‘Thousand Years of Charm’: Exploring the Aesthetic Characteristics of the Mount Tai Landscape from the Cross-Textual Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

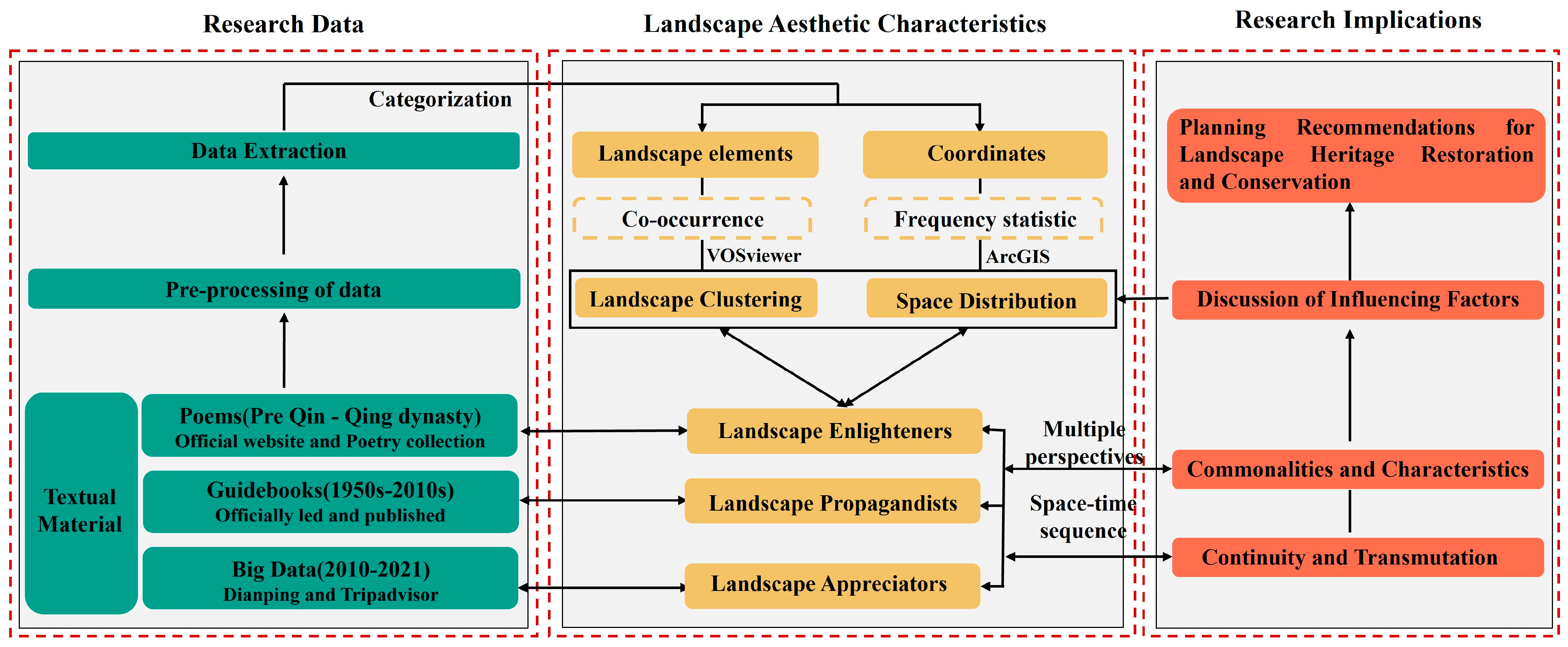

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Setting Up and Acquisition of Research Materials

2.2.1. Setting of Research Materials

2.2.2. Acquisition of Research Materials

2.3. Pre-Processing of Data

2.4. Cluster Analysis

2.5. Spatial Distribution Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Landscape Clustering Characteristics from the Cross-Textual Perspective

3.1.1. Landscape Clustering Characteristics in Poems (Landscape Enlighteners)

3.1.2. Landscape Clustering Characteristics in Guidebooks (Landscape Propagandists)

3.1.3. Landscape Clustering Characteristics in Big Data (Landscape Appreciators)

3.2. Spatial Distribution of Landscape Elements from the Cross-Textual Perspective

3.2.1. Spatial Distribution of Landscape Elements in Poems (Landscape Enlighteners)

3.2.2. Spatial Distribution of Landscape Elements in Guidebooks (Landscape Propagandists)

3.2.3. Spatial Distribution of Landscape Elements in Big Data (Landscape Appreciators)

4. Discussion

4.1. Landscape Clustering Characteristics of Mount Tai

4.2. Characterization of the Spatial Distribution of Landscape Elements

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Text Types | Original Text | Translations | Pre-Processing | Data Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | Removed Data | P | ||||||

| a | b | c | ||||||

| Poems | 五大夫松下看流泉 我寻古松树, 爱此岩下泉. 横泻珠帘静, 斜飞瀑布悬. 积寒生石发, 落日动山烟. 辇道除荒草, 长悲封禅年. | Beneath the Five Dafu Pine, I gaze upon the flowing spring In search of ancient pine trees (Five Dafu Pine), Fond of the spring beneath the rock. The water spills silently like a beaded curtain, And the waterfall cascades obliquely, suspended. The accumulated cold generates moss on the stones, The setting sun animates the mountain’s smoke. Clearing wild grass from the imperial road, Long lamenting the years of Fengshan rituals. | 32 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 16 | |

| Guidebooks | 顺着仙鹤湾的足迹,听着溪里峪的泉水奏鸣,大家前面看到的就是长寿桥景点了。长寿泉座落在后石峪景区东入口的石牌坊旁,附近有一个扫帚峪村,扫帚峪村中百岁以上的长寿老人很多,据说是他们常年引用长寿泉所致。 | Following the footprints along Xianhe Bay, and listening to the symphony of springs in Xi Li Yu, what you see ahead is the Changshou Bridge attraction. Changshou Spring is located next to the stone archway at the eastern entrance of the Houshiyu scenic area, near Saobuyu village. In Saobuyu village, there are many centenarians, and it is said that their longevity is attributed to the regular consumption of water from Changshou Spring. | 45 | 22 | 5 | 7 | 11 | |

| Big data | 来到泰山山顶 ⛰️,古人所言 “一览众山小”, 体验后方知此言 非虚。连峰尽收眼底, 站在泰山顶上这么高的地方, 瞬间心情舒畅, 视野开阔ˏˋ❤ˎˊ。反观最近经历的鸡毛蒜皮的小事和苦闷,简直不值一提。 | Upon reaching the summit of Mount Tai ⛰️, one truly comprehends the ancient saying, “I must ascend the mountain’s crest, it dwarfs all other hills”. Only through experience can one realize the truth of these words. With a panorama of peaks beneath, standing atop Mount Tai (the summit of Mount Tai) offers an uplifting sensation, a broadening of one’s horizons, filling the heart with joyˏˋ❤ˎˊ. In contrast, the trivial troubles and grievances recently experienced seem utterly insignificant. | 34 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |

References

- Turner, B.L. Inka Human Sacrifice and Mountain Worship: Strategies for Empire Unification: Book Reviews. Am. Anthropol. 2014, 116, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, J.B. Mountain Worship in the Pre-Inca Andes: The Case of Nyanpuquio (Ayacucho, Peru) in the Early intermediate Period. Chungará 2005, 37, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Uda, T. Tourism and Religion in the Mount Fuji Area in the Pre-modern Era. J. Geogr. (Chigaku Zasshi) 2015, 124, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, P.; Sadhukhan, S.K. Destination image for pilgrimage and tourism: A study in Mount Kailash region of Tibet. Folia Geogr. 2020, 62, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Yano, K. Sacred mountains where being of “kami” is found. In Proceedings of the 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the Spirit of Place—Between the Tangible and the Intangible’, Quebec, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maříková-Kubková, J.; Frolík, J.; Schlanger, N.; Sklenář, K.; Abadia, O.M.; Kaeser, M.-A.; Lévin, S. (Eds.) Sites of Memory between Scientific Research and Collective Representations: Proceedings of the AREA Seminar at Prague Castle, February 2006; Castrum Pragense; Archeologický ústav AV ČR: Praha, Czech Republic, 2008; ISBN 978-80-86124-86-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. The evolution and identification of cultural landscape value in protected areas: A case of Mount Tai. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jung, T. A Study on the Landscape Elements and Distribution Characteristics of Mount Tai Appearing in Poems. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Arch. 2021, 49, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Ming, Q.; Shi, P. Model and Comparison of Transformation and Development of Mountain Tourist Destinations: A Survey from Changbai Mountain, Taishan Mountain and Huangshan Mountain. J. Guilin Univ. Technol. 2021, 41, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J. The Transitional Characteristics of Landscape & Attractionsin Seoul, through Analysis of the Landscape Associated Texts; University of Seoul: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eric, P. A Charm of Words: Essays and Papers on Language; Hamish Hamilton: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X.; Wang, C.; Qin, R. The Transition of Landscape Aesthetics Based on the Analysis of Landscape Prose about the Western Suburb of Suzhou. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 29, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.R. Yuezhong Yuan Ting Ji (Kecord of the Gardens and Pavilions of Yuezhong [Shaoxing/) and the Chinese Gardens in Shaoxing of the Late Ming Dynasty; Department of Landscape Architecture, Beijing Forestry University: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Q. Research on the Private Garden Style of the Song Dynasty and Its Evolution Based on Garden Literature; Department of Landscape Architecture, Beijing Forestry University: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Shao, M.; Ma, Y. Research on Recreational Activities and Space of Human Settlements of Beijing in Qing Dynasty Based on Semantic Analysis of Ancient Literature. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 29, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Brown, S. ‘The Charm of a Thousand Years’: Exploring Tourists’ Perspectives of the ‘Culture-Nature Value’ of the Humble Administrator’s Garden, Suzhou, China. Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 1071–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H. (Text) Mining the LANDscape: Themes and trends over 40 years of Landscape and Urban Planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 126, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, R.; Fernandez, J.; Li, D. Investigating Sense of Place of the Las Vegas Strip Using Online Reviews and Machine Learning Approaches. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Meng, Y.; Yin, Y. Achievements and Implications of the Research on Landscape in Coastal Zone from 1982 to 2022. Landsc Archit. 2023, 30, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X. Poetic Representation of Landscape Images: Landscape Cognition of Buddhist Temple Gardens of the Ming Dynasty in Beijing. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 29, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koblet, O.; Purves, R.S. From Online Texts to Landscape Character Assessment: Collecting and Analysing First-Person Landscape Perception Computationally. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 197, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiu, J. Analysis of Moon Lightscape Configuration in Traditional Chinese Gardens. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 30, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Rho, J.H.; Son, H.K.; Kim, H.K. A Study on the Landscape Structure and Meaning of Eight Scenic Views of Yeongsa-jeong Pavilion through the Painting and Poem. J. Korean Inst. Tradit. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 35, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Woudstra, J.; Feng, W. ‘Eight Views’ versus ‘Eight Scenes’: The History of the Bajing Tradition in China. Landsc. Res. 2010, 35, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, K.; Jia, M.; Kong, M.; Suzuki, H.; Zhang, J. Study on the Characteristics of Landscape Images of Changdeok Palace Rear Garden Described in the Poem “Sangrimshipkyeong”. Proc. Environ. Inf. Sci. 2014, 28, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Fung, S. Rethinking Landscape Experience: Preliminary Reading of a Painted Album of the Garden of Artless Administration by Wen Zhengming. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Comparative Research on Tendency and Characteristics on Natural Landscape Appreciation Culture in China and Japan Focus on Combination Modes of Landscape Description Elements in Hakkei View Names; Department of Civil Engineering School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Tao, Z.; Rong, H. A Study on the Space-time Characteristics of Typical Landscapes and Tourism Aesthetics in Poetry about the Lushan Mountain. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Lu, L.N.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Landscape Character Identification in Large-Scale Linear Heritage Areas: A Case Study of Beijing Great Wall Cultural Belt. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 29, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, F.; Jim, C.Y.; Bahtebay, J. Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Landscape Patterns in an Oasis City. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 3872–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Sánchez, M.; Linares Gómez Del Pulgar, M.; Tejedor Cabrera, A. Historic Construction of Diffuse Cultural Landscapes: Towards a GIS-Based Method for Mapping the Interlinkages of Heritage. Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; He, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, S.P.Y.; Lin, H.; Leung, Y.S. Mapping the Most Influential Art Districts in Shanghai (1912–1948) through Clustering Analysis. J. Arts Manag. Law. Soc. 2022, 52, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; He, J.; Liu, S. Representation of the Spatio-Temporal Narrative of The Tale of Li Wa李娃传. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, R.H.; Mark, A.H.; Annalise, L.; Erik Steiner, V. Mapping the Emotions of London in Fiction, 1700–1900: A Crowdsourcing Experiment. In Literary Mapping in the Digital Age; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-59259-6. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, C.; Gregory, I.N.; Taylor, J.E. Locating the Beautiful, Picturesque, Sublime and Majestic: Spatially Analysing the Application of Aesthetic Terminology in Descriptions of the English Lake District. J. Hist. Geogr. 2017, 56, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.D.; Lee, S.H. The Scenery of Okinawa Depicted in Jeong Sun Chik’s Jungsan Dongwon Palgyeongsi. Jpn. Cult. Stud. 2018, 1, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J. Mount Tai Tong Jian; Qilu Publishing House: Qilu, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Mount Tai Chronicles History; Shandong People’s Publishing House: Jinan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F. Research on Planning Theory and Methods of Landscape Architecture in Mount Tai; Department of Landscape Architecture, Beijing Forestry University: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. The Characteristics of Mount Tai Landscape in the Landscape Associated Texts; Kyungpook National University: Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Jung, T. A Study on Landscape Characteristics of Mount Tai Appearing in Guidebooks. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Arch. 2023, 51, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, T. Changing Image of the Mt. Fuji Region as a Tourism Destination: Content Analysis of the Rurubu Mt. Fuji Guidebook Series. J. Geogr. (Chigaku Zasshi) 2015, 124, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jung, T. A Study on Landscape Characteristics of Mount Tai in Big Data. KLC 2022, 14, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M. Mapping Scientific Frontiers, 3rd ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Ding, J. Comparison of Visualization Principles between Citespace and VOSviewer. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. Agric. 2019, 31, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.H. GIS-Based Quantitative Methods and Applications; The Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 2009; ISBN 978-7-100-06092-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lefever, D.W. Measuring Geographic Concentration by Means of the Standard Deviational Ellipse. Am. J. Sociol. 1926, 32, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, R. Return Period and Pareto Analyses of 45 Years of Tropical Cyclone Data (1970–2014) in the Philippines. Appl. Geogr. 2018, 97, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T. Bixia Yuanjun’s belief and rural society in North China: A study on the incense society of Mount Tai in Ming and Qing Dynasties. J. Lit. Hist. Philos. 2009, 2, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.F. Research on Transformation of Mount Tai Gods and the Geographical Pilgrimage in the Ming and Qing Dynasties; Department of Historical Geography, Jinan University: Jinan, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Research on Governance of Mount Tai in Ming and Qing Dynasties. Ph.D. Dissertation, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.X. Effects and Sociological Features of Organizing Festival Competitions Exampled by the International Mount Tai Climbing Festival. Sport. Sci. 2000, 20, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. A Study on Landscape Characteristics and Experiences of Mt.Samgak(三角山)in Mountain Travel Essay(遊山記). Master’s Dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M.S. Back to Nature: Norwegians Sustain Increased Recreational Use of Urban Green Space Months after the COVID-19 Outbreak. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Shi, J.; Lu, T.; Furuya, K. Sit down and Rest: Use of Virtual Reality to Evaluate Preferences and Mental Restoration in Urban Park Pavilions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 220, 104336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, K.; Barthel, S.; Giusti, M.; Hartig, T. Visiting Nearby Natural Settings Supported Wellbeing during Sweden’s “Soft-Touch” Pandemic Restrictions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Bixia Yuanjun and Mount Tai Culture, 2017th ed.; Shandong People’s Publishing House: Jinan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.; Zhang, S. Mount Tai Hundred Questions; Tai’an City News Press: Hong Kong, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Ancient Mount Tai; New World Press: Beijing, China, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q. Research on Tai’an Urban Space Design Based on the Idea of “Shan-Shui” City; Department of Landscape Architecture, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology: Xi’an, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mount Tai Scenic Area Management Committee. Mount Taishan in the Past Century (1900–2000); Shandong Pictorial Publishing House: Jinan, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Research Materials | Creators of Texts | Standpoint | Characterization | Time | Social Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poems | poets and celebrities | landscape enlightenment | famous or original landscapes | ancient (Pre-Qin~Qing Dynasty) | slave society and feudal society |

| Guidebooks | management directors | landscape promotion | landscape promotion | modern (1949–2010s) | socialist society |

| Big data | modern tourists | landscape appreciation | personal landscape perception | modern (2010~2021) | socialist society |

| Text Type | Collected Data | Words Unrelated to Landscape | Meaningless Grammatical Words | Synonyms | Pre-Processed Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poems | 2962 | 1261 | 699 | 264 | 738 |

| Guidebooks | 32,858 | 19,886 | 2875 | 2528 | 7569 |

| Big data | 11,990 | 3461 | 2721 | 2559 | 3249 |

| Text Type | Time Period | Core Elements (Frequency of Occurrence) | Clustering Themes | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poems (historic material) | Pre-Qin | emperors, Fengshan, summit, immortals, Huang Di | A, B, C, D | ⅰ, ⅱ, ⅳ, ⅴ |

| Sui-Tang | emperors, Fengshan, immortals, clouds, summit | A, B, C, E | ⅰ, ⅱ, ⅳ | |

| Song-Yuan | summit, climbing, monks, temples, seclusion | C, Ba, D, E, A | ⅳ, ⅱ, ⅰ | |

| Ming | summit, climbing, overlooking, majestic, continuous peaks | C, Ba, D, E, Aa, F, G | ⅳ, ⅲ(ⅱ), ⅴ | |

| Qing | summit, climbing, majestic, continuous peaks, overlooking | C, Ba, D, E, Aa, F, G | ⅳ, ⅲ(ⅱ), ⅴ | |

| Total | summit, emperor, Fengshan, immortals, clouds | C, A, B(Ba), D, E, F, G | ⅰ, ⅱ, ⅲ, ⅳ, ⅴ | |

| Guide- books | 1950s | summit, cliffs, Fengshan, stone tablet, emperors | C, H, Aa, I | ⅳ, ⅱ, ⅲ |

| 1980s | cliffs, streams, stone tablet, stone inscription, springs | C, H, Aa, I | ⅳ, ⅱ, ⅲ | |

| 1990s | streams, cliffs, stone inscription, overlooking, climbing | C, H, Aa, I | ⅳ, ⅱ, ⅲ | |

| 2000s | aged-pine, streams, valleys, cliffs, continuous peaks | C, H, Aa, I, J | ⅳ, ⅱ, ⅲ | |

| 2010s | climbing, cliffs, continuous peaks, streams, overlooking | C, H, Aa, I, J | ⅳ, ⅱ, ⅲ | |

| Total | cliffs, streams, valley, stone inscription, summit | C, H, Aa, I, J | ⅳ, ⅱ, ⅲ | |

| Big data (social media) | 2010~2021 | summit, sunrise, climbing, savoring, majestic | C, K, I, H, G | ⅳ, ⅱ, ⅲ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Y.; Liu, B.; Ma, L.; Han, X.; Jung, T. ‘Thousand Years of Charm’: Exploring the Aesthetic Characteristics of the Mount Tai Landscape from the Cross-Textual Perspective. Land 2023, 12, 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122129

Yu Y, Liu B, Ma L, Han X, Jung T. ‘Thousand Years of Charm’: Exploring the Aesthetic Characteristics of the Mount Tai Landscape from the Cross-Textual Perspective. Land. 2023; 12(12):2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122129

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Ying, Bing Liu, Lin Ma, Xin Han, and Taeyeol Jung. 2023. "‘Thousand Years of Charm’: Exploring the Aesthetic Characteristics of the Mount Tai Landscape from the Cross-Textual Perspective" Land 12, no. 12: 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122129

APA StyleYu, Y., Liu, B., Ma, L., Han, X., & Jung, T. (2023). ‘Thousand Years of Charm’: Exploring the Aesthetic Characteristics of the Mount Tai Landscape from the Cross-Textual Perspective. Land, 12(12), 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12122129