1. Introduction

This contribution will delve into the issue of the relationships between urban morphology, identity, memory, and reconstruction processes. The first point to be addressed is to find how, in reconstruction processes, some contexts manifest far greater fragility than other places.

This distinction, to be more precise, is not only about the obvious fragility imposed by volatile and precarious political scenarios: the Middle East seems to be back to the tensions of the early 2000s and looks like a powder keg continually ready to explode—as the re-arising of Israel–Palestine issues can only confirm; South America is continually experiencing coups d’états and potential ones; Africa is that opaque to obscure much of what is going on internally. But these experiences also concern the part of the world much closer to us: the war in Ukraine still continues and Donald Trump still remains indicted for the assaults on Capitol Hill. Precariousness is the substance of contemporary times. What makes some contexts more fragile, instead, is the capability and manner of reaction to difficulty, to destruction, to cataclysm, both from an economic point of view (who to rely on) and also in terms of expertise. What strategies can be used for reconstruction? Moreover, by observing the reconstruction process itself, we can easily notice that reconstruction does not have any specific modalities in itself: it is, no more and no less, that relationship with history that Rogers has identified since the 1950s as a pivotal theme for future architecture; the ability to find, within tradition and continuity, the courage to insert those discontinuous elements that combine architecture and time.

It is within this framework that the real problems of reconstruction emerge: if, as proposed, we consider that rebuilding within a destroyed city is, if not on a par with, at least similar to, building in a place already endowed with millenary culture and tradition, with which eyes do we look at contemporaneity? The recent passing of sociologist Marc Augé cannot but prompt some reflections on (super-)modernity and the standards we can encounter. If Augé speaks of non-places [

1] as essentially unrelated built elements—motorways, airports, large shopping centers—in opposition to what non-places support, i.e., the cities, which are understood as anthropological places, then it is the definitions of these two places that are of interest. The

anthropological place has the characteristic of being identitarian, relational, and historical. The

non-place, on the other hand, is simply not an anthropological place, it has an exclusively negative definition. And the characteristic of these non-places is that they are identical everywhere, in every part of the world—we could say a franchise—in which, nevertheless, people, in their conditions of hyper-stimulation of time and space, find comfort in spatial conformity and in finding themselves in schematic, summary, and perpetual symbols.

Is this not the trend In contemporary city-building processes, the use of technology at the expense of history? Efficiency at the expense of characterization? And is it not precisely the most precarious and fragile contexts that are most easily affected by these urban stereotypes without having the possibility of determining alternatives? The cities of the Arabic and Islamic world, so rich in settlement history, so full of meaning in wall conformations in opposition to the aridity of the desert, increasingly indulge in the paradigm of the entertainment park, the enclave, and the non-urban. If reversing this trend seems rather imprudent, it is nonetheless appropriate to provide a complementary way forward that reminds us of the importance of identity, history, and relationships in the important process towards modernity.

1.1. The City of Mosul

The city of Mosul fully represents those critical aspects of reconstruction listed above. Mosul is in fact the expression of a profoundly variable urban whole, especially in its residential parts, representing a diffuse urban pattern, anonymous and difficult to know due to the few studies conducted on it. The only monographic text on the city dates back to 1920, edited by the archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld [

2], and—as was typical at the time—he offers views that today seem dated from an architectural point of view: many studies of friezes and inscriptions; and considerable attention to the monuments, which are often reworked and adjusted in their physical consistency for an overall vision that can duet with archaeological insight. Some information is undoubtedly crucial to understand the city: the survey and positional study of certain monuments such as the Al Nouri Mosque, Nabi Djirdjis, Khydr Ilyas; the churches of Al Saa’a (known as Our Lady of the Clock and founded by the Dominicans in 1800) and Tahrat Maryam; the evidence of the wall perimeter and the reliability of the perimeter of the walls themselves, useful for defining the access roads to the city and its extension; and the presence of the Souq, overlooking the river, and of the citadel, initially a small island in the river separated by a system of canalization from the mainland and later united with the city.

The question that not only stays unanswered, but has never been opened, is the consistency of the city in the connections between these monumental epicenters and the remaining humble and collective space made up of

cul-de-sac streets, mansions with Iwans and Talars, and meandering shops culminating in Kahn and Qassirya. If the comparison is allowed in its provocative nature, the archaeological sentiment of the early 20th century has in fact created a

Paestum (with the monumental emergence of the temples) while forgetting

Pompeii (in which instead the vitality of the city is so visible), in an urban core that is, moreover, still perfectly usable and visitable without being forced into conjecture due to the sedimentation of abandonment. What remains of the city (

Figure 1) is visible to any non-specialist eye: the street layouts, the rough division into zones (or neighborhoods), the built mass density, and its elevation—all without ever having made a thorough study of its being a city beyond it being a built ensemble. With the need for reconstruction after the war events linked to the conflict with ISIS, the city of Mosul is an example of all those places that, in the absence of a solid typological awareness, are in danger of drifting and moving towards a sort of

Saudi construction (where the prefix

re- loses its value), bringing the concept of non-place up to its urban conglomerate status.

1.2. Literature Review and Theoretical Frame

In a scenario, as previously described, where much of the wartime destruction involved a widespread building heritage with no monumental status or character, the question that emerged was what preliminary operations could be preparatory to reconstruction. Interesting in order to understand the dimensions of the problem at a purely architectural and urban level are Ismaeel’s words [

3], when he states how the “assessment of cultural significance is still a new concept for Iraqi heritage community”, as much as the ability to plan. The result is therefore the difficulty of indicating guidelines for reconstruction at both architectural and urban levels.

This research delves into the lengthy bibliography on reconstruction, from the Venice Charter [

4] to the Dresden Declaration [

5] and its deliberate ambiguity on monumental reconstruction, but especially in the more recent ICOMOS [

6], UN [

7], and UNESCO [

8,

9] reports, which describe the need to improve preparedness for interventions and response to disasters, as much as to conduct a capacity building able to address in an efficient way the effort during reconstruction processes. The entire normative path just mentioned, if it can be defined in this way, is condensed in a punctual and precise manner by Abou Leila and Albarqawi, who attempt to identify a genealogy for conservation methodologies in Middle-eastern countries; according to the authors, there is no specifically “Arab school of heritage preservation” [

10], legitimizing even attempts such as this one to make European reflections useful to different contexts.

At present, much of the disciplinary scientific literature on the reconstruction of the Old City of Mosul mainly questions the set-up with which to divide the modalities of intervention: the difference between buildings and portions of the city, admitting the possibility of

replicas [

11] for the most significant and monumental buildings—an opportunity instead not contemplated for urban areas; or different degrees of intervention: revitalization (maintaining the identity as a formal element), renewal (updating the urban identity with the modification and integration of certain formal and functional specifications), and reform (a total rethinking of the city). This division proposed in [

12] is found in several places: respectively, Warsaw, Bilbao, and Tianjin; however, we overlook how much, in the end, the parallel with Mosul is only valid with the city of Warsaw, due to the selective, qualitative and quantitative datum of the damage done.

What emerges, beyond more or less complete attempts, is the identification of a non-immediate category of attention that goes beyond the needs imposed by the physical, economic, social, and political conditions of the destruction; and these are the

cultural needs [

13] of reconstruction, defined essentially as the inhabitant’s ability to identify with his or her urban context. The need for the cultural dimension to be a cornerstone of reconstruction projects and proposals is an aspect now shared by many scholars, although many of the modalities are not.

In this overview, the number of studies dealing exclusively with energetic and climate aspects of buildings has been deliberately omitted, as they are not extremely pertinent. Here, an attempt has been made to focus more closely on the issue of how the culture and identity of the city are

perceived and

transmitted, namely that of urban form. It is interesting to see how many studies propose an AI approach to the reconstruction of the city, producing generative models based on a grammar circumstantiated to the context [

14,

15]. These approaches, with regard to both facades and plans, provide not only analytical but also generative and design possibilities, which, however, are considered here as dangerous standardizing drifts of the design theme. As much as the machine of “contextualization” has excellent intentions in its presuppositions, the possibility of cyclically generating historical settings compatible with the context, in an operation paradoxically very similar to Paolo Portoghesi’s

Strada novissima at the Venice Biennale, cannot but appear borderline dystopian. However, the aspect that we would like to emphasize in all this repertoire of literature is how, for example, even the last two articles presented have their major focus in the form of the building: façade, floor plan, materials, height, etc. These are all components that are extracted (deduced, perhaps) from the city and found in the building, without then taking the reverse route and returning to the city. The study proposed here, on the other hand, wants to consider the

whole city as an artefact, composed of elements of varying entities, but which are within an urban logic. So, reconstruction is intended as a comprehensive project in which architecture and the city are the two extremes of a dialogic process, avoiding only-deductive types of approach.

The question that is asked more specifically and, if allowed, concretely, however, is: what elements should be retrieved in order to create a reliable knowledge base for reconstruction when the traces are all but erased?

If the material of construction is the body of architecture, it is in fact a mutable material due to physical degradation, destruction, and replacement, so that the various manipulations that may have occurred throughout history necessarily undermine the idea of being able to identify an original material to be preserved. Therefore, the form, the figure of architecture, can only be the expression of a system of figurative values of a certain historical period, and therefore can only be an input for a free imagination and reinterpretation. If figure and substance are the canonical elements of mimesis in architecture, can formal reproduction have a value of authenticity?

It is therefore suggested to include in the study of the city a perspective that investigates certain atemporal, non-individual components that can effectively represent a level of compatibility and resonance with the context of insertion, without renouncing the natural and necessary urge to modify the form of the city, and it is therefore suggested to use the categories of permanence and invariance. In this regard, we intend to provide a brief genealogy of these terms, so that we can then proceed with their formulation on the specific case of the city of Mosul.

For Rossi [

16], permanence is represented by certain configurations—whether monuments or road layouts—that, resisting the historical changes of the city, maintain their formal and symbolic character (excluding a possible functional change). The same word “permanence” also brings the connotation of “resistance to change”: it could be defined as what remains durably in a certain condition without any particular change or alteration, or even, as opposed to the concept of evolution, the stabilization and settling of a particular condition. In general, what seems to profoundly characterize permanence is the ability of a formal device to maintain and convey meanings that penetrate the collective consciousness, therefore transcending the simple correspondence between permanence and monuments. Permanencies are formal devices, and they have a connotation of

objectuality that defines them as devices that are recognizable and measurable in their physical substance, that can be precisely located geographically, and that maintain their symbolic and imaginative role for the humanity that benefits from them.

Just as it has been mentioned that permanencies—and indirectly absences that can be considered as

absent permanencies—have a precise physical and formal configuration, there are data—especially pertaining to typological, settlement and figurative features—that have neither specific singularity, nor location, nor recognizability as such; they do not have that

objectuality typical of permanencies. These data are relational data and allow us to identify the consistency of certain characters in different configurations, so much so that Canella [

17] defines the invariant as the morphological constant of typology. In linguistics, the invariant is defined as an element that stays constant as opposed to the variants with whom it may present under certain conditions, as a distinct character that does not change despite continuous or discrete modifications. The first datum of dissimilarity and originality is therefore no longer the observation of a single entity (as is the case with permanence or absence), but instead of a transformation: the entities involved are, then, at least two: one preceding and one following. If there is an aspect that is not changed by the transformation, then that aspect will be an invariant and is the constant in the relationship between the two entities. The invariant is thus a relational datum closely related to the typological perspective of architecture and its ensemble possibilities. In an expanded way, the invariant datum of an urban structure responds to the iconological investigation of what could be defined as the settlement paradigm of a place, permeating the settlement attitudes and building traditions of a built environment.

1 2. Materials and Methods

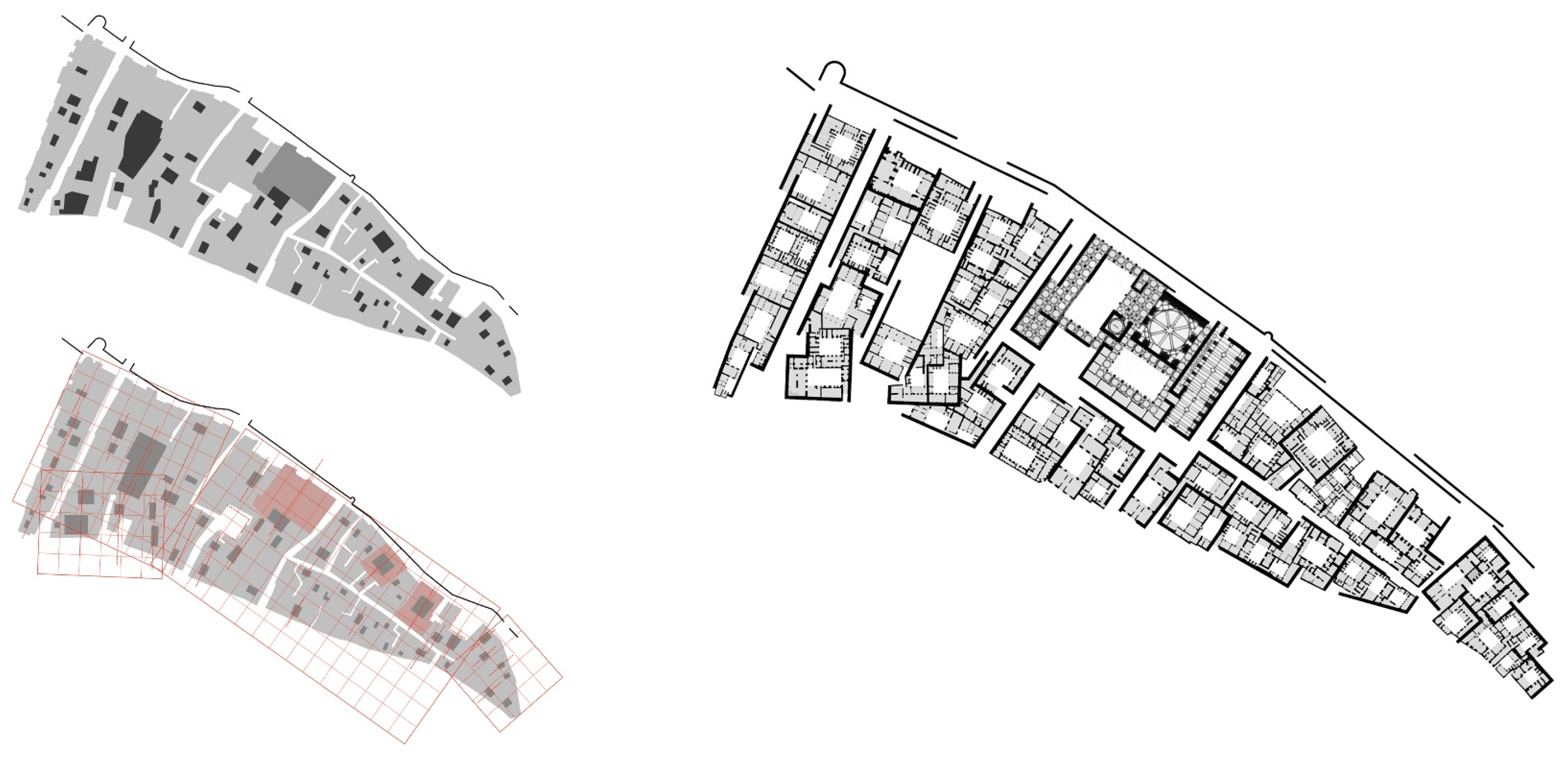

The attempt that we are reporting here for the sake of comparison was to create a graphic and cartographic hypothesis of Mosul, which, starting from some invented data, would however offer some precise aspects of logical and typological representation of the city, in order to have a conceptual map useful for subsequent design reworking. The attempt, which thus aspires to a sort of “conceptual reconstruction” of certain parts of the city, required the selection of certain parameters: certain fixed points that would direct this redesigning process.

Some insights of considerable interest in outlining a strategy of operational knowledge come from the introductory notes that Saverio Muratori provides to the volume containing his

operational studies on the city of Venice: if the hypothesis is in fact the study of reality in its

formal aspect, the representation of this knowledge process can only be metabolized through drawing. The process of redesign, however, has dissimilar characteristics to a common

survey, and the distance between these two poles lies in the critical value of the preconditions. If the survey needs to be precise, the

muratorian redesign aims to be

influenced and directed, thus implying a guideline, an aim, of investigation that—coming as close as possible to the modalities of the scientific method—has within it a theory to be verified: “reality would not be identifiable and isolable without the choice of constants, i.e., without an intentional sense of search. This knowledge is thus concrete when it is possible to transform the subjective intentional vision into the positivity of reality. Hence knowledge is a vision-reality relationship, the positivity of which lies in how far a value hypothesis adopted as a constant reference and total vision succeeds in producing, or rather interpreting and containing the reality” [

18] (p. 9).

If the interpretation of reality through the critical lens of certain constant and plausible elements assumes the role of a substantial reconstruction of reality through a conceptual and consequently inductive way, this operativity suggests an extremely significant method of understanding for those study cases, such as the city of Mosul, where the conceptual way cannot be replaced by the observation of reality. In this way, despite the fact that wartime destruction has compromised much of the building and monumental structure, it is possible to discover again and reconstruct inductively that track—Eisenman defines it as a

non-absent absence [

19]—one that profoundly characterizes urban identity and in the urban fabric remains latent. For this reason, knowledge of certain typical characteristics of Islamic architecture and the Islamic city, which can create a scientifically reliable vocabulary for the conceptual reconstruction of the image of the city, is a prerequisite.

Although the issue of the actual existence of a recognizable Islamic

type of city is a debated topic, it is certainly easier to say that there are certain configurations that allow the creation of an ensemble into which most of the urban settlements of the Islamic world belong. The cause of the recurrence of such characters is mainly to be traced back to the customs and ways of life of Islamic peoples, which condition and determine the shape of the city—thus giving it frequent features. “While Islam does not prescribe formal requirements to architecture, it has conformed ways of life through a matrix of behavioral archetypes that, in fact, have generated consequent physical patterns” [

20] (p. 24).

This is also valid according to Ishan Fethi for Iraqi cities, where it is observed that: “The physical form and functional structure of historical medinas in Iraq generally resemble those of other Islamic countries. The evident coherence of their overall character has been achieved and maintained over the centuries mainly due to the existence of a strong sense of religious tradition and social conformity” [

21].

An attempt to condense and represent the commonalities between Islamic cities was made by Eugen Wirth with the drawing up of an urban diagram that should be suitable for the analysis of different cities (as reported in UN-Habitat and UNESCO reports on Mosul reconstruction [

8]). In this diagram there are all the elements that are considered essential: the central mosque; the souq/bazaar around it; the city walls with the gate system—in whose proximity it was common to find other marketplaces; a fortified citadel; an administrative palace; an open space, whether inside or outside the walls, to be set up for occasional markets, festivities, events, etc.; and some residential districts with

cul-de-sac distribution. What is more, this pattern, which applies to the city as a whole, is also valid in a hierarchical sense: urban expansion is in fact usually regulated by the addition of monumental nuclei around which mosques, local markets and residences grow, creating a

matryoshka system hierarchically organized from the city center to the more external ganglia, starting from the relationship established between the center (in most cases a court) and a perimeter.

In the Islamic world—where form prevails over function and the courtyard building is the main and most common settlement solution for both residential and public building—what changes between buildings with different destinations is essentially the dimensional and proportional datum, while the compositional dialectics that characterize their form are the same. With such a background in mind, an inventory of residential architecture in the Mosul area was carried out, extending the range to Baghdad as a maximum level of tolerance, using archaeological–historical sources from the earliest European reconnaissance trips (such as Reuther [

22] or Herzfeld [

2]) to more contemporary sources such as Warren and Fethi [

23] or Ragette [

24]. The process produced a kind of catalogue of typical houses, thus forming the basis of the studies conducted later (

Figure 2).

Techniques and Processes

The reworking of this cases then led to the identification of some common characteristics, such as: the structuring of residential units and other collective buildings such as mosques and markets around a central courtyard; the presence of Iwans and Talars; and the general introversion of the building structure, to legitimize the chosen ensemble. From the redrawing, as well as from the more general study of the structure of the Islamic city, an attempt was made to abstract some possible type-morphological invariants of the urban structure, including:

The introverted character of the building, both residential and monumental: the settlement attitude of the Islamic world is in fact articulated on the presence of one or more internal courtyards, a source of light and air for all the rooms of the building. This courtyard often assumes definite and precise geometric connotations, compensating instead for a mixtilinear and irregular building perimeter.

These courtyards and/or patios have the function of collective open spaces. They substitute what in western urban culture is represented by squares, public gardens and streets hosting collective life and social relations.

The structure with courtyards and/or patios determines an almost horizontal density of the building structure in the whole city, which is generally no more than three storeys above ground.

The typological scalarity and hierarchy between residential tissue and primary elements: the structure of the Islamic city is well suited to a matryoshka representation. If the entire city, often walled—at least originally—can be recognized as an enclosure with the mosque–souq system at its center, then the internal cul-de-sac ramifications also lead to agglomerations with the mosque and the neighborhood souq as their centrality. This situation imposes a hierarchy of courts: from the largest city mosque in relation to the city, to the local mosque in relation to the neighborhood, to the residential court in terms of residential units.

The Mosul area—but extendable up to Baghdad—is influenced by certain Iranian architectural elements, such as the Iwan, an opening of the inner perimeter wall of the courtyard, which tends to have a pointed or round arch vault. To better understand how the process was performed, we will use as an example a portion of the tissue around the Nabi Djirdjis mosque (

Figure 3), one of the oldest primary elements of Mosul’s historical core. From an aerial photograph—a 2012 photograph was chosen, so as to take into consideration an urban fabric that was not compromised by war destruction and in its

vital state—a redrawing of the area was carried out, highlighting some elements considered particularly relevant: the perimeter of the streets that outline the blocks and the limits of the gaps produced by the internal courtyards and the subdivision, however rough, of the housing units that form the block.

The result is a map of solids and voids, a sort of rooftop plan from which it clearly emerges that the urban structure is characterized by the punctual presence of monumental primary elements, around which spontaneous residential tissues have developed, almost chaotic as a full mass sculpted only by open spaces, represented mainly by tortuous streets and interior courtyards.

The experiment then led to the necessity of determining two parameters: two constants, from which to then proceed to the next stage of assembly. Firstly, these were identified in the perimeters and long-line voids that can be attributed to the street fabric, both in its aspect of defining the blocks and as the distributive character of the cul-de-sac, and consequently selected according to their character of

permanence; secondly, the structuring of most building typologies (whether public, religious, residential, etc.) around a central void allowed the presence of courtyards to be identified as

invariant (the importance of courtyard system is legitimized also by more recent studies [

25,

26]). Starting from these two geometric data, we then proceeded with the progressive selection of the most suitable residential case studies from those previously redrawn, and their assembly within the perimeter of the residential unit previously obtained from the aerial photo, giving priority to the proportional and dimensional relationship of the courtyard (the invariant), and subsequently linking any incongruity with the determined street profile (the permanence). For timing reasons, and not considering this bias detrimental to the demonstrativeness of the operation, priority was given to the typological assembly on the street fronts, leaving the center of some blocks undefined instead.

By combining the assemblages of various areas, the result is a typological map (nominally 1:1000) of the innermost part of Mosul’s historic center: an extremely important area from the Al Nouri Mosque to the citadel area on the Tigris River and the bridge connecting with the east bank of the river and the archaeological site of the city of Nineveh. The map combines arbitrarily elements that are still present (the Dominican complex of Al Saa’a, the upper part of the Souq) and elements that were destroyed due to ISIS or war developments (the Al Nouri Mosque, the Nabi Djirdjis Mosque, the lower part of the Souq) with those imaginary—although fundamentally plausible—elements, such as those introduced through assembly. This map therefore represents a typological combination that is essentially of an invention, apart from a few tangible elements; it is definitely an arbitrary representation, whose aim is to capture an abstract image of the city beyond the reality of the urban corpus, through which we can represent some specific aspects of it. Indeed, by stressing some elements (such as the invariant of the courtyard for residential units) certain type-morphological features are enhanced that reveal in a synoptic representation a possible sense of interpretation of the city’s form, condensing into a drawing not subject to the chronology of time and historical limits; an interpretation of the structuring characteristics of Mosul.

3. Results

Having reached the point where it would be appropriate to comment on the result obtained, however, it seems necessary to introduce a few boundary conditions to describe the level of reality, or labile unrealism, of the map just presented. As Aldo Rossi writes about his Analogous City, the theme of the design-interpretative work is to explore what takes place in the space between reality and imagination, when these two extremes mutually diverge and create a hybrid space between knowledge and operation. The investigation of this theoretical

in-between is also explored by Peter Eisenman in his

Palladio Virtuel [

27] (instead of the analog term, Eisenman evidently uses the term

virtual) where the virtuality of representation relates to the conceptual space between Palladio’s actual realizations and, on the other hand, the drawings he prints: free from inaccuracy, construction site adaptations and solutions that are not harmonious with the original idea. In this context, some terminological definitions need to be provided: ideal, as the final aspiration towards perfection and/or the single image of the Platonic goal to be pursued; real, as the unique representation in its materiality of the body in which the idea is reincarnated; virtual, as the multiple possibilities of readings, re-compositions, and spatial analyses that are inserted in the space between ideal and real. Eisenman’s question, essentially about who the real Palladio is, is therefore only to be found in the multiplicity of combinations and virtual readings that can be applied to the space between real and virtual, namely that of conceptual representation, derived mostly from a

Rogerian model [

28] that assumes the presence of certain logical structures in the city that can be caught, emphasized or overcome. However, we wish to emphasize the substantial equivalence of these terms—at least in relation to the operation proposed here—in the way they are applied; after all, the conceptual approach is nothing more than the hypothesis of a method that interposes between knowledge and operation the common space of imagination. Having said this, it is easier to shift the focus on the role that editing plays in this context as an inventive and imaginative component in actually shaping an elaborate which is as much a conceptual representation of reality as it is the first acknowledgement of its instrumental use as an operational conformation. The process can be summarized as follows:

Identification of certain formal and constant factors that allow the classification of perceptive and analytical inputs from non-metric materials such as photographs, whether aerial or historical. In this case, the presence of permanence and invariants recurs;

The existence and verification of these formal elements (to the point of being non-dimensional components such as invariants, therefore deriving from the abstractness of form in the peripatetic sense as “that what can be separated with thought”) on a variety of typological case and already-studied examples from similar contexts;

The validity of a dual and analogical relationship that allows the transposition and transformation of similar cases into tools that can be applied to the specific case in order to highlight specific features: in other words, using the analogical relationship as an appropriation of the reality rules;

The interruption of the deductive principle of determinacy of shape and the appropriation of a game mechanism that, through similarity and divergence, can provide a reliable tool.

The moment when the interpretative effort is expressed through a creative input represents that space between knowledge and operation that has already been mentioned, and therefore in that space lie the rewriting possibilities of an anthropic environment. The acceptance of a re-compositional impulse that is not strictly logical, if based on stable elements, creates a grey fertile zone from which it is not possible to clearly distinguish what is reconstruction from what can become a project. An example of this hybrid is the Plan Game, an architectural game informally executed by Colin Rowe together with the group of professors at Texas University in Austin known as the Texas Rangers.

2 John Hejduk describes it as follows: “We would take a large white sheet of drawing paper and take turns drawing plans of real or imaginary buildings. For example, Colin would start with the plan of Villa Madama and then Bernhard would connect it with Wright’s Villa Cage, etc. This went on for the whole night and at first light the sheet was full of plans of buildings from different eras to which many hybrids were mixed. At the end, Colin studied the result with devilish excitement” [

29]. What appears is a random collage technique, the meaning of which lies in the selection of fragments and the essential solidity of the memory on which they can be based and from which they can derive. The boundary between knowledge (the memory of past architecture) and invention (understood as the random and changing combination of memory) produces through play a composition of pieces that can prefigure both an element of innovation and an element of control, to the point that it can be defined as a process that involves “the unexpected combination of ideas, the discovery of some hidden relationship between apparently distant images; an intelligent expression presupposes great knowledge; a memory full of notions that the imagination can recall to compose new combinations” [

30] (p. 230). What we want to conclude is how both knowledge and operativity are nourished by a creative process, by invention and imagination. And just as the previous montage served to reconstruct a typological idea of the city of Mosul, so the same procedure, in a different way, can be the substance of an explicitly operational purpose for the architectural rewriting of certain parts of the city.

3.1. Reconstruction through Assemblage

Just as the use of montage for reconnaissance purposes has so far been effectively limited, it is right to also prelude its configurative, inventive and, without terminological fears, rewriting possibilities: all of this by relying precisely on that transformation which allows the preservation of certain forms while changing their meaning. In fact, all typological combinations also have the possibility to be further developed into conformational prototypes, into graphic guidelines that in their arrangement have already selected certain characters considered as essential, and getting rid of those considered unnecessary. The sense of using assemblage is the possibility to establish a relationship with the context of insertion, especially for such historical contests rich in traces and monumental remains. Not, though, a mimesis, nor even a shy condescension—but the study of relationships and the ability to reinvent new ways of context. In this regard, a number of didactic projects will be presented that investigate the relationship, both from a strictly morphological point of view as well as in terms of primary elements, so that while the methods will necessarily be different and, anyway, incomplete in their experimentation, a series of methodological concerns for the context can be established in the typological and formal re-formulation of the elements. For reasons of space and topic, the descriptions given will contain a minimum amount of information and descriptions, without any claim to completeness or demonstrativeness; the focus will mostly stay on the iconographic apparatus, less prosaic and, hopefully, explicatory enough.

3.1.1. Al-Maydan District

Particular attention was paid to the al-Maydan district (

Figure 4), a portion of the historic city facing the Tigris River and completely destroyed due to the bombing it was subjected to by the regular armies stationed on the river’s eastern front. The area historically belongs to the oldest portion of the historic center of Mosul, the first part of the city that originally developed as a defensive district to protect the city of Nineveh. The state of the area after the bombing, once the debris was removed, is that of a huge, shapeless void from which all traces of the previous urban conformation seem to have been removed. Through the use of an aerial photo, an attempt was made as far as possible to track down permanencies and invariants, by similarity and divergence with the knowledge available. The reality of absences and the memory-based imagination then cooperate in tracking down the sense of place and transposing its genetic characteristics towards a possible reconfiguration. The conformation of Islamic cities, in fact, involves the presence of remarkable primary elements surrounded by a very changeable residential texture, and does not seem to require the necessity of any fixed configuration, as long as an accurate snapshot of the hierarchy of solids and voids is taken. The elaborations then outlined some conceptualized representations of the logical structures of places from the dimensional and positional data of the voids, considered in this case to be a more reliable element related to the settlement characteristics of the site. The principles of assembly, however, also included some discontinuous elements in their inventiveness, which would outline certain aspects that would contradict an exclusively reconstructive purpose.

3.1.2. Al Nouri Mosque

The Al Nouri Mosque (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) has always been the monumental cornerstone of the Old City of Mosul, founded by the Atabeg ruler Nur al-Din Mahmud Zengi (the Norandine of the Crusades, known in Europe as the one who took the city of Constantinople from the Christians) during his visit to Mosul in 1170 AD. Located in the north-eastern sector of the Old City of Mosul, the complex is surrounded by a traditional residential area consisting of courtyard buildings. After the destruction in 2017, only the dome structure and part of the walls of the Al Nouri prayer hall remained, while the north, west, and south sides were destroyed. Because of the area’s monumental centrality, UNESCO also announced an international competition in 2020 for the reconstruction of the complex, which was then won, perhaps on compensatory grounds, by a Saudi Arabian firm. The project proposed here, although coming from the world of teaching, follows some common principles to the competition proposals, first of all to start with the image of the emptiness, namely the courtyard of the Mosque, the true representative space: a place of prayer but also, in an analogy with the western town planning closest to us, a true main

square of the city. The boundary walls were made habitable, enriching the possibilities implicit in collective (civil?) architecture of such importance, just as the adjacent block, previously residential, has been transformed into a place to support the collective imprinting of the mosque while preserving a memory of the city’s shape by adapting it to its principal routes.

3.1.3. Nabi Djirdjis Mosque

The Nabi Djirdjis complex (

Figure 7) was, after the Al Nouri Mosque, the largest and most popular Islamic religious site in the old city. It is located in the Nabi Djarjis district, a neighborhood characterized by a dense residential network in a position between the AI Nouri Grand Mosque and the Gate of the Bridge over the Tigris. There is no precise information about this building, which was completely destroyed during the Islamic State’s conquest from 2014 to 2017: neither about the beginning of the building’s construction nor about any historical transformations that may have involved the building. The registered status concerns a religious complex consisting of a main prayer hall in the south—the only building facing the Qibla—and the adjacent (supposed) tomb of St George, on the north side; there was a minaret and a boundary wall to delimit the mosque grounds. These elements, the proportions and the layout gave clues about reconfiguration, without limiting the insertion of leisure and/or collective possibilities such as spaces dedicated to study and prayer, areas for cultural events, and gardens and market activities typically associated with the Islamic religious building type.

3.1.4. Al Saa’a Monastery

The Al Saa’a complex, also known as Saint Mary of the Clock by virtue of its bell tower, although built in the early decades of the 1800s, is of considerable symbolic importance to the city of Mosul. In addition to the clock that has withstood destruction, unlike the complex, it stands as the last representative of a religious syncretism that has always characterized the city. Just as there are Christian origins

3, it is well known that the position on the Silk Road trade communication network led to the coexistence of different religious groups and populations. The church, with its polylobate shape, is reconstructed in its monumental presence, while the monastic structure revisits some of the exasperated linearity found in the original drawings where the entire monastery was based on a cross-shaped layout (

Figure 8), later altered by the overlapping of the two new north-south and east-west axes of the city.

4. Discussion

On the methodological side, the implications of such an approach lead inevitably back to the concept of assemblage and rewriting, which are in their turn strongly connected to that of the urban palimpsest [

31], hinting at a potential analogy where in terms of space design the architecture represents the semantic structure for the city in the same way that the memory could be to the creative process of invention. The multitude of historical events and the layering of urban structures within the city constitute the substantial aspects of transformations. The historical and aesthetic diversity reflected in the city’s palimpsest forms the exemplary facet of urban organization, conceived as a fusion of substance and space. Intertextuality, deconstruction, and reconfiguration are recognized as emblematic elements of what is commonly referred to as “postmodernism”. These features are widely acknowledged in the international critical discourse as “indicative” of the elusive postmodernism, a diverse and all-encompassing framework where these recurring formal elements outline a multifaceted pattern open to a process of investigation. Concerning the architectural aspects, there is a growing need for the specialization of the design activity, particularly in relation to the physical aspects of urban environments. In essence, we can no longer grasp the core of the semantic structure of the city without considering the stratification of urban or architectural interventions. The concepts of permanence and discontinuity are encountered on distinct levels within our artistic and technical work. Consequently, the nature of the city remains an “exiled” element, elevated, and transcended by our work. This aspect also implies that the innate connection to the earth has constantly been experienced within historical times and multiple cultural expressions. Paradoxically, the creative alteration of the city cannot occur unless the natural foundation is first comprehended within a horizon of sense embedded within a historical and cultural context. In terms of architectural culture, is it still suitable to concern the evolutionary process of the city? Above all, what role does architecture play, and what does the contemporary transformation of urban structure entail? It appears that this phenomenon might be ascribed to specific areas of the city, which are susceptible not to deliberate and accepted transformation, but rather to remodeling, change, and conversion from one state to another, regardless of formal, aesthetic, and hence architectural considerations. This phenomenon is prominently outlined in Mike Davis’ work

Ecology of Fear [

32].

Assuming, for example, security-focused enclaves; they represent a logical progression from the accumulations of monads characteristic of contemporary construction. These models challenge the identity of cities, and not only the tradition of the European city-structure and Mediterranean ones. The homogenous fabric produced through the summation of basic elementary structures differs significantly from the continuous city, bearing little resemblance to Soria y Mata’s “Madrid-ciudad lineal” or Miljutin’s Sosgorod. This unexplored dimension of urban settlement also appears irrelevant to the fundamental concept of community in cities, as archaeologists have demonstrated that cities began to define themselves when the spaces between buildings acquired value and importance, emphasizing the meaning of relational spaces over individual structures. Similarly, as soon as it is acquired that not only monuments are interconnected but also open, free spaces as well as mobility infrastructure, the historical dimension of the city evolves with the integration of productive structures into the urban landscape. That was a circumstance, as part of the city’s constructive development, that undergoes a transformation process influenced by the succession of additions, differentiations, oppositions, polarities, and architectural integrations. Nevertheless, when considering the “theories of permanence” formulated by Marcel Poète, Pierre Lavedan and later Aldo Rossi, an acquaintance with the city becomes an essential element for comprehending and critically deciphering urban structure, as well as for understanding the coherent integration of its elements. One of the most notable aspects of the urban settlement crisis and its fragmented discontinuity is the loss of its formal structure. Over 40 years ago, Konrad Lorenz [

33] identified the expansion of the built environment over the land as one of the “gravest corruptions of our civilization.” Therefore, it is essential to explore the role of persistence in the city’s constituent elements in relation to its inevitable transformation, even in the changing and sometimes conflicting trend towards discontinuous and sketchy alterations. Recognizing the texture and reconstituting the parts involves more than merely adapting the appearance of the new. About the complexities of reality, it is necessary to discern the substantial texture and the conceptual and operational elaboration through a critical acknowledgement that aims to select the exemplary elements while rejecting the insignificant, mediating between them.

Above all, the key to understanding the city’s constituent elements lies in cultivating an acquaintance with them: designers must operate directly within the city’s physical structure, composing their own poetic world, makes architectural practice responsible for better decoding this contemporary condition.

5. Conclusions

To recap, within this intricate tapestry of form, identity, memory, and reconstruction, the perspective articulated here aligns with a tradition deeply rooted in the classical concept of the holiness of locations, referring to a dual perspective: the Latin culture, grounded in the transcendental facet of genius, and Greek culture, which finds itself in the mystical entity known as the daimon, or demon, albeit with a wholly distinct interpretation from the conventional one. In this context, the daimon embodies a positive spirit that dwells within each individual, tasked with guiding them towards fulfilling their destiny. Platonic philosophy extends the concept of the daimon not solely to individuals but also to places and objects—be it a residence, a city, a mountain, a forest, a clearing, or a river.

A pertinent question then arises regarding the precise role of the rewriting process within the urban palimpsest. Or, at the very least, whether the transformation of the city lends itself to a critical approach able to re-value its physical essence. Consequently, rewriting implies harmonizing with the daimon, or genius if you prefer, as long as each location can be subjected to an unconventional examination, encompassing the physical and material aspects. This goes beyond mere consideration of its “logical” attributes, emphasizing an inseparable amalgamation of diverse elements, referred to as the physical, geographical, historical, economic, social, cultural, and artistic spheres.

It is worth noting that rewriting in this context also encompasses the act of design, serving as an embodiment of the broader spectrum of change—imitation, representation, and the like. It represents a concrete, critical, and hermeneutic challenge aimed at identifying the specific elements, particularly those that are obscured. These elements, set against the backdrop of a mimetic (repetitive, indifferent) landscape, establish the aesthetic and theoretical significance of the various undertakings involved in transforming the environment.

Thus, a plausible novelty of this approach would be the one to identify some elements to start the reconstruction processes from. Not generic elements specific to the Mosul case, of course, but those eligible to be generalized to other case studies. Where to start in a context of loss of both tangible and intangible memories? The procedures listed above aim to find a compromise strategy working between physical evidence and conceptual reshaping of memories. All of these, assuming some theoretical premises, are here schematically listed:

To specify boundaries and prerogatives of architectural assignments in the transformation process of the urban settlement while distinguishing it from the broad field of sociology, which often becomes a widespread aspect of human experience. The city has now assumed various specific orientations, including functionalist, utopian, materialistic, sacred, unholy, ecological, and even smart in contemporary times. In this endeavor to reimagine portions of the city, its form, as conceived in the Pasolinian sense, is regarded as an indispensable reality. Thus, the form also becomes a perceptual condition. In this context, the city, often described as a “fossilized text,” retains its unique texture, along with the invention of its symbols and meanings, residing within a rhetorical dimension, intricately interwoven with the recurring themes of its history. The act of transformation also represents a process of migration, an overlapping and intertwining of forms and figures extracted through textual and critical analyses of urban structure. Consequently, the transformation of architectural forms gives rise to an idealized space, an architecture that evokes the unraveling of events that have shaped the city’s evolution, recalling its narrative structure through the transmutation of elements rooted in urban memory. It becomes essential to transcend simplistic progressions that confine the city to an abstractly evolutionary dimension, akin to a struggle for survival among species, often emphasizing the supposed dominance of one over another.

The importance of knowledge as a fundamental element in transformation processes is paramount. Assuming the city as our backdrop, with its physical shape and its distinction as a collective entity, the relationship between architectural design and the interpretation of transformations in the physical environment becomes vital. Therefore, in our quest to unearth explanations within the city’s various locales and to effect physical changes, it becomes imperative to admit the existence of certain enduring principles within the history of urban settlement. Within the complex realm of architecture, these enduring principles encompass not only strictly architectural aspects but also cognitive domains that contribute cohesively to understanding the significant milestones in urban development. It is important to note that our observation extends beyond a narrow, disciplinary view of urban history, encompassing the diverse areas of knowledge that have influenced the physical layout of the city. Thus, the role of history in this context is not limited to mere allusion. It serves as a structural driving force in urban design. In this light, it is essential to meticulously and selectively assess all the resources that the city’s narrative provides to the field of architectural design. Above all, it is crucial to identify within the historical narrative a tradition of work characterized by a conscious focus on historicizing architectural design.

Embracing a historical dimension entails a profound commitment to both the past and tradition, as well as to the present and future. Therefore, it becomes essential to deconstruct the inquiry into the relationship between memory, which serves as the focal point of design endeavors, and narrativity, which represents the creative process involved in conceiving, representing, executing, and ultimately designing the space that pays homage to memory. In this context, particularly within the realm of architecture, each project takes on the role of a narrative. It is challenging to revert to a generalized taxonomy as a definitive guideline capable of resolving the inherent uncertainties in the design process. Additionally, an important aspect to address is transcending the process of rewriting and recognizing the iconic nature of artistic works, ranging from individual architectural pieces to the most fundamental creations in the realm of visual language.

The essence of iconological value is merged with the memory of the sources that inspired both its substance and formal attributes. While contemporary aesthetics tend to confine icons within a sterile realm of perfection, detached from their environmental context, the objective should be to restore to figuration its inherent vitality and traditional impact, reminiscent of its original role within the realm of art and myth, which reason’s imperative has somewhat restrained.

Hence, here a need arises to liberate the icon from this paradoxical destiny of pure aestheticization and revive its original prerogatives, thereby expanding the horizons of experimentation within the realm of design.

Throughout historical progressions, the enduring presence of symbolic elements has interacted harmoniously with artistic and architectural achievements. In the lack of explicit and direct references, the field of architectural design has consistently demonstrated its critical worth, extending beyond direct influences, thereby advancing through experimental approaches.

These approaches elevate the question of transformation beyond empirical limitations to a more inductive level, aiming to offer an interpretation of presence as an artefact and its idealization as an absence. This transcendence does not solely concern physical and material absence but primarily revolves around apparent presence, where physical absence represents a void that extends to aspects of culture, identity, tradition, and society. In this particular context, design plays a pivotal role in making these absences not only apparent but also tangible, elevating projects to a conceptual sphere. This restoration of critical awareness within the interplay between artefact and novel construction is essential. The significance of this endeavor lies in the revival of the concept of absence.

It is a hypothesis grounded in metaphorical reconstruction, not as an attempt to replicate verified philological facts, but as a means to authentically interpret the sense of transformation, revitalized in a conceptual framework. This process endows architectural design with a central role, shifting from a claim of objectivity to engaging in interpretive actions tailored to specific contexts. Consequently, the value of any project lies in its ability to recognize deeper meanings within a place, context, and city, achieved through the genuine appreciation of all components within the architectural space, thus bestowing tangible significance upon figuration, both as an iconographic substance and as an iconological value.