Abstract

The withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights is a major initiative in China’s current rural land reform, and it is of great importance in promoting the rural revitalization and urbanization strategy. The Chinese government encourages farmers to withdraw from their residential bases in an orderly manner to effectively revitalize land resources. The study aimed to explore the key factors that influenced the decision of farmers to withdraw from their rural residential lands in different contexts and proposed suggestions for related policy reforms. Firstly, the study proposed hypotheses based on the theories of the hierarchy of needs and peasant household behavior, combined with the current situation of the research area. Then taking the withdrawal policies and practical experiences of some pilot areas in China as a reference. Secondly, the study set five exit modes for withdrawing the right to use rural residential land and programmed four dimensions of the factors that affected those decisions to form the questionnaire. A total of 533 valid questionnaires were obtained by using scenario simulation. Thirdly, the study analyzed the influential factors of the exit decisions of the different modes using the multivariate ordered logistic regression model and tested the hypotheses using the abovementioned methods. The results showed the following: (1) the willingness of the rural residents to accept the different exit modes for withdrawing their rural residential land-use rights substantially varied. The rural residents prioritized the exit modes that were beneficial to their future housing and other social security. (2) There were some differences in the influencing factors on the exit decisions. Among the four-dimensional factors, the “rural residents’ cognitive characteristics” had a substantial impact on the decisions for withdrawing rural residential land-use rights. Based on the research conclusions, the study proposed some targeted policy suggestions: steadily promoting the construction of a high-quality social security system, promoting classified governance policies based on the diversified needs of farmers and strengthening the individual cognition of relocated farmers to withdraw from homesteads. In addition, a more scientific and reasonable land governance system needs to be established.

1. Introduction

Since the era of the planned economy, China has formed a dual structure that separates rural areas from urban areas. The huge gap in the economic and social development between urban and rural areas is related to the lack of a breakthrough in this dual structure. To promote the integrated development of urban and rural areas, the reform of the factor market of the urban and rural dual structure must be deepened, among which the land factor market is the key point of the reform. At present, the phenomenon of the idle and inefficient utilization of rural residential land is common [1]. In recent years, on the premise of protecting the legitimate rights and interests of farmers, the reasonable and orderly promotion of the withdrawal from rural residential land and the active and effective promotion of the integration of urban and rural areas have become important issues in the implementation of the current rural revitalization and urbanization strategy. The Chinese government has always attached great importance to the reform of the rural land property rights system, which is deeply embedded in the national modernization development strategy [2]. The amendment to the Land Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China came into effect on 1 January 2020. The new law explicitly allows rural residents who have settled in cities to voluntarily withdraw from their rural residential lands with compensation in accordance with the law, and it encourages rural collective economic organizations and their members to make use of the idle rural residential lands. The state has continuously promulgated relevant policy documents on the withdrawal of the right to use rural residential land, providing strong institutional support for the smooth implementation of its pilot project.

Due to the implementation of land privatization, farmers in other countries can freely dispose of their land. Land can be traded as commodities. Take Europe and the United States as an example, most modern housing systems in Europe and the United States divide land into two categories according to its nature: public housing and private housing. Private housing is purchased by individuals and owned by individuals. After purchase, individuals can live, empty or build their own houses for sale, while public housing is funded by governments at all levels and provided to low-income families by means of housing subsidy policy, economic support, half rent and half buy, in order to improve the housing penetration rate and social equity, and incorporate public housing into the national welfare system [3]. Therefore, many international scholars pay more attention to rural land property rights, rural residential land circulation and rural land consolidation. In recent years, the international academic community has paid more and more attention to China’s rural residential land. The articles are mainly published in Land and other publications [4]. In view of the particularity and complexity of rural residential land governance, the existing international research is mainly reflected in the following three aspects. First, the institutional study of rural residential land governance [5,6,7], mainly discussing the historical evolution, internal logic and future policy orientation of the rural residential land system. The second is the research on the idle rural residential land and its revitalization and utilization strategy [2,8,9], mainly aimed at the problems faced in the practice of the revitalization of the rural residential land and putting forward countermeasures. The third is the research on farmers’ willingness and behavior to withdraw from the rural residential land in the residential land renovation [10,11,12]. These studies show that farmers’ willingness to withdraw from the residential land is not only affected by individual factors at the micro level, but also by risk factors at the macro level such as organization, system and society. International research has made a lot of important research progress on rural residential land renovation. These studies have responded to many theoretical and practical problems in the rural residential land reform, which not only helps to clarify the important background, practical significance and future direction of the rural residential land system reform but also helps to understand the achievements and challenges of rural residential land renovation.

For China, rural homestead has its particularity. It refers to the land that is owned by the rural collective and has the right to use it for building houses, which is acquired by individual Chinese citizens according to law [13]. From this definition, it includes three main meanings: first, the homestead is rural collective ownership in terms of land system; second, Chinese citizens have the right to use land; third, the use of homestead is mainly limited to building houses. As the withdrawal of the right to use rural residential bases is still at the stage of pilot exploration, Chinese scholars mainly carry out relevant academic research on the practical exploration, mechanism construction and behavioral willingness of the withdrawal of the right to use rural residential bases. In terms of practical exploration, some researchers have concentrated on the existing modes of withdrawing residential land-use rights, such as the exchange of rural residential land for urban housing in Tianjin, land coupon trading in Chongqing, the residential land replacement pattern in Shanghai and the two-for-two mode in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province [14,15,16,17]. A majority of researchers aim to promote the intensive and economical use of land and try to provide a basis for the rational planning of rural construction [10]. In terms of the mechanism construction, scholars mainly focus on the mechanism of rural housing land construction, the mechanism of residential land expropriation and the game mechanism for the stakeholders involved in the withdrawal from residential land [18,19,20], which have important implications for the construction of a perfect mechanism for the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights. In the matter of behavioral intentions, scholars have explored the factors that influence farmers’ behavior in the withdrawal from rural residential land based on field research [21,22]. The main focus has been on the difference in the willingness of rural residents to withdraw their rural residential land-use rights in areas with different levels of economic development [23,24], as well as on the internal and external influences on the willingness [12,25,26,27]. However, a key issue that has generally been overlooked in the existing studies on exit intentions is the lack of specific exit model scenarios in the questionnaire, which has resulted in a lack of insight into the exact rural residential land exit decisions and influencing factors of farm households.

In the reality that the rural residential land is owned by the village collective, and the use right is owned by the farmer, the decision to promote the smooth exit of rural residents from their residential lands should be a voluntary one by the farmer and should fully guarantee their interests and realize the value goals of order, fairness and efficiency. Therefore, it is necessary to have a full understanding of rural residents’ land withdrawal decisions and the influencing factors, and to then combine the comprehensive value of the residential land and various influencing factors to design differential compensation methods for diverse types of residential land withdrawal behaviors in different regions [28]. The rural residential land reform in Suzhou City, Anhui Province, has achieved certain results. Sixian County, under its jurisdiction, is listed as a pilot county for the national rural residential land system reform in 2020. Based on the macro background of China’s urban–rural-integration development and rural residential land system reform, we selected Suzhou City in Anhui Province as the research area, and we chose adult rural residents as the research subject. We obtained the multidimensional information that affected the exit decisions of the rural residents though face-to-face investigation. We used scenario simulation to explain the exit modes from rural residential land-use rights set by the questionnaire to the rural residents. Then, we analyzed the survey data to explore the preferences of the rural residents for the different exit modes and the relevant factors that affected their decision-making. The economic and social development of the selected regions in this study is within the national median, which is representative to some extent.

According to relevant surveys, the average idle rate of residential land in China is 10.7%, and the idle rate of residential land in individual villages is higher than 30% [29]. With the continuous deepening of urbanization, the idleness of rural residential land will be further aggravated. In view of the problem of idle homestead, the country has carried out pilot reform of homestead in many regions and has achieved certain results. However, the effective withdrawal of rural homestead in China still faces many obstacles and risks, such as the differentiation of farmers’ financial needs, the threat of farmers’ housing rights and interests, and the insufficient use of power after the withdrawal of homestead. The research results of this paper have certain reference value for the withdrawal practice of rural homestead use right in China, which is conducive to avoiding the waste and inefficient use of land resources. Due to the well-defined land property rights system in Western countries, the concept of residential land withdrawal does not exist, but it can provide some reference for similar research, such as that on the land market and land acquisition compensation.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs expresses human needs using a five-level pyramidal model. The needs, from low to high, are as follows: physiological needs; security needs; love needs; respect needs; self-actualization needs [30]. These five levels evolve in an overlapping and interdependent manner, and it is only when the lower-level needs are largely realized that humans move on to the higher levels. According to Maslow, all human beings are potentially motivated to satisfy the physiological needs that support endosmosis, which are followed by the need for security, which is the search for a predictable and ordered world to survive in. Following security is the need for love, which involves affection, belonging, loving and being loved. When the above needs are met, the need for respect, (i.e., the desire for a stable well-grounded highly respected self-appraisal) comes to the fore. Finally, there is the need for self-actualization: a person must become what he/she wants to be happy and achieve self-actualization [31].

For farming households, there are likewise different levels of needs. Taking the withdrawal of the residential land as a starting point, the subsequent physiological needs of farmers mainly include housing security and economic issues. On the one hand, after withdrawal from the residential land, the need for security is reflected in the need for social security services, such as retirement, medical care and employment. The need for love, on the other hand, is the need for farmers to acquire emotional expressions after the withdrawal from the residential land, such as local sentiment and the remembrance of the homeland. The need for respect and self-fulfillment mainly refers to the fairness shown in the expression of the farmers’ wishes in the process of residential land withdrawal, as well as the fair and reasonable distribution of welfare compensation for property rights. Therefore, the most likely primary motivation for a farmer who wants to withdraw from the ownership of his or her residential land is physiological needs rather than any others. Physiological needs are the main reason for the behavioral decisions of farmers, and the other levels of needs are subordinate.

In China, although village collectives actually own the residential lands and rural residents do not have complete land property rights, the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China clearly stipulates that Chinese rural residents have the right to use their residential lands, and to build houses and ancillary facilities on the rural residential land. Moreover, the right to use rural residential land can be obtained and transferred according to land management laws and relevant national regulations. The paid withdrawal of the right to use rural residential land in China is actually a process of wealth redistribution. In addition, Lin, an American scholar, once visited China for a field investigation. He believes that, when farmers exercise their land property rights, their own interests are not effectively guaranteed [32]. Although Loren Brandt proposes that the land property rights in rural China are quite heterogeneous in different villages, the essence of residential land withdrawal is the same: the transfer of property rights by property subjects [33]. Therefore, it is necessary to pay full attention to the basic core interests of rural residents in the process of transferring property rights. To sum up, due to the high identity and welfare characteristics of the property rights of residential land and the basic functions of housing and welfare protection derived from them, farmers, as the key demand subjects in the sharing of the proceeds from the withdrawal from residential land, are more concerned about basic protection, such as housing and welfare, when they give up their original property rights.

In light of the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

In terms of the exit mode for the withdrawal of the right to use residential lands, rural residents prioritize the right to use their residential lands in exchange for future housing and other types of social security.

2.2. Theory of Peasant Household Behavior

The withdrawal of the right to use rural residential land is a behavioral decision of farmers. There are three schools of study on the theory of peasant household behavior in the academic field: the Real Economy School, the Formal Economy School and the Historical School [34], which correspond to the rational man hypothesis in economics. The Real Economy School corresponds to risk minimization and believes that the small-scale peasant economy is a self-sufficient economy and that small-scale farmers are typical risk avoiders. Their production purpose is to meet the needs of families, and their pursuit is to minimize the risks of production and life. The Formal Economic School advocates complete rationality, believing that farmers are rational individuals who make reasonable decisions based on existing resources and their own needs or preferences in order to achieve Pareto optimization and maximize their interests [35]. The Historical School emphasizes bounded rationality, and it believes that farmers make decisions based on the maximization of interests and minimization of risks, that they are restricted by internal environmental factors, the external environment, and other uncertain factors, and that it is difficult for them to make completely rational decisions.

The behavioral choice of farmers is the decisive factor that affects the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights, and it is also the most complex factor. Not only do farmers weigh the advantages and disadvantages and make rational decisions, but they also make perceptual choices under the influence of their own conditions and the surrounding environment. In fact, farmers are rational people who decide on the allocation of the production factors and seek to maximize their own interests based on their resource endowments and own constraints [36]. Therefore, when analyzing the willingness of farmers to leave their residential lands, we need to consider internal factors, such as their personal characteristics and family situations [37], as well as external factors, such as the resource endowments of their residential lands. For example, from the perspective of farmers’ personal characteristics, farmers with higher levels of education and nonfarming skills are more likely to have access to jobs and stable incomes in cities, and they are therefore more inclined to make the decision to exit [38]. From the perspective of family characteristics, farmers with small household labor forces and low total incomes have higher livelihood pressures. For them, the rural residential land is an important housing and welfare security, and exit decisions need to be carefully considered; thus, they are more likely to choose to not withdraw from their residential land tenures. From the perspective of resource endowment, in cases where the size of the residential land is higher and the economic development of the region is better, farmers are more likely to insist on the decision to not withdraw their use rights in view of the higher standard of living and economic benefits in the future.

Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

The key factors that influence the decisions of rural residents to withdraw their rural residential land-use rights are their personal and family characteristics and the characteristics of the resource endowments of their residential lands.

3. Research Methods and Data Materials

3.1. Research Methods

3.1.1. Scenario Analysis

Scenario analysis is also referred to as the script description method. The use of a scenario is the core of this method. As for the definition of this word, Kahn and Wiener understand “scenario” as describing the assumed development process of some events, which is conducive to taking some positive measures for future changes [39]. The future is diverse, all possible scenarios are possible in the future, and the path that leads to the outcome of the same scenario is not the only one. The description of the possible future and the way to achieve this future constitutes a scenario. According to the relevant policies and regulations on the withdrawal from rural residential bases at the national and local levels, while taking into account the withdrawal practices of typical and representative pilot areas in China, where the withdrawal of the right to use rural residential bases was carried out from 2015 to 2022 (including Jinjiang City, Yujiang District, Yingtan City, Yiwu City, etc.), we proposed five exit modes for the withdrawal from rural residential land use for the scenario simulation in this study: the “Urban Building Replacement Mode”; “Collective Farm Replacement Mode”; “One-time Monetary Compensation Mode”; “Land-pension Mode”; “Implementing Rural Residential Land Use Right Shareholding” (Table 1). Prior to the research, the research team conducted research simulation exercises in groups to prepare the response strategies in advance for the problems that might arise under the different scenarios in the research. During the survey, one-to-one surveys were conducted with randomly selected households, with the researcher first depicting each scenario in detail, and then guiding the respondents to imagine themselves in different scenarios based on different modes of withdrawing rural land-use rights. The respondents could choose “no”, “unclear” or “yes” to express their acceptance of the different scenarios. At the same time, the information worker took the researcher’s responses in the simulation as feedback. The information worker needed to be genuinely engaged and to honestly record the feedback, without adding his/her own subjective opinions to the record. We found that scenario analysis could help rural residents with lower education levels to make more accurate choices.

Table 1.

Comparison of exit modes for withdrawing rural residential land-use rights under different scenarios.

3.1.2. Model Setting for Analysis of Influencing Factors on Exit Decision

The commonly used logistic regression model mainly focuses on binary dependent variables. When the value of the dependent variables is more than two, the multicategory logistic regression model should be adopted [40]. The dependent variable in this paper is the decision-making regarding the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights, which is an ordered multiclassification variable. Therefore, we adopted the multiple-ordered logistic regression model to analyze the influencing factors of this decision-making under scenario simulation. The model construction process is as follows:

We divided the dependent variable (explained variable) in this paper into 3 categories with the following values: “unwilling”: 1; “unclear attitude”: 2; “Willing”: 3. The probabilities of the corresponding value levels were , , and . We fit two models for n independent variables (), as follows:

In the formula, is the probability at the corresponding exit decision level; is the characteristic factors of the respondents; and are the constants in the model; , , …, are the coefficients of the characteristic factors (independent variables) of the interviewees in the regression model, which can reflect the correlation degree and action direction between these factors and the exit decision.

3.2. Data Sources

In April 2022, we distributed a questionnaire survey and conducted interviews among rural residents in Suzhou, Anhui Province, in two towns and one district under the jurisdictions of four counties, for a total of 10 towns. We selected the towns, villages, and respondents according to the principle of random distribution, and we conducted one-to-one interviews to ensure the quality and effective recovery of the questionnaire. In this survey, we issued a total of 539 questionnaires. Excluding 6 invalid questionnaires, we collected a total of 533 valid questionnaires, with an effective rate of 98.89%. We present the basic characteristics of the interviewees in Table 2.

Table 2.

Basic characteristics of samples.

3.3. Data Processing and Variable Description

We took the decision-making regarding the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights as the dependent variable, and we could therefore express it in different scenarios: (urban building replacement mode); (collective farm replacement mode); (one-time monetary compensation model); (land-pension mode); (mode of implementing rural residential land-use right shareholding). When rural residents make the decision to exit, they evaluate the expected benefits and risks brought on by the corresponding exit mode according to their family conditions, the external environment and other factors. When the rural residents perceive that the decision will bring higher expected gains and lower expected risks, they are more willing to accept it. On the contrary, they will reject the decision if it is faced with high risks. The net income from the withdrawal from rural residential land depends on two parts: the income (which may include compensation for the land exit, expected nonagricultural income, etc.) and the cost (which may include the agricultural operation income, nonagricultural employment migration cost, etc.). As the compensation standards for withdrawing the right to use rural residential land are relatively consistent in the same regions, the main reason for the income difference lies in the different resource endowments of the rural households. In addition, the differences in the expected nonfarming income and nonfarming employment migration costs among rural residents are mainly caused by the differences in their individual and family characteristics. Furthermore, the behavior of rural residents is also affected by their subjective cognition. For example, when rural residents have a low cognition of the importance of the residential land or believe that they are able to avoid the risk of exit, they may have a higher willingness to withdraw. Referring to the relevant studies by scholars such as Jia Gao, Mingzi Gao, and Da Wei on rural residents’ perceptions of property rights, policy perceptions and risk perception characteristics, in this study, we measured the cognitive characteristics of the rural residents through four dimensions: (1) perceptions of the importance of the residential land; (2) perceptions of the residential land exit policy; (3) the degree of expected risk to the household after the residential land exit; (4) the ability to avoid the expected risk to the household after the residential land exit.

According to the above theoretical analysis and considering the availability and accuracy of the data in the field research, referring to previous Chinese scholars’ relevant research on variable settings, we divided the influencing factors for the decision to exit into four dimensions and a total of 16 factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Variable descriptions.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Interviewee Decision Making Regarding Withdrawal of Rural Residential Land-Use Rights under Different Scenarios

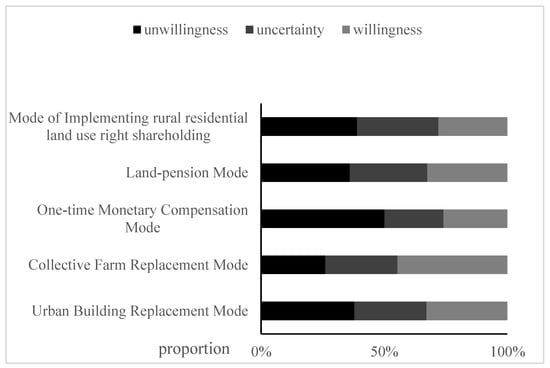

According to the statistical results of the exit decisions in different scenarios (Figure 1), the respondents’ acceptance/willingness rate was the highest in the scenario of the “Collective Farm Replacement Mode”, in which 44.7% of the samples expressed their “willingness” to withdraw their rights to use rural residential land. In the scenario of the “Urban Building Replacement Mode”, 32.8% of the respondents said “yes”. In the scenario of the “land-pension Mode”, 32.5% of the respondents said “yes”. In the scenario of the “Mode of Implementing Rural Residential Land Use Right Shareholding”, 28% of the respondents chose “willing”. The respondents were the least willing to accept the “One-time Monetary Compensation Model”: only 25.9% of the sample chose “yes”.

Figure 1.

Exit willingness in different scenarios.

In light of the above analysis, considering the stability of their living conditions, the rural residents were more inclined to choose the “Collective Farm Replacement Model”, and the “Urban Building Replacement Mode” was the second choice, which indicated that the housing problem was still the primary consideration of the rural residents after the withdrawal of their rural residential land-use rights. Although the “Urban Building Replacement Mode” provides urban directional resettlement housing for the rural residents who have made exit decisions, considering the livelihood risk in the future, the rural residents had doubts about living in cities and towns. Consequently, the acceptance rate of the “Urban Building Replacement Mode” was still lower than that of the “Collective Farm Replacement Mode”. Based on the reality of the current urban–rural dual pension system, the rural residents started by improving their own pension levels. Relatively speaking, they had a relatively high acceptance of the “Land-pension Mode”, which was only 0.3% lower than the “Urban Building Replacement Mode”. The willingness of the rural residents to choose the “Implementing Rural Residential Land Use Right Shareholding” was relatively low, which, to some extent, indicated that the rural residents lacked confidence in the operation ability of the village collective economy. The rural residents were less confident in their own abilities to operate large funds. As a result, they had the lowest acceptance of the “One-time Monetary Compensation Model”.

To further explain the response distribution of Figure 1, we conducted a group statistical test and independent sample t-test on the data, and we present the results in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Group statistics.

Table 5.

Independent sample t-test.

According to Table 4, the average willingness of the farmers in the residential security and other social security groups was 2.03, and the standard deviation was 0.836. The willingness of the farmers in the other groups was 1.82, and the standard deviation was 0.827.

According to Table 5, the P value of the independent sample t-test was 0.000, which passes the significance test at the 1% level, which indicates that there were significant differences in the farmers’ willingness for different situations. Based on the results shown in Table 4, the willingness of the farmers in the residential security and other social security groups was higher than that of those in the other groups. According to the above statistical analysis results, we verified the correctness of the first hypothesis (H1), which states that, in terms of the choice of exit mode for the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights, rural residents prioritize the exit mode that is beneficial to their future housing and other social security.

4.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Decision Making Regarding Withdrawal of Rural Residential Land-Use Rights under Scenario Simulation

4.2.1. Single-Factor Chi-Square Test for Influencing Factors on Exit Decision

We used the statistical software SPSS 22.0 for the cross-analysis of the dependent and independent variables of the influencing factors, and we used a chi-square () test to judge whether the relationships were significant. We conducted the k-chi-square test according to the comparison results of the probability (P) value of the observed statistical value and statistical significance level (α). If the probability (P) of the observed chi-square value was <α, then we considered the relationship between the variables significant. In this study, we set the test standard as α = 0.05. We performed a single-factor chi-square test on the 16 independent variables of the four-dimensional features and the exit decisions of the 5 scenario modes. We present the results in Table 6.

Table 6.

Single-factor chi-square test results of influencing factors on decision to withdraw rural residential land-use rights (values in table are p values).

In this study, we used the chi-square test to select the variables for the multivariate ordered logistic regression model, and we conducted the multicollinearity test. We used the tolerance and variance expansion factor to measure the linear correlation strength between these variables to ensure the stability and accuracy of the model.

In the process of collecting the questionnaires, we collected as many valid samples as possible, and we also considered the selection of the respondents from a more scientific and reasonable perspective, which, on the one hand, improved the accuracy of the questionnaire and, on the other hand, guaranteed the stability of the results.

4.2.2. Multiple Ordered Logistic Regression Analysis of Influencing Factors on Exit Decision

According to the results of the single-factor chi-square test, gender, age, education level, total number of family members and residential land area had no significant influence on the withdrawal decision in the five scenarios. In this paper, we incorporated the variables with significant influences identified by the single-factor chi-square test into the multivariate ordered logistic regression model for the regression analysis, and we conducted the multicollinearity test for these five groups of explanatory variables. To ensure the stability and accuracy of the model, we used the tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) to measure the intensity of the linear correlation between these variables [41]. In previous studies, researchers have demonstrated that a tolerance less than 0.2 or VIF ≥ 10 could be considered as a sign of multiple linear existences [42]. According to the multicollinearity test results, the tolerance of the explanatory variables in each group was greater than 0.2, and the VIF was less than 10. Therefore, there was no significant collinearity between the explanatory variables in each group, which could be further analyzed by the regression model. We obtained the quantitative relationship between each influencing factor and exit decision according to the constructed multivariate ordered logistic regression model. We present the −2 logarithmic likelihood values and chi-square values of the likelihood ratio of the model in Table 7. The significance P value of each model was 0, which was significant at the 1% statistical level, which indicates that the results obtained by the model are meaningful. According to the results of the parallel line test, the probability (P) value was greater than the significance level of 0.05, which indicates that there was no significant difference in the slopes between the models, which proved that we selected the appropriate connection function (Logit) [43].

Table 7.

Estimated results of multiple ordered logistic regression model.

According to the multivariate ordered logistic regression analysis of the influencing factors of the exit decision, the independent variables, such as the “health degree”, “family type”, “urban housing”, “last year’s total family income”, and “building situation on residential land”, had no significant influence on the exit decisions in the five scenarios. On the contrary, among the 16 independent variables of the four dimensions, each of the variables of the “cognitive characteristics of rural residents” dimension had a significant impact on the exit decision, while only the two independent variables “the number of labor force” and “rural type” in the other three dimensions had a significant impact on the exit decision (Table 7).

4.2.3. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Exit Decision under Different Scenarios

(1) From the analysis of the influence of the “rural residents’ personal characteristics” on the decision to withdraw rural residential land-use rights, and according to the regression results, gender, age, education level and health status had no significant impacts on this exit decision.

(2) In terms of the impact of the “family characteristics of rural residents” on the decision to withdraw rural residential land-use rights, according to the estimation result of multiple ordered logistic regression model, “the number of the household labor force” had a significant impact on the exit decision of the “urban building replacement model” at the 10% level. The results also reflected that compared with the option of “4 or more people”, the smaller the labor force, the less likely the residents were to accept the “urban building replacement model”. In addition, “the number of the household labor force” had no significant influence on the other four exit-mode decisions. Therefore, the reason that the families with smaller labor forces were less likely to accept the “urban building replacement model” was that they had fewer employable people and were more worried about future urban life with higher living costs.

(3) In terms of the influence of the “resource endowment characteristics of rural residents” on the exit decision, the “rural type” to “one-time monetary compensation model” exit decision had a significant effect at the level of 5%. According to the results, the typical rural residents were more willing to accept the “one-time monetary compensation model” than the rural residents in the rural–urban fringe, which further indicated that the residents who lived in neighboring cities attached more importance to the asset value of land and houses. In contrast, they were less willing to withdraw their rural residential land-use rights with the “one-time monetary compensation mode”.

(4) In light of the analysis of the “cognitive characteristics of rural residents” on the influence of the exit decision regarding the right to use rural residential land, we drew conclusions: firstly, the exit decisions of the “Urban Buildings Replacement Mode”, “Collective Farm Displacement Mode”, and “Land-pension Mode” were significantly impacted by “the rural residents’ understanding of the importance of residential land”, with impact levels of 5%, 1%, and 5%, respectively. According to the results, the rural residents with a better understanding of the policies had a higher willingness to quit. In the survey, we also found that the rural residents generally had relatively low numbers of years of education and limited access to government policies, which affected the exit decisions and resulted in their vague understanding of the relevant exit policies. Secondly, the rural residents’ understanding of the exit policies had a significant impact on the exit decisions of the “urban building replacement model”, “collective farm replacement model”, “one-time monetary compensation model” and “land-based pension model”, with impact levels of 5%, 1%, 10%, and 10%, respectively. According to the results, the rural residents with a better understanding of the policies had a higher willingness to quit. In the survey, we also found that the rural residents generally had relatively low numbers of years of education and limited access to government policies, which affected the exit decisions and resulted in their vague understanding of the relevant exit policies. Thirdly, “the degree of expected risk” had a significant impact on the exit decisions of the “Urban Building Replacement Mode”, “Land-based Pension Mode” and “Mode of Implementing Rural Residential Land Use Right Shareholding”. With “relatively high” as the reference, the rural residents with relatively low perceived risk degrees had higher exit intentions. The rural residents’ decision to withdraw their rural residential land-use rights was the result of rational decision-making. When the exit decision brought higher expected benefits and lower expected risks, the rural residents’ acceptance/willingness was higher, and vice versa. Fourthly, the “respondents’ perception of risk avoidance ability” had a significant impact on the five types of exit decisions. The rural residents who believed that they had the ability to avoid the exit risk were more inclined to make an exit decision. Risk cognition generally refers to an individual’s subjective judgment and understanding of the risk degree of the risk situation [44]. However, as rational behavioral decision-making individuals, the rural residents chose to retain the right to use their residential lands in order to maintain stability when they believed that they were unable to completely avoid risks.

According to the above statistical analysis results, the judgment of H2 is not accurate enough. The “rural residents’ personal characteristics” had no significant influence on the exit decisions of the five established exit modes. The “cognitive characteristics of rural residents” had the most significant influence on the decision to withdraw rural residential land-use rights.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

In this study, we proposed research hypotheses based on the theories of land property rights and peasant household behavior. We compiled the questionnaire based on the practical experience of the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights in some pilot areas in China and the relevant theoretical research results to survey the respondents in a scenario simulation to obtain basic data. After the statistical analysis of the basic data, we used the multivariate ordered logistic regression model to further analyze the influence of the four dimension factors on the different exit-mode decisions so as to verify the research hypotheses. Returning to the research questions, the findings and arguments are as follows:

(1) The willingness of the rural residents to accept different exit modes for the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights greatly varied. According to the research results of this paper, rural residents were more inclined to exchange houses with land. At the same time, they were more willing to accept the “Collective Farm Replacement Mode” compared with the “Urban Building Replacement Mode” based on factors such as living habits and future living costs. In addition, based on the reality of the current urban–rural dual pension system, the acceptance of the “Land-pension Mode” was relatively high. The high acceptance rate of the above three modes indicated that the rural residents had strong demands for basic security, such as housing and pensions. By contrast, the low acceptance rate of the “Mode of Implementing Rural Residential Land Use Right Shareholding” and “One-time Monetary Compensation Mode” indicated that the rural residents lacked confidence in both the “village collective” and their individual capital operation abilities. Therefore, the optimal path for the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights is to accelerate the integrated development of urban and rural areas, improve the extension of the urban infrastructure to rural areas, promote the coverage of public services and social programs in rural areas and motivate the exit reform of rural residential land-use rights by the “Collective Farm Replacement Mode”. In terms of spatial geography, county towns and villages should be closely connected to further promote the urban economy and farmers’ employment, which could not only prevent the long-distance migration of farmers for work but also enable them to take into account agricultural production and provide a labor-force guarantee for agricultural modernization.

(2) There were some differences in the influencing factors on the decision to withdraw rural residential land-use rights. According to the results, the “rural residents’ characteristics” had no significant influence on the exit decisions of the various scenarios. The factors “family characteristics of rural residents” and “resource endowment characteristics of rural residents” had a certain influence on the decision-making behavior of the rural residents. Among them, the factor “the number of the household labor force” affected the degree of the rural residents’ concern regarding their future livelihoods in the city. In other words, for the vast majority of the rural residents, the fundamental obstacle to urbanization was not just the ability to afford one-off housing costs in cities, but also the ability to obtain stable and decent jobs with basic social security that match the daily cost of living in cities. The “Rural type” had a significant impact on the exit decision of the “One-time Monetary Compensation Mode” at a 5% level. The residents who lived near cities attached more importance to the asset value of land and houses, which was consistent with the prediction. The “cognitive characteristics of rural residents” had a significant impact on the exit decisions of different scenarios. Among them, “the perception of risk avoidance ability” had a significant impact on the five kinds of exit decisions. Based on this, we argue that the social security of rural homesteaders should not be stripped when their nonagricultural jobs are unstable before they can obtain stable and dignified long-term jobs. Therefore, it is necessary to deeply understand and prudently treat the residential social security attribute of the current vast traditional rural residential land system, which must be considered as the basic starting point to analyze the withdrawal of rural residential land-use rights.

According to the conclusions, we recommend the following policies:

(1) We recommend adherence to the strategic thinking of integrated urban and rural development and the steady promotion of the construction of a high-quality social security system. Policy actors are both the continuing force of policy stability and the mediators of major policy changes. If policy actors are patient and persistent enough, then they will be able to maintain the optimal policy in the Nash equilibrium of infinite repeated games [45]. Although China is now vigorously promoting the rural revitalization and urbanization strategy, rural residential land still has the social security attribute for the vast traditional agricultural areas. Therefore, this basic attribute must be fully considered when formulating relevant policies, highlighting the main position of farmers, adhering to the farmers’ perspective, ensuring the basic protection of farmers’ housing and economy, further improving the construction of rural infrastructure, and improving the public service system of employment, pensions, medical care and education. Meanwhile, the strategic thinking of urban–rural-integration development should be established to promote rural residential land reform. In the long and complicated urbanization process, the withdrawal of the right to use rural residential land in traditional agricultural areas should be solved step by step in a planned way. Urban and rural governance must be based on the spirit of practical work, historical patience and strategic focus. Rural migrant workers and urbanization have created a large number of idle rural residential lands. At present, the Chinese government has not established a high-level social security system for the majority of rural residents, including residential social security; thus, the current rural residential land reform should not be too hasty, and the government should not blindly promote the relocation of rural residential land reclamation, operation, and transfer.

(2) Based on the diversified needs of farmers, we are steadily promoting a policy of classification and management. The diversity and complexity of different household residential lands, the vulnerability of household economic sources and the gradual development of rural urbanization should be fully recognized. Based on the diversity of the livelihoods of rural residents and multiple utility values, such as the land value, expected value of the property and social security value, diversified compensation methods should be formulated to meet the actual needs of heterogeneous rural residents, and dynamic compensation standard promotion mechanisms should be constructed according to the level of social and economic development [46]. For example, for farmers who can permanently withdraw from their residential lands, such as those who have settled in cities, localities can raise funds through multiple channels to financially compensate them. For farmers who can temporarily withdraw from their residential lands, such as those who go out to work, they can be encouraged to make compound use of their residential lands, such as by developing rural industries, such as rural tourism, catering and bed and breakfasts, and the primary processing of agricultural products, and they can be financially compensated to a certain extent.

(3) We recommend strengthening the individual perceptions of the relocated farmers towards the residential land exit. On the one hand, the cognition of the farmers regarding the policies and risks should be improved. Village cadres should be organized to go into villages and households to explain the policy on the withdrawal of residential bases so that farmers can make more rational decisions on the withdrawal of their homes; at the same time, farmers who have already withdrawn their homes should be organized to publicize their experiences and the welfare benefits after withdrawal to give full play to their leading role and demonstrate a good example. On the other hand, we focus on strengthening the farmers’ antirisk capacities. The targeted training of employment skills and the expansion of social networks based on professional and interest ties will enhance the human and social capital of farmers and strengthen their endogenous risk resistance. In addition, the establishment of a sound mechanism and system for the withdrawal of residential land-use rights is an important prerequisite for promoting the withdrawal of rural residential land. A quantitative evaluation index system of the risk grade and impact degree of withdrawing rural residential land-use rights should be established, and a perfect risk evaluation mechanism should be constructed. According to the principle of risk minimization and benefit maximization, corresponding preventive measures should be formulated for different risk types. Meanwhile, the risk-control and avoidance mechanisms of exit decisions must be established by strengthening the vocational skill training of rural residents and improving the urban and rural social security system. When formulating specific policies, it is necessary to pay attention to fair compensation, find standards to protect both sides and find a balance and proportionality between social and individual interests. At the same time, the transparency of the process needs to be ensured while ensuring that rural residents obtain fair compensation in the process of withdrawing their rights to use residential lands [47]. In addition, as an important part of the institutional environment, the legal system is the basis for defining, protecting and enforcing property rights [48]. If the initial division of property rights is clear enough and guaranteed by a complete legal system, then the actors can divide, transfer and consolidate property rights through negotiation and litigation for a reasonable distribution of income [49,50]. Therefore, clear property rights and a sound legal system can resolve conflicts in income distribution.

Based on field survey data from 533 farmers in Suzhou City, Anhui Province, we investigated the willingness of farmers to quit their rural house bases, grouped the sample farmers according to five different scenarios and analyzed the key influencing factors on the farmers’ willingness and decision to quit their rural house bases under different scenarios. To some extent, this study bridges the gaps in previous studies. The practical significance of this study is to provide a feasible reform path to achieve a better matching between the rural residential land exit mode and the multi-level needs of farmers and to provide decision-making reference for the formulation of rural residential land exit policy under the background of rural revitalization. However, it does have certain limitations, and future researchers should consider the following three areas for further study: (1) future researchers could explore the interrelationships between the variables based on specific scenarios, thus providing visual data support for an in-depth analysis of the internal logic of farmers’ exit decisions. (2) The field survey conducted in this study used real-life farmers as the research target, which ensured the relevance of the results. However, due to the high subjectivity of the scenario hypothesis, coupled with the high demand for scenario data, logic and causality, the whole research process requires a high level of competence from the researcher and information recorder. Therefore, future researchers could consider conducting standardized field experiments. (3) The sample of farmers in this study were all from Eastern China, and future researchers could consider including samples from other regions of China to test the results of this study and to analyze regional differences in farmers’ willingness to exit from their rural residential lands.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W.; methodology, X.W.; validation, X.W. and J.K.; formal analysis, X.W.; resources, X.W. and J.K.; data curation, X.W. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W. and J.K.; supervision, J.K.; project administration, X.W.; acquisition of funding, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, (Grant No.71874192), the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China, (Grant No.19GLA006), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 2019ZDPY-RH02, 2020ZDPY0219).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained informed consent from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the first author.

Acknowledgments

First: we would like to express our deep gratitude to Xiaoshun Li and Jian Zhang of the School of Public Administration, China University of Mining and Technology, for their guidance. We would also like to express our appreciation to the anonymous reviewers for the insightful comments that improved this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Torre, A.; Ehrlich, M. Governance Structure of Rural Homestead Transfer in China: Government and/or Market? Land 2021, 10, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lo, K.; Zhang, P.; Guo, M. Reclaiming small to fill large: A novel approach to rural residential land consolidation in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Experience and Enlightenment of Public Rental Housing Construction in Europe and America. Social Science Front 2014, 225, 271–272. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Peng, W.; Huang, X.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q. Homestead management in China from the “separation of two rights” to the “separation of three rights”: Visualization and analysis of hot topics and trends by mapping knowledge domains of academic papers in China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, H. The Historical Evolution and Acquisition, Circulation and Withdrawal of Rural Homestead System in China. Adv. Land Manag. 2022, 2, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Tian, Y.; Zou, Y. A novel framework for rural homestead land transfer under collective ownership in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. Development and Utilization of Rural Idle Homesteads in the Context of Rural Revitalization—A Case Study of Leisure Agriculture. Asian Agric. Res. 2019, 11, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, Z. The Realistic Obstacles and Resolutive Path of Reusing the Idle Rural Homestead under the Strategy of Rural Revi-talization. J. Hohai Univ. (Philos. Socail Sci.) 2020, 22, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Z. Influencing factors of farmers’ willingness to withdraw from rural homesteads: A survey in zhejiang, China. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Sarker, N.I.; Sun, J. RETRACTED: Model of the influencing factors of the withdrawal from rural homesteads in China: Application of grounded theory method. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Liu, S. Factors influencing farmers’ willingness and behavior choices to withdraw from rural homesteads in China. Growth Chang. 2021, 53, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dictionary Editorial Office, Institute of Language Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Modern Chinese Dictionary; Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2012; Volume 6, p. 1633. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, A.L.L.C. Social Security, Expectation of the Non-agricultural Income and Decision-making Behavior of the Rural Residential Land Exit: Based on the Empirical Research on Developed Area of Jinshan District and Songjiang District in Shanghai. China Land Sci. 2016, 30, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.S.; Lin, W. Transforming rural housing land to farmland in Chongqing, China: The land coupon approach and farmers’ complaints. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Z. Influencing Factors and Policy Cohesion of Households’ Idle Homestead Exiting—From the Perspective of Be-havioral Economics. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 35, 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.H. The Circulation of Housing Land Use Right in the Past 70 Years Since the Founding of New China: Institutional Change, Current Dilemma and Reform Direction. China Rural. Econ. 2019, 6, 2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Qinglei, Z.; Guanghui, J.; Wenqiu, M.; Dingyang, Z.; Yanbo, Q.; Yuting, Y. Social security or profitability? Understanding multifunction of rural housing land from farmers’ needs: Spatial differentiation and formation mechanism—Based on a survey of 613 typical farmers in Pinggu District. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Land use policy as an instrument of rural resilience—The case of land withdrawal mechanism for rural homesteads in China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 87, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Lyu, P.; Cao, Y. Multi-party game and simulation in the withdrawal of rural homestead: Evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 13, 614–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jiang, J.; Yu, C.; Rodenbiker, J.; Jiang, Y. The endowment effect accompanying villagers’ withdrawal from rural homesteads: Field evidence from Chengdu, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yu, C.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Farmer Differentiation, Generational Differences and Farmers’ Behaviors to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: Evidence from Chengdu, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.L.; Liu, L. Ownership Consciousness, Resource Endowment and Homestead Withdrawal Intention. Probl. Agri-Cult. Econ. 2020, 3, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.F.; Zhu, X.H.; Chen, L.G. Rural Residents’ Willingness to Quit Homestead and Its Influencing Mechanism in Different Levels of Economic Development. Jiang Su Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, L. Does Cognition Matter? Applying the Push-pull-mooring Model to Chinese Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 2355–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ni, X.; Liang, Y. The Influence of External Environment Factors on Farmers’ Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homesteads: Evidence from Wuhan and Suizhou City in Central China. Land 2022, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Hou, L.; Jia, B.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Hou, X. Effect of Policy Cognition on the Intention of Villagers’ Withdrawal from Rural Homesteads. Land 2022, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Hu, B.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q. The structural and functional evolution of rural homesteads in mountainous areas: A case study of Sujiaying village in Yunnan province, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houkai, W.; Binxin, H.; Guoxiang, L.; Tongquan, S.; Lei, H. Rural Green Book: Analysis and Prediction of China’s Rural Economic Situation (2018–2019); Social Science Literature Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. A Dynamic Theory of Human Motivation; Howard Allen Publishers: London, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, K.A. Theory of Human Motivation by Abraham H. Maslow (1942). Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y. Rural Reforms and Agricultural Growth in China. Am. Econ. Rev. 1992, 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, L.; Huang, J.; Li, G. Lind Rights in Rural China: Fants, Fictions and Issues. China J. 2002, 67–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhixiang, M.; Shijun, D. Classification Method of Farmers’ Types Based on Farmers’ Theory and Its Application. China Rural. Econ. 2013, 4, 28–38. Available online: https://www-nssd-cn-s.webvpn.cumt.edu.cn:8118/html/1/156/159/index.html?lngId=46395832 (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Chen, M.Q.; Kuang, F.Y.; Lu, Y.F. Livelihood Capital Differentiation and Farmers’ Willingness to Homestead Circulation: Based on Empirical Analysis of Jiangxi Province. J. Agric. For. Econ. Manag. 2018, 1, 82–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Song, G.; Sun, X. Does labor migration affect rural land transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Fan, Z. The Analysis of the Rural Homestead Withdrawal Willingness and Its Influencing Factors Based on the Empirical Research of 1413 Famers from 6 Counties in Anhui Province. Comp. Econ. Soc. Syst. 2012, 2, 154–162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Chen, Y. The Compensatory Exit Mechanism of Farmers’ Homestead Transfer: Chongqing Case. Reform 2015, 10, 143–148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, H.; Wiener, A.J. The Year 2000: A Framework for Speculation on the Next 33 Years; Macmillan: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Nagaraj, K.K. Modeling Urban Growth with Geographically Weighted Multinomial Logistic Regression. Proc. Spie Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2008, 7144, 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, H.P.; Sun, Y.M. Factors Affecting Farmer’s Willingness and Mode of Farmland Usufruct Abandonment for Rural Households and Contractual Operation Right. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.C.; Guo, Z.G. Logistic Regression Model—Method and Application; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, D.Y. Study on the Effect of Economic Compensation of Cultivated land Protection in Grain-Production Dominated Zone; Henan Polytechnic University: Jiaozuo, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sitkin, S.B.; Weingart, L.R. Determinants of Risky Decision-making Behavior: A Test of the Mediating Role of Perceptions and Propensity. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1573–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scartascini, C.; Stein, E.; Tommasi, M. Political Institutions, Intertemporal Cooperation, and the Quality of Public Policies. J. Appl. Econ. 2013, 16, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokić, M.T.; Počuča, M. Acquisition of Agricultural Land. Economics of Agriculture. Ekon. Poljopr. 2016, 4, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.R. Government Land Acquisition in India: Changes After 120 Years. Real Estate Rev. 2015, 44, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzel, Y. Economic Analysis of Property Rights; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R.H. The problem of social cost. J. Law Econ. 1960, 3, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).