Socioecological Dynamics and Forest-Dependent Communities’ Wellbeing: The Case of Yasuní National Park, Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

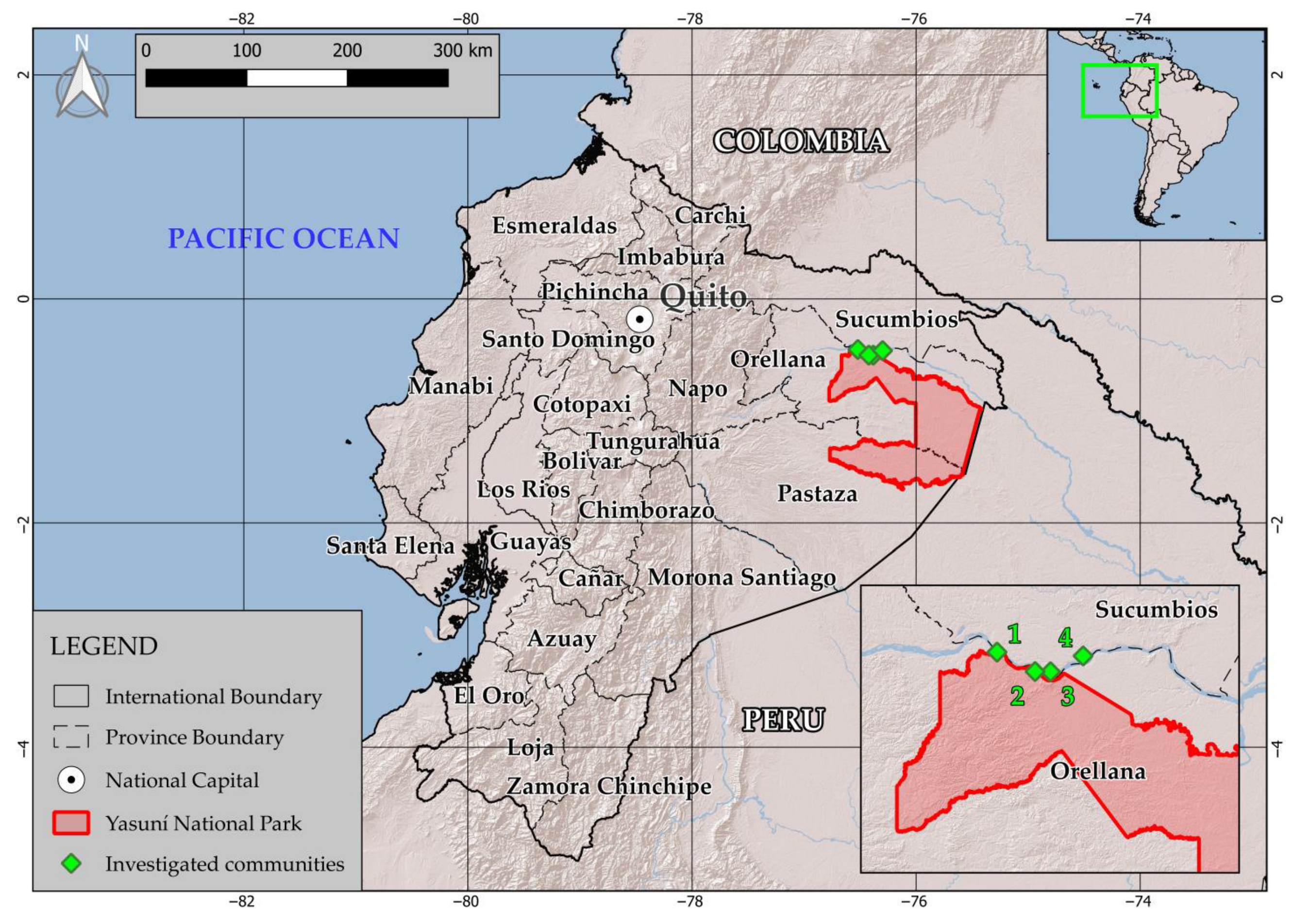

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

- Key respondent interviews with five persons: two members of the YNP management team, one local guide, and two local community leaders (El Pilche and Añangu), using a snowball sampling technique starting with an initial interview [52], which helped us to obtain an overview of the areas where the main PA management risks were identified. These interviews also helped in completing/confirming the items to be used within the survey in terms of ESs and the drivers that influence forest ecosystem changes.

- Semi-structured household interviews [53] with members of Añangu, Sani Isla, El Pilche, and Indillama communities were carried out to collect in-depth information about the nature of the forest–community relationship (including the most important ESs and their benefits for the community), dynamics, and change drivers of forest ecosystems. Purposeful sampling was used to ensure that relevant members of the community, in the context of the human–forest relationship, were included in the analysis. The following criteria had to be fulfilled to identify respondents who would suit the purpose of the study: (1) local engagement in practices related to forest ES use and (2) interviewed persons had to be old enough to be able to remember possible changes in forest ecosystem–community relationships. The structure of the interview was developed using the bibliographic research results and the key respondent interviews; it included the following sections: (1) background information, (2) the most important ESs and their influence on community wellbeing, (3) observed ecosystem changes and the identification of key drivers of change, and (4) questions about respondents’ environmental attitudes and options. A semi-structured interview guide is provided in Appendix A. A total number of 57 in-person interviews were held in June 2022. They were conducted face to face, and their duration varied between 40 min and 80 min. The interviewees were provided the option not to participate, to only answer some questions, or even to leave; informed consent was requested and received before starting the interviews. Data on respondents’ gender were not collected, nor was any information that would have helped in the identification of the respondents. The respondents were asked to refer to their entire household. Every interview was carried out by a team of two people (one researcher and one Kichwa guide/translator in the interviewee’s language of choice—Spanish or the local Kichwa dialect).

- Focus groups with community members [54] (5–10 participants, some of whom were also interviewed previously): These focus groups were organized immediately after the household interviews in each community, with the participation of community leaders. They served to clarify, verify, or conclude some debate from the individual interviews. The participants were selected by asking those members of the community who had already been interviewed to invite other people whom they considered to be important in the community. During the focus groups, among the topics included in the interview, only those with uncertainties were addressed. The participants were encouraged not to feel stressed and to try not to share answers that they considered responses to the desires of the interview team [24].

- A focus group with the YNP management team [24,55]: After completing the field visit, the YNP management team was contacted in order to discuss the preliminary findings of the secondary data collection and assessment process and the interviews with local communities. From the park management team, four members (two of them being key respondents) were invited to discuss the relationship between forest ESs—including their dynamic—and human wellbeing in and around YNP. The results of the focus group with the YNP management team members were recorded by the research team and used afterwards to validate and complete the results of the study.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

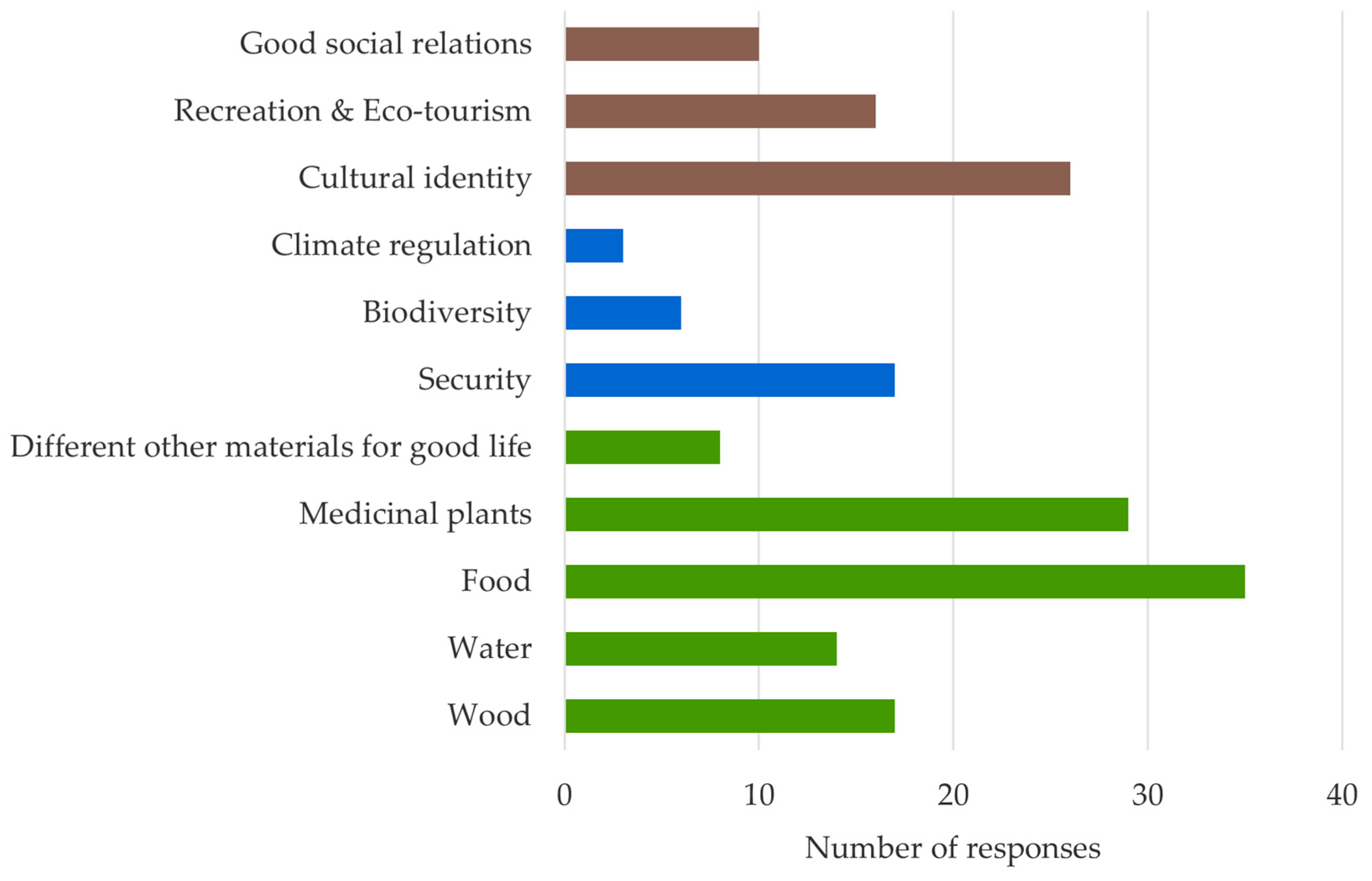

3.1. Ecosystem Services and Human Wellbeing

3.2. Drivers Influencing the Dynamics of the Sociological Systems

3.2.1. Identification of Drivers Influencing the Forest Ecosystem Dynamics

3.2.2. Description of Direct Drivers of Forest Ecosystem Disturbance

Oil Exploitation

Infrastructure Development

Small-Scale Agriculture

Invasive Species

Mining

Hunting and Poaching

Illegal Logging

Climate Change

3.2.3. Description of Indirect Drivers of Ecosystem Change

Land Governance and the Promotion of Extractive Activities by the State

Poverty and a Lack of Income Sources

Presence of Colonists in the Park’s Areas of Influence

Health and the Presence of New Diseases

Access to Education

Loss of Cultural Identity

Low Levels of Resources for the Control and Monitoring of YNP

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Criteria | Questions |

|---|---|

| Background information | What is your main occupation in the community? Please describe briefly what your work consists of in a regular day. For how long you have been working/living in the area? |

| The most important ES and its particular influence on community wellbeing | What benefits do you obtain from the forest surrounding your community? Why did you identify these benefits? How do you use the benefits you mentioned before? |

| Observed ecosystem changes and the identification of the key drivers of change | What changes have you observed in the forest ecosystems during your life? How do these changes affect your life and the lives of community members? What activities or causes determined the above-mentioned changes? |

| Questions about respondents’ environmental attitudes and opinions | Do you anticipate changes to the forest in the future? Please explain. If you were to decide on future governmental initiatives for the area management, what would these be? |

References

- Leverington, F.; Costa, K.L.; Pavese, H.; Lisle, A.; Hockings, M. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Dong, J.; Ellis, E.C.; Metternicht, G.; Qin, Y.; Song, X.P.; Löfqvist, S.; Garrett, R.D.; Jia, X.; Xiao, X. Post-2020 biodiversity framework challenged by cropland expansion in protected areas. Nat Sustain. 2023, 6, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Senio, R.A.; Crawford, C.L.; Wilcove, D.S. Gaps and weaknesses in the global protected area network safeguarding at-risk species. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg0288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP-WCMC; IUCN. Protected Planet. In The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) and World Database on Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (WD-OECM); UNEP-WCMC and IUCN: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Available online: www.protectedplanet.net (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Xu, W.; Pimm, S.L.; Du, A.; Su, Y.; Fan, X.; An, L.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, Z. Transforming Protected Area Management in China. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lü, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, M. Mapping critical natural capital at regional scale: Spatiotemporal variations and the effectiveness of priority conservation. Environ. Res. Let. 2020, 15, 124025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhai, D.; Huang, B. Implementation gaps affecting the quality of biodiversity conservation management: An ethnographic study of protected areas in Fujian Province, China. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 149, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, X.; Gleeson, T.; Serrano, D.; Zipper, S.; Jehn, F.; Rohde, M.M.; Abell, R.; Vigerstol, K.; Hartmann, A. Overlooked risks and opportunities in groundwatersheds of the world’s protected areas. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, F. Yasuní en el siglo XXI. El Estado ecuatoriano y la conservación de la Amazonía de Guillaume Fontaine e Iván Narváez (editores). Íconos—Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2013, 30, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Lü, Y.; Fu, B.; Zhang, X. Landscape pattern and ecosystem services are critical for protected areas’ contributions to sustainable development goals at regional scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laterra, P.; Barral, P.; Carmona, A.; Nahuelhual, L. Focusing Conservation Efforts on Ecosystem Service Supply May Increase Vulnerability of Socio-Ecological Systems. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Opportunities and barriers in the implementation of protected area management: A qualitative meta-analysis of case studies from European protected areas. Geogr. J. 2010, 177, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, L.; Bhattara, N.; Singh, B.; Prakash, G.; Kumar, A.; Windhorst, K. The Socioecological System of Parsa National Park: Insights for an Adaptive Management using the Ecosystem Approach; International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019; p. 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.A. General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hole, D.G.; Huntley, B.; Arinaitwe, J.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Collingham, Y.C.; Fishpool, L.D.C.; Pain, D.J.; Willis, S.G. Hacia un Marco de Manejo para Redes de Áreas Protegidas ante el Cambio Climático (Towards a Management Framework for Protected Area Networks in the Face of Climate Change). Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, G.S.M.; Rhodes, J.R. Protected Areas and Local Communities: An Inevitable Partnership toward Successful Conservation Strategies? Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torregroza, E.; Hernández, M.; Barraza, D.; Gómez, A.; Borja, F. Ecological Units for Ecosystem Management in the District of Cartagena (Colombia). Rev. UDCA Actual. Divulg. Cient. 2014, 17, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeshan, M.; Prusty, B.A.K.; Azeez, P.A. Protected area management and local access to natural resources: A change analysis of the villages neighboring a world heritage site, the Keoladeo National Park, India. Earth Perspect. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Adaptive management in transboundary protected areas: The Bialowieza National Park and Biosphere Reserve as a case study. Environ. Conserv. 2000, 27, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, F.; Ribadeneira, S.; Erazo-Mera, E.; Younes, N. Adaptive co-management of biodiversity in rural socio-ecological systems of Ecuador and Latin America. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, C.; Iveth, K.; Barba, D.M.P. International Climate Change Regime: Contruction of Common interests in the Yasuni ITT initiative and its link with Indigenous Peoples. Letras Verdes 2020, 27, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibisch, P.L.; Hobson, P. MARISCO Method: Adaptive MAnagement of Vulnerability and RISk at COnservation Sites. A Guidebook for Risk-Robust, Adaptive, and Ecosystem-Based Conservation Of Biodiversity; Centre for Economics and Ecosystem Management: Eberswalde, Germany, 2014; p. 195. ISBN 978-3-00-043244-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, N.I.; Coman, C.; Popa, B. Risk assessment and stakeholders mapping: On the way towards adaptive management for Yasuni National Park. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Bras. II For. Wood Ind. Agric. Food Eng. 2022, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finer, M.; Jenkins, C.N.; Pimm, S.L.; Keane, B.; Ross, C. Oil and gas projects in the western Amazon: Threats to wilderness, biodiversity, and indigenous peoples. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, M.S.; Finer, M.; Jenkins, C.N.; Kreft, H.; Cisneros-Heredia, D.F.; McCracken, S.F.; Pitman, N.C.A.; English, P.H.; Swing, K.; Villa, G.; et al. Global conservation significance of Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirira, D.; Greeney, H.; Omaca, C.; Baihua, O.; Killackey, R. Species richness and ethnozoological annotations on mammals at the Boanamo indigenous community, Waorani territory, Orellana and Pastaza provinces, Ecuador. Mammalia 2020, 84, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finer, M.; Vijay, V.; Ponce, F.; Jenkins, C.N.; Kahn, T.R. Ecuador’s Yasuni Biosphere Reserve: A brief modern history and conservation challenges. Environ. Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 034005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaiza, T.; Borja, M.O.; Nehren, U.; Gerold, G. Analysis of land management and legal arrangements in the Ecuadorian Northeastern Amazon as preconditiond for REDD+ implementation. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 83, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckerman, S.; Erickson, P.I.; Yost, J.; Regalado, J.; Jaramillo, L.; Sparks, C.; Iromenga, M.; Long, K. Life histories, blood revenge, and reproductive success among the Waorani of Ecuador. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8134–8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montilla Pacheco, A.D.J.; Guzmán Vera, D.E.; Pastrán Calles, F.R.; Mendoza Mejía, J.L. Tagaeris y Taromenanes: Dos grupos indígenas en aislamiento voluntario en el Parque Nacional Yasuní, Ecuador/Tagaeris and Taromenanes: Two indigenous groups in voluntary isolation in Yasuni National Park, Ecuador. Rev. Geogr. Venez. 2021, 62, 382. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador. Plan de Manejo Parque Nacional Yasuní (Yasuní National Park Management Plan); Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2011; p. 25. Available online: http://suiadoc.ambiente.gob.ec/documents/10179/242256/45+PLAN+DE+MANEJO+YASUNI.pdf/8da03f55-1880-4704-800e-d5167c80089c (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Corte Superior de Justicia de San Martin. Sentencia Expediente 00038-2021-0-2202-JM-CI-01. Peru. 2022. Available online: https://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/default/files/documents/Sentence%20from%20Mixed%20Court%20of%20Bellavista%20ordering%20titling%20of%20Kichwa%20ancestral%20territory%20%28Spanish%20only%29_0.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador. Actualización del Plan de Uso y Manejo Territorial de Seis Comunidades Kichwa. Pompeya, Río Indillama, Nueva Providencia, Añangu, Sani Isla y San Roque, Asentadasen la zona Noroccidental del Parque Nacional Yasuní (Updating of the territorial use and management plan of six Kichwa communities. Pompeya, Río Indillama, Nueva Providencia, Añangu, Sani Isla and San Roque, located in the northwestern zone of the Yasuní National Park); Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2016; p. 91.

- Jaramillo Carrión, M.I. Identificación de Posibles Impactos Medioambientales y Sociales del Turismo en Ecuador, Caso Concreto Parque Nacional Yasuní (Identification of Potential Environmental and Social Impacts of Tourism in Ecuador, Case Study Yasuní National Park). Obs. Medioambient. 2019, 22, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkert, S.R. Community-owned tourism and degrowth: A case study in the Kichwa Añangu Community. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1893–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Andino-Peñafiel, E.E.; Álvarez-García, J. Social Use through Tourism of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Amazonian Kichwa Nationality. Land 2023, 12, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, M. A Quién le Importan esas Vidas!: Un Reportaje Sobre la tala Ilegal en el Parque Nacional Yasuní (Who Cares About those Lives? A Report on Illegal Logging in Yasuní National Park); CICAME: Quito, Ecuador, 2007; p. 232. ISBN 9978319107. [Google Scholar]

- Stoessel, S.; Scarpacci, M. Disputes over Development and Territory: The Case of Yasuni-ITT during Ecuador’s Citizen Revolution/Disputas en torno al desarrollo y el territorio: El caso de Yasuní-ITT durante el Ecuador de la Revolución Ciudadana. Territorios 2021, 45, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecuyer, L.; White, R.M.; Schmook, B.; Lemay, V.; Calmé, S. The construction of feelings of justice in environmental management: An empirical study of multiple biodiversity conflicts in Calakmul, Mexico. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 213, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finer, M.; Moncel, R.; Jenkins, C.N. Leaving the oil under the Amazon: Ecuador’s Yasuni—ITT Initiative. Biotropica 2010, 42, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldekop, J.A.; Bebbington, A.J.; Truelove, N.K.; Holmes, G.; Villamarín, S.; Preziosi, R.F. Environmental Impacts and Scarcity Perception Influence Local Institutions in Indigenous Amazonian Kichwa Communities. Hum. Ecol. 2012, 40, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Gunter, S.; Acevedo-Cabra, R.; Knoke, T. Livelihood strategies, ethnicicity and rural income: The case of imigrant settlers and IP in the Ecuadorian Amazon. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 86, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckmüller, H.; Barriocanal, C.; Maneja, R.; Boada, M. Factors Affecting Traditional Medicinal Plant Knowledge of the Waorani, Ecuador. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, R.M.; Torres, B.; Cabrera-Torres, F.; Torres, E.; Diaz-Ambrona, C.G.H.; Pappalardo, S.E. Land use and Land cover changes in the diversity and life zone for uncontacted indigenous people: Deforestation in the Yasuni Biosphere Reserve, Ecuador. Forests 2021, 12, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicaiza Ortiz, C.D.; Logroño Vintimilla, W.; Chicaiza Ortiz, Á.; Núñez Chávez, W.; Ortiz Cañar, M.E. Environmental management strategies in Kichwa communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Cienc. Unemi 2022, 15, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador. Ecosistemas Parque Nacional Yasuní (Ecosystems Yasuní National Park). 2011. Available online: http://yasunitransparente.ambiente.gob.ec/ecosistemas1;jsessionid=0GsGhXwRqS1CHdUTtN6EFbhR (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador. Manual para la Gestión Operativa de las Áreas Protegidas de Ecuador (Manual for the Operational Management of Ecuador’s Protected Areas); Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2013; p. 2588. Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2014/02/04-Manual-para-la-Gestión-Operativa-de-las-Áreas-Protegidas-de-Ecuador.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Portalanza, D.; Barral, M.P.; Villa-Cox, G.; Ferreira-Estafanous, S.; Herrera, P.; Durigon, A.; Ferraz, S. Mapping ecosystem services in a rural landscape dominated by cacao crop: A case study for Los Rios province, Ecuador. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 107, 105593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, E.; Morales, M.; Cueva, E.; Utreras Bucheli, V.; Zapata-Ríos, G.; Toral, E.; Torres, J.; Prado, W.; Vargas Olalla, J. Oil industry, wild meat trade and roads: Indirect effects of oil extraction activities in a protected area in north-eastern Ecuador. Anim. Conserv. 2009, 12, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomakis, L. We protect the forest beings, and the forest beings protect us: Cultural resistance in the Ecuadorian Amazonia. Anthropol. Noteb. 2020, 26, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, T.A.B. Estimation on the basis of snowball samples: How to weight? Bull. Methodol. Sociol. 1992, 36, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Singly, F.; Blanchet, A.; Gotman, A.; Kaufmann, J.C. Ancheta și Metodele ei: Chestionarul, Interviul de Producere a Datelor, Interviul Comprehensiv; Polirom: Bucharest, Romania, 1998; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S. Focus group methodology: A review. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 1998, 1, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. The Focus Group Guidebook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; p. 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezina, B.I.; Ranaivoson, A.; Razafimanahaka, J.H.; Andriafidison, D.; Andrianirina, H.; Ahamadi, K.; Rabearivony, J.; Gardner, C.J. Understanding livelihoods for protected area management: Insights from Northern Madagascar. Conserv. Soc. 2020, 18, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar Tique, Y.P.; Escobedo, F.J.; Clerici, N. Community-Based Importance and Quantification of Ecosystem Services, Disservices, Drivers, and Neotropical Dry Forests in a Rural Colombian Municipality. Forests 2021, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrior, M.; Fanning, L.; Metaxas, A. Indigenous peoples and marine protected area governance: A Mi’kmaq and Atlantic Canada case study. Facets 2022, 7, 1298–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ouko, C.A.; Mulwa, R.; Kibugi, R.; Owur, M.A.; Zaehringer, J.G.; Oguge, N.O. Community perceptions of Ecosystem Services and the management of Mt. Marsabit Forest in Northern Kenia. Environments 2018, 5, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Wang, S.; Fu, B.; Zhang, L.; Fu, C.; Kanga, E.M. Balancing community livelihoods and biodiversity conservation of protected areas in East Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 33, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampheri, M.B.; Dube, T.; Shoko, C.; Marambanyika, T.; Dhau, I. Local community attitudes and perceptions towards benefits and challenges associated with biodiversity conservation in Blouberg Nature Reserve, South Africa. Afr. J. Ecol. 2022, 60, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, D.M.R.; Cevallos, D.; Gaoue, O.G.; Fadiman, M.G.; Hindle, T. Non-random medicinal plants selection in the kichwa community of the Ecuadorian Amazon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 246, 112220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia, R.M.; Torres, B.; Cayambe, J.; Ramos, N.; Luna, M.; Diaz-Ambrona, C.G.H. Sustanability Assessment of Smallholder Agroforestry Indigenous Farming in the Amazon: A case study of Ecuadorian Kichwas. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C. The riddle of leaving the oil in the soil—Ecuador’s Yasuní-ITT project from a discourse perspective. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 36, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, E.; Zapata-Ríos, G.; Utreras, V.; Strindberg, S.; Vargas, J. Controlling access to oil roads protects forest cover, but not wildlife communities: A case study from the rainforest of Yasuní Biosphere Reserve (Ecuador). Anim. Conserv. 2012, 16, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monitoring of Andean Amazon Project. Deforestación Petrolera en el Parque Nacional Yasuní, Amazonía Ecuatoriana (Oil deforestation in the Yasuní National Park, Ecuadorian Amazonia). Available online: https://maaproject.org/yasuni/ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Tapia-Armijos, M.F.; Homeier, J.; Draper Munt, D. Spatio-temporal analysis of the human footprint in South Ecuador: Influence of human pressure on ecosystems and effectiveness of protected areas. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 78, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, E. The fight for Yasuni. Science 2010, 330, 1170–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspari, M.; Clay, N.A.; Donoso, D.A.; Yanoviak, S.P. Sodium fertilization increases termites and enhances decomposition in an Amazonian forest. Ecology 2014, 95, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, T.; Zambonino, H. More than just trees—Animal species diversity and participatory forest monitoring in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2013, 9, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchart, L. Biodiversity, Global Governance of the Environment, and Indigenous Peoples. In Global Governance of the Environment, Indigenous Peoples and the Rights of Nature. Governance, Development, and Social Inclusion in Latin America; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, R.M.; Cayambe, J.; Schorsch, C.; Toulkeridis, T.; Barreto, D.; Poma, P.; Villegas, G. Multitemporal analysis as a Non-Invasive Technology Indicates a Rapid Change in Land Use in the Amazon. The case of ITT Oli Block. Environments 2022, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.E. Territorialization in a closing commodity frontier: The Yasuni rainforest of West Amazonia. J. Agrar. Change 2017, 18, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, S.F.; Forstner, M.R.J. Oil Road Effects on the Anuran Community of a High Canopy Tank Bromeliad (Aechmea zebrina) in the Upper Amazon Basin, Ecuador. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arellano, A. La Lucha de una Maestra y su Comunidad en Contra de una Carretera Ilegal que Atraviesa Territorio Ashéninka. 2023. Available online: https://es.mongabay.com/2023/02/la-lucha-de-una-maestra-y-su-comunidad-en-contra-de-una-carretera-ilegal-que-atraviesa-territorio-asheninka/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Cisneros Vidales, A.A.; Barriga Albuja, V.M. Oil Exploitation in Yasuni Biosphere Reserve. Impact on Ecuador’s Commitment with Sustainability. In Sustainable Development Research and Practice in Mexico and Selected Latin American Countries; World Sustainability Series; Leal Filho, W., Noyola-Cherpitel, R., Medellín-Milán, P., Ruiz Vargas, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño, D. Despidos Masivos en el Ministerio de Ambiente y Agua Ponen en Jaque a la Conservación en Ecuador (Massive Layoffs at Ministry of Environment and Water put Conservation at Risk in Ecuador). Mongabay. 2020. Available online: https://es.mongabay.com/2020/10/despidos-guardaparques-ecuador-riesgo-areas-protegidas/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Paz Cardona, A.J. Gold Mining Invades Remote Protected Area in Ecuador. 2022. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2022/12/gold-mining-invades-remote-protected-area-in-ecuador/ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Lu, F.E. The Common Property Regime of the Huaorani Indians of Ecuador: Implications and Challenges to Conservation. Hum. Ecol. 2001, 29, 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolín-López, R.; Jerez-Gómez, P.; Rengel-Rojas, S.B. Uncovering local communities’ motivational factors to partner with a nonprofit for social impact: A mixed-methods approach. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 564–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, C.; Bilsborrow, R.; Torres, B.; Griess, V. Agricultural land use among mestizo colonist and indigenous populations: Contrasting patterns in the Amazon. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero-Heredia, D.; Koeppen, N. Oil extraction, indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation, and genocide: The case of the Tagaeri and Taromenane peoples. Harv. Hum. Rights J. 2021, 34, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Pływaczewski, W.; Narodowska, J.; Duda, M. Assessing the Viability of Environmental Projects for a Crime Prevention-Inspired Culture of Lawfulness In Crime Prevention and Justice in 2030; Kury, H., Redo, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez-Trujillo, A.R.; Ortiz-Prado, E.; Rivera-Olivero, I.A.; Nenquimo, N.; Tapia, A.; Anderson, M.; Lozada, T.; Garcia-Bereguiain, M.A. COVID-19 outbreaks among isolated Amazonian indigenous people, Ecuador. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 478A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimerling, J. Indigenous peoples and the oil frontier in Amazonia: The case of Ecuador, ChevronTexaco, and Aguinda v Texaco. N. Y. Univ. J. Int. Law Politics 2006, 38, 413–664. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Barriga, A. Conciliating conservation and development in an Amazonian Biosphere Reserve, Ecuador? ERDE—J. Geogr. Soc. Berl. 2017, 148, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; Tierra-Tierra, N.P.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Álvarez-García, J. Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Amazonian Kichwa People. Land 2021, 10, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negru, C.; Gaibor, I.D.; Hălălișan, A.-F.; Popa, B. Management Effectiveness Assessment for Ecuador’s National Parks. Diversity 2020, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Benefits | Provisioning ES: wood, water, food, medicinal plants, and various other materials for sustenance Regulating and supporting ES: biodiversity, climate regulation, and security Cultural ES: good social relations, cultural identity, recreation, and ecotourism |

| Changes in the forest | Forest surface, forest species, and other forest features |

| Forest change drivers | Direct drivers: oil exploitation, infrastructure development, small-scale agriculture, invasive species, mining, hunting, illegal logging, and climate change Indirect drivers: land governance and the promotion of extractive activities, poverty and the lack of income sources, the presence of colonists in the park area, health and the presence of new diseases, the loss of cultural identity, access to education, and low levels of sources for control and monitoring The relationship between drivers The evolution of forest change drivers over time |

| Expectations | Opportunities and risks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dominguez-Gaibor, I.; Talpă, N.; Bularca, M.C.; Hălălișan, A.F.; Coman, C.; Popa, B. Socioecological Dynamics and Forest-Dependent Communities’ Wellbeing: The Case of Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. Land 2023, 12, 2141. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122141

Dominguez-Gaibor I, Talpă N, Bularca MC, Hălălișan AF, Coman C, Popa B. Socioecological Dynamics and Forest-Dependent Communities’ Wellbeing: The Case of Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. Land. 2023; 12(12):2141. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122141

Chicago/Turabian StyleDominguez-Gaibor, Isabel, Nicolae Talpă, Maria Cristina Bularca, Aureliu Florin Hălălișan, Claudiu Coman, and Bogdan Popa. 2023. "Socioecological Dynamics and Forest-Dependent Communities’ Wellbeing: The Case of Yasuní National Park, Ecuador" Land 12, no. 12: 2141. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122141

APA StyleDominguez-Gaibor, I., Talpă, N., Bularca, M. C., Hălălișan, A. F., Coman, C., & Popa, B. (2023). Socioecological Dynamics and Forest-Dependent Communities’ Wellbeing: The Case of Yasuní National Park, Ecuador. Land, 12(12), 2141. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122141