Spatial Analysis of Sustainability Measures from Agritourism in Iberian Cross-Border Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Questionnaire Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Sampling

Profile of Respondents

2.5. Data Analisys

- to examine the drivers of agritourism clusters to try to understand what place-based features are associated with their creation [42];

- to determine hotspots of agritourism and direct sales to consumers in the United States [43];

- to create an indicator of the localization intensity of agritourism farms and explore their spatial distribution at the municipality level [44]; and

- to determine the online reputations of rural accommodation establishments located in the Autonomous Region of Extremadura by means of an analysis of the opinions recorded by rural tourists on various web portals [45].

2.6. Sustainable Indicators

2.7. The Context of the Case Study

3. Results

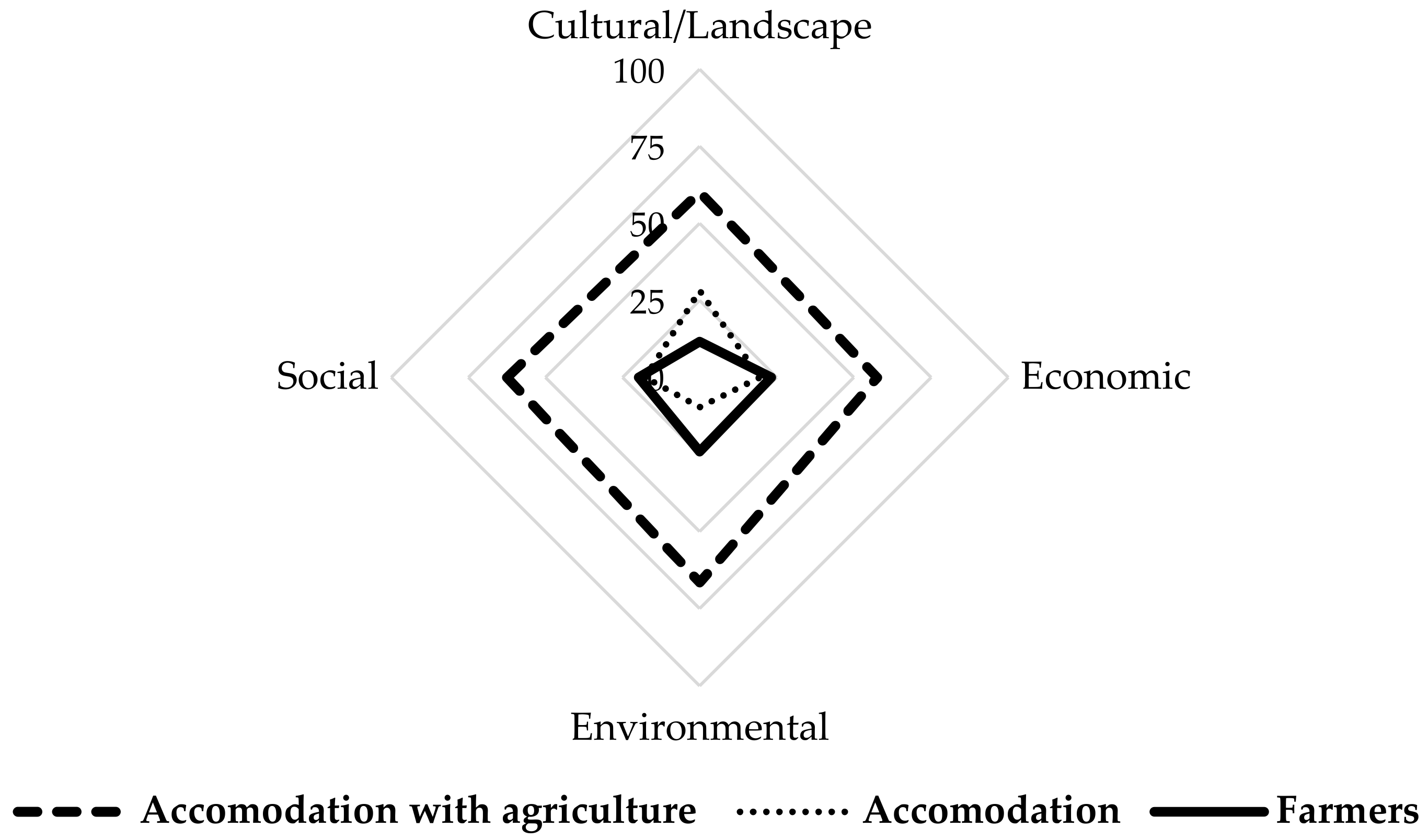

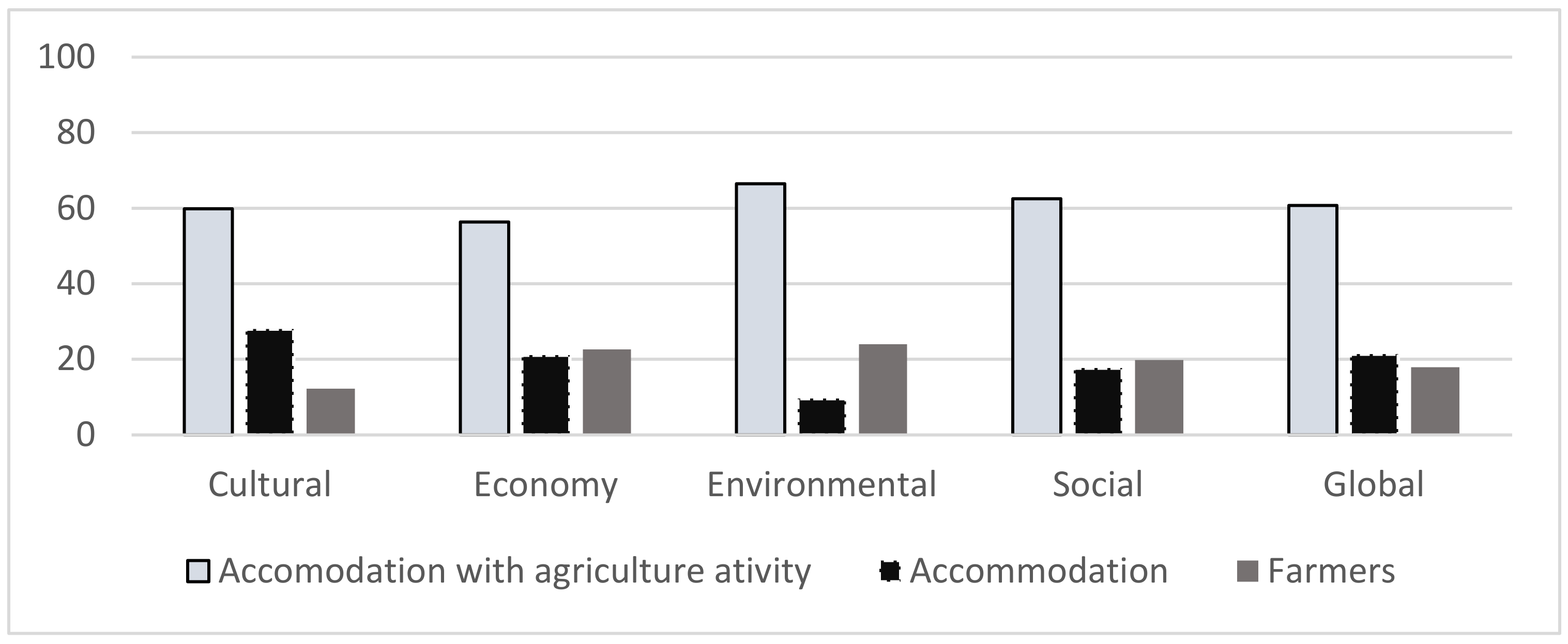

3.1. Agritourism Sustainability Patterns and Dynamics

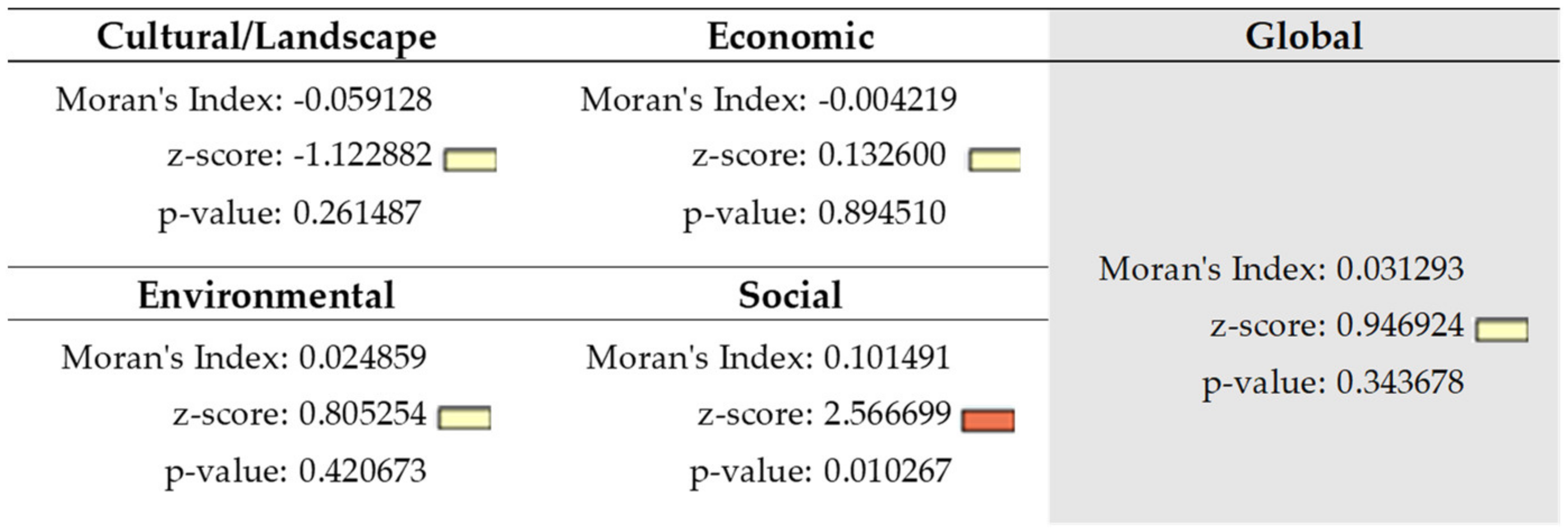

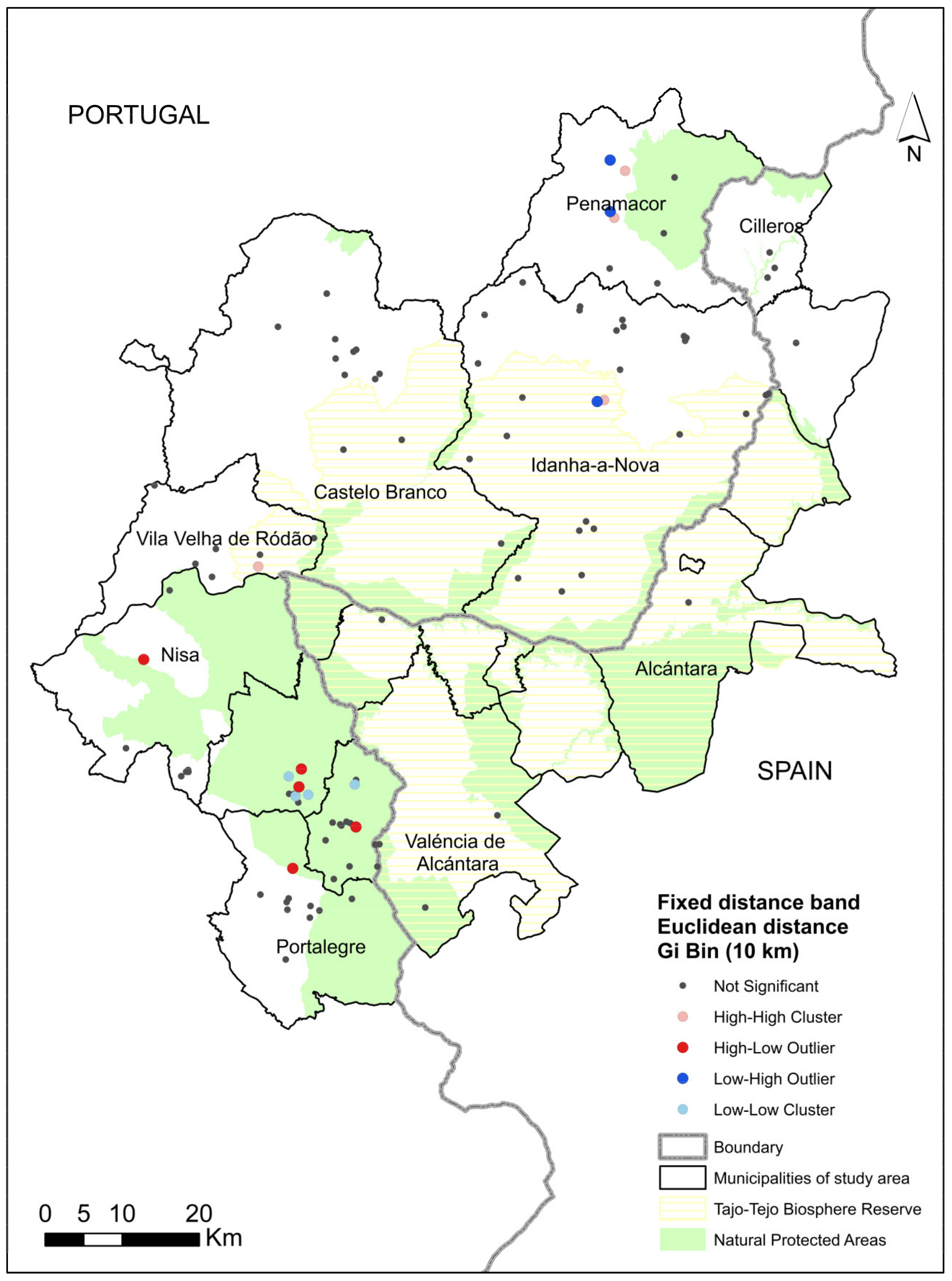

3.2. Spatial Analisys

4. Discussion

Limitations and Recommendations of the Study

- Strengthen business models that value local products and rural traditions in tourist programs, particularly in depressed territories.

- Support local initiatives to link tourism and agriculture, communicating existing initiatives in a structured way.

- Value the ecosystem services that result from the links between tourism and agriculture, which are particularly visible in actions that contribute to the preservation of the landscape’s cultural value.

- A sustainable development strategy must have consistent intentions and practices. In this regard, support for extensive and sustainable agriculture is recommended, as well as halting intensive production, as observed in the last two years.

- The role of agriculture in the dynamics of tourism should be valued, in terms of its links with agri-food production, traditional knowledge, or the diversification of differentiated tourist services.

- Strengthening supply chain proximity is critical if tourism and agriculture are to mutually benefit from demand from low-density destinations.

- Promoting and supporting local networks between farmers and accommodation managers are crucial to guaranteeing local consumption and encouraging initiatives that promote direct contact with farmers, local products, and local knowledge.

- Building on the last point, the methodology used here revealed the urgent need for collaborative networks between tourism and agriculture, as these would provide the opportunity to develop this destination.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type | Factor | Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Section A | General profile of the accommodation | |

| Main characteristics | Type of accommodation | Only one option: rural hotel; local accommodation; agritourism; rural accommodation; country houses |

| Year | Numeric | |

| Location | Single choice: rural/urban area; small towns; natural areas; agricultural operation | |

| Elements of the landscape | Multiple answers: olive grove; orchard; vineyard; pasture/montado (agro–silvo–pastoral system) | |

| Main infrastructure | Multiple answers: stone wall; local varieties; pastures; rural roads and single trails; beehives; traditional oven; mills; gardens; vernacular architecture; other | |

| No. of beds | Numeric | |

| Main services/activities | Multiple responses: swimming pool; bicycle; garden; kitchen access; meals on request; breakfast included in price; tour guide; advantages of access to local/regional cultural infrastructures; experience and tour packages | |

| Section B | Agricultural activity | |

| Main agri-food products | Crops and agricultural products | Descriptive |

| Processed products | Descriptive | |

| Animal husbandry | Descriptive | |

| Agri-food production system | Multiple answers: rainfed; irrigated; intensive; extensive; traditional; precision | |

| Natural hazard mitigation and risk reduction measures | Multiple answers: fire prevention; wastewater treatment; soil erosion prevention, other | |

| Biodiversity promotion measures | Multiple responses: control of invasive species; reforestation of native species; environmental education plan | |

| Measures to promote the circular economy | Multiple responses: organic waste for animal feed; water/electricity reuse system; other | |

| Trademarks | Likert: from 1 (low) to 5 (high) | |

| Main motivations for investing in agriculture | Multiple responses: invest and recover equity; diversify sources of business financing; add value to the lodging business; reduce the environmental impact associated with the production and transportation of food and raw materials; develop the farm-to-table circuit | |

| Income from activities | Numeric | |

| Quality certification | Multiple answers: PDO, PGI, organic farming, other | |

| Section C | Supply of food products | |

| Own production for self-consumption | Descriptive | |

| Local supply chains | Descriptive | |

| Section D | Sale of local products | |

| Own store | Dummy = 1 if yes; dummy = 0 if no | |

| Can sell products after the experience | Dummy = 1 if yes; dummy = 0 if no | |

| Section E | Restaurant | |

| Own restaurant | Dummy = 1 if yes; dummy = 0 if no | |

| Main courses | Descriptive | |

| Own products for self-consumption | Descriptive | |

| Local supply chains | Descriptive | |

| Section F | Agritourism | |

| Activities available | Dummy = 1 if yes; dummy = 0 if no | |

| Intention to offer activities | Dummy = 1 if yes; dummy = 0 if no | |

| Channels used to promote agritourism | Descriptive | |

| Price | Numeric | |

| Associations for the organization of agritourism activities | Descriptive | |

| Main objective | Multiple responses: general public; local residents; guests; students; other; other | |

General opinion:

| Likert: 1—Strongly Disagree, 9—Strongly Agree | |

| Main tourist attraction | One choice: nature/landscape; quiet/peace; local people; heritage/cultural offering; food/wine; local traditions; welcoming/hospitality | |

Advantages of linking agriculture and tourism:

| Multiple answers (three most important, ordered by relevance) | |

| Section G | Associations | |

| Partners and objectives | Who are the partners | Multiple answers: farmers; artisans; municipalities; public entities; tour operators; other |

| Main objectives | Multiple answers: housing promotion. promoting own agri-food products; organizing tourism activities; organizing experiential programs promoted by the network; organizing educational/environmental awareness programs; selling products to specific markets; participating in competitive trade networks; not applicable to my situation. | |

| Partnerships with local restaurants | Dummy = 1 if yes; dummy = 0 if no | |

| Main objectives | Multiple answers: sell products; recommend a reliable service; support local gastronomy; strengthen the local economy; create customized experience packages. Meal delivery at lodging; does not apply to my situation. | |

| Section H | General Profile | |

| Company and respondent profile | Quality certification | Multiple responses: biosphere; green key; travel and hospitality award; other |

| Renewable energy sources | Dummy = 1 if yes; dummy = 0 if no | |

| Business dimension | Numeric | |

| No. of jobs | Numeric | |

| Education | 1—Basic studies, 2—Mid-level studies, 3—Graduates | |

| Gender | Dummy = 1 if male; dummy = 0 if female | |

| Job | Descriptive | |

| Age | Numeric | |

| Section I | General opinions | |

| Strategies for the territory | Strategy to develop the cross-border territory as a tourist destination | Descriptive |

| Benefits of proximity to another country/culture | Descriptive | |

Appendix B. Spatial Statistics Tools

| 1st phase | Data acquisition: alphanumeric lodgings and farms database; geocoding for cartography; cartography: http://centrodedescargas.cnig.es (accessed on 1 February 2022) https://sigtur.turismodeportugal.pt (accessed on 1 February 2022) | |

| 2nd phase |

| |

| 3rd phase | Spatial Statistics Tools | |

| Analyzing Patterns | Mapping Clusters | |

|

| |

| Spatial Relationships | ||

| ||

| Distance Method | ||

| ||

| 4th phase |

| |

Appendix C. Interpretation of Moran’s Global I Test and the Getis–Ord General G(d) Test

References

- Welteji, D.; Zerihun, B. Tourism-Agriculture Nexuses: Practices, challenges and opportunities in the case of Bale Mountains National Park, Southeastern Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R. Toward a better understanding of tourism and agriculture linkages in the Yucatan: Tourist food consumption and preferences. Tour. Geogr. 2002, 4, 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M. Tourism-agriculture linkages in rural South Africa: Evidence from the accommodation sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J.; Wall, G. Linkages Between Tourism and Food Production. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacher, R.G.; Nepal, S.K. From leakages to linkages: Local-level strategies for capturing tourism revenue in northern Thailand. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qiu, Z.; Nakamura, K. Tourist preferences for agricultural landscapes: A case study of terraced paddy fields in Noto Peninsula, Japan. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 1880–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D. Variations on the Rural Idyll. In Handbook of rural studies; SAGE Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, S.; González-Roa, M.C.; Calatrava-Requena, J. Public preferences for landscape features: The case of agricultural landscape in mountainous Mediterranean areas. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Spitaler, A.; Schamel, G. Agritourism: A hedonic approach of quality tourism indicators in South-Tyrol. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.; Momsen, J.H. Challenges and potential for linking tourism and agriculture to achieve pro-poor tourism objectives. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2004, 4, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C. Agriculture and tourism sector linkages: Global relevance and local evidence for the case of South Tyrol. Open Agric. 2019, 4, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchouamou Njoya, E.; Nikitas, A. Assessing agriculture-tourism linkages in Senegal: A structure path analysis. GeoJournal 2020, 85, 1469–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, M.; Rogerson, C.M. Agriculture-tourism linkages and pro-poor impacts: The accommodation sector of urban coastal KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 36, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W. Linkages between tourism and agriculture for inclusive development in Tanzania. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2018, 1, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Laeis, G. Linkages between tourist resorts, local food production and the sustainable development goals. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, G.N.; Pierce, S.M. An evaluation of ecotourism in Amazonas, Brazil. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 4, 843–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.C.; Sirakaya, E. Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardianou, E.; Kostakis, I.; Mitoula, R.; Gkaragkani, V.; Lalioti, E.; Theodoropoulou, E. Understanding the entrepreneurs’ behavioural intentions towards sustainable tourism: A case study from Greece. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 18, 857–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; McKercher, B.; Suntikul, W. Identifying core indicators of sustainable tourism: A path forward? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Oyola, M.; Blancas, F.J.; González, M.; Caballero, R. Sustainable tourism indicators as planning tools in cultural destinations. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, K. The challenges of developing health tourism in the Balkans. Tourism 2015, 63, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vučetić, A. Importance of environmental indicators of sustainable development in the transitional selective tourism destination. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Z.; Lu, C.F. Fuzzy Group Decision-Making in the Measurement of Ecotourism Sustainability Potential. Gr. Decis. Negot. 2013, 22, 1051–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, N.-W.; Chen, Y.-J.; Huang, C.-L. Linkages between organic agriculture and agro-ecotourism. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2008, 21, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Barbieri, C.; Anderson, D.; Leung, Y.F.; Rozier-Rich, S. Residents’ perceptions of wine tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Sotomayor, S.; Aguilar, F.X. Perceived Benefits of Agricultural Lands Offering Agritourism. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 16, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Chang, Y.R.; Liu, D.J. Rural tourism and environmental sustainability—A study on a model for assessing the developmental potential of organic agritourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastronardi, L.; Giaccio, V.; Giannelli, A.; Scardera, A. Is agritourism eco-friendly? A comparison between agritourisms and other farms in italy using farm accountancy data network dataset. Springerplus 2015, 4, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C. Assessing the sustainability of agritourism in the US: A comparison between agritourism and other farm entrepreneurial ventures. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanescu, B.C.; Stoleriu, O.M.; Munteanu, A.; Iaţu, C. The impact of tourism on sustainable development of rural areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, C.; Barbieri, C. Agritourism as a sustainable adaptation strategy to climate change in the Andean Altiplano. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 11, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, C.; Barbieri, C.; LaPan, C. The Influence of Agritourism on Niche Meats Loyalty and Purchasing. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TarvelBi Turismo de Portugal. Available online: https://travelbi.turismodeportugal.pt/%0ATravelBi (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Observatório de Turismo de Extremadura. Available online: https://www.turismoextremadura.com/es/pie/observatorio.html (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Dubois, C.; Cawley, M.; Schmitz, S. The tourist on the farm: A ‘muddled’ image. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Culinary tourists in the Spanish region of Extremadura, Spain. Wine Econ. Policy 2014, 3, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.I.R.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. Shedding Light on Agritourism in Iberian Cross-Border Regions from a Lodgings Perspective. Land 2022, 11, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheskin, D.J. The Mann–Whitney U Test. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Weiner, I.B., Craighead, W.E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed, K.H. La distribution du tau de Kendall pour tester la significativité de la corrélation croisée dans des données persistantes. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2011, 56, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I.; Blas-Morato, R. Hot Spot Analysis versus Cluster and Outlier Analysis: An enquiry into the grouping of rural accommodation in Extremadura (Spain). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sandt, A.; Low, S.A.; Thilmany, D. Exploring Regional Patterns of Agritourism in the U.S.: What’s Driving Clusters of Enterprises? Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2018, 47, 592–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Tian, Z.; Goetz, S.; Chase, L.; Hollas, C. Agritourism and Direct Sales Clusters in the United States; AgEcon Search: Anaheim, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aronica, M.; Cracolici, M.F.; Insolda, D.; Piacentino, D. The Diversification of Sicilian Farms: A Way to Sustainable Rural Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Delgado, L.-M.; Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I. An Analysis of Online Reputation Indicators by Means of Geostatistical Techniques—The Case of Rural Accommodation in Extremadura, Spain. Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Rangel, M.C.; Rivero, M.S. Spatial imbalance between tourist supply and demand: The identification of spatial clusters in Extremadura, Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. The future of spatial analysis in the social sciences. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1999, 5, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero Sánchez, M. Análisis espacial de datos y Turismo: Nuevas técnicas para el análisis turístico. Rev. Estud. Empres. 2008, 2, 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, P.A.P. The Interpretation of Statistical Maps. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1948, 10, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getis, A.; Ord, J.K. The Analysis of Spatial Association by Use of Distance Statistics. Geogr. Anal. 1992, 24, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, J.K.; Getis, A. Local Spatial Autocorrelation Statistics: Distributional Issues and an Application. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Hsieh, H.P. Indicators of sustainable tourism: A case study from a Taiwan’s wetland. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 67, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Tribe, J. Sustainability indicators for small tourism enterprises—An exploratory perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assandri, G.; Bogliani, G.; Pedrini, P.; Brambilla, M. Beautiful agricultural landscapes promote cultural ecosystem services and biodiversity conservation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamung, R. A Study of Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Agriculture Conservation as a Means to Develop Rural Farms as Agritourism Destinations. Silpakorn Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 15, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, N.J.; Barrett, B. Heritage Values and Agricultural Landscapes: Towards a New Synthesis. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. WHC/2/Revised. February1994. 20p. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000130614 (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Jiménez, M.I.M. Heritage and landscape in Spain and Portugal. From singular value to territorial integration. Bol. La Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2016, 71, 347–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, A.; Ledda, A.; Serra, V.; Noce, M.; Barra, M.; De Montis, S. A method for analysing and planning rural built-up landscapes: The case of Sardinia, Italy. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.R. Tourism and global logistics hub development in the Caribbean: Will there be a symbiotic relationship? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampela, S.; Papapanos, G.; Kizos, T. Perceptions of agritourism and cooperation: Comparisons between an Island and a mountain region in Greece. Sustainability 2019, 11, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.; De Master, K. New rural livelihoods or museums of production? Quality food initiatives in practice. J. Rural. Stud. 2011, 27, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Yen, C.Y.; Tsai, K.N.; Lo, W.S. A conceptual framework for agri-food Tourism as an eco-innovation strategy in small farms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavec, M.; Mlakar, S.G.; Rozman, C.; Pazek, K.; Bavec, F. Sustainable agriculture based on integrated and organic guidelines: Understanding terms. The case of Slovenian development and strategy. Outlook Agric. 2009, 38, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Jamal, T. Tourism on organic farms in South Korea: A new form of ecotourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.J.; Lima, J.; Silva Lavrador, A. Landscape and the rural tourism experience: Identifying key elements, addressing potential, and implications for the future. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguay, G.A.; Rajaonson, J.; Therrien, M.-C. Sustainable tourism indicators: Selection criteria for policy implementation and scientific recognition. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 862–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzenbacher, D.J. Exploring the food tourism landscape and sustainable economic development goals in Dhofar Governorate, Oman: Maximising stakeholder benefits in the destination. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 1897–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandth, B.; Haugen, M.S. Farm diversification into tourism—Implications for social identity? J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Extremadura. Estrategia de Turismo Sostenible de Extremadura 2030 II Plan Turístico de Extremadura 2021–2023; Junta de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- EY-Parthenon Estratégia Regional de Desenvolvimento Turístico do Alentejo e Ribatejo 2021–27, 2020, 97p. Available online: https://www.visitalentejo.pt/fotos/editor2/pdfs/Documentos_Estrategicos/ERT_Alentejo_Relatorio_Final_122020.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Turismo Centro de Portugal Plano Regional de Desenvolvimento Turístico 2020–2030, 2019, 176p. Available online: https://turismodocentro.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TCP-Plano-Regional-Desenvolvimento-Tur%C3%ADstico_20-30.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Barbieri, C.; Mahoney, E. Why is diversification an attractive farm adjustment strategy? Insights from Texas farmers and ranchers. J. Rural Stud. 2009, 25, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, M.J.; Blas-Morato, R.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I. The dehesas of Extremadura, Spain: A potential for socio-economic development based on agritourism activities. Forests 2019, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, H.K. The latest trends in nature-based outdoor recreation. For. Hist. Today 2008, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sastre, R.; Ravera, F.; González, J.A.; López Santiago, C.; Bidegain, I.; Munda, G. Mediterranean landscapes under change: Combining social multicriteria evaluation and the ecosystem services framework for land use planning. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masot, A.N.; Rodríguez, N.R. Rural tourism as a development strategy in low-density areas: Case study in northern extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Panaro, S. From perceived values to shared values: A Multi-Stakeholder Spatial Decision Analysis (M-SSDA) for resilient landscapes. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, P.E. Euclidean distance mapping. Comput. Graph. Image Process. 1980, 14, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L.; Bera, A.K.; Florax, R.; Yoon, M.J. Simple diagnostic tests for spatial dependence. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1996, 26, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| Economic |

|

| |

| Socio-cultural |

|

| |

| Environmental |

|

|

| Sociodemographic Variables | Accommodations n = 41 | Accommodations with Agricultural Activity n = 49 | Farmers n = 11 | Total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 27 (66%) | 26 (53%) | 9 (82%) | 62 | 62 |

| Female | 14 (34%) | 23 (47%) | 2 (18%) | 39 | 39 | |

| Age | 25–29 | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 | 2 |

| 30–34 | 2 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 4 | 4 | |

| 35–39 | 7(17%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (9%) | 11 | 11 | |

| 40–44 | 5 (12%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (27%) | 10 | 10 | |

| 45–49 | 4 (10%) | 10 (20%) | 3 (27%) | 17 | 17 | |

| 50–54 | 8 (20%) | 8 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 16 | 16 | |

| 55–59 | 3 (7%) | 14 (29%) | 3 (27%) | 20 | 20 | |

| 60–64 | 7 (17%) | 6 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 13 | 13 | |

| ≥65 | 3 (7%) | 4 (8%) | 1 (9%) | 8 | 8 | |

| Study level | Elementary school | 3 (7%) | 4 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 7 | 7 |

| Middle school | 7 (17%) | 10 (20%) | 3 (27%) | 20 | 20 | |

| High school or above | 31 (76%) | 35 (71%) | 8 (73%) | 74 | 74 | |

| Tourism-related qualifications | 7 (17%) | 4 (8%) | 1 (9%) | 12 | 12 | |

| Agriculture-related qualifications | 0 (0%) | 7 (14%) | 4 (36%) | 11 | 11 | |

| Time spent in business | Total | 3 (7%) | 9 (18%) | 8 (73%) | 20 | 20 |

| Partial | 38 (93%) | 40 (82%) | 3 (27%) | 81 | 80 | |

| Experience in business (nº of years) | 0–3 | 14 (34%) | 14 (29%) | 5 (45%) | 33 | 33 |

| 4–9 | 15 (37%) | 22 (45%) | 3 (27%) | 40 | 40 | |

| 10–20 | 10 (24%) | 10 (20%) | 2 (18%) | 22 | 22 | |

| >20 | 2 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (9%) | 6 | 6 | |

| Indicator | Objective | Variable | Typology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural/ Landscape | Valuing the aesthetic qualities of cultural heritage | Visual quality of the landscape | Quantitative |

| Localization in historic villages | Dummy | ||

| Monuments and historic heritage | Dummy | ||

| Valuing of traditional architecture | Dummy | ||

| Valuing of natural heritage | Dummy | ||

| Valuing of cultural heritage | Dummy | ||

| Economy | Valuing invisible economic impacts | Direct sales / personal sales | Dummy |

| Online sales | Dummy | ||

| Employment growth | Quantitative | ||

| Economic activity diversification | Quantitative | ||

| Partnerships with tourism sector | Quantitative | ||

| Partnerships with farmers | Quantitative | ||

| Origin certification (PDO/PGI) | Dummy | ||

| Quality certification | Quantitative | ||

| Environmental | Valuing the preservation of nature and biodiversity | Renewable energy sources | Dummy |

| Organic certification | Dummy | ||

| Localization in natural or protected areas | Dummy | ||

| Autochthonous plant and animal species | Dummy | ||

| Ecosystem services | Dummy | ||

| Prevention of natural hazards | Quantitative | ||

| Education in sustainability culture | Dummy | ||

| Biodiversity conservation | Quantitative | ||

| Circular economy measures | Quantitative | ||

| Society | Valuing activities and immaterial heritage | Tourism services (accommodation) | Dummy |

| Tourism services (entertainment) | Dummy | ||

| Valuing traditional knowledge | Dummy | ||

| Rural festival organization/participation | Dummy | ||

| Agritourism activities | Quantitative | ||

| Communication of agritourism activities | Dummy | ||

| Social agriculture | Dummy |

| Activities | Descriptions of Some Examples |

|---|---|

| Experiences | “Olive oil route with 3 days of experiences”, “Picnic in olive grove”, “Photo tours in dehesa/montado”, “Rural day” |

| Accomodation on arms | “Herdade da Urgueira”; “Herdade da Sarvinda”; “Herdade da Tapada da Tojeira”; “Almojanda 3 olive tree”; “Olivoturismo Casa Mestre do Lagar”, “Casa da Urra”, “Finca la Ramallosa”, |

| Learning about agriculture and animal husbandry | “Quinta dos Ribeiros”, “Monte do Pego”, “Quinta de São Pedo de Vir a Corça” |

| Olive oil tasting | “Herdade da Tapada da Tojeira”; “Azeite Castelo de Marvão”; “Real Idanha” |

| Visiting oil mills | “Herdade da Tapada da Tojeira”, “Olive oil mills musuem in Vila Velha de Rodão”, “Olive oil mills musuem in Idanha-a-Nova”, |

| Olive picking | Beir’Aja; “Real Idanha” |

| Feeding animals, sheep milking, artisan cheese | “Herdade da Bezágueda”, “Beir’Aja”, “Alojamento Casa 25”, |

| Bird watching (dehesa) | “El millaron”, “Herdade da Sarvinda” |

| Stargazing (dehesa) | “Casa Rural Montanío Blanco”, |

| Educational activities | “Beira’Aja”, “Herdade da Bezágueda” |

| Variables | Farmers n = 11 | Accommodation with Agricultural Activity n = 49 | Accommodation n = 41 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | |

| Location in historic villages | 4 | 0.001 ** | 63 | 0.007 ** | 33 | 0.200 |

| Location close to cultural heritage sites | 6 | 0.080 | 36 | 0.250 | 58 | 0.026 ** |

| Valuing traditional architecture | 5 | 0.225 | 52 | 0.298 | 42 | 0.225 |

| Valuing natural heritage | 4 | <0.001 ** | 63 | 0.001 ** | 33 | 0.133 |

| Valuing cultural heritage | 6 | 0.475 | 36 | 0.278 | 57 | 0.261 |

| Variables | Farmers N = 11 | Accommodation with Agricultural Activity N = 49 | Accommodation N = 41 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | |

| Direct sales | 28 | 0.008 ** | 68 | 0.005 ** | 4 | <0.001 ** |

| Online sales | 16 | 0.437 | 33 | 0.220 | 50 | 0.031 ** |

| Quality origin seal (PDO/PGI) | 40 | 0.405 | 60 | 0.002 ** | 0 | <0.006 ** |

| Quality certification | 27 | 0.019 ** | 63 | <0.001 ** | 0 | <0.001 ** |

| Variables | Farmers N = 11 | Accommodation with Agriculture Activity N = 49 | Accommodation N = 41 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | |

| Job creation | 8 | U = 1490 p = 0.124 ** | 54 | U = 497 p = 0.977 ** | 38 | U = 1045 p = 0.185 ** |

| Entrepreneurial diversification | 9 | U = 2231 p ≤0.001 | 65 | U = 378 p = 0.157 ** | 26 | U = 438 p ≤ 0.001 |

| Partnerships with tourism | 19 | U = 1266 p = 0.968 ** | 48 | U = 712 p = 0.012 | 33 | U = 1049 p = 0.184 ** |

| Partnerships with farmers | 12 | U = 1145 p = 0.289 ** | 43 | U = 717 p = 0.003 | 28 | U = 1150 p = 0.495 ** |

| Variables | Farmers N = 11 | Accommodation with Agriculture Activity N = 49 | Accommodation N = 41 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | |

| Sustainable certification | 28 | 0.048 ** | 71 | 0.003 ** | 0 | <0.001 ** |

| Autonomous species or races | 20 | <0.001 ** | 80 | 0.005 ** | 0 | <0.001 ** |

| Renewable energy | 22 | 0.584 | 55 | 0.012 ** | 22 | 0.044 * |

| Sustainable education | 44 | 0.846 | 44 | <0.001 ** | 2 | 0.059 * |

| Location in natural areas | 7 | 0.001 ** | 22 | 0.007 ** | 70 | 0.200 |

| Variables | Farmers N = 11 | Accommodation with Agricultural Activity N = 49 | Accommodation N = 41 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | |

| Prevention of natural hazards | 35 | U = 1697 P ≤ 0.001 | 65 | U = 821 P ≤ 0.001 | 0 | U = 499 P ≤ 0.001 |

| Biodiversity measures | 25 | U = 1637 P = 0.002 | 75 | U = 661 P = 0.021 | 0 | U = 712 P ≤ 0.001 |

| Circular economy measures | 38 | U = 1538 P = 0.029 | 62 | U = 743 P = 0.001 | 5 | U = 731 P ≤ 0.001 |

| Variables | Farmers N = 11 | Accommodation with Agriculture Activity N = 49 | Accommodation N = 41 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | % | Statistical Values | |

| Accommodation services | 0 | <0.001 * | 55 | <0.001 ** | 45 | 0.002 ** |

| Tourism services | 43 | 0.597 | 57 | 0.005 ** | 0 | 0.023 * |

| Agritourism services/activities (marketing) | 26 | 0.377 | 69 | 0.012 ** | 5 | 0.015 ** |

| Participating in/organizing rural fairs or festivals | 66 | 0.294 | 33 | <0.001 ** | 0 | 0.002 * |

| Valuing traditional knowledge | 25 | 0.008 ** | 66 | <0.001 ** | 9 | <0.001 ** |

| Social agriculture | 38 | 0.002 ** | 62 | 0.003 ** | 0 | <0.001 ** |

| Results | Nº | Area |

|---|---|---|

| Hot spot 99% confidence | 2 | Beira Baixa |

| Hot spot 95% confidence | 6 | Beira Baixa |

| Hot spot 90% confidence | 3 | Beira Baixa |

| Not significant | 79 | Scattered |

| Cold spot 90% confidence | 10 | Alto Alentejo |

| Cold spot 95% confidence | 1 | Alto Alentejo |

| Cold spot 99% confidence | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues Ferreira, D.I.; Loures, L.C.; Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. Spatial Analysis of Sustainability Measures from Agritourism in Iberian Cross-Border Regions. Land 2023, 12, 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040826

Rodrigues Ferreira DI, Loures LC, Sánchez-Martín J-M. Spatial Analysis of Sustainability Measures from Agritourism in Iberian Cross-Border Regions. Land. 2023; 12(4):826. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040826

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues Ferreira, Dora Isabel, Luís Carlos Loures, and José-Manuel Sánchez-Martín. 2023. "Spatial Analysis of Sustainability Measures from Agritourism in Iberian Cross-Border Regions" Land 12, no. 4: 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040826

APA StyleRodrigues Ferreira, D. I., Loures, L. C., & Sánchez-Martín, J.-M. (2023). Spatial Analysis of Sustainability Measures from Agritourism in Iberian Cross-Border Regions. Land, 12(4), 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040826