Abstract

Capital outflow during industrialization and urbanization is a primary reason for global rural recession, and China is no exception. Since China focuses on the integrated development of urban and rural areas, urban-rural capital flow affects the transformation and sustainable development of rural areas. However, few studies have focused on this issue. Based on long-term field observations of Wufang Village in Shanghai, we established an analytical framework to describe how urban-rural capital flow promotes rural reconstruction. The research results show that the influx of urban industrial and commercial capital results in market-oriented organization and reconstruction focusing on land, industry, and capital: (1) Land-use optimization changes the land ownership and spatial structure of rural areas and improves the spatial value of rural areas. (2) Industrial development is focused on diverse development and the integration of primary, secondary, and tertiary industries in rural areas. (3) Capital investment is performed by a consortium of state-owned enterprises, private enterprises, and rural collective enterprises—which jointly invest, obtain revenue, and share profits—while considering the balance between attracting capital to rural areas and achieving independent development. The experience of Wufang Village has implications for the rural transformation policies of other large cities in China and other countries in Asia and Africa during urbanization.

1. Introduction

Rural areas have multiple functions that benefit both rural and urban areas, including ecological protection, agricultural production, social security, and stability [1]. The International Geographical Union Commission on Agricultural Geography and Land Engineering (IGU-AGLE) has identified global rural development and land degradation as a priority issue in the Global Rural Plan (GRP). Some rural villages have become characteristic of professional villages during reverse urbanization or rural gentrification, such as industrial villages, tourist villages, or modern agricultural villages [2,3]. However, most of the world’s villages still suffer from labor outflow, population aging, agricultural restructuring, land degradation, and environmental pollution, causing a decline in villages [4,5]. As the largest developing country in the world, China has experienced dramatic changes in the spatial pattern, structure, and social organization in rural areas during rapid industrialization and urbanization. Many rural areas can no longer withstand these challenges [6]. Rural recession is particularly prominent. These problems have resulted in a significant decrease in the number of rural villages, hollowing out of rural areas, a weakening of the industrial base, and the loss of cultural resources [4].

Rural reconstruction of the economy, society, and culture has become the focus of scholars and policies to revive rural competitiveness, reverse the rural decline, and achieve sustainable development. Rural reconstruction emphasizes human intervention and regulation of the structure and function of the rural, regional system, and it involves spatial, economic, and social reconstruction [7]. In the 1970s, manufacturing industries in western countries moved from cities to rural areas, and the capital inflow and industries transformed rural areas and agriculture, triggering the economic restructuring of rural areas [8]. Since then, rural reconstruction in western countries has shifted from economic reconstruction to social, local, and national reconstruction [9]. Extensive research has been conducted on rural reconstruction. Scholars have discussed changes in the patterns of various elements during rural restructuring and analyzed the relationship between these elements and rural transformation [10,11,12]. Some studies have analyzed various strategies of rural reconstruction and their impacts on vulnerable groups, such as women and children [13,14]. Scholars utilized the theory of reciprocal rural-urban linkages [15], and focused on perspective beyond the rural regional system to explore the impact of the flow of elements between urban and rural areas on rural reconstruction. Some researchers believe that the development of Internet technology has accelerated the global flow of production factors, triggering extensive rural reconstruction [16,17]. Some studies regard urban residents as important actors in rural reconstruction, acting as consumers because the rural areas provide urban residents with diversified goods and services in agriculture, culture, and ecology [18]. However, research on rural reconstruction in China is lagging behind that in other areas. Most studies were based on the theoretical perspective of the human–land relationship, focusing on the rural regional system and analyzing changes in rural factors, such as land, culture, and farmers’ behavior [19,20,21]; the evolution of the spatial and temporal pattern of rural areas, and the mechanism of rural reconstruction [22,23,24]. Our goal is to analyze the impact of urban industrial and commercial capital on rural reconstruction and to provide an external research perspective for investigating rural reconstruction in China.

Capital is crucial for production and rural reconstruction. Rural development in developed countries has shown that urban-rural capital flow has improved the economy, landscape, and environment of rural areas, significantly impacting the rural governance system and social structure [25]. China has issued several policies to encourage and standardize investments in social capital in agriculture and rural areas. Examples include the Notice of the National Development Bank on Innovating Investment and Financing Models and Accelerating the Construction of High-standard Farmland (2015), the Guidance on Deepening the Reform of Farmland and Water Conservancy (2018), and the Guidance on Social Capital Investment in Agriculture and Rural Areas (2021). These policies encourage urban industrial and commercial capital financing to achieve land consolidation and infrastructure construction in rural areas [26,27] and provide a legal basis for urban-rural capital flow. The capital is concentrated in cities and towns in secondary and tertiary industries, which are more profitable and stable. However, due to the rapid development of big cities, the competition is saturated, and the highly homogeneous internal consumption has led to diminishing marginal benefits of capital appreciation. Therefore, the industrial and commercial capital has begun to spill over, resulting in new investment opportunities. Due to the policy dividend, urban industrial and commercial capital is being invested in agriculture and rural areas. However, due to the urban-rural duality and profit-seeking, urban industrial and commercial capital is not invested in key industries and fields in rural areas as envisioned by the government. As a result, villagers do not benefit from the value-added income, and “elite capture” occurs in the economy and politics [28]. Factor mismatch, lack of supporting services and policies, and credit risks occur between urban industrial and commercial capital and rural development in China [29]. Theoretical analysis and practical investigations are required to determine how to utilize social capital during rural transformation and reconstruction in China. The literature review shows that urban industrial and commercial capital is a double-edged sword for rural reconstruction. Therefore, this study aims to answer the question “how can we make good use of social capital during rural transformation and reconstruction in China” by describing a successful case.

Metropolitan villages have more frequent and diverse urban-rural interactions than traditional agricultural villages, resulting in different spatial distributions of land-use types and land-use competition [30]. Urban-rural integration occurs more rapidly in metropolitan cities, and industry, capital, and labor force flow both ways [31]. Therefore, metropolitan cities can attract capital flow to rural areas. The rural areas in many metropolises in China, such as Beijing and Shanghai, have gone through spatial reconstruction and material accumulation by relying on state funding. In some cases, industrial and commercial capital has flowed to rural areas, providing a basis for our in-depth analysis. However, few studies have focused on the uniqueness of big cities and villages and the role of urban industrial and commercial capital in rural reconstruction. Therefore, we chose a typical village in Shanghai as a research case. Shanghai has been at the forefront of rural development in China. Its experience has implications for the rural transformation of other metropolitan cities in China and for the rural transformation policies of other countries in Asia and Africa during urbanization.

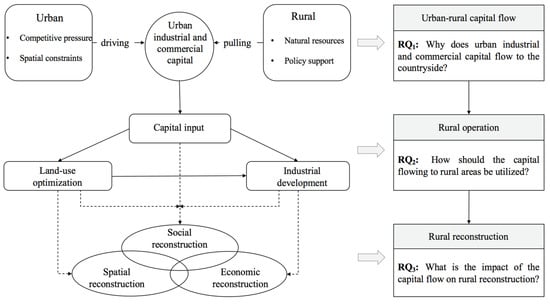

This study establishes an analytical framework to describe how urban and rural capital flows promote rural reconstruction in China’s major cities and selects typical cases for empirical analysis. This paper aims to answer three key questions: (1) Why does urban industrial and commercial capital flow to the countryside? (2) How should the capital flowing to rural areas be utilized? (3) What is the impact of the capital flow on rural reconstruction? We summarize the rural reconstruction model of China’s metropolitan cities based on the results of the case study and provide suggestions for the rural development of China’s metropolitan cities. We also discuss the relationship between rural operation, rural resilience, and rural gentrification and present the limitations of this study and future research directions. This paper provides theoretical and empirical contributions. The first theoretical contribution is our innovation in the research perspective, focusing on the role of urban industrial and commercial capital as an external factor, rather than the rural regional system itself, in the revitalization of rural areas. Second, we propose the concept of the “rural operation”, which is used to summarize several actions carried out by urban enterprises related to the land, industry, and capital to reshape the countryside. Finally, we expand the research on rural reconstruction and reveal the impact of the rural operation on rural reconstruction. Empirically, our case study is strategically well chosen because it is a pilot district for China’s rural revitalization strategy. Thus, it may be informative for what might happen in the coming decades in rural towns and villages nationwide.

2. Analytical Framework for Urban-Rural Capital Flow for Rural Reconstruction

Capital flows to places where it can add value and provide profits. The power of urban industrial and commercial capital flowing to the countryside comes from two aspects: he push by the city and the pull from the countryside. From the perspective of thrust, when the market economy and the comparative advantages of differences in production factors and economic gradients are considered, industrial transfer will become an inevitable trend when the capital in cities faces fierce competition [32]. In China, the government has strictly restricted the size and scope of cities through planning, and the land available for investment and production in cities is limited. The production costs of enterprises continue to rise with an increase in land prices in cities. According to the rent difference theory, urban industrial and commercial capital will flow to rural areas with lower land prices to seek new development opportunities [33]. From the perspective of the pulling force, there are large areas of abandoned farmlands, vacant homesteads, and inefficient construction land in the countryside, representing valuable resources for enterprises to achieve capital appreciation. China has introduced tax exemption or subsidy policies to encourage urban industrial and commercial capital to participate in rural development, enhancing the attractiveness of rural capital.

Urban industrial and commercial capital flows to rural areas and is used for improvements related to land, industry, and capital. This is referred to as rural operation. Specifically, after the urban industrial and commercial capital has flown to rural areas, it is used for capital input, land-use optimization, and industrial development. Capital input is the primary aspect because of the diverse types of urban industrial and commercial capital. The capital provides financial support for other operational activities. Subsequently, land-use optimization is performed, such as land consolidation, rural infrastructure construction, and adjustments in land ownership and land-use type to stimulate the rural land market [34]. The next step is rural industrial development. Urban industrial and commercial capital are used to modernize agriculture and implement ecological agriculture in rural areas, resulting in the development of secondary and tertiary industries. The integrated development of industries is encouraged, demonstrating the value of rural land [35].

Rural reconstruction refers to the optimization of the social and economic structure and spatial pattern of the rural, regional system. Researchers have focused on spatial, economic, and social reconstruction [33]. Spatial reconstruction is achieved by land-use optimization, i.e., cultivated land, collective construction land, residential areas, and natural areas, such as forest and water areas. Economic reconstruction focuses on problems affecting rural economic development, such as rural industrial development and income distribution. Social reconstruction focuses on the reconstruction of rural society and is people oriented. Due to changes in the rural population structure and lifestyle, it is necessary to improve rural public services and social security.

It involves a reorganization of the rural, regional system to transform the rural social and economic structure. First, land-use optimization is critical in rural spatial reconstruction. Urban industrial and commercial capital is used to transform rural land through market transactions and engineering construction, coordinate industrial development, construct agricultural housing, implement public services, and ensure ecological protection. The goal is to maximize benefits, optimize land use, protect natural areas, and ensure the safety of people. Second, industrial development and capital investment are focused on eliminating small-scale agriculture and promoting the economic reconstruction of rural areas. Urban industrial and commercial capital is used to modernize the agricultural industry to provide high-quality service in rural areas with large investments, advanced technology, and strict quality control requirements. The villagers supply their land and share the income of land appreciation through dividends, which differs from the traditional economic model of extensive management and family responsibility for profit and loss. Land-use optimization, capital investment, and industrial development result in rural social change and the reconstruction of rural society. After land-use optimization, rural residential areas are more concentrated, and industrial development and capital input change the employment mode and income structure of villagers, causing people to return to rural areas. As a result, the social structure in rural areas is transformed.

In summary, we establish a theoretical analysis framework of urban-rural capital flow and rural reconstruction (Figure 1) to analyze rural reconstruction in China’s big cities as a result of urban industrial and commercial capital spillover. An analysis of the capital input, land-use optimization, and industrial development after the inflow of urban industrial and commercial capital is conducted to determine the impact on rural areas, economy, and society to understand the rural restructuring mechanism of China’s metropolitan cities.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

3. Case Study and Methods

3.1. Case Selection

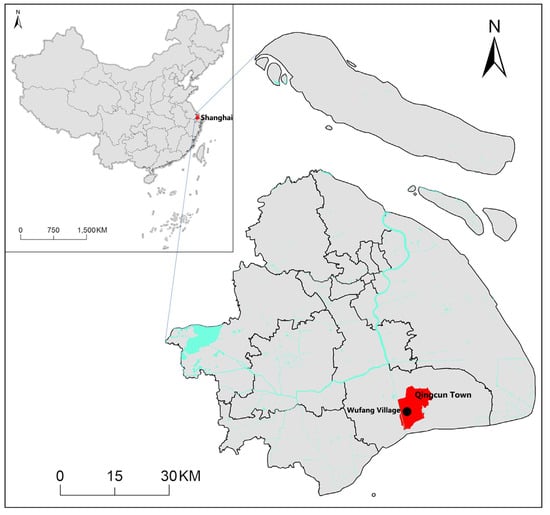

We chose Wufang Village, which is located in Qingcun Town, Fengxian District, Shanghai (Figure 2). The village area is about 1.99 square kilometers and has 421 households. The village was selected as a case study for three reasons: (a) Shanghai is one of the most rapidly developing and representative international metropolises in China. From the perspective of economic level and degree of marketization, the study of rural areas in Shanghai provides a good comparison with western research results and provides development experience for rural transformation in other major urban areas in China and countries in Asia or Africa. (b) Wufang Village is one of the first rural revitalization demonstration villages in Shanghai. We believe that the policy pilot area has important research value. Therefore, we conducted a long-term follow-up survey of the village and found that urban industrial and commercial capital played an important role in the revitalization of Wufang Village. Specifically, the reconstruction of Wufang Village was led by a company owned by Qingcun Town, other state-owned enterprises, and some private enterprises in Shanghai. The diverse capital types help us understand how urban-rural capital flow affects rural reconstruction. (c) Wufang Village is a model of spatial, economic, and social rural reconstruction. Before 2018, Wufang Village was a poor village with extensive yellow peach cultivation, and farmland degradation was significant. Many young people had moved to the urban area of Shanghai. Thus, the majority of the people in the village were older and younger people, and the house vacancy rate was 60%. Since then, Wufang Village has been transformed into a complex business area due to village reconstruction, broadening the income channels of villagers, improving the rural area, and attracting talents to return to their hometown. An analysis of the Wufang Village’s case can help us study the impact of the rural operation on rural reconstruction.

Figure 2.

The location of Wufang village. Source: authors’ drawing.

3.2. Research Methods

We conducted field studies in Wufang Village in August 2020 and July 2021. Since rural reconstruction cannot be separated from the active participation of various stakeholders, we conducted semi-structured interviews with different subjects, including members of the superior town government of Wufang Village, the village committee, local villagers, and existing enterprises. We conducted sufficient background research on Wufang Village, prepared an interview outline, developed a detailed case study plan, and constructed a case study database. It contained recordings, documents, photos, and other forms of data. We verified the data using multiple sources to ensure the accuracy of the primary database. We also collected secondary data related to the case study, including academic literature, policy documents, village planning data, and news reports.

We used inductive data analysis and systematically classified the material. Specifically, we read all the obtained data and classified the material according to the three aspects of rural operation (capital investment, land-use optimization, and industrial development). We then extracted seven secondary subjects from the material using coding to interpret the case in an orderly manner. Table 1 lists examples of operations conducted in Wufang Village using the urban industrial and commercial capital.

Table 1.

Examples of operations conducted in Wufang Village using the urban industrial and commercial capital.

4. Research Results

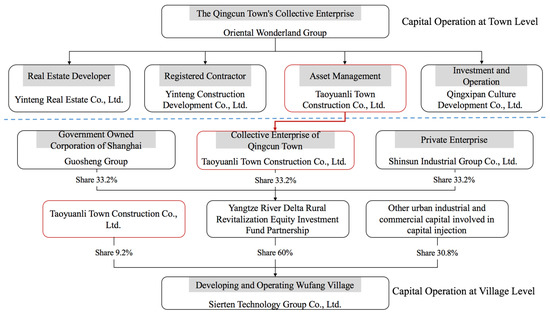

4.1. Capital Investment Using a Platform Structure

Due to the diverse types of urban industrial and commercial capital involved in rural transformation, it is necessary to conduct integrated operations to lay a solid foundation for the subsequent land transformation and industrial development. In Wufang Village, the town-village level handles the capital sent to rural areas using a platform structure.

At the township level, Qingcun Town conducts the inventory and classification of assets. It established a township company (Oriental Wonderland Group). The company conducts marketing activities on behalf of 24 administrative villages, including Wufang. The Oriental Wonderland Group has four subsidiaries: Yinteng Construction, Yinteng Real Estate, Qingxipan, and Taoyuanli. They are, respectively, responsible for rural infrastructure construction, rural homestead renovation, project investment and operation, and professional asset management. At the village level, the company responsible for Wufang’s operations, Sierten, is a joint venture between Taoyuanli, the Yangtze River Delta Rural Revitalization Fund, and other companies (Figure 3). One-third of the Yangtze River Delta Rural Revitalization Fund is held by the Guosheng Group (Shanghai state-owned capital operation company), Taoyuanli Company (Qingcun Collective capital operation company), and the Xiangsheng Group (private enterprise).

Figure 3.

The structure of capital investment and control in Wufang Village.

This platform-based organization model facilitates layer-by-layer supervision and minimizes risk. The Oriental Peach Garden Company is a township asset and has four subsidiaries. The Sierten Company is responsible for the Wufang Village operation, and the other industrial operators are managed by the township platform. The government is the granting authority and determines the business scope and terms, controlling numerous market players. A branch of the town’s platform company (Taoyuanli) participated in the development of its organizational structure to ensure that the operation of the Sierten Company conformed to the interests of the village. Taoyuanli defined the goals and visions of the company so that it could devote itself to the integrated development of the rural revitalization industry. The Rural Revitalization Fund of the Yangtze River Delta represents a new channel for urban-rural capital flow to integrate state-owned, collective, and private capital. Taoyuanli Company, the major shareholder of the Yangtze River Delta Rural Revitalization Fund and the Sierten Company, is the leader in the Qingcun Platform Company and is responsible for the social capital participating in the reconstruction. This strategy controls the investment of urban industrial and commercial capital in rural areas to ensure that value-added services are obtained.

4.2. Land Use and Rural Operation under Government Guidance and Market Dominance

4.2.1. Direction of Land Use and Rural Operation

Land is essential for agricultural production in rural areas. However, most rural areas in China suffer from unused land, low use efficiency, and low values of the homestead, agricultural land, and collective construction land. Thus, land-use optimization and rural operation are critical in urban-rural capital flow. These strategies require careful planning by the government and the appropriate participation of administrative staff to avoid predatory development of rural areas.

The Qingcun government performs strategic planning, which has been used extensively in China for land resource management and urban and rural economic and social governance. Regular bottom-line control methods are conducted through planning, preparation, and land-use approval. Based on the Master Plan of Qingcun Town of Fengxian District (2014-2040) and the Rural Unit Village Planning of Qingcun Town of Fengxian District, the government of Qingcun Town guided Wufang Village to compile planning of the Wufang Village of Qingcun Town in the Fengxian District (2017-2035). The land-use zoning and control rules were improved, such as farmland protection and a reduction in the area ratio of residential land to industrial land. Plans for centralized residences and land consolidation were created to guide rural construction. The local governments allowed for flexible adjustment in the implementation of the land-use plan according to the needs of the rural operation. For example, the farmland layout in the village was gradually adjusted to meet the land needs of large agricultural enterprises and supporting facilities.

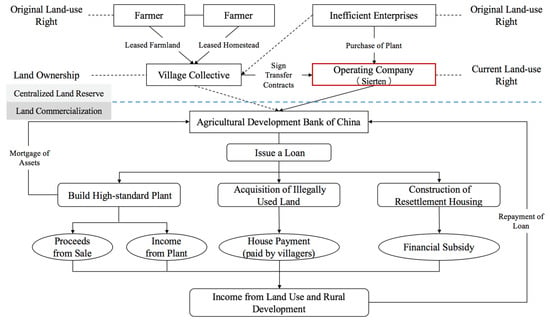

4.2.2. Market-Led Land-Use Intensification and Commercialization

After the urban capital was received by Wufang Village, two stages occurred in land marketization (Figure 4). The first was the centralized purchase of idle residential land, agricultural land, and collective construction land by adjusting the right of use. The second was to cooperate with the Agricultural Development Bank of China to commercialize land development and operation.

Figure 4.

Land use and rural operation in Wufang Village.

In the first stage, homestead and agricultural land acquisition were jointly promoted by the village committee and the Sierten Company. The village committees acted as middlemen, signing contracts with villagers to lease houses and farmland, which were leased to companies. The company was responsible for providing funds for the centralized relocation of villagers, building resettlement houses, and renovating houses in accordance with the style guidelines provided in the village plan. The soil of agricultural land was improved, and agricultural support facilities were constructed. Inefficient collective construction land was acquired by the Sierten Company, resulting in a change in the right of use. In the past, the inefficient use of collective construction land in Wufang Village was mostly historically illegal land without property rights. The Sierten Company acquired this land on behalf of Wufang Village and obtained the use right of the land.

In the second stage, the Sierten Company cooperated with the Agricultural Development Bank of China to create concentrated residential areas for farmers and developed rural land based on the market-oriented operation to ensure sufficient operating capital. First, Sierten submitted a financial proposal to the bank to use the collective construction land for constructing a high-tech industrial plant. This plan was supported by the bank. The Sierten Company, as the main lender, applied for the first loan of 2.6 billion yuan, using these factories as collateral. Sierten then used the loan to buy historically illegal land and build high-tech factories and affordable housing for farmers. Ultimately, Sierten repaid the bank loan with the income from the plant, the rent from farmers, and the government’s financial subsidies.

4.3. Industrial Development

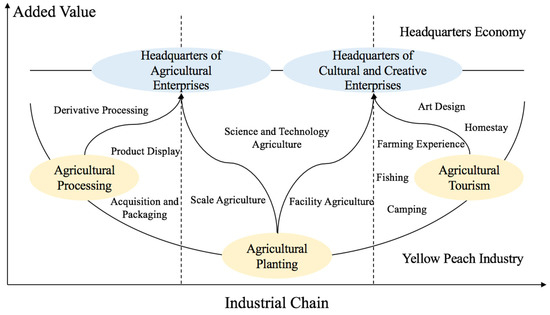

The Sierten company focused on the yellow peach industry base of Wufang Village to perform industrial integration and relocated the company’s headquarters to attract investment, enriching the types of businesses in Wufang Village (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Industrial Development of Wufang Village.

The Sierten Company took advantage of Wufang Village’s location in the suburbs of Shanghai to modernize agriculture and integrated three yellow peach industries. Under the professional guidance of the Shanghai Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the company optimized the planting type of yellow peaches. Regarding primary production, it promoted scientific and technological advances in agriculture and green agriculture by reducing the planting density, introducing modern agricultural machinery, and improving green ecological standards. Regarding secondary production, the industrial enterprises and agricultural processing industry in Wufang Village were modernized. To date, more than 30 yellow peach varieties have been developed, resulting in a relatively mature agricultural processing system. The Sierten Company promoted agricultural innovation and agricultural tourism, resulting in a relatively stable visitor flow.

In addition, the Sierten Company developed a new business model by improving the physical facilities, the land, and the agricultural industry and by focusing on the headquarters economy as a core business type of Wufang Village. After the reconstruction of the headquarters building, the Sierten Company relocated its headquarters to the village and attracted other enterprises to move their headquarters and benefit from the preferential tax policies. The tax generated by these enterprises was used to improve the rural collective economic organizations. Currently, large agricultural businesses have their headquarters in Wufang Village and serve a high-end market with their products and technology. Meanwhile, the agricultural production technology and marketing channels provide positive interactions with the yellow peach industry in Wufang Village. Other types of businesses in the building include the culture and art studio, the New Rural Innovation and Integration Center of Tongji University, the Rural Art Center of the Shanghai Academy of Arts, and the rural workstation of the China Academy of Arts. These businesses value the beautiful office environment and the rural farming heritage of Wufang village. In addition, agricultural tourism, catering, homestay, and other farm-supporting industries provide employment for staff living in the countryside.

5. Rural Reconstruction

5.1. Spatial Reconstruction: Optimization of the Production, Residential, and Natural Areas

After the rural operation, the urban capital was used to deal with fragmented agricultural land, idle residential land, and inefficient construction land in Wufang Village, optimizing the rural production, residential, and natural areas. The optimization of the agricultural production area was achieved by integrating fragmented cultivated land, forest areas, and garden spaces in the village. The rural non-agricultural production area in Wufang Village was optimized by acquiring low-efficiency industrial land in the village and constructing a modern production park area. In addition, Wufang Village replaced the scattered homesteads by building centralized resettlement houses. The whole village was transformed while retaining its rural characteristics, such as old trees, trails, and rivers, improving the rural living environment. Wufang Village also conserved natural areas by improving the residential areas and performing river management.

5.2. Economic Restructuring: Industrial Upgrading and Income Sharing

Before the urban-rural capital flow, Wufang Village was a traditional agricultural village characterized by small-scale agriculture. Families were involved in yellow peach cultivation, and the collective economy was relatively weak. The rural operation resulted in the economic reconstruction of Wufang Village, the optimization and upgrade of the industrial structure, and improved income distribution.

Land-use optimization and industrial development due to urban capital changed rural production and management. Industrial development replaced small-scale agriculture. After the influx of urban capital into the agricultural production of Wufang village, the scattered yellow peach orchards were aggregated, and ecological agriculture principles were implemented by agricultural enterprises. In addition, a complete rural industrial system was established. Wufang Village built a modern agricultural industrial park focused on yellow peaches and upgraded the agricultural industrial system by implementing landscape improvements, extending the industrial chain, and incorporating leisure experiences. A tertiary industry was developed focused on the headquarters economy to stabilize the rural economy because the agricultural industry can be affected by uncontrollable factors, such as natural disasters and market fluctuations.

Wufang Village has changed its income distribution to include rent, stock funds, and salaries to improve the villagers’ living conditions and ensure their interest in village operations. The villagers and the village collective lease their houses to obtain rental income, and the contract includes a reasonable price increase mechanism. After the village collective has signed contracts leasing the land to the company, it will obtain the land contract fee, part of which is the villagers’ equity income through dividends. The company provides industrial jobs to the villagers who have lost their land so that they earn reasonable wages.

5.3. Social Reconstruction: Reshaping the Rural Population Structure and Lifestyle

Before the urban-rural capital flow, Wufang Village was a traditional agricultural village. Most villagers made a living by farming, and many young people that could provide labor left the area for cities. The remaining villagers were aging and had limited education. The rural operation in Wufang Village improved the infrastructure, such as water and electricity, and created a rural landscape similar to the new Jiangnan water town. Apartments were built to attract talent, and an industrial community for young people was established. Industrial development and capital investment have provided diverse employment opportunities for young people, including agricultural science and technology, cultural and tourism services, and enterprise management, creating conditions for attracting talent to the countryside. Wufang Village has attracted more than 100 young people to work in existing enterprises and start businesses. The rapid growth of the migrant population, mainly young and middle-aged people, has changed the population structure of Wufang Village and reversed the trend of population aging. These migrants are more educated than local people, changing the education structure. Since the land-use optimization utilized idle land, the influx of migrants has not displaced the local villagers. The coexistence of migrants and local villagers has diversified the population of Wufang Village. The operating company of Wufang Village regularly organizes villagers’ integration day to bring together migrants and local villagers through various communication activities.

The villagers’ lifestyles have been changed by industrial development and a change in the social structure. This change is reflected in many aspects, such as a change from self-sufficiency to agricultural industrial workers and living in scattered villages to living in concentrated residential areas. In addition, a characteristic change in the lifestyle in Wufang Village is a change from a home-based pension to a socialized pension. For example, old-age services are being provided, and idle tool houses that were used to store farm tools in the village have been transformed into nursing homes and apartments equipped with old-age care facilities and are rented to the elderly living alone at a low price. The elderly are provided with basic health and safety tests and a variety of recreational activities, substantially improving the quality of life of the elderly in the village.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.1.1. Case Highlights and Development Implications

We believe that the administrative power to control part of the rural operation power is a highlight of this case because it is conducive to the development of the rural areas in the direction that most people expect, rather than a small number of enterprises. Specifically, in Wufang Village, the local government has defined the spatial pattern and utilization of land through planning, which is a limited means to guide and restrict urban industrial and commercial capital and prohibits them from “predatory” development of rural land. In addition, the town company (Oriental Wonderland Group) is the leader of Wufang Village operation. This company actually represents the will of the town government of Qingcun, and prevents a weak position of the town collective in market competition. This measure is a good example of rural areas in China and many developing countries in the world because the marketization level of these villages is low. If urban capital is allowed to be invested in rural areas without restriction, it is likely to cause damage to rural interests.

Another key measure of urban industrial and commercial capital is to establish a comprehensive industrial system in Wufang Village that allows local villagers to share the benefits of economic development. We can observe this phenomenon in China and many countries in the world, i.e., tourism [36,37] and real estate development [38,39] are common approaches for enterprises to carry out rural development. However, large-scale development of rural tourism may destroy the rural landscape and traditional culture [40], and there is also a risk of homogenization. Land use in rural China is strictly managed by the state. Although some scholars call for further institutional innovation in the reform of the rural land system [41], large-scale real estate development activities are still not allowed at this stage. The choice of Wufang Village is to develop the yellow peach industry and headquarters economy at the same time. Rural tourism is only one link in the yellow peach industrial chain. Its industrial development path can be followed by those villages without tourism resources. Diversified industries can stabilize the rural economic structure [42]. In addition, enterprises in Wufang Village employ local villagers, pay them dividends, and provide elderly care services. These are all wise measures because they can help enterprises gain the trust and support of local villagers. Conflict between the local population and the newcomers is universal [43,44]. When the locals think their interests are not considered, they will prevent the actions of outsiders, which is unfavorable to rural operations.

The case study of Wufang Village suggests the following two points should be considered. First, we should clarify the role of the government and the market during rural development and improve development efficiency by not deviating from the original intention. Similar to Wufang Village, most rural areas near cities in China have undergone rural construction by focusing on improving the physical environment. Previous revitalization efforts of rural areas by the government were inefficient. The government should transfer the implementation of rural development to the market to improve the resource allocation efficiency to enable the use of large amounts of assets for rural development. In addition, we should rely on administrative power for land use optimization and use planning tools to standardize the decision-making for using urban industrial and commercial capital for land commercialization and change the development from private interests to collective interests. We should maintain a balance between economic and social benefits during rural operations to achieve rural revitalization. It is crucial to take advantage of rural resources and improve economic benefits using market-oriented thinking. However, social benefits, such as social security, equitable distribution, and ecological protection cannot be ignored. Only by striking a balance between economic and social benefits can the sustainable development of rural areas be improved during rural restructuring.

6.1.2. Rural Operation Can Improve Rural Resilience

The international consensus is to focus on resilience during rural transformation and reconstruction, especially since many villages worldwide are becoming more vulnerable after reconstruction [45]. Rural resilience requires a smooth flow of the rural system elements, strong adaptability, and creativity to withstand shocks and disturbances [46,47]. Our case study results for Wufang Village showed that the urban-rural capital flow resulted in a resilient community after reconstruction.

One reason is that the rural operation was market oriented. There is a consensus that the market can allocate resources flexibly and efficiently [48]. The market mechanism can also play a positive role in rural areas, such as improving the value of land [49] and increasing the income of villagers [50]. At the same time, it can quickly respond to changes in the market environment and policies. For example, when China implemented the policy reform of homesteads and rural collective construction land, many enterprises were keen to seize the opportunity and conduct commercial activities in rural areas [51]. These were conducive to enhancing the adaptability of rural areas to internal and external changes and stimulating the vitality and creativity of rural areas.

On the other hand, rural operation differs from traditional actions, such as infrastructure construction, cultivated land protection, and improvements in residential areas because it is comprehensive and represents the optimization of rural land, industry, and social structure. Rural areas are complex regional systems [52], and transformation actions aimed at a certain aspect of rural areas are difficult to implement. Therefore, rural areas should be optimized and improved while maintaining the integrity of the structure and function of the rural, regional system without disturbing the balance of the rural system to reach a new stable state by whole village reconstruction.

6.1.3. Differences between Rural Operation and Rural Gentrification

In the late 20th century, many middle-class people in Britain and the United States moved to the suburbs, resulting in rural gentrification [53,54]. Urban middle- and high-income groups move to rural areas, causing the villagers to move out, thus changing the social structure of rural areas [55,56]. Since these people have urban aesthetic preferences and long for a comfortable rural life, they actively invest in pollution control, building repair, and transformation to beautify the local landscape and environment, promoting the development of the tertiary industry [42]. Rural gentrification also causes spatial, economic, and social reconstruction of rural areas. Some villages in China have adopted the western approach to rural reconstruction through gentrification. However, too much emphasis is placed on obtaining rapid economic returns. The villagers are required to move out and rent their houses to foreign enterprises to attract capital into rural areas to develop the tourism industry, leading to social stratification, cultural fracture in rural areas, and industrial homogeneity [57]. The rural operation of Wufang Village differs from the western-type rural gentrification. The urban industrial and commercial capital is invested in rural areas under the guidance of the government to benefit local operations rather than achieving a “one-time buyout” of rural resources by capital. The goal of rural operations is to achieve mutual benefits and win-win results through capital appreciation and sustainable rural development. The villagers’ interests are protected, and their land rights are not removed. This strategy also prevents the displacement of villagers caused by rural gentrification. Therefore, we believe that the proposed rural operation strategy is a rural transformation path that is more in line with China’s national conditions.

6.1.4. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

The methodological limitation of this study is that a single case study does not represent the diverse reconstruction paths of rural China. In addition, qualitative case studies must rely on policy documents and interviews to provide key insights into the relationship between urban-rural capital flow, rural operation, and rural transformation. However, rural restructuring is a complex systematic project, and we ignored the impact of other factors on this process, such as national policies and regulations [58] and villagers’ participation [59]. Moreover, it is difficult to quantify the economic impact of these processes using a case study. Therefore, we plan to conduct a multi-case comparative study in the future to clarify the path framework of rural reconstruction in China’s big cities and quantify the comprehensive social and economic impact of urban-rural capital flow on the rural, regional system.

6.2. Conclusions

China’s rural areas are being transformed and reconstructed to achieve rural revitalization and urban-rural integrated development. Rural areas around metropolises are facing various opportunities and challenges. Their location facilitates the attraction of urban industrial and commercial capital. Therefore, this study established a theoretical analysis framework of urban-rural capital flow and rural reconstruction and conducted an empirical study using Wufang Village in Shanghai as an example. The results show that the proposed approach is effective in promoting rural transformation and reconstruction in China’s metropolitan cities and guiding the flow of urban industrial and commercial capital to rural areas.

The case study of Wufang Village showed that the urban-rural capital flow resulted in land-use transformation, improvements in the rural environment, and changes in land ownership. The rural operation of Wufang Village can be divided into three aspects: (a) Land commercialization was implemented by the government and dominated by the market. (b) Industrial development should consider the development of primary, secondary, and tertiary industries and promote industrial integration to create a rural industrial chain. (c) By integrating urban industrial and commercial capital into rural areas through platform-based capital investment, Wufang Village obtained sufficient financial support for various types of rural development and construction activities while controlling the direction of rural development, achieving a win-win situation for the company and rural areas. Finally, the spatial, economic, and social reconstruction of Wufang Village was achieved by land-use optimization, capital investment, and industrial development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and X.L.; methodology, X.Z., X.L. and X.G.; formal analysis, X.Z., X.L. and X.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and X.G.; funding acquisition, X.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 72074143 and the Science and Technology Innovation Plan of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission, project number 22230750500.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number. 72074143) and the Science and Technology Innovation Plan of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (Project Number. 22230750500). The authors wish to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful contributions to this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders played no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zou, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. Quantitative identification and spatial analysis of land use ecological-production-living functions in rural areas on China’s southeast coast. Habitat Int. 2020, 100, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrosio, G.; Magnani, N.; Osti, G. A mild rural gentrification driven by tourism and second homes. Cases from Italy. Sociol. Urbana E Rural. 2019, 119, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabiyik, C.; Loopmans, M. Seasonal gentrification and its (dis)contents: Exploring the temporalities of rural change in a Turkish small town. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D. Contradictions in policy making for urbanization and economic development: Planning in Papua New Guinea. Cities. 1991, 8, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, X. Improving the Framework for Analyzing Community Resilience to Understand Rural Revitalization Pathways in China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Z.; Wu, F.; Deng, X. Understanding Rural Restructuring in China: The Impact of Changes in Labor and Capital Productivity on Domestic Agricultural Production and Trade. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Goodwin, M. Conceptualizing countryside change: From post-Fordism to rural structured coherence. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1992, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T. Rural geography trend report: The social and political bases of rural restructuring. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonts, M.; Atherley, K. Rural restructuring and the changing geography of competitive sport. Aust. Geogr. 2005, 36, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, P. Urban-rural migration, tourism entrepreneurs and rural restructuring in Spain. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 4, 349–371. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, R.; Carte, L. Community participatory appraisal in migration research: Connecting neoliberalism, rural restructuring and mobility. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2014, 39, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cissiers, E.; Cornelius, S. The greation of rural child-friendly spaces: A spatial planning perspective. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 925–939. [Google Scholar]

- Shortall, S. Gendered agricultural and rural restructuring: A case study of Northern Ireland. Sociol. Rural 2010, 42, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, N.S.; Azharianfar, S. Urban-Rural Reciprocal Interaction Potential to Develop Weekly Markets and Regional Development in Iran. Habitat Int. 2017, 61, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.; Whitehead, I. Local rural product as a ’relic’ spatial strategy in globalised rural spaces: Evidence from County Clare (Ireland). J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabánková, M.; Boháčková, I. Conditions of sustainable development in the Czech Republic in compliance with the recommendation of the European Commission. Agric. Econ. 2009, 55, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. Spatial Pattern Simulation of Land Use Based on FLUS Model Under Ecological Protection: A Case Study of Hengyang City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10458. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Wei, Z. Rural Elite Flow and Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Social Transformation Period. J. Landsc. Res. 2017, 05, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Z. Farmers’ Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Rural Industrial Land Changes and Their Influencing Factors: Evidences from the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, China. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 440–451. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Xu, Q.; Long, H. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Optimized Reconstruction Analysis of China’s Rural Settlements During the Process of Rapid Urbanization. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, G.; Yang, Q.; Yan, Y. Rural Settlement Reconstruction Integrating Land Suitability and Individual Difference Factors: A Case Study of Pingba Village, China. Land 2022, 11, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. China’s rural transformation under the Link Policy: A case study from Ezhou. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başaran, A.; Sakary, I. Rural gentrification in the North Aege an countryside (Turkey). Iconarp Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2018, 6, 99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in China: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. Betting on the strong: Local government resource allocation in China’s poverty counties. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 36, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Gao, Q. Community-Based Welfare Targeting and Political Elite Capture: Evidence from Rural China. World Dev. 2019, 115, 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Bao, S.; Sun, T. Participation of Social Capital in Rural Revitalization and Agricultural and Rural Modernization: Based on Extended Williamson Economic Governance Analysis framework. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2022, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, G. Geographies of agriculture: Globalization, restructuring and sustainability. Pearson Educ. Ltd. 2005, 29, 803–805. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, S.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, D.; Qu, Y. Rural restructuring at village level under rapid urbanization in metropolitan suburbs of China and its implications for innovations in land use policy. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Tian, H. Industrial and Commercial Capital Moving to Agriculture, Factor Allocation and Agricultural Production Efficiency. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2018, 9, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, G.; Feng, L.; Ye, W. Smith’s rent gap theory and evolution of gentrification. Geogr. Res. 2012, 14, 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, S.; Long, H. Rural restructuring in China: Theory, approaches and research prospect. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Poverty alleviation through land assetization and its implications for rural revitalization in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105418. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Cai, J.; Sliuzas, R. Agro-tourism enterprises as a form of multi-functional urban agriculture for peri-urban development in China. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 374–385. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, A.; Felsenstein, D. Support for rural tourism: Does it make a difference? Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S. From Local State Corporatism to Land Revenue Regime: Urbanization and the Recent Transition of Rural Industry in China. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud, H.B. The Land Development Corporation: A System for Selling Rural Real Estate. Real Estate Econ. 2010, 6, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelli, F. Is rural rural tourism-induced built-up growth a threat for the sustainability of rural areas? The case study of Tuscany. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. China’s Initiatives Towards Rural Land System Reform. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104567. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Orallo, R. Land, industry and finance: Rural elites and economic diversification in a time of crisis. The case of Catalonia (1875–1905). Rev. Hist. Ind. 2018, 27, 43–79. [Google Scholar]

- Solana-Solana, M. Rural gentrification in Catalonia, Spain: A case study of migration, social change and conflicts in the Empordanet area. Geoforum 2010, 41, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrobek-Rozanska, M.; Zadwomy, D. Can urban sprawl lead to urban people governing rural areas? Evidence from the Dywity Commune, Poland. Cities 2016, 59, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Maarten, L. Land Dispossession, Rural Gentrification and Displacement: Blurring the Rural-Urban Boundary in Chengdu, China. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M. Resilience: A conceptual lens for rural studies? Geogr. Compass 2013, 7, 597–610. [Google Scholar]

- XianJia, W.; Wen, X. Market mechanism of water resources allocation and its efficiency. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2001, 32, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, L.; Cao, G.; Yan, Y.; Yu, W. Urban land marketization in China: Central policy, local initiative, and market mechanism. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara, A. Considering Structural Relationship between Market Mechanism and Life Strategy in Rural Society. J. Rural Stud. 1994, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, C.; Hoegerlf, Y.; Brucoli, M. A holistic resilience framework development for rural power systems in emerging economies. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural Land System Reforms in China: History, Issues, Measures and Prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, J. Challenging peripheralising discourses: Using evolutionary economic geography and, complex systems theory to connect new regional knowledges within the periphery—ScienceDirect. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 73, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. Rural gentrification and the processes of class colonisation. J. Rural Stud. 1993, 9, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ghose, R. Big sky or big sprawl? Rural gentrification and the changing cultural landscape of Missoula, Montana. Urban Geogr. 2004, 25, 528–549. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, L. Agriculture and inequalities Gentrification in a Scottish Parish. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y. Holistic Gentrification and the Recreation of Rurality: The New Wave of Rural Gentrification in Chengdu, China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, Y. Targeted Poverty Alleviation and Land Policy Innovation: Some Practice and Policy Implications from China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Eddie, C.; Zhou, J.; Lang, W.; Xun, T. Rural Revitalization in China: Land-Use Optimization through the Practice of Place-making. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).