olive oil use | 7.42219 24.7176 | 6 9 | 0.28356 0.0033 | H0 H1 |

| Variable | Statistic | Prob | Accepted Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income Age Average Expense Days | t = −0.2278 t = −0.0157 t = 0.5360 t = 1.2775 | 0.8198 0.8753 0.5360 0.2017 | H0: µ1 = µ2 H0: µ1 = µ2 H0: µ1 = µ2 H0: µ1 = µ2 |

| Dependent Variable: D(OLEOTURISM^0.2,1,12) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method: Least Squares | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| AR(12) | −0.532820 | 0.070640 | −7.542716 | 0.0000 |

| Null Hypothesis: OLEOTURISM Has a Unit Root | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exogenous: Constant | ||||

| Lag Length: 12 (automatic—based on SIC, maxlag = 13) | ||||

| t-Statistic | Prob. * | |||

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller test statistic | −1.599346 | 0.4805 | ||

| Test critical values: | 1% level | −3.472259 | ||

| 5% level | −2.879846 | |||

| 10% level | −2.576610 | |||

| Heteroskedasticity Test: ARCH | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| F-statistic | 0.032529 | Prob. F(1,142) | 0.8571 |

| Obs * R-squared | 0.032980 | Prob. Chi-Square(1) | 0.8559 |

| Year 2017 | Year 2024 | |

|---|---|---|

| February | 17,245 | 17,489 |

| March | 15,538 | 16,725 |

| April | 13,956 | 14,983 |

| May | 11,864 | 12,762 |

| June | 10,635 | 16,475 |

| July | 9846 | 13,984 |

| August | 8764 | 25,435 |

| September | 17,023 | 26,978 |

| October | 21,269 | 29,102 |

| November | 29,325 | 33,675 |

| December | 26,245 | 38,469 |

| Total | 200,761 | 246,077 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dancausa Millán, M.G.; Sanchez-Rivas García, J.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M.G. The Olive Grove Landscape as a Tourist Resource in Andalucía: Oleotourism. Land 2023, 12, 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081507

Dancausa Millán MG, Sanchez-Rivas García J, Millán Vázquez de la Torre MG. The Olive Grove Landscape as a Tourist Resource in Andalucía: Oleotourism. Land. 2023; 12(8):1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081507

Chicago/Turabian StyleDancausa Millán, Mª Genoveva, Javier Sanchez-Rivas García, and Mª Genoveva Millán Vázquez de la Torre. 2023. "The Olive Grove Landscape as a Tourist Resource in Andalucía: Oleotourism" Land 12, no. 8: 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081507

APA StyleDancausa Millán, M. G., Sanchez-Rivas García, J., & Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M. G. (2023). The Olive Grove Landscape as a Tourist Resource in Andalucía: Oleotourism. Land, 12(8), 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081507